Abstract

目的

探讨上皮性卵巢癌 (EOC) 中八聚体结合转录因子4(OCT4)、Notch1及DLL4蛋白表达之间的关系及其功能意义。方法收集207例EOC术后标本和65例卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤标本,应用免疫组化学法检测EOC和卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤组织中OCT4、Notch1以及DLL4蛋白的表达情况。

结果

EOC组织和卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤组织中,OCT4、Notch1和DLL4蛋白的阳性表达率分别为60.0%、61.8%、60.9%和9.2%、6.2%、0,差异均有统计学意义 (P < 0.05);OCT4、Notch1和DLL4的表达与EOC的组织学分化、FIGO分期、盆腔淋巴结转移有关 (P < 0.05);DLL4蛋白的表达分别与OCT4和Notch1的表达呈正相关关系 (r值分别为0.758和0.704,P均 < 0.001),同时,OCT4与Notch1蛋白的表达亦呈正相关 (r=0.645,P < 0.001)。Kaplan-Meier生存分析表明,OCT4、Notch1和DLL4蛋白的过表达均与患者的生存率有关,3种蛋白表达阳性组患者生存率均明显低于蛋白表达阴性组患者 (P < 0.05)。多因素分析:OCT4、DLL4蛋白的表达和FIGO分期是影响EOC根治术后患者预后的独立因素 (P < 0.05)。

结论

OCT4、Notch1及DLL4的过表达与EOC的组织学分化程度、转移和预后等因素密切相关,联合检测这些指标可能对于EOC患者的病情进展和预后判断给予重要提示。

Keywords: 上皮性卵巢癌, 八聚体结合转录因子4, Notch1, DLL4, 预后

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the correlations among OCT4, Notch1 and DLL4 and their association with the clinicopathological features of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC).

Methods

A total of 207 specimens of EOC and 65 specimens of benign ovarian epithelial tumor tissues were examined for expressions of OCT4, Notch1 and DLL4 proteins using immunohistochemistry.

Results

The positivity rates of OCT4, Notch1 and DLL4 in EOC tissues were 60.0%, 61.8% and 60.9%, respectively, significantly higher than the rates in benign epithelial tumor tissues (9.2%, 6.2%, and 0, respectively; P < 0.05). The expressions of OCT4, Notch1 and DLL4 in EOC were significantly correlated with tumor differentiation, FIGO stage, and lymph node metastasis (P < 0.05). DLL4 was positively correlated with OCT4 and Notch1 expressions (r=0.758 and 0.704, respectively, P < 0.001), and the latter two were also positively correlated (r=0.645, P < 0.001). Overexpressions of OCT4, Notch1 and DLL4 were associated with a poor prognosis, and the survival rate was significantly lower in patients positive for OCT4, Notch1, and DLL4 than in the negative patients (P < 0.05). FIGO stage and expressions of OCT4 and DLL4 were independent prognostic factors of EOC (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

The expressions of OCT4, Notch1 and DLL4 are correlated with the differentiation, lymph node metastasis, clinical stage and prognosis of EOC. Combined detection of the 3 proteins has an important value in predicting the progression and prognosis of EOC.

Keywords: epithelial ovarian cancer, OCT4, Notch1, DLL4, prognosis

根据美国国家癌症研究所2014年统计数据报告,卵巢癌被认为是最致命的妇科恶性肿瘤,同时也是女性癌症死亡的第5大原因[1-2]。卵巢癌的高死亡率源于其病程发展过程中患者症状极为隐匿,多数病例在被诊断时疾病已广泛进展,导致患者预后很差[3]。在Ⅲ~Ⅳ期阶段,卵巢癌患者的5年生存率仅有30%左右[4]。上皮性卵巢癌 (EOC) 约占所有卵巢癌的90%左右,主要包括浆液性癌、黏液性癌、子宫内膜样癌和透明细胞癌,肿瘤组织侵袭和转移的特性是其高复发率和死亡率的主要原因[2]。因此,为了提高EOC患者生存预后,积极寻找新的分子标志物来预测患者复发和转移的风险,以及选择合适有效的治疗方案是至关重要的。

