Abstract

Cover-copy-compare (CCC) is a self-managed intervention that relies on modeling, opportunities to respond, and corrective feedback to improve spelling. Refinements to CCC have been investigated to maximize its effectiveness and efficiency. One such refinement is the addition of a sounding-out step (CCC+SO). Because research investigating CCC+SO has yielded inconsistent results, the current study sought to further examine CCC+SO while addressing some of the methodological limitations of previous studies. An alternating-treatments design was used to compare CCC and CCC+SO on the cumulative number of spelling words acquired with three 2nd and 3rd graders. Participants practiced spelling words using CCC and CCC+SO and demonstrated considerable growth in spelling performance from baseline to intervention; however, there was little difference in cumulative spelling words acquired across conditions. Implications for practitioners and researchers, limitations, and future directions are discussed.

Keywords: Acquisition, Alternating-treatments design, Cover-copy-compare, Maintenance, Spelling

Cover-copy-compare (CCC) is a self-managed spelling intervention with components of modeling, self-correction, and immediate feedback that has been shown to teach students to spell more accurately than students who are taught using traditional spelling instruction (Alber & Walshe, 2004). To use CCC, students look at a word, study it, then cover it up and try to spell the word without looking at it. They then uncover the word to see if they spelled it correctly. If they spelled the word correctly, they move on to the next word, but if they spelled the word incorrectly, they repeat the process for the same word (Mann, Bushell Jr., & Morris, 2010). Allowing the student’s last response in each trial to be an accurate response is thought to reinforce accurate responses and prevent responses that are incorrect (Skinner, McLaughlin, & Logan, 1997).

There are many advantages to the CCC method beyond its effectiveness. First, it is a simple procedure that does not require teachers to have any specialized training or equipment (Skinner et al., 1997). The simplicity of CCC allows students to spend more time learning than wasting time on content they are implicitly expected to learn, such as memorizing an isolated list of words each week (Fulk & Stormont-Spurgin, 1995). Second, as previously stated, students can self-manage the intervention once they are shown how to use it, making it possible for them to work on their own. This saves time and makes CCC a practical method for use in classrooms (Skinner et al., 1997). Finally, self-correction may be more effective than traditional spelling instruction, which includes teacher-directed correction, because it requires students to focus on and point out their own spelling errors, increasing the likelihood that subsequent responses will be accurate (Skinner et al., 1997). When students perform at high levels of accuracy, it increases the probability of learning (Archer & Hughes, 2011).

When considering for whom the CCC procedure is most effective, research suggests that students with and without disabilities can benefit from CCC both in and out of a traditional school setting (Hubbert, Weber, & McLaughlin, 2000; Joseph et al., 2012). Students with a wide range of disabilities, including students receiving special education services, students with conduct disorder, and students with attention deficit disorder, have shown an increase in spelling performance when using CCC compared to traditional spelling instruction (Alber & Walshe, 2004; Hubbert et al., 2000; Viel-Ruma, Houchins, & Fredrick, 2007).

A number of researchers have examined the effectiveness and efficiency of refinements to CCC (Erion, Davenport, Rodax, Scholl, & Hardy, 2009; Fisher, 2012; Mann et al., 2010). For example, some research has looked at the addition of a sounding-out step (CCC+SO) to increase the effectiveness of CCC. One study compared CCC to CCC+SO using a multielement design to measure the percentage of correctly spelled words (Mann et al., 2010). Five typically developing students with poor spelling skills were given pretests to identify unknown words, which were practiced during intervention sessions each day using both traditional CCC and CCC+SO. Posttests were given the following day, where words from the CCC condition were not sounded out and words from the CCC+SO condition were sounded out. Results indicated that sounding out produced higher levels of spelling accuracy than CCC.

Fisher (2012) attempted to improve the methodology of the previous CCC+SO study by using a multiple-baseline design to decrease the possibility of carryover effects. In this study, traditional CCC was the baseline phase and CCC+SO was the intervention phase. The participants were five second- and third-grade students, one of whom qualified for special education services with a specific learning disability. Stimulus words were selected based on the school district’s spelling curriculum and were classified as having common or uncommon spellings based on the frequency of occurrence for each grapheme-phoneme relationship in the English language. The study also consisted of pretesting sessions, intervention sessions, and posttesting sessions. The author measured the participants’ spelling between the pre- and posttests using both correct letter sequences and whole words correct. Although adjustments were made to improve upon previous research, results were inconsistent. The author indicated that there was not a discernable difference from pretest to posttest between CCC and CCC+SO, overall or by word type (i.e., words with common or uncommon spellings). The results led to the need for future examination of CCC and CCC+SO for spelling.

