Abstract

Structural and vibrational properties of free base, cationic and hydrochloride species derived from both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers of antihistaminic promethazine (PTZ) agent have been theoretically evaluated in gas phase and in aqueous solution by using the hybrid B3LYP/6-31G* calculations. The initial structures of S(-) and R(+) enantiomers of hydrochloride PTZ were those polymorphic forms 1 and 2 experimentally determined by X-ray diffraction. Here, all structures in aqueous solution were optimized at the same level of theory by using the polarized continuum (PCM) and the universal solvation model. As was experimentally reported, variations in the unit cell lead to slight energy, density, and melting point differences between the two forms but, this behavior is not carried through in isotropic condition, like in solution with non-chiral solvents. Hence, the N–C distances, Mulliken, atomic natural population (NPA) and Merz-Kollman (MK) charges, bond orders, stabilization and solvation energies, frontier orbitals, some descriptors and their topological properties were compared with the antihistaminic cyclizine agent. The frontier orbitals studies show that the free base species of both forms in solution are more reactive than cyclizine. Higher electrophilicity indexes are observed in the cationic and hydrochloride species of PTZ than cyclizine while the cationic species of cyclizine have higher nucleophilicity index than both species of PTZ. The presences of bands attributed to cationic species of both enantiomers are clearly supported by the infrared and Raman spectra in the solid phase. The expected 114, 117 and 120 vibration normal modes for the free base, cationic and hydrochloride species of both forms were completely assigned and the force constants reported. Reasonable concordances among the predicted infrared, Raman, UV-Vis and Electronic Circular Dichroism (ECD) with the corresponding experimental ones were found.

Keywords: Computer science, Theoretical chemistry, Electronic, Structural properties, DFT calculations, Promethazine, Descriptor properties

1. Introduction

Species containing in their structures the N–CH3 group presenting a wide range of pharmacological and medicinal properties such as tropane alkaloids whose known biologics effects can cause from pain cure up to addiction [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. However, there are another groups of species that also contain that group but that present other different biological properties such as, diphenhydramine and cyclizine, where both species are broadly used in pharmacology as antihistaminic agents [8, 9]. Nevertheless, the most remarkable differences among the free base, cationic and hydrochloride species of those two antihistaminic agents are that in the species derived from diphenhydramine their two N–CH3 groups are not linked to rings while in the cyclizine species those groups are linked to piperazine rings [8, 9]. Previous theoretical studies on structures and properties of alkaloids have evidenced that when the N–CH3 group is linked to fused rings as in scopolamine, cocaine and tropane some properties are slightly different from those where the N–CH3 group is linked to only one ring as in heroin and morphine [1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7]. Besides, the stabilities of these series of alkaloids are strongly dependent on the N–C distances [6, 7]. On the other hand, the reactivities predicted for the three species of diphenhydramine practically are the same than that reported for cationic form of cocaine [3, 7] while lowest solvation energy value was observed for the free base of cyclizine, as compared with the corresponding to tropane alkaloids [9]. Evidently, there is an important connection between the quantity of N–CH3 groups and the type of groups linked to N atom, that is, >N- tertiary or >N< quaternary. Consequently, the biological activities and effects of these types of species on human health are obviously resulted of their nature and structural, electronic and topological properties. Hence, the interest to study another antihistaminic agent, in this case promethazine (PTZ) [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33], which has two N–CH3 groups (as diphenhydramine) linked to a chiral carbon and, as a consequence two enantiomeric S and R structures are expected for their three free base, cationic and hydrochloride species. PTZ hydrochloride is a drug used to treatment of nausea, vomiting, and dizziness associated with motion sickness and, besides possesses anti-pruritic, anti-allergic, anticholinergic, antihistaminic, central nervous system depressant, and with general anaesthetics effects. Their metabolic and clinic effects were studied from long time together with their side effects [13, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33]. Some known chemical names of promethazine are proazamine, diphergan, phenargan or phensedyl while its IUPAC name is N,N-dimethyl-1-phenothiazin-10-ylpropan-2-amine. PTZ has structurally two >N–CH3 groups, three fused six members rings (two phenyl and one phenothiazine) and a chiral carbon and where experimentally Borodi et al [19] have determined by X-ray diffraction two enantiomeric disordered structures of promethazine hydrochloride but, so far, the structural properties and vibrational assignments of those three species of PTZ were not published. The vibrational analyses of the three species of PTZ are actually of great interest and significance taking into account that the infrared, Raman and SERS spectroscopies are practically the most used spectroscopic techniques to identify these species in different systems and preparations [10, 12, 15, 17, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. Hence, the aims of this work are: (i) to study the structural, electronic, topological and vibrational properties of free base, cationic and hydrochloride species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ, (ii) to find some correlations between their properties that can explain the differences between its biological properties, as compared with alkaloids and other antihistaminic agents, (iii) to perform the complete vibrational assignments of those three species of PTZ because, so far, these are not reported. In accordance to previous studies, the infrared spectra of many hydrochloride species show clearly the presence of their cationic forms in the solid phase and in aqueous solution [1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8]. To achieve those purposes, the theoretical structures of free base, cationic and hydrochloride species of both S(-) and R(+)-PTZ enantiomers were optimized in gas phase and in aqueous solution by using the hybrid B3LYP/6-31G* method [34, 35] while experimental infrared and Raman spectra available from the literature were used to perform the vibrational analyses [17, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. The studies in solution were performed with the integral equation formalism variant polarised continuum method (IEFPCM) because it scheme contemplates the solvent effects while the solvation energies were computed with the universal solvation model [36, 37, 38]. Hence, for those three S(-) and R(+)-PTZ species, atomic charges, molecular electrostatic potential, bond orders, frontier orbitals and topological properties were calculated together with the harmonic force fields by using the scaled quantum mechanical force field (SQMFF) and transferable scaling factors [39, 40]. Then, the complete assignments for the three species were performed by using the corresponding force fields, internal normal coordinates and the experimental available vibrational spectra of PTZ hydrochloride [41] together with the Molvib program [42]. Taking into account the wide range of biological activities that presents PTZ, the reactivities and behaviours of those three S(-) and R(+)-PTZ species were predicted in both media by using the frontier orbitals [43, 44] and global descriptors [45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53]. Finally, the predicted properties of both enantiomeric series of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ were evaluated and then compared with the available data reported for alkaloids, diphenhydramine and cyclizine [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

2. Methodology

2.1. Ab-initio calculations

The initial structure of S(-) enantiomer of PTZ hydrochloride was that experimental polymorphic form 1 determined by X-ray diffraction by Borodi et al [19] and taken from the available CIF file. The corresponding cationic and free base species were modelled respectively by using the GaussView program [54] where the Cl atom was first removed from that initial structure of PTZ hydrochloride and, later, the H atom. A similar procedure was employed to obtain the three species of R(+) enantiomer but in this case the structures were built from that experimental polymorphic form 2 determined by X-ray diffraction by Borodi et al [19]. The Revision A.02 of Gaussian program was employed to optimize those six species in both media [55] by using the hybrid B3LYP/6-31G* method [34, 35]. In solution, the three species were optimized by using PCM and SMD calculations [36, 37, 38] while their volumes changes were evaluated with the Moldraw program [56]. In Fig. 1 can be seen the six S(-) and R(+)-PTZ structures as free base, cationic and hydrochloride together with the atoms labelling and the identifications of their three rings. The solvation energies corrected by zero point vibrational energy (ZPVE) were computed for all species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ with the universal solvation model [36, 37, 38]. Besides, atomic natural population (NPA), Mulliken and Merz-Kollman (MK) charges [57], molecular electrostatic potentials, bond orders and topological properties were calculated by using the NBO program [58] and with the Bader's theory of atoms in molecules (AIM) by using AIM2000 program [59, 60]. On the other hand, the evaluation of reactivities and behaviours of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ species were performed calculating the gap values [43, 44] and some useful and known global descriptors with the frontier orbitals [45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53]. The harmonic force fields and force constants in gas phase and in aqueous solution were computed at the B3LYP/6-31G* level by using the normal internal coordinates and transferable scaling factors with the scaled quantum mechanical force field (SQMFF) and the Molvib program [39, 40, 42]. Here, the predicted Raman activities for all species were corrected to intensities by using recommended equations [61, 62] while the scale factors used were those reported for the B3LYP/6-31G* method. At this point, it is necessary to clarify that all studied properties were computed for six S(-) and R(+)-PTZ species by using only the B3LYP/6-31G* level because they are compared with properties reported at the same level of theory for other species containing N–CH3 groups, such as alkaloids, diphenhydramine and cyclizine [1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9].

Fig. 1.

Theoretical molecular structures of free base, cationic and hydrocloride species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers of promethazine.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Properties of species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ in both media

The structural studies in solution of these species are of great interest because the >N–CH3 group can present fast N-methyl inversion in this medium, as suggested by Lazni et al [63]. Here, in Table 1 are summarized calculated total uncorrected and corrected by ZPVE energies, dipole moments and volumes (V) of three species of both enantiomers S(-) and R(+)-PTZ in gas and aqueous solution phases by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method. Analyzing deeply the results, it is observed that the total energy values corrected by ZPVE decrease for all species in both media while the dipole moment and volume values increase in solution, as expected because these species are possibly hydrated in solution. The exception is observed only for the cationic form of S(-)-PTZ because the E and V values decrease in solution. Here, the imaginary frequencies obtained for that species could justify clearly these differences. Note that the cationic species of both enantiomers have higher dipole moments in solution while the hydrochloride forms present the higher volumes in both media having the S(-) species slightly the higher values in the two media. In Table 2 can be observed corrected and uncorrected solvation energies by the total non-electrostatic terms and by zero point vibrational energy (ZPVE) of free base, cationic and hydrochloride species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method. The variations observed experimentally in the unit cell lead to small displacements of the molecules in the crystal structures and, consequently, to slight energy, density, and melting point differences between the forms. Note that these obtained values are closer to those observed in the study of interaction of gelatin with promethazine hydrochloride [64]. These values are compared in the same table with morphine, cocaine, scopolamine, heroin and tropane alkaloids and with cyclizine [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9]. In particular, due to the imaginary frequencies predicted for the cationic form of cyclizine in solution the value for cyclizine was obtained by using B3LYP/6-31+G* calculations while for S(-)-PTZ in solution the value of -14,48 kJ/mol was obtained directly from Table 1. The ΔGc values for the three species of tropane were calculated in this work. Fig. 2 shows clearly the variations of ΔGc for all compared species by using the solvation model [38]. In general, it is observed that all cationic species have more negative values while the free bases the less negative values. The cationic forms of morphine, scopolamine and heroin have the most negative values while the S(-) form of PTZ the most low ΔGc value. Probably, this resulted change if other basis set is used. Interesting results are observed for cyclizine (-244,36 kJ/mol) and tropane (-244,33 kJ/mol) because their cationic forms have practically the same values. In both species, the N–CH3 groups are linked to rings, in cyclizine to piperazine ring while in tropane a two fused piperidine and pyrrolidine rings. The heroin hydrochloride species present the most negative ΔGc value while the R(+)-PTZ the lower value. On the other hand, the free base of heroin presents the most negative ΔGc value while the tropane species the lowest value. Evidently, the acetyl groups in heroin increase the solvation energies of their three species, as compared with morphine. Obviously, these comparisons show easily why the hydrochloride species are highly used in pharmacology, as compared with their free base and cationic ones. Besides, the hydrochloride species in solution are in their cationic forms and show clearly high solubility in this medium. Evidently, the solubility limits visibly the drug absorption, as mentioned by Bohloko studying the formulation of an intranasal dosage form for cyclizine hydrochloride [65].

Table 1.

