Abstract

Purpose:

Chlamydia trachomatis is a very common infection among young women in the United States; information on cumulative risk of infection is limited. We sought to estimate the cumulative risk of chlamydial infection for young women.

Methods

We measured cumulative risk of reported chlamydial infection for 14–34-year-old women in Florida between 2000 and 2011 using surveillance records and census estimates. We calculated reported infections per woman, analyzed first infections to get cumulative risk, and calculated risk of repeat infection over the 12-year period.

Results:

There were 457,595 infections reported among 15–34-year-old women. Reports increased annually from 25,390 to 51,536. Nineteen-year-olds were at highest risk with 5.1 infections reported per 100 women in 2011. There were 341,671 different women infected. Among women ages 14–17 in 2000, over 20% had at least one infection reported within 12 years, and among blacks, this risk was over 36% which underestimates risk because 18% of cases were missing race/ethnicity information. Repeat infections were common. Among 53,109 with chlamydia at ages 15–20 during 2000–2003, 36.7% had additional infections reported by 2011.

Conclusions:

More than one out of five women in Florida was reported as having chlamydia during her young-adult years; risk was highest for black women. True infection risks were likely much higher because many infections were not diagnosed or reported. Young women who had chlamydia were very likely to get reinfected. Rates of infection remain high despite years of screening. More information is needed on how to prevent chlamydial infection.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, incidence, prevalence, surveillance, epidemiology, pelvic inflammatory disease

Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis is a common infection, yet there is little information on how many women have acquired it at some point during their young-adult years. In 2011 chlamydia accounted for 71.1% of all notifiable infections in the United States,1 though many infections may remain undetected because most are asymptomatic.2 If left untreated, 10%–15% of chlamydial infections will progress to symptomatic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and others will progress to asymptomatic PID.3, 4 After having developed symptomatic PID, an estimated 9% of women develop infertility.3, 5 Therefore, annual screening to detect asymptomatic infections, and reduce the risk of PID,4, 6 is recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (Grade A recommendation) for all sexually-active women under age 25.7

Surveillance data show that the number of chlamydial infections reported among women in the United States has increased every year since reporting was first required by all states in 2000, and reached a total of 1,018,552 cases in 2011.8 This total is the number of infections reported in one year, and is higher than the number of women with an infection reported in one year because some women had multiple infections. Chlamydia prevalence has remained fairly stable in representative samples of 14–25-year-old women in the United States (4.1% in 1999–2000, and 3.8% in 2007–2008).9 Therefore, increases in reported cases are thought to represent increases in case detection due to increases in testing and the use of more sensitive tests, rather than true increases in prevalence.8, 9 These prevalence estimates can be projected to an estimated 660,000 chlamydial infections among 15–24-year-old women on one day in 2008.10 However, prevalence data do not tell us how many women had chlamydia at any time during that year, or during the many years that comprise a woman’s period of greatest risk (ages 15–24).

In Florida, reported sexually-transmitted infections are maintained in a secure, name-based, electronic surveillance database. This database allows us to measure the number of infections reported, the number of unique women reported with infections, and the number of women with multiple infections. Using census population estimates as denominators, we can estimate the risk of being reported with chlamydia for women living in Florida each year, and over the 12-year time period from 2000 through 2011.

Methods

Chlamydial infection has been reportable in Florida since 1993. Most reports to the health department come from laboratories. Duplicate case reports are removed by the county health departments or at the state level after confirmation of data completeness. We selected all cases reported among women in Florida starting in 2000, ending with cases diagnosed in 2011 and reported by March 19, 2012. Multiple infections from the same woman were considered separate infections if they were at least 30 days apart (to reduce multiple detections of the same infection). For denominators, we used census estimates by age, race, ethnicity, and year.11

We first examined all reported infections for women by demographic characteristics and year of report. Infections per woman were calculated using the census estimates of the number of women of that age living in Florida. Race/ethnicity information was missing for a large fraction of cases, so we did subgroup analyses for the group with the most cases, black women, but not for other race/ethnicity groups because the number of reported cases was less than (or nearly equal to) the number of cases with missing race.