肿瘤的发生发展与肿瘤干细胞 (CSCs) 密切相关,肿瘤组织内存在少量的CSCs,它们具有自我更新、多向分化和不断增殖的能力,是肿瘤发生、发展、侵袭和转移的根源[5]。抑制CSCs生长可以减少肿瘤的发生,提高患者生存率,因此恶性肿瘤中干细胞相关基因成为近期研究的热点。八聚体结合转录因子4(OCT4) 一种重要的干细胞转录因子,属于POU (Pit-Oct-Unic) 蛋白家族的一员,其编码基因POU5f1位于6号染色体短臂6p21.33区[6]。OCT4基因具有5个外显子,4个内含子,通过与启动子区的八聚体基序 (结构为ATTTGCAT序列) 特异性结合,激活或抑制下游靶基因,调控基因表达,并维持干细胞的多潜能性及自我更新能力,被认为是干细胞的标志物之一[7]。Notch是一类进化上高度保守的跨膜蛋白家族,广泛表达于各类细胞表面,根据其编码的跨膜受体在胞内及胞外长度的不同而被命名为Notch1-Notch4(通常称Notch受体),其对应5种配体,根据配体间胞外区不同的重复序列,分别被命名为Delta1、Delta3、Delta4、Jagged1和Jagged2。Notch信号通路在肿瘤微环境内可发生异常活化,参与恶性肿瘤的侵袭和转移,这一过程主要是通过促进脉管系统的新生实现的,其中Notch1/DLL4受体通路是最重要的途径[8]。OCT4和Notch1/DLL4在肿瘤血管形成过程中均发挥着重要的作用,在恶性肿瘤中其表达水平的改变很有可能存在某些内在联系,如能通过有效地靶向恶性肿瘤的血管微环境、破坏CSCs,则很有可能达到更加有效治疗肿瘤的目的。现阶段,国内外尚无关于OCT4、Notch1和DLL4表达与卵巢癌恶性进展之间的关系及其相关机制的报道。本研究主要通过免疫组化方法检测207例EOC组织中OCT4、Notch1和DLL4蛋白表达,分析三者之间的相互关系,探讨它们与EOC侵袭、转移和预后的关系。

1. 资料和方法

1.1. 病例资料

收集安徽省蚌埠医学院第一附属医院病理科2005年1月~2011年12月存档EOC石蜡包埋组织标本207例 (患者术前未行放疗、化疗及其它抗肿瘤治疗) 和卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤组织标本65例,所有病例均具备完整的临床、病理及随访资料,入选病例随访至患者死亡或截止至2015年2月,随访时间为6~117个月。患者年龄18~75岁,中位年龄51.5岁,≥52岁109例, < 52岁98例。根据国际妇产科联盟关于卵巢癌FIGO 2014手术-病理分期,早期 (FIGOⅠ+Ⅱ期) 卵巢癌106例,晚期 (FIGOⅢ+Ⅳ期) 卵巢癌101例;浆液性癌155例,黏液性癌30例,子宫内膜样癌15例,透明细胞癌7例;高级别卵巢癌77例,低级别卵巢癌130例。肿瘤平均长径 (D) 7.92 cm,D≥8.0 cm 86例,D < 8.0 cm 121例。患者伴有盆腔淋巴结转移者80例,有腹水者85例,有腹腔种植者65例。同时选择65例良性上皮性卵巢肿瘤患者手术切除标本作为良性对照组。本实验经蚌埠医学院伦理委员会批准后进行的。复阅上述患者的病理切片,选取存档的患者手术标本石蜡块进行切片。

1.2. 主要试剂

兔抗人单克隆抗体OCT4和DLL4以及鼠抗人单克隆抗体Notch1均购自美国Abcam;ElivisionTM plus试剂盒和DAB显色试剂盒购自福州迈新生物技术有限公司。

1.3. 实验方法

所有EOC和对照组织标本均经由4%中性福尔马林溶液固定,石蜡包埋,4 μm厚度进行连续切片,后置于二甲苯溶液及梯度浓度的乙醇溶液脱蜡至水洗。免疫组织化学染色方法均按照ElivisionTM plus试剂盒说明书进行。DAB显色后进行水洗,后经苏木素复染细胞核、分化、返蓝、脱水透明并树胶封片。采用PBS液替代一抗作为阴性对照,选用已知OCT4、Notch1和DLL4染色阳性的切片进行阳性对照处理。

1.4. 结果判定

OCT4蛋白染色是以肿瘤细胞核内出现黄色或棕黄色颗粒为阳性;Notch1染色以肿瘤细胞膜和细胞质内出现黄色或棕黄色颗粒为阳性;DLL4染色则是以肿瘤细胞质出现黄色或棕黄色颗粒为阳性。三者的免疫组织化学结果主要通过着色的强度和范围综合计分得出,即0分为不着色,1分为淡黄色,2分为黄色,3分为棕黄色;随机选取10个高倍视野,计数阳性肿瘤细胞所占百分比, < 10%为0分,11%~25%为1分,26%~50%为2分,51%~75%为3分, > 75%为4分。两者相乘,得出积分结果,积分 < 3分为阴性,积分≥3分则为阳性。所有免疫组织化学标记结果均由两位病理医师采用独立双盲法来判定。

1.5. 统计学分析

本实验所有数据均使用SPSS20.0统计软件进行分析。EOC组中,OCT4、Notch1和DLL4蛋白表达阳性组与阴性组生存分析用Kaplan-Meier法,组间比较用log-rank检验,多因素分析采用Cox回归多因素模型,上述指标在EOC组织中表达与卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤组织以及各临床与病理因素的相关性采用χ2、Spearman等级相关及t检验等,检验水准均为0.05,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. OCT4在EOC组织中的表达及其与临床病理因素的关系

