Abstract

Background

Cryptosporidium spp. are causative agents of gastrointestinal diseases in a wide variety of vertebrate hosts. Mortality resulting from the disease is low in livestock, although severe cryptosporidiosis has been associated with fatality in young animals.

Methods

The goal of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to review the prevalence and molecular data on Cryptosporidium infections in selected terrestrial domestic and wild ungulates of the families Bovidae (bison, buffalo, cattle, goat, impala, mouflon sheep, sheep, yak), Cervidae (red deer, roe deer, white-tailed deer), Camelidae (alpaca, camel), Suidae (boar, pig), Giraffidae (giraffes) and Equidae (horses). Data collection was carried out using PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct and Cochran databases, with 429 papers being included in this systematic analysis.

Results

The results show that overall 18.9% of ungulates from the investigated species were infected with Cryptosporidium spp. Considering livestock species (cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses and buffaloes), analysis revealed higher Cryptosporidium infection prevalence in ungulates of the Cetartiodactyla than in those of the Perissodactyla, with cattle (29%) being the most commonly infected farm animal.

Conclusions

Overall, the investigated domestic ungulates are considered potential sources of Cryptosporidium contamination in the environment. Control measures should be developed to reduce the occurrence of Cryptosporidium infection in these animals. Furthermore, literature on wild populations of the named ungulate species revealed a widespread presence and potential reservoir function of wildlife.

Keywords: Cryptosporidiosis, Livestock, Cattle, Sheep, Goat, Pig, Horse, Wildlife

Background

Cryptosporidium, the causative agent of cryptosporidiosis, is an ubiquitous protozoan parasite. It causes gastrointestinal disease in a wide variety of vertebrate hosts, including ungulates of the orders Artiodactyla and Perissodactyla, as well as humans. Several Cryptosporidium species are known to be zoonotic with animals as major reservoirs [1]. In resource-limited settings, cryptosporidiosis is a leading cause of diarrhoeal death in children younger than five years across the globe, only second to rotaviral enteritis [2]. Cryptosporidiosis is also a significant contributor to health care cost in developed countries. It is estimated that in the USA 748,000 cases of human cryptosporidiosis occur annually [3]. Residents of and travelers to developing countries may be at greater risk of infection due to poor water treatment and food sanitation [4, 5]. Cryptosporidiosis typically induces self-limiting diarrhea in immunocompetent individuals, but the infection can be severe and life-threatening in immunocompromised subjects [6]. It is one of the most important diseases in young ruminants, especially neonatal calves [7, 8]. The clinical presentation of cryptosporidiosis varies from asymptomatic to deadly, leading to important economic losses due to growth retardation, reduced productivity and mortality [9, 10]. Considering that an infected bovine calf can shed up to 1.1 × 108 oocysts per gram of feces at the peak of the infection, cattle (and very likely wild ruminants) are significant contributors of environmental Cryptosporidium oocysts [11, 12], causing water-borne [13–15] and food-borne [16, 17] diarrhea outbreaks in humans worldwide. The worldwide annual excretion of Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts by livestock has been calculated to be 3.2 × 1023 [18], with cattle being the host species causing most environmental contamination. Cattle are able to carry different species including C. hominis which implies an associated significant public health risk [19]. In addition, Cryptosporidium oocysts are infective at the time they are passed in feces and are highly resilient to a wide range of environmental factors including disinfection and water treatment processes. Moreover, low infection doses are sufficient to cause disease in suitable hosts, e.g. 10‒100 oocysts are described to provoke diarrhea in humans [20, 21].

Over the past few decades, a major subject of debate and controversy in the epidemiology of Cryptosporidium is whether, and to what extent, domestic and wildlife species may act as natural reservoirs of human cryptosporidiosis [22, 23]. This is principally due to the fact that the genus Cryptosporidium encompasses nearly 40 valid species with marked differences in host range, among which over 10 (mainly C. hominis, C. parvum and C. meleagridis) have been reported in humans [24] with a variety of genotypes being zoonotic [1, 22, 25]. The public health significance of animal cryptosporidiosis varies greatly depending on factors such as geographical variation in prevalence and genotype distribution, seasonality, load of environmental contamination with oocysts and access to surface waters intended for human consumption or recreation [9, 26]. In particular, genotyping data from epidemiological surveys conducted globally indicate that infected calves are the major reservoir for zoonotic C. parvum in many areas [26, 27], with lambs, kids and foals being potential additional sources of C. parvum infection for humans in some areas of the world [28–31]. Pigs are only sporadically infected with zoonotic Cryptosporidium species and are therefore considered minor contributors to the zoonotic transmission of cryptosporidiosis in humans [32]. Adult livestock typically harbor low level and asymptomatic infections but are epidemiologically important as cryptic carriers of the parasite, enabling re-infections at the herd level. Little is known of the molecular epidemiology and transmission cycles of cryptosporidiosis in wild ungulates. However, recent surveys have revealed the presence of C. parvum in wild hoofed species including the American mustang (Equus ferus caballus) [33], Scottish roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and red deer (Cervus elaphus) [34], and Spanish wild boars (Sus scrofa scrofa) [35], which may represent a threat to water quality and public health [34].

In the present study, we conducted a systematic review of publications on the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infections and Cryptosporidium species distribution in domestic and wild ungulates in order to ascertain the extent to which hoofed animals should be considered as relevant reservoirs of human infection.

Methods

Search strategy

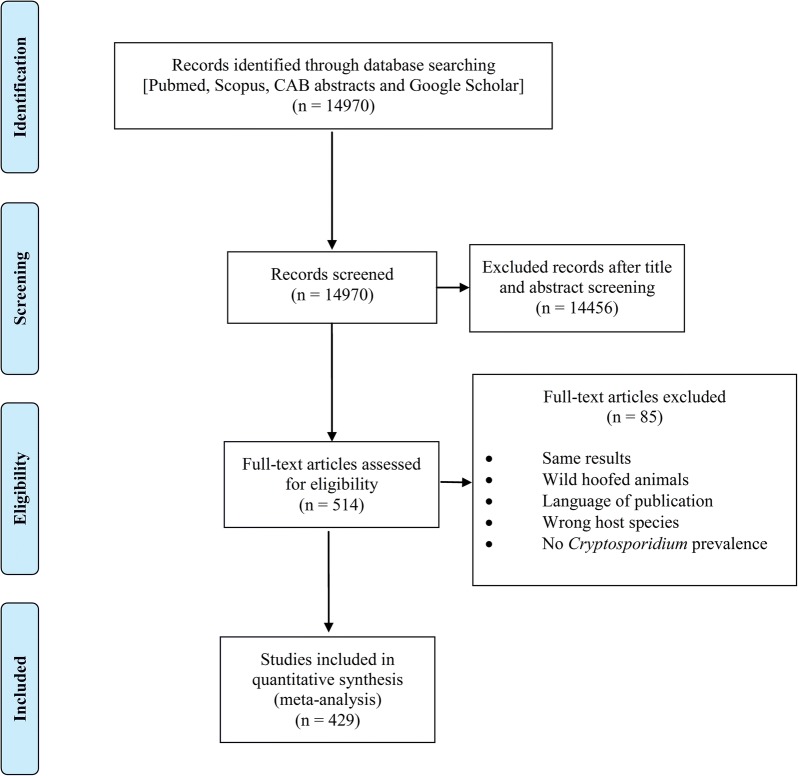

To evaluate the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in hoofed animals, we performed a comprehensive review of literatures (full text or abstracts) published online. English databases including PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct and Cochran were searched for publications related to Cryptosporidium infection of animals worldwide, from 1984 to 2016. We used the following MeSH terms alone or in combination: “Cryptosporidium” or “cryptosporidiosis” and “prevalence” and “livestock” or “cattle” or “buffaloes” or “sheep” or “pigs” or “camels” or “alpacas” or “horses” or “ruminants” or “wildlife”. To identify additional published articles, we used the PubMed option of “related articles” and checked the reference lists of the original and review articles. The more agricultural and veterinary focused database CAB abstracts was searched using the following search terms: “Cryptosporidium” or “cryptosporidiosis” and “prevalence” and “cattle” or “cows” or “calves” or “buffaloes” or “sheep” or “lambs” or “goats” or “kids” or “camels” or “alpacas” or “crias” or “llamas” or “pigs” or “piglets” or “horses” or “foals” or “deer” or “fawns” or “farm animals” or “ruminants” or “livestock” or “wildlife”. A protocol for the literature review was devised (Fig. 1) in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [36] (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram describing the paper selection process according to PRISMA guidelines

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

As part of the eligibility for inclusion, titles that suggested the topic Cryptosporidium in domestic and wild hoofed animals were selected. The abstracts from the selected reference titles were reviewed by two independent reviewers to determine if the studies met the inclusion criteria and, if so, the entire articles were reviewed in full. If more than one report was published from the same study, only one was included. Exclusion criteria included studies only on human cryptosporidiosis or case reports. Studies on epidemiology of Cryptosporidium spp. in groups unrelated to hoofed animals, or studies presenting overall prevalence estimates, where samples were collected from the ground, and data from each animal were not independently retrievable, were also excluded. The language of data collection was limited to English. In order to provide contemporaneous and representative estimates, studies were excluded if they presented data collected prior to 1984. On several occasions, we contacted the authors for the collection of raw data.

Data extraction and tabulation

A data extraction form was used to collect the following data from each study: first author, year of publication, location of study, period of study, host species, age range, clinical signs (diarrhoeic versus non-diarrhoeic), population nature (e.g. domestic, captive or wild), total number of fecal samples, utilized detection method (conventional microscopy, CM; immunofluorescence antibody test, IFA; enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, ELISA; immunochromatographic test, ICT; quantitative latex agglutination, QLAT; and polymerase chain reaction, PCR), number of Cryptosporidium-positive samples and identity of Cryptosporidium species and genotypes.

