Abstract

Objective

IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder and commonly presents in children and adolescences, presented as diarrhoea, constipation or mixed type. Blastocystis is a common intestinal protozoa found worldwide, which pathogenicity is still controversial. This study aimed to identify the risk factors of IBS, the association between IBS types with Blastocystis subtypes and analyse Blastocystis pathogenicity.

Design

A comparative cross-sectional study was conducted among senior high school students. Rome III Criteria for IBS diagnosis, questionnaires on the risk factors of IBS and types of IBS were recorded. Students were further selected and classified into IBS and non-IBS groups to analyse the association between IBS, IBS types with Blastocystis infection and its subtypes. Direct microscopic stool examination to identify single Blastocystis infection was performed, followed by culture in Jones' medium, PCR, sequencing of 18S rRNA and phylogenetic analysis to determine Blastocystis subtype. Data was analysed using SPSS v22.0 and P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant (95% confidence intervals).

Results

IBS was found in 30.2% of 454 students, consisted of 33.3% IBS Diarrhoea, 27.7% IBS Mixed, 27.7% IBS Unclassified and 11.1% IBS Constipation. Major risk factors to IBS consisted of family history of recurrent abdominal pain, abuse, bullying and female gender in respective order (OR 3.6–2.1). Blastocystis ST-1 was significantly associated to IBS-D with 2.9 times risk factor.

Conclusions

Blastocystis infection is a risk factor to develop IBS-D type in adolescence; Blastocystis ST-1 can be regarded as a pathogenic subtype.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, Diarrhoea, Risk factors, Intestinal protozoa

1. Introduction

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort with defecation disorders (Hyams et al., 1996). It is commonly present in children and adolescences without abnormality on physical examination. Prevalence of IBS is higher than other gastrointestinal disorders, in developing and developed countries which is about 10–15% and 21% in school children and adolescences respectively in the UK. In Asia, the IBS prevalence were 2.9–15.6% in school children and 5.8–25.7% among adolescences (Lee, 2010; Dong et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2010). A lower prevalence was observed among adolescences in Jakarta (Fillekes et al., 2014). IBS can be categorized into four subtypes according to Rome III criteria, Bristol scale: Diarrhoea type, Constipation type, Mixed type and Unclassified (Rajindrajith and Devanarayana, 2012).

The exact aetiology of IBS remains to be determined, whether it is caused by hereditary or environmental factors such as Blastocystis infection, as was reported in Pakistan (Rajindrajith and Devanarayana, 2012). It is possibly due to complex interaction between infection, inflammation, visceral hypersensitivity, allergy and gut motility disorders (Dong et al., 2005; Apley and Naish, 1958). Blastocystis is a common intestinal parasite with extensive genetic variability; its pathogenic potential in human intestine is still controversial because it is found in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals (Self et al., 2014; Yakoob et al., 2010a; Yakoob et al., 2004; Ramirez-Miranda et al., 2010). There has been quite a few studies looking for the association between IBS and Blastocystis but has not come into one consensus on the pathogenicity of Blastocystis in IBS. Recent surveys on parasites infection among children and adolescence in Indonesia showed 30% and 40% Blastocystis spp. prevalence respectively (Sari et al., 2018; Sungkar et al., 2015). The clinical consequences of Blastocystis infection are mainly diarrhoea or abdominal pain with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms (Self et al., 2014; Yakoob et al., 2010a, Yakoob et al., 2004; Ramirez-Miranda et al., 2010).

This study aimed to conduct extensive analysis on IBS in the community to find the risk factors of IBS in adolescence and IBS relation to Blastocystis infection.

2. Methods

A prospective cross-sectional study was carried out in two stages. The first stage aimed to identify the risk factors of IBS among adolescences. The second stage was to analyse the role of Blastocystis and its subtypes in IBS and non-IBS groups. According to sample size formula calculation, a minimum number of 70 subjects in each group were required for statistical analyses.

2.1. Study population

To identify the risk factors associated to IBS among adolescences, a community-based survey was conducted with comparative cross sectional two groups among six senior high school students in Palembang-South Sumatra which is one-hour flight from Jakarta, followed by a minimum 2 h local transport. Student's general characteristics and physical examination were recorded. Nutritional status was determined based on anthropometric examination and plotted onto the CDC growth chart. The Rome III criteria for IBS diagnosis was applied i.e. abdominal discomfort or pain at least once per week for >2 months and it was associated with at least two of the three following features for at least 25% of the time: (1) Abdominal pain improved with defecation, (2) Onset associated with change in defecation frequency, (3) Onset associated with change in stools consistency.

