Abstract

Lassa fever is a frequently severe human disease that is endemic to several countries in West Africa. To date, no licensed vaccines are available to prevent Lassa virus (LASV) infection, even though Lassa fever is thought to be an important disease contributing to mortality and both acute and chronic morbidity. We have previously described a vaccine candidate composed of single-cycle LASV replicon particles (VRPs) and a stable cell line for their production. Here, we refine the genetic composition of the VRPs and demonstrate the ability to reproducibly purify them with high yields. Studies in the guinea pig model confirm efficacy of the vaccine candidate, demonstrate that single-cycle replication is necessary for complete protection by the VRP vaccine, and show that postexposure vaccination can confer protection from lethal outcome.

Keywords: Lassa, postexposure, single-cycle replication, vaccine, virus replicon particle

Lassa fever (LF) is an infectious disease with several public health facets. Although the overall case fatality rate of LF is low [1], the sheer number of cases [2] makes the disease a significant burden in the affected areas of West Africa. In addition, high case fatality rates have been noted among hospitalized patients [3–6], and LF has been exported from endemic areas to other parts of the world more than 2 dozen times [7]. Human-to-human transmission occurs, and it has now been reported outside endemic areas after one such exportation [8]. In addition to being an often-severe acute infection, LF is also associated with sudden-onset hearing impairment that becomes permanent in a large proportion of cases [9]; therefore, it may affect patients far beyond the resolution of acute symptoms [10].

Recently, significant efforts have focused on research and development in the field of neglected viral diseases, including LF [11, 12]. Although no vaccine candidate against Lassa virus (LASV) has been clinically evaluated so far, several different approaches have been studied in animal models (for latest reviews, see [13–15]). In a recent study, we used reverse genetics to build a vaccine candidate composed of LASV replicon particles (VRPs) that only replicate in the first cells they encounter [16]. The genome of LASV (current taxonomy: Arenaviridae/Mammarenavirus) consists of 2 ambisense, single-strand ribonucleic acid (RNA) segments encoding 4 virus-essential genes. The VRPs lack the viral glycoprotein gene; thus, they are unable to spread except in a cell line that stably expresses the glycoprotein gene products. In this study, we (1) generate a VRP vaccine that does not include any exogenous gene, (2) determine the efficiency of a commercially available and scalable purification technology for VRP production, (3) establish the necessity of VRP replication for complete protection, and (4) assess postexposure vaccination to simulate potential therapeutic use in an outbreak setting.

METHODS

Biosafety

Work with recombinant LASV strain Josiah [17], VRPs, and guinea pigs was conducted under biosafety level 4 containment at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ([CDC] Atlanta, GA).

Lassa Virus Replicon Particle Rescue and Cell Lines

Vero-LASV-GPCco cells and VRP rescue were described earlier [16]. In this study, the fluorescent reporter gene was deleted from the S segment rescue plasmid, leaving 9 bases between the untranslated region and the intergenic region. These bases do not code for a start codon, but they do encode 2 stop codons. BSR T7/5 cells ([18] kind gift from Karl-Klaus Conzelmann) were transfected with (1) rescue constructs encoding LASV L segment and S segment devoid of the glycoprotein gene as well as with (2) a helper construct to express LASV glycoprotein precursor. Four days after transfection, supernatants were passed onto stable Vero-LASV-GPCco cells. The VRPs used for vaccination were passaged 3 times on this producer cell line. Other cell lines included in the experiments were human A549 (ATCC no. CLL-185) and guinea pig GPC-16 (ATCC no. CCL-242). All cell lines, viruses, and VRP stocks tested negative for mycoplasma using MycoAlert Plus reagents (Lonza).

Lassa Virus Replicon Particle Purification

Vero-LASV-GPCco cells were inoculated with VRPs at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01. At 5–6 days postinfection (p.i.), the supernatants were clarified by slow-speed centrifugation and purified using LentiSelect ion exchange columns (Sartorius). After elution with high-salt solution of the ion exchange system, the buffer was changed to Hank’s balanced salt solution ([HBSS] Gibco) using 100-kDa VivaSpin columns (Sartorius) so that the high-salt elution buffer was diluted 100-fold. The VRPs in HBSS were sterile-filtered using 0.22-µm low protein-binding PES filters (Millipore), aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

Electron Microscopy

The LASV-inoculated Vero-E6 cells and VRP-inoculated Vero-LASV-GPCco cells, as well as uninfected control cells, were harvested 5 days after inoculation and inactivated by fixation with phosphate-buffered 2.5% glutaraldehyde followed by γ-irradiation (5 × 106 rad from a 60Co source). Specimens were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, stained en bloc with uranyl acetate, dehydrated in a graded series of alcohols and acetone, and embedded in an Epon substitute/Araldite mixture. Sections were stained with uranyl acetate and Reynolds lead citrate and examined using a Thermo Fisher/FEI Spirit electron microscope.