Retrieving sequences and phylogenetic analyses

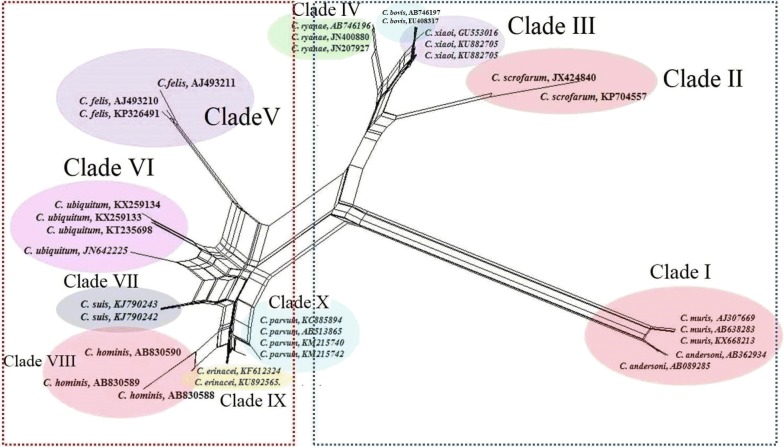

To examine the genetic relationships among Cryptosporidium spp. (C. hominis, C. felis, C. parvum, C. erinacei, C. xiaoi, C. ryanae, C. scrofarum, C. muris, C. andersoni, C. ubiquitum, C. bovis and C. suis) in ungulates, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the program Splits Tree v.4.0 based on the Neighbor-Net method and Median-Joining analysis of sequences of the 18S rRNA gene [37]. For this purpose, the sequences of the 18S rRNA gene of these Cryptosporidium spp. were retrieved from the GenBank database in the FASTA format. These sequences were initially obtained from various herbivores, including cattle, buffaloes, yaks, camels, goats, sheep and deer, as well as pigs.

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis was performed for studies describing Cryptosporidium infection prevalence in domestic animals that are common in many parts of the world, i.e. cattle, sheep, goats, buffaloes, horses and pigs. This analysis was performed to enhance knowledge on the potential role of livestock in zoonotic Cryptosporidium transmission since these animals feature a close contact to humans. The pooled prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection as well as its 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for each study. A forest plot was generated to display the summarized results and heterogeneity among the included studies. To ensure comparable sensitivity of tests used in analyzed studies, only results from studies based on PCR as a diagnostic method were included. Studies using PCR methods only for molecular Cryptosporidium species/genotype identification but utilizing alternative diagnostic methods to determine prevalence were not included. The heterogeneity was expected in advance and statistical analyses including I2 and Cochrane’s Q test (with a significance level of P < 0.1) were used to quantify these variations. The meta-analysis considering the random effects model [38] was performed using the Stats Direct statistical software (http://www.statsdirect.com).

Results

The initial database search retrieved 14,970 publications. The screening of these records enabled us to exclude 14,456 studies due to not meeting the inclusion criteria. Altogether, 514 studies were retained for further investigation. During the secondary assessment of these papers, another 85 were excluded because of one of the following reasons: other host species including wild hoofed animals; report of the same results as another paper published by the same author; and language of publication (e.g. Chinese, Spanish, etc.). Papers evaluating cryptosporidiosis in camels, yaks, donkeys, alpacas and llamas were excluded in the secondary analysis of data, as the meta-analysis focused on Cryptosporidium infection in cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, buffaloes and horses. Eventually, 429 studies which evaluated Cryptosporidium infection during three decades met our eligibility criteria and were retained for analysis (Fig. 1).

Different diagnostic procedures were used for the detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts to a varying extent in the different studies. The included publications featured CM examination (n = 371), IFA (n = 107), ELISA (n = 25), ICT (n = 9), quantitative latex agglutination (QLAT) (n = 1) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (n = 99) (Additional file 2: Table S2).

In total, 196,638 stool samples from Artiodactyla and Perissodactyla ungulates were evaluated, of which 37,206 (18.9%) subjects were positive for Cryptosporidium infection. Among the 196,638 stool samples, 90,744 were associated with the domestic hoofed animals (including camels, yaks, donkeys, alpacas and llamas), displaying a Cryptosporidium infection prevalence of 13.6% (n = 12,377) (Table 1 and Additional file 2: Table S2).

Table 1.

Summarized Cryptosporidium prevalence data for major domestic farmed animals. Data for wild populations of the given species not included (see for full datasets and other host species in Additional file 2: Table S2)

| Host species | Region | No. of studies | Utilized diagnostic methods | Retrieved minimum prevalence (%) | Retrieved maximum prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) | Africa | 6 | CM, PCR | 1.3 (CM) | 52.0 (CM) |

| Asia | 16 | CM, ICT, PCR | 3.6 (CM) | 50.0 (CM) | |

| Australia | 2 | PCR | 13.1 (PCR) | 30.0 (PCR) | |

| Europe | 1 | ELISA | 14.7 (ELISA) | ||

| South America | 2 | CM, PCR | 9.4 (CM) | 48.2 (PCR) | |

| Cattle (Bos taurus) | Africa | 29 | CM, ELISA, PCR | 0.5 (CM) | 86.7 (CM) |

| Asia | 74 | CM, ICT, IFA, PCR | 1.5 (CM) | 93.0 (CM) | |

| Australia | 7 | CM, IFA, PCR | 3.6 (IFA) | 73.5 (PCR) | |

| Europe | 60 | CM, ELISA, ICT, IFA, PCR, QLAT | 0.0 (CM) | 71.7 (CM) | |

| New Zealand | 5 | CM, IFA | 2.6 (IFA) | 21.2 (CM) | |

| North America | 29 | CM, IFA, PCR | 1.1 (IFA) | 78.0 (CM) | |

| South America | 11 | CM, ICT, PCR | 3.0 (CM) | 56.1 (CM) | |

| Goat (Capra hircus) | Africa | 10 | CM, ELISA | 0.0 (CM) | 76.5 (ELISA) |

| Asia | 15 | CM, ICT, IFA | 0.0 (IFA) | 42.9 (CM) | |

| Australia | 1 | PCR | 4.4 (PCR) | ||

| Europe | 22 | CM, ELISA, IFA | 0.0 (CM) | 93.0 (IFA) | |

| North America | 3 | CM | 20.0 (CM) | 72.5 (CM) | |

| South America | 3 | CM | 4.8 (CM) | 100 (CM) | |

| Sheep (Ovis aries) | Africa | 10 | CM, ELISA, PCR | 1.3 (CM) | 41.8 (ELISA) |

| Asia | 17 | CM, ELISA, ICT, PCR | 1.8 (CM) | 66.6 (CM) | |

| Australia | 7 | PCR | 2.2 (PCR) | 81.3 (PCR) | |

| Europe | 22 | CM, IFA, ELISA | 1.4 (CM) | 100.0 (CM) | |

| North America | 9 | CM, IFA, PCR | 20.0 (CM) | 77.4 (PCR) | |

| South America | 5 | CM, PCR | 0.0 (CM) | 25.0 (PCR) | |

| Pig (Sus scrofa) | Africa | 5 | CM, ELISA, IFA, PCR | 13.6 (CM) | 44.9 (ELISA) |

| Asia | 13 | CM, IFA, PCR | 0.4 (IFA) | 55.8 (PCR) | |

| Australia | 3 | CM, PCR | 0.3 (CM) | 22.1 (PCR) | |

| Europe | 13 | CM, IFA, PCR | 0.1 (CM) | 40.9 (IFA) | |

| North America | 6 | CM, IFA | 2.8 (ns) | 19.6 (CM) | |

| South America | 3 | CM, PCR | 0.0 (CM) | 2.2 (PCR) | |

| Horse (Equus caballus) | Africa | 3 | CM, PCR | 0.0 (CM) | 2.9 (PCR) |

| Asia | 7 | CM, PCR | 2.7 (PCR) | 37.0 (CM) | |

| Europe | 10 | CM, ELISA, IFA, PCR | 3.4 (PCR) | 25.0 (IFA) | |

| New Zealand | 2 | CM | 18.0 (CM) | 83.3 (CM) | |

| North America | 6 | CM, IFA, PCR | 0.0 (IFA/PCRa) | 17.0 (IFA) | |

| South America | 7 | CM | 0.0 (CM) | 100.0 (CM) | |

aMultiple studies revealed the same prevalence data

Abbreviation: ns, not stated

All subsequent analyses included only the studies that focused on Cryptosporidium infection in cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, buffaloes and horses (n = 429). Among them, 201 provided data on cattle, 66 on sheep, 55 on goats, 39 on pigs, 37 on horses and 28 on buffaloes (Additional file 2: Table S2).

A total of 105,894 samples from 245 studies on common livestock, defined as cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses and buffaloes, were examined for Cryptosporidium infection, with 24,829 (23.4%) being positive for Cryptosporidium spp. using CM and PCR methods. Most of the studies were conducted on cattle (n = 163) and sheep (n = 46).

The pooled prevalence rates using the CM method were 22.5% (95% CI: 19.6–25.6%), 20.7% (95% CI: 15.2–26.8%), 18.7% (95% CI: 12.36–26.2%), 15.5% (95% CI: 10.5–21.3%), 13.8% (95% CI: 6.6–22.9%) and 18.6% (95% CI: 11.1–27.4%) for cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses and buffaloes, respectively (Table 2). The pooled prevalence rates using the PCR method were 29.1% (95% CI: 23.1–35.6%), 24.4% (95% CI: 16.4–33.4%), 8.2% (95% CI: 3.7–14.3%), 22.6% (95% CI: 13.7–33%), 4.7% (95% CI: 2–8.4%) and 26.0% (95% CI: 12.2–42.8%) for cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses and buffaloes, respectively (Table 2). Analysis of available data by regions (continents and New Zealand) showed a moderate geographical variation of observed prevalence (Table 1). Although diagnostic tests varied among regions, the observed prevalence mostly fell within the 5–30% range (Table 2). Regarding cattle, a considerably lower maximum prevalence was seen in New Zealand compared to other regions. Cryptosporidium prevalence in goat tended to be lower in Asia; however, only one study was available for Australia. For sheep it was the highest in the regions with most intensive sheep production, i.e. Australia, Europe and North America (Table 1). Cryptosporidium prevalence in pigs was the highest in Asia, Africa and Europe. In horses, studies in South America reported the highest Cryptosporidium prevalence.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of Cryptosporidium infection prevalence in domestic ungulates using CM and PCR methods

| Method/host | CM | PCR | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled (%) | OR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity | Publication bias | Pooled (%) | OR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity | Publication bias | |||||

| Q statistic | df | I2 (%) | Egger bias (P-value) | Q statistic | df | I2 (%) | Egger bias (P-value) | |||||

| Cattle | 22.5 | 19.6–25.6 | 11,038.9 | 127 | 98.8 | 10.51 (P < 0.0001) | 29.1 | 23.1–35.6 | 1591.1 | 34 | 97.9 | 11.52 (P < 0.0001) |

| Sheep | 20.7 | 15.2–26.8 | 1391.9 | 30 | 97.8 | 6.77 (P = 0.0086) | 24.4 | 16.4–33.4 | 916.7 | 14 | 98.5 | 8.18 (P = 0.014) |

| Goat | 18.7 | 12.36–26.2 | 1852.1 | 28 | 98.5 | 9.01 (P = 0.0004) | 8.2 | 3.7–14.3 | 11.2 | 2 | 82.2 | – |

| Pig | 15.5 | 10.5–21.3 | 1545.4 | 21 | 98.6 | 12.42 (P = 0.0485) | 22.6 | 13.7–33.0 | 99.8 | 5 | 95.0 | 2.36 (P = 0.6452) |

| Horse | 13.8 | 6.6–22.9 | 621.6 | 16 | 97.4 | 6.71 (P = 0.0002) | 4.7 | 2.0–8.4 | 22.5 | 4 | 82.3 | 3.67 (P = 0.0452) |

| Buffalo | 18.6 | 11.1–27.4 | 991.4 | 17 | 98.3 | 8.76 (P = 0.0004) | 26.0 | 12.2–42.8 | 152.4 | 4 | 97.4 | 9.28 (P = 0.1434) |

