ROCK is a central kinase in cells that regulates numerous cellular functions, including cellular polarity, motility, proliferation, and apoptosis. Here we reveal a novel antiviral activity of ROCK during infection with HCMV, a prevalent pathogen infecting most of the population worldwide. We reveal ROCK1 is translocated to the nucleus, where it mainly localizes to the nucleolus. Our findings suggest that ROCK’s antiviral activity may be related to activation of the actomyosin network and inhibition of capsid egress out of the nucleus.

KEYWORDS: cytomegalovirus, cytoskeleton

ABSTRACT

Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK) protein is a central kinase that regulates numerous cellular functions, including cellular polarity, motility, proliferation, and apoptosis. Here, we demonstrate that ROCK has antiviral properties, and inhibition of its activity results in enhanced propagation of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV). We show that during HCMV infection, ROCK1 translocates to the nucleus and concentrates in the nucleolus, where it colocalizes with the stress-related chaperone heat shock cognate 71-kDa protein (Hsc70). Gene expression measurements show that inhibition of ROCK activity does not seem to affect the cellular stress response. We demonstrate that inhibition of myosin, one of the central targets of ROCK, also increases HCMV propagation, implying that the antiviral activity of ROCK might be mediated by activation of the actomyosin network. Finally, we demonstrate that inhibition of ROCK results in increased levels of the tegument protein UL32 and of viral DNA in the cytoplasm, suggesting ROCK activity hinders the efficient egress of HCMV particles out of the nucleus. Altogether, our findings illustrate ROCK activity restricts HCMV propagation and suggest this inhibitory effect may be mediated by suppression of capsid egress out of the nucleus.

IMPORTANCE ROCK is a central kinase in cells that regulates numerous cellular functions, including cellular polarity, motility, proliferation, and apoptosis. Here we reveal a novel antiviral activity of ROCK during infection with HCMV, a prevalent pathogen infecting most of the population worldwide. We reveal ROCK1 is translocated to the nucleus, where it mainly localizes to the nucleolus. Our findings suggest that ROCK’s antiviral activity may be related to activation of the actomyosin network and inhibition of capsid egress out of the nucleus.

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a ubiquitous betaherpesvirus, is a major cause of birth defects and an opportunistic pathogen in immunosuppressed individuals (1). Following HCMV entry, the viral capsid is translocated to the nucleus, where the genome is replicated and packaged into capsids. The capsids then traverse the nuclear membranes into the cytoplasm, where the virus completes its tegumentation and envelopment before budding out of the cell. This complex cycle requires the exploitation of many cellular pathways, and therefore many host factors were found to be essential for the production of newly infectious virions. However, only a few cellular proteins outside the designated innate immune response milieu are known to block HCMV propagation at late stages of infection.

We previously integrated translation efficiency measurements with measurements of protein abundance during HCMV infection to identify 65 cellular proteins that exhibited profiles during HCMV infection befitting active degradation (2). Since targeted degradation may indicate biological importance, we hypothesized that some of these proteins may act as novel HCMV restriction factors. One of the proteins we identified was the Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase 1 (ROCK1) protein (2). ROCK1 and its homologue, ROCK2, are serine/threonine kinases that were initially identified as activated Rho (Rho-GTP)-interacting proteins (3) and are known today to be the major downstream effectors of the small GTPase RhoA. ROCKs can also be activated, independently of Rho, by several lipids and by oligomerization—possibly through amino-terminal transphosphorylation (3).

Upon activation, ROCKs function as versatile kinases, regulating a plethora of cellular processes, including cellular polarity, motility, proliferation, and apoptosis (3–5). One of the best-characterized roles of ROCKs is regulation of actin filament assembly and contractility. This is achieved by phosphorylation of different substrates, including LIM kinase, myosin light chain (MLC), and MLC phosphatase (5). Phosphorylation of LIM kinase leads to stabilization of actin filaments, while phosphorylation of the MLC and inactivation of MLC phosphatase enhance the activity of the motor protein myosin. As a consequence, ROCK activity enhances actin-myosin contraction (4, 6).

In this study, we examined ROCK’s function during HCMV infection. By using specific inhibitors and genetic knockdown, we reveal that ROCK activity inhibits HCMV propagation. We further demonstrate that during HCMV infection, ROCK1 is recruited to the nucleolus. We show that ROCK antiviral activity may be mediated by hyperactivation of actin-myosin contraction, as the myosin inhibitor blebbistatin also increased HCMV titers. Finally, we demonstrate that inhibition of ROCK activity enhances nuclear viral egress. Altogether, our findings suggest that ROCK antiviral activity might be related to regulation of the actomyosin network, which affects the budding of viral capsids out of the nucleus.

RESULTS

ROCK inhibition promotes HCMV propagation.

