Abstract

Token systems often involve a predetermined number of tokens required prior to exchange for a terminal reinforcer. The effectiveness of token systems implemented in this manner has been well documented within the literature; however, some have discussed the possibility of a fixed earning requirement creating a context in which the learner no longer emits the desired behavior once the terminal number is achieved. A possible alternative to a fixed earning requirement is selecting the earning requirement based upon learner responding and leaving the requirement unknown to the learner until the moment of exchange. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a token system with a flexible earning requirement to increase the frequency of comments during snack for 3 children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. The results of a nonconcurrent multiple-baseline design demonstrated the flexible token system was effective at increasing the rate of comments in addition to the cumulative number of novel comments.

Keywords: token system, flexible, shaping, commenting, autism

A token economy is a contingency system in which tokens are earned for engaging in desired behavior that can be exchanged for presumably reinforcing items or activities. Token economies are commonly used in behavioral intervention to improve desired behavior and decrease the probability of undesired behavior (Hackenberg, 2018; Kazdin, 1977; Matson & Boisjoli, 2009). Ayllon and Azrin (1965) first described the use of a token economy with residents in a state hospital; however, they had been developing and modifying the procedures since 1961 (Ayllon & Azrin, 1968). Ayllon and Azrin (1965) provided tokens to residents contingent upon the resident displaying a predetermined behavior (e.g., self-grooming, doing laundry). The tokens earned by each resident could then be exchanged for a variety of activities (e.g., walking around the hospital grounds). The results demonstrated that the token economy was effective at developing and improving adaptive behavior for all of the participants.

Since the seminal work of Ayllon and Azrin, token economies have been used to improve or develop a variety of behaviors for a wide population of individuals. These populations include, but are not limited to, children and adults diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), typically developing children, and adults and children diagnosed with intellectual and developmental disabilities other than ASD. Token economies have been demonstrated to be effective at improving or developing many different target behaviors, including, but not limited to, rates of studying (Birnbrauer, Wolf, Kidder, & Tague, 1965), class participation (Cotler, Applegate, King, & Kristal, 1972), social interactions (Odom, Hoyson, Jamieson, & Strain, 1985), self-help skills (Murphy, 1976), question asking (Hung, 1977), attending (Jones & Kazdin, 1975), and food refusal (Kahng, Boscoe, & Byrne, 2003).

Given the widespread use and effectiveness of token economies, some have developed guidelines for the development and maintenance of token economies. Ghezzi, Wilson, Tarbox, and MacAleese (2008) provided some guidelines in their discussion of token economies. First, given that the purpose of a token economy is to change an individual’s behavior, it is important to define the target behaviors clearly. Ghezzi et al. also stressed the importance of specifying the settings in which the token economy will and will not be used. Additionally, when selecting the stimuli that will be used as tokens, selection should take into account durability, ease of handling, and ease of storage. Given that tokens should function as conditioned (and, sometimes, generalized) reinforcers, it is important to identify backup reinforcers that are effective (Ghezzi et al., 2008). It is also necessary to determine the schedule of reinforcement. This includes how many tokens will be delivered for the desired behavior(s) and how often tokens should be given contingent upon the desired behavior(s). The use of a token economy also requires that an earning requirement is established that “specifies exactly how many tokens are needed to buy exactly how much or how many of the things and activities that constitute the backups” (Ghezzi et al., 2008, p. 568).

Determining a schedule of reinforcement and establishing an earning requirement for a token economy can create challenges for the clinician. Specifically, with respect to establishing the earning requirement, “when a person earns as many or more tokens than are needed to exchange for a backup, there is no reason for him to continue working and earning additional tokens” (Ghezzi et al., 2008, p. 558). That is, a fixed earning requirement could create a context in which the learner no longer emits the desired behavior once the terminal number is achieved. This could potentially be a problem for behaviors for which an artificial ceiling would be undesirable (e.g., commenting, following a peer, maintaining appropriate proximity). For instance, if a child’s target behavior is commenting to friends and the earning requirement is 10 tokens, once 10 tokens are earned, the child may no longer comment to her or his friends because the contingency has been met.