Antibodies

IRF-3 (D614C) XP antibody (catalog no. 11904S; Cell Signaling Technology) and mouse monoclonal mix (in-house reagent no. SPR628) were used for immunofluorescence analysis. In-house hyperimmune mouse ascitic fluid (no. 703079) detecting LASV nucleoprotein (NP), mouse monoclonal antibody 52–74-7 detecting LASV GP1 [19], PKR (C-term) antibody (Y117; Epitomics), anti-PKR (phospho T446) antibody (E120; Abcam), ZsGreen (ZSG) monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 632598; Takara), and mouse anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody B-5–1-2 (Sigma-Aldrich) were used for Western blotting. Expression of antigens in the guinea pig antibody assay was verified using mouse monoclonal antibodies 52–129-18 detecting LASV NP and 52–74-7 detecting LASV GP1 [19], as well as a rabbit anti-LASV Z polyclonal antibody (catalog no. 0307–002; IBT Bioservices).

In Vivo Experiments

All animal procedures were approved by the CDC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The CDC is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Groups of 5 male and female strain 13/N guinea pigs (9 months to 2 years of age) from the CDC breeding colony, distributed proportionally according to sex and baseline weight, were chosen after power analysis so that complete protection would provide a statistically significant difference from the 80% to 100% mortality that is expected after challenge with LASV Josiah strain. Animals were vaccinated subcutaneously (SC) using 1 × 107 focus-forming units (FFU) of purified VRPs (live or inactivated by 5 × 106 rads of γ-irradiation) in HBSS or with HBSS vehicle control; a challenge dose of 1 × 104 FFU recombinant LASV-Josiah [17] was administered 28 days later. Alternatively, animals in the postexposure (VRP-PE) group were given 1 × 107 FFU of live VRPs 1 day after the same challenge. Vaccine and challenge inocula were back-titered, and delivered doses were found to be within 1.6-fold of the intended dose. Animals’ body temperatures were monitored using implanted microchip transponders (IPTT-300; BMDS). Water consumption was measured using graduated bottles and calculated as percentage of water consumed overnight. Clinical signs were scored based on 14 parameters: 1 point each for quiet, dull, responsive (QDR) disposition, hunched back or ruffled coat, huddling or burrowing; 2 points each for mild or moderate weakness, dehydration (eye recession), ataxia/circling/tremors/head tilt, weight loss of >15%; 3 points each for severe weakness, abnormal breathing, or anemia; 12 points each for paralysis, frank hemorrhage or bleeding, moribund state, or weight loss of >25%. Animals were humanely euthanized when end-point criteria were reached (clinical score ≥12) or at study completion (42 days p.i.).

Quantitative Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

The RNA samples were collected using MagMax RNA isolation reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid was removed using BaseLine Zero DNase (Epicentre), and quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using SuperScript III Platinum One-Step qRT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen). The following primers and probe were used for quantifying LASV NP RNA: 5′-GTACTCACATGGGATTGATGTCAC-3′, 5′-CTTCCTTGTGATTCAAGGAGTTTC-3′, 5′−56-FAM/TTCGCTACA/ZEN/CAACCGGGCTTGACC/3IABkFQ/−3′. Guinea pig IFN-β mRNA assay consisted of these primers and probe: 5′-GTGTATCCTCCAAATCGCT CTC-3′, 5′-GAATTGCTGCTGCGTTGTT-3′, and 5′-/56-FAM/TGCTGTCCT/ZEN/TCACCACATCTCTTTCC/3IABkFQ/−3′. Guinea pig glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and RANTES transcripts were detected using commercial assays (Cp03755743_g1 and Cp03754832_m1, respectively; Thermo Fisher Scientific). For in vivo samples, a standard curve of in vitro-transcribed LASV RNA was generated. A tissue-specific correction for sample preparation efficacy was applied using GAPDH cycle threshold.

Antibody Assays

GPC-16 cells were reverse transfected with plasmids encoding LASV NP, GPC, or Z-HA, or with control plasmid encoding no antigen. After 2 days, the cells were fixed and stained using guinea pig plasma samples as the primary antibodies, inactivated using 5 × 106 rads of γ-irradiation, and diluted 1:200. Mouse and rabbit antibodies listed above were used to verify expression of each antigen. The NP signals displayed intensity differences and were graded on a scale between 1 and 3 after averaging 2 separate experiments and rounding down. The GPC signals were similar in all samples and were not graded. No antibodies against LASV Z were detected in the plasma samples.

Immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgM enzyme-linked immune-sorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed as previously described [16]. No sample in this study tested positive for LASV-specific IgM antibodies; therefore, IgM ELISA results are not shown. To screen for neutralization activity, irradiated plasma samples were heated to 56°C for 30 minutes and incubated at final dilutions 1:16 to 1:128 with Lassa VRPs for 1 hour at 37°C. Vero-E6 cells were inoculated with these mixes in triplicate for 1 hour at 37°C, inocula were removed, and fresh media were added. Observed titer reductions of >80% were considered positive.

