Abstract

The field of behavior analysis relies on supervised fieldwork to shape the repertoires of individuals aspiring to sit for the Behavior Analyst Certification Board® (BACB®) exam. Board Certified Behavior Analysts® (BCBAs®) who are providing supervision to those seeking certification must follow the supervision and ethics requirements as directed by the BACB. We conducted a survey of BCBAs currently providing supervision to gather information about current practices and barriers. The top areas of success and need are presented based on the responses of 284 participants who completed the entire survey, along with recommendations.

Keywords: Certification, Fieldwork, Supervision, Supervisory practices, Trainee

The field of applied behavior analysis (ABA) relies on a supervision model to develop the skills required for an individual working toward becoming a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) to deliver effective services to consumers and to provide quality training and supervision of direct-line staff. Supervisors are responsible for managing all dimensions of the supervisory experience (Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], 2016, Code 5.0, p. 13). The BACB® requires that supervision of fieldwork hours be provided by qualified BCBAs (BACB, 2017a) and provides several requirements and resources to the field (e.g., training prior to supervising, an outline of what should be included in supervisor training, continuing education requirements). Upcoming additional requirements include course content focusing on supervision content (BACB, 2017c) and the requirement that new BCBAs cannot provide supervision to trainees within their first year, postcertification, unless they are supervised by a BCBA with 5 or more years of supervisory experience (BACB, 2017b).

Many helping professions rely on supervision as a way to model the expectations of the profession to practitioners (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). For the field of behavior analysis, relying on a supervision model allows for qualified practitioner-supervisors to directly shape the field by teaching and modeling critical knowledge and skills. However, reliance on a supervision model places a strain on supervisory resources, which is a concern given the rapid growth of the field. In a recent workforce outlook report, analysts found that the employment demand for BCBAs more than doubled from 2012 to 2014 (Burning Glass Technologies, 2015, p. 2). In fact, as of September 2018, the BACB reported that the number of BCBAs had reached 29,104 (BACB, n.d.). It should be noted that workforce growth and strain on resources are to be expected in a new field as it approaches a steady state of functioning.

In a recent study by DiGennaro Reed and Henley (2015), the authors surveyed 400 participants and found that 75% of respondents indicated they were responsible for supervising others, but a majority (54.71%) of their current employers did not provide training on effective supervisory practices. According to LeBlanc and Luiselli (2016), who wrote the introduction to a recent special issue on the topic of supervision in the journal Behavior Analysis in Practice, there is a dearth of available training for effective supervisory practices in the field of ABA. Because supervisors are charged with training and providing feedback to trainees, if those supervisors have not been trained on effective strategies for teaching and performance management, there is an increased risk that trainees will develop incomplete or faulty repertoires. In 2016, the BACB instituted the formal Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (the Code), which is enforced by them and can result in a number of consequences for a certificant if the BACB finds that the Code has been violated (BACB, 2016). The BACB recently reported that in the first year of enforcing the Code, the most prevalent code violation involved improper or inadequate supervision or delegation within the supervisory relationship (BACB, 2018).

Practitioners and researchers have responded to this growing need for resources. The aforementioned special issue included articles providing recommendations for establishing and carrying out effective individual supervision (Sellers, Valentino, & LeBlanc, 2016; Turner, Fischer, & Luiselli, 2016) and group supervision (Valentino, LeBlanc, & Sellers, 2016), and how to detect and address barriers that may arise within the supervisory relationship (Sellers, LeBlanc, & Valentino, 2016). Two articles provided descriptions of existing supervision models within provider agencies, along with feasible methods of ensuring the implementation of supervision in practice (Dixon et al., 2016; Hartley, Courtney, Rosswurm, & LaMarca, 2016). Another article reviewed the specific intersection between ethics and supervision (Sellers, Alai-Rosales, & MacDonald, 2016). Finally, since the publication of the special edition, Garza, McGee, Schenk, and Wiskirchen (2017) published an article focusing on recommendations for effective supervision and provided specific supplemental tools to support high-quality supervisory practices.

Whereas the existing articles offer recommendations, they are based on the collective experiences of the authors and their informed, albeit perceived, ideas regarding areas of need. It is currently unknown what practices supervisors are implementing and what barriers they might be experiencing in providing supervision. In a way, the field has placed the cart before the horse by not first evaluating the current state of supervisory practices. Gathering more information about actual supervisory practices and barriers will be useful as the field of ABA continues to develop. Specifically, data gathered from the field can help guide the development of needed resources to increase the quality of supervisory practices and afford increased consumer protection. The purpose of the current study was to gather information from BCBA supervisors about their current supervisory practices of trainees and barriers to implementing practices. Our goal was to identify areas of success and areas that should be targeted for improvement.