In our research and clinical work, we have advocated and evaluated systematic but flexible approaches to solving problems of everyday life (e.g., Leaf, Cihon, Leaf, McEachin, & Taubman, 2016; Leaf et al., 2016). Within this approach the interventionist is not governed by a predetermined protocol, such as a schedule of reinforcement, but instead uses in-the-moment assessment of several variables to make adjustments that take into account the current learner behavior and the context in which it occurs. It is possible that this approach could be applied within a token economy by allowing the interventionist to determine the earning requirement in the moment, as opposed to at the outset of the token economy. That is, the earning requirement would be determined by the interventionist at the moment of exchange and the learner would not know the required number of tokens until the moment of exchange. This would allow the interventionist flexibility to change the number of tokens required for exchange based on the learner’s previous and current responding.

It is possible that using a flexible earning requirement may be beneficial over a fixed earning requirement. First, without a predetermined earning requirement, the motivation to engage in the target behavior(s) would not be abolished once a certain number of tokens is obtained. Not preestablishing an earning requirement and allowing the interventionist to change the rate based on learner responding could potentially eliminate the challenge Ghezzi et al. (2008) discussed. Second, this approach may be well suited for behaviors that should not have an artificial ceiling. Not stating the earning requirement could function as an establishing operation, momentarily increasing the probability of behavior that would set the occasion for token delivery. Third, allowing the interventionist flexibility to determine the earning requirement in the moment could align closer to the use of shaping behavior in real-world contexts (Cihon et al., 2018). Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a token economy with a flexible earning requirement on the rate of commenting during a snack context for three children diagnosed with ASD. In addition to child commenting, the interventionists’ rationales for selecting the exchange number were also evaluated to help identify the variables to which clinicians may be responding while implementing the token economy.

Method

Participants

Three children, each with a diagnosis of ASD, participated in the study. Each of the children were reported to have low rates of commenting during less structured times (e.g., snack, recess). Peter was a 4-year-old boy with an IQ of 75, a score of 77 on the Vineland-3 Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS-3; Sparrow, Cicchetti, & Balla, 2016), and a score of 80 on the Social Skills Improvement System (SSiS; Gresham & Elliott, 2008). Dana was a 6-year-old girl with an IQ of 75, a score of 75 on the VABS-3, and a score of 51 on the SSiS. Raymond was a 4-year-old boy with an IQ of 77, a score of 79 on the VABS-3, and a score of 90 on the SSiS. All three children could follow simple instructions, engaged in minimal challenging behavior, and had no previous experience with the token economy evaluated in this study.

Interventionists

Given the use of a flexible earning requirement (described later), the repertoires of the interventionists may be important for application and replication. The first author served as the interventionist during all sessions with Peter and Raymond and the second author served as the interventionist during all sessions with Dana. At the time of the study, the first author had an undergraduate degree in special education and a master’s degree in behavior analysis and was a doctoral student in an applied behavior analysis program. He had over 10 years of experience providing intervention based on the principles of behavior analysis for individuals diagnosed with ASD. However, he had limited to no experience providing intervention for any of the participants within this study. At the time of the study, the second author had an undergraduate degree in applied behavior analysis and a master’s degree in behavior analysis. She had over 6 years of experience providing intervention based on the principles of behavior analysis for individuals diagnosed with ASD. However, she had limited to no experience providing intervention for any of the participants within this study.

Setting and Materials

All sessions were conducted in one of two rooms located within a clinic that provides a progressive approach to intervention based on the principles of behavior analysis for individuals diagnosed with ASD (Leaf et al., 2016). Each room included a child-sized table, child- and adult-sized chairs, other furniture (e.g., desks, bookcases, and a couch), various instructional materials (e.g., toys, felt board, and computers), a video camera, a treasure chest, a dry-erase board and marker, and a timer. The toy treasure chest included various small, age-appropriate toys. These toys included, but were not limited to, bubbles, cars, foam dart guns, sidewalk chalk, bracelets, stickers, rings, and building blocks (prices ranged from $0.33 to $5.00). Sessions occurred once per day up to five times per week, based on participant availability. All sessions lasted approximately 5 min and were videotaped for scoring after each session.

Dependent Measures, Interobserver Agreement, and Treatment Fidelity

The main dependent measure within this study was participant comments. A comment was defined as any vocal response that included at least one intelligible word, separated from previous words by either at least 3 s or a clear change in topic (Groskreutz, Peters, Groskreutz, & Higbee, 2015). Novel comments were defined as the first instance of a comment that had not occurred in any prior session. The interventionists’ rationale for selecting the earning requirement, or what the interventionist and learners referred to as the magic number (i.e., the earning requirement that was only revealed at the moment of exchange), was also evaluated. Five predetermined rationales were provided for the interventionist to select from, which included (a) ensuring the participant contacted reinforcement, (b) ensuring the participant did not contact reinforcement, (c) basing selection on the previous session, (d) basing selection on the current session, and (e) the previous responses not meeting the magic number. The interventionists could also select “other” and write in a rationale that was not preprovided.

