Abstract

Stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy is a label-free chemical imaging technique. Two-color imaging is necessary to determine the distribution of chemical species in SRS microscopy. Current multi-color SRS imaging methods involve complicated instrumentation, longer data acquisition time, or are limited to transmission imaging. We showed that by adding a simple fiber amplifier to a 2-ps laser source and optical parametric oscillator based SRS setup, one can achieve simultaneous two-color or frequency modulation SRS microscopy. The fiber amplifier can generate wavelength tunable laser ±10 nm around the Stokes laser wavelength with average power higher than 200 mW. In vivo and ex vivo lipid-protein imaging of mouse brain and skin is demonstrated. To further demonstrate the potential of this technique in high-speed in vivo imaging, white blood cells in blood stream were imaged in a live mouse.

Stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) is an emerging label-free subcellular-resolution chemical imaging technique [1–3]. By coherent excitation of molecular vibration, the distributions of protein, lipids, nucleic acid, cholesterol, etc. can be mapped out in cells and tissues with high resolution [1–7]. SRS is suitable for in vivo high speed chemical imaging with the frame rate up to video rate [8, 9]. In most of the SRS imaging applications, imaging at more than one Raman band is necessary [4, 7, 10–15], among which two-color SRS imaging is mostly used. For example, in SRS-based label-free histology, the distributions of lipid and protein are mapped with Raman signals at CH2 and CH3 respectively [10, 12, 14]. For imaging a specific chemical, on- and off-resonant coherent Raman imaging is typically performed to confirm the Raman origin of the signal and to remove the non-resonant background, which is especially prominent in coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy [4, 11, 13, 16–19].

To take advantage of the spectral information in Raman spectroscopy, several multi-color or hyperspectral SRS imaging techniques have been developed [5, 9, 20–28]. With these techniques, spectral information in the imaging area is mapped out in relatively short time. However, the spectral information comes at the cost of imaging speed, complicated setups or are limited to transmission imaging mode. Multi-color SRS microscopy performed by imaging different colors sequentially requires much longer data acquisition time [7, 10, 12, 14, 23, 28]. In grating based multi-color imaging techniques, the lasers can only be collected after they transmit through the sample [22, 26]. However, epi-detected scheme is necessary for thick and non-transparent samples or in vivo imaging tasks.

Since two-color imaging is very commonly used in SRS microscopy, and in vivo imaging are often speed demanding, we developed a simultaneous two-color SRS (STC-SRS) setup.

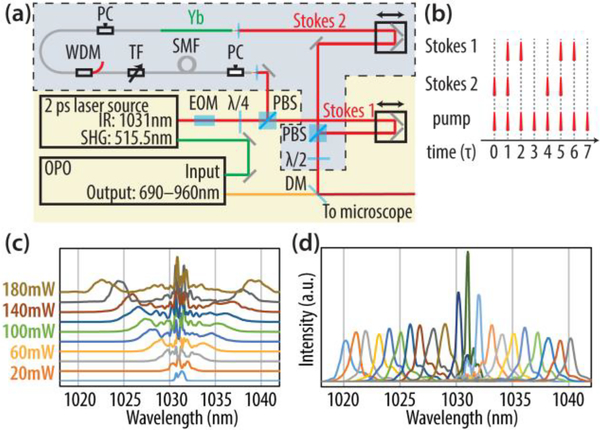

The STC-SRS setup is based on a conventional SRS setup. In a conventional setup (Fig. 1 (a) excluding the part in the box enclosed by dashed line), an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) (Levante Emerald, A.P.E. Berlin) was pumped by the SHG output of a 2-ps laser source (3.2 W at 515.5 nm, Emerald Engine Basic Duo, A.P.E. Berlin). The OPO output a laser tunable from 690 nm to 960 nm with power around 800 mW. The OPO output was then overlapped temporally and spatially with the IR output of the same 2-ps laser source (~ 1 W at 1031.2 nm). The combined beam was sent to a laser scanning microscope for SRS imaging. In SRS, the IR output of the laser source is called Stokes laser and the OPO output is called pump beam, because they serve as Stokes and pump beams in a stimulated Raman process respectively. The Stokes laser was synchronously modulated at 20 MHz by an electric-optical modulator (EOM). Full modulation depth can be achieved at 20 MHz, which is a quarter of laser repetition rate, because quarter-wave voltage of the EOM can be achieved four times in a sine cycle and the four adjacent pulses experienced −λ/4, −λ/4, +λ/4, +λ/4 phase shift from the EOM before offset by the quarter-wave plate to 0, 0, +λ/2, +λ/2. When the combined beam is focused on the sample, SRS process in the focal region cause a gain of power for the Stokes beam (i.e. stimulated Raman gain, SRG) and a loss of power for the pump beam (i.e. stimulated Raman loss, SRL). In our case, we measured the SRL with an amplified photodiode and a lock-in amplifier [29].

