Abstract

Background/Aim:

The MsFLASH (Menopause Strategies: Finding Lasting Answers for Symptoms and Health) Network recruited into five randomized clinical trials (n=100-350) through mass mailings. The fifth trial tested two interventions for postmenopausal vulvovaginal symptoms (itching, pain, irritation, dryness, or pain with sex), and thus required a high level of sensitivity to privacy concerns. For this trial, in addition to mass mailings we pilot tested a social media recruitment approach. We aim to evaluate the feasibility of recruiting healthy midlife women with bothersome vulvovaginal symptoms to participate in the Vaginal Health Trial through Facebook advertising.

Methods:

As part of a larger advertising campaign that enrolled 302 postmenopausal women for the 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Vaginal Health Trial from April 2016 to February 2017, Facebook advertising was used to recruit 25 participants. The target population for recruitment by mailings and by Facebook ads included women aged 50-70 years and living within 20 miles of study sites in Minneapolis, MN and Seattle, WA. Design of recruitment letters and Facebook advertisements was informed by focus group feedback. Facebook ads were displayed in the “newsfeed” of targeted users and included a link to the study website. Response rates and costs are described for both online ads and mailing.

Results:

Facebook ads ran in Minneapolis for 28 days and in Seattle for 15, with ads posted and removed from the site as needed based on clinic flow and a set budget limit. Our estimated Facebook advertising reach was over 200,000 women; 461 women responded and 25 were enrolled at a cost of $14,813. The response rate per estimated reach was 0.22%; costs were $32 per response and $593 per randomized participant. The social media recruitment results varied by site, showing greater effectiveness in Seattle than Minneapolis. We mailed 277,000 recruitment letters; 2,166 women responded and 277 were randomized at a cost of $98,682. The response rate per letter sent was 0.78%; costs were $46 per response and $356 per randomized participant. Results varied little across sites.

Conclusions:

Recruitment to a clinical trial testing interventions for postmenopausal vaginal symptoms is feasible through social media advertising. Variability in observed effectiveness and costs may reflect the small sample sizes and limited budget of the pilot recruitment study.

Keywords: Recruitment, clinical trial, social media, postmenopausal, vaginal symptoms, midlife women

Introduction

The reach of social media such as Facebook holds promise for clinical trial recruitment and participation of healthy volunteers. Sixty-five percent of US adults reported use of social networking sites at the time of planning the Vaginal Health Trial in 2015, the most commonly used of which is Facebook.1 Although young adults (aged 18-29) are more likely to use social media (90%), compared to 51% of adults aged 50-64 and 35% of adults 65 and older, its use is widespread across gender and racial/ethnic groups.1

Many researchers have successfully used social media for clinical trial recruitment,2–5 although results on efficacy and cost-effectiveness have been mixed. For example, while some have found Facebook advertising to be cost-effective, in a study of cancer survivors Juraschek et al.6 found similar costs when comparing conventional (e.g., advertisements in periodicals, community health fairs, direct mailing) to online methods (Facebook sidebar ads), but higher costs associated with Facebook when specifically targeting populations traditionally under-represented in clinical research. Recruiting for an HIV prevention trial in young, urban women, Jones et al.7 found that Facebook had better reach in high-risk populations and cost less than traditional recruitment methods. However, women recruited by traditional methods were more likely to be randomized after screening than those recruited online.