A second observer recorded child responding during 33% of sessions during each condition (i.e., baseline, intervention, and generalization) across all participants. Total count interobserver agreement (IOA) was used to calculate agreement for rate of comments (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). To calculate the IOA for rate of comments, the total number of comments recorded during each condition was calculated. The smaller total was divided by the larger number and multiplied by 100. IOA for rate of commenting averaged 100%, 100%, and 100% during baseline, intervention, and generalization across all participants, respectively. Trial-by-trial IOA was used to calculate IOA for novel comments. An agreement occurred anytime both observers scored the same comment, whereas a disagreement occurred anytime the observers scored different comments. IOA for novel comments averaged 100%, 90%, and 100% during baseline, intervention, and generalization across all participants, respectively.

To ensure treatment fidelity, an independent observer recorded the interventionists’ implementation of the token economy system during 33% of sessions across all participants in baseline, intervention, and generalization sessions. Correct interventionist behavior during baseline consisted of (a) providing a snack for the participant and the interventionist; (b) stating, “It is time for snack,” or something functionally equivalent; (c) setting a timer for 3 min; (d) responding with a neutral comment (e.g., “OK”) following each participant comment; and (e) ending the session following 3 min. Correct interventionist behavior during intervention consisted of (a) providing a snack for the participant and the interventionist; (b) explaining the token system (described later); (c) stating, “It is time for snack,” or something functionally equivalent; (d) setting a timer for 3 min; (e) responding with a neutral comment (e.g., “OK”) and a tally mark following each participant comment; (f) ending snack following 3 min; (g) counting the tally marks with the participant; (h) writing down the magic number; and (i) providing access to the treasure chest only if the participant met or exceeded the magic number. Correct interventionist behavior during generalization sessions consisted of (a) providing each child a snack; (b) stating, “It is time for snack,” or something functionally equivalent; (c) setting a timer for 3 min; and (d) ending snack following 3 min. Treatment fidelity was calculated by totaling the number of correct interventionist behaviors and dividing by the total number of possible interventionist behaviors and multiplying by 100. Treatment fidelity averaged 100% during baseline, intervention, and generalization across all participants.

Experimental Design

A nonconcurrent multiple-baseline design (Watson & Workman, 1981) across participants was used to evaluate the effects of the flexible earning requirement token economy on commenting. Nonconcurrent multiple-baseline designs provide flexibility when conducting research in applied settings, such as this study, that a concurrent multiple-baseline design may not. Within a nonconcurrent multiple-baseline design, initial baseline phases are selected a priori and participants are randomly assigned to each baseline length as they become available. Baseline phases are carried out as assigned, assuming stability in performance is observed. With respect to this study, participants progressed from baseline to the intervention condition once a stable level of commenting was observed during baseline. However, in an attempt to improve the strength of this design, an additional criterion common within multiple-baseline logic was added. If necessary, we extended baseline sessions for the next participant until intervention effects were observed with the previous participant. As such, experimental control is demonstrated when the intervention results in changes in a participant’s behavior without changes in the remaining participants’ behavior during baseline sessions (Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968; Carr, 2005). Also, although the nonconcurrent multiple-baseline design allows for participant removal if stable responding is not obtained, no participants were removed from this study for this reason.

General Procedure

Sessions occurred once per day up to 5 days per week and lasted 3 min. All sessions occurred in a one-on-one instructional arrangement. The study consisted of three conditions: baseline, intervention, and generalization.

Baseline. During baseline, and prior to the participant entering the room, the interventionist arranged two plates or bowls of a small snack and placed a dry-erase board, marker, and timer on the table. Snack food items consisted of Goldfish® crackers, Cheez-It® crackers, animal crackers, and/or Cheerios™ cereal. When the participant entered the room, the interventionist greeted the participant and instructed him or her to sit down. The interventionist labeled the snack items and offered the participant a choice between the two snack foods that were available. The participant was then given the snack food, and the interventionist said, “It is time for snack,” followed by starting a timer for 3 min. If the participant engaged in any comments, including questions, during the 3 min while the participant and the interventionist were eating the snack, the interventionist responded with a neutral comment (e.g., “OK,” “I see,” “Thanks”). No programmed reinforcement for comments occurred during baseline. When the 3 min expired, the interventionist told the participant that snack was done, thanked him or her for coming to snack, and returned the participant to his or her regular session.

