Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is a human bacterial pathogen that disseminates through host tissues using a process called cell-to-cell spread. This critical yet understudied virulence strategy resembles a vesicular form of intercellular trafficking that allows L. monocytogenes to move between host cells without escaping the cell. Interestingly, eukaryotic cells can also directly exchange cellular components via intercellular communication pathways (e.g., trans-endocytosis) using cell–cell adhesion, membrane trafficking, and membrane remodeling proteins. Therefore, we hypothesized that L. monocytogenes would hijack these types of host proteins during spread. Using a focused RNA interference screen, we identified 22 host genes that are important for L. monocytogenes spread. We then found that caveolins (CAV1 and CAV2) and the membrane sculpting F-BAR protein PACSIN2 promote L. monocytogenes protrusion engulfment during spread, and that PACSIN2 specifically localizes to protrusions. Overall, our study demonstrates that host intercellular communication pathways may be coopted during bacterial spread and that specific trafficking and membrane remodeling proteins promote bacterial protrusion resolution.

INTRODUCTION

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive food-borne bacterium that causes listeriosis in humans (Radoshevich and Cossart, 2018). In some patients, complications such as meningitis or spontaneous abortions can occur because L. monocytogenes can infect many different cell types. A key to its pathogenesis is its ability to invade host cells and disseminate through tissues using a process called cell-to-cell spread. Cell-to-cell spread uses a vesicular-mediated form of trafficking between host cells that allows L. monocytogenes to maintain access to cytosolic nutrients while also hiding from the humoral immune response (Lamason and Welch, 2016; Weddle and Agaisse, 2018). Although much of the invasion process has been explored extensively (Radoshevich and Cossart, 2018), less is known about the molecular details of cell-to-cell spread.

To initiate spread, L. monocytogenes hijacks the host actin cytoskeleton to polymerize actin tails on the bacterial surface to promote cytosolic motility (Tilney and Portnoy, 1989; Welch et al., 1997). Once motile, it travels to the cell–cell junction and pushes a double-membrane protrusion from the donor cell into the recipient cell. This protrusion is engulfed into a double-membrane vacuole, through unknown mechanisms, followed by rupture of the vacuole and bacterial escape into the recipient cell cytosol (Tilney and Portnoy, 1989; Robbins et al., 1999; Lamason et al., 2016). Early work suggested that spreading bacteria coopted host pathways for efficient protrusion engulfment (Monack and Theriot, 2001); however, the identity of these factors has not been thoroughly investigated.

Bacterial cell-to-cell spread resembles processes that occur in uninfected cells such as trans-endocytosis in which adjacent cells exchange cytoplasm-containing vesicular compartments with their neighbors. The details of this type of intercellular communication are still largely unknown, but factors important for adhesion (e.g., cadherin), signaling (e.g., Eph receptors), endocytosis (e.g., clathrin), and exocytosis (e.g., endosomal sorting complexes required for transport [ESCRT] machinery) have been implicated (Marston et al., 2003; Piehl et al., 2007; Sakurai et al., 2014; Gong et al., 2016). Because bacterial cell-to-cell spread mimics trans-endocytosis, we hypothesized that L. monocytogenes hijacks host proteins required for cell–cell adhesion, membrane trafficking, and membrane remodeling to promote spread.

In this study, we tested this hypothesis by conducting a RNA interference (RNAi) screen that targeted 115 host genes and compared the requirements for these factors during L. monocytogenes spread. We discovered that 22 host genes are important for spread. We further showed that loss of the endocytic proteins caveolin 1 and caveolin 2 or the membrane sculpting F-BAR protein PACSIN2 impaired L. monocytogenes protrusion engulfment. We also observed localization of PACSIN2 to L. monocytogenes protrusions and demonstrated that PACSIN2 function is required in the recipient cell. Overall, our study shows that trafficking and membrane remodeling pathways are required for efficient bacterial spread and reveals PACSIN2 as a key molecular player in this process. Our approach also highlights how investigating the mechanisms of bacterial spread may reveal fundamental insights into the regulation of host intercellular communication.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RNAi screen reveals host genes that regulate bacterial cell-to-cell spread

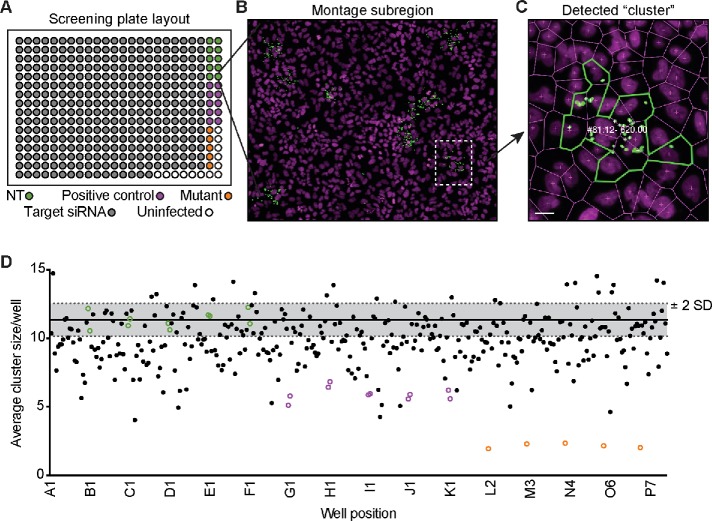

Eukaryotic cells exchange membrane-bound cytoplasmic material with their neighbors using intercellular communication processes such as trans-endocytosis (Rechavi et al., 2009). L. monocytogenes spreads through host cells by inducing double-membrane protrusions that are engulfed by the recipient cell (Lamason and Welch, 2016; Weddle and Agaisse, 2018). Therefore, we predicted that intercellular communication pathways, like trans-endocytosis, are hijacked to promote bacterial spread. To test this, we performed an RNAi screen targeting 115 genes implicated in adhesion, membrane remodeling, and endocytosis. A549 cells served as the screening platform because they are efficiently transfected, form flat monolayers, and are easily infected by L. monocytogenes (Lamason et al., 2016). Each screening plate contained 10 replicates of negative control small interfering RNAs (siRNAs; nontarget [NT]) and positive control siRNAs (Figure 1, A and D). An siRNA targeting ARPC4 (an Arp2/3 complex subunit) served as a positive control (Figure 1D) because silencing its expression impairs actin-based motility and spread (Chong et al., 2009; Talman et al., 2014). We also compared the RNAi-mediated spread defect to the L. monocytogenes ΔactA mutant, which is completely unable to spread due to a loss of actin-based motility (Figure 1D; Domann et al., 1992; Kocks et al., 1992).

