Abstract

Background: Sexual minority women (SMW; such as lesbian, bisexual, and mostly lesbian) exhibit excess cardiometabolic risk, yet factors that contribute to cardiometabolic risk in this population are poorly understood. Trauma exposure has been posited as a contributor to cardiometabolic risk in SMW.

Materials and Methods: An analysis of data from Wave 3 of the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Study was conducted. Multinomial logistic regression was used to examine correlates of trauma. Next, multiple logistic regression was used to examine the associations of different forms of trauma throughout the life course (childhood, adulthood, and lifetime), with psychosocial and behavioral risk factors and self-reported cardiometabolic risk (obesity, hypertension, and diabetes) in SMW adjusted for relevant covariates.

Results: A total of 547 participants were included. Older age was associated with higher rates of childhood and adulthood trauma. SMW of color reported higher rates of childhood trauma than white participants. Higher education was associated with lower rates of adulthood trauma. All forms of trauma were associated with probable diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder and lower perceived social support. Adult trauma was associated with anxiety, whereas childhood and lifetime trauma were associated with higher odds of depression. No significant associations between forms of trauma and behavioral risk factors were noted, except that childhood trauma was associated with higher odds of past-3-month overeating. Logistic regression models examining the association of trauma and cardiometabolic risk revealed that childhood trauma was an independent risk factor for diabetes. Adulthood and lifetime trauma were significantly associated with obesity and hypertension.

Conclusions: Trauma emerged as an independent risk factor for cardiometabolic risk in SMW. These findings suggest that clinicians should screen for trauma as a cardiovascular risk factor in SMW, with special attention to SMW most at risk.

Keywords: sexual minority women, trauma, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Sexual minority women (SMW; e.g., lesbian, bisexual, and mostly lesbian women) report significantly higher rates of trauma (such as physical and sexual abuse) compared to their heterosexual peers.1–5 As described in the minority stress model,6 SMW are at increased risk of exposure to both general and minority stressors due to their sexual minority status. This is supported by evidence suggesting SMW experience high rates of bias-motivated violence and stigma.1,7 It is possible that the higher rates of trauma observed in SMW may be, in part, related to their sexual minority status.6,8 SMW also report higher rates of childhood emotional and sexual abuse than sexual minority men, which may heighten their risk for poor health outcomes.9

A robust body of research indicates trauma exposure is associated with risk factors for cardiovascular disease in SMW, including higher rates of poor mental health,10,11 post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),12,13 tobacco use,14,15 heavy drinking,10,16 and obesity.17–19 However, few studies have examined the cardiovascular effects of trauma in this population. In 2011, the National Academy of Medicine identified cardiovascular disease as a research priority within sexual minority health, particularly among SMW.20 A recent systematic review identified SMW reported higher rates of cardiometabolic risk factors (including poor mental health, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and obesity) relative to heterosexual women.21 In addition, SMW exhibit higher rates of hyperglycemia and elevated blood pressure compared to heterosexual women.22,23

Despite a growing understanding of the impact of trauma on the health of SMW and the increasing number of studies documenting higher cardiometabolic risk in SMW, few studies have examined associations between trauma and cardiometabolic risk in this population.21

Although there has been a substantial reduction in mortality, cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death in women24 and significant sex disparities in prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease remain.25 Psychosocial factors are recognized as contributors to cardiovascular disease development,26–28 particularly among women.29 Trauma is a potent psychosocial exposure that is considered a risk factor for poor mental health30 and women tend to report higher rates of physical and sexual abuse than men.31 Trauma has been identified as an independent risk factor for obesity,32,33 hypertension,34 and diabetes35,36 in women. In addition, trauma is strongly associated with health behaviors that can increase cardiometabolic risk, including tobacco use,37,38 heavy drinking,39–41 and disordered eating.42,43

An analysis of data from the Nurses' Health Study found that childhood physical and sexual abuse were associated with higher incidence of cardiovascular events (such as myocardial infarction and stroke) in women. However, adjustment for potential mediators, including health behaviors, explained much of this association.44 Data from several studies also indicate that there appears to be a dose–response relationship between trauma exposure and cardiometabolic risk.45–47

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine associations of different forms of trauma across the life course with self-reported cardiometabolic risk in a community-based sample of SMW. We examined demographic characteristics associated with exposure to trauma in SMW. In addition, since few studies have examined differences in cardiometabolic risk between subgroups of SMW (lesbian, bisexual, and mostly lesbian women),21 we sought to investigate sexual identity differences in cardiometabolic risk among SMW. We used data from the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women (CHLEW), a longitudinal study of the health and well-being of SMW. Given that ∼50% of CHLEW participants were added in Wave 3, we only relied on cross-sectional data from this wave for this analysis.

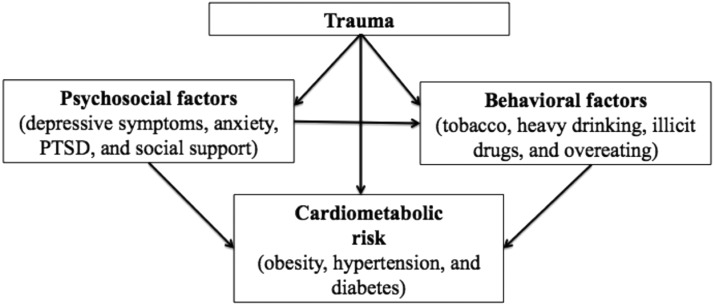

Analyses were informed by the traumatic stress model of cardiometabolic disease (Fig. 1), which posits that some individuals are more likely to experience traumatic stress, which is directly related to physiological reactivity that increases risk for poor health, including cardiometabolic risk.48 In this model, psychological (e.g., PTSD, depression, and hostility) and behavioral (e.g., tobacco use and substance abuse) risk factors are conceptualized as mediators of the association between trauma and cardiometabolic risk.48

FIG. 1.

Conceptual model of trauma and cardiometabolic risk.

Sex differences and mechanisms that link traumatic stress to increased cardiometabolic risk are not well understood.48,49 In the general population, men and women who have experienced childhood trauma have higher rates of diabetes and obesity, but women exposed to childhood trauma also report significantly higher rates of history of cardiovascular disease.45 Women with a history of childhood sexual abuse also have higher prevalence of hypertension, but this association has not been observed among men.50 Despite reporting higher rates of trauma than heterosexual women, even less is known about the association of trauma and cardiometabolic risk among SMW.21

In this sample of SMW, we hypothesized that exposure to trauma (childhood, adulthood, and cumulative lifetime trauma) would be associated with psychosocial (depressive symptoms, anxiety, PTSD, and low social support) and behavioral (tobacco use, heavy drinking, illicit drug use, and overeating) risk factors that contribute to cardiometabolic risk (self-report of obesity, hypertension and diabetes).

Materials and Methods

Sample

The CHLEW study (N = 726), funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, is an 18-year longitudinal study of risk and protective factors associated with alcohol use, health, and wellbeing of cisgender SMW.

Since 2000, three waves of data collection have been completed and a fourth wave is currently underway. CHLEW Wave 1 (2000–2001) included a convenience sample of 447 English-speaking lesbian women older than18 years, recruited from the greater Chicago metropolitan area. Detailed information about the original sample and sampling methods has been previously described.51 Wave 2 (2004–2005) followed up with 384 women (86%) of the Wave 1 cohort. CHLEW Wave 3 (2010–2012) retained 353 women (79%) from the original cohort and added a supplemental sample (N = 373) of bisexual women, younger (18–25 years), and Black and Latina women using a modified version of respondent-driven sampling (RDS).

RDS uses handpicked seeds, participants who meet study criteria, to initiate sampling chains. In this study, seeds were SMW who agreed to participate in CHLEW and to recruit other SMW from their peer networks. Participants were each given three numbered coupons to distribute to potential participants and received $20 for each eligible woman they recruited with a limit of three coupons per participant to avoid overrecruitment from a particular social network. Participants from the original cohort (Waves 1 and 2) were also asked to assist with recruitment and served as modified seeds. The modified RDS used in CHLEW Wave 3 has been described in detail elsewhere.52

Wave 1 interviews were conducted in person. In Waves 2 and 3, some interviews were conducted through Skype or telephone because several participants had moved from the Chicago area. Since CHLEW Wave 3 includes the largest and most diverse sample, we chose to conduct analyses on Wave 3 participants with complete data for measures of interest (N = 547).

Measures

Sexual identity

We assessed sexual identity using a single item. We excluded women who identified as mostly heterosexual or heterosexual (n = 14) and “other” (n = 7), as well as anyone who refused to answer this item (n = 2). Women who identified as only lesbian, bisexual, or mostly lesbian were included in this analysis.

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics included age (categorized as 18–30, 31–40, 41–50 and 51–75), race (white, Black, Latina, and other), household income (<$20,000, $20,000–39,999, $40,000–74,999, and ≥ $75,000), education (less than high school, high school, some college, college graduate, and graduate school), employment (full time, part time, unemployed-looking, and unemployed-not looking), relationship status (committed-cohabitating, committed-not cohabitating, and single), and health insurance coverage.

