Abstract

目的

探讨SLE中CREMα表达升高的原因。

方法

分离5名正常对照和5名SLE患者的CD4+ T细胞,用染色质免疫沉淀(ChIP)微阵列法对各种基因启动子区组蛋白H3赖氨酸27三甲基化(H3K27me3)的水平进行分析。随后分离30名正常对照和30名SLE患者的CD4+ T细胞,用ChIP结合实时定量PCR检测CREMα启动子区H3K27me3、H3K27去甲基化酶JMJD3和UTX、H3K27甲基转移酶EZH2的水平,采用实时定量RT-PCR检测CREMα mRNA水平。

结果

SLE CD4+ T细胞的CREMα启动子区H3K27me3水平是正常对照的0.23倍。随后通过ChIP结合实时定量PCR,我们证实了SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K27me3水平显著降低(P<0.001),且与CREMα mRNA水平呈显著负相关(P<0.001)。该区的JMJD3水平显著升高(P<0.001),且与H3K27me3水平呈负相关(P<0.001),与CREMα mRNA水平呈正相关(P<0.001)。而UTX(P=0.172)及EZH2(P=0.281)水平则与对照组无明显差异。

结论

SLE CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区JMJD3增多,导致该区H3K27me3水平降低,结果促使CREMα过表达,最终引起SLE的发病。

Keywords: 系统性红斑狼疮, cAMP反应元件调控因子α, CD4+ T细胞, H3K27me3, JMJD3

Abstract

Objective

Increased cAMP response element modulator α (CREMα) in T cells plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The aim of this study was to investigate the mechanisms that elevates CREMα expression in SLE.

Methods

CD4+ T cells from 5 healthy volunteers and 5 SLE patients were isolated for analysis of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) enrichment in different gene promoters using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) microarray. The levels of H3K27me3, H3K27 demethylases Jumonji domain containing 3 (JMJD3) and ubiquitously transcribed X (UTX), and H3K27 methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) within the CREMα promoter were subsequently tested by ChIP and real-time PCR in CD4+ T cells from 30 normal controls and 30 SLE patients; CREMα mRNA level was also determined by real-time RT-PCR.

Results

Analysis of ChIP microarray data identified that H3K27me3 enrichment at the CREMα promoter in CD4+ T cells from SLE patients was 0.23 times that of the normal control subjects. The results of ChIP and real-time PCR confirmed a marked decrease of H3K27me3 enrichment at the CREMα promoter in CD4+ T cells from SLE patients (P < 0.001). The level of H3K27me3 at the promoter was negatively correlated with CREMα mRNA level in CD4+ T cells from SLE patients (P < 0.001). In addition, a sharp increase was observed in JMJD3 binding at the CREMα promoter region in CD4+ T cells from SLE patients (P < 0.001), and it was negatively correlated with H3K27me3 enrichment (P < 0.001) and positively correlated with CREMα mRNA level (P < 0.001). There were no significant changes in UTX (P=0.172) or EZH2 (P=0.281) binding at the CREMα promoter region in CD4+ T cells from SLE patients as compared to normal controls.

Conclusion

Increased JMJD3 binding down-regulates H3K27me3 enrichment at the CREMα promoter in CD4+ T cells of SLE patients to stimulate CREMα overexpression and result in the development of SLE.

Keywords: systemic lupus erythematosus, cAMP response element modulator α, CD4+ T cells, H3K27me3, JMJD3

系统性红斑狼疮(SLE)是一种慢性自身免疫性疾病,涉及到多重致病机制[1-2]。近年来,越来越多的研究证明了T细胞某些基因表观遗传学的改变在SLE的发病机制中起到了关键的作用[3-4]。表观遗传学指的是不涉及DNA序列变化的稳定且可遗传的基因表达改变,其机制主要包括DNA甲基化,组蛋白修饰,非编码RNA调控,以及染色质重塑[5-6]。而在这些表观遗传学调控机制中,作为基因沉默标志的组蛋白H3赖氨酸27三甲基化(H3K27me3)一直备受关注[6-7]。已知H3K27me3的水平由组蛋白去甲基化酶JMJD3 [8-9]、UTX [10-11]和组蛋白甲基转移酶EZH2 [12]共同参与调控。