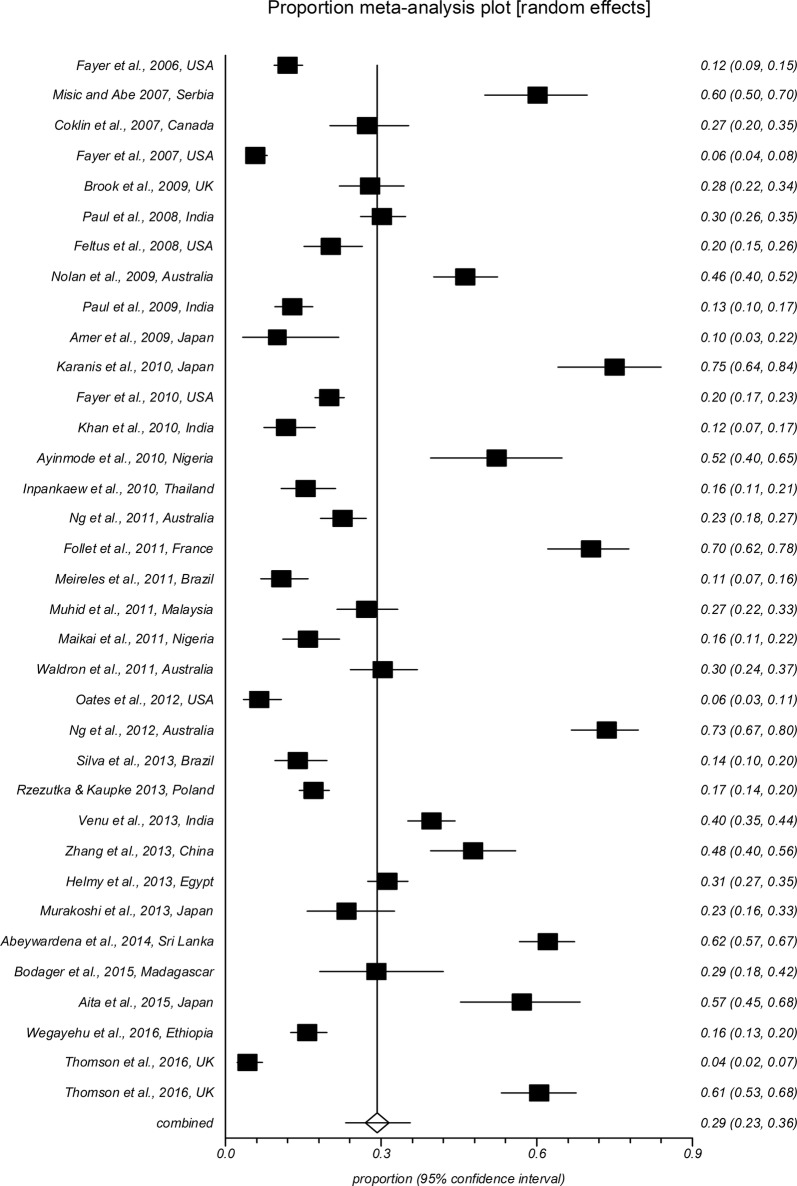

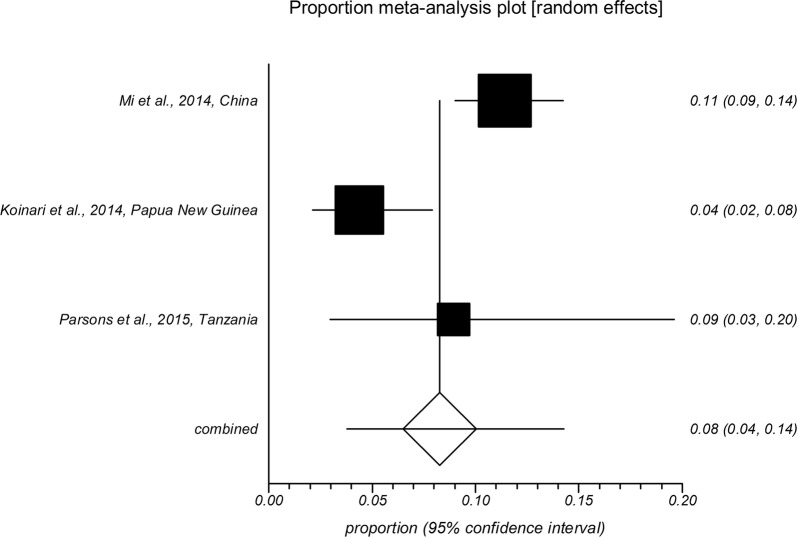

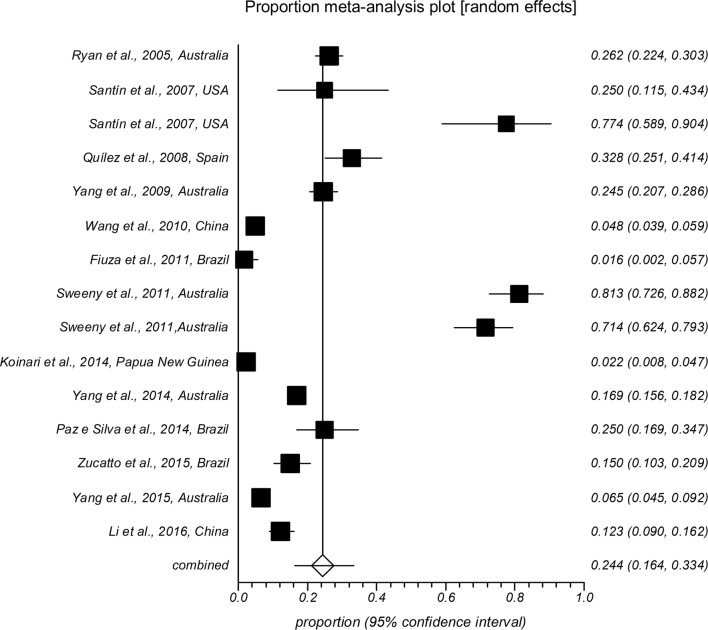

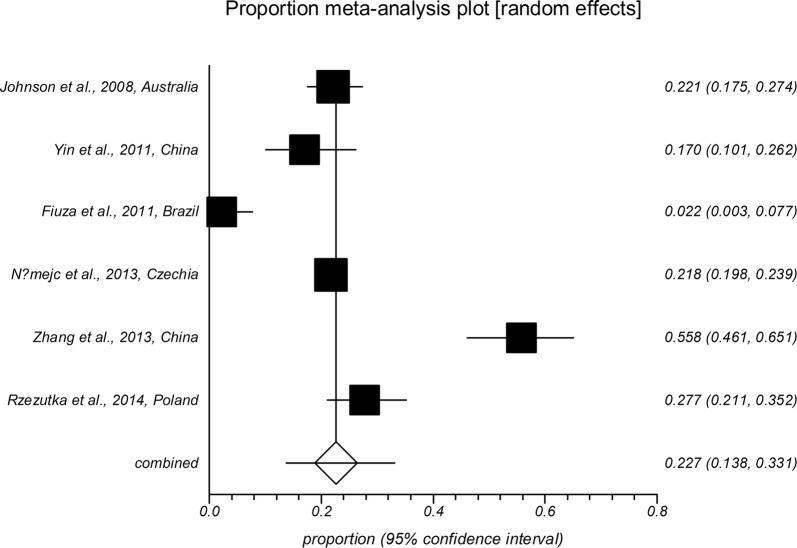

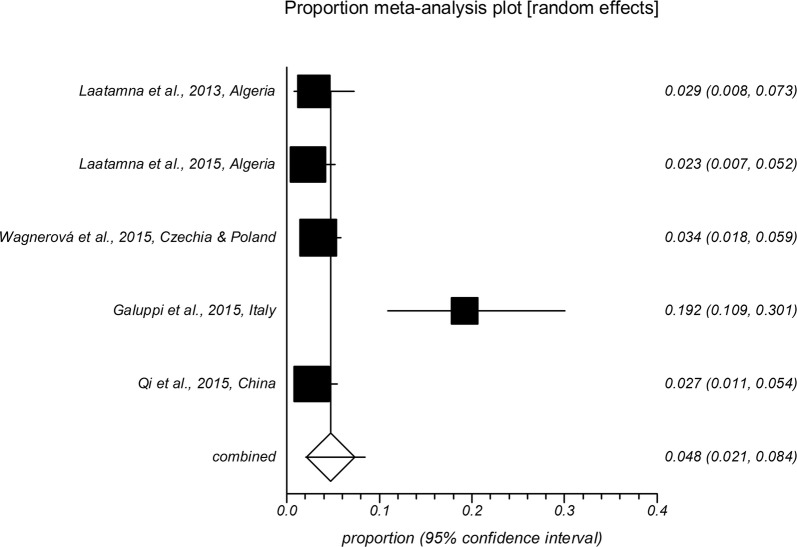

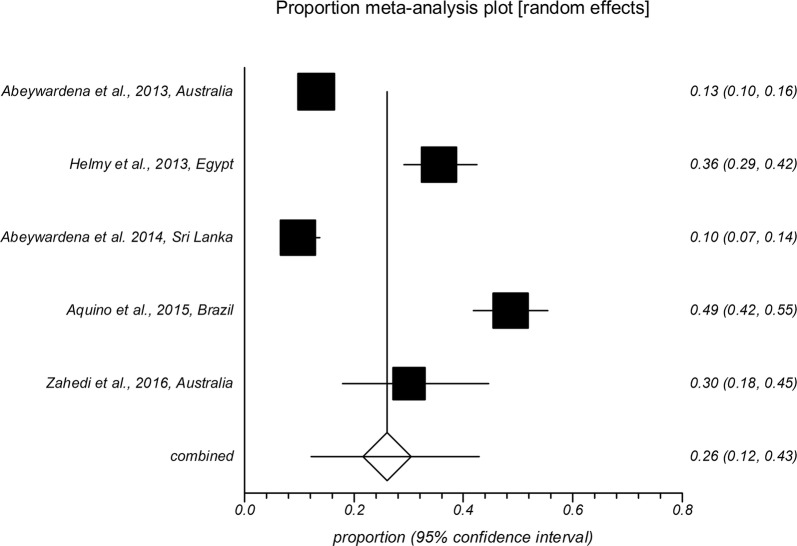

The forest plot diagrams of prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in domestic hoofed animals derived from studies using a PCR method are shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. As forest plots show, there is a considerable variation of study numbers and observed prevalence in a given host species within each defined geographical region, even if only studies based on PCR methodology are included. Considering a wider range of studies, i.e. studies that use either CM or PCR (Table 2), cattle are most commonly infected globally while horses feature the lowest Cryptosporidium prevalence.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. infection in cattle using molecular methods (first author, year and country)

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. infection in goats using molecular methods (first author, year and country)

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. infection in sheep using molecular methods (first author, year and country)

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. infection in pigs using molecular methods (first author, year and country)

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. infection in horses using molecular methods (first author, year and country)

Fig. 7.

