Abstract

Objective

In this study of newly incident drinkers (NIDs), we (a) investigate and calibrate measurement equivalence of 7 clinical features of an alcohol dependence syndrome (ADS) across sex and age‐of‐onset subgroups and (b) estimate female–male differences in ADS levels soon after taking the first full drink, with focus on those with first full drink before the 24th birthday.

Methods

The study population is 12‐ to 23‐year‐old NIDs living in the United States (n = 33,561). Calibrated for measurement equivalence, male–female differences in levels of newly incident ADS are estimated for 6 age‐of‐onset subgroups.

Results

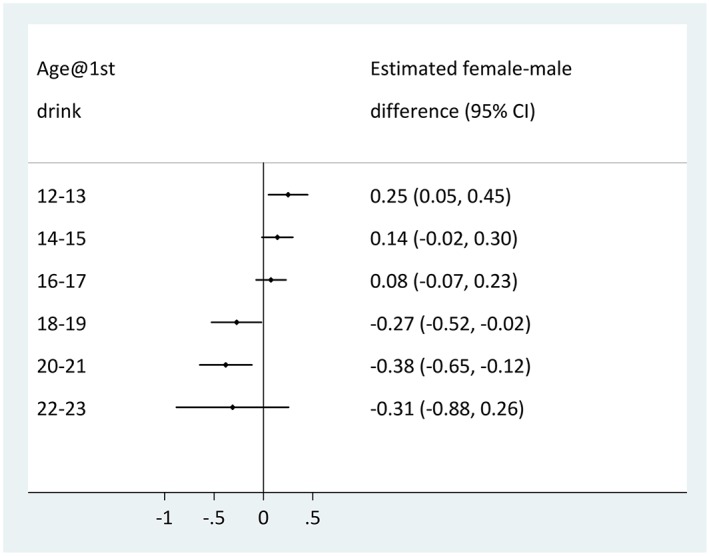

Measurement equivalence is achieved by dropping the “difficulty cutting down” item. Then, among early‐adolescent‐onset NID, females have higher ADS levels (for 12‐ to 13‐year‐old NID: β = .25; 95% CI [0.05, 0.45]). In contrast, when drinking onset is delayed to adulthood, males have higher ADS levels (e.g., for 18‐ to 19‐year‐old NID: β = −.27; 95% CI [−0.52, −0.02]; for 20‐ to 21‐year‐old NID: β = −.38; 95% CI [−0.65, −0.12]).

Conclusions

In the United States, there is female excess in ADS levels measured soon after drinking onset in early adolescence. The traditional male excess is seen when drinking onset occurs after mid‐adolescence. Evidence from other countries will be useful.

Keywords: alcohol dependence syndrome, male–female differences, measurement invariance, United States

1. INTRODUCTION

Alcoholic beverages are among the most commonly consumed psychoactive drugs worldwide and in the United States (e.g., Degenhardt et al., 2008; Wilsnack et al., 2000). According to recent U.S. estimates, 50% of adolescents have taken a first drink by the age of 16 years, and approximately 90% of individuals have had a first drink by the age of 21 years (Cheng, Cantave, & Anthony, 2016a). Among newly incident drinkers, roughly 3% develop an alcohol dependence syndrome (ADS) within 12 months after the first full drink (Cheng, Chandra, Alcover, & Anthony, 2016; Lopez‐Quintero et al., 2011).

1.1. Female–male difference in alcohol drinking and dependence

Female–male differences (FMDs) have been central in alcohol research. FMD issues first surfaced in discussions of measurement of alcohol problems in early social research on drinking norms for men versus women. Early evidence substantiated a “traditional male excess” in the occurrence of drinking‐related problems (e.g., Wilsnack, Wilsnack, Kristjanson, Vogeltanz‐Holm, & Gmel, 2009). Newer evidence, mainly from the United States, discloses a “narrowing of the gender gap” in estimated prevalence of drinking and drinking‐related problems (Keyes, Martins, Blanco, & Hasin, 2010; Slade et al., 2016).

Recently, with focus on the risk of becoming a newly incident drinker and the risk of making a rapid transition to problematic drinking, we found evidence that this traditional “gender gap” might have closed in the United States, with female excess of problems seen among early adolescents. That is, early‐adolescent girls now are more likely to start drinking and are more likely to experience the first heavy drinking episode compared with early‐adolescent boys in the United States (Cheng & Anthony, 2016a, 2017; Cheng, Cantave, & Anthony, 2016b). There also is evidence favoring a female excess risk of rapid transition to alcohol dependence (AD) case status when ADS is assessed as a diagnostic category, but issues of measurement equivalence have resurfaced (Cheng, Chandra, et al., 2016).