研究发现cAMP反应元件调控因子α (CREMα)在SLE的发病机制中起到关键作用。CREMα水平在SLE患者的T细胞中显著升高,且CREMα启动子活性与SLE疾病活动指数(SLEDAI)呈正相关[13-15]。升高的CREMα可从多个方面促使SLE的发生与发展:首先,CREMα水平升高可导致IL-2减少,进而致使机体对细胞毒素反应的减弱,Treg细胞数目和功能的降低,以及活化诱导的细胞死亡(AICD)的缺陷[16-17];其次,CREMα水平升高还可导致IL-17A增加,而增加的IL-17A则会与多种趋化因子和细胞因子相互作用从而引发多重炎症反应[18];IL-17A也能刺激B细胞增殖,从而产生更多的自身抗体[15, 19-20];此外,CREMα的过表达能抑制TCR/CD3ζ链的转录从而阻碍其终止T细胞反应,导致T细胞持续活化;它还能抑制转录因子c-fos、抗原提呈细胞分子CD86、Notch信号通路分子Notch-1等而参与SLE的发病[21-24]。那么SLE患者T细胞CREMα水平升高的原因又是什么呢?

通过染色质免疫沉淀(ChIP)微阵列,我们发现SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区的H3K27me3水平显著低于正常对照。以此为线索,我们进一步探讨SLE CD4+ T细胞CREMα表达升高的原因,为揭示SLE的发病机制提供新的思路。

1. 资料和方法

1.1. 研究对象

30名SLE患者来自中南大学湘雅二医院皮肤科门诊及住院部。所有的患者均符合1997年美国风湿协会制订的SLE诊断标准[25]。SLE患者相关的临床信息见表 1。其中女性27例,男性3例,年龄20~42(28.567± 6.558)岁,SLEDAI评分0~16(7.567±4.384)分。30名正常对照均为中南大学湘雅二医院健康职工和研究生。其中女性27例,男性3例;年龄20~41(27.133± 6.067)岁。患者及正常对照年龄性别均无统计学差异(P>0.05),并均签署了知情同意书。本次研究获得了中南大学湘雅二医院伦理委员会的批准。

1.