Intervention. During intervention, the presession arrangement was similar to baseline (i.e., snack food items and materials). Once the participant was given, or selected, a snack, the interventionist explained the token system by stating,

Today we are going to work on talking. Each time you talk, I will give you a mark [interventionist put a mark on the dry-erase board]. If you have enough marks to meet or beat my magic number [interventionist drew a circle on the dry-erase board], you can take something home from the treasure chest [interventionist pointed to the treasure chest].

In an effort to ensure the participants understood the system, the interventionist occasionally required the participants to respond to various aspects of the explanation (e.g., “What happens if you beat my magic number?”). If the participant had no prior experience with the treasure chest used in this study, the interventionist briefly showed the participant the inside of the treasure chest on the first session of the intervention condition. Following the explanation, the interventionist stated, “It is time for snack,” and started a timer for 3 min.

If the participant made a comment during the 3 min, the interventionist responded with a neutral comment (e.g., “OK,” “I see,” “Thanks”) and put a tally mark on the dry-erase board. When the 3 min elapsed, the interventionist removed the participant’s snack and said, “Let’s see if you met or beat my magic number.” The interventionist then counted the tally marks and, if the participant was able, had the participant count with him or her. The interventionist then wrote down his or her magic number and asked the participant if he or she met (or beat) the magic number. If the participant met or beat the magic number, he or she was then given access to the treasure chest to pick an item to take home. If the participant did not meet or beat the magic number, the participant returned to his or her regular session.

Generalization probe. One generalization probe occurred following baseline, prior to intervention, and one generalization probe occurred following intervention. Generalization probes were similar to baseline with four notable differences. One, the 3-min snack occurred with a similar-aged peer (i.e., a peer that was the same age as the participant who was also receiving behavioral intervention at the clinic at which the participants were receiving intervention) instead of with the interventionist. Two, the dry-erase board and marker were not present during snack. Three, the interventionist was present in the room but remained on the opposite side of the room during the 3 min. Four, the interventionist did not respond in any way if the participant commented during the 3 min.

Results

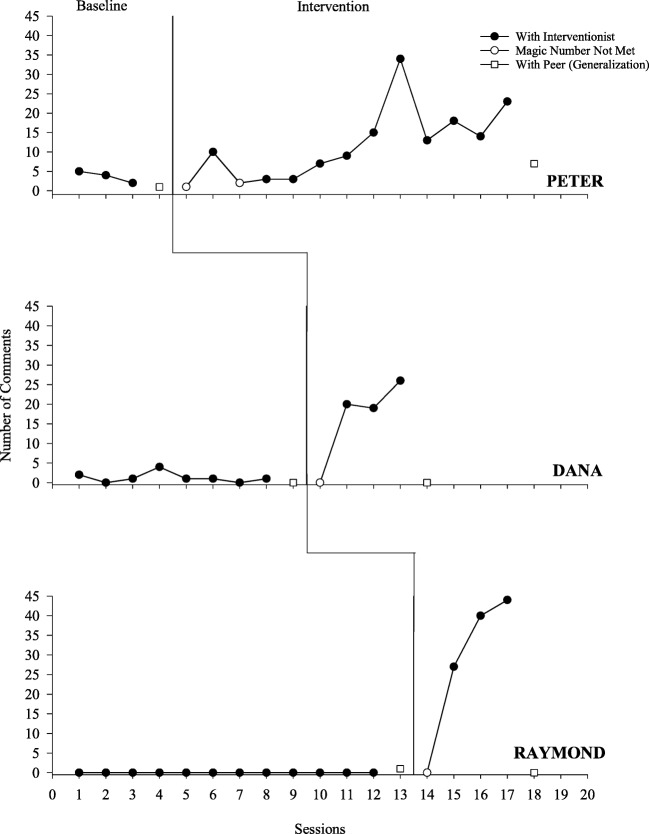

Figure 1 displays the rate of comments for each participant during baseline, intervention, and generalization probes. Closed circles indicate when the participant met or beat the interventionist’s magic number, and open circles indicate when the participant did not meet the interventionist’s magic number. Low rates of commenting were observed across all participants during baseline. Peter had a decreasing rate of commenting across his three sessions of baseline, Dana had variable but low to zero rates, and Raymond did not make any comments during baseline. During the first session of the intervention with the flexible token system, across all three participants there were low to zero rates of responding. As such, none of the participants met or beat the interventionist’s magic number. Following the first session, there was a gradual increase in the rate of commenting across all three participants. All participants with the exception of Peter met or beat the magic number on all but the first session of intervention. Low rates of commenting were also observed during the first generalization probe. Generalization of commenting during snack was only observed with Peter in the generalization probe following intervention, and the rate of Peter’s commenting during the second generalization probe was below the rate of commenting with the interventionist.

