Abstract

Background:

Gel-forming mucins (GFMs) play important roles in otitis media (OM) pathogenesis. Increased mucin expression is activated by pathogens and proinflammatory cytokines. Bacterial biofilms influence inflammation and resolution of OM and may contribute to prolonged mucin production. The influence of specific pathogens on mucin expression and development of chronic OM with effusion (OME) remains an area of significant knowledge deficit.

Objectives:

To assess the relationship between GFM expression, specific pathogens, middle ear mucosal (MEM) changes, biofilm formation, and antibiotic utilization.

Methods:

Mixed gender chinchillas were inoculated with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) strain 86028NP or Streptococcus pneumoniae (SP) strain TIGR4 via transbulla injection. Antibiotic was administered on day 3 – 5 post inoculation. GFM expression was measured by quantitative PCR. Biofilm formation was identified and middle ear histologic changes were measured.

Results:

SP infection resulted in higher incidence of biofilm and ME effusion compared with NTHi infection. However, NTHi persisted in the ME longer than SP with no substantive bacterial clearance detected on day 10 compared with complete bacterial clearance on day 10 for 50–60% of the SP-infected chinchillas. Both infections increased MEM inflammatory cell infiltration and thickening. NTHi upregulated the Muc5AC, Muc5B and Muc19 expression on day 10 (p = 0.0004, 0.003, and 0.002 respectively). SP-induced GFM upregulations were trended toward significant. In both NTHi and SP infections, the degree of GFM upregulation had a direct relationship to increased MEM hypertrophy, inflammatory cell infiltration and biofilm formation. Antibiotic treatment reduced the incidence of ME effusion and biofilm, limited the MEM changes and reversed the GFM upregulation. In NTHi infection, the rate of returning to baseline level of GFMs in treated chinchillas was quicker than those without treatment.

Conclusions:

In an animal model of OM, GFM genes are upregulated in conjunction with MEM hypertrophy and biofilm formation. This upregulation is less robust and more quickly ameliorated to a significant degree in the NTHi infection with appropriate antibiotic therapy. These findings contribute to the understanding of pathogen specific influences on mucin expression during OM pathogenesis and provide new data which may have implications in clinical approach for OM treatment.

Keywords: otitis media, gel-forming mucins, antibiotic treatment

1. INTRODUCTION

Otitis media (OM), bacterial and/or viral infection of the middle ear (ME), continues to be the most frequently diagnosed pediatric illness in the US. Although often self-limited, without proper treatment, OM may cause severe complications. Approximately 30–40% of OM children develop recurrent episodes which require multiple physician visits, multiple courses of antibiotics, and the potential need for surgical intervention. In another subset of OM children, otitis media with effusion (OME) develops and can become chronic in nature and impact overall hearing and speech and language development [1–3].

One of the main characteristics of OM is increased mucin production by middle ear mucosal (MEM) epithelium [4–6]. These mucins are secreted at increased quantity compared to steady-state to protect the underlying MEM from pathogen invasion and adherence and to assist in pathogen removal through mucociliary clearance. However, the increased mucin production can persist following the resolution of the acute infection, become detrimental to mucociliary clearance and ultimately lead to persisting and substantive hearing loss [5]. Each mucin has unique characteristics and changes in the production of any mucin can change the composition, function and viscosity of the mucous overlaying the epithelium. The secretory gel forming mucins (GFM) identified in the MEM are MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC5B and MUC19 [5].

Increased mucin expression is activated by bacteria [7] and proinflammatory cytokines which are upregulated during an episode of OM [8–13]. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (SP), the subject of this investigation, are recognized as primary causative OM pathogens. There are differences in the virulence and ME impact between pathogen families such as SP and NTHi and, in addition, each of these pathogens has numerous strains or serotypes which also have been shown to differentially impact any given patient with OM [14,15].

Biofilms have been well-documented as an important component of OM pathogenesis. NTHi and SP coexist within biofilm communities during chronic and recurrent infection [16,17]. The prevalence of biofilms influences inflammation and resolution of OM and may contribute to prolonged mucin production [18–21].

A paucity of data exists in well-controlled scientific experiments to better understand the host molecular and genetic response to specific pathogens, differences between pathogens and the implications of these differences on the concepts related to patient treatment. Specific pathogen influences on mucin production and development of chronic OM remains an area of significant knowledge deficit. This report represents the first in vivo controlled study to explore results related to the two most common bacterial OM pathogens and their influence on mucin gene expression, MEM changes and the impact of antibiotic therapy on these changes.

2. METHODS

2.1. Bacterial culture

NTHi strain 86028NP and SP strain TIGR4 were cultured and inoculum was prepared as previously described [22]. Both were selected for their accessible complete genomic sequences, baseline data for biofilm formation and infection models [23,24].

2.2. Experimental OM

Ninety four mixed gender chinchillas age 6–10 months old, from R&R chinchilla ranch, were acclimatized to the vivarium for 5–7 days. All animals entering the study showed no visible signs of illness or ear disease by otoscopic exam. The animals were inoculated with NTHi (~103 CFU/ear) or SP (50 ~ 90 CFU/ear) via transbullar injection on experimental day 0. On day 3 to day 5, half of the infected chinchillas were given ceftriaxone at 50mg/kg daily via intramuscular injection. At day 3, 6, 10, and 17, the animals (minimum of 3 per time point) were euthanized. All animals were handled according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

2.3. Specimen collection: the middle ear biofilm, effusion, bacterial count and RNA

Biofilm formation in the MEM surface was assessed by macroscopic identification as previously described [25, 26]. The MEE was collected and recorded when present. The middle ear lavage was performed using 1 ml sterile PBS. The effusion and lavage were combined to enumerate total viable bacteria by plating and presented as CFU/ear. Only planktonic bacterial cells were counted in the combined lavage and effusion when applicable. It was not possible to count all bacteria in biofilm without having to homogenize the whole bulla which would eliminate the MEM sample for RNA preparation and host gene assessment. The lavage was conducted to present a consistent methodology in the event that effusion was absent. We used the methodology of CFU/ear rather than CFU/ml since the volumes of samples varied somewhat in the process of lavage and specimen collection. The MEM lysate was harvested for RNA preparation from the right bulla using 3ml of RLT buffer (QIAGEN). The left bulla was excised for histology.

