Abstract

Western societies notice an increasing interest in plant-based eating patterns such as vegetarian and vegan, yet potential effects on the body and brain are a matter of debate. Therefore, we systematically reviewed existing human interventional studies on putative effects of a plant-based diet on the metabolism and cognition, and what is known about the underlying mechanisms. Using the search terms “plant-based OR vegan OR vegetarian AND diet AND intervention” in PubMed filtered for clinical trials in humans retrieved 205 studies out of which 27, plus an additional search extending the selection to another five studies, were eligible for inclusion based on three independent ratings. We found robust evidence for short- to moderate-term beneficial effects of plant-based diets versus conventional diets (duration ≤ 24 months) on weight status, energy metabolism and systemic inflammation in healthy participants, obese and type-2 diabetes patients. Initial experimental studies proposed novel microbiome-related pathways, by which plant-based diets modulate the gut microbiome towards a favorable diversity of bacteria species, yet a functional “bottom up” signaling of plant-based diet-induced microbial changes remains highly speculative. In addition, little is known, based on interventional studies about cognitive effects linked to plant-based diets. Thus, a causal impact of plant-based diets on cognitive functions, mental and neurological health and respective underlying mechanisms has yet to be demonstrated. In sum, the increasing interest for plant-based diets raises the opportunity for developing novel preventive and therapeutic strategies against obesity, eating disorders and related comorbidities. Still, putative effects of plant-based diets on brain health and cognitive functions as well as the underlying mechanisms remain largely unexplored and new studies need to address these questions.

Subject terms: Molecular neuroscience, Psychiatric disorders, Genomics, Human behaviour

Introduction

Background

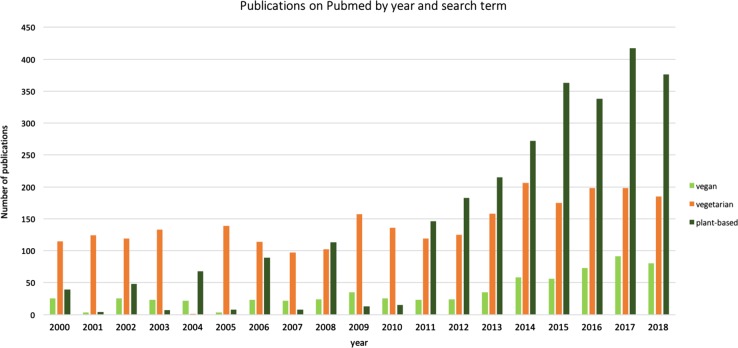

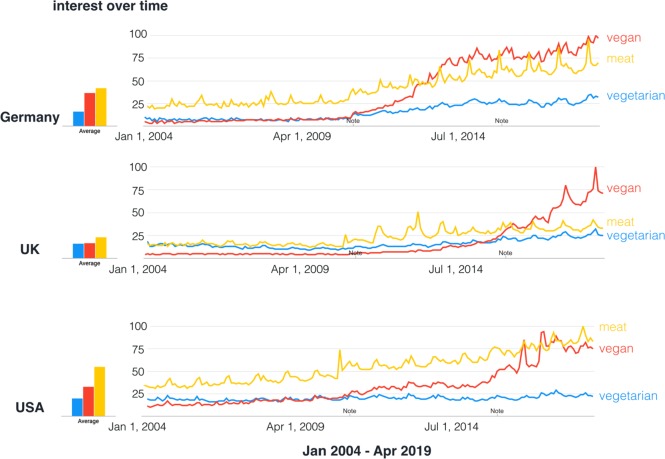

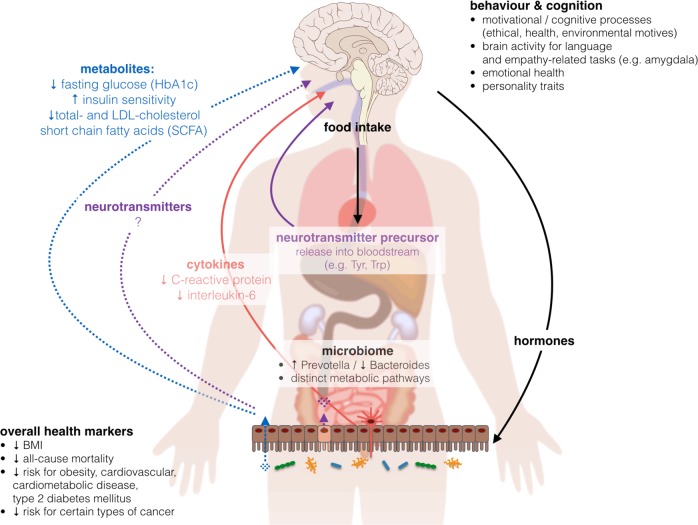

Western societies notice an increasing interest in plant-based eating patterns such as avoiding meat or fish or fully excluding animal products (vegetarian or vegan, see Fig. 1). In 2015, around 0.4−3.4% US adults, 1−2% British adults, and 5−10% of German adults were reported to eat largely plant-based diets1–4, due to various reasons (reviewed in ref. 5). Likewise, the number of scientific publications on PubMed (Fig. 2) and the public popularity as depicted by Google Trends (Fig. 3) underscore the increased interest in plant-based diets. This increasing awareness calls for a better scientific understanding of how plant-based diets affect human health, in particular with regard to potentially relevant effects on mental health and cognitive functions.

Fig. 1. The spectrum of diets including all or only certain types of animal-based products.

From left to right: including all food items (omnivore), including all except for meat (pesco-vegetarian) or meat and fish (ovo-lacto-vegetarian) to including only plant-based items (vegan)

Fig. 2.

Frequency of publications on PubMed including the search terms “vegan” (in light green), vegetarian (in orange) and plant-based (dark green)—accessed on 19 April 2019

Fig. 3. Google Trends Search for search term hits for “vegan”, “vegetarian” and “meat” in Germany (adapted to “vegetarisch”, “vegan” and “fleisch”), the USA and the UK from 2004 to present.

Note indicates technical improvements implemented by Google Trends. Data source: Google Trends. Search performed on 18 April 2019

Study aims

A potential effect of plant-based diets on mortality rate remains controversial: large epidemiological studies like the Adventist studies (n = 22,000−96,000) show a link between plant-based diets, lower all-cause mortality and cardiovascular diseases6,7, while other studies like the EPIC-Oxford study and the “45 and Up Study” (n = 64,000−267,000) show none8,9. Yet, many, but not all, epidemiological and interventional human studies in the last decades have suggested that plant-based diets exert beneficial health effects with regard to obesity-related metabolic dysfunction, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and chronic low-grade inflammation (e.g. refs. 6,7,10,11, for reviews, see refs. 12–18). However, while a putative link between such metabolic alterations and brain health through pathways which might include diet-related neurotransmitter precursors, inflammatory pathways and the gut microbiome19 becomes increasingly recognized, the notion that plant-based diets exert influence on mental health and cognitive functions appears less documented and controversial20–24. We therefore systematically reviewed the current evidence based on available controlled interventional trials, regarded as the gold standard to assess causality, on potential effects of plant-based diets on (a) metabolic factors including the microbiome and (b) neurological or psychiatric health and brain functions. In addition, we aimed to evaluate potential underlying mechanisms and related implications for cognition.

Methods

We performed a systematic PubMed search with the following search terms “plant-based OR vegan OR vegetarian AND diet AND intervention” with the filter “clinical trial” and “humans”, preregistered at PROSPERO (CRD42018111856; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=111856) (Suppl. Fig. 1). PubMed was used as search engine because it was esteemed to yield the majority of relevant human clinical trials from a medical perspective. Exclusion criteria were insufficient design quality (such as lack of a control group), interventions without a plant-based or vegetarian or vegan diet condition, intervention with multiple factors (such as exercise and diet), and the exclusive report of main outcomes of no interest, such as dietary compliance, nutrient intake (such as vitamins or fiber intake), or nonmetabolic (i.e., not concerning glucose metabolism, lipid profile, gastrointestinal hormones or inflammatory markers) or non-neurological/psychiatric disease outcomes (e.g. cancer, caries).