Forest plot of prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. infection in buffaloes using molecular methods (first author, year and country)

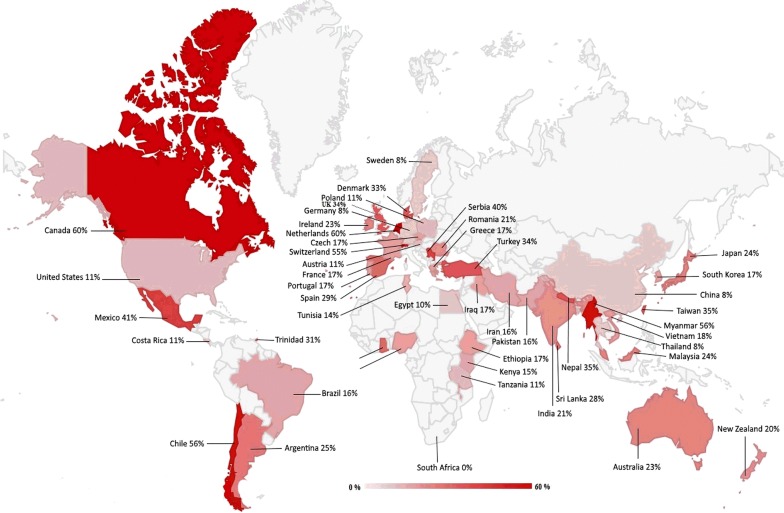

The highest and lowest prevalence rate of Cryptosporidium infection in domestic hoofed animals was observed in America (26%) and Africa (14%) continents, respectively (Table 3, Fig. 8). Among 53 countries with data, Canada (60%) showed the highest infection rate whereas China, Thailand and Germany (8%) had the lowest infection rate (Table 3, Fig. 8).

Table 3.

The prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in terrestrial ungulates (cattle, sheep, goat, pig, horse and buffalo) using conventional microscopic methods. Data are presented separately by continent and country

| Continent | Country | Prevalence, pooled proportion (95% CI) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Africa (43 studies; 17,424 samples) | Egypt | 10 (4.44–19.32) |

| Ethiopia | 17 (7.15–30.13) | |

| Ghana | 29a | |

| Kenya | 15 (10.72–21.30) | |

| Malawi | 18 (10.48–28.78) | |

| Nigeria | 17 (13.07–22.33) | |

| South Africa | 0.5a | |

| Tanzania | 11 (1.59–29.29) | |

| Tunisia | 14 (2.09–44.93) | |

| Total prevalence in Africa: 14 (11.12–18.31) | ||

| America (37 studies; 15,860 samples) | Argentina | 25 (18.83–33.58) |

| Brazil | 16 (5.82–30.23) | |

| Canada | 60 (23.32–91.14) | |

| Chile | 56a | |

| Costa Rica | 11a | |

| Mexico | 41 (31.81–52.23) | |

| Trinidad | 32 (6.47–67.24) | |

| USA | 11 (2.84–24.39) | |

| Total prevalence in America: 26 (18.41–34.67) | ||

| Asia (90 studies; 37,458 samples) | Bangladesh | 9 (2.93–20.36) |

| China | 8 (5.62–12.95) | |

| India | 21 (16.02–28.47) | |

| Iran | 16 (11.96–20.68) | |

| Iraq | 17 (11.36–25.23) | |

| Japan | 24 (0.02–72.52) | |

| Malaysia | 24 (8.43–46.55) | |

| Myanmar | 56a | |

| Nepal | 35 (28.81–43.45) | |

| Pakistan | 16 (9.05–25.96) | |

| South Korea | 17 (11.53–23.57) | |

| Sri Lanka | 28a | |

| Taiwan | 35 (32.44–38.15) | |

| Thailand | 8 (3.08–17.41) | |

| Vietnam | 18a | |

| Total prevalence in Asia: 17 (14.94–20.30) | ||

| Australia (4 studies; 923 samples) | Australia | 23 (0.00–71.85) |

| New Zealand | 20 (15.42–25.92) | |

| Total prevalence in Australia: 21 (7.28–40.02) | ||

| Europe (71 studies, 34,229 samples) | Austria | 11a |

| Czech Republic | 17 (9.87–27.11) | |

| Denmark | 33 (14.90–55.60) | |

| France | 17 (2.56–41.08) | |

| Germany | 8 (3.62–48.31) | |

| Greece | 17 (9.87–27.11) | |

| Ireland | 23 (3.84–52.25) | |

| Netherlands | 60a | |

| Poland | 11 (3.62–21.85) | |

| Portugal | 17a | |

| Romania | 21 (15.02–27.97) | |

| Serbia | 40 (31.95–49.48) | |

| Spain | 29 (19.80–39.75) | |

| Sweden | 8a | |

| Switzerland | 55a | |

| Turkey | 34 (19.82–50.61) | |

| UK | 34 (0.59–85.50) | |

| Total prevalence in Europe: 23 (20.37–27.68) | ||

aOne study was performed in these countries

Fig. 8.

Overall prevalence of Cryptosporidium in different geographical regions in the world. The prevalence in each country was determined from conventional microscopy data in farmed animals (cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses and buffaloes)

The distribution of Cryptosporidium species/genotypes by host and geographical region is summarized in Table 4. Cryptosporidium parvum (monoinfections 4172/10,583; 39.4%) and C. andersoni (monoinfections 1992/10,583; 18.8%) were the most commonly detected Cryptosporidium species (Table 4). A phylogenetic network was constructed based on sequences of Cryptosporidium spp. (Fig. 9) using the Neighbor-Net method. On the basis of this phylogenetic analysis, 10 clades (I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX and X) containing 12 Cryptosporidium spp. were identified (Fig. 9). Interestingly, C. andersoni and C. muris were placed together in Clade I, and C. xiaoi and C. bovis were both placed in Clade III. It further demonstrated a pairwise sister relationship between clades III and IV (clustering C. xiaoi, C. bovis, and C. ryanae), VI and VII (containing C. ubiquitum and C. suis) and VIII and IX (containing C. hominis and C. erinacei), respectively. Interestingly, the result of the phylogenetic analysis indicated that clades II (C. scrofarum), III (C. bovis and C. xiaoi) and IV (C. ryanae) could have originated from a common ancestor. The distribution of Cryptosporidium spp. in a wide range of domestic and wild ungulates is presented in Table 4. The C. parvum is the most common genotype in cattle (54.1%), goats (42.1%) and horses (40.2%), followed by C. ryanae in buffaloes (66.6%), C. suis in pigs (54.1%), and C. xiaoi in sheep (48.9%). In terms of transmission dynamics and clinical importance of zoonotic Cryptosporidium spp., C. hominis, C. parvum, C. andersoni, C. bovis and C. ubiquitum were identified in sheep/goats, cattle/goats/horses/pigs/sheep, cattle/camels/sheep/yaks, buffaloes/cattle/sheep/pigs/red deer and alpacas/buffaloes/cattle/goats/impalas/sheep/red deers, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Worldwide occurrence of Cryptosporidium species or genotypes in selected domestic and wild populations of ungulate species; where applicable, available data are summarized from different sources per country

| Host | Country | No. of isolates | No. of Cryptosporidium species/genotypes | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoinfection (n) | Mixed infection (n) | ||||

| Alpaca | Peru | 3 | C. parvum (2); C. ubiquitum (1) | – | Gómez-Couso et al. [51] |

| Alpaca | UK | 9 | C. parvum (9) | – | Twomey et al. [52]; Wessels et al. [53] |

| Bison | Portugal | 1 | C. tyzzeri (1) | – | Alves et al. [54] |

| Boar | Czech Republic | 32 | C. suis (13); C. scrofarum (7) | C. suis + C. scrofarum (12) | Němejc et al. [55] |

| Buffalo | Egypt | 70 | C. parvum (41); C. ryanae (17); C. bovis (2) | C. parvum + C. ryanae (7); C. parvum + C. bovis (3) | Amer et al. [56]; Helmy et al. [57]; Mahfouz et al. [58]; Ibrahim et al. [59] |

| Buffalo | South Africa | 2 | C. ubiquitum (1); C. bovis (1) | – | Abu Samra et al. [60] |

| Buffalo | Australia | 72 | C. parvum (9); C. ryanae (58); C. scrofarum (1); C. bovis (4) | – | Abeywardena et al. [61]; Zahedi et al. [62] |

| Buffalo | Italy | 6 | C. parvum (6) | – | Caccio et al. [63] |

| Buffalo | Brazil | 63 | C. parvum (1); C. ryanae (60); unknown genotype (2) | – | Aquino et al. [64] |

| Camel | China | 3 | C. andersoni (3) | – | Wang et al. [65]; Liu et al. [66] |

| Cattle | Egypt | 238 | C. parvum (146); C. andersoni (7); C. ryanae (35); C. bovis (15) | C. parvum + C. ryanae (15); C. parvum + C. bovis (10); C. parvum + C. andersoni (3); C. ryanae + C. bovis (7) | Amer et al. [56]; Helmy et al. [57]; Mahfouz et al. [58]; Ibrahim et al. [59] |

| Cattle | Ethiopia | 71 | C. andersoni (54); C. ryanae (3); C. bovis (14) | – | Wegayehu et al. [67] |

| Cattle | Kenya | 27 | C. parvum (17); C. andersoni (3); C. ryanae (6); C. ubiquitum (1) | – | Szonyi et al. [68]; Kangʼethe et al. [69] |

| Cattle | Madagascar | 17 | C. suis (17) | – | Bodager et al. [70] |

| Cattle | Nigeria | 65 | C. andersoni (5); C. ryanae (13); C. bovis (32) | C. ryanae + C. bovis (11); C. bovis + C. andersoni (4) | Ayinmode et al. [71]; Maikai et al. [72] |

