Abstract

Introduction:

Youth in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) are at increased risk for poor mental health due to economic and social disadvantage. Interventions that strengthen families may equip children and adolescents with the supports and resources to fulfill their potential and buffer them from future stressors and adversity. Due to human resource constraints, task-sharing – delivery of interventions by non-specialists – may be an effective strategy to facilitate the dissemination of mental health interventions in low resource contexts. To this end, we conducted a systematic review of the literature on family-based interventions delivered in LMICs by non-specialist providers (NSPs) targeting youth mental health and family-related outcomes.

Methods:

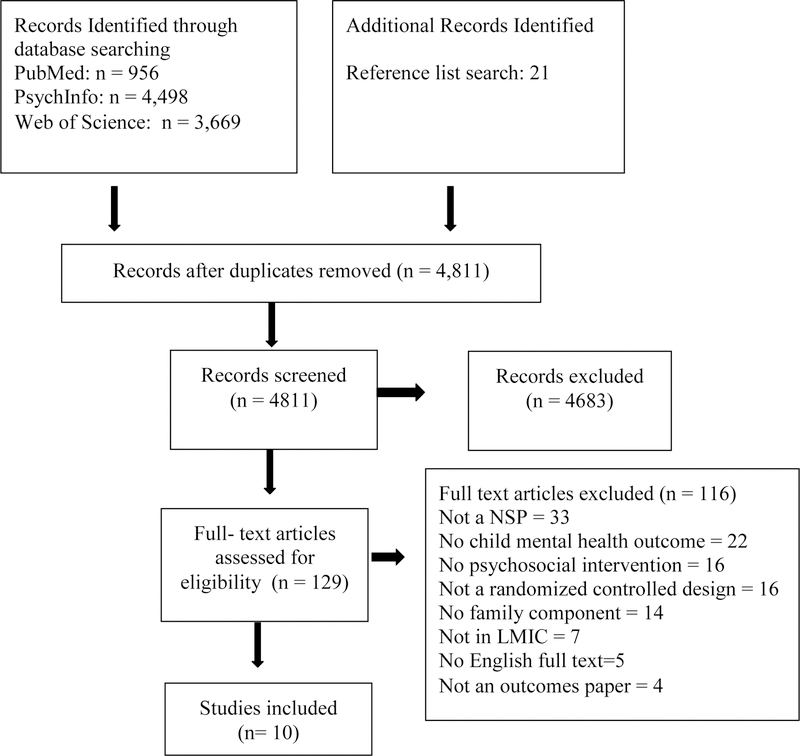

Cochrane and PRISMA procedures guided this review. Searches were conducted in PsychInfo, PubMed, and Web of Science, with additional articles pulled from reference lists.

Results:

This search yielded 10 studies. Four studies were developed specifically for the delivery context using formative qualitative research; the remaining interventions underwent adaptation for use in the context. All interventions employed a period of structured training; nine studies additionally provided ongoing supervision to counselors. Interventions noted widespread acceptance of program material and delivery by NSPs. They also noted the need for ongoing supervision of NSPs to increase treatment fidelity.

Discussion:

Usage of NSPs is quite consistently proving feasible, acceptable, and efficacious and is almost certainly a valuable component within approaches to scaling up mental health programs. A clear next step is to establish and evaluate sustainable models of training and supervision to further inform scalability.

Keywords: family-based interventions, global mental health, mental healthcare delivery, task sharing, training, supervision

Background

An estimated 10–20% of children and adolescents experience mental health problems worldwide (Kieling et al., 2011). Poor mental health in childhood is associated with myriad social and economic consequences across the lifespan, including delinquency, substance use, and poverty (Jenkins, Baingana, Ahmad, McDaid, & Atun, 2011; Kieling et al., 2011). Mental health treatment and prevention interventions lead to improvements not only in mental health but also in social functioning, academic and work performance, and general health behaviors (Barry, Clarke, Jenkins, & Patel, 2013; Jané-Llopis, Barry, Hosman, & Patel, 2005; Nores & Barnett, 2010). Therefore, addressing child and adolescent mental health has become an increasingly important part of the public health agenda in both High-Income Countries (HICs) and Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) as part of wider health promotion and development agendas (Miranda & Patel, 2005; US Department of Education, & US Department of Justice, 2000).

The family is uniquely placed to both buffer negative impacts of community stressors on youth emotional and physical health and to provide a supportive context to facilitate the treatment of youth mental health disorders. Initial evidence supports the efficacy of family-based programs for strengthening family-level mediators and improving youth mental health outcomes (Barry et al., 2013; Knerr, Gardner, & Cluver, 2013; Mejia, Calam, & Sanders, 2012). This is particularly relevant in LMICs, where youth are exposed to greater community-level risk factors for poor mental health, including economic and social disadvantage and community conflict (Kieling et al., 2011; Patel, Flisher, Hetrick, & McGorry, 2007).

Widespread dissemination of youth mental health programs has been hampered by public health challenges in LMICs, including weak health systems, lack of human and financial resources, and concentration of services in urban centers (Ngui, Khasakhala, Ndetei, & Roberts, 2010; Patel, Minas, Cohen, & Prince, 2013). These challenges lead to questions as to what treatments are most effective and feasible, who is best suited to provide mental healthcare, and where treatment should be provided.

One challenge facing widespread dissemination is concern over the cultural acceptability of evidence-based treatments in different populations. The process of cultural adaptation – the modification of interventions to ensure compatibility with cultural patterns, meanings, and values – is supported by the ecological validity perspective. This perspective suggests interventions that lack relevance to the needs and preferences of a subcultural group will be less acceptable (Bernal, Bonilla, & Bellido, 1995; Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey, & Domenech Rodríguez, 2009). However, critics note cultural adaptation may compromise fidelity and thus efficacy of an intervention (Castro, Barrera, & Holleran Steiker, 2010). Lau (2006) suggests that formative research should explore local risk or resilience processes associated with a clinical problem and that adaptation should occur if social validity of the intervention is likely to be poor, thus diminishing viability and acceptability. In addition to adaptations regarding cultural acceptability, interventions may also need to be adapted for provision by a range of providers and treatment settings.