患者资料表

Patient profiles

| Patient | Gender | Age (year) | SLEDAI | Medications |

| a: Prednisone; b: Hydroxychloroquine; c: Tripterygium glycoside. | ||||

| 1 | Female | 35 | 6 | Preda 30 mg/d |

| 2 | Female | 34 | 7 | None |

| 3 | Male | 28 | 6 | Pred 40 mg/d |

| 4 | Female | 32 | 4 | HCQb0.2 g/d |

| 5 | Female | 25 | 8 | Pred 50 mg/d |

| 6 | Female | 24 | 9 | Pred 30 mg/d |

| 7 | Female | 21 | 12 | None |

| 8 | Female | 23 | 8 | Pred 30 mg/d |

| 9 | Female | 25 | 15 | Pred 50 mg/d |

| 10 | Female | 29 | 3 | None |

| 11 | Female | 32 | 15 | Pred 40mg/d, TGc 30mg/d |

| 12 | Female | 23 | 2 | None |

| 13 | Female | 20 | 3 | Pred 5 mg/d |

| 14 | Female | 22 | 10 | Pred 30 mg/d, TG 30 mg/d |

| 15 | Female | 25 | 0 | None |

| 16 | Male | 40 | 10 | Pred 40mg/d, HCQ0.2 g/d |

| 17 | Female | 42 | 14 | Pred 40 mg/d, TG 30 mg/d |

| 18 | Female | 26 | 2 | HCQ 0.2 g/d |

| 19 | Female | 20 | 8 | None |

| 20 | Female | 35 | 12 | Pred 35 mg/d, HCQ0.2 g/d |

| 21 | Female | 37 | 16 | Pred 50 mg/d, TG 30 mg/d |

| 22 | Female | 26 | 10 | Pred 40 mg/d |

| 23 | Female | 24 | 8 | Pred 40 mg/d |

| 24 | Female | 28 | 4 | None |

| 25 | Female | 29 | 5 | TG 30 mg/d |

| 26 | Female | 34 | 8 | None |

| 27 | Male | 37 | 12 | Pred 40 mg/d |

| 28 | Female | 20 | 2 | HCQ 0.2 g/d |

| 29 | Female | 22 | 4 | Pred 30 mg/d |

| 30 | Female | 39 | 4 | Pred 30 mg/d |

1.2. 材料与试剂

淋巴细胞分离液购自瑞典GE Healthcare公司;CD4+ T细胞阳性分选试剂盒购自德国Miltenyi公司;ChIP试剂盒购自美国Millipore公司;TRIzol试剂购自美国Invitrogen公司;SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM(Tli RNaseH Plus)和One Step SYBR PrimeScriptTM RT-PCR试剂盒购自日本Takara公司;抗H3K27me3抗体购自美国Millipore公司;抗JMJD3抗体、抗UTX抗体和抗EZH2抗体购自美国Abcam公司;PCR引物由上海铂尚生物有限公司合成。

1.3. 细胞分离

抽取实验对象外周静脉血60 mL (用20 U/mL肝素抗凝),加入淋巴细胞分离液,采用密度梯度离心法分离外周血单个核细胞(PBMC)。所得PBMC加入PBS洗涤,随后使用免疫磁珠进行阳性分选获得CD4+ T细胞。

1.4. ChIP微阵列

使用1%的甲醛对5名SLE患者和5名年龄、性别均匹配的正常对照的CD4+ T细胞进行固定,随后使用裂解缓冲液对细胞进行裂解。SLE患者和正常对照细胞的裂解液分别进行混合,随后送至北京博奥生物有限公司。ChIP微阵列的质控、标记、杂交、扫描以及统计分析由博奥公司进行。抗H3K27me3抗体沉淀的DNA和总DNA (input)分别采用Cy5 (红色)和Cy3 (绿色)进行标记。标本随后杂交于微阵列板中,最后得到Cy3/Cy5比例图像。在这些图像中,不同的颜色强度代表各种基因启动子区相对的H3K27me3水平。与正常对照CD4+ T细胞相比,SLE CD4+ T细胞启动子区H3K27me3水平增加至2倍以上或减少至0.5倍以下被认为具有显著意义。

1.5. ChIP结合实时定量PCR

按照厂家说明书,采用ChIP试剂盒进行ChIP分析。简而言之,CD4+ T细胞使用1%甲醛固定10 min,随后使用裂解缓冲液进行裂解,并用超声波剪切细胞裂解液中的DNA,离心后取上清液。使用蛋白G琼脂糖珠去除非特异性背景后,加入抗体并在4 ℃中涡旋孵育过夜。次日,加入蛋白G琼脂糖珠并在4 ℃中涡旋孵育1 h以结合免疫复合物。琼脂糖珠-DNA-蛋白复合物经清洗后,再使用洗脱缓冲液将DNA-蛋白复合物洗脱出来,置于65 ℃中加热4 h以解除DNA和蛋白质之间的交联,随后将DNA进行纯化。使用SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM (Tli RNaseH Plus)试剂盒,通过标准曲线相对定量法进行实时定量PCR检测DNA水平。具体方法如下:以获得的DNA为模板进行扩增,同时取一份DNA样本,将其对倍稀释成5个梯度作为标准品,2/4/8/16/32倍稀释,以此产生标准曲线用于计算每一份样本的相对浓度,同时以input作为内参照。目的蛋白结合的DNA浓度相对于input DNA浓度的倍数即为相对定量的结果。所有实验重复3次。引物序列如下:CREMα启动子区上游引物:5'-TGGGGAGATAGAGGTTGCAG-3',下游引物5'-CGCCAGAAATCCAATGACTT-3'。反应条件为:95 ℃,30 s;95 ℃,10 s,60 ℃,15 s,72 ℃,20 s,共40次循环。