Studies were independently rated for eligibility into the systematic review by three authors based on reading the abstract and, if needed, methods or other parts of the publication. If opinions differed, a consensus was reached through discussion of the individual study. This yielded 27 eligible out of 205 publications; see Table 1 for details. To increase the search radius for studies dealing with microbial and neurological/psychiatric outcomes, we deleted the search term “intervention”, which increased the number of studies by around one third, and checked for studies with “microbiome/microbiota”, “mental”, “cognitive/cognition” or “psychological/psychology” in the resulting records. Through this, we retrieved another five studies included in Table 1. Further related studies were reviewed based on additional nonsystematic literature search.

Table 1.

Intervention studies on the effect of plant-based diets

| Author Year | Study design | n patients | n healthy | Nature of intervention, and if calorie-restricted | Duration of intervention | Measures | Effect of intervention | Favoring vegan diet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss, blood-based metabolic markers | ||||||||

| Turner-McGrievy et al. (2007)139 | RCT; overweight postmenopausal women: low-fat vegan vs. National Cholesterol Education Program diet two replications | 62; first run 28 (14 vs. 14), second run 34 (17 vs. 17) |

Low-fat vegan diet (unrestricted): − fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains − animal products proscribed − limit high-fat plant foods vs. National Cholesterol Education Program diet (unrestricted): − see guidelines |

14 weeks (24 months follow-up) | Body weight | − weight loss higher in vegan group at year 1 and year 2 | + | |

| Burke et al. (2008)140 | RCT; obese subjects; four groups: freely chosen vegetarian vs. freely chosen conventional vs. assigned vegetarian vs. assigned conventional | 178 (48 vs. 35 vs. 48 vs. 45) |

Vegetarian (restricted): − no meat, poultry, fish vs. Standard behavioral therapy, group sessions led by dietician/physiologist/nurse/behavioral scientist − monitoring of physical activity and calorie/fat content of foods − cooking magazines provided |

18 months | Body weight |

− weight loss higher in both groups that were assigned to a certain diet − trend to higher weight loss in both vegetarian groups − all groups showed significant weight loss |

+ | |

| Barnard et al. (2009)141 |

RCT; T2DM patients; two groups: Vegan vs. conventional restrictive diet |

99 (49 vs. 50) |

Vegan (unrestricted): − 10% fat, 15% protein, 75% carbohydrates − daily cholesterol intake < 50 mg − vegetables, fruit, grains, legumes − no animal products, fatty foods and high-glycaemic index foods vs. Conventional: −<7% fat, 15−20% protein, 60−70% carbohydrates − meal plan with dietician, 3-day dietary record |

74 weeks | Body weight, blood measures |

− significant weight loss in both groups (trend towards stronger effect in vegan group) − lower HbA1C, total-/LDL-/ and non-HDL-cholesterol after intervention in both groups, trend towards lower HbA1C in vegan group − controlling for medication changes led to significantly greater reductions in HbA1C, total- and LDL-cholesterol in vegan group |

+ | |

| Elkan et al. (2008)40 | Rheumatoid arthritis patients | 66 (38 vs. 28) |

Gluten-free vegan diet (protein energy level was 10% of the total energy intake, the carbohydrates 60%, and fat 30%; contained vegetables, root vegetables, nuts, fruits) vs. well-balanced non-vegan (contained 10 to 15% protein, 55 to 60% carbohydrate, no more than 30% fat) |

12 months | Body weight, blood measures | − lower BMI, LDL, TC and higher anti-PC IgM in the vegan diet group | + | |

| Marniemi et al. (1990)142 | Moderately obese subjects | 110 in total (31 vs. 37 vs. 42) |

Lactoovo (1200 kcal/day) vs. mixed diet (1200 kcal/day) vs. control (no intervention) |

12 months | Body weight, blood measures | − Weight-reduction, improved lipid metabolism in both intervention groups, stronger effects in mixed diet compared to lactovegetarian diet | − | |

| Acharya et al. (2013)143 | Pilot study for RCT; overweight and obese subject | 143 in total (79 vs. 64) | Standard calorie- and fat-restricted diet vs. calorie- and fat-restricted lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet | 6 months | Body weight | − no significant effect on weight dependent on diet | o | |

| Wright et al. (2017)144 |

RCT; mid-age to old T2DM and overweight patients; whole food plant-based unrestricted vs. usual care |

65 (32 vs. 33) |

Low-fat plant-based: − 7−15% fat − whole grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits − calorie-unrestricted − avoid animal products and refined oils, high-fat plant foods, sugar, salt, caffeine − 50 μg/day vitamin B12 |

6 months | Body weight, blood measures | − reduced BMI and mean cholesterol in plant-based group | + | |

| Jenkins et al. (2014)29 | RCT; overweight hyperlipidemic patients; low-carb vegan vs. high-carb lacto-ovo | 39 (19 vs. 20) |

− caloric restriction to 60% of estimated caloric requirements low-carb vegan: − 26% carbohydrates, 31% plant protein, 43% fat vs. high-carb lacto-ovo-vegetarian: − 58% carbohydrates, 16% protein, 25% fat |

6 months | Body weight, blood measures |

− higher weight loss and lower LDL and TG for low-carb vegan group after 1 month31: − weight loss reduced in both groups (about 4.0 kg) (n.s. difference across groups) − more reduced LDL, TC, apolipoproteins for plant-based group |

+ | |

| Turner-McGrievy et al. (2015)33,161 | RCT; healthy overweight subjects 25-49.9 kg/m2; calorie-unrestricted | 50 (12 vs. 13 vs. 13 vs. 12) |

− avoid fast foods and processed foods; self-based diets − all groups received weekly dietary sessions except for the omnivore group (kept following their usual diet) vegan: − no animal products, focus on plant-based foods vs. vegetarian: − no meat, fish, poultry, but eggs and dairy vs. pesco-vegetarian: − no meat, poultry, but fish, shellfish, eggs, dairy vs. semi-vegetarian: − all foods, red meat limited to 1/week and poultry limited to <5/week |

6 months | Body weight, blood measures | − higher weight loss in vegan group (particularly decreased fat and saturated fat) | + | |

| Turner-McGrievy et al. (2014)145 |

RCT; overweight subjects with polycystic syndrome: vegan vs. low-calorie diet |

18 (9 vs. 9) |

Vegan: − exclude all animal products, limit high glycaemic-index foods vs. Low-calorie: − restricted to 1200−1500 kcal/day depending on body weight − assessed by weekly 24 h recall |

6 months | Body weight, polycystic syndrome |

− higher weight loss at 3 months for vegan group (not after 6 months) − lower energy intake after 6 months for vegan group (lower fat, lower protein) − no changes for polycystic syndrome |

+/o | |

| Kahleova et al. (2011)146 |

RCT; T2DM patients; two groups: vegetarian vs. conventional diabetic diet |

74 (37 vs. 37) |

Vegetarian (restricted) vs. Conventional (restricted) − all meals provided − after 12 weeks physical exercise added |

6 months |

Body weight, polycystic syndrome |

− reduced medication, higher weight loss, increased insulin sensitivity, reduced visceral and subcutaneous fat, increase in plasma adiponectin, decrease in leptin in the vegan group | + | |

| Ferdowsian et al. (2010)147 | RCT; overweight and/or T2DM patients: low-fat vegan diet vs. control; onsite | 113 |

Low-fat vegan: − no meat, poultry, fish, dairy, eggs, <5% saturated fat, <25% total fat, < 50 mg cholesterol daily − multivitamin supplement (incl. B12) vs. control: − usual diet |

5,5 months | Body weight | − reduced body weight and waist circumference in intervention group | + | |

| Mishra et al. (2013) (same sample as Agarwal et al. (2015) and partly overlapping with Ferdowsian et al. (2010))147–149 | RCT; overweight and/or T2DM patients; multicomponent worksite intervention; low-fat vegan vs. usual diet | 291 at 4 sites; (142 vs. 149) |

low-fat vegan (unrestricted): − avoid all animal products, minimize added oils, favor whole grains − vitamin B12 and multivitamin supplements vs. Control: − usual diet; no instruction |