The inclusion criteria were good health; those with chronic diseases such as asthma, diabetes mellitus, all variant of heart, renal and blood diseases, congenital anomaly were excluded. Those who had received antibiotics and antiparasitic treatment (metronidazole, tinidazole, albendazole) in the last two weeks were also excluded. A team was formed consisting of five physicians, trained in detail for IBS identification and understanding the questionnaire. Questionnaire was developed, based on the recommendation of the Rome III Criteria and distributed among the students on school visits; understanding of the questions was assisted by the investigators (Hyams et al., 2016). Inform consent was obtained from school administrators and parents before commencing the study. There were 454 adolescences eligible to participate in the first stage of this study. They were interviewed and underwent physical examination to identify the presence of IBS, and then were classified into IBS and non-IBS groups.

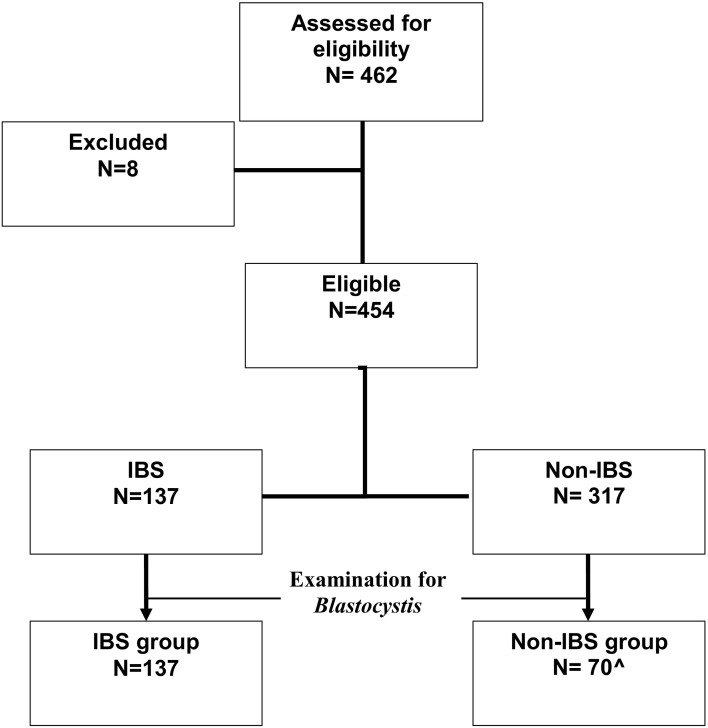

To identify the association between IBS and Blastocystis infection; subjects from each group were further selected by simple random sampling, with minimum 70 subjects for each group according to the sample size formula calculation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study workflow diagram.

^minimum sample requirement based on the sample size calculation formula.

2.2. Diagnostic criteria for IBS and IBS subtypes (Rajindrajith and Devanarayana, 2012)

Subjects with IBS were classified into four subtypes according to Rome III-Bristol scale: IBS with constipation (IBS-C) when hard or lumpy stools for at least ≥25% of the time; IBS with diarrhoea (IBS-D) when loose, mushy or watery stools for at least ≥25% of defecations; IBS with either hard or lumpy stools and loose, mushy or watery stools for ≥25% of defecations were identified as mixed IBS (IBS-M). Those fulfilled the criteria without diarrhoea and constipation were grouped as unclassified IBS (IBS-U).

2.3. Identification of Blastocystis spp.

Microscopic examination with 1% lugol solution was carried out on sub-sample 207 stools, originated from all IBS individuals (n = 137) and 70 non-IBS (Fig. 1). Approximately 2 mg of feces was smeared on a glass slide with one drop lugol solution and covered with a cover slip, examined under medium power (40×) objective lens. Stools positive for Blastocystis spp. were cultured in Jones' medium supplemented with 10% horse serum (Leelayoova et al., 2002) to amplify the number of Blastocystis. Cultures were incubated at room temperature then transported to Parasitology laboratory in Jakarta.