2.4. Histologic assessment of the chinchilla middle ear

Chinchilla bulla was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, decalcified in 10% EDTA pH 7.0 for 14 days, cryo-protected with 20% sucrose in PBS and embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek). The decalcified bulla was serially sectioned to 8 μm and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Slides were scanned using Nanozoomer (Hamamatsu Photonics) at 20x magnification and digital images were analyzed by a board-certified pathologist (ACM). The MEM thickness from up to 13 distinct regions of intact mucosa was determined for each animal by measuring the size of the epithelium from the basement membrane to the apical surface using NDP.view software (Hamamatsu Photonics). Measurements were verified using a micrometer. The mean values were used as a representation of the ME sample. It was a standard protocol for histologic analysis that the measurements were not to be taken from the areas with underlying specialized structure. Detached or disrupted epithelium occurred during tissue processing and cryosectioning and these areas were not used in analysis to avoid inaccurate measurements. There were no differences regarding these excluded areas between animals in the various arms of the investigation. The immune cell infiltrates were assessed and characterized as follows: the immune infiltrate in the mucosal epithelium (in the same regions where mucosal thickness was measured) was determined as the percent of total cellularity, and the severity of the ME exudate was scored: 0 (none), 1 (mild; ≤ 2 foci of inflammatory exudate), 2 (moderate; 3–4 foci of inflammatory exudate), and 3 (significant; >4 foci of inflammatory exudate or large, confluent aggregates of inflammatory cells).

2.5. Gel forming mucin gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from the MEM lysate using RNeasy Kit (QIAGEN). RNA samples were reverse transcribed using the SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (ThermoFisher). GFM expression was determined by quantitative PCR using TaqMan chemistry. Each mucin expression was analyzed individually using the specific chinchilla primer/probe as listed in Table A.1. Each GFM level was normalized to the expression of house-keeping gene Hprt1. The relative fold change of mucin gene was calculated using 2−ΔΔCt methodology [27].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

We used the data from the ear with higher gene expression. There was no statistically significant difference between gene expression data obtained from left and right ears. Log transformations were applied to the relative fold changes and MEM thickness, and then Student’s t-tests were used for comparisons between different group. Impact of antibiotic treatment on incidence of the ME effusion and biofilm was assessed using the Fisher’s exact test. The post hoc analyses results were adjusted by the step-down Bonferroni method. The correlation was determined using the linear fit. The statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Different bacterial pathogens induced differential responses associated with OM

Transbullar inoculation of OM pathogenic bacteria induced acute otitis media (AOM) in chinchillas by 3 days post inoculation. Despite a lower dosage of SP inoculum, a higher OM associated mortality was detected in SP-TIGR4 affected chinchillas (38%) while none occurred in NTHi-86028NP affected chinchillas. A higher incidence of both the ME biofilm and effusion was observed in SP-TIGR4 than NTHi-86028NP group (Table A.2).

3.2. Persistent microbial infection during single-species bacteria induced OM

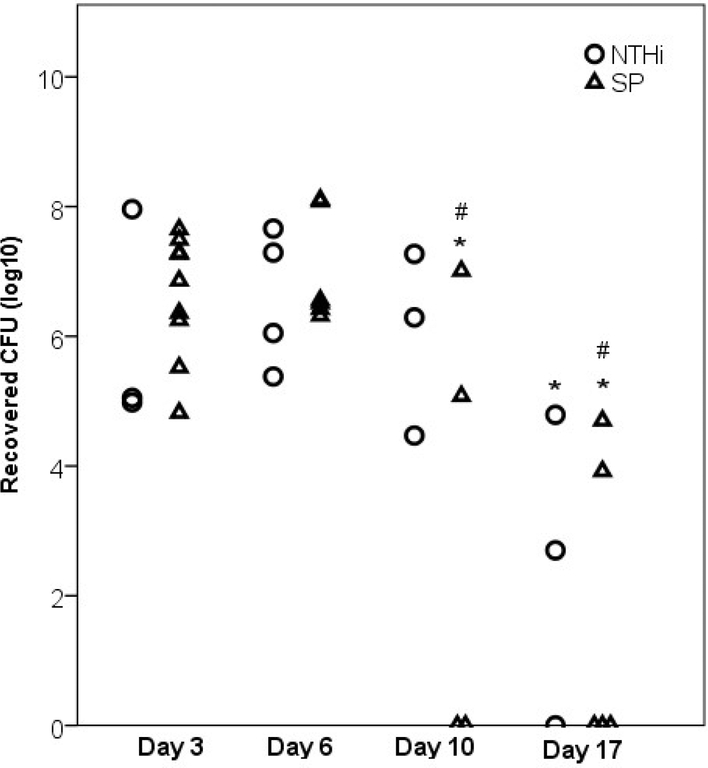

As demonstrated in Fig. 1, the recovered viable NTHi-86028NP bacteria from days 6 and day 10 were not substantively different from viable bacteria measured 3 days following infection (p = 0.96 and >0.99, respectively). Bacterial clearance was identified on day 17 and though the degree of clearance was still not statistically different from day 3 (p = 0.112), it was different from day 6 (p =0.042). Of the surviving SP-TIGR4 infected animals, clearance of all bacteria was observed in 50–60% of the animals on day 10 (2 out of 4) and day 17 (3 out of 5). Recovered viable SP cells were significantly decreased on day 10 and day 17 compared to day 3 (p = 0.024 and <0.001, respectively) and day 6 (p = 0.019 and <0.001, respectively).