Fig. 1.

(a). Laser setup for the two-color simultaneous SRS. PBS: polarizing beam splitter. EOM: electric-optical modulator. DM: dichroic mirror. λ/2: half-wave plate. λ/4 quarter-wave plate. PC: polarization controlling unit. SMF: 2-meter single mode fiber. TF: tunable filter. WDM: wavelength-division multiplexer. Yb: 20 cm ytterbium gain fiber. (b). Pulse delaying scheme of two Stokes lasers and the pump laser. τ is 1/(laser repetition rate) and τ ~ 12.5 ns. (c). Spectral broadening of the 2-ps pulses at 1030 nm in the 2-meter SMF with different average power of laser with 20 MHz modulation. (d). Wavelength tuning of the Yb amplifier.

In STC-SRS, there were two Stokes lasers (Stokes 1 and Stokes 2) and one pump laser. The Stokes 2 laser was generated by sending the normally deserted opposite phase-modulated pulses from the PBS after the EOM to a fiber based frequency generator and amplifier. The IR pulses (2 ps, 1031.2 nm) first went through two meters of single mode fiber (1060 XP, Thorlabs). The pulses underwent self-phase modulation process in the fiber [30, 31]. As a result, the spectrum was broadened and the degree of broadening depended on pulse energy in the fiber (Fig. 1 (c)). Then the laser was spectrally filtered by a customized tunable filter (Agiltron) with 1 nm bandwidth. The filtered laser was then amplified in 20 cm ytterbium gain fiber (F-DF1100, Newport) pumped at 976 nm by a 450 mW single-mode laser diode. A wavelength division multiplexer (WDM) was used to combine the filtered seed laser and the 976 nm pump laser. The output could be tuned between 1020 nm and 1040 nm by adjusting input power of the SMF and the center wavelength of the tunable filter (Fig. 1(d)).

The Stokes 2 laser generated from the fiber amplifier was spatially overlapped with the Stokes 1 laser from the 2-ps laser source using a polarizing beam splitter (PBS). Then, the two Stokes lasers were combined with pump laser with a dichroic mirror. The polarization of two Stokes was adjusted by a half-wave plate, so that each Stokes laser’s polarization partially aligned with the polarization of pump laser. The delays of two Stokes lasers were adjusted so that they temporally overlap with pump laser pulses. Since the input laser of fiber amplifier was modulated, the second Stokes laser was also modulated at 20 MHz and we optimized the length of fiber and optical path so that the modulation phases of two Stokes lasers were exactly 90 degrees different, as shown in Fig. 1 (b). This allowed us to perform phase-sensitive detection with a lock-in amplifier and acquire the Raman signals generated by both Stokes laser simultaneously from orthogonal X and Y outputs of the lock-in amplifier.

The STC-SRS imaging was performed on an upright laser scanning microscope (Olympus FV300/BX-61WI). The laser beam was focused on the sample with an 25x water immersion objective (Olympus XL Plan N 25x/1.05 N.A.). For transmission SRS imaging, the laser transmitted through the sample was collected by a high N.A. (1.4) oil immersion condenser. The transmitted Stokes lasers were blocked by a bandpass filter (ET890/220m, Chroma) and the pump laser was detected by a silicon photodiode (PDB-C609–2, Advanced Photonix, Inc.) with a filtered trans-impedance amplifier [29]. The electronical signal was demodulated by a lock-in amplifier. The X and Y outputs were sent to the data acquisition card of microscope and visualized in the computer. For epi-detected SRS imaging, laser beam went through a PBS and a quarter-wave plate before being focused by the objective. The reflected laser from sample went back through the objective, quarter-wave plate, and was reflected by the PBS. The pump laser then passed through a bandpass filter and was collected by the amplified photodiode.