Method

Participants

This study focused on BCBAs and doctoral-level BCBAs (BCBA-Ds) presently providing supervision to those accruing supervised fieldwork hours toward applying to sit for the exam, per the BACB requirements. Participants were recruited through a combination of voluntary sampling and snowball sampling (Remler & Van Ryzin, 2011). We recruited participants through both national and state-level professional organizations and various social media sites (BACB e-mail blast, professional e-mail lists for behavior analysts, and Facebook sites for the Association for Behavior Analysis International, California Association for Behavior Analysis, and Utah Association for Behavior Analysis).

The number of individuals who received the invitation to participate is unknown; data tracking for this was not available. As this information was not available, a corresponding response rate was not calculated. Only those responses that were fully completed were included in the data analysis. A total of 480 responses were collected: 6 (1.2%) declined participation, 190 (38.8%) did not complete the entire instrument, and 284 (58%) fully completed the survey and were included in the data analysis.

Instrumentation

A survey was developed and piloted by individuals with both knowledge of supervision practices and experience in providing field-based supervision (these individuals were excluded from participation in the actual data collection phase). This survey was designed within Qualtrics (2017), a survey software tool with the ability to distribute and anonymously collect and analyze responses via the Internet. The instrument consisted of three sections: demographics, contemporary supervisory practices, and skills.

The questions in the second and third sections posed initial dichotomous questions (i.e., yes/no format) designed to assess contemporary supervisory practices and supervisory methods for trainee skill enhancement. Follow-up questions were contingent on the participant’s response to the initial question. Participants that responded in the affirmative were asked to clarify the specific techniques they employ related to the corresponding supervision skill. Participants who responded in the negative were asked to indicate barriers that kept them from completing or utilizing the supervisory task or skill.

Procedure

Invitation e-mails with the web address link for the surveys were distributed via an e-mail list. An invitation to participate with the corresponding survey link was also distributed through the aforementioned social media sites. Recruitment and data collection were conducted from July 1 through August 12, 2017.

Results

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 24. Analyses were limited to descriptive statistics. The results focus on demographics and selected practice areas. We chose to identify and present the top five successes and areas for improvement and the main barriers to implementing high-quality or recommended practices. We elected to do this because the survey was comprehensive; therefore, presenting all of the response data is impractical. Complete response data are available from the first author.

Respondent Demographics

Two hundred eighty-four respondents fully completed (100%) the survey. The sample was primarily female (n = 280, 81.0%), was White/Caucasian (n = 250, 88.0%), had been a BCBA for a mean of 8.39 years (range 1–40 years), and had provided supervision for a mean of 5.68 years (range 1–37 years). All 50 states were represented, with the largest representations from California (n = 38, 13.4%), Florida (n = 17, 6.0%), Massachusetts (n = 14, 13.4%), Texas (n = 14, 6%), and Michigan (n = 11, 3.9%), as well as 19 (6.7%) international respondents. Respondents reported having a mean of 2.95 trainees at any given time (SD = 2.46, range 0–20). The majority of respondents provided supervision through their work (n = 174, 61.3%), but some respondents indicated providing supervision through university settings (n = 50, 17.6%) and on a contractual basis (n = 54, 19.0%). Educational level was primarily reported at the master’s level (BCBA, n = 217, 76.4%). Sixty-five respondents (23.0%) identified having doctoral-level training (BCBA-D) and two respondents (0.7%) failed to report their educational level.

Top Five Areas of Success

Using a Contract

Of those surveyed, 97.2% (n = 276) indicated they use a formal contract in their supervisory practice, with 90% or greater indicating that the contracts included the following: (a) supervisor and trainee qualifications to enter into the supervisory relationship (per BACB Standards, n = 270), (b) documentation of expectations (n = 273), (c) amount and structure of supervisory activities (n = 258), and (d) contract review and signature completed by the first meeting (n = 249). Most respondents (85.1%, n = 235) indicated that their contract outlined caseload and experience responsibilities, and 76% or less indicated that their contract includes a section on client (n = 209) and/or workplace confidentiality (n = 211).

Evaluating Supervisor Capacity

When asked if supervisors considered the time requirements associated with supervision, in relation to their current responsibilities (e.g., supervisory and clinical caseloads), before adding trainees to their workload, 95.8% (n = 272) answered in the affirmative. Specifically, more than 85% indicated that they consider their current clinical caseload (n = 250) and supervisory workload (n = 249), whereas only 64.4% (n = 183) considered the trainee’s caseload. Additional considerations included time and logistics (e.g., geography, scheduling, work/life balance), matched skill sets, and “goodness of fit” or likely success of the supervisory relationship.

Setting Clear Expectations

The majority of respondents (95.8%, n = 272) indicated that they set clear expectations for their trainees, with 93.8% (n = 255) explicitly setting expectations around documentation and preparation for supervisory activities. A majority of respondents (70.6%, n = 192) indicated that they clearly communicated when praise and corrective feedback would be provided to the trainee.

