Abstract

Pregnancy poses an immunological challenge because a genetically distinct (nonself) fetus must be supported within the pregnant female for the required gestational period. Placentation, or the establishment of the fetally derived placenta, is a common strategy used by eutherian mammals to protect the fetus and promote its growth. However, the substantial morphological differences of the placental architecture among species suggest that the process of placentation results from convergent evolution. Although there are considerable similarities in placental function across placental mammals, there are important differences that arise owing to species-specific immunological (and other biological) constraints. This Review focuses on the immunological similarities and differences that occur at the maternal-fetal interface in the context of human and mouse pregnancies. We discuss how the decidua and placenta of these different species form key immunological barriers that sustain maternal tolerance yet generate innate immune responses that prevent microbial infections.

One Sentence Summary

The placenta promotes tolerance of the semi-allogeneic fetus while protecting against vertical transmission of infections.

Introduction

Placentation is a common strategy used across eutherian mammals to protect and promote fetal growth. Although mice are commonly used to study the maternal-fetal interface within the immunological context of pregnancy, differences exist in placental architecture, gestational period, and mechanisms of maternal tolerance from humans. Throughout this Review, we focus on the immunological similarities and differences during human and mouse pregnancies. We define the fetal and maternal components, their interactions, and mechanisms of mediating maternal tolerance in both species. We also examine the role of the placenta as a barrier to maternally transmitted pathogens and conclude with a discussion on the strengths and weaknesses of commonly used models of the human placenta.

The maternal-fetal interface in humans and mice

The maternal-fetal interface is composed of the maternally derived decidua and the fetally derived placenta (Fig. 1). In both mice and humans, the placenta develops from the trophectoderm of the blastocyst. During implantation, invading trophoblasts anchor the blastocyst to the specialized uterine epithelium (the decidua), on which placentation ensues. Over the course of pregnancy, the placenta is the sole site for all gas, nutrient, and waste exchange between the fetus and mother.

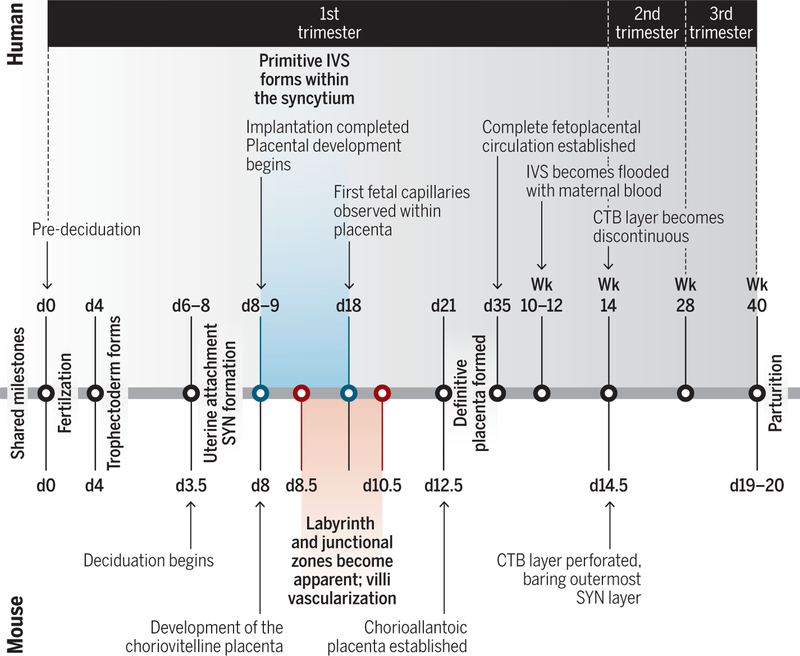

Fig. 1. Comparison of human and mouse placentation.

(Left) Before placentation, the blastocysts of humans and mice are similar. (Middle and right) However, upon implantation, placental development progresses differently. (Top middle) After blastocyst implantation, the human syncytiotrophoblast layer burrows into the maternal decidua. By the third week of gestation, the definitive human placenta is formed and is composed of villous trees. However, at this stage of human pregnancy, the fetal-derived placenta does not directly contact maternal blood. (Top right) Extravillous trophoblasts anchor the villi to the decidua and are involved in the remodeling of the spiral arteries to flood the intervillous space with maternal blood toward the end of the first trimester of pregnancy. The surface of the villi are covered by the syncytiotrophoblast layer, which directly contacts the maternal blood and facilitates the transport of nutrients, gases, and waste across the placental barrier. Underlying the syncytiotrophoblast layer are mononucleated cytotrophoblasts that can either fuse to replenish the syncytial layer or differentiate into extravillous trophoblasts. By contrast, mouse placental development and organization is different from that in humans. (Bottom middle) Upon implantation, the trophectoderm differentiates, and trophoblast giant cells encapsulate the developing mouse embryo. Halfway through gestation, the definitive mouse placenta is fully formed and functional, where (bottom right) the folded villi form a labyrinth structure that becomes perfused with maternal blood. The trophoblast giant cells channel maternal blood from the decidua through the spongiotrophoblast layer (a structure not present in the human placenta) toward the labyrinth zone. In the labyrinth zone, the maternal blood makes contact with the cytotrophoblasts that overlay two separate layers of syncytiotrophoblasts. Credit: A. Kitterman/Science Immunology

Decidua formation

The placenta is embedded within the decidua, the maternal component of the maternal-fetal interface. The decidua only exists during pregnancy and originates from the endometrial lining of the uterus (the endometrium). At the conclusion of pregnancy (parturition), the decidua is shed, to be rebuilt only upon subsequent pregnancy. However, signs of predecidualization can be observed within the nonpregnant human endometrium halfway through the luteal phase (around days 23 to 25 of the menstrual cycle), including increased prominence of the spiral arterioles, differentiation of endometrial fibroblast-like cells into enlarged and granulated decidual stromal cells, and an influx of leukocytes (1). Timing is critical for pregnancy to occur. Implantation must take place before this predecidualization because this thickening of the endometrium is not amenable for implantation.

During decidualization, there is both fetally and maternally mediated remodeling of the spiral arteries so that the placenta becomes bathed in maternal blood, which facilitates exchange of nutrients, gases, and waste. After implantation, the endothelial lining of the spiral arteries is eroded (as well as the local decidual stromal cells), creating a fibrinoid wall embedded with invasive fetal placental trophoblasts (2). Maternal leukocytes, such as natural killer cells and macrophages, have been implicated in this remodeling process. These concordant efforts of fetal trophoblasts and maternal leukocytes result in the dilation of the spiral arteries, which decreases the force and maximizes the volume of the maternal blood bathing the placenta (2).

Placenta development

In humans, the definitive structure of the placenta is composed of villous trees and is established by the third week of gestation (Fig. 1 and 2). The structure of the human placenta is composed of both floating and anchoring villi. A single layer of contiguous multinucleated syncytiotrophoblasts (SYN) lines the outermost surface of the human placenta villous trees and acts as the major cellular barrier between the fetal compartment and maternal blood. Underlying the SYN layer are the undifferentiated, mononucleated cytotrophoblasts (CTBs). CTBs are progenitor trophoblast cells and can fuse to replenish the SYN layer or differentiate into mononucleated extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs), which are located at the tips of the anchoring villi. During the first trimester, the human placenta is hemodichorial, with two layers of trophoblasts separating the fetal and maternal bloodstreams (the SYN and CTBs). As the placenta grows, the underlying CTB layer thins and becomes dispersed; thus, the human placenta of the second and third trimesters is essentially hemomonochorial, with only a single layer of SYNs.