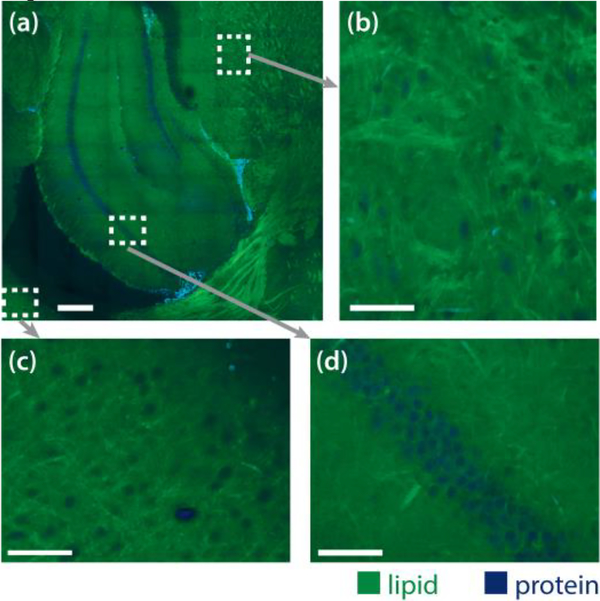

First, we demonstrated the performance of the STC-SRS system in transmission mode by imaging a 1-mmthick slice of the fresh mouse brain at 2850 cm−1 and 2930 cm-1. The fiber amplifier was tuned to 1022.7 nm. The lipid and protein contrast was calculated by the decomposition method in [12]. We took a tiling of 9 by 9 images, shown in Fig. 2 (a) with the pixel dwell time of 4 μs, the green color represents lipid contrast and the blue color represents protein contrast. From the zoom-in images shown in Fig. 2 (b, c, d), we could identify the cell body by a lack of lipid signal. In Fig 2 (a), the places that have both high lipid and protein signals are red blood cells. Their signal not only come from stimulated Raman scattering but also from two-color two-photon absorption of the hemoglobin [32].

Fig. 2.

(a). Lipid-protein simultaneous two-color SRS tiling of fresh 1 mm-thick mouse brain slice in transmission mode. Blue represents the protein contrast and green represents the lipid contrast. Scale bar is 250 μm. (b, c, d). Zoom-in images. Scale bar is 50 μm.

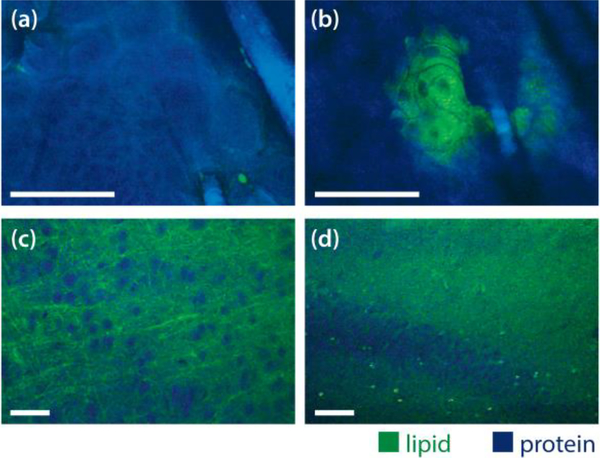

Secondly, we demonstrated epi-detected SRS imaging with mouse ear and brain. In vivo imaging of mouse ear showed stratum corneum and the deeper cellular structures in Fig. 3 (a). Most of these structures are protein rich, except for a few lipid droplets near the hairs or at the edge of stratum corneum. We also imaged sebaceous glands on mouse ear, one of which is shown in Fig. 3 (b). It is rich in lipid and the nuclei have less lipid content. The hair is mainly protein. We can see that the two colors were perfectly aligned. We took a video (Visualization 1) when we scanned across a larger area of the skin.

Fig. 3.

(a, b). In vivo mouse ear skin imaging in epi-detection mode. Scale bar 50 μm. (c, d). Ex vivo mouse brain slice imaging in epi-detection mode. Scale bar 50 μm. Blue color represents the protein contrast and green color represents the lipid contrast.

We also imaged the fresh mouse brain tissue in the epi-detected mode (Fig. 3 c, d). Even though there was significant reduction in signal to noise ratio compared with the images taken in transmission mode (Fig. 2), the neuron cell bodies and myelin fibers were easily identifiable. This capability will allow us to scan across a larger area of brain for in vivo histology and check the cell morphology and cellularity in the brain tissue, which are the key parameters for brain tumor identification [12, 14]. The video for the imaging of the brain tissue is in Visualization 2.