2.4. DNA isolation and amplification (Scicluna et al., 2006)

DNA was extracted from the cultures using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit following the procedure from the manufacturer (Qiagen, GmbH, cat no. 51306) and kept in −20 °C. PCR amplification of 18S rRNA was performed in 25 μl reaction with TopTaq Polymerase Master Mix Kit (Qiagen, cat no. 200403), 200 mM each dNTP, 10% Bovine Serum Albumin and 2 μl DNA template. The primers were as follows:

Forward: RD5 5′-ATC-TGG-TTG-ATC-CTG-CCA-GT-3′

Reverse: BhRDr 5′-GAG-CTT-TTT-AAC-TGC-AAC-AAC-G-3′

The PCR reactions were carried out on MJ Research PTC 200 thermocycler and adjusted for optimum reaction, consisted of: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 6 min then 30 cycles at 93 °C for 2 min, 65 °C for 2 min, 72 °C for 2 min. The last cycle was 10 min at 72 °C. The 600 bp PCR product was electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel and visualized with UV transilluminator.

2.5. DNA sequencing and subtype analysis

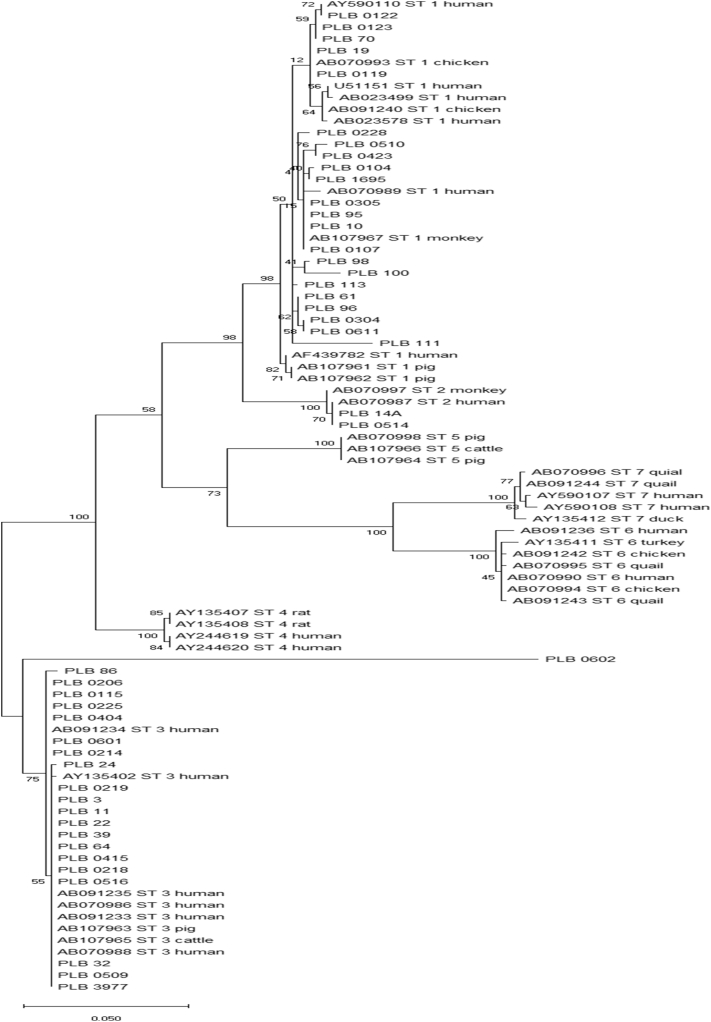

All the amplicons underwent bi-directional sequencing, the chromatograms were validated. Blasted sequences were aligned to Blastocystis database from the GenBank, using Mega 6 software (en.bio-soft.net/tree/MEGA.htm). Phylogenetic tree was set up employing the Maximum Likelihood method and Kimura 2-parameter model (Kimura, 1980). The tree with the highest log likelihood (−2575.97) is shown. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X software (Kumar et al., 2018).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and percentage for categorical data as univariate analysis. An independent sample t-test, Pearson chi-square test and/or Fisher's exact test were also used whenever appropriate and P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant (95% confidence intervals). All P values were two sided. Data was analysed using SPSS v22.0 statistical package. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia (774/UN2.F1/ETIK/2017; 21st August 2017).