Employing a Range of Performance Evaluation Strategies

Respondents (95.4%, n = 271) reported using a range of supervisory activities to measure trainee performance. See Table 1 for a breakdown of the reported implementation frequency of specific supervisory practices designed to measure competence in trainees. In terms of soliciting direct feedback from others about the trainee’s performance and completion of tasks, 84.2% (n = 239) of respondents do so. According to the respondents who seek out direct feedback, feedback was solicited from trainees (97.9%, n = 234), colleagues (65.7%, n = 157), and supervisors (45.6%, n = 109).

Table 1.

Supervisory activities specific to measuring competency

| Item | Frequency | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Office meetings | Never | 7 | 2.6 |

| Rarely | 26 | 9.7 | |

| Sometimes | 100 | 37.5 | |

| Most of the time | 94 | 35.2 | |

| Always | 40 | 15.0 | |

| Behavioral skills training | Never | 0 | 0.0 |

| Rarely | 13 | 4.8 | |

| Sometimes | 96 | 35.6 | |

| Most of the time | 117 | 43.3 | |

| Always | 44 | 16.3 | |

| Direct observation of direct and indirect work | Never | 1 | 0.4 |

| Rarely | 4 | 1.5 | |

| Sometimes | 58 | 21.5 | |

| Most of the time | 123 | 45.6 | |

| Always | 84 | 31.1 | |

| Reviewing written products | Never | 0 | 0.0 |

| Rarely | 12 | 4.4 | |

| Sometimes | 89 | 33.0 | |

| Most of the time | 91 | 33.7 | |

| Always | 78 | 28.9 | |

| Observing staff training | Never | 13 | 4.8 |

| Rarely | 36 | 13.4 | |

| Sometimes | 123 | 45.7 | |

| Most of the time | 59 | 21.9 | |

| Always | 38 | 14.1 | |

| Observing parent/teacher interactions | Never | 13 | 4.8 |

| Rarely | 40 | 14.9 | |

| Sometimes | 122 | 45.4 | |

| Most of the time | 57 | 21.2 | |

| Always | 37 | 13.8 | |

| Other | 40 | 14.8 |

Office meetings, n = 267; behavioral skills training, n = 270; direct observation, n = 270; reviewing written products, n = 270; observing staff training, n = 269; observing parent/teacher interaction, n = 269

Incorporating Ethics and Literature

A majority (90.8%, n = 258) of respondents reported that they include ethical scenarios and other activities to engage trainees in discussions about ethics. Respondents (45.1%, n = 116) reported using activities focused on the review of ethical scenarios at a majority of supervision meetings. When incorporating ethical scenarios into supervisory practices, the most common source of the examples was reported to be from the supervisors’ own personal experience (93.8%, n = 242). Other commonly reported resources include scenarios that the supervisor or colleagues have created (59.4%, n = 153), and 48.1% (n = 124) utilized scenarios from a published book on ethics (Bailey & Burch, 2011). Fifty-six (21.7%) respondents indicated that they use “other” sources, such as ethical scenarios in publications by professional organizations, real-life examples as they arise, and other books or publications. According to respondents, 56.6% (n = 146) sometimes observe trainees work through ethical scenarios, 21.3% (n = 55) do so often, 15.9% (n = 41) do so rarely, 4% (n = 11) do so almost always, and 1.9% (n = 5) never do so. Regular contact with relevant literature for review and guidance on supervision and clinical activities was reported by 95.8% (n = 272) of respondents. Clients’ needs (93.8%, n = 255) and professional development (92.3%, n = 251) were the most commonly reported focus for accessing the literature. Staff training (79.8%, n = 217) and supervisor practices (78.7%, n = 214) were the next most frequently reported reasons for going to the literature base.

Top Five Areas for Improvement

Setting Clear Expectations for Receiving Feedback

Just over half of the supervisors (52.9%, n = 144) indicated they clearly set expectations for how trainees should respond to corrective feedback. The commonly reported tools and systems used included documentation trackers or spreadsheets (tracking hours, forms, etc.; 89.9% n = 169), structured discussions on how to respond to corrective feedback (71.8%, n = 135), agendas (71.2%, n = 134), and timelines (68.6%, n = 129).

Conducting Ongoing Evaluation of the Supervisory Relationship

Ongoing evaluations of the supervisory relationship between supervisors and trainees were conducted by 59.5% (n = 169) of respondents. Activities reported to occur during reevaluation of the supervisory relationship included assessing the appropriateness of the frequency and structure of meetings (85.8%, n = 145), evaluating the relationship (81.1%, n = 137), and reviewing the contract (66.9%, n = 113). Eleven percent (n = 19) indicated “other,” which primarily included responses around evaluating the relationship (e.g., feedback, meeting needs) and goals.