Lifetime trauma

We assessed childhood, adulthood, and lifetime trauma at Wave 3 based on methods previously established by the senior author of this study.53,54

Childhood trauma included physical abuse, sexual abuse, and parental neglect before the age of 18. Childhood physical abuse was assessed with the following item: “Do you feel that you were physically abused by your parents or other family members when you were growing up?” and was coded dichotomously (1 = “Yes” and 0 = “No”). Childhood sexual abuse was measured with a series of eight questions about sexual activity using established criteria.55 We then coded childhood sexual abuse as a dichotomous variable, with “1” indicating presence and “0” indicating absence of childhood sexual abuse. To assess parental neglect, participants were asked if, while they were growing up, they felt their parents neglected their basic needs (such as food, clothing, and shelter), which was coded dichotomously (1 = “Yes” and 0 = “No”).

A cumulative childhood trauma score (range 0–3) was created based on the sum of childhood physical abuse, childhood sexual abuse, and parental neglect with a score of 0 indicating no childhood trauma and 3 indicating exposure to all three forms of trauma in childhood.

Adulthood trauma included physical abuse, sexual abuse, and intimate partner violence (IPV) after the age of 18. To measure adult physical abuse, participants were asked whether someone (other than their partner) had ever attacked them with or without a weapon with the intent to kill or seriously injure them. Any participant who reported affirmatively to one or both questions was categorized as having experienced adult physical abuse (1 = “Any adult physical abuse,” 0 = “None”).

To assess adult sexual abuse, participants were asked, “since the age of 18 was there a time when you experienced any unwanted/forced sexual activity?” Responses were coded dichotomously (1 = “Yes” and 0 = “No”).

IPV was assessed by asking participants whether a partner had ever sexually assaulted them or whether a recent partner ever “threw something at you, pushed you, or hit you” or “threatened to kill you, with a weapon or in some other way?” These three forms of IPV (sexual assault, physical assault, and threat of harm) were summed and dichotomized (1 = “Any IPV” and 0 = “No IPV”).

A cumulative adulthood trauma score (range 0–3) was created based on the sum of adult physical abuse, sexual abuse, and IPV with a score of 0 indicating no adulthood trauma and 3 indicating presence of all three forms of adulthood trauma.

A cumulative lifetime trauma score (0–6) was created based on the sum of cumulative childhood and adulthood trauma. A score of 0 indicated no report of lifetime trauma, while a score of 6 indicated presence of all forms of trauma assessed.

Psychosocial risk factors

We assessed for presence and severity of depressive symptoms in the past week using the 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).56 Participants who received a score of 10 or greater on the CES-D were categorized as having probable depression. The Cronbach's alpha for the CESD-10 in this sample was 0.84. Anxiety was based on the following item: “Do you consider yourself to be a nervous or anxious person (yes or no)?” The Short Screening Scale for PTSD was used to assess PTSD.57 Participants who reported four or more PTSD symptoms were determined to meet criteria for probable PTSD diagnosis. Cronbach's alpha for the Short Screening Scale for PTSD was 0.81 in this sample.

Social support was assessed with the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), a 12-item valid and reliable measure of social support rated on a 7-point Likert scale for a total possible score of 84.58 We then divided the total score by 12 and categorized social support based on recommended cutoffs from previous work as follows: low (1.0–2.9), moderate (3.0–5.0), or high (5.1–7.0).59 Cronbach's alpha of the MSPSS was 0.90 in this sample. Given that only 13 (2.3%) participants reported low social support, we combined the categories of low and moderate (30.7%) and examined these versus high social support (66.9%) in multivariable analyses.

Behavioral risk factors

Participants were asked if they currently smoked cigarettes (1 = “Yes,” 0 = “No”). Heavy drinking was defined as binge drinking (≥5 drinks on the same occasion) on five or more days in the past month based on criteria from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (1 = “Yes,” 0 = “No”).60 Overeating was measured by asking participants whether in the past 3 months they had consumed what would be considered by others to be a large amount of food in a short period of time (such as within 2 hours) (1 = “Yes” and 0 = “No”). Participants were asked a series of questions regarding use of illicit drugs (including marijuana, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, club drugs, and injection drug use) in the past year. We created a dichotomous variable to indicate whether participants had used any illicit drugs in the past year.

Cardiometabolic risk

Body mass index (kg/m2) was calculated using self-reported weight and height. We then categorized participants as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), or obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) based on established criteria.61 We assessed whether a health care provider had ever diagnosed participants with hypertension and/or diabetes based on participant self-report.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed in Stata version 15. We conducted two sets of bivariate analyses using chi-square tests to assess sexual identity differences across study variables. Lesbian women, the largest group, were designated as the reference group for all analyses. We compared lesbian participants to bisexual and mostly lesbian women. The significance level for bivariate analyses was set at p < 0.01 to account for multiple comparisons.

Next, we used multinomial logistic regression models to estimate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association of demographic characteristics, including age (ages 18–40 vs. 41–75), race/ethnicity (reference = white), household income (reference = < $20,000), education (reference = high school education or less), employment (reference = full time), and relationship status (reference = committed-cohabitating), with trauma across the life course. For this analysis, we examined childhood (range 0–3) and adulthood trauma (range 0–3) given that we were concerned about examining lifetime trauma (range 0–6) due to small samples within each category. Models examining the association of demographic characteristics with childhood and adulthood trauma were adjusted for other demographic characteristics.

We then ran bivariate and multivariable logistic regression models to estimate ORs with 95% CI for the association of trauma across the life course with psychosocial and behavioral risk factors and cardiometabolic risk factors. Covariate adjustment was determined a priori based on previous evidence (Fig. 1).48,62,63 Due to the large sample size and small percentage of missing data, missing data were handled by listwise deletion.

Results

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics. The sample consisted of 547 SMW (lesbian = 323, bisexual = 137, and mostly lesbian = 87). Given the lack of research examining differences in cardiometabolic risk between subgroups of SMW, we compared bisexual and mostly lesbian women to lesbian women (the largest group). Lesbian and bisexual women differed on several demographic characteristics. Bisexual women were younger (p < 0.001), had lower income (p < 0.001), were more likely to be single (p < 0.001), and were less likely to be currently employed (p < 0.001) or have health insurance (p < 0.001) than lesbian women. On the other hand, we observed few demographic differences between lesbian and mostly lesbian women.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Total sample (N = 547), n (%) | Lesbian (n = 323), n (%) | Bisexuala(n = 137), n (%) | p | Mostly lesbiana(n = 87), n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age | <0.001*** | 0.18 | ||||

| 18–30 | 168 (30.7) | 75 (23.3) | 65 (47.5) | 28 (32.2) | ||

| 31–40 | 122 (22.3) | 67 (20.7) | 36 (26.2) | 19 (21.8) | ||

| 41–50 | 106 (19.4) | 67 (20.7) | 20 (14.6) | 19 (21.8) | ||

| 51–75 | 151 (27.6) | 114 (35.3) | 16 (11.7) | 21 (24.2) | ||

| Race | 0.62 | 0.27 | ||||

| White | 211 (38.6) | 123 (38.1) | 46 (33.6) | 42 (48.3) | ||

| Black | 196 (35.8) | 119 (36.8) | 54 (39.4) | 23 (26.4) | ||

| Latina | 120 (21.9) | 71 (22.0) | 30 (21.9) | 19 (21.8) | ||

| Other | 20 (3.7) | 10 (3.1) | 7 (5.1) | 3 (3.5) | ||

| Household income | <0.001*** | 0.42 | ||||

| < $20,000 | 174 (31.8) | 86 (26.6) | 68 (49.6) | 20 (23.0) | ||

| $20,000–39,999 | 112 (20.5) | 65 (20.1) | 33 (24.1) | 14 (16.1) | ||

| $40,000–74,999 | 125 (22.8) | 82 (25.4) | 22 (16.1) | 21 (24.1) | ||

| ≥ $75,000 | 136 (24.9) | 90 (27.9) | 14 (10.2) | 32 (36.8) | ||

| Education | 0.14 | 0.04 | ||||

| Less than high school | 32 (5.9) | 16 (5.0) | 14 (10.2) | 2 (2.3) | ||

| High school | 67 (12.3) | 43 (13.3) | 19 (13.8) | 5 (5.8) | ||

| Some college | 176 (32.2) | 107 (33.1) | 46 (33.6) | 23 (26.4) | ||

| College graduate | 115 (21.0) | 61 (18.9) | 29 (21.2) | 25 (28.7) | ||

| Graduate school | 157 (28.7) | 96 (29.7) | 39 (21.2) | 32 (36.8) | ||

| Employment | <0.001*** | 0.10 | ||||

| Full time | 244 (44.6) | 152 (47.0) | 45 (32.9) | 47 (54.0) | ||

| Part time | 137 (25.1) | 79 (24.5) | 34 (24.8) | 24 (27.6) | ||

| Unemployed, looking | 80 (14.6) | 40 (12.4) | 37 (27.0) | 3 (3.5) | ||

| Unemployed, not looking | 86 (15.7) | 52 (16.1) | 21 (16.3) | 13 (14.9) | ||

| Relationship status | <0.001*** | 0.56 | ||||

| Committed, cohabitating | 213 (39.0) | 141 (43.6) | 30 (21.9) | 42 (48.3) | ||

| Committed, not cohabitating | 129 (23.6) | 72 (22.3) | 42 (30.7) | 15 (17.2) | ||

| Single | 205 (37.4) | 110 (34.1) | 65 (47.4) | 30 (34.5) | ||

| Health insurance coverage | 390 (71.3) | 240 (74.3) | 83 (60.5) | <0.001*** | 67 (77.0) | 0.60 |