3. Results

3.1. Risk factors to IBS

Table 1 shows the profile of the study population. As many as 454 high school students were enrolled in this study, consisted of 37.2% males and 62.8% females; with average age of 15.8 ± 0.97 year. IBS was found in 137 students (30.2%). The risk factors related to IBS that showed significant associations can be classified into high risk (OR > 3.0) consisted of family history of recurrent abdominal pain, psychosocial problems (abuse); moderate risk (2 < OR ≤ 3), consisted of bullying, Blastocystis infection, female gender and history of constipation in respective order; and low risk (1.5 < OR ≤ 2) consisted of grumpy father, particular diet (beverages, nuts, spicy soup) and history of diarrhoea.

Table 1.

Assessment of the risk factors related to IBS (n = 454).

| Characteristic | IBS (+) |

IBS (−) |

Total | P value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Age | ||||||

| - 14–16 Y | 110 (80,3) | 225 (70,9) | 335 | 0,051* | 1,67 | 1025–2708 |

| - 17–18 Y | 27 (19,7) | 92 (29,1) | 119 | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| - Female | 102 (74,5) | 183 (57,7) | 285 | 0,001* | 2,13 | 1369–3326 |

| - Male | 35 (25,2) | 134 (42,5) | 169 | |||

| Nutritional status | ||||||

| - Malnourish | 37 (27,0) | 98 (30,9) | 135 | 0,469* | 0,83 | 0,529–1292 |

| - Good | 100 (73,0) | 219 (69,1) | 319 | |||

| Gestational age | ||||||

| - Preterm | 3 (2,2) | 5 (1,6) | 8 | 0,702** | 1,40 | 0,329–5929 |

| - A term | 134 (97,8) | 312 (98,4) | 446 | |||

| Birth weight | ||||||

| - <2500 g | 2 (1,5) | 3 (0,9) | 5 | 0,640** | 1,56 | 0,256–9386 |

| - ≥2500 g | 135 (98,5) | 314 (99,1) | 449 | |||

| No of sibling | ||||||

| - ≤2 | 35 (25,5) | 79 (24,9) | 114 | 0,981* | 1,03 | 0,652 –1639 |

| - >2 | 102 (74,5) | 238 (75,3) | 340 | |||

| Birth order | ||||||

| - ≤3 | 109 (79,6) | 277 (87,4) | 386 | 0,046* | 0,56 | 0,330–0,956 |

| - >3 | 28 (20,4) | 40 (12,6) | 68 | |||

| Parents' marital status | ||||||

| - Married | 116 (84,7) | 283 (89,3) | 399 | 0,221* | 0,66 | 0,370–1192 |

| - Divorced | 21 (15,3) | 34 (10,7) | 55 | |||

| Mother's behavior | ||||||

| - Grumpy | 45 (32,8) | 83 (26,2) | 128 | 0,182* | 1,38 | 0,892–2132 |

| - Patient | 92 (67,2) | 234 (73,8) | 326 | |||

| Father's behavior | ||||||

| - Grumpy | 35 (25,5) | 53 (16,7) | 88 | 0,040* | 1,71 | 1053–2774 |

| - Patient | 102 (74,5) | 264 (83,3) | 366 | |||

| Psychosocial problems | ||||||

| - Being attacked | 24 (37,5) | 40 (62,5) | 64 | 0,219** | 1,47 | 0,847–2553 |

| - Sexual abuse | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 4 | 0,008** | 3,38 | 2934–3902 |

| - Fighting | 29 (31,2) | 64 (68,8) | 93 | 0,912* | 1,06 | 0,648–1738 |

| - Bullying | 12 (52,2) | 11 (47,8) | 23 | 0,034* | 2,67 | 1148–6212 |

| - Trauma | 18 (30,0) | 42 (70,0) | 60 | 1000* | 0,99 | 0,548–1791 |

| - Negative emotions | 33 (31,4) | 72 (68,6) | 105 | 0,843* | 1,08 | 0,674–1730 |

| - Abuse | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0,091** | 3,35 | 2907–3856 |