Using Competency-Based Evaluations and Tracking Outcomes

When asked if they used competency-based evaluation tools linked to the BACB Task List, 78.9% (n = 224) of respondents indicated yes, and 96.4% (n = 216) of those respondents indicated that they make the competency list available to their trainees. The majority (60.7%, n = 136) of respondents reported using self-developed competency tools, 43.8% (n = 98) used tools developed by their employer, and 7.6% (n = 17) used commercially purchased systems. When evaluating competencies, respondents reported that they use direct training and mastery criteria (79.0%, n = 177), specific qualifications for each specific competency area (54.9%, n = 123), and specific quantifications for each area (52.7%, n = 118). Some respondents (8.5%, n = 19) indicated “other,” with responses indicative of direct observation methods and selecting an evaluation system based on the appropriateness of the relevant context.

According to responses gathered, 79.6% (n = 226) of respondents are actively tracking their trainees’ mastery of targeted skills. The most commonly reported method of tracking (72.1%, n = 163) was setting and recording instances wherein trainees met mastery criterion, followed by some type of data collection system (66.4%, n = 150). Graphic display of trainee competencies met was used by 26.5% (n = 60) of respondents.

Directly Assessing and Teaching Professionalism Skills

Of the respondents, 67.3% (n = 191) indicated that they measure their trainees’ interpersonal skills. With regard to communication skills, 67.3% (n = 191) of respondents reported that they measure these skills. Table 2 outlines reported ways in which interpersonal skills and communication skills were measured, as well as barriers to measuring these skills. When asked if respondents evaluate their trainees’ time management skills, 68.7% (n = 195) indicated that they do. Organizational skills were reported as measured skills by 67.6% (n = 192) of respondents. Prioritization skills were indicated as measured by 63.7% (n = 181) of respondents. Table 3 reflects the ways in which time management, organizational skills, and prioritization skills are measured, and Table 4 reflects the barriers to measuring these skills.

Table 2.

Measurement of trainees’ interpersonal skills

| Item | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal skills: Methods of measurement | Direct observation of real situations | 182 | 95.3 |

| Discussing scenarios | 142 | 74.3 | |

| Informal discussions | 138 | 72.3 | |

| Direct observation of role-plays | 74 | 38.7 | |

| Other | 17 | 8.9 | |

| Interpersonal skills: Barriers to measurement | This skill is difficult to measure. | 58 | 65.2 |

| There is a lack of understanding as to how to measure this across multiple skills. | 37 | 41.6 | |

| It is difficult to train this skill. | 18 | 20.2 | |

| There is a lack of time. | 24 | 27.0 | |

| I also lack this skill. | 3 | 3.4 | |

| This skill is not important to train. | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 14 | 15.7 | |

| Communication skills: Methods of measurement | Direct observation of real situations | 224 | 97.4 |

| Discussing scenarios | 181 | 78.6 | |

| Informal discussions | 174 | 75.7 | |

| Direct observation of role-plays | 101 | 43.9 | |

| Other | 22 | 16.9 | |

| Communication skills: Barriers to measurement | This skill is difficult to measure. | 28 | 57.1 |

| There is a lack of understanding as to how to measure this across multiple skills. | 20 | 40.8 | |

| There is a lack of time. | 19 | 38.8 | |

| It is difficult to train this skill. | 8 | 16.3 | |

| This skill is not important to train. | 1 | 2.0 | |

| I also lack this skill. | 1 | 2.0 | |

| Other | 11 | 22.4 |

Interpersonal skills and communication skills measured, n = 191; barriers to measuring interpersonal and communication skills, n = 89

Table 3.

Methods of measurements for self-management skills

| Item | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time management skills measured by | Practicing tasks that require this skill | 80 | 41.0 |

| Tracking their planned activities versus their actual activities | 115 | 59.0 | |

| Tracking deadlines (data actually submitted versus due date) | 176 | 90.3 | |

| Work/life balance | 93 | 47.7 | |

| Other | 12 | 6.2 | |

| Organizational skills measured by | Practicing tasks that require this skill | 77 | 40.1 |

| Documentation management | 166 | 86.5 | |

| Organization of client programming | 158 | 82.3 | |

| Organization of information and materials during meetings | 158 | 82.3 | |

| Other | 8 | 4.2 | |

| Prioritization skills measured by | Practicing tasks that require this skill | 82 | 45.3 |

| Organizing and adjusting tasks based on time sensitivity/deadlines | 151 | 83.4 | |

| Organization of information and materials reviewed during meetings | 145 | 80.1 | |

| Other | 14 | 7.7 |

Time management skills measured, n = 195; organizational skills measured, n = 192; prioritization skills measured, n = 181

Table 4.

