Abstract

Background

HIV/AIDS is frequently associated with opportunistic diseases such as leishmaniasis. Hence, the co-infection HIV-Leishmania spp. is the result of the geographical overlap between leishmaniasis and HIV/AIDS cases. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the spatial distribution of HIV-Leishmaniasis co-infection in Morocco where both infections are endemic.

Methods

In the current study, we discuss the HIV-Leishmania spp. co-infection vulnerability in Morocco by using the cartography tools. Thus, epidemiological data of both infections (Leishmaniasis and HIV/AIDS) in different administrative regions of Morocco were collected and co-registered for Digital maps making.

Results & conclusion

The results showed a high risk of HIV-Leishmania infantum co-infection in northern and central regions in Morocco. These results should be taken into account for efficient control strategies and epidemiological surveillance of HIV –Leishmania spp. co-infection in Morocco.

Keywords: Biogeoscience, Bioinformatics, Ecology, Microbiology, Virology, Environmental health, Epidemiology, Public health, Infectious disease, HIV-AIDS, Leishmaniasis, Co-infection, Risk mapping, Morocco

1. Introduction

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and leishmaniasis are among the priority diseases of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2000).

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) responsible of AIDS, is now attacking the entire world and it is changing the society's future, particularly in developing countries (WHO, 2012). One of the essential characteristics of AIDS is its frequent association with opportunistic diseases, such as leishmaniasis (Lindoso et al., 2016). These opportunistic infections take advantage of a very weak immune system, or immunodeficiency caused by HIV, to occur more frequently and more severe diseases (Mofenson et al., 2009).

Leishmaniasis are a common parasitosis to humans and certain mammals. They are caused by flagellate protozoa of the genus Leishmania and transmitted by the bite of an infested sand fly (Diptera: Psychodidae) (Torres-Guerrero et al., 2017). Currently, leishmaniasis corresponds to a group of diseases comprising different clinical forms: visceral leishmaniasis, localized or diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis and cutaneous-mucous leishmaniasis (Scorza et al., 2017).

In Morocco, both infections exist and constitute a public health concern (Rhajaoui, 2011). The number of Moroccans living with HIV was estimated to be 32 000 in 2014 and the cumulative total number of HIV/AIDS cases reported from 1986 to 2014 was 10 017 (MMH, 2015a).

Regarding leishmaniasis, three Leishmania species representing two leishmaniasis forms (cutaneous CL and visceral leishmaniasis VL) co-occur in Morocco: Leishmania major, L. tropica and L. infantum. A total of 27 257 cases of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL by Leishmania major) was reported during the period of 2000–2013 with an annual incidence of 5000 cases per year (MMH, 2015b); followed by anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ACL by L. tropica) with 17 882 reported cases during the last 10 years (MMH, 2015b); while, an average of 150 cases of visceral leishmaniasis (VL by L. infantum) is annually recorded (Rhajaoui, 2011; MMH, 2015b).

Understanding and predicting patterns of HIV/AIDS-Leishmaniasis co-infection risk is an important component of an effective control campaign. Knowing that HIV- Leishmania spp. co-infection is the result of their geographical overlapping (Alvar et al., 2008), we determine here, the area with a high risk of HIV-Leishmania spp. co-infection for the first time in Morocco.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country located in North Africa, bordering the North Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Total population of Morocco is 33 million with a total of area of 710850 km2. The mean rate of urbanization recorded in Morocco is 61.9 % with differences according to regions (HCP, 2014).

2.2. Epidemiological data

In this retrospective study, digital maps were produced by matching the number of cases of leishmaniasis and HIV/AIDS. Epidemiological data were collected from the bulletins, registers and annual reports published by the local and national medical services; and completed from the local Ministry of Health offices, after official authorization from the regional delegations of Moroccan Ministry of Health.

2.3. Cartography

Arc Gis® software was used for mapping (Version 10.4), an information system designed to collect, store, process, analyze, manage and present spatial and geographic data.

3. Results & discussion

Cases of HIV-Leishmania co-infections have been reported in 33 countries, most of them were in southwestern Europe (France, Italy, Portugal and Spain) (Lindoso et al., 2016). In some parts of East Africa and India, large migration flows (refugees, seasonal workers) and certain at-risk populations (truck drivers, sex workers) are causing a growing overlap between the two diseases. In addition, the incidence of both diseases increased sharply in both regions, increasing the likelihood of co-infections (Desjeux and Alvar, 2003). This worrying situation prompted WHO/UNAIDS (WHO, 1998) to set up a global network for HIV-Leishmania co-infection.