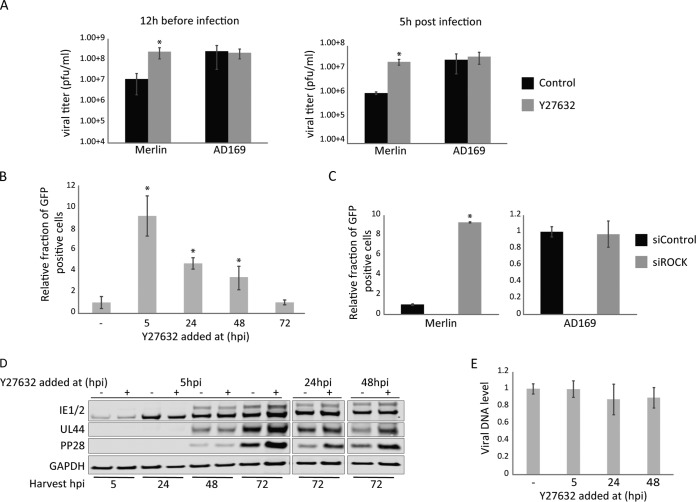

Integration of protein production levels (as measured by ribosome profiling) with protein abundance measurements during HCMV infection suggested that Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase 1 (ROCK1), a key regulator of actomyosin network and cell polarity, might be degraded during HCMV infection (2) (presented in Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). To confirm these genome-wide measurements, we previously demonstrated that the RNA levels of ROCK1 were slightly increased during HCMV infection, whereas ROCK1 protein levels, as measured by immunoblotting, were reduced (2) (Fig. S1B), supporting our initial hypothesis that ROCK1 might be degraded during HCMV infection. Since targeted degradation may indicate biological importance, we wanted to test whether the activity of ROCK1 is important for HCMV propagation. To this end, we infected human foreskin fibroblasts with the HCMV Merlin strain and at 12 h before infection or 5 h postinfection (hpi), the cells were treated with a potent and widely used ROCK inhibitor, Y27632 (7). Importantly, inhibition of ROCK resulted in more than a 10-fold increase in viral titers (Fig. 1A), suggesting ROCK activity inhibits HCMV propagation. We previously showed the reduction in ROCK1 protein level occurred only when cells were infected with the HCMV Merlin strain but not when cells were infected with the HCMV laboratory-adapted strain AD169, in which 15 kb comprising the ULb′ region (genes encoding UL133 to UL150) is deleted (2). We, therefore, tested the effect of ROCK inhibition on AD169 propagation. In support of a substantial difference between these two HCMV strains and in agreement with previous findings (8), inhibition of ROCK activity had no effect on AD169 titers (Fig. 1A). We next used an HCMV Merlin strain that contains a green fluorescent protein-tagged UL32 (UL32-GFP) (9), which allows for fluorescence-based monitoring of progeny virions’ production. Fibroblasts were infected with Merlin UL32-GFP, and ROCK inhibitor was added at different times postinfection. Supernatants were collected at 5 days postinfection (dpi) and used to infect fresh wild-type fibroblasts, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells was measured by microscopy and flow cytometry, as a proxy for viral titers. Utilizing this approach, we could show that inhibiting ROCK activity even at 48 hpi can increase viral propagation (Fig. 1B; Fig. S1C). Furthermore, inhibition of ROCK by a different, more selective inhibitor, H1152 (10), also resulted in increased viral titers, indicating that this result is not due to off-target effects of the drug (Fig. S1D and E). We further established the effect of ROCK inhibition on viral titers by knocking down ROCK expression using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). We confirmed that ROCK knockdown (KD) led to a significant reduction in ROCK1 protein expression (Fig. S1F). In accordance with our findings using drugs, ROCK KD resulted in a significant increase in viral titers following infection with the Merlin strain but not with the AD169 strain (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

ROCK activity inhibits HCMV propagation. (A) Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin or AD169 HCMV strain, and the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 or DMSO (as control) was added 12 h before infection or 5 h postinfection. Supernatants were collected 5 dpi, and viral titers were measured by TCID50 assay. (B) Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin UL32-GFP strain and were either treated with Y27632 at 5, 24, 48, and 72 hpi or treated with DMSO as a control. Supernatants were collected at 5 dpi and were used to infect fresh fibroblasts. Viral titers were quantified by measuring the percentage of GFP-positive cells at 72 hpi using FACS. (C) Fibroblasts were transfected with an siRNA pool targeting ROCK1 and -2 or a control siRNA pool. Eighteen hours posttransfection, cells were infected with Merlin UL32-GFP or AD169-GFP at an MOI of 3. Supernatants were collected 5 dpi and were used to infect fresh fibroblasts. Viral titers were quantified by measuring the percentage of GFP-positive cells using FACS. (D and E) Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin strain, and ROCK inhibitor (Y27632) was added at 5, 24, and 48 hpi. (D) Proteins were extracted at the indicated times and analyzed by Western blot analysis with IE1/2, UL44, and PP28 serving as the immediate early, early, and late gene markers, respectively. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (E) DNA was extracted 72 hpi and quantified by real-time PCR using primers for UL55. DNA levels were normalized to the human B2M gene. Means and error bars (showing standard deviations) represent triplicates. *, P < 0.05 by two-sided Student's t test.

To define the infection stage affected by ROCK activity, infected cells were treated with ROCK inhibitor and viral protein levels were examined at different time points postinfection (Fig. 1D). Compared to the control sample, we observed an elevation in the levels of early and late viral proteins (UL44 and pp28) only at 72 hpi, indicating ROCK activity might inhibit late stages of HCMV propagation. Interestingly, transcript levels of these genes showed only a mild increase (Fig. S1G). In agreement with a potential late inhibitory effect, we did not observe major differences in the levels of viral DNA replication when ROCK activity was inhibited (Fig. 1E).

ROCK1 is translocated to the nucleolus during HCMV infection.

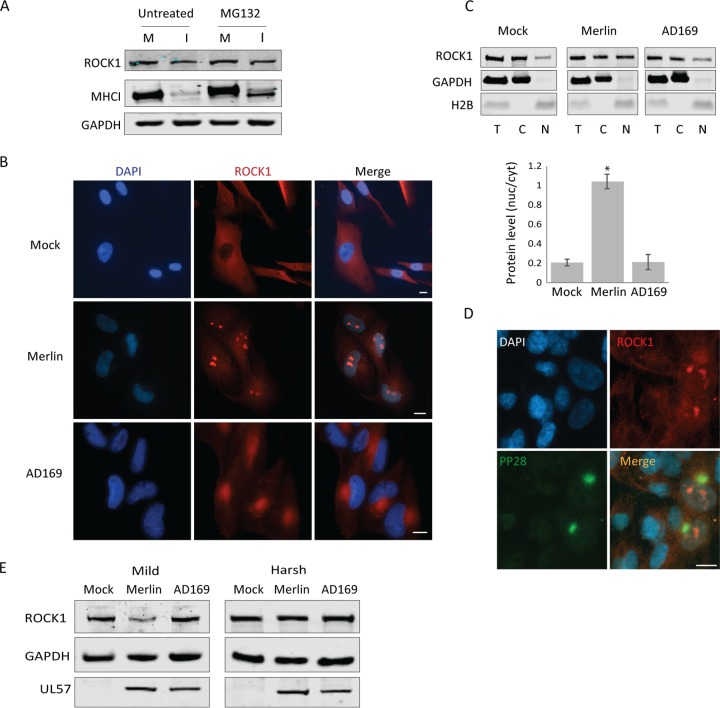

Given ROCK’s antiviral activity, we sought to determine if ROCK1 is indeed actively degraded in HCMV-infected cells. Cells were infected with the Merlin strain and were then treated with inhibitors of the proteasome (MG132) or lysosome (folimycin). Surprisingly, inhibition of proteasomal or lysosomal degradation did not affect the levels of ROCK1 as assessed by immunoblotting (Fig. 2A) (data not shown), indicating that ROCK1 might not be actively degraded by the proteasome or lysosome in HCMV-infected cells.

FIG 2.