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||

| Possible depression | 141 (25.8) | 75 (23.2) | 51 (37.2) | <0.01* | 15 (17.2) | 0.23 |

| Anxiety | 128 (23.4) | 67 (20.7) | 38 (27.7) | 0.10 | 23 (26.4) | 0.26 |

| Probable PTSD (≥4 symptoms) | 200 (36.6) | 105 (32.5) | 67 (48.9) | <0.001* | 28 (32.1) | 0.95 |

| Perceived social support | 0.60 | 0.37 | ||||

| Low | 13 (2.4) | 11 (3.4) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Moderate | 168 (30.7) | 101 (31.3) | 44 (32.1) | 23 (26.4) | ||

| High | 366 (66.9) | 212 (65.3) | 91 (66.4) | 63 (72.4) | ||

| Behavioral factors | ||||||

| Current tobacco use | 159 (29.1) | 85 (26.3) | 51 (37.3) | 0.02 | 23 (26.4) | 0.98 |

| Heavy drinker (past month) | 29 (5.3) | 14 (4.3) | 12 (8.8) | 0.06 | 3 (3.5) | 0.71 |

| Overeating (past 3 months) | 95 (17.4) | 51 (15.8) | 28 (20.4) | 0.23 | 16 (18.4) | 0.56 |

| Illicit drug use (past year) | 210 (38.4) | 109 (33.8) | 70 (51.1) | <0.001* | 31 (35.6) | 0.74 |

| Trauma | ||||||

| Cumulative childhood trauma | 0.59 | 0.14 | ||||

| 0 | 108 (19.7) | 55 (17.0) | 30 (21.9) | 23 (26.4) | ||

| 1 | 220 (40.2) | 135 (41.8) | 57 (41.6) | 28 (32.2) | ||

| 2 | 182 (33.3) | 111 (34.4) | 43 (31.4) | 28 (32.2) | ||

| 3 | 37 (6.8) | 22 (6.8) | 7 (5.1) | 8 (9.2) | ||

| Cumulative adulthood trauma | 0.74 | 0.22 | ||||

| 0 | 209 (38.2) | 120 (37.2) | 49 (35.8) | 40 (46.0) | ||

| 1 | 171 (31.3) | 101 (31.3) | 41 (29.9) | 29 (33.3) | ||

| 2 | 114 (20.8) | 68 (21.0) | 35 (25.5) | 11 (12.6) | ||

| 3 | 53 (9.7) | 34 (10.5) | 12 (8.8) | 7 (8.1) | ||

| Cumulative lifetime trauma | 0.92 | 0.55 | ||||

| 0 | 66 (12.0) | 33 (10.2) | 17 (12.4) | 16 (18.4) | ||

| 1 | 112 (20.5) | 66 (20.4) | 27 (19.7) | 19 (21.8) | ||

| 2 | 137 (25.1) | 80 (24.8) | 38 (27.7) | 19 (21.8) | ||

| 3 | 116 (21.2) | 72 (22.3) | 27 (19.7) | 17 (19.5) | ||

| 4 | 69 (12.6) | 44 (13.6) | 16 (11.7) | 9 (10.3) | ||

| 5 | 39 (7.1) | 24 (7.4) | 9 (6.6) | 6 (6.9) | ||

| 6 | 8 (1.5) | 4 (1.2) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Cardiometabolic risk | ||||||

| Body mass index | 0.95 | 0.02 | ||||

| Underweight: ≤18.5 kg/m2 | 6 (1.1) | 4 (1.2) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Normal weight: 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 176 (32.2) | 94 (29.1) | 42 (30.7) | 40 (46.0) | ||

| Overweight: 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 153 (27.9) | 91 (28.2) | 40 (29.2) | 22 (25.3) | ||

| Obese: ≥30.0 kg/m2 | 212 (38.8) | 134 (41.5) | 53 (38.7) | 25 (28.7) | ||

| Hypertension | 97 (17.7) | 65 (20.1) | 22 (16.1) | 0.31 | 10 (11.5) | 0.07 |

| Diabetes | 46 (8.4) | 33 (10.2) | 7 (5.1) | 0.08 | 6 (6.9) | 0.35 |

Compared to lesbian women.

p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

In terms of psychosocial risk factors, bisexual women were more likely than lesbian women to meet criteria for depression (37.2% vs. 23.2%, p = 0.01) and PTSD (48.9% vs. 32.5%, p < 0.001). Bisexual women were more likely than lesbian women to report illicit drug use (51.1% vs. 33.8%, p < 0.001) in the past year. No differences in behavioral risk factors were observed between lesbian and mostly lesbian women. We did not detect any sexual identity differences in childhood, adulthood, or lifetime trauma.

Next, we examined whether demographic characteristics were associated with report of trauma (Supplementary Tables S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8). Compared to younger women (ages 18–30), participants between 41 and 75 years of age were more likely to report 2–3 forms of childhood trauma (2 forms of childhood trauma for women 41–50 adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.21, 95% CI = 1.06–4.62; 2 forms of childhood trauma for women 51–75 AOR 3.59, 95% CI = 1.68–7.71; 3 forms of childhood trauma for women 41–50 AOR 3.42, 95% CI = 1.10–10.61; and 3 forms of childhood trauma for women 51–75 AOR 3.58, 95% CI = 1.08–11.88). Likewise, participants between 31 and 75 years of age reported higher rates of all forms of adulthood trauma than younger participants.

Black women were more likely than white participants to report one to two forms of childhood trauma (one form of childhood trauma AOR 3.13, 95% CI = 1.60–6.16; and two forms of childhood trauma AOR 7.13, 95% CI = 3.52–14.47). Latinas were more likely to report two forms of childhood trauma than white women (AOR 2.79, 95% CI = 1.40–5.55). Women who identified as other race were more likely to report 1 form of childhood trauma (AOR 9.00, 95% CI = 1.13–71.91); however, as only 20 participants identified as other race the CI for this estimate was wide. No racial/ethnic differences in adulthood trauma were reported.

In terms of education, women who completed graduate school were less likely to report three forms of childhood trauma than those with a high school education or lower (AOR 0.24, 95% CI = 0.06–0.94). Women with higher levels of education were less likely to report one (some college AOR 0.43, 95% CI = 0.22–0.83; college graduate AOR 0.31, 95% CI = 0.14–0.67; graduate school AOR 0.45, 95% CI = 0.21–0.96) or two forms of adulthood trauma (some college AOR 0.33, 95% CI = 0.16–0.69; college graduate AOR 0.29, 95% CI = 0.13–0.67; graduate school AOR 0.32, 95% CI = 0.14–0.76) than those with a high school education or lower. Household income, relationship status, and employment were not associated with childhood or adulthood trauma (data not shown).

Table 2 shows associations between trauma and psychosocial and behavioral risk factors. After covariate adjustment, childhood, adulthood, and lifetime trauma were significantly associated with higher odds of probable diagnosis of PTSD and lower perceived social support. Adult trauma was also associated with higher odds of reporting anxiety (AOR 1.30, 95% CI = 1.05–1.60). In addition, experiencing more forms of childhood trauma and lifetime trauma was associated with higher odds of meeting criteria for depression. For health behaviors, childhood trauma was associated with higher odds of overeating in the past 3 months (AOR 1.44, 95% CI = 1.07–1.92). No other significant associations between trauma and behavioral risk factors were noted in adjusted analyses.

Table 2.