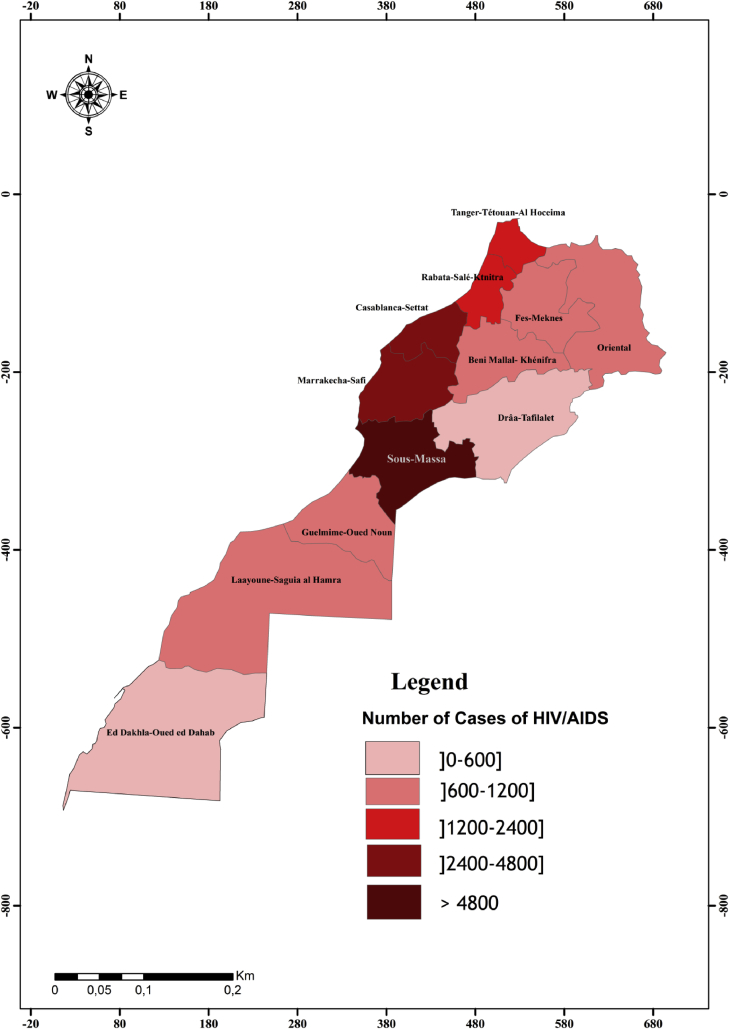

In Morocco, despite the high incidence of both leishmaniasis and HIV (Figs. 1 and 2) infections, to date, little is known about the Leishmaniasis – HIV/AIDS co-infection.

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of HIV/AIDS cases in Morocco.

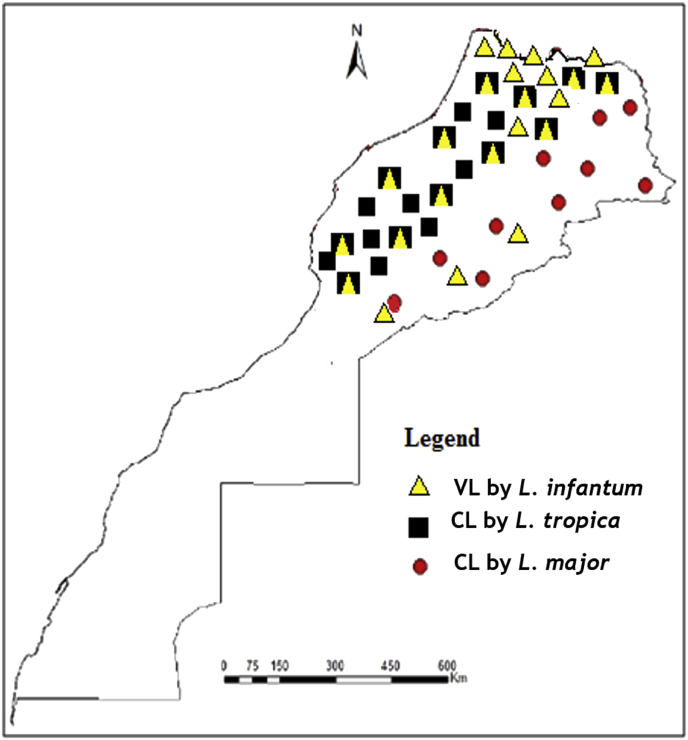

Fig. 2.