18 weeks | Blood measures | − lower total cholesterol in vegan group | + | |

| Kahleova et al. (2018)150 | RCT; T2DM patients | 74 (37 vs. 37) |

vegetarian diet (−500 kcal/day) vs. control isocaloric conventional anti-diabetic diet (−500 kcal/day) |

16 weeks | Anthropo-metric measures | − greater reduction in total leg area for thigh adipose tissue distribution after vegetarian diet | + | |

| Lee et al. (2016)28 |

RCT; healthy Korean subjects; two groups: Vegan vs. conventional restrictive diet |

106 (46 vs. 47) |

Vegan (unrestricted): (1) ingest unpolished rice (brown rice); (2) avoid polished rice (white rice); (3) avoid processed food made of rice flour or wheat flour; (4) avoid all animal food products (i.e., meat, poultry, fish, daily goods, and eggs); and (5) favor low-glycemic index foods (e.g., legumes, legumes-based foods, green vegetables, and seaweed) vs. Conventional (restricted) (1) restrict their individualized daily energy intake based on body weight, physical activity, need for weight control, and compliance; (2) total calorie intake comprised 50–60% carbohydrate, 15–20% protein (if renal function is normal), <25% fat, <7% saturated fat, minimal trans-fat intake, and ≤200 mg/day cholesterol |

12 weeks | Body weight, blood measures | − significantly larger reduction of HbA1C levels, trends towards lower BMI and lower waist circumference in the vegan intervention group | + | |

| Barnard et al. (2000)151 | RCT; premenopausal women | 51 (35) |

low-fat vegetarian (10% fat) vs. normal diet incl. a placebo pill |

3 months | Blood measures | − decreased LDL, HDL, TC after 10% fat-vegetarian diet | + | |

| Rauma et al.39 | Rheumatoid arthritis patients | 43 (22 vs. 21) | vegan vs. control (usual diet) | 3 months | Body weight, urine measures | − 9% reduction of body weight in the vegan group | + | |

| Gardner et al. (2005)152 | RCT; hypercholesterolemic outpatients 30−65 years | 120 (59 vs. 61) |

low-fat diet (incl. animal products) vs. low-fat plus diet (more veggie, legumes, whole grains) |

1 month | Blood measures | − lower TC, LDL for low-fat plus (plant-based) diet | + | |

| Macknin et al. (2015)153 | Randomized; obese hypercholesterolemic children and their parents | 30 (16 vs. 14) |

plant-based no added fat diet (PB) vs. American Heart Association Diet (AHA) |

1 month | Body weight, blood measures |

− lower BMI and hsCRP levels as well as higher waist circumference in the plant-based and no-added fat diet condition in children, − lower cholesterol, LDL and HbA1c in the plant-based and no-added fat diet condition in parents |

+/o | |

| Sciarrone et al. (1993)154 | Parallel randomized trial, healthy men | 20 (10 vs. 10) |

lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet vs. omnivorous diet − initial 2 weeks under caloric restriction, afterwards unrestricted |

6 weeks | Body weight, blood measures | − no significant differences in body weight, glucose, insulin or catecholamines between groups | o | |

| Alleman et al. (2013)155 | Interventional study, healthy subjects | 29 (16 vs. 13) |

traditional (vegan) vs. modified Daniel Fast diet (incl. daily meat and dairy) |

3 weeks | Body weight, blood measures |

− no significant weight changes after dietary intervention for neither condition − both diets show improvement of blood lipids, inflammation markers |

o | |

| Neacsu et al. (2014)156 | Within-subject cross-over design; obese men | 20 in total |

meat-based high-protein diet vs. vegetarian soy high-protein diet (both diets: 30% protein, 30% fat, 40% carbohydrate) |

2 weeks | Body weight, blood measures | − n. s. differences between weight loss and gut hormone profile | o | |

| Koebnick et al. (2004)157 | RCT; healthy subjects; site-based study | 32 in total |

low-fat plant-based (20% fat) vs. control |

1 week | Blood measures | − reduced TC, LDL, TG in vegan diet | + | |

| Microbiome | ||||||||

| David et al. (2014)35 | Within-subject cross-over design, healthy, young volunteers | 10 |

exclusively plant-based diet (unrestricted) vs. nearly exclusively animal-based diet (unrestricted) |

5 days | 16S rRNA gene sequencing (stool samples) |

Higher abundance of bile-tolerant microorganisms (Alistipes, Bilophila, Bacteroides) and decreased levels of Firmicutes (Roseburia, Eubacterium rectale, Ruminococcus bromii). |

? | |

| Neurological/psychiatric disease outcomes and brain functions | ||||||||

| Karlsson et al. (1994)41 | RCT; moderately obese women | 60 |

1300 kcal lacto-vegetarian diet vs. 1300 kcal conventional weight-reducing diet |

3, 8, 24 months | Psychological measures incl. mental well-being, functional status; body weight | − no significant differences between groups on psychological measures and BMI | o | |

| Kjeldsen-Kragh et al. (1994)158 | RCT; rheumatoid arthritis patients, vegetarian vs. omnivorous diet | 53 (27 vs. 26) |

− vegetarian diet (fasting 7−10 days, gluten free vegan diets for 3.5 months, afterwards lacto-vegetarian diet vs. - normal omnivorous diet |

13 months | General Health Questionnaire | − improvements in psychological distress including depression and anxiety subscores in the vegetarian group | + | |

| Yadav et al. (2016)38 | RCT; multiple sclerosis patients | 61 (32 vs. 29) |

very low-fat plant-based diet: − starchy plant foods, 10% fat, 14% protein, 76% carbohydrates (no meat, fish, eggs, dairy products or vegetable oils) vs. control: − usual diet − assessed by FFQ and meetings with dietician |

12 months |

Brain MRI, fatigue, body weight, blood sample |

− no clear effect on brain MRI outcomes; improvement of fatigue, weight status and metabolic markers in the vegan group | o/+ | |

| Bunner et al. (2014)159 |

RCT; cross-over trial migraine patients; Low-fat vegan vs. placebo |

42 in total |

Vegan diet: Favored intake of whole grains, lentils, certain vegetables; avoidance of all animal products, nuts and seeds, alcohol, coffee vs. Placebo: 10 mcg alpha-linolenic acid and 10 mcg vitamin E/day |

9 months | Headache pain measured with The Patient’s Global Impression of Change | − improvement of migraine during last 2 weeks in the vegan group | + | |

| Kahleova et al. (2013)160 | Randomized, open, parallel design, T2DM patients, vegetarian vs. control group | 74 (37 vs. 37) |

vegetarian diet (−500 kcal/day) vs. control isocaloric conventional anti-diabetic diet (−500 kcal/day) |

24 weeks | Quality of life, depressive symptoms, eating behavior | − improved quality of life, dietary restraint and disinhibition and lower depression scores in the vegetarian group | + | |

| Agarwal et al. (2015)23 | RCT; overweight and/or T2DM patients; multicomponent worksite intervention; low-fat vegan vs. usual diet | 291 at 4 sites; (142 vs. 149) |

low-fat vegan (unrestricted): − avoid all animal products, minimize added oils, favor whole grains − vitamin B12 and multivitamin supplements vs. Control: − usual diet; no instruction |

18 weeks | Depression, anxiety, fatigue, emotional well-being | − all measures significantly improved in the vegan group | + | |

| Kaartinen et al. (2000)37 | Non-randomized; fibromyalgia patients | 32 (18 vs. 15) |

low-salt, raw vegan diet vs. omnivorous diet |

3 months | Disease improvement, urine and blood measures | − less pain, improved joint stiffness and quality of sleep, decreased weight, TC, and urine sodium in the vegan diet group | + | |

| Beezhold et al. (2012)42 | Healthy subjects; omnivorous | 39 (in locks at 3, i.e. 13 in each group) |

control group consuming meat, fish, and poultry daily (OMN) vs. a group consuming fish 3−4 times weekly but avoiding meat and poultry (FISH) vs. a vegetarian group avoiding meat, fish, and poultry (VEG) |

2 weeks | Stress, depression, mood, anxiety, blood levels |

− decrease in stress, anxiety and improved mood in vegan group − decreased fatty acids, increased n−6 to n−3 ratio and decrease in alpha-linoleic acid in the VEG compared to OMN group |

+ | |

Section I: Effects of plant-based diets on body and brain outcomes

Results based on interventional studies on metabolism, microbiota and brain function

Overall, the vast majority of studies included in this systematic review reported a short-term beneficial effect of plant-based dietary interventions (study duration 3−24 months) on weight status, glucose, insulin and/or plasma lipids and inflammatory markers, whereas studies investigating whether plant-based diets affect microbial or neurological/psychiatric disease status and other brain functions were scarce and rather inconclusive (Table 1).

