Abstract

Background/Aims

This nationwide, multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of 10-day concomitant therapy (CT) and 10-day sequential therapy (ST) with 7-day clarithromycin-containing triple therapy (TT) as first-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection in the Korean population.

Methods

Patients with H. pylori infection were assigned randomly to 7d-TT (lansoprazole 30 mg, amoxicillin 1 g, and clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily for 7 days), 10d-ST (lansoprazole 30 mg and amoxicillin 1 g twice daily for the first 5 days, followed by lansoprazole 30 mg, clarithromycin 500 mg, and metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for the remaining 5 days), or 10d-CT (lansoprazole 30 mg, amoxicillin 1 g, clarithromycin 500 mg, and metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 10 days). The primary endpoint was eradication rate by intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses.

Results

A total of 1,141 patients were included. The 10d-CT protocol achieved a markedly higher eradication rate than the 7d-TT protocol in both the ITT (81.2% vs 63.9%) and PP analyses (90.6% vs 71.4%). The eradication rate of the 10d-ST protocol was superior to that of the 7d-TT protocol (76.3% vs 63.9%, ITT analysis; 85.0% vs 71.4%, PP analysis). No significant differences in adherence or serious side effects were found among the three treatment arms.

Conclusions

The 10d-CT and 10d-ST regimens were superior to the 7d-TT regimen as standard first-line treatment in Korea.

Keywords: Concomitant therapy, Disease eradication, Helicobacter pylori, Triple therapy, Sequential therapy

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with development of gastroduodenal diseases such as duodenal and gastric ulcers, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma.1,2 To reduce the risk of these diseases, there has been continued interest in the elimination of H. pylori.3 The clarithromycin-containing triple therapy (TT), including amoxicillin and clarithromycin combined with a conventional proton-pump inhibitor (PPI), has long been recommended as the first-line treatment for H. pylori eradication and is the most commonly used treatment. It is also suggested by many international and Korean guidelines.4–6 However, the major problem of TT is its clinical efficacy, which has significantly decreased globally to the point of unacceptable levels in many countries.7–9 This is mostly caused by increased antimicrobial resistance, including clarithromycin resistance.10 Similarly, the eradication rate in Korea has been steadily decreasing over the past 20 years and has recently been reported to be 70% to 75%.11–14 However, the Kyoto Global Consensus Report suggests that only regimens with an eradication rate of 90% or more in the area should be used as the sole empirical treatment, making it imperative to find a regimen that provides a more favorable eradication rate.15 Recently, although susceptibility-based merits were suggested, the cost-effectiveness of this strategy has not been rigorously evaluated.16 Because no evidence supports the superiority of tailored therapy over empirical therapy at the nation level, optimal empirical regimen still needs to be determined.

Several alternative therapies have been proposed, including bismuth-containing quadruple therapy and non-bismuth-containing quadruple therapy.17 A non-bismuth-containing quadruple therapy known as concomitant therapy (CT) may be an alternative and has been found to be effective in an environment of high clarithromycin resistance.18 Furthermore, some randomized trials have suggested that CT in the Korean population is likely to be more effective than the sequential therapy (ST).19,20 ST is among the proposed therapies and is relatively less dependent on clarithromycin sensitivity and therefore expected to be a suitable first-line regimen. Furthermore, a meta-analysis reported that ST was comparably more effective than TT, although a variation in efficacy was found because of regional differences in antibiotic resistance.21–23 Despite previous results, there were issues of inadequate quality of research design, insufficient sample size, and most studies were single institutional or local studies in Korea. Thus, it is highly important to conduct a well-designed nationwide population-based trial to determine the most appropriate first-line treatment regimen for Korean subjects. Such a trial enables providing a basis for changing the primary treatment in light of the domestic reality, as well as providing specific alternatives in Korea. In fact, the study was endorsed by the Korean government as part of an effort to prevent gastric cancer by eradicating H. pylori in Korea.

Therefore, the primary endpoint was to demonstrate the difference in eradication rates between CT for 10 days versus TT, ST for 10 days versus TT, respectively. Our secondary aim was to evaluate drug compliance and adverse events of the three treatment groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study design

