Abstract

The ubiquitination status of RIPK1 is considered to be critical for cell fate determination. However, the in vivo role for RIPK1 ubiquitination remains undefined. Here we show that mice expressing RIPK1K376R which is defective in RIPK1 ubiquitination die during embryogenesis. This lethality is fully rescued by concomitant deletion of Fadd and Ripk3 or Mlkl. Mechanistically, cells expressing RIPK1K376R are more susceptible to TNF-α induced apoptosis and necroptosis with more complex II formation and increased RIPK1 activation, which is consistent with the observation that Ripk1K376R/K376R lethality is effectively prevented by treatment of RIPK1 kinase inhibitor and is rescued by deletion of Tnfr1. However, Tnfr1−/− Ripk1K376R/K376R mice display systemic inflammation and die within 2 weeks. Significantly, this lethal inflammation is rescued by deletion of Ripk3. Taken together, these findings reveal a critical role of Lys376-mediated ubiquitination of RIPK1 in suppressing RIPK1 kinase activity–dependent lethal pathways during embryogenesis and RIPK3-dependent inflammation postnatally.

Subject terms: Necroptosis, Transgenic organisms, Inflammation, Ubiquitylation

RIPK1 integrates signals that drive both NF-κB activation and cell death pathways. Here Zhang et al. generate RIPK1 knock-in mice lacking a major ubiquitination site and demonstrate that this modification is important to suppress cell death during embryogenesis and inflammation postnatally.

Introduction

RIPK1, an essential signaling node in various innate immune signaling pathways, is most extensively studied in the TNFR1 signaling pathway. Ligation of TNFR1 results in the rapid formation of a signaling complex termed complex I or TNFR1-Siganaling complex (TNFR1-SC) which is composed of TRADD, RIPK1, TRAF2, and cIAP1/21,2. Following recruitment, RIPK1 is polyubiquitinated by multiple forms of ubiquitin chains which provides docking sites for two protein complexes, the TAB/TAK complex comprising TAK1 and TAB2/3, as well as the IKK complex comprising NEMO, IKKα, and IKKβ3–6. The individual formation of these two complexes leads to activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways and therefore promotes cell survival. Nevertheless, under certain circumstances when the pro-survival signal emanating from complex I is perturbed, RIPK1 dissociates from complex I and recruits FADD and Caspase-8 to form complex IIa, and this leads to initiation of apoptosis1,7–11. However, when apoptosis is inhibited, RIPK1 can interact with RIPK3 to form an amyloid-like complex termed complex IIb or necrosome, resulting in activation of necroptosis12–17.

Recently, by extensive genetic studies on RIPK1 signaling pathways, the in vivo role of RIPK1 in regulating both cell survival and cell death has been revealed. Genetic deletion of Ripk1 in animals leads to postnatal lethality with widespread cell death in lymphoid and adipose lineages18. Ablation of Caspase-8/Fadd and Ripk3 allows for normal development and maturation of Ripk1-deficient mice19–22. Similarly, conditional deletion of Ripk1 in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) results in premature death in mice accompanied by extensive apoptosis in intestine and ensuing inflammation23,24. These phenotypes are largely resolved in mice lacking intestinal Fadd/Caspase-8 or both Fadd and Ripk323,24. In addition, the mice with keratinocyte-specific Ripk1 deficiency progressively develop severe inflammatory skin lesions that are fully prevented by deletion of Ripk3 or Mlkl24. Therefore, RIPK1 seems to be a suppressor of lethal pathways engaged by FADD/Caspase-8 and RIPK3/MLKL. However, RIPK1 is also suggested to mediate cell death in some contexts. Ablation of Ripk1 prevents early embryonic lethality induced by Caspase-8 or Fadd, although these mice succumb to early postnatal lethality similar to Ripk1 deficient mice21,22,25. Another striking study showed that mice with homozygous Ripk3D161N died at E10.5 but were completely rescued by co-deletion of Ripk126. These investigations revealed an opposite function of RIPK1 which can also induce cell death. Therefore, the paradoxical roles of RIPK1 raise the following fundamental question: what is the switch for two opposing functions of RIPK1?

RIPK1 consists of an N-terminal serine/threonine kinase domain, an intermediate domain, and a C-terminal death domain (DD)27,28. The kinase activity is essential for induction of necroptosis and RIPK1-dependent apoptosis but is dispensable for NF-κB activation29–31. Animals with kinase-inactive mutant RIPK1 develop normally and are protected from TNF-α induced necroptosis in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that the pro-survival function of RIPK1 does not require RIPK1 kinase activity32,33. The intermediate domain contains a RIP homotypic interaction motif (RHIM) which binds the RHIM of RIPK3 to initiate necroptosis, whereas the genetic studies reveal a critical role of RHIM in inhibiting ZBP1/RIPK3/MLKL-dependent necroptosis during development and inflammation34–36. In addition, a recent work has shown that DD-mediated RIPK1 dimerization is crucial for RIPK1 activation, and mice with mutant DD are resistant to RIPK1-dependent apoptosis and necroptosis37. Thus, although these genetic studies have demonstrated that RIPK1 is involved in mediating apoptosis, necroptosis and cell survival, the mechanism by which RIPK1 regulates these pathways in vivo remains unclear.

Given that the ubiquitination status of RIPK1 is critical for the transition of complex I to complex II, a clue to the answer may come from a major functional ubiquitination site K377 of human RIPK1, which provides a docking site for the K-63 linked polyubiquitin chain and mediates the recruitment of TAK1 and IKK complexes3,5,38,39. In vitro studies have shown that substitution of Lys-377 with arginine (K377R) blocked RIPK1 ubiquitination and TNF-α-mediated NF-κB activation and sensitized cells to TNF-α-induced apoptosis3,5,38,39. However, the in vivo function of K377, which is the key to uncover the enigma of the paradoxical roles of RIPK1, has not been established.

In this study, we generate mice endogenously expressing RIPK1K376R, a single amino acid change in K376 of mouse RIPK1, which is homologous to K377 of human RIPK1. Strikingly, mice bearing Ripk1K376R/K376R die at embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) with excessive cell death in embryonic tissues and the yolk sac. Accordingly, Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) expressing RIPK1K376R are defective in TNF-α-induced ubiquitination and are more sensitive to TNF-α-induced apoptosis and necroptosis. The excessive cell death in mutant embryos which can be effectively prevented by Nec-1 treatment is proved to be dependent on the kinase activity of RIPK1. Intriguingly, Ripk1K376R/− mice with only half amounts of mutant RIPK1K376R are viable although these mice develop systemic inflammation after birth. Besides, ablation of Fadd and Ripk3/Mlkl rescues Ripk1K376R/K376R mice from embryonic lethality and allows the animals to grow into fertile adults, indicating that the lethal phenotypes of mutant mice are caused by FADD-dependent apoptosis and RIPK3/MLKL dependent necroptosis. Furthermore, deletion of Tnfr1 rescues Ripk1K376R/K376R mice at the embryonic stage but fails to prevent the postnatal systemic inflammation of the mutant mice. Importantly, Ripk3 deficiency prevents lethal inflammation of Tnfr1−/− Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, suggesting that ubiquitination of RIPK1 is also involved in regulating inflammation during postnatal development. Thus, our findings provide genetic evidences that Lys376-mediated ubiquitination of RIPK1 plays critical roles in regulating both embryogenesis and inflammation processes.

