Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of neurodegenerative cognitive impairment, defined by abnormal accumulations of amyloid-β and tau. Approaches directly targeting these proteins have not resulted in a disease modifying therapy. Neurovascular unit dysfunction is a feature of AD offering an alternative target for intervention. Sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitor, improves cognitive functioning in mouse models of AD. Recent work in AD patients has demonstrated increased cerebral blood flow, as well as brain oxygen utilization after a single dose of sildenafil. Its effect on nitric oxide-cGMP signaling may have downstream effects on neuroplasticity, amyloid-β processing, and improved neurovascular unit function. Fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (fALFF) assesses spontaneous neural activity via resting state fMRI BOLD signal (0.01–0.08 or 0.10 Hz). In AD, other assessments have revealed increased fALFF in hippocampi and parahippocampal gyri. Here, we examined the effects of a single dose of sildenafil on fALFF in a cohort of 10 AD patients. We found a decrease (p < 0.03, α = 0.05) in fALFF an hour after sildenafil administration in the right hippocampus. Additionally, cerebral vascular reactivity in response to carbon dioxide inhalation, a measure of neural vascular reserve previously collected on most of these participants, was not significantly correlated with this decrease, implying that change in fALFF may not have been solely due to altered vascular reactivity to CO2. We demonstrate that in patients with AD, hippocampal fALFF decreases in response to sildenafil, suggesting a normalization. These findings support further investigation into the effects of sildenafil in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive impairment, fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations, functional magnetic resonance imaging, sildenafil

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most frequent cause of dementia in the United States, and is estimated to have a worldwide prevalence of 24 million [1]. Pathologically, it is associated with extracellular amyloid-β plaque formation, as well as hyperphosphorylation and misfolding of the tau protein causing intracellular neurofibrillary tangle accumulation [2]. It has been established that AD is also associated with cerebrovascular hemodynamic changes, including reduced cerebral blood flow (CBF), increased cerebrovascular resistance, and reduced cerebral metabolic rate [3–5]. Using a multifactorial data-driven analysis of longitudinal data from 1,171 human subjects from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Iturria-Medina et al. (2016) showed that changes in proteomically defined vascular and inflammatory factors precede changes in both cerebral amyloid-β and tau as well as cognitive deficits [6].

We previously published the effect of a single dose of sildenafil on cerebral hemodynamic function and cerebral oxygen metabolism in patients with AD [7]. We found in a group of twelve patients that a single sildenafil dose increased the following markers: global CBF as measured by phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), regional CBF in the bilateral medial temporal lobes as measured by arterial spin labeling MRI, and the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) as measured by T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging.

Ten of the previously evaluated participants also had resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) data before and an hour after sildenafil administration, and these data are the focus of the present study. The resting-state fMRI measure utilized was fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (fALFF). Amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (ALFF) in the range of 0.01–0.08 or 0.1 Hz is believed to reflect the amplitude of spontaneous neural activity in specific regions. It has the potential to generate imaging biomarkers of a disease state, and has been used to study various neurodegenerative conditions [8, 9].

Particularly, fALFF, which represents the ratio of low-frequency to the entire frequency range, is superior to ALFF at suppressing noise components, including those related to vascular flow[10]. Previous work in fALFF in AD has suggested that patients with AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) have increased fALFF in bilateral hippocampal/parahippocampal regions as compared to controls, while demonstrating decreased activity in other areas, including the posterior cingulate cortex/precuneus and inferior parietal lobe [11]. Increased ALFF has also been noted in AD patients compared to those with MCI [12]. Increased fALFF in the right parahippocampal gyrus was observed in a study comparing participants with AD to participants with MCI as well as to normal control participants. Participants with MCI had increased fALFF in this region compared to controls [13].

Here, given the previous finding of increased CBF to bilateral medial temporal lobes and the known importance of the hippocampus/medial temporal lobe formations in AD pathophysiology, we investigated whether treatment with single-dose sildenafil altered fALFF in these areas in study participants. We also examined whether there was any correlation of such changes with previously obtained cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR)-CO2 maps.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW), in accord with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Subjects

An initial total of 14 participants between 62–87 years of age were recruited from the early AD cohort of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center (ADC) at UTSW. Inclusion criteria for participants included a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 0.5 or 1 and a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of greater than or equal to 20 at the most recent ADC research visit, as well as a consensus diagnosis of AD.