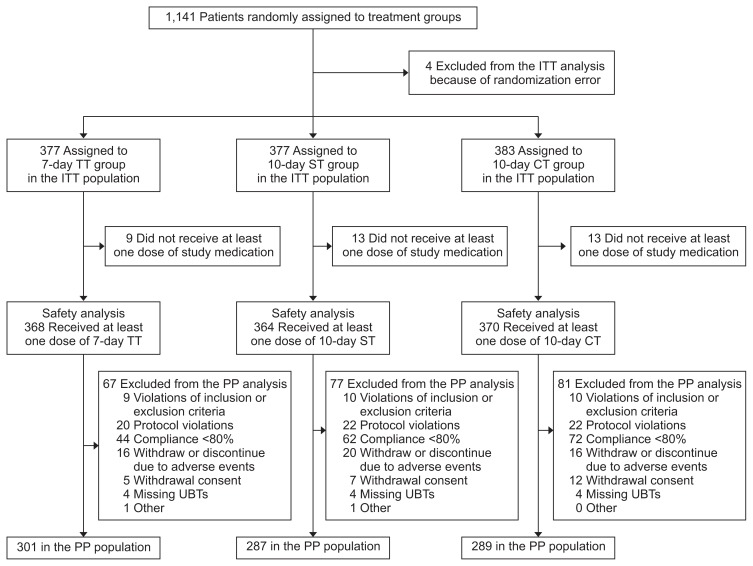

This was a multicenter, prospective, randomized, three-armed, superiority, parallel-group, open label trial which was performed at fifteen institutions nationwide in Korea. The study design has been published previously,24 and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Medical Center, Korea (IRB number: SMC 2016-02-131-002), and all participating centers also approved committee approval. The study was conducted in accordance with the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Food and Drug Administration regulations regarding Good Clinical Practice. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This investigator-initiated trial is registered at https://cris.nih.go.kr/cris (Identifier number: KCT0001980). Fig. 1 demonstrates a flow diagram of this trial.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study. A total of 1,141 patients participated in the study, of which 1,137 were included in the analyses.

ITT, intention-to-treat; TT, triple therapy; ST, sequential therapy; CT, concomitant therapy; PP, per-protocol; UBT, urea breath test.

2. Patients

This trial included H. pylori-infected patients aged ≥19 years who agreed to trial participation, provided written informed consent, and fulfilled the eligibility criteria. In addition, those who met the following criteria were excluded: patients with a previous history of H. pylori infection management; patients with a gastric surgical history; patients with a history of antibiotic therapy within the prior 1 month; patients with a history of PPI use within the prior 2 weeks; patients with a history of taking various drugs; patients with serious concomitant illnesses; pregnant participants.24 Antibiotics or other medications affecting the treatment results were prohibited during the study period.

3. Randomization and allocation concealment

A centralized web-based randomization system, which uses permuted block randomization with a concealed and varying block size, was used for randomization. To ensure concealed allocation, an independent staff dispensed consecutively numbered, identically designed treatment packs that contained sealed bottles of study drugs. Participants were not blinded to group allocation.

4. Procedures

In the treatment group, the experimental arm 1 group received the 10d-ST (lansoprazole 30 mg and amoxicillin 1 g twice daily for the first 5 days followed by lansoprazole 30 mg, clarithromycin 500 mg, and metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for the remaining 5 days), and the experimental arm 2 group received CT (10d-CT; lansoprazole 30 mg, amoxicillin 1 g, clarithromycin 500 mg, and metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 10 days). In addition, the control group received the triple regimen (7d-TT; lansoprazole 30 mg, amoxicillin 1 g, and clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily for 7 days). Before enrollment, rapid urease test, urea breath test (UBT), and/or histology was performed for the evaluation of H. pylori infection status. Adverse event and compliance were evaluated at the first visit after allocation. At the second visit, the efficacy of H. pylori eradication therapy was determined. UBT was conducted to assess H. pylori status at the 4th to 6th week after the end of H. pylori eradication therapy. A staff member blinded to the eradication arm of each patient performed the UBT.

5. Outcomes

The primary endpoint of the study is the H. pylori eradication rate. The secondary endpoints are the adverse events and treatment compliance. Adverse events were evaluated using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0.25 Adherence to treatment was assessed by providing all patients with a prestructured printed table with all dosages illustrated. Poor compliance was defined as the use of less than 80% of the total medication prescribed.11,26

6. Statistical considerations

The eradication rate of 7d-TT is approximately 75% in Korea,27 and the eradication rate of sequential or CT has been reported to be more than 80%.28,29 To obtain the optimal eradiation rate, an eradication efficacy of more than 85% is needed. Therefore, we hypothesized that the eradication rate would be superior in the 10d-ST or 10d-CT groups, with a 10% difference compared to the rate for 7d-TT (85% vs 75%). To demonstrate this 10% difference in the eradication rate using a statistical power of 80% and type one error rate of 0.025 allowing maximum 20% of the participant drop-out or noncompliance, the protocol requires 1,137 subjects.

All efficacy analyses were evaluated for the intent-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) populations. The primary endpoint was assessed in the ITT population. All randomized subjects were included in the ITT analysis. Patients who did not return for a follow-up UBT were considered treatment failures. In the PP analysis, patients with unknown H. pylori status following therapy and those with major protocol violations were excluded. Subjects who received at least one dose of eradication drugs were included in the safety analysis. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p-value 0.025 was used as cutoff for the statistical significance of the primary outcome analysis, while p-value 0.05 was adopted for all other statistical tests.