Figure 1.

Number of comments per session for each participant. Closed circles represent sessions with the interventionist, open circles (during intervention) represent sessions in which the magic number was not met, and open squares represent generalization sessions with a peer.

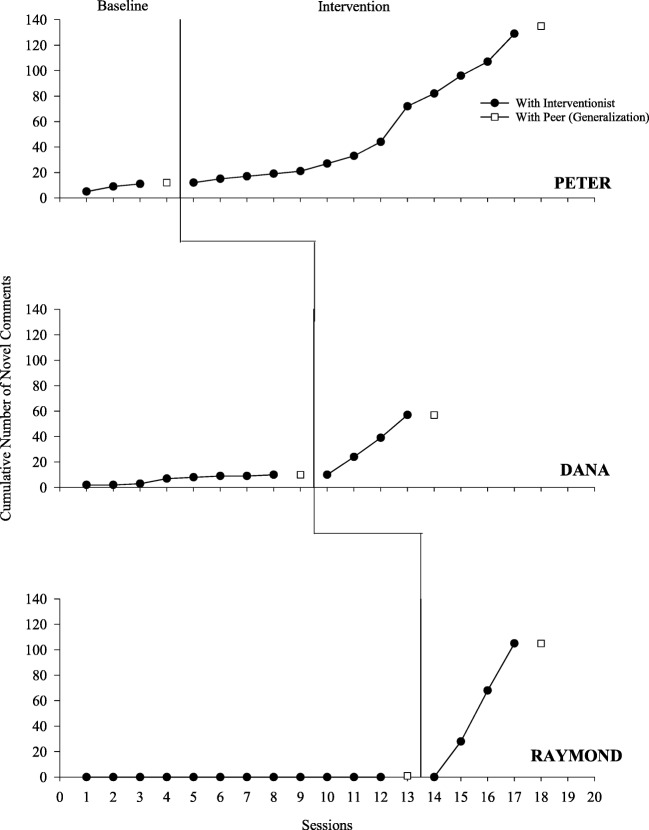

Figure 2 displays the cumulative number of novel comments for each participant during baseline, intervention, and generalization probes. Very few novel comments were observed during baseline across all three participants. Following the introduction of the flexible token economy system, there was a gradual increase in the cumulative number of novel comments for all three participants. This increase was observed even though novel comments were not required for the contingency to be met. That is, rate of commenting was the dependent measure, so the participants could have engaged in the same comment and still accessed programmed reinforcement (i.e., the treasure chest).

Figure 2.

Cumulative number of novel comments per session for each participant. Closed circles represent sessions with the interventionist, and open squares represent generalization sessions with a peer.