ROCK1 relocalizes to the nucleus after infection with the HCMV Merlin strain. (A) MG132 was added to mock-infected (M) or Merlin-infected (I) cells at 72 hpi for 5 h, and the levels of ROCK1 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I (MHCI), which was used as a positive control, were analyzed by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Fluorescent microscopy images of mock-infected fibroblasts (top) or fibroblasts infected with the Merlin (middle) or AD169 (bottom) HCMV strain and stained with DAPI (blue) and ROCK1 antibody (red) at 72 hpi. Scale bars are 10 μm. (C) Subcellular localization of ROCK1 protein was examined by cellular fractionation at 72 hpi, separating between the cytosol and nuclear fractions. Equivalent amounts of proteins from the total (T), cytosolic (C), and nuclear (N) fractions were analyzed by Western blotting for ROCK1, GAPDH (cytosolic marker), and histone H2B (nuclear marker). Quantification of the ratios of nuclear and cytosolic ROCK1 from two independent experiments is presented. Error bars show standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 compared to the appropriate control by two-sided Student's t test. (D) RPE cells were infected with the HCMV Merlin strain and at 72 hpi stained with DAPI (blue), PP28 (green), and ROCK1 (red). The scale bar is 10 μm. (E) Total protein from uninfected fibroblasts or fibroblasts infected with the Merlin or AD169 strain was extracted 72 hpi using mild or harsh lysis buffers. ROCK1, GAPDH, and UL57 protein levels were detected by Western blot analysis.

We therefore aimed to confirm the reduction in ROCK1 protein levels detected by Western blot analysis, by an alternative method, and to inspect its localization during HCMV infection. We probed for ROCK1 expression using immunofluorescence in mock-infected cells and in cells infected with the Merlin or AD169 strain. Remarkably, infection with Merlin resulted in translocation of ROCK1 into well-defined nuclear domains, while in AD169-infected cells, ROCK1 was visualized mostly in the viral assembly compartment (Fig. 2B). The localization to the viral assembly compartment, but not to the nucleus, was probably due to nonspecific cross binding of the rabbit antibody, as a similar pattern was seen when using an unrelated rabbit antibody (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Subcellular fractionation and immunoblotting analysis further confirmed that in mock- and AD169-infected fibroblasts, ROCK1 was predominantly located in the cytoplasmic fractions, whereas in Merlin-infected fibroblasts, a significant portion of ROCK1 was detected in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 2C). Notably, the reduction in ROCK1 levels we measured by immunoblotting at least partially coincided with the timing of its nuclear translocation (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). We further tested if this translocation of ROCK1 into the nucleus occurs in additional cell types. Epithelial RPE-1 cells were infected with the Merlin strain. The infection efficiency was probed by staining for viral protein pp28, which is concentrated in the viral assembly compartment. Although, as expected, the infection of RPE cells was very inefficient (11, 12), in infected cells (identified by staining for the viral protein pp28), ROCK1 was also observed in nuclear domains (Fig. 2D).

Since our previous immunoblot analysis suggested that ROCK1 protein levels are reduced during HCMV infection (2) (Fig. S1B), we hypothesized that the nuclear puncta we observed by microscopy might be partially insoluble and therefore affected our ability to detect ROCK1 protein in infected cells using immunoblotting. To test this hypothesis, we harvested mock-infected cells and cells infected with the Merlin or AD169 HCMV strain and lysed them using mild or harsh lysis conditions. When using mild lysis conditions, the detection of ROCK1 by immunoblotting was reduced in cells infected with the Merlin strain, but not with AD169 strain, compared to mock-infected cells (Fig. 2E). This reduction in ROCK1 detection was not simply due to inefficient extraction of nuclear fractions, as we obtained comparable levels of UL57, a viral protein that resides in the nuclear replication compartment. When harsh lysis conditions were used, we did not detect any reduction in ROCK1 expression (Fig. 2E), supporting the assumption that the puncta-localized ROCK1 is at least partially insoluble.

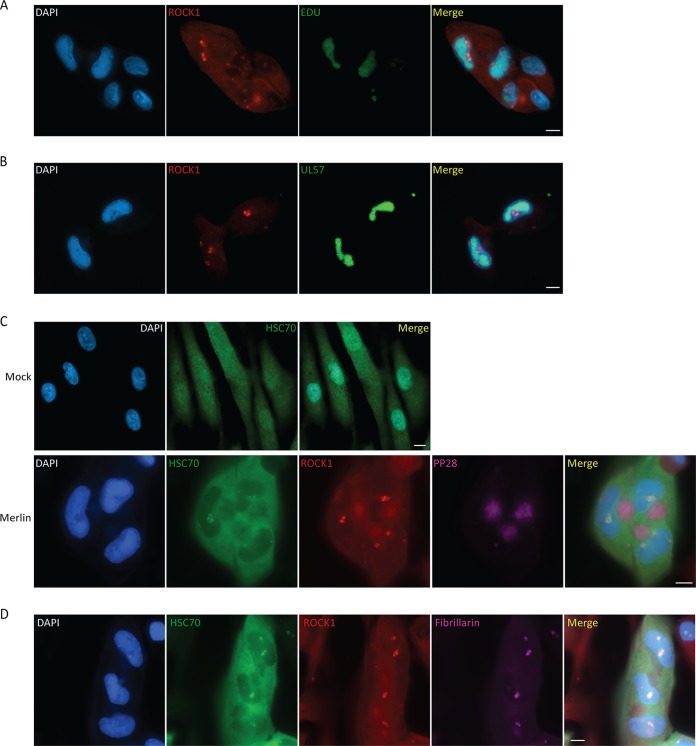

ROCK1 colocalizes with Hsc70 at the nucleolus in HCMV-infected cells.

In HCMV-infected cells, viral gene expression, DNA replication, and encapsidation occur in large nuclear structures designated viral replication compartments. To examine ROCK1 localization relative to the replication compartment, we stained HCMV-infected cells for ROCK1 together with metabolic labeling of nascent viral DNA using 5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine (EdU), which was visualized using “click” chemistry, or with costaining for UL57, which is found throughout the viral replication compartment. These costainings demonstrated that ROCK1 localized to defined regions that are adjacent to the viral replication compartment (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG 3.