RESULTS

1. Clinical characteristics of the study groups

A total of 1,141 patients from 15 hospitals from October 2016 to October 2018 were screened for eligibility. Of these, 1,137 patients were included and randomly assigned to receive a 7d-TT group (n=377), 10d-CT group (n=383), or 10d-ST group (n=377) (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of patients in each study group are summarized in Table 1. There was no significant difference in age, sex, residence, smoking, alcohol consumption, past medical history, and family history of gastric cancer between the three groups. There was no significant difference in the indication of H. pylori eradication between treatment groups. Gastric or duodenal ulcers and post-endoscopic resection for gastric cancer and MALT lymphoma were, respectively, included in 28.0%, 8.4%, and 0.5% of the TT group; in 25.8%, 6.7%, and 0.2% of the CT group; and in 29,1%, 5.5%, and 0.3% of the ST group.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Enrolled Patients

| Characteristics | Total (n=1,137) | 7d-TT (n=377) | 10d-CT (n=383) | 10d-ST (n=377) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 0.51* | ||||

| Mean±SD | 55.0±11.4 | 55.8±10.7 | 54.9±11.7 | 54.4±11.7 | |

| Median (range) | 56 (22–84) | 56 (27–79) | 56 (23–80) | 56 (22–84) | |

| Sex | 0.87† | ||||

| Male | 621 (54.6) | 208 (55.1) | 205 (53.5) | 208 (55.1) | |

| Female | 516 (45.3) | 169 (44.8) | 178 (46.4) | 169 (44.8) | |

| Smoking | 0.70† | ||||

| Never smoker | 729 (64.1) | 234 (62.0) | 254 (66.3) | 241 (63.9) | |

| Ex-smoker | 197 (17.3) | 70 (18.5) | 65 (16.9) | 62 (16.4) | |

| Current smoker | 211 (18.5) | 73 (19.3) | 64 (16.7) | 74 (19.6) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.61† | ||||

| Never drinker | 468 (41.1) | 150 (39.7) | 154 (40.2) | 164 (43.5) | |

| Ex-drinker | 118 (10.3) | 45 (11.9) | 40 (10.4) | 33 (8.7) | |

| Current drinker | 551 (48.4) | 182 (48.2) | 189 (49.3) | 180 (47.7) | |

| General medical history‡ | 498 (43.8) | 172 (45.6) | 160 (41.7) | 166 (44.0) | 0.56† |

| Past medical history of GI diseases§ | 840 (73.8) | 284 (75.3) | 280 (73.1) | 276 (73.2) | 0.73† |

| Family history of gastric cancer | 154 (13.5) | 58 (15.3) | 51 (13.3) | 45 (11.9) | 0.37† |

| Benign gastric ulcer | 183 (16.0) | 67 (17.7) | 56 (14.6) | 60 (15.9) | 0.49† |

| Benign duodenal ulcer | 132 (11.6) | 39 (10.3) | 43 (11.2) | 50 (13.2) | 0.43† |

| After ESD for EGC | 79 (6.9) | 32 (8.4) | 26 (6.7) | 21 (5.5) | 0.28† |

| MALT lymphoma | 6 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | 0.54* |

| Atrophic or metaplastic gastritis | 606 (53.3) | 212 (56.2) | 197 (51.4) | 197 (52.2) | 0.36† |

| Gastric adenoma | 72 (6.3) | 21 (5.5) | 28 (7.3) | 23 (6.1) | 0.60† |

| Gastric polypII | 66 (5.8) | 15 (3.9) | 22 (5.7) | 29 (7.6) | 0.09† |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | - | 1.00* |

| Helicobacter pylori (+) gastritis | 381 (33.5) | 116 (30.7) | 128 (33.4) | 137 (36.3) | 0.26† |

Data are presented as number (%).

7d, 7 days; TT, triple therapy; CT, concomitant therapy; ST, sequential therapy; GI, gastrointestinal; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; EGC, early gastric cancer; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

Fisher exact test;

Chi-square test;

General medical history includes hypertension, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver cirrhosis, renal failure, and any cancer except GI cancer;

Past medical history of GI diseases includes esophagitis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer, past history of abdominal surgery, gastrectomy, intractable iron deficiency anemia, chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, atrophic gastritis, and nonulcer dyspepsia;

Gastric polyp includes hyperplastic and inflammatory polyps.