Clinical Chemistry

Guinea pig blood samples were collected in lithium heparin vials at the time of euthanasia, and clinical chemistry analyses were performed using the MetLac12 panel on a Piccolo Xpress analyzer (Abaxis).

RESULTS

Generating Lassa Virus Replicon Particles Expressing Only Genes of Viral Origin

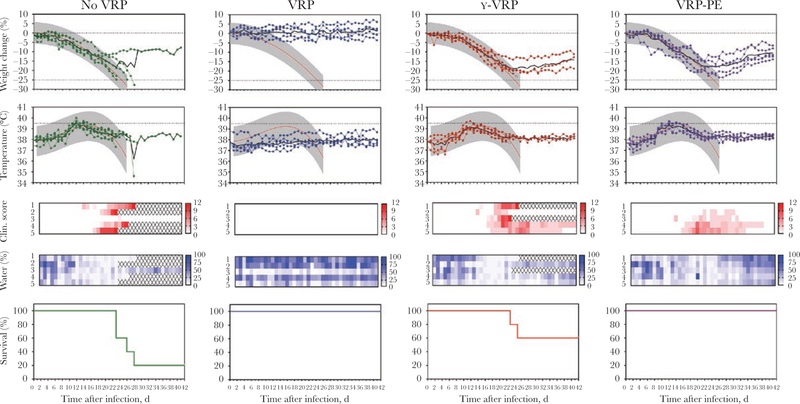

In our previous work, we generated Lassa VRPs that carry the fluorescent reporter gene ZSG in lieu of the viral glycoprotein precursor. Such VRPs, regardless of whether their NP encoded a functional exonuclease innate immunity antagonist [20–22], protected strain 13/N guinea pigs from lethal LASV challenge 28 days after vaccination [16]. After these promising proof-of-concept results, we then removed the exogenous reporter gene from the VRP genome to provide a vaccine candidate that only encodes proteins originating from LASV (Figure 1A). In the producing cell line, Vero-LASV-GPCco, VRPs without the ZSG gene replicated at similar efficiency as the VRPs with ZSG. The VRPs with inactive NP exonuclease (VRP/ZSG/ExoN) replicated at a similar efficiency as the ones with active exonuclease until 1 day p.i., but they began to show reduced fitness by day 2, reaching 4–5 times lower final titers on day 4 (Figure 1B). Removing the reporter gene from VRPs resulted in intermediate innate immune activation compared with the other previously tested VRPs (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Refining the virus replicon particle vaccine genome and purification by ion exchange chromatography. (A) Lassa virus (LASV) replicon particles (VRPs) with empty GPC locus (Lassa VRP) were compared with VRPs that express the ZsGreen (ZSG) reporter from the GPC locus (Lassa VRP/ZSG). Virus-specific immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and ZSG fluorescence are shown. (B) Lassa VRPs and VRP/ZSG exhibit equivalent growth kinetics in Vero-LASV-GPCco cells, whereas VRPs in which the exonuclease has been inactivated by mutation (VRP/ZSG/ExoN) grow to a lower final titer. Vero-LASV-GPCco cells were inoculated at a multiplicity of infection of 0.05, and output was measured in Vero-E6 cells. (C) Schematic of VRP purification workflow. Raw supernatant was clarified by low-speed centrifugation and subjected to ion exchange chromatography. High-salt elution buffer was changed to physiological buffer, Hank’s balanced salt solution, using retention based on molecular mass of 100 kDa, and the resulting product was sterile-filtered using a low protein-binding membrane. Percentages represent remaining total infectivity compared with starting infectivity at designated steps; averages and standard deviations from 3 independent experiments; average and actual values from 2 independent experiments for ion exchange. ExoN, exonuclease-null; FFU, focus-forming units; PES, polyethersulfone.

Lassa Virus Replicon Particle Purification

In addition to proving protective efficacy, moving a vaccine candidate forward in the development pipeline would require ease of purification and stability. We reasoned that because both arenaviruses and lentiviruses form lipid-enveloped, glycoprotein-studded particles, repurposing a lentivirus purification workflow might enable purification of VRPs (Figure 1C). Raw culture supernatants were clarified by slow-speed centrifugation, passed through ion exchange resin to bind VRPs, washed, and eluted using high ionic strength buffer. Molecular weight cutoff columns were then used to change the buffer to HBSS, a buffer with physiological pH and isotonic salt concentration. The final product was sterile-filtered using low protein-binding filters and stored at −80°C. Collecting samples at various stages of the purification workflow showed high reproducibility. On average, 79.8% of VRP infectivity was recovered after washes in the ion exchange column, and 44.2% infectivity remained after buffer change, sterile filtration, and 1 freeze-thaw cycle in HBSS (Figure 1C).