Associations of Trauma with Psychosocial and Behavioral Risk Factors

| Childhood trauma | Adulthood trauma | Lifetime trauma | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1, OR 95% CI | Nagelkerke, R2 | Model 2, AOR 95% CI | Nagelkerke, R2 | Model 1, OR 95% CI | Nagelkerke, R2 | Model 2, AOR 95% CI | Nagelkerke, R2 | Model 1, OR 95% CI | Nagelkerke, R2 | Model 2, AOR 95% CI | Nagelkerke, R2 | |

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||||||||

| Depression | 1.41 (1.12–1.77)* | 0.02 | 1.41 (1.11–1.81)* | 0.12 | 1.26 (1.04–1.52)* | 0.02 | 1.19 (0.97–1.46) | 0.11 | 1.24 (1.09–1.41)* | 0.03 | 1.22 (1.06–1.40)* | 0.12 |

| Anxiety | 0.95 (0.75–1.20) | 0.01 | 1.01 (0.80–1.29) | 0.09 | 1.21 (0.99–1.47) | 0.01 | 1.30 (1.05–1.60)* | 0.10 | 1.07 (0.94–1.22) | 0.01 | 1.13 (0.98–1.30) | 0.10 |

| Probable PTSD | 1.88 (1.51–2.34)* | 0.08 | 2.01 (1.59–2.53)* | 0.17 | 1.76 (1.46–2.11)* | 0.09 | 1.78 (1.46–2.16)* | 0.17 | 1.61 (1.42–1.84)* | 0.14 | 1.68 (1.46–1.94)* | 0.22 |

| High perceived social support | 0.64 (0.51–0.79)* | 0.04 | 0.68 (0.54–0.86)* | 0.13 | 0.75 (0.63–0.90)* | 0.03 | 0.82 (0.68–0.99)* | 0.12 | 0.76 (0.67–0.86)* | 0.05 | 0.80 (0.70–0.92)* | 0.13 |

| Model 1 | Model 2a | Model 1 | Model 2a | Model 1 | Model 2a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral factors | ||||||||||||

| Tobacco use | 1.05 (0.85–1.30) | 0.01 | 0.92 (0.70–1.20) | 0.27 | 1.25 (1.04–1.50)* | 0.01 | 1.18 (0.94–1.48) | 0.27 | 1.12 (0.99–1.27) | 0.02 | 1.05 (0.90–1.23) | 0.27 |

| Heavy drinking | 1.43 (0.92–2.22) | 0.01 | 1.38 (0.83–2.29) | 0.21 | 0.94 (0.64–1.38) | 0.01 | 0.78 (0.49–1.25) | 0.20 | 1.10 (0.85–1.40) | 0.01 | 1.01 (0.74–1.37) | 0.20 |

| Overeating | 1.48 (1.14–1.93)* | 0.03 | 1.44 (1.07–1.92)* | 0.10 | 1.11 (1.03–1.38)* | 0.01 | 1.09 (0.85–1.39) | 0.08 | 1.19 (1.03–1.38)* | 0.02 | 1.18 (0.99–1.40) | 0.09 |

| Illicit drug use | 1.00 (0.82–1.23) | 0.00 | 1.04 (0.82–1.31) | 0.18 | 1.02 (0.86–1.22) | 0.00 | 1.12 (0.92–1.38) | 0.18 | 1.01 (0.90–1.14) | 0.00 | 1.07 (0.93–1.23) | 0.18 |

N = 547.

Model 1 = Unadjusted.

Model 2 = Adds adjustment for demographic characteristics (sexual identity, age, race/ethnicity, household income, education, employment, relationship status, and insurance).

For behavioral factors Model 2 also adjusted for psychosocial factors (depression, anxiety, probable PTSD, and social support).

p < 0.05.

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

In multivariable analyses, bisexual women were more likely to meet criteria for probable diagnosis of PTSD compared to lesbian women even after adjusting for lifetime trauma (AOR 1.73, 95% CI = 1.08–2.77; data not shown). No sexual identity differences in additional psychosocial or behavioral risk factors were observed.

Tables 3–5 summarize results of logistic regression analyses for associations of childhood (Table 3), adulthood (Table 4), and lifetime trauma (Table 5) with cardiometabolic risk. We did not identify any sexual identity differences in the association of trauma and self-reported cardiometabolic risk (data not shown). In unadjusted analyses (Model 1), all forms of trauma were significantly associated with higher report of all cardiometabolic risk factors, with the exception of the association between adulthood trauma and diabetes (OR 1.18, 95% CI = 0.88–1.59), which was not significant. Although these associations were attenuated after adjustment for demographic characteristics (Model 2), all models remained statistically significant, except for the association between lifetime trauma and diabetes (AOR 1.20, 95% = 0.96–1.49).

Table 3.

Association of Childhood Trauma and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | AOR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | AOR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | AOR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | |

| Obesity | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.14 | ||||

| Childhood trauma | 1.40 (1.14–1.72)* | 1.27 (1.02–1.58)* | 1.17 (0.93–1.48) | 1.16 (0.93–1.47) | ||||

| Sexual identity | 0.87 (0.68–1.11) | 0.85 (0.66–1.10) | 0.86 (0.66–1.11) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | 1.28 (1.03–1.60)* | 1.28 (1.03–1.60)* | 1.29 (1.03–1.61)* | |||||

| Age | 1.30 (1.10–1.54)* | 1.33 (1.11–1.59)* | 1.28 (1.07–1.54)* | |||||

| Household income | 0.97 (0.78–1.20) | 1.00 (0.80–1.24) | 0.98 (0.78–1.23) | |||||

| Education | 0.76 (0.63–0.92)* | 0.76 (0.63–0.92)* | 0.73 (0.59–0.89)* | |||||

| Employment | 1.02 (0.85–1.23) | 0.99 (0.82–1.20) | 1.00 (0.83–1.22) | |||||

| Relationship status | 0.93 (0.74–1.17) | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.90 (0.71–1.13) | |||||

| Insurance | 0.91 (0.59–1.41) | 0.87 (0.56–1.34) | 0.86 (0.55–1.33) | |||||

| Depression | 1.31 (0.85–2.02) | 1.34 (0.86–2.09) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1.33 (0.86–2.05) | 1.33 (0.86–2.06) | ||||||

| Probably PTSD | 1.15 (0.77–1.73) | 1.15 (0.77–1.73) | ||||||

| Social support | 0.75 (0.52–1.08) | 0.76 (0.52–1.09) | ||||||

| Tobacco use | 0.72 (0.45–1.15) | |||||||

| Heavy drinking | 1.33 (0.57–3.08) | |||||||

| Illicit drug use | 0.66 (0.43–0.99) | |||||||

| Overeating | 1.29 (0.80–2.09) | |||||||

| Hypertensiona | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.32 | ||||

| Childhood trauma | 1.51 (1.16–1.96)* | 1.37 (1.02–1.83)* | 1.24 (0.92–1.69) | 1.22 (0.89–1.68) | ||||

| Sexual identity | 0.89 (0.63–1.26) | 0.86 (0.60–1.22) | 0.85 (0.59–1.23) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | 1.39 (1.03–1.88)* | 1.35 (0.99–1.84) | 1.25 (0.91–1.72) | |||||

| Age | 2.15 (1.67–2.75)* | 2.29 (1.77–2.97)* | 2.34 (1.77–3.08)* | |||||

| Household income | 0.67 (0.49–0.90)* | 0.67 (0.49–0.91)* | 0.65 (0.47–0.89)* | |||||

| Education | 0.85 (0.67–1.08) | 0.86 (0.67–1.09) | 0.97 (0.74–1.26) | |||||

| Employment | 1.13 (0.89–1.44) | 1.08 (0.84–1.38) | 1.06 (0.82–1.36) | |||||

| Relationship status | 0.89 (0.65–1.20) | 0.85 (0.62–1.17) | 0.85 (0.61–1.18) | |||||

| Insurance | 2.22 (1.20–4.13)* | 2.06 (1.10–3.85)* | 2.19 (1.16–4.14)* | |||||

| Depression | 1.07 (0.60–1.89) | 1.03 (0.57–1.86) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1.82 (0.98–3.37) | 1.64 (0.87–3.07) | ||||||

| Probably PTSD | 1.29 (0.75–2.21) | 1.28 (0.74–2.22) | ||||||

| Social support | 0.80 (0.50–1.27) | 0.83 (0.51–1.34) | ||||||

| Tobacco use | 1.13 (0.59–2.17) | |||||||

| Heavy drinking | 2.87 (1.03–7.97)* | |||||||

| Illicit drug use | 1.25 (0.70–2.22) | |||||||

| Overeating | 0.82 (0.40–1.66) | |||||||

| Obesity | 2.76 (1.63–4.68)* | |||||||

| Diabetesa | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.26 | ||||

| Childhood trauma | 1.79 (1.24–2.57)* | 1.76 (1.18–2.63)* | 1.69 (1.11–2.59)* | 1.58 (1.02–2.44)* | ||||

| Sexual identity | 0.88 (0.55–1.41) | 0.88 (0.55–1.42) | 0.90 (0.55–1.46) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | 1.51 (1.02–2.22)* | 1.45 (0.98–2.16) | 1.43 (0.95–2.15) | |||||

| Age | 1.73 (1.24–2.42)* | 1.78 (1.26–2.53)* | 1.72 (1.20–2.49)* | |||||

| Household income | 0.70 (0.47–1.04) | 0.69 (0.46–1.03) | 0.66 (0.44–0.99)* | |||||

| Education | 0.98 (0.72–1.35) | 0.98 (0.72–1.34) | 1.00 (0.72–1.42) | |||||

| Employment | 1.30 (0.95–1.79) | 1.25 (0.90–1.72) | 1.25 (0.71–1.42) | |||||

| Relationship status | 0.76 (0.50–1.15) | 0.72 (0.47–1.11) | 0.74 (0.48–1.15) | |||||

| Insurance | 4.46 (1.61–12.33)* | 4.13 (1.48–11.51)* | 4.13 (1.47–11.58)* | |||||

| Depression | 0.79 (0.36–1.72) | 0.71 (0.32–1.58) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1.64 (0.70–3.83) | 1.52 (0.65–3.56) | ||||||

| Probably PTSD | 0.89 (0.43–1.84) | 0.94 (0.45–1.96) | ||||||

| Social support | 0.67 (0.37–1.23) | 0.75 (0.40–1.40) | ||||||

| Tobacco use | 0.68 (0.28–1.70) | |||||||

| Heavy drinking | 1.19 (0.27–5.15) | |||||||

| Illicit drug use | 0.94 (0.43–2.07) | |||||||

| Overeating | 1.10 (0.45–2.71) | |||||||

| Obesity | 2.49 (1.21–5.14)* | |||||||

N = 547. Model 1 = Unadjusted; Model 2 = Adds adjustment for demographic characteristics (sexual identity, age, race/ethnicity, household income, education, employment, relationship status, and insurance); Model 3 = Adds adjustment for psychosocial (depression, anxiety, probable PTSD, and social support); Model 4 = Adds adjustment for behavioral risk factors (tobacco use, heavy drinking, overeating, and illicit drug use).