1.6. RNA抽提与实时定量一步法RT-PCR

按照厂家说明书,采用TRIzol对分离的CD4+ T细胞总RNA进行抽提,紫外/可见光分光光度计测定总RNA浓度及A260/A280比值。A260/A280比值均在1.8~2.0之间。所得RNA分装冻存于-80 ℃中。使用One Step SYBR PrimeScriptTM RT-PCR试剂盒,通过标准曲线相对定量法进行实时定量一步法RT-PCR检测mRNA水平。方法与前述的实时定量PCR类似,以CD4+ T细胞的RNA为模板,同时扩增β-actin作为内参照。同一标本目的基因的浓度相对于其β-actin的浓度的倍数即为相对定量的结果。所有实验重复3次。引物序列如下:CREMα上游引物5'-GAAACAGTTGAATCCCAGCATG ATGGAAGT-3',下游引物5'-TGCCCCGTGCTAGTC TGATATATG-3';β-actin上游引物5'-CGCGAGAAGAT TGACCCAGAT-3',下游引物5'-GCACTGTGTTGGCG TACAGG-3'。反应条件为:42 ℃,5 min;95 ℃,10 s;95 ℃,10 s,60 ℃,20 s,共40次循环。

1.7. 统计分析

采用SPSS 16.0 for windows统计软件储存和分析数据。计量资料以均数±标准差表示。两组独立样本均数之间进行比较采用两样本t检验,部分实验指标间作单因素直线相关分析,计算Pearson相关系数。P<0.05认为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. ChIP微阵列结果

在ChIP微阵列中,共筛查了20832个不同的基因启动子,其中552个基因启动子区H3K27me3水平在两组中差异达到2倍以上。在这些基因中,SLE CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K27me3水平是正常对照CD4+ T细胞的0.23倍。

2.2. ChIP微阵列结果验证

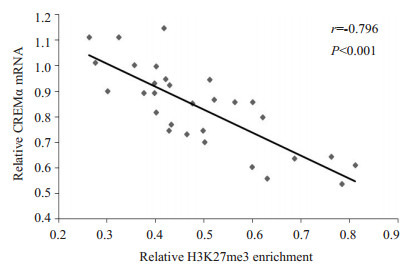

为了证实ChIP微阵列的结果,我们采用ChIP结合实时定量PCR检测了30名正常对照和30名SLE患者的CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K27me3的水平。相对于正常对照,SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K27me3水平显著降低(正常对照vs SLE患者:2.723±0.659 vs 0.489±0.146,P<0.001),这与我们的ChIP微阵列结果相符。我们进一步检测了SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα mRNA水平,结果证实了在SLE患者的CD4+ T细胞中,CREMα启动子区的H3K27me3与其mRNA水平呈负相关(r=-0.796,P<0.001,图 1)。

1.

SLE CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K27me3的水平与CREMα mRNA表达的相关

Correlation between H3K27me3 enrichment within the CREMα promoter in SLE CD4+ T cells and the levels of CREMα mRNA.

2.3. SLE患者和正常对照CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区JMJD3、UTX和EZH2水平

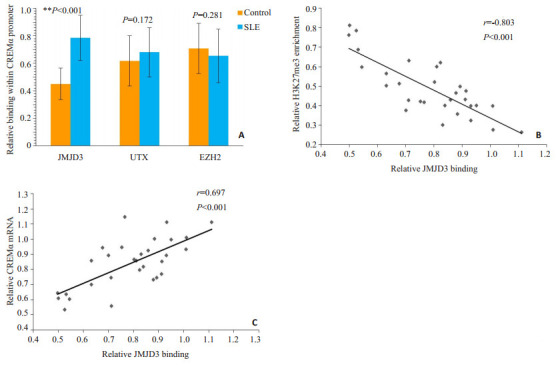

ChIP结合实时定量PCR结果显示,相对于正常对照,SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区JMJD3水平明显增加(P<0.001,图 2A)。且在SLE患者的CD4+ T细胞中,此区域的JMJD3水平与H3K27me3呈负相关(r=-0.803,P<0.001,图 2B),而与CREMα mRNA水平呈正相关(r=0.697,P<0.001,图 2C)。然而,SLE患者和正常对照CD4+ T细胞的CREMα启动子区UTX(P= 0.172)及EZH2 (P=0.281)水平并无明显差异(图 2A)。

2.