| Cattle | South Africa | 6 | C. parvum (1); C. andersoni (2); C. ubiquitum (3) | – | Abu Samra et al. [60]; Abu Samra [73] |

| Cattle | Tunisia | 7 | C. parvum (7) | – | Soltane et al. [74] |

| Cattle | Zambia | 45 | C. parvum (29); C. ubiquitum (1); C. bovis (15) | – | Geurden et al. [75] |

| Cattle | China | 299 | C. parvum (69); C. andersoni (100); C. ryanae (19); C. bovis (89) | C. parvum + C. bovis (6); C. parvum + C. ryanae (4); C. parvum + C. andersoni (3); C. bovis + C. ryanae (9) | Wang et al. [76, 77]; Huang et al. [78] |

| Cattle | India | 21 | C. parvum (6); C. andersoni (3); C. ryanae (3); C. bovis (8); C. occultus (1) | – | Khan et al. [79] |

| Cattle | Iran | 54 | C. parvum (50); C. andersoni (4) | – | Meamar et al. [80]; Fotouhi et al. [81]; Pirestani et al. [82] |

| Cattle | Israel | 61 | C. parvum (61) | Tanriverdi et al. [83] | |

| Cattle | Japan | 33 | C. parvum (32); C. bovis (1) | Karanis et al. [84] | |

| Cattle | Malaysia | 14 | C. parvum (11); C. ryanae (3) | Halim et al. [85] | |

| Cattle | Australia | 439 | C. parvum (297); C. andersoni (20); C. ryanae (30); C. bovis (72); C. hominis (3) | C. parvum + C. bovis (12); C. parvum + C. ryanae (4); C. bovis + C. ryanae (1) | Waldron et al. [86]; Nolan et al. [87]; Ferguson et al. [88]; Ng et al. [89]; McCarthy et al. [90]; O’Brien et al. [91]; Ralston et al. [92] |

| Cattle | New Zealand | 127 | C. parvum (85); C. bovis (42) | – | Learmonth et al. [93]; Grinberg et al. [94]; Al-Mawly et al. [95] |

| Cattle | Belgium | 114 | C. parvum (105); C. suis (1); C. bovis (8) | Geurden et al. [96] | |

| Cattle | Czech Republic | 2019 | C. parvum (699); C. andersoni (1315); C. bovis (5) | – | Kvac et al. [97]; Kvac et al. [98]; Ondrackova et al. [99] |

| Cattle | Denmark | 244 | C. parvum (100); C. andersoni (59); C. ryanae (11); C. bovis (57); C. occultus (3); unknown genotype (4) | C. parvum + C. andersoni (10) | Langkjaer et al. [100]; Enemark et al. [101] |

| Cattle | France | 91 | C. parvum (32); C. ryanae (14); C. ubiquitum (1); C. bovis (11) | C. parvum + C. ryanae (12); C. parvum + C. bovis (11); C. ryanae + C. bovis (8); C. parvum + C. ryanae + C. parvum (2) | Follet et al. [102] |

| Cattle | Hungary | 22 | C. parvum (21); C. ryanae (1) | – | Plutzer et al. [103] |

| Cattle | UK (Northern Ireland) | 224 | C. parvum (213); C. ryanae (3); C. bovis (8) | – | Thompson et al. [104] |

| Cattle | Italy | 101 | C. parvum (101) | – | Duranti et al. [105] |

| Cattle | Poland | 113 | C. parvum (36); C. andersoni (17); C. ryanae (8); C. bovis (52) | – | Rzeżutka & Kaupke [106] |

| Cattle | Portugal | 82 | C. parvum (82) | – | Mendonca et al. [107] |

| Cattle | Romania | 65 | C. parvum (65) | – | Imre et al. [108] |

| Cattle | Scotland | 411 | C. parvum (409); C. hominis (2) | – | Smith et al. [109] |

| Cattle | Serbia | 62 | C. parvum (62) | – | Misic & Abe [110] |

| Cattle | Spain | 267 | C. parvum (255); C. andersoni (1); C. bovis (4); C. felis (4); unknown genotype (3) | – | Mendonca et al. [107]; Quilez et al. [111]; Cardona et al. [112] |

| Cattle | Sweden | 359 | C. parvum (33); C. andersoni (4); C. ryanae (40); C. bovis (262); C. ubiquitum (1) | C. parvum + C. bovis (13); C. parvum + C. ryanae (6) | Silverlas et al. [113]; Silverlas et al. [114]; Silverlas et al. [115]; Bjorkman et al. [116] |

| Cattle | Switzerland | 81 | C. parvum (81) | – | Uhde et al. [117] |

| Cattle | Turkey | 15 | C. parvum (15) | – | Tanriverdi et al. [83] |

| Cattle | UK | 306 | C. parvum (240); C. andersoni (20); C. ryanae (1); C. bovis (31) | C. parvum + C. ryanae + C. bovis (1); C. ryanae + C. bovis (5); C. parvum + C. bovis (1); C. parvum + C. ryanae (1); C. andersoni + C. ryanae (6) | Thompson et al. [104]; Brook et al. [118]; Featherstone et al. [119]; Moriarty et al. [120]; Smith et al. [121] |

| Cattle | Canada | 134 | C. parvum (51); C. andersoni (38); C. ryanae (11); C. bovis (34) | – | Coklin et al. [122]; Coklin et al. [123]; Budu-Amoako et al. [124]; Budu-Amoako et al. [125] |

| Cattle | USA | 698 | C. parvum (240); C. andersoni (203); C. ryanae (83); C. bovis (171); C. suis (1) | Santín et al. [126]; Fayer et al. [127–129]; Szonyi et al. [130] | |

| Cattle | Brazil | 57 | C. parvum (15); C. andersoni (33); C. ryanae (4); C. bovis (5) | Meireles et al. [131]; Sevá et al. [132]; Silva et al. [133] | |

| Giraffe | Czech Republic | 1 | C. muris (1) | – | Kodádková et al. [134] |

| Goat | Tanzania | 5 | C. xiaoi (5) | – | Parsons et al. [135] |

| Goat | Zambia | 1 | C. parvum (1) | – | Goma et al. [136] |

| Goat | China | 44 | C. andersoni (16); C. ubiquitum (24); C. xiaoi (4) | – | Wang et al. [137] |

| Goat | Papua New Guinea | 10 | C. parvum (2); C. hominis (6); C. xiaoi (1); rat genotype II (1) | – | Koinari et al. [138] |

| Goat | Belgium | 11 | C. parvum (11) | Geurden et al. [139] | |

| Goat | France | 31 | C. parvum (1); C. ubiquitum (12); C. xiaoi (18) | – | Rieux et al. [140]; Paraud et al. [141] |

| Goat | Greece | 14 | C. parvum (2); C. ubiquitum (5); C. xiaoi (7) | – | Tzanidakis [142] |

| Goat | Spain | 68 | C. parvum (61); C. xiaoi (7) | – | Díaz et al. [143]; Díaz et al. [144] |

| Goat | UK | 1 | C. hominis (1) | – | Giles et al. [46] |

| Horse | Algeria | 4 | C. erinacei (4) | – | Laatamna et al. [145] |

| Horse | China | 2 | C. andersoni (2) | – | Liu et al. [146] |

| Horse | New Zealand | 9 | C. parvum (9) | – | Grinberg et al. [31] |

| Horse | Czech Republic | 12 | C. parvum (1); C. muris (9); C. ryanae (1); horse genotype (1) | – | Wagnerová et al. [33] |

| Horse | Italy | 35 | C. parvum (5); horse genotype (21) | Horse genotype + C. parvum (9) | Galuppi et al. [147] |

| Horse | UK | 3 | C. parvum (3) | – | Smith et al. [121]; Chalmers et al. [148] |

| Horse | USA | 29 | C. parvum (20); horse genotype (9) | – | Wagnerová et al. [][33]; Burton et al. [149] |

| Impala | South Africa | 2 | C. ubiquitum (2) | – | Abu Samra et al. [60] |

| Mouflon sheep | Czech Republic | 1 | C. muris (1) | – | Kotková et al. [150] |

| Pig | Madagascar | 4 | C. parvum (1); C. suis (3) | – | Bodager et al. [70] |

| Pig | Australia | 87 | C. scrofarum (48); C. suis (35); C, bovis (4) | – | McCarthy et al. [90]; [Morgan et al. [151]; Johnson et al. [152]; Ryan et al. [153] |

| Pig | Czech Republic | 1031 | C. parvum (2); C. muris (5); C. scrofarum (374); C. suis (621) | C. suis + C. scrofarum (29) | Vitovec et al. [154]; Kváč et al. [155, 156]; Němejc et al. [157] |

| Pig | Denmark | 239 | C. scrofarum (171); C. suis (68) | Langkjaer et al. [100]; Petersen et al. [158] | |

| Pig | Ireland | 28 | C. parvum (2); C. muris (1); C. scrofarum (11); C. suis (14) | – | Zintl et al. [32] |

| Pig | UK | 42 | C. parvum (11); C. scrofarum (25); C. suis (6) | – | Smith et al. [121]; Featherstone et al. [159] |

| Pig | Brazil | 2 | C. scrofarum (2) | – | Fiuza et al. [160] |

| Red deer | Czech Republic | 6 | C. muris (1); C. ubiquitum (5) | – | Kotková et al. [150] |

| Roe deer | Spain | 6 | C. ryanae (3); C. bovis (3) | – | García-Presedo et al. [161] |

| Sheep | Egypt | 3 | C. xiaoi (3) | – | Mahfouz et al. [58] |

| Sheep | Tanzania | 2 | C. xiaoi (2) | – | Parsons et al. [135] |

| Sheep | Tunisia | 3 | C. bovis (3) | – | Soltane et al. [74] |

| Sheep | Zambia | 6 | C. parvum (5); C. ubiquitum (1) | – | Goma et al. [136] |

| Sheep | China | 125 | C. andersoni (4); C. ubiquitum (78); C. xiaoi (43) | – | Wang et al. [162]; Li et al. [163] |

| Sheep | Australia | 1005 | C. parvum (78); C. andersoni (6); Sheep genotype I (7); C. scrofarum (8); C. suis (2); C. ubiquitum (148); C. hominis (1); C. xiaoi (641); C. bovis (66); C. macropodum (4); unknown genotype (1) | C. parvum + C. xiaoi (42); C. parvum + C. ubiquitum (1) | Sweeny et al. [43]; Yang et al. [164]; Ryan et al. [165]; Yang et al. [166, 167] |

| Sheep | Papua New Guinea | 6 | C. parvum (4); C. andersoni (1); C. scrofarum (1) | – | Koinari et al. [138] |

| Sheep | Belgium | 9 | C. parvum (9) | Geurden et al. [139] | |

| Sheep | Greece | 10 | C. parvum (7); C. ubiquitum (3) | – | Tzanidakis [142] |

| Sheep | Romania | 24 | C. parvum (20); C. ubiquitum (2); C. xiaoi (2) | – | Imre et al. [168] |

| Sheep | Scotland | 16 | C. parvum (16) | – | Galuppi et al. [147] |

| Sheep | Spain | 57 | C. parvum (46); C. ubiquitum (11) | – | Díaz et al. [144, 169] |

| Sheep | UK | 133 | C. parvum (121); C. hominis (2); C. bovis (10) | – | Mueller-Doblies et al. [28]; Giles et al. [46]; Smith et al. [121]; Pritchard et al. [170] |

| Sheep | Brazil | 42 | C. parvum (3); C. ubiquitum (24); C. xiaoi (15) | – | Fiuza et al. [171]; Paz e Silva et al. [172]; Zucatto et al. [173] |

| White-tailed deer | Czech Republic | 3 | C. muris (1); C. ryanae (2) | Kotková et al. [150] | |

| Yak | China | 158 | C. andersoni (72); C. ryanae (37); C. bovis (47); C. occultus (2) | – | Yang et al. [164] |