Calculated total energies (E), dipole moments (μ) and volumes (V) of three species of S(-) and R(+)-promethazine in gas and aqueous solution phases.

| B3LYP/6-31G* Method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | E (Hartrees) | ZPVE | μ (D) | V (Å3) |

| S(-)-Free base | ||||

| GAS | -1167.5298 | -1167.1923 | 2.18 | 312.7 |

| PCM |

-1167.5383 |

-1167.2000 |

3.75 |

314.2 |

| S(-)-Cationic | ||||

| GAS | -1167.9143 | -1167.5615 | 14.62 | 316.3 |

|

PCM# |

-1167.9121 |

-1167.5588 |

15.20 |

315.1 |

| S(-)-Hydrochloride | ||||

| GAS | -1628.3493 | -1627.9992 | 9.33 | 342.1 |

| PCM |

-1628.3849 |

-1628.0312 |

14.16 |

342.8 |

| R(+)-Free base | ||||

| GAS | -1167.5263 | -1167.1907 | 1.92 | 312.3 |

| PCM |

-1167.5277 |

-1167.1894 |

3.03 |

312.2 |

| R(+)-Cationic | ||||

| GAS | -1167.9127 | -1167.5599 | 14.77 | 315.9 |

| PCM |

-1168.0075 |

-1167.6532 |

19.73 |

319.0 |

| R(+)-Hydrochloride | ||||

| GAS | -1628.3509 | -1628.0002 | 7.50 | 338.6 |

| PCM | -1628.3836 | -1627.9920 | 11.72 | 341.4 |

Imaginary frequencies.

Table 2.

Corrected and uncorrected solvation energies by the total non-electrostatic terms and by zero point vibrational energy (ZPVE) of three species of S(-) and R(+)-promethazine by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method compared with other similar species.

| B3LYP/6-31G* methoda | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvation energy (kJ/mol) | |||

| Condition | ΔGun# | ΔGne | ΔGc |

| Free base | |||

| S(-)-Promethazinea | -20.19 | 15.88 | -36.07 |

| R(+)-Promethazinea | -3.41 | 14.46 | -17.87 |

| Cyclizineb | -23.60 | 5.93 | -29.53 |

| Morphinec | -47.74 | 13.17 | -60.91 |

| Cocained | -42.75 | 28.51 | -71.26 |

| Scopolaminee | -56.66 | 18.81 | -75.47 |

| Heroinf | -59.54 | 29.13 | -88.67 |

| Tropanea,g |

-11.80 |

0.75 |

-12.55 |

| Cationic | |||

| S(-)-Promethazinea | -7.08 | 7.40 | -14.48 |

| R(+)-Promethazinea | -255.22 | 7.59 | -262.81 |

| Cyclizineb,# | -238.43 | 5.93 | -244.36 |

| Morphinec | -282.23 | 26.96 | -309.19 |

| Cocained | -216.66 | 38.58 | -255.24 |

| Scopolaminee | -279.87 | 30.47 | -310.34 |

| Heroinf | -280.13 | 43.01 | -323.14 |

| Tropanea,g |

-228.99 |

15.34 |

-244.33 |

| Hydrochloride | |||

| S(-)-Promethazinea | -101.25 | 30.81 | -70.44 |

| R(+)-Promethazinea | -21.51 | 30.51 | -52.02 |

| Cyclizineb | -81.57 | 23.49 | -105.06 |

| Morphinec | -118.82 | 25.92 | -144.74 |

| Cocained | -99.94 | 38.20 | -138.14 |

| Scopolaminee | -95.19 | 27.55 | -122.74 |

| Heroinf | -118.56 | 43.38 | -161.94 |

| Tropanea,g | -72.13 | 15.05 | -87.18 |

ΔGun# = uncorrected solvation energy: defined as the difference between the total energies in aqueous solutions and the values in gas phase. ΔGun = Solvation energy (kJ/mol) corrected by ZPVE.

ΔGne = total non electrostatic terms: due to the cavitation, dispersion and repulsion energies.

ΔGc = corrected solvation energies: defined as the difference between the uncorrected and non-electrostatic solvation energies.

This work.

From Ref [9].

From Ref [1].

From Ref [3].

From Ref [7].

From Ref [5].

From Ref [2].

Cation cyclizine: 6-31+G*.

Fig. 2.

Corrected solvation energies of free base, cationic and hydrocloride species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers of promethazine by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method.

3.2. Geometries of species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ in both media

Calculated geometrical parameters for three species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ in both media are compared with the corresponding experimental polymorphic forms 1 and 2 [19] in Tables 3 and 4, respectively by using the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values. Despite theoretical B3LYP/6-31G* calculations show visibly overestimated values, as compared with the corresponding experimental ones, the results for all species of S(-)-PTZ forms show very good correlations for bond lengths (0.020–0.012 Å) but the three species of R(+)-PTZ evidence the better correlations for bond (1.7–1.3°) and dihedral angles (6.1–3.7°) than the S(-) ones. On the other hand, the higher differences in dihedral angles are predicted for the three species of S(-) form (176.1–137.9°), as can be seen in Table 3. Here, it is necessary to remember that those two polymorphic conformations found by Borodi et al [19] are experimentally the same where the two forms are present in the unit cell but our theoretical calculations show slight differences in the dihedral angles of both S(-) and R(+)-PTZ forms. Thus, the calculated bonds N2–C6 and N2–C7 lengths of phenothiazine rings belong to the three species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers are practically predicted with same values but different from the bond N2–C5 lengths of side chain. In the same way, the calculated S1–C9 bonds of phenothiazine rings are approximately the same than the S1–C10 bonds while the predicted N3–C11 bonds are practically the same than the N3–C12 bonds. The predicted values for both pairs bonds are different from the corresponding experimental ones.

Table 3.

Comparison of calculated geometrical parameters for three species of S(-)-promethazine in both media with the corresponding experimental ones.

| B3LYP/6-31G* Methoda |

Form 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Free base |

Cation |

Hydrochloride |

Experimentalb | ||

| Gas | PCM | Gas | Gas | PCM | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | ||||||

| S1–C9 | 1.783 | 1.786 | 1.786 | 1.783 | 1.786 | 1.772 |

| S1–C10 | 1.783 | 1.786 | 1.785 | 1.784 | 1.786 | 1.781 |

| N2–C5 | 1.464 | 1.471 | 1.445 | 1.457 | 1.465 | 1.435 |

| N2–C6 | 1.416 | 1.419 | 1.427 | 1.420 | 1.420 | 1.422 |

| N2–C7 | 1.416 | 1.418 | 1.424 | 1.420 | 1.419 | 1.418 |

| C6–C9 | 1.406 | 1.409 | 1.404 | 1.407 | 1.408 | 1.379 |

| C7–C10 | 1.406 | 1.409 | 1.406 | 1.407 | 1.409 | 1.389 |

| C4–C5 | 1.553 | 1.552 | 1.547 | 1.545 | 1.543 | 1.545 |

| N3–C4 | 1.472 | 1.482 | 1.550 | 1.511 | 1.525 | 1.513 |

| N3–C11 | 1.454 | 1.463 | 1.505 | 1.485 | 1.495 | 1.502 |

| N3–C12 | 1.456 | 1.465 | 1.505 | 1.484 | 1.495 | 1.491 |

| C6–C13 | 1.401 | 1.405 | 1.399 | 1.402 | 1.404 | 1.398 |

| C9–C15 | 1.392 | 1.395 | 1.395 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.394 |

| C13–C17 | 1.393 | 1.396 | 1.396 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.396 |

| C15–C19 | 1.393 | 1.396 | 1.395 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.392 |

| C17–C19 | 1.391 | 1.394 | 1.394 | 1.393 | 1.395 | 1.366 |

| C7–C14 | 1.401 | 1.404 | 1.400 | 1.402 | 1.404 | 1.402 |

| C14–C18 | 1.393 | 1.396 | 1.397 | 1.396 | 1.396 | 1.387 |

| C16–C10 | 1.392 | 1.395 | 1.395 | 1.394 | 1.395 | 1.394 |

| C16–C20 | 1.393 | 1.396 | 1.395 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.382 |

| C18–C20 | 1.391 | 1.395 | 1.394 | 1.393 | 1.394 | 1.379 |

|

RMSDb |

0.020 |

0.019 |

0.014 |

0.012 |

0.013 |

|

| Bond angles (°) | ||||||

| C9–S1–C10 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 98.2 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 96.4 |

| C6–C9–S1 | 118.6 | 118.5 | 118.8 | 118.7 | 118.6 | 119.0 |

| C7–C10–S1 | 118.6 | 118.5 | 118.7 | 118.6 | 118.6 | 117.9 |

| C5–N2–C6 | 119.5 | 118.7 | 120.2 | 119.5 | 119.0 | 118.9 |

| C5–N2–C7 | 119.3 | 119.2 | 119.8 | 119.6 | 119.3 | 119.1 |

| C6–N2–C7 | 117.5 | 117.0 | 118.3 | 117.9 | 117.7 | 115.6 |

| N2–C5–C4 | 112.7 | 113.2 | 108.6 | 111.3 | 110.6 | 108.9 |

| C5–C4–N3 | 113.1 | 113.0 | 111.8 | 111.6 | 111.1 | 106.9 |

| C4–N3–C11 | 114.3 | 112.4 | 113.1 | 114.3 | 113.2 | 111.7 |

| C4–N3–C12 | 116.2 | 114.1 | 114.4 | 115.8 | 114.9 | 112.1 |

| C11–N3–C12 | 111.9 | 109.8 | 111.2 | 111.2 | 110.7 | 111.4 |

| N2–C7–C14 | 122.5 | 122.5 | 122.6 | 122.5 | 122.5 | 122.4 |

| N2–C6–C13 | 122.6 | 122.6 | 122.5 | 122.6 | 122.5 | 121.9 |

| S1–C10–C16 | 120.4 | 120.3 | 120.8 | 120.6 | 120.3 | 120.0 |

| S1–C9–C15 | 120.4 | 120.3 | 120.7 | 120.5 | 120.3 | 120.0 |

|

RMSDb |

2.4 |

2.1 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

1.6 |

|

| Dihedral angles (°) | ||||||

| C11–N3–C4–C5 | 75.9 | 72.8 | 75.7 | 71.0 | 73.8 | 167.0 |

| C12–N3–C4–C5 | -56.6 | -53.1 | -53.0 | -60.3 | -54.9 | -67.0 |

| N3–C4–C5–N2 | -168.3 | -167.7 | -165.4 | -169.6 | -165.2 | 175.4 |

| C4–C5–N2–C6 | -137.3 | -142.2 | -127.8 | -135.3 | -136.5 | -68.6 |

| C4–C5–N2–C7 | 63.8 | 63.4 | 66.3 | 64.2 | 66.2 | 140.3 |

| C14–C7–N2–C6 | -135.8 | -134.5 | -134.5 | -135.2 | -136.0 | -129.1 |

| C15–C9–S1–C10- | -144.8 | -144.5 | -144.2 | -144.7 | -144.8 | -139.1 |

| C8–C4–C5–N2 | 65.1 | 66.0 | 69.7 | 64.9 | 70.4 | -65.9 |

| RMSDb | 138.9 | 139.5 | 137.9 | 176.1 | 223.0 | |

Table 4.