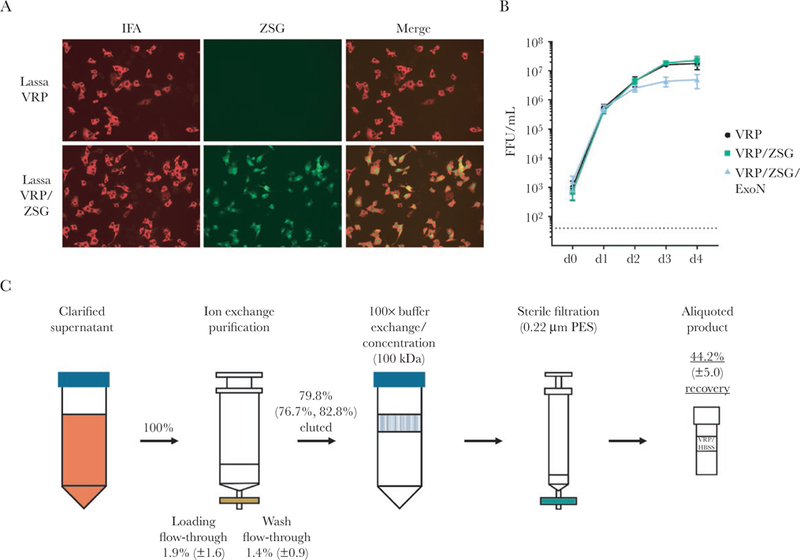

Comparing Replicon Particle and Lassa Virion Morphology

The LASV NP and glycoproteins are processed the same way in Vero-E6 cells infected with LASV and in Vero-LASV-GPCco cells in which VRPs are cultured [16]. For more detail on the composition of the VRPs themselves, electron microscopy was used to compare morphology of VRPs to morphology of LASV virions. Figure 2 shows that VRPs budding from the plasma membrane of producer Vero-LASV-GPCco cells have the classic appearance of arenavirus particles, and they closely resemble authentic LASV virions budding from Vero-E6 cells.

Figure 2.

Lassa virus (LASV) virion and LASV replicon particle (VRP) morphology. Vero-E6 cells and Vero-LASV-GPCco cells were inoculated at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01 with LASV and VRPs, respectively, or were mock-inoculated. After 5 days, the cells were processed for transmission electron microscopy. Particles of equivalent size and morphology were seen budding from both samples (arrows). No such particles were seen in mock-inoculated control samples (data not shown).

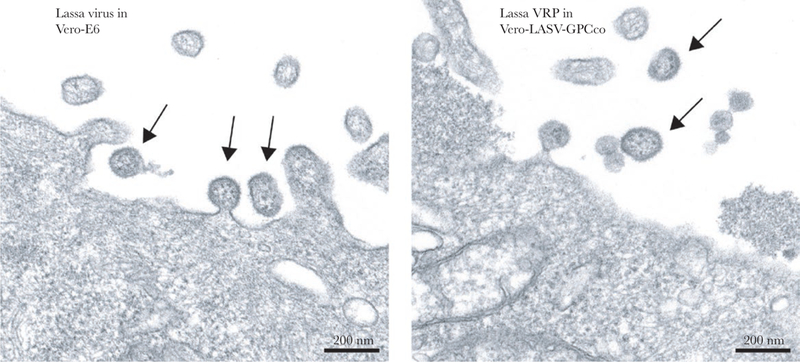

Postexposure Protection in the Guinea Pig Model and Necessity of Replication

In a previous study, VRP stocks with either functional or mutated NP exonuclease domains were found to protect guinea pigs from clinical disease and lethality when administered SC 28 days before challenge with LASV [16]. Now, we evaluated the purified VRP vaccine candidate with no exogenous genes in the standard single-shot, pre-exposure regimen (VRP group) and compared it to a vehicle control (no-VRP group) and irradiated vaccine (γ-VRP group; used to assess whether transcription and replication are critical for protection). In addition, one group of animals was vaccinated 1 day after LASV challenge (VRP-PE group) to study how quickly effective protection could be achieved.

No clinical signs were seen in any vaccinated animals before challenge (Supplementary Figure 2). After 28 days, the guinea pigs were challenged SC with 1 × 104 FFU LASV-Josiah. Weight change, temperature, clinical score, and water consumption were recorded to monitor disease development (Figure 3). All animals in the no-VRP group developed clinical disease as defined by weight loss, elevated body temperatures, and reduced water consumption; 4 of 5 animals in this group succumbed 23–28 days p.i. In contrast, VRP-vaccinated animals survived through the 42-day observation period without displaying any signs of clinical disease. The γ-VRP group had an intermediate outcome: all animals had clinical signs, and 2 of 5 succumbed to infection. It is interesting to note that all animals of the postexposure VRP-PE group lost weight, had elevated temperatures, and reduced water consumption 18–25 days p.i., but did not reach end-point criteria. By day 42, all animals in this group were recovering weight, drinking, and displaying no overt clinical signs.