Geographical distribution of cutaneous (CL) and visceral (VL) leishmaniasis entities in Morocco.

Depending on the origin of the infection, leishmaniasis in Morocco can be grouped into three eco-epidemiological entities. Zoonotic Visceral Leishmaniasis (ZVL) and less frequently Zoonotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (ZCL) caused by L. infantum which is maintained in long term by dogs and bites of three vector species; Phlebotomus ariasi, P. perniciosus and P. longicuspis (Zarrouk et al., 2015). The Ministry of Health is still considering L. infantum as evolving sporadically mainly in northern Morocco (Fig. 2) with some 150 cases per year, while, many authors estimated that the VL incidence may be as high as 600 cases per year (Tachfouti et al., 2016). ZCL caused by L. major, where the parasite is maintained among small mammals and human by the bites of P. papatasi (Echchakery et al., 2015). ZCL has been known to exist in the vast arid pre-Saharan regions (Fig. 2). ACL caused by L. tropica and transmitted by the bites of P. sergenti. Human is the main host-reservoir with the possibility of zoonotic cycle (Echchakery et al., 2017). ACL has been known to occur mainly in north and central of Morocco were many foci were reported (Guessous-Idrissi et al., 1997; Ramaoui et al., 2008; Boussaa et al., 2009; Rhajaoui et al., 2012; Ajaoud et al., 2013).

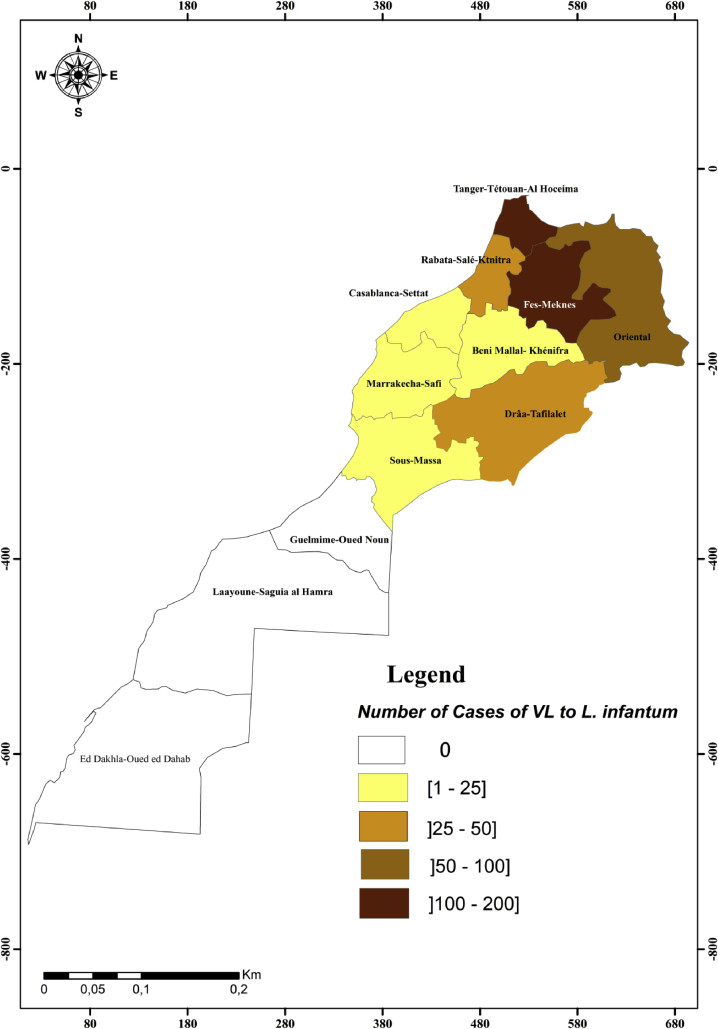

Currently, the change in the epidemiological trends of leishmaniasis was noted in Morocco with the spread of L. tropica and L. infantum to areas known until then as free and consequently, the overlap of the spatial distribution areas of the three Leishmania species (Hakkour et al., 2016; Hmamouch et al., 2017). Geographical distribution of our epidemiological data (Fig. 2) shows the widespread of L. infantum and L. tropica leishmaniasis in northern and central Morocco and confirms the overlapping of these two species in these areas. According to region, VL due to L. infantum is more marked in Fez-Meknes and Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima regions, followed by Oriental, Rabat-Sale-Kenitra and Draa-Tafilelt regions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Geographical distribution of cases of VL by L. infantum in Morocco.