More specifically, 19 out of 32 studies dealing with T2DM and/or obese subjects and seven out of 32 dealing with healthy subjects observed a more pronounced weight loss and metabolic improvements, such as lowering of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)—a long-term marker for glucose levels—decreased serum levels of low-density (LDL) and high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and total cholesterol (TC), after a plant-based diet compared to an omnivore diet. This is largely in line with recent meta-analyses indicating beneficial metabolic changes after a plant-based diet25–27.

For example, Lee et al. found a significantly larger reduction of HbA1c and lower waist circumference after vegan compared to conventional dieting28. Jenkins et al. found a disease-attenuating effect in hyperlipidemic patients after 6 months adopting a low-carbohydrate plant-based diet compared to a high-carbohydrate lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet29,30. However, lower energy intake in the vegan dieters might have contributed to these effects. Yet, while a plant-based diet per se might lead to lower caloric intake, other studies observed nonsignificant trends toward higher effect sizes on metabolic parameters after a vegan diet, even when caloric intake was comparable: two studies in T2DM patients31,32 compared calorie-unrestricted vegan or vegetarian to calorie-restricted conventional diets over periods of 6 months and 1.5 years, respectively, in moderate sample sizes (n ~ 75−99) with similar caloric intake achieved in both diet groups. Both studies indicated stronger effects of plant-based diets on disease status, such as reduced medication, improved weight status and increased glucose/insulin sensitivity, proposing a diabetes-preventive potential of plant-based diets. Further, a five-arm study comparing four types of plant-based diets (vegan, vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian, semi-vegetarian) to an omnivore diet (total n = 63) in obese participants found the most pronounced effect on weight loss for a vegan diet (−7.5 ± 4.5% of total body weight)33. Here, inflammation markers conceptualized as the dietary inflammatory index were also found to be lower in vegan, vegetarian and pesco-vegetarian compared to semi-vegetarian overweight to obese dieters33.

Intriguingly, these results28–33 cohesively suggest that although caloric intake was similar across groups, participants who had followed a vegan diet showed higher weight loss and improved metabolic status.

As a limitation, all of the reviewed intervention studies were carried out in moderate sample sizes and over a period of less than 2 years, disregarding that long-term success of dietary interventions stabilizes after 2−5 years only34. Future studies with larger sample sizes and tight control of dietary intake need to confirm these results.

Through our systematic review we retrieved only one study that added the gut microbiome as novel outcome for clinical trials investigating the effects of animal-based diets compared to plant-based diets. While the sample size was relatively low (n = 10, cross-over within subject design), it showed that changing animal- to plant based diet changed gut microbial activity towards a trade-off between carbohydrate and protein fermentation processes within only 5 days35. This is in line with another controlled-feeding study where microbial composition changes already occurred 24 h after changing diet (not exclusively plant-based)36. However, future studies incorporating larger sample sizes and a uniform analysis approach of microbial features need to further confirm the hypothesis that a plant-based diet ameliorates microbial diversity and health-related bacteria species.

Considering neurological or psychiatric diseases and brain functions, the systematic review yielded in six clinical trials of diverse clinical groups, i.e. migraine, multiple sclerosis, fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis. Here, mild to moderate improvement, e.g. measured by antibody levels, symptom improvement or pain frequency, was reported in five out of six studies, sometimes accompanied by weight loss37–40 (Table 1). However, given the pilot character of these studies, indicated by small sample sizes (n = 32−66), lack of randomization37, or that the plant-based diet was additionally free of gluten40, the evidence is largely anecdotal. One study in moderately obese women showed no effects on psychological outcomes41, two studies with obese and nonobese healthy adults indicated improvements in anxiety, stress and depressive symptom scores23,24. Taken together, the current evidence based on interventional trials regarding improvements of cognitive and emotional markers and in disease treatment for central nervous system disorders such as multiple sclerosis or fibromyalgia remains considerably fragmentary for plant-based diets.

Among observational studies, a recent large cross-sectional study showed a higher occurrence of depressive symptoms for vegetarian dieters compared to nonvegetarians20. Conversely, another observational study with a sample of about 80% women found a beneficial association between a vegan diet and mood disturbance24.

Overall, the relationship between mental health (i.e. depression) and restrictive eating patterns has been the focus of recent research20–22,24,42; however, causal relationships remain uninvestigated due to the observational design.

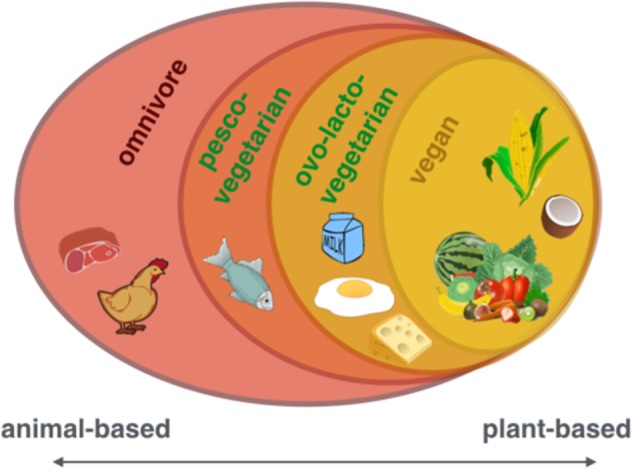

Underlying mechanisms linking macronutrient intake to metabolic processes

On the one hand, nutrient sources as well as their intake ratios considerably differ between plant-based and omnivore diets (Suppl. Table 1), and on the other hand, dietary micro- and macromolecules as well as their metabolic substrates affect a diversity of physiological functions, pointing to complex interdependencies. Thus, it seems difficult to nail down the proposed beneficial effects of a plant-based diet on metabolic status to one specific component or characteristic, and it seems unlikely that the usually low amount of calories in plant-based diets could explain all observed effects. Rather, plant-based diets might act through multiple pathways, including better glycemic control43, lower inflammatory activity44 and altered neurotransmitter metabolism via dietary intake45 or intestinal activity46 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. The effects of a plant-based diet on the microbiome−gut−brain axis including the here reviewed effects on overall health, microbial composition and activity, behavior and cognition.

BMI body-mass-index, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, LDL-cholesterol low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Trp tryptophan, Tyr tyrosine. Images from commons.wikimedia.org, “Brain human sagittal section” by Lynch 2006 and “Complete GI tract” by Häggström 2008, “Anatomy Figure Vector Clipart” by http://moziru.com

On the macronutrient level, plant-based diets feature different types of fatty acids (mono- and poly-unsaturated versus saturated and trans) and sugars (complex and unrefined versus simple and refined), which might both be important players for mediating beneficial health effects18. On the micronutrient level, the EPIC-Oxford study provided the largest sample of vegan dieters worldwide (n(vegan) = 2396, n(total) = 65,429) and showed on the one hand lower intake of saturated fatty acids (SFA), retinol, vitamin B12 and D, calcium, zinc and protein, and on the other hand higher intake of fiber, magnesium, iron, folic acid, vitamin B1, C and E in vegan compared to omnivore dieters47. Other studies confirmed the variance of nutrient intake across dietary groups, i.e. omnivores, vegetarians and vegans, showing the occurrence of critical nutrients for each group48,49. Not only the amount of SFA but also its source and profile might be important factors regulating metabolic control (reviewed in ref. 14), for example through contributing to systemic hyperlipidemia and subsequent cardiovascular risk. Recently, it has been shown in a 4-week intervention trial that short-term dietary changes favoring a diet high in animal-based protein may lead to an increased risk for cardiovascular derangements mediated by higher levels of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), which is a metabolite of gut bacteria-driven metabolic pathways50.