Next, we limited our analysis to the first infection that a woman had in the database (starting in 2000) in order to determine the number of women who had at least one infection. To estimate risks, we divided the number of first infections for women of a certain age, by the census estimate for the number of women of that age living in Florida. Cumulative incidence of a first infection was estimated by adding risks calculated for women who were one year older for each year later (example: The risk of infection over two years for women who were 15 in 2000 is equal to the risk of first infection for 15-year-olds in 2000 plus the risk of first infection for 16-year-olds in 2001).

Finally, we studied women with more than one reported infection. The time to the first-reported repeat infection was estimated using life-table analyses in SAS for women who were between 15 and 20 years old at the time of their first chlamydial infection in 2000–2003.

We did not calculate confidence intervals for our estimates or p values for our comparisons because we included all surveillance data from Florida, not a sample. Our numbers are very large, and most of our error would be expected to be due to variations in testing and reporting of chlamydia and not due to chance. CDC staff did not have access to personal identifiers. Secondary analyses of routinely collected surveillance data do not involve human research and therefore do not require approval by the CDC Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Results

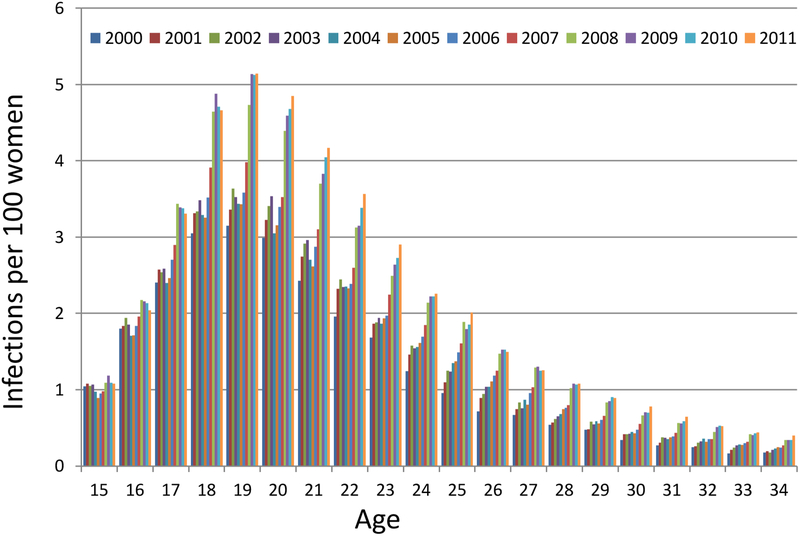

Between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2011, there were 457,595 infections reported among 15–34-year-old women living in Florida. During this time, the annual number of reported infections doubled, increasing from 25,390 to 51,536, with the biggest annual increase occurring in 2008 (7,860). After adjusting for increases in the population size, the over-all risk of reported infection increased from 1.3 infections per 100 women (1.3%) in 2000 to 2.2 infections per 100 women (2.2%) in 2011. There was a peak in the risk of reported infection at ages 18–22 (Figure 1a); that 5-year age group accounted for 52% of the reported infections for 15–34 year-olds in 2011. The highest risk was seen among 19-year-olds. The risk of reported infections for 19-year-olds increased from 3.2% in 2000 to 5.1% in 2011 (a 2011:2000 risk ratio of 1.59). The annual increase in risk of reported infections was smaller for the youngest women compared to older women. There was almost no increase in risk for 15-year-olds. The 2011:2000 risk ratio was 1.04 for 15-year-olds, 1.13 for 16-year-olds, 1.53 for 18-year-olds, and over 2.0 for women over age 24.

Figure 1 a.