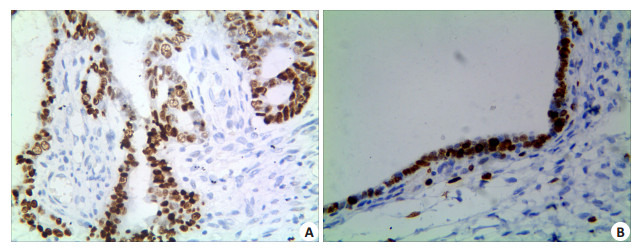

EOC组织中,OCT4蛋白的阳性表达率为60.0% (124/207),卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤组织中其阳性表达率为9.2%(6/65),两组间差异具有统计学意义 (P=0.000)。EOC组织OCT4蛋白的阳性表达率在高级别癌组要显著高于低级别癌组 (P=0.005);并且患者临床分期越晚,OCT4蛋白的阳性表达率越高,差异有统计学意义 (P= 0.000);伴有盆腔淋巴结转移的患者,OCT4蛋白的阳性表达率要高于无转移的患者,组间差异具有统计学意义 (P=0.001)。OCT4蛋白的阳性表达率与EOC患者的年龄、肿瘤直径、肿瘤的组织学类型以及是否伴有腹水和腹腔种植等因素之间差异均无统计学意义 (P > 0.05,图 1A、B,表 1)。

1.

OCT4在EOC及卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤组织的表达

Expression of OCT4 in EOC (A) and benign ovarian epithelial tumor (B) (Immunohistochemistry, original magnification: ×400).

1.

207例EOC组织中OCT4、Notch1及DLL4的表达与临床病理因素的关系

Correlation of OCT4, Notch1, and DLL4 expressions with the clinicopathological parameters of 207 patients with EOC

| Variable | OCT4 | Notch1 | DLL4 | |||

| Positive (%) | P | Positive (%) | P | Positive (%) | P | |

| Age (year) | ||||||

| < 52 | 62 (63.3%) | 0.395 | 66 (67.3%) | 0.152 | 61 (62.2%) | 0.776 |

| ≥52 | 62 (56.9%) | 62 (56.9%) | 65 (60.2%) | |||

| Diameter | ||||||

| < 8.0 cm | 71 (58.7%) | 0.774 | 76 (62.8%) | 0.773 | 74 (61.2%) | 1.000 |

| ≥8.0 cm | 53 (61.6%) | 52 (60.5%) | 52 (60.5%) | |||

| Histological type | ||||||

| Serous carcinoma | 96(61.9%) | 0.224 | 100 (64.5%) | 0.297 | 96(61.9%) | 0.270 |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 13 (43.3%) | 14 (46.7%) | 14 (46.7%) | |||

| Endometrioid carcinoma | 10 (66.7%) | 9 (60.0%) | 11 (73.3%) | |||

| Clear cell carcinoma | 5 (71.4%) | 5 (71.4%) | 5 (71.4%) | |||

| Grade | ||||||

| High grade carcinoma | 56 (72.7%) | 0.005 | 55 (71.4%) | 0.038 | 55 (71.4%) | 0.019 |

| Low grade carcinoma | 68 (52.3%) | 73 (56.2%) | 71 (54.6%) | |||

| FIGO stage | ||||||

| Ⅰ-Ⅱ | 45 (41.7%) | 0.000 | 55(51.9%) | 0.003 | 48 (45.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Ⅲ-Ⅳ | 79 (78.2%) | 73 (72.3%) | 78 (77.2%) | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| Yes | 59 (73.8%) | 0.001 | 58 (72.5%) | 0.013 | 57(71.3%) | 0.019 |

| No | 65 (51.2%) | 70 (55.1%) | 69 (53.4%) | |||

| Ascite | ||||||

| Yes | 48 (56.5%) | 0.471 | 48 (60.0%) | 0.194 | 46 (57.5%) | 0.112 |

| No | 76 (62.3%) | 80 (65.6%) | 80 (65.6%) | |||

| Intraperitoneal metastases | ||||||

| Yes | 44 (67.7%) | 0.130 | 41 (63.1%) | 0.878 | 44 (67.7%) | 0.220 |

| No | 80 (56.3%) | 87(61.3%) | 82 (57.7%) | |||

2.2. Notch1在EOC组织中的表达及其与临床病理因素的关系

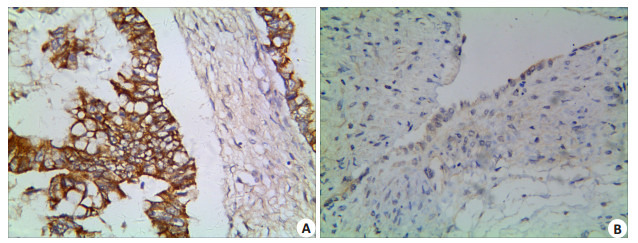

Notch1蛋白在EOC组织的阳性表达率为61.8% (128/207),在卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤组织中的阳性表达率为6.2%(4/65),并且良性肿瘤组Notch1蛋白表达强度较弱,差异有统计学意义 (P=0.000)。随着EOC组织学级别的增加,Notch1蛋白的阳性表达率也显著增加,差异具有统计学意义 (P=0.038);同时,伴随EOC组织FIGO期别的增高,Notch1蛋白的阳性表达率也显著增加,差异有统计学意义 (P=0.003);伴有淋巴结转移组中,Notch1蛋白的阳性表达率亦高于无转移组,差异亦具有统计学意义 (P=0.013)。EOC组织中,Notch1蛋白的阳性表达率与患者的年龄、肿瘤大小、组织学类型、有无腹水以及有无腹腔种植之间差异均无统计学意义 (P > 0.05,图 2A、B,表 1)。

2.