Secondly, high fiber intake from legumes, grains, vegetables and fruits is a prominent feature of plant-based diets (Table 1), which could induce beneficial metabolic processes like upregulated carbohydrate fermentation and downregulated protein fermentation35, improved gut hormonal-driven appetite regulation51–55, and might prevent chronic diseases such as obesity and T2DM by slowing down digestion and improving lipid control56. A comprehensive review including evidence from 185 prospective studies and 58 clinical trials concluded that risk reduction for a myriad of diseases (incl. CVD, T2DM, stroke incidence) was greatest for daily fiber intake between 25 and 29 g57. Precise evidence for underlying mechanisms is missing; however, more recently it has been suggested that high fiber intake induces changes on the microbial level leading to lower long-term weight gain58, a mechanism discussed below.

The reason for lower systemic inflammation in plant-based dieters could be due to the abundance of antiinflammatory molecule intake and/or avoidance of proinflammatory animal-derived molecules. Assessing systemic inflammation is particularly relevant for medical conditions such as obesity, where it has been proposed to increase the risk for cardiovascular disease59,60. In addition, higher C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels have been linked with measures of brain microstructure, such as microstructural integrity and white matter lesions61–63 and higher risk of dementia64, and recent studies point out that a diet-related low inflammatory index might also directly affect healthy brain ageing65,66.

Interventional studies that focus on plant- versus meat-based proteins or micronutrients and potential effects on the body and brain are lacking. A meta-analysis including seven RCTs and one cross-sectional studies on physical performance and dietary habits concluded that a vegetarian diet did not adversely influence physical performance compared to an omnivore diet67. An epidemiological study by Song et al.11 estimated that statistically replacing 3% of animal protein, especially from red meat or eggs, with plant protein would significantly improve mortality rates. This beneficial effect might however not be explained by the protein source itself, but possibly by detrimental components found in meat (e.g. heme-iron or nitrosamines, antibiotics, see below).

Some studies further hypothesized that health benefits observed in a plant-based diet stem from higher levels of fruits and vegetables providing phytochemicals or vitamin C that might boost immune function and eventually prevent certain types of cancer68–70. A meta-analysis on the effect of phytochemical intake concluded a beneficial effect on CVD, cancer, overweight, body composition, glucose tolerance, digestion and mental health71. Looking further on the impact of micronutrients and single dietary compounds, there is room for speculation that molecules, that are commonly avoided in plant-based diets, might affect metabolic status and overall health, such as opioid-peptides derived from casein72, pre- and probiotics73,74, carry-over antibiotics found in animal products75,76 or food-related carcinogenic toxins, such as dioxin found in eggs or nitrosamines found in red and processed meat77,78. Although conclusive evidence is missing, these findings propose indirect beneficial effects on health deriving from plant-based compared to animal-based foods, with a potential role for nonprotein substances in mediating those effects18. While data regarding chemical contaminant levels (such as crop pesticides, herbicides or heavy metals) in different food items are fragmentary only, certain potentially harmful compounds may be more (or less) frequently consumed in plant-based diets compared to more animal-based diets79. Whether these differences lead to systematic health effects need to be explored.

Taken together, the reviewed studies indicating effects of plant-based diets through macro- and micronutrient intake reveal both the potential of single ingredients or food groups (low SFA, high fiber) and the immense complexity of diet-related mechanisms for metabolic health. As proposed by several authors, benefits on health related to diet can probably not be viewed in isolation for the intake (or nonintake) of specific foods, but rather by additive or even synergistic effects between them (reviewed in refs. 12,80). Even if it remains a challenging task to design long-term RCTs that control macro- and micronutrient levels across dietary intervention groups, technological advancements such as more fine-tuned diagnostic measurements and automated self-monitoring tools, e.g. automatic food recognition systems81 and urine-related measures of dietary intake82, could help to push the field forward.

Nutrients of particular interest in plant-based diets

As described above, plant-based diets have been shown to convey nutritional benefits48,49, in particular increased fiber, beta carotene, vitamin K and C, folate, magnesium, and potassium intake and an improved dietary health index83. However, a major criticism of plant-based diets is the risk of nutrient deficiencies for specific micronutrients, especially vitamin B12, a mainly animal-derived nutrient, which is missing entirely in vegan diets unless supplemented or provided in B12-fortified products, and which seems detrimental for neurological and cognitive health when intake is low. In the EPIC-Oxford study about 50% of the vegan dieters showed serum levels indicating vitamin B12 deficiency84. Along other risk factors such as age85, diet, and plant-based diets in particular, seem to be the main risk factor for vitamin B12 deficiency (reviewed in ref. 86), and therefore supplementing vitamin B12 for these risk groups is highly recommended87. Vitamin B12 is a crucial component involved in early brain development, in maintaining normal central nervous system function88 and suggested to be neuroprotective, particularly for memory performance and hippocampal microstructure89. One hypothesis is that high levels of homocysteine, that is associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, might be harmful to the body. Vitamin B12 is the essential cofactor required for the conversion of homocysteine into nonharmful components and serves as a cofactor in different enzymatic reactions. A person suffering from vitamin B12 insufficiency accumulates homocysteine, lastly promoting the formation of plaques in arteries and thereby increasing atherothrombotic risk90, possibly facilitating symptoms in patients of Alzheimer’s disease91. A meta-analysis found that vitamin B12 deficiency was associated with stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Parkinson’s disease and in even lower concentrations with cognitive impairment92, supporting the claim of its high potential for disease prevention when avoided or treated93. Further investigations and longitudinal studies are needed, possibly measuring holotranscobalamin (the active form of vitamin B12) as a more specific and sensitive marker for vitamin B12 status94, to examine in how far nonsupplementing vegan dieters could be at risk for cardiovascular and cognitive impairment.

Similar health dangers can stem from iron deficiency, another commonly assumed risk for plant-based dieters and other risk groups such as young women. A meta-analysis on 24 studies proposes that although serum ferritin levels were lower in vegetarians on average, it is recommended to sustain an optimal ferritin level (neither too low nor too high), calling for well-monitored supplementation strategies95. Iron deficiency is not only dependent on iron intake as such but also on complimentary dietary factors influencing its bioavailability (discussed in ref. 95). The picture remains complex: on the one hand iron deficiency may lead to detrimental health effects, such as impairments in early brain development and cognitive functions in adults and in children carried by iron-deficient mothers96 and a possible role for iron overload in the brain on cognitive impairment on the other hand97. One study showed that attention, memory and learning were impaired in iron-deficient compared to iron-sufficient women, which could be restored after a 4-month oral iron supplementation (n = 118)98. Iron deficiency-related impairments could be attributed to anemia as an underlying cause, possibly leading to fatigue, or an undersupply of blood to the brain or alterations in neurobiological and neuronal systems99 provoking impaired cognitive functioning.

This leads to the general recommendation to monitor health status by frequent blood tests, to consult a dietician to live healthily on a plant-based diet and to consider supplements to avoid nutrient deficiencies or nutrient-overdose-related toxicity. All in all, organizations such as the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics100 and the German Nutrition Society do not judge iron as a major risk factor for plant-based dieters101.

Section II: Effects of diet on the gut microbiome

The link between diet and microbial diversity

Another putative mechanistic pathway of how plant-based diets can affect health may involve the gut microbiome which has increasingly received scientific and popular interest, lastly not only through initiatives such as the Human Microbiome Project102. A common measure for characterizing the gut community is enterotyping, which is a way to stratify individuals according to their gut bacterial diversity, by calculating the ratio between bacterial genera, such as Prevotella and Bacteroides103. While interventional controlled trials are still scarce, this ratio has been shown to be conclusive for differentiating plant-based from animal-based microbial profiles36. Specifically, in a sample of 98 individuals, Wu et al.36 found that a diet high in protein and animal fats was related to more Bacteroides, whereas a diet high in carbohydrates, representing a plant-based one, was associated with more Prevotella. Moreover, the authors showed that a change in diet to high-fat/low-fiber or to low-fat/high-fiber in ten individuals elicited a change in gut microbial enterotype with a time delay of 24 h only and remained stable over 10 days, however not being able to switch completely to another enterotype36. Another strictly controlled 30-day cross-over interventional study showed that a change in diet to either an exclusively animal-based or plant-based diet promoted gut microbiota diversity and genetic expression to change within 5 days35. Particularly, in response to adopting an animal-based diet, microbial diversity increased rapidly, even overshadowing individual microbial gene expression. Beyond large shifts in overall diet, already modest dietary modifications such as the daily consumption of 43 g of walnuts, were able to promote probiotic- and butyric acid-producing bacterial species in two RCTs, after 3 and 8 weeks respectively104,105, highlighting the high adaptability of the gut microbiome to dietary components. The Prevotella to Bacteroides ratio (P/B) has been shown to be involved in the success of dietary interventions targeting weight loss, with larger weight loss in high P/B compared to low P/B in a 6-month whole-grain diet compared to a conventional diet106. Only recently, other microbial communities, such as the salivary microbiome, have been shown to be different between omnivores and vegan dieters107, opening new avenues for research on adaptable mechanisms related to dietary intake.