Results

Ripk1K376R/K376R mice die during embryogenesis

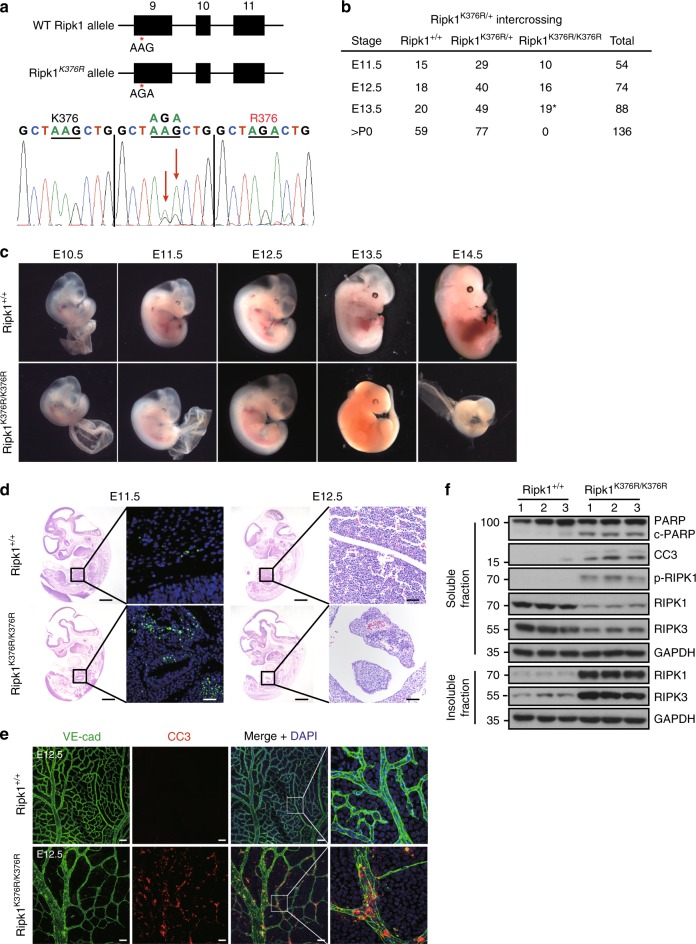

To address the potential role of RIPK1 ubiquitination in vivo, we generated knock-in mice with Lysine on a key ubiquitination site mutated to Arginine (K376R) (Fig. 1a). Unexpectedly, unlike Ripk1−/− mice that died within 3 days after birth, Ripk1K376R/K376R mice died during embryogenesis as intercrossing of heterozygous mice only generated heterozygous and wild-type (WT) offspring (Fig. 1b). Ripk1K376R/+ mice had the same normal life span as WT littermates, excluding the possibility that RIPK1K376R acted as a dominant negative mutant. To gain more insight into the lethality of Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, we performed timed pregnancies by mating heterozygous animals. The results showed that Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos and their yolk sacs appeared normal at E11.5 (Fig. 1c). However, staining for TUNEL revealed increasing dead cells in fetal livers of the mutant embryos (Fig. 1d). At E12.5, although the appearances of Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos were normal, histological examination showed remarkable tissue losses in parts of fetal livers (Fig. 1c, d). Immunoblot analysis showed activated caspase-3 and the cleavage of PARP, as well as aggregations of RIPK1 and RIPK3 were clearly detected in body tissues of mutant embryos, suggesting that activation of apoptosis and necroptosis contributes to the cell death in mutant embryos (Fig. 1f). Besides, immunostaining of yolk sacs for VE-cadherin revealed obvious vascular abnormalities with remarkably enhanced caspase-3 activation in the yolk sacs of mutant embryos, indicating that the cell death induced by this mutation has effects on both embryonic tissues and yolk sacs (Fig. 1e). At E13.5 and E14.5, Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos were anemic with apparent developmental abnormalities which indicate the death of the mutant embryos (Fig. 1c). Therefore, these results suggest that germline mutation of Ripk1K376R/K376R causes embryonic lethality at E12.5 with excessive cell death including apoptosis and necroptosis.

Fig. 1.

Ripk1K376R/K376R mice die during embryogenesis. a Organization of the Ripk1K376R mutant allele. Lysine (AAG) was mutated to Arginine (AGA) at the 376 position in RIPK1. The mutation was confirmed by sequencing. b Observed numbers of embryos or live born pups of the indicated genotypes at various developmental stages from Ripk1K376R/+ mice intercrosses. Asterisk indicates the abnormal embryos. c Whole-mount dark field images of embryos with indicated genotypes. Images are representative of embryos from E10.5 (n = 5), E11.5 (n = 10), E12.5 (n = 16), E13.5 (n = 19), E14.5 (n = 5). d Representative Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained and TUNEL-stained fetal livers from mouse embryos of the indicated genotypes (Scale bars, 1 mm). Images are representative of fetal livers from wild-type (n = 3) and Ripk1K376R/K376R (n = 3). Scale bars, 50 μm. e Immunostaining for VE-cad (green) and cleaved caspase-3(CC3) (red) on yolk sacs from wild-type and Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos. Scale bars, 100 μm. Images are representative of embryos from E12.5 (n = 3/genotype). f The body samples from E12.5 embryos were analyzed by western blot and immunoblotted for PARP, CC3, p-RIPK1(S166), RIPK1, and RIPK3

K376R blocks the ubiquitination of RIPK1

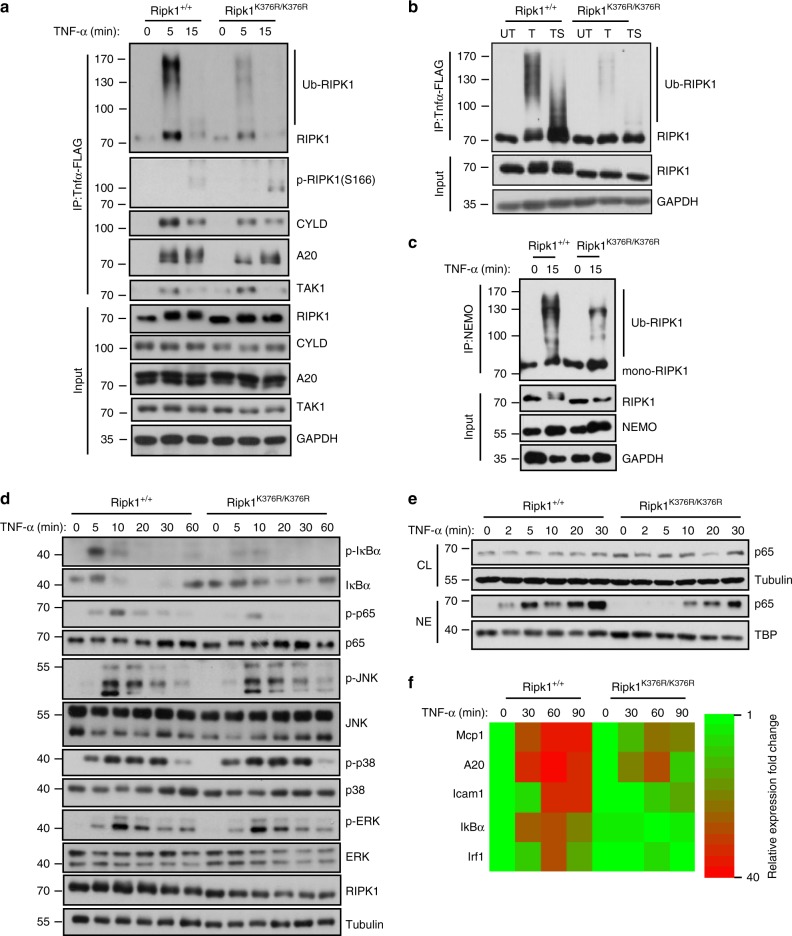

To investigate the contribution of RIPK1 K376 on diverse signaling, we stimulated primary MEFs from Ripk1K376R/K376R mice and Ripk1+/+ mice with TNF-α. Within 5 min of TNF-α stimulation, obvious ubiquitination of RIPK1 in complex I was detected in Ripk1+/+ cells, whereas a significant reduction in RIPK1 ubiquitination was observed in Ripk1K376R/K376R cells (Fig. 2a). Accordingly, the interaction between RIPK1 and NEMO was markedly weakened in Ripk1K376R/K376R cells (Fig. 2c). Pre-treating cells with Smac mimetics, a cIAP antagonist, remarkably inhibited the ubiquitination of RIPK1 in response to TNF-α, suggesting that ubiquitination of RIPK1 on K376 was mainly mediated by E3 ubiquitin ligases cIAP1/2 (Fig. 2b). Immunoprecipitation of ubiquitin chains showed that K63 ubiquitination of RIPK1 was more profoundly affected by K376R mutation (Supplementary Fig. 1a), which was consistent with previous reports that showed the polyubiquitin chains on RIPK1 were linked primarily through K63 of ubiquitin3,40. To determine if the ubiquitination of RIPK1 on K376 was required for NF-κB activation, we performed a time-course experiment by treating cells with TNF-α. In Ripk1+/+ cells, IκBα was phosphorylated within 5 min in response to TNF-α and was rapidly degraded (Fig. 2d). Consequently, phosphorylation and gradual translocation of p65 were observed (Fig. 2d, e), which activated the transcription of target genes (Fig. 2f). In contrast, in Ripk1K376R/K376R cells, IκBα activation was dramatically blocked, and subsequent translocation of p65 was delayed which led to impaired transcriptional induction of NF-κB-targeted genes (Fig. 2d–f). Importantly, except for NF-κB pathway, other signaling pathways in Ripk1K376R/K376R cells such as activation of JNK, p38, and Erk1/2 were almost unaffected (Fig. 2d), indicating a distinctive role of RIPK1K376R in activating NF-κB signaling in MEFs. Thus, our results show a critical role of K376 in mediating RIPK1 ubiquitination and NF-κB activation in response to TNF-α stimulation.