FIGURE 1:

Primary RNAi screen reveals host genes that alter bacterial spread. (A) Screen plate layout with target siRNAs (gray circles), nontarget siRNAs (NT; green circles), positive control siRNAs (purple circles), or with the L. monocytogenes ΔactA mutant (orange circles). (B) Region of the full montage from the screen is shown with bacteria (green) and host nuclei (magenta). Region of interest (white dotted line) expanded in C. (C) Example of a detected cluster (infectious focus) from the screen with the numbers representing “cluster #: infected cells – cumulative GFP signal.” Scale bar = 5 μm. (D) Example run from the primary RNAi screen. NT (green circles), positive controls (purple circles), and the ΔactA mutant (orange circles) are shown along with screen siRNAs (black dots). Gray shaded region represents ±2 SD from the average cluster size (solid black line) of the 10 NT control wells.

To measure spread, A549 cells were infected with a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) of GFP-expressing bacteria (LmGFP), and after 1 h of invasion, extracellular bacteria were washed away and killed with gentamicin to allow foci of infection to form. Infected samples were fixed and stained to detect host nuclei and bacteria, and an image analysis pipeline was used to quantify the number of infected cells per focus and the number of foci per well (Figure 1, B and C, and Supplemental Table S1). To measure spread efficiency in each well, we averaged the number of infected cells per focus and plotted those values for each screening run (Figure 1D and Supplemental Table S1). Primary screen hits were selected if at least two siRNAs/gene showed a ±2 SD effect, relative to the negative control, across two biological replicates (Supplemental Table S1). We found that silencing 29 genes reduced L. monocytogenes focus size, and only one (VPS24) increased focus size. The remaining genes, including CLTC (clathrin heavy chain) and EZR (membrane–cytoskeletal linker ezrin), did not affect cell-to-cell spread in our screen (Table 1 and Supplemental Table S1). The absence of ezrin from our list of hits was surprising because it is recruited to L. monocytogenes protrusions. However, previous work showed that spread defects were only revealed after silencing all three linker family members: ezrin, radixin, and moesin (Pust et al., 2005).

TABLE 1:

Combined results from the primary and secondary RNAi screens.

| 2o screen results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1o screen hits | Gene symbol | siRNA IDs | % actin tails | % confluency | |

| Caveolin 1 | CAV1 | s2447 | s2448 | + | + |

| Caveolin 2 | CAV2 | s2451 | s2449 | + | + |

| Pacsin2 | PACSIN2 | s229822 | s22215 | + | + |

| Rac1 | RAC1 | s11712 | s11713 | + | + |

| Flotillin 1 | FLOT1 | s19915 | s19914 | + | + |

| Beta-arrestin 1 | ARRB1 | s1622 | s1623 | + | + |

| Tspan30 | CD63 | s2699 | s2700 | + | + |

| E-cadherin | CDH1 | s2768 | s2769 | + | + |

| p120 catenin | CTNND1 | s3725 | s3727 | + | + |

| Gamma-catenin | JUP | s7668 | s7666 | + | + |

| Desmocollin-2 | DSC2 | s4311 | s4310 | + | + |

| Ephrin-A2 | EFNA2 | s194390 | s4500 | + | + |

| Ephrin-A3 | EFNA3 | s4502 | s4503 | + | + |

| Ephrin type B receptor 2 | EPHB2 | s4742 | s4741 | + | + |

| Connexin 30.3 | GJB4 | s43186 | s43185 | + | + |

| Connexin 46 | GJA3 | s5762 | s5760 | + | + |

| ZO-1 | TJP1 | s14155 | s14157 | + | + |

| Claudin-6 | CLDN6 | s17309 | s17310 | + | + |

| Fes | FES | s5114 | s5113 | + | + |

| Tuba | DNMBP | s23437 | s23439 | + | + |

| srGAP2 | SRGAP2 | s23692 | s23691 | + | + |

| CHMP3a | VPS24 | s28474 | s28473 | + | + |

| Alpha-catenin 2 | CTNNA2 | s3719 | s3721 | + | − |

| CapZB | CAPZB | s2402 | s2401 | − | + |

| Cdc42 | CDC42 | s2767 | s2766 | + | − |

| hVps28 | VPS28 | s27578 | s27579 | + | − |

| JAM-C | JAM3 | s38127 | s38129 | + | − |

| Nectin 2 | PVRL2 | s11607 | s11606 | − | − |

| Talin 1 | TLN1 | s14187 | s14185 | + | − |

| PSTPIP1 | PSTPIP1 | s17257 | s17255 | + | − |

| Examples of genes not identified in 1o screen | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clathrin heavy chain | CLTC | ||||

| AP2-u2 | AP2M1 | ||||

| Ephrin-A4 | EFNA4 | ||||

| Ezrin | EZR | ||||

| Occludin | OCLN |

CHMP3 knockdown caused an increase in focus size; the other 1o screen hits showed a decrease in focus size. For % confluency: +, no decrease; −, reduced confluency (p < 0.05) for at least one siRNA/gene. For % actin tails: +, no decrease; −, reduced tail frequency (p < 0.05) for at least one siRNA/gene. See also Supplemental Figures S1 and S2.

We next determined whether any of the 30 identified genes altered focus size indirectly by inhibiting actin-based motility or disrupting host cell monolayer integrity. RNAi-treated A549 cells were infected with TagBFP-expressing L. monocytogenes (LmTagBFP), and fixed samples were stained with phalloidin to quantify the percentage of bacteria with actin tails (Supplemental Figure S1) and the extent of monolayer confluency (Supplemental Figure S2). In this secondary screen, we found that RNAi-mediated silencing of CAPZB (F-actin capping protein) and PVRL2 (cell adhesion protein Nectin 2) reduced actin tail frequencies (Supplemental Figure S1, B and C, and Table 1). CAPZB is a known regulator of L. monocytogenes actin-based motility (Loisel et al., 1999), while Nectin 2 has not been previously implicated. We also found that RNAi-mediated silencing of cell adhesion genes (e.g., PVRL2, TLN1, and CTNNA2), membrane remodeling genes (e.g., PSTPIP1 and VPS28), and CDC42 (Rho GTPase) reduced cell confluency (Supplemental Figure S2, C and D, and Table 1). In the end, eight genes with indirect effects were removed, leaving 22 host genes that were important for bacterial spread (Table 1). This list included adhesion proteins, such as E-cadherin, and several BAR domain family members, which regulate membrane curvature (Carman and Dominguez, 2018). Interestingly, we found that L. monocytogenes spread requires CAV1 and CAV2, which are core components of caveolin-mediated endocytosis in host cells (Busija et al., 2017) and may promote trafficking of the L. monocytogenes protrusion into the recipient cell. Therefore, we next examined whether caveolins regulated a specific step of L. monocytogenes spread.