A continuum in microbial diversity dependent on diet

Plant-based diets are supposed to be linked to a specific microbial profile, with a vegan profile being most different from an omnivore, but not always different from a vegetarian profile (reviewed in ref. 15). Some specifically vegan gut microbial characteristics have also been found in a small sample of six obese subjects after 1 month following a vegetarian diet, namely less pathobionts, more protective bacterial species improving lipid metabolism and a reduced level of intestinal inflammation108. Investigating long-term dietary patterns a study found a dose-dependent effect for altered gut microbiota in vegetarians and vegans compared to omnivores depending on the quantity of animal products109. The authors showed that gut microbial profiles of plant-based diets feature the same total number but lower counts of Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, E. coli and Enterobacteriaceae compared to omnivores, with the biggest difference to vegans. Still today it remains unclear, what this shift in bacterial composition means in functional terms, prompting the field to develop more functional analyses.

In a 30-day intervention study, David et al. found that fermentation processes linked to fat and carbohydrate decomposition were related to the abundance of certain microbial species35. They found a strong correlation between fiber intake and Prevotella abundance in the microbial gut. More recently, Prevotella has been associated with plant-based diets110 that are comparable to low-fat/high-fiber diets111 and might be linked to the increased synthesis of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA)112. SCFAs are discussed as putative signaling molecules between the gut microbiome and the receptors, i.e. free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFA2)51, found in host cells across different tissues113 and could therefore be one potential mechanism of microbiome−host communication.

The underlying mechanisms of nutrient decomposition by Prevotella and whether abundant Prevotella populations in the gut are beneficial for overall health remain unknown. Yet it seems possible that an increased fiber intake and therefore higher Prevotella abundance such as associated with plant-based diets is beneficial for regulating glycemic control and keeping inflammatory processes within normal levels, possibly due to reduced appetite and lower energy intake mediated by a higher fiber content114. Moreover, it has been brought forward that the microbiome might influence bodily homeostatic control, suggesting a role for the gut microbiota in whole-body control mechanisms on the systemic level. Novel strategies aim to develop gut-microbiota-based therapies to improve bodily states, e.g. glycemic control115, based on inducing microbial changes and thereby eliciting higher-level changes in homeostasis. While highly speculative, such strategies could in theory also exert changes on the brain level, which will be discussed next in the light of a bi-directional feedback between the gut and the brain.

Effects on cognition and behavior linking diet and cognition via the microbiome−gut−brain axis

While the number of interventional studies focusing on cognitive and mental health outcomes after adopting plant-based diets overall is very limited (see Section I above), one underlying mechanism of how plant-based diets may affect mood could involve signaling pathways on the microbiome−gut−brain axis116–119. A recent 4-week intervention RCT showed that probiotic administration compared to placebo and no intervention modulated brain activity during emotional decision-making and emotional recognition tasks117. In chronic depression it has been proposed that immunoglobulin A and M antibodies are synthesized by the host in response to gut commensals and are linked to depressive symptoms120. Whether the identified gram-negative bacteria might also play a role in plant-based diets remains to be explored. A meta-analysis on five studies concluded that probiotics may mediate an alleviating effect on depression symptomatic121—however, sample sizes remained rather small (n < 100) and no long-term effects were tested (up to 8 weeks).

Currently, several studies aim to identify microbial profiles in relation to disease and how microbial data can be used on a multimodal way to improve functional resolution, e.g. characterizing microbial profiles of individuals suffering from type-1 diabetes122. Yet, evidence for specific effects of diet on cognitive functions and behavior through changes in the microbiome remains scarce. A recent study indicated the possibility that our food choices determine the quantity and quality of neurotransmitter-precursor levels that we ingest, which in turn might influence behavior, as shown by lower fairness during a money-redistribution task, called the ultimatum game, after a high-carbohydrate/protein ratio breakfast than after a low-ratio breakfast123. Strang et al. found that precursor forms of serotonin and dopamine, measured in blood serum, predicted behavior in this task, and precursor concentrations were dependent on the nutrient profile of the consumed meal before the task. Also on a cross-sectional level tryptophan metabolites from fecal samples have been associated with amygdala-reward network functional connectivity124. On top of the dietary composition per se, the microbiota largely contributes to neurotransmitter precursor concentrations; thus, in addition to measuring neurotransmitter precursors in the serum, metabolomics on fecal samples would be helpful to further understand the functional role of the gut microbiota in neurotransmitter biosynthesis and regulation125.

Indicating the relevance of gut microbiota for cognition, a first human study assessing cognitive tests and brain imaging could distinguish obese from nonobese individuals using a microbial profile126. The authors found a specific microbiotic profile, particularly defined by Actinobacteria phylum abundance, that was associated with microstructural properties in the hypothalamus and in the caudate nucleus. Further, a preclinical study tested whether probiotics could enhance cognitive function in healthy subjects, showing small effects on improved memory performance and reduced stress levels127.

A recent study could show that microbial composition influences cerebral amyloidogenesis in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease128. Health status of the donor mouse seemingly mattered: fecal transplants from transgenic mice had a larger impact on amyloid beta proliferation in the brain compared to wild-type feces. Translational interpretations to humans should be done with caution if at all—yet the results remain elucidative for showing a link between the gut microbiome and brain metabolism.

The evidence for effects of strictly plant-based diets on cognition is very limited. For other plant-based diets such as the Mediterranean diet or DASH diet, there are more available studies that indicate protective effects on cardiovascular and brain health in the aging population (reviewed in refs. 129,130). Several attempts have been made to clarify potential underlying mechanisms, for example using supplementary plant polyphenols, fish/fish-oil consumption or whole dietary pattern change in RCTs131–137, yet results are not always equivocal and large-scale intervention studies have yet to be completed.

The overall findings of this paragraph add to the evidence that microbial diversity may be associated with brain health, although underlying mechanisms and candidate signaling molecules remain unknown.

Conclusion

Based on this systematic review of randomized clinical trials, there is an overall robust support for beneficial effects of a plant-based diet on metabolic measures in health and disease. However, the evidence for cognitive and mental effects of a plant-based diet is still inconclusive. Also, it is not clear whether putative effects are due to the diet per se, certain nutrients of the diet (or the avoidance of certain animal-based nutrients) or other factors associated with vegetarian/vegan diets. Evolving concepts argue that emotional distress and mental illnesses are linked to the role of microbiota in neurological function and can be potentially treated via microbial intervention strategies19. Moreover, it has been claimed that certain diseases, such as obesity, are caused by a specific microbial composition138, and that a balanced gut microbiome is related to healthy ageing111. In this light, it seems possible that a plant-based diet is able to influence brain function by still unclear underlying mechanisms of an altered microbial status and systemic metabolic alterations. However, to our knowledge there are no studies linking plant-based diets and cognitive abilities on a neural level, which are urgently needed, due to the hidden potential as a dietary therapeutic tool. Also, further studies are needed to disentangle motivational beliefs on a psychological level that lead to a change in diet from causal effects on the body and the brain mediated e.g., by metabolic alterations or a change in the gut microbiome.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a scholarship (E.M.) by the German Federal Environmental Foundation and by the grants of the German Research Foundation contract grant number CRC 1052 “Obesity mechanisms” Project A1 (AV) and WI 3342/3-1 (A.V.W.).