Participants were excluded if there were any safety contraindications to undergoing MRI, any physiologic contraindication to receiving a PDE5 inhibitor, or if they were already taking a daily PDE5 inhibitor. If using as-needed PDE5 inhibitor (for indications such as erectile dysfunction), participants were asked to refrain from taking it 7 days prior to study procedures, although this did not apply to any of the subjects. All participants gave informed written consent prior to study participation.

We evaluated the 10 Caucasian participants with complete resting-state fMRI data, 5 male and 5 female, with dementia (Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) average score 18.2) before and after sildenafil administration to assess differences. APOE allelic status was 3/4 in 6 subjects, 3/3 in 3 subjects, and 2/4 in 1 subjects. Participants served as their own comparators. See Table 1 below for further details regarding demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics

| Participant | Age at scan (y) | Sex (M/F) | MoCA | MMSE (at recruitment) | MMSE (closer to scan time) | ApoE allele 1 | ApoE allele 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 66 | F | 24 | 26 | 27 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | 65 | M | 10 | 24 | 20 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | 68 | F | 16 | 22 | 22 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 75 | F | 20 | 21 | 21 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | 87 | M | 29 | 29 | 28 | 3 | 3 |

| 6 | 69 | F | 6 | 19 | 15 | 2 | 4 |

| 7 | 59 | M | 18 | 19 | 19 | 3 | 4 |

| 8 | 83 | M | 28 | 28 | 24 | 3 | 4 |

| 9 | 79 | F | 15 | 24 | 24 | 3 | 3 |

| 10 | 69 | M | 16 | 25 | 19 | 3 | 3 |

MoCA was obtained on the day of the experiment. There was a variable duration of months between scan time and the collection of MMSE data. MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination; ApoE, apolipoprotein E, a susceptibility gene for Alzheimer’s disease.

Procedures

Study procedures were conducted during two sessions in one study visit. Blood pressure was obtained prior to entering the MRI scanner and commencement of the first session. Experiments were conducted on a 3T MRI system (Philips Health-care, Best, The Netherlands). The body coil was used for radiofrequency transmission and a 32-channel sensitivity encoding (SENSE) head coil for receiving. Foam padding stabilized the head to minimize motion. A localizer scan was performed for slice positioning, and a coil sensitivity scan was conducted for SENSE reconstruction. A 3D T1-weighted magnetization-prepared-rapid-acquisition-of-gradient-echo (MPRAGE) scan was performed for anatomical reference and the estimation of brain volume. The MPRAGE sequence used the following imaging parameters: repetition time (TR) of 8.1 ms, echo time (TE) of 3.7 ms, flip angle of 12°, shot interval of 2100 ms, an inversion time (TI) of 1100 ms, voxel size of 1 × 1 × 1 mm3, and 160 slices with a sagittal slice orientation. The fMRI data were acquired in the transverse plane, using an EPI sequence: TR of 2 seconds, TE of 30 ms, flip angle = 80°, 37 slices/volume, 205 volumes/run, slice thickness = 4 mm with no gap, and acquisition matrix = 64 voxels × 64 voxels at 3.44 × mm × 3.44 mm. The duration of the resting state scan was 416 s.

As described in prior work, brain physiological markers were measured by advanced MRI techniques, including CBF, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) and CVR to CO2 [7]. In addition, MPRAGE and EPI data were collected as noted above. After the first session, participants were given a 50 mg, oral dose of sildenafil. An hour later, the second scan session included the same physiological marker scans as well as EPI acquisition. Blood pressure was measured again prior to the second session.