The Menopausal Strategies: Finding Lasting Answers to Symptoms and Health (MsFLASH) Vaginal Health Trial was launched in 2016 to evaluate two interventions for postmenopausal vulvovaginal symptoms (itching, pain, irritation, dryness, pain with sex) in healthy midlife women.8 For this study we included a pilot study to evaluate the effectiveness of recruitment by social media as evidence for use in future trials, in addition to our usual mass mailing recruitment, with the specific objective of assessing the feasibility of Facebook advertising recruitment. The Vaginal HealthTrial was the MsFLASH Network’s fifth randomized, multi-center clinical trial in healthy menopausal women, with previous trials ranging in size from 100 to 355 women. The MsFLASH investigators were particularly interested in testing social media advertising for a trial focused on vulvovaginal symptoms due to known challenges of recruiting patients for studies where there is high level of sensitivity to privacy. Little guidance was available in the literature, since reports on recent, comparable trials testing interventions for postmenopausal vulvovaginal symptoms did not describe recruitment methods.9–11

Methods

Study design

A 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted among women with moderate-severe vulvovaginal symptoms recruited at two sites: University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, MN and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, WA. The trial enrolled 302 post-menopausal women aged 45-70 years from April 2016 to February 2017. Details of the trial design, methods, and primary results are published.8 In brief, women were asked to complete questionnaires and undergo a pelvic exam that included vaginal biospecimen collection at each of three study visits. In addition, participants were asked to complete vaginal symptom diaries and collect vaginal swabs daily for weeks 1, 4, and 12, plus once weekly all other study weeks, and mail in these swabs and diaries weekly. As incentives, participants were paid $25 upon completion of each study visit, $75 at study completion, and $50 for each biopsy (Seattle site only). Parking for study visits was reimbursed.

Recruitment methods

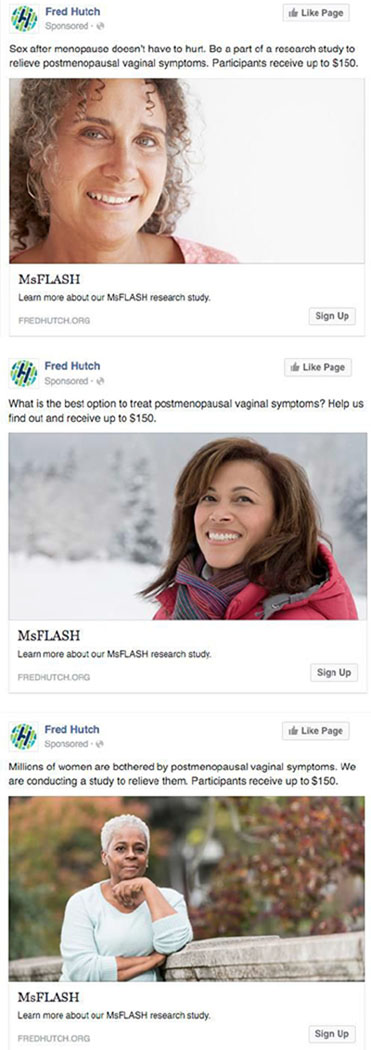

Two focus groups were conducted to engage Seattle-area women to provide input on recruitment material design and methodology. Twenty women identified through Kaiser Permanente Washington electronic health records as meeting the trial’s sex and age inclusion criteria, and who had a medical history of seeking care or using a treatment for postmenopausal vulvovaginal symptoms, were recruited for these focus groups. Using this stakeholder input, recruitment letters were developed to include a collage of images of women as well as wording that appealed to the focus group women. Facebook advertisement design was derived from the recruitment letter. The Communications & Marketing core of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (location of the MsFLASH Data Coordinating Center) supported many aspects of the recruitment, including graphic design of the letters and envelopes (Appendix 1 in the Supplemental Material), creation of a website dedicated to the trial, Facebook ad design (Figure 1), and management of the Facebook ad campaign.

Figure 1.

MsFLASH Vaginal Health Trial recruitment advertisements as posted on Facebook

The mailing recruitment was more successful than anticipated, thus there were limited participant slots to fill through Facebook recruitment. Online ads were posted for several days or weeks at a time as needed to maintain a steady flow of participants for screening calls and clinic visits to reach a maximum of 20 women at each site. Facebook ads were displayed in the “newsfeed” of targeted users. A Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center logo was included in the ads (Figure 1). Three different ads were posted. A box in the lower right-hand corner of the ad was labelled “Sign Up”; a click was defined as the user selecting this link to the study website and thereby leaving their Facebook page. The third of the three ads as shown in Figure 1 was eventually removed for a relative lack of response (i.e. clicks). The study website page displayed all the information contained in the 2-sided recruitment letter (Appendix 1 in the Supplemental Material), including study motivation and objectives, investigators, participant requirements, and eligibility criteria. A response was defined as providing contact information on the study web form. The estimated reach is defined as the estimated number of Facebook users whose newsfeed included the ad at least once.