Nuclear ROCK1 colocalizes with Hsc70 at nucleolus. (A and B) Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin strain and stained at 72 hpi for ROCK1 (red) and DAPI (blue). Replication compartments were imaged either by metabolically labeling nascent DNA with ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) followed by click-mediated fluorescent labeling of EdU (green) (A) or by staining for UL57 (green) (B). (C) Fibroblasts were mock infected and stained for Hsc70 (green) and DAPI (blue) or infected with the Merlin strain and stained at 72 hpi for ROCK1 (red), Hsc70 (green), pp28 (violet), and DAPI (blue). (D) Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin strain and stained at 72 hpi for ROCK1 (red), Hsc70 (green), the nucleolar marker fibrillarin (violet), and DAPI (blue). Scale bars are 10 μm.

In herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1)-infected cells, it was demonstrated that cellular chaperone proteins such as Hsc70 are translocated to the nucleus and organize into virus-induced chaperone-enriched (VICE) domains (13–17), which are formed adjacent to the nuclear viral replication compartment and are resistant to detergent extraction (15). We therefore examined whether in Merlin-infected cells ROCK1 colocalized with Hsc70, a marker that was used to label VICE domains in HSV-1-infected cells (13, 14). In Merlin-infected cells, a portion of the Hsc70 protein was translocated to specific nuclear puncta, which colocalized with ROCK1 (Fig. 3C). Unlike the pattern of VICE domains in HSV-1 infection, in which Hsc70 is seen in numerous punctate foci adjacent to replication compartments (15), the staining pattern of Hsc70 and ROCK1 in HCMV infected cells appeared more globular and was reminiscent of a nucleolar pattern. Staining for a nucleolar marker, fibrillarin, showed that indeed both Hsc70 and ROCK1 localize to the nucleolus in HCMV-infected cells (Fig. 3D).

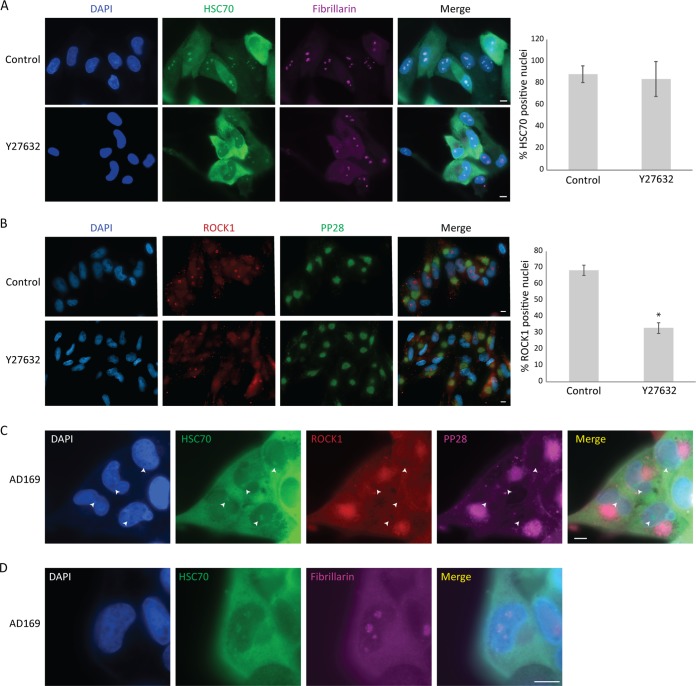

Hsc70 is known to be recruited to the nucleolus under nucleolar stress, and this recruitment was shown to be regulated by different signaling pathways (18, 19). To examine whether signaling downstream of ROCK is required for the recruitment of Hsc70 to the nucleolus during HCMV infection, we tested whether ROCK inhibition disrupts the nucleolar localization of Hsc70. Inhibition of ROCK did not affect Hsc70 localization to the nucleolus (Fig. 4A), although we verified the effect of inhibition on ROCK signaling by showing it abolished MLC phosphorylation (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The absence of changes in Hsc70 suggests that signaling downstream of ROCK is probably not required for the recruitment of Hsc70 to the nucleolus during HCMV infection. In contrast, we noticed that inhibition of ROCK activity resulted in less recruitment of ROCK1 itself into the nucleus (Fig. 4B), suggesting that ROCK1 translocation to the nucleus is dependent on its own activity.

FIG 4.

localization of Hsc70 to the nucleolus is independent of ROCK activity. (A and B) Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin HCMV strain and treated with ROCK inhibitor (Y27632) or DMSO (as a control) at 5 hpi and stained at 72 hpi for (A) Hsc70 (green), the nucleolar marker fibrillarin (violet), and DAPI (blue) or for (B) ROCK1 (red), the viral marker pp28 (green), and DAPI (blue). Representative fluorescence microscopy images are shown. Scale bars are 10 μm. The quantification of the percentage of cells containing Hsc70 (A) or ROCK1 (B) puncta in the nucleus is presented (n = 400). Means and error bars (showing standard deviations) represent triplicates. (C and D) Fibroblasts infected with the AD169 HCMV strain were stained at 72 hpi (C) for Hsc70 (green), ROCK1 (red), pp28 (violet), and DAPI (blue). The locations of Hsc70 nuclear foci are highlighted by arrowheads. In panel D, cells were stained for Hsc70 (green), fibrillarin (violet), and DAPI (blue). Representative fluorescence microscopy images are shown. Scale bars are 10 μm.

We next examined the localization of Hsc70 following infection with the AD169 HCMV strain, in which there is no translocation of ROCK1 to the nucleus. We found that Hsc70 is localized to nuclear foci also in AD169 infection (Fig. 4C; see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Also in the case of AD169 infection, Hsc70 nuclear foci colocalized with the nucleolar marker (Fig. 4D).

ROCK inhibition likely enhances viral nuclear egress.

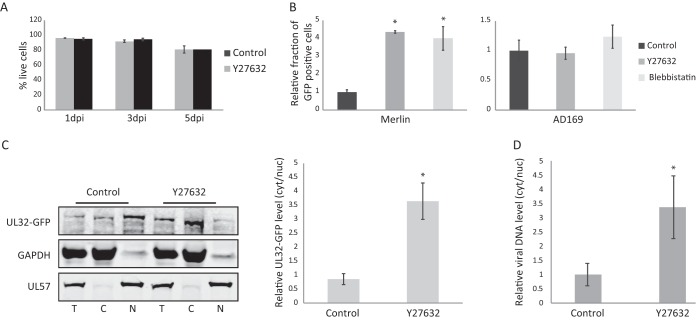

We next wanted to elucidate how ROCK inhibition enhances HCMV propagation. It was previously demonstrated that ROCK inhibition reduces cellular apoptosis (20). Therefore, a simple explanation for the enhanced viral production when ROCK is inhibited could stem from improved cell survival. However, using propidium iodide (PI) staining, we determined that there are no major changes in cell viability during HCMV infection following ROCK inhibition (Fig. 5A). Additionally there were no differences in cell numbers as a result of ROCK inhibition during infection (data not shown).