Fig. 2.

K376R blocks the ubiquitination of RIPK1 and NF-κB activation upon TNF-α stimulation. a Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were treated with Flag-TNF-α (100 ng/ml) for the indicated periods of time, complex I was immnoprecipitated using anti-FLAG beads, endogenous RIPK1 ubiquitination and indicated proteins were detected by western blotting. b Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were stimulated by Flag-TNF-α (100 ng/ml) for 5 min with or without pretreatment of Smac mimetics, complex I was immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG beads, endogenous RIPK1 ubiquitination were detected by western blotting. Abbreviations are as follows: T Flag-TNF-α stimulation, TS Flag-TNF-α stimulation with Smac mimetics pretreatment. c Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were treated with TNF-α (100 ng/ml) for 15 min and then NEMO was immunoprecipitated. Ubiquitinated RIPK1 was detected with RIP1 antibody. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies. d Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were treated with TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for the indicated periods of time, signaling pathways including NF-κB, JNKs, p38, and ERKs were examined by western blotting. e Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were treated with TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for 5 min. P65 nuclear translocation was examined by western blotting. Abbreviations are as follows: NE nuclear extracts, CL cell lysates. f Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were treated with TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for the indicated times, mRNA transcription change of NF-κB targeted genes were determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR)

RIPK1K376R promotes both apoptosis and necroptosis

Defective polyubiquitination of RIPK1 has been proposed to promote TNF-α induced apoptosis in Jurkat T cells3,5,38. However, in MEFs, we found that the disruption of RIPK1 ubiquitination mediated by K376R sensitized cells to not only apoptosis but also necroptosis. In response to TNF-α, much more Ripk1K376R/K376R cells underwent cell death compared to Ripk1+/+ control cells (Fig. 3a). After 24 h of TNF-α treatment, cleaved caspase-3 and phosphorylated MLKL were clearly detected in Ripk1K376R/K376R cells, indicating the simultaneous occurrence of apoptosis and necroptosis (Fig. 3b). In line with these results, mutant RIPK1K376R was found in complex II after TNF-α stimulation for 12 h, suggesting that RIPK1K376R promoted RIPK1 transition from complex I to complex II which led to the subsequent apoptosis and necroptosis (Fig. 3d). Besides, stimulating MEFs with TNF-α combined with Smac mimetics (TS), Ripk1K376R/K376R cells showed more sensitivity than the Ripk1+/+ cells did (Fig. 3a). In the presence of caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk (Z), TS induced higher level of necroptosis in Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs compared with Ripk1+/+ cells as the oligomerization of phosphorylated MLKL and aggregation of RIPK1 and RIPK3 were detected in Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs earlier than in Ripk1+/+ MEFs (Fig. 3a, c).

Fig. 3.

Cells bearing RIPK1K376R/K376R are more susceptible to TNF-α induced apoptosis and necroptosis. a Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were treated with T, TS, TSZ, TC, TCZ for indicated times, respectively. Cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo kit. The data are represented as the mean ± SEM of MEFs derived from 3 embryos. P values were determined by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Abbreviations are as follows: UT untreated, TSZ TNF-α (20 ng/ml)+Smac mimetic(100 nM) +zVAD(20 μM); TSZN, TNF-α+Smac mimetic +zVAD+Necrostatin-1 (20 μM); TC, TNF-α+CHX (20 ng/ml); TCZ, TNF-α+CHX +zVAD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. b Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were treated with mouse TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for indicated times, the cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies. c Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were treated with TSZ or TSZN for 3 h, the cell lysates were resolved on non-reducing gel and immunoblotted with anti-p-MLKL antibody. d Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were treated with mouse TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for 12 h, anti-RIPK1 was used to immunoprecipitate complex and immunocomplexes were analyzed by western blotting using indicated antibody

We next investigated the effect of NF-κB signaling defects in Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs on its sensitivity to cell death. Interestingly, activating NF-κB signaling by P65S275D overexpression failed to rescue mutant cells from TNF-α induced apoptosis and necroptosis (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Moreover, when treated with TNF-α combined with cycloheximide (CHX) which blocked NF-κB-dependent gene expression, Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were still more sensitive to cell death than the Ripk1+/+ control (Fig. 3a).These results argued against NF-κB defects being the leading cause for enhanced cell death in mutant cells. Therefore, we conclude that RIPK1K376R promotes the formation of complex II to facilitate the induction of apoptosis and necroptosis.

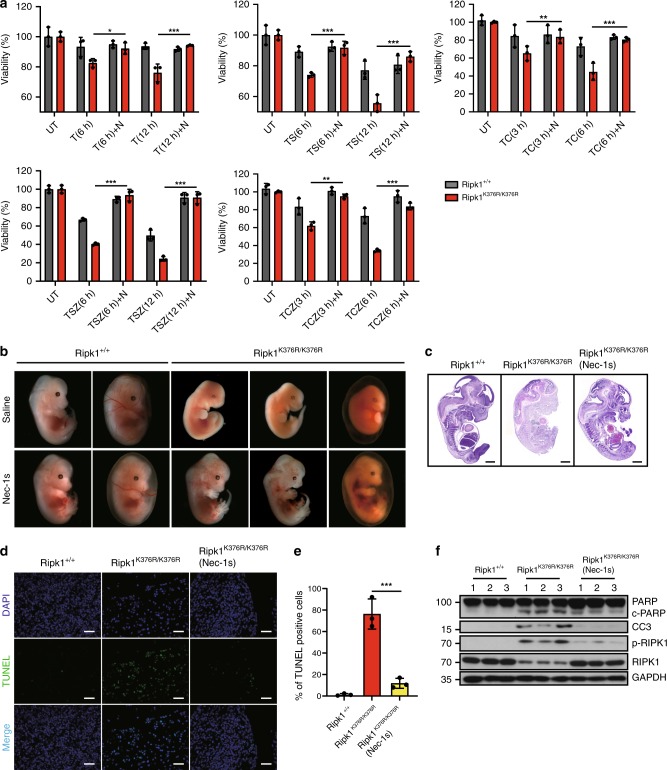

RIPK1K376R induced cell death relies on its kinase activity

It has been shown that the activation of RIPK1 kinase activity, which promotes autophosphorylation of RIPK1, is critical for the transition from complex I to complex II29. Using phospho-Ser166-RIPK1 (p-RIPK1(S166)) antibody as a marker of RIPK1 activation, we found more phosphorylated RIPK1 in both complex I and complex II in TNF-α-stimulated Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs (Figs. 2a, 3d). Thus, we wondered whether RIPK1K376R -induced cell death relied on the kinase activity of RIPK1. Treatment of Necrostatin-1(Nec-1s or N), a RIPK1 kinase inhibitor, efficiently prolonged the survival of Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs in response to TNF-α (or TC or TS) induced apoptosis and necroptosis (Fig. 4a). Similar results were obtained from treatments of TSZ or TCZ (Fig. 4a). Consistently, we found that the level of p-Ser166 RIPK1 was elevated in mutant cells and was significantly blocked by Nec-1s (Fig. 5c). Consequently, levels of cleaved caspase-3 and p-MLKL were reduced as well, indicating that RIPK1 ubiquitination on K376 is required for suppressing RIPK1 kinase-mediated the apoptosis and necroptosis (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 4.

Treatment of Nec-1s inhibits cell death induced by RIPK1 K376R. a Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were treated with T, TS, TSZ, TC, TCZ for indicated times with or without Nec-1s as indicated. Cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo kit. The data are represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). P values were determined by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. b Pregnant Ripk1K376R/+ females were fed with Nec-1s (50 mg/kg) or saline solution once per day since day 9.5 of gestation and sacrificed on day 13.5. Representative embryos with indicated genotypes were presented. c Representative H&E staining (scale bars, 1 mm) and d TUNEL staining of fetal livers from mouse embryos of the indicated genotypes. Each image is representative of at least three embryos. Scale bars, 50 μm. e Quantification of TUNEL positive cells in Fig. 4d. The results are represented as ± SEM of three embryos per group. P value was calculated by Student’s t-test (***p < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. f The fetal liver samples from three embryos per group were analyzed by western blot and immunoblotted with PARP, CC3, p-RIPK1(S166), and RIPK1

Fig. 5.