Further examination of a sounding-out variation of CCC is important because data suggest that reading and spelling are positively correlated (Graham, Harris, & Fink-Chorzempa, 2002). High performance in one area may indicate high performance in the other, given the similarities between the skills students need to both spell and read words that are phonetically regular. Sounding out words as students spell combines basic reading skills with spelling to enhance spelling performance and vice versa. Beginning in kindergarten, students are taught to associate letters with their most common sound, a skill needed to become a successful reader and a successful speller (Archer & Hughes, 2011). The sounding-out procedure makes the connection between reading and spelling more explicit for struggling spellers. Using this method, which is taught to children from a young age, could assist them in improving both spelling and reading performance.

Research on CCC+SO has yielded inconsistent results and has involved some methodological shortcomings. The purpose of the current study was to replicate and extend previous research through improvement of those methodological limitations. First, this study used a screening procedure to ensure students have norm-referenced difficulties in spelling and the ability to provide the most common sound for letters of the alphabet in isolation. Second, the process for identifying unknown spelling words was explicit and systematic, as well as somewhat more intensive than previous studies. Third, unlike Mann et al. (2010), procedures for measuring the primary dependent variable were consistent across conditions. This allowed us to conclude whether any differences across the conditions were solely due to differences in how words were practiced. Finally, strategies to attempt to decrease potential carryover effects of the sounding-out strategy were implemented. The purpose of the current study was to compare CCC and CCC+SO on the cumulative number of words mastered by using an alternating-treatments design.

Method

Participants and Setting

Participants included three elementary school students: Angela, Bobby, and Stephanie. Demographic information on the participants, including gender, age, grade, race/ethnicity, native language, free and reduced lunch eligibility, and disability status are located in Table 1. Parent consent and student assent were documented, and procedures were carried out in accordance with the authors’ institutional review board.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information

| Age | Grade | Race/Ethnicity | Native Language | FRL | Disability | School | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angela | 8 | 2 | Caucasian | English | No | SLI | Western |

| Bobby | 7 | 2 | Caucasian | English | No | SLD | Western |

| Stephanie | 8 | 3 | Caucasian | English | Yes | None | Eastern |

FRL free/reduced lunch, SLI speech or language impairment, SLD specific learning disability

Intervention occurred at two suburban elementary schools in the Midwestern region of the United States. The first school, Eastern Elementary, was composed of about 362 students and served Grades K through 5. About 75% of students at Eastern Elementary received free/reduced lunch, and the racial/ethnic breakdown is as follows: 84% Caucasian, 6% African American, 5% Hispanic, 3% two or more races, 1% Asian, and 1% American Indian. The second school, Western Elementary, was composed of about 400 students and served Grades K through 4. About 49% of students at Western Elementary receive free/reduced lunch, and the racial/ethnic breakdown is as follows: 78% Caucasian, 7% Asian, 5% African American, 3% two or more races, 3% Hispanic, 3% American Indian, and 1% Pacific Islander.

Screening

Screening was conducted to determine whether participants demonstrated norm-referenced difficulties in spelling and had prerequisite phonics skills for the sounding-out condition of the intervention. The Test of Written Spelling, Fifth Edition (Larsen, Hammill, & Moats, 2013), was administered to determine whether the participants displayed spelling difficulties compared to same-age peers. Results are described as standard scores (M = 100, SD = 15), and participants were required to score below the average range (i.e., standard score < 85) to be included in the study. An informal measure of phonics was used to show that the participants had prerequisite phonics skills for the sounding-out condition of the intervention. Participants were presented the 26 letters of the alphabet in isolation and were asked to state the most common sound for each letter. To meet the eligibility criteria for the current study, participants were required to state the most common sound for 85% of letters. Results of screenings are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of screening tests

| TWS-5 Standard Score |

TWS-5 Percentile | Phonics Test Percentage Correct |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Angela | 82 | 12 | 88 |

| Bobby | 80 | 9 | 100 |

| Stephanie | 79 | 8 | 94 |

TWS-5 Test of Written Spelling, Fifth Edition (Larsen et al., 2013)

Pretesting

Prior to beginning intervention, pretesting was used to identify unknown words. Words were selected in conjunction with the schools based on their spelling curricula and were decodable to make the sounding-out condition possible. The words used for pretesting and stimuli selection included consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words that begin with both continuous and stop sounds; CVCC words that end with consonant blends and double consonants; CCVCC, CCCVC, and CCCVCC words; y-derivative words; two-syllable words with a single consonant in the middle; VCe pattern words in which the vowel is long; and a variety of combinations of word roots, prefixes, and suffixes (Carnine, Silbert, Kame’enui, & Tarver, 2010).