The challenge of scaling up mental health services in LMICs also extends to questions of who should deliver care and where they should do this. Task-sharing has been a frequently proposed strategy to help overcome human resource shortages. Task-sharing describes the process of training and delegating tasks to less specialized workers, thus using human resources more efficiently and increasing healthcare coverage (Kakuma et al., 2011). Evidence suggests that individuals with no prior mental health training can effectively deliver psychological treatments to adults, with relatively minimal training and continued supervision in primary-care and community settings (Padmanathan & De Silva, 2013; van Ginneken et al., 2013). Proponents of integrating mental healthcare into primary care settings note the strong potential of this approach for improving access to mental healthcare, avoiding fragmentation of health services, reducing stigma, and providing patient-centered care (Patel, Belkin, et al., 2013).

Several key questions remain to be resolved for task-sharing research. The first regards how to balance aims of intervention fidelity and local adaptation. A second key question regards the appropriate balance of training providers in general clinical skills versus knowledge of specific intervention content. A final question is how to increase sustainability, for instance using models that employ tiered structures with local supervisors and apprenticeship of counselors (Murray et al., 2011) and integration into existing healthcare structures. In order to guide future implementation of prevention and treatment interventions in global mental health, it is important to explore what models of adaptation, training, and supervision have successfully been delivered in LMIC contexts.

Aims

This systematic review examines family-based interventions that (1) include a youth mental health outcome and were (2) provided by non-specialist providers (3) in LMICs. We describe development and adaptation processes, training and supervision, and findings related to feasibility and acceptability.

Methods

Search Strategy

This systematic review conforms to the guidelines outlined by the PRISMA 2009 checklist. A research protocol was published on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews website (registration number: CRD42017059896). A systematic search strategy was used to identify trials of family-based interventions addressing child and adolescent mental health delivered by a NSP in a LMIC. PsychInfo, PubMed, and Web of Science were searched with no time period limits using standardized search terms applied in a sequential, stepped approach (for example terms, see Appendix A). Additional studies were identified through reviewing references of key reviews (e.g., Barry et al., 2013).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligibility criteria arranged by the Patient/Problem/Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) model are presented in Table 1. Study type was limited to intervention, prevention, or promotion trials with a randomized-controlled design that a) targeted family processes, b) examined at least one child-level (ages 2–18 years) mental health outcome, and c) was delivered by a NSP. A NSP was defined as an individual with no prior structured training in mental health or prior credentials as a mental healthcare provider (van Ginneken et al., 2013). In line with a prior review (Barry et al., 2013), child and adolescent mental health included indicators of positive and negative mental health and well-being indicators. Only peer-reviewed studies in English were considered for inclusion. Purely self-help or support group interventions and studies exploring infant development (under age of 2 years) were excluded.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Topic | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Youth and families living in a low and middle-income country as defined by The World Bank Group in 2015 (World Bank, 2015) or at the time of the trial (e.g., trials conducted in Chile prior to Chile becoming a high-income country). Consistent with prior LMICs reviews (van Ginneken 2013), Taiwan was grouped with China, even though Taiwan is categorized as HIC. |

| Intervention | Psychosocial intervention, promotion and prevention programs that include a family component (e.g. targeted the parent-child relationship, household organization, or whole family functioning). Examples include universal health promotion programs, parenting programs, family therapy programs, and child mental health interventions with a family component. Self-help and support group interventions were excluded. Intervention providers were limited to non-specialist providers, as defined as an individual with no prior structured training in mental health or prior credentials as a mental health care provider. |

| Comparison | Only trials including random assignment and a control comparison group were included. |

| Outcome | Youth mental health included indicators of positive mental health such as self- esteem, self-efficacy, coping skills, resilience, emotional wellbeing; negative mental health such as depression, anxiety, psychological distress, suicidal behavior; and wellbeing indicators such as social participation, empowerment, communication and social support. |

Data Extraction

A five-person review team was trained on inclusion and exclusion criteria. All members reached 85% reliability before independently reviewing studies. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two team members to assess inclusion/exclusion. The lead author resolved all discrepancies. Full texts were then assessed for eligibility by the lead author and discussed by team members. Two team members extracted data independently using a pre- piloted standardized form, and the lead author resolved discrepancies.

Results

Search Results

The initial search identified 9,180 records, with 4,811 remaining after duplicates were removed. After full review, ten studies were selected for final inclusion (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search Flow Diagram

Intervention Trial Characteristics

Three interventions were conducted in South Africa and one each in Kenya, Thailand, Liberia, Democratic Republic of Congo, China, and Burundi. Additionally, one intervention was conducted in both Pakistan and India; however, outcome and process data are aggregated and therefore considered as a single intervention. Interventions consisted of eight prevention programs and two treatment interventions. All prevention interventions were provided to families and children experiencing known risk factors for poor mental health, including high HIV prevalence (Puffer et al., 2016; Bell et al., 2008), being part of a displaced or migrant population (Annan, Sim, Puffer, Salhi, & Betancourt, 2016), or living in an ongoing or post-conflict setting (O’Callaghan et al., 2014; Puffer et al., 2015). Five prevention interventions were open to all community members, while three targeted a subset of the population considered to be at increased risk. Target children ranged in age from 2–18 years, with two interventions focusing on early childhood (Puffer et al., 2015; Rahman et al., 2016). The majority of interventions (N = 8) included participation of both a caregiver and a child in the program; two interventions only provided intervention content to caregiver(s) (Puffer et al., 2015; Jordans et al., 2016). All interventions engaged both male and female caregivers except one, which specifically targeted HIV positive mothers (Eloff et al., 2014).