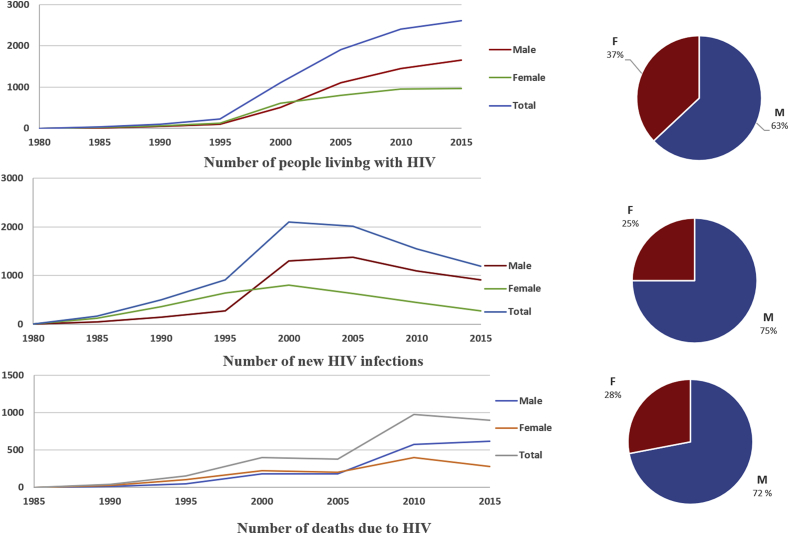

Regarding HIV infection, we noted the presence of the cases through Morocco. Sous-Massa and Marrakech-Safi are the most administrative regions concerned; with respectively, 24% and 18% of people living with HIV in Morocco (Fig. 1). The evolution of HIV/AIDS pandemic in Morocco between 1980 and 2015 shows an exponential increase (Fig. 4). The number of HIV/AIDS reported cases between 2009 and 2014 was 1312768 cases accounted for 51% cases of the total cases (MMH, 2015a).

Fig. 4.

Evolution of HIV-AIDS prevalence, incidence and lethality in Morocco by gender between 1980 and 2015 (MMH, 2015a).

70 % of the new infections would arise at the people the most exposed at the risk of the infection HIV or among their stable sexual partners. Men are more affected (63%) and the majority (73%) of the contaminated women is expected to be infected with the spouse (Fig. 4). The contamination of the man is in 92 % of the cases linked to the behavior at high risk (specially the multi-sexual partnership).

Among the notified cases, the heterosexual mode is the dominant mode of transmission (85.1 %), while the transfusional way is not clearly incriminated in the transmission of the HIV in Morocco (0.1 %). In contrast, the perinatal mode is responsible of 3.6 % of transmission proportion.

According to Alvar et al. (2008) the HIV-Leishmania spp. co-infection is the result of the geographical overlap between Leishmaniasis and AIDS cases. Thus, the cartography technique represents the geographical distribution of these two conditions in the different areas of Morocco. The superposition of the two maps, of leishmaniasis and HIV-AIDS, can identify the area at risk of HIV-Leishmania co-infection in Morocco.