FIG 5.

ROCK activity blocks viral egress out of the nucleus. (A) Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin HCMV strain and treated with ROCK inhibitor (Y27632) or DMSO (as a control) 5 hpi. The cells were harvested at the indicated time points, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by FACS. Means and error bars (showing standard deviations) represent triplicates. (B) Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin UL32-GFP or AD169-GFP HCMV strain, and ROCK inhibitor (Y27632), myosin inhibitor (blebbistatin), or DMSO as a control was added 5 hpi. Supernatants were collected at 5 dpi and used to infect fresh fibroblasts. Viral titers were quantified by measuring the percentage of GFP-positive cells using FACS. Means and error bars (showing standard deviations) represent triplicates. (C) Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin UL32-GFP HCMV strain and at 3 dpi were fractionated to separate the cytosolic and nuclear fractions. Proteins from the total (T), cytosolic (C), and nuclear (N) fractions were analyzed by Western blotting for UL32-GFP, GAPDH (cytosolic marker), and UL57 (nuclear marker). Quantification of the ratios of nuclear and cytosolic GFP is shown. Means and error bars (showing standard deviations) represent three independent experiments. (D) Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin HCMV strain and 3 dpi were fractionated to separate the cytosolic and the nuclear fractions. DNA was isolated and analyzed by real-time PCR using primers for viral DNA. Results were normalized to cellular DNA. Quantification of the ratios of nuclear and cytosolic viral genome levels is presented. Means and error bars (showing standard deviations) represent 6 replicates. *, P < 0.05 by two-sided Student’s t test.

The colocalization of ROCK1 with Hsc70 to the nucleolus suggested ROCK activity might be related to regulation of nucleolar stress, which can then affect viral propagation. To test this possibility, we used transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) to measure whether ROCK inhibition affects cellular gene expression. These measurements revealed only minimal changes in cellular gene expression in response to ROCK inhibition in HCMV-infected cells, and there was no significant enrichment for genes associated with cellular stress (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

ROCK activity enhances intracellular contractive forces via the actomyosin network (21). To test if the antiviral activity of ROCK might be related to actomyosin-mediated contractility, we tested the effects of the myosin inhibitor blebbistatin on HCMV propagation. Notably, similarly to ROCK inhibition, inhibition of myosin activity resulted in enhancement of Merlin but not AD169 propagation (Fig. 5B). Although these results do not provide direct evidence, the similarity between ROCK and myosin inhibition suggests that the antiviral activity of ROCK may be related to activation of the actomyosin network.

The observation that ROCK inhibition reduced its nuclear localization (Fig. 4B) suggests ROCK antiviral activity is likely nuclear. Furthermore, our results indicated that ROCK activity inhibits late stages of HCMV replication and may be related to activation of the actomyosin network. We therefore sought to determine whether ROCK inhibition affects the nuclear egress of HCMV, which was recently shown to depend on nuclear actin filaments (22). The efficiency of HCMV egress was tested by examining the nuclear versus cytoplasmic abundance of UL32, a tegument protein that associates with HCMV capsids in the nucleus prior to nuclear egress (23, 24). Immunoblotting analysis demonstrated that when ROCK was inhibited, UL32 was more abundant in the cytoplasmic fraction compared to the nuclear fraction (Fig. 5C). Moreover, ROCK inhibition also increased the relative abundance of viral genomes in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 5D), further supporting the possibility that inhibition of ROCK might lead to more efficient exit of HCMV capsids out of the nucleus. Overall, our results demonstrate that during infection with HCMV using a wild-type strain, such as Merlin, the ROCK kinase restricts HCMV propagation. We propose a mechanism by which ROCK translocates to the nucleus, where it may affect the efficient egress of HCMV capsids out of the nucleus—maybe through activation of the actomyosin network.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we first reveal that ROCK activity restricts HCMV Merlin strain propagation as inhibition of ROCK resulted in a 10-fold increase in viral titers. We further show that during infection with the Merlin strain, ROCK1 translocates to the nucleus, where it colocalizes with Hsc70 in the nucleolus. The main function of the nucleolus is controlling the efficient production of ribosomes, a process that must be highly regulated (25). However, other functions have been ascribed to the nucleolus, including the coordination of stress responses (26). The localization of ROCK1 with Hsc70 to the nucleolus might indicate ROCK1 is involved in the regulation of nucleolar stress. However, our experiments suggest ROCK antiviral activity might be independent of infection-induced nucleolar stress. First, blocking ROCK activity did not lead to major changes in the recruitment of Hsc70 to the nucleolus. Second, ROCK inhibition did not lead to major changes in the expression of stress-related genes. Our experiments do reveal, however, that inhibition of ROCK partially blocks its own recruitment to the nucleus. This result, together with the observations that during infection with HCMV AD169 strain ROCK1 is not recruited to the nucleus and does not affect viral titers, indicates that ROCK antiviral activity is likely related to its nuclear localization.

ROCKs act as kinases that phosphorylate various substrates (3), and one of ROCK’s central roles is to regulate actomyosin contractility. We show that treatment of HCMV-infected cells, following viral entry, with the myosin inhibitor blebbistatin increases viral titers to a similar extent as ROCK inhibition. Also in the case of myosin inhibition, increased viral titers are observed only when cells are infected with the Merlin strain but not with the AD169 strain. These results point to the possibility that ROCK antiviral activity is related to its well-established role in regulating the actomyosin network.

Actomyosin-mediated contractility is a highly conserved mechanism that generates mechanical force in animal cells and is involved in many cellular processes, such as changes in shape, intracellular transport, and cell mechano-sensing (27). Since our results suggest that the antiviral activity of ROCK might be nuclear and occurs at a late time point of infection, we examined ROCK’s effect on HCMV egress. Previously it was shown that UL32 can be used to track viral processes, including nuclear egress (23). We show that ROCK inhibition leads to elevation in the levels of cytoplasmic UL32 relative to nuclear UL32. In addition, ROCK inhibition resulted in more viral DNA in the cytosol compared to the nucleus. Although at present we can only speculate about the mechanism, these results indicate that nuclear egress might be partially hindered by ROCK activity. Interestingly, in HSV-infected cells, a nucleolus-localized viral protein, UL24, was shown to promote HSV-1 nuclear egress—possibly through effects on the nucleolus (28). It therefore remains possible that ROCK1 localization to the nucleolus is somehow related to the reduced egress we measured.