The selected words were presented orally to the participants, and they were asked to spell them on a sheet of lined paper. Words spelled correctly were removed for each participant, and words spelled incorrectly were presented a second time. This testing continued until approximately 30 unknown words were identified. Unknown words were used to randomly create two sets of stimuli, with approximately 15 words each. As participants approached mastery of all generated words, additional pretesting of novel words occurred periodically. Table 3 contains the initial word lists by participant and condition.

Table 3.

Initial word lists by participant and condition

| Angela | Bobby | Stephanie | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCC | CCC+SO | CCC | CCC+SO | CCC | CCC+SO |

| plum | must | bony | text | just | scab |

| smog | melt | panic | admit | went | disc |

| skid | glad | jump | knee | rapid | robin |

| help | send | miss | hung | knee | bony |

| last | lost | return | behind | taxi | admit |

| jump | lamp | dawn | corner | poke | knit |

| just | skin | profit | disk | wrap | boat |

| past | damp | poke | mean | bird | dirt |

| gift | camp | hurt | born | frame | snack |

| tusk | belt | grew | taxi | coats | globe |

| text | flag | wrap | used | board | write |

| scab | slam | miss | knit | visit | bites |

| rust | golf | much | chew | grape | roots |

| blot | spin | fish | bird | knock | hopes |

| swim | clam | cuff | chat | slope | cubes |

| stem | scan | dirt | dress | ||

Stimuli Selection

The two sets of stimuli were then randomly assigned to either the CCC or the CCC+SO condition. Intervention sessions included five words from each set of words. To create equivalent word lists for both conditions, each word on the first list had a similar, corresponding word on the second list. This was established by matching words by number of letters (Mann, 2014). Once a participant had acquired a word from either list by spelling it correctly in three consecutive sessions, the word was replaced by another word from the corresponding set (CCC or CCC+SO). To ensure that students would not be exposed to the unknown words from the pretest while the intervention took place, the interventionist worked with the teachers to select words that would not be included in the spelling curriculum before the intervention was completed. As a result, a total of seven words were removed from the word lists.

Response Measurement

Interventionists collected data on correct and incorrect responses during retention tests (i.e., short term and long term) and intervention sessions. Responses were considered correct when the participant’s written response identically matched the interventionist’s model. Incorrect responses were recorded when the participant’s written response did not identically match the interventionist’s model. Short-term retention tests were used to determine mastery of a word. When a participant spelled a word correctly on three consecutive retention tests, the word was added to a cumulative record of words acquired and removed from words currently being practiced.

The cumulative number of words mastered was the primary dependent variable, modeled after the methodological framework of prior intervention research (Worsdell et al., 2005). Long-term retention tests were used to determine maintenance of previously mastered words. Data from long-term retention tests are reported as a mean percentage accuracy. Incorrect responses during intervention sessions were also recorded to determine if there was a relationship between the number of errors made and the practice condition (CCC or CCC+SO). Incorrect responses were reported as a frequency count.

Experimental Design and Procedure

An alternating-treatments design was used to compare the effects of CCC and CCC+SO. Data were collected between 3 and 5 days per week (M = 3.7 days) for 6 to 7 weeks per participant. Interventionists were two graduate students in school psychology. Intervention occurred in a private location in the participants’ schools. Each day of intervention began with a short-term retention test. Short-term retention tests involved assessing performance on words currently being practiced with CCC or CCC+SO. Short-term retention tests were used to make decisions about whether a word met the mastery criterion. On the final day of intervention each week, long-term retention tests were administered in addition to short-term retention tests. Long-term retention tests involved assessing performance on words previously mastered. After the day’s short-term retention test (and long-term retention test, if applicable), participants were given a short break. After the break, the first of two intervention sessions began (CCC or CCC+SO). The order of intervention sessions was randomly determined each day. A short break followed the first intervention session. After the break, the second intervention session was conducted.

Retention Tests

Each day, before beginning any intervention sessions, short-term retention tests were administered on words practiced during the previous day’s sessions. The 10 words currently being practiced were presented orally and randomly, and the participants were asked to spell the words on a sheet of lined paper. Students were instructed not to sound out words during the short-term retention tests regardless of which condition the words were assigned to. There were no programmed consequences based on accuracy of responding.

At the end of every week, long-term retention tests were administered with the same procedure as the short-term retention tests to determine which words the participants would continue to spell correctly without intervention in place. Words used in the long-term retention tests included all words that were identified as mastered from the short-term retention tests.