Intervention Development and Adaptation

To gather further information on intervention development and implementation, eight additional publications were reviewed that were cited in the main outcome papers; these publications provided more detail on six of the interventions (Li et al., 2011; Paruk, Petersen, & Bhana, 2009; Paruk, Petersen, Bhana, Bell, & McKay, 2005; I. Petersen et al., 2010; Inge Petersen, Mason, Bhana, Bell, & Mckay, 2006; Puffer, Pian, Sikkema, Ogwang-Odhiambo, & Broverman, 2013; Sim, Annan, Puffer, Salhi, & Betancourt, 2014; Visser et al., 2012).

Four interventions were developed specifically for the context in which they were provided (Eloff et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Puffer et al., 2015; Puffer et al., 2016). The remaining seven were adaptations of interventions that had been delivered elsewhere; these underwent adaptation to increase cultural fit and/or for delivery by a NSP (See Table 2). Common adaptation approaches included: qualitative investigation of risk and resilience factors, pilot testing with mixed-methods evaluation of cultural acceptability and feasibility, and consultation with local community leaders or experts. Similarly, all of the locally developed interventions utilized formative qualitative work and consultation with local community members and experts to develop the intervention. All interventions were provided in the local language. Additional common approaches included the use of cultural examples, metaphors, and local games or activities. Deeper-level adaptations included specifically targeting common stressors including poverty, displacement, or conflict; strengthening culturally grounded protective factors (e.g., social networks); and reducing culturally grounded risk factors (e.g., stigma or harsh discipline).

Table 2.

Characteristics of intervention development or adaptation

| Intervention | Developed or adapted | Development or adaptation approach | Culturally grounded adaptations or development considerations | Delivery Specific adaptions or considerations | Common elements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Annan et al., 2016 HFP |

Adapted | Adapted from Strengthening families program (Kumpfer & Bluth, 2004); formative qualitative study explored risk and protective factors related to family functioning, violence in the home, and child well-being | Provided in local language; modified names, examples and illustrations; explicitly recognized stressors of poverty and displacement; expanded content on caregiver stress and anger management; noted sensitivity to cultural norms around child-parent participation and dissent when discussing family communication; incorporated cultural values (e.g. metta “loving kindness”). | Expanded target age from 6–11 to 8–12; reduced number of session from 14 to 12 due to concerns over retention | LL, CE, M |

| Bell et al., 2008 CHAMPSA |

Adapted | Adapted from CHAMP; focused ethnographic study to explored interpersonal/family processes; adapted cartoon storyline using a participatory narrative method; focus groups with key informants to explored appropriateness of the content and exercises. Adapted intervention was piloted and focus groups provided feedback on each session leading to further adaptations. Adaption process was overseen by a CHAMPSA Board comprising of researchers, community leaders, and family members | Provided in local language; drafted new cartoon-based manual using culturally relevant story and new drawings; intervention targets individual, interpersonal/family and community processes found to contribute to HIV risk; content expanded to address stigma, bereavement due to high HIV prevalence rate; parent and child rights and responsibilities were addressed due to high levels of disempowerment | Due to cultural taboos, sensitive topics were introduced using a cartoon narrative and discussion around these topics was facilitated through the characters; community collaborative board was created to increase community cohesion and facilitate strengthening of the “community protective shield” | LL, CE |

| Bhana et al., 2014 VUKA |

Adapted | Multi-disciplinary team reviewed existing CHAMP, CHAMP+ and CHAMPSA materials; formative qualitative study explored challenges and protective influences for socio-emotional coping of HIV+ adolescents | Provided in local language; adapted cartoon storyline; altered curriculum to address challenges faces youth living with HIV including unfulfilled bereaving, difficulty accepting and dealing with identify and status related to living with HIV, high external stigma, discrimination and disclosure and difficulties in understanding ART and adherence | Developed for the delivery by lay facilitators including providing step by step guidance for lay counselors to deliver information and facilitate discussion | LL, CE |

| Eloff et al., 2014 | Developed | Formative qualitative research explored parenting context and the needs of HIV-affected children; piloted implementation of the intervention and conducted formative evaluation using observations and follow-up focus group discussion with participants leading to further intervention revisions | Provided in local language; used appropriate means of artistic expression (e.g. clay sculpting over drawing); used indigenous stories involving animals; included culturally important topics (e.g. family planning, ); attended to strengthening the mother-child relationship with the goal of bonding; focused on living positively; and addressing concerns about children’s futures | Shortened original number of sessions to reduce non-attendance; shortened child session length to facilitate retaining children’s attention | LL, CE, LA |

| Jordans et al., 2013 | Adapted | Adapted from a manual for children who have experienced violence (Macksoud, 2000) | Provided in local language | Not noted | |

|

Li et al., 2014 TEA |

Developed | Developed for specific context using two needs assessments, a feasibility pilot, and refinement of the manual during intervention training | Provided in local language and used local expressions; intervention components were developed to address needs and challenges faced by HIV families in the local culture and context including community stigma, and family in its role in supporting persons living with HIV | Developed for the delivery by lay facilitators including depth of material and length of sessions | LL, CE, M |

| O’Callaghan et al., 2014 | Adapted | The intervention was comprised of three components: 1) Chuo Cha Maisha-developed and piloted in Tanzania (Selvam, 2008); 2) Mobile cinema clips produced locally; 3) relaxation technique scripts used previously in DR Congo. | Provided in local language; used culturally familiar songs and games as warm-up activities; locally developed cinema clips addressed stigma, and discrimination towards formerly abducted children and their families | Addressed need for school resources and barriers to participant punctuality | LL, CE, LA |

|

Puffer et al., 2015 PMD |

Developed | Developed by reviewing existing evidence-based programming including the Nurturing Parenting Program (Bavolek, Comstock, & McLaughlin, 1983); formative qualitative research explored quality of parent-child relationships and common parenting practices | Provided in local language; used culturally relevant examples and illustrations Recognized culturally grounded caregiver roles in a family; addressed norms around harsh discipline. |