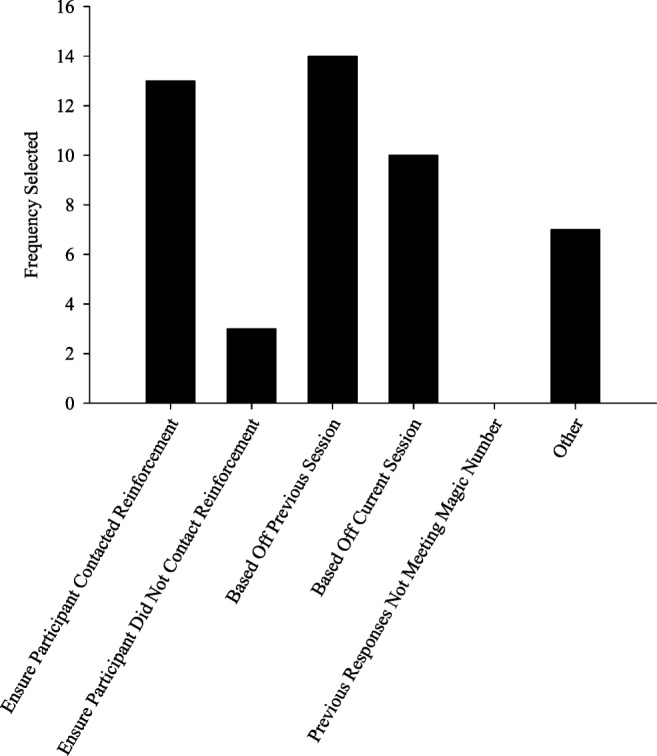

Figure 3 displays the number of times each rationale was selected by the interventionists. Multiple rationales could be selected each session, and each contributed to the overall total. The most commonly selected rationale was “Based off previous session,” which was selected 14 times by the interventionists. “Ensure participant contacted reinforcement” was selected 13 times and “Based off current session” was selected 10 times. “Other” was selected seven times across the two interventionists. The rationales provided when “Other” was selected were “Low levels of commenting,” “Highest number of commenting,” “High number and variability,” “To show how much he talked,” and “Beat my goal going into the session.” “Ensure participant did not contact reinforcement” was selected three times. “Previous responses not meeting magic number” was never selected.

Figure 3.

Interventionist rationales for selecting the magic number at the moment of exchange.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that a token economy in which the earning requirement is flexible and determined by the interventionist in the moment was effective at increasing the rate of commenting during snack with an interventionist for three children diagnosed with ASD. The rate of commenting for all three children during baseline remained low until the intervention began. Generalization of commenting to a peer was only observed with one of the three participants. Interventionists’ rationales for the magic number also indicated that the most common variable to which the interventionists were responding was the child’s behavior in the previous session. The limitations and implications of this study can be discussed from at least two perspectives: research and clinical.

Research Limitations and Implications

To date, and to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate a flexible earning requirement within a token economy. Token economies have typically involved a fixed, closed-ended earning requirement that is determined prior to implementation (e.g., Donaldson, DeLeon, Fisher, & Kahng, 2014; Krentz, Miltenberger, & Valbuena, 2016). The present study demonstrates that token economies can be effective with a flexible earning requirement that is determined at the moment of exchange. However, given this is the first study to document the effectiveness, the results should be taken with caution and future research is needed to confirm these findings.

Relatedly, although this study demonstrates the effectiveness of a flexible earning requirement, it was not compared to a closed-ended token economy. There may be conditions under which a fixed earning requirement may be more effective or preferable; conversely, there may be conditions under which a flexible earning requirement may be more effective or preferable. Future researchers should conduct studies to help identify the benefits and limitations of fixed and flexible earning requirements with respect to different contexts and target behaviors.

The present study involved a structured, yet flexible approach that used in-the-moment assessment (sometimes referred to as clinical judgement). This approach creates replicability challenges for future researchers; however, research should continue to be conducted in this area. It will be important to conduct research to identify the variables that occasion interventionist behavior with respect to the child and the goals, as well as to identify the skills in interventionists’ behavioral repertoires. In an effort to identify these variables, we provided the interventionists with a set of predetermined rationales for selecting the earning requirement, or magic number, for each session. However, the interventionists provided rationales that were not made available a priori, indicating that there were additional potential variables to which the interventionists were responding. Future researchers should continue to identify these variables when conducting research using flexible approaches such as the one evaluated within the present study. Furthermore, researchers should continue to identify the experience level and competencies required to implement flexible approaches to teaching in order to help identify effective training procedures.

Hackenberg (2018) recently provided an in-depth discussion of the gap between basic and applied research on token systems. One limitation of applied research Hackenberg (2018) noted was that it is often unclear as to the variables that are responsible for the change. Although all of the particular variables responsible for the effectiveness of the token system evaluated within this study are not possible to assess in the current preparation, in an effort to help bridge basic and applied research, we will provide some possibilities that could be evaluated in future research. The first variable to be addressed is the token-production schedule (i.e., the contingency for earning tokens). The token-production schedule was held constant throughout this study at a fixed-ratio 1. That is, a token was provided each and every time a participant engaged in a comment.

The second, and not as clearly identified, variable is the exchange-production schedule (i.e., the earning requirement met to initiate an exchange). For example, exchanging only after 24 tokens have been earned (e.g., Staats, Staats, Schutz, & Wolf, 1962) represents an exchange production schedule of 24 (i.e., exchange only occurs following earning 24 tokens). The exchange-production schedule operating within the token economy system evaluated here is unclear; however, it is possible that it took advantage of a variable schedule, made most evident by the steady increase for all participants similar to that observed with variable ratio schedules. That is, the number of responses required to meet the requirement to access the terminal reinforcer varied based upon several variables assessed by the interventionists. It is also possible that the reinforcement schedule in effect was a progressive ratio schedule, in which the number of responses required to access the terminal reinforcer increased across time. Although both of these are possibilities, the preparation in the current study does not permit determining what schedule of reinforcement was in effect. Future research on token economy systems should attempt to evaluate the variables responsible for behavior change.