Lipid-protein two-color imaging was extensively used in the recent research of label-free histology of brain tumors with SRS [10, 12, 14, 15]. The STC-SRS setup is at least twice faster than implementations used in the previous publications. It completely removes motion artifact, and will be ideal for in vivo label-free histology.

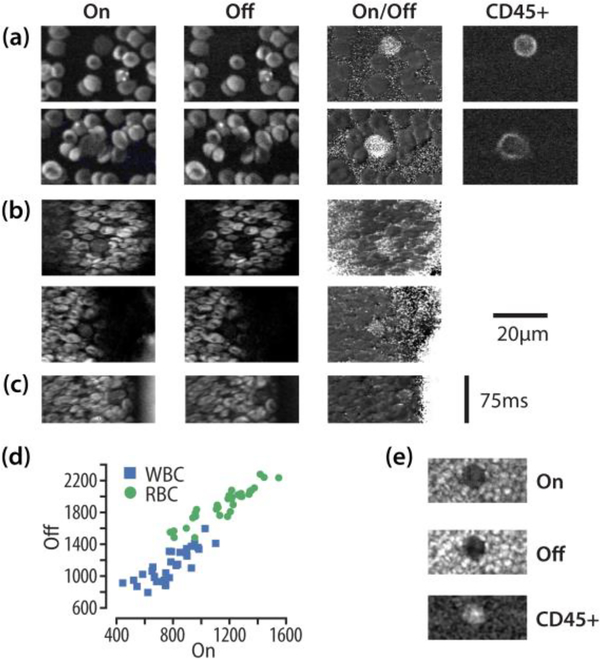

At last, to demonstrate the ability of current setup in high speed imaging, we performed the first in vivo white blood cells (WBCs) imaging with SRS.

We performed ex vivo whole blood imaging as the first step in this experiment. We stained the WBCs from mice by CD45 antibody conjugated to Alexa 488 dye (Biolegend Cat. # 103121). We used the CD45 staining as a verification for WBCs. The typical image of single layer blood cells is shown in Fig. 4 (a). From this image, we can see that the WBCs have less signal than that of RBCs at on-resonant wavenumber (2945 cm−1). At off-resonant wavenumber (3026 cm−1) the WBCs have almost no signal, while the RBC signal remains. This is because two-color two-photon absorption of hemoglobin generated a strong non-resonant background at both Raman bands [32]. In blood vessels other than capillaries, the blood cells are not single layer. So we imaged thick multi-layer blood smears and the average intensity of 32 WBCs and their nearby RBCs was plotted in Fig. 4 (d). The statistical analysis showed that the ratios of SRS signals of RBCs and WBCs were significantly higher at off-resonant than at on-resonant wavenumbers. A typical image of blood cells for thick blood smear was shown in Fig. 4 (e).

Fig. 4.

(a). Ex vivo mouse blood on-resonance (2945 cm−1) and off-resonance (3026 cm−1) imaging. Anti-CD45 antibody was used to label white blood cells. Alexa 488 dye conjugated to CD45 antibody was visualized through two-photon excited fluorescence. (b). In vivo mouse blood flow imaging in time lapse mode, pixel dwell time was 2 μs. (c). In vivo mouse blood flow imaging in the line scan mode. (d). Average signal level 32 WBCs and nearby RBCs at on- and off-resonant Raman bands. The images on the right are examples of WBC in thick mouse blood smears.

For in vivo blood imaging, we imaged the blood vessels under the belly skin of mice. We exposed the blood vessels by flipping the skin out and imaged the blood cells in transmission mode. This method has been previously used for in vivo blood imaging [33]. Animal imaging procedures were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Harvard University. Fig. 4 (b) shows the images of blood cells in vivo. We can see clearly that the WBCs were visible in the on-resonant images and vanished in the off-resonant images. We also divided the signal of on-resonant images by that of the off-resonant images to visualize WBCs in the image. Because the blood was flowing in relatively steady speed in one direction in the blood vessel, we were also able to use line scan mode to image the blood cells, as shown in Fig. 4 (c). The image was obtained by scanning in horizontal direction and the vertical direction is time. Because the blood was not single-layer in the blood vessels, the WBCs also showed some signal at off-resonant wavenumber (3026 cm−1) due to the off-focus RBC signal, which was obvious in the ex vivo thick mouse blood smear imaging show in Fig. 4 (e). Based on the statistics of data in Fig. 4 (d) and the assumption that cells in the blood vesicle were either WBCs or RBCs, we can confirm that the cells shown in Fig. 4 (b, c) were WBCs. This is the first time that multi-color SRS was used to image white blood cells in the blood stream of live animals.