| Diet | ||||||

| - Fish cake | 101 (31,0) | 225 (69,0) | 326 | 0,629* | 1,15 | 0,731–1801 |

| - Sweet layer cakes | 6 (31,6) | 13 (68,4) | 19 | 1000* | 1,07 | 0,398–2879 |

| - Spicy soup (Pindang) | 84 (34,4) | 160 (65,6) | 244 | 0,043* | 1,56 | 1034–2339 |

| - Steam spicy fish | 22 (29,7) | 52 (70,3) | 74 | 1000* | 0,98 | 0,566–1680 |

| - Milk | 100 (31,1) | 222 (68,9) | 322 | 0,599* | 1,16 | 0,740–1809 |

| - Canned foods | 72 (31,7) | 155 (68,3) | 227 | 0,540* | 1,16 | 0,775–1729 |

| - Processed meats | 60 (31,1) | 133 (68,9) | 193 | 0,794* | 1,08 | 0,719 -1616 |

| - Nuts | 70 (38,9) | 110 (61,1) | 180 | 0,002* | 1,97 | 1309–2954 |

| - Fried snacks | 125 (31,3) | 274 (68,7) | 399 | 0,226* | 1,60 | 0,813–3138 |

| - Tea | 81 (31,0) | 180 (69,0) | 261 | 0,719* | 1,10 | 0,733–1653 |

| - Coffee | 29 (26,6) | 80 (73,4) | 109 | 0,417* | 0,79 | 0,491–1288 |

| - Beverages | 96 (35,7) | 173 (64,3) | 269 | 0,003* | 1,95 | 1271–2988 |

| Eating duration | ||||||

| - ≤10 min | 10 (7,3) | 24 (7,6) | 34 | 1000 | 0,96 | 0,447–2069 |

| - >10 min | 127 (92,7) | 293 (92,4) | 420 | |||

| Previous illness | ||||||

| - Diarrhoea | 35 (41.2) | 50 (58.8) | 85 | 0.020* | 1.83 | 1.124–2.987 |

| - Constipation | 24 (44.4) | 30 (55.6) | 54 | 0.023* | 2.03 | 1.139–3.626 |

| - Food allergies | 22 (34.4) | 50 (58.8) | 72 | 0.520* | 1.25 | 0.716–2.193 |

| Family history illness | ||||||

| Recurrent abdominal pain | 6 (7.4) | 4 (3.57) | 10 | 0.073** | 3.58 | 0.995–12.909 |

Chi square test (*Continuity correction, **Fisher's exact test).

Bold values indicates significance at P<0.05.

3.2. Association between IBS and Blastocystis infection

Blastocystis spp. was more prevalent among students with IBS than non-IBS (36.5% vs 28.6%) however there was no significant difference statistically (P = 0.325; PR = 1.4; 95% CI = 0.8–2.7). Students harbouring Blastocystis spp. infection had 1.6–1.8 times risk to suffer from IBS-Diarrhoea (IBS-D) or IBS-Unspecified (IBS-U) and unlikely to suffer from IBS-Constipation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between IBS, IBS types and Blastocystis infection.

| Blastocystis spp. | IBS |

IBS category |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 137) |

No (n = 70) |

IBS-D | IBS-C | IBS-M | IBS-U | |

| Yes | 50 (36.5%) |

20 (28.6%) |

21 | 6 | 9 | 14 |

| No | 87 (63.5%) |

50 (71.4%) |

29 | 20 | 21 | 17 |

| PR (CI 95%) | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.8 | |

| (0.8–2.7) | (0.8–3.1) | (0.2–1.4) | (0.3–1.8) | (0.8–3.8) | ||

| P⁎ | 0.325 | 0.218 | 0.310 | 0.788 | 0.214 | |

Note:

IBD-D = IBS with diarrhoea symptom.

IBS-M = IBS mix with either diarrhoea or constipation episode.

IBS-C = IBS with constipation symptom.

IBS-U = IBS unclassified.

Fisher's exact, P value = 0.05; PR = prevalence ratio; CI = confidence interval.