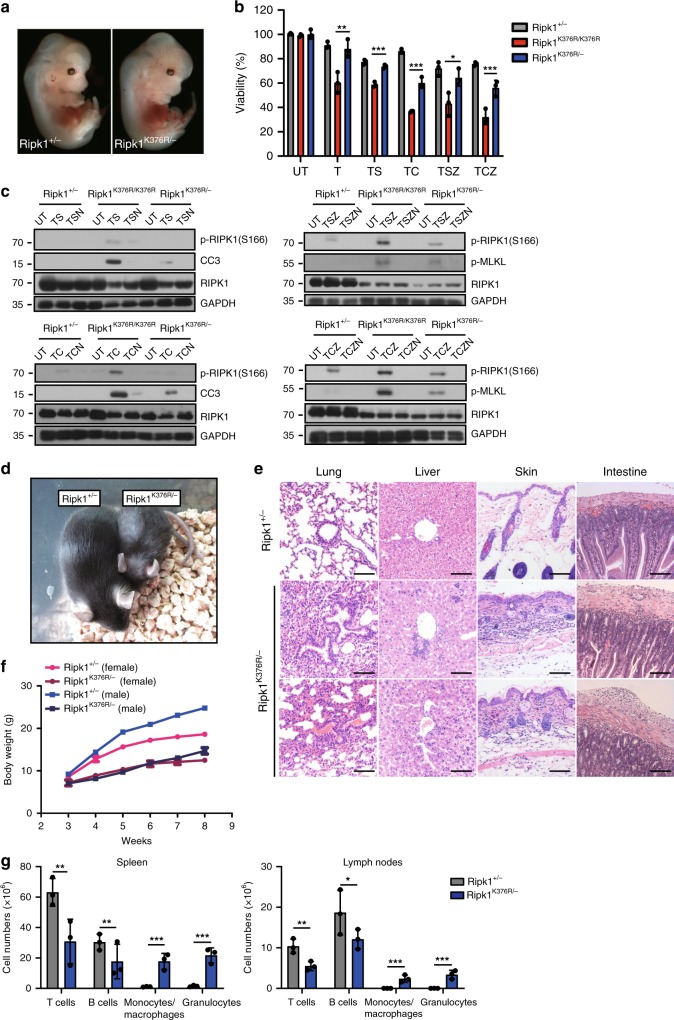

Ripk1K376R/− mice are viable but display systemic inflammation. a Representative whole-mount dark field images of E13.5 embryos with indicated genotypes. b Ripk1+/−, Ripk1K376R/K376R, and Ripk1K376R/− MEFs were treated with T, TS, TSZ, TC, and TCZ, respectively. Cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo kit. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of MEFs derived from three embryos. P values were determined by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Abbreviations are as follows: UT untreated, TSZ TNF-α (20 ng/ml)+Smac mimetic(100nM) +zVAD(20 μM), TSZN TNF-α+Smac mimetic +zVAD+Necrostatin-1(20 μM), TC TNF-α+CHX(20 ng/ml), TCZ TNF-α+CHX +zVAD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. c Ripk1+/−, Ripk1K376R/K376R, and Ripk1K376R/− MEFs were treated with TS(6h), TSZ(2h), TC(3h), TCZ(1h) with or without Nec-1s. Western blottings of indicated proteins were shown. d Representative 8-week-old Ripk1K376R/K376R mouse and littermate control. e Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tissues from 4-week-old animals of the indicated genotypes. (Scale bars, 100 μm). f Plot of weight of littermate Ripk1+/− and Ripk1K376R/− mice. g Different cell subsets in spleens and LNs from 6-week-old mice with indicated genotypes were determined by flow cytometry using following markers: B cells (CD19+ or B220+), T cells (CD3+), Monocytes and macrophages (CD11b+), Granulocytes (Gr-1+). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3/genotype). P values were calculated by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source Data file

As we observed higher levels of p-RIPK1 in Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos (Fig. 1e), we next investigated the effect of Nec-1s on the Ripk1K376R/K376R lethality in vivo. Feeding heterozygous mothers with Nec-1s during gestation period effectively prevented the lethal phenotypes of homozygous descendants (Fig. 4b). Compared with Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos without Nec-1s treatment which were dead and anemic at E13.5, Nec-1s-treated mutant embryos appeared much more normal although their yolk sacs were not completely rescued (Fig. 4b). Histological examination showed that Nec-1s treatment profoundly prevented the tissue losses in Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos (Fig. 4c). Besides, immunoblot analysis confirmed that RIPK1 phosphorylation and apoptosis featured by CC3 in mutant embryos were inhibited by Nec-1s treatment (Fig. 4f). Consistently, the number of TUNEL positive cells in the fetal livers of Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos was significantly reduced by Nec-1s treatment, suggesting that the massive cell death was largely restrained by RIPK1 kinase inhibition (Fig. 4d, e). Taken together, these results suggest that RIPK1K376R-induced excessive cell death is primarily dependent on the kinase activity of RIPK1.

Ripk1K376R/− mice are viable but develop severe inflammation

Assuming that RIPK1 activation was responsible for the cell death in Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos, we next tested whether the amount of activated RIPK1 had an impact on this lethality. By crossing Ripk1K376R/+ into Ripk1+/− mice, we generated Ripk1K376R/− mice with only half amounts of RIPK1K376R. Strikingly, in contrast to Ripk1K376R/K376R mice which were totally abnormal at E13.5, Ripk1K376R/− mice developed normally (Figs. 1c, 5a). MEFs isolated from Ripk1K376R/− embryos were less sensitive to TNF-α induced apoptosis and necroptosis compared to Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs (Fig. 5b). Similar results were obtained when treating cells with TC, TS, TCZ, and TSZ (Fig. 5b). In line with these data, the high levels of p-RIPK1(S166) with cleaved caspase-3 and phosphorylation of MLKL detected in Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were profoundly reduced in Ripk1K376R/− MEFs (Fig. 5c). These results suggest that there is likely to be a threshold above which activated RIPK1K376R can trigger the lethal pathways during embryogenesis.

Intriguingly, Ripk1K376R/− mice can grow up into adulthood, although they displayed much smaller and had lower body weight than their littermate controls (Fig. 5d, f). Histological examination of 4-week-old to 8-week-old Ripk1K376R/− mice revealed signs of inflammation in multiple organs including skins, lungs, intestines, and livers (Fig. 5e). Flow cytometric analysis of Ripk1K376R/− spleens and lymph nodes revealed decreased numbers of T cells (CD3+) and B cells (B220+ or CD19+) while remarkably increased numbers of granulocytes (Gr-1+) and macrophages (CD11b+) (Fig. 5g), indicating that Ripk1K376R/− mice developed systemic inflammation after birth. Collectively, these data suggest that K376-mediated RIPK1 ubiquitination is critical for restraining inflammation during postnatal development.

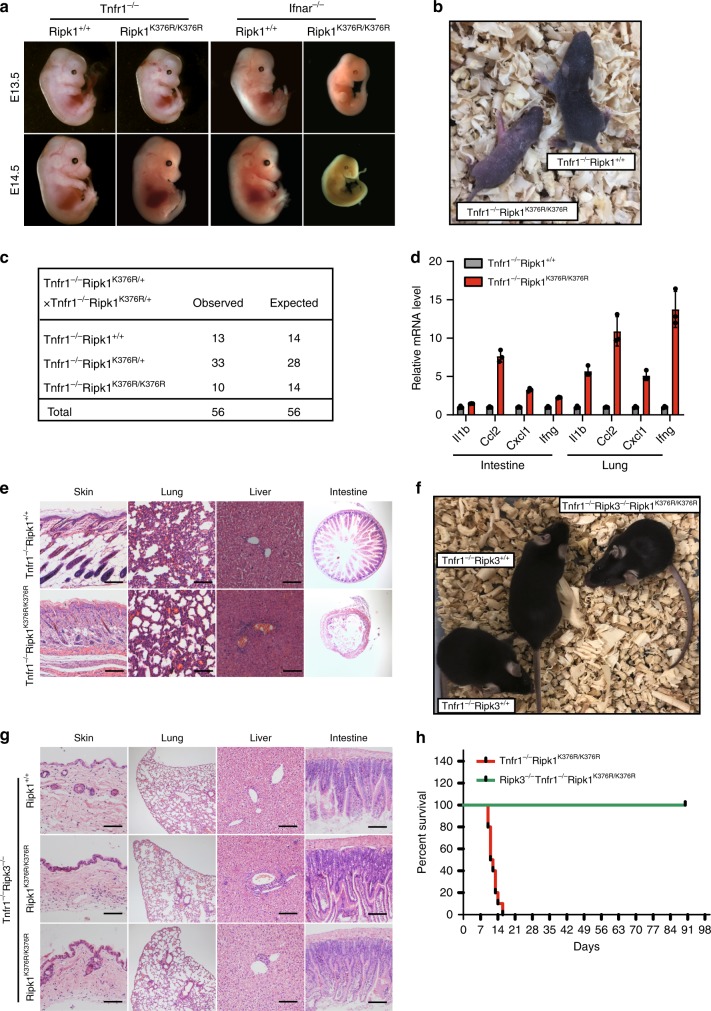

Loss of Tnfr1 rescues the lethality of Ripk1K376R/K376R mice

To further investigate the upstream signaling inducing the Ripk1K376R/K376R lethality, we crossed Ripk1K376R into Tnfr1−/− or Ifnar−/− background to generate Tnfr1−/− Ripk1K376R/K376R and Ifnar−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, respectively. Results from timed pregnancies showed that deletion of Tnfr1 fully rescued the Ripk1K376R/K376R lethality during embryonic development (Fig. 6a–c). In contrast, ablation of Ifnar had no effect on the Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos and failed to rescue them from embryonic lethality (Fig. 6a). Consistent with these observations, the numbers of TUNEL-positive cells were remarkably increased and cleaved caspase-3 was clearly detected in the fetal livers of Ifnar−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Thus, these results suggest that TNFR1, rather than IFNR1, induces signaling that triggers the death of Ripk1K376R/K376R mice during embryogenesis.