The target populations for recruitment by mailings and recruitments by Facebook ads were similar, both including women in the relevant age range and living within 20 miles of the Minneapolis and Seattle city centers based on their zip code (mail) or stated city of residence plus device and connection information (Facebook). Online advertising followed our mailings; thus, it is likely that some women in these areas were exposed to both methods of recruitment. The Facebook advertising budget was capped at $15,000 and applied a link-click objective – that is, the company’s algorithms optimized ad placements among the target audience to maximize link clicks at the lowest cost, charging the campaign for each user click rather than ad display. For further understanding of the Facebook advertising user process, see the detailed description provided by Jones et al.7 For mailing, costs included purchase of mailing lists, printing of letters and envelopes, and bulk-rate postage. Staff time and indirect costs were not included in the calculations, since the Communications & Marketing staff managing the Facebook ad campaign provided their time at no cost while paid MsFLASH staff carried out the mailings.

Study enrollment procedures

Women provided their contact information via phone message or web form. Eligibility screening occurred through a series of phone and in-person contacts, beginning with a phone call to the potential participant. Once a woman responded, the study enrollment procedures did not vary by recruitment method.

Results

Facebook ads ran for 28 days in Minneapolis and 15 days in Seattle during September-December 2016. Our estimated reach exceeded 200,000 women; 8,930 women clicked on the study link, and 461 entered their name and phone number for a response rate per estimated reach of 0.22%. Of these 461 responses, 25 women (5.4%) were randomized: 10 in Minneapolis and 15 in Seattle. Costs were $32 per response and $593 per randomized participant.

The social media recruitment results varied by site: the Minneapolis ads were posted on nearly twice as many days, were seen by more than twice as many women, and generated twice as many clicks compared to those in Seattle. However, the two sites achieved approximately the same number of responses (Table 1). The response rates per estimated reach were 0.16% in Minneapolis and 0.37% in Seattle, and the costs of recruiting by Facebook were $1,177 versus $203 per woman randomized in Minneapolis and Seattle, respectively.

Table 1.

Facebook advertising recruitment statistics

| Minneapolis | Seattle | |

|---|---|---|

| Potential audience | 300,000 | 250,000 |

| Number of days ads posted | 28 | 15 |

| Date range | 9/27/16 – 12/9/16 | 10/19/16 – 12/9/16 |

| Estimated reacha | 148,479 | 60,032 |

| Clicksb | 6,104 | 2,826 |

| Responsesc received | 236 | 225 |

Estimated reach = estimated number of Facebook users shown the ad

Click = the user selected a link to the study website

Response = the user provided contact information on the study web form

Our primary recruitment campaign consisted of 277,000 letters sent during April-September 2016, from which we received 2,166 responses for a response rate of 0.78%. From these responses, we randomized 277 women (12.8%). The total mailing cost was $98,682, $46 per response and $356 per randomized participant. Results varied little across sites.

Conclusions

By recruiting 25 women to our Vaginal Health Trial via Facebook advertising, we showed that recruitment to a clinical trial for healthy midlife women with bothersome vulvovaginal symptoms can be accomplished through social media. Facebook advertising was particularly efficacious for generating prospective participants; this is known in marketing terms as lead generation. Another interesting finding was the observed variability of the method’s effectiveness between two cities.