The involvement of the nuclear actomyosin network in intranuclear movements of herpesvirus capsids was previously studied and remains controversial (29). HSV-1 capsids’ motility in the nucleus was shown to be antagonized by temperature reduction or by inhibitors of ATP, myosin, or actin (30). It was further shown that HSV-1 and pseudorabies virus (PRV) infections result in the formation of nuclear actin filaments (31). In contrast, more recent analysis reported that HSV-1 and PRV infections remodel nuclear architecture so that capsids can diffuse to the nuclear periphery (32). For HCMV, it was demonstrated that nuclear actin filaments are induced during infection and that these actin filaments are important for HCMV nuclear egress (22). Furthermore, HCMV capsids were shown to associate with nuclear myosin V, which was required for capsid accumulation in the cytoplasm (33). Our results add another level of complexity, as we show that inhibition of ROCK and direct inhibition of myosin II with blebbistatin increase viral titers, but this effect was strain dependent. These results may suggest that nuclear actomyosin activity can also suppress HCMV propagation, at least in certain strains. However, we cannot preclude that this is an indirect effect occurring via other cellular processes, such as the mechano-state of the nucleus. Recent evidence shows that the local mechano-environment can regulate transcription (34). There is also evidence for roles of nuclear actin and myosin in transcription, chromatin remodeling, and mRNA export (35, 36). Of note, we see upregulation in late viral protein expression, which could not be explained by differences in the capsids’ egress. In addition, the elevation in viral transcripts seemed milder than the changes we saw in viral protein expression. Although speculative, these differences might point to changes in mRNA export. It is therefore possible that ROCK inhibition relieves potential stress or constraints that affect viral egress out of the nucleus or that ROCK inhibition affects viral egress indirectly through the increase in viral protein levels.

Another interesting aspect of our findings is the differences we reveal between the HCMV laboratory-adapted strain AD169, in which 15 kb composing the ULb′ region (genes encoding UL133 to UL150) is deleted and the Merlin strain, which is considered a wild-type (WT) strain with characterized mutation in only two viral proteins (9). It is well acknowledged that the ULb′ region is lost upon serial passage of the virus in fibroblasts (37), indicating it contains elements that repress propagation in fibroblasts. It is possible that the host cell drives ROCK’s movement to the nucleus (maybe due to stress signals induced by the virus). Since in AD169-infected cells ROCK1 is not recruited to the nucleus and ROCK does not have any antiviral activity, it is likely the virus can prevent this inhibition. Which viral elements facilitate or prevent ROCK1 recruitment to the nucleus is an open question, but since these elements are preserved, it is probable that they have both beneficial and inhibitory functions, depending on the cellular context.

In summary, we demonstrate that ROCK activity inhibits HCMV propagation at late stages of infection. Our results suggest that this activity may be related to nuclear activation of the actomyosin network. Our findings and future studies aimed at resolving ROCK’s antiviral function and the potential role of the nuclear actomyosin network for HCMV propagation may be important not just for HCMV biology but also for general understanding of the potential functions of actomyosin in the nucleus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and treatments.

Human foreskin fibroblasts (CRL-1634), RPE1 (CRL-4000), and the HCMV Merlin strain (VR-1590) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The Merlin UL32-GFP strain was kindly provided by R. Stanton (9). The AD169 virus was previously described (38–40). The AD169-GFP strain was kindly provided by M. Messerle (41). Cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5, unless stated otherwise, by incubation with the virus for 1 h followed by replacement of the medium.

To achieve ROCK inhibition, cells were treated with 10 μM Y27632 (sigma) or 2 μM H1152 (Santa Cruz) at the indicated times. Myosin was inhibited by treating cells with 2 μM blebbistatin. For proteasome inhibition, cells were treated with 10 μM MG132 for 8 h and proteins were extracted and analyzed by Western blotting.

To test cell viability, cells were trypsinized, centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min and resuspended in 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Propidium iodide (PI [0.5 μg/ml]) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 1 min and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS). Mock-infected cells either untreated or treated by a heat shock of 10 min at 65°C served as negative and positive controls, respectively.

TCID50 assay.

A total of 104 fibroblasts were plated in 96-well plates, and cells were infected with 10-fold serial dilutions of supernatant from infected cells, collected 5 dpi. At 12 dpi, the dilutions showing cytopathic effect were evaluated by light microscopy. The 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50)/ml was calculated using the Spearman-Kärber method (42).

Knockdown by siRNA.

Cells were transfected with siRNA validated for ROCK1 and ROCK2 (On-Target Plus siRNA; Dharmacon) or negative control (IDT) in the presence of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Infection was performed 24 h after transfection.

Viral titer measurements using flow cytometry.

Fibroblasts were infected with the Merlin UL32-GFP strain or AD169-GFP. Five days postinfection, the supernatant was collected and used to infect fresh fibroblasts. At 72 hpi, cells were imaged in the microscope and then harvested for analysis by flow cytometry. The percentage of GFP-positive cells was normalized to the relevant control.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were lysed using “harsh” buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS) or “mild” buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, 0.2% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS). Lysates were rotated at 4°C for 10 min and then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Samples were then separated by 4 to 12% polyacrylamide Bis-Tris gel electrophoresis (Invitrogen), blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-ROCK1 (abcam), rabbit anti-GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-UL44 (Virusys Corporation), mouse anti-PP28 (EastCoast Bio), rabbit anti-histone H2B (abcam), and rabbit anti-phospho-MLC2 (Cell Signaling Technology). The secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit–IRDye 800CW, goat anti-rabbit–IRDye 680RD, goat anti-mouse–IRDye 800CW, goat anti-mouse–IRDye 680RD (LI-COR), and goat anti-rat–Alexa Fluor 680 (abcam). Reactive bands were detected by the Odyssey CLx infrared imaging system (LI-COR). The protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay (Sigma). Protein quantification was performed using LI-COR software.

Cellular fractionation.