Figure 1. Bacterial counts recovered from chinchilla middle ear cavities.

The viable NTHi-86028NP and SP-TIGR4 were detectable in the middle ear of infected chinchillas up to day 17 post inoculation. NTHi-86028NP displayed some clearance from chinchilla ME on day 17. Of the surviving SP-TIGR4 infected animals, however, demonstrated a clearance in 50% of affected chinchillas starting on day 10 with the significant lower average number of viable cells than those of day 3 and day 6. (#) indicated p<0.05 vs day 3, (*) indicated p< 0.05 vs day 6.

3.3. Histologic change in MEM and GFM expression during OM

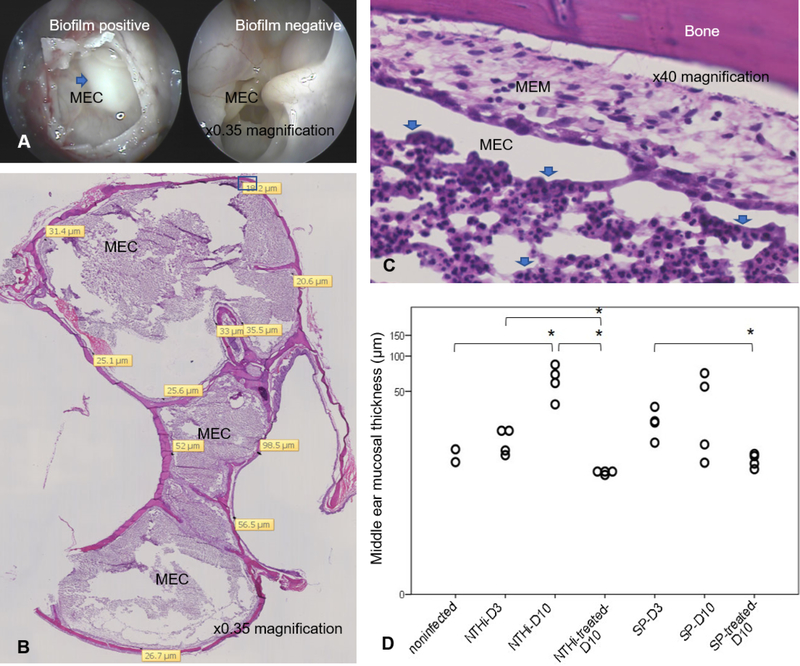

Both NTHi-86028NP and SP-TIGR4 infected chinchillas demonstrated gross biofilm formation in the middle ear (Fig. 2A). Both infections increased the inflammatory cell infiltration and exudate in the ME cavities (Fig. 2B–C). The neutrophils detected in nontreated MEM were ranged from 25% to >50% of total cellularity whereas none to <10% of total cellularity in MEM with antibiotic therapy. The inflammatory exudates in nontreated ME were scored 2–3 whereas those of treated animals were scored 0–1. NTHi-86028NP particularly caused significant change in MEM thickness (Fig. 2D) on day 10 (p = 0.019). There was a similar trend though not significant on day 3 (p = 0.25) and day 10 (p = 0.90) in SP-TIGR4 group. In NTHi group, antibiotic treatment returned the MEM thickness to basal level on day 10 as compared with nontreated day 3 (p = 0.048) and day 10 (p = 0.008). The treatment in SP group significantly reduced MEM thickness on day 10 as compared with nontreated day 3 group (p =0.022). These infections caused MEM changes which were correlated with immune cell infiltration (r = 0.690, p = 0.013), the presence of ME exudate (r = 0.639, p = 0.025), and the upregulation of Muc5AC (r = 0.786, p = 0.004) and Muc5B (r = 0.724, p = 0.008).

Figure 2. Histologic changes in the middle ear of OM induced chinchillas.

(A). The opening access to chinchilla middle ear cavity (MEC) from top of the bulla. Blue arrow indicated gross white biofilm mass, often accompany by effusion, detected in the affected chinchilla as compared to the ME cavity without biofilm. (B). The representation image of NTHi-infected chinchilla bulla, sectioned on sagittal plane, on day 10 post inoculation. The infection caused the inflammatory cell infiltration into the middle ear cavity. MEM lined along the bone structure. Yellow tag indicated area where MEM thickness was measured. High magnification of inset (C) demonstrated MEM and significant aggregate of immune cells in exudate (blue arrow) in the middle ear cavity. (D). The change in chinchilla MEM thickness and impact of antibiotic treatment during OM. Each data point represented an average of repeated measurements. Log Transformation was applied and the Student’s t-test was used to compare the group. D3; day 3 post inoculation, D10; day 10 post inoculation, (*) indicated p<0.05.