Fig. 6.

Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice die postnatally due to RIPK3-dependent inflammation. a Whole-mount dark field images of embryos with indicated genotypes. Images are representative of embryos from E13.5 (n = 8) and E14.5 (n = 9). b Representative 1-week-old Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice and littermate control. c Expected and observed frequency of genotypes in offspring at weaning from crosses of Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/+. d Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the mRNA expression of cytokines in lungs and intestines from 1-week-old pups with indicated genotypes. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. e Representative H&E stained tissues from 1-week-old Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R and littermate control. Scale bars, 100 μm. f Representative 8-week-old Tnfr1−/−Ripk3−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R and its littermate controls. g Representative H&E stained tissues from 8-week-old Tnfr1−/−Ripk3−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R and littermate control. Scale bars, 100 μm. h Kaplan-Meier plot of mouse survival from intercrosses of Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/+Ripk3+/−

Although ablation of Tnfr1 prevented the embryonic death of Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice died around 2 weeks after birth (Fig. 6h). These mice succumb to systemic inflammation as obvious inflammatory cell infiltrations were observed in the skin, lung, liver, and intestine (Fig. 6e). Quantitative RT-PCR examination revealed enhanced levels of inflammatory cytokines in the lungs and intestines of Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice (Fig. 6d). In addition, the composition of immune cells in spleen and thymus of mutant mice was largely disrupted. Compared with Tnfr1−/− controls, the numbers of lymphocytes (CD3+ cells and B220+ cells) in the spleen were reduced, whereas the numbers of myeloid cells (CD11b+ or Gr-1+ cells) were greatly increased (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e). In the thymus, the total cell counts were dramatically reduced with abnormal compartments of T cells in which CD4+ and CD8+ single-positive populations were augmented while CD4+CD8+ double-positive population was decreased (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e). These results showed that the homeostasis of the immune system in Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice was disrupted, suggesting that K376-mediated ubiquitination of RIPK1 also contributes to regulating immune homeostasis.

We then sought to address the cause for the postnatal death of Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R. Histological examination showed multiple tissues from Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice displayed tissue loss and abnormal architecture, indicating that these phenotypes may be a result of massive cell death (Fig. 6e). Using cleaved caspase-3 as a marker for apoptosis, we observed no significantly positive cells detected in skins, livers and intestines of Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, suggesting that apoptosis was not the major cause for the phenotypes (Supplementary Fig. 2c). However, when we treated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from the Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice with LPS or Poly(I:C) in the presence of zVAD, the cells were much more vulnerable compared to their controls and the phosphorylations of RIPK1 and RIPK3 were more significantly induced in these cells, suggesting that RIPK3-mediated necroptosis plays an important role in this circumstance (Supplementary Fig. 2f, g). Therefore, we tested the contribution of RIPK3-mediated signaling by crossing Ripk3−/− into Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice. Importantly, deletion of Ripk3 rescued the postnatal death of Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R and allowed them normal development (Fig. 6f, h). Moreover, histological examination indicated that Ripk3 ablation markedly prevented the tissue loss and inflammation in Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice (Fig. 6g). Taken together, these findings reveal a critical role of K376-meidated RIPK1 ubiquitination in restraining RIPK3-dependent inflammation during postnatal development.

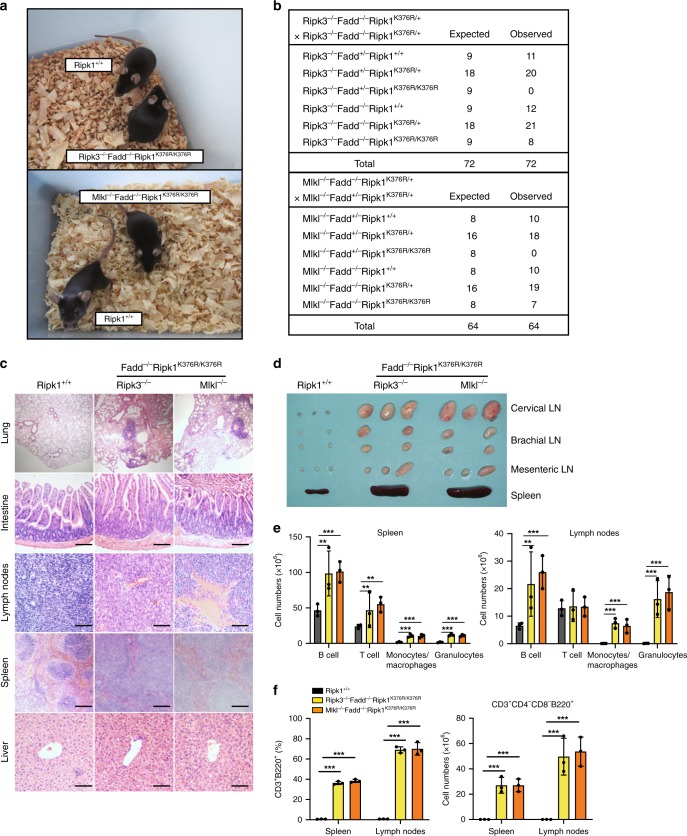

Ablation of Fadd and Ripk3/Mlkl rescues Ripk1K376R/K376R mice

Given that the activation of RIPK1 led to two subsequent signaling pathways including FADD/Caspase-8-mediated apoptosis and RIPK3/MLKL-mediated necroptosis, we next asked whether Ripk1K376R/K376R lethality was caused by these pathways. First, we crossed Ripk1K376R/+ into Ripk3−/− or Mlkl−/− mice to test the contribution of necroptosis. The resulting Ripk3−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R and Mlkl−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice died during embryogenesis as we observed no homozygous descendant from heterozygous breeding (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The results from timed pregnancies showed that Ripk3−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R and Mlkl−/− Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos appeared normal at E13.5 but displayed apparent developmental abnormalities at E14.5 (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Although ablation of Ripk3 or Mlkl slightly prolonged the survival of Ripk1K376R/K376R embryos, the lethality was not prevented. These findings indicate the involvement of RIPK3/MLKL-independent pathways.

Next, we bred Ripk1K376R/+ into Ripk3−/−Fadd−/− and Mlkl−/−Fadd−/− mice to generate Ripk3−/−Fadd−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R and Mlkl−/−Fadd−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, respectively. Ablation of Fadd and Ripk3 or Mlkl fully rescued the embryonic lethality of Ripk1K376R/K376R mice and displayed normal development and maturation (Fig. 7a, b). MEFs isolated from these triple mutant mice were resistant to TNF-α triggered apoptosis and necroptosis while were defective in activating NF-κB signaling as Ripk1K376R/K376R cells, suggesting that massive cell death rather than impaired NF-κB activation contributes to the lethality of Ripk1K376R/K376R mice (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c). RIPK1K376R was widely detected in the major organs of triple-mutant mice and its expression levels were comparable to those of WT controls, suggesting that RIPK1K376R did not affect the expression of RIPK1 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). When aged, Ripk3−/−Fadd−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R and Mlkl−/−Fadd−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice developed lymphoproliferative syndrome with an accumulation of CD3+B220+ lymphocytes in peripheral lymphoid organs seen in Ripk3−/−Fadd−/− and Mlkl−/−Fadd−/− mice (Fig. 7d, f, Supplementary Fig. 4d)19–22,41–43. The disease was characterized by lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, which disrupted the normal architecture of the lymph nodes and spleen (Fig. 7c, d). Flow cytometric analysis revealed profoundly increased numbers of multiple cells in spleen and lymph nodes, including lymphocytes (T cells/B cells), macrophages and granulocytes (Fig. 7e). In addition, the inflammation was observed in multiple tissues of Ripk3−/−Fadd−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R or Mlkl−/−Fadd−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, indicating the occurrence of systemic inflammation (Fig. 7c). Collectively, these data indicate that blockade of both FADD-mediated apoptotic pathway and RIPK3/MLKL-mediated necroptotic pathway rescues the embryonic lethality of Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, although these mice develop lymphoproliferative diseases with systemic inflammation.