2. Eradication efficacy of H. pylori

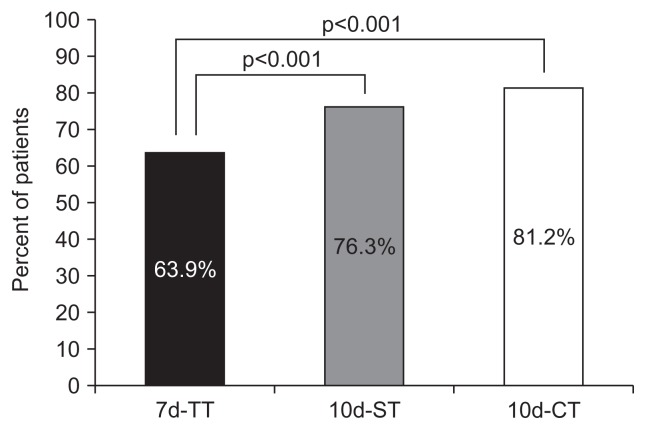

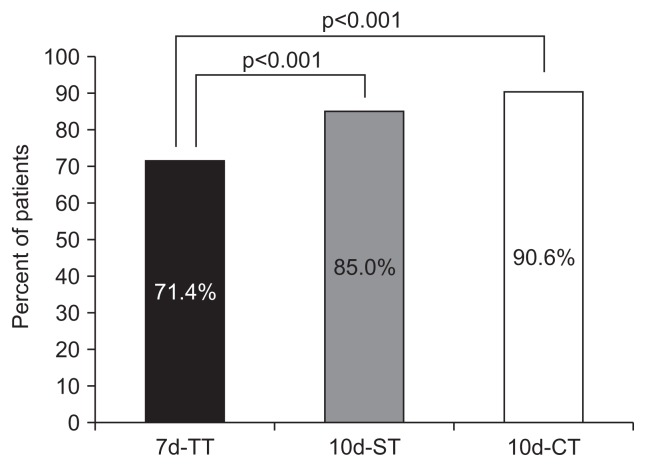

The primary goal was eradication rates of treatments by ITT and PP analysis. The 10d-CT and 10d-ST had a higher eradication rate than the 7d-TT. The 10d-CT achieved a markedly higher eradication rate than the 7d-TT. The eradication rates in the ITT analyses for the 7d-TT and 10d-CT groups were 63.9% and 81.2%, respectively (p<0.001) (Fig. 2). The eradication rates in the PP analyses for the 7d-TT and 10d-CT groups were 71.4% and 90.6%, respectively (p<0.001) (Fig. 3). The eradication rate of the 10d-ST was superior to that of 7d-TT. The eradication rates in the ITT analyses for the 7d-TT and 10d-ST groups were 63.9% and 76.3%, respectively (p<0.001). The eradication rates in the PP analyses for the 7d-TT and 10d-ST groups were 71.4% and 85.0%, respectively (p<0.001).

Fig. 2.

Eradication rates in the three treatment groups in the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis. In the ITT analysis, the eradication rate in the 10 days (10d)-ST group was significantly higher than that in the 7d-TT group (76.3% vs 63.9%, p<0.001). The eradication rate in the 10d-CT group was significantly higher than that in the 7d-TT group (81.2% vs 63.9%, p<0.001).

TT, triple therapy; ST, sequential therapy; CT, concomitant therapy.

Fig. 3.

Eradication rates in the three treatment groups in the per-protocol (PP) analysis. In the PP analysis, the eradication rate in the 10 days (10d)-ST group was significantly higher than that in the 7d-TT group (85.0% vs 71.4%, p<0.001). The eradication rate in the 10d-CT group was significantly higher than that in the 7d-TT group (90.6% vs 71.4%, p<0.001).

TT, triple therapy; ST, sequential therapy; CT, concomitant therapy.

3. Factors affecting H. pylori eradication

First, we identified age group, sex, treatment regimen, and compliance which were significant in the univariate analysis and verified whether those covariates are all statistically significant in the multiple logistic regression model. Especially, 10d-CT group has higher related with H. pylori eradication than the 7-d TT with statistical significance (odds ratio [OR], 3.40; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.34 to 4.94) (Table 2). Second, clinical factors such as treatment regimen, age, sex, and compliance were identified as risk factors associated with successfully eradicated and failed patients between 7d-TT and 10d-ST groups in the univariate logistic model. In multiple logistic model, 10d-ST has higher association with eradication rate than 7d-TT (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.50 to 2.95) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Factors Associated with Eradication Success (7d-TT vs 10d-CT)

| Characteristics | Eradication | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total (n=760) | Yes (n=552) | No (n=208) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Group | |||||||

| TT | 377 (100) | 241 (63.9) | 136 (36.1) | Reference | Reference | ||

| CT | 383 (100) | 311 (81.2) | 72 (18.8) | 2.43 (1.75–3.39) | <0.001 | 3.39 (2.33–4.94) | <0.001 |

| Age, yr | |||||||

| <60 | 480 | 361 (75.2) | 119 (24.8) | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥60 | 280 | 191 (68.2) | 89 (31.8) | 0.70 (0.51–0.98) | 0.030 | 0.63 (0.44–0.90) | 0.012 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 413 | 319 (77.2) | 94 (22.8) | Reference | 0.002 | Reference | |

| Female | 347 | 233 (67.1) | 114 (32.9) | 0.60 (0.43–0.83) | 0.56 (0.39–0.80) | 0.001 | |

| Compliance | |||||||

| <80 | 116 | 48 (41.4) | 68 (58.6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥80 | 644 | 504 (78.3) | 140 (21.7) | 5.10 (3.37–7.71) | <0.001 | 7.22 (4.57–11.41) | <0.001 |