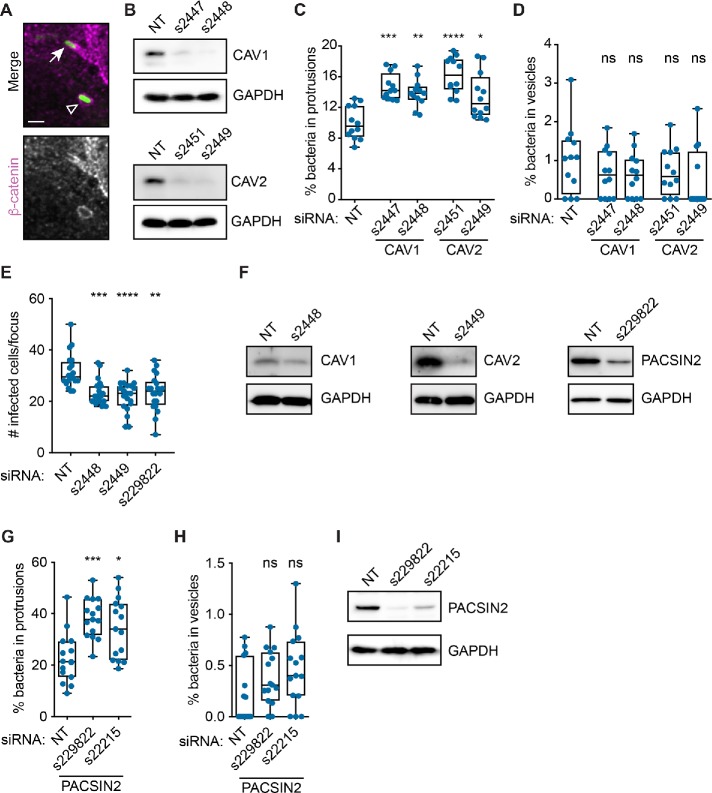

CAV1 and CAV2 promote protrusion engulfment during L. monocytogenes cell-to-cell spread

Endocytic proteins such as clathrin and caveolin regulate vesicle trafficking in host cells (Doherty and McMahon, 2009). Because bacterial spread resembles a vesicular form of trafficking, we predicted that caveolins might regulate L. monocytogenes spread by promoting protrusion engulfment into the neighboring cell. To test this, we infected A549 cells with LmGFP after RNAi treatment and measured the percentage of bacteria in protrusions and vesicles (Figure 2A). As expected, loss of CAV1 or CAV2 expression significantly increased the frequency of bacteria in protrusions (Figure 2, B and C), suggesting that infectious focus size decreased because more bacteria were getting stuck in protrusions. We did not observe an apparent effect on bacteria-containing vesicle frequency (Figure 2D), possibly due to the low incidence of this phenotype. Altogether, our data suggest that loss of CAV1 or CAV2 expression reduces cell-to-cell spread by impairing protrusion engulfment efficiency.

FIGURE 2:

CAV1, CAV2, and PACSIN2 promote L. monocytogenes protrusion engulfment. (A) Infected A549 cells showing LmGFP (green) in a protrusion (arrow) or a vesicle (open triangle). Host membrane detected via β-catenin immunofluorescence (gray; magenta in merge). Scale bar = 2 μm. (B) Western blot analysis of A549 cell lysates after indicated RNAi treatments. (C, D) Percentage of L. monocytogenes in protrusions (C) or vesicles (D) in A549 cells after RNAi-mediated silencing of CAV1 or CAV2. (E) Infectious focus assay results after RNAi-mediated silencing of CAV1 (s2448), CAV2 (s2449), or PACSIN2 (s229822) expression in Caco-2 BBe1 cells. (F) Western blot analysis of Caco-2 BBe1 cell lysates after indicated RNAi treatments. (G, H) Percentage of L. monocytogenes in protrusions (G) or vesicles (H) in A549 cells after RNAi-silencing of PACSIN2. (I) Western blot analysis of A549 cell lysates after indicated RNAi treatments. Significance determined relative to the NT siRNA control using a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparison test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. ns, not significant.

We also investigated whether CAV1 and CAV2 promoted spread in intestinal cells, a physiological target of L. monocytogenes (Radoshevich and Cossart, 2018). RNAi-mediated silencing of CAV1 or CAV2 expression in Caco-2 BBe1 (human enterocytic) cells significantly reduced infectious focus size (Figure 2, E and F), suggesting that CAV1 and CAV2 promote spread in multiple cell types. Given the importance of caveolins to L. monocytogenes spread, we next asked whether other caveolin regulators from our screen promoted protrusion engulfment.

The F-BAR protein PACSIN2 promotes protrusion engulfment during L. monocytogenes cell-to-cell spread

Caveolae biogenesis is coordinated by multiple proteins acting with caveolins to sculpt the membrane (Echarri and Del Pozo, 2015; Parton et al., 2018). For example, the F-BAR protein PACSIN2 binds to CAV1 and regulates caveolae biogenesis and endocytosis (Hansen et al., 2011; Senju et al., 2011). Intriguingly, our RNAi screen revealed that PACSIN2 also promoted bacterial spread (Table 1). Therefore, we tested whether PACSIN2 promoted L. monocytogenes protrusion engulfment by examining protrusion and vesicle frequency in A549 cells. We found that silencing PACSIN2 expression significantly increased the percentage of bacteria in protrusions (Figure 2, G and I), but did not affect vesicle frequency (Figure 2H). We also measured L. monocytogenes spread in Caco-2 BBe1 cells and found that RNAi-mediated silencing of PACSIN2 expression reduced infectious focus size (Figure 2, E and F). Overall, these results suggest that, just like CAV1 and CAV2, PACSIN2 promotes spread in multiple cell types and acts by promoting protrusion engulfment.

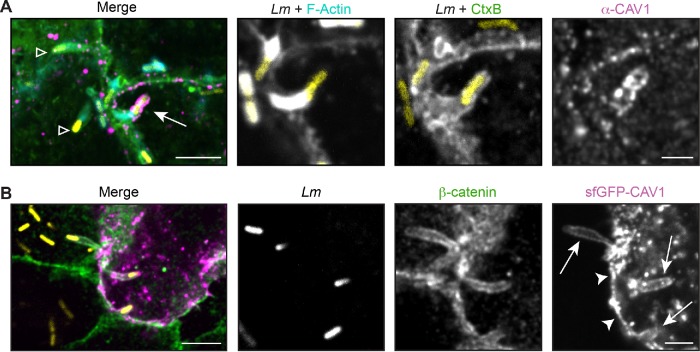

PACSIN2 localizes to L. monocytogenes–containing protrusions and is required in the recipient cell to promote spread