Fig. 7.

Embryonic lethality of Ripk1K376R/K376R mice is fully rescued by ablation of Fadd and Ripk3/Mlkl. a Representative photographs of mice with the indicated genotypes. b Predicted and observed frequencies in offspring from crosses of animals with the indicated genotypes. c Representative H&E-stained tissues from 12-week-old animals of the indicated genotypes. Results are representative of three mice of each genotype (Scale bars, 100 μm). d Representative lymphoid organs removed from 12-week-old mice of indicated genotypes. e Different cell subsets from 12-week-old animals were determined by flow cytometry using following markers: B cells (CD19+ or B220+), T cells(CD3+), Monocytes and macrophages(CD11b+), Granulocytes(Gr-1+). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3/genotype). P values were determined by Student’s t-test (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). f Percentages and cell numbers of CD3+B220+ lymphocytes in spleen and lymph nodes from 12-week-old mice of indicated genotypes. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3/genotype). P values were determined by Student’s t-test (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Discussion

In this report, we show that the disruption of RIPK1 ubiquitination in vivo by a point mutation at K376 causes embryonic lethality at E12.5, which is completely different from the observation in Ripk1 deficient mice. A fundamental question emerged from this result: why does germline Ripk1K376R mutation cause lethality during embryogenesis while deletion of Ripk1 does not? The answer to the question may come from the unique structure of RIPK1 which contains a C-terminal death domain (DD), an intermediate domain harboring a RHIM and an N-terminal Ser/Thr kinase domain. The DD and RHIM can, respectively, recruit FADD and RIPK3 to initiate extrinsic apoptosis and necroptosis, while the intermediate domain can mediate the activation of NF-κB signaling28,44,45. In our study, we substituted K376 of the intermediate domain with R376 to block polyubiquitination of RIPK1. This mutation leads to two consequences: the defective NF-κB activation and the excessive cell death. These findings allowed two conclusions: (1) K376-mediated RIPK1 ubiquitination is responsible to activate NF-κB in vivo and (2) K376-mediated RIPK1 ubiquitination is critical to suppress apoptosis and necroptosis during development. In fact, RIPK1K376R mutation does not affect the expression of RIPK1 and functions of other domains, but was prone to the activation of RIPK1. This can be prevented by RIPK1 kinase inhibitor Nec-1 or deletion of one Ripk1K376R allele, indicating that the excessive RIPK1 activation which subsequently causes the apoptosis and necroptosis leads to the lethality during embryogenesis. Therefore, RIPK1 ubiquitination restrains RIPK1 itself from activating cell death during embryonic development, and that’s why deletion of Ripk1 does not lead to lethal phenotypes at this stage.

Ripk1−/− mice die soon after birth, this lethality is initially thought to be due to the loss of the pro-survival function of RIPK1 which mediates NF-κB signaling46. The contribution of NF-κB signaling to maintain normal embryonic development has been investigated previously, and mice lacking the components of NF-κB die during embryogenesis due to massive cell death in multiple tissues47–49. Moreover, inactivating RIPK1 kinase can rescue the embryonic lethality of RelA-deficient mice50,51. The phenotypes of these mice resemble what we observed in Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, indicating that impaired NF-κB signaling may be a cause that leads to the embryonic lethality of Ripk1K376R/K376R mice. However, when treating Ripk1K376R/K376R cells with TNF-α combined with CHX which blocked NF-κB-dependent gene expression, Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were still more vulnerable to the stimuli. Furthermore, activating NF-κB signaling by p65S275D overexpression failed to prevent the cell death of mutant cells. Besides, it has been reported that RIPK1 K377-mediated (human RIPK1) inhibition of TNF-α induced apoptosis is independent on NF-κB at the early stage of stimulation38, which is consistent with what we observed in Ripk1K376R/K376R cells. Therefore, NF-κB defects might not be the leading cause of Ripk1K376R/K376R lethality.

The perinatal death of Ripk1−/− mice was fully rescued by ablation of both Caspase-8/Fadd and Ripk319–22. Thus, RIPK1 was considered to suppress lethal pathways engaged by FADD-Caspase-8 and RIPK3. However, the mechanism by which RIPK1 suppresses the perinatal lethality remains elusive. The mutation of RHIM in RIPK1 causes perinatal death similar to the observations from Ripk1−/− mice, and this lethality can be rescued by ablation of Ripk3 or Zbp135,36. These investigations suggest that RIPK1 suppresses the perinatal necroptosis mediated by RIPK3/ZBP1 through RHIM domain. In our study, ablation of Ripk3 rescues the postnatal death of Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice. Thus, we assume that RIPK1 K376 is important for restraining RIPK3-dependent necroptosis and ensuing inflammation after birth. Intriguingly, in the settings of RIPK1K376R mutation, RIPK1 fails to prevent the postnatal necroptosis through RHIM, suggesting that K376-mediated ubiquitination may regulate RHIM-mediated suppression of RIPK3-dependent necroptosis.

Although ablation of Tnfr1 rescued Ripk1K376R/K376R mice during embryonic development, Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice died postnatally. These results indicate RIPK1 ubiquitination on K376 may mediate divergent pathways at different stages of development. TNF/TNFR1 is the main upstream signal of K376-mediated pathways during embryonic development, while additional signals are involved after birth. Although it is not clear which signaling pathways participated, the investigations on Ripk1−/− mice could provide some candidates. Similar to our findings in Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, Tnfr1−/−Ripk1−/− mice died within 2 weeks after birth21. Interestingly, deletion of Trif or type I interferon receptor prolonged the lifespan of Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/− mice, although none of the mice survived past weaning21. In addition, deletion of MyD88 improved the survival time of Ripk1−/− mice22. Therefore, we assume that, in addition to TNFR1, IFNR1, and TRIF are of great possibility to trigger the RIPK1 K376-meidated pathways. Intriguingly, as ablation of Ripk3 rescues the lethality of Tnfr1−/−Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, the downstream signaling mediating the lethal phenotypes is dependent on RIPK3. Recent studies have implied that RIPK3 has more functions beyond mediating necroptosis, therefore, additional investigations on examining the contribution of MLKL in this signaling pathway are still required.

By changing its ubiquitination status in response to TNF-α, RIPK1 can transduce either a pro-survival or death signal. Germline mutation of RIPK1 K376 leads to embryonic lethality at E12.5, which was prevented by deletion of Tnfr1, though Tnfr1−/− Ripk1K376R/K376R mice died of RIPK3-mediated inflammation after birth. Remarkably, one copy of RIPK1 is required to prevent a Fadd/Ripk3 or Fadd/Mlkl dependent lethality in Ripk1K376R/K376R mice, possibly relating to a RIPK1 activation threshold (Supplementary Fig. 5). These genetic evidences provide a comprehensive understanding of the in vivo function of RIPK1 ubiquitination, which is essential for both embryonic development and immune homeostasis.

Importantly, these findings can help to explain some seemingly contradictory results from previously reported genetic studies. Furthermore, a more recent study has highlighted the role of RIPK1 in human disease asscoiated with immunodeficiency, arthritis, and intestinal inflammation, which confirmed the function of RIPK1 in humans immune system52. Therefore, the potential role of RIPK1 ubiquitination in regulating specific signaling pathways other than the TNF-α mediated pathway will be of great interest for providing new therapeutic opportunities in related human diseases, and mice bearing RIPK1K376R mutation can be used to explore the contribution of RIPK1 ubiquitination to a variety of mouse models of human diseases.