3.3. Association between Blastocystis strain with IBS type

Blastocystis spp. was found in IBS and non-IBS subjects by direct stool microscopic examination i.e. in 50 out of 137 IBS subjects (36.5%) and 20 out of 70 non-IBS (28.6%). There were 43 out of 70 Blastocystis positive samples had successfully undergone PCR and sequencing (Table 3). Three subtypes of Blastocystis, ST-1, ST-2 and ST-3 were identified (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Distribution of Blastocystis subtypes among IBS and its association with IBS type.

| Blastocystis strain | IBS |

IBS type |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n-137) |

No (n = 70) |

IBS-D | IBS-C | IBS-M | IBS-U | |

| ST-1 (n = 20) | 15 (10.9%) |

5 (7.1%) |

9 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| ST-2 (n = 2) | 2 (1.5%) |

0 (0%) |

0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| ST-3 (n = 21) | 14 (10.2%) |

7 (10.0%) |

3 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

Note:

IBD-D = IBS with diarrhoea symptom.

IBS-M = IBS mix with either diarrhoea or constipation episode.

IBS-C = IBS with constipation symptom.

IBS-U = IBS unclassified.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of Blastocystis spp. isolated from adolescences in Palembang (PLB).

There was higher proportion of ST-1 found in IBS group compared to the non-IBS (10.9% vs 7.1%), while ST-2 was found only in two students with IBS. The proportion of students harbouring Blastocystis ST-3 was similar between IBS and non-IBS (10.2% vs 10.0%); ST-3 did not show to affiliate to particular type of IBS (Table 3).

Further analysis showed that students infected with Blastocystis ST-1 were 2.9 times more likely to develop IBS-D which was statistically significant (Fisher's exact, P = 0.029, P < 0.05; 95% CI = 1.1–7.5). This finding suggests that ST-1 is likely to be the strain of Blastocystis associated with clinical manifestation IBS-diarrhoea type.

4. Discussion

Irritable Bowel Syndrome is a common disorder among adolescences with higher prevalence in western than Asian countries and was believed as a functional bowel disorder (Dong et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2010; Saito and Schoenfeld, 2002) This study showed higher prevalence of IBS among high school students in Indonesia compared to other Asian countries (Dong et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2010; Fillekes et al., 2014). The prevalence of IBS varies greatly among epidemiological studies (Dong et al., 2005; Saito and Schoenfeld, 2002; Rey and Talley, 2009; Canavan et al., 2014), potentially due to the criteria chosen to diagnose IBS, inclusion and exclusion criteria, gender distribution and sociodemographic factors. The Rome III Diagnostic Questionnaire for Paediatric Functional GI Disorders was used to diagnose IBS in this study (Hyams et al., 2016) which is different from the adult questionnaire, in which criteria had to be fulfilled for the prior three months with symptoms onset at least six months prior to diagnosis.

The risk factors significantly associated to IBS have been identified and can be classified into high risk factors: family history of recurrent abdominal pain and abuse; moderate risk factors: bullying, Blastocystis infection, female gender, history of constipation in the last 6 months and low risk factors: beverages, nuts, previous illness diarrhoea. Our study showed a moderate risk for female students to develop IBS, which was also observed in other similar studies (Rey and Talley, 2009; Anbardan et al., 2012). The gender difference in developing IBS is less dramatic in developing countries compared to western population (Rey and Talley, 2009) which could be due to gender-related effects on intestinal motor and sensory pathway and function (Baysoy et al., 2014).

Negative emotion such as psychosocial problem and abuse have long been recognized to be associated with IBS in adolescences (Chang et al., 2010; Rey and Talley, 2009); while Park et al. specifically addressed that early adverse life events increased the odds of having IBS; correlated with IBS severity and abdominal pain (Park et al., 2016). History of previous diarrhoea and constipation in the last six months also showed significant association with IBS with the risk factor about twice, suggesting a post infection-IBS resembling to IBS-D, as a common result of acute gastroenteritis (Harper et al., 2018). However, the risk factor of family history of recurrent abdominal pain has the highest odd to develop IBS, implying possibility of hereditary role in IBS.

There was a moderate risk for students harbouring Blastocystis infection to develop IBS. The overall prevalence of Blastocystis infection among the IBS group was higher than the non-IBS; more than one third of IBS students infected with Blastocystis spp. The IBS students harbouring Blastocystis, mostly suffered from IBS-diarrhoea (IBS-D) or IBS-U with estimated risk factor 1.6–1.8 times. Data prevalence of Blastocystis with IBS types was previously reported among adults and children <5 years, which showed an association between IBS-D and Blastocystis; while no reports among adolescence. There had also been no previous clear reports on association between IBS type and Blastocystis strain (Yakoob et al., 2010a, Yakoob et al., 2004); therefore this is the first report on complete assessment of IBS and in-depth analysis on the role of Blastocystis to IBS among adolescence.