Baseline

Short-term retention tests were administered over a period of at least three sessions to determine whether words would be mastered with no intervention in place. There were no intervention sessions during the baseline condition.

Training

Following baseline data collection, participants were trained to use CCC and CCC+SO. To do so, the interventionist followed a checklist created for the current study. The checklist described steps necessary for intervention implementation and involved instructing students to take time to study the word, sound out the word (for CCC+SO), cover the word list, copy the word, uncover the word list, and engage in error correction contingent on an incorrectly spelled word. Participants practiced these steps with phonetically regular CVC words, like cat or dog, to ensure that learning focused on the method rather than learning novel words. Training occurred in one brief session.

CCC

Words were presented on a sheet of lined, numbered paper. Participants were instructed to briefly study the word, cover the word, attempt to spell the word, and then compare their spelling to the correct spelling. If they spelled the word correctly, the interventionist praised the students’ response before they moved on to the next word. If they spelled the word incorrectly, they repeated the CCC procedure from the beginning for the misspelled word until they spelled it correctly. Participants’ effort was praised after completing this procedure for all five words in the word list.

Although sounding out was a required step in the CCC+SO condition, it was important to attempt to prevent sounding out during CCC. One step that was taken to help do this was to explicitly tell the participants before each session that they were not to use the sounding-out method. During the session, the interventionist was required to listen to the participants as they completed the CCC procedure to try to make sure they were not sounding out. Additionally, the interventionist watched the participants’ mouths to look for subvocal sounding out. If any of the participants did sound out during the intervention session, they were stopped and given the instruction, “Remember, don’t sound out any of these words.” Anecdotally, prompts to address sounding out were needed infrequently.

CCC+SO

This practice condition was exactly the same as CCC with the following exception. An additional step was required in which participants were instructed to vocally sound out each phoneme of the word before they covered it up. The interventionist reminded each participant to use the sounding-out method before each session by using the prompt, “Remember to sound out all of these words out loud, so I can hear you.” If any of the participants did not sound out during the intervention session, they were stopped and reminded using the previous instruction. Another error that could arise was that participants might sound out words incorrectly. If this error occurred, the interventionist corrected the error by immediately modeling the phoneme that was pronounced incorrectly.

Interobserver Agreement

To demonstrate that the dependent variable was measured consistently, interobserver agreement (IOA) was documented by percentage agreement between observers on at least 20% of sessions for each participant (Kratochwill et al., 2010). Observers looked at the participants’ written responses on retention tests and independently scored them as correct or incorrect. Both score sheets were evaluated item by item to calculate IOA. The number of agreements between observers was divided by the total number of items and then multiplied by 100% to obtain percentage agreement.

IOA for Angela’s sessions was measured on 77% of all sessions with 99% agreement in scoring. IOA was measured on 74% of Bobby’s sessions with 100% agreement in scoring. Finally, IOA for Stephanie’s sessions was measured on 27% of all sessions with 100% agreement in scoring.

Treatment Integrity

To ensure that both intervention conditions were carried out correctly and consistently, interventionist behavior and participant adherence were examined by a secondary observer using a checklist created for the current study. The observer used the checklist to rate the occurrence of each treatment component to calculate the percentage of treatment integrity. Each day, the observer rated whether the intervention took place (a) in the designated setting and (b) at the appropriate time. For each session per day, the observer rated whether (a) the participant was provided with the appropriate materials, (b) instructions were provided indicating which condition was occurring prior to the intervention commencing, and (c) appropriate reminders were given regarding use of the sounding-out step. The final set of steps was rated as occurring if completed correctly on 80% of trials per session per day. These involved rating whether participants (a) took time to study the word, (b) covered the word list, (c) copied the word, (d) uncovered the word list, and (e) engaged in error correction contingent on an incorrectly spelled word.

An observer completed the checklist for 23% of Angela’s sessions, for which 100% treatment integrity was calculated. The checklist was completed by an observer for 22% of Bobby’s sessions with 100% treatment integrity. Finally, an observer completed the checklist for 27% of Stephanie’s sessions, for which 97% treatment integrity was calculated.

Social Validity

The teachers and participants were administered questionnaires to measure intervention acceptability. Despite not directly implementing the intervention, teachers were familiar with the study’s procedures and the progress of their students. Two teachers completed an adapted version of the Intervention Rating Profile–15 (IRP-15; Martens, Witt, Elliott, & Darveaux, 1985). The rating scale consists of 15 items on a 6-point Likert-type scale with options ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Higher scores indicate higher acceptability of the current intervention. Von Brock and Elliot (1987) noted a raw score of 52.5 is suggestive of an acceptable intervention. To modify the original IRP-15, the words “problem behavior” were changed to “spelling difficulties” to make the items more relevant to the current study.