Because caveolins and PACSIN2 regulate protrusion engulfment, we wanted to see whether they were localized to the protrusion membrane. We first examined the localization of endogenous CAV1 to L. monocytogenes–containing protrusions because overexpression of caveolins leads to aberrant structures (Parton and Del Pozo, 2013). Infected A549 cells were fixed and stained for endogenous CAV1, and the percentage of bacterial protrusions with CAV1 localization was determined. CAV1 was observed in puncta around the plasma membrane, as had been previously shown in uninfected cells (Hansen et al., 2011). Interestingly, we only observed specific CAV1 localization on 1.7% (SD 1.3%) of the LmTagBFP-containing protrusions across two biological replicates (from a total of 2232 protrusions). CAV1 localization was also restricted to shorter protrusions (<3 µm) near the cell–cell junction (Figure 3A). Similar results were obtained with another antibody to endogenous CAV1 (unpublished data). This low frequency of colocalization may not be surprising because, relative to adipocytes or muscle cells, epithelial cells do not contain abundant caveolae (Parton and Del Pozo, 2013; Parton et al., 2018). We were also unable to detect specific recruitment of an sfGFP-CAV1 fusion transiently expressed in A549 cells. This fusion was found in spots throughout the cell and along the plasma membrane, but did not show an enhanced signal to the protrusion relative to the surrounding plasma membrane (Figure 3B). Therefore, we speculate that if caveolins are acting at the protrusion, they may be present at very low levels or are stably maintained in the membrane (Tagawa et al., 2005; Parton and Del Pozo, 2013) to recruit other factors, such as PACSIN2.

FIGURE 3:

CAV1 localization at the protrusion membrane is not enhanced during L. monocytogenes spread. (A) Infrequent localization of endogenous CAV1 (magenta) in A549 cells. Arrow indicates CAV1-positive protrusion used in inset; open triangle indicates CAV1-negative protrusions. (B) Localization of an sfGFP-CAV1 fusion (magenta) transiently expressed in A549 cells. Similar levels of sfGFP-CAV1 were seen along the plasma membrane (arrowhead) and the protrusion (arrow). For A and B, membranes (green) were detected with CtxB (A) or an antibody to β-catenin (B) after infection with LmTagBFP (Lm; yellow). Scale bar = 5 μm (inset, 2 μm).

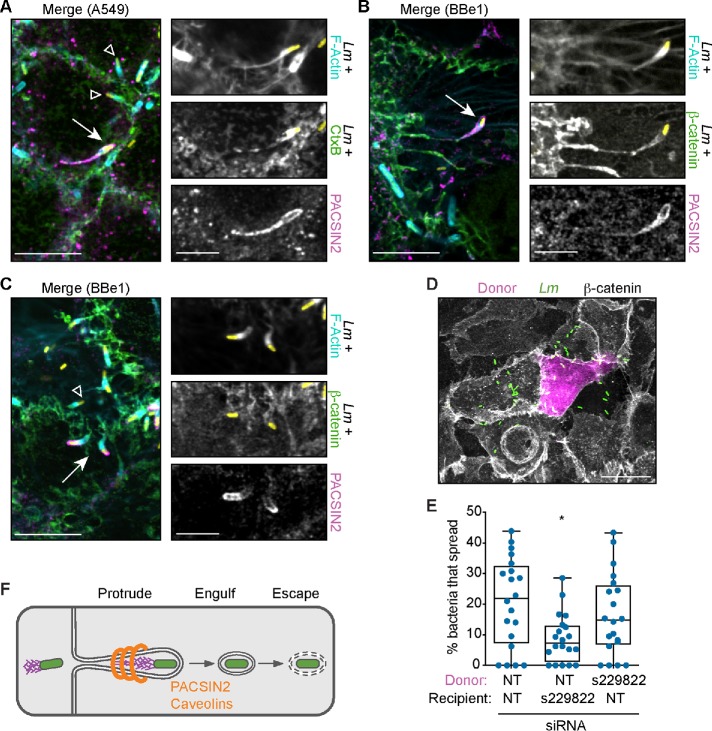

PACSIN2 is recruited to caveolae via its F-BAR domain (Hansen et al., 2011) and it directly interacts with CAV1 (Senju et al., 2011). This crescent-shaped F-BAR module also binds to positively curved membranes and can induce membrane tubulation when overexpressed in cells (Senju et al., 2011). Therefore, we predicted that PACSIN2 would localize to protrusions. To test this, cells were infected with LmTagBFP and endogenous PACSIN2 protein detected by immunofluorescence. As previously published, PACSIN2 localized to small puncta and along tubules near the plasma membrane (Hansen et al., 2011; Dorland et al., 2016). More importantly, we observed colocalization of PACSIN2 with 18.9% (SD 6.2%) of the LmTagBFP-containing protrusions in A549 cells and 7.9% (SD 4.3%) of the LmTagBFP-containing protrusions in Caco-2 BBe1 cells. PACSIN2 was often seen along the length of long protrusions with skinny membranous stalks and a collapsed actin network (Figure 4, A and B), suggesting that PACSIN2 accumulated on late-stage protrusions. A subset of the PACSIN2-containing protrusions in Caco-2 BBe1 (13.8% ± 13.6%) were shorter and exhibited specific localization of PACSIN2 to the tips of the protrusions (Figure 4C), suggesting PACSIN2 may assemble on emerging protrusions and accumulate during their elongation.

FIGURE 4:

PACSIN2 is required in the recipient cell and localizes to L. monocytogenes protrusions. (A–C) Localization of endogenous PACSIN2 (magenta) in A549 (A) or Caco-2 BBe1 (B, C) cells after infection with LmTagBFP (yellow). Scale bar = 10 μm (inset, 5 μm). For A–C, membranes (green) were detected with CtxB (A) or an antibody to β-catenin (B, C) and F-actin was labeled with phalloidin (cyan). Arrow indicates PACSIN2-positive protrusion used in inset; open triangle indicates PACSIN2-negative protrusions. (D) Image from E, showing the donor cell (magenta), LmGFP (green), and host membrane (β-catenin, gray). Scale bar = 20 μm. (E) Mixed-cell infectious focus assay in A549 cells after silencing PACSIN2 expression. (F) Diagram indicating when PACSIN2 and caveolins promote L. monocytogenes spread.

Given this striking localization, we predicted that PACSIN2 specifically acted in the recipient cell to facilitate protrusion engulfment. To test this, we used a mixed-cell infectious focus assay to determine the requirement for PACSIN2 in donor or recipient host cells. In this assay, donor cells expressing a red fluorophore (TagRFP-T) are preinfected with LmGFP and then mixed with unlabeled recipient cells (Figure 4D). Because each population is separate before the mix, we can independently reduce host gene expression levels in each cell population via RNAi. Using this assay, we found that spread was only reduced when PACSIN2 expression was silenced in the recipient cells (Figure 4E), suggesting that PACSIN2 acts specifically in the recipient cell. Taken together with the work above, our data support a model whereby caveolins and the F-BAR protein PACSIN2 promote L. monocytogenes cell-to-cell spread by regulating protrusion engulfment into the recipient cell (Figure 4F).