Model 4 added adjustment for obesity.

p < 0.05.

Table 5.

Association of Lifetime Trauma and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors

| Lifetime trauma | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | AOR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | AOR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | AOR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | |

| Obesity | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.15 | ||||

| Lifetime trauma | 1.28 (1.13–1.44)* | 1.19 (1.05–1.36)* | 1.15 (1.01–1.31)* | 1.16 (1.01–1.33)* | ||||

| Sexual identity | 0.87 (0.68–1.11) | 0.86 (0.67–1.10) | 0.86 (0.67–1.12) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | 1.29 (1.03–1.60)* | 1.28 (1.02–1.60)* | 1.28 (1.03–1.61)* | |||||

| Age | 1.27 (1.07–1.51)* | 1.31 (1.09–1.56)* | 1.25 (1.04–1.51)* | |||||

| Household income | 0.98 (0.79–1.21) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 0.98 (0.78–1.23) | |||||

| Education | 0.76 (0.63–0.92)* | 0.77 (0.64–0.92)* | 0.73 (0.59–0.89)* | |||||

| Employment | 1.01 (0.84–1.22) | 0.99 (0.81–1.20) | 1.00 (0.82–1.22) | |||||

| Relationship status | 0.92 (0.74–1.15) | 0.88 (0.70–1.11) | 0.89 (0.71–1.13) | |||||

| Insurance | 0.92 (0.60–1.42) | 0.87 (0.56–1.35) | 0.87 (0.56–1.35) | |||||

| Depression | 1.30 (0.84–2.01) | 1.33 (0.85–2.08) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1.31 (0.85–2.02) | 1.31 (0.83–2.03) | ||||||

| Probably PTSD | 1.09 (0.72–1.65) | 1.08 (0.71–1.63) | ||||||

| Social support | 0.75 (0.52–1.08) | 0.76 (0.53–1.10) | ||||||

| Tobacco use | 0.70 (0.44–1.12) | |||||||

| Heavy drinking | 1.37 (0.59–3.17) | |||||||

| Illicit drug use | 0.65 (0.43–0.99)* | |||||||

| Overeating | 1.28 (0.79–2.08) | |||||||

| Hypertensiona | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.33 | ||||

| Lifetime trauma | 1.44 (1.24–1.67)* | 1.31 (1.11–1.55)* | 1.24 (1.04–1.49)* | 1.22 (1.01–1.46)* | ||||

| Sexual identity | 0.89 (0.63–1.26) | 0.86 (0.61–1.23) | 0.86 (0.59–1.24) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | 1.39 (1.03–1.87)* | 1.35 (0.99–1.83) | 1.25 (0.91–1.72) | |||||

| Age | 2.09 (1.62–2.68)* | 2.22 (1.71–2.88)* | 2.27 (1.72–3.00)* | |||||

| Household income | 0.68 (0.50–0.92)* | 0.67 (0.49–0.92)* | 0.65 (0.47–0.90)* | |||||

| Education | 0.86 (0.67–1.09) | 0.86 (0.68–1.09) | 0.96 (0.73–1.25) | |||||

| Employment | 1.12 (0.87–1.42) | 1.07 (0.84–1.38) | 1.05 (0.81–1.36) | |||||

| Relationship status | 0.87 (0.64–1.19) | 0.84 (0.61–1.16) | 0.84 (0.60–1.16) | |||||

| Insurance | 2.30 (1.23–4.31)* | 2.14 (1.14–4.04)* | 2.24 (1.18–4.27)* | |||||

| Depression | 1.05 (0.59–1.86) | 1.02 (0.56–1.84) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1.75 (0.94–3.25) | 1.60 (0.65–3.01) | ||||||

| Probably PTSD | 1.16 (0.67–2.01) | 1.16 (0.66–2.04) | ||||||

| Social support | 0.80 (0.40–1.28) | 0.84 (0.52–1.37) | ||||||

| Tobacco use | 1.07 (0.56–2.06) | |||||||

| Heavy drinking | 3.06 (1.10–8.50)* | |||||||

| Illicit drug use | 1.22 (0.68–2.18) | |||||||

| Overeating | 0.80 (0.39–1.63) | |||||||

| Obesity | 2.65 (1.56–4.51)* | |||||||

| Diabetesa | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.24 | ||||

| Lifetime trauma | 1.30 (1.06–1.58)* | 1.20 (0.96–1.49) | 1.16 (0.92–1.47) | 1.12 (0.98–1.43) | ||||

| Sexual identity | 0.87 (0.54–1.39) | 0.87 (0.54–1.40) | 0.88 (0.54–1.43) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | 1.50 (1.02–2.20)* | 1.44 (0.98–2.13) | 1.43 (0.95–1.41) | |||||

| Age | 1.76 (1.26–2.45)* | 1.82 (1.28–2.57)* | 1.77 (1.23–2.54)* | |||||

| Household income | 0.71 (0.48–1.05) | 0.70 (0.47–1.05) | 0.66 (0.44–1.01) | |||||

| Education | 0.98 (0.71–1.34) | 0.97 (0.71–1.33) | 0.98 (0.69–1.39) | |||||

| Employment | 1.26 (0.92–1.73) | 1.22 (0.88–1.68) | 1.21 (0.88–1.68) | |||||

| Relationship status | 0.76 (0.50–1.16) | 0.72 (0.47–1.11) | 0.74 (0.47–1.14) | |||||

| Insurance | 4.34 (1.57–11.97)* | 4.01 (1.44–11.14)* | 4.00 (1.43–11.15)* | |||||

| Depression | 0.80 (0.37–1.73) | 0.72 (0.32–1.60) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1.72 (0.74–3.99) | 1.56 (0.67–3.64) | ||||||

| Probably PTSD | 0.97 (0.46–2.01) | 1.03 (0.49–2.17) | ||||||

| Social support | 0.65 (0.36–1.20) | 0.73 (0.39–1.38) | ||||||

| Tobacco use | 0.62 (0.25–1.53) | |||||||

| Heavy drinking | 1.35 (0.31–5.80) | |||||||

| Illicit drug use | 0.93 (0.43–2.03) | |||||||

| Overeating | 1.20 (0.49–2.90) | |||||||

| Obesity | 2.48 (1.20–5.13)* | |||||||

N = 547. Model 1 = Unadjusted; Model 2 = Adds adjustment for demographic characteristics (sexual identity, age, race/ethnicity, household income, education, employment, relationship status, and insurance); Model 3 = Adds adjustment for psychosocial (depression, anxiety, probable PTSD, and social support); Model 4 = Adds adjustment for behavioral risk factors (tobacco use, heavy drinking, overeating, and illicit drug use).

Adjusted for obesity.

p < 0.05.

Table 4.