Comparison of calculated geometrical parameters for three species of R(+)-promethazine in both media with the corresponding experimental ones.

| B3LYP/6-31G* Methoda |

Form 2 Experimentalb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Free base |

Cation |

Hydrochloride |

||||

| Gas | PCM | Gas | PCM | Gas | PCM | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | |||||||

| S1–C9 | 1.783 | 1.785 | 1.786 | 1.785 | 1.784 | 1.785 | 1.772 |

| S1–C10 | 1.783 | 1.786 | 1.785 | 1.786 | 1.782 | 1.785 | 1.781 |

| N2–C5 | 1.464 | 1.470 | 1.443 | 1.462 | 1.457 | 1.464 | 1.435 |

| N2–C6 | 1.418 | 1.418 | 1.427 | 1.420 | 1.423 | 1.421 | 1.422 |

| N2–C7 | 1.417 | 1.418 | 1.425 | 1.420 | 1.418 | 1.421 | 1.418 |

| C6–C9 | 1.408 | 1.409 | 1.404 | 1.408 | 1.407 | 1.409 | 1.379 |

| C7–C10 | 1.408 | 1.409 | 1.406 | 1.408 | 1.409 | 1.409 | 1.389 |

| C4–C5 | 1.551 | 1.549 | 1.554 | 1.547 | 1.552 | 1.548 | 1.545 |

| N3–C4 | 1.479 | 1.486 | 1.551 | 1.533 | 1.520 | 1.527 | 1.513 |

| N3–C11 | 1.460 | 1.468 | 1.508 | 1.502 | 1.487 | 1.496 | 1.502 |

| N3–C12 | 1.460 | 1.468 | 1.508 | 1.503 | 1.486 | 1.496 | 1.491 |

| C6–C13 | 1.403 | 1.404 | 1.399 | 1.403 | 1.402 | 1.404 | 1.398 |

| C9–C15 | 1.394 | 1.395 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.395 | 1.395 | 1.394 |

| C13–C17 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.396 | 1.396 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.396 |

| C15–C19 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.395 | 1.395 | 1.392 |

| C17–C19 | 1.393 | 1.395 | 1.394 | 1.395 | 1.393 | 1.394 | 1.366 |

| C7–C14 | 1.403 | 1.404 | 1.400 | 1.403 | 1.403 | 1.403 | 1.402 |

| C14–C18 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.397 | 1.396 | 1.396 | 1.396 | 1.540 |

| C16–C10 | 1.394 | 1.395 | 1.395 | 1.395 | 1.394 | 1.395 | 1.540 |

| C16–C20 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.396 | 1.396 | 1.395 | 1.396 | 1.540 |

| C18–C20 | 1.393 | 1.395 | 1.394 | 1.394 | 1.393 | 1.394 | 1.325 |

|

RMSDb |

0.060 |

0.059 |

0.058 |

0.015 |

0.058 |

0.058 |

|

| Bond angles (°) | |||||||

| C9–S1–C10 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 98.2 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 96.4 |

| C6–C9–S1 | 118.6 | 118.5 | 118.7 | 118.6 | 118.8 | 118.7 | 119.0 |

| C7–C10–S1 | 118.6 | 118.4 | 118.7 | 118.6 | 118.7 | 118.7 | 117.9 |

| C5–N2–C6 | 119.2 | 119.3 | 120.0 | 118.9 | 119.1 | 118.7 | 118.9 |

| C5–N2–C7 | 119.4 | 119.1 | 119.7 | 119.2 | 119.4 | 119.1 | 119.1 |

| C6–N2–C7 | 117.6 | 117.3 | 118.2 | 117.8 | 118.0 | 117.6 | 115.6 |

| N2–C5–C4 | 113.1 | 112.4 | 109.5 | 111.2 | 110.9 | 111.2 | 108.9 |

| C5–C4–N3 | 107.7 | 109.1 | 109.4 | 108.2 | 108.6 | 108.6 | 106.9 |

| C4–N3–C11 | 114.8 | 111.9 | 113.6 | 113.5 | 114.5 | 113.5 | 112.1 |

| C4–N3–C12 | 111.9 | 110.5 | 112.8 | 112.8 | 113.2 | 112.7 | 111.7 |

| C11–N3–C12 | 108.9 | 107.2 | 109.2 | 108.8 | 109.6 | 108.9 | 111.4 |

| N2–C7–C14 | 122.5 | 122.5 | 122.7 | 122.5 | 122.6 | 122.5 | 122.4 |

| N2–C6–C13 | 122.5 | 122.6 | 122.6 | 122.5 | 122.5 | 122.5 | 121.9 |

| S1–C10–C16 | 120.4 | 120.3 | 120.8 | 120.3 | 120.5 | 120.2 | 121.0 |

| S1–C9–C15 | 120.4 | 120.3 | 120.8 | 120.3 | 120.3 | 120.1 | 120.0 |

|

RMSDb |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

|

| Dihedral angles (°) | |||||||

| C11–N3–C4–C5 | 157.1 | 165.9 | 165.5 | 164.2 | 160.7 | 163.5 | 167.0 |

| C12–N3–C4–C5 | -77.8 | -74.4 | -69.3 | -71.2 | -72.5 | -71.9 | -67.0 |

| N3–C4–C5–N2 | 172.2 | 165.7 | 170.5 | 171.6 | 171.4 | 166.4 | 175.4 |

| C4–C5–N2–C6 | 137.0 | 136.7 | 130.3 | 137.3 | 133.5 | 137.6 | 139.9 |

| C4–C5–N2–C7 | -64.6 | -66.7 | -65.9 | -65.5 | -67.5 | -66.7 | -69.0 |

| C14–C7–N2–C6 | 135.9 | 135.5 | 134.3 | 136.0 | 136.5 | 136.0 | 131.7 |

| C15–C9–S1–C10- | 144.6 | 144.1 | 144.1 | 144.7 | 144.7 | 144.8 | 140.1 |

| C8–C4–C5–N2 | -64.5 | -71.0 | -65.8 | -65.7 | -65.9 | -70.7 | -62.7 |

| RMSDb | 6.1 | 5.8 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 5.4 | |

Another interesting comparisons are observed in the average bond N–C lengths of the N–CH3 groups belonging to the three species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ with those observed for cyclizine, morphine, heroin, cocaine, scopolamine and tropane where the results in gas phase and in aqueous solution by using B3LYP/6-31G* calculations can be seen in Table 5. Here, due to the presence of two N–CH3 groups the average of N–C distances between both groups were considered. In Fig. 3 are easily observed the behaviours of N–C distances of all compared species in both media. In gas phase, the comparisons between the free base and cationic species show that cationic form of cyclizine has the lowest value (1.453 Å) while the highest value is observed in the cationic species of R(+)-PTZ (1.508 Å). In solution, it is observed that the free base species have low values and different from the hydrochloride ones. Evidently, the presence of charged cationic species and electronegative Cl atoms in all hydrochloride species produce increase in the N–C distances. The tropane hydrochloride has the shorter value while the species corresponding to R(+)-PTZ the higher value.

Table 5.

Bond lengths observed between the N and C atoms of the N–CH3 bonds belonging to the three S(-) and R(+)-promethazine species in gas phase and in aqueous solution by using B3LYP/6-31G* calculations.

| N–CH3 bonds () | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Gas phase |

Aqueous solution |

||||

| Free base | Cationic | Hydrobromide | Free base | Cationic | Hydrobromide | |

| R(+)-promethazineγ | 1.460 | 1.508 | 1.487 | 1.468 | 1.501 | 1.496 |

| S(-)-Promethazineγ | 1.455 | 1.505 | 1.485 | 1.464 | # | 1.495 |

| Cyclizine | 1.453 | 1.453 | # | 1.459 | # | 1.489 |

| Scopolamine | 1.462 | 1.492 | 1.491 | 1.466 | 1.491 | 1.493 |

| Heroin | 1.453 | 1.501 | 1.483 | 1.460 | 1.498 | 1.492 |

| Morphine | 1.453 | 1.500 | 1.483 | 1.460 | 1.497 | 1.493 |

| Cocaine | 1.459 | 1.493 | 1.487 | 1.467 | 1.492 | 1.494 |

| Tropane | 1.458 | 1.496 | 1.478 | 1.467 | 1.491 | 1.486 |

Imaginary frequencies.

average.

Fig. 3.

Calculated N–C distances corresponding to N–CH3 groups of free base, cationic and hydrocloride species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers of promethazine in both media by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method.

3.3. Atomic charges, molecular electrostatic potentials and bond orders

Mulliken, Merz-Kollman (MK) and atomic natural population (NPA) charges, molecular electrostatic potentials (MEP) and bond orders (BO), expressed as Wiberg indexes were calculated for the three forms of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ in gas phase and in aqueous solution by using B3LYP/6-31G* calculations. The resulted only for the S1, N2, N3, C8, C11 and C12 atoms can be seen in Table 6 because these atoms present the higher variations in all species while the behaviours of MK charges on these atoms are represented in Fig. 4. Analyzing first the MK charges for the free base species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ we observed from Fig. 4 that: (i) the MK charges on the N2, C8 and C11 atoms of all free base species undergoes important changes, presenting the highest change on N2 of free base of R(+)-PTZ in solution and (ii) the charges on the S1, N3 and C12 atoms of all species in both media have practically the same values. In the cationic species, the lower MK charges values are observed on those five atoms of S(-)-PTZ in gas phase while on N2 atoms of R(+) species in the two media are observed the higher changes. Different behaviours are observed on the MK charges of those five atoms corresponding to the hydrochloride species in both media. Hence, the charges on the N3 atoms have the higher values, as expected due to the presences in these species of electronegative Cl atoms. The Mulliken charges on those five atoms of free base species show practically the same behaviours but, in particular, on the N2 and C8 atoms are observed the most negative values while the NPA charges on C8 atoms of free base, cationic and hydrochloride species show the lower values in both enantioners. The Mulliken charges in the cationic and hydrochloride species present basically the same behaviours but on the N2 atoms are observed the lower values.

Table 6.

Mulliken, Merz-Kollman and NPA charges, molecular electrostatic potentials (MEP) and bond orders, expressed as Wiberg indexes for three forms of S(-) and R(+)-promethazine in gas phase and in aqueous solution by using B3LYP/6-31G* calculations.

