Abstract

Background:

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a rare and aggressive malignant neoplasm typically located in the abdomen or pelvis. Other possible locations are the chest, pleura, scrotum, and central nervous system. DSRCT originally arising from the brachial plexus (BP) is extremely rare, to the best of our knowledge, only two cases have been previously described in the English scientific literature.

Case Description:

The authors present one new case of DSRCT arising from the left BP, the first in this location with rapid progression and in a female patient. We also highlight the importance of multimodal therapy, which included resection and both adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy. Macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of the lesion are detailed, as well as the patient’s status at 56-month follow-up.

Conclusion:

For primary BP DSRCT, aggressive subtotal resection followed by radiation and chemotherapy can be satisfactory for disease control and for maintaining or improving the neurological status.

Keywords: Brachial plexus, Desmoplastic small round cell tumor, EWS1-WT1 fusion protein, Medical oncology, Surgical oncology

BACKGROUND

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCTs) is rare and aggressive malignant neoplasms, characterized by proliferation of small round tumor cells and abundant desmoplastic stroma. Multiphenotypic differentiation is observed by immunohistochemistry.[4,7] The diagnosis is usually made in the disease’s final stages when multiple metastases impose. The most typical presentation is as a large mass in the abdomen or pelvis, commonly accompanied by peritoneal metastases.[3,6] Numerous other locations have been reported, including the ethmoid sinus, parotid gland, soft tissue, scrotum, and various visceral organs such as the liver, pancreas, and the central nervous system among others.[1,8,9,14,15]

The immunohistochemical profile of DSRCT is specific and shows expression of proteins associated with epithelial, muscular, and neural differentiation. On the other hand, employing immunohistochemistry for the diagnosis of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) remains very limited. It must be noted that DSRCT has a specific profile, quite different from MPNST.[4,7]

To date, only two cases of DSRCT arising from the brachial plexus (BP) have been described, one each by Mathys et al.[10] and Miwa et al.[13] In this paper, we add a third case. However, we consider this case of a female patient unique, as the neoplasm displayed aggressive progression. The patient was successfully treated with multimodal treatment (MMT) and she is still alive and doing well almost 5 years postdiagnosis.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 42-year-old woman was referred to our service with an intensely painful, progressively growing mass in her left armpit. This lesion had been noted for about 5 months, compromising her routine activities and sleeping. Worsening muscular weakness was also observed. An open biopsy of the mass had been undertaken elsewhere 3 months earlier, yielding inconclusive results. After that procedure, the patient’s pain intensified dramatically, followed by deterioration in motor strength over the next 3 months. She rated her pain as 9 on a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS).[11] There was no relief with analgesics.

General clinical examination was normal, including breast examination. On palpation, the mass in the medial region of the upper arm and axilla was extremely tender and firmly fixed to surrounding tissue. Marked lymphedema of the whole limb was observed.

On neurological examination, a positive Tinel’s sign was present, radiating toward the left hand. Profound BP palsy was observed, involving multiple nerves and including weakness in key muscle groups. This was graded as M0 arm abduction, M1 elbow flexion, M2 wrist extension, M2 finger extension, and M0 intrinsic musculature strength, as per the British Medical Research Council muscle strength rating scale.[12] Sensory examination was characterized by almost complete hand anesthesia of the median nerve’s corresponding area.

Imaging study

Computerized tomography (CT) of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, yielding no evidence of tumor. This raised suspicion that the tumor primarily arose within or from the BP or adjacent tissues. Thus, we considered the differential diagnosis of a neurogenic tumor or a sarcoma of the plexus region. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a solid, irregular mass with a heterogeneous hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images, measuring approximately 5.3 × 3.8 × 6.2 cm in the left BP region, with clear involvement of both vascular and neural structures. Contrast enhancement revealed uptake in several lymph nodes, presumed secondary to metastatic spread [Figure 1].

Figure 1:

Coronal T1-weighted (a) and T2-weighted contrast- enhanced (b) magnetic resonance imaging of the left arm and axillary region, showing a heterogeneous mass involving part of the left infraclavicular plexus and left brachial plexus.