Association of Adulthood Trauma and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors

| Adulthood trauma | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | AOR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | AOR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | AOR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke, R2 | |

| Obesity | 1.35 (1.13–1.60)* | 0.03 | 1.23 (1.03–1.48)* | 0.10 | 1.17 (0.97–1.42) | 0.13 | 1.22 (1.01–1.49)* | 0.15 |

| Adulthood trauma | 0.87 (0.68–1.12) | 0.86 (0.67–1.10) | 0.86 (0.67–1.12) | |||||

| Sexual identity | 1.30 (1.05–1.62)* | 1.29 (1.04–1.61)* | 1.29 (1.04–1.62)* | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | 1.29 (1.09–1.54)* | 1.32 (1.11–1.58)* | 1.27 (1.06–1.52)* | |||||

| Age | 0.98 (0.79–1.21) | 1.01 (0.81–1.25) | 0.98 (0.79–1.23) | |||||

| Household income | 0.75 (0.63–0.91)* | 0.75 (0.63–0.92)* | 0.72 (0.59–0.88)* | |||||

| Education | 0.99 (0.83–1.21) | 0.98 (0.81–1.18) | 0.99 (0.81–1.20) | |||||

| Employment | 0.93 (0.74–1.16) | 0.89 (0.70–1.11) | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | |||||

| Relationship status | 0.91 (0.59–1.40) | 0.86 (0.56–1.33) | 0.87 (0.55–1.33) | |||||

| Insurance | 1.32 (0.85–2.04) | 1.35 (0.86–2.10) | ||||||

| Depression | 1.31 (0.85–2.03) | 1.31 (0.84–2.04) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1.14 (0.75–1.71) | 1.12 (0.74–1.08) | ||||||

| Probably PTSD | 0.74 (0.52–1.07) | 0.75 (0.52–1.08) | ||||||

| Social support | 0.68 (0.43–1.10) | |||||||

| Tobacco use | 1.42 (0.61–3.29) | |||||||

| Heavy drinking | 0.66 (0.43–0.99)* | |||||||

| Illicit drug use | 1.31 (0.81–2.13) | |||||||

| Overeating | ||||||||

| Hypertensiona | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.33 | ||||

| Adulthood trauma | 1.64 (1.32–2.03)* | 1.42 (1.11–1.80)* | 1.33 (1.03–1.70)* | 1.30 (1.01–1.68)*a | ||||

| Sexual identity | 0.88 (0.62–1.25) | 0.85 (0.60–1.22) | 0.85 (0.59–1.23) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | 1.39 (1.03–1.88)* | 1.34 (0.99–1.82) | 1.25 (0.91–1.72) | |||||

| Age | 2.11 (1.65–2.71)* | 2.24 (1.73–2.91)* | 2.29 (1.73–3.02)* | |||||

| Household income | 0.69 (0.51–0.92)* | 0.68 (0.50–0.93)* | 0.65 (0.47–0.90)* | |||||

| Education | 0.85 (0.67–1.08) | 0.85 (0.68–1.08)* | 0.95 (0.73–1.24) | |||||

| Employment | 1.10 (0.86–1.40) | 1.06 (0.82–1.35) | 1.04 (0.80–1.34) | |||||

| Relationship status | 0.88 (0.65–1.20) | 0.84 (0.61–1.16) | 0.83 (0.60–1.16) | |||||

| Insurance | 2.28 (1.21–4.27)* | 2.13 (1.13–4.01)* | 2.24 (1.17–4.27)* | |||||

| Depression | 1.06 (0.60–1.89) | 1.03 (0.57–1.87) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1.77 (0.96–3.29) | 1.61 (0.86–3.01) | ||||||

| Probably PTSD | 1.22 (0.72–2.12) | 1.21 (0.70–2.12) | ||||||

| Social support | 0.79 (0.50–1.26) | 0.84 (0.51–1.36) | ||||||

| Tobacco use | 1.02 (0.53–1.97) | |||||||

| Heavy drinking | 3.25 (1.17–9.06)* | |||||||

| Illicit drug use | 1.22 (0.68–2.17) | |||||||

| Overeating | 0.84 (0.41–1.70) | |||||||

| Obesity | 2.68 (1.57–4.54)* | |||||||

| Diabetesa | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.24 | ||||

| Adulthood trauma | 1.18 (0.88–1.59) | 1.02 (0.74–1.40) | 0.97 (0.69–1.35) | 0.94 (0.67–1.33)a | ||||

| Sexual identity | 0.85 (0.53–1.37) | 0.86 (0.53–1.38) | 0.87 (0.53–1.41) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | 1.53 (1.04–2.44)* | 1.45 (0.98–2.14) | 1.43 (0.95–2.15) | |||||

| Age | 1.82 (1.31–2.53)* | 1.89 (1.34–2.68)* | 1.83 (1.27–2.63)* | |||||

| Household income | 0.70 (0.48–1.03) | 0.70 (0.47–1.04) | 0.66 (0.44–0.99)* | |||||

| Education | 0.96 (0.70–1.32) | 0.96 (0.71–1.32) | 0.99 (0.70–1.40) | |||||

| Employment | 1.25 (0.92–1.72) | 1.20 (0.87–1.65) | 1.20 (0.87–1.66) | |||||

| Relationship status | 0.77 (0.51–1.17) | 0.73 (0.47–1.12) | 0.74 (0.48–1.15) | |||||

| Insurance | 4.13 (1.50–11.32)* | 3.78 (1.37–10.42)* | 3.92 (1.41–10.89)* | |||||

| Depression | 0.82 (0.38–1.78) | 0.73 (0.33–1.63) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1.81 (0.78–4.20) | 1.58 (0.68–3.70) | ||||||

| Probably PTSD | 1.13 (0.55–2.32) | 1.18 (0.57–2.45) | ||||||

| Social support | 0.64 (0.35–1.17) | 0.72 (0.38–1.35) | ||||||

| Tobacco use | 0.66 (0.26–1.65) | |||||||

| Heavy drinking | 1.27 (0.30–5.51) | |||||||

| Illicit drug use | 0.96 (0.44–2.10) | |||||||

| Overeating | 1.26 (0.53–3.03) | |||||||

| Obesity | 2.66 (1.29–5.51)* | |||||||

N = 547. Model 1 = Unadjusted; Model 2 = Adds adjustment for demographic characteristics (sexual identity, age, race/ethnicity, household income, education, employment, relationship status, and insurance); Model 3 = Adds adjustment for psychosocial (depression, anxiety, probable PTSD, and social support); Model 4 = Adds adjustment for behavioral risk factors (tobacco use, heavy drinking, overeating, and illicit drug use).

Adjusted for obesity.

p < 0.05.

When we added psychosocial (Model 3) and behavioral risk factors (Model 4), the associations of childhood trauma with obesity and hypertension observed in previous models were no longer significant. However, the association of childhood trauma and diabetes remained statistically significant (AOR 1.58, 95% CI = 1.02–2.44, Table 3). Adulthood and lifetime trauma were significantly associated with higher odds of reporting obesity (adulthood trauma AOR 1.22, 95% CI = 1.01–1.49, Table 4; and lifetime trauma AOR 1.16, 95% CI = 1.01–1.33, Table 5) and hypertension (adulthood trauma AOR 1.30, 95% CI = 1.01–1.68, Table 4; lifetime trauma AOR 1.22, 95% CI = 1.01–1.46, Table 5).

Discussion

This study has several strengths. The CHLEW study provided a unique opportunity to examine associations of trauma across the life course with cardiometabolic risk in a racially diverse sample of SMW of various ages. Although a growing number of population-based surveys (e.g., National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and National Health Interview Survey) include measures of sexual identity, measures of trauma are not frequently measured. This limits the ability to use those data to examine associations of trauma and cardiometabolic risk in SMW.

Next, to our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to examine the association of trauma with hypertension and diabetes in SMW. Another strength of this study is the inclusion of SMW 18–75 years of age. As most cardiovascular research with SMW has relied on younger samples,21 this study addresses an important knowledge gap by assessing the association of trauma and cardiometabolic risk in middle-aged and older SMW.

Our findings represent an important contribution to understanding the association between trauma and cardiometabolic risk in SMW. In this study, reporting more forms of trauma throughout the life course was associated with heightened cardiometabolic risk. After covariate adjustment, childhood trauma emerged as an independent risk factor for diabetes. Adult and lifetime trauma were identified as independent risk factors for obesity and hypertension. Previous studies have found that childhood trauma, in particular sexual abuse, is associated with higher rates of obesity in SMW.17–19,64

Consistent with the traumatic stress model of cardiometabolic disease48 and previous research among women in the general population,44 we found that psychosocial and behavioral risk factors attenuated the associations between trauma and cardiometabolic risk in SMW. We were initially surprised that trauma was not significantly associated with higher report of substance use. However, longitudinal examinations of CHLEW data have found no association between trauma and smoking status in SMW.65 Although multiple studies have identified a link between trauma (particularly sexual abuse) and alcohol use in SMW,10,66,67 trauma only partially explains the higher rates of alcohol use found in this population.10,68 Given that only a small percentage of SMW in this study reported heavy drinking in the past month (5.3%), this may explain the lack of an observed association between trauma and heavy drinking.

Moreover, obesity is a multifactorial condition influenced by an interplay of genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors.69 Obesity is a significant risk factor for CVD63 that contributes to complex physiological mechanisms associated with increased prevalence of hypertension and type 2 diabetes.70,71 Previous work has found that body mass index accounts for 50% and 60% of the association between childhood trauma and hypertension and diabetes, respectively.72,73 Similarly, in this study, the associations of childhood trauma with diabetes and adulthood and lifetime trauma with hypertension were only partially explained by body mass index. Therefore, we recommend future work to incorporate prospective study designs that employ mediation analyses to further examine body mass index and hypothesized psychosocial and behavioral mediators of the association of trauma and cardiometabolic risk in SMW.

This study identified subgroups of SMW most at risk for trauma, which represents an important contribution to this nascent body of research. SMW older than 30 years generally reported higher rates of childhood and adulthood trauma than those in the youngest age group. Although these differences in report of lifetime trauma may be, in part, related to differences in acceptance of sexual minorities in society, a meta-analysis of sexual identity differences in childhood trauma found no difference in the prevalence of childhood trauma among sexual minorities over a 20-year period.3 An alternative explanation for the higher rates of adulthood trauma observed in older SMW in this sample may be that as SMW age. they accumulate greater exposure to adulthood trauma.