Figure 3.

Postchallenge survival and clinical parameters. Strain 13/N guinea pigs were challenged subcutaneously with 1 × 104 focus-forming units Lassa virus (LASV)-Josiah 28 days postimmunization (1 day before immunization of the LASV replicon particle-postexposure [VRP-PE] group). γ-VRP refers to VRP inactivated by γ-irradiation before administration. Weight change from baseline values and body temperatures are reported; black represents averages, and colors represent individual animals. Red and gray curves show the average and 90% predictive range of lethal disease parameters as determined during our previous studies in this model. Clinical score represents overt signs of disease and was calculated as described in the Methods section. In addition, water consumption of individual animals is represented as percentage of available water consumed. Survival curves indicate percentage of animals surviving in each group.

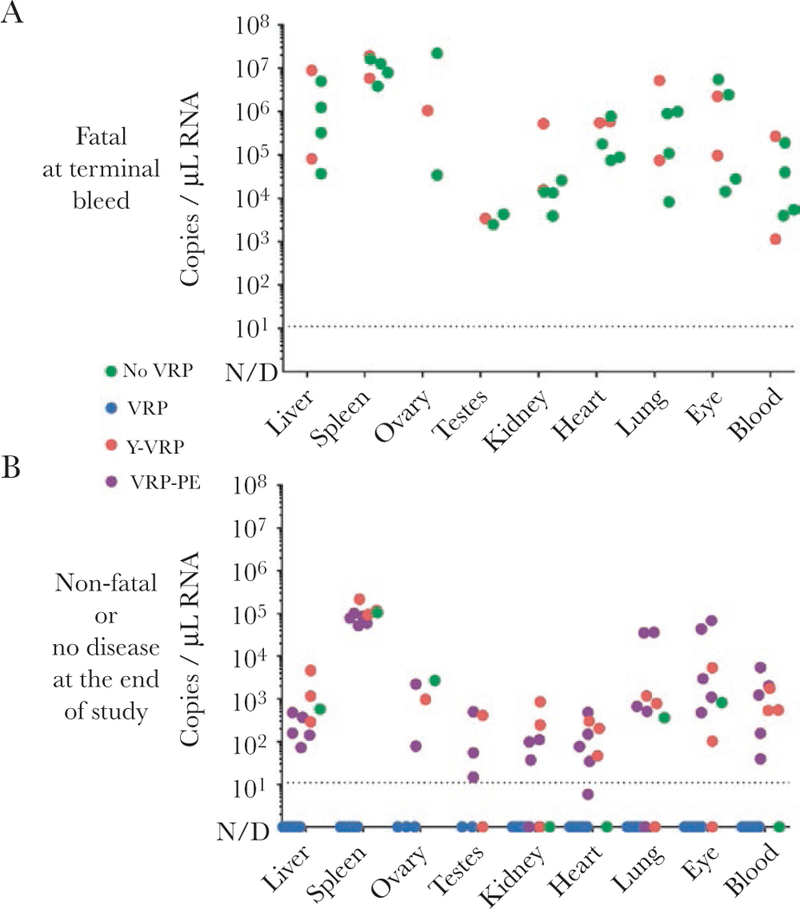

Dissemination of LASV infection was determined by qRT-PCR analyses of tissues collected at the time of euthanasia. Viremia was detectable by PCR in all animals that succumbed to disease, and LASV RNA was present in all examined tissues in these animals (liver, spleen, ovary/testes, kidney, heart, lungs, eyes, and blood) (Figure 4, Supplementary Table 1). In contrast to other groups, at the end of the experiment, no LASV RNA was detected by PCR in the animals vaccinated with VRPs 28 days before infection; these animals never displayed signs of clinical disease. All but 1 of the surviving animals that had developed clinical disease were still viremic at the end of the experiment, with viral RNA detectable in most tissues examined. Consistently, the spleen had high viral RNA loads compared with other tissues. No apparent differences between viral RNA levels were noted among survivors in different groups. Measurements of selected blood chemistries at study completion (42 days p.i.) showed small but statistically significant (P < .05 as determined by Mann-Whitney test) differences in potassium, calcium, and albumin levels between survivors in the VRP and VRP-PE groups (Supplementary Figure 3, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 4.

Lassa virus (LASV) ribonucleic acid (RNA) in tissues of infected guinea pigs. (A) The LASV RNA levels in animals that succumbed to disease. Tissue samples were collected at the time of euthanasia. (B) Residual LASV RNA levels in surviving animals at the end of the experiment (42 days after challenge). The LASV RNA was quantified by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), and values are reported for each individual animal. Dashed line, quantification limit. The qRT-PCR data of each animal are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. N/D, not detected.