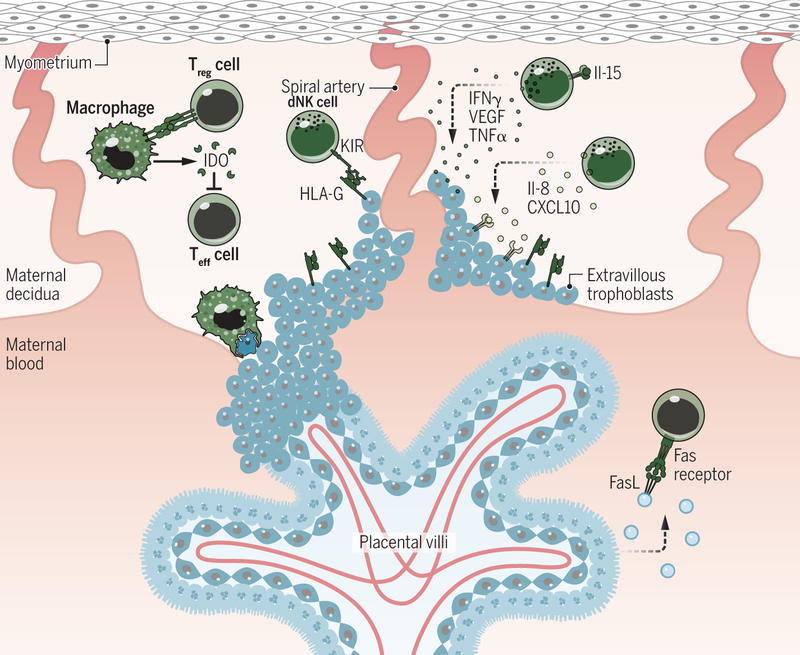

Fig. 2. Timeline of human and mouse placentation.

The human early blastocyst forms around day 4 and is marked by the development of the trophectoderm—the first differentiation event in mammalian development. The primitive intervillous space (IVS) forms around days 8 to 9 from the coalescence of vacuoles forming within the SYN mass (creating lacunae). In between the lacunae are columns of SYN (trabeculae), which are invaded by CTB around day 12 to form nascent villi. Around day 15, the CTB invade the decidua (a task previously performed by the SYN for implantation). By day 21, the definitive placenta is formed. However, maternal blood does not flood the IVS until weeks 10 to 12. By contrast, the gestational period of mice lasts just 20 days. Other differences between human and mice include the development of the choriovitelline placenta at day 8. This primitive placenta (not formed in human gestation) is composed of the juxtaposition of the yolk sac against the maternal tissues and blood vessels. At days 11 to 12.5, the yolk sac placenta is supplanted by the chorioallantoic (definitive) placenta, and around day 14.5 for the mouse, the CTB layer covering the villi becomes perforated, and maternal blood can now directly contact the outermost SYN layer. Credit: A. Kitterman/Science Immunology

The SYN facilitates the transport of nutrients, gases, and waste across the maternal-fetal interface. The SYN also functions as the main endocrine cell of the placenta, producing human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and progesterone, vital hormones that support pregnancy (3). During the first 8 weeks of gestation, the SYN secretion of hCG is required to induce progesterone production by the corpus luteum (4). Afterward, the placenta itself becomes the major producer of progesterone (4). Although the mouse also requires progesterone during the course of gestation, its placenta does not synthesize progesterone and instead continuously throughout pregnancy relies on the corpus luteum for progesterone (3).

EVTs physically anchor the human placenta to the decidua. The invasive EVTs also are important for remodeling the spiral arteries in the outer third of the myometrium. In the first trimester, EVTs act as a plug for the spiral arteries, thus creating a hypoxic environment by excluding the oxygen-rich maternal blood. During the transition from the first to the second trimester, the EVT plug is eroded, and the intervillous space (IVS) becomes flooded with maternal blood (Fig. 2). Later during gestation, the IVS can fill with as much as 150 mL of maternal blood. The presence of maternal blood in direct contact with the SYN allows for efficient gas, nutrient, and waste exchange, which is maintained throughout the rest of pregnancy. Because the direct contact of maternal blood with the placenta does not occur until the end of the first trimester, this event distinguishes the early (first trimester) and later (second and third trimesters) stages of pregnancy.

In the early stage of pregnancy, the IVS is filled with a clear fluid containing uterine gland secretions, which are phagocytosed by the SYN and serve as a nutrient source for the developing fetus (5). Uterine glands originate from invaginations of the endometrium and are required for establishing pregnancy. Among their varied secretions are growth factors that regulate placental development, including epidermal growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), and leukemia inhibitory factor (6).

Decidualization and placentation in the mouse

Key differences exist between mice and humans during the stages of pregnancy. In particular, the timeframe and establishment of the maternal-fetal interface in each species is distinct. Human gestation takes place over a period of 40 weeks, whereas in mice, it is approximately 3 weeks (Fig. 2). The timing of decidua formation and placentation also varies. In humans, the uterus is primed for decidualization, independent of fertilization, around menstrual cycle day 23 when the stromal cells near the (now prominent) spiral arteries begin to differentiate into large predecidual cells (1). However, in mice, spiral artery outgrowth and decidualization does not begin until fertilization and blastocyst attachment to the uterus, respectively (2). Likewise, the placenta does not have a definitive structure in mice until the midpoint of gestation (around day 10.5 to 11.5), whereas the definitive placenta in humans forms far earlier in relative development (around day 21) (3). Thus, timing is critical to experimental design and interpretation when using the mouse (or any other animal) to model human pregnancy. A timeline highlighting the differences between the human and mouse placentation and the key events that occur throughout pregnancy is shown in Fig. 2.

Although the hemochorial mouse placenta shares features with the human placenta, several differences exist that affect physiology, immunity, and development (Fig. 1). Whereas the human placenta is structured as villous trees bathed in maternal blood (after the first trimester), the mouse placenta has a labyrinth structure perfused by maternal blood. In the mouse, the maternal blood is directed through trophoblast giant cell-lined channels in the spongiotrophoblast layer (a cell type not present in the human placenta) to the chorionic plate and back through the labyrinth zone containing the fetal vasculature (7). Unlike the anchoring chorionic villi of humans, the mouse chorionic projections are highly interconnected, presenting a maze-like structure through which the maternal blood must pass to leave the placenta. This labyrinth chorionic structure is lined by three layers of trophoblasts: two layers of SYNs overlaid with CTBs. In further contrast to the human placenta, the mouse CTBs directly contact the maternal blood. The trophoblast giant cells (large polypoid cells) anchor the mouse placenta to the decidua. Unlike human EVTs, mouse giant cells are minimally invasive and do not remodel the maternal spiral arteries. These differences in physiology may affect the placental barrier functionally and the types of strategies used to protect the fetus from activation of the maternal immune system, as well as affect the pathways used by circulating pathogens to access the fetus.

Leukocytes at the maternal-fetal interface

In addition to stromal cells, a remarkably large portion (~40%) of the decidua is composed of maternal leukocytes (Fig. 3). In the first trimester, decidua basalis (the site of implantation and trophoblast invasion/remodeling), decidual natural killer (dNK) cells comprise the majority (~70%) of immune cells, followed by decidual macrophages (20 to 25%), and T cells (3 to 10%) (8, 9). Maternal leukocytes are present in the decidua throughout pregnancy, although the population frequencies change, with far more dNK cells and decidual macrophages present at earlier stages of pregnancy than at term (10, 11). These maternal leukocytes are recruited by chemokine gradients produced by decidual stromal cells and trophoblasts (12, 13) and are typically distinct from their peripherally circulating counterparts in phenotype and function. Most of our understanding of maternal leukocytes at the maternal-fetal interface has been determined from mouse studies and correlated to observations in human patient samples. Whereas the majority of the decidual leukocytes are dNK cells and decidual macrophages, T cell subsets also have key functions. More detailed information about leukocytes present at the maternal-fetal interface are available at (8, 9, 14).