Finally, another variable potentially responsible for the effectiveness of the token system evaluated within this study is the token-exchange schedule (i.e., how often tokens are exchanged for the terminal reinforcer). This variable remained constant in that the opportunity for exchange occurred after 3 min had elapsed. It is possible that different exchange schedules would yield different results. Future researchers should evaluate the effects of different token-exchange schedules for fixed and flexible earning requirements.

Clinical Limitations and Implications

There are at least three limitations to the current study that relate to the clinical application of the procedures evaluated. First, although the flexible token economy system was effective at increasing the rate of comments within the snack setting, these results did not generalize to a snack with a peer for two of the three participants. However, this finding is not surprising given that generalization was not directly programmed. Generalization requires systematic planning (Stokes & Baer, 1977), and the procedures evaluated within this study did not systematically program for generalization. It is reasonable to assume that if this procedure is used within clinical application, clinicians would directly program for generalization (e.g., include the token system while the peer is present, use a peer during teaching). As such, if clinicians choose to adopt flexible token systems for any behavior, they should include a systematic plan for generalization of the behavior, as well as a plan for fading the use of the token system.

Second, the use of the flexible token economy was evaluated during relatively short durations (i.e., 3 min). In many cases, clinicians use token systems throughout an entire day. Although it is likely that the flexible token economy could be used across longer durations, until that research has been conducted, clinicians should be aware that the present study has not demonstrated the long-term utility of this flexible token system. Until future research evaluates the use of a flexible token economy across longer durations, clinicians should be cautious about using this token economy during longer periods of time.

Third, although an increase in the cumulative number of novel comments was observed across all three participants, these comments involved similar topographies or frames. For instance, a participant could make a comment such as “I like books” and only change the word “books” in future comments to meet the definition for novel comments. It should be noted that novel comments were not directly targeted within the present study. Nonetheless, if clinicians adopt this approach to teaching commenting during a snack, they should include a quality criterion.

There are at least two clinical implications relevant to the present study. First, this study demonstrated the effectiveness of a flexible approach to a commonly used behavioral system (i.e., token systems; Hackenberg, 2018). However, it is reasonable to assume that clinicians do not follow methods described within research to the letter but, rather, include some flexibility with respect to individualization for children with whom they work. It is important that researchers continue to evaluate procedures that permit this flexibility while maintaining a conceptually systematic, technological approach to research. In that light, the flexibility of the token economy evaluated within this study may be useful to clinicians as it allows individualization. Second, the flexible earning requirement of this token economy may be useful for clinicians who are targeting behaviors that should not have an artificial ceiling. It may be the case that traditional token systems with a static earning requirement can result in a cessation in responding once the terminal number of tokens is obtained. Using a flexible earning requirement could allow clinicians to prevent this problem for target behaviors, such as commenting, that should not cease just because the terminal number of tokens has been obtained.

Although there are several fruitful areas for future research addressing some of the limitations of this study, this study demonstrates the effects of a potentially powerful technique with a possible wide range of utility. This study also contributes to the growing number of studies evaluating structured, yet flexible approaches to ASD intervention (e.g., Cihon et al., 2018; Leaf et al., 2016; Leaf et al., 2017; Leaf et al., 2018). Ideally, researchers will continue to evaluate flexible procedures that may align closer to what is actually occurring clinically and yield optimistic results. This research will help to identify the variables to which clinicians are responding and provide clinicians with more flexible procedures that can be individualized dependent on the learner and implemented immediately.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sara M. Weinkauf and Todd Streff for their thoughtful discussions during the presentation of this manuscript at the California Association for Behavior Analysis 36th Annual Western Regional Conference and the 2018 Association of Professional Behavior Analysts Conference.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The corresponding author declares on behalf of himself and his coauthors that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