Notch1在EOC及卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤组织的表达

Expression of Notch1 in EOC (A) and benign ovarian epithelial tumor (B) (Immunohistochemistry, × 400).

2.3. EOC组织中DLL4的表达及其与临床病理因素的关系

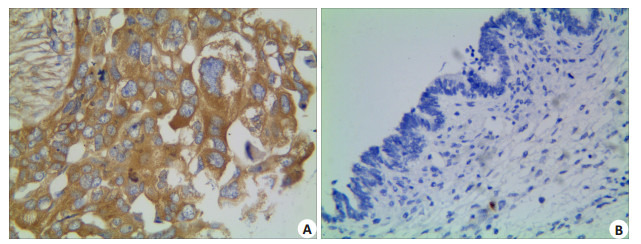

EOC组织的DLL4蛋白阳性表达率为60.9%(126/ 207),而卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤组织中DLL4无阳性表达0(0/65),组间差异具有统计学意义 (P=0.000)。DLL4蛋白的表达与EOC患者年龄、肿瘤大小、肿瘤组织学类型以及腹水和种植形成之间差异均无统计学意义 (P > 0.05)。随着EOC组织学分化程度的降低、患者临床FIGO分期的增加以及盆腔淋巴结的转移,肿瘤组织中DLL4蛋白阳性表达率显著增高,组间差异均有统计学意义 (P分别为0.019,0.000,0.019,图 3A、B,表 1)。

3.

DLL4在EOC及卵巢良性上皮性肿瘤组织的表达

Expression of DLL4 in EOC (A) and benign ovarian epithelial tumor (B) (Immunohistochemistry, ×400).

2.4. EOC组织中OCT4、Notch1及DLL4三者表达的相互关系

Spearman相关分析显示,DLL4蛋白的表达分别与OCT4和Notch1蛋白的表达呈正相关关系 (r值分别为0.758和0.704,P均 < 0.001),同时,OCT4与Notch1蛋白的表达亦呈正相关 (r=0.645,P < 0.001,表 2)。

2.

EOC中OCT4、Notch1及DLL4的表达之间的相互关系

Correlations of OCT4, Notch1, and DLL4 expressions in EOC

| Variable | OCT4 | r | Notch1 | r | ||

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | |||

| DLL4 | ||||||

| Negative | 70 | 11 | 0.758 | 65 | 16 | 0.704 |

| Positive | 13 | 113 | 13 | 113 | ||

| OCT4 | ||||||

| Negative | - | - | - | 63 | 20 | 0.645 |

| Positive | - | - | 15 | 109 | ||

2.5. Cox回归分析

将EOC患者年龄 (≥52岁组与 < 52岁组)、肿瘤直径 (≥8.0 cm组与 < 8.0 cm组)、肿瘤类型 (浆液性癌组、黏液性癌组、宫内膜样癌组及透明细胞癌组)、肿瘤组织学分化 (高级别癌组与低级别癌组)、FIGO分期 (Ⅰ+Ⅱ期组与Ⅲ+Ⅳ期组)、盆腔淋巴结转移 (转移组与无转移)、腹水 (腹水组与无腹水组)、腹腔种植 (种植组与无种植组)、OCT4蛋白表达 (阳性组与阴性组)、Notch1蛋白表达 (阳性组与阴性组)、DLL4表达 (阳性组与阴性组) 等因素引入Cox模型进行分析,结果显示:OCT4、DLL4和FIGO分期是影响EOC患者预后的独立因素 (表 3)。

3.