Reported chlamydial infections per 100 women by age and calendar year

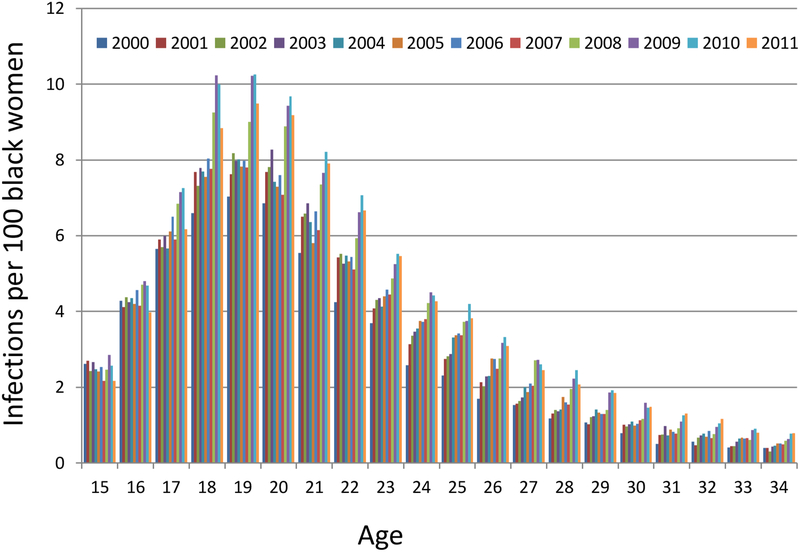

The race/ethnicity of the 457,595 cases was the following: black (46.0%), white (24.1%), Hispanic (11.1%), Asian (0.3%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (0.2%), and unknown (18.4%). Unknown race/ethnicity was less likely in 2000–2006 (13.6%) than in 2007–2011 (22.8%), was less likely when infections were diagnosed in health department clinics (13.1%) than at other sites (20.3%), and was less likely for women who had multiple infections (8.0%) than for women with one reported infection (21.9%). The annual number of reported infections per 100 black women ages 15–34 increased from 3.0 in 2000 to 4.7 in 2010 before declining slightly to 4.3 in 2011. The highest number of infections by age and race was 10.3 infections per 100 black 19-year-olds in 2010 (Figure 1b).

Figure 1 b.

Reported chlamydial infections per 100 black women by age and calendar year

The 457,595 reported infections occurred among 341,671 different women. To estimate the age at which women acquire their first reported chlamydial infection, we restricted our analysis to the first reported infection for the women in our dataset. The age distribution of first reported infections was similar to the distribution seen in Figure 1 for all reported infections, with the peak at age 19. In 2011, 3.5% of 19-year-old women were reported with what was their first chlamydial infection in the database. The risk of having a first reported chlamydial infection at a particular age was 1% or higher for women during each year of age between 15 and 25, then this risk fell below 1% per year, decreasing to 0.31% of 34-year-old women. First reported infections for black women peaked at age 18; 6.23% of all 18-year-old black women in 2011 had their first reported chlamydial infection. The annual number of black women with their first reported chlamydia infection declined from a peak of 12,745 in 2010 to 11,095 in 2011, but these numbers are influenced by the changes in availability of race information over time.