Analysis

The majority of fMRI preprocessing was accomplished via the AFNI (Software for Analysis and Visualization of Functional Magnetic Resonance Neuroimages) package [14]. fMRI data was processed twice for each subject, reflecting two separate scan sessions pre- and post-sildenafil. MPRAGE data were skull-stripped in the FreeSurfer image analysis suite, registered to the functional data for each run separately, and warped to fit the MNI template using a nonlinear warping algorithm [15]. The BOLD data from each session were slice-time and motion corrected. Motion correction was accomplished with the program 3dvolreg, via which the BOLD data was realigned to the first EPI volume. In addition, 3ddeconvolve was applied to regress out motion parameter estimates obtained from 3dvolreg from the data, further correcting for motion artifact. The data were then resampled to 2 mm isotropic voxels and warped to fit the MNI template by applying the parameters obtained from fitting the corresponding MPRAGE to the template.

Notably, all participants except one had less than 3 mm movement from baseline in any direction (x, y, or z) during the duration of the resting state scan; in the case of the one participant with greater than 3 mm, there were very few data points with increased motion, and the movement was only slightly above 3 mm. This helped to assure that head motion likely had minimal artifactual effect on results.

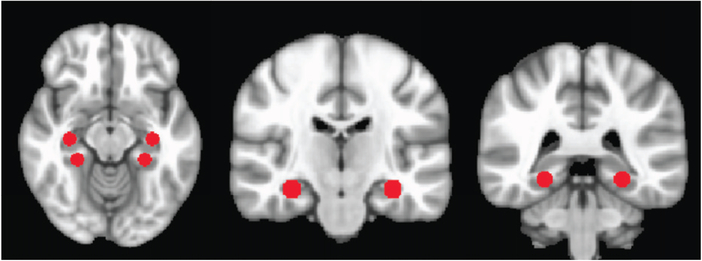

Subsequently, voxel-wise ALFF was calculated. For each voxel, linear trends were removed from the time series, which were then band-pass filtered for frequencies between 0.01–0.1 Hz. A fast Fourier transform converted data to the power spectrum and the average of the square root of the power in the spec-ified frequency was taken. This voxel wise value was divided by the brain global mean. To then calculate fALFF, the ratio of power in the low frequency range to that in the whole frequency range was obtained, then again divided by global within-brain mean. Spherical region-of-interest (ROI)-wise fALFF was obtained; literature-based MNI coordinates with radii of 6 mm were utilized to generate ROI masks for left and right hippocampus and left and right parahippocampal gyri. Please see Figure 1 for details of the spherical regions of interest.

Fig. 1.

Regions of interest delineated on MNI brain. See Table 2 for coordinates. The first image to the left depicts axially the hippocampal (paired, above) and parahippocampal (paired, below) ROIs. The second image depicts the hippocampal ROIs coronally, and the final image depicts the parahippocampal ROIs coronally.

The methods for the measurement of CBF via phase-contrast MRI for global and arterial-spin-labeling MRI for regional CBF, the T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging (TRUST) MRI technique to measure global CMRO2, as well as the obtaining of CVR by CO2 inhalation and concomitant BOLD assessment are detailed elsewhere [7].

Statistics

For fMRI data, paired two-tailed T-tests uncorrected for multiple comparisons were conducted to evaluate for statistically significant differences in fALFF for each ROI in 10 participants before and after sildenafil administration. CVR maps were available for 6 participants who also had complete fMRI data, and were masked out in relevant regions of interest for Pearson product-moment correlation with these participants’ fALFF values.

RESULTS

fALFF data

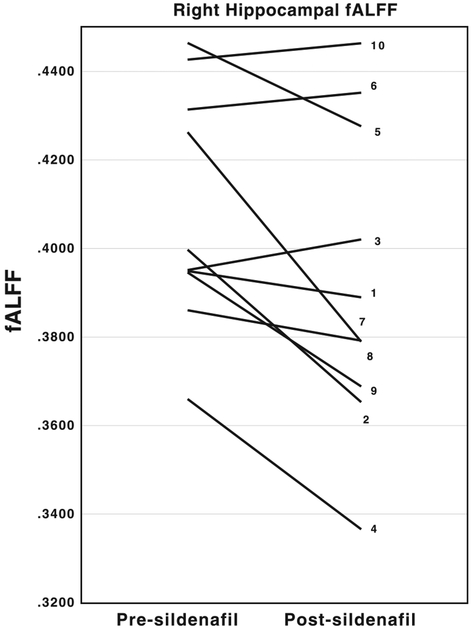

We detected a decrease in fALFF in right hippocampus (p = 0.027, α = 0.05), as well as a trend toward decrease in left parahippocampal area (p = 0.084) when comparing the regions of interest (as shown in Table 2) from the second, post-sildenafil sets of scans to the first. See Figure 2 for details of changes in right hippocampal fALFF pre- and post-sildenafil administration for each participant.