Notes: C. suis (previously known as pig genotype I); C. scrofarum (previously known as pig genotype II); C. ryanae (previously deer-like genotype); C. erinacei (previously described as hedgehog genotype); C. bovis (previously bovine genotype B); C. macropodum (previously marsupial genotype II); C. xiaoi (previously bovis-like genotype); C. hominis (synonym: C. parvum genotype 1); C. parvum (synonym: C. parvum genotype 2); C. ubiquitum (previously identified as Cryptosporidium cervine genotype)

Abbreviations: n, numbers in parentheses are number of positive samples genotypes for each species or genotype

Fig. 9.

The phylogeny of Cryptosporidium spp

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we found that 18.9% of the overall populations of the investigated ungulate species were infected with Cryptosporidium spp. Our study showed that although the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection was higher in ungulates of the Cetartiodactyla than in Perissodactyla, the prevalence in the latter was not negligible and needs to be considered in terms of pathogen transmission and cycling. From the data collected and summarized on wild animals (as included in Table 4, and Additional file 2: Table S2), it is obvious that sylvatic cycles play a major role in Cryptosporidium transmission. Wild terrestrial ungulates are likely serving as important reservoir for the parasite, and certainly the infection of livestock and humans may occur by contact to wildlife feces. For meta-analysis, worldwide Cryptosporidium prevalence and species/genotype identity common livestock species have been scrutinized. Overall, Cryptosporidium prevalence in farmed animals is the highest in the Americas and Europe (Table 3) which could be attributed to the intensive farm animal production in these regions. More specifically, considering domestic farm animals, the pooled prevalence of equine Cryptosporidium infection was 4.7%, compared to the pooled prevalence of 29.1%, 26.0%, 24.4%, 22.6% and 8.2% in cattle, buffaloes, sheep, pigs and goats, respectively. Regarding the number of studies published for the different geographical regions, our analysis does not support under investigation of certain regions (e.g. Asia) as cause of a detection bias. This reinforces the suggestion that animal production intensity affects the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. Concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) are most common in cattle and pigs. For example, in the USA, in 2002 more than 71% of all produced beef were derived from operations holding more than 5000 heads of cattle each. It is known that CAFOs pose a major problem due to the high amounts of manure that are released to the environment, facilitating potential pathogen transmission to humans, wildlife and other agricultural operations [39]. Furthermore, pathogen transmission within a CAFO seems much more likely than in more extensive farming systems. Accordingly, a high prevalence of Cryptosporidium was observed in animals from countries with many CAFO operations, especially in studies in Asia and Europe, with both regions harboring the majority of the commercial pig raising industry [40]. High prevalences in pigs in Africa may be attributed to the opposite effect of extensive farming with high exposure to environmental contamination. Other host animals displaying a high prevalence, such as buffaloes and sheep, are also generally kept in larger groups on commercial operations. The comparatively low prevalence rates in equines and goats may potentially result from smaller animal groups and free-range nature of the animal management.

Between wild and domestic animals, it appears that Cryptosporidium prevalence is lower in wild populations than in farmed populations in the same host species. For example, Zahedi et al. [41] reported Cryptosporidium infection rates of 30% in farmed buffalo but 12% in wild buffalo. This suggests that animal density and confinement to the same (contaminated) environment facilitate Cryptosporidium transmission in domestic animals, and there is no clear host species disposition in terms of general susceptibility to infection with the genus Cryptosporidium despite the observed variation in Cryptosporidium infection rates among host species (Table 4).

Cryptosporidiosis in ungulates, especially ruminants, has several economic and health implications. Cryptosporidiosis in neonatal calves can lead to profuse watery diarrhea, loss of appetite, lethargy, dehydration and even death, thus may require costly treatments [42]. Moreover, as shown in sheep and goats, cryptosporidiosis can exhibit long-term effects on the growth of animals [43, 44]. Additionally, infected calves can shed over 1 × 1010 oocysts each day, which can survive in the environments for months. The ingestion of very few oocysts can cause infection in susceptible hosts, including humans [23, 45]. It has been shown that the median infection dose of C. parvum for humans range from below 10 to over 1000 oocysts [22]. Zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. can easily occur seasonally from young animals such as bovine calves to humans, frequently as an occupational hazard [45, 46].

Nearly 40 Cryptosporidium species have been recognized based on molecular, morphological and biological characteristics of the parasites. Previous studies have shown that four major species are responsible for bovine cryptosporidiosis, namely C. parvum, C. andersoni, C. bovis and C. ryanae [1]. We showed that the most prevalent Cryptosporidium species in ungulates are C. parvum and C. andersoni, comprising 39.4% and 18.8% of detected parasites, respectively.

The data also suggest that some Cryptosporidium species are shared among ungulate hosts (Table 4). This indicates the occurrence of some inter-species transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. among ungulate species, making wildlife an important reservoir for infections in domestic animals. Currently, most data on the distribution of Cryptosporidium species and genotypes are available on domestic animal populations. Amazingly, there are clear differences in the distribution of Cryptosporidium species within the same host species among geographical regions. For example, studies from Ethiopia and Nigeria indicate that C. andersoni and C. bovis are the most prevalent species in cattle. In contrast, in countries with concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFO) such as Australia, Iran, Japan and New Zealand, as well as many European and North American countries, C. parvum is prevalent in cattle (Table 4). Similarly, alpacas in their region of origin are mostly infected with C. parvum and C. ubiquitum, while alpacas in the UK only tested positive for C. parvum (Table 4). Calves, lambs and goat kids in areas with more human activities can even have C. hominis infections [19, 41, 47, 48]. Thus, it might be speculated that husbandry systems and contact to other livestock and humans strongly influence the distribution of Cryptosporidium species in an ungulate population.

Our meta-analysis had several limitations. We observed a substantial heterogeneity among the included studies. Heterogeneity in the meta-analyses of prevalence is not uncommon, and the random-effect model implicitly incorporates some of the heterogeneity [49]. Nevertheless, we investigated several factors that can contribute to the observed heterogeneity. The diagnostic method used for the detection of Cryptosporidium infection was one of the main confounding variables. For example, the pooled prevalence of bovine Cryptosporidium infection was estimated 29.1% using PCR compared to 22.5% using conventional microscopy. This seems to indicate that molecular methods such as PCR are highly sensitive and specific for the detection of Cryptosporidium infection, but compared with conventional microscopic methods, they are more expensive and require a higher degree of expertise [50].

There are geographical differences in the estimated pooled prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection. The prevalence was highest in the continent of America, followed by Europe, Australia, Asia and Africa. Canada had the highest prevalence among countries. Study design, time of sampling, age of animals, and conditions of keeping animals are other factors that can contribute to the observed heterogeneity in cryptosporidiosis prevalence, in addition to the nature of animal management.

The outcome of our study is probably affected by the publication bias. Publication bias occurs when the results of studies affect the likelihood of their inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis [49]. Our systematic review was limited to studies published after 1984 in English. Moreover, many studies did not provide enough information to be included in the meta-analysis.

Conclusions

Results of the meta-analysis suggest that Cryptosporidium infection is highly prevalent in ungulates, especially ruminants. Geographical differences in Cryptosporidium prevalence and distribution of Cryptosporidium species are seen for most domestic ungulate hosts. These within-host-species differences could be partially attributed to differences in animal management among geographical regions. The highest prevalence in farmed ungulates occurs in America and Europe where CAFO is widely practiced. The major farm animal hosts of Cryptosporidium spp. appear to be cattle, buffalo, sheep and pigs. These farm animals are potent reservoirs for a variety of Cryptosporidium species. Cryptosporidium prevalence is also clearly higher in farmed animals than in wild ungulate populations. Inter-species transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. appears to be affected by contact with other host species (humans or other animals) and infection pressure (intensive farming), rendering the investigated ungulate hosts capable of propagating both zoonotic and non-zoonotic Cryptosporidium species.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. PRISMA checklist.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Worldwide prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. in herbivorous animals.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. F. Shahrivar and Dr. A.S. Pagheh for their assistance and kind help.

Abbreviations

- CM

conventional microscopy

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ICT

immunochromatographic test

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- QLAT

quantitative latex agglutination test

Authors’ contributions

KHN, EH, DC and LX contributed to the design of the study. KHN, EA and AS conducted the systematic review of the literature and extracted data. EA, AS, DC and LX analyzed data and drafted the first version of the manuscript. EA, DC, BB and LX contributed to the interpretation of data and writing of the first draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kareem Hatam-Nahavandi, Email: karim.hatam@gmail.com.

Ehsan Ahmadpour, Email: ehsanahmadpour@gmail.com.

David Carmena, Email: d.carmena71@gmail.com.

Adel Spotin, Email: adelespotin@gmail.com.

Berit Bangoura, Email: bbangour@uwyo.edu.

Lihua Xiao, Email: lxiao1961@gmail.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13071-019-3704-4.