| S(-)-Free base | ||||||||||

| GAS |

PCM |

|||||||||

| Atoms |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

| S1 | -0.120 | 0.157 | 0.330 | -59.182 | 2.335 | -0.118 | 0.156 | 0.328 | -59.182 | 2.333 |

| N2 | -0.311 | -0.581 | -0.452 | -18.312 | 3.305 | -0.360 | -0.581 | -0.449 | -18.311 | 3.305 |

| N3 | -0.346 | -0.365 | -0.506 | -18.356 | 3.127 | -0.357 | -0.367 | -0.501 | -18.354 | 3.115 |

| C8 | -0.272 | -0.455 | -0.685 | -14.757 | 3.844 | -0.267 | -0.455 | -0.685 | -14.756 | 3.844 |

| C11 | -0.222 | -0.300 | -0.468 | -14.719 | 3.819 | -0.266 | -0.305 | -0.473 | -14.719 | 3.820 |

| C12 |

-0.138 |

-0.308 |

-0.475 |

-14.719 |

3.819 |

-0.124 |

-0.311 |

-0.479 |

-14.720 |

3.820 |

| S(-)-Cationic | ||||||||||

| GAS |

PCM |

|||||||||

| Atoms |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

|||||

| S1 | -0.097 | 0.186 | 0.348 | -59.085 | 2.343 | |||||

| N2 | -0.122 | -0.587 | -0.471 | -18.197 | 3.264 | |||||

| N3 | -0.025 | -0.492 | -0.450 | -18.052 | 3.469 | |||||

| C8 | -0.279 | -0.498 | -0.718 | -14.593 | 3.809 | |||||

| C11 | -0.335 | -0.348 | -0.475 | -14.519 | 3.713 | |||||

| C12 |

-0.368 |

-0.351 |

-0.479 |

-14.519 |

3.715 |

|||||

| S(-)-Hydrochloride | ||||||||||

| GAS |

PCM |

|||||||||

| Atoms |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

| S1 | -0.106 | 0.171 | 0.340 | -59.167 | 2.339 | -0.101 | 0.174 | 0.340 | -59.164 | 2.338 |

| N2 | -0.215 | -0.583 | -0.456 | -18.291 | 3.291 | -0.257 | -0.586 | -0.453 | -18.283 | 3.294 |

| N3 | 0.370 | -0.481 | -0.497 | -18.250 | 3.341 | 0.452 | -0.480 | -0.483 | -18.223 | 3.383 |

| C8 | -0.212 | -0.488 | -0.708 | -14.733 | 3.816 | -0.180 | -0.490 | -0.711 | -14.725 | 3.811 |

| C11 | -0.400 | -0.321 | -0.477 | -14.673 | 3.756 | -0.357 | -0.328 | -0.474 | -14.660 | 3.745 |

| C12 |

-0.348 |

-0.325 |

-0.481 |

-14.673 |

3.759 |

-0.337 |

-0.334 |

-0.479 |

-14.658 |

3.748 |

| R(+)-Free base | ||||||||||

| GAS |

PCM |

|||||||||

| Atoms |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

| S1 | -0.344 | 0.155 | 0.329 | -59.182 | 2.334 | -0.126 | 0.154 | 0.327 | -59.183 | 2.332 |

| N2 | -0.344 | -0.584 | -0.455 | -18.313 | 3.303 | -0.018 | -0.583 | -0.454 | -18.312 | 3.304 |

| N3 | -0.344 | -0.387 | -0.511 | -18.354 | 3.112 | -0.336 | -0.390 | -0.504 | -18.353 | 3.104 |

| C8 | -0.330 | -0.484 | -0.695 | -14.753 | 3.836 | -0.341 | -0.484 | -0.694 | -14.752 | 3.837 |

| C11 | -0.255 | -0.296 | -0.472 | -14.723 | 3.815 | -0.215 | -0.300 | -0.476 | -14.723 | 3.816 |

| C12 |

-0.123 |

-0.306 |

-0.469 |

-14.720 |

3.821 |

-0.127 |

-0.309 |

-0.473 |

-14.720 |

3.822 |

| R(+)-Cationic | ||||||||||

| GAS |

PCM |

|||||||||

| Atoms |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

| S1 | -0.106 | 0.188 | 0.349 | -59.085 | 2.343 | -0.090 | 0.190 | 0.351 | -59.088 | 2.341 |

| N2 | 0.033 | -0.586 | -0.471 | -18.197 | 3.263 | -0.048 | -0.591 | -0.460 | -18.193 | 3.276 |

| N3 | 0.046 | -0.495 | -0.449 | -18.050 | 3.470 | 0.033 | -0.490 | -0.447 | -18.047 | 3.471 |

| C8 | -0.145 | -0.499 | -0.722 | -14.597 | 3.805 | -0.155 | -0.492 | -0.719 | -14.593 | 3.806 |

| C11 | -0.308 | -0.343 | -0.476 | -14.521 | 3.708 | -0.298 | -0.343 | -0.476 | -14.519 | 3.707 |

| C12 |

-0.384 |

-0.351 |

-0.473 |

-14.519 |

3.713 |

-0.358 |

-0.353 |

-0.473 |

-14.517 |

3.711 |

| R(+)-Hydrochloride | ||||||||||

| GAS |

PCM |

|||||||||

| Atoms |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

MK |

Mulliken |

NPA |

MEP |

BO |

| S1 | -0.129 | 0.158 | 0.331 | -59.173 | 2.335 | -0.122 | 0.160 | 0.332 | -59.170 | 2.335 |

| N2 | -0.132 | -0.588 | -0.457 | -18.299 | 3.295 | -0.226 | -0.588 | -0.456 | -18.292 | 3.293 |

| N3 | 0.407 | -0.481 | -0.492 | -18.244 | 3.353 | 0.454 | -0.482 | -0.479 | -18.221 | 3.389 |

| C8 | -0.208 | -0.496 | -0.710 | -14.725 | 3.818 | -0.190 | -0.497 | -0.712 | -14.715 | 3.816 |

| C11 | -0.319 | -0.315 | -0.476 | -14.671 | 3.753 | -0.314 | -0.322 | -0.475 | -14.660 | 3.743 |

| C12 | -0.448 | -0.324 | -0.472 | -14.668 | 3.760 | -0.415 | -0.332 | -0.471 | -14.657 | 3.749 |

Fig. 4.

Calculated Merz-Kollman charges of free base, cationic and hydrocloride species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers of promethazine by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method.

The bond orders (BO) expressed as Wiberg indexes in the three species of both enantiomers in the two media have approximately the same values and behaviours, observing the higher values in the C8, C11 and C12 atoms and the lower values in the S1 atoms. In general, higher values are observed for the N2 atoms of the free base and hydrochloride species of both S(-) and R(+)-PTZ in the two media than for the N3 atoms and only in the cationic species are observed higher values in the N3 atoms.

The molecular electrostatic potentials (MEP) presented in Table 6 show practically the same values and behaviours in the three species of both enantiomers, however, when the surfaces of these species are mapped the colorations show important differences among them, as can be seen in Fig. 5. Thus, the cationic species of both enantiomers in gas phase show blue colours on the entire surface but, in particular, strong blue colours it is observed on the protonated N–H region. In the free base species the strong red colours are observed on the N3 atoms and S1 atoms while in the hydrochloride species the strong red colours are observed on the Cl atoms. Hence, the typical nucleophilic sites are clearly identified with red colours while the electrophilic sites with blue colours, as observed in other species [6, 7, 8, 9].

Fig. 5.

Calculated electrostatic potential surfaces on the molecular surfaces of the free base, cationic and hydrochloride species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers of promethazine. B3LYP functional and 6-31G* basis set. Isodensity value of 0.005.

3.4. NBO study

For the three species of both S(-) and R(+)-PTZ enantiomers the main delocalization energies in gas and aqueous solution were calculated by using B3LYP/6-31G* calculations with the NBO program [58]. The resulted for the three species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ are summarized in Tables 7 and 8, respectively. Different interactions can be observed in the three species and, especially in the hydrochloride species due to the presence of Cl atoms where in particular, the π*→π* and π→π* interactions present the higher values in the S(-) and R(+)-PTZ forms, respectively. Thus, the free base (3509.36–3522.22 kJ/mol) and hydrochloride (6253.53–5840.28 kJ/mol) species present higher total energies than the cationic ones (1541.01 kJ/mol) and, for these reasons, these two species are most stable than the cationic ones. However, the hydrochloride species of R(+)-PTZ have higher values in both media than the corresponding to other enantiomer (7527.88–7332.02 kJ/mol). Nevertheless, the free base of R(+)-PTZ present lower values than the corresponding to S(-)-PTZ (3484.4–3193.04 kJ/mol) while the cationic form of R(+)-PTZ is most stable than the corresponding to S(-)-PTZ (1540.08–1612.71 kJ/mol). These studies shows clearly that the hydrochloride species are most stable than the other two species of both forms and in the two media studied but, in particular the species of R(+)-PTZ show higher total energy values evidencing a slight higher stability than the S(-) one. The three PTZ species show higher stabilities than the corresponding to cyclizine [9].

Table 7.

Main delocalization energies (in kJ/mol) for three species of S(-)-promethazine in gas and aqueous solution by using B3LYP/6-31G* calculations.

| B3LYP/6-31G*a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delocalization | Free base |

Hydrochloride |

||

| Gas | PCM | Gas | PCM | |

| πC6-C13→ π*C9–C15 | 74.32 | 74.28 | 73.40 | 73.19 |

| πC6-C13→ π*C17–C19 | 88.41 | 88.49 | 85.98 | 85.77 |

| πC7-C14→ π*C10–C16 | 74.49 | 74.61 | 72.73 | 72.02 |

| πC7-C14→ π*C18–C20 | 88.28 | 88.49 | 85.23 | 85.19 |

| πC9-C15→ π*C6–C13 | 83.56 | 83.39 | 85.27 | 85.27 |

| πC9-C15→ π*C17–C19 | 71.18 | 71.27 | 72.02 | 71.98 |

| πC10-C16→ π*C7–C14 | 83.81 | 83.60 | 85.90 | 86.19 |

| πC10-C16→ π*C18–C20 | 71.52 | 71.60 | 72.23 | 72.10 |

| πC17-C19→ π*C6–C13 | 79.59 | 79.59 | 81.34 | 81.97 |

| πC17-C19→ π*C9–C15 | 93.84 | 93.67 | 94.09 | 94.26 |

| πC18-C20→ π*C7–C14 | 80.05 | 80.21 | 82.05 | 82.26 |

| πC18-C20→ π*C10–C16 | 93.75 | 93.67 | 94.26 | 94.30 |

| Σπ→π* | 982.8 | 982.87 | 984.5 | 984.5 |

| LP(2)S1→ π*C9–C15 | 45.98 | 45.44 | 46.27 | 46.02 |

| LP(2)S1→ π*C10–C16 | 45.98 | 45.23 | 46.36 | 46.27 |

| LP(1)N2→ π*C6–C13 | 99.86 | 99.36 | 92.96 | 94.89 |

| LP(1)N2→ π*C7–C14 | 100.74 | 99.44 | 94.30 | 97.56 |

| ΣLP→π* | 292.56 | 289.47 | 279.89 | 284.74 |

| π*C9–C15→ π*C17–C19 | 1106.65 | 1113.09 | ||

| π*C10–C16→ π*C18–C20 | 1127.35 | 1136.79 | ||

| π*C6–C13→ π*C17–C19 | 1101.14 | 978.58 | ||

| π*C7–C14→ π*C18–C20 | 909.65 | 805.44 | ||

| π*C9–C15→ π*C17–C19 | 1057.33 | 1045.67 | ||

| π*C10–C16→ π*C18–C20 | 1040.23 | 1046.42 | ||

| Σπ*→π* | 2234 | 2249,88 | 4108,35 | 3876,11 |

| σN3-C4→ LP(1)*H41 | 44,60 | 62,57 | ||

| σN3-C11→ LP(1)*H41 | 50,08 | 62,82 | ||

| σN3-C12→ LP(1)*H41 | 47,61 | 60,19 | ||

| Σσ→LP* | 142,29 | 185,58 | ||

| LP(1)N3→ LP(1)*H41 | 1158,49 | 1456,02 | ||

| LP(1)Cl42→ LP(1)*H41 | 46,94 | 16,51 | ||

| LP(4)Cl42→ LP(1)*H41 | 797,46 | 306,06 | ||

| ΣLP→LP* | 2002,89 | 1778,59 | ||

| ΣTOTAL | 3509.36 | 3522,22 | 6253,53 | 5840,28 |

| Cationica | ||||

| Delocalization | Gas | |||

| πC13-C17→ π*C6–C9 | 47.86 | |||

| πC15-C19→ π*C6–C9 | 43.22 | |||

| πC15-C19→ π*C13–C17 | 46.98 | |||

| Σπ→π* | 138.06 | |||

| πC7-C10→ LP(1)*C16 | 93.51 | |||

| πC18-C20→ LP(1)*C16 | 107.22 | |||

| Σπ→LP* | 200.73 | |||

| LP(1)C14→ π*C7–C10 | 171.17 | |||

| LP(1)C14→ π*C18–C20 | 125.57 | |||

| LP(1)C16→ π*C7–C10 | 176.65 | |||

| LP(1)C16→ π*C18–C20 | 133.97 | |||

| ΣLP→π* | 607.36 | |||

| π*C6–C9→ π*C13–C17 | 361.99 | |||

| π*C6–C9→ π*C15–C19 | 232.87 | |||

| Σπ*→π* | 594.86 | |||

| ΣTOTAL | 1541.01 | |||

The letters bold indicated RMSD values.

This work.

Table 8.