1.2. Measurement equivalence in ADS research

The origins of measurement equivalence research in psychiatric epidemiology generally can be traced back to the 1950s–1970s when the “What is a case?” question was emphasized. This case definition question continues to be asked, and the U.S. diagnostic criteria now depart from Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV), with resulting methods complexity for multicountry investigations (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Demyttenaere et al., 2004; Wilsnack et al., 2000).

In its traditions of methods research, psychiatric research has been characterized by widespread appreciation that the sensitivity or specificity of diagnostic assessment tools might not be consistent for population subgroups. Examples of measurement nonequivalence can be found in many domains of neuropsychiatric assessment. To illustrate, in Grimby's (1993) research on older adults, roughly one half of bereaved older adults said they had seen, heard, or talked to a loved one within 1 year after the death, but this experience ordinarily did not qualify as an example of Schneiderian first rank hallucinations. Failure to spell “World” backwards or to recite the “serial sevens” in the Mini‐Mental State Examination can reflect lack of schooling and may not be a manifestation of dementia, delirium, or related individual‐level disease state.

Problems of measurement equivalence and nonequivalence are also relevant when psychiatric epidemiology's focus shifts toward a dimensional conceptualization of psychiatric disturbances. For example, Gallo, Anthony, and Muthén (1994) reapproached the Diagnostic Interview Schedule items used to assess major depression and approached each Diagnostic Interview Schedule item as a manifestation of an underlying latent dimension (“latent trait”) of depression. Working within this dimensional framework, they found that with depression level held constant, older adults (age 65 years and older) were less likely than non‐older adults (18–64 years old) to experience a crucial manifestation of depression (i.e., long‐sustained feelings of being “sad, blue, or depressed”).

The parallel tradition of methods research on alcohol shows recognition that ADS might show gendered manifestations, as well as age‐of‐onset variations (Demyttenaere et al., 2004; Kuhn, 2015; Robins & Cottler, 2004; Schulte, Ramo, & Brown, 2009; Wilsnack & Wilsnack, 1992). For example, some ADS manifestations (e.g., withdrawal) might be highly discriminating for adult drinkers but less discriminating among early‐adolescent drinkers (Harford, Yi, Faden, & Chen, 2009).

A suggested “mechanism” for this kind of measurement nonequivalence is that adult drinkers and early‐adolescent drinkers can differ in their interpretation of ADS assessment items (Morgenstern, DiFranza, Wellman, Sargent, & Hanewinkel, 2016). For example, a “binge” might have one meaning for an adolescent and quite another meaning for older drinkers when no clear definition is provided.

We are not the first to draw attention to issues of this type in field studies of alcohol problems and related disturbances. Muthén and others have made measurement nonequivalence a recurring theme (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010; Caetano & Babor, 2006; Gallo et al., 1994; Gelhorn et al., 2008; Keyes et al., 2010; Kim & Yoon, 2011; Muthen, 1996; Muthen & Asparouhov, 2014). In brief, when the starting point is a unidimensional ADS construct with various items differentiating low versus high ADS levels (slopes or discrimination parameters) at different locations along the ADS dimension (e.g., intercepts or difficulty parameters), it is possible to evaluate a full‐variance (“configural”) model, which allows the intercepts and slopes to vary across subgroups (e.g., males vs. females or age‐of‐onset groups), against an alternative specification of the full‐equivalence (“scalar”) model, which constrains the intercepts and slopes to be equal across subgroups. If evidence favoring measurement equivalence can be established by showing no appreciable difference between the configural and scalar models, a well‐fitting scalar model facilitates the interpretation of subgroup differences because item functioning parameters (such as intercepts and slopes) are held equal across subgroups (Kim & Yoon, 2011; Stark, Chernyshenko, & Drasgow, 2006). When measurement equivalence is neglected, any observed FMD or age‐of‐onset differences can be rendered tentative due to potential differential item functioning in males and females or across age‐of‐onset groups.

1.3. The current study

As mentioned above, the conventional approach toward the investigation of FMD in alcohol problems has emphasized a view of alcohol problems measured in terms of discrete categories (e.g., heavy drinking episode; ADS; e.g., Cheng & Anthony, 2016b; Cheng, Chandra, et al., 2016; Keyes, Grant, & Hasin, 2008; Wilsnack et al., 2000). The complementary but different dimensional approach, as was advocated by Edwards and Gross, generally assumes measurement equivalence. Recast using the latent trait approach, any underlying ADS dimension is tapped by diagnostic assessment items with essentially equivalent performance characteristics (e.g., intercepts and slopes) for all subgroups under study (Rose, Lee, Selya, & Dierker, 2012).