Table 2.

fALFF changes in medial temporal lobe ROIs with sildenafil administration

| Region of interest (ROI) | MNI coordinates (x, y, z) | Direction of change in present study with sildenafil | Mean fALFF before sildenafil (standard deviation) | Mean fALFF after sildenafil (standard deviation) | T-test value (dF9) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R hippocampus | 32, −20, −16 [33] | Decreased | 0.408 (0.027) | 0.392 (0.035) | 2.638 | 0.027 |

| L hippocampus | −32, −20, −16 | No clear trend | 0.387 (0.020) | 0.386 (0.034) | 0.158 | 0.878 |

| R parahippocampal area | 26, −36, −10 [34] | Decreased | 0.405 (0.013) | 0.387 (0.028) | 1.652 | 0.133 |

| L parahippocampal area | −26, −36, −10 | Decreased | 0.398 (0.022) | 0.378 (0.025) | 1.942 | 0.084 |

Fig. 2.

Spaghetti plots depicting the decrease in right hippocampal fALFF by subject. The vertical axis corresponds to fALFF values. The left end of each line represents pre-sildenafil fALFF values while the right end represents post-sildenafil fALFF values. The numbers associated with each line correspond to the participant numbers in Table 1.

See Table 2 below for further details of our findings.

CVR correlations

We looked to see if CVR-CO2 changes explained our fALFF findings in the subset of patients in which both data were available (n = 6). We found no correlation between the fALFF change in either the right (R = 0.42, p = 0.40) or left (R = 0.02, p = 0.97) hippocampi and the CVR-CO2 change in these same regions in the 0.02–0.04 Hz range, suggesting independence of the two findings.

Neuropsychological measures

No correlation was found between MoCA or MMSE scores and fALFF changes. We did not repeat neuropsychological testing in the same day after sildenafil administration given concerns about testing validity being affected by repetition in a short time span.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the impact of a 50 mg dose of sildenafil on resting state fMRI measures of regional low frequency fluctuations. The major focus of this work was examination of the impact of sildenafil on hippocampal formations, in further exploration of our previous findings. While in the literature, fALFF has been reported to be both increased and decreased in AD/MCI patients compared to controls in different regions, fALFF in hippocampi and parahippocampal formations are consistently reported as increased in AD/MCI [11]. In a model of limbic regions including bilateral hippocampi/parahippocampi, amygdalae, and cingulum, increased inhibitory activity was linked with better cognition [16]. Here, sildenafil administration was associated with normalization of this change. We found that fALFF was significantly decreased in the right hippocampus of early AD patients after sildenafil compared to pre-treatment measures in these subjects, indicating at least partial normalization of right hippocampal fALFF based on increased fALFF in AD/MCI patients. Sildenafil administration was also correlated as a trend, in this small group, with a similar realignment of fALFF along the lines of those previously noted in AD/MCI patients in the parahippocampal regions. In previous work published on this same cohort, we had reported CVR-CO2 to be focally reduced in some areas with a trend for reduction globally. Because CMRO2 changes necessarily reflect whole-brain changes rather than alterations within specific regions of interest, we chose to look at fALFF in the regions of increased CBF for a regional measure of physiologic change after sildenafil. Given the lack of significant correlation between region of interest CVR-CO2 and fALFF changes following sildenafil, it does not appear that a reduction in CVRCO2 explains the reduction in fALFF that we report, and it is possible that the reduction also relates to changes in O2 consumption.