Main delocalization energies (in kJ/mol) for three species of R(+)-promethazine in gas and aqueous solution by using B3LYP/6-31G* calculations.

| B3LYP/6-31G*a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delocalization | Free base |

Hydrochloride |

||

| Gas | PCM | Gas | PCM | |

| πC6-C13→ π*C9–C15 | 74.70 | 74.65 | 76.53 | 76.07 |

| πC6-C13→ π*C17–C19 | 88.41 | 88.49 | 86.23 | 85.65 |

| πC7-C14→ π*C10–C16 | 74.65 | 72.48 | 72.23 | |

| πC7-C14→ π*C18–C20 | 88.45 | 86.82 | 86.57 | |

| πC9-C15→ π*C6–C13 | 83.43 | 83.35 | 83.06 | 82.51 |

| πC9-C15→ π*C17–C19 | 71.18 | 71.14 | 70.56 | 70.30 |

| πC10-C16→ π*C7–C14 | 83.68 | 84.98 | 85.77 | |

| πC10-C16→ π*C18–C20 | 71.44 | 72.15 | 72.56 | |

| πC17-C19→ π*C6–C13 | 79.80 | 79.88 | 82.26 | 82.93 |

| πC17-C19→ π*C9–C15 | 93.97 | 93.97 | 95.89 | 96.14 |

| πC18-C20→ π*C7–C14 | 80.09 | 80.59 | ||

| πC18-C20→ π*C10–C16 | 93.84 | 93.13 | ||

| Σπ→π* | 983.64 | 491.48 | 810.96 | 984.45 |

| πC10-C16→ LP(1)*C7 | 202.39 | |||

| πC10-C16→ LP(1)*C20 | 167.07 | |||

| πC14-C18→ LP(1)*C7 | 219.66 | |||

| πC14-C18→ LP(1)*C20 | 183.38 | |||

| Σπ→LP* | 772.5 | |||

| LP(2)S1→ π*C9–C15 | 45.73 | 45.02 | 44.73 | 44.77 |

| LP(2)S1→ π*C10–C16 | 45.81 | 45.27 | 47.23 | 47.02 |

| LP(1)N2→ π*C6–C13 | 99.32 | 99.44 | 91.37 | 92.13 |

| LP(1)N2→ π*C7–C14 | 101.03 | 101.78 | 100.74 | |

| LP(1)C20→ π*C10–C16 | 337.28 | |||

| LP(1)C20→ π*C14–C18 | 305.43 | |||

| ΣLP→π* | 291.89 | 832.44 | 285.11 | 284.66 |

| LP(1)*C7→ π*C10–C16 | 267.60 | |||

| LP(1)*C7→ π*C14–C18 | 258.91 | |||

| ΣLP*→π* | ||||

| π*C9–C15→ π*C17–C19 | 1084.83 | |||

| π*C10–C16→ π*C18–C20 | 1123.92 | |||

| π*C6–C13→ π*C17–C19 | 1247.39 | 1083.04 | ||

| π*C7–C14→ π*C18–C20 | 1071.67 | 978.87 | ||

| π*C9–C15→ π*C17–C19 | 1096.62 | 843.40 | 817.61 | |

| π*C10–C16→ π*C18–C20 | 1184.32 | 1207.85 | ||

| Σπ*→π* | 2208.87 | 1096.62 | 4346.78 | 4087.37 |

| σN3-C4→ LP(1)*H41 | 49.70 | 61.65 | ||

| σN3-C11→ LP(1)*H41 | 49.16 | 59.73 | ||

| σN3-C12→ LP(1)*H41 | 46.48 | 57.85 | ||

| Σσ→LP* | 145.34 | 179.23 | ||

| LP(1)N3→ LP(1)*H41 | 1234.86 | 1491.17 | ||

| LP(1)Cl42→ LP(1)*H41 | ||||

| LP(4)Cl42→ LP(1)*H41 | 704.83 | 305.14 | ||

| ΣLP→LP* | 1939.69 | 1796.31 | ||

| ΣTOTAL | 3484.4 | 3193.04 | 7527.88 | 7332.02 |

| Cationica | ||||

| Delocalization | Gas | PCM | ||

| πC13-C17→ π*C6–C9 | 47.90 | 46.98 | ||

| πC15-C19→ π*C6–C9 | 43.30 | 43.43 | ||

| πC15-C19→ π*C13–C17 | 47.07 | 47.61 | ||

| Σπ→π* | 138.27 | 138.02 | ||

| πC7-C10→ LP(1)*C16 | 93.63 | 94.47 | ||

| πC18-C20→ LP(1)*C16 | 107.30 | 107.05 | ||

| Σπ→LP* | 200.93 | 201.52 | ||

| LP(1)N2→ π*C6–C9 | 42.72 | |||

| LP(1)N2→ π*C7–C10 | 44.68 | |||

| LP(1)C14→ π*C7–C10 | 171.67 | 168.95 | ||

| LP(1)C14→ π*C18–C20 | 125.57 | 125.69 | ||

| LP(1)C16→ π*C7–C10 | 176.65 | 177.86 | ||

| LP(1)C16→ π*C18–C20 | 133.72 | 133.84 | ||

| ΣLP→π* | 607.61 | 693.74 | ||

| π*C6–C9→ π*C13–C17 | 361.78 | 356.18 | ||

| π*C6–C9→ π*C15–C19 | 231.49 | 223.25 | ||

| Σπ*→π* | 593.27 | 579.43 | ||

| ΣTOTAL | 1540.08 | 1612.71 | ||

The letters bold indicated RMSD values.

This work.

3.5. AIM studies

According to the Bader's theory the topological properties are interesting parameters to predict different types of interactions, such as intra or inter-molecular, ionic and hydrogen bonds interactions [59]. Hence, these properties can be easily computed in the bond critical points (BCPs) and in the ring critical points (RCPs) with the AIM2000 program [60]. Here, the electron density, ρ(r), the Laplacian values, ∇2ρ(r), the eigenvalues (λ1, λ2, λ3) of the Hessian matrix and, the |λ1|/λ3 ratio calculated by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method for the three forms of both S(-) and R(+)-PTZ enantiomers can be observed from Tables 9, 10 and 11. Note that the ionic and hydrogen bonds interactions are observed when λ1/λ3< 1 and ∇2ρ(r) > 0 [9]. Here, RCPN1, RCPN2 and RCPN3 are new RCPs formed as a consequence of C⋯H and H⋯H interactions while RCP1, RCP2 and RCP3 are RCPs corresponding to the R1, R2 and R3 rings, as defined in Fig. 1. In all species, the topological properties of RCP1 and RCP3 are practically the same in the two phenyl rings but different from RCP2 because this ring is the phenothiazine ring. First, analyzing the free bases species of both enantiomers, we observed that S(-)-PTZ present two C14⋯H21 and H⋯H interactions in both media but the involved atoms change of H24--H32 in gas phase to H23--H33 in solution. In R(+)-PTZ, the free base presents in gas phase the C14⋯H21 and H22⋯H31 interactions while in solution are observed three different H⋯H interactions. In the cationic species of S(-)-PTZ are not observed interactions while in R(+)-PTZ is observed a H⋯H interaction in gas phase while in solution are observed two C⋯H and a H⋯H interactions. The hydrochloride species of S(-)-PTZ present two interactions in gas phase and three different in solution while in the R(+)-PTZ enantiomer in gas phase (Table 11) are observed five interactions and only three in solution. In the hydrochloride species the Cl⋯H are ionic interactions where in S(-)-PTZ the Cl–H distances are 1.716 Å in gas phase and 2.032 Å in solution while in R(+)-PTZ the distances change to 1.748 Å in gas phase and 2.029 Å in solution. Evidently, both hydrochloride species are the most stable due to the higher values of their topological properties. These results are in agreement with those analyzed by NBO studies. The hydrochloride species of both forms of PTZ reveals higher stabilities than the corresponding to cyclizine [9].

Table 9.

Analysis of the Bond Critical Points (BCPs) and Ring critical point (RCPs) for three species of S(-)-promethazine in gas and aqueous solution by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method.

| B3LYP/6-31G* Method | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free base | ||||||||

| Gas phase | ||||||||

| Parameter# |

C14--H21 |

RCPN1 |

H24--H32 |

RCPN2 |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

|

| ρ(r) | 0.0088 | 0.0088 | 0.0095 | 0.0095 | 0.0198 | 0.0170 | 0.0198 | |

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.0333 | 0.0357 | 0.0400 | 0.0421 | 0.1580 | 0.1104 | 0.1580 | |

| λ1 | -0.0043 | -0.0036 | -0.0084 | -0.0080 | -0.0146 | -0.0055 | -0.0145 | |

| λ2 | -0.0011 | 0.0013 | -0.0014 | 0.0015 | 0.0815 | 0.0552 | 0.0813 | |

| λ3 | 0.0388 | 0.0379 | 0.0500 | 0.0485 | 0.0910 | 0.0608 | 0.0911 | |

| |λ1|/λ3 | 0.1108 | 0.0950 | 0.1680 | 0.1649 | 0.1604 | 0.0905 | 0.1592 | |

| Distances (Å) |

2.693 |

2.190 |

||||||

| Aqueous solution |

||||||||

| Parameter# |

C14--H21 |

RCPN1 |

H23--H33 |

RCPN2 |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

|

| ρ(r) | 0.0093 | 0.0090 | 0.0133 | 0.0133 | 0.0198 | 0.0169 | 0.0198 | |

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.0344 | 0.0398 | 0.0626 | 0.0656 | 0.1573 | 0.1103 | 0.1572 | |

| λ1 | -0.0049 | -0.0026 | -0.0084 | -0.0077 | -0.0145 | -0.0055 | -0.0144 | |

| λ2 | 0.0035 | 0.0050 | -0.0019 | 0.0020 | 0.0809 | 0.0569 | 0.0808 | |

| λ3 | 0.0429 | 0.0375 | 0.0729 | 0.0712 | 0.0909 | 0.0590 | 0.0908 | |

| |λ1|/λ3 | 0.1142 | 0.0693 | 0.1152 | 0.1081 | 0.1595 | 0.0932 | 0.1586 | |

| Distances (Å) |

2.646 |

2.086 |

||||||

| Cationic | ||||||||

| Gas phase | ||||||||

| Parameter# |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

|||||

| ρ(r) | 0.0199 | 0.0173 | 0.0199 | |||||

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.1584 | 0.1084 | 0.1586 | |||||

| λ1 | -0.0146 | -0.0050 | -0.0146 | |||||

| λ2 | 0.0832 | 0.0469 | 0.0835 | |||||

| λ3 | 0.0896 | 0.0665 | 0.0896 | |||||

| |λ1|/λ3 |

0.1629 |

0.0752 |

0.1629 |

|||||

| Hydrochloride | ||||||||

| Gas phase | ||||||||

| Parameter# |

Cl42--H25 |

Cl42--H41 |

RCPN1 |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

||

| ρ(r) | 0.0080 | 0.0804 | 0.0080 | 0.0198 | 0.0171 | 0.0198 | ||

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.0263 | 0.0866 | 0.0284 | 0.1582 | 0.1100 | 0.1582 | ||

| λ1 | -0.0062 | -0.1359 | -0.0062 | -0.0146 | -0.0053 | -0.0145 | ||

| λ2 | -0.0017 | -0.1357 | 0.0018 | 0.0822 | 0.0530 | 0.0820 | ||

| λ3 | 0.0342 | 0.3583 | 0.0327 | 0.0905 | 0.0624 | 0.0906 | ||

| |λ1|/λ3 | 0.1813 | 0.3793 | 0.1896 | 0.1613 | 0.0849 | 0.1600 | ||

| Distances (Å) |

2.908 |

1.716 |

||||||

| Aqueous solution | ||||||||

| Parameter# |

C13--H23 |

RCPN1 |

H22---28 |

RCPN2 |

Cl42--H41 |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

| ρ(r) | 0.0134 | 0.0133 | 0.0090 | 0.0090 | 0.0416 | 0.0198 | 0.0169 | 0.0198 |

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.0617 | 0.0666 | 0.0384 | 0.0398 | 0.0764 | 0.1574 | 0.1094 | 0.1574 |

| λ1 | -0.0093 | -0.0081 | -0.0079 | -0.0074 | -0.0534 | -0.0145 | -0.0056 | -0.0145 |

| λ2 | -0.0031 | 0.0036 | -0.0014 | 0.0014 | -0.0532 | 0.0813 | 0.0552 | 0.0811 |

| λ3 | 0.0742 | 0.0711 | 0.0476 | 0.0458 | 0.1828 | 0.0906 | 0.0597 | 0.0907 |

| |λ1|/λ3 | 0.1253 | 0.1139 | 0.1660 | 0.1616 | 0.2921 | 0.1600 | 0.0938 | 0.1599 |

| Distances (Å) | 2.508 | 2.189 | 2.032 | |||||

# This symbol implies values in a.u. units.

Table 10.