EOC患者多因素分析

Multivariate survival analysis of patients with EOC

| Covariate | B | SE | RR | 95% CI | P |

| Age | 0.126 | 0.152 | 1.134 | 0.841-1.528 | 0.409 |

| Diameter | 0.241 | 0.148 | 1.273 | 0.952-1.701 | 0.103 |

| Histo-type | 0.093 | 0.101 | 1.097 | 0.900-1.338 | 0.359 |

| FIGO | 0.680 | 0.168 | 1.973 | 1.421-2.742 | < 0.001 |

| Grade | 0.300 | 0.158 | 1.350 | 0.991-1.838 | 0.057 |

| LN metastesis | 0.145 | 0.152 | 1.156 | 0.858-1.556 | 0.341 |

| OCT4 | 0.959 | 0.271 | 2.608 | 1.533-4.437 | < 0.001 |

| Notch1 | 0.275 | 0.226 | 1.316 | 0.845-2.048 | 0.224 |

| DLL4 | 0.852 | 0.269 | 2.187 | 1.385-3.969 | 0.002 |

| Ascite | -0.073 | 0.164 | 0.930 | 0.674-1.282 | 0.657 |

| Plant | 0.190 | 0.176 | 1.209 | 0.856-1.708 | 0.282 |

2.6. 生存分析

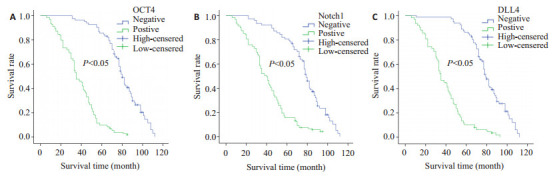

本组病例总的5年生存率为40.1%。Kaplan-Meier生存分析显示,OCT4蛋白表达阳性组与阴性组5年生存率分别为9.7%和85.5%,两组生存曲线差别有统计学意义,阳性组的生存率低于阴性组 (P < 0.001,图 4A);Notch1蛋白表达阳性组与阴性组5年生存率分别为15.5%和80.8%,两组之间生存曲线差别有统计学意义,阳性组的生存率高于阴性组 (P < 0.001,图 4B);DLL4蛋白表达阳性组与阴性组5年生存率分别为10.3%和86.4%,组间生存曲线差别有统计学意义,DLL4蛋白表达阳性组的生存率低于阴性组 (P < 0.001,图 4C)。

4.

EOC患者生存曲线

Survival curves of EOC patients (A: OCT4; B: Notch1; C: DLL4).

3. 讨论

侵袭、转移是恶性肿瘤最基本的生物学特征,也是导致患者死亡的重要因素之一。因此,寻找有效的治疗方法应对肿瘤的复发和转移一直是肿瘤治疗中的难点。肿瘤组织中含有极少一部分细胞,因其生长方式、生物学特性都与干细胞的基本特性相似,故被命名为肿瘤干细胞。根据肿瘤干细胞假说,它们是肿瘤的种子细胞,是肿瘤组织生长、繁衍的基础,也是最终导致恶性肿瘤复发和转移的根源[9]。OCT4是POU转录因子家族中的一员,该家族均具有相同的POU结构域,通过该区域与特异性的DNA序列结合可以激活靶基因的表达。OCT4不仅在胚胎干细胞和成体干细胞中呈现高表达,近年来,OCT4在肿瘤活体组织及肿瘤干细胞中表达的重要意义也受到众多学者的关注。研究显示,OCT4在肺腺癌、肝癌、结直肠癌、神经胶质细胞瘤、乳腺癌等多种肿瘤及肿瘤细胞系中均有表达[10-14],OCT4是维持肿瘤细胞的未分化性和自我更新潜能,参与肿瘤的形成与进展、导致肿瘤的化疗抵抗,以及影响患者的预后及生存的一种重要干细胞标记。Zhang等[15]通过对卵巢病变组织及正常输卵管上皮组织中OCT4表达的研究,发现OCT4在正常的卵巢上皮组织、卵巢良性肿瘤、交界性肿瘤和浆液性癌中表达依次增高,并且其表达程度与FIGO分期中的晚期阶段以及组织的低分化密切相关。Dai等[16]通过Oct4-shRNA-LV下调大肠癌OCT4基因的表达,在体外减慢了癌细胞的运动能力和侵袭性,在体内则降低了肝脏转移率,且在伴有肝转移的大肠癌患者中OCT4的表达水平要明显高于不伴有肝转移的患者,因此推测OCT4可以作为一种预测大肠癌患者是否可能肝转移危险性的标志物。本实验结果显示,EOC组中OCT4蛋白的表达阳性率显著高于良性对照组 (P < 0.05);高级别癌组织OCT4的阳性表达显著高于低级别癌,并且临床分期晚和伴有盆腔淋巴结转移的患者,OCT4蛋白的阳性表达率越高,组间差异均具有统计学意义 (P < 0.05)。这些研究结果与相关文献报道一致,提示OCT4高表达的EOC组织瘤细胞侵袭性更强,患者预后更差。

