Abstract

Background:

The costs of cancer care in the US continue to increase and may have serious consequences for patients. We hypothesize that even cancer patients treated with curative-intent surgery alone experience substantial financial burden.

Methods:

A questionnaire was administered to adult cancer patients who were treated with curative-intent surgery. Survey items included a validated instrument for measuring financial toxicity, the COST score. Demographic variables and survey responses were examined using Chi-square and Fisher exact tests. A multivariate general linear model was performed to examine the relationship between age and COST score.

Results:

COST scores varied widely. 30% of respondents had a COST score of ≤24 (high burden). Younger participants reported more financial burden (p = 0.008). Respondents reported that financial factors influenced their decisions regarding surgery (14%) and caused them to skip recommended care (4.7%). Cancer care influenced overall financial health (38%) and contributed to medical debt (26%).

Conclusion:

Curative-intent cancer care places a substantial portion of patients at risk for financial toxicity even when they don’t require chemotherapy. Interventions should not be limited to patients receiving chemotherapy.

Keywords: Financial toxicity, Cost of care, Surgical oncology

Introduction

The costs of cancer care in the United States continue to increase rapidly. The Agency for Health Care Research and Quality estimates that direct medical costs for cancer care in the US in 2015 were roughly $80.2 billion dollars.1 Increasing costs can be attributed to many factors including an aging population, greater access to care, development of new, innovative therapies, and overuse of existing treatments.2 As costs have increased, insurance plans are also changing to include higher premiums, deductibles and co-pays. As a result, patients’ out-of-pocket (OOP) costs for cancer care have increased substantially.3,4 This financial burden can have direct health consequences for patients. In recent years, stakeholders have recognized the adverse impact of financial burden as a treatment-related toxicity, or “financial toxicity,” akin to the physical side effects associated with medications or complications from surgery.5

While the high prevalence of financial toxicity among cancer patients and survivors is increasingly recognized, most studies have focused on patients receiving chemotherapy, generally in the metastatic setting. Yet, there is reason to believe that even patients treated with curative-intent surgery alone are at risk for substantial financial burden and toxicity from cancer care. We hypothesize that the prevalence of financial burden is high among cancer patients treated with curative intent surgery alone.

Material and methods

From January 2017–July 2017, a questionnaire was administered to adult surgical oncology patients treated at the University of North Carolina (UNC), an academic tertiary care comprehensive cancer center. Patients eligible for participation were 6–18 months post curative-intent cancer-directed surgery. Exclusion criteria included receipt of any chemotherapy, inability to read/write in English, and incarceration or inability to give informed consent. Study staff identified eligible patients through weekly review of surgical oncology clinic schedules. Potential participants were approached by study staff members and asked to complete the survey while waiting for follow-up appointments at the University of North Carolina Surgical Oncology Clinics (North Carolina Cancer Hospital and UNC Health Care Hillsborough Campus). Those who consented to participate were administered a written questionnaire that could be anonymously returned in the clinic or at a later date with prepaid return envelopes.

The survey instrument was a one-time, paper-based questionnaire assessing patient-reported financial burden and impact of financial burden on health and treatment. Survey items included a previously published and validated instrument for measuring financial toxicity, the COST measure.3 The COST measure uses 11 questions to capture financial distress in cancer patients using a 5-point Likert scale. Items include questions like “I feel in control of my financial situation,” and “My out-of-pocket medical expenses are more than I thought they would be.” Participants were also asked about their cancer, the treatment they received, the influence of finances on surgical decision making, and pre-operative awareness of and use of information resources, including financial counselors, insurance companies, and providers. Although initial chart review eligibility screen included receipt of chemotherapy as an exclusion criteria, there were some participants who indicated in their responses that they had received chemotherapy. These participants were excluded at the time of analysis. Demographic data, including gender, age at diagnosis, race and ethnicity, marital status, and work status (full/part time, unemployed, retired, and student) was also collected.

Study data were managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDcap) electronic data capture tools hosted at UNC at Chapel Hill. Analysis was completed using SAS Enterprise Guide (v 7.11, Cary, NC).