正常对照和SLE CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区JMJD3、UTX和EZHZ的水平及JMJD3与H3K27me3、CREMα水平的相关

Levels of JMJD3, UTX and EZH2 binding within the CREMα promoter region in CD4+ T cells from healthy controls and SLE patients and the correlations of JMJD3 with H3K27me3 and CREMα. A: Relative levels of JMJD3, UTX, and EZH2 within the HPK1 promoter region in healthy and SLE CD4+ T cells. B: Correlation between JMJD3 promoter binding and H3K27me3 level in SLE CD4+ T cells. C: Correlation between JMJD3 promoter binding and CREMα mRNA level in SLE CD4+ T cells.

3. 讨论

SLE患者发生自身免疫的关键在于CD4+ T细胞过度活化,进而刺激B细胞,结果导致各种自身抗体过度产生。而CD4+ T细胞某些免疫相关基因启动子区的表观遗传学改变则是CD4+ T细胞过度活化的重要原因。但目前的研究大多集中于DNA甲基化上[26-27],而对SLE CD4+ T细胞组蛋白修饰的探讨则非常有限。

已知H3K27me3能抑制基因的转录。它可与PRC1中的Pc蛋白结合,从而募集PRC1到染色质。PRC1可阻断转录活化因子及染色质重塑因子与DNA结合,并阻碍RNA聚合酶Ⅱ发动的转录;此外,PRC1还能与组蛋白去乙酰化酶相联,后者能抑制基因的转录;而且,PRC1和H3K27me3还能阻碍正性活化标志,例如H3K4的甲基化[28-29]。因此,H3K27me3一直是表观遗传学的研究热点之一。为了探讨SLE患者CD4+ T细胞的基因启动子区H3K27me3水平与正常对照有无差异,我们通过ChIP微阵列对正常对照和SLE患者的CD4+ T细胞各种基因启动子区的H3K27me3水平进行了检测和筛选,结果我们发现,SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K27me3的水平较低,这与SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα表达水平升高正相吻合。

近年来,CREMα在SLE中所起到的作用已得到了充分的研究和验证,然而,引起SLE T细胞CREMα增加的分子机制至今仍不清楚。ChIP微阵列的结果提示了我们,可能正是由于SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K27me3水平降低导致了CREMα水平升高。为此,我们首先通过ChIP结合实时定量PCR对ChIP微阵列的结果进行了验证,结果正如所料,SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K27me3的水平显著低于正常对照。而且,我们发现H3K27me3与CREMα mRNA的水平呈负相关。这些结果表明SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα水平升高的原因可能是因为其启动子区H3K27me3水平较低所致。

那么,SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K27me3水平降低的原因又是什么呢?前文已述,H3K27me3的水平由组蛋白去甲基化酶JMJD3、UTX和组蛋白甲基转移酶EZH2共同参与调控。于是我们采用ChIP结合实时定量PCR对这3种H3K27甲基化调控酶在CREMα启动子区的表达进行了检测,结果发现SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区JMJD3显著增加,且JMJD3与H3K27me3水平呈负相关,而与CREMα mRNA水平呈正相关。然而,SLE患者和正常对照CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区的UTX及EZH2水平无明显差异。

综合上述结果,我们的研究提示SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区JMJD3增加,这可导致此区域H3K27me3水平下降,从而促使CREMα增多,这一改变可能是引起SLE发病的重要机制之一。本研究为SLE的发病机理提供了新的理论依据,并为SLE的治疗提供了潜在的治疗靶点。

前文已述,H3K27me3能阻碍正性活化标志H3K4的甲基化。有趣的是,我们团队已证实了SLE患者CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K4me3的水平明显高于正常对照[30]。而本次试验中,我们又发现SLE CD4+ T细胞CREMα启动子区H3K27me3水平显著降低,这就使得我们联想到这二者之间是否有因果关系,还是相互独立的事件?还有待进一步的研究。

Biography

张庆,博士,助理研究员,E-mail: 245145077@qq.com

Funding Statement

国家自然科学基金(81301359)

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81301359)

Contributor Information

张 庆 (Qing ZHANG), Email: 245145077@qq.com.