In view of its pathogenic and non-pathogenic Blastocystis strains, three Blastocystis subtypes, ST-1, ST-2 and ST-3 were identified in this study; no significant association with IBS was observed. However, there was significant association between Blastocystis ST-1 with IBS-Diarrhoea with the risk factor 2.9 times; suggesting that Blastocystis ST-1 is likely to associate to the clinical manifestation diarrhoea and possibility of being a pathogenic strain. Blastocystis ST-3 and ST-1 are the main subtypes found among populations in China, Japan, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Malaysia, Germany, Indonesia, Egypt (Sari et al., 2018; Li et al., 2007; Yoshikawa et al., 2004; Hussein et al., 2008; Tan, 2008).

In view of possible pathogenic ST-1 in our study is in accordance to other studies such as in Egypt by Hussein et al. (2008) who demonstrated Blastocystis ST-1, isolated from patient with IBS caused mortality in rats and severe pathological changes, while Fouad et al. (2011) reported severe inflammatory changes in recto sigmoidal biopsy of IBS patients harbouring Blastocystis ST-1. Blastocystis ST-1 was also commonly found among IBS-D in Pakistan (Yakoob et al., 2010b). A meta-analysis by Rostami et al. (2017) involving 17 studies, showed the potential risk factors for IBS in patients infected by ST-1 and ST-3 subtypes with OR 4.40 and 1.94 respectively.

Blastocystis ST-3 was not associated with any IBS types; it is found in equal proportion among the four types of IBS. This finding is in agreement to Ragavan et al. (2014), that showed phenotypic variation within Blastocystis ST-3.

The prevalence of Blastocystis was investigated only by microscopic methods in this study, which is not possible to determine the exact prevalence of Blastocystis infection in the study population. It is necessary to do culture for better accuracy of diagnostic purpose (Stensvold, 2015). As culture facilities at the sample collection area was not available, not all cultures grew well at room temperature and subsequently affected the proportion of positive PCR results and subtype analysis. This situation has significant limitations to the study. However, in primary healthcare setting, microscopic examination should be considered as first line screening when handling IBS-D cases.

5. Conclusion

IBS in Indonesia was not merely functional bowel disorder, it has possible relationship with organic problem i.e. Blastocystis infection. Three subtypes of Blastocystis were observed (ST-1, ST-2 and ST-3) and ST-1 is considered to be a potential pathogenic species of Blastocystis spp., associated with IBS-diarrhoea type.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Drh. Muhaimin Ramdja, MSc, Trop. Med. Chief of Parasitology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Sriwijaya for his supports, participating high schools, and health district official for study permission.

Contributors

Conception and design of the study: AF, SB, AK; data collection: YK, AK, IPS; data preparation: YK, IPS; statistical analysis, data and sequence analysis and interpretation: AF, AK, YK, SB, IPS; writing and critical revision of the manuscript: YK, AK, SB, AF All authors approved the final version for publication.

Funding

Funded by Ministry of Research and High Education through Universitas Indonesia, Hibah TADOK (grant for Doctoral Study).

Ethics approval

The local ethical committee from Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia approved this study (774/UN2.F1/ETIK/2017; 21st August 2017).

Declaration of competing interest

None declared.

Footnotes

Patient consent was performed.

References

- Anbardan S.J., Daryani N.E., Fereshtehnejad S.-M. Gender role in irritable bowel syndrome: a comparison of irritable bowel syndrome module (ROME III) between male and female patients. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2012;18:70–77. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apley J., Naish N. Recurrent abdominal pains: a field survey of 1,000 school children. Arch. Dis. Child. 1958;33:165. doi: 10.1136/adc.33.168.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baysoy G., Güler-Baysoy N., Kesicioğlu A. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents in Turkey: effects of gender, lifestyle and psychological factors. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2014;56:604–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canavan C., West J., Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014;6:71–80. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S40245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F.-Y., Lu C.-L., Chen T.-S. The current prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Asia. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010;16:389–400. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.4.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L., Dingguo L., Xiaoxing X. An epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents and children in China: a school-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e393–e396. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillekes L., Prayogo A., Alatas F.S. Irritable bowel syndrome and its associated factors in adolescents. Paediatr. Indones. 2014;54:344–350. [Google Scholar]