Methods

Mice

Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility. Ripk3−/−, Fadd+/− and Mlkl−/−, and Ifnar−/−mouse lines have been described earlier41,53. Ripk1K376R/+ and Ripk1+/− mice were generated by CRISPR-Cas9 mutation system (Bioray Laboratories Inc., Shanghai, China). The mouse Ripk1K376R mutation construct corresponds to the following genomic position (NC_000079.6) chr13: 34027834–34027836. Ripk1K376R/+ mouse genotyping primers: 5′ CCATCTCCAGCCCTCCTA and 5′ TGCACTGCAATTCCACGA amplified 690 bp DNA fragments for sequencing. Ripk1+/− mice were generated by a 101 bp deletion in the coding region of exon 2 using CRISPR-Cas9 mutation system with sgRNA (5′-GACCTAGACAGCGGAGGCTT-3′). Ripk1+/− mice genotyping primers (RIPK1-F: 5′-GTGGTACTTTGGGAGGTGGAGG-3′ and RIPK1-R: 5′-CAGGATGACAAATCCATGGCTTCTG-3′) amplified 430 bp wild-type, 329 bp knock-out DNA fragments. Additional information is provided upon request. All mice utilized in this study have been backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background for more than eight generations. Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Nutrition and Health, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Reagents

The Smac mimetic, Cycloheximide and LPS were purchased from Sigma. TNF-α and z-VAD were from R&D (Minneapolis, MN, USA) and Calbiochem (Anaheim, CA, USA), respectively. Necrostatin-1 was purchased from Enzo Life Science (Alexis, USA). The following antibodies were used for western blotting and immunoprecipitation experiments: RIPK1 (1:2000, BD Biosciences, 610459), RIPK1 (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, 3493P), p-RIPK1(1:1000, a gift from Junying Yuan’s lab), RIPK3 (1:5000, Prosci, 2283), p-RIPK3(1:1000. Abcam, ab195117), Caspase-8 (1:2000, Enzo Life Science, ALX-804-447-C100), MLKL (1:2000, Abgent, ap14272b), p-MLKL (1:1000, Abcam, ab196436), ß-actin (1:5000, Sigma, A3854), Tublin (1:5000, Sigma, T6199), IkBα (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9242S), p-IkBα (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9246S), p-ERK (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9101S), ERK (1:2000. Cell Signaling Technology,9102S), p-p38 (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9211S), p38 (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9228S), p-p65 (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, 3033S), p65 (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, 4764S), p-JNK (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9251S), JNK (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9252S), PARP (1:2000,Cell Signaling Technology, 9542S), Caspase-3 (1:1000,Cell Signaling Technology, 9662S), TBP (1:2000,Cell Signaling Technology, 44059S), FADD antibody was from Jianke Zhang’s lab (1:2000, Thomas Jefferson University). Cell viability was determined by measuring ATP levels using the Cell Titer-Glo kit (Promega).

Cell lines

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Hyclone, SH30243.LS) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, SH30084.03),1% penicillin(100 IU/ml)/streptomycin(100 μg/ml) and 2 mM L-glutamine under 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Primary Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1K376R/K376R MEFs were isolated from E11.5 littermate embryos. The head and visceral tissues were dissected and remaining bodies were incubated with 4 ml Tripsin/EDTA solution (Invitrogen, 25200072) per embryo at 37 °C for 1 h. After tripsinization, an equal amount of medium were mixed and pipetted up and down a few times. The primary MEFs were cultured in high-glucose DMEM containing 15% FBS. For immortalization, MEFs were transfected with SV40 small+large T antigen-expressing plasmid (Addgene, 22298) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, 11668019) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell survival assay

Cell survival was determined using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit (Promega, G7572) and the luminescence was recorded with a microplate luminometer (Thermo Scientific).

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Cells were harvested at different time points, washed with PBS and lysed with 1× SDS sample buffer containing 100 mM DTT. The cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation for 10 min at 12,000 × g, quantified by BCA kit (Thermo Scientific,23225), and then mixed with SDS sample buffer and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. The samples were separated using SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore) with 110 v for 1.5 h. The proteins were detected by using a chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific). To immunoprecipitate RIP1, cells were lysed with lysis buffer (Tris-HCl 20 mM (pH 7.5), NaCl 150 mM, EDTA 1 mM, EGTA 1 mM, Triton X-100 1%, Glycerol 10%, Protease Inhibitor cocktail, Sodium pyrophosphate 2.5 mM, β-Glycerrophosphate 1 mM, NaVO4 1 mM, Leupeptin 1 μg/ml). Cell lysates were incubated for 3 h with 1 μg of RIP1 antibody (BD Biosciences, 610459). After mixing end over end for overnight (4 °C) with 35 μl of G-Agarose beads, the agarose was collected and washed three times with lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitates were denatured in SDS, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted. To immunoprecipitate Complex I, cells were harvest in NP-40 buffer (Tris-HCl 20 mM (pH 7.5), NaCl 120 mM, EDTA 1 mM, EGTA 1 mM, NP-40 0.5%, Glycerol 10%, Protease Inhibitor cocktail, Sodium pyrophosphate 2.5 mM, β-Glycerrophosphate 1 mM, NaVO4 1 mM, Leupeptin 1 μg/ml) after stimulating with 100 ng/ml TNF-α-FLAG(Enzo Life Science, ALX-522-009-C050). The cell lysates were then incubated with FLAG-tagged beads (Sigma, A2220) for 4 h. The beads were then collected and washed 3 times with NP-40 buffer. Immunoprecipitates were denatured in SDS, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted. The unprocessed scans of all blots are provided as Supplementary Fig. 6 in the Supplementary Information.

MLKL oligomerization detection

Cells were harvested after TSZ or TSZN treatment and lysed with 2× DTT-free sample buffer (Tris-Cl (PH 6.8) 125 mM, SDS 4%, Glycerol 20%, Bromophenol blue 0.02%) immediately. Total cell lysates were separated using SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membrane, and immunoblotting was performed with MLKL antibodies.

Flow cytometry

Lymphocytes were isolated from the thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes of mice. Antibodies against mouse CD3 (1:1000, eBioscience,11-0031-82), CD4 (1:1000, eBioscience,47-0042-82), CD8 (1:1000,Biolegend,100732), B220 (1:1000, eBioscience,12-0452-83), Gr-1 (1:1000, eBioscience, 12-5931-83), CD11b (1:1000, eBioscience, 17-0112-83) were used for flow cytometry analysis in this study. Single cell suspension of lymphocytes was stained on ice for half an hour with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies in the staining buffer (1× PBS, 3% BSA, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1%NaN3). After staining, cells were washed twice with PBS and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS Aria III, BD biosciences).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After quantification, 1 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed to complementary DNA (Takara). Transcript levels of indicated genes were quantified by quantitative RT-PCR on an ABI 7500 real-time PCR instrument with SYBR Green. The sequences of primers are shown as follows. Mcp-1: 5'-AGGTGTCCCAAAGAAGCTGTA-3' and 5'-ATGTCTGGACCCATTCCTTCT-3'; A20: 5'-CTCAGAACCAGAGATTCCATGAAG-3' and 5'-CCTGTGTAGTTCGAGGCATGT-3'; Icam-1: 5'-CTTGGTAGAGGTGACTGA-3' and 5'- GCTGAAAAGTTGTAGACTG-3'; IκBα: 5'-GATCCGCCAGGTGAAGGG-3' and 5'-GCAATTTCTGGCTGGTTGG-3'; Irf1: 5'-CAGAGGAAAGAGAGAAAGTCC-3' and 5'-CACACGGTGACAGTGCTGG-3'; Il-1b: 5'- CCCAACTGGTACATCAGCAC-3' and 5'-TCTGCTCATTCACGAAAAGG-3'; Ccl2: 5'-TGAATGTGAAGTTGACCCGT-3' and 5'-AAGGCATCACAGTCCGAGTC-3'; Cxcl1: 5'-CAAGAACATCCAGAGCTTGAAGGT-3' and 5'-GTGGCTATGACTTCGGTTTGG-3’; Ifng: 5'-ACAGCAAGGCGAAAAAGGAT-3' and 5'-TGAGCTCATTGAATGCTTGG-3';

Statistical analysis

Data presented in this article are representative results of at least three independent experiments. The statistical significance of data was evaluated by Student’s t test and the statistical calculations were performed with GraphPad Prism software.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiaodong Wang (National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing, China) for providing Ripk3−/− mice, Jianke Zhang (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA) for providing Fadd+/− mice, Feng Shao (National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing, China) for providing Tnfr1−/− mice, and Qibin Leng (Institute Pasteur of Shanghai, Shanghai, China) for providing Ifnar−/− mice. We thank Junying Yuan for providing p-RIPK1(S166) antibody. We also thank Ronggui Hu (Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology) and Hui Xiao (Institute Pasteur of Shanghai, Shanghai, China) for providing reagent and technical support. We thank Yu Sun (UCLA, Los Angeles, California) for valuable suggestions and comments on this study. This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1304900, 2016YFA0500100) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771537, 31571426).

Author contributions

X.Z., Haiwei Z., and Haibing Z. conceived and designed the study; X.Z. and Haiwei Z. performed the experiments and analyzed data with assistance from C.X., X.L., M.L., W.P., and X.W.; B.Z. and Haikun W. analyzed data and provided technical support; D.L., Q.D., H.Y., and Hui W. provided essential reagents and intellectual input. X.Z., Haiwei Z., and Haibing Z. coordinated the project, interpreted results, and wrote the paper; Haibing Z. supervised the project.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data presented in this study are available within the figures and its Supplementary Information file. The source data underlying Figs. 3a, 4a, e, 5b, f, g, 6d, 7e, f and Supplementary Figs 1b, 2e, f are provided as a Source Data file. Other data that support the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xixi Zhang, Haiwei Zhang.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-11839-w.