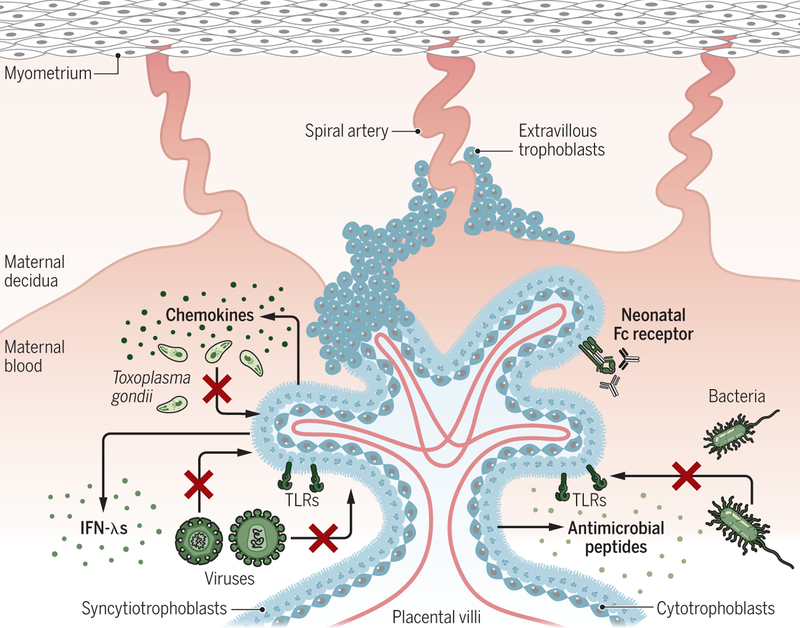

Fig. 3. Mechanisms of maternal tolerance.

The most abundant of the maternal immune cells present in the decidua are dNK cells, which are recruited by various factors released from the decidual stromal cells and placental trophoblasts. The release of uterine IL-15 promotes dNK maturation. The mature dNK cell promotes decidual remodeling and blastocyst implantation through the secretion of cytokines [including IFNγ, VEGF, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)]. The release of IL-8 and CXCL10 by dNK also promotes EVT invasion. dNK cell cytotoxicity is controlled by the binding of HLA-G (expressed on the EVTs) to the inhibitory receptor KIR2DL4. dMØ prevent maternal intolerance by producing IDO, which hinders T cell activation, and phagocytosing apoptotic trophoblasts. Treg cells modulate the activities of both APCs and effector T cells. The syncytiotrophoblast also promotes maternal tolerance by secreting exosomes expressing TRAIL and FasL and by the lack of any MHC expression. Credit: A. Kitterman/Science Immunology

dNK cells

dNK cells are the largest population of maternal leukocytes that accumulate at the maternal-fetal interface, where they contribute to decidualization and implantation. Unlike their circulating counterparts, dNK cells produce a vast array of growth factors, angiogenic factors, and cytokines (15). Through these secretions, they help to remodel the decidua and spiral arteries, promote trophoblast invasion, and increase the availability of maternal blood at the implantation site (15–19). In the mouse decidua, dilation of the spiral arteries is induced by dNK-secreted type II interferon (IFN-γ) (20). dNK production of interleukin-8 (IL-8) and CXCL10 has been implicated in promoting EVT migration into the placental bed (15). An absence of dNK cells in mouse pregnancies is associated with decreased fetus viability and abnormal formation of the decidual structure and spiral arteries at the implantation site (21, 22). Analogously, in human patients with unexplained infertility, endometrial biopsies have found substantially fewer NK cells than fertile counterparts (23). Interestingly, a subpopulation of dNK cells that exhibit enhanced production of IFN-γ and VEGFα has been identified recently as highly enriched in multigravid women (24). These pregnancy trained dNK (PTdNK) cells are transcriptionally distinct from other dNK cells, with higher expression of genes related to NK cell activation, growth factors, and immunomodulatory proteins (24). Using single-cell transcriptomics, another recent study identified three subsets of dNK cells in the first trimester decidua, including a highly active subset of dNK cells with characteristics similar to the previously described PTdNK cells (25). Because improved placentation is seen upon subsequent pregnancies (26), it is interesting to speculate that this subset of dNK cells may become enriched upon subsequent pregnancies and boost decidua receptivity.

The dNK cells of pregnancy are phenotypically distinct from the peripherally circulating NK cells, and their specific origins remain enigmatic and may differ between humans and mice (8). These cells are highly granulated and distinguished as CD56++CD16– (human) or CD122+CD3– (mouse) (8). The precursors of dNK cells are speculated to include the uterine hematopoietic stem cells and/or differentiation of thymic or peripheral NK cells (27–29), with the final differentiation into mature dNK cells driven, at least in part, by uterine IL-15 production (30). The size of the NK cell population in the uterus is regulated by endocrine signaling. Following the human menstrual cycle, there is a cyclic enrichment of NK cells in the uterus after ovulation that is sustained by pregnancy. By contrast, the population of NK cells in the mouse uterus does not accumulate until blastocyst implantation (8). In the mouse model of artificial decidualization, placement of an inert bead in the uterus of hormone-stimulated mice can stimulate local uterine NK to differentiate into dNK cells (31). However, these cells are not as functionally active as those derived in the presence of a conceptus (31).

Decidual macrophages

Decidual macrophages are the primary antigen presenting cells (APCs) at the maternal-fetal interface in early pregnancy (9). Like uterine NK cells, levels of uterine macrophages rise and fall with the menstrual cycle and then increase upon fertilization (32, 33). Phenotypically, decidual macrophages are believed to exist as regulatory/homeostatic, anti-inflammatory cells of an M2-like phenotype (9). The phenotype of decidual macrophages is believed to be influenced by trophoblasts, which secrete macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and IL-10 (34). Human decidual macrophages are CD163+CD206+DC-SIGN+ and predominantly express IL-10, CCL2, and CCL18 (35–40).

Decidual macrophages have many functions during pregnancy. Like dNK cells, they aid in remodeling of the spiral arteries and trophoblast invasion (41, 42) and localize to sites of disruption near the spiral arteries (43). Decidual macrophages in vitro produce VEGF and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), which may promote angiogenesis and tissue remodeling (38, 44, 45). Decidual macrophages are proposed to perform “cleanup” functions by phagocytosing apoptotic trophoblasts, which prevents activation of pro-inflammatory pathways in the decidua (46–49). These cells also produce indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO), which catabolizes tryptophan and hinders T cell activation (50, 51). Decidual macrophages also may have a more canonical antimicrobial role in protecting the fetus against infections, as suggested by the surface expression of pattern-recognition receptors CD163 (hemoglobin scavenger receptor), CD206 (mannose receptor), and CD209 (DC-SIGN) (52).