The COST measure items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, which allows participants to report their perceived financial burden. COST scores were calculated on a 0–44 scale for each participant that completed all COST survey questions, with reverse scoring on items 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 10.3 Lower scores indicated worse financial toxicity. Values were dichotomized at 24, the 30th percentile of scores, for additional analysis. Demographic variables and survey responses were reported as frequencies and differences, measured using Chi-square and Fisher exact tests. A general linear model, controlling for cancer type, gender, race, age at diagnosis, and insurance type, examined differences in COST score. Insurance type was chosen for the model rather than work status, as they were strongly correlated and insurance type is more closely related to out-of-pocket costs.

The study was exempted from full review by the UNC Institutional Review Board (IRB # 17–0463).

Results

One hundred and twenty three individuals completed the survey. Thirty-two were later excluded as they reported receiving at least some chemotherapy, by pill or intravenously. Five additional participants were excluded for non-response to at least 6 items on the COST scale. The most common tumor type was melanoma (44%) with substantial representation of breast/DCIS (17%), colorectal (10%) and GIST or neuroendocrine tumors (10%). Table 1. The majority were married (77%) and white (84%). While everyone reported having some form of insurance, three participants (3.4%) indicated they received charity care and/or were uninsured within the last year. Over half (53%) were retired.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| Demographics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 86) n (%) |

Low Burden COST > 24 (N = 60) n (%) |

High Burden COST ≤24 (N = 26) n (%) |

P- value |

||

| Cancer Type | Colorectal | 9(10%) | 6 (10.0%) | 3 (11.5%) | 0.67 |

| DCIS/Breast | 15 (17%) | 12 (20.0%) | 3 (11.5%) | ||

| Neuroendocrine/GIST | 9 (10%) | 5 (8.3%) | 4 (15.4%) | ||

| Liver | 5 (6%) | 4 (6.7%) | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Melanoma/Skin | 38(44%) | 27 (45.0%) | 11 (42.3%) | ||

| Other | 5(6%) | 2 (3.3%) | 3 (11.5%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 39(45%) | 29 (48.3%) | 10 (38.5%) | 0.40 |

| Female | 47 (55%) | 31 (51.7%) | 16(61.5%) | ||

| Race | Non-Hispanic white | 72 (84%) | 54 (90.0%) | 18 (69.2%) | 0.02 |

| Non-white, Other, unidentified, or | 14(16%) | 6 (10.0%) | 8 (30.8%) | ||

| unknown | |||||

| Marital Status | Married or Living together | 66 (77%) | 50 (83.3%) | 16(61.5%) | 0.08 |

| Divorced/Separated | 10(12%) | 6 (10.0%) | 4 (15.4%) | ||

| Widowed | 4 (5%) | 2 (3.3%) | 2 (7.7%) | ||

| Single, never married | 6 (7%) | 2 (3.3%) | 4 (15.4%) | ||

| Employment Status | Working full/part-time | 31 (36%) | 19(31.7%) | 12 (46.2%) | 0.01 |

| Retired or disabled | 46 (53%) | 38 (63.3%) | 8 (30.8%) | ||

| Unemployed or disabled | 9(10%) | 3 (5.0%) | 6(23.1%) | ||

| Insurance Type | Medicare only | 12(14%) | 8 (13.3%) | 4 (15.4%) | 0.038 |

| Mix of private and public | 21 (24%) | 19(31.7%) | 2 (7.7%) | ||

| Private only | 38 (44%) | 26 (43.3%) | 12 (46.2%) | ||

| Medicaid | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0(0%) | ||

| Other | 15 (17%) | 7(11.7%) | 8 (30.8%) | ||

| Number of surgeries | 1 | 58 (67%) | 44 (73.3%) | 14 (53.8%) | 0.15 |

| 2 | 19(22%) | 10(16.7%) | 9 (34.6%) | ||

| ≥3 | 8 (9%) | 10(16.7%) | 9 (34.6%) | ||

| Length of hospital stay | I went home the same day | 46 (53%) | 13 (21.7%) | 8 (30.8%) | 0.09 |

| 1–2 days | 9(10%) | 5 (8.3%) | 4 (15.4%) | ||

| 3–10 days | 21 (24%) | 13 (21.7%) | 8 (30.8%) | ||

| Stayed more than 10 days | 7 (8%) | 3 (5.0%) | 4 (15.4%) | ||

| Ongoing debt | No | 64 (74%) | 55 (91.7%) | 9 (34.6%) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 22 (26%) | 5 (8.3%) | 17 (65.4%) | ||