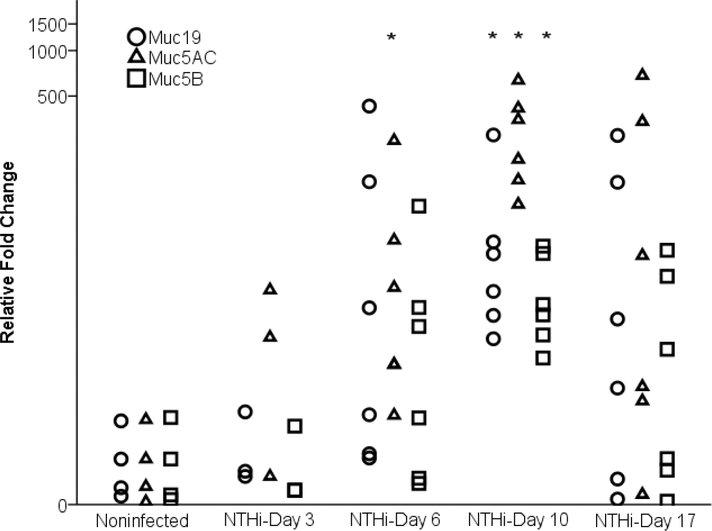

NTHi-86028NP and SP-TIGR4 caused upregulation of Muc5AC, Muc5B and Muc19 from day 6 post infection. In NTHi infected chinchillas (Fig. 3), the level of Muc5AC on day 6 (p =0.024), and the levels of Muc5AC, Muc5B and Muc19 on day 10 were significantly increased compared with noninfected control (p = 0.0004, 0.003, and 0.002 respectively). All GFMs returned to baseline levels in half of the animals on day 17. SP-TIGR4 infected chinchillas demonstrated large variations in mucin expression values resulting in an increasing trend that did not reach significance from day 6 to day 17 (Fig. A.1). Notably on day 10, most (4 of 5) chinchillas in the group demonstrated significantly high GFM but one chinchilla with distinguishing low GFM level substantively decreased the average mucin gene change and impacted the statistical analysis. About half of SP-infected chinchillas have elevated GFM on day 17.

Figure 3. Mucin expression in the middle ear mucosa of NTHi-86028NP infected chinchillas.

NTHi-86028NP caused upregulation of Muc5AC, Muc5B and Muc19 in the ME from day 6 post inoculation. The elevated chinchilla Muc5AC, Muc5B, and Muc19 reached significant level on day 10 (P<0.05). On day 17, all GFM expression were back to baseline level in half of the animals. High variation in GFMs levels were displayed in this outbred animal model. (*) indicated p<0.05.

3.4. Impact of antibiotic treatment on incidence of ME effusion, biofilm formation and GFM

The regimen of daily 50mg/kg ceftriaxone for 3 consecutive days was effective in eliminating planktonic bacteria from the ME. Without treatment, both NTHi and SP formed biofilm with MEE detectable through day 17 (Table 1). When given ceftriaxone, NTHi-infected chinchillas demonstrated clearing of biofilm by day 6 and fewer effusion which cleared by day 17. Similarly, with treatment, effusion was present in fewer SP infected chinchillas on day 6, day 10 and completely cleared on day 17. The presence of biofilm was declined in SP with treatment group on day 6 and none was detected thereafter. The antibiotic treatment reduced biofilm formation in the ME and the presence of effusion in both infections.

Table 1.

Incidence of middle ear effusion and biofilm formation in chinchilla middle ears.

| Group/Time Point | ME effusion (positive/total ears) | Biofilm (positive/total ears) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 | Day 6 | Day 10 | Day 17 | Day 3 | Day 6 | Day 10 | Day 17 | |

| 86028NP | 2/3 | 9/12 | 8/9 | 4/9 | 2/3 | 8/12 | 7/9 | 4/9 |

| 86028NP with antibiotic | nt | 4/12 | 2/9 | 0/9 | nt | 0/12 | 0/9 | 0/9 |

| TIGR4 | 3/3 | 7/8 | 5/6 | 3/5 | 3/3 | 6/8 | 4/6 | 4/5 |

| TIGR4 with antibiotic | nt | 3/6 | 3/7 | 0/7 | nt | 2/6 | 0/7 | 0/7 |

nt: not tested

We further investigated the association between the biofilm and mucin expression (Table 2). Regardless of the time point and treatment when biofilm was present, there was a significant increase of each GFM. In NTHi infection, the MEM with biofilm expressed significantly higher levels of Muc5AC, Muc5B and Muc19 than those without biofilm. Similarly, SP-induced biofilm positive MEM demonstrated significant higher levels of Muc5AC and Muc19. This upregulation of GFMs was significantly associated with the presence of biofilm in both infections.

Table 2.

The presence of biofilms was associated with upregulation of mucins.

| Pathogens | Mucins | Biofilm positive | Biofilm negative | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTHi-86028NP | Muc5AC | 281.5 ± 74.1 | 60.8 ± 40.6 | <0.0001 |

| Muc5B | 24.4 ± 5.8 | 4.6 ± 2.7 | <0.0001 | |

| Muc19 | 71.8 ± 32.1 | 22.8 ± 17.0 | 0.0022 | |

| SP-TIGR4 | Muc5AC | 355.4 ± 139.0 | 95.0 ± 60.0 | 0.013 |

| Muc5B | 27.8 ± 16.5 | 13.9 ± 8.5 | 0.065 | |

| Muc19 | 342.2 ± 223.7 | 168.0 ± 103.6 | 0.025 |

The relative expression of GFM was measured in the affected chinchilla MEM with (biofilm negative) and without antibiotic treatment (biofilm positive). Value = mean ± SEM.