| General medical history* | - | ||||||

| No | 428 | 317 (74.1) | 111 (25.9) | Reference | |||

| Yes | 332 | 235 (70.8) | 97 (29.2) | 0.84 (0.61–1.16) | 0.310 | ||

| Medical history of GI diseases† | - | ||||||

| No | 196 | 138 (70.4) | 58 (29.6) | Reference | |||

| Yes | 564 | 414 (73.4) | 150 (26.6) | 1.16 (0.81–1.66) | 0.410 | ||

| Family history of gastric cancer | - | ||||||

| No | 651 | 471 (72.4) | 180 (27.6) | Reference | |||

| Yes | 109 | 81 (74.3) | 28 (25.7) | 1.10 (0.69–1.75) | 0.670 | ||

| Concomitant medication | - | ||||||

| No | 439 | 327 (74.5) | 112 (25.5) | Reference | |||

| Yes | 321 | 225 (70.1) | 96 (29.9) | 0.80 (0.58–1.10) | 0.180 | ||

Data are presented as number or number (%).

7d, 7 days; TT, triple therapy; CT, concomitant therapy; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; GI, gastrointestinal.

General medical history includes hypertension, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver cirrhosis, renal failure, and any cancer except GI cancer;

Past medical history of GI diseases includes esophagitis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer, past history of abdominal surgery, gastrectomy, intractable iron deficiency anemia, chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, atrophic gastritis, and nonulcer dyspepsia.

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Factors Associated with Eradication Success

| Characteristics | Eradication | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total (n=754) | Yes (n=529) | No (n=225) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Group | |||||||

| TT | 377 | 241 (63.9) | 136 (36.1) | Reference | Reference | ||

| ST | 377 | 288 (76.4) | 89 (23.6) | 1.82 (1.32–2.50) | <0.001 | 2.10 (1.50–2.95) | <0.001 |

| Age, yr | |||||||

| <60 | 476 | 341 (71.6) | 135 (28.4) | Reference | |||

| ≥60 | 278 | 188 (67.6) | 90 (32.4) | 0.82 (0.60–1.14) | 0.246 | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 416 | 316 (75.9) | 100 (24.1) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 338 | 213 (63.0) | 125 (37.0) | 0.53 (0.39–0.73) | <0.001 | 0.57 (0.41–0.80) | 0.001 |

| Compliance | |||||||

| <80 | 106 | 43 (40.6) | 63 (59.4) | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥80 | 648 | 486 (75) | 162 (25) | 4.39 (2.86–6.73) | <0.001 | 4.79 (3.07–7.47) | <0.001 |

| General medical history* | |||||||

| No | 415 | 292 (70.4) | 123 (29.6) | Reference | |||

| Yes | 339 | 237 (70.0) | 102 (30.0) | 0.97 (0.71–1.33) | 0.890 | ||

| Medical history of GI diseases† | |||||||

| No | 195 | 138 (70.7) | 57 (29.2) | Reference | |||

| Yes | 559 | 391 (70.0) | 168 (30.0) | 0.96 (0.67–1.37) | 0.830 | ||

| Family history of gastric cancer | |||||||

| No | 651 | 456 (70.0) | 195 (30.0) | Reference | |||

| Yes | 103 | 73 (70.9) | 30 (29.1) | 1.04 (0.65–1.64) | 0.860 | ||

| Concomitant medication | |||||||

| No | 420 | 303 (72.1) | 117 (27.9) | Reference | |||

| Yes | 334 | 226 (67.7) | 108 (32.3) | 0.80 (0.59–1.10) | 0.180 | ||

Data are presented as number or number (%).

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; TT, triple therapy; ST, sequential therapy; GI, gastrointestinal.

General medical history includes hypertension, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver cirrhosis, renal failure, and any cancer except GI cancer;

Past medical history of GI diseases includes esophagitis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer, past history of abdominal surgery, gastrectomy, intractable iron deficiency anemia, chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, atrophic gastritis, and nonulcer dyspepsia.

4. Treatment compliance and adverse events

The secondary outcomes were treatment compliance and adverse events. The compliance with H. pylori eradication therapy of the 7d-TT, 10d-CT, and 10d-ST groups were 91.21, 86.0, and 88.0, respectively (p=0.004). At least one adverse event was recorded in 33.2% (n=378) of the 1,137 patients, and in total, 602 adverse events were recorded. The incidences of adverse events were 29.7% in 7d-TT, 36.5% in 10d-CT, and 33.4% in 10d-ST groups, respectively (Table 4). Diarrhea was the most common adverse event in all three treatment groups. Diarrhea (n=42), dysgeusia (n=36), and dyspepsia (n=12) were the most common adverse reactions in the 7d-TT group. Diarrhea (n=51), dysgeusia (n=34), and non-cardiac chest pain (n=23) were the most common adverse reactions in the 10d-CT group. Diarrhea (n=28), nausea (n=26), and dysgeusia (n=21) were the most common events in the 10d-ST group. However, there were no serious adverse events associated with the present study. There was little difference in serious side effects among the three treatment groups.