Regulatory T cells

The importance of regulatory T cells (Treg cells) in pregnancy has become increasingly apparent. Observational experiments with human samples demonstrate the presence of Treg cells in the human decidua, and cases of human infertility, recurrent spontaneous abortions, and other pregnancy complications have been inversely correlated with Treg cell frequencies or functionality (53–56). In mice, fetal specific Treg cells are recruited to and induced at the maternal-fetal interface, where they confer tolerance to fetal antigens and help maintain a homeostatic environment conducive to fetal survival. Fetal specific Treg cells are capable of persisting beyond parturition while maintaining their functionality (57). Upon subsequent pregnancy with the same paternal background, the expansion of these cells correlates with decreased fetal resorption (57). Intriguingly, the origins of these fetal-specific Treg cells may be linked to the in utero exposure of noninherited maternal antigens (NIMA). A multigenerational mouse study found pregnancies to be more successful when the sire has overlapping allogenicity with the maternal grandmother (58). Thus, in utero exposure to NIMA may expand a female’s Treg cell repertoire and explain the presence of maternal Treg cells specific for fetal (nonself) antigen (58).

Maternal tolerance

Maternal tolerance, which permits a mother to carry the fetus to term despite the presence of foreign fetal antigen, is a poorly understood phenomenon that seems to defy some of the basic tenets of immunology. For a successful pregnancy, maternal tolerance must be established, and failure of maternal tolerance is correlated with pre-eclampsia and miscarriage (59–61). In general, tolerance is mediated by the restriction and modulation of leukocytes that permeate the maternal-fetal interface. Although there is an abundance of NK cells in the decidua, the numbers of DCs and effector T cells are low. As has been demonstrated in the mouse decidua, this may be due to the absence of local lymphatic vasculature in the endometrium (62, 63) and epigenetic silencing of T cell chemoattractants in decidual stromal cells (64). As for leukocytes that do gain access to the maternal-fetal interface, intercellular communication between the resident decidual leukocytes, stromal cells, and trophoblasts can alter the functional profile of leukocytes and promote regulatory phenotypes. For example, first-trimester human placental explants produce G-CSF, IL-10, and TGF-β, which are known to promote differentiation of peripherally circulating monocytes and T cells into M2 MØ and Treg cells, respectively (34). Apoptosis also is used to mediate immune privilege. The SYN secretes exosomes that express TRAIL and Fas ligand on their surface, which are capable of binding to their cognate death receptors on leukocytes to trigger apoptosis (65).

Maternal tolerance also may occur through species-specific mechanisms. In humans, placental EVTs express HLA-G, a nonclassical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule, for which there is no homolog in the mouse genome. Unlike the canonical class I MHC molecules, of which exist thousands of allelic variations that serve to distinguish self from nonself, there are only 16 protein variants of HLA-G (66). Solely expressed by EVTs, HLA-G binds to dNK inhibitory receptors KIR2DL4 (67) and LILRB (68) to protect the trophoblasts from NK-mediated cytolysis (69). Likewise, the membrane-localized regulator of complement, Crry, is an example of a rodent-specific mechanism that protects the mouse placenta from the deposition and activation of circulating maternal complement, and its expression is required for fetal survival (70). Because Crry is rodent-specific, it remains to be determined whether the human placenta also expresses such complement regulatory proteins that inhibit complement deposition and activation. Such disparities in mediating maternal tolerance between mice and man may be due to differences in the degree of placental invasiveness and length of gestational period. Likewise, different mechanisms could have arisen independently to handle the same problem of maternal immune responses that antagonize fetal viability.

Intrinsic immune responses of the placenta

Once the IVS fills with maternal blood, the placenta is continuously exposed to any and all pathogens circulating systemically in the maternal circulation. As such, the placenta possesses several intrinsic defenses to protect the fetus from infection (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Mechanisms of placental immune defense.

The placenta has a number of innate immune mechanisms to protect the fetus from congenital infections of all types, including the expression of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), the constitutive expression of type III interferons (IFN-λ), and the release of antimicrobial peptides. Inoculation of placental trophoblasts with the parasite Toxoplasma gondii induces the secretion of chemokines, including the potent T helper 2 and Treg cell chemoattractant CCL22, suggesting that parasite infection alters or signals to maternal-derived immune cells. Furthermore, SYN expression of the neonatal Fc receptor also suggests a protective role for maternal IgG within the fetal compartment through the development of passive immunity. Credit: A. Kitterman/Science Immunology

Structure and location

The architecture of the human placenta allows it to present its strongest cellular defense, the SYN layer, on its outermost surface. The SYN forms a single continuous cell and thus lacks cellular junctions that can be exploited by pathogens or modulated by inflammatory signals. This contrasts with the mouse, which is arranged with the two layers of SYN buried beneath the CTBs contacting the maternal bloodstream. Another physical property that confers microbial resistance to the SYN is the dense cytoskeletal network that creates a dense brush-border formed at the apical surface. This brush border provides a vast surface area for nutrient and gas exchange between the maternal and fetal compartments but also protects from direct microbial invasion, in part because of the dense underlying actin network. For example, SYN are highly resistant to infection by Listeria monocytogenes (71) but become more permissive upon pharmacological disruption of the actin cytoskeleton (72). In addition, SYN restrict Toxoplasma gondii entry, most likely via a particular plasma membrane composition not amenable to parasite attachment (73, 74).

Secreted antiviral factors

The placenta secretes antiviral molecules that broadly function to restrict viral infections. The SYN layer constitutively secretes type III IFNs (IFN-λ) and vesicle-enclosed primate-specific placental microRNAs (miRNAs) (C19MC, chromosome 19 microRNA cluster) that restrict viral infections in autocrine and paracrine manners (75, 76). Whereas C19MC miRNAs are specific to primates, and it is unclear whether mice express an analogous inhibitory miRNA, the mouse placenta also uses type III IFNs to protect against viral infections. Mid-gestation mouse fetuses that lack IFN-λ signaling are more permissive to Zika virus (ZIKV) infection and vertical transmission (77). Likewise, injection of pregnant dams with pegylated IFN-λ restricted vertical transmission of ZIKV (77, 78).

Transport of passive immunity

The human placenta also can actively transport protective antibodies to the fetus via expression of the immunoglobulin G (IgG) receptors neonatal FcRn and FcɣRIII on the surface of the SYN layer. This transplacental passage of maternal humoral immunity in humans begins at week 16 of gestation and increases during the course of pregnancy so that at term, the fetus has a greater serum concentration of maternally derived IgG than does the mother (79). The mouse chorionic placenta does not transport IgG as efficiently; instead, mice acquire the bulk of maternal antibodies by way of FcRn expression on yolk sac–derived cells and after birth via suckling (80, 81).

Intracellular defenses

In addition to these processes, the placenta can directly initiate innate defenses aimed at suppressing microbial infections and/or alerting the maternal immune system to infection. Placental trophoblasts recognize pathogens via toll-like receptors and RIG-I–like receptors, which trigger the induction of antimicrobial signaling pathways (82, 83). Trophoblasts also exhibit high rates of basal autophagy, which can serve as a pan-antimicrobial strategy to restrict the replication of diverse intracellular pathogens (75, 84).

Modeling the maternal-fetal interface for studies on congenital infection

Despite the formidable barrier presented by the placenta, some pathogens are capable of overcoming these placental defenses and induce devastating consequences to the developing fetus. These pathogens are collectively referred to as TORCH pathogens with the acronym referring to Toxoplasma, Other [Zika virus, Listeria monocytogenes, Treponema pallidum, varicella zoster virus (VZV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and others], rubella virus, cytomegalovirus (HCMV), and herpes simplex virus. To understand how these pathogens cause fetal disease, it is important to consider routes of entry to the fetal compartment and methods of evading the intrinsic defenses and barriers of the maternal-fetal interface. Several different models have been used to study this evasion, including immortalized trophoblast cell lines, primary trophoblast cultures, human tissue explants, and in vivo models. Each model has advantages and limitations, which must be understood to interpret and extrapolate the conclusions to human pregnancy.