References

- 1.Micheau O, Tschopp J. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell. 2003;114:181–190. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00521-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen G, Goeddel DV. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science. 2002;296:1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ea CK, Deng L, Xia ZP, Pineda G, Chen ZJ. Activation of IKK by TNFalpha requires site-specific ubiquitination of RIP1 and polyubiquitin binding by NEMO. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanayama A, et al. TAB2 and TAB3 activate the NF-kappaB pathway through binding to polyubiquitin chains. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li HX, Kobayashi M, Blonska M, You Y, Lin X. Ubiquitination of RIP is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced NF-kappa B activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13636–13643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600620200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang C, et al. TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature. 2001;412:346–351. doi: 10.1038/35085597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertrand MJM, et al. cIAP1 and cIAP2 facilitate cancer cell survival by functioning as E3 ligases that promote RIP1 ubiquitination. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geserick P, et al. Cellular IAPs inhibit a cryptic CD95-induced cell death by limiting RIP1 kinase recruitment. J. Cell Biol. 2009;187:1037–1054. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovalenko A, et al. The tumour suppressor CYLD negatively regulates NF-kappa B signalling by deubiquitination. Nature. 2003;424:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nature01802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Du FH, Wang XD. TNF-alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell. 2008;133:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickens LS, et al. A death effector domain chain DISC model reveals a crucial role for caspase-8 chain assembly in mediating apoptotic cell death. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:291–305. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He SD, et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;137:1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai ZY, et al. Plasma membrane translocation of trimerized MLKL protein is required for TNF-induced necroptosis (vol 16, pg 55, 2014) Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:200–200. doi: 10.1038/ncb2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, et al. Translocation of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein to plasma membrane leads to necrotic cell death. Cell Res. 2014;24:105–121. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dondelinger Y, et al. MLKL compromises plasma membrane integrity by binding to phosphatidylinositol phosphates. Cell Rep. 2014;7:971–981. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su LJ, et al. A plug release mechanism for membrane permeation by MLKL. Structure. 2014;22:1489–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang HY, et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol. Cell. 2014;54:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelliher MA, et al. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappa B signal. Immunity. 1998;8:297–303. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80535-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowling JP, Nair A, Zhang J. A novel function of RIP1 in postnatal development and immune homeostasis by protecting against RIP3-dependent necroptosis and FADD-mediated apoptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015;3:12. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2015.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaiser WJ, et al. RIP1 suppresses innate immune necrotic as well as apoptotic cell death during mammalian parturition. Proc Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:7753–7758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401857111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillon CP, et al. RIPK1 blocks early postnatal lethality mediated by caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell. 2014;157:1189–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rickard JA, et al. RIPK1 regulates RIPK3-MLKL-driven systemic inflammation and emergency hematopoiesis. Cell. 2014;157:1175–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi N, et al. RIPK1 ensures intestinal homeostasis by protecting the epithelium against apoptosis. Nature. 2014;513:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nature13706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dannappel M, et al. RIPK1 maintains epithelial homeostasis by inhibiting apoptosis and necroptosis. Nature. 2014;513:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature13608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang HB, et al. Functional complementation between FADD and RIP1 in embryos and lymphocytes. Nature. 2011;471:373-+. doi: 10.1038/nature09878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newton K, et al. Activity of protein kinase RIPK3 determines whether cells die by necroptosis or apoptosis. Science. 2014;343:1357–1360. doi: 10.1126/science.1249361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanger BZ, Leder P, Lee TH, Kim E, Seed B. Rip-a novel protein containing a death domain that interacts with Fas/Apo-1 (Cd95) in yeast and causes. Cell Death Cell. 1995;81:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christofferson DE, Li Y, Yuan JY. Control of life-or-death decisions by RIP1 kinase. Annu Rev. Physiol. 2014;76:129–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degterev A, et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:313–321. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dondelinger Y, et al. NF-kappa B-independent role of IKK alpha/IKK beta in preventing RIPK1 kinase-dependent apoptotic and necroptotic cell death during TNF signaling. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geng J. F., et al. Regulation of RIPK1 activation by TAK1-mediated phosphorylation dictates apoptosis and necroptosis. Nat. Commun.8, 359 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Polykratis A, et al. Cutting edge: RIPK1 kinase inactive mice are viable and protected from TNF-induced necroptosis in vivo. J. Immunol. 2014;193:1539–1543. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berger SB, et al. Cutting edge: RIP1 kinase activity is dispensable for normal development but is a key regulator of inflammation in SHARPIN-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 2014;192:5476–5480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li JX, et al. The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell. 2012;150:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin J, et al. RIPK1 counteracts ZBP1-mediated necroptosis to inhibit inflammation. Nature. 2016;540:124-+. doi: 10.1038/nature20558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newton K, et al. RIPK1 inhibits ZBP1-driven necroptosis during development. Nature. 2016;540:129-+. doi: 10.1038/nature20559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng HY, et al. Death-domain dimerization-mediated activation of RIPK1 controls necroptosis and RIPK1-dependent apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E2001–E2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1722013115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Donnell MA, Legarda-Addison D, Skountzos P, Yeh WC, Ting AT. Ubiquitination of RIP1 regulates an NF-kappaB-independent cell-death switch in TNF signaling. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tenev T, et al. The ripoptosome, a signaling platform that assembles in response to genotoxic stress and loss of IAPs. Mol. Cell. 2011;43:432–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wertz IE, et al. Phosphorylation and linear ubiquitin direct A20 inhibition of inflammation. Nature. 2015;528:370-+. doi: 10.1038/nature16165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang XX, et al. MLKL and FADD are critical for suppressing progressive lymphoproliferative disease and activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell Rep. 2016;16:3247–3259. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dillon CP, et al. Survival function of the FADD-CASPASE-8-cFLIP(L) complex. Cell Rep. 2012;1:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alvarez-Diaz S, et al. The pseudokinase MLKL and the kinase RIPK3 have distinct roles in autoimmune disease caused by loss of death-receptor-induced apoptosis. Immunity. 2016;45:513–526. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Justus SJ, Ting AT. Cloaked in ubiquitin, a killer hides in plain sight: the molecular regulation of RIPK1. Immunol. Rev. 2015;266:145–160. doi: 10.1111/imr.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinlich R, Green DR. The two faces of receptor interacting protein kinase-1. Mol. cell. 2014;56:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelliher MA, et al. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal. Immunity. 1998;8:297–303. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80535-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beg AA, Sha WC, Bronson RT, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-kappa B. Nature. 1995;376:167–170. doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Q, Van Antwerp D, Mercurio F, Lee KF, Verma IM. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IkappaB kinase 2 gene. Science. 1999;284:321–325. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudolph D, et al. Severe liver degeneration and lack of NF-kappaB activation in NEMO/IKKgamma-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:854–862. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu C, et al. Embryonic lethality and host immunity of rela-deficient mice are mediated by both apoptosis and necroptosis. J. Immunol. 2018;200:271–285. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vlantis K, et al. NEMO prevents RIP kinase 1-mediated epithelial cell death and chronic intestinal inflammation by NF-kappaB-dependent and -independent functions. Immunity. 2016;44:553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cuchet-Lourenço Delphine, Eletto Davide, Wu Changxin, Plagnol Vincent, Papapietro Olivier, Curtis James, Ceron-Gutierrez Lourdes, Bacon Chris M., Hackett Scott, Alsaleem Badr, Maes Mailis, Gaspar Miguel, Alisaac Ali, Goss Emma, AlIdrissi Eman, Siegmund Daniela, Wajant Harald, Kumararatne Dinakantha, AlZahrani Mofareh S., Arkwright Peter D., Abinun Mario, Doffinger Rainer, Nejentsev Sergey. Biallelic RIPK1 mutations in humans cause severe immunodeficiency, arthritis, and intestinal inflammation. Science. 2018;361(6404):810–813. doi: 10.1126/science.aar2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang J, et al. Type I interferons triggered through the toll-like receptor 3-TRIF pathway control coxsackievirus A16 infection in young mice. J. Virol. 2015;89:10860–10867. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01627-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data presented in this study are available within the figures and its Supplementary Information file. The source data underlying Figs. 3a, 4a, e, 5b, f, g, 6d, 7e, f and Supplementary Figs 1b, 2e, f are provided as a Source Data file. Other data that support the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.