Table 4.

Adverse Events According to Regimen

| Adverse events | Total (n=602) | 7d-TT (n=166) | 10d-CT (n=243) | 10d-ST (n=193) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea | 121 | 42 | 51 | 28 |

| Dysgeusia | 91 | 36 | 34 | 21 |

| Nausea | 56 | 11 | 19 | 26 |

| Non-cardiac chest pain | 53 | 11 | 23 | 19 |

| Dyspepsia | 44 | 12 | 13 | 19 |

| Allergic reaction | 29 | 11 | 11 | 7 |

| Headache | 28 | 4 | 14 | 10 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 24 | 7 | 10 | 7 |

| Dizziness | 18 | 3 | 9 | 6 |

| Fatigue | 17 | 2 | 9 | 6 |

| Abdominal pain | 15 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| Others | 106 | 24 | 44 | 38 |

TT, standard triple therapy; CT, concomitant therapy; ST, sequential therapy.

DISCUSSION

This multicenter randomized controlled trial of three regimens for H. pylori eradication involved a large sample of patients recruited from the general populations in Korea. In particular, this is a nationwide, most systematic, and verifiable study that best represents Korea. In this clinical setting, we have demonstrated a higher eradication rate in both the 10d-CT and 10d-ST novel approaches.

Data demonstrate that 10d-CT achieves significantly higher eradication rates than 7d-TT, regardless of whether ITT or PP analysis is used. The eradication rate of 10d-CT and 10d-ST was higher than that of 7d-TT. There was little difference in serious adverse events among the three treatment groups.

H. pylori eradication is of great importance in preventing gastric cancer. In Japan, eradication treatment is allowed in all cases where H. pylori infection has been confirmed, since 2013. In Korea, the indication for H. pylori eradication is expanding, but the increase in the failure rate of the first-line eradication requires the development of a new first-line standard treatment. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale prospective study to present the optimal standard first-line treatment for H. pylori, which is suitable for domestic conditions in Korea.

Globally, the primary option for H. pylori eradication is clarithromycin-based TT, which includes a PPI and two antibiotics, amoxicillin and clarithromycin.9 Because the incidence of resistance to clarithromycin in H. pylori has been increasing, the eradication rates of TT have decreased to less than 80%, which is considered below the appropriate therapeutic range.30,31 To overcome the low eradication rate of clarithromycin therapy, many researchers have developed other therapeutic options such as prolonged treatment schedules or modified drug administration sequences including CT and ST.32

In Korea, no alternative treatment has been established so far to replace the 7d-TT. Instead, 7d- or 14d-clarithromycin-based TT is still recognized as the first-line therapy in the Korean national guidelines.5 Furthermore, Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service of the Korean government approves only 7d-TT as the first-line H. pylori therapy.33 Our previous study showed the regional difference in eradication rate as first-line treatment in Korea.11 One Korean study reported different rates of resistance to clarithromycin prepared using the agar dilution method, suggesting that different guidelines should be applied to eradicate H. pylori based on antibiotic resistance even within the same country or ethnic group.34

Recent studies have carried out randomized trials including bismuth-containing quadruple therapy, widely used as a second-line eradication therapy.23,35 In this trial, we compared all three currently used therapeutic regimens: 7d-TT, 10d-CT, and 10d-ST. In practical terms, comparisons among the three groups would result in more accurate results, but they would have to include more patients and take longer to implement.

CT includes the use of both PPI and three antibiotics at the same time, although it may lead to antibiotic abuse and unnecessary resistance. There was no difference in the clinical efficacy of CT in clarithromycin-sensitive and clarithromycin-resistant groups36 as well as in metronidazole-sensitive and metronidazole-resistant groups.37 In clinical practice, the concomitant regimen is much easier to take than the sequential one, which is a two-stage therapy with a drug switch halfway through the course. A meta-analysis revealed that CT was superior to TT, and there was no difference in the eradication rates of CT and ST (93.0% vs 93.1%, respectively).38 Unfortunately, there is little research data on CT in Korea.

ST was effective in case of clarithromycin resistance,39 metronidazole resistance,40 and even resistance to both clarithromycin and metronidazole.39 ST was reported to be more effective than 7d-TT in many Asian countries.35 However, the shortcoming of ST is that medications were changed during treatment and patients found it difficult to take them.32 A recent systematic review from six Korean randomized trials revealed that the overall eradication rates by ITT analysis were 65.9% for 7d-TT and 77.7% for ST.41 The overall eradication rates were 72.6% for 7d-TT and 84.5% for ST by PP analysis.