In vitro models to study human placental functions

BeWo, JEG-3, and JAR cells are commonly used tractable trophoblast cell lines derived from choriocarcinomas. Although these cell lines all express trophoblast markers, they do not spontaneously fuse to form syncytia and thus are more suited to model either CTBs or EVTs and do not recapitulate the biology of the SYN layer. Accordingly, these cell lines do not recapitulate the microbial resistance phenotypes observed in primary trophoblasts or placental explants (73, 75, 85). BeWo cells can be compelled to syncytialize by treatment with agents that increase adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) levels to enhance the expression of endogenous retrovirus fusion proteins responsible for CTB fusion (86); however, the elevation of intracellular cAMP levels can produce other phenotypes, and these cells still remain susceptible to microbial infection (73). In comparison, JEG-3 cells grown in a three-dimensional bioreactor-based system cocultured with human endothelial cells spontaneously fuse to form SYNs and are able to recapitulate resistance to T. gondii and viral infections, as well as the constitutive release of type III IFN-λ (85, 87). Primary human trophoblasts are excellent cellular models of CTBs and SYNs. However, the lack of efficient means to genetically manipulate these cells, coupled with their limited (usually 3 to 5 days) life span after isolation, limits their utility. Ex vivo placental explants maintain the distinct morphological structure of the placenta as well as the multicellular complexity and can be isolated at all stages of pregnancy (88). However, procurement of placentas from early to mid-gestation is complicated by increasingly restrictive government regulations. Several countries and states within the United States have illegitimized medical research that uses fetal-derived tissue, which includes the placenta, and other localities have limited access to tissues obtained from elective terminations.

In vitro models to study human decidual functions

While the above-mentioned models can provide valuable information regarding specific trophoblast-pathogen interactions and trophoblast-intrinsic immunity, they lack the maternal component. As with trophoblast models, there are a variety of different endometrial epithelial cell lines available for studies, with particular lines better suited as models for particular regions of the endometrium (such as glandular versus luminal models) (89). Primary stromal cells can be obtained and are capable of decidualizing in culture. Cocultures of endometrial stromal cells and trophoblasts are used to model implantation (90, 91). These models have limitations, including the exclusion of maternal immune cells that also compose up to 40% of the decidua. Studies using ex vivo decidual explants are able to model the multicellular composition (including dNK cells and decidual macrophages) and three-dimensional structure better, and recent congenital transmission studies using this model have provided insight into the decidual innate immune response and mechanisms of viral transmission (92, 93).

Animal models

Animal models are necessary to understand the dynamic immunological complexities of maternal-fetal tolerance, inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface, and the disruption of tolerance associated with congenital infections. Although a number of studies on placenta biology have come from experiments in mice, other animal models also have provided insights. Commonly used in vivo models include nonhuman primates (NHPs), sheep, and rodents (94). As might be expected, NHPs are good models for human pregnancy because there are many common characteristics, including a hemochorial placenta, singleton pregnancies, and a long gestation period comparable with that of human pregnancy (94). However, these models are ethically challenging, may be difficult to access or generate for some researchers, and are costly. Sheep also are commonly used to study placental vasculature because their villous trees are shaped similarly to that of humans (94). However, placentation is different in sheep; in particular, the depth of implantation is minimal (with no trophoblast invasion through the endometrial epithelium), and there is a greater degree of separation between the fetal and maternal vasculature (epitheliochorial placenta). Rodents, and specifically mice, are the most commonly used animal models. Among rodents, the guinea pig shares more similarities with human pregnancy than the mouse, including the source and levels of progesterone produced, deep trophoblast invasion, and long gestation (around three times the length of mouse gestation).

Nonetheless, the most commonly used animal model for studying congenital transmission is the mouse because it facilitates the use of many valuable immunological tools and techniques; has a short gestation period and large litter size, which enables a robust sample size; and is relatively inexpensive. Mouse models are particularly advantageous in the context of genetic deficiencies (on the maternal or fetal side of the interface), and results from these animal studies can be complemented with data from human models. The use of the mouse model for congenital infections has elucidated some of the mechanisms by which pathogens cause congenital disease. Experiments on Listeria-induced fetal wastage have demonstrated the importance of maintaining maternal tolerance toward the fetus; where promoting the accumulation of fetal-specific CD8+ T cells in the decidua causes fetal resorption, and most of the damage to the fetus is likely the result of a loss of maternal tolerance rather than the maternal response necessary to control the bacterial invasion (95). A similar phenomenon has been described in Salmonella-induced placental inflammation, in which the host response upsets the balance of maternal tolerance and leads to fetal loss (96).

However, when studying congenital infections, it is important to consider that many TORCH pathogens are species-specific, and mice may lack susceptibility. Each model must be interpreted carefully, keeping in mind its limitations. One example is the use of a mouse pathogen analogous to the human TORCH pathogen, such as the use of the mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) as a substitute for HCMV. However, MCMV cannot cross the placental barrier (unlike HCMV) (97). Another approach to overcome the barrier of host-specificity is the use of immunocompromised mice, such as studies on Zika virus that use mice lacking the receptor to type I interferon (77, 98, 99). Likewise, there also exists variability in both susceptibility and immune response between inbred strains of laboratory mice, as has been shown with Listeria (100). Notwithstanding these issues, mice are still a highly useful tool and have provided much insight on the complexity of the maternal immune response during congenital transmission.

Conclusions

Placentation is a common strategy used by eutherian mammals to generate a conduit and barrier between the maternal and fetal environments. The variety of strategies used to support placentation across the breadth of placental mammals is particularly interesting. Humans and mice both rely upon hemochorial placentas, but the structure and tissue organizations are distinct. Although the composition of the decidua is similar between mouse and human, the timing and mediators of decidualization are disparate. Through millions of years of evolution, each species has optimized the complex immunological equilibrium that is required to sustain a healthy pregnancy. Therefore, both the advantages and limitations of various models should be considered when extrapolating data to human congenital transmission and disease. Although no model is perfect, biological insights can be obtained through the continued use and development of in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo models. Collectively, these systems will provide new paradigms for one of the most distinct aspects of human biology and, potentially, strategies to protect the developing fetus from potentially devastating congenital disease.

Acknowledgments:

This work is supported by NIH grants R01 AI081759 (C.B.C.), R01 HD075665 (C.B.C.), R01 AI073755 (M.S.D.), R01 AI104972 (M.S.D.), R01 HD091218 (M.S.D.), and T32-AI049820 (S.E.A.); a Burroughs Wellcome Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award (C.B.C); and the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of the UPMC Health System (C.B.C.). We apologize to our colleagues whose studies could not be included because of space limitations.