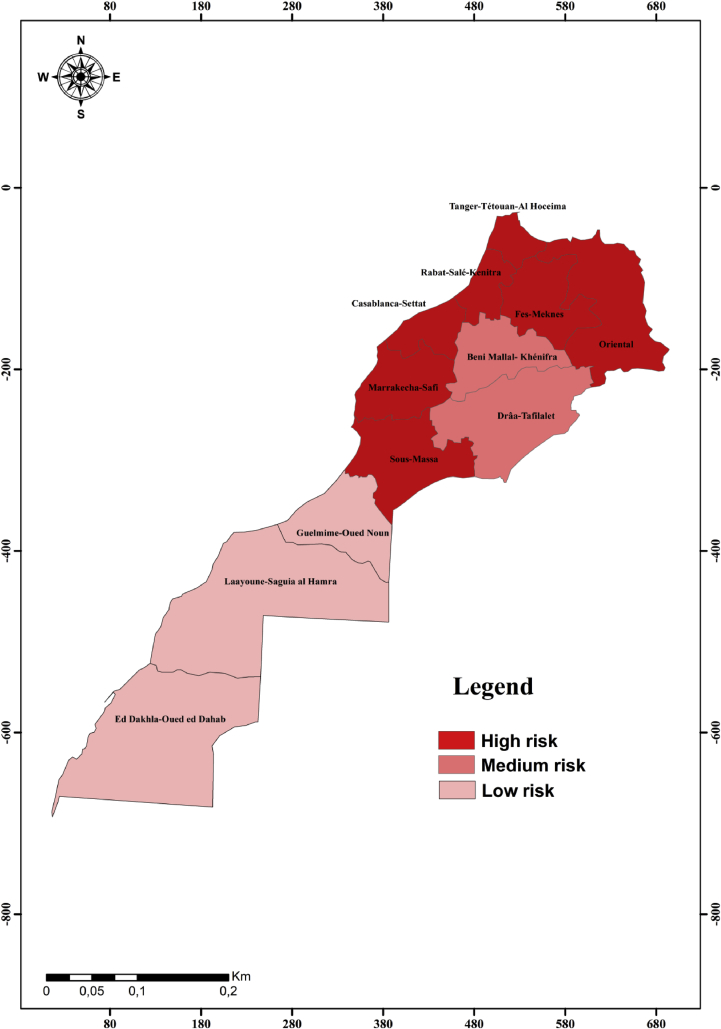

Consequently, seven regions out of twelve (Marrakech-Safi, Casablanca-Settat, Rabat-Sale-Kenitra, Fez-Meknes, Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima, Oriental and Sous Massa) are at high risk of HIV-Leishmania infantum VL co-infection (Fig. 5). These results are confirmed recently in Marrakech-Safi region where specific anti-L. infantum antibodies were detected in 5% of HIV-infected patients (Echchakery et al., 2018). Furthermore, canine L. infantum VL might contribute to increase the risk of HIV-VL coinfection. In Morocco, Canine leishmaniasis was reported in northern (Rami et al., 2003) as well as in central Morocco (Boussaa et al., 2014).

Fig. 5.

Map of vulnerability areas for HIV- Leishmania infantum co-infection in Morocco.

Majority of the mortality due to Leishmania spp. in the context of HIV co-infection arises from visceral leishmaniasis (Jarvis and Lockwood, 2013). CL-HIV co-infection is much less common than VL-HIV co-infection. In HIV infected patients, CL is characterized by several clinical forms: diffused cutaneous form, ulcerated form and pseudo lepromatous form (Jebbouri, 2013). Also, some atypical cutaneous leishmaniasis and the more severe mucocutaneous variants have been reported in HIV-infected patients (Ngouateu et al., 2012).

In Morocco, considerable clinic variability was noted in many CL foci in northern and central Morocco (Iguermia et al., 2011; Mouttaki et al., 2014) suggesting possible HIV-CL coinfection. In addition, HIV-CL co-infection case was recorded recently in Sous Massa region (Ouadia et al., 2016).

HIV-Leishmania co-infection is seemed to be linked to the urbanization process. According to WHO (2000), HIV-Leishmania spp. co-infection is favored by the spread of HIV/AIDS to rural areas and urbanization of leishmaniasis. HIV-AIDS is known as urban disease (Hall et al., 2010). In Morocco, 95% of HIV-AIDS patients reside in urban areas (MMH, 2015a), whereas, the urbanization of leishmaniasis is noted recently in Morocco, specially its anthroponotic cutaneous form (Boussaa et al., 2007) and visceral form (Kahime et al., 2017).

Co-existence of both HIV/AIDS and leishmaniasis in the same region increases the risk of both health problems (Alvar et al., 2008). That is alarming regarding the epidemiological role that can play the HIV-infected individuals as a reservoir host for leishmaniasis and that which Leishmania-infected patients can play in the development of HIV infection.