Notch信号通路广泛存在于脊椎动物和无脊椎动物的体内,参与细胞增殖、凋亡、迁移、血管发生和肿瘤侵袭等多种生物学过程[17]。Notch信号通路由受体、配体及DNA结合蛋白三部分组成,通过细胞间Notch受体与配体的结合进行信号传递[18]。在众多Notch受体家族成员中,Notch1的异常表达在肿瘤组织中最常被检测到。Notch1信号异常最早在急性T细胞淋巴细胞白血病/淋巴瘤中被发现,随后在诸如乳腺癌、头颈部鳞癌、非小细胞肺癌、胰腺癌、卵巢癌以及前列腺癌等实体瘤中也均被检测出存在其基因的突变[19]。有研究表明,Notch1在高分化肿瘤中表达水平下调,而在低分化的肿瘤中则显示其表达上调[20]。Notch信号通路促进肿瘤的侵袭和转移主要是依赖Notch1/DLL4受体通路来实现。DLL4基因定位于染色体15q14,是由685个氨基酸组成的Ⅰ型单次跨膜蛋白,其主要作用是调节血管出芽过程中端细胞和柄细胞比例,在血管和淋巴管的新生、发育、成熟以及肿瘤血管形成过程中具有关键作用[21]。Caolo[22]研究表明,通过Notch1/DLL4信号传递建立新血管萌芽和分支模式,同时联合其他信号通路共同调节相邻的细胞,促进卵巢上皮性恶性肿瘤发展。Notch1/ DLL4信号通路的作用是双方面的,一方面其促进血管发育和成熟,从而改善肿瘤血管的结构和功能,促进肿瘤的生长;另一方面其通过抑制血管的过度增殖减少肿瘤血管数量。阻断Notch1/DLL4信号,肿瘤组织可出现大量无功能的血管,导致局部组织缺血、缺氧,在DLL4过表达的区域,瘤组织内血管与侧支血管的吻合明显减少,肿瘤的血管化消失,但是肿瘤组织血管的结构和功能得以改善。由此可见,DLL4对肿瘤血管具有极其复杂的调节作用,通过诱导无效的非功能性血管生成,虽然增加了肿瘤血管密度,但却减少了组织灌注,这些无效的新生血管反而延缓和抑制了肿瘤的生长[22]。此外,DLL4还可显著抑制肿瘤干细胞的增殖,限制肿瘤生长发育。本实验结果显示,EOC组Notch1和DLL4蛋白的表达均显著高于良性对照组 (P < 0.05),并且随着EOC组织分化程度的降低及临床期别的增高,两者的蛋白阳性表达率显著增加,在伴有淋巴结转移组中Notch1和DLL4蛋白的阳性表达率亦高于无转移组,组间差异均具有统计学意义 (P < 0.05)。上述实验结果与文献报道具有一致性[23-24]。

多因素分析显示,OCT4和DLL4的表达以及FIGO分期是影响EOC根治术后患者预后的独立因素。这一结果可能为临床提供了新的EOC生物学行为相关的分子标志物。进一步的生存分析表明,OCT4和DLL4表达阳性组患者的5年生存率显著低于其表达阴性组,这一结果提示,OCT4和DLL4蛋白表达阳性率高的EOC患者,生存时间更短、预后更差。

EOC组织中,关于OCT4,Notch1和DLL4蛋白表达与其进展之间相关性的研究国内外未见文献报道。本实验Spearman相关分析显示,随着OCT4和Notch1的表达得增强,EOC组织DLL4表达显著增加,分别呈正相关关系,同时,OCT4和Notch1表达亦呈正相关关系。这一结果提示,EOC中OCT4、Notch1和DLL4的表达之间可能存在某种内在的联系。机体正常的组织细胞在各种致瘤因素的作用下恶变成为肿瘤细胞,其周围的肿瘤微环境为瘤细胞的生长和增殖提供了所需的各种营养成分,肿瘤细胞的数量得以不断扩增,而形成原发瘤。随着肿瘤不断增长,当直径大于1~2 μm时,微环境提供的养分已不能满足肿瘤继续增长所需,组织出现缺氧,肿瘤组织开始在多种分子的作用下诱发血管的生成以维持肿瘤的继续生长。一方面,肿瘤细胞的无限分裂增殖,呈现失控性生长,耗氧量巨大,致使代谢产物堆积;而另一方面,肿瘤内部血管生成的速度却不能够与瘤细胞增殖的速度相一致,这就使得肿瘤组织内的氧弥散性相对降低[25],进而导致这部分肿瘤组织处在缺氧的微环境之中。HIF作为缺氧环境下维持细胞内环境稳定的重要调节因子[26],HIF的表达上调可以通过诱导OCT4、NANOG、Sox2等干细胞标志物的表达,促进肿瘤干细胞的增殖、分化和自我更新[27];同时,HIF也可直接或通过一些间接途径调节Notch/DLL4信号通路,使肿瘤细胞具有侵袭和转移以及促进血管新生等特性,进而促进肿瘤的浸润进展[28]。上述机制表明,恶性肿瘤中的CSCs与Notch1/DLL4通路调节的微血管形成之间确实存在密切联系,而OCT4作为一种重要的肿瘤干细胞标记物,其表达水平的变化与Notch1和DLL4的表达在EOC的浸润进展过程中也可能存在某种共同促进作用,但这一推断是否成立,机制又如何,尚有待我们在进一步的实验中加以证实。

综上所述,随着EOC的快速生长,肿瘤组织内部出现了严重的缺血缺氧,CSCs受到诱导而大量增殖,并可能通过分泌某些化学因子刺激肿瘤局部形成一个具有新生血管的的微环境,同时肿瘤内部也通过启动诸如Notch/DLL4等一些信号通路促进肿瘤中微血管的新生,这也是造成EOC浸润和转移发生的关键步骤。因此,通过联合检测OCT4,Notch1和DLL4表达水平,有可能作为评估EOC患者生存预后情况的重要指标。

Funding Statement

安徽省高校自然科学研究重点项目 (KJ2017A224);安徽省高等学校省级优秀青年人才基金项目 (2012SQRL094);蚌埠医学院自然科学类重点项目 (BYKY1416ZD);国家级大学生创新训练项目 (201610367015)