Authors’ contributions

E.M., A.V. and A.V.W. designed research; E.M. conducted research; E.M., S.H. and A.V.W. analyzed data; E.M. and A.V.W. wrote the paper; E.M., A.V. and A.V.W. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-019-0552-0).

References

- 1.GOV.UK. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: headline results from years 1, 2 and 3 (combined) of the rolling programme 2008/09–2010/11. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-diet-and-nutrition-survey-headline-results-from-years-1-2-and-3-combined-of-the-rolling-programme-200809-201011 (2012).

- 2.V. E. B. U. Deutschland & Joy, S. Anzahl der Veganer und Vegetarier in Deutschland. Stand31, 2016 (2015).

- 3.Mensink, G., Barbosa, C. L. & Brettschneider, A.-K. Verbreitung der vegetarischen Ernährungsweise in Deutschland 1, (2016).

- 4.The Vegetarian Resource Group. How many adults in the U.S. are vegetarian and vegan? http://www.vrg.org/nutshell/Polls/2016_adults_veg.htm (2016).

- 5.Rosenfeld DL, Burrow AL. Vegetarian on purpose: understanding the motivations of plant-based dieters. Appetite. 2017;116:456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orlich MJ, et al. Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:1230–1238. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le LT, Sabaté J. Beyond meatless, the health effects of vegan diets: findings from the Adventist cohorts. Nutrients. 2014;6:2131–2147. doi: 10.3390/nu6062131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mihrshahi S, et al. Vegetarian diet and all-cause mortality: evidence from a large population-based Australian cohort-the 45 and up study. Prev. Med. 2017;97:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Key TJ, et al. Mortality in British vegetarians: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;89:1613S–1619S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fung TT, et al. Low-carbohydrate diets and all-cause and cause-specific mortalitytwo cohort studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010;153:289–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-5-201009070-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song M, et al. Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016;176:1453–1463. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu FB. Plant-based foods and prevention of cardiovascular disease: an overview. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;78:544S–551S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.544S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tonstad S, Butler T, Yan R, Fraser GE. Type of vegetarian diet, body weight, and prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:791–796. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McEvoy CT, Temple N, Woodside JV. Vegetarian diets, low-meat diets and health: a review. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:2287–2294. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012000936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glick-Bauer M, Yeh M-C. The health advantage of a vegan diet: exploring the gut microbiota connection. Nutrients. 2014;6:4822–4838. doi: 10.3390/nu6114822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Appleby PN, Key TJ. The long-term health of vegetarians and vegans. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016;75:287–293. doi: 10.1017/S0029665115004334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eichelmann F, Schwingshackl L, Fedirko V, Aleksandrova K. Effect of plant‐based diets on obesity‐related inflammatory profiles: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of intervention trials. Obes. Rev. 2016;17:1067–1079. doi: 10.1111/obr.12439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMacken M, Shah S. A plant-based diet for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2017;14:342. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers GB, et al. From gut dysbiosis to altered brain function and mental illness: mechanisms and pathways. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:738–748. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hibbeln JR, Northstone K, Evans J, Golding J. Vegetarian diets and depressive symptoms among men. J. Affect Disord. 2018;225:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forestell CA, Nezlek JB. Vegetarianism, depression, and the five factor model of personality. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2018;57:246–259. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2018.1455675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matta J, et al. Depressive symptoms and vegetarian diets: results from the constances cohort. Nutrients. 2018;10:1695. doi: 10.3390/nu10111695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal U, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of a nutrition intervention program in a multiethnic adult population in the corporate setting reduces depression and anxiety and improves quality of life: the GEICO study. Am. J. Health Promot. 2015;29:245–254. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130218-QUAN-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beezhold B, Radnitz C, Rinne A, DiMatteo J. Vegans report less stress and anxiety than omnivores. Nutr. Neurosci. 2015;18:289–296. doi: 10.1179/1476830514Y.0000000164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnard ND, Levin SM, Yokoyama Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis of changes in body weight in clinical trials of vegetarian diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015;115:954–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang R-Y, Huang C-C, Hu FB, Chavarro JE. Vegetarian diets and weight reduction: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016;31:109–116. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3390-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benatar JR, Stewart RAH. Cardiometabolic risk factors in vegans: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0209086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee Y-M, et al. Effect of a brown rice based vegan diet and conventional diabetic diet on glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes: a 12-week randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0155918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkins DJA, et al. Effect of a 6-month vegan low-carbohydrate (‘Eco-Atkins’) diet on cardiovascular risk factors and body weight in hyperlipidaemic adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e003505. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkins DJA, et al. The effect of a plant-based low-carbohydrate (“Eco-Atkins”) diet on body weight and blood lipid concentrations in hyperlipidemic subjects. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009;169:1046–1054. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnard Neal D, Cohen Joshua, Jenkins David JA, Turner-McGrievy Gabrielle, Gloede Lise, Green Amber, Ferdowsian Hope. A low-fat vegan diet and a conventional diabetes diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled, 74-wk clinical trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89(5):1588S–1596S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahleová Hana, Hill Martin, Pelikánová Terezie. Vegetarian vs. conventional diabetic diet - A 1-year follow-up. Cor et Vasa. 2014;56(2):e140–e144. doi: 10.1016/j.crvasa.2013.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turner-McGrievy GM, Davidson CR, Wingard EE, Wilcox S, Frongillo EA. Comparative effectiveness of plant-based diets for weight loss: a randomized controlled trial of five different diets. Nutrition. 2015;31:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;82:222S–225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.David LA, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu GD, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science (80-) 2011;334:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaartinen K, et al. Vegan diet alleviates fibromyalgia symptoms. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2000;29:308–313. doi: 10.1080/030097400447697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yadav V, et al. Low-fat, plant-based diet in multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2016;9:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rauma AL, Nenonen M, Helve T, Hänninen O. Effect of a strict vegan diet on energy and nutrient intakes by Finnish rheumatoid patients. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993;47:747–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elkan A-C, et al. Gluten-free vegan diet induces decreased LDL and oxidized LDL levels and raised atheroprotective natural antibodies against phosphorylcholine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2008;10:R34. doi: 10.1186/ar2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karlsson J, et al. Predictors and effects of long-term dieting on mental well-being and weight loss in obese women. Appetite. 1994;23:15–26. doi: 10.1006/appe.1994.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beezhold BL, Johnston CS. Restriction of meat, fish, and poultry in omnivores improves mood: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2012;11:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yokoyama Y, Barnard ND, Levin SM, Watanabe M. Vegetarian diets and glycemic control in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2014;4:373–382. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2014.10.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutliffe JT, Wilson LD, de Heer HD, Foster RL, Carnot MJ. C-reactive protein response to a vegan lifestyle intervention. Complement Ther. Med. 2015;23:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strasser B, Gostner JM, Fuchs D. Mood, food, and cognition: role of tryptophan and serotonin. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2016;19:55–61. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Mahony SM, Clarke G, Borre YE, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behav. Brain Res. 2015;277:32–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davey GK, et al. EPIC–Oxford: lifestyle characteristics and nutrient intakes in a cohort of 33 883 meat-eaters and 31 546 non meat-eaters in the UK. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6:259–268. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schüpbach R, Wegmüller R, Berguerand C, Bui M, Herter-Aeberli I. Micronutrient status and intake in omnivores, vegetarians and vegans in Switzerland. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017;56:283–293. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-1079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clarys P, et al. Comparison of nutritional quality of the vegan, vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian and omnivorous diet. Nutrients. 2014;6:1318–1332. doi: 10.3390/nu6031318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park JE, Miller M, Rhyne J, Wang Z, Hazen SL. Differential effect of short-term popular diets on TMAO and other cardio-metabolic risk markers. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019;29:513–517. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Psichas A, et al. The short chain fatty acid propionate stimulates GLP-1 and PYY secretion via free fatty acid receptor 2 in rodents. Int J. Obes. 2015;39:424. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin HV, et al. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Canfora EE, Jocken JW, Blaak EE. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015;11:577. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo Y, et al. Physiological evidence for the involvement of peptide YY in the regulation of energy homeostasis in humans. Obesity. 2006;14:1562–1570. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holzer P, Reichmann F, Farzi A. Neuropeptide Y, peptide YY and pancreatic polypeptide in the gut–brain axis. Neuropeptides. 2012;46:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kendall CWC, Esfahani A, Jenkins DJA. The link between dietary fibre and human health. Food Hydrocoll. 2010;24:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reynolds Andrew, Mann Jim, Cummings John, Winter Nicola, Mete Evelyn, Te Morenga Lisa. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The Lancet. 2019;393(10170):434–445. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31809-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Menni C, et al. Gut microbiome diversity and high-fibre intake are related to lower long-term weight gain. Int. J. Obes. 2017;41:1099. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, Christophe E. Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006;444:875. doi: 10.1038/nature05487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferreira Caroline Marcantonio, Vieira Angélica Thomaz, Vinolo Marco Aurelio Ramirez, Oliveira Fernando A., Curi Rui, Martins Flaviano dos Santos. The Central Role of the Gut Microbiota in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Journal of Immunology Research. 2014;2014:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2014/689492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wersching H, et al. Serum C-reactive protein is linked to cerebral microstructural integrity and cognitive function. Neurology. 2010;74:1022–1029. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d7b45b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gu Y, et al. Circulating inflammatory biomarkers in relation to brain structural measurements in a non-demented elderly population. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017;65:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lampe L, et al. Visceral obesity relates to deep white matter hyperintensities via inflammation. Ann. Neurol. 2018;85:194–203. doi: 10.1002/ana.25396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmidt R, et al. Early inflammation and dementia: a 25‐year follow‐up of the Honolulu‐Asia Aging Study. Ann. Neurol. 2002;52:168–174. doi: 10.1002/ana.10265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosano C, Marsland AL, Gianaros PJ. Maintaining brain health by monitoring inflammatory processes: a mechanism to promote successful aging. Aging Dis. 2012;3:16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tangney CC, et al. Relation of DASH-and Mediterranean-like dietary patterns to cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology. 2014;83:1410–1416. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Craddock JC, Probst Y, Peoples G. Vegetarian nutrition—comparing physical performance of omnivorous and vegetarian athletes. J. Nutr. Intermed. Metab. 2016;4:19. doi: 10.1016/j.jnim.2015.12.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu RH. Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;78:517S–520S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.517S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boffetta P, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and overall cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010;102:529–537. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reczek CR, Chandel NS. Revisiting vitamin C and cancer. Science (80-) 2015;350:1317–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Probst YC, Guan VX, Kent K. Dietary phytochemical intake from foods and health outcomes: a systematic review protocol and preliminary scoping. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013337. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hartmann R, Meisel H. Food-derived peptides with biological activity: from research to food applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007;18:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tillisch K, et al. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1394–1401. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gibson GR, et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on thedefinition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017;14:491. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nisha AR. Antibiotic residues-a global health hazard. Vet. World. 2008;1:375–377. doi: 10.5455/vetworld.2008.375-377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang H, et al. Antibiotic residues in meat, milk and aquatic products in Shanghai and human exposure assessment. Food Control. 2017;80:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.04.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bertazzi PA, et al. Health effects of dioxin exposure: a 20-year mortality study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001;153:1031–1044. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.11.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bouvard V, et al. Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1599–1600. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van Audenhaege M, et al. Impact of food consumption habits on the pesticide dietary intake: comparison between a French vegetarian and the general population. Food Addit. Contam. 2009;26:1372–1388. doi: 10.1080/02652030903031171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jacobs DR, Tapsell LC. Food synergy: the key to a healthy diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013;72:200–206. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kawano Y, Yanai K. Foodcam: a real-time food recognition system on a smartphone. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2015;74:5263–5287. doi: 10.1007/s11042-014-2000-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Garcia-Perez I, et al. Objective assessment of dietary patterns by use of metabolic phenotyping: a randomised, controlled, crossover trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:184–195. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30419-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Turner-McGrievy GM, et al. Changes in nutrient intake and dietary quality among participants with type 2 diabetes following a low-fat vegan diet or a conventional diabetes diet for 22 weeks. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008;108:1636–1645. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gilsing AMJ, et al. Serum concentrations of vitamin B12 and folate in British male omnivores, vegetarians and vegans: results from a cross-sectional analysis of the EPIC-Oxford cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010;64:933–939. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Allen LH. How common is vitamin B-12 deficiency? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;89:693S–696S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26947A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pawlak R, Parrott SJ, Raj S, Cullum-Dugan D, Lucus D. How prevalent is vitamin B12 deficiency among vegetarians? Nutr. Rev. 2013;71:110–117. doi: 10.1111/nure.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rizzo G, et al. Vitamin B12 among vegetarians: status, assessment and supplementation. Nutrients. 2016;8:767. doi: 10.3390/nu8120767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stabler SP. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:149–160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1113996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Köbe T, et al. Vitamin B-12 concentration, memory performance, and hippocampal structure in patients with mild cognitive impairment, 2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016;103:1045–1054. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.116970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ganguly P, Alam SF. Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutr. J. 2015;14:6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-14-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McCaddon A, Regland B, Hudson P, Davies G. Functional vitamin B12 deficiency and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2002;58:1395–1399. doi: 10.1212/WNL.58.9.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Moore E, et al. Cognitive impairment and vitamin B12: a review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:541–556. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Spence JD. Metabolic vitamin B12 deficiency: a missed opportunity to prevent dementia and stroke. Nutr. Res. 2016;36:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nexo E, Hoffmann-Lücke E. Holotranscobalamin, a marker of vitamin B-12 status: analytical aspects and clinical utility. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011;94:359S–365S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.013458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Haider LM, Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G, Ekmekcioglu C. The effect of vegetarian diets on iron status in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018;58:1359–1374. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1259210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lozoff B, Georgieff MK, et al. Iron deficiency and brain development. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2006;13:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ayton, S. et al. Brain iron is associated with accelerated cognitive decline in people with Alzheimer pathology. Mol. Psychiatry1, 10.1038/s41380-019-0375-7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. Iron treatment normalizes cognitive functioning in young women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;85:778–787. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Beard J. Iron deficiency alters brain development and functioning. J. Nutr. 2003;133:1468S–1472S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1468S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Melina V, Craig W, Levin S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: vegetarian diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016;116:1970–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Richter M, et al. For the German Nutrition Society (DGE)(2016) Vegan diet. Position of the German Nutrition Society (DGE) Ernaehrungsumschau. 2016;63:92–102. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peterson J, et al. The NIH human microbiome project. Genome Res. 2009;19:2317–2323. doi: 10.1101/gr.096651.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arumugam M, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2013;473:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bamberger C, et al. A walnut-enriched diet affects gut microbiome in healthy Caucasian subjects: a randomized, controlled trial. Nutrients. 2018;10:244. doi: 10.3390/nu10020244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Holscher HD, et al. Walnut consumption alters the gastrointestinal microbiota, microbially derived secondary bile acids, and health markers in healthy adults: a randomized controlled trial. J. Nutr. 2018;148:861–867. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hjorth MF, et al. Pre-treatment microbial Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio, determines body fat loss success during a 6-month randomized controlled diet intervention. Int J. Obes. 2018;42:580. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hansen TH, et al. Impact of a vegan diet on the human salivary microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5847. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24207-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kim M, Hwang S, Park E, Bae J. Strict vegetarian diet improves the risk factors associated with metabolic diseases by modulating gut microbiota and reducing intestinal inflammation. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2013;5:765–775. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zimmer J, et al. A vegan or vegetarian diet substantially alters the human colonic faecal microbiota. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012;66:53–60. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.De Filippis F, Pellegrini N, Laghi L, Gobbetti M, Ercolini D. Unusual sub-genus associations of faecal Prevotella and Bacteroides with specific dietary patterns. Microbiome. 2016;4:57. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0202-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kumar M, Babaei P, Ji B, Nielsen J. Human gut microbiota and healthy aging: Recent developments and future prospective. Nutr. Health Aging. 2016;4:3–16. doi: 10.3233/NHA-150002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wu GD, et al. Comparative metabolomics in vegans and omnivores reveal constraints on diet-dependent gut microbiota metabolite production. Gut. 2014;65:63–72. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Morrison DJ, Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:189–200. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wanders AJ, et al. Effects of dietary fibre on subjective appetite, energy intake and body weight: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2011;12:724–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]