Developed for the delivery by lay facilitators; parenting group size was large (25–35) to accommodate serving more people with fewer resources | LL, CE |

|

Puffer et al., 2016 READY |

Developed | Developed specifically for context in collaboration with a local Community Advisory Committee (CAC) using community-based participatory methods; formative mixed-methods study explored psychosocial correlates of HIV risk; intervention was piloted in full before trial | Provided in local language, used skits and role plays developed specifically for the context to provide psychoeducation and model skills; all content developed to reflect cultural norms related to family functioning; explicitly recognizes stress due to poverty and social problems; treatment was structured around the culturally relevant metaphor of the family as a growing tree | Provided in churches, as they are trusted institutions where families gather together; manual and curriculum developed for lay providers (e.g. used non-technical language) | LL, CE, M, LA |

|

Rahman et al., 2016 PASS |

Adapted | Adapted from the Preschool Autism Communication Trial (PACT); formative qualitative research consisted of interviews with parents, stakeholder focus groups, expert-led simplification of the manual, intervention adaptation workshops, and case series delivered by specialists and non-specialist workers | Provided in local language; reframed “homework” as “home-practice”; used common games in the region; used common metaphors | Delivered PASS to family members besides parents; prepared scripts for non-specialist delivery; increased structured guidance for delivery of strategies; shortened intervention focusing on initial 6 months; simplified technical language for non-specialist delivery; increased length of training from 2-days in UK to 4 weeks | LL; M: LA |

Intervention Content and Strategies

All interventions except one (Rahman et al., 2016) provided treatment in a group context and thus were provided in common spaces including churches, schools, hospitals or clinics, and common community spaces (See table 3). The final, one-on-one, intervention was conducted either in families’ homes or a clinic (Rahman et al., 2016). None of the interventions were directly integrated into primary care services. On average, sessions were 90 minutes, and program duration spanned two weeks to 6 months. The average number of contact hours was 16.5 (range 6–30.35). Intervention content targeted the following risk factors: poverty, harsh or inconsistent parenting, alcohol abuse, and stigma. Additional content targeted positive parent- child communication and support, positive parenting, HIV risk factors, life skills, and coping skills. All interventions included didactic presentations of skills or psychoeducation. Interventions also incorporated local games, dramatic presentations of information, group discussion, storytelling, in-session practice (e.g. positive communication with child), home practice of newly acquired skills, and feedback and praise to empower parents to change patterns of parent-child interaction.

Table 3.

Intervention content and strategies

| Intervention | Primary Intervention Aims | Setting | Intervention Participants | Format | Frequency | Contact hours | Content | Core intervention strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Annan et al., 2016 HFP |

Decrease harsh discipline, increase positive parenting and improve family functioning, | Community meeting place (e.g. community halls or schools) | Primary caregiver(s); up to 2 children per family | 2 hour program: 60 min caregiver and child separate groups, 60 min family practice of skills | 12 weekly sessions | 24 | Parenting skills, social skills (youth) | Didactics, demonstrations, role plays, in session practice of communication and parenting skills, feedback from facilitators, structured and unstructured play (positive family interactions) |

| Bell et al., 2008 CHAMPSA |

Reduce HIV risk behaviors through strengthening families | Schools | Caregiver(s); target child | 90 minute group sessions | 10 weekly sessions | 15 | HIV knowledge, authoritative parenting, caregiver decision-making and caregiver monitoring of children; family communication (eg. concerning sexuality and risky behaviors); | Review of cartoon-based manual, group discussion |

| Bhana et al., 2014 VUKA |

Promote health and well-being of youth born with HIV | Community hospital | Primary caregiver; target child | 2-hour program: Multiple-family group activities and separate parent child activities | 6 bi-monthly sessions | 12 | HIV education; Youth identity, acceptance and coping with HIV; caregiver child communication; risk reduction; social support | Review of cartoon based manual, discussions and problem-solving within and between families in multi-family groups |

| Eloff et al., 2014 | Promote resilience among young children of HIV positive mothers | Community | Mother; target child | 75 minute sessions: first 14 session mothers and children were in separate co-occurring groups, 10 interactive sessions | 24 weekly sessions | 30.35 | Mothers sessions: issues related to living with HIV, and parenting Children’s sessions: self-esteem and interpersonal and practical life skills. | Didactics, experiential learning activities (eg. board games, story telling, and traditional cultural games and group discussions), modeling of positive parent behaviors, in session skills practice, |

| Jordans et al., 2013 | Reduce child mental health symptoms | Community | Primary caregiver | One 2.5 hour and one 3.5 hour meeting with groups of 20 parents | 2 weekly sessions | 6 | Problems Affecting Children (Alcoholism of Parents, Maltreatment, Gang-Formation); Parent-Child Communication, Managing Child Problems without harsh punishment | Didactics, normalization of problems, providing relief to parents, modification of the problem through corrective information, augmenting help seeking and empowerment of participants thought a focus on self-help strategies |

|

Li et al., 2014

TEA |

Strengthen families living with HIV | Community | All family members; structured activities for caregivers only | 2 hour small group sessions; community events | 6 small group sessions with home practice; 3 community events over 10 weeks | 12 plus commun ity event | General health, coping skills, positive family interactions and quality of life | Didactics, role plays, home practice, community events |

| O’Callaghan et al., 2014 | Improve mental health and psychosocial outcomes of war-affected youth | Churches | Target child; primary caregiver | 2 hour session three times a week | 8 session over three weeks | 16 | Youth life skills (eg. effective communication, and conflict resolution strategies), relaxation techniques, stigma and discrimination towards formally abducted children, effective parenting | Didactics (psychoeducation), participant modeling of TF-CBT relaxation techniques, small group discussion, drama, whole group brain-storming and mobile cinema |

|

Puffer et al., 2015 PMD |

Reduce harsh discipline; increase positive parenting; improve caregiver-child interactions | Community meeting place (e.g., schools) | Primary caregiver(s) | 2 hour group sessions (20–35 caregivers), one home visit per family during intervention | 10 sessions over 13 weeks | 21 | Child development; Positive parenting, parent promotion of cognitive and academic skills; malaria prevention | Didactics, discussion, modeling, in-session skills practice |

|

Puffer et al., 2016 READY |

Improve family relationships; reduce HIV risk; promote mental health | Churches | All interested family members | 2 hour program: 60 min family session, concurrent 60 min adolescent (gender segregated) and caregiver sessions (30 min couples, 30 min gender – segregated support groups); 20–25 families in groups | 9 weekly sessions | 18 | Economic empowerment; building emotional supportiveness; HIV education and prevention | Didactics, role-plays and skits, demonstrations, group discussion, in-session skills practice focusing on family communication, provision of feedback from facilitators |

|

Rahman et al., 2016 PASS |

Scaffolding and developing communicati on skills in children with autism spectrum disorder | Clinic or home | Caregiver; target child | 60 minute family sessions | 12 bi-monthly sessions (6 months) | 12 | Early social communication skills, synchronous communication and interaction | Video-Feedback Routine, Action Routines, familiar repetitive language, and pauses |

NSP Training and Supervision

Provider characteristics.