In vivo imaging of blood showed that simultaneous two-color SRS can be very useful for high speed SRS imaging in live animals. Label-free WBCs detection has been achieved recently by third-harmonic microscopy [34] and spectrally encoded reflection imaging [35]. However, these techniques lack the chemical specificity compared with SRS. Our method could also be extended to simultaneous multi-color imaging. It was reported that circulating tumor cells (CTCs) of prostate cancer are rich in lipid [36]. We expect that, by adding one more color, it may be feasible to image the CTCs with simultaneous SRS imaging at lipid (2850 cm−1), protein (2930 cm−1) and an off-resonance Raman frequency.

For imaging in transmission mode, the optical power of the three lasers on the sample was about 150 mW (pump), 140 mW (Stokes 1) and 62 mW (Stokes 2). For epi-detection imaging, the pump power was about 400 mW.

In the current setup, the two Stokes lasers were combined by a PBS with opposite polarizations. Neither of the Stokes are fully aligned with pump in polarization to produce maximum SRS signal. A grating based beam combiner can solve this problem and allows more colors to be added, but it would increase the complexity of the optical setup. We chose single mode fiber for spectrum broadening to demonstrate the simplicity of this method and reduce splicing losses of highly nonlinear fiber. We found that this technique is not feasible for a 6-ps laser system since the nonlinear effect was too weak. The fiber laser source was relatively stable during the imaging period on the scale of hours, which can be seen from Fig. 2 (a). However, we have seen some relatively fast SRS signal fluctuations of about 1% at the time scale of tens of milliseconds.

One of the advantages of this method is that the power generated from the fiber amplifier is relatively high. With single stage amplification pumped by a 450 mW butterfly laser diode at 976 nm, the output power was 230–270 mW within the tuning range of ± 10 nm from the seed laser. In fact, if tunability can be sacrificed, it is possible to generate laser at longer wavelengths (e.g. 1060 nm, 29 nm away from the seed laser) by optimizing the length of the spectrum broadening fiber and the design of the Yb fiber amplifier. That would allow simultaneous imaging of lipid, protein and water, which will be useful for applications such as skin imaging.

In conclusion, we have developed a simultaneous two-color SRS microscopy system by adding a simple fiber amplifier to a conventional OPO based SRS imaging setup pumped by a 2-ps laser source. We demonstrated that the current setup can be used in ex vivo and in vivo lipid protein two-color, epi-detected SRS imaging of brain and skin without any motion artifacts. We also demonstrated its power for high speed in vivo imaging of white blood cells. We believe that such a system will be suitable for ex vivo and in vivo label-free histology and high speed chemical imaging applications.

Acknowledgment.

We thank the help and discussion with Dr. Dan Fu and Feng Tian. This work was performed in part at the Harvard University Center for Nanoscale Systems (CNS), a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Network (NNCI), which is supported by the National Science Foundation.

Funding. Department of Energy (DE-SC0001548, DE-SC0012411); National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (R01EB017254); NSF (1541959)

Footnotes

Disclosures. XSX: Invenio Imaging, Inc. (I)

References:

- 1.Freudiger CW, Min W, Saar BG, Lu S, Holtom GR, He CW, Tsai JC, Kang JX, and Xie XS, Science 322, 1857 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nandakumar P, Kovalev A, and Volkmer A, New J. Phys 11, 033026 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozeki Y, Dake F, Kajiyama S. i., Fukui K, and Itoh K, Opt. Express 17, 3651 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Roeffaers MBJ, Basu S, Daniele JR, Fu D, Freudiger CW, Holtom GR, and Xie XS, ChemPhysChem 13, 1054 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang P, Li J, Wang P, Hu CR, Zhang D, Sturek M, and Cheng JX, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 52, 13042 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu D, Zhou J, Zhu WS, Manley PW, Wang YK, Hood T, Wylie A, and Xie XS, Nat. Chem 6, 614 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu F-K, Basu S, Igras V, Hoang MP, Ji M, Fu D, Holtom GR, Neel VA, Freudiger CW, Fisher DE, and Xie XS, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 11624 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saar BG, Freudiger CW, Reichman J, Stanley CM, Holtom GR, and Xie XS, Science 330, 1368 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozeki Y, Umemura W, Otsuka Y, Satoh S, Hashimoto H, Sumimura K, Nishizawa N, Fukui K, and Itoh K, Nat. Photon 6, 845 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freudiger CW, Pfannl R, Orringer DA, Saar BG, Ji M, Zeng Q, Ottoboni L, Ying W, Waeber C, and Sims JR, Lab. Invest 92, 1492 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei L, Yu Y, Shen Y, Wang MC, and Min W, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 11226 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji MB, Orringer DA, Freudiger CW, Ramkissoon S, Liu XH, Lau D, Golby AJ, Norton I, Hayashi M, Agar NYR, Young GS, Spino C, Santagata S, Camelo-Piragua S, Ligon KL, Sagher O, and Xie XS, Sci. Transl. Med 5, 201ra119 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong S, Chen T, Zhu Y, Li A, Huang Y, and Chen X, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 126, 5937 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji M, Lewis S, Camelo-Piragua S, Ramkissoon SH, Snuderl M, Venneti S, Fisher-Hubbard A, Garrard M, Fu D, and Wang AC, Sci. Transl. Med 7, 309ra163 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu F-K, Calligaris D, Olubiyi OI, Norton I, Yang W, Santagata S, Xie XS, Golby AJ, and Agar NY, Cancer Res. 76, 3451 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duncan M, Opt. Commun 50, 307 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulsen HN, Hilligse KM, Thøgersen J, Keiding SR, and Larsen JJ, Opt. Lett 28, 1123 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichimura T, Hayazawa N, Hashimoto M, Inouye Y, and Kawata S, Phys. Rev. Lett 92, 220801 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slipchenko MN, Chen H, Ely DR, Jung Y, Carvajal MT, and Cheng J-X, Analyst 135, 2613 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freudiger CW, Min W, Holtom GR, Xu B, Dantus M, and Xie XS, Nat. Photon 5, 103 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu D, Lu F-K, Zhang X, Freudiger C, Pernik DR, Holtom G, and Xie XS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 134, 3623 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu F-K, Ji M, Fu D, Ni X, Freudiger CW, Holtom G, and Xie XS, Mol. Phys 110, 1927 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu D, Holtom G, Freudiger C, Zhang X, and Xie XS, J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 4634 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong L, Ji M, Holtom GR, Fu D, Freudiger CW, and Xie XS, Opt. Lett 38, 145 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang D, Slipchenko MN, Leaird DE, Weiner AM, and Cheng J-X, Opt. Express 21, 13864 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao C-S, Slipchenko MN, Wang P, Li J, Lee S-Y, Oglesbee RA, and Cheng J-X, Light. Sci. Appl 4, e265 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao C-S, Wang P, Wang P, Li J, Lee HJ, Eakins G, and Cheng J-X, Sci. Adv 1, e150073 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu D, Yu Y, Folick A, Currie E, Farese RV Jr, Tsai T-H, Xie XS, and Wang MC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 8820 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian F, Yang W, Mordes DA, Wang J-Y, Salameh JS, Mok J, Chew J, Sharma A, Leno-Duran E, and Suzuki-Uematsu S, Nat. Commun 7, 13283 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stolen R and Lin C, Phys. Rev. A 17, 1448 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimizu F, Phys. Rev. Lett 19, 1097 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu D, Ye T, Matthews TE, Chen BJ, Yurtserver G, and Warren WS, Opt. Lett 32, 2641 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mempel TR, Scimone ML, Mora JR, and von Andrian UH, Curr. Opin. Immunol 16, 406 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C-K and Liu T-M, Biomed. Opt. Express 3, 2860 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golan L, Yeheskely-Hayon D, Minai L, Dann EJ, and Yelin D, Biomed. Opt. Express 3, 1455 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitra R, Chao O, Urasaki Y, Goodman OB, and Le TT, BMC Cancer 12, 540 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]