References

- 1.Feng Y, Ryan UM, Xiao L. Genetic diversity and population structure of Cryptosporidium. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:997–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalil IA, Troeger C, Rao PC, Blacker BF, Brown A, Brewer TG, et al. Morbidity, mortality, and long-term consequences associated with diarrhoea from Cryptosporidium infection in children younger than 5 years: a meta-analysis study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e758–e768. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson M-A, Roy SL, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:7–15. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.P11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DuPont HL. Persistent diarrhea: a clinical review. JAMA. 2016;315:2712–2723. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatam-Nahavandi K, Mohebali M, Mahvi AH, Keshavarz H, Khanaliha K, Tarighi F, et al. Evaluation of Cryptosporidium oocyst and Giardia cyst removal efficiency from urban and slaughterhouse wastewater treatment plants and assessment of cyst viability in wastewater effluent samples from Tehran, Iran. J Water Reuse Desal. 2015;5:372–390. doi: 10.2166/wrd.2015.108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcos LA, Gotuzzo E. Intestinal protozoan infections in the immunocompromised host. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:295–301. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283630e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho YI, Han JI, Wang C, Cooper V, Schwartz K, Engelken T, et al. Case–control study of microbiological etiology associated with calf diarrhea. Vet Microbiol. 2013;166:375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meganck V, Hoflack G, Opsomer G. Advances in prevention and therapy of neonatal dairy calf diarrhoea: a systematical review with emphasis on colostrum management and fluid therapy. Acta Vet Scand. 2014;56:75. doi: 10.1186/s13028-014-0075-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson RA, Palmer CS, O’Handley R. The public health and clinical significance of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in domestic animals. Vet J. 2008;177:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santin M. Clinical and subclinical infections with Cryptosporidium in animals. N Z Vet J. 2013;61:1–10. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2012.731681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oates SC, Miller MA, Hardin D, Conrad PA, Melli A, Jessup DA, et al. Prevalence, environmental loading, and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia isolates from domestic and wild animals along the Central California Coast. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:8762–8772. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02422-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverlås C, Bosaeus-Reineck H, Näslund K, Björkman C. Is there a need for improved Cryptosporidium diagnostics in Swedish calves? Int J Parasitol. 2013;43:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karanis P, Plutzer J, Halim NA, Igori K, Nagasawa H, Ongerth J, et al. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium from animal sources in Qinghai province of China. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:1575–1580. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0681-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Efstratiou A, Ongerth JE, Karanis P. Waterborne transmission of protozoan parasites: review of worldwide outbreaks—an update 2011–2016. Water Res. 2017;114:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatam-Nahavandi K, Mohebali M, Mahvi AH, Keshavarz H, Najafian HR, Mirjalali H, et al. Microscopic and molecular detection of Cryptosporidium andersoni and Cryptosporidium xiaoi in wastewater samples of Tehran Province, Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2016;11:499–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budu-Amoako E, Greenwood SJ, Dixon BR, Barkema HW, McClure J. Foodborne illness associated with Cryptosporidium and Giardia from livestock. J Food Prot. 2011;74:1944–1955. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan U, Hijjawi N, Xiao L. Foodborne cryptosporidiosis. Int J Parasitol. 2018;48:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vermeulen LC, Benders J, Medema G, Hofstra N. Global Cryptosporidium loads from livestock manure. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51:8663–8671. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b00452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Razakandrainibe R, Costa D, Le Goff L, Lemeteil D, Ballet JJ, Gargala G, et al. Common occurrence of Cryptosporidium hominis in asymptomatic and symptomatic calves in France. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts CL, Morin C, Addiss DG, Wahlquist SP, Mshar PA, Hadler JL. Factors influencing Cryptosporidium testing in Connecticut. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2292–2293. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2292-2293.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chappell CL, Okhuysen PC, Sterling CR, DuPont HL. Cryptosporidium parvum: intensity of infection and oocyst excretion patterns in healthy volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:232–236. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan U, Fayer R, Xiao L. Cryptosporidium species in humans and animals: current understanding and research needs. Parasitoloy. 2014;141:1667–1685. doi: 10.1017/S0031182014001085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson R, Ash A. Molecular epidemiology of Giardia and Cryptosporidium infections. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;40:315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nichols GL, Chalmers RM, Hadfield SJ. Cryptosporidium: parasite and disease. Vienna: Springer; 2014. Molecular epidemiology of human cryptosporidiosis; pp. 81–147. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong C, Cao XF, Deng L, Li W, Huang XM, Lan JC, et al. Epidemiology of Cryptosporidium infection in cattle in China: a review. Parasite. 2017;24:1. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2017001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao L, Feng Y. Zoonotic cryptosporidiosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;52:309–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller-Doblies D, Giles M, Elwin K, Smith RP, Clifton-Hadley FA, Chalmers RM. Distribution of Cryptosporidium species in sheep in the UK. Vet Parasitol. 2008;154:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quílez J, Torres E, Chalmers RM, Hadfield SJ, del Cacho E, Sánchez-Acedo C. Cryptosporidium genotypes and subtypes in lambs and goat kids in Spain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6026–6031. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00606-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertson LJ. Giardia and Cryptosporidium infections in sheep and goats: a review of the potential for transmission to humans via environmental contamination. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:913–921. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809002295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grinberg A, Learmonth J, Kwan E, Pomroy W, Lopez Villalobos N, Gibson I, Widmer G. Genetic diversity and zoonotic potential of Cryptosporidium parvum causing foal diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2396–2398. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00936-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zintl A, Neville D, Maguire D, Fanning S, Mulcahy G, Smith H, et al. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium species in intensively farmed pigs in Ireland. Parasitology. 2007;134:1575–1582. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007002983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagnerová P, Sak B, McEvoy J, Rost M, Sherwood D, Holcomb K, et al. Cryptosporidium parvum and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in American mustangs and Chincoteague ponies. Exp Parasitol. 2016;162:24–27. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wells B, Shaw H, Hotchkiss E, Gilray J, Ayton R, Green J, et al. Prevalence, species identification and genotyping Cryptosporidium from livestock and deer in a catchment in the Cairngorms with a history of a contaminated public water supply. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:66. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0684-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.García-Presedo I, Pedraza-Díaz S, González-Warleta M, Mezo M, Gómez-Bautista M, Ortega-Mora LM, et al. Presence of Cryptosporidium scrofarum, C. suis and C. parvum subtypes IIaA16G2R1 and IIaA13G1R1 in Eurasian wild boars (Sus scrofa) Vet Parasitol. 2013;196:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hribar A. Understanding concentrated animal feeding operations and their impact on communities. 2010. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/docs/understanding_cafos_nalboh.pdf.

- 40.Statista. Number of pigs worldwide in 2018, by leading country (in million head). 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/263964/number-of-pigs-in-selected-countries/.