Analysis of the Bond Critical Points (BCPs) and Ring critical point (RCPs) for free base and cationic species of R(+)-promethazine in gas and aqueous solution by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method.

| B3LYP/6-31G* Method | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free base | |||||||||

| Gas phase | |||||||||

| Parameter# |

C14--H21 |

RCPN1 |

H22--H31 |

RCPN2 |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

||

| ρ(r) | 0.0084 | 0.0084 | 0.0120 | 0.0110 | 0.0198 | 0.0170 | 0.0198 | ||

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.0315 | 0.0332 | 0.0483 | 0.0571 | 0.1580 | 0.1105 | 0.1580 | ||

| λ1 | -0.0037 | -0.0033 | -0.0127 | 0.0078 | -0.0146 | -0.0055 | -0.0145 | ||

| λ2 | -0.0008 | 0.0009 | -0.0083 | 0.0107 | 0.0815 | 0.0551 | 0.0813 | ||

| λ3 | 0.0362 | 0.0355 | 0.0694 | 0.0542 | 0.0911 | 0.0609 | 0.0911 | ||

| |λ1|/λ3 | 0.1022 | 0.0930 | 0.1830 | -0.1439 | 0.1603 | 0.0903 | 0.1592 | ||

| Distances (Å) |

2.727 |

2.024 |

|||||||

| Aqueous solution | |||||||||

| Parameter# |

H31--H34 |

H22--H31 |

RCPN1 |

H23--H33 |

RCPN2 |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

|

| ρ(r) | 0.0057 | 0.0128 | 0.0057 | 0.0132 | 0.0132 | 0.0198 | 0.0170 | 0.0198 | |

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.0212 | 0.0511 | 0.0208 | 0.0605 | 0.0656 | 0.1573 | 0.1103 | 0.1572 | |

| λ1 | -0.0041 | -0.0137 | -0.0038 | -0.0093 | -0.0080 | -0.0145 | -0.0055 | -0.0144 | |

| λ2 | -0.0022 | -0.0092 | 0.0029 | -0.0033 | 0.0039 | 0.0809 | 0.0559 | 0.0807 | |

| λ3 | 0.0275 | 0.0742 | 0.0216 | 0.0732 | 0.0697 | 0.0909 | 0.0598 | 0.0909 | |

| |λ1|/λ3 | 0.1491 | 0.1846 | 0.1759 | 0.1270 | 0.1148 | 0.1595 | 0.0920 | 0.1584 | |

| Distances (Å) |

2.353 |

1.995 |

2.072 |

||||||

| Cationic | |||||||||

| Gas phase | |||||||||

| Parameter# |

H22--H31 |

RCPN1 |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

||||

| ρ(r) | 0.0120 | 0.0108 | 0.0199 | 0.0173 | 0.0199 | ||||

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.0478 | 0.0533 | 0.1584 | 0.1084 | 0.1588 | ||||

| λ1 | -0.0131 | -0.0087 | -0.0146 | -0.0049 | -0.0146 | ||||

| λ2 | -0.0086 | 0.0107 | 0.0832 | 0.0472 | 0.0836 | ||||

| λ3 | 0.0696 | 0.0513 | 0.0897 | 0.0664 | 0.0896 | ||||

| |λ1|/λ3 | 0.1882 | 0.1696 | 0.1628 | 0.0738 | 0.1629 | ||||

| Distances (Å) |

2.008 |

||||||||

| Aqueous solution | |||||||||

| Parameter# |

C14--H21 |

RCPN1 |

C13--H23 |

RCPN2 |

H22--H31 |

RCPN3 |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

| ρ(r) | 0.0085 | 0.0085 | 0.0131 | 0.0131 | 0.0124 | 0.0112 | 0.0198 | 0.0169 | 0.0198 |

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.0326 | 0.03369 | 0.0617 | 0.0639 | 0.0495 | 0.0556 | 0.1576 | 0.1095 | 0.1575 |

| λ1 | -0.0033 | -0.0030 | -0.0085 | -0.0080 | -0.0135 | -0.0090 | -0.0145 | -0.0056 | -0.0145 |

| λ2 | -0.0006 | 0.0006 | -0.0014 | 0.0015 | -0.0087 | 0.0108 | 0.0815 | 0.0553 | 0.0811 |

| λ3 | 0.0366 | 0.0360 | 0.0716 | 0.0704 | 0.0717 | 0.0538 | 0.0906 | 0.0598 | 0.0908 |

| |λ1|/λ3 | 0.0902 | 0.0833 | 0.1187 | 0.1136 | 0.1883 | 0.1673 | 0.1600 | 0.0936 | 0.1597 |

| 2.718 | 2.520 | 1.996 | |||||||

# This symbol implies values in a.u. units.

Table 11.

Analysis of the Bond Critical Points (BCPs) and Ring critical point (RCPs) for three species of R(+)-promethazine in gas and aqueous solution by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method.

| B3LYP/6-31G* Method | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrochloride | ||||||||||||

| Gas phase | ||||||||||||

| Parameter# |

C5⋯H34 |

RCPN1 |

C13⋯H23 |

RCPN2 |

H22⋯H31 |

RCPN3 |

Cl42⋯H23 |

Cl42⋯H41 |

RCPN3 |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

| ρ(r) | 0.0112 | 0.0112 | 0.0130 | 0.0130 | 0.0120 | 0.0109 | 0.0093 | 0.0746 | 0.0082 | 0.0198 | 0.0170 | 0.0199 |

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.0508 | 0.0508 | 0.0624 | 0.0624 | 0.0484 | 0.0548 | 0.0311 | 0.0935 | 0.0343 | 0.1580 | 0.1096 | 0.1584 |

| λ1 | -0.0092 | -0.0092 | -0.0090 | -0.0090 | -0.0130 | -0.0087 | -0.0072 | -0.1220 | -0.0057 | -0.0146 | -0.0055 | -0.0146 |

| λ2 | -0.0005 | -0.0005 | -0.0006 | -0.0006 | -0.0085 | 0.0107 | -0.0051 | -0.1219 | 0.0068 | 0.0815 | 0.0535 | 0.0820 |

| λ3 | 0.0606 | 0.0606 | 0.0720 | 0.0720 | 0.0699 | 0.0528 | 0.0435 | 0.3374 | 0.0331 | 0.0910 | 0.0615 | 0.0909 |

| |λ1|/λ3 | 0.1518 | 0.1518 | 0.1250 | 0.1250 | 0.1860 | 0.1648 | 0.1655 | 0.3616 | 0.1722 | 0.1604 | 0.0894 | 0.1606 |

| Distances (Å) |

2.637 |

2.520 |

2.008 |

2.814 |

1.748 |

|||||||

| Aqueous solution | ||||||||||||

| Parameter# |

C13⋯H23 |

RCPN1 |

H22⋯H31 |

RCPN2 |

Cl42⋯H41 |

RCP1 |

RCP2 |

RCP3 |

||||

| ρ(r) | 0.0134 | 0.0134 | 0.0122 | 0.0111 | 0.0418 | 0.0198 | 0.0169 | 0.0198 | ||||

| ∇2ρ(r) | 0.0633 | 0.0668 | 0.0494 | 0.0558 | 0.0771 | 0.1575 | 0.1093 | 0.1576 | ||||

| λ1 | -0.0094 | -0.0085 | -0.0131 | -0.0088 | -0.0536 | -0.0145 | -0.0057 | -0.0145 | ||||

| λ2 | -0.0023 | 0.0025 | -0.0085 | 0.0106 | -0.0535 | 0.0813 | 0.0557 | 0.0808 | ||||

| λ3 | 0.0750 | 0.0726 | 0.0711 | 0.0537 | 0.1843 | 0.0907 | 0.0592 | 0.0911 | ||||

| |λ1|/λ3 | 0.1253 | 0.1171 | 0.1842 | 0.1639 | 0.2908 | 0.1599 | 0.0963 | 0.1592 | ||||

| Distances (Å) | 2.507 | 1.999 | 2.029 | |||||||||

# This symbol implies values in a.u. units.

3.6. Frontier orbitals and global descriptors studies

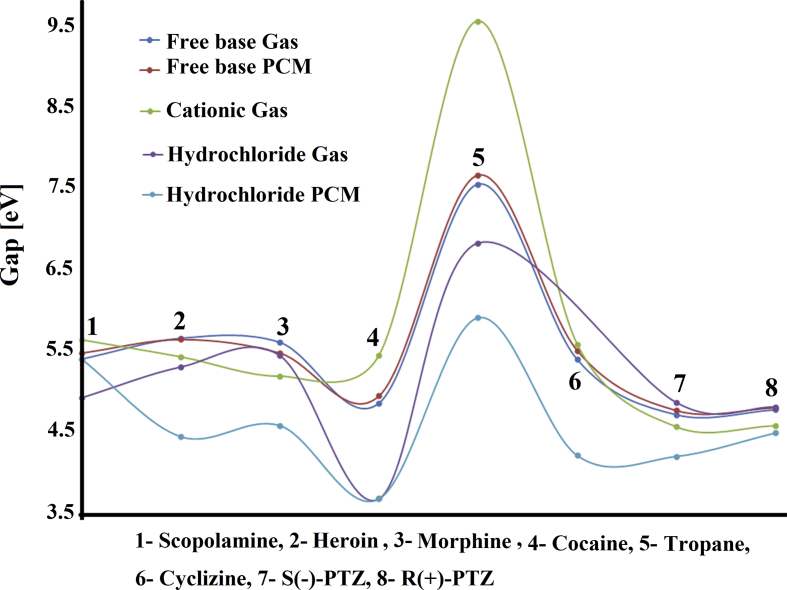

To predict reactivities and behaviours of both S(-) and R(+)-PTZ forms are of interest to understand why the presence of two N–CH3 groups in their structures present the same biological activities than cyclizine despite those two groups in PTZ are not linked to rings. Hence, from the frontier orbitals and their differences is possible to compute the gap values [43, 44] and later, by using known equations the chemical potential (μ), electronegativity (χ), global hardness (η), global softness (S), global electrophilicity index (ω) and global nucleophilicity index (Ε) descriptors can be calculated by using the hybrid B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory [45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53]. The gap and descriptors values for both PTZ enantiomers in the two media are presented in Table 12. The evaluation of gap values for the three species show easily that the hydrochloride species of both S(-) and R(+)-PTZ forms in solution have low gap values and, for these reasons, the two species are more reactive but the S(-) form is most reactive than the R(+)-PTZ one, as expected because this latter form presents higher stability by NBO analysis (>Total energy). Moreover, the free base and cationic species of S(-) form are most reactive than the corresponding to the R(+) form. Comparisons of these results with the observed for similar species containing N–CH3 groups, as scopolamine, heroin morphine, cocaine, tropane and cyclizine are presented in Table 13 while their behaviours can be seen in Fig. 6. This figure shows that the hydrochloride species of cocaine in both media present the lower gap values and, obviously, are the most reactive species while in all media the tropane species are the less reactive being, the cationic one in gas phase the less reactive. Note that the free base and cationic species of two forms of PTZ are most reactive than the corresponding to cyclizine, however, the hydrochloride species of cyclizine is most reactive than both forms of PTZ. If now the descriptors are analyzed it is observed from Table 12 that the three species of S(-)-PTZ have higher electrophilicity indexes than the corresponding to R(+) form while, on the contrary, the species of R(+) form have higher nucleophilicity indexes than the species of S(-)-PTZ. The only exception is the hydrochloride species in gas phase of S(-) form because it present a higher value (-7.6061 eV) than the corresponding to R(+) form (7.1020 eV). If both electrophilicity and nucleophilicity indexes of the two S(-) and R(+)-PTZ are compared with other species from Table 14 the behaviours can easily be seen in Fig. 7. Higher electrophilicity indexes are observed in the cationic and hydrochloride species of PTZ than cyclizine while the cationic species of cyclizine have higher nucleophilicity index than both species of PTZ. The higher electrophilicity indexes are observed for all cationic forms in gas phase and, in particular, for cocaine while tropane in both media presents the lowest values. In relation to nucleophilicity indexes, the cationic species of tropane in gas phase presents the highest negative value indicating probably that for these two reasons, this species is the less reactive than the other ones (see Table 13).

Table 12.