Student questionnaires were an adapted version of the Kids Intervention Profile used in a study by Hier (2012). The Kids Intervention Profile used by Hier (2012) was itself an adapted version of the Children’s Intervention Rating Profile (CIRP; Witt & Elliott, 1983). The rating scale consists of eight items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale with options ranging from not at all to very much. In addition to these items, participants were asked to rate how much they liked practicing spelling with and without sounding out on the same 5-point Likert-type scale.

Results

Short-Term Retention Tests

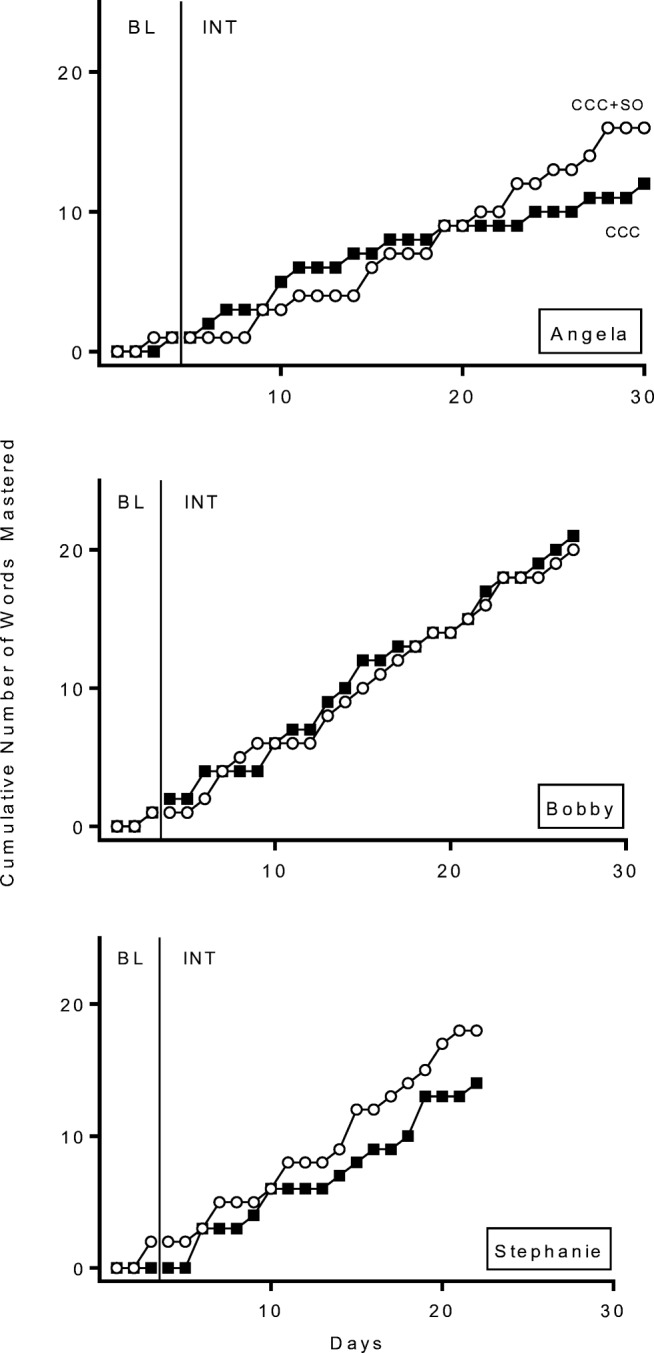

Figure 1 shows the cumulative number of spelling words mastered in each condition for Angela, Bobby, and Stephanie. These data were based on accurately spelling words correctly on three consecutive short-term retention tests. During baseline, participants mastered between zero and one spelling word per condition. When intervention was implemented, all three participants demonstrated considerable growth in the number of words mastered. Angela’s performance in Fig. 1 indicates that, across conditions, she maintained fairly equal and consistent performance until about halfway through the intervention phase. The data begin to show a separation between performance in the CCC and CCC+SO conditions, with the latter indicative of faster acquisition. Overall, she mastered four more words in CCC+SO than in CCC. Unlike Angela’s data, Bobby’s data do not demonstrate any discernable difference between CCC and CCC+SO. He maintained nearly equal and consistent performance throughout the duration of the intervention phase. Similar to Angela, Stephanie’s performance initially was consistent across conditions. Her performance began to demonstrate a separation between the slopes of the CCC and the CCC+SO lines after 10 days of intervention, with the slope of CCC+SO being slightly steeper. She mastered four more words in CCC+SO than in CCC.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative number of words mastered in CCC (black squares) and CCC+SO (white circles) by participant; BL = baseline; INT = intervention