Indeed, the immunosuppressed individuals, including HIV-infected patients, present a higher risk of developing leishmaniasis than immunocompetent individuals (WHO, 2010). In addition, HIV-infected patients are known to be highly infectious to sand fly vectors (Monge-Maillo et al., 2014) because of the abundance of the parasite in their peripheral blood compared to immunocompetent patients (Desjeux et al., 2001). At the same time, leishmaniasis promotes the clinical progression of HIV disease and the development of AIDS-defining conditions (Alvar et al., 2008).

4. Conclusion

In the sum, northern and central Morocco have a very high risk of HIV-Leishmania spp. co-infection. The change in the epidemiological trends of leishmaniasis in Morocco can be explained by the overlap with major areas of HIV transmission; hence, the need to mobilize for the control and epidemiological surveillance of HIV-Leishmania co-infection in Morocco. This research provides a general overview of the incidence and risk of HIV-Leishmania co-infection in Morocco, the epidemiological significance of these results merits' future investigations.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Daoudi M: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Boussaa S: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Echchakery M: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Boumezzough A: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Ajaoud M., Es-sette N., Hamdi S., El-Idrissi A.L., Riyad M., Lemrani M. Detection and molecular typing of Leishmania tropica from Phlebotomus sergenti and lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis in an emerging focus of Morocco. Parasit. Vectors. 2013;6:217. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvar J., Aparicio P., Aseffa A., Den Boer M., Cañavate C., Dedet J.P. The relationship between leishmaniasis and AIDS: the second 10 years. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;(2):334–359. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00061-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa S., Kasbari M., El Mzabi A., Boumezzough A. Epidemiological investigation of canine leishmaniasis in Southern Morocco. Adv. Epidemiol. 2014;8 [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa S., Pesson B., Boumezzough A. Faunistic study of the sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in an emerging focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Al Haouz province, Morocco. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2009;103(1):73–83. doi: 10.1179/136485909X384910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa S., Pesson B., Boumezzough A. Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) of Marrakech city, Morocco. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2007;101:715–724. doi: 10.1179/136485907X241398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjeux P., Alvar J. Leishmania/HIV co-infections: epidemiology in Europe. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2003;(1):S3–S15. doi: 10.1179/000349803225002499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjeux P., Piot B., O'Neill K., MeertJP Co-infections à Leishmania/HIV dans le Sud de l'Europe. Med. Trop. 2001;61:187–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echchakery M., Nieto J., Boussaa S., El Fajali N., Ortega S., Souhail K. Asymptomatic carriers of Leishmania infantum in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in Morocco. Parasitol. Res. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00436-018-5805-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echchakery M., Chicharro C., Boussaa S., Nieto J., Carrillo E., Sheila O. Molecular detection of Leishmania infantum and Leishmania tropica in rodent species from endemic cutaneous leishmaniasisareas in Morocco. Parasit. Vectors. 2017;10:454. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2398-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echchakery M., Boussaa S., Kahime K., Boumezzough A. Epidemiological role of a rodent in Morocco: case of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2015;5(8):589–594. [Google Scholar]

- Guessous-Idrissi N., Hamdani A., Rhalem A., Riyad M., Sahibi H., Dehbi F. Epidemiology of human visceralleishmaniasis in Taounate, a northern province of Morocco. Parasite. 1997;4(2):181–185. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1997042181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkour M., Hmamouch A., El Alem M.M., Rhalem A., Amarir F., Touzani M. New epidemiological aspects of visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis in Taza, Morocco. Parasit. Vectors. 2016;9:612. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1910-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall I.H., Espinoza L., Benbow N., Hu Yunyin W. Epidemiology of HIV infection in large urban areas in the United States. PLoS One. 2010;5(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012756. Ed. Abdisalan M. Noor. PMC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High Commission for Planning (HCP) 2014. Note on the First Results of the General Census of Population and Housing. Morocco.http://goo.gl/6jquVC [Google Scholar]

- Hmamouch A., El Alem M.M., Hakkour M., Amarir F., Daghbach H., Habbari K. Circulating species of Leishmania at microclimate area of BoulemaneProvince, Morocco: impact of environmental and human factors. Parasit. Vectors. 2017;10:100. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2032-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguermia S., Harmouche T., Mikou O., Amarti A., Mernissi F.Z. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in Morocco, evidence of the parasite's ecological evolution. Med. Maladies Infect. 2011;41:47–48. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis J.N., Lockwood D.N. Clinical aspects of visceral leishmaniasis in HIV infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2013;26:1–9. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835c2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jebbouri Y. Mohammed Ben AbdallahUniversity; Fez: 2013. Epidemio-clinical, Therapeutic and Evolutionary Profile of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (About 52 Cases) [Google Scholar]