Frontier molecular HOMO and LUMO orbitals , gap values and descriptors for the three species of S(−) and R(+)-promethazine (in eV) in gas and aqueous solution by using the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

| Orbitals | Free base |

Cationic |

Hydrochloride |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas | PCM | Gas | PCM | Gas | PCM | |

| S(-)-promethazine | ||||||

| HOMO | -5.0096 | -5.0559 | -7.943 | -5.5593 | -5.0151 | |

| LUMO | -0.2939 | -0.2857 | -3.3769 | -0.6939 | -0.8109 | |

| ∣GAP∣ |

4.7157 |

4.7702 |

4.5661 |

4.8654 |

4.2042 |

|

| Descriptors | ||||||

| χ | -2.3579 | -2.3851 | -2.2831 | -2.4327 | -2.1021 | |

| μ | -2.6518 | -2.6708 | -5.6600 | -3.1266 | -2.9130 | |

| η | 2.3579 | 2.3851 | 2.2831 | 2.4327 | 2.1021 | |

| S | 0.2121 | 0.2096 | 0.2190 | 0.2055 | 0.2379 | |

| ω | 1.4911 | 1.4954 | 7.0158 | 2.0092 | 2.0184 | |

| Ε |

-6.2524 |

-6.3701 |

-12.9219 |

-7.6061 |

-6.1234 |

|

| R(+)-promethazine | ||||||

| HOMO | -5.0504 | -5.0776 | -7.9403 | -5.5593 | -5.3579 | -5.1538 |

| LUMO | -0.2748 | -0.2748 | -3.3633 | -0.6939 | -0.5469 | -0.6612 |

| ∣GAP∣ |

4.7756 |

4.8028 |

4.5770 |

4.8654 |

4.8110 |

4.4926 |

| Descriptors | ||||||

| χ | -2.3878 | -2.4014 | -2.2885 | -2.4327 | -2.4055 | -2.2463 |

| μ | -2.6626 | -2.6762 | -5.6518 | -3.1266 | -2.9524 | -2.9075 |

| η | 2.3878 | 2.4014 | 2.2885 | 2.4327 | 2.4055 | 2.2463 |

| S | 0.2094 | 0.2082 | 0.2185 | 0.2055 | 0.2079 | 0.2226 |

| ω | 1.4845 | 1.4912 | 6.9790 | 2.0092 | 1.8118 | 1.8817 |

| Ε | -6.3578 | -6.4266 | -12.9341 | -7.6061 | -7.1020 | -6.5311 |

χ = - [E(LUMO)- E(HOMO)]/2; μ = [E(LUMO) + E(HOMO)]/2; η = [E(LUMO) - E(HOMO)]/2.

S = ½η; ω = μ2/2η; Ε = μ*η.

Table 13.

Frontier molecular HOMO and LUMO orbitals and gap values for the three species of S(-) and R(+)-promethazine compared with other species in gas and aqueous solution phases by using the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

| Orbital | Scopolamine#,b | Heroinc | Morphined | Cocainee | Tropanef | Cyclizineg | Promethazinea |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S(-) | R(+) | |||||||

| Free base/Gas phase | ||||||||

| ∣GAP∣ |

5.4004 |

5.6563 |

5.6044 |

4.8580 |

7.5506 |

5.3946 |

4.7157 |

4.7756 |

| Free base/Aqueous solution | ||||||||

| ∣GAP∣ |

5.4758 |

5.6414 |

5.4750 |

4.9487 |

7.6611 |

5.5067 |

4.7702 |

4.8028 |

| Cationic/Gas phase | ||||||||

| ∣GAP∣ |

5.6356 |

5.4268 |

5.1889 |

5.4468 |

9.5595 |

5.5823 |

4.5661 |

4.5770 |

| Hydrochloride/Gas phase | ||||||||

| ∣GAP∣ |

4.9239 |

5.3024 |

5.4417 |

3.6813 |

6.8246 |

4.8654 |

4.8110 |

|

| Hydrochloride/Aqueous solution | ||||||||

| ∣GAP∣ | 5.4026 | 4.4469 | 4.5840 | 3.6813 | 5.9119 | 4.2159 | 4.2042 | 4.4926 |

Fig. 6.

Calculated gap values of free base, cationic and hydrocloride species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers of promethazine in both media by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method compared with reported values for alkaloids and antihistaminic agents.

Table 14.

Global electrophilicity(ω) and nucleophilicity (E) indexes for the three species of S(-) and R(+)-promethazine compared with other species in gas and aqueous solution phases by using the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

| Descriptor | Scopolamine#,b | Heroinc | Morphined | Cocainee | Tropanef | Cyclizineg | Promethazinea |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S(-) | R(+) | |||||||

| Free base/Gas phasea | ||||||||

| ω | 1.7393 | 1.5083 | 1.3639 | 2.5183 | 0.3914 | 1.6777 | 1.4911 | 1.4845 |

| Ε |

-8.2756 |

-8.2606 |

-7.7475 |

-8.4959 |

-6.4905 |

-8.1146 |

-6.2524 |

-6.3578 |

| Free base/Aqueous solutiona | ||||||||

| ω | 1.7504 | 1.5180 | 1.2339 | 2.5297 | 0.4429 | 1.7288 | 1.4954 | 1.4912 |

| Ε |

-8.4763 |

-8.2545 |

-7.1153 |

-8.7546 |

-7.0557 |

-8.4953 |

-6.3701 |

-6.4266 |

| Cationic/gas phasea | ||||||||

| ω | 6.4529 | 6.7459 | 6.8155 | 7.9799 | 6.9598 | 6.5083 | 7.0158 | 6.9790 |

| Ε |

-16.9925 |

-16.4174 |

-15.4288 |

-17.9548 |

-38.9872 |

-16.8238 |

-12.9219 |

-12.9341 |

| Hydrochloride/Aqueous solutiona | ||||||||

| ω | 0.9799 | 1.9667 | 1.8414 | 2.6828 | 0.6421 | 1.9053 | 2.0184 | 1.8817 |

| Ε | -6.2154 | -6.5755 | -6.6589 | -5.7845 | -5.7592 | -5.9742 | -6.1234 | -6.5311 |

Fig. 7.

Calculated electrophilicity indexes of free base, cationic and hydrocloride species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers of promethazine in both media by using the B3LYP/6-31G* method.

3.7. Vibrational study

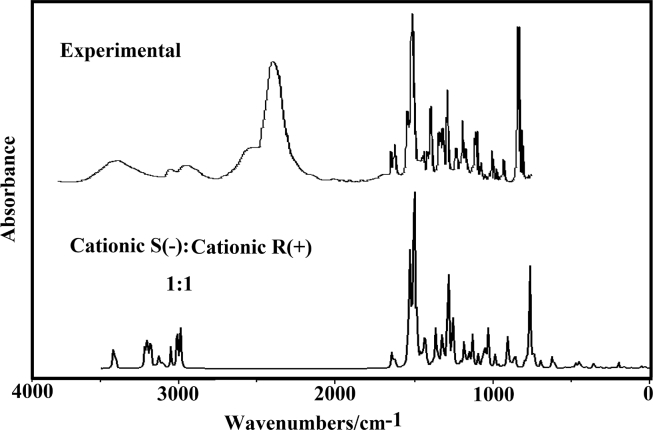

B3LYP calculations have optimized the three species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ forms with C1 symmetries. The normal vibration modes expected for the free base, cationic and hydrochloride species are respectively 114, 117 and 120 and, where all modes are active, in both spectra. The experimental available infrared and Raman spectra for promethazine hydrochloride were taken from Refs [10] and [66]. The experimental IR from Ref [66] was compared with the corresponding predicted for the three species of both enantiomers in Fig. 8 while the comparisons of the corresponding predicted Raman spectra with the experimental one are given in Fig. 9. Evidently, the hydrochloride forms of both enantiomers are not present in the experimental IR spectrum because the predicted intense IR bands of both S(-) and R(+) forms at 1625 and 1713 cm−1 respectively are not observed in the experimental one with the same intensities. Besides, the predicted IR spectra in the 2000-500 cm−1 region show strong differences between the intensities of IR bands at 1459 and 759 cm−1 in the three species of both S(-) and R(+)-PTZ enantiomers but when only the average of cationic forms by using frequencies and intensities Lorentzian band shapes for a 1:1 population ratio of each species the ratio between those two bands decreases notably, as shown in Fig. 10. Note that in the higher wavenumbers region the predicted IR spectra for both cationic species are similar to the corresponding experimental ones. Hence, it is evident the presence of both cationic species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ in the solid phase, as revealed by Borodi et al [19]. The normal internal coordinates, the SQMFF methodology [39] and the Molvib program [42] were used to calculate the harmonic force fields in order to perform the complete vibrational assignments of all species of DHC. The scale factors used were those reported in the literature [40]. In Table 15 are presented the experimental and calculated wavenumbers together with the assignments of three species of S(-) and R(+)-PTZ forms, respectively. Below, discussions of assignments for some groups are presented.

Fig. 8.

Experimental infrared spectrum of hydrocloride promethazine compared with the corresponding predicted for the free base, cationic and hydrochloride species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers by using B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

Fig. 9.

Experimental Raman spectrum of hydrocloride promethazine compared with the corresponding predicted for the free base, cationic and hydrochloride species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers by using B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

Fig. 10.

Experimental infrared spectrum of hydrocloride promethazine compared with the corresponding average predicted for the cationic species of both S(-) and R(+) enantiomers by using frequencies and intensities Lorentzian band shapes for a 1:1 population ratio of each species at B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

Table 15.

Observed and calculated wavenumbers (cm−1) and assignments for the three species of S(-) and R(+)-promethazine in gas phase by using B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

| Experimental |

B3LYP/6-31G* Methoda |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S(-)-PTZ |

R(+)-PTZ |

|||||||||||||

| Free base |

Cationic |

Hydrochloride |

Free base |

Cationic |

Hydrochloride |

|||||||||

| IRc | IRd | Ramane | SQMb | Assignmentsa | SQMb | Assignmentsa | SQMb | Assignmentsa | SQMb | Assignmentsa | SQMb | Assignmentsa | SQMb | Assignmentsa |

| 3391w,br | 3448w | 3411vw | 3295 | νN3-H41 | 3273 | νN3-H41 | ||||||||

| 3104w | 3092 | νC14-H34 | 3092 | νC19-H39 | ||||||||||

| 3091 | νC20-H40 | |||||||||||||

| 3104w | 3090 | νaCH3(C11) | 3090 | νC13-H33 | ||||||||||

| 3087 | νC13-H33 | 3088 | νaCH3(C12) | 3087 | νC14-H34 | |||||||||

| 3081 | νC15-H35 | |||||||||||||

| 3079 | νC20-H40 | 3080 | νC17-H37 | 3080 | νC20-H40 | |||||||||

| 3078 | νC19-H39 | 3078 | νC16-H36 | 3078 | νaCH3(C11) | |||||||||

| 3073 | νC15-H35 | 3071 | νaCH3(C12) | |||||||||||

| 3071 | νC14-H34 | 3072 | νC18-H38 | 3070 | νC17-H37 | |||||||||

| 3066 | νC13-H33 | 3069 | νC20-H40 | 3067 | νC14-H34 | 3066 | νC15-H35 | 3067 | νaCH3(C12) | 3067 | νC16-H36 | |||

| 3069 | νC19-H39 | 3065 | νC19-H39 | 3066 | νC16-H36 | 3063 | νaCH3(C11) | 3060 | νC19-H39 | |||||

| 3058sh | 3059 | νC20-H40 | 3057 | νC17-H37 | 3059 | νC13-H33 | 3058 | νC18-H38 | ||||||

| 3058sh | 3058 | νC19-H39 | 3056 | νC16-H36 νC18-H38 |

3060 | νC20-H40 | 3057 | νC18-H38 | ||||||

| 3051 | νaCH3(C12) | 3057 | νC13-H33 | 3056 | νC17-H37 | 3055 | νC14-H34 | |||||||

| 3050 | νC16-H36 νC15-H35 |

3049 | νC16-H36 | |||||||||||

| 3046 | νC16-H36 | 3050 | νC15-H35 | 3047 | νC15-H35 | |||||||||

| 3045 | νC15-H35 | 3044 | νaCH3(C11) | 3040 | νC18-H38 | |||||||||

| 3046w,br | 3044m | 3039 | νC13-H33 | 3039 | νC17-H37 | 3039 | νaCH3(C12) | |||||||