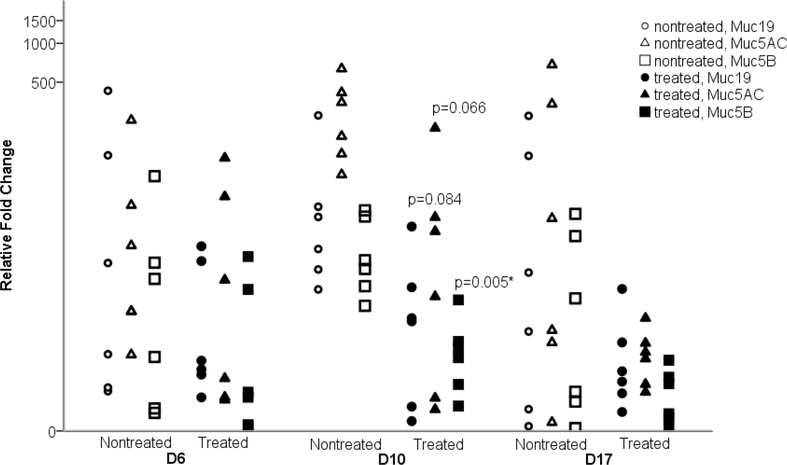

Ceftriaxone modified GFM responses in NTHi-86028NP affected chinchillas resulting in significant reduction of Muc5B (p=0.005) but not Muc5AC (P=0.066) and Muc19 (p=0.084) compared with their cohorts without treatment on day 10 (Fig. 4). In SP-TIGR4 infected chinchillas, there was a substantive reduction of Muc5AC, Muc5B and Muc19 in animals that received antibiotics (Fig. A.2). However, given that this SP strain more readily cleared in half of the animals, and generated larger variation of mucin levels this also resulted in less-impactful results from antibiotic treatment. Given GFM upregulation was associated with the presence of ME biofilm, additional analysis was performed to compare the relative GFM expression between the nontreated MEM with positive biofilm and treated MEM from SP affected chinchillas (Table 3). The antibiotic treated animals demonstrated reduced expression of Muc5AC, Muc5B and Muc19 on day 10 and day 17. Although not statistically significant; this likely related to overall small sample numbers in each group. The rates of returning to baseline level of GFMs in treated chinchillas was quicker than those without antibiotic treatment.

Figure 4. Impact of antibiotic treatment on mucin expression in the NTHi-86028NP infected chinchilla MEMs.

When treated with ceftriaxone, NTHi-86028NP infected chinchillas MEM demonstrated significant decrease in Muc5B on day 10 compared to animals without treatment. The reduction of Muc5AC and Muc19 levels were toward significance. The rates of returning to baseline level of all GFMs were quicker in animals given antibiotic treatment. D6, D10, D17 indicated day 6, day 10, day 17 post inoculation, respectively. (*) indicated p<0.05.

Table 3.

Impact of antibiotic treatment on GFM expression in the biofilm positive MEM of SP-infected chinchillas.

| Experimental group | Muc5AC | Muc5B | Muc19 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | p-value | Median | IQR | p-value | Median | IQR | p-value | ||

| day10 | nontreated (N=3) | 548.9 | 858.8 | 0.18 | 5.7 | 117.9 | 103.6 | 1596.2 | 0.31 | |

| treated (N=5) | 1.2 | 364.1 | 1.4 | 49.7 | 0.52 | 1.9 | 816.8 | |||

| day17 | nontreated (N=4) | 102.6 | 346.7 | 0.18 | 12.2 | 20.8 | 118.5 | 236.2 | 0.11 | |

| treated (N=5) | 6.8 | 19.7 | 1.4 | 4.8 | 0.34 | 0.6 | 7.2 | |||

IQR: Interquartile ranges of the GFM relative expression.

4. DISCUSSION:

While SP and NTHi are recognized as primary OM pathogens, this study is the first to provide data demonstrating a differential response to these pathogens on GFMs, middle ear mucosal changes, time to infection, and antibiotic utilization in this animal OM model. The chosen outbred chinchilla model importantly represents a model with potentially more individualized responses to biologic processes such as infection compared to an inbred animal model. Although these differential responses in an outbred model have the potential for greater data heterogeneity, this model is more analogous to the human response in which patients, even exposed to the same bacterial infection, demonstrate differences in severity and response [28–30]. Although the heterogeneous responses at times impacted the statistical significance of the results, as occurred in the SP GFM responses, they provided a “real-world” presentation of data in exploring clinical treatment questions.

This study demonstrates differential GFM upregulation and biofilm formation between NTHi and SP in the chinchilla ME. The results demonstrate that different bacteria cause different degrees of inflammation reflected in a corresponding degree of the GFM expression, ME mucous cell metaplasia-hyperplasia changes, and bacteria-host responses. These findings are critical to have demonstrated definitively, as this data has the potential to influence future approaches to research, clinical thought processes and treatment strategies. Although our understanding of specific mechanisms in which mucins influence bacterial pathogenesis is incomplete, specific binding to mucins impacts bacterial persistence, clearance rates and pathogenesis [31,32]. Different binding affinities between mucins and bacteria were observed in an in vitro study demonstrating a difference among major OM pathogens in their adhesin binding affinity to different types of human mucins [33]. As these differences are considered, there is a potential need for a much deeper investigation into the individualized patient OM responses. For example, current SP vaccine strategies consider serotype virulence and antibiotic resistance in deciding on the serotype to be included in a specific vaccine. Data provided by studies such as this current investigation have the potential to provide data related to other aspects of pathogenesis, such as the propensity to: 1) form biofilms and influence MEM inflammatory responses, 2) influence mucin gene expression and 3) impact hearing post-infection, which is a critical factor to understand in patient clinical outcomes. A greater understanding of such factors across bacterial serotypes and strains should be pursued to guide both vaccine strategies and other clinical interventions.