Overall, in this study, 10d-CT and 10d-ST showed superior clinical efficacy to 7d-TT as first-line therapy for H. pylori infection. Our data support those of previous study, as they demonstrate that the 10d-CT achieved a significantly higher eradication rate than the 10d-TT.42 From the ITT analysis, the eradication rate of the 10d-CT was 81.2% in our study, which was 17.3% better than that of the 7d-TT (p<0.001). In addition, comparison results of the 10d-ST and 7d-TT groups indicated that 10d-ST was 12.4% more effective than the 7d-TT (p<0.001). Until recently, results of the 10d-ST in Korea were found to be above the 7d-standard clarithromycin-containing TT.43 However, the 10d-ST demonstrated lower eradication rates than expected so far.44–46

Several studies have shown no difference in the effectiveness of CT and ST in clarithromycin and metronidazole-sensitive or clarithromycin and metronidazole-resistant groups.26,38 In this study, the eradication rate of CT appeared to be better than that of ST, although direct comparison was not possible.

Drug compliance is one of the important elements in determining the treatment outcome in bacterial eradication, especially for short-term treatment.26 In this study, three therapies were well tolerated and showed similar adverse event profiles and frequencies. In fact, 34.0% of the patients observed adverse events, which were minor or moderate.

Many studies have evaluated the factors affecting H. pylori eradication rates, such as antibiotic resistance, and various types of gastropathy, alcohol consumption, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and comorbidity.32 This study surveyed the results of both the successful and failed eradication according to each regimen comparison.

As regards age, sex, treatment regimen, compliance, general medical history except gastrointestinal system, medical history of gastrointestinal diseases, family history of gastric cancer, concomitant medication, the notable factors were treatment regimen, sex, and compliance. Interestingly, in this study, although men are more prone to eradication failure than women, the rate of eradication for women was lower than for men. Although metronidazole is widely used to treat gynecologic diseases and resistance to metronidazole frequently occurs in Korea, the reasons for the contradictory results were unclear.

The strength of this study is that it is the first nationwide large-scale randomized controlled trial assessing the efficacies of 10d-CT and 10d-ST versus a 7d-TT for treating H. pylori infection. Especially, this study represented the Korean population because it took into account regional distribution. Moreover, this study was conducted in Korea where the prevalence of H. pylori and gastric cancer is high. The fact that the research was conducted on a large scale through a nationwide network based on the Korean population with H. pylori infection and upper gastrointestinal research with the support of the Korean government is worth noting. Furthermore, a separate statistical and research management institution, Seoul National University Hospital Medical Research Collaboratory Center, was involved in providing professional analyses in this study.

This study has some limitations. First, we could not make a direct comparison of the eradication rate between 10d-CT and 10d-ST groups. Insufficient sample size for simultaneous comparison between the three groups made it impossible to directly compare 10d-CT and 10d-ST. Second, this study did not obtain any culture test result.