Long-Term Retention Tests

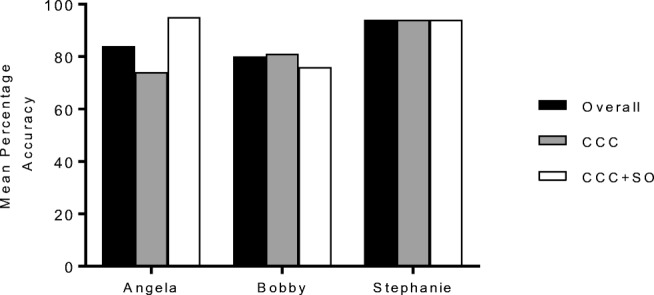

Performance on long-term retention tests is shown in Fig. 2. The average percentage of words spelled correctly on long-term retention tests ranged from 80% to 94%. Participant performance does not appear to indicate any considerable difference across conditions in spelling of previously mastered words. Angela’s mean percentage of words spelled correctly was slightly higher for words assigned to the CCC+SO condition than the CCC condition, with an overall average of 84%. Bobby and Stephanie performed consistently across conditions with an overall average of 80% and 94% over time, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Mean percentage accuracy on long-term retention tests overall (black), with CCC (gray), and with CCC+SO (white) by participant

Incorrect Responses

Incorrect responses during intervention sessions were also recorded. Participants demonstrated different patterns of incorrect responses across conditions. Angela’s performance during intervention sessions indicates a higher number of errors in CCC (28) than in CCC+SO (9). Bobby made an almost equal number of errors during practice conditions in CCC (31) and CCC+SO (32). Stephanie’s performance during intervention sessions indicates a higher number of errors in CCC+SO (14) than in CCC (3).

Social Validity

The two teachers that participated in the current study completed an adapted version of the IRP-15 (Martens et al., 1985) to provide data on their perceptions of intervention acceptability. Both teachers rated the intervention as acceptable according to the criterion proffered by Von Brock and Elliot (1987; i.e., both had raw scores greater than 52.5). The teacher for Angela and Bobby had a mean item rating of 4.87 (range 4–6). He at least slightly agreed with all items. He strongly agreed the students’ difficulties were severe enough to warrant use of these interventions. Stephanie’s teacher had a mean item rating of 5.07 (range 5–6). She at least agreed with all items. She strongly agreed the interventions would not result in negative side effects for students.

To gain insight on the participants’ personal opinions of the study, participants completed an adapted version of the CIRP (Witt & Elliott, 1983). All three participants’ ratings indicated that they agreed the intervention had improved their spelling and that they enjoyed the methods used to improve their spelling performance. Mean item ratings for Angela, Bobby, and Stephanie were 5.00 (range 0), 5.00 (range 0), and 3.88 (range 3–5), respectively. When asked whether they preferred CCC or CCC+SO, ratings were inconsistent across participants. Angela rated CCC+SO higher than CCC, whereas Stephanie rated CCC higher than CCC+SO, and Bobby rated both methods equally.

Discussion

Refinements to CCC have been investigated to maximize its effectiveness and efficiency (Erion et al., 2009; Fisher, 2012; Mann, 2014; Mann et al., 2010). One such refinement is the addition of a sounding-out step, which is thought to capitalize on the reading repertoires of individuals with spelling difficulties (Fisher, 2012; Mann et al., 2010). Whereas Mann et al. (2010) showed CCC+SO was more effective than CCC, Fisher (2012) did not. Because of these inconsistencies, the current study sought to replicate and extend previous research while addressing some of its methodological limitations. All participants demonstrated considerable growth in the number of words mastered from baseline to intervention, both in the CCC and the CCC+SO conditions, but results indicated little to no difference in spelling performance across conditions. Although all three participants maintained mostly consistent mastery of words across conditions, Angela and Stephanie began to show a difference in the cumulative number of words mastered after several sessions. Both participants mastered more words when practicing with CCC+SO than when practicing with CCC. The third participant, Bobby, maintained nearly equal performance across conditions throughout the entirety of the intervention phase.