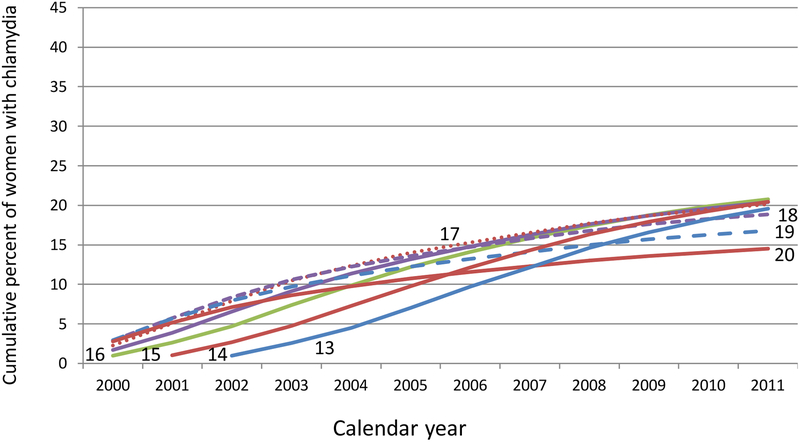

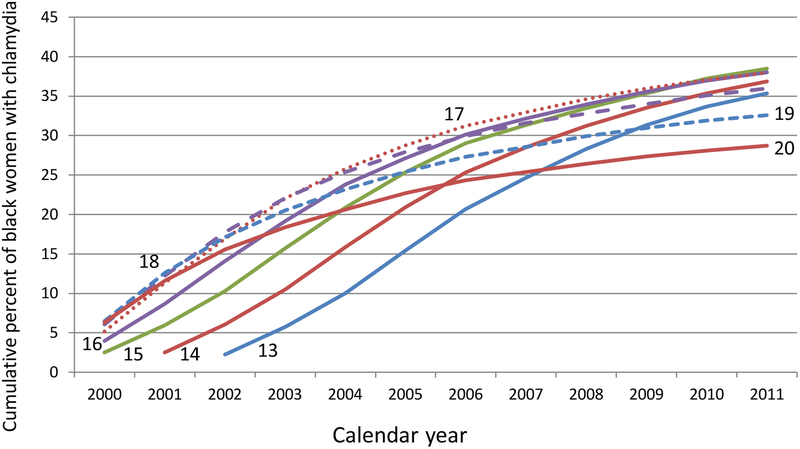

The long-term risk of having a first-reported infection was determined for individual age cohorts by accumulating the risks over the 12 years in the database. These cumulative curves reflect the influence of both age and calendar year (Figure 2a). Among women who were 14–17-years-old in 2000, over 20% had at least one reported chlamydial infection by the time they were 26–29-years-old in 2011. For black women who were ages 14–17 in 2000, over 36% had been reported with chlamydia by the time they were 26–29-years-old in 2011 (Figure 2b).

Figure 2a:

Cumulative percent of women who have been reported with chlamydia between 2000 and 2011 by age in 2000

Figure 2b:

Cumulative percent of black women who have been reported with chlamydia between 2000 and 2011 by age in 2000

Repeat infections became a higher percentage of all reported infections as the observation period covered by our database increased. In 2000, a total of 5.3% of infections were among women who had a previous infection in 2000. In 2011, a total of 33.5% of infections were reported among women who had a previous infection reported between 2000 and 2011. The percent of reported infections that were repeat infections also varied by age, and was highest for 22–26-year-olds, reaching 40% in 2011.

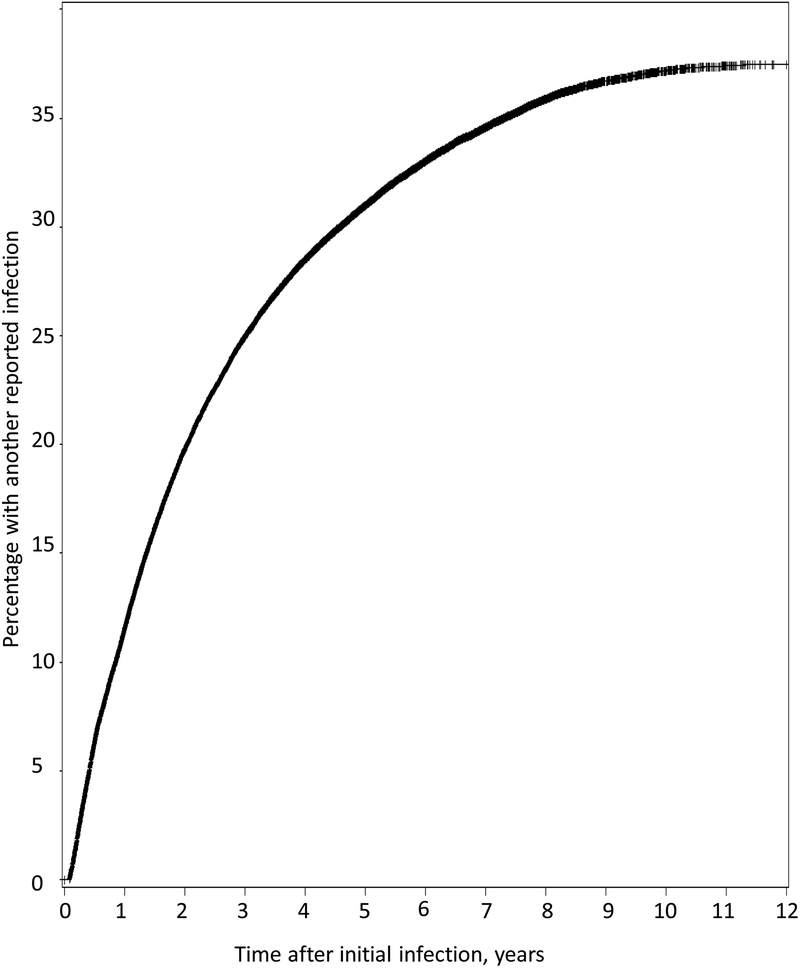

We do not know how many infected women were ever tested for reinfection, because only positive test results were reported. However, of the 341,671 women reported with chlamydia between 2000 and 2011, 115,924 had more than one reported infection. Among the 53,109 women who were reported with chlamydia in 2000–2003 when they were 15–20-years-old, 36.7% had one or more additional reported infections, 15.6% had two or more, 6.7% had three or more, 2.8% had four or more, and 1.2% had five or more reported infections by 2011. The highest number of additional reported infections was 17. The time to a second reported infection was measured for this group of 15–20-year-old women who had their first infection in 2000–2003 (Figure 3). The cumulative percentage of infected women who had another reported reinfection increased over time from 11.5% after one year to 19.8% after two years, 25.0% after three years, 28.5% after four years, 31.0% after five years, and 37.4% after eleven years.