- Kahime K., Boussaa S., Nhammi H., Boumezzough A. Urbanization of human visceral leishmaniasis in Morocco. Parasit. Epidemiol. Contr. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindoso J.A.L., Cunha M.A., Queiroz I.T., Moreira C.H.V. Leishmaniasis–HIV coinfection: current challenges. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, N.Z.) 2016;(8):147–156. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S93789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mofenson L.M., Brady M.T., Danner S.P. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections among HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children: recommendations from CDC, the national institutes of health, the HIV medicine association of the infectious diseases society of America, the pediatric infectious diseases society, and the American academy of pediatrics. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2009;58(RR-11):1–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge-Maillo B., Norman F.F., Cruz I., Alvar J., López-Vélez R. Visceral leishmaniasis and HIV co-infection in the Mediterraneanregion. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroccan Ministry of Health (MMH) 2015. Implementation of the Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS.http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/MAR_narrative_report_2015.pdf National report. Morocco. [Google Scholar]

- Moroccan Ministry of Health (MMH) Directorate of Epidemiology and Disease Control; Rabat: 2015. A Report on Progress of Control Programs against Parasitic Diseases.http://www.sante.gov.ma/Publications/Etudes_enquete/Documents/04-2016/SANTE%20EN%20CHIFFRES%202014%20Edition%202015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mouttaki T., Morales-Yuste M., Merino-Espinosa G., Chiheb S., Fellah H., Martin-Sanchez J. Molecular diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis and identification of the causative Leishmania species in Morocco by using three PCR-based assays. Parasit. Vectors. 2014;7:420. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngouateu O.B., Kollo P., Ravel C. Clinical features and epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis and Leishmania major/HIVco-infection in Cameroon: results of a large cross sectional study. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012;106:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouadia Z., Akhdari N., Hocar O., Amal S., Tassi N. Polymorphic lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis revealing human immunodeficiency virus infection. Med. Maladies Infect. 2016;46(7):393–395. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaoui K., Guernaoui S., Boumezzough A. Entomological and epidemiological study of a new focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Morocco. Parasitol. Res. 2008;103:859–863. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rami M., Atarhouch T., Sabri M., Cadi Soussi M., Benazzou T., Dakkak A. Canine leishmaniasis in the Rif mountains (Moroccan Mediterranean Coast): sero-epidemiological survey. Parasite. 2003;10(1):79–85. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2003101p77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhajaoui M., Sebti F., Fellah H., Alam M.Z., Nasereddin A., Abbasi I. Identification of the causative agent of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Chichaoua province, Morocco. Parasite. 2012;19(1):81–84. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2012191081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhajaoui M. Human Leishmaniases in Morocco: a nosogeographical diversity. Pathol. Biol. 2011;59:226–229. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorza B.M., Carvalho E.M., Wilson M.E. Cutaneous manifestations of human and murine leishmaniasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(6):1296. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061296. Published 2017 Jun 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachfouti N., Najdi A., Alonso S., Sicuri E., Laamrani El Idrissi A., Nejjari C., Picado A. Cost of pediatric visceral leishmaniasis Carein Morocco. PLoS One. 2016;11(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Guerrero E., Quintanilla-Cedillo M.R., Ruiz-Esmenjaud J., Arenas R. Leishmaniasis: a review. F1000Res. 2017;6:750. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11120.1. Published 2017 May 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) World Health Organization; Geneva: 2012. UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2010. Control of the Leishmaniases. Report of a Meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Leishmaniases. Geneva (WHO/DOC/949) [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2000. Leishmania/HIV Co-infection in South-Western Europe 1990–1998: a Retrospective Analysis F 965 Cases.http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/230964/WER7444_365-375.PDF?sequence=1 Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 1998. Report on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic.http://data.unaids.org/pub/report/1998/19981125_global_epidemic_report_en.pdf Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrouk A., Kahime K., Boussaa S., Belqat B. Ecological and epidemiological status of species of the Phlebotomus perniciosus complex (Diptera: Psychodidae, Phlebotominae) in Morocco. Parasitol. Res. 2015;115:1045. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4833-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]