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma JM, Zou ZH, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [Siegel R, Ma JM, Zou ZH, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2014, 64(1): 9-29.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Alem L, Curry J. Ovarian cancer: involvement of the matrix metalloproteinases. Reproduction. 2015;150(2):R55–64. doi: 10.1530/REP-14-0546. [Al-Alem L, Curry J. Ovarian cancer: involvement of the matrix metalloproteinases[J]. Reproduction, 2015, 150(2): R55-64.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui L, Kwong J, Wang CC. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells and disseminated tumor cells in patients with ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Simon_Cui/publication/278729065_Prognostic_value_of_circulating_tumor_cells_and_disseminated_tumor_cells_in_patients_with_ovarian_cancer_A_systematic_review_and_meta-analysis/links/55b2117708aec0e5f4314124.pdf. J Ovarian Res. 2015;8(8):38. doi: 10.1186/s13048-015-0168-9. [Cui L, Kwong J, Wang CC. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells and disseminated tumor cells in patients with ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Ovarian Res, 2015, 8(8): 38.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin L, Ware R, Huang B, et al. Ten-year relative survival for epithelial ovarian cancer. http://crisrf.uky.edu/documents/2012BaldwinTenYear%20Relative.pdf. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;121(1, 1):S34–5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318264f794. [Baldwin L, Ware R, Huang B, et al. Ten-year relative survival for epithelial ovarian cancer[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2011, 121(1, 1): S34-5.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zekri A-, Bahnassy A, El-Bastawisy AE, et al. Stem cells like phenotype of inflammatory breast cancer and locally advanced breast cancer: increased expression of sox2 and oct3/4 contributes to poor response to treatment and reduced survival rates. Cancer Res. 2014;74(19, S):4735. [Zekri A-, Bahnassy A, El-Bastawisy AE, et al. Stem cells like phenotype of inflammatory breast cancer and locally advanced breast cancer: increased expression of sox2 and oct3/4 contributes to poor response to treatment and reduced survival rates[J]. Cancer Res, 2014, 74(19, S): 4735.] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cauffman G, Liebaers I, Van Steirteghem A, et al. POU5F1 isoforms show different expression patterns in human embryonic stem cells and preimplantation embryos. Stem Cells. 2006;24(12):2685–91. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0611. [Cauffman G, Liebaers I, Van Steirteghem A, et al. POU5F1 isoforms show different expression patterns in human embryonic stem cells and preimplantation embryos[J]. Stem Cells, 2006, 24(12): 2685-91.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang J, Shakya A, Tantin DC, et al. Metabolism and cancer: a drama in two Octs. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34(10):491–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.06.003. [Kang J, Shakya A, Tantin DC, et al. Metabolism and cancer: a drama in two Octs[J]. Trends Biochem Sci, 2009, 34(10): 491-9.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia A, Kandel JJ. Notch: a key regulator of tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. http://m.doc88.com/p-9495299428837.html. Histol Histopathol. 2012;27(2):151–6. doi: 10.14670/hh-27.151. [Garcia A, Kandel JJ. Notch: a key regulator of tumor angiogenesis and metastasis[J]. Histol Histopathol, 2012, 27(2): 151-6.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garvalov BK, Acker T. Cancer stem cells: a new framework for the design of tumor therapies. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89(2):95–107. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0685-3. [Garvalov BK, Acker T. Cancer stem cells: a new framework for the design of tumor therapies[J]. J Mol Med (Berl), 2011, 89(2): 95-107.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khatri M, Goyal SM, Saif YM. Oct4(+) stem/progenitor swine lung epithelial cells are targets for influenza virus replication. J Virol. 2012;86(12):6427–33. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00341-12. [Khatri M, Goyal SM, Saif YM. Oct4(+) stem/progenitor swine lung epithelial cells are targets for influenza virus replication[J]. J Virol, 2012, 86(12): 6427-33.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin X, Li YW, Zhang BH, et al. Coexpression of stemness factors Oct4 and nanog predict liver resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(9):2877–87. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2314-6. [Yin X, Li YW, Zhang BH, et al. Coexpression of stemness factors Oct4 and nanog predict liver resection[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2012, 19 (9): 2877-87.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gazouli M, Roubelakis MG, Theodoropoulos GE, et al. OCT4 spliced variant OCT4B1 is expressed in human colorectal cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2012;51(2):165–73. doi: 10.1002/mc.20773. [Gazouli M, Roubelakis MG, Theodoropoulos GE, et al. OCT4 spliced variant OCT4B1 is expressed in human colorectal cancer [J]. Mol Carcinog, 2012, 51(2): 165-73.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.黄 健清. 小干扰RNA沉默OCT4基因表达对胰腺癌细胞株PANC1增殖与凋亡的影响. http://www.j-smu.com/oa/DArticle.aspx?type=view&id=201105860. 南方医科大学学报. 2011;31(5):860–3. [黄健清.小干扰RNA沉默OCT4基因表达对胰腺癌细胞株PANC1增殖与凋亡的影响[J].南方医科大学学报, 2011, 31(5): 860-3.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao SD, Yuan QH, Hao HB, et al. Expression of OCT4 pseudogenes in human tumours: lessons from glioma and breast carcinoma. J Pathol. 2011;223(5):672–82. doi: 10.1002/path.2827. [Zhao SD, Yuan QH, Hao HB, et al. Expression of OCT4 pseudogenes in human tumours: lessons from glioma and breast carcinoma[J]. J Pathol, 2011, 223(5): 672-82.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, Li YL, Zhou CY, et al. Expression of octamer-4 in serous and mucinous ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63(10):879–83. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.073593. [Zhang J, Li YL, Zhou CY, et al. Expression of octamer-4 in serous and mucinous ovarian carcinoma[J]. J Clin Pathol, 2010, 63(10): 879-83.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai X, Ge J, Wang X, et al. OCT4 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its knockdown inhibits colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232280843_OCT4_regulates_epithelial-mesenchymal_transition_and_its_knockdown_inhibits_colorectal_cancer_cell_migration_and_invasion. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(1):155–60. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2086. [Dai X, Ge J, Wang X, et al. OCT4 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its knockdown inhibits colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion[J]. Oncol Rep, 2013, 29(1): 155-60.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu WW, Jin GR, Long CD, et al. Blockage of notch signaling inhibits the migration and proliferation of retinal pigment epithelial cells. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Chongde_Long/publication/259878741_Blockage_of_Notch_Signaling_Inhibits_the_Migration_and_Proliferation_of_Retinal_Pigment_Epithelial_Cells/links/55f2908b08ae199d47c481ea.pdf?inViewer=0&pdfJsDownload=0&origin=publication_detail. Sci World J. 2013:178708. doi: 10.1155/2013/178708. [Liu WW, Jin GR, Long CD, et al. Blockage of notch signaling inhibits the migration and proliferation of retinal pigment epithelial cells[J]. Sci World J, 2013: 178708.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwanbeck R. The role of epigenetic mechanisms in notch signaling during development. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(5):969–81. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24851. [Schwanbeck R. The role of epigenetic mechanisms in notch signaling during development[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2015, 230(5): 969-81.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin CC, Ye JJ, Zou J, et al. Role of stromal cells-mediated Notch-1 in the invasion of T-ALL cells. Exp Cell Res. 2015;332(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.01.008. [Yin CC, Ye JJ, Zou J, et al. Role of stromal cells-mediated Notch-1 in the invasion of T-ALL cells[J]. Exp Cell Res, 2015, 332(1): 39-46.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reedijk M. Notch signaling and breast Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;727:241–57. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0899-4. [Reedijk M. Notch signaling and breast Cancer[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2012, 727: 241-57.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Fan F, Wang A, et al. Dll4-Notch signaling in regulation of tumor angiogenesis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(4):525–36. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1534-x. [Liu Z, Fan F, Wang A, et al. Dll4-Notch signaling in regulation of tumor angiogenesis[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2014, 140(4): 525-36.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noguera-Troise I, Daly C, Papadopoulos NJ, et al. Blockade of Dll4 inhibits tumour growth by promoting non-productive angiogenesis. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1032–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05355. [Noguera-Troise I, Daly C, Papadopoulos NJ, et al. Blockade of Dll4 inhibits tumour growth by promoting non-productive angiogenesis[J]. Nature, 2006, 444(7122): 1032-7.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caolo V, van den Akker NM, Verbruggen SA, et al. Feed-forward signaling by membrane-bound ligand receptor circuit: the case of NOTCH DELTA-like 4 ligand in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(52):40681–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.176065. [Caolo V, van den Akker NM, Verbruggen SA, et al. Feed-forward signaling by membrane-bound ligand receptor circuit: the case of NOTCH DELTA-like 4 ligand in endothelial cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 2010, 285(52): 40681-9.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu W, Lu CH, Han HD, et al. Biological roles of the delta family notch ligand Dll4 in tumor and endothelial cells in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(18):6030–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2719. [Hu W, Lu CH, Han HD, et al. Biological roles of the delta family notch ligand Dll4 in tumor and endothelial cells in ovarian cancer [J]. Cancer Res, 2011, 71(18): 6030-9.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canavese M, Spaccapelo R. Protective or pathogenic effects of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as potential biomarker in cerebral malaria. Pathog Glob Health. 2014;108(2):67–75. doi: 10.1179/2047773214Y.0000000130. [Canavese M, Spaccapelo R. Protective or pathogenic effects of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as potential biomarker in cerebral malaria[J]. Pathog Glob Health, 2014, 108(2): 67-75.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daşu A, Toma-Daşu I. The relationship between vascular oxygen distribution and tissue oxygenation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;645:255–60. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-85998-9. [Daşu A, Toma-Daşu I. The relationship between vascular oxygen distribution and tissue oxygenation[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2009, 645: 255-60.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koh MY, Powis G. Passing the baton: the HIF Switch. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37(9):364–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.06.004. [Koh MY, Powis G. Passing the baton: the HIF Switch[J]. Trends Biochem Sci, 2012, 37(9): 364-72.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathieu J, Zhang Z, Zhou W, et al. HIF induces human embryonic stem cell markers in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71(13):4640–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3320. [Mathieu J, Zhang Z, Zhou W, et al. HIF induces human embryonic stem cell markers in cancer cells[J]. Cancer Res, 2011, 71(13): 4640-52.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]