Reasons for using NSPs included trying to develop a sustainable intervention model (Annan et al., 2016; Bhanan et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Jordans et al., 2013; Bell et al., 2008; Rahman et al., 2016) and provision by a NSP was less stigmatizing and therefore increased both access to the community and potentially increased efficacy (O’Callaghan et al., 2014; Bell et al., 2008). Providers included community members, lay counselors including local NGO workers, and teachers (Table 4). Two studies noted requiring the provider to have at least 12 years of education (Rahman et al., 2014; Eloff et al., 2014), and two studies noted selecting both male and female providers and utilizing gender-matched providers for sensitive or difficult discussions (Puffer et al., 2016: O’Callaghan et al., 2014). Limited documentation was provided on salary, with five interventions noting providers delivered the intervention as part of their occupation.

Table 4.

NSP training and supervision

| Intervention | Facilitator Type | Training Length and Trainer | Training Description | Supervision length/freq and Supervisor | Supervision Description | Treatment fidelity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Annan et al., 2016 HFP |

NGO staff and community members with reading/writing ability and prior experience with migrant community | 5 days; Psychologist (HIC) 6 days refresher training (NGO Staff | Didactic presentation of material; demonstrations; role plays; practice sessions; feedback and discussions of challenges during refresher trainings. | Every 2–3 weeks NGO staff (HIC); Individualized coaching as needed | Direct observation with standardized checklist to provide tailored supervision and coaching | Fidelity checklist of all session components |

| Bell et al., 2008 CHAMPSA |

Community caregivers | Not reported | Didactic presentation of purpose and content of each session; participatory and experiential methods; feedback on facilitation skills; practice sessions | Weekly | Group debriefing sessions, workshops on stress management, dealing with grief and bereavement and importance of boundaries and containment when working as a facilitator | Facilitators observed periodically |

| Bhana et al., 2014 VUKA |

Lay health workers at local HIV clinic | 2 days; counseling psychologist (HIC) | Trained on manual, counseling skills, and management of group dynamics; role play | Biweekly (2hrs); Masters level Psychologist | Review of fidelity checklist and areas for improvement; refresher training for upcoming sessions | Fidelity checklist |

|

Eloff et al., 2014 Kgolo Mmogo |

Lay health workers providing care to HIV-affected mothers and children. | 10 days; Social Worker | Didactic presentation of information about HIV/AIDS and skills for counseling, facilitating groups, and identification and management of children’s emotional and behavioral problems | Weekly then biweekly; supervisors available daily as needed; Social Worker (individual) and Psychologist (group) | Individual supervision until lay health worker reached threshold; group supervision by the site specialists; discussed progress and necessary tailoring of the intervention | Quality assurance questionnaire per session (self) |

| Jordans et al., 2013 | Lay community counselors, mostly BA-level | 2 days as part of 3 week psychosocial training; Psychologist (LIC) | Intervention content; basic therapeutic skills; training on additional battery of intervention; classroom instruction, role-plays, group discussion | Biweekly; Psychologist (LIC) | Group supervision, discussion of difficulties observed during implementation | None collected |

|

Li et al., 2014 TEA |

NGO health educators at provincial, county, and township levels | One-week; central training team | Didactic presentation; mock practice sessions | Before/after all intervention activities; in-country investigators and facilitator team leaders | Preparation before intervention and summary after the intervention activities | Checklist for supervisors and observers |

| O’Callaghan et al., 2014 | Lay facilitators recruited from a Congolese-based NGO’s staff | 6 days; Psychologist (HIC) | Trained on manual and video materials; feedback to make each module culturally relevant; role plays | Weekly (3–4 hours); Psychologist (HIC) | Meeting before each session; review previous module; prepare for subsequent module | Researcher attended sessions and ensured all modules were covered |

|

Puffer et al., 2015 PMD |

Lay providers with reading/writing ability and some previous facilitation experience | 5 days; NGO staff | Didactic presentation of material; group discussions; role plays | Occasional; NGO staff | Group debriefing sessions; consultation with trainer as needed. | Fidelity checklist of all session components (self); occasional external observer |

|

Puffer et al., 2016 READY |

Community members | 5 days; Psychologist (HIC) | Didactic presentation of material; demonstrations; role plays; practice sessions | Weekly (4–6 hours); Psychologist (HIC) / Peer | Group meetings to practice for each weekly session; included peer and trainer feedback on areas for improvement; trainer involvement decreased over time | Local member of research team observed each session and tracked completion of activities, facilitation quality and participant responses |

|

Rahman et al., 2016 PASS |

Health worker with college education (not required) who showed commitment, interest, and could communicate well | 10 days; Study Team (HIC) | Didactic presentation; role playing; observation; practice cases | Weekly; Local specialist | UK team provided online support to local specialist; local specialists provided one-on-one supervision until lay health worker reached threshold. Group supervision continued throughout and consisted of discussion ongoing problems and tailoring of the intervention | Assessed by UK therapy experts, rated videos of 10% (36 of 360) of treatment sessions using DCMA, randomly selected across health workers and stages of treatment |

Provider training.