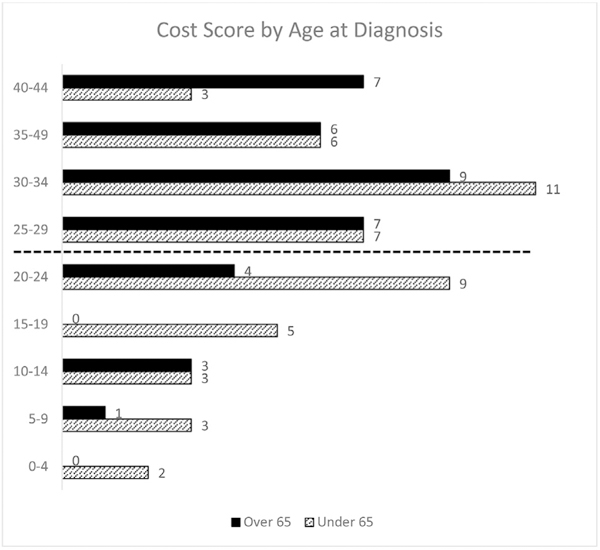

COST score varied widely. Fig. 1. 30% of respondents had a COST score of ≤24. In univariate analysis, the dichotomized COST score was associated with race (p = 0.02), insurance status (p = 0.04), and employment (p = 0.01) but not with length of hospital stay (p = 0.09) or number of surgeries (p = 0.15).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of COST scores.

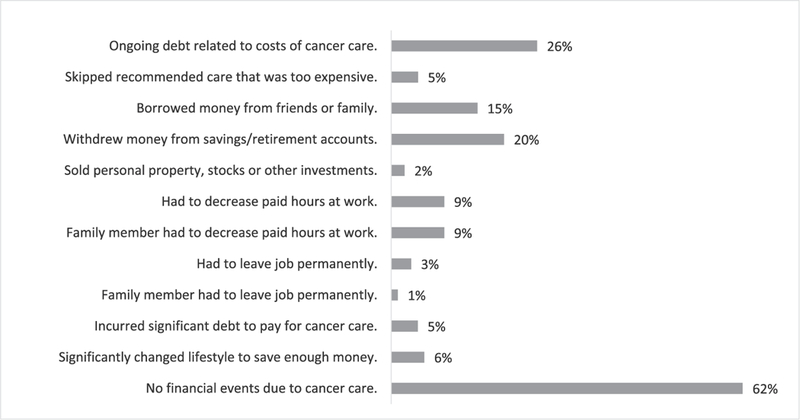

Fourteen percent of respondents reported that financial factors influenced their decisions regarding surgery, including if (8.1%), when (10.5%), and where (10.5%) to have surgery, as well as what type (7.1%) of surgery to have. On average, these individuals had worse COST scores than other respondents (19.3 vs. 29.2, p = 0.001). They were also more likely to report race as non-white (35.7% vs. 9.7%, p = 0.01) and to report ongoing debt related to cancer care (58.3% vs. 20.3%, p = 0.005). For the group as a whole, 38% reported some impact of cancer care on overall financial health with 26% reporting ongoing medical debt. Fig. 2. However, only 4 participants (4.7%) reported skipping recommended medical care, including procedures, appointments, medications, or tests, due to cost.

Fig. 2.

Impact of finances on decisions about surgical cancer care.

Overall, participants reported they were not well informed about the costs of care or about the resources available to obtain this information. Only 31% reported they had access prior to surgery to the information needed to determine how much surgery would cost them; 37% reported they were not aware of resources available to help them determine OOP costs; and 38% felt inadequately informed about the costs of surgery and recovery. Despite the presence of on-site financial counselors, very few participants reported that they talked with a financial counselor (12%), their insurance company (17%), or their surgeon (6%) about costs of care prior to surgery. (Table 2a). However, those that did generally found it helpful (70%). Twenty-nine percent (18/62) of participants who did not talk to a financial counselor, insurance company or surgeon about cost wished they had, and 37.5% (9/15) of participants who did talk to someone about costs wished they had spoken to an additional party about cost. Encouragingly, participants who reported that costs affected their decisions with regard to surgical care were more likely than others to have talked with someone about costs of care prior to treatment. (Table 2b).