Surgery

A classic infraclavicular BP approach was employed, extending to the axilla and proximal arm along to the bicipital sulcus. The pectoralis major muscle was retracted medially, and the deltoid muscle retracted laterally as to expose the clavico-deltopectoral triangle, by which, through sectioning of the pectoralis minor muscle underneath, we could progressively expose the mass. We observed that it originated from the lateral division of the upper trunk of the left BP, invading surrounding structures and adhering to other BP elements, including the axillary/brachial artery and veins [Figure 2]. Despite the tumor’s extent and hard consistency, a cleavage plane was identified beneath the muscular structures around the lesion. During surgery, intraoperative neuromonitoring was conducted, allowing us to progressively resect the tumor in a piecemeal fashion while preserving nervous structures such as the muscular cutaneous nerve, a long segment of the medium nerve, the antebrachial medial cutaneous nerve, and part of the axillary/brachial artery. No adherence to the chest wall was observed. Involved lymph nodes were also resected. Complete resection of the tumor was deemed impossible since important vascular structures, such as the axillary artery, were completely engulfed by the mass. However, due to the absence of any vascular deficit, no specific treatment of the vasculature was adopted.

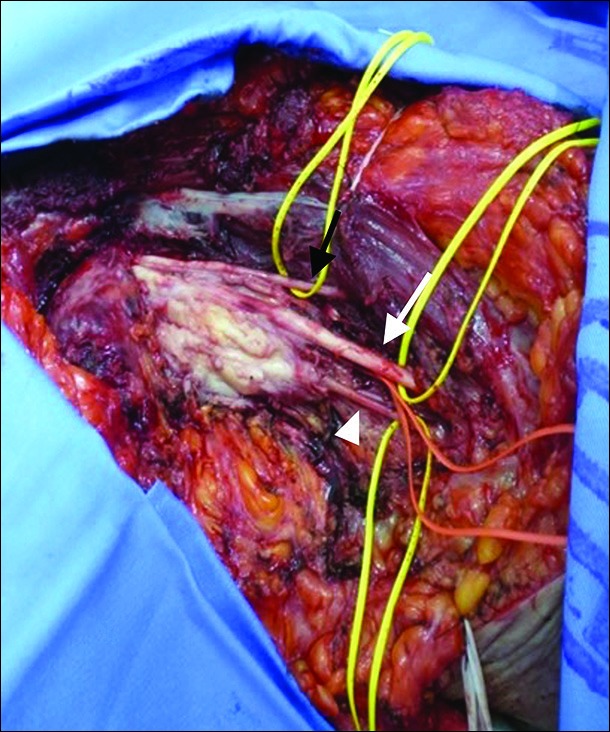

Figure 2:

Photograph taken during subtotal surgical resection of the lesion, showing the musculocutaneous nerve (black arrow), median nerve (white arrow), and antebrachial medial cutaneous nerve (white arrowhead), all liberated from the tumor, while the brachial artery (under the median nerve, circled by the red loop) still enveloped by tumor.

Pathology

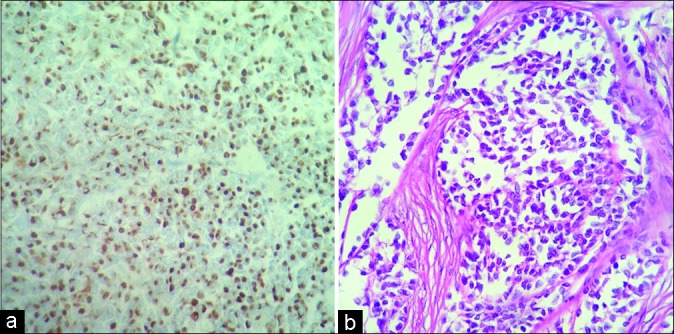

At a macroscopic level, the resected tumor fragments together weighted 300 g and all had a firm consistency [Figure 3]. Microscopically, the tumor consisted of sheets and nests of medium-sized cells, with round, hyperchromatic nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli, as well as desmoplastic stroma and many vessels. Numerous mitoses were observed (7/10 high- power fields, ×400). The tumor infiltrated peripheral nerves. Immunohistochemistry profile showed positive staining for desmin (dot-like pattern), AE1/3, WT1 (nuclear pattern), as well as CD56 and CD99 [Figure 4]. Negative stains were noted for CD34, S-100 protein, chromogranin, synaptophysin, and myogenin. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) revealed rearrangement of the EWS gene, which provided evidence of a 22q12 locus. These features are consistent with the diagnosis of DSRCT.