Conclusions

The direct exchange of cytoplasmic material between cells allows multicellular organisms to communicate and execute essential functions (Rechavi et al., 2009; Mittelbrunn and Sánchez-Madrid, 2012; Murray and Krasnodembskaya, 2019). In this study, we hypothesized that bacterial pathogens would co-opt intercellular exchange processes during spread and, using an RNAi screen, we identified new regulators of L. monocytogenes cell-to-cell spread. A key finding was that host membrane curvature and trafficking proteins (e.g., PACSIN2 and caveolins) promoted protrusion engulfment during L. monocytogenes spread. Although our data do not reveal the mechanisms of action for these factors, our work highlights how exploring such questions could provide new insights into the types of host processes co-opted by spreading bacteria and the regulation of host intercellular communication in uninfected settings.

In addition to exploring the mechanisms of PACSIN2 and caveolins, it will be essential to reveal how other hits from our screen affect L. monocytogenes spread. For example, several cell adhesion genes were identified in our screen, including E-cadherin, which is also required for Shigella flexneri spread (Sansonetti et al., 1994). Importantly, loss of E-cadherin and many other cell adhesion genes in our screen did not grossly impair monolayer integrity (Supplemental Figure S2), suggesting these factors may directly impact spread. However, we cannot rule out whether subtle effects on cell–cell junctions indirectly impact spread and we will examine this in future studies.

Intriguingly, early data suggested that the BAR protein Tuba inhibits protrusion formation (Rajabian et al., 2009), yet loss of TUBA expression in our screen decreased spread. This suggests that Tuba may also promote other stages of spread or has alternate, cell type–specific functions during spread. Indeed, Tuba was first identified as a dynamin binding partner that may promote vesicle fission during endocytosis (Salazar et al., 2003).

Nearly every host factor we identified promoted spread. However, loss of one gene (VPS24) increased infectious focus size, suggesting it normally limits spread. VPS24 encodes CHMP3, which is a component of the ESCRT-III machinery that constricts and severs membranes (Christ et al., 2017). Precisely how loss of CHMP3 enhances spread is not clear, but previous work has shown that other pathogens such as retroviruses hijack the ESCRT machinery (Scourfield and Martin-Serrano, 2017).

Finally, it was noteworthy that L. monocytogenes spread was impacted by the loss of caveolae regulators but not by clathrin endocytic machinery in our screen. This agrees with published data showing that the caveolin inhibitor MβCD but not the clathrin inhibitor PAO impairs L. monocytogenes spread (Fukumatsu et al., 2012). In contrast, S. flexneri uses clathrin-mediated endocytosis to spread (Fukumatsu et al., 2012), suggesting that pathogens have evolved unique strategies for spread. Thus, examining the species-specific mechanisms of cell-to-cell spread will uncover how different host processes are coopted by bacterial pathogens and how these mechanisms promote pathogenesis for diverse species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

A549 cells were obtained from the University of California (UC), Berkeley, tissue culture facility. Caco-2 BBe1 cells were kindly provided by the laboratory of Marcia Goldberg (Massachusetts General Hospital). All cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 and maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlas Biologicals). A549 cells stably expressing TagRFP-T (A549-TRT) were generated using retroviral transduction, as previously described (Lamason et al., 2016). Cells were confirmed to be mycoplasma free one to three times a year.

Bacterial strains

GFP-expressing wild-type L. monocytogenes (Shen and Higgins, 2005) were kindly provided by Daniel Portnoy (UC Berkeley). The GFP-expressing ΔactA L. monocytogenes strain was a gift from Michelle Reniere (University of Washington) and Dan Portnoy (UC Berkeley) and was generated by integrating pPL2-gfp (Lauer et al., 2002) into the DP-L3078 (ΔactA) strain (Skoble et al., 2000). The TagBFP-expressing L. monocytogenes strain (LmTagBFP, strain PL 1949) was a kind gift from Erin Benanti (Aduro Biotech). To generate LmTagBFP, TagBFP was codon optimized for L. monocytogenes expression by ATUM (Newark, CA) and cloned downstream from the actA promoter in pPL2. The TagBFP expression cassette was integrated at the tRNA-Arg locus of L. monocytogenes by site-specific integration (Lauer et al., 2002).

Primary siRNA screen

A Silencer Select siRNA custom library was purchased from Ambion (Life Technologies; see Supplemental Table S2). The master library plate was made by diluting siRNAs to 0.25 µM and arraying them into a deepwell 384-well storage microplate (Corning Axygen P-384-120SQ-C) as indicated in Figure 1A. A nontarget siRNA (Negative control #1 siRNA, #4390843) was used as a negative control and an siRNA against the ARPC4 gene (Ambion AM16708) was selected as a positive control. Note that this reagent is from Ambion’s Silencer collection, which requires more siRNA per reaction. To set up screen plates, 1 µl of siRNA from each well of the master plate was spotted onto a 384-well µClear black plate (Greiner 781091) using an Agilent Velocity 11 Bravo liquid handler. A549 cells were then reverse transfected in these plates via Lipofectamine RNAiMAX using a Multidrop Combi Dispenser (Thermo Scientific) to dispense cells and reagents, which resulted in a final siRNA concentration of 5 nM (or 50 nM for the ARPC4-specific siRNA) and 4.4 × 103 cells per well.

To measure L. monocytogenes spread efficiency via the infectious focus assay, transfected cells were infected 72 h posttransfection at an MOI of 0.08 and plates were centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min at 25°C and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Samples were washed one time with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before adding complete media with 10 µg/ml gentamicin, and the infection progressed for an additional 3.5 h at 37°C until fixation and staining. Infected cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 1X PBS for 10 min at room temperature and washed twice in 1X PBS. Staining was then performed on the Agilent Velocity 11 Bravo liquid handler as follows: fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Tx100) for 5 min at room temperature, washed once with 1X PBS, and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies diluted with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1X PBS. To increase the detection of our GFP-expressing bacteria, we found that staining for each strain was necessary. Therefore, L. monocytogenes was stained using rabbit anti-Listeria (Difco 223021), and nuclei stained with Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes). Stained cells were covered with 50 µl per well of sterile 50% glycerol in 1X PBS before imaging.

Primary screen plates were imaged on an ImageXpress Micro High Content Imaging System (Molecular Devices) using a 20× ELWD objective. To sample most of the well surface area, a 5 × 5 or 6 × 6 grid of images were collected and processed and stitched together using Fiji (ImageJ; Schindelin et al., 2012) to create a montage. Montages were then analyzed using CellProfiler (Carpenter et al., 2006) to detect the positions of bacteria and nuclei in the stitched images and to estimate cell boundaries. This information was then analyzed using R (RStudio) to determine the number of infected cells per focus of infection (aka average cluster size) and the number of foci per well. Bacterial density was measured by quantifying the cumulative GFP signal intensity per focus and the values representing ≤4 bacteria determined manually. Foci with less than four bacteria were excluded from the analysis because they likely represented an unproductive infection. For each well, the average number of infected cells per focus (or average cluster size) was calculated and this value was used in selecting hits.