All interventions included an initial phase of didactic training on intervention content and/or the intervention manual. Additional training strategies included role- playing, practice sessions, and provision of structured feedback. Researchers played a role in the training of providers in all of the interventions. Initial training duration ranged from two to ten days. One study noted providers received a three-week training on basic counseling skills in addition to training on the specific intervention protocol (Jordans et al., 2013).

Provider supervision.

Supervision of providers varied widely in structure and intensity. Nine interventions reported providing weekly group supervision. In addition, two of these noted providing one-on-one supervision until providers reached a predetermined fidelity threshold (Rahman et al., 2016; Eloff et al., 2014). Across interventions, group supervision primarily consisted of reviewing previous sessions, reviewing material for upcoming sessions, troubleshooting, and discussing ongoing intervention adaptations. Individual supervision consisted of providing direct feedback on provider competency or treatment fidelity.

Supervisors consisted of local professionals including NGO staff or UK- or US-based professionals who provided on-site supervision as their role in the study team. One study noted using a tiered implementation structure consisting of UK-based experts training and supervising local health professionals, who in turn trained and supervised lay providers. During the trial, UK-based experts provided phone or online-based supervision to local health professionals (Rahman et al., 2016).

Feasibility/Acceptability

Feasibility of utilizing NSPs was primarily measured by provider fidelity to the intervention content. High levels of treatment fidelity were noted in six interventions, and one noted concerns over low fidelity. Acceptability was assessed by treatment attendance, structured participant report, and structured and unstructured community report. Two studies noted difficulty with inconsistent (Puffer et al., 2016) or poor attendance (Eloff et al., 2014), and four studies noted high rates of attendance (Annan et al., 2016; Bhana et al., 2014; Puffer et al., 2015; O’Callaghan et al., 2014). The one study that noted providing a structured assessment of participant perception of the program reported high levels of participant satisfaction (Jordans et al., 2013). Additional indicators of program acceptability included community interest in participating in the intervention and acceptance of program content by community leaders.

Implementation Challenges

Authors reported challenges on the structural, organizational, and participant level. Structural challenges included public service strikes, electricity outages, and outbreaks of violence in vicinity of the project. Additionally, programs struggled to provide referrals for individuals with higher levels of symptom severity due to the broader health system lacking adequate services. Organizational challenges included obtaining private space for sessions, obtaining appropriate administrative permissions when integrating into hospital services, managing provider expectations on reimbursement, and finding appropriate time to provide the intervention. Participant-centered challenges included language and educational diversity of participants.

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to synthesize adaptation and implementation processes of family-based interventions for youth mental health in LMICs. This is a growing area of interest and research, as evidenced by the fact that the vast majority of studies in the review were published since 2013. The majority of interventions focused on the prevention of mental health disorders in at-risk populations, while two interventions targeted youth with an existing mental health problem.

Intervention Adaptation and Content

All of the interventions, both those adapted from other interventions and those developed for the specific context, incorporated evidence-based strategies previously evaluated in HICs. For instance, the majority of interventions included teaching behavioral parenting strategies. The majority also included strategies associated with skills generalization, including in-session and at home practice, which have been previously shown to increase efficacy (Hertzman & Wiens, 1996). Overall, approaches described in the reviewed studies were quite similar to those used in HICs; a review of youth mental health prevention programs in HICs found that common approaches consisted of parent training, child social skills training, and universal cognitive behavioral programs (Waddell, Hua, Garland, Peters, & McEwan, 2007). In LMICs, however, parental training was more common, while CBT-related strategies were less common. This could be due to limiting our review to randomized controlled trials, as additional family-based CBT informed interventions have been evaluated using non-experimental or quasi-experimental designs (de Souza et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2013; Ozdemir, 2008; Rajaraman et al., 2012).

In making adaptations to existing strategies or interventions, formative research was very common. All of the interventions developed for a specific context utilized formative qualitative work, as did almost half of the adapted studies. Related to specific content adaptations, Bernal’s framework (1995) for cultural adaptation of psychosocial interventions suggests adaptations across the following domains: language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and context. All adapted interventions addressed language, persons, content, and context. Only one intervention (Annan et al., 2016) appeared to address all domains. Intervention content and strategies did not appear to differ across developed verses adapted interventions.

Use of Non-Specialist Providers

Community acceptability and high program attendance reported by many of the included studies appear to support the hypothesis that utilizing NSPs can increase access and uptake of interventions in LMICs. Additionally, all of the programs that reported providing structured trainings and ongoing supervision reported high treatment fidelity. Models of training and supervision ranged from a brief training and minimal supervision to intensive training and oversight, which brings into question sustainability. Continual involvement of mental health professionals from HICs - or perhaps even involvement of highly trained professionals in LMICs - is likely not sustainable long-term and outside of the context of external funding. This aligns with the apprenticeship model, which suggests that involvement of highly trained professionals should be limited to initial training of providers and supervisors (Murray et al., 2011). More sustainable methods of supervision may include models of peer supervision (Remley, Benshoff, & Mowbray, 1987). Additionally, concerns over sustainability call for exploring the utility of digital health strategies that are filling human resource gaps in other global public health systems (Luxton, McCann, Bush, Mishkind, & Reger, 2011).

Studies noted the need for providers to have not only knowledge of program content but interpersonal skills associated with effectively managing group dynamics and challenging interpersonal interactions. This raises the important question of training providers on specific protocols versus general skills. In all the prevention interventions, training primarily focused on content over clinical skill, which aligns with prevention approaches that have foundational didactic content and structured discussion and activities. The two treatment interventions focused on both content and clinical competency. Competencies-based models of training focus on training healthcare workers on basic clinical skills and specific therapeutic approaches (e.g., CBT) (Kutcher, Chehil, Cash, & Millar, 2005). This approach is more commonly used for training providers in the primary healthcare system. Utilization of both program fidelity and therapist competence measures will allow for testing of provider-specific characteristics associated with participant outcomes, as well as the impact of different training and supervision models on therapist skills.