This data set demonstrated measurable histologic changes including cell metaplasia/hyperplasia in the OM MEM. It has been demonstrated that ME bacteria activate cell-signaling cascades leading to further activation of inflammatory responses [34–38]. MEM cells then secrete host defense molecules which further stimulate proinflammatory cytokines and act as chemoattractants for neutrophils, mast cells, T cells and dendritic cells to assist in pathogen eradication [39,40]. These inflammatory cytokines have also been shown to induce the transformation of MEM enhancing proliferation of mucous producing cells [39,40]. Our laboratory and others have demonstrated that inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα [9,41,42], IL-1β [10], IL-6 [12], and IL-8 [43] upregulate mucin expression both in in vitro and in vivo. Together, the MEM transformation/metaplasia and the presence of inflammatory cytokines have been hypothesized to result in upregulation or hypersecretion of mucins. It should be noted that OM is a multifactorial disease. Other events such as tobacco exposure and gastroesophageal reflux disease have been noted to induce inflammatory responses which may influence the MEM changes and GFMs expression [44–46]. Tobacco exposure was also reported to impair ciliary function and potentially create environments leading to more chronic and persistent disease [47]. However, one advantage of controlled animal experiments such as this study is that such confounding factors are able to be eliminated and the results related only to bacterial pathogens are able to be evaluated. This study definitively demonstrated the correlation of ME epithelial cell metaplasia/hyperplasia and inflammation with upregulation of GFMs in vivo. Notably, different patterns of mucin expression induced by NTHi or SP were observed; with a more robust mucin upregulation in response to NTHi. This dataset is the first to demonstrate specific correlations across the ME GFMs and a differential response to various pathogens in vivo.

Biofilm formation is one of important hallmarks of chronic OM and is an important mechanism for bacterial persistence and survival during the disease [17,19]. The association of biofilm formation and mucin production has not been defined. This investigation demonstrated that ME biofilm formation is associated with elevated GFM expression in both NTHi and SP infections (Table 2). This is the first experimental evidence demonstrating a linkage between biofilm formation and mucin expression and is important data considering the importance of biofilms in chronic OM [17]. In other disease systems such as chronic rhinosinusitis there has also been a correlation between mucin production and biofilm formation which has been shown to enhance MUC5AC and MUC5B protein expression in nasal mucosa positive for biofilms compared with those without biofilms [48].

There are potential interactions between mucins and biofilms which warrant further exploration including: 1) the potential ongoing stimulation of a low-level inflammatory responses between the biofilm and MEM creating an ongoing mucin upregulation and 2) the connection between mucins and neutrophil extracellular traps (NET) which is a predominant element of in vivo biofilm structure [26]. Given that mucins are the primary cause of hearing loss in viscous ME fluid in children, it is important to have a more thorough understanding of bacterial behavior which may influence a continuing mucin upregulation and potentiate this hearing loss.

OM remains the most common childhood disorder for which antibiotics are prescribed. Emergence of antibiotic resistance in bacteria has made the treatment of OM more challenging. The utilization of antimicrobial therapy versus a “watchful waiting” strategy to decrease the overall use of antibiotics has been increasingly discussed with this increasing antibiotic resistance. [49–52]. Studies have demonstrated that with a high likelihood of true AOM diagnosis using strict criteria for otoscopic identification of this infection that there is substantial benefit to patients with immediate antibiotic treatment including a reduction in complications from the AOM episode and decreased middle ear effusion (MEE) persisting following the AOM episode [51,53]. This study is the first to demonstrate a direct and significant rapid reduction in mucin transcripts and complete return of MEM to its normal baseline state in subjects treated with antibiotics compared with controls in an in vivo OM model. These experimental data correlate well with clinical demonstration [51, 53] and provide a rationale for these improved outcomes, fewer complications and less effusions. With effective antimicrobial therapy for acute OM, the ME inflammatory response in muted, the MEM undergoes less metaplasia, thereby, there is a more limited and less prolonged mucin upregulation and secretion. These findings raise important questions related to OM pathogenesis and treatment. This dataset presents a clearer understanding of OM pathogenesis and MEM changes during OM and how the MEM moves from acute OM to more chronic OM with effusion. With this experimental data and previous clinical studies it is reasonable to suggest that, particularly in cases where an accurate diagnosis is assured, important benefits of treating patients with known AOM compared with “watchful waiting” can include the limitation of the potential chronic inflammatory pathways in the ME, the reduction in the formation of biofilms and limitation of the mucin upregulation which may lead to hearing loss. The findings from this investigation related to MEM pathogenesis may be particularly important in “at-risk” populations; children with family history of chronic OM, previous history of difficulty with OME, multiple previous infections, speech concerns, hearing concerns, other developmental difficulties or significant health issues. The data presented in this investigation also suggests that a personalize approach to OM requires further consideration, with an understanding of differential pathogen and host responses and particular host risk factors. Additional investigations are needed to further elucidate particular patient populations that benefit from particular interventions when an accurate AOM diagnosis can be made. Our laboratory recently published a direct correlation between persisting MUC5B upregulation in children with more severe hearing loss who require tympanostomy tube insertion [54]. The publication was the first demonstration of specific hearing-related changes in children with OME and genetic changes to mucin expression in the middle ear. Given that hearing loss is the OM complication with the greatest and most prevalent association with developmental concerns, and the finding of this current investigation that antibiotic therapy in the acute phase of OM reverses the impact of MUC5B expression, it would suggest that appropriate immediate antimicrobial therapy in documented AOM might be considered the preferred intervention for longer term hearing considerations in select populations. What is clearly needed for the future is improvement in diagnosis, including the ability to specifically identify potential pathogens noninvasively. In addition, there is a critical, ongoing need for studies that enhance the ability to predict which patients will benefit most from treatment and enhanced methods of follow-up. Fortunately, we are on the cusp of non-invasive technology that will allow demonstration of biofilm formation in the ME after AOM and potentially provide information related to bacterial pathogens [55]. Finally, there exists greater promise than ever that a personalized medicine approach using clinomic data (clinical data merged with a specific genomic, proteomic and other data) [56] will impact how we manage individual patients with OM to improve overall outcomes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [grant NIDCD: DC007903 (JEK)] and in part through funding provided by the Department of Otolaryngology and Communication Sciences, Medical College of Wisconsin.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