张 慧琳 (Huilin ZHANG), Email: zhanghuilin8012@163.com.

References

- 1.Moulton VR, Holcomb DR, Zajdel MC, et al. Estrogen upregulates cyclic AMP response element modulator alpha expression and downregulates interleukin-2 production by human T lymphocytes. http://www.jimmunol.org/content/186/1_Supplement/167.8. Mol Med. 2012;18:370–8. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00506. [Moulton VR, Holcomb DR, Zajdel MC, et al. Estrogen upregulates cyclic AMP response element modulator alpha expression and downregulates interleukin-2 production by human T lymphocytes [J]. Mol Med, 2012, 18: 370-8.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenbrock K, Kyttaris VC, Ahlmann M, et al. The cyclic AMP response element modulator regulates transcription of the TCR zetachain. J Immunol. 2005;175(9):5975–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5975. [Tenbrock K, Kyttaris VC, Ahlmann M, et al. The cyclic AMP response element modulator regulates transcription of the TCR zetachain[J]. J Immunol, 2005, 175(9): 5975-80.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewagama A, Richardson B. The genetics and epigenetics of autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2009;33(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.03.007. [Hewagama A, Richardson B. The genetics and epigenetics of autoimmune diseases[J]. J Autoimmun, 2009, 33(1): 3-11.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan Y, Sawalha AH. Epigenetic regulation and the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Transl Res. 2009;153(1):4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.10.007. [Pan Y, Sawalha AH. Epigenetic regulation and the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Transl Res, 2009, 153(1): 4-10.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks WH, Le Dantec C, Pers JO, et al. Epigenetics and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2010;34(3):J207–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.006. [Brooks WH, Le Dantec C, Pers JO, et al. Epigenetics and autoimmunity[J]. J Autoimmun, 2010, 34(3): J207-19.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Q, Long H, Liao J, et al. Inhibited expression of hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 associated with loss of jumonji domain containing 3 promoter binding contributes to autoimmunity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2011;37(3):180–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.09.006. [Zhang Q, Long H, Liao J, et al. Inhibited expression of hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 associated with loss of jumonji domain containing 3 promoter binding contributes to autoimmunity in systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. J Autoimmun, 2011, 37(3): 180-9.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang P, Su Y, Lu Q. Epigenetics and psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(4):399–403. doi: 10.1111/jdv.2012.26.issue-4. [Zhang P, Su Y, Lu Q. Epigenetics and psoriasis[J]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2012, 26(4): 399-403.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong S, Cho YW, Yu LR, et al. Identification of JmjC domaincontaining UTX and JMJD3 as histone H3 lysine 27 demethylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(47):18439–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707292104. [Hong S, Cho YW, Yu LR, et al. Identification of JmjC domaincontaining UTX and JMJD3 as histone H3 lysine 27 demethylases [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2007, 104(47): 18439-44.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Santa F, Totaro MG, Prosperini E, et al. The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing. Cell. 2007;130(6):1083–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.019. [De Santa F, Totaro MG, Prosperini E, et al. The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing[J]. Cell, 2007, 130(6): 1083-94.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banka S, Lederer D, Benoit V, et al. Novel KDM6A (UTX) mutations and a clinical and molecular review of the X-linked Kabuki syndrome (KS2) Clin Genet. 2015;87(3):252–8. doi: 10.1111/cge.2015.87.issue-3. [Banka S, Lederer D, Benoit V, et al. Novel KDM6A (UTX) mutations and a clinical and molecular review of the X-linked Kabuki syndrome (KS2)[J]. Clin Genet, 2015, 87(3): 252-8.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi HJ, Park JH, Park M, et al. UTX inhibits EMT-induced breast CSC properties by epigenetic repression of EMT genes in cooperation with LSD1 and HDAC1. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(10):1288–98. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540244. [Choi HJ, Park JH, Park M, et al. UTX inhibits EMT-induced breast CSC properties by epigenetic repression of EMT genes in cooperation with LSD1 and HDAC1[J]. EMBO Rep, 2015, 16(10): 1288-98.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujii S, Ito K, Ito Y, et al. Enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) down-regulates RUNX3 by increasing histone H3 methylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(25):17324–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800224200. [Fujii S, Ito K, Ito Y, et al. Enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) down-regulates RUNX3 by increasing histone H3 methylation[J]. J Biol Chem, 2008, 283(25): 17324-32.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedrich CM, Rauen T, Kis-Toth K, et al. cAMP-responsive element modulator alpha (CREMalpha) suppresses IL-17F protein expression in T lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) J Biol Chem. 2012;287(7):4715–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.323261. [Hedrich CM, Rauen T, Kis-Toth K, et al. cAMP-responsive element modulator alpha (CREMalpha) suppresses IL-17F protein expression in T lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)[J]. J Biol Chem, 2012, 287(7): 4715-25.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedrich CM, Crispin JC, Rauen T, et al. cAMP response element modulator alpha controls IL2 and IL17A expression during CD4 lineage commitment and subset distribution in lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(41):16606–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210129109. [Hedrich CM, Crispin JC, Rauen T, et al. cAMP response element modulator alpha controls IL2 and IL17A expression during CD4 lineage commitment and subset distribution in lupus[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2012, 109(41): 16606-11.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauen T, Hedrich CM, Juang YT, et al. cAMP-responsive element modulator (CREM) alpha protein induces interleukin 17A expression and mediates epigenetic alterations at the interleukin-17A gene locus in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(50):43437–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.299313. [Rauen T, Hedrich CM, Juang YT, et al. cAMP-responsive element modulator (CREM) alpha protein induces interleukin 17A expression and mediates epigenetic alterations at the interleukin-17A gene locus in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. J Biol Chem, 2011, 286(50): 43437-46.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohl K, Wiener A, Schippers A, et al. Interleukin-2 treatment reverses effects of cAMP-responsive element modulator alpha-overexpressing T cells in autoimmune-prone mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;181(1):76–86. doi: 10.1111/cei.12629. [Ohl K, Wiener A, Schippers A, et al. Interleukin-2 treatment reverses effects of cAMP-responsive element modulator alpha-overexpressing T cells in autoimmune-prone mice[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2015, 181(1): 76-86.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez-Martin D, Diaz-Zamudio M, Crispin JC, et al. Interleukin 2 and systemic lupus erythematosus: beyond the transcriptional regulatory net abnormalities. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;9(1):34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.02.035. [Gomez-Martin D, Diaz-Zamudio M, Crispin JC, et al. Interleukin 2 and systemic lupus erythematosus: beyond the transcriptional regulatory net abnormalities[J]. Autoimmun Rev, 2009, 9(1): 34-9.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koga T, Hedrich CM, Mizui M, et al. CaMK4-dependent activation of AKT/mTOR and CREM-alpha underlies autoimmunityassociated Th17 imbalance. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(5):2234–45. doi: 10.1172/JCI73411. [Koga T, Hedrich CM, Mizui M, et al. CaMK4-dependent activation of AKT/mTOR and CREM-alpha underlies autoimmunityassociated Th17 imbalance[J]. J Clin Invest, 2014, 124(5): 2234-45.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crispin JC, Tsokos GC. IL-17 in systemic lupus erythematosus. https://www.mendeley.com/research-papers/il17-systemic-lupus-erythematosus-1/ J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:943254. doi: 10.1155/2010/943254. [Crispin JC, Tsokos GC. IL-17 in systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. J Biomed Biotechnol, 2010, 2010: 943254.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nalbandian A, Crispin JC, Tsokos GC. Interleukin-17 and systemic lupus erythematosus: current concepts. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157(2):209–15. doi: 10.1111/cei.2009.157.issue-2. [Nalbandian A, Crispin JC, Tsokos GC. Interleukin-17 and systemic lupus erythematosus: current concepts[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2009, 157(2): 209-15.