Finally, the generally high acceptability and feasibility of family-based interventions delivered by NSPs supports expanding reliance on NSPs. However, the lack of reporting on costs associated with providing a psychosocial intervention limits the field’s ability to make fully informed judgments concerning the feasibility and sustainability of interventions in low-resource contexts. Therefore, future studies should consider reporting intervention implementation costs. Additionally, expanding reliance on NSPs requires critically exploring the strength of structural supports for NSPs. Most NSPs in this review were associated with and supported by NGOs. In fact, the promise of building sustainable models may relate to the strength of NSPs’ structural supports (e.g., primary healthcare setting, community-based organizations, religious congregations). Therefore, strategies are needed to strengthen this level of the system as well. One major strategy for increasing access to care is to integrate mental healthcare into primary care settings in LMICs. Initial evidence supports this approach as both efficacious and cost-effective (Lund, Tomlinson, & Patel, 2016). This may be a good strategy for family-based interventions as well; however, it has yet to be fully explored. Although primary healthcare services tend to be individually-focused, when children are the patients, parents are often present, making the healthcare environment a potentially promising point of first contact. This strategy of integrating family-based work into primary care may be especially relevant when (a) addressing concerns related to handling chronic health conditions of children or caregivers – challenges that often affect relationships and parenting or (b) when children are presenting with unexplained physical injuries that may indicate problems with violence in the home.

Study limitations

This systematic review has important limitations. The scope of the search excluded grey literature and only included studies published in English. Formative studies utilizing a qualitative or non-experimental design were excluded from the main search, which could have informed conclusions on the heterogeneity of intervention content, development, and implementation.

Conclusion

This systematic review explored the growing field of family-based interventions provided by NSPs for youth mental health in LMICs. Results point to the acceptability of family- based interventions in diverse cultural contexts, which may be related to the use of local NSPs and integration of culturally grounded material. Usage of NSPs is quite consistently proving feasible, acceptable, and efficacious and is almost certainly a valuable component within approaches to scaling up mental health programs. A clear next step is to establish and evaluate sustainable models of training and supervision to further inform scalability.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Elsa A. Healy, Duke University, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience.

Bonnie N. Kaiser, Duke Global Health Institute.

Eve S. Puffer, Duke University, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Duke Global Health Institute.

References

- Aarø LE, Mathews C, Kaaya S, Katahoire AR, Onya H, Abraham C, … de Vries H (2014). Promoting sexual and reproductive health among adolescents in southern and eastern Africa (PREPARE): project design and conceptual framework. BMC Public Health, 14, 54 10.1186/1471-2458-14-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annan J, Sim A, Puffer ES, Salhi C, & Betancourt TS (2016). Improving Mental Health Outcomes of Burmese Migrant and Displaced Children in Thailand: a Community-Based Randomized Controlled Trial of a Parenting and Family Skills Intervention. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research 10.1007/s11121-016-0728-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Barry MM (2008). The influence of social, demographic and physical factors on positive mental health in children, adults and older people Retrieved from https://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/handle/10379/2684