References and Notes

- 1.Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J, Dating the Endometrial Biopsy, Fertil. Steril 1, 3–25 (1950). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Hanssens M, The Uterine Spiral Arteries In Human Pregnancy: Facts and Controversies, Placenta 27, 939–958 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malassine A, Frendo J-L, Evain-Brion D, A comparison of placental development and endocrine functions between the human and mouse model, Hum. Reprod. Update 9, 531–539 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuckey RC, Progesterone synthesis by the human placenta, Placenta 26, 273–281 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton GJ, Watson AL, Hempstock J, Skepper JN, Jauniaux E, Uterine Glands Provide Histiotrophic Nutrition for the Human Fetus during the First Trimester of Pregnancy, J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87, 2954–2959 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hempstock J, Cindrova-Davies T, Jauniaux E, Burton GJ, Endometrial glands as a source of nutrients, growth factors and cytokines during the first trimester of human pregnancy: A morphological and immunohistochemical study, Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol 2 (2004), doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamson SL, Lu Y, Whiteley KJ, Holmyard D, Hemberger M, Pfarrer C, Cross JC, Interactions between Trophoblast Cells and the Maternal and Fetal Circulation in the Mouse Placenta, Dev. Biol 250, 358–373 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manaster I, Mandelboim O, The Unique Properties of Uterine NK Cells, Am. J. Reprod. Immunol 63, 434–444 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu S, Diao L, Huang C, Li Y, Zeng Y, Kwak-Kim JYH, The role of decidual immune cells on human pregnancy, J. Reprod. Immunol 124, 44–53 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams PJ, Searle RF, Robson SC, Innes BA, Bulmer JN, Decidual leucocyte populations in early to late gestation normal human pregnancy, J. Reprod. Immunol 82, 24–31 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwan M, Hazan A, Zhang J, Jones RL, Harris LK, Whittle W, Keating S, Dunk CE, Lye SJ, Dynamic changes in maternal decidual leukocyte populations from first to second trimester gestation., Placenta 35, 1027–34 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlino C, Stabile H, Morrone S, Bulla R, Soriani A, Agostinis C, Bossi F, Mocci C, Sarazani F, Tedesco F, Santoni A, Gismondi A, Recruitment of circulating NK cells through decidual tissues: a possible mechanism controlling NK cell accumulation in the uterus during early pregnancy., Blood 111, 3108–15 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Zhu X-Y, Du M-R, Li D-J, Human trophoblasts recruited T lymphocytes and monocytes into decidua by secretion of chemokine CXCL16 and interaction with CXCR6 in the first-trimester pregnancy., J. Immunol 180, 2367–75 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nancy P, Erlebacher A, T cell behavior at the maternal-fetal interface, Int. J. Dev. Biol 58, 189–198 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, Hamani Y, Avraham I, Greenfield C, Natanson-Yaron S, Prus D, Cohen-Daniel L, Arnon TI, Manaster I, Gazit R, Yutkin V, Benharroch D, Porgador A, Keshet E, Yagel S, Mandelboim O, Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface, Nat. Med 12, 1065–1074 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saito S, Nishikawa K, Morii T, Enomoto M, Narita N, Motoyoshi K, Ichijo M, Cytokine production by CD16-CD56bright natural killer cells in the human early pregnancy decidua., Int. Immunol 5, 559–63 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C, Umesaki N, Nakamira H, Tanaka T, Nakatani K, Sakaguchi I, Ogita S, Kaneda K, Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor by granulated metrial gland cells in pregnant murine uteri, Cell Tissue Res 300, 285–293 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalkunte SS, Mselle TF, Norris WE, Wira CR, Sentman CL, Sharma S, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor C Facilitates Immune Tolerance and Endovascular Activity of Human Uterine NK Cells at the Maternal-Fetal Interface, J Immunol Ref 182, 4085–4092 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lash GE, Schiessl B, Kirkley M, Innes BA, Cooper A, Searle RF, Robson SC, Bulmer JN, Expression of angiogenic growth factors by uterine natural killer cells during early pregnancy, J. Leukoc. Biol 80, 572–580 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashkar AA, Croy BA, Interferon-gamma contributes to the normalcy of murine pregnancy., Biol. Reprod 61, 493–502 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guimond MJ, Wang B, Croy BA, Engraftment of bone marrow from severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice reverses the reproductive deficits in natural killer cell-deficient tg epsilon 26 mice., J. Exp. Med 187, 217–23 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmann AP, Gerber SA, Croy BA, Uterine natural killer cells pace early development of mouse decidua basalis, Mol. Hum. Reprod 20, 66–76 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klentzeris LD, Bulmer JN, Warren MA, Morrison L, Li TC, Cooke ID, Lymphoid tissue in the endometrium of women with unexplained infertility: morphometric and immunohistochemical aspects., Hum. Reprod 9, 646–52 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gamliel M, Goldman-Wohl D, Isaacson B, Gur C, Stein N, Yamin R, Berger M, Grunewald M, Keshet E, Rais Y, Bornstein C, David E, Jelinski A, Eisenberg I, Greenfield C, Ben-David A, Imbar T, Gilad R, Haimov-Kochman R, Mankuta D, Elami-Suzin M, Amit I, Hanna JH, Yagel S, Mandelboim O, Trained Memory of Human Uterine NK Cells Enhances Their Function in Subsequent Pregnancies, Immunity 48, 951–962.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vento-Tormo R, Efremova M, Botting RA, Turco MY, Vento-Tormo M, Meyer KB, Park J-E, Stephenson E, Polański K, Goncalves A, Gardner L, Holmqvist S, Henriksson J, Zou A, Sharkey AM, Millar B, Innes B, Wood L, Wilbrey-Clark A, Payne RP, Ivarsson MA, Lisgo S, Filby A, Rowitch DH, Bulmer JN, Wright GJ, Stubbington MJT, Haniffa M, Moffett A, Teichmann SA, Single-cell reconstruction of the early maternal–fetal interface in humans, Nature 563, 347–353 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prefumo F, Ganapathy R, Thilaganathan B, Sebire NJ, Influence of parity on first trimester endovascular trophoblast invasion, Fertil. Steril 85, 1032–1036 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vosshenrich CAJ, García-Ojeda ME, Samson-Villéger SI, Pasqualetto V, Enault L, Richard-Le Goff O, Corcuff E, Guy-Grand D, Rocha B, Cumano A, Rogge L, Ezine S, Di Santo JP, A thymic pathway of mouse natural killer cell development characterized by expression of GATA-3 and CD127., Nat. Immunol 7, 1217–24 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freud AG, Becknell B, Roychowdhury S, Mao HC, Ferketich AK, Nuovo GJ, Hughes TL, Marburger TB, Sung J, Baiocchi RA, Guimond M, Caligiuri MA, A human CD34(+) subset resides in lymph nodes and differentiates into CD56bright natural killer cells., Immunity 22, 295–304 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Heuvel M, Peralta C, Bashar S, Taylor S, Horrocks J, Croy BA, Trafficking of peripheral blood CD56(bright) cells to the decidualizing uterus–new tricks for old dogmas?, J. Reprod. Immunol 67, 21–34 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye W, Zheng LM, Young JD, Liu CC, The involvement of interleukin (IL)-15 in regulating the differentiation of granulated metrial gland cells in mouse pregnant uterus., J. Exp. Med 184, 2405–10 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herington JL, Bany BM, Effect of the Conceptus on Uterine Natural Killer Cell Numbers and Function in the Mouse Uterus During Decidualization, Biol. Reprod 76, 579–588 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunt JS, Miller L, Platt JS, Hormonal regulation of uterine macrophages., Dev. Immunol 6, 105–10 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulmer JN, Morrison L, Smith JC, Expression of class II MHC gene products by macrophages in human uteroplacental tissue., Immunology 63, 707–14 (1988). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Svensson-Arvelund J, Mehta RB, Lindau R, Mirrasekhian E, Rodriguez-Martinez H, Berg G, Lash GE, Jenmalm MC, Ernerudh J, The human fetal placenta promotes tolerance against the semiallogeneic fetus by inducing regulatory T cells and homeostatic M2 macrophages., J. Immunol 194, 1534–44 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svensson J, Jenmalm MC, Matussek A, Geffers R, Berg G, Ernerudh J, Macrophages at the fetal-maternal interface express markers of alternative activation and are induced by M-CSF and IL-10., J. Immunol 187, 3671–82 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Houser BL, Tilburgs T, Hill J, Nicotra ML, Strominger JL, Two unique human decidual macrophage populations., J. Immunol 186, 2633–42 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lidström C, Matthiesen L, Berg G, Sharma S, Ernerudh J, Ekerfelt C, Cytokine Secretion Patterns of NK Cells and Macrophages in Early Human Pregnancy Decidua and Blood: Implications for Suppressor Macrophages in Decidua, Am. J. Reprod. Immunol 50, 444–452 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gustafsson C, Mjösberg J, Matussek A, Geffers R, Matthiesen L, Berg G, Sharma S, Buer J, Ernerudh J, Unutmaz D, Ed. Gene Expression Profiling of Human Decidual Macrophages: Evidence for Immunosuppressive Phenotype, PLoS One 3, e2078 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laskarin G, Cupurdija K, Tokmadzic VS, Dorcic D, Dupor J, Juretic K, Strbo N, Crncic TB, Marchezi F, Allavena P, Mantovani A, Randic L, Rukavina D, The presence of functional mannose receptor on macrophages at the maternal-fetal interface., Hum. Reprod 20, 1057–66 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kämmerer U, Eggert AO, Kapp M, McLellan AD, Geijtenbeek TBH, Dietl J, van Kooyk Y, Kämpgen E, Unique Appearance of Proliferating Antigen-Presenting Cells Expressing DC-SIGN (CD209) in the Decidua of Early Human Pregnancy, Am. J. Pathol 162, 887–896 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bulmer JN, Williams PJ, Lash GE, Immune cells in the placental bed, Int. J. Dev. Biol 54, 281–294 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Renaud SJ, Graham CH, The role of macrophages in utero-placental interactions during normal and pathological pregnancy., Immunol. Invest 37, 535–64 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith SD, Dunk CE, Aplin JD, Harris LK, Jones RL, Evidence for Immune Cell Involvement in Decidual Spiral Arteriole Remodeling in Early Human Pregnancy, Am. J. Pathol 174, 1959–1971 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engert S, Rieger L, Kapp M, Becker JC, Dietl J, Kämmerer U, Profiling Chemokines, Cytokines and Growth Factors in Human Early Pregnancy Decidua By Protein Array, Am. J. Reprod. Immunol 58, 129–137 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hazan AD, Smith SD, Jones RL, Whittle W, Lye SJ, Dunk CE, Vascular-leukocyte interactions: mechanisms of human decidual spiral artery remodeling in vitro., Am. J. Pathol 177, 1017–30 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piacentini M, Autuori F, Immunohistochemical localization of tissue transglutaminase and Bcl-2 in rat uterine tissues during embryo implantation and post-partum involution., Differentiation 57, 51–61 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abrahams VM, Kim YM, Straszewski SL, Romero R, Mor G, Macrophages and Apoptotic Cell Clearance During Pregnancy, Am. J. Reprod. Immunol 51, 275–282 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M, The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization., Trends Immunol 25, 677–86 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abumaree MH, Chamley LW, Badri M, El-Muzaini MF, Trophoblast debris modulates the expression of immune proteins in macrophages: a key to maternal tolerance of the fetal allograft?, J. Reprod. Immunol 94, 131–41 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vacca P, Cantoni C, Vitale M, Prato C, Canegallo F, Fenoglio D, Ragni N, Moretta L, Mingari MC, Crosstalk between decidual NK and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells results in induction of Tregs and immunosuppression., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 11918–23 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grozdics E, Berta L, Bajnok A, Veres G, Ilisz I, Klivényi P, Jr JR, Vécsei L, Tulassay T, Toldi G, 3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression in peripheral blood of healthy pregnant and non-pregnant women,, 1–9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang M-X, Hu X-H, Liu Z-Z, Kwak-Kim J, Liao A-H, What are the roles of macrophages and monocytes in human pregnancy?, J. Reprod. Immunol 112, 73–80 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jasper MJ, Tremellen KP, Robertson SA, Primary unexplained infertility is associated with reduced expression of the T-regulatory cell transcription factor Foxp3 in endometrial tissue, Mol. Hum. Reprod 12, 301–308 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winger EE, Reed JL, Low Circulating CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T Regulatory Cell Levels Predict Miscarriage Risk in Newly Pregnant Women with a History of Failure, Am. J. Reprod. Immunol 66, 320–328 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arruvito L, Sanz M, Banham AH, Fainboim L, Expansion of CD4+CD25+and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle: implications for human reproduction., J. Immunol 178, 2572–8 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang TT, Chaturvedi V, Ertelt JM, Kinder JM, Clark DR, Valent AM, Xin L, Way SS, Regulatory T Cells: New Keys for Further Unlocking the Enigma of Fetal Tolerance and Pregnancy Complications, J. Immunol 192, 4949–4956 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rowe JH, Ertelt JM, Xin L, Way SS, Pregnancy imprints regulatory memory that sustains anergy to fetal antigen, Nature 490, 102–106 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kinder JM, Jiang TT, Ertelt JM, Xin L, Strong BS, Shaaban AF, Way SS, Cross-Generational Reproductive Fitness Enforced by Microchimeric Maternal Cells, Cell 162, 505–515 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kheshtchin N, Gharagozloo M, Andalib A, Ghahiri A, Maracy MR, Rezaei A, The Expression of Th1- and Th2-Related Chemokine Receptors in Women with Recurrent Miscarriage: the Impact of Lymphocyte Immunotherapy, Am. J. Reprod. Immunol 64, 104–112 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szarka A, Rigo JJ, Lazar L, Beko G, Molvarec A, Circulating cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia determined by multiplex suspension array, BMC Immunol 11, 59 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fisher SJ, Why is placentation abnormal in preeclampsia?, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 213, S115–S122 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Collins MK, Tay C-S, Erlebacher A, Dendritic cell entrapment within the pregnant uterus inhibits immune surveillance of the maternal/fetal interface in mice., J. Clin. Invest 119, 2062–73 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Red-Horse K, Stoddart CA, Fisher SJ, Red-horse K, Rivera J, Schanz A, Zhou Y, Winn V, Kapidzic M, Maltepe E, Okazaki K, Kochman R, Vo KC, Giudice L, Erlebacher A, Cytotrophoblast induction of arterial apoptosis and lymphangiogenesis in an in vivo model of human placentation, J. Clin. Invest 116, 2643–2652 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nancy P, Tagliani E, Tay C-S, Asp P, Levy DE, Erlebacher A, Chemokine gene silencing in decidual stromal cells limits T cell access to the maternal-fetal interface., Science 336, 1317–21 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stenqvist A-C, Nagaeva O, Baranov V, Mincheva-Nilsson L, Exosomes secreted by human placenta carry functional Fas ligand and TRAIL molecules and convey apoptosis in activated immune cells, suggesting exosome-mediated immune privilege of the fetus., J. Immunol 191, 5515–23 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ferreira LMR, Meissner TB, Tilburgs T, Strominger JL, HLA-G: At the Interface of Maternal–Fetal Tolerance, Trends Immunol 38, 272–286 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rajagopalan S, Long EO, A human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-G-specific receptor expressed on all natural killer cells., J. Exp. Med 189, 1093–100 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Apps R, Gardner L, Sharkey AM, Holmes N, Moffett A, A homodimeric complex of HLA-G on normal trophoblast cells modulates antigen-presenting cells via LILRB1, Eur. J. Immunol 37, 1924–1937 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chumbley G, King A, Robertson K, Holmes N, Loke YW, Resistance of HLA-G and HLA-A2 Transfectants to Lysis by Decidual NK Cells, Cell. Immunol 155, 312–322 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu C, Mao D, Holers VM, Palanca B, Cheng AM, Molina H, Kuo H, Zhou J, Jambeck P, A Critical Role for Murine Complement Regulator Crry in Fetomaternal Tolerance, Science (80-.) 