Barriers to measuring self-management skills

| Item | Time management | Organizational skills | Prioritization skills | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| There is a lack of time. | 22 | 27.2 | 28 | 32.2 | 33 | 34.7 |

| There is a lack of understanding as to how to measure this across multiple skills. | 18 | 22.2 | 28 | 32.2 | 28 | 29.4 |

| I also lack this skill. | 7 | 8.6 | 5 | 5.7 | 6 | 6.3 |

| It is difficult to train this skill. | 12 | 14.8 | 11 | 12.6 | 16 | 16.8 |

| This skill is not important to train. | 2 | 2.5 | 4 | 4.6 | 6 | 6.3 |

| This skill is difficult to measure. | 32 | 39.5 | 42 | 47.1 | 42 | 44.2 |

| Other | 27 | 33.3 | 24 | 27.6 | 20 | 21.1 |

Barriers to measuring time management skills, n = 81; barriers to measuring organizational skills, n = 87; barriers to measuring prioritization skills, n = 95

Obtaining Feedback on Supervisory Practices

A slight majority (55.6%, n = 158) of respondents reported that they systematically track the effectiveness of their supervision. The primary method for tracking the effectiveness of supervision was obtaining a rating of the supervisory meetings from the trainee (57.6%, n = 91). Other methods reported include tracking data on self-selected goals (39.9%, n = 63), self-rating the supervision meetings (25.9%, n = 41), and having a peer or supervisor overlap their supervisory activities and provide them with feedback (24.7%, n = 39). Of those who solicit feedback, 38.1% (n = 85) do so through anonymous avenues.

Summary of Commonly Reported Barriers to Effective Supervisory Practices

There were several reported barriers that appeared across many of the topic areas. As one can imagine, one of the most commonly reported barriers to being able to implement high-quality supervisory practices was lack of time. Specifically, supervisors indicated that they lacked sufficient time to engage in thorough preparation for supervision meetings and to create systems for tracking mastery of content knowledge and skills. Other common barriers include cost-prohibitive materials (e.g., supervision curriculum) and lack of access to examples (e.g., contracts, systems for guiding supervision activities and for tracking competence). Supervisors also cited being unaware of certain requirements, such as the need to have a contract and to evaluate the effectiveness of their own supervisory practices.

With regard to assessing and teaching skills such as how to respond to feedback, time management, organization, and interpersonal communication, respondents frequently indicated that they felt they did not know how to measure or teach such skills. Others indicated that they felt it was not their job to teach those skills. This lack of ownership was also cited as a reason to not solicit feedback from trainees about the supervisory relationship, the trainee’s needs and preferences, and the supervisor’s performance.