- Barry MM, Clarke AM, Jenkins R, & Patel V (2013). A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 835 10.1186/1471-2458-13-835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Bonilla J, & Bellido C (1995). Ecological Validity and Cultural Sensitivity for Outcome Research: Issues for the Cultural Adaptation and Development of Psychosocial Treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology; New York, 23(1), 67–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2009). Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 361–368. 10.1037/a0016401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, & Holleran Steiker LK (2010). Issues and Challenges in the Design of Culturally Adapted Evidence-Based Interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 213–239. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza MAM, Salum GA, Jarros RB, Isolan L, Davis R, Knijnik D, … Heldt E (2013). Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for youths with anxiety disorders in the community: effectiveness in low and middle income countries. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 41(3), 255–264. 10.1017/S1352465813000015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eloff I, Finestone M, Makin JD, Boeving-Allen A, Visser M, Ebersöhn L, … Forsyth BWC (2014). A randomized clinical trial of an intervention to promote resilience in young children of HIV-positive mothers in South Africa. AIDS (London, England), 28 Suppl 3, S347–357. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzman C, & Wiens M (1996). Child development and long-term outcomes: a population health perspective and summary of successful interventions. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 43(7), 1083–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jané-Llopis E, Barry M, Hosman C, & Patel V (2005). Mental health promotion works: a review. Promotion & Education, 12(2_suppl), 9–25. 10.1177/10253823050120020103x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins R, Baingana F, Ahmad R, McDaid D, & Atun R (2011). Social, economic, human rights and political challenges to global mental health. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 8(2), 87–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuma R, Minas H, van Ginneken N, Dal Poz MR, Desiraju K, Morris JE, … Scheffler RM (2011). Human resources for mental health care: current situation and strategies for action. Lancet, 378(9803), 1654–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61093-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, … Wang PS (2009). The global burden of mental disorders: An update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys. Epidemiologia E Psichiatria Sociale, 18(1), 23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, … Rahman A (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet, 378(9801), 1515–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knerr W, Gardner F, & Cluver L (2013). Improving Positive Parenting Skills and Reducing Harsh and Abusive Parenting in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Prevention Science, 14(4), 352–363. 10.1007/s11121-012-0314-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutcher S, Chehil S, Cash C, & Millar J (2005). A competencies-based mental health training model for health professionals in low and middle income countries. World Psychiatry, 4(3), 177–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS (2006). Making the Case for Selective and Directed Cultural Adaptations of Evidence- Based Treatments: Examples From Parent Training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(4), 295–310. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00042.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Liang L-J, Ji G, Wu J, & Xiao Y (2014). Effect of a Family Intervention on Psychological Outcomes of Children Affected by Parental HIV. Aids and Behavior, 18(11), 2051–2058. 10.1007/s10461-014-0744-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Tomlinson M, & Patel V (2016). Integration of mental health into primary care in low- and middle-income countries: the PRIME mental healthcare plans. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(Suppl 56), s1–s3. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxton DD, McCann RA, Bush NE, Mishkind MC, & Reger GM (2011). mHealth for mental health: Integrating smartphone technology in behavioral healthcare. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(6), 505–512. 10.1037/a0024485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia A, Calam R, & Sanders MR (2012). A Review of Parenting Programs in Developing Countries: Opportunities and Challenges for Preventing Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties in Children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15(2), 163–175. 10.1007/s10567-012-0116-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda JJ, & Patel V (2005). Achieving the Millennium Development Goals: Does Mental Health Play a Role? PLOS Medicine, 2(10), e291 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Dorsey S, Bolton P, Jordans MJ, Rahman A, Bass J, & Verdeli H (2011). Building capacity in mental health interventions in low resource countries: an apprenticeship model for training local providers. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 5, 30 10.1186/1752-4458-5-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Familiar I, Skavenski S, Jere E, Cohen J, Imasiku M, … Bolton P (2013). An evaluation of trauma focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children in Zambia. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(12), 1175–1185. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngui EM, Khasakhala L, Ndetei D, & Roberts LW (2010). Mental disorders, health inequalities and ethics: A global perspective. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 22(3), 235–244. 10.3109/09540261.2010.485273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nores M, & Barnett WS (2010). Benefits of early childhood interventions across the world: (Under) Investing in the very young. Economics of Education Review, 29(2), 271–282. 10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan P, Branham L, Shannon C, Betancourt TS, Dempster M, & McMullen J (2014). A pilot study of a family focused, psychosocial intervention with war-exposed youth at risk of attack and abduction in north-eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(7), 1197–1207. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir S (2008). EVALUATION OF THE FIRST STEP TO SUCCESS Early Intervention Program with Turkish Children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Sunal CS & Mutua K, Eds.). Charlotte: Information Age Publishing-Iap. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanathan P, & De Silva MJ (2013). The acceptability and feasibility of task-sharing for mental healthcare in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 97, 82–86. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paruk Z, Petersen I, & Bhana A (2009). Facilitating health-enabling social contexts for youth: qualitative evaluation of a family-based HIV-prevention pilot programme. Ajar- African Journal of Aids Research, 8(1), 61–68. 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.1.7.720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paruk Z, Petersen I, Bhana A, Bell C, & McKay M (2005). Containment and contagion: How to strengthen families to support youth HIV prevention in South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research, 4(1), 57–63. 10.2989/16085900509490342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Belkin GS, Chockalingam A, Cooper J, Saxena S, & Unützer J (2013). Grand Challenges: Integrating Mental Health Services into Priority Health Care Platforms. PLoS Med, 10(5), e1001448 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, & McGorry P (2007). Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. The Lancet, 369(9569), 1302–1313. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Minas H, Cohen A, & Prince MJ (Eds.). (2013). Global Mental Health: Principles and Practice (1 edition). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Bhana A, Myeza N, Alicea S, John S, Holst H, … Mellins C (2010). Psychosocial challenges and protective influences for socio-emotional coping of HIV+ adolescents in South Africa: a qualitative investigation. AIDS Care, 22(8), 970–978. 10.1080/09540121003623693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Mason A, Bhana A, Bell CC, & Mckay M (2006). Mediating Social Representations Using a Cartoon Narrative in the Context of HIV/AIDS The AmaQhawe Family Project in South Africa. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(2), 197–208. 10.1177/1359105306061180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puffer ES, Green EP, Chase RM, Sim AL, Zayzay J, Friis E, … Boone L (2015). Parents make the difference: a randomized-controlled trial of a parenting intervention in Liberia. Global Mental Health, 2, e15 (13 pages). 10.1017/gmh.2015.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puffer ES, Green EP, Sikkema KJ, Broverman SA, Ogwang-Odhiambo RA, & Pian J (2016). A church-based intervention for families to promote mental health and prevent HIV among adolescents in rural Kenya: Results of a randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(6), 511–525. 10.1037/ccp0000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puffer ES, Pian J, Sikkema KJ, Ogwang-Odhiambo RA, & Broverman SA (2013). Developing a Family-Based Hiv Prevention Intervention in Rural Kenya: Challenges in Conducting Community-Based Participatory Research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 8(2), 119–128. 10.1525/jer.2013.8.2.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Divan G, Hamdani SU, Vajaratkar V, Taylor C, Leadbitter K, … Green J (2016). Effectiveness of the parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder in south Asia in India and Pakistan (PASS): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 3(2), 128–136. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00388-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaraman D, Travasso S, Chatterjee A, Bhat B, Andrew G, Parab S, & Patel V (2012). The acceptability, feasibility and impact of a lay health counsellor delivered health promoting schools programme in India: a case study evaluation. Bmc Health Services Research, 12, 127 10.1186/1472-6963-12-127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remley TP, Benshoff JM, & Mowbray CA (1987). A Proposed Model for Peer Supervision. Counselor Education and Supervision, 27(1), 53–60. 10.1002/j.1556-6978.1987.tb00740.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, … Underhill C (2007). Global Mental Health 5 - Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet, 370(9593), 1164–1174. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61263-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, & Whiteford H (2007). Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. The Lancet, 370(9590), 878–889. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim A, Annan J, Puffer E, Salhi C, & Betancourt T (2014). Building Happy Families: Impact evaluation of a parenting and family skills intervention for migrant and displaced Burmese families in Thailand New York, NY: International Rescue Committee. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Education, & US Department of Justice. (2000). Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health: A National Action Agenda Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44233/ [Google Scholar]

- van Ginneken N, Tharyan P, Lewin S, Rao GN, Meera SM, Pian J, … Patel V (2013). Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological and substance-abuse disorders in low- and middle-income countries. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (11), CD009149. 10.1002/14651858.CD009149.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M, Finestone M, Sikkema K, Boeving-Allen A, Ferreira R, Eloff I, & Forsyth B (2012). Development and piloting of a mother and child intervention to promote resilience in young children of HIV-infected mothers in South Africa. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35(4), 491–500. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell C, Hua JM, Garland OM, DeV Peters R, & McEwan K (2007). Preventing Mental Disorders in Children: A Systematic Review to Inform Policy-Making. Canadian Journal of Public Health / Revue Canadienne de Sante’e Publique, 98(3), 166–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.