Performance on long-term retention tests indicated there was not a considerable difference across conditions. Bobby and Stephanie performed consistently on words assigned to the two conditions, whereas Angela showed a higher average spelling accuracy on words previously mastered in the CCC+SO condition than on words previously mastered in CCC. Data on incorrect responses during intervention sessions demonstrated that Angela made more errors in CCC than in CCC+SO, consistent with the rest of her performance. Bobby also performed consistently with the rest of his performance by demonstrating an equal number of errors across intervention conditions. Stephanie’s performance during intervention sessions indicated a slightly higher number of errors in CCC+SO than in CCC.

Previous research has demonstrated that participants achieved considerably higher percentages of correctly spelled words when sounding out than following the CCC method (Mann et al., 2010). The results of the current study showed small differences in cumulative words mastered, favoring CCC+SO for two of three participants. The difference in results could be due to a procedural difference in the measurement of the primary dependent variable. Increases in spelling performance in the CCC+SO condition in the previous study could have been because participants were instructed to sound out words on the CCC+SO posttests but instructed not to sound out words on the CCC posttests. This procedural difference did not allow the researchers to conclude whether differences in performance were solely due to how words were practiced. To this end, participants in the current study spelled words on retention tests without using the sounding-out strategy. Given the results of the current study, the effectiveness of CCC+SO may be maximized only when students are allowed to use the sounding-out strategy in testing situations. Using the sounding-out strategy in testing situations may serve to enhance the salience of cues that evoke a correctly spelled word compared to only using it during intervention sessions that were 24 h or more removed from testing situations.

This study adds to the large body of research demonstrating the benefits of CCC on spelling performance for children with and without disabilities. Both CCC and CCC+SO led to considerable increases in spelling words mastered for all three participants in the current study. Further, data suggest the sounding-out variation and the traditional method may be equally effective. Generally, in terms of academic intervention for students in schools having difficulty spelling, the sounding-out refinement may not be any more effective than CCC itself. Because students tend to prefer sounding out, it is likely that the sounding-out refinement may be helpful for young students. It was noted that the spelling curriculum being used with two students in this study were teaching words that followed general spelling rules. In other words, the words were decodable and could therefore be used in a CCC+SO intervention effectively. Furthermore, words with common spelling patterns were grouped together and taught each week. Consistent and repeated practice combined with sounding out, as can be found in CCC+SO, may be an effective way for students to master these words. On the other hand, the curriculum being used with the third participant included a number of words that do not follow general spelling rules. Future interventions should focus on the decodability of the spelling words being taught and on the phonological awareness abilities of the student prior to determining whether CCC or CCC+SO would be more appropriate for the student.

There were several limitations to the current study. The first limitation involves the risk of carryover effects. Although the procedures put in place to include prompting and frequent reminders about sounding out likely decreased the potential for carryover effects, there is no way to know for certain if participants were sounding out words covertly when practicing words in the CCC condition. Second, there was no procedure in place to measure the frequency of prompts necessary to remind participants to sound out, to not sound out, or to correct an incorrect sound during intervention sessions. Because CCC is a self-managed and independently carried-out intervention, it is important to know if CCC+SO can be carried out independently without making sounding-out errors. Anecdotally, this did not occur often, but data would support this further. Third, general praise statements were delivered to each participant by each interventionist without a procedure for systematic feedback during intervention sessions. Although unlikely, a systematic method for delivering feedback across participants would ensure the amount of praise given is equal across participants and across conditions, while removing the potential for responding that is influenced by differing amounts of praise. Fourth, pretesting of unknown words only occurred at the beginning of the study rather than periodically throughout the study. It is possible that after a word was identified as unknown during pretesting, words could have been indirectly mastered by practicing the spelling of other similar words. Periodically pretesting words before adding them to the intervention sessions could provide a more accurate measure of words directly mastered through the use of CCC and CCC+SO. Finally, though there was a procedure in place to screen participants’ ability to produce the most common sound for all 26 letters of the alphabet in isolation, more advanced reading skills were certainly needed to capitalize on the sounding-out step. We did not assess whether participants demonstrated such skills, and it is possible they did not have certain prerequisite skills in place to maximally profit from the sounding-out step.

Future research may consider evaluating the effects of CCC+SO by including it in a class-wide setting. Many classrooms use a daily spelling rotation that includes spelling with scrabble; grouping words with common endings, consonant blends, and digraphs; and using words in sentences. Adding CCC+SO as part of the students’ daily spelling rotation may provide a class-wide example of its effectiveness, while gathering information on the intervention’s perceived acceptability from both teachers and students. Also, an important area of all intervention research may be to assess the extent to which the words mastered during intervention sessions can be generalized into other written expression activities. Future research could conduct an analysis of written exercises that were completed in the classroom to gather data about the generalization of words learned using CCC+SO. Future research may also consider a different method to measure efficiency of the practice conditions to determine if CCC+SO is more efficient than CCC. This could be done by measuring the length of time needed to complete intervention sessions in each condition.