None of the authors of this manuscript have any financial or non-financial competing interests to disclose.

Portions of this manuscript were presented at the 18th Extraordinary Symposium on Recent Advances in Otitis Media, National Harbor, MD, June 7–11, 2015.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bluestone CD. Modern management of otitis media. Pediatr Clin North Am. 36(6) (1989):137–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein JO. Otitis media. Clin Infect Dis. 19(5) (1994):823–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson IG, Dunleavey J, Bain J, Robinson D. The natural history of otitis media with effusion—a three-year study of incidence and prevalence of abnormal tympanograms in four South West Hampshire infant and first schools. J Laryngol Otol. 108(11) (1994):930–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin J, Tsuprun V, Kawano H, et al. Characterization of mucins in human middle ear and Eustachian tube. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 280(6) (2001):L1157–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerschner JE. Mucin gene expression in human middle ear epithelium. Laryngoscope. 117(9) (2007):1666–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ubell ML, Khampang P, Kerschner JE. Mucin gene polymorphisms in otitis media patients. Laryngoscope. 120(1) (2010):132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerschner JE, Hong W, Khampang P, Johnston N. Differential response of gel-forming mucins to pathogenic middle ear bacteria. Int J Pediatr Otolaryngol. 78(8) (2014):1368–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerschner JE, Khampang P, Erbe CB, Kolker A, Cioffi JA. Mucin gene 19 (MUC19) expression and response to inflammatory cytokines in middle ear epithelium. Glycoconj J. 26(9) (2009):1275–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuel EA, Burrows A, Kerschner JE. Cytokine regulation of mucin secretion in a human middle ear epithelial model. Cytokine. 41(1) (2008):38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerschner JE, Yang C, Burrows A, Cioffi JA. Signaling pathways in interleukin-1beta-mediated middle ear mucin secretion. Laryngoscope. 116(2) (2006):207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerschner JE, Meyer TK, Burrows A. Chinchilla middle ear epithelial mucin gene expression in response to inflammatory cytokines. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 130(10) (2004):1163–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerschner JE, Meyer TK, Yang C, Burrow A. Middle ear epithelial mucin production in response to interleukin-6 exposure in vitro. Cytokine. 26(1) (2004):30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerschner JE, Meyer TK, Wohlfeill E. Middle ear epithelial mucin production in response to interleukin 1beta exposure in vitro. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 129(1) (2003):128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bluestone CD, Stephensen JS, Matin LM. Ten-year review of otitis media pathogens. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 11(8 suppl) (1992):S7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngo CC, Massa HM, Thornton RB, Cripps AW. Predominant bacteria detected from the middle ear fluis of children experiencing otitis media: A systematic review. PLoS One. 11(3) (2016):e0150949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Post JC. Direct evidence of bacterial biofilms in otitis media. Laryngoscope. 111(12) (2001):2083–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall-Stoodley L, Hu FZ, Gieseke A, et al. Direct detection of bacterial biofilms on the middle ear mucosa of children with chronic otitis media. JAMA. 296(2) (2006):202–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Post JC, Hiller NL, Nistico L, Stoodley P, Ehrlich GD. The role of biofilms in otolaryngologic infections: update 2007 . Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 15(5) (2007):347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakaletz LO. Bacterial biofilms in otitis media: evidence and relevance. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 26 (10 Suppl) (2007):S17–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caye-Thomasen P, Hermansson A, Bakaletz L, et al. Panel 3: Recent advances in anatomy, pathology, and cell biology in relation to otitis media pathogenesis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 148(4 Suppl) (2013):E37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan L, Psaltis A, Baker LM, McGuckin M, Rousseau K, Wormald PJ. Aberrant mucin glycoprotein patterns of chronic rhinosinusitis patients with bacterial biofilms. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 24(5) (2010):319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong W, Khampang P, Erbe C, Kumar S, Taylor SR, Kerschner JE. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae inhibits autolysis and fratricide of Streptococcus pneumoniae in vitro. Microbes Infect. 16(3) (2014):203–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison A, Dyer DW, Gillaspy A, et al. Genomic sequence of an otitis media isolate of nontypable Haemophilus influenza: comparative study with H. influenza serotype d, strain KW20. J Bacteriol. 187(13) (2005):4627–4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tettelin H, Nelson KE, Paulsen IT, et al. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science. 293(5529) (2001):498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong W, Mason K, Jurcisek J, Novotny L, Bakaletz LO, Swords WE. Phosphorylcholine decreases early inflammation and promotes the establishment of stable biofilm communities of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae strain 86–028NP in a chinchilla model of otitis media. Infect Immun. 75(2) (2007):958–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong W, Juneau RA, Pang B, Swords WE. Survival of bacterial biofilms within neutrophil extracellular traps promotes nontypeable Haemophilus influenza persisitence in the chinchilla model for otitis media. J Innate Immun. 1(3) (2009):215–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25(4) (2001):402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lundbo LF, Harboe ZB, Clausen LN, et al. Genetic variation in NFKBIE is associated with increased risk of pneumococcal meningitis in children. EBioMedicine. 