Furthermore, SMW of color were also more likely than white participants to report exposure to childhood trauma, which is consistent with previous research in the general population74 and among sexual minorities.9

Lower education and income may serve as both predictors75,76 and consequences of childhood trauma in the general population.77 Consistent with previous research among SMW, we found that lower education was associated with greater exposure to trauma.78 Intersectionality is one of the recommended approaches by the National Academy of Medicine for examining health disparities among sexual minorities20; however, few studies have employed an intersectional approach to examine cardiovascular health disparities among sexual minorities.21,79 An important area of research to explore is how intersecting identities impact associations of trauma and cardiometabolic risk in SMW. Furthermore, even studies in the general population rarely examine race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status as modifiers of the association of trauma and cardiometabolic risk.49

Although we did not identify differences in trauma exposure between lesbian, bisexual, and mostly lesbian women, future research is needed to understand the extent to which trauma exposure differentially impacts cardiometabolic risk in subgroups of SMW, such as SMW of color. We conducted exploratory analyses to examine the differential impact of age, race/ethnicity, household income, and education on the association of trauma and cardiometabolic risk (data not shown). Many of these results were deemed unreliable due to large standard errors, particularly for models examining diabetes. This may have been due to the low prevalence of diabetes in our sample (8.4%). Additional research with larger samples of diverse SMW is needed to better understand the impact of intersectionality on the link between trauma and cardiometabolic risk in this population.

Results indicate that bisexual women demonstrate higher rates of probable diagnosis of PTSD than lesbian women, which may predispose them to excess cardiometabolic risk as PTSD is associated with incident cardiovascular disease among women.80,81 The higher rates of PTSD among bisexual women are not surprising as in previous work they report higher rates of childhood trauma than lesbian and heterosexual women.3 Several studies have found that SMW have higher rates of PTSD than heterosexual women,12,13 but there is limited research examining disparities in PTSD diagnosis between subgroups of SMW. This is an area of research that warrants further investigation as bivariate analyses in previous studies corroborate our findings and indicate that the prevalence of PTSD is highest among bisexual women.13,82

Clinicians should be aware of the higher rates of PTSD observed in SMW, specifically bisexual women, particularly as PTSD is an identified risk factor for hypertension and cardiovascular disease among women.81,83 More research is needed that explores the differential risk for trauma and PTSD in subgroups of SMW and their associations with cardiometabolic risk.

The mounting evidence of the link between trauma and cardiometabolic risk and higher rates of trauma in SMW warrants increased recognition from clinicians. As SMW display higher risk for trauma and cardiovascular risk than heterosexual women, we recommend that clinicians routinely screen for trauma exposure and other cardiometabolic risk factors in this population. Clinicians should be informed of the unique contributions of trauma on cardiometabolic risk in SMW. There is a need for targeted training that educates clinicians about the excess cardiometabolic risk observed in SMW in epidemiological studies. As sexual identity is increasingly assessed within the electronic health record clinical settings,84,85 a crucial area to address among clinicians is how to provide culturally competent care to SMW, which acknowledges the sensitive topics of trauma and sexual identity and their potential impact on cardiometabolic risk.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although CHLEW is a longitudinal study, given that ∼50% of the sample was added in Wave 3, we only relied on cross-sectional data from this wave for this analysis. Likewise, since previous waves of the CHLEW study did not examine probable PTSD, we were unable to validate self-reports of PTSD symptoms across multiple waves. Given that previous research has found a dose-response relationship between severity of childhood trauma and cardiometabolic risk,73 there is a need to investigate whether severity, timing, and duration of trauma exposure across the life course differentially impact cardiometabolic risk in SMW. Unfortunately, we were unable to assess this in this study. Also, the timing of psychosocial and behavioral risk factors assessed varied widely.

Several recognized risk factors, including diet, physical activity, and family history of cardiovascular disease, are not included in CHLEW, which may contribute to residual confounding. The sample does not include a comparison of heterosexual women. Estimates of the association between trauma and cardiometabolic risk of women in the general population are similar to those of this study.34,44,50,72,86 Therefore, it is unknown whether the observed associations of trauma and cardiometabolic risk in SMW in this study differ from heterosexual women. This is an important area for future research as it is possible that the combined effect of sexual minority status and the exposure to minority stressors (e.g., bias-motivated discrimination, violence, and stigma) experienced by SMW may moderate the association between trauma and cardiometabolic risk in this population.

Moreover, the CHLEW study does not include biological measures of cardiometabolic risk, which is an identified limitation of previous studies.21 Relying on self-reported data to ascertain cardiometabolic risk factors might obscure differences in disease severity, especially since SMW report lower rates of health care utilization compared to heterosexual women.87–89