To select hits, two independent runs of the screens were done on different days and the results were compared between these two runs. In each run, the SD was calculated for the 10 replicates of the NT control samples and this was used to measure the extent of the effects of each of our test siRNAs. siRNAs that increased or decreased the average cluster size per well by at least 2 SD were considered to have an effect. In each plate, every target gene was represented by three different siRNAs, each within their own well. Therefore, we only deemed a “hit” when at least two siRNAs per gene showed a consistent 2 SD effect across both runs of the screen (Supplemental Table S1).

Secondary siRNA screen

To conduct the secondary siRNA screens, two siRNAs per gene were selected from the primary screen based on their ability to generate a consistent spread phenotype. To examine the effects of these siRNAs on host cell confluency and actin tail frequency, 2 × 104 A549 cells were reverse transfected with 5 nM siRNA via Lipofectamine RNAiMAX in a 384-well µClear black plate (Greiner 781091). In each plate, each siRNA was set up in triplicate and two full runs of the screen were completed for each infection. Infections with TagBFP-expressing L. monocytogenes (LmTagBFP) were started 4 d after transfection at an MOI of 0.25. After adding bacteria, infected cells were centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min at 25°C and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. At the end of the incubations, samples were fixed in 4% PFA in 1X PBS for 10 min at room temperature and washed once in 1X PBS. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Tx100 for 5 min at room temperature, washed three times with 1X PBS, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (ThermoFisher) diluted in 2% BSA in 1X PBS. Samples were then washed three times in 1X PBS and fresh 1X PBS was used to overlay samples before imaging.

Imaging of screen plates was done on an OperaPhenix High Content Imaging System (Perkin Elmer) using a 63× water immersion objective. For each well, four images were collected from randomly selected regions, processed using Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012), and analyzed using CellProfiler (Carpenter et al., 2006) to quantify the number of bacteria per field of view and the cell confluency. For the cell confluency measurement, images with phalloidin signal only were converted to binary images and the percentage of confluency was quantified as the fraction of the image surface area covered by cells. To calculate the actin tail frequency, each image was manually scored for the number of bacteria with tails at least one bacterial length long and this number was divided by the number of total bacteria in the field. For every well, the average phenotype across the four separate images was calculated and these well-based averages were plotted in Supplemental Figures S1 and S2.

Infectious focus assay

To measure L. monocytogenes spread efficiency in Caco-2 BBe1, 12 mm sterile coverslips in a 24-well plate were first coated with 15 µg collagen-I (Sigma C7661) for 1 h at room temperature, washed three times with 1X PBS, and stored dry at 4°C until use. Then, 2 × 105 cells were plated onto the collagen-coated coverslips and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The next day, the cells were transfected with 10 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (ThermoFisher). After 72-h transfection, samples were infected with LmGFP at an MOI of 0.01, spun down for 5 min at 200 × g at 25°C, and then incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were then washed three times in 1X PBS before adding complete media with 10 µg/ml gentamicin. Infections proceeded for an additional 9–10 h at 37°C followed by fixation in 4% PFA in 1X PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Fixed samples were washed once in 1X PBS and then incubated with 0.1 M glycine in 1X PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were then washed three times with 1X PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% Tx100 for 5 min at room temperature, and washed once with 1X PBS. Samples were then blocked in blocking buffer (2% BSA in 1XPBS) and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes) was used to stain the nucleus, mouse anti–β-catenin (Cell Signaling 2677S) was used to detect the host plasma membrane, and Alexa Fluor 647 phalloidin (ThermoFisher) was used to detect F-actin. Images were captured on our Olympus IXplore Spin microscope system with a Yokogawa CSU-W1 spinning-disk unit, 60× UPlanSApo (1.3 NA) and 100× UPlanSApo (1.35 NA) objectives, an ORCA-Flash4.0 sCMOS camera, and CellSens software. Infectious foci (15–20) were imaged per condition, images were processed in Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012), and the number of infected cells/focus calculated.

Protrusion and vesicle frequency assay

To measure the percent of bacteria in protrusions and vesicles, 0.75 × 105 A549 cells were plated on 12-mm coverslips in 24-well plates. Cells were transfected 24 h later, with 5 nM siRNA via Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (ThermoFisher). After 72-h transfection, cells were infected with LmGFP at an MOI of 1–1.3 by centrifuging plates for 5 min at 200 × g at 25°C and subsequently incubating at 37°C for 4.5 h before fixation with 4% PFA/1X PBS. Fixed samples were stained as above for the Caco-2 BBe1 cell infectious focus assay. Images were captured on either a Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope with an Andor Revolution spinning-disk confocal, Andor Zyla 5.5 sCMOS camera, and a 100× PlanApo objective (Figure 2, C and D) at the WM Keck Microscopy Facility, or our Olympus IXplore Spin microscope system described above with a 100× UPlanSApo (1.35 NA) objective (Figure 2, G and H). Twelve to fifteen fields of view were captured across two to three coverslips per experiment (with each field containing ∼100–1000 bacteria). Images were processed in Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012) and the average percentage of bacteria in protrusions and vesicles was calculated. Note that we suspect that the differences in image resolution acquired on the two different systems account for the different frequencies seen in the NT controls (Figure 2, C, D, G, and H). To confirm this, s2448 was used as a positive control when acquiring the PACSIN2 data, and we were able to see an increase in protrusion frequency compared with the NT control (unpublished data).

Mixed-cell infectious focus assay

To set up the mixed-cell spread assays, 5.4 × 103 donor cells/well (A549-TRT) in 96-well plates (Nunc/ThermoFisher Scientific), and 2 × 105 recipient cells/well (A549) in six-well plates (Genesee Scientific) were reverse transfected with 5 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (ThermoFisher). After 72-h plating, donors were infected with 2 × 106 colony forming units (cfu) of LmGFP and plates were centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min at 25°C and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. All samples (donor and recipient cells) were then washed once with PBS, lifted with 37°C 1X citric saline (135 mM KCl, 15 mM sodium citrate), and recovered in complete media. Cells were pelleted and then washed twice in complete media to remove residual citric saline. Donor cell pellets were resuspended in 50 µl and recipient cell pellets resuspended in 1.3 ml complete media + 10 µg/ml gentamicin. Cells were then mixed at a cell ratio of 1:125 (5.3 µl donors plus 500 µl recipients) and plated onto 12-mm coverslips in a 24-well plate. To facilitate fast adherence to the glass, the coverslips were precoated overnight at 4°C with 5 µg/ml fibronectin (EMD Millipore) in 1X PBS and washed with 1X PBS immediately before adding the cell mixtures. Infections were allowed to progress at 37°C for 4–4.5 h until fixation and staining. Staining proceeded as above for the Caco-2 BBe1 cell infectious focus assay, except samples were only stained with mouse anti–β-catenin (Cell Signaling 2677S). To quantify spread, 20 individual foci were imaged on our Olympus IXplore Spin system. Images were then processed in Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012) and the percentage of bacteria per focus that had spread to recipient cells was calculated.