While patients with AD have been extensively studied for other resting state fMRI connectivity characteristics relating to coherence between regions, fALFF as a specific measure is less well studied in this disorder. In general, AD/amnestic MCI is associated with default mode network dysfunction, in regions including precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and medial temporal lobe. More specifically, decreased connectivity has been observed between PCC and other brain regions, including occipital and temporal, and increased connectivity between PCC and parietal regions, the latter thought to be compensatory [17]. fALFF adds to previous literature in that it represents a method of investigating low-frequency oscillations specific to a particular region. It is thought to represent spontaneous neural activity in a region of interest, expanding on previous work related to connectivity between regions. Resting-state fMRI is a popular method of probing neural connectivity between regions characteristics in various neurologic and psychiatric disorders because of its lack of reliance on task performance, as well as its noninvasive nature.

As noted previously, several studies have found increased fALFF in medial temporal lobe regions in AD [11–13]. Others have noted globally decreased functional characteristics in AD cohorts, including in temporal lobe areas [18]. It is possible that these discrepancies are affected by different aspects of neural compensation. We here demonstrate that in the acute period, PDE5 inhibitor administration may alter fALFF characteristics in a small AD sample. The decrease in fALFF from baseline associated with sildenafil dosing may indicate a decrease in spontaneous neural activity. Because increased fALFF was previously found in those areas in AD/MCI patients, the implication is that our findings may be due to a decrease in aberrant activity, or to a redistribution of neural resources. Similar results were noted in a study of 14 patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy in comparison to healthy controls: increased fALFF in temporal areas in minimal hepatic encephalopathy patients compared to healthy controls but decreased fALFF in frontal areas, with the increase thought to represent compensation related to the disease state [19]. Our results imply that fALFF temporal alterations in AD/MCI may represent a biomarker network of importance, but also that sildenafil is potentially associated with a reversal of pathologic changes. A larger sample size, as well as investigation over a longer period of chronic administration, will be needed in the future to assess if these findings have clinical implications for patients with amnestic MCI/AD. It is notable that in other pathologies, fALFF has been shown to correlate with task performance; for example, with language lateralization for pre-surgical planning in epilepsy as an alternative to task-based fMRI. This demonstrates an avenue to further our understanding of pathology in AD/amnestic MCI, in which participants may find task performance difficult [20].

Biochemically, sildenafil may alter AD pathology in various ways. A sizeable literature has developed around the concept of neurovascular unit dysfunction in AD, specifically implicating the brain capillaries as well as associated neurons and astrocytes [21, 22]. Dysfunction of the neurovascular unit can relate to impaired neurovascular coupling in which local blood flow does not match neuronal demands, creating relative hypoxic/ischemic conditions. Neurovascular unit dysfunction can also be caused by impaired blood-brain barrier function, disrupting cellular barriers to bulk flow diffusion and also disrupting various forms of facilitated and active transport of substances both into and out of the brain. Both types of dysfunction have been implicated in AD pathogenesis [23]. When administered in a sustained fashion, PDE5 inhibitors can reverse peripheral vascular endothelial dysfunction in both animal models and in humans [24, 25]. While acutely, PDE5 inhibitor administration amplifies downstream NO signaling, sustained administration has been shown to result in vascular antioxidant effects, increased NO release via upregulation of eNOS expression and restoration of normal vascular superoxide release [25]. Direct links between sildenafil administration and repair of blood-brain barrier function have not been established, but in a streptozotocin diabetic rat model that focused on non-cerebral vessels, sildenafil improved endothelial function and resulted in a reduction of MMP-9, an enzyme that is strongly implicated in blood-brain barrier disruption [26].

The observations of reduced oxidative stress and normalization of NO signaling offer a plausible account of how sildenafil may lead to improved endothelial function separate from its immediate effects. In addition to potentially addressing neurovascular unit dysfunction in AD, sildenafil may also have other direct, non-vascular mechanisms to improve AD in a disease modifying manner. For example, in this study, we found that fALFF was not significantly correlated with directly measured CVR changes in the right hippocampus even though the range in which CVR-CO2 may be estimated from resting state data (0.02–0.04 Hz) partially overlaps with the broader range that we sampled [27]. This implies that the observed changes may have causes beyond vascular reactivity. It is notable that PDE5 inhibitors may provide symptomatic benefit for memory given the role of NO-cGMP-PKG pathway signaling in presynaptic changes induced by LTP, constituting a non-vascular mechanism for improved memory phenotype [28, 29–31]. Further examination of the effects of chronic sildenafil treatment on clinical and imaging parameters of normalization in AD/MCI is needed.