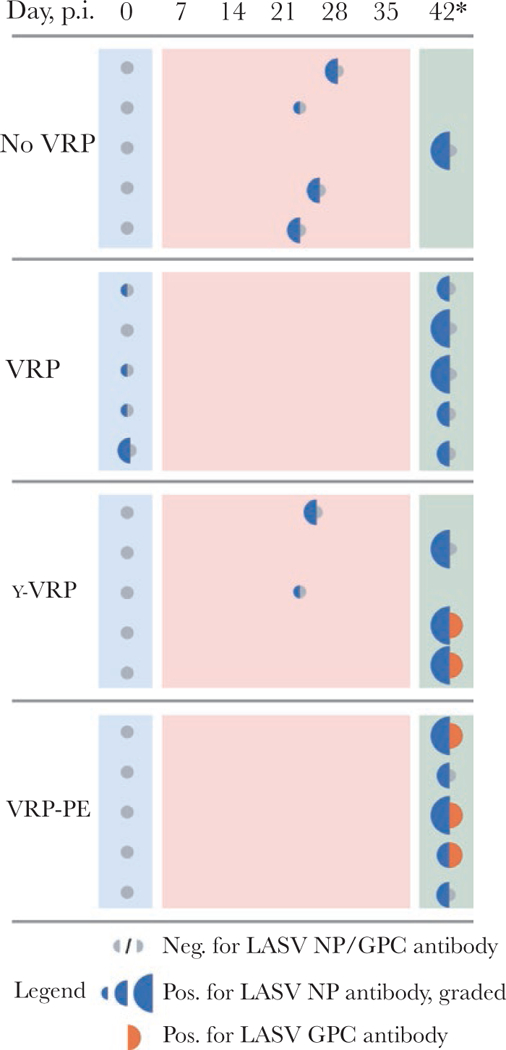

Four of the 5 animals in the VRP group had developed detectable antibodies against LASV NP but not GPC by the time of challenge (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 1). Accordingly, no neutralization activity was detected. All animals of the VRP group had NP antibodies at the conclusion of the study. All animals that succumbed also developed antibodies against NP by the time of euthanasia. Surviving animals seroconverted for LASV NP, and some of the survivors of clinical illness also developed antibodies against LASV glycoproteins.

Figure 5.

Antibody response to Lassa virus (LASV) replicon particle (VRP) vaccine and LASV challenge. Plasma samples collected prechallenge (28 days after vaccination of VRP, no-VRP, or γ-VRP groups; 1 day before vaccination for LASV replicon particle-postexposure [VRP-PE] group) and samples collected at the time of euthanasia were analyzed for LASV-specific antibodies using immunofluorescence assay (IFA). GPC-16 cells were transfected with plasmids coding for LASV nucleoprotein (NP), GPC, or Z, and plasma samples were used as primary antibodies in IFA staining. Blue represents NP reactivity, with larger half circles denoting higher intensity on a 3-step scale. Orange represents GPC reactivity, with only 1 intensity level noted. Gray represents negative sample. No reactivity against LASV Z was detected. Day postinspection (p.i.), day of sampling; 42*, study end point. Examples of IFA data are included in Supplementary Figure 4, and enzyme-linked immuno-sorbent assay data are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Several factors are relevant in preclinical evaluation of a vaccine candidate. Apart from protecting against the disease in a suitable animal model, factors such as potential barriers to licensing, practicality of manufacturing, and efficacy in a dosing regimen that models clinical use deserve consideration at an early stage.

One potential obstacle in vaccine development is the presence of unnecessary antigens. To remove any genes encoding irrelevant proteins, the reporter gene ZSG was deleted from our previous VRP vaccine candidate [16], so that only viral antigens are expressed and the GPC gene locus remains empty. This resulted in VRPs that more efficiently activated innate immune responses than either wild-type LASV or VRPs expressing ZSG (Supplementary Figure 1). Although discovering an explanation for this observation is beyond the scope of our current work, production of aberrant RNA structures that the cell recognizes as foreign is a possibility. A similar finding of an intact arenavirus exonuclease failing to prevent innate immunity activation when the viral intergenic region was modified has been reported before [23]. Importantly, despite the moderately elevated potential for innate immunity activation, these VRPs retained the efficient growth kinetics of ZSG-expressing VRPs. Furthermore, electron microscopy showed that VRPs budding from the producer cells retain the morphology of true LASV particles (Figure 2). Immunogenicity and uptake of virus-like particles are thought to be improved when the particles’ size mimic that of wild-type virus and when multiple adjacent surface epitopes are expressed [24]. The same can be expected of VRPs that carry replicating but incomplete genomes.