Immunolocalization of host factors

To measure the frequency of PACSIN2, CAV1, and CAV2 localization during L. monocytogenes cell-to-cell spread, 1.5 × 105 A549 cells were first plated onto 12-mm coverslips in a 24-well plate. Cells were infected 72 h later, with 1 × 105 cfu of LmTagBFP and plates were centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min at 25°C. Plates were then placed at 37°C and infection proceeded for 5 h before fixation in 4% PFA in 1X PBS for 10 min at room temperature.

For localization studies in Caco-2 BBe1 cells, each coverslip was first coated with 15 µg collagen-I (Sigma C7661) for 1 h at room temperature, washed three times with 1X PBS, and stored dry at 4°C until use. Then, 1.5 × 105 Caco-2 BBe1 cells were added to coated coverslips and after 48 h, the media was changed. The next day, cells were infected with 2 × 106 cfu of LmTagBFP and plates centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min at 25°C. Infections in Caco-2 BBe1 cells progressed for 9.5 h at 37°C followed by fixation in 4% PFA in 1X PBS for 10 min at room temperature.

Once fixed, all samples were washed once in 1X PBS and then incubated with 0.1 M glycine in 1X PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were then washed three times with 1X PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% Tx100 for 5 min at room temperature and washed once with 1X PBS. Samples were then incubated with Image-iT FX signal enhancer (ThermoFisher) for 30 min at room temperature, washed once with 1X PBS, then blocked with blocking buffer (2% BSA in 1X PBS) for 30 min at room temperature. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated for 1 h each at room temperature. The following stains and antibodies were used: rabbit anti-PACSIN2 (Abgent AB8088b), rabbit anti-CAV1 (Abcam ab2910), rabbit anti-CAV1 (Cell Signaling 3267; unpublished data), mouse anti-CAV2 (BD 610684), Alexa Fluor 647 phalloidin (ThermoFisher), mouse anti–β-catenin (Cell Signaling 2677S), and Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated Cholera Toxin Subunit B (Invitrogen C34778). Ten random fields of view per sample were imaged on our Olympus IXplore Spin microscope system using a 100X UPlanSApo (1.35 NA) objective. Images were processed in Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012) and the percentage of protrusions showing colocalization with the host proteins of interest was calculated across two independent experiments. Percentages were collected across two biological replicates in both A549 cells (from a total of 864 protrusions for PACSIN2 or 2232 protrusions for CAV1) and Caco-2 BBe1 cells (from a total of 1899 protrusions).

Transient expression of sfGFP-CAV1

To visualize CAV1 localization during L. monocytogenes cell-to-cell spread, 1.1 × 105 A549 cells were first plated onto 12-mm coverslips in a 24-well plate. Cells were transfected 48 h later, with 10 ng sfGFP-CAV1 using Lipofectamine LTX with PLUS Reagent (ThermoFisher). sfGFP-CAV1 (sfGFP-Caveolin-C-10) was a gift from Michael Davidson (Addgene plasmid # 56366). After 48-h transfection, cells were infected with 4 × 105 cfu of LmTagBFP and plates were centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min at 25°C. Plates were then placed at 37°C and infection proceeded for 5 h before fixation in 4% PFA in 1X PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Once fixed, all samples were processed as above. The following stains and antibodies were used: mouse anti–β-catenin (Cell Signaling 2677S) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 (ThermoFisher). Images were acquired on our Olympus IXplore Spin microscope system using a 100X UPlanSApo (1.35 NA) objective.

Western blot analysis

To determine the extent of knockdown, cells were first lysed in immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% IGEPAL) on ice for 10 min. The cell debris was then cleared via centrifugation at 16,100 × g 4°C for 10 min. Lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using rabbit anti-PACSIN2 (Agent AP8088b), mouse anti-CAV1 (BD 610406), mouse anti-CAV2 (BD 610684), rabbit anti-CAV1 (for use with Caco-2 BBe1 cells; Abcam ab2910), rabbit anti-CAV2 (for use with Caco-2 BBe1 cells; Cell Signaling D4A6), and mouse anti-GAPDH (AM4300; Ambion).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad PRISM 8 and the parameters and significance are reported in the figures and the figure legends. Asterisks denote statistical significance as follows: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001, compared with indicated controls. For graphs depicted as box plots, boxes outline the 25th and 75th percentiles, midlines denote medians, and whiskers show the minimum and maximum values.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew Welch for his incredible generosity in letting R.L.L. start this study while she was a postdoc in his lab. We thank Jon McGinn, Adam Martin, Iain Cheeseman, and Matthew Welch for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Erin Benanti, Michelle Reniere, and Dan Portnoy for sharing reagents. Invaluable technical help for the RNAi screen was provided by Trish Birk, Mary West, Pingping He, and Andreas Ettinger. This work was performed in part at the QB3 High Throughput Screening Facility (UC Berkeley) and the Keck Imaging Facility (Whitehead/MIT). This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants no. S10OD-021828 and no. T32GM-007287. R.L.L. is supported by NIH Grant no. R00GM-115765.

Abbreviations used:

- BAR

Bin1/amphiphysin/Rvs167

- CAV

caveolin

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- Lm

Listeria monocytogenes

- NT

nontarget

- PACSIN2

protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neurons 2

- RNAi

RNA interference

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TagBFP

blue fluorescent protein

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E19-04-0197) on June 26, 2019.