Discussion

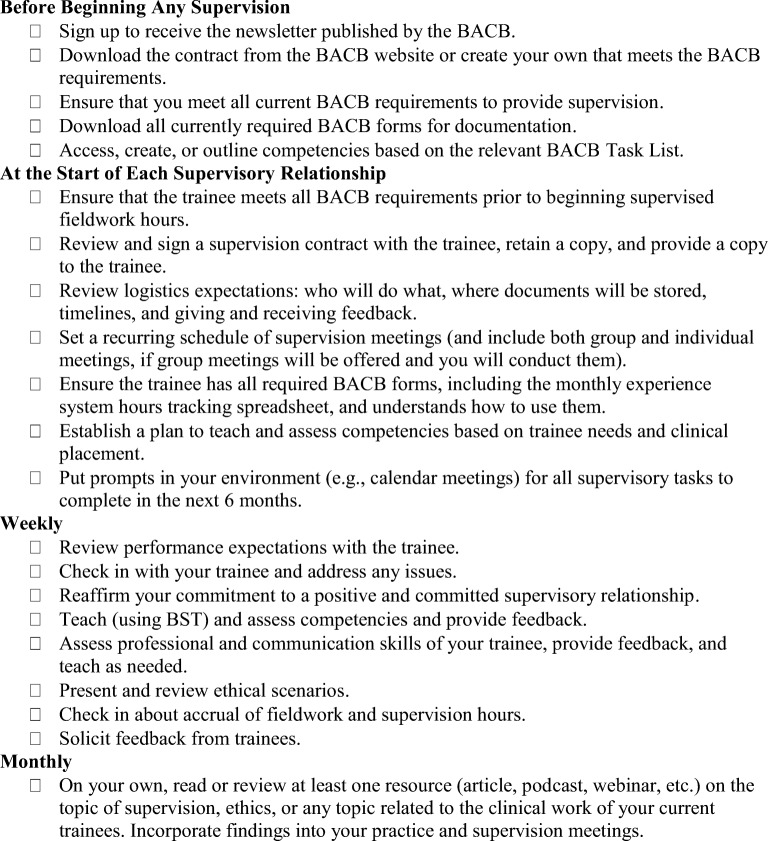

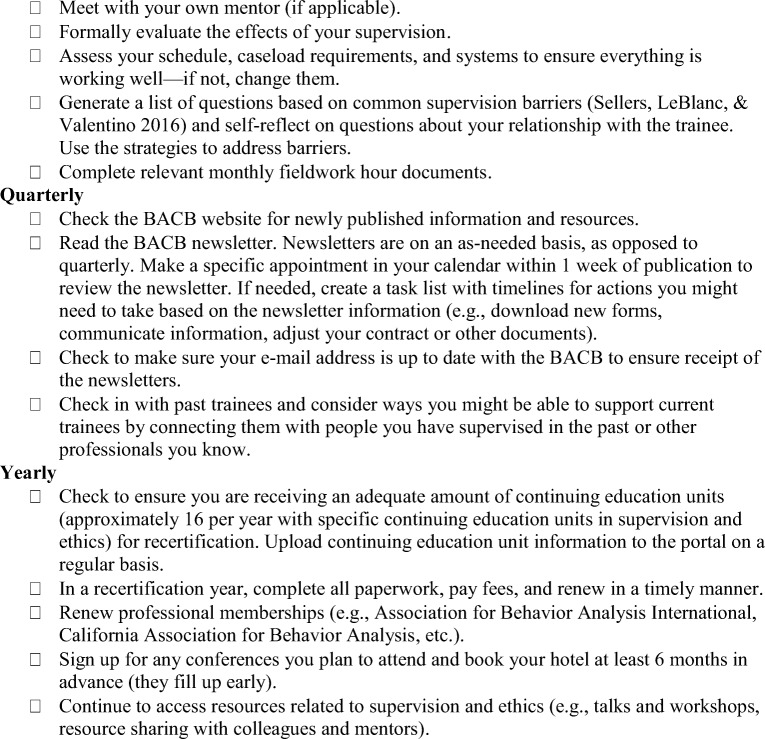

Behavior analysts are increasingly tasked with providing high volumes of quality supervision. This study extends the research on supervision by gathering information from BCBA supervisors about the practices they are currently implementing and barriers to implementing those practices. The results of this survey indicate that those supervising trainees in the field of behavior analysis are implementing many practices associated with high-quality supervision. At the same time, the results point to some areas wherein supervisors might require improvements. In the following section, we discuss the implications of the areas of success and need, as well as some recommendations. To that end, the Appendix is a sample supervisory to-do checklist for novice supervisors that is meant to ensure critical steps in the supervisory process are not overlooked.

It is encouraging that supervisors are complying with the BACB requirements related to using a contract, evaluating their supervisory capacity, and conducting performance evaluations. The majority of supervisors are also setting clear expectations for trainees and taking an active approach to including exposure to ethics and research literature. Consistently engaging in these supervisory activities provides several benefits. First, these behaviors provide greater protection to consumers receiving services from a trainee. Second, following these practices increases the likelihood that trainees will develop full and effective repertoires, not only for current and future clinical services, but also for when they assume a supervisory role. Finally, many of these practices minimize the development of issues during, and at the close of, the supervisory relationships (e.g., contractual disputes, disagreement over what a trainee or supervisor should have done). We encourage supervisors not only to keep up the good work but also to include direct instruction to trainees on why and how to engage in these practices to ensure that each new generation of supervisors is proficient in these practices.

Whereas a number of the results are encouraging, others are indicative of some areas in need of improvement. Supervisors of trainees accruing fieldwork hours can improve in some very specific areas of success listed previously. Communicating the purpose of corrective feedback, and the clear expectations for how to receive such feedback, may increase the effectiveness of supervisory practices with a given trainee. Doing so can also function as a model for the trainee to tackle difficult conversations and for how to begin with a strong supervisory relationship that focuses on feedback and growth. We recommend that supervisors and instructors of practicum courses have open discussions about expectations around how to receive feedback and what to do to incorporate the feedback into practice. Supervisors should also include instruction on how to deliver compassionate but effective corrective feedback, as many individuals never receive such instruction.

Supervisors can also incorporate evaluations of the supervisory relationship and can tact for the trainee why they are engaging in the check-ins. Readers are referred to the Sellers, LeBlanc, and Valentino (2016) article for suggestions on how to engage in periodic checks on the health of the supervisory relationship. We recommend generating a list of check-in questions to ask on a regular basis (e.g., weekly, monthly, quarterly). An even more direct route is to simply ask the trainee about his or her perceptions regarding the supervisory relationship. The very act of asking your trainee about his or her perceptions of the relationship may be one of the first and most critical steps in communicating the trainee’s value and establishing a strong supervisory relationship.