Table 2.

Incidence and perceived value of discussion of cost with financial counselor, payer, and or provider. A. All patients. B. Limited to patients who reported costs impacted their decisions regarding surgical care.

| A. | |||

| Financial counselor (n = 85) | Insurance Company (n = 83) | Surgeon (n =83) | |

| I talked with a ___. | 10 (12%) | 14 (17%) | 5 (6%) |

| Helpful | 7 (70%) | 8 (57%) | 4 (80%) |

| Not Helpful | 3 (30%) | 6 (43%) | 1 (20%) |

| I did NOT talk with a ___. | 75 (88%) | 69 (83%) | 78 (94%) |

| I wish I had. | 18 (24%) | 14 (20%) | 11 (14%) |

| I am happy with that. | 57 (76%) | 55 (80%) | 67 (86%) |

| B. | |||

| Financial counselor (n = 11) | Insurance Company (n = 11) | Surgeon (n =12) | |

| I talked with a ___. | 5 (45%) | 2 (18%) | 3 (25%) |

| Helpful | 4 (80%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (100%) |

| Not Helpful | 1 (20%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| I did NOT talk with a ___. | 6 (55%) | 9 (82%) | 9 (75%) |

| I wish I had. | 4 (67%) | 4 (44%) | 4 (44%) |

| I am happy with that. | 2 (33%) | 5 (456%) | 5 (56%) |

In total, 20.6% (14/68) of respondents indicated they wished they had known more about the costs of care or payment options prior to surgery. When asked specifically whether they thought it was appropriate for physicians to discuss finances/costs of care with patients, the majority (59%) responded “yes.” However, among the 30% (20/66) who responded “no,” there were some strong statements indicating that it would be inappropriate or offensive for a physician to discuss this topic (i.e. “No - may stifle the patient relationship with the physician,” “Not appropriate + shows greed - use counselor instead,” etc.)

In a multivariate regression, controlling for cancer type, gender, race, and insurance type, COST score was significantly associated with age (p = 0.008). Fig. 1. For each year later in life a patient was diagnosed with cancer, COST score improved by 0.3 points, suggesting older cancer patients feel less financial stress due to cancer care than younger patients. Insurance type was also associated with COST score (p = 0.041); patients on Medicare (p = 0.033) and “Other” (p = 0.031) insurance types reported significantly greater financial toxicity compared with private payers. Race, gender, and cancer type were not associated with COST score.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that experiencing financial toxicity is common, even amongst patients who do not require chemotherapy and are treated for cure. Consistent with other studies, patients who are younger and working are most at risk.4,6 ‒8

This study shows that for a subset of patients, costs of care influence decisions regarding cancer surgery. This may result in behaviors including hurrying up or delaying surgery based on the timing of annual deductible payments or choosing to have surgery at a lower volume center that is closer to home rather than travel to a larger cancer center. A subset of patients also reported that costs influenced decisions regarding type of surgery. For example, cost could influence decisions such as whether or not to have a sentinel node procedure for melanoma, whether to have mastectomy versus breast conserving therapy, and whether or not to have reconstruction. Interestingly, length of stay was not associated with COST score. This may reflect the relatively short overall length of stay for this study population, but it may also be the case that the bulk of financial burden comes from meeting the initial deductible, which would be a fixed amount and not impacted by a longer length of stay.

Although 14% of participants reported that costs of care influenced their decisions about surgery, very few participants discussed costs of care with their surgeon, a finding consistent with other studies.9 Importantly, those that did discuss costs of care with their provider, generally found that conversation helpful, which raises the question of why patients and providers don’t discuss costs of care more often. One reason is that providers, in general, report they lack the knowledge to adequately counsel patients about costs of care.10,11 In addition, providers may fear offending or alienating patients, which is not unfounded given the strong responses from some participants in this study indicating they believed discussion of costs between provider and patient were inappropriate. Even financial counselors and insurance companies may struggle to appropriately estimate costs of care. The general lack of concrete data on projected costs of care is a major problem in U.S. healthcare and a substantial barrier to appropriate informed decision-making.12