No grants were received to fund this project.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ayllon T, Azrin NH. The measurement and reinforcement of behavior of psychotics. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1965;8(6):357–383. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1965.8-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayllon T, Azrin NH. Reinforcer sampling: A technique for increasing the behavior of mental patients. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(1):13–20. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(1):91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbrauer JS, Wolf MM, Kidder JD, Tague CE. Classroom behavior of retarded pupils with token reinforcement. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1965;2(2):219–235. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(65)90045-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JE. Recommendations for reporting multiple-baseline designs across participants. Behavioral Interventions. 2005;20(3):219–224. doi: 10.1002/bin.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cihon, J. H., Ferguson, J. L., Leaf, J. B., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., & Taubman, M. (2018). Use of a level system with flexible shaping to improve synchronous engagement. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 10.1007/s40617-018-0254-8. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis. 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 2007. Contingency contracting, token economy, and group contingencies; pp. 550–574. [Google Scholar]

- Cotler SB, Applegate G, King LW, Kristal S. Establishing a token economy program in a state hospital classroom: A lesson in training student and teacher. Behavior Therapy. 1972;3(2):209–222. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(72)80081-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson JM, DeLeon IG, Fisher AB, Kahng S. Effects of and preference for conditions of token earn versus token loss. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47(3):537–548. doi: 10.1002/jaba.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi PM, Wilson GR, Tarbox RSF, MacAleese KR. Guidelines for developing and managing a token economy. In: O’Donohue WT, Fisher JE, editors. Cognitive behavior therapy: Applying empirically supported techniques in your practice. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. pp. 565–671. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social skills improvement system: Rating scales manual. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assessments; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Groskreutz MP, Peters A, Groskreutz NC, Higbee TS. Increasing play-based commenting in children with autism spectrum disorder using a novel script-frame procedure. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48(2):442–447. doi: 10.1002/jaba.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackenberg TD. Token reinforcement: Translational research and application. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2018;51(2):393–435. doi: 10.1002/jaba.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung DW. Generalization of “curiosity” questioning behavior in autistic children. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1977;8(3):237–245. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(77)90061-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RT, Kazdin AE. Programming response maintenance after withdrawing token reinforcement. Behavior Therapy. 1975;6(2):153–164. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(75)80136-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahng S, Boscoe JH, Byrne S. The use of an escape contingency and a token economy to increase food acceptance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36(3):349–353. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. The token economy: A review and evaluation. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Krentz H, Miltenberger R, Valbuena D. Using token reinforcement to increase walking for adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49(4):745–750. doi: 10.1002/jaba.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf, J. B., Cihon, J. H., Ferguson, J. L., McEachin, J., Leaf, R., & Taubman, M. (2018). Evaluating three methods of stimulus rotation when teaching receptive labels. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 10.1007/s40617-018-0249-5. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Leaf JB, Cihon JH, Leaf R, McEachin J, Taubman M. A progressive approach to discrete trial teaching: Some current guidelines. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education. 2016;9(2):361–372. [Google Scholar]

- Leaf, J. B., Leaf, J. A., Alcalay, A., Kassardjian, A., Tsuji, K., Dale, S., … Leaf, R. (2016). Comparison of most-to-least prompting to flexible prompt fading for children with autism spectrum disorder. Exceptionality, 24(2), 109–122. 10.1080/09362835.2015.1064419.

- Leaf, J. B., Leaf, J. A., Milne, C., Taubman, M., Oppenheim-Leaf, M., Torres, N., … Yoder, P. (2017). An evaluation of a behaviorally based social skills group for individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(2), 243–259. 10.1007/s10803-016-2949-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leaf, J. B., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., Taubman, M., Ala’i-Rosales, S., Ross, R. K., … Weiss, M. J. (2016). Applied behavior analysis is a science and, therefore, progressive. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(2), 720–731. 10.1007/s10803-015-2591-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matson JL, Boisjoli JA. The token economy for children with intellectual disability and/or autism: A review. Research in Developmental Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2009;30(2):240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ST. The effects of a token economy program on self-care behaviors of neurologically impaired inpatients. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1976;7(2):145–147. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(76)90073-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Odom SL, Hoyson M, Jamieson B, Strain PS. Increasing handicapped preschoolers’ peer social interactions: Cross-setting and component analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18(1):3–16. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow S, Cicchetti D, Balla D. Vineland adaptive behavior scales. 3. Bloomington, MN: NCS/Pearson; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Staats AW, Staats CK, Schutz RE, Wolf M. The conditioning of textual responses using “extrinsic” reinforcers. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1962;5(1):33–40. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1962.5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes T, Baer D. An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1977;10(2):349–367. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1977.10-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PJ, Workman EA. The non-concurrent multiple baseline across-individuals design: An extension of the traditional multiple baseline design. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1981;12(3):257–259. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(81)90055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]