Figure 3:

Likelihood of a second reported chlamydial infection, by time since theinitial infection, for 15–20-year-old women who were initially infected in 2000–2003

Discussion

Over 20% of all women in Florida who were between 14 and 17 years-old in 2000 had a chlamydial infection reported within 12 years. For black women, over 36% of 14–17-year-old women in 2000 were reported as having chlamydia within 12 years. The risk of reported infection was strongly influenced by age and calendar year, peaking at 5.1 infections per one hundred 19-year-olds in 2011. Women aged 18–22 years accounted for 52% of the reported infections among 15–34-year-olds in 2011. These are underestimates of the true burden of infection because they do not include infections that went undiagnosed. In Florida, the number of infections reported each year doubled between 2000 and 2011 (nationwide, the ratio was 1.8),8, 12 suggesting that many infections were undetected in the early 2000’s. Although annual screening is recommended for all sexually-active women under age 25, recent studies estimate only about 50% were tested.13

The true life-time risk of acquiring chlamydial infection is difficult to assess because there is no sensitive and specific antibody test to reliably detect past infections, (although tests under development look promising),14 and few studies have looked at the risk of chlamydial infection over time. Among 1,236 women enrolled in an HIV prevention study at STD clinics, after three follow-up visits during a period of one year, 11.9% had acquired a new chlamydial infection.15 Among 386 young women who attended primary care clinics in Indianapolis and were tested for chlamydia quarterly (and sometimes weekly) for periods of up to 8.2 years (mean 3.5 years), 10.9% were infected at baseline, another 43.5% acquired an infection during follow-up, and 45.6% remained uninfected.16 We are not aware of any previous studies that have linked surveillance records over many years to assess the cumulative risk of chlamydia in a general population.

Repeat infections were also very common in Florida. Among 15–20-year-olds first reported in 2000–2003, 37.4% had been reported with another chlamydial infection by 2011. In 2011, up to 40% of the infections reported for some age groups of women were repeat infections. These numbers underestimate the true risk of reinfection because rates of retesting are low. Retesting is recommended three months after a positive test,17 however, in one study of 36,298 women who tested positive at a large laboratory only 38% had evidence of retesting more than one year after their initial positive test.18 In other studies the risk of chlamydial reinfection has been estimated using passive follow-up among women returning for retesting, or using active follow-up over a shorter time period in order to decrease selection bias. These studies have found the risk of reinfection is very high in the short term (20% at 10 months).19 Although risk of infection persists for many years, few studies have systematically tested women to determine their risk of re-infection over a prolonged period. In a study of 14–17-year-olds who were tested quarterly (or weekly) for an average of 3.5 years, there were 478 infections among 210 study participants: 89 had one episode, 61 had two episodes, and 60 had three or more episodes.16

Trends in risk of reported infection by age showed very little increase in reported cases among 15-year-olds and 16-year-olds between 2000 and 2011, while older women had a near doubling of risk during this same period. These different trends could be due to changes in testing, or they could be due to the differences in prevalence of chlamydia in young women compared to older women. Surveys have found little change in STD-related risk behaviors among young women in high schools since 2001,20 and national chlamydia prevalence surveys show no clear differences in trends by age, suggesting that screening has increased more for older women than for 15–16-year-old women. If this is true, then this relative lack of screening would be important because test positivity18 and prevalence9 of chlamydia among sexually active young women are particularly high, and untreated infections put them at risk for PID and infertility at the very beginning of their reproductive years.