For protein analysis, cells were fractionated using an NE-PER kit (Thermo Fisher). Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were separated on SDS gel and analyzed by Western blotting. For DNA analysis, cells were fractionated as described previously (43) into nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, DNA was extracted according to the protocol and used for real-time PCR. Cellular DNA was used for normalization.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were plated on ibidi slides, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed in PBS (pH 7.4), permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, and then blocked with either 10% goat serum or 10% human serum in PBS for 30 min. Immunostaining was performed for the detection of rabbit anti-ROCK1 (abcam), rat anti-Hsc70 (Enzo), mouse anti-fibrillarin (abcam), mouse anti-PP28 (EastCoast Bio), and mouse anti-UL57 (Virusys Corporation). Cells were washed 3 times with PBS and labeled with the appropriate secondary antibody and with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) for 1 h at room temperature. The following secondary antibodies were used: donkey anti-rabbit–Rhodamine Red-X, donkey anti-rabbit–Cy2, donkey anti-rat–Rhodamine Red-X, donkey anti-rat–Alexa Fluor 488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch), goat anti-mouse–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Sigma-Aldrich), and goat anti-mouse–Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo Fisher). Detergent extraction was performed as previously described (15). Imaging was performed on an AxioObserver Z1 wide-field microscope using a 40× or 63× oil objective and Axiocam 506 mono camera.

EdU staining.

EdU staining was performed based on the method in reference 44. Briefly, cells were incubated with 10 μM 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) (Jena Bioscience GmbH) for 30 min. Cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 min, and stained with staining mix (100 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 1 mM CuSO4, 10 μM fluorescent azide, 100 mM ascorbic acid) for 30 min. EdU-stained cells were immunostained for ROCK1 and DAPI as described above.

Real-time PCR.

Total DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA blood minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA was extracted using TRI Reagent (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was prepared using the qScript cDNA synthesis kit (Quanta Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR green PCR master mix (ABI) on a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Life Technologies) with the following primers: UL55, forward, TGGGCGAGGACAACGAA, and reverse, TGAGGCTGGGAAGCTGACAT; B2M, forward, TGCTGTCTCCATGTTTGATGTATCT, and reverse, TCTCTGCTCCCCACCTCTAAGT; UL44, forward, AGCAAGGACCTGACCAAGTT, and reverse, GCCGAGCTGAACTCCATATT; UL99, forward, GGGAGGATGACGATAACGAG, and reverse, TGCCGCTACTACTGTCGTTT; UL123, forward, GCGCCAGTGAATTTCTCTTC, and reverse, GTCCTGGCAGAACTCGTCA; and Anxa5, forward, AGTCTGGTCCTGCTTCACCT, and reverse, CAAGCCTTTCATAGCCTTCC.

RNA-seq and data analysis.

RNA isolation and poly(A) selection were done using the Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT purification kit (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. mRNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the SENSE total RNA-seq library prep kit (Lexogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Raw sequences obtained from NextSeq500 (Illumina) were trimmed according to the library prep kit instructions. Alignment was performed using Bowtie (allowing up to 2 mismatches), and reads were aligned to the human genome (hg19).

Reads aligned to rRNA were removed. Reads that were not aligned to the genome were then aligned to the transcriptome. Differential expression analysis was done with DESeq2 (version 1.22.2) (45) with default parameters. The number of reads in each of the samples was used as the input.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stern-Ginossar lab members for critical readings of the manuscript.