The strengths of this pilot study include contributing to the relatively sparse literature on social media recruitment for clinical trials. Further, barriers to recruitment were presumably greater for this trial than for other healthy volunteer studies due to its subject requiring a high level of sensitivity to privacy and greater altruism from the participants in terms of number of visits, physically invasive biospecimen collections, and personal survey questions. Another asset was the use of two different geographical sites.

However, due to the opportunistic use of social media advertising after recruitment by mail was nearly complete, we cannot directly compare results by recruitment method. The limited scope of this pilot study also illuminated shortcomings. First, only one method of social media outreach was employed. Second, our approach did not include strategies such as alternating ad pictures and/or text that might have optimized ad performance, although we started with three pictures and dropped one that drew less interest. Third, the efficacy of our Facebook recruitment campaign may also have been confounded by seasonal timing in Minnesota, although data were too sparse to estimate differences between time periods, and better recognition of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center logo on Facebook ads in Seattle compared to Minneapolis. These factors may help explain the greater success of Facebook ads in Seattle. In addition, the generalizability of our findings is limited by the study population’s homogeneity – 88% of participants were White, 66% college graduates, and 85% married or partnered.8

In conclusion, recruitment via Facebook advertising to a randomized clinical trial to treat menopausal vulvovaginal symptoms is feasible, but a comparative study within a trial is needed to understand differences in efficacy and cost-effectiveness between social media and traditional methods for this population. Ideally, multiple recruitment campaigns should be introduced simultaneously to avoid any potential confounding of one method by another. In our study, it is possible that women’s responses to online advertisements were influenced by previous receipt of recruitment letters.

Increasing concerns about Facebook users’ privacy, especially considering recent revelations about leaks of users’ personal information that was mined for targeted election campaign advertising, are likely to change the social media landscape. However, a large proportion of Americans continue to use social media (69% of US adults in both November 2016 and January 2018) whether on Facebook or other platforms.12 As health researchers continue to take advantage of the benefits of social media for targeted advertising and recruitment, they will also need encourage and support policy makers to better address consumer privacy concerns. Our pilot study results suggest that social media advertising is a feasible approach to eliciting healthy midlife women’s interest and participation in clinical research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Jonathan Bricker, PhD, Nylkhalid Jungmayer, and Paula Sandler in this study.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging [grant number 5R01AG048209], with supplemental funding from the National Institutes of Health/Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02516202

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pew Research Center. Social Media Usage: 2005-2015, http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005-2015/ (2015, accessed 5 April 2018).

- 2.Shere M, Zhao XY and Koren G. The role of social media in recruiting for clinical trials in pregnancy. PLoS One 2014; 9: e92744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heffner JL, Wyszynski CM, Comstock, et al. Overcoming recruitment challenges of web-based interventions for tobacco use: the case of web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation. Addict Behav 2013; 38: 2473–2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckingham L, Becher J, Voytek CD, et al. Going social: Success in online recruitment of men who have sex with men for prevention HIV vaccine research. Vaccine 2017; 35: 3498–3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huesch MD, Mukherjee D and Saunders EF. E-recruitment into a bipolar disorder trial using Facebook tailored advertising. Clin Trials 2018; 15: 522–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juraschek SP, Plante TB, Charleston J, et al. Use of online recruitment strategies in a randomized trial of cancer survivors. Clin Trials 2018; 15: 130–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones R, Lacroix LJ and Porcher E. Facebook advertising to recruit young, urban women into an HIV prevention clinical trial. AIDS Behav 2017; 21: 3141–3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell CM, Reed SD, Diem S, et al. Treating postmenopausal vulvovaginal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of vaginal estradiol tablets, moisturizer and placebo. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178: 681–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause 2010; 17: 480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labrie F, Archer DF, Koltun W, et al. Efficacy of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on moderate to severe dyspareunia and vaginal dryness, symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy, and of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Menopause 2016; 23: 243–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause 2013; 20: 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pew Research Center. Social media fact sheet, http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/(2018, accessed 7 March 2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.