Prior studies have suggested that patients experiencing financial toxicity are more likely to skip recommended care as a cost-saving maneuver.5,7,13 ‒ 15 However, that behavior was uncommon for participants in this study with only 5% of the population reporting that they skipped recommended care. Some of the free text comments suggested that patients generally valued cancer care above all else and thus were not willing to skip care despite the financial burden (i.e. “Cost is always a factor, especially when you are retired and living on a fixed income, however, my health is the most important factor and so I will always consider that my priority,” etc.). These findings differed from those in prior studies in which skipping recommended care has been reported as a relatively common cost saving response.5,7,13–15 The reason for this difference is likely multifactorial. First, we evaluated a population of patients with relatively early cancers treated with curative intent, so the perceived return on investment was high (i.e. “Cancer diagnosis is hard, and hard to separate treatment from costs. You want to be cured! ” “... I feel you have to do what is necessary to continue life.” etc.) Second, participants were enrolled relatively soon (6e18 months) after completion of therapy. Conceivably, a survey of patients further out from completion of active therapy would reveal higher rates of omission of recommended surveillance care.

There are many limitations to this study. The survey was conducted amongst a sample of patients at a single tertiary care cancer center, so may not be a representative sample of all surgical oncology patients. For example, this center is a major referral center for melanoma, resulting in melanoma patients representing a particularly large portion of our study population. Since most melanoma surgery is done in the outpatient setting, our results may underestimate the burden and impact of cost for patients whose cancer surgery requires an inpatient hospitalization. Additionally, some groups of patients at high risk for financial toxicity were not well-captured, as patients who were illiterate or did not read English were excluded. Also, questionnaires were distributed during follow up visits, and patients experiencing substantial financial distress may not have returned for follow up due to the costs of care. Lastly, we intended to capture patients who did not have chemotherapy recommended as part of their first course of treatment. However, we do not know for certain whether participants did not complete chemotherapy because it was not recommended or if it was recommended but they did not receive it, potentially due to financial concerns.

Conclusion

This study suggests that even patients undergoing straightforward curative-intent cancer care are at risk for financial toxicity, and costs of care do influence surgical decision making for some cancer patients. Moreover, in general, patients are poorly informed about the potential costs of care. Strategies are needed to improve financial literacy and communication among cancer patients and providers. Interventions aimed at mitigating the financial toxicity of cancer care should not be limited to patients undergoing chemotherapy, but also need to be developed and tailored to address the issues faced by surgical oncology patients.

Footnotes

Previous meeting presentation

American Society of Clinical Oncologists March 2018, Chicago, IL.

Conflicts of interest

Ms. Natalie Allcott has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ms. Lisette Dunham has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Mr. David Levy has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dr. Jacquelyn Carr has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dr. Karyn Stizenberg has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimers

None.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.01.033.

References

- 1.MEPS summary tables. https://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepstrends/hc_cond/. Accessed May 2, 2018.

- 2.Conti RM, Fein AJ, Bhatta SS. National trends in spending on and use of oral oncologics, first quarter 2006 through third quarter 2011. Health Aff. 2014;33(10):1721–1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: the COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120(20): 3245–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out-of-pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(20):2821–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncol. 2013;18(4):381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff. 2013;32(6):1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119(20):3710–3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(12):1269–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofstatter EW. Understanding patient perspectives on communication about the cost of cancer care: a review of the literature. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6(4): 188–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altomare I, Irwin B, Zafar SY, et al. Physician experience and attitudes toward addressing the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(3):247–288. e281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly RJ, Forde PM, Elnahal SM, Forastiere AA, Rosner GL, Smith TJ. Patients and physicians can discuss costs of cancer treatment in the clinic. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(4):308–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shih YT, Nasso SF, Zafar SY. Price transparency for whom? In search of out-of pocket cost estimates to facilitate cost communication in cancer care. Phar-macoeconomics. 2018;36(3):259–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nipp RD, Zullig LL, Samsa G, et al. Identifying cancer patients who alter care or lifestyle due to treatment-related financial distress. Psycho Oncol. 2016;25(6): 719–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zullig LL, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. Financial distress, use of cost-coping strategies, and adherence to prescription medication among patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(6S):60s–63s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]