Limitations in this work include small subject number, solely Caucasian race of participants, and single dose administration of sildenafil, which did not provide us the opportunity to investigate the impact of chronic sildenafil administration in a diverse clinical population. As the experiment occurred on a single day, before and after sildenafil cognitive testing would have been complicated by practice and placebo effects, so was not obtained. The duration of the resting state scan was additionally shorter than 10 minutes.

Disease-modifying therapy is a critical need in AD. PDE5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil, offer promise in this regard. It is worth noting that the side effect profile of sildenafil is well understood and likely tolerable in an elderly population [32]. This study provides additional analyses of the first exploration of the effects of sildenafil in humans with AD as the first steps in translating previous, promising pre-clinical studies into a possible human application. Here, we see that decreased fALFF in the hippocampus after sildenafil administration may represent a normalization of fALFF values in patients with neurodegenerative cognitive impairment related to AD. Further investigation is needed to confirm that cognitive improvement can be affected by chronic sildenafil administration in humans with AD, as well as examination of the molecular basis for such improvement given multiple potential disease modifying vascular and non-vascular mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this research was provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH) P30 AG012300, NIH R01 MH084021, NIH R01 NS067015, NIH R01 AG042753, and NIH R21 NS078656.

We thank Dr. Samarpita Sengupta for editorial assistance in preparing and submitting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/19-0128r1).