Another area for improvement is using a structured system to track trainees’ mastery of skills. Tracking progress toward mastery and maintenance of knowledge and skills is one of the primary ways to evaluate the effects of supervision, and literature supports the effectiveness of competency-based training (Parsons, Rollyson, & Reid, 2012; Reid, Parsons, & Green, 2012). Practicing behavior analysts would never think to provide services to a client without identifying the skills needed, measuring progress toward mastery, and making data-based decisions. Likewise, as trainees and students meet the definition of “client” in the BACB Code (BACB, 2016), instructors and supervisors should not attempt to build and shape repertoires outside of a competency-based framework within which progress can be measured and issues can be identified. We commend authors for publishing high-quality examples and supports for supervision and performance management (Carr, Wilder, Majdalany, Mathisen, & Strain, 2013; Garza et al., 2017; Kazemi, Rice, & Adzhyan, 2018; Theisen, Bird, & Zeigler, 2015; Turner et al., 2016). New supervisors might consider establishing communities of practice, wherein they can share resources and strategies. We also suggest that they reach out to previous instructors and supervisors, authors, and experts in the field to request unpublished resources and materials.

The responses related to questions about assessing and teaching a variety of professional skills suggest this as another area in need of improvement for the field. Successful clinical practice requires that BCBAs have a full repertoire of skills that allow them to conduct themselves in a professional manner. This requires individuals to possess effective communication and interpersonal skills and skills related to self-management, being organized, managing time, and prioritizing tasks. Therefore, it is critical that supervisors provide the opportunity to evaluate and develop these skills in their trainees to increase the likelihood that the individual is successful when practicing independently. Section 5.0 of the Code (BACB, 2016) directs the supervisor to accept “full responsibility for all aspects of this undertaking” (BACB, 2016, Section 5.0, p. 13).

We recommend that supervisors accept responsibility for developing and evaluating the full range of skills related to professionalism within the scope of supervisory activities. Employing evidence-based training strategies, such as behavioral skills training (BST), prompting and fading, and self-management strategies, will result in the effective acquisition of these skills. Readers can also find other helpful suggestions and resources in the article by Sellers, Valentino, and LeBlanc (2016). Supervisors can draft operational definitions of these skills and employ a variety of methods for measuring them. For example, supervisors can measure the percentage of deadlines met and the ability of the trainee to manage things like documents and client programming tasks and materials, the accessibility and organization of materials during supervision meetings, and the time allocated to tasks based on time sensitivity and deadlines. Other strategies include tracking the percentage of completed activities out of scheduled activities each day or week or the number of negative or defensive statements made per meeting.

The final area in which supervisors can improve is soliciting feedback about their own supervisory practices. This is critical for several reasons. First, when provided by the trainee, feedback provides valuable information about supervisors’ behavior and how they might make their supervisory practices more effective. Second, when solicited from others who are familiar with the trainee’s work (e.g., consumers, caregivers, staff working under the trainee), feedback provides a measure of the trainee’s skills and the effects of the supervision activities. Finally, soliciting feedback has been required by the BACB Code since 2016 (BACB, 2016). Implementing anonymous feedback systems is one way to increase the likelihood of respondents providing honest responses.

Supervisors can implement a wide range of systems for collecting anonymous feedback, from something as simple as having trainees print out their responses to questions and place them in a box or envelope, to using one of the many free online options for anonymous surveys. Anonymous methods are best suited for situations wherein the supervisor has several trainees (i.e., three or more); however, contexts in which there are only one or two trainees make anonymity more challenging. In such cases, the supervisor might directly explain this difficulty but highlight that it presents the opportunity for the trainee to learn to become comfortable providing high-quality feedback to their supervisor. A supervisor can begin to establish this repertoire by starting with the following structured approach: (a) select specific skills to be modeled for the trainee with some performance-planned errors; (b) provide the trainee with a procedural fidelity and feedback form; and (c) guide the trainee through scoring the form, identifying strengths and errors, and then providing high-quality feedback.

When evaluating the results, it is important that readers keep in mind that the data are self-reported. However, we recommend that these data serve as a call to practicing supervisors and instructors to thoughtfully and thoroughly evaluate the strengths and areas for improvement within their own practices.

These findings suggest that behavior analyst supervisors would greatly benefit from more formal education on supervision during their graduate training and their supervised fieldwork. Based on the data and fill-in answers from this survey, this education should involve exposure to a broad range of supervision practices, BST, and development of advanced mentoring skills about how to give effective feedback. In addition, teaching and supervision should focus on instructing behavior analysts on how to design systems for teaching, measuring, and evaluating a wide range of critical skills (behavior analytic and others, e.g., professionalism, effective communication and organization) and how to evaluate the effects of their supervisory practices. Based on the responses, as well as anecdotal data that many practicing supervisors are unaware of several required and beneficial practices, instructors and supervisors should consider including specific instruction about requirements and best practices using documents such as the Code (BACB, 2016), experience standards (BACB, 2017a), and BACB newsletters available on the BACB website.