The main goal of chlamydia screening is the prevention of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and subsequent ectopic pregnancy and infertility. Identifying and treating 460,000 chlamydial infections over 12 years should have had a noticeable impact on the health of women in Florida. Monitoring PID is often challenging because the diagnosis is subjective, the causes are multifactorial, and the treatment has been shifting from hospitals to outpatient settings. Although Florida-specific PID data are not available, the data from Florida should be roughly similar to data from elsewhere in the United States. Between 1985 and 2001 hospitalizations for PID in the United States decreased by 68% while outpatient diagnoses also appeared to be decreasing.21 However, most of the PID hospitalization decrease was prior to 1995, and was, therefore, unlikely to be due to increased chlamydia screening. During the period 1995–2001 there were an estimated 769,859 cases of acute and unspecified PID diagnosed each year in the United States. In Philadelphia, PID rates have continued to decline as chlamydia screening increased, though causality for that data could not be determined based on this ecologic study.22 Two randomized controlled trials have shown that treating chlamydia reduces PID. In the most recent study, 9.5% of women with untreated chlamydia developed symptomatic PID compared to 1.6% of women with no chlamydia at baseline.4 If progression to PID was prevented for 7.9% of the 457,595 infections reported in Florida, then 36,150 cases of PID were prevented by chlamydia testing and treatment. If 9% of women with PID become infertile,3, 5, 23 then chlamydia testing and treatment preserved fertility for 3,253 women in Florida.

While the decreases in PID have been encouraging, the continued high prevalence and incidence of chlamydia has been frustrating. When the gonorrhea control program in the United States started, reported rates of N. gonorrhoeae fell 74% (from 464.1 to 121.8 per 100,000 population between 1975 and 1996).8 In contrast, reported rates of chlamydia in women have increased 61% (from 404.0 to 648.9 per 100,000 population between 2000 and 2011).8, 12 The prevalence of chlamydia in 14–25-year-old women has remained relatively stable (from 4.1% to 3.8% between 1999–2000 and 2007–2008), suggesting that the increase in the number of reported cases was due to increases in screening and the use of more sensitive tests.9 Mathematical modeling has suggested that prevalence of chlamydia among 20–24-year-old women should decrease by one-third (from 13.5% to 9.1%) over 5 years if 20% of women are screened annually, and 25% of infected women get their partners treated.24 Screening coverage has been estimated using a variety of methods. Analysis of MarketScan data from commercial health plans found a screening rate of only 13.6 per 100 women years for 15–25-year-old women in 2000–2006.25 The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), suggests a change in screening from 25.3% in 2000 to 41.6% in 2007.13 Recently, in Washington, screening coverage was estimated at 43.6% using the HEDIS measure and 57.6% using a combination approach which included other data sources.26 Thus, screening rates are increasing but the exact rates of increase are not known, and the prevalence of chlamydia is stable (or slightly decreasing) but exact rates are not known. These uncertainties complicate efforts to measure the impact of chlamydia screening, but it certainly has not had the same impact as the gonorrhea control program.

The most serious limitation for our study is that only positive test results were reported, therefore we don’t know how many women were tested or how testing rates changed. In addition, some infections that were detected were not reported, especially before electronic lab reporting was established. Race/ethnicity was missing from a large proportion of cases, but not from the census denominator, so we know that our estimates by race are underestimates. We cannot reliably adjust for missing race/ethnicity data because missing information was associated with year, provider type, and most likely with other unmeasured factors. We had data only for women who lived in Florida, and could not account for women who moved in or out of the state between 2000 and 2011. Thus, we overestimated the number of first infections and underestimated the number of repeat infections because we missed repeat (or initial) infections which were diagnosed in another state. We believe these errors are relatively small, because they only apply to women who have had infections diagnosed both in-state and out-of-state.

Our data allowed us to measure women’s risk of being reported as having chlamydia during their teenage and young-adult years. Chlamydia was reported within 12 years for over 20% of all women and over 36% of black women in Florida who were ages 15–17 in 2000. This underestimates the risk of infection for all women because many women were not screened every year and therefore many infections could resolve without being detected or reported.27 We further underestimated the risk for black women because race/ethnicity was missing for 18.4% of reported cases. The annual number of diagnoses doubled between 2000 and 2011, however, there was very little increase in diagnoses among 15–16-year-olds, even though young sexually-active women are at highest risk for chlamydial infection. Diagnosing and treating cases of chlamydia will prevent PID, but not as effectively as preventing the same number of cases of chlamydia, because some infections will progress before they can be detected.28 More information is needed on how to reduce the incidence of chlamydia.