REFERENCES

- [1].Reitz C, Mayeux R (2014) Alzheimer disease: Epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, risk factors and biomarkers. Biochem Pharmacol 88, 640–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rosén C, Hansson O, Blennow K, Zetterberg H (2013) Fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease – current concepts. Mol Neurodegener 8, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Johnson NA, Jahng GH, Weiner MW, Miller BL, Chui HC, Jagust WJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Schuff N (2005) Pattern of cerebral hypoperfusion in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment measured with arterial spin-labeling MR imaging: Initial experience. Radiology 234, 851–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yezhuvath US, Uh J, Cheng Y, Martin-Cook K, Weiner M, Diaz-Arrastia R, van Osch M, Lu H (2012) Forebrain-dominant deficit in cerebrovascular reactivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 33, 75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thomas BP, Sheng M, Tseng BY, Tarumi T, Martin-Cook K, Womack KB, Cullum MC, Levine BD, Zhang R, Lu H (2017) Reduced global brain metabolism but maintained vascular function in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 37, 1508–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Iturria-Medina Y, Sotero RC, Toussaint PJ, Mateos-Perez JM, Evans AC (2016) Early role of vascular dysregulation on late-onset Alzheimer’s disease based on multifactorial data-driven analysis. Nat Commun 7, 11934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sheng M, Lu H, Liu P, Li Y, Ravi H, Peng SL, Diaz-Arrastia R, Devous MD, Womack KB (2017) Sildenafil improves vascular and metabolic function in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 60, 1351–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Egorova N, Veldsman M, Cumming T, Brodtmann A (2017) Fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF) in post-stroke depression. Neuroimage Clin 16, 116–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zuo XN, Di Martino A, Kelly C, Shehzad ZE, Gee DG, Klein DF, Castellanos FX, Biswal BB, Milham MP (2010) The oscillating brain: Complex and reliable. Neuroimage 49, 1432–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zou QH, Zhu CZ, Yang Y, Zuo XN, Long XY, Cao QJ, Wang YF, Zang YF (2008) An improved approach to detection of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) for resting-state fMRI: Fractional ALFF. J Neurosci Methods 172, 137–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Liu X, Wang S, Zhang X, Wang Z, Tian X, He Y (2014) Abnormal amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations of intrinsic brain activity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 40, 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wang Z, Yan C, Zhao C, Qi Z, Zhou W, Lu J, He Y, Li K (2011) Spatial patterns of intrinsic brain activity in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: A resting-state functional MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 32, 1720–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liang P, Xiang J, Liang H, Qi Z, Li K, Alzheimer’s Disease NeuroImaging Initiative (2014) Altered amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in early and late mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 11, 389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cox RW (1996) AFNI: Software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res 29, 162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fischl B, Dale AM (2000) Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 11050–11055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zimmermann J, Perry A, Breakspear M, Schirner M, Sachdev P, Wen W, Kochan N, Mapstone M, Ritter P, McIntosh AR, Solodkin A (2018) Differentiation of Alzheimer’s disease based on local and global parameters in personalized Virtual Brain models. Neuroimage Clin 19, 240–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhang HY, Wang SJ, Xing J, Liu B, Ma ZL, Yang M, Zhang ZJ, Teng GJ (2009) Detection of PCC functional connectivity characteristics in resting-state fMRI in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res 197, 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cha J, Hwang JM, Jo HJ, Seo SW, Na DL, Lee JM (2015) Assessment of functional characteristics of amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease using various methods of resting-state fMRI analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015, 907464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhong WJ, Zhou ZM, Zhao JN, Wu W, Guo DJ (2016) Abnormal spontaneous brain activity in minimal hepatic encephalopathy: Resting-state fMRI study. Diagn Interv Radiol 22, 196–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Smitha KA, Arun KM, Rajesh PG, Thomas B, Kesavadas C (2017) Resting-state seed-based analysis: An alternative to task-based language fMRI and its laterality index. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 38, 1187–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pardridge WM (2015) Targeted delivery of protein and gene medicines through the blood-brain barrier. Clin Pharmacol Ther 97, 347–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kisler K, Nelson AR, Montagne A, Zlokovic BV (2017) Cerebral blood flow regulation and neurovascular dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 18, 419–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yamazaki Y, Kanekiyo T (2017) Blood-brain barrier dys-function and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci 18, E1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Behr-Roussel D, Oudot A, Caisey S, Coz OL, Gorny D, Bernabe J, Wayman C, Alexandre L, Giuliano FA (2008) Daily treatment with sildenafil reverses endothelial dys-function and oxidative stress in an animal model of insulin resistance. Eur Urol 53, 1272–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Oudot A, Behr-Roussel D, Le Coz O, Poirier S, Bernabe J, Alexandre L, Giuliano F (2010) How does chronic sildenafil prevent vascular oxidative stress in insulin-resistant rats? J Sex Med 7, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Luo L, Dai DZ, Cheng YS, Zhang Q, Yuan WJ, Dai Y (2011) Sildenafil improves diabetic vascular activity through suppressing endothelin receptor A, iNOS and NADPH oxidase which is comparable with the endothelin receptor antagonist CPU0213 in STZ-injected rats. J Pharm Pharmacol 63, 943–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu P, Li Y, Pinho M, Park DC, Welch BG, Lu H (2017) Cerebrovascular reactivity mapping without gas challenges. Neuroimage 146, 320–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhang J, Guo J, Zhao X, Chen Z, Wang G, Liu A, Wang Q, Zhou W, Xu Y, Wang C (2013) Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor sildenafil prevents neuroinflammation, lowers beta-amyloid levels and improves cognitive performance in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Behav Brain Res 250, 230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].García-Osta A, Cuadrado-Tejedor M, García-Barroso C, Oyarzábal J, Franco R (2012) Phosphodiesterases as therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem Neurosci 3, 832–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Prickaerts J, Sik A, van der Staay FJ, de Vente J, Blok-land A (2005) Dissociable effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors on object recognition memory: Acquisition versus consolidation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 177, 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Prickaerts J, Sik A, van Staveren WC, Koopmans G, Stein-busch HW, van der Staay FJ, de Vente J, Blokland A (2004) Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition improves early memory consolidation of object information. Neurochem Int 45, 915–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Muller A, Smith L, Parker M, Mulhall JP (2007) Analysis of the efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in the geriatric population. BJU Int 100, 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hayes SM, Salat DH, Verfaellie M (2012) Default network connectivity in medial temporal lobe amnesia. J Neurosci 32, 14622–14629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Groen G, Sokolov AN, Jonas C, Roebling R, Spitzer M (2011) Increased resting-state perfusion after repeated encoding is related to later retrieval of declarative associative memories. PLoS One 6, e19985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]