Our field’s reliance on supervised fieldwork hours imparts an additional duty of care to ensure that clients receive effective services. Further, the reliance on supervised clinical experiences for trainees provides us with a valuable opportunity to impact not only those we directly supervise but also each person to whom our trainees may eventually provide supervision. Behavior analysts are often confident in their ability to be systematic, to collect data to measure behavior, and to respond to those data with clients. However, the present study suggests these repertoires may not generalize to supervision contexts. We hope these results will serve as a call to graduate training programs and clinical providers to explicitly provide instruction on taking a functional behavior-analytic approach to training and supervising trainees. Behavior analysts in supervisory roles should be able to fluently apply their behavior-analytic skills (operationally defining, measuring, and intervening on behavior) to supervision. We also hope the results of this study will help supervisors strengthen their supervisory practices and behavior.

Author Note

This article is not an official position of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board.

Appendix

Supervisor “To-Do” Checklist

This checklist is intended for use by supervisors providing supervision to individuals working toward becoming BCBAs® to serve as a basic starting point for individuals who may be new to supervision or for those who might want to revamp their current practice. It is meant to serve as a checklist of basic tasks that should be completed on a regular basis to ensure the provision of quality supervision, but it is not exhaustive.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Tyra P. Sellers declares that she has no conflict of interest. Amber L. Valentino declares that she has no conflict of interest. Trenton J. Landon declares that he has no conflict of interest. Stephany Aiello declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bailey, J., ∓ Burch, M. (2011). Ethics for behavior analysts: 2nd expanded edition. New York ∓ London: Routledge, Taylor ∓ Francis Group.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2016). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/wpcontent/uploads/2017/09/170706-compliance-code-english.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2017a). BCBA experience standards. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/wpcontent/uploads/BACB_Integrated_1710_experience_standards_english.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2017b). BACB October 2017 newsletter: Special edition on experience and supervision requirements. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/BACB_Newsletter_101317.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2017c). BCBA/BCaBA coursework requirements based on the BCBA/BCaBA task list (5th ed.). Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/170113-BCBA-BCaBA-coursework-requirements-5th-ed.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2018). A summary of ethics violations and code enforcement activities: 2016–2017. Littleton, CO: Author. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/180606_CodeEnforcementSummary.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.). BACB certificant data. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data

- Bernard JM, Goodyear RK. Fundamentals of clinical supervision. 5. Columbus, OH: Pearson Education; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Burning Glass Technologies. (2015). US behavior analyst workforce: Understanding the national demand for behavior analysts. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/151009-burning-glass-report.pdf

- Carr JE, Wilder DA, Majdalany L, Mathisen D, Strain L. An assessment based solution to a human-service performance problem. An initial evaluation of the Performance Diagnostic Checklist–Human Services. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2013;6(1):16–32. doi: 10.1007/BF03391789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGennaro Reed FD, Henley AJ. A survey of staff training and performance management practices: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8(1):16. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0044-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, D. R., Linstead, E., Granpeesheh, D., Novack, M. N., French, R., Stevens, E., . . . Powell, A. (2016). An evaluation of the impact of supervision intensity, supervisor qualifications, and caseload on outcomes in the treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 339–348. 10.1007/s40617-016-0132-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Garza KL, McGee HM, Schenk YA, Wiskirchen RR. Some tools for carrying out a proposed process for supervising experience hours for aspiring Board Certified Behavior Analysts®. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2017;11:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s40617-017-0186-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley BK, Courtney WT, Rosswurm M, LaMarca VJ. The apprentice: An innovative approach to meet the Behavior Analysis Certification Board’s supervision standards. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):329–338. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0136-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi E, Rice B, Adzhyan P. Fieldwork and supervision for behavior analysts: A handbook. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Luiselli JK. Refining supervisory practices in the field of behavior analysis: Introduction to the special section on supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:271–273. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MB, Rollyson JH, Reid DH. Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5(2):2–11. doi: 10.1007/BF03391819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics. (2017). (Version 11.2017 for Mac OS X Snow Leopard) [Computer software]. Provo, UT: Author. Available from: https://www.qualtrics.com

- Reid DH, Parsons MB, Green CG. The supervisor’s guidebook. Morganton, NC: Habilitative Management Consultants; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Remler DK, Van Ryzin GG. Research methods in practice: Strategies for description and causation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Alai-Rosales S, MacDonald RP. Taking full responsibility: The ethics of supervision in behavior analytic practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:299–308. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0144-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, LeBlanc LA, Valentino AL. Recommendations for detecting and addressing barriers to successful supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:309–319. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0142-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA. Recommended practices for individual supervision of aspiring behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:274–286. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theisen, B., Bird, Z., & Zeigler, J. (2015). TrainABA supervision curriculum—BCBA independent fieldwork. Los Angeles, CA: Bxdynamic Press.

- Turner LB, Fischer AJ, Luiselli JK. Towards a competency-based, ethical, and socially valid approach to the supervision of applied behavior analytic trainees. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:287–298. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA, Sellers TP. The benefits of group supervision and a recommended structure for implementation. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:320–338. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0138-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]