This research was supported by the European Research Council Starting Grant (StG-2014-638142), an EU-FP7-PEOPLE Career Integration Grant, and the Israeli Science Foundation (1073/14). N.S.G. is an incumbent of the Skirball Career Development Chair in New Scientists.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00453-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Britt W. 2008. Manifestations of human cytomegalovirus infection: proposed mechanisms of acute and chronic disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 325:417–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tirosh O, Cohen Y, Shitrit A, Shani O, Le-Trilling VTK, Trilling M, Friedlander G, Tanenbaum M, Stern-Ginossar N. 2015. The transcription and translation landscapes during human cytomegalovirus infection reveal novel host-pathogen interactions. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005288. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riento K, Ridley AJ. 2003. ROCKs: multifunctional kinases in cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4:446–456. doi: 10.1038/nrm1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amano M, Ito M, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Chihara K, Nakano T, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. 1996. Phosphorylation and activation of myosin by Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase). J Biol Chem 271:20246–20249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schofield AV, Bernard O. 2013. Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK) signaling and disease. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 48:301–316. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.786671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maekawa M, Ishizaki T, Boku S, Watanabe N, Fujita A, Iwamatsu A, Obinata T, Ohashi K, Mizuno K, Narumiya S. 1999. Signaling from Rho to the actin cytoskeleton through protein kinases ROCK and LIM-kinase. Science 285:895–898. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishizaki T, Uehata M, Tamechika I, Keel J, Nonomura K, Maekawa M, Narumiya S. 2000. Pharmacological properties of Y-27632, a specific inhibitor of Rho-associated kinases. Mol Pharmacol 57:976–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharon-Friling R, Shenk T. 2014. Human cytomegalovirus pUL37x1-induced calcium flux activates PKC, inducing altered cell shape and accumulation of cytoplasmic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E1140–E1148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402515111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanton RJ, Baluchova K, Dargan DJ, Cunningham C, Sheehy O, Seirafian S, McSharry BP, Neale ML, Davies JA, Tomasec P, Davison AJ, Wilkinson G. 2010. Reconstruction of the complete human cytomegalovirus genome in a BAC reveals RL13 to be a potent inhibitor of replication. J Clin Invest 120:3191–3208. doi: 10.1172/JCI42955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki Y, Suzuki M, Hidaka H. 2002. The novel and specific Rho-kinase inhibitor (S)-(+)-2-methyl-1-[(4-methyl-5-isoquinoline)sulfonyl]-homopiperazine as a probing molecule for Rho-kinase-involved pathway. Pharmacol Ther 93:225–232. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(02)00191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryckman BJ, Rainish BL, Chase MC, Borton JA, Nelson JA, Jarvis MA, Johnson DC. 2008. Characterization of the human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/UL128-131 complex that mediates entry into epithelial and endothelial cells. J Virol 82:60–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01910-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murrell I, Tomasec P, Wilkie GS, Dargan DJ, Davison AJ, Stanton RJ. 2013. Impact of sequence variation in the UL128 locus on production of human cytomegalovirus in fibroblast and epithelial cells. J Virol 87:10489–10500. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01546-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burch AD, Weller SK. 2004. Nuclear sequestration of cellular chaperone and proteasomal machinery during herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J Virol 78:7175–7185. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.7175-7185.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burch AD, Weller SK. 2005. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA polymerase requires the mammalian chaperone hsp90 for proper localization to the nucleus. J Virol 79:10740–10749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10740-10749.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livingston CM, Ifrim MF, Cowan AE, Weller SK. 2009. Virus-induced chaperone-enriched (VICE) domains function as nuclear protein quality control centers during HSV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000619. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livingston CM, DeLuca NA, Wilkinson DE, Weller SK. 2008. Oligomerization of ICP4 and rearrangement of heat shock proteins may be important for herpes simplex virus type 1 prereplicative site formation. J Virol 82:6324–6336. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00455-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Johnson LA, Dai-Ju JQ, Sandri-Goldin RM. 2008. Hsc70 focus formation at the periphery of HSV-1 transcription sites requires ICP27. PLoS One 3:e1491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bański P, Mahboubi H, Kodiha M, Shrivastava S, Kanagaratham C, Stochaj U. 2010. Nucleolar targeting of the chaperone hsc70 is regulated by stress, cell signaling, and a composite targeting signal which is controlled by autoinhibition. J Biol Chem 285:21858–21867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.117291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelham HR. 1984. Hsp70 accelerates the recovery of nucleolar morphology after heat shock. EMBO J 3:3095–3100. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02264.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe K, Ueno M, Kamiya D, Nishiyama A, Matsumura M, Wataya T, Takahashi JB, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa S, Muguruma K, Sasai Y. 2007. A ROCK inhibitor permits survival of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 25:681–686. doi: 10.1038/nbt1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charras G, Paluch E. 2008. Blebs lead the way: how to migrate without lamellipodia. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9:730–736. doi: 10.1038/nrm2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkie AR, Lawler JL, Coen DM. 2016. A role for nuclear F-actin induction in human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress. mBio 7:e01254-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01254-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sampaio KL, Cavignac Y, Stierhof Y-D, Sinzger C. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus labeled with green fluorescent protein for live analysis of intracellular particle movements. J Virol 79:2754–2767. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2754-2767.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varnum SM, Streblow DN, Monroe ME, Smith P, Auberry KJ, Pasa-Tolic L, Wang D, Camp DG, Rodland K, Wiley S, Britt W, Shenk T, Smith RD, Nelson JA, Nelson JA. 2004. Identification of proteins in human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) particles: the HCMV proteome. J Virol 78:10960–10966. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10960-10966.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lempiäinen H, Shore D. 2009. Growth control and ribosome biogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 21:855–863. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boulon S, Westman BJ, Hutten S, Boisvert F-M, Lamond AI. 2010. The nucleolus under stress. Mol Cell 40:216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murrell M, Oakes PW, Lenz M, Gardel ML. 2015. Forcing cells into shape: the mechanics of actomyosin contractility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16:486–498. doi: 10.1038/nrm4012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lymberopoulos MH, Bourget A, Ben Abdeljelil N, Pearson A. 2011. Involvement of the UL24 protein in herpes simplex virus 1-induced dispersal of B23 and in nuclear egress. Virology 412:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosse JB, Enquist LW. 2016. The diffusive way out: herpesviruses remodel the host nucleus, enabling capsids to access the inner nuclear membrane. Nucleus 7:13–19. doi: 10.1080/19491034.2016.1149665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forest T, Barnard S, Baines JD. 2005. Active intranuclear movement of herpesvirus capsids. Nat Cell Biol 7:429–431. doi: 10.1038/ncb1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feierbach B, Piccinotti S, Bisher M, Denk W, Enquist LW. 2006. Alpha-herpesvirus infection induces the formation of nuclear actin filaments. PLoS Pathog 2:e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bosse JB, Hogue IB, Feric M, Thiberge SY, Sodeik B, Brangwynne CP, Enquist LW. 2015. Remodeling nuclear architecture allows efficient transport of herpesvirus capsids by diffusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E5725–E5733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513876112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkie AR, Sharma M, Pesola JM, Ericsson M, Fernandez R, Coen DM. 2018. A role for myosin Va in human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress. J Virol 92:e01849-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01849-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon DN, Wilson KL. 2011. The nucleoskeleton as a genome-associated dynamic “network of networks.” Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12:695–708. doi: 10.1038/nrm3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Lanerolle P, Johnson T, Hofmann WA. 2005. Actin and myosin I in the nucleus: what next? Nat Struct Mol Biol 12:742–746. doi: 10.1038/nsmb983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Visa N, Percipalle P. 2010. Nuclear functions of actin. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000620. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cha TA, Tom E, Kemble GW, Duke GM, Mocarski ES, Spaete RR. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus clinical isolates carry at least 19 genes not found in laboratory strains. J Virol 70:78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le VTK, Trilling M, Hengel H. 2011. The cytomegaloviral protein pUL138 acts as potentiator of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1 surface density to enhance ULb′-encoded modulation of TNF-α signaling. J Virol 85:13260–13270. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06005-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seidel E, Le VTK, Bar-On Y, Tsukerman P, Enk J, Yamin R, Stein N, Schmiedel D, Oiknine Djian E, Weisblum Y, Tirosh B, Stastny P, Wolf DG, Hengel H, Mandelboim O. 2015. Dynamic co-evolution of host and pathogen: HCMV downregulates the prevalent allele MICA*008 to escape elimination by NK cells. Cell Rep 10:968–982. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rölle A, Pollmann J, Ewen E-M, Le VTK, Halenius A, Hengel H, Cerwenka A. 2014. IL-12-producing monocytes and HLA-E control HCMV-driven NKG2C+ NK cell expansion. J Clin Invest 124:5305–5316. doi: 10.1172/JCI77440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borst E-M, Messerle M. 2005. Analysis of human cytomegalovirus oriLyt sequence requirements in the context of the viral genome. J Virol 79:3615–3626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3615-3626.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darling AJ, Boose JA, Spaltro J. 1998. Virus assay methods: accuracy and validation. Biologicals 26:105–110. doi: 10.1006/biol.1998.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galvis AE, Fisher H, Camerini D. 2017. NP-40 fractionation and nucleic acid extraction in mammalian cells. Bio-protocol 7:e2584. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jao CY, Salic A. 2008. Exploring RNA transcription and turnover in vivo by using click chemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:15779–15784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808480105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.