3 (2015):93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lore NI, Iraqi FA, Bragonzi A. Host genetic diversity influences the severity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in the Collaborative Cross mice. BMC Genet. 16 (2015):106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizrachi-Nebenzahl Y, Lifshitz S, Teitelbaum R, et al. Differential activation of the immune system by virulent Streptococcus pneumoniae strains determines recovery or death of the host. Clin Exp Immunol. 134(1) (2003):23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Culp DJ, Robinson B, Cash MN, Bhattacharyya I, Stewart C, Cuadra-Saenz G. Salivary mucin 19 glycoproteins: innate immune functions in Streptococcus mutans-induced caries in mice and evidence for expression in human saliva. J Biol Chem. 290(5) (2015):2993–3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landry RM, An D, Hupp JT, Singh PK, Parsek MR. Mucin-Pseudomonas aeruginosa interactions promote biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. Mol Microbiol. 59(1) (2006):142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernstein JM, Reddy M. Bacteria-mucin interaction in the upper aerodigestive tract shows striking heterogeneity: implications in otitis media, rhinosinusitis, and pneumonia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 122(4) (2000):514–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caye-Thomasen P, Hernansson A, Tos M, Prellner K. Changes in goblet cell density in rat middle ear mucosa in acute otitis media. Am J Otol. 16(1) (1995):75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giebink GS. Otitis media: the chinchilla model. Microb Drug Resist. 5(1) (1999):57–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin J, Caye-Thomasen P, Tono T, et al. Mucin production and mucous cell metaplasia in otitis media. Int J Otolaryngol (2012):745325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song DH, Lee JO. Sensing of microbial molecular patterns by Toll-like receptors. Immunol Rev. 250(1) (2012):216–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olive C Pattern recognition receptors: sentinels in innate immunity and targets of new vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev Vaccines. 11(2) (2012):237–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang D, Liu ZH, Tewary P, Chen Q, de la Rosa G, Oppenheim JJ. Defensin participation in innate and adaptive immunity. Curr Pharm Des. 13(30) (2007):3131–3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sayeed S, Nistico L, St Croix C, Di YP. Multifunctional role of human SPLUNC1 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Infect Immun. 81(1) (2013):285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin J, Tsuboi Y, Rimell F, et al. Expression of mucins in mucoid otitis media. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 4(3) (2003):384–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawano H, Haruta A, Tsuboi Y, et al. Induction of mucous cell metaplasia by tumor necrosis factor alpha in rat middle ear: the pathological basis for mucin hyperproduction in mucoid otitis media. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 111(5 Pt 1) (2002):415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smirnova MG, Birchall JP, Pearson JP. In vitro study of IL-8 and goblet cells: possible role of IL-8 in the aetiology of otitis media with effusion. Acta Otolaryngol. 122(2) (2002):146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Preciado D, Lin J, Wuertz B, et al. Cigarette smoke activates NF kappa B and induces Muc5b expression in mouse middle ear cells. Laryngoscope. 2008. March;118(3):464–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crapko M, Kerschner JE, Syring M, et al. Role of extra-esophageal reflux in chronic otitis media with effusion. Laryngoscope. 2007. August;117(8):1419–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Block BB, Kuo E, Zalzal HG, et al. In vitro effects of acid and pepsin on mouse middle ear epithelial cell viability and MUC5B gene express. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010. January;136(1):37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang LF, White DR, Andreoli SM, et al. Cigarette smoke inhibits dynamic ciliary beat frequency in pediatric adenoid explants. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012. Apr;146(4):659–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mao YJ, Chen HH, Wang B, Liu X, Xiong GY. Increased expression of MUC5AC and MUC5B promoting bacterial biofilm formation in chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Auris Nasus Larynx. 42(4) (2015):294–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finkelstein JA, Metlay JP, Davis RL, Rifas-Shiman SL, Dowell SF, Platt R. Antimicrobial use in defined populations of infants and young children. Arch. Pediatr Adolesc Med. 154(4) (2000):395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coco AS. Cost-effectiveness analysis of treatment options for acute otitis media. Ann Fam Med. 5(1) (2007):29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tahtinen PA, Laine MK, Huovinen P, Jalava J, Ruuskanen O, Ruohola A. A placebo-controlled trial of antimicrobial treatment for acute otitis media. N Engl J Med. 364(2) (2011):116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kenna MA, Acute otitis media – the long and the short of it. N Engl J Med. 375(25) (2016):2492–2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoberman A, Paradise JL, Rockette HE, et al. Treatment of acute otitis media in children under 2 years of age. N Engl K Med. 364(2) (2011):105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samuels TL, Yan JC, Khampang P, et al. Association of gel-forming mucins and aquaporin gene expression with hearing loss, effusion viscosity and inflammation in otitis media with effusion. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 143(8) (2017):810–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monroy GL, Hong W, Khampang P, et al. Direct analysis of pathogenic structure affixed to the tympanic membrane during chronic otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 159(1) (2018):117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Issa NT, Byers SW, Dakshanamurthy S. Big data: the next frontier for innovation in therapeutics and healthcare. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 7(3) (2014):293–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.