Conclusions

This study contributes to the nascent body of research that demonstrates trauma is associated with heightened cardiometabolic risk in SMW. This study identified subgroups of SMW most at risk for trauma. Among SMW, childhood trauma was significantly associated with higher odds of diabetes, whereas both adulthood and lifetime trauma were associated with higher odds of obesity and hypertension. We did not, however, identify significant sexual identity differences in trauma or cardiometabolic risk factors among subgroups of SMW. Implications for future research include the need to incorporate cardiovascular biomarkers, use of prospective designs, and mediation analyses in cardiovascular disease research with SMW. Our findings suggest that clinicians should screen SMW for trauma exposure as a cardiometabolic risk factor.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism under Award Number R01AA013328 to Dr. Hughes. Dr. Caceres' participation in the research was supported by a training grant on Comparative and Cost-Effectiveness Research from the National Institute of Nursing Research (T32NR014205). Dr. Veldhuis' participation in this research was made possible through an NIH/NIAAA Ruth L. Kirschstein Post-doctoral Research Fellowship (F32AA025816).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Katz-Wise SL, Hyde JS. Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analysis. J Sex Res 2012;49:142–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, Beauchaine TP. Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73:477–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, et al. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1481–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Austin SB, Jun H-J, Jackson B, et al. Disparities in child abuse victimization in lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women in the Nurses' Health Study II. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:597–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zou C, Andersen JP. Comparing the rates of early childhood victimization across sexual orientations: Heterosexual, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and mostly heterosexual. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Herek GM. Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. J Interpers Violence 2009;24:54–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspect Psychol Sci 2013;8:521–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Balsam KF, Lehavot K, Beadnell B, Circo E. Childhood abuse and mental health indicators among ethnically diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 2010;78:459–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Steffen AD, Wilsnack SC, Everett B. Lifetime victimization, hazardous drinking, and depression among heterosexual and sexual minority women. LGBT Health 2014;1:192–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC. Psychological sequelae of hate crime victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999;67:945–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith BC, Armelie AP, Boarts JM, Brazil M, Delahanty DL. PTSD, depression, and substance use in relation to suicidality risk among traumatized minority lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Arch Suicide Res 2016;20:80–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roberts AL, Austin SB, Corliss HL, Vandermorris AK, Koenen KC. Pervasive trauma exposure among US sexual orientation minority adults and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Public Health 2010;100:2433–2441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matthews AK, Cho YI, Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Aranda F, Johnson T. The effects of sexual orientation on the relationship between victimization experiences and smoking status among US women. Nicotine Tob Res 2018;20:332–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lehavot K, Simoni JM. Victimization, smoking and chronic physical health problems among sexual minority women. Ann Behav Med 2014;42:269–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction 2010;105:2130–2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aaron DJ, Hughes TL. Association of childhood sexual abuse with obesity in a community sample of lesbians. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1023–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith HA, Markovic N, Danielson ME, et al. Sexual abuse, sexual orientation, and obesity in women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:1525–1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katz-Wise SL, Jun H-J, Corliss HL, Jackson B, Haines J, Austin SB. Child abuse as a predictor of gendered sexual orientation disparities in body mass index trajectories among U.S. youth from the Growing Up Today Study. J Adolesc Health 2014;54:730–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington D.C.: Institute of Medicine, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Caceres BA, Brody A, Luscombe RE, et al. A systematic review of cardiovascular disease in sexual minorities. Am J Public Health 2017;107:e13–e21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kinsky S, Stall R, Hawk M, Markovic N. Risk of the metabolic syndrome in sexual minority women: Results from the ESTHER Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016;25:784–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Caceres BA, Brody AA, Halkitis PN, Dorsen C, Yu G, Chyun DA. Cardiovascular disease risk in sexual minority women (18–59 years old): Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2001–2012). Womens Health Issues 2018;28:333–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135:e146–e603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Kass Wenger N. Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention: What a difference a decade makes. Circulation 2011;124:2145–2154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xue Y-T, Tan Q, Li P, et al. Investigating the role of acute mental stress on endothelial dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Cardiol 2015;104:310–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosengren A, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11 119 cases and 13 648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control. Lancet 2004;364:953–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jood K, Redfors P, Rosengren A, Blomstrand C, Jern C. Self-perceived psychological stress and ischemic stroke: A case-control study. BMC Med 2009;7:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Low CA, Thurston RC, Matthews KA. Psychosocial factors in the development of heart disease in women: Current research and future directions. Psychosom Med 2010;72:842–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mandelli L, Petrelli C, Serretti A. The role of specific early trauma in adult depression: A meta-analysis of published literature. Childhood trauma and adult depression. Eur Psychiatry 2015;30:665–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hemmingsson E, Johansson K, Reynisdottir S. Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2014;15:882–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stene LE, Jacobsen GW, Dyb G, Tverdal A, Schei B. Intimate partner violence and cardiovascular risk in women: A population-based cohort study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22:250–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mason SM, Wright RJ, Hibert EN, Spiegelman D, Forman JP, Rich-Edwards JW. Intimate partner violence and incidence of hypertension in women. Ann Epidemiol 2012;22:562–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang H, Yan P, Shan Z, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 2015;64:1408–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Katz DA, Sprang G, Cooke C. The cost of chronic stress in childhood: Understanding and applying the concept of allostatic load. Psychodyn Psychiatry 2012;40:469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fu SS, McFall M, Saxon AJ, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and smoking: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res 2007;9:1071–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gallo LC, Roesch SC, Fortmann AL, et al. Associations of chronic stress burden, perceived stress, and traumatic stress with cardiovascular disease prevalence and risk factors in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychosom Med 2015;76:468–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schwandt ML, Heilig M, Hommer DW, George DT, Ramchandani VA. Childhood trauma exposure and alcohol dependence severity in adulthood: Mediation by emotional abuse severity and neuroticism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2013;37:984–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramos Z, Fortuna LR, Porche M V., et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and their relationship to drug and alcohol use in an international sample of Latino immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health 2017;19:552–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haller M, Chassin L. Risk pathways among traumatic stress, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and alcohol and drug problems: A test of four hypotheses. Psychol Addict Behav 2014;28:841–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Palmisano GL, Innamorati M, Vanderlinden J. Life adverse experiences in relation with obesity and binge eating disorder: A systematic review. J Behav Addict 2016;5:11–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Caslini M, Bartoli F, Crocamo C, Dakanalis A, Clerici M, Carrà G. Disentangling the association between child abuse and eating disorders. Psychosom Med 2016;78:79–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rich-Edwards JW, Mason S, Rexrode K, et al. Physical and sexual abuse in childhood as predictors of early-onset cardiovascular events in women. Circulation 2012;126:920–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Friedman EM, Montez JK, Sheehan CM, Guenewald TL, Seeman TE. Childhood adversities and adult cardiometabolic health: Does the quantity, timing, and type of adversity matter? J Aging Health 2015;27:1311–1338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gilbert LK, Breiding MJ, Merrick MT, et al. Childhood adversity and adult chronic disease: An update from ten states and the District of Columbia, 2010. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:345–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scott KM, Von Korff M, Angermeyer MC, et al. Association of childhood adversities and early-onset mental disorders with adult-onset chronic physical conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:838–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dedert EA, Calhoun PS, Watkins LL, Sherwood A, Beckham JC. Posttraumatic stress disorder, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease: A review of the evidence. Ann Behav Med 2010;39:61–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Suglia SF, Koenen KC, Boynton-Jarrett R, et al. Childhood and adolescent adversity and cardiometabolic outcomes: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137:e15–e28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suglia SF, Clark CJ, Boynton-Jarrett R, Kressin NR, Koenen KC. Child maltreatment and hypertension in young adulthood. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Szalacha LA, et al. Age and racial/ethnic differences in drinking and drinking-related problems in a community sample of lesbians. J Stud Alcohol 2006;67:579–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Martin K, Johnson TP, Hughes TL. Using respondent driven sampling to recruit sexual minority women. Surv Pract. 2015;8:273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hughes TL, Szalacha LA, Johnson TP, Kinnison KE, Wilsnack SC, Cho Y. Sexual victimization and hazardous drinking among heterosexual and sexual minority women. Addict Behav 2010;35:1152–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Andersen JP, Hughes TL, Zou C, Wilsnack SC. Lifetime victimization and physical health outcomes among lesbian and heterosexual women. PLoS One 2014;9:e101939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wyatt GE. The sexual abuse of Afro-American and White-American women in childhood. Child Abuse Negl 1985;9:507–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health 1993;5:179–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Breslau N, Peterson EL, Kessler RC, Schultz LR. Short screening scale for DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:908–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess 1990;55:610–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess 1988;52:30–41 [Google Scholar]

- 60. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. 2017. Available at: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking Accessed December11, 2017

- 61. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining adult overweight and obesity. 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html Accessed December28, 2017

- 62. Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2015;132:873–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137:e67–e492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wood SM, Schott W, Marshal MP, Akers AY. Disparities in body mass index trajectories from adolescence to early adulthood for sexual minority women. J Adolesc Health 2017;61:722–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Matthews AK, Riley BB, Everett B, Hughes TL, Aranda F, Johnson T. A longitudinal study of the correlates of persistent smoking among sexual minority women. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:1199–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gilmore AK, Koo KH, Nguyen H V, Granato HF, Hughes TL, Kaysen D. Sexual assault, drinking norms, and drinking behavior among a national sample of lesbian and bisexual women. Addict Behav 2014;39:630–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rhew IC, Stappenbeck CA, Bedard-Gilligan M, Hughes T, Kaysen D. Effects of sexual assault on alcohol use and consequences among young adult sexual minority women. J Consult Clin Psychol 2017;85:424–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Drabble L, Trocki KF, Hughes TL, Korcha RA, Lown AE. Sexual orientation differences in the relationship between victimization and hazardous drinking among women in the National Alcohol Survey. Psychol Addict Behav 2013;27:639–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hruby A, Hu FB. The epidemiology of obesity: A big picture. Pharmacoeconomics 2015;33:673–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Singh GM, Danaei G, Farzadfar F, et al. The age-specific quantitative effects of metabolic risk factors on cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: A pooled analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e65174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Eckel N, Meidtner K, Kalle-Uhlmann T, Stefan N, Schulze MB. Metabolically healthy obesity and cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015;23:956–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Riley EH, Wright RJ, Jun HJ, Hibert EN, Rich-Edwards JW. Hypertension in adult survivors of child abuse: Observations from the Nurses' Health Study II. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:413–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rich-Edwards JW, Spiegelman D, Lividoti Hibert EN, et al. Abuse in childhood and adolescence as a predictor of type 2 diabetes in adult women. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:529–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Roberts A, Gilman S, Breslau J, Breslau N, Koenen K. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychol Med 2011;41:71–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lefebvre R, Fallon B, Wert M Van, Filippelli J. Examining the relationship between economic hardship and child maltreatment using data from the Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2013 (OIS-2013). Behav Sci (Basel) 2017;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Halfon N, Larson K, Son J, Lu M, Bethell C. Income inequality and the differential effect of adverse childhood experiences in US children. Acad Pediatr 2017;17:S70–S78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Hinesley J, et al. Association of childhood trauma exposure With adult psychiatric disorders and functional outcomes. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e184493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Hughes TL, Benson PW. Characteristics of childhood sexual abuse in lesbians and heterosexual women. Child Abuse Negl 2012;36:260–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Caceres BA, Brody A, Chyun D. Recommendations for cardiovascular disease research with lesbian, gay and bisexual adults. J Clin Nurs 2016;25:3728–3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sumner JA, Kubzansky LD, Elkind MS V, et al. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms predict onset of cardiovascular events in women. Circulation 2015;132:251–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gilsanz P, Winning A, Koenen KC, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptom duration and remission in relation to cardiovascular disease risk among a large cohort of women. Psychol Med 2017;47:1370–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, Austin SB. Elevated risk of posttraumatic stress in sexual minority youths: Mediation by childhood abuse and gender nonconformity. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1587–1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sumner JA, Kubzansky LD, Roberts AL, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and risk of hypertension over 22 years in a large cohort of younger and middle-aged women. Psychol Med 2016;46:3105–3116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ONC fact sheet: 2015 edition Health Information Technology (Health IT) certification criteria, base electronic health record (EHR) definition, and ONC health IT certification program modifications final rule. 2015. Available at: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/factsheet_draft_2015-10-06.pdf Accessed December1, 2018 [PubMed]

- 85. Cahill S, Singal R, Grasso C, et al. Do ask, do tell: High levels of acceptability by patients of routine collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data in four diverse American community health centers. PLoS One 2014;9:e107104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mason SM, Ayour N, Canney S, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Intimate partner violence and 5-year weight change in young women: A longitudinal study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26:677–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Barkan SE, Balsam KF, Mincer SL. Disparities in health-related quality of life: A comparison of lesbians and bisexual women. Am J Public Health 2010;100:2255–2261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Koh AS. Use of preventive health behaviors by lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women: questionnaire survey. West J Med 2000;172:379–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Qureshi RI, Zha P, Kim S, et al. Health care needs and care utilization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations in New Jersey. J Homosex 2018;65:167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data