For this study, we completed a formal assessment of measurement equivalence in order to calibrate an ADS assessment. We then estimated FMD variations in the level of an ADS dimension in different age‐of‐onset groups. This work can be distinguished from the just‐cited work by Rose et al. (2012) in three ways: (a) Our modeling is age specific and probes for FMD in ADS levels when drinking starts at 12 to 13 years versus later in adolescence or young adulthood, with due attention to measurement equivalence across sex‐ and age‐of‐onset groups; (b) we formally test for measurement equivalence in ADS (rather than assume measurement equivalence); and (c) we include all newly incident drinkers without restriction to persistence of drinking (i.e., without restriction to drinking during the past 30 days). To be clear, in this study, the elapsed time from the first drink until the ADS assessments is a short interval that never exceeds 12 months. We judge that this research approach constrains (but might not totally eliminate) recall and reporting measurement artifacts that have been found when ADS assessments occur after intervals of 2–3 years or longer (Engels, Knibbe, & Drop, 1997; Kuntsche, Rossow, Engels, & Kuntsche, 2016).

Against this background, the main aim of this study is to estimate FMDs in the escalation of levels of ADS soon after drinking onset in adolescent and young‐adult drinkers. Based on previous findings, our hypothesized expectations are (a) a male excess in the level of ADS (specified as a dimensional construct) in all age groups (Edwards, 1986; Edwards & Gross, 1976) and (b) a larger male excess among adult‐onset drinkers compared with adolescent‐onset drinkers. Alternatively, we consider the idea that larger ADS levels might be found for adolescent female drinkers, compared with adolescent male drinkers, within the first 12 months after drinking onset, in a pattern that reflects recent findings about incidence of becoming a case of categorically defined DSM‐IV AD in the adolescent female subgroup (e.g., Cheng et al., 2016).

Our tight focus on newly incident drinkers represents a sustained attempt to shift focus in FMD research from prevalence differences to incidence differences. It also reflects our concern about early escalation of drinking problems. To the extent that FMD exists, effective public health or clinical tactics for underage female new drinkers will not necessarily be the same as tactics that work for new male drinkers during the postdrink interval when ADS clinical features start to emerge, perhaps before ADS levels progress to a fully formed syndrome.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study population and sample

The study population is specified to represent almost all noninstitutionalized civilian residents aged 12 years and above living in all 50 states and the District of Columbia of the United States, as sampled for National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), with field operations conducted from 2002 to 2014. Each NSDUH multistage probability sampling plan was designed to yield a nationally representative sample with oversampling of 12‐ to 17‐year‐olds. The NSDUH sampling frame included adolescents (including school dropouts and non‐attenders) as well as nonhousehold group quarters such as homeless shelters and college dormitories.

NSDUH participant recruitment is via child assent and parental or adult consent, based upon protocols approved by cognizant human subject protection committees. More than 30,000 12‐ to 23‐year‐old participants are included in each year's NSDUH sample (United States, 2012).

Newly incident drinkers are those who consumed their first full drink during the 12 months prior to the assessment (Cheng, Chandra, et al., 2016). In aggregate, 34,455 12‐ to 23‐year‐old new drinkers were identified, among whom 894 (2.6%) individuals have missing values on all seven clinical features of DSM‐IV AD. Therefore, the analytic sample included 33,561 newly incident drinkers.

2.2. Assessment and measures

NSDUH confidential audio computer‐assisted self‐interviews assessed drinking histories, with questions for newly incident drinkers about the month and year when the first full drink was consumed. Audio computer‐assisted self‐interview is used to promote reliability, accuracy, and truthfulness of participant reports about potentially sensitive behaviors and characteristics.

Key response variables measured in this study are seven preselected clinical features of ADS seen in many contemporary case definitions: “tolerance,” “withdrawal,” “salience,” “difficulty cutting down,” “drinking more than intended,” “drinking despite physical or psychological problems,” and “giving up important activities for drinking” (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). All items are measured on a binary scale (i.e., “yes” or “no”) with options for “don't know” and refusal (“don't know” and “refused” were treated as missing values in analysis). Table S1 lists NSDUH questions for assessment of each clinical feature. All individuals who consumed alcohol for at least 6 days during the 12 months prior to the assessment were asked questions about ADS clinical features. In this study, newly incident drinkers who consumed alcohol for fewer than 6 days are assumed to have experienced none of the ADS clinical features listed above (United States, 2014). We provide a more detailed discussion about this NSDUH measurement assumption in the Supporting Information.

Sex (male–female) and age generally are from the self‐report self‐interview. For the few respondents with nonvalid sex and age items, NSDUH has drawn the information from the dwelling unit rostering information.