REFERENCES

- Busija AR, Patel HH, Insel PA. (2017). Caveolins and cavins in the trafficking, maturation, and degradation of caveolae: implications for cell physiology. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol , C459–C477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman PJ, Dominguez R. (2018). BAR domain proteins—a linkage between cellular membranes, signaling pathways, and the actin cytoskeleton. Biophys Rev , 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter AE, Jones TR, Lamprecht MR, Clarke C, Kang IH, Friman O, Guertin DA, Chang JH, Lindquist RA, Moffat J, et al. (2006). CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol , R100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong R, Swiss R, Briones G, Stone KL, Gulcicek EE, Agaisse H. (2009). Regulatory mimicry in Listeriamonocytogenes actin-based motility. Cell Host Microbe , 268–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ L, Raiborg C, Wenzel EM, Campsteijn C, Stenmark H. (2017). Cellular functions and molecular mechanisms of the ESCRT membrane-scission machinery. Trends Biochem Sci , 42–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. (2009). Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem , 857–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domann E, Wehland J, Rohde M, Pistor S, Hartl M, Goebel W, Leimeister-Wächter M, Wuenscher M, Chakraborty T. (1992). A novel bacterial virulence gene in Listeria monocytogenes required for host cell microfilament interaction with homology to the proline-rich region of vinculin. EMBO J , 1981–1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorland YL, Malinova TS, van Stalborch A-MD, Grieve AG, van Geemen D, Jansen NS, de Kreuk B-J, Nawaz K, Kole J, Geerts D, et al. (2016). The F-BAR protein pacsin2 inhibits asymmetric VE-cadherin internalization from tensile adherens junctions. Nat Commun , 12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echarri A, Del Pozo MA. (2015). Caveolae—mechanosensitive membrane invaginations linked to actin filaments. J Cell Sci , 2747–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumatsu M, Ogawa M, Arakawa S, Suzuki M, Nakayama K, Shimizu S, Kim M, Mimuro H, Sasakawa C. (2012). Shigella targets epithelial tricellular junctions and uses a noncanonical clathrin-dependent endocytic pathway to spread between cells. Cell Host Microbe , 325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J, Körner R, Gaitanos L, Klein R. (2016). Exosomes mediate cell contact-independent ephrin-Eph signaling during axon guidance. J Cell Biol , 35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen CG, Hansen CG, Howard G, Howard G, Nichols BJ, Nichols BJ. (2011). Pacsin 2 is recruited to caveolae and functions in caveolar biogenesis. J Cell Sci , 2777–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocks C, Gouin E, Tabouret M, Berche P, Ohayon H, Cossart P. (1992). L. monocytogenes-induced actin assembly requires the actA gene product, a surface protein. Cell , 521–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamason RL, Bastounis E, Kafai NM, Serrano R, del Álamo JC, Theriot JA, Welch MD. (2016). Rickettsia Sca4 reduces vinculin-mediated intercellular tension to promote spread. Cell , 670–683.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamason RL, Welch MD. (2016). Actin-based motility and cell-to-cell spread of bacterial pathogens. Curr Opin Microbiol , 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer P, Chow MYN, Loessner MJ, Portnoy DA, Calendar R. (2002). Construction, characterization, and use of two Listeria monocytogenes site-specific phage integration vectors. J Bacteriol , 4177–4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loisel TP, Boujemaa R, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. (1999). Reconstitution of actin-based motility of Listeria and Shigella using pure proteins. Nature , 613–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston DJ, Dickinson S, Nobes CD. (2003). Rac-dependent trans-endocytosis of ephrinBs regulates Eph–ephrin contact repulsion. Nat Cell Biol , 879–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelbrunn M, Sánchez-Madrid F. (2012). Intercellular communication: diverse structures for exchange of genetic information. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol , 328–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monack DM, Theriot JA. (2001). Actin-based motility is sufficient for bacterial membrane protrusion formation and host cell uptake. Cell Microbiol , 633–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LMA, Krasnodembskaya AD. (2019). Concise review: intercellular communication via organelle transfer in the biology and therapeutic applications of stem cells. Stem Cells , 14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton RG, Del Pozo MA. (2013). Caveolae as plasma membrane sensors, protectors and organizers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol , 98–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton RG, Tillu VA, Collins BM. (2018). Caveolae. Curr Biol , R402–R405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piehl M, Lehmann C, Gumpert A, Denizot J-P, Segretain D, Falk MM. (2007). Internalization of large double-membrane intercellular vesicles by a clathrin-dependent endocytic process. Mol Biol Cell , 337–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pust S, Morrison H, Wehland J, Sechi AS, Herrlich P. (2005). Listeria monocytogenes exploits ERM protein functions to efficiently spread from cell to cell. EMBO J , 1287–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radoshevich L, Cossart P. (2018). Listeria monocytogenes: towards a complete picture of its physiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol , 32–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajabian T, Gavicherla B, Heisig M, Müller-Altrock S, Goebel W, Gray-Owen SD, Ireton K. (2009). The bacterial virulence factor InlC perturbs apical cell junctions and promotes cell-to-cell spread of Listeria. Nat Cell Biol , 1212–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechavi O, Goldstein I, Kloog Y. (2009). Intercellular exchange of proteins: the immune cell habit of sharing. FEBS Lett , 1792–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins JR, Barth AI, Marquis H, de Hostos EL, Nelson WJ, Theriot JA. (1999). Listeria monocytogenes exploits normal host cell processes to spread from cell to cell. J Cell Biol , 1333–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Woolls MJ, Jin S-W, Murakami M, Simons M. (2014). Inter-cellular exchange of cellular components via VE-cadherin-dependent trans-endocytosis. PLoS One , e90736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar MA, Kwiatkowski AV, Pellegrini L, Cestra G, Butler MH, Rossman KL, Serna DM, Sondek J, Gertler FB, De Camilli P. (2003). Tuba, a novel protein containing bin/amphiphysin/Rvs and Dbl homology domains, links dynamin to regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem , 49031–49043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansonetti PJ, Mounier J, Prévost MC, Mège RM. (1994). Cadherin expression is required for the spread of Shigella flexneri between epithelial cells. Cell , 829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods , 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scourfield EJ, Martin-Serrano J. (2017). Growing functions of the ESCRT machinery in cell biology and viral replication. Biochm Soc Trans , 613–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senju Y, Itoh Y, Takano K, Hamada S, Suetsugu S. (2011). Essential role of PACSIN2/syndapin-II in caveolae membrane sculpting. J Cell Sci , 2032–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen A, Higgins DE. (2005). The 5′ untranslated region-mediated enhancement of intracellular listeriolysin O production is required for Listeria monocytogenes pathogenicity. Mol Microbiol , 1460–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoble J, Portnoy DA, Welch MD. (2000). Three regions within ActA promote Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin nucleation and Listeria monocytogenes motility. J Cell Biol , 527–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagawa A, Mezzacasa A, Hayer A, Longatti A, Pelkmans L, Helenius A. (2005). Assembly and trafficking of caveolar domains in the cell: caveolae as stable, cargo-triggered, vesicular transporters. J Cell Biol , 769–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman AM, Chong R, Chia J, Svitkina T, Agaisse H. (2014). Actin network disassembly powers dissemination of Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Sci , 240–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. (1989). Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol , 1597–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weddle E, Agaisse H. (2018). Principles of intracellular bacterial pathogen spread from cell to cell. PLoS Pathog , e1007380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch MD, Iwamatsu A, Mitchison TJ. (1997). Actin polymerization is induced by Arp2/3 protein complex at the surface of Listeria monocytogenes. Nature , 265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.