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tenbrock K, Juang YT, Leukert N, et al. The transcriptional repressor cAMP response element modulator alpha interacts with histone deacetylase 1 to repress promoter activity. J Immunol. 2006;177(9):6159–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6159. [Tenbrock K, Juang YT, Leukert N, et al. The transcriptional repressor cAMP response element modulator alpha interacts with histone deacetylase 1 to repress promoter activity[J]. J Immunol, 2006, 177 (9): 6159-64.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rauen T, Grammatikos AP, Hedrich CM, et al. cAMP-responsive element modulator alpha (CREMalpha) contributes to decreased Notch-1 expression in T cells from patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) J Biol Chem. 2012;287(51):42525–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.425371. [Rauen T, Grammatikos AP, Hedrich CM, et al. cAMP-responsive element modulator alpha (CREMalpha) contributes to decreased Notch-1 expression in T cells from patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)[J]. J Biol Chem, 2012, 287(51): 42525-32.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verjans E, Ohl K, Yu Y, et al. Overexpression of CREMalpha in T cells aggravates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2013;191(3):1316–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203147. [Verjans E, Ohl K, Yu Y, et al. Overexpression of CREMalpha in T cells aggravates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury[J]. J Immunol, 2013, 191(3): 1316-23.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lippe R, Ohl K, Varga G, et al. CREMalpha overexpression decreases IL-2 production, induces a T(H)17 phenotype and accelerates autoimmunity. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4(2):121–3. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs004. [Lippe R, Ohl K, Varga G, et al. CREMalpha overexpression decreases IL-2 production, induces a T(H)17 phenotype and accelerates autoimmunity[J]. J Mol Cell Biol, 2012, 4(2): 121-3.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. http://pubmed.cn/9324032. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 1997, 40(9): 1725.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao M, Sun Y, Gao F, et al. Epigenetics and SLE: RFX1 downregulation causes CD11a and CD70 overexpression by altering epigenetic modifications in lupus CD4+ T cells. J Autoimmun. 2010;35(1):58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.02.002. [Zhao M, Sun Y, Gao F, et al. Epigenetics and SLE: RFX1 downregulation causes CD11a and CD70 overexpression by altering epigenetic modifications in lupus CD4+ T cells[J]. J Autoimmun, 2010, 35(1): 58-69.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Q, Wu A, Tesmer L, et al. Demethylation of CD40LG on the inactive X in T cells from women with lupus. J Immunol. 2007;179(9):6352–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6352. [Lu Q, Wu A, Tesmer L, et al. Demethylation of CD40LG on the inactive X in T cells from women with lupus[J]. J Immunol, 2007, 179(9): 6352-8.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lund AH, van Lohuizen M. Polycomb complexes and silencing mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16(3):239–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.010. [Lund AH, van Lohuizen M. Polycomb complexes and silencing mechanisms[J]. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2004, 16(3): 239-46.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kondo Y, Shen L, Cheng AS, et al. Gene silencing in cancer by histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation independent of promoter DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2008;40(6):741–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.159. [Kondo Y, Shen L, Cheng AS, et al. Gene silencing in cancer by histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation independent of promoter DNA methylation[J]. Nat Genet, 2008, 40(6): 741-50.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q, Ding S, Zhang H, et al. Increased Set1 binding at the promoter induces aberrant epigenetic alterations and up-regulates cyclic adenosine 5'-monophosphate response element modulator alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:126. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0294-2. [Zhang Q, Ding S, Zhang H, et al. Increased Set1 binding at the promoter induces aberrant epigenetic alterations and up-regulates cyclic adenosine 5'-monophosphate response element modulator alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Clin Epigenetics, 2016, 8: 126.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]