- 41.Zahedi A, Monis P, Aucote S, King B, Paparini A, Jian F, et al. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium species in animals inhabiting Sydney water catchments. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0168169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobson C, Al-Habsi K, Ryan U, Williams A, Anderson F, Yang R, et al. Cryptosporidium infection is associated with reduced growth and diarrhoea in goats beyond weaning. Vet Parasitol. 2018;260:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sweeny JP, Ryan U, Robertson I, Jacobson C. Cryptosporidium and Giardia associated with reduced lamb carcase productivity. Vet Parasitol. 2011;182:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomson S, Hamilton CA, Hope JC, Katzer F, Mabbott NA, Morrison LJ, et al. Bovine cryptosporidiosis: impact, host-parasite interaction and control strategies. Vet Res. 2017;48:42. doi: 10.1186/s13567-017-0447-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benschop J, Booker C, Shadbolt T, Weston J. A Retrospective cohort study of an outbreak of cryptosporidiosis among veterinary students. Vet Sci. 2017;4:E29. doi: 10.3390/vetsci4020029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giles M, Chalmers R, Pritchard G, Elwin K, Mueller-Doblies D, Clifton-Hadley F. Cryptosporidium hominis in a goat and a sheep in the UK. Vet Rec. 2009;164:24–25. doi: 10.1136/vr.164.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chalmers RM, Giles M. Zoonotic cryptosporidiosis in the UK–challenges for control. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;109:1487–1497. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Connelly L, Craig B, Jones B, Alexander C. Genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. within a remote population of Soay Sheep on St. Kilda Islands, Scotland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:2240–2246. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02823-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Green S, Higgins J. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2006. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- 50.Chalmers RM, Katzer F. Looking for Cryptosporidium: the application of advances in detection and diagnosis. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:237–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gomez-Couso H, Ortega-Mora LM, Aguado-Martinez A, Rosadio-Alcantara R, Maturrano-Hernandez L, Luna-Espinoza L, et al. Presence and molecular characterisation of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in alpacas (Vicugna pacos) from Peru. Vet Parasitol. 2012;187:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Twomey DF, Barlow AM, Bell S, Chalmers RM, Elwin K, Giles M, et al. Cryptosporidiosis in two alpaca (Lama pacos) holdings in the South-West of England. Vet J. 2008;175:419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wessels J, Wessels M, Featherstone C, Pike R. Cryptosporidiosis in eight-month-old weaned alpacas. Vet Rec. 2013;173:426–427. doi: 10.1136/vr.f6395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alves M, Xiao L, Lemos V, Zhou L, Cama V, da Cunha MB, et al. Occurrence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in mammals and reptiles at the Lisbon Zoo. Parasitol Res. 2005;97:108–112. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1384-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Němejc K, Sak B, Květoňová D, Hanzel V, Jenikova M. The first report on Cryptosporidium suis and Cryptosporidium pig genotype II in Eurasian wild boars (Sus scrofa) (Czech Republic) Vet Parasitol. 2012;184:122–125. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amer S, Zidan S, Feng Y, Adamu H, Li N, Xiao L. Identity and public health potential of Cryptosporidium spp. in water buffalo calves in Egypt. Vet Parasitol. 2013;191:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Helmy AY, Krücken J, Nöckler K, Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Zessin KH. Molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium in livestock animals and humans in the Ismailia province of Egypt. Vet Parasitol. 2013;193:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mahfouz ME, Mira NN, Amer S. Prevalence and genotyping of Cryptosporidium spp. in farm animals in Egypt. J Vet Med Sci. 2014;76:1569–1575. doi: 10.1292/jvms.14-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ibrahim MA, Abdel-Ghany AE, Abdel-Latef GK, Abdel-Aziz SA, Aboelhadid SM. Epidemiology and public health significance of Cryptosporidium isolated from cattle, buffaloes, and humans in Egypt. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:2439–2448. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-4996-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abu Samra N, Jori F, Xiao L, Rikhotso O, Thompson PN. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium species at the wildlife/livestock interface of the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;36:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abeywardena H, Jex AR, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Haydon SR, Stevens MA, Gasser RB. First molecular characterisation of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from Bubalus bubalis (water buffalo) in Victoria, Australia. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;20:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zahedi A, Phasey J, Boland T, Ryan U. First report of Cryptosporidium species in farmed and wild buffalo from the Northern Territory, Australia. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:1349–1353. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-4901-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caccio SM, Rinaldi L, Cringoli G, Condoleo R, Pozio E. Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia duodenalis in the Italian water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) Vet Parasitol. 2007;150:146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aquino MCC, Widemer G, Zucatto AS, Viol MA, Inacio SV, Nakamura AA, et al. First molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. infecting buffalo calves in Brazil. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2015;62:657–661. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang R, Zhang L, Ning C, Feng Y, Jian F, Xiao L, Lu B, Ai W, Dong H. Multilocus phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium andersoni (Apicomplexa) isolated from a Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) in China. Parasitol Res. 2008;102:915–920. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0851-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu X, Zhou X, Zhong Zh, Deng J, Chen W, Cao S, et al. Multilocus genotype and subtype analysis of Cryptosporidium andersoni derived from a Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) in China. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:2129–2136. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wegayehu T, Karim R, Anberber M, Adamu H, Erko B, Zhang L, Tilahun G. Prevalence and genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium species in dairy calves in Central Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0154647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Szonyi B, Kangethe EK, Mbae CK, Kakundi EM, Kamwati SK, Mohammed HO. First report of Cryptosporidium deer-like genotype in Kenyan cattle. Vet Parasitol. 2008;153:172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kangʼethe EK, Mulinge EK, Skilton RA, Njahira M, Monda JG, Nyongesa C, et al. Cryptosporidium species detected in calves and cattle in Dagoretti, Nairobi, Kenya. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44(Suppl. 1):S25–S31. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bodager JR, Parsons MB, Wright PC, Rasambainarivo F, Roellig D, Xiao L, et al. Complex epidemiology and zoonotic potential for Cryptosporidium suis in rural Madagascar. Vet Parasitol. 2015;207:140e143. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ayinmode AB, Fagbemi BO, Xiao L. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in native calves in Nigeria. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:1019–1021. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1972-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maikai BV, Umoh JU, Kwaga JKB, Lawal I, Maikai VA, Camae V, Xiao L. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in native breeds of cattle in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Vet Parasitol. 2011;178:241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abu Samra N, Jori F, Cacciò SM, Frean J, Poonsamy B, Thompson PN. Cryptosporidium genotypes in children and calves living at the wildlife or livestock interface of the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2015;83:a1024. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v83i1.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Soltane R, Guyot K, Dei-Cas E, Ayadi A. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. (Eucoccidiorida: Cryptosporiidae) in seven species of farm animals in Tunisia. Parasite. 2007;14:335–338. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2007144335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Geurden T, Goma FY, Siwila J, Phiri IGK, Mwanza AM, Gabriel S, et al. Prevalence and genotyping of Cryptosporidium in three cattle husbandry systems in Zambia. Vet Parasitol. 2006;138:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang R, Wang H, Sun Y, Zhang L, Jian F, Qi M, Ning C, Xiao L. Characteristics of Cryptosporidium transmission in preweaned dairy cattle in Henan, China. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1077–1082. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02194-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang R, Ma G, Zhao J, Lu Q, Wang H, Zhang L, Jian F, Ning C, Xiao L. Cryptosporidium andersoni is the predominant species in post-weaned and adult dairy cattle in China. Parasitol Int. 2011;60:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huang J, Yue D, Meng Q, Wang R, Zhao J, Li J, et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis in dairy cattle in Ningxia, northwestern China. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:292. doi: 10.1186/s12917-014-0292-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Khan SM, Debnath C, Pramanik AK, Xiao L, Nozaki T, Ganguly S. Molecular characterization and assessment of zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium from dairy cattle in West Bengal, India. Vet Parasitol. 2010;171:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Meamar AR, Guyot K, Certad G, Dei-Cas E, Mohraz M, Mohebali M, et al. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans and animals in Iran. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1033–1035. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00964-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fotouhi Ardakani R, Fasihi Harandi M, Soleiman Banaei S, Kamyabi H, Atapour M, Sharifi I. Epidemiology of Cryptosporidium infection of cattle in Kerman/Iran and molecular genotyping of some isolates. J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2008;15:313–320. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pirestani M, Sadraei J, Dalimi A, Zawar M, Vaeznia H. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium isolates from human and bovine using 18S rRNA gene in Shahriar county of Tehran, Iran. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:447–467. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tanriverdi S, Markovics A, Arslan MO, Itik A, Shkap V, Widmer G. Emergence of distinct genotypes of Cryptosporidium parvum in structured host populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2507–2513. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2507-2513.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Karanis P, Eiji T, Palomino L, Boonrod K, Plutzer J, Ongerth J, Igarashi I. First description of Cryptosporidium bovis in Japan and diagnosis and genotyping of Cryptosporidium spp. in diarrheic pre-weaned calves in Hokkaido. Vet Parasitol. 2010;169:387–390. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Halim NA, Plutzer J, Bakheit MA, Karanis P. First report of Cryptosporidium deer-like genotype in Malaysian cattle. Vet Parasitol. 2008;152:325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Waldron LS, Dimeski B, Beggs PJ, Ferrari BC, Power ML. Molecular epidemiology, spatiotemporal analysis, and ecology of sporadic human cryptosporidiosis in Australia. App Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:7757–7765. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00615-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nolan MJ, Jex AR, Mansell PD, Browning GF, Gasser RB. Genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium parvum from calves by mutation scanning and targeted sequencing-zoonotic implications. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:2640–2647. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ferguson C. Quantifying Infectious Pathogen Sources in WA Drinking Water Catchments. Report by ASL Water services group. 2010.

- 89.Ng J, Yang R, McCarthy S, Gordon C, Hijjawi N, Ryan U. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in pre-weaned calves in Western Australia and New South Wales. Vet Parasitol. 2011;176:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McCarthy S, Ng J, Gordon C, Miller R, Wyber A, Ryan UM. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia species in animals in irrigation catchments in the southwest of Australia. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118:596–599. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.OʼBrien E, McInnes L, Ryan U. Cryptosporidium GP60 genotypes from humans and domesticated animals in Australia, North America and Europe. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118:118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ralston B, Thompson RC, Pethick D, McAllister TA, Olson ME. Cryptosporidium andersoni in Western Australian feedlot cattle. Aust Vet J. 2010;88:458–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2010.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Learmonth JJ, Ionas G, Pita AB, Cowie RS. Identification and genetic characterisation of Giardia and Cryptosporidium strains in humans and dairy cattle in the Waikato Region of New Zealand. Water Sci Technol. 2003;47:21–26. doi: 10.2166/wst.2003.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grinberg A, Lopez-Villalobos N, Pomroy W, Widmer G, Smith H, Tait A. Host-shaped segregation of the Cryptosporidium parvum multilocus genotype repertoire. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136:273–278. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807008345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Al-Mawly JA, Grinberg A, Velathanthiri N, French N. Cross-sectional study of prevalence, genetic diversity and zoonotic potential of Cryptosporidium parvum cycling in New Zealand dairy farms. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:240. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0855-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Geurden T, Berkvens D, Martens C, Casaert S, Vercruysse J, Claerebout E. Molecular epidemiology with subtype analysis of Cryptosporidium in calves in Belgium. Parasitology. 2007;134:1981–1987. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007003460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kvac M, Kouba M, Vitovec J. Age-related and housing-dependence of Cryptosporidium infection of calves from dairy and beef herds in South Bohemia. Czech Republic. Vet Parasitol. 2006;137:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kvac M, Hromadova N, Kvetooova D, Rost M, Sak B. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in pre-weaned dairy calves in the Czech Republic: absence of C. ryanae and management-associated distribution of C. andersoni, C. bovis and C. parvum subtypes. Vet Parasitol. 2011;177:378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ondrackova Z, Kvac M, Sak B, Kvetonova D, Rost M. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in dairy cattle in South Bohemia, the Czech Republic. Vet Parasitol. 2009;165:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Langkjaer RB, Vigre H, Enemark HL, Maddox-Hyttel C. Molecular and phylogenetic characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from pigs and cattle in Denmark. Parasitology. 2007;134:339–350. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Enemark HL, Ahrens P, Lowery C, Thamsborg SM, Enemark JMD, Bille-Hansen V, Lind P. Cryptosporidium andersoni from a Danish cattle herd: identification and preliminary characterization. Vet Parasitol. 2002;107:37–49. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Follet J, Guyot K, Leruste H, Follet-Dumoulin A, Hammouma-Ghelboun O, Certad G, Dei-Cas E, Halama P. Cryptosporidium infection in a veal calf cohort in France: molecular characterization of species in a longitudinal study. Vet Res. 2011;42:116. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Plutzer J, Karanis P. Genotype and subtype analyses of Cryptosporidium isolates from cattle in Hungary. Vet Parasitol. 2007;146:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Thompson HP, Dooley JS, Kenny J, McCoy M, Lowery CJ, Moore JE. Genotypes and subtypes of Cryptosporidium spp. in neonatal calves in Northern Ireland. Parasitol Res. 2007;100:619–624. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0305-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Duranti A, Caccio SM, Pozio E, Di Egidio A, De Curtis M, Battisti A, Scaramozzino P. Risk factors associated with Cryptosporidium parvum infection in cattle. Zoonoses Public Health. 2009;56:176–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2008.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rzeżutka A, Kaupke A. Occurrence and molecular identification of Cryptosporidium species isolated from cattle in Poland. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mendonca C, Almeida A, Castro A, Delgado ML, Soares S, Correia da Costa JM, Canada N. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia isolates from cattle from Portugal. Vet Parasitol. 2007;147:47–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Imre K, Lobo ML, Matos O, Popescu C, Genchi C, Dărăbus G. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium isolates from pre-weaned calves in Romania: is there an actual risk of zoonotic infections? Vet Parasitol. 2011;181:321–324. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Smith HV, Nichols RA, Mallon M, Macleod A, Tait A, Reilly WJ, et al. Natural Cryptosporidium hominis infections in Scottish cattle. Vet Rec. 2005;156:710–711. doi: 10.1136/vr.156.22.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Misic Z, Abe N. Subtype analysis of Cryptosporidium parvum isolates from calves on farms around Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro, using the 60 kDa glycoprotein gene sequences. Parasitology. 2007;134:351–358. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Quilez J, Torres E, Chalmers RM, Robinson G, Del Cacho E, Sanchez-Acedo C. Cryptosporidium species and subtype analysis from dairy calves in Spain. Parasitology. 2008;135:1613–1620. doi: 10.1017/S0031182008005088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cardona GA, de Lucio A, Bailo B, Cano L, de Fuentes I, Carmena D. Unexpected finding of feline-specific Giardia duodenalis assemblage F and Cryptosporidium felis in asymptomatic adult cattle in Northern Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2015;30:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Silverlas C, Blanco-Penedo I. Cryptosporidium spp. in calves and cows from organic and conventional dairy herds. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:529–539. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812000830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]