287, 498–501 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robbins JR, Skrzypczynska KM, Zeldovich VB, Kapidzic M, Bakardjiev AI, Placental syncytiotrophoblast constitutes a major barrier to vertical transmission of Listeria monocytogenes, PLoS Pathog 6 (2010), doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zeldovich VB, Clausen CH, Bradford E, Fletcher DA, Maltepe E, Robbins JR, Bakardjiev AI, Wessels MR, Ed. Placental Syncytium Forms a Biophysical Barrier against Pathogen Invasion, PLoS Pathog 9, e1003821 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ander SE, Rudzki EN, Arora N, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB, Boyle JP, Human Placental Syncytiotrophoblasts Restrict Toxoplasma gondii Attachment and Replication and Respond to Infection by Producing Immunomodulatory Chemokines., MBiol 9, e01678–17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robbins JR, Zeldovich VB, Poukchanski A, Boothroyd JC, Bakardjiev AI, Tissue barriers of the human placenta to infection with Toxoplasma gondii, Infect. Immun 80, 418–428 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Delorme-Axford E, Donker RB, Mouillet J-F, Chu T, Bayer A, Ouyang Y, Wang T, Stolz DB, Sarkar SN, Morelli AE, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB, Human placental trophoblasts confer viral resistance to recipient cells., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 12048–53 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bayer A, Delorme-Axford E, Sleigher C, Frey TK, Trobaugh DW, Klimstra WB, Emert-Sedlak LA, Smithgall TE, Kinchington PR, Vadia S, Seveau S, Boyle JP, Coyne CB, Sadovsky Y, Human trophoblasts confer resistance to viruses implicated in perinatal infection., Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 212, 71.e1–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jagger BW, Miner JJ, Cao B, Arora N, Smith AM, Kovacs A, Mysorekar IU, Coyne CB, Diamond MS, Gestational Stage and IFN-λ Signaling Regulate ZIKV Infection In Utero., Cell Host Microbe 22, 366–376 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen J, Liang Y, Yi P, Xu L, Hawkins HK, Rossi SL, Soong L, Cai J, Menon R, Sun J, Outcomes of Congenital Zika Disease Depend on Timing of Infection and Maternal-Fetal Interferon Action, Cell Rep 21, 1588–1599 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maltepe E, Fisher SJ, Placenta: The Forgotten Organ, Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 31, 523–552 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim J, Mohanty S, Ganesan LP, Hua K, Jarjoura D, Hayton WL, Robinson JM, Anderson CL, FcRn in the yolk sac endoderm of mouse is required for IgG transport to fetus., J. Immunol 182, 2583–9 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Halliday R, Prenatal and Postnatal Transmission of Passive Immunity to Young Rats, Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B, Biol. Sci 144, 427–430 (1955). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bryant AH, Menzies GE, Scott LM, Spencer-Harty S, Davies LB, Smith RA, Jones RH, Thornton CA, Human gestation-associated tissues express functional cytosolic nucleic acid sensing pattern recognition receptors, Clin. Exp. Immunol 189, 36–46 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pudney J, He X, Masheeb Z, Kindelberger DW, Kuohung W, Ingalls RR, Differential expression of toll-like receptors in the human placenta across early gestation., Placenta 46, 1–10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cao B, Macones C, Mysorekar IU, ATG16L1 governs placental infection risk and preterm birth in mice and women, JCI Insight 1, e86654 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McConkey CA, Delorme-Axford E, Nickerson CA, Kim KS, Sadovsky Y, Boyle JP, Coyne CB, A three-dimensional culture system recapitulates placental syncytiotrophoblast development and microbial resistance., Sci. Adv 2, e1501462 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wice B, Menton D, Geuze H, Schwartz a L., Modulators of cyclic AMP metabolism induce syncytiotrophoblast formation in vitro., Exp. Cell Res 186, 306–316 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Corry J, Arora N, Good CA, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB, Organotypic models of type III interferon-mediated protection from Zika virus infections at the maternal-fetal interface., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 114, 9433–9438 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lowe DE, Robbins JR, Bakardjiev AI, Animal and Human Tissue Models of Vertical Listeria monocytogenes Transmission and Implications for Other Pregnancy-Associated Infections, Infect. Immun 86, e00801–17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hannan N, Paiva P, Dimitriadis E, Salamonsen L, Models for Study of Human Embryo Implantation: Choice of cell lines?, Biol. Reprod 82, 235–245 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Holmberg JC, Haddad S, Wünsche V, Yang Y, Aldo PB, Gnainsky Y, Granot I, Dekel N, Mor G, An in vitro model for the study of human implantation., Am. J. Reprod. Immunol 67, 169–78 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang H, Pilla F, Anderson S, Martinez-Escribano S, Herrer I, Moreno-Moya JM, Musti S, Bocca S, Oehninger S, Horcajadas JA, A novel model of human implantation: 3D endometrium-like culture system to study attachment of human trophoblast (Jar) cell spheroids, Mol. Hum. Reprod 18, 33–43 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weisblum Y, Panet A, Zakay-Rones Z, Vitenshtein A, Haimov-Kochman R, Goldman-Wohl D, Oiknine-Djian E, Yamin R, Meir K, Amsalem H, Imbar T, Mandelboim O, Yagel S, Wolf DG, Human cytomegalovirus induces a distinct innate immune response in the maternal-fetal interface, Virology 485, 289–296 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Weisblum Y, Oiknine-Djian E, Vorontsov OM, Haimov-Kochman R, Zakay-Rones Z, Meir K, Shveiky D, Elgavish S, Nevo Y, Roseman M, Bronstein M, Stockheim D, From I, Eisenberg I, Lewkowicz AA, Yagel S, Panet A, Wolf DG, Zika Virus Infects Early- and Midgestation Human Maternal Decidual Tissues, Inducing Distinct Innate Tissue Responses in the Maternal-Fetal Interface., J. Virol 91 (2017), doi: 10.1128/JVI.01905-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grigsby PL, Animal Models to Study Placental Development and Function thourghout Normal and Dysfucntional Human Pregnanct, Semin Reprod Med 34, 11–16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chaturvedi V, Ertelt JM, Jiang TT, Kinder JM, Xin L, Owens KJ, Jones HN, Way SS, CXCR3 blockade protects against Listeria monocytogenes infection-induced fetal wastage, J. Clin. Invest 125, 1713–1725 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chattopadhyay A, Robinson N, Sandhu JK, Finlay BB, Sad S, Krishnan L, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium-induced placental inflammation and not bacterial burden correlates with pathology and fatal maternal disease., Infect. Immun 78, 2292–301 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brizić I, Hiršl L, Britt WJ, Krmpotić A, Jonjić S, Immune responses to congenital cytomegalovirus infection, Microbes Infect, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yockey LJ, Jurado KA, Arora N, Millet A, Rakib T, Milano KM, Hastings AK, Fikrig E, Kong Y, Horvath TL, Weatherbee S, Kliman HJ, Coyne CB, Iwasaki A, Type I interferons instigate fetal demise after Zika virus infection., Sci. Immunol 3, eaao1680 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Miner JJ, Cao B, Govero J, Smith AM, Fernandez E, Cabrera OH, Garber C, Noll M, Klein RS, Noguchi KK, Mysorekar IU, Diamond MS, Zika Virus Infection during Pregnancy in Mice Causes Placental Damage and Fetal Demise., Cell 165, 1081–1091 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Abram M, Schlüter D, Vuckovic D, Wraber B, Doric M, Deckert M, Murine model of pregnancy-associated Listeria monocytogenes infection, FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol 35, 177–182 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]