Implications for Practice

CCC is a commonly used academic intervention used to promote skill acquisition and fluency in various content areas (e.g., math, spelling).

We extended work on a refinement to CCC thought to capitalize on student reading repertoires to promote spelling word acquisition. The refinement involved students sounding out words prior to spelling them.

Two of three participants acquired more spelling words when practicing with this refinement compared to CCC as it is usually implemented, but the difference across conditions was modest. Further research is necessary before educators can assume that adding a sounding-out step will enhance the effectiveness of CCC.

In selecting whether to implement CCC with sounding out, practitioners may consider the type of words being taught. If spelling words are decodable, it may be a helpful refinement to implement, provided students have the prerequisite phonics skills to sound out words. Often though, spelling words are not decodable, rendering CCC with the sounding-out step impractical.

Researchers may consider investigating the effectiveness, efficiency, and social validity in a group format, as well as the generality of words acquired via CCC or CCC with sounding out.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Bailey Chapman with intervention implementation and data collection. The present study was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts at Central Michigan University.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from a parent of each individual participant included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alber S, Walshe S. When to self-correct spelling words: a systematic replication. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2004;13:51–66. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBE.0000011260.12674.a3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer A, Hughes C. Explicit instruction: effective and efficient teaching. New York, NY: Pearson; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carnine D, Silbert J, Kame’enui E, Tarver S. Direct instruction reading. 5. Boston, MA: Merrill; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Erion J, Davenport C, Rodax N, Scholl B, Hardy J. Cover-copy-compare and spelling: one versus three repetitions. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2009;18:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s10864-009-9095-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, H. (2012). Addition of a sounding-out step to cover-copy-compare for spelling (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarly.cmich.edu/.

- Fulk B, Stormont-Spurgin M. Spelling interventions for students with disabilities: a review. Journal of Special Education. 1995;28:488–513. doi: 10.1177/002246699502800407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Harris K, Fink-Chorzempa B. Contribution of spelling instruction to the spelling, writing, and reading of poor spellers. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2002;94:669–686. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hier, B. (2012). Generality of treatment effects: Evaluating elementary-aged students’ abilities to generalize and maintain fluency gains of a performance feedback writing intervention (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from http://surface.syr.edu/psy_thesis. Accessed 14 Dec 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hubbert E, Weber K, McLaughlin T. A comparison of copy, cover, and compare and a traditional spelling intervention for an adolescent with conduct disorder. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2000;22:55–68. doi: 10.1300/J019v22n03_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, L. M., Konrad, M., Cates, G., Vajcner, T., Eveleigh, E., & Fishley, K. M. (2012). A meta-analytic review of the cover-copy-compare and variations of this self-management procedure. Psychology in the Schools, 49, 122–136. 10.1002/pits.20622.

- Kratochwill, T., Hitchcock, J., Horner, R., Levin, J., Odom, S., Rindskopf, D., & Shadish, W. (2010). Single-case designs technical documentation. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/ReferenceResources/wwc_scd.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec 2018.

- Larsen S, Hammill D, Moats L. Test of written spelling. 5. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, T. (2014). A comparison of two spelling strategies with respect to acquisition, generalization, maintenance, and student preference (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global database. (UMI No. 3646993).

- Mann T, Bushell D, Jr, Morris E. Use of sounding out to improve spelling in young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:89–93. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens B, Witt J, Elliott S, Darveaux D. Teacher judgments concerning the acceptability of school-based interventions. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1985;16:191–198. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.16.2.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner C, McLaughlin T, Logan P. Cover, copy, and compare: a self-managed academic intervention across skills, students, and settings. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1997;7:295–306. doi: 10.1023/A:1022823522040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viel-Ruma K, Houchins D, Fredrick L. Error self-correction and spelling: improving the spelling accuracy of secondary students with disabilities in written expression. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2007;16:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s10864-007-9041-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Von Brock MD, Elliot SN. Influence of treatment effectiveness information on the acceptability of classroom interventions. Journal of School Psychology. 1987;25:131–144. doi: 10.1016/0022-4405(87)90022-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witt J, Elliott J. Children’s intervention rating profile. Lincoln: University of Nebraska; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Worsdell A, Iwata B, Dozier C, Johnson A, Neidert P, Thomason J. Analysis of response repetition as an error-correction strategy during sight-word reading. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:511–527. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.115-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]