Figure 3:

Fragments of the tumor after resection, all of very firm consistency that collectively weighed roughly 250 g.

Figure 4:

Microscopic view of the tumor. (a) Intense and diffuse cytoplasmic dot-like desmin stain of tumor cells. Desmin, original ×200. (b) Nests of round and rhabdoid tumor cells. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original ×400.

Follow-up

The patient experienced an almost immediate reduction in her pain from 9/10 preoperatively to 3/10 postoperatively using the VAS pain rating scale.[11] She was discharged home 10 days after surgery requiring no opioid analgesia and she was referred to the Medical Oncology Clinic for adjuvant therapy.

Chemotherapy was pursued with a protocol as follows: four courses, with 3-week intervals between each, of cisplatin (120 mg/m2 for 2 days) and doxorubicin (30 mg/m2/day for 2 days). Adjuvant local radiotherapy (RT) was administered to a cumulative dose of 65 Gy, fractionated in 16 sessions over 3 weeks. Further, reduction in pain was observed.

The patient was monitored through regular consultations, initially monthly during the chemotherapy and RT, then every 3 months, and lately every 4 months in our outpatient facility. Initially, the surveillance schedule for the patient was a CT of thorax and abdomen every 3 months, then every 6 months, and now annually. During follow-up, 2 months after surgery, two new lung lesions, not observed at the presurgical staging, were detected by CT, one in each pulmonary apex, both considered metastatic. Due to the fact that their discovery was made during the chemotherapy course, the responsible oncologist decided to keep to the chemotherapy and RT schemes previously outlined, and, if needed, will consider further chemotherapy doses. However, both lesions disappeared after radiation and chemotherapy.

Fifty-six months after treatment, she continues to report sporadic neuropathic pain in her hand (VAS = 2)[11] controlled with gabapentin and amitriptyline. There is recovery in her motor function to a level of M3 in arm abduction to 30°, elbow flexion to M4 and wrist extension, fingers extension, and intrinsic to M3.[12] Her hand remains numb.

Last MRI, 4 months ago, depicted a residual mass in the axilla. Lymph node involvement and lymphedema had diminished, and both lesions previously detected in her lungs remained absent.

DISCUSSION

Since DSRCTs were first described in 1989 by Gerald and Rosai,[6] the tumors have been documented to arise in a multitude of tissues. However, to the best of our knowledge, only two previously published cases of primary DSRCT have been reported arising directly from the BP.[10,13] Our patient, a 42-year-old female with rapidly worsening pain, weakness, and numbness in her right arm over 5 months, had an initial open yet inconclusive biopsy. After biopsy, her pain becomes intolerable and she lost considerable motor and sensory function.

In both cases of BP-DSRCT described previously, the patients were male and the time from initial symptoms to diagnosis was prolonged over several years, due both to a slowly growing mass and initially negative or equivocal investigations.[10,13] Given the rarity of DSRCT, the differential diagnosis included multiple entities such as neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome,[10] neurofibroma, and schwannoma.[13] Contrary to the other reported cases, our patient`s tumor had an explosive clinical progression within a few months. Given that, there was no evidence of disease elsewhere; our case appears to be the third case of primary BP-DSRCT.

Miwa et al.[13] considered complete resection impossible for the same reasons we did in our case. Only chemotherapy was performed. Forty-six months after the diagnosis, no local relapse or distant metastases were evident. However, no neurologic functionality was described. Mathys et al.[10] also performed an open biopsy, followed by radical resection and adjuvant RT, but no chemotherapy; however, due to aggressive resection, the function of the involved the arm was completely lost.