- Fouad S.A., Basyoni M.M.A., Fahmy R.A., Kobaisi M.H. The pathogenic role of different Blastocystis hominis genotypes isolated from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Arab J. Gastroenterol. 2011;12(4):194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper A., Naghibi M., Garcha D. The role of bacteria, probiotics and diet in irritable bowel syndrome. Foods. 2018;7 doi: 10.3390/foods7020013. (pii:E13) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein E.M., Hussein A.M., Eida M.M. Pathophysiological variability of different genotypes of human Blastocystis hominis Egyptian isolates in experimentally infected rats. Parasitol. Res. 2008;102:853–860. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0833-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyams J.S., Burke G., Davis P.M. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. J. Pediatr. 1996;129:220–226. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyams J.S., Di Lorenzo C., Saps M. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: children and adolescents. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1456–1468. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.015. (e2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee O.Y. Prevalence and risk factors of irritable bowel syndrome in Asia. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010;16:5–7. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelayoova S., Taamasri P., Rangsin R. In-vitro cultivation: a sensitive method for detecting Blastocystis hominis. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2002;96:803–807. doi: 10.1179/000349802125002275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.H., Zhou X.N., Du Z.W. Molecular epidemiology of human Blastocystis in a village in Yunnan province, China. Parasitol. Int. 2007;56:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.H., Videlock E.J., Shih W. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with irritable bowel syndrome and gastrointestinal symptom severity. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016;28:1252–1260. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragavan D.R., Govind S.K., Tan T.C. Phenotypic variation in Blastocystis spp. ST3. Parasit. Vectors. 2014;7:404. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajindrajith S., Devanarayana N.M. Subtypes and symptomatology of irritable bowel syndrome in children and adolescents: a school-based survey using Rome III criteria. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2012;18:298–304. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.3.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Miranda M.E., Hernandez-Castellanos R., Lopez-Escamilla E. Parasites in Mexican patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a case-control study. Parasit. Vectors. 2010;3:96. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey E., Talley N.J. Irritable bowel syndrome: novel views on the epidemiology and potential risk factors. Dig. Liver Dis. 2009;41:772–780. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostami A., Riahi S.M., Haghighi A. The role of Blastocystis sp. and Dientamoeba fragilis in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasitol. Res. 2017;116:2361–2367. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5535-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito YA, Schoenfeld P, Locke III GR. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in North America: a systematic review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1910–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sari I.P., Benung M.R., Wahdini S. Diagnosis and identification of Blastocystis subtypes in primary school children in Jakarta. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2018;64:208–214. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmx051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scicluna S.M., Tawari B., Clark C.G. DNA barcoding of Blastocystis. Protist. 2006;157:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self M.M., Czyzewski D.I., Chumpitazi B.P. Subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome in children and adolescents. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:1468–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensvold C.R. Laboratory diagnosis of Blastocystis spp. Trop. Parasitol. 2015;5(1):3–5. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.149885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sungkar S., Pohan A.P.N., Ramadani A. Heavy burden of intestinal parasite infections in Kalena Rongo village, a rural area in South West Sumba, eastern part of Indonesia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1296. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2619-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K.S.W. New insights on classification, identification, and clinical relevance of Blastocystis spp. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008;21:639–665. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00022-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakoob J., Jafri W., Jafri N. Irritable bowel syndrome: in search of an etiology: role of Blastocystis hominis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004;70:383–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakoob J., Jafri W., Beg M.A. Blastocystis hominis and Dientamoeba fragilis in patients fulfilling irritable bowel syndrome criteria. Parasitol. Res. 2010;107:679–684. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1918-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakoob J., Jafri W., Beg M.A. Irritable bowel syndrome: is it associated with genotypes of Blastocystis hominis. Parasitol. Res. 2010;106:1033–1038. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1761-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H., Wu Z., Kimata I. Polymerase chain reaction-based genotype classification among human Blastocystis hominis populations isolated from different countries. Parasitol. Res. 2004;92:22–29. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0995-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]