2.3. Analysis

For this study, we created 12 subgroups based on sex and age at first full drink (i.e., males and female with age at first full drink at 12–13, 14–15, 16–17, 18–19, 20–21, and 22–23 years). After sample description, we tested measurement equivalence of the seven clinical features as observed variables for a latent ADS construct across these sex and age groups (Gelhorn et al., 2008; Jöreskog, 1971; Martin, Chung, Kirisci, & Langenbucher, 2006). We first used a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model to assess goodness of fit of a one‐dimensional ADS latent construct for each of the 12 subgroups via the following fit indices: root mean square of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990), comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973). Generally accepted rules of thumb are that RMSEA < 0.05 and CFI/TLI > 0.95 indicate reasonably good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Muthen, 1992), with all factor loadings (λ) greater than 0.40 (Ford, MacCallum, & Tait, 1986).

Next, the adjusted chi‐square test was used to compare two nested models: the full equivalence (i.e., scalar) versus full variance (i.e., configural) models (Kim & Yoon, 2011; Stark et al., 2006). A p value < .05 from the adjusted chi‐square test served as our marker for measurement nonequivalence, which prompted inspection of intercepts and slopes to investigate any item with potential differential functioning (Stark et al., 2006). After dropping any item with differential functioning and rechecking of these measurement equivalence issues, we conducted a multiple‐group analysis to estimate FMD in the level of ADS for each of the six age‐of‐onset groups, with weighted least squares mean and variance‐adjusted estimators for estimation (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010). Exploratory analyses to test the assumption of missing completely at random for weighted least squares mean and variance and for greater memory error constraints are described in Supporting Information 1.2 and 1.3. In this study, NSDUH‐constructed analysis weights take into account differential selection probabilities and poststratification adjustment factors.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 reports estimated occurrence of each clinical feature for ADS in each subgroup of newly incident drinkers. In all sex and age subgroups, tolerance and salience are the two most common AD clinical features observed within 12 months after first drink. Other clinical features are relatively rare (i.e., estimated occurrence ≤ 2.0% in most groups). Among female new drinkers, estimated occurrence of ADS clinical features drops with the age of first full drink, whereas no clear pattern is observed for males (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated sex‐specific and onset‐age‐specific occurrence of individual DSM‐IV alcohol dependence clinical features among 12‐ to 23‐year‐old newly incident drinkers

| Panel A. Females | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first full drink | 12–13 (n = 2,276) | 14–15 (n = 5,742) | 16–17 (n = 4,654) | 18–19 (n = 2,729) | 20–21 (n = 2,258) | 22–23 (n = 309) | ||||||

| Clinical feature | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n |

| Salience | 8.7 (0.8) | 195 | 8.6 (0.5) | 518 | 7.1 (0.5) | 325 | 6.2 (0.6) | 171 | 5.2 (0.6) | 123 | 4.0 (1.6) | 12 |

| Drink more than intended | 1.5 (0.4) | 32 | 1.7 (0.2) | 90 | 1.6 (0.2) | 77 | 1.5 (0.3) | 41 | 0.8 (0.2) | 21 | 0.6 (0.3) | 3 |

| Subjectively felt tolerance | 13.0 (1.0) | 280 | 13.0 (0.6) | 698 | 10.4 (0.6) | 499 | 10.2 (0.8) | 267 | 10.2 (0.9) | 210 | 7.9 (2.3) | 22 |

| Withdrawal | 3.6 (0.6) | 60 | 1.6 (0.3) | 94 | 1.1 (0.2) | 50 | 0.9 (0.2) | 20 | 1.1 (0.3) | 26 | 0.4 (0.3) | 3 |

| Give up activities | 1.9 (0.4) | 44 | 1.6 (0.2) | 99 | 1.8 (0.2) | 81 | 1.0 (0.2) | 31 | 0.9 (0.2) | 22 | 1.7 (0.8) | 5 |

| Continue despite problems | 3.3 (0.6) | 67 | 2.1 (0.2) | 126 | 2.0 (0.3) | 95 | 2.0 (0.4) | 57 | 0.9 (0.3) | 22 | 0.9 (0.4) | 4 |

| Difficulty cutting down | 1.8 (0.3) | 36 | 1.4 (0.2) | 79 | 0.9 (0.2) | 49 | 1.1 (0.2) | 37 | 0.9 (0.2) | 17 | 0.3 (0.2) | 2 |

| Panel B. Males | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first full drink | 12–13 (n = 1,753) | 14–15 (n = 4,703) | 16–17 (n = 4,606) | 18–19 (n = 2,529) | 20–21 (n = 1,809) | 22–23 (n = 193) | ||||||

| Clinical feature | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n |

| Salience | 4.9 (0.6) | 94 | 6.1 (0.4) | 298 | 6.9 (0.5) | 315 | 8.8 (0.8) | 199 | 7.7 (.9) | 136 | 6.3 (2.1) | 13 |

| Drink more than intended | 1.1 (0.3) | 19 | 1.2 (0.2) | 57 | 1.4 (0.2