Multiple firm nodules with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis characterize DSRCT macroscopically. Microscopically, the tumor consists of solid nests of varying size of round or oval malignant cells, combined with vascularized desmoplastic stroma. The cells are uniform with small, round, and vesicular or hyperchromatic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and small amounts of cytoplasm. Areas of necrosis and many mitoses are common.[6] Immunohistochemical analysis is positive for desmin and cytokeratin (both in a paranuclear dot-like pattern), synaptophysin, chromogranin, neurofilament, CD56, WT1, and eventually S100, while myogenin and MyoD1 markers are negative.[3] FISH is essential for the diagnosis, demonstrating a range of translocations that include t (11; 22) (p13; q12 and q11.2) (EWS-WT1 antibody fusion gene) and even t (21; 22) (q22; q12).[2,3,14-16]

The estimated 5-year survival rate for any DSRCT is about 15%.[13] Our case of primary BP-DSRCT responded well to MMT.[8,13] Our patient experienced reduced pain and recovery of motor deficits right after subtotal resection, as well as the disappearance of two lung lesions – which were considered possible metastases – with MMT. Further, exploration of this management algorithm is warranted.

CONCLUSION

We believe that our experience supports MMT for DSRCTs by combining function-preserving subtotal resection followed by chemotherapy and RT of the BP, which resulted in prolonged survival.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Guedes-Corrêa JF, Amorim RP, Pereira MR, Cardoso RS, Costa FD, Bianchi BD, et al. Multimodal treatment of an extremely rare desmoplastic small round cell tumor primary to the brachial plexus – A case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol Int 2019;10:140.

Contributor Information

José Fernando Guedes-Corrêa, Email: neuroguedes@yahoo.com.br.

Rogério Pires Amorim, Email: piresamorim@gmail.com.

Maristella Reis da Costa Pereira, Email: maristellareis@gmail.com.

Rodrigo Salvador Vivas Cardoso, Email: rodrigosalvadorvc@gmail.com.

Felipe D’Almeida Costa, Email: felipedalmeida@yahoo.com.br.

Bruno de Souza Bianchi, Email: brunosbianchir@yahoo.com.br.

Ana Caroline Siquara-de-Souza, Email: anasiquara@gmail.com.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that her name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal her identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ariza-Prota MA, Pando-Sandoval A, Fole-Vázquez D, Casan P. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the lung: A case report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2015;16:112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnoud R, Sabourin JC, Pasquier D, Ranchère D, Bailly C, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of WT1 by desmoplastic small round cell tumor: A comparative study with other small round cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:830–6. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200006000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher C, Montgomery E, Khin T. Biopsy Interpretation of Soft Tissue Tumors. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PC, Mertens F, editors. World Health Organisation Classification of Tumours: Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerald WL, Miller HK, Battifora H, Miettinen M, Silva EG, Rosai J, et al. Intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round-cell tumor. Report of 19 cases of a distinctive type of high-grade polyphenotypic malignancy affecting young individuals. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:499–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerald WL, Rosai J. Case 2. Desmoplastic small cell tumor with divergent differentiation. Pediatr Pathol. 1989;9:177–83. doi: 10.3109/15513818909022347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldblum JR, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Malignant soft tissue tumors of uncertain type. In: Goldblum JR, Folpe AL, Weiss SW, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2013. Ch. 33. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kallianpur AA, Shukla NK, Deo SV, Yadav P, Mudaly D, Yadav R, et al. Updates on the multimodality management of desmoplastic small round cell tumor. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:617–21. doi: 10.1002/jso.22130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lae ME, Roche PC, Jin L, Lloyd RV, Nascimento AG. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular study of 32 tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:823–35. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathys J, Vajtai I, Vögelin E, Zimmermann DR, Ozdoba C, Hewer E, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: A rare cause of a progressive brachial plexopathy. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49:922–7. doi: 10.1002/mus.24165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCormack HM, Horne DJ, Sheather S. Clinical applications of visual analogue scales: A critical review. Psychol Med. 1988;18:1007–19. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700009934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medical Research Council. War Memorandum No. 7. 2nd ed. London: HMSO; 1943. Aids to the Investigation of Peripheral Nerve Injuries; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miwa S, Kitamura S, Shirai T, Hayashi K, Nishida H, Takeuchi A, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumour successfully treated with caffeine-assisted chemotherapy: A case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:3769–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neder L, Scheithauer BW, Turel KE, Arnesen MA, Ketterling RP, Jin L, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the central nervous system: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2009;454:431–9. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stopyra GA. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:782. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-782b-EN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ud Din N, Pekmezci M, Javed G, Horvai AE, Ahmad Z, Faheem M, et al. Low-grade small round cell tumor of the cauda equina with EWSR1-WT1 fusion and indolent clinical course. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:153–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]