Implications and contribution:

The cumulative risk of chlamydia is an extremely high for young women. Women who are infected once are likely to become reinfected. Diagnosing and treating infection can prevent progression to pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility. Treating partners reduces the risk of reinfection.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

No outside funding was obtained for completion of this work.

This information has not been presented at any meetings. An abstract has been submitted to the 2014 STD Prevention Conference.

References

- 1.Provisional cases of selected notifiable diseases, United States, weeks ending January 1, 2011. Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 2012;60:1764–1775. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farley TA, Cohen DA, Elkins W. Asymptomatic asexually transmitted diseases: the case for screening. Preventive Medicine 2003;36:502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haggerty CL, Gottlieb SL, Taylor BD, Low N, Xu F, Ness RB. Risk of sequelae after Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection in women. JID 210;201(Suppl 2):S134–S155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oakeshott P, Kerry S, Aghaizu A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of screening for Chlamydia trachomatis to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease: the POPI (prevention of pelvic infection) trial. BMJ 210;340:c1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westrom L, Joesoef R, Reynolds G, Hagdu A, Thompson SE. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility: a cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sex Transm Dis 1992;19:185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholes D, Stergachis A, Heidrich FE, Andrilla H, Holmes KK, Stamm WE. Prevention of pelvic inflammatory disease by screening for cervical chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1362–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preventive US Services Task Force. Screening for Chlamydial infection. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspschlm.htm Accessed on December 5, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2011 Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datta SD, Torrone E, Kruszon-Moran D, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis trends in the United States among persons 14 to 39 years of age, 1999–2008. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections Among US Women and Men: Prevalence and Incidence Estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. http://www.floridacharts.com/FLQUERY/Population/PopulationRpt.aspx.

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2000 Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed K, Scholle S, Baasiri H, et al. Chlamydia screening among sexually active young female enrollees of health plans—United States, 2000–2007. MMWR 2009;58:362–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geisler WM, Morrison SG, Doemland ML, et al. Immunoglobulin-specific responses to Chlamydia elementary bodies in individuals with and at risk for genital chlamydial infection. JID 2012;206:1836–1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterman TA, Tian LH, Metcalf CA, et al. High incidence of new sexually transmitted infections in the year following a sexually transmitted infection: a case for rescreening. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batteiger BE, Tu W, Ofner S, et al. Repeated chlamydia trachomatis genital infections in adolescent women. J Infect Dis 2010;201:42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR 2010;59(No. RR-12):46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoover KW, Tao G, Nye MB, Body BA. Suboptimal adherence to repeat testing recommendations for men and women with positive chlamydia tests in the United States, 2008–2010. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, et al. Repeat infection with chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:478–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eaton DK, Lowry R, Brener ND, Kann L, Romero L, Wechsler H. Trends in human immunodeficiency virus—and sexually transmitted diseases—related risk behaviors among U.S. high school students, 1991–2009. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutton MY, Sternberg M, Zaidi A, St. Louis ME, Markowitz LE. Trends in pelvic inflammatory disease hospital discharges and ambulatory visits, United States, 1985–2001. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:778–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anschuetz GL, Asbel L, Spain CV, et al. Association between enhanced screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae and reductions in sequelae among women. J Adolesc Health 2012;51:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ness RB, Soper DE, Holley RL, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment strategies for women with pelvic inflammatory disease: results from the Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186:929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kretzschmar M, Satterwhite C, Leichliter J, Berman S. Effects of screening and partner notification on chlamydia positivity in the United States: a modeling study. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heijne JCM, Tao G, Kent CK, Low N. Uptake of regular chlamydia testing by U.S. women: a longitudinal study. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broad JM, Manhart LE, Kerani RP, Scholes D, Hughes JP, Golden MR. Chlamydia screening coverage estimates derived using healthcare effectiveness data and information system procedures and indirect estimation may vary substantially. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:292–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geisler WM. Duration of untreated, uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection and factors associated with chlamydia resolution: a review of human studies. J Infect Dis. 2010. Jun 15;201 Suppl 2:S104–S113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price MJ, Ades AE, De Angelis D, et al. Risk of pelvic inflammatory disease following Chlamydia trachomatis infection: analysis of prospective studies with a multistate model. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]