To evaluate manufacturing aspects beyond the scalability of VRP culture, raw supernatant was processed by ion exchange chromatography, a system that is commercially available in a variety of batch sizes. High yield of replicating particles was recovered when ion exchange was coupled with size-exclusion and sterile filtering (Figure 1C). Therefore, downstream processing of VRP cultures is feasible, at least on the research scale.

One part of assessing a preclinical vaccine candidate is clarifying the mechanism of vaccine-conferred protection. Cell-mediated immunity is thought to be the primarily effective arm of adaptive immune responses against LASV (for reviews, see [13, 15]), although monoclonal antibodies have shown high efficacy in passive immunotherapy [25, 26]. Evidence that supports the principal role of cell-mediated immunity over humoral immunity includes the findings that high-titer anti-LASV IgG and virus can be simultaneously present in the blood of human LF patients [27], and that even multiple doses of inactivated LASV fail to protect nonhuman primates from lethal LF despite inducing an antibody response [28]. In our study, 4 of 5 guinea pigs vaccinated with replicating VRPs developed LASV antibodies during the 28 days leading to challenge. These antibodies were directed against LASV NP, not LASV glycoproteins, and, accordingly, no neutralizing activity was detected. Although antibody response may have contributed to protection via mechanisms other than neutralization, the fact that NP antibodies were also detected in terminal samples of control animals that succumbed (Figure 5) implies a substantial role for cell-mediated immunity in VRP-induced protection.

In principle, VRPs could be used as material for an inactivated vaccine or a subunit vaccine. To assess feasibility of this approach, we vaccinated guinea pigs with VRPs that were irradiated and thus unable to replicate. All animals in this group became clinically ill, and 2 of 5 animals succumbed to disease (not a statistically significant difference to 4 of 5 animals in vehicle control group). Therefore, at least in the absence of adjuvants, the abortive single-cycle replication cycle of VRPs is critical for achieving protection.

Establishing time to protection is pertinent for vaccines against a disease like LF. Although vaccination against endemic LF should be considered in some regions of West Africa, future vaccination efforts will likely include use in outbreak settings, when clinical benefits must be achieved as soon as possible. To begin evaluating protective function of VRPs after LASV exposure, guinea pigs were vaccinated 1 day after challenge with a lethal dose of LASV. Although guinea pigs in this group developed clinical disease, all survived. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of tissues detected residual viral RNA in blood and most tissue samples of animals treated postexposure (Figure 4), and clinical chemistry showed that some differences between postexposure VRP-PE and pre-exposure VRP group animals remained (Supplementary Figure 3). Indeed, long-term sequelae are a significant problem in human survivors of LF, although few studies have examined sequelae in animal models. Recent work in the nonhuman primate model has proposed immune-mediated vasculitis as the cause of LF-associated hearing loss [29], and persistence of LASV in smooth muscle tissue and associated arteritis have also been described in guinea pig survivors [30]. In addition to observational studies, a reproducible model of LF-associated hearing loss has been described in STAT-1 knockout mice [31]. As suitable animal models are developed, the significance of prolonged LASV clearance and possibility of sequelae can be assessed. Absence of a clinical score, regained water consumption, and upward trend in body weight suggested that VRP-PE group animals were recovering from acute disease. Previous research has found that clinical signs could not be prevented even when a fully replicating, live-attenuated arenavirus vaccine was given at the time of challenge [32]. Even though disease was not prevented by postexposure vaccination in our study, the observed survival benefit is encouraging.

CONCLUSIONS

To the best of our knowledge, the VRP platform is the only single administration vaccine to result in complete protection against LASV without using a fully replicating viral vector or a live-attenuated arenavirus. This potency, together with promising results after postexposure administration, support further preclinical testing of the LF VRP vaccine candidate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Tatyana Klimova for assistance in editing this manuscript.

Financial support. This work was done with funds allocated for Viral Special Pathogens Branch by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.Fraser DW, Campbell CC, Monath TP, Goff PA, Gregg MB. Lassa fever in the Eastern province of Sierra Leone, 1970–1972. I. Epidemiologic studies. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1974; 23:1131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick JB, Webb PA, Krebs JW, Johnson KM, Smith ES. A prospective study of the epidemiology and ecology of Lassa fever. J Infect Dis 1987; 155:437–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monson MH, Frame JD, Jahrling PB, Alexander K. Endemic Lassa fever in Liberia. I. Clinical and epidemiological aspects at Curran Lutheran Hospital, Zorzor, Liberia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1984; 78:549–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bausch DG, Demby AH, Coulibaly M, et al. Lassa fever in Guinea: I. Epidemiology of human disease and clinical observations. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2001; 1:269–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaffer JG, Grant DS, Schieffelin JS, et al. Lassa fever in post-conflict Sierra Leone. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8:e2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troup JM, White HA, Fom AL, Carey DE. An outbreak of Lassa fever on the Jos Plateau, Nigeria, in January-February 1970. A preliminary report. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1970; 19:695–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macher AM, Wolfe MS. Historical Lassa fever reports and 30-year clinical update. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12:835–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Lassa Fever – Germany 2016. Available at: https://www.who.int/csr/don/23-march-2016-lassa-fever-germany/en/. Accessed 14 January 2019.