| 3037 | νC17-H37 | 3037 | νC14-H34 | 3036 | νaCH3(C11) | |||||||||

| 3035 | νaCH3(C12) | |||||||||||||

| 3035sh | 3037 | νC18-H38 | 3031 | νaCH3(C11) | 3032 | νaCH3(C12) | 3030 | νaCH3(C8) | 3031 | νaCH2 | ||||

| 3019 | νaCH3(C11) | 3021 | νaCH3(C11) | 3025 | νaCH3(C8) | |||||||||

| 3006 | νaCH3(C11) | 3013 | νaCH3(C8) | 3014 | νaCH3(C8) | |||||||||

| 3018w | 3004 | νaCH3(C12) | 3012 | νaCH2 | 3012 | νaCH3(C8) | ||||||||

| 2986 | νaCH3(C8) | 2995 | νaCH3(C8) | 2999 | νaCH3(C8) | 3000 | νaCH3(C12) | 2989 | νC4-H21 | |||||

| 2980w | 2984 | νaCH2 | 2984 | νaCH2 | 2986 | νaCH2 | 2999 | νaCH3(C8) | 2982 | νsCH3(C12) | ||||

| 2966sh | 2978 | νaCH3(C12) | 2974 | νaCH3(C8) | 2979 | νaCH3(C8) | 2978 | νsCH3(C11) | ||||||

| 2948w | 2968 | νaCH3(C8) | 2955 | νC4-H21 | 2962 | νaCH3(C11) | 2958 | νsCH3(C12) | ||||||

| 2962 | νaCH3(C11) | 2952 | νsCH3(C12) | 2953 | νC4-H21 | 2957 | νaCH3(C12) | 2956 | νsCH3(C11) | |||||

| 2938w,br | 2930sh | 2928 | νC4-H21 | 2947 | νsCH3(C11) | 2931 | νsCH3(C12) | 2974 | νaCH2 | 2945 | νsCH3(C8) | |||

| 2925 | νsCH3(C12) | 2926 | νsCH3(C11) | 2929 | νsCH3(C8) | 2933 | νsCH3(C8) | 2941 | νC4-H21 | |||||

| 2918 | νsCH3(C11) | 2913 | νsCH3(C8) | 2915 | νsCH2 | 2926 | νsCH2 | |||||||

| 2907sh | 2907 | νsCH3(C8) | 2908 | νsCH3(C8) | ||||||||||

| 2872sh | 2888sh | 2887sh | 2875 | νsCH2 | 2863 | νsCH2 | 2872 | νsCH2 | 2837 | νC4-H21 | 2894 | νsCH2 | ||

| 2824m | 2793 | νaCH3(C12) | 2820 | νsCH3(C12) | ||||||||||

| 2747m | 2782 | νaCH3(C11) | 2812 | νsCH3(C11) | ||||||||||

| 2673w | ||||||||||||||

| 2370s | 2508w | |||||||||||||

| 1688w | 1625 | νN3-H41 | 1713 | νN3-H41 | ||||||||||

| 1638vw | 1633w | 1630vw | 1600 | νC13-C17 | 1596 | νC13-C17 νC14-C18 |

1599 | νC14-C18 | ||||||

| 1596w | 1586w | 1581sh | 1581 | νC14-C18 | 1580 | νC14-C18 | 1581 | νC18-C20 νC17-C19 |

1584 | νC17-C19 νC18-C20 |

1581 | νC17-C19 νC15-C19 |

||

| 1558s | 1577 | νC13-C17 νC14-C18 |

1577 | νC14-C18 | 1578 | νC7-C14 | 1578 | νC13-C17 | ||||||

| 1573w | 1582sh | 1558s | 1561 | νC7-C14 | 1566 | νC17-C19 | 1564 | νC7-C14 | 1570 | νC17-C19 νC18-C20 |

1573 | νC18-C20 νC17-C19 |

1571 | νC7-C14 |

| 1558s | 1556 | νC13-C17 | 1558 | νC7-C14 | 1557 | νC13-C17 | ||||||||

| 1550w | 1552sh | 1550 | νC17-C19 νC18-C20 |

1554 | νC17-C19 | 1552 | νC17-C19 νC18-C20 |

1498 | ρN3-H41 | |||||

| 1489m | 1500w | 1489 | βC13-H33 βC16-H36 |

1486 | δaCH3(C8) | 1488 | βC14-H34 | |||||||

| 1480sh | 1483 | δaCH3(C8) | 1484 | δaCH3(C8) | 1480 | δaCH3(C8) | ||||||||

| 1466sh | 1470w | 1473 | ρN3-H41 | 1474 | δCH2 | 1478 | δaCH3(C12) | 1476 | δCH2 δaCH3(C8) |

|||||

| 1466sh | 1470w | 1470 | βC16-H36 βC14-H34 |

1471 | δaCH3(C11) δaCH3(C12) | 1473 | δaCH3(C8) | |||||||

| 1466sh | 1470w | 1469 | βC16-H36 βC14-H34 βC13-H33 |

1467 | βC15-H35 βC13-H33 βC14-H34 |

1468 | δaCH3(C8) | 1468 | δaCH3(C8) | |||||

| 1459vs | 1454sh | 1463 | δaCH3(C12) | 1463 | δaCH3(C11) | 1464 | δaCH3(C11) δaCH3(C12) | |||||||

| 1459vs | 1454sh | 1456 | δaCH3(C12) δaCH3(C11) |

1456 | δaCH3(C11) | 1458 | δaCH3(C11) | 1460 | βC14-H34 βC13-H33 |

1461 | δaCH3(C12) | |||

| 1459vs | 1454sh | 1452 | δaCH3(C11) | 1454 | δCH2 | 1455 | δCH2 | 1453 | δCH2 | 1454 | δCH2 | |||

| 1451sh | 1451 | δCH2 | 1451 | δaCH3(C12) | 1451 | δaCH3(C8) | 1450 | δaCH3(C12) | 1451 | δaCH3(C11) | 1449 | δaCH3(C11) | ||

| 1447sh | 1447sh | 1444 | δaCH3(C8) | 1446 | δaCH3(C8) δaCH3(C12) |

1449 | δaCH3(C11) | 1447 | βC20-H40 βC18-H38 |

1447 | βC20-H40 βC18-H38 |

|||

| 1447sh | 1447sh | 1440 | δaCH3(C8) | 1444 | δaCH3(C12) | 1442 | βC13-H33 | 1446 | βC20-H40 βC18-H38 |

1446 | βC19-H39 | 1446 | βC19-H39 | |

| 1433sh | 1438sh | 1437 | δaCH3(C12) δaCH3(C8) |

1440 | δCH2 | 1438 | δaCH3(C8) | 1444 | βC19-H39 | 1442 | δaCH3(C12) | 1443 | δaCH3(C11) δaCH3(C12) | |

| 1433sh | 1438sh | 1435sh | 1435 | δaCH3(C8) | 1432 | βC19-H39 | 1438 | δaCH3(C12) | ||||||

| 1430 | δaCH3(C12) | 1431 | βC20-H40 βC17-H37 |

1430 | βC20-H40 | 1435 | δsCH3(C12) δsCH3(C11) | |||||||

| 1429 | βC17-H37 βC19-H39 |

1429 | δaCH3(C11) δaCH3(C12) | 1429 | βC19-H39 | 1427 | δsCH3(C12) | 1425 | wagCH2 ρ′N3–H41 |

|||||

| 1421sh | 1427 | βC19-H39 | 1423 | δaCH3(C8) | 1426 | δaCH3(C12) | 1406 | wagCH2 | 1407 | wagCH2 | 1420 | wagCH2 | ||

| 1419sh | 1417 | δaCH3(C11) | 1411 | δsCH3(C12) | 1420 | δaCH3(C11) | 1400 | ρN3-H41 | 1408 | δsCH3(C11) | ||||

| 1408vw | 1403sh | 1406 | δsCH3(C11) | 1400 | δaCH3(C8) | 1408 | ρ′N3–H41 | 1402 | wagCH2 δsCH3(C11) |

1397 | δsCH3(C11) | 1401 | δsCH3(C12) | |

| 1390vw | 1395sh | 1392 | ρ′N3–H41 wagCH2 | 1394 | wagCH2 | 1394 | ρ′N3–H41 | |||||||

| 1378w | 1387w | 1388 | wagCH2 | 1381 | ρN3-H41 | 1376 | δsCH3(C11) δsCH3(C12) | 1375 | δsCH3(C8) ρ′C4–H21 |

1380 | δsCH3(C8) | 1379 | δsCH3(C8) | |

| 1364sh | 1374vw | 1376 | δsCH3(C12) | 1379 | δsCH3(C11) | 1360 | δsCH3(C8) | |||||||

| 1354w | 1362 | ρC4-H21 | 1361 | δsCH3(C8) | 1355 | νN3-H41 δsCH3(C12) |

1357 | δsCH3(C8) | 1350 | ρ′C4–H21 ρCH2 |

1356 | ρ′C4–H21 | ||

| 1342sh | 1347sh | 1340w | 1342 | δsCH3(C8) | 1349 | ρC4-H21 | 1351 | ρC4-H21 | ||||||

| 1334m | 1327sh | 1326sh | 1323 | ρ′C4–H21 | 1335 | ρ′C4–H21 | 1330 | ρC4-H21 νN2-C6 |

1327 | ρCH2 νN2-C6 |

||||

| 1320w | 1319 | ρCH2 νN2-C6 |

1320 | ρ′C4–H21 | 1318 | ρC4-H21 | 1320 | ρ′C4–H21 | 1313 | ρC4-H21 | ||||

| 1292sh | 1312sh | 1315sh | 1309 | νN2-C6 ρCH2 |

1307 | ρ′C4–H21 | 1315 | νN2-C6 | 1301 | νC6-C13 | 1300 | νC6-C13 | 1301 | νC6-C13 |

| 1285m | 1294s | 1296sh | 1286 | βC15-H35 νC16-C10 |

1282 | νC9-C15 νC6-C9 νC7-C10 |

1288 | βC15-H35 βC13-H33 |

||||||

| 1285m | 1294s | 1296sh | 1283 | νC6-C13 | 1282 | νC6-C13 | 1283 | νC6-C13 | 1285 | νC9-C15 νC6-C9 |

1286 | βC15-H35 | 1285 | νC16-C10 νC7-C10 νC6-C9 |

| 1270m | 1279sh | 1289m | 1273 | βC15-H35 νC16-C10 |

1274 | νC16-C10 νC9-C15 |

1275 | νC16-C10 | 1270 | νN3-C4 ρCH3(C12) |

||||

| 1274sh | 1267 | νC9-C15 νC6-C9 νC7-C10 |

||||||||||||

| 1256m | 1253sh | 1265 | νN3-C4 | 1264 | νC7-C10 νC6-C9 |

1266 | νC9-C15 νC7-C10 νC6-C9 |

1267 | ρCH2 | 1266 | ρCH2 | 1269 | ρCH2 βC16-H36 |

|

| 1249sh | 1247m | 1253 | ρCH2 | 1255 | ρCH2 βC16-H36 |

1260 | ρCH2 | |||||||

| 1228m | 1233sh | 1236sh | 1233 | νN2-C5 νN2-C7 |

1234 | νN2-C5 νN2-C7 |

1243 | νN2-C6 βC14-H34 νC7-C14 |

1248 | νN2-C5 νN2-C7 |

1242 | νN2-C6 | ||

| 1228m | 1223sh | 1228 | νN2-C6 | 1228 | ρ′CH3(C12) ρ′CH3(C11) |

1224 | νN3-C12 | 1226 | ρCH3(C12) | 1238 | ρCH3(C12) | |||

| 1218sh | 1208s | 1218w | 1217 | νN2-C7 | 1216 | ρ′CH3(C12) | 1221 | νN2-C7 | 1216 | ρ′CH3(C11) | 1223 | νN2-C7 | ||