This trial provides evidence of the suboptimal efficacy of 7d-TT as the standard first-line treatment for H. pylori infection and that 10d-CT and 10d-ST were superior to 7d-TT in a country with clarithromycin resistance higher than 15%. The low eradication rates of the 7d-TT call for novel treatment options. In conclusion, novel therapies such as 10d-CT and 10d-ST can be recommended as alternative therapy for standard first-line treatment for H. pylori infection in Korea. Especially, 10d-CT may be the best new first-line alternative therapy for H. pylori infection in Korea. In addition, this study gives strong evidence of the adjustment of the Korean national guidelines for the treatment of H. pylori, which currently recommend TT as the first-line treatment for H. pylori infection. Furthermore, the results of this study could be used as a basis for changing Korea’s National Health Insurance standards in H. pylori eradication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HC15C1077).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.J.K. drafted the article. J.J.K., J.I.K., I.J.C., S.G.K., J.G.K. designed the study. J.L., J.K. were statistical advisors. J.G.K., Y.C.L., I.J.C., D.H.L., S.M.Y., J.K.S., S.W.K., H.S.K., S.W.J., J.Y.L., G.H.K., M.I.P., H.U.K., G.H.B., J.J.K. had leadership in each institute and collected data. H.L. contributed to coordination of the study. J.J.K. organized the study group. All the authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori update: gastric cancer, reliable therapy, and possible benefits. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:719–731. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavitt RT, Cifu AS. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection. JAMA. 2017;317:1572–1573. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asaka M, Kato M, Takahashi S, et al. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: 2009 revised edition. Helicobacter. 2010;15:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SG, Jung HK, Lee HL, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea, 2013 revised edition. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1371–1386. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gatta L, Vakil N, Vaira D, Scarpignato C. Global eradication rates for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of sequential therapy. BMJ. 2013;347:f4587. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JM, Kim JS, Jung HC, Kim N, Kim YJ, Song IS. Distribution of antibiotic MICs for Helicobacter pylori strains over a 16-year period in patients from Seoul, South Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4843–4847. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4843-4847.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6–30. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thung I, Aramin H, Vavinskaya V, et al. Review article: the global emergence of Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:514–533. doi: 10.1111/apt.13497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim BJ, Kim HS, Song HJ, et al. Online registry for nationwide database of current trend of Helicobacter pylori eradication in Korea: interim analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:1246–1253. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.8.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JW, Kim N, Kim JM, et al. Prevalence of primary and secondary antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Korea from 2003 through 2012. Helicobacter. 2013;18:206–214. doi: 10.1111/hel.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin WG, Lee SW, Baik GH, et al. Eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori in Korea over the past 10 years and correlation of the amount of antibiotics use: nationwide survey. Helicobacter. 2016;21:266–278. doi: 10.1111/hel.12279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung YS, Park CH, Park JH, Nam E, Lee HL. Efficacy of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapies in Korea: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12389. doi: 10.1111/hel.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, et al. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64:1353–1367. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG clinical guideline: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212–239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham DY, Dore MP, Lu H. Understanding treatment guidelines with bismuth and non-bismuth quadruple Helicobacter pylori eradication therapies. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2018;16:679–687. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1511427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Review article: non-bismuth quadruple (concomitant) therapy for eradication of Helicobater pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:604–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heo J, Jeon SW, Jung JT, et al. A randomised clinical trial of 10-day concomitant therapy and standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:980–984. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SY, Lee SW, Hyun JJ, et al. Comparative study of Helicobacter pylori eradication rates with 5-day quadruple “concomitant” therapy and 7-day standard triple therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:21–24. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182548ad4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3069–3079. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyssen OP, McNicholl AG, Megraud F, et al. Sequential versus standard triple first-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016:CD009034. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009034.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeo YH, Shiu SI, Ho HJ, et al. First-line Helicobacter pylori eradication therapies in countries with high and low clarithromycin resistance: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2018;67:20–27. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee H, Kim BJ, Kim SG, et al. Concomitant, sequential, and 7-day triple therapy in first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18:549. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2281-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Mitchell SA, et al. Validity and reliability of the US National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1051–1059. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu PI, Wu DC, Chen WC, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing 7-day triple, 10-day sequential, and 7-day concomitant therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:5936–5942. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02922-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gong EJ, Yun SC, Jung HY, et al. Meta-analysis of first-line triple therapy for helicobacter pylori eradication in Korea: is it time to change? J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:704–713. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.5.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choe JW, Jung SW, Kim SY, et al. Comparative study of Helicobacter pylori eradication rates of concomitant therapy vs modified quadruple therapy comprising proton-pump inhibitor, bismuth, amoxicillin, and metronidazole in Korea. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12466. doi: 10.1111/hel.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JS, Kim BW, Ham JH, et al. Sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Liver. 2013;7:546–551. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2013.7.5.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010;59:1143–1153. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham DY, Shiotani A. New concepts of resistance in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infections. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:321–331. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HJ, Kim JI, Lee JS, et al. Concomitant therapy achieved the best eradication rate for Helicobacter pylori among various treatment strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:351–359. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JW, Kim N, Kim JM, et al. A comparison between 15-day sequential, 10-day sequential and proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:917–924. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.896409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JH, Ahn JY, Choi KD, et al. Nationwide antibiotic resistance mapping of Helicobacter pylori in Korea: a prospective multicenter study. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12592. doi: 10.1111/hel.12592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kefeli A, Basyigit S, Yeniova AO, Kefeli TT, Aslan M, Tanas O. Comparison of three different regimens against Helicobacter pylori as a first-line treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2016;16:52–57. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2016.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webber MA, Piddock LJ. The importance of efflux pumps in bacterial antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:9–11. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okada M, Nishimura H, Kawashima M, et al. A new quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori: influence of resistant strains on treatment outcome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:769–774. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu DC, Hsu PI, Wu JY, et al. Sequential and concomitant therapy with four drugs is equally effective for eradication of H pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaira D, Zullo A, Vakil N, et al. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:556–563. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tong JL, Ran ZH, Shen J, Xiao SD. Sequential therapy vs. standard triple therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2009;34:41–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SW, Kim HJ, Kim JG. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:1001–1009. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.8.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Georgopoulos S, Papastergiou V, Xirouchakis E, et al. Nonbismuth quadruple “concomitant” therapy versus standard triple therapy, both of the duration of 10 days, for first-line H. pylori eradication: a randomized trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:228–232. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31826015b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park HG, Jung MK, Jung JT, et al. Randomised clinical trial: a comparative study of 10-day sequential therapy with 7-day standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in naïve patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:56–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi HS, Chun HJ, Park SH, et al. Comparison of sequential and 7-, 10-, 14-d triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2377–2382. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i19.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chung JW, Jung YK, Kim YJ, et al. Ten-day sequential versus triple therapy for Helicobacterpylori eradication: a prospective, open-label, randomized trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1675–1680. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oh HS, Lee DH, Seo JY, et al. Ten-day sequential therapy is more effective than proton pump inhibitor-based therapy in Korea: a prospective, randomized study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:504–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]