- 9.Cummins D, McCormick JB, Bennett D, et al. Acute sensorineural deafness in Lassa fever. JAMA 1990; 264:2093–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mateer EJ, Huang C, Shehu NY, Paessler S. Lassa fever-induced sensorineural hearing loss: a neglected public health and social burden. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:e0006187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. Global partnership launched to prevent epidemics with new vaccines 2017. Available at: http://cepi.net/cepi-officially-launched. Acessed 14 January 2019.

- 12.World Health Organization. 2018 annual review of the Blueprint list of priority diseases 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/en/. Accessed 14 January 2019.

- 13.Zapata JC, Medina-Moreno S, Guzmán-Cardozo C, Salvato MS. Improving the breadth of the host’s immune response to Lassa virus. Pathogens 2018; 7:e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallam HJ, Hallam S, Rodriguez SE, et al. Baseline mapping of Lassa fever virology, epidemiology and vaccine research and development. NPJ Vaccines 2018; 3:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warner BM, Safronetz D, Stein DR. Current research for a vaccine against Lassa hemorrhagic fever virus. Drug Des Devel Ther 2018; 12:2519–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kainulainen MH, Spengler JR, Welch SR, et al. Use of a scalable replicon-particle vaccine to protect against lethal Lassa virus infection in the guinea pig model. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:1957–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albariño CG, Bird BH, Chakrabarti AK, Dodd KA, Erickson BR, Nichol ST. Efficient rescue of recombinant Lassa virus reveals the influence of S segment noncoding regions on virus replication and virulence. J Virol 2011; 85:4020–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchholz UJ, Finke S, Conzelmann KK. Generation of bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) from cDNA: BRSV NS2 is not essential for virus replication in tissue culture, and the human RSV leader region acts as a functional BRSV genome promoter. J Virol 1999; 73:251–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruo SL, Mitchell SW, Kiley MP, Roumillat LF, Fisher-Hoch SP, McCormick JB. Antigenic relatedness between arenaviruses defined at the epitope level by monoclonal antibodies. J Gen Virol 1991; 72(Pt 3):549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martínez-Sobrido L, Giannakas P, Cubitt B, García-Sastre A, de la Torre JC. Differential inhibition of type I interferon induction by arenavirus nucleoproteins. J Virol 2007; 81:12696–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi X, Lan S, Wang W, et al. Cap binding and immune evasion revealed by Lassa nucleoprotein structure. Nature 2010; 468:779–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hastie KM, Kimberlin CR, Zandonatti MA, MacRae IJ, Saphire EO. Structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein reveals a dsRNA-specific 3’ to 5’ exonuclease activity essential for immune suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:2396–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwasaki M, Ngo N, Cubitt B, Teijaro JR, de la Torre JC. General molecular strategy for development of arenavirus live-attenuated vaccines. J Virol 2015; 89:12166–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohsen MO, Zha L, Cabral-Miranda G, Bachmann MF. Major findings and recent advances in virus-like particle (VLP)-based vaccines. Semin Immunol 2017; 34:123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cross RW, Mire CE, Branco LM, et al. Treatment of Lassa virus infection in outbred guinea pigs with first-in-class human monoclonal antibodies. Antiviral Res 2016; 133:218–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mire CE, Cross RW, Geisbert JB, et al. Human-monoclonal-antibody therapy protects nonhuman primates against advanced Lassa fever. Nat Med 2017; 23:1146–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson KM, McCormick JB, Webb PA, Smith ES, Elliott LH, King IJ. Clinical virology of Lassa fever in hospitalized patients. J Infect Dis 1987; 155:456–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCormick JB, Mitchell SW, Kiley MP, Ruo S, Fisher-Hoch SP. Inactivated Lassa virus elicits a non protective immune response in rhesus monkeys. J Med Virol 1992; 37:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cashman KA, Wilkinson ER, Zeng X, et al. Immune-mediated systemic vasculitis as the proposed cause of sudden-onset sensorineural hearing loss following Lassa virus exposure in cynomolgus macaques. MBio 2018; 9:e01896–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu DX, Perry DL, DeWald LE, et al. Persistence of Lassa virus associated with severe systemic arteritis in convalescing guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus). J Infect Dis 2019; 219:1818–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yun NE, Ronca S, Tamura A, et al. Animal model of sensorineural hearing loss associated with Lassa virus infection. J Virol 2015; 90:2920–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrion R Jr, Patterson JL, Johnson C, et al. A ML29 reassortant virus protects guinea pigs against a distantly related Nigerian strain of Lassa virus and can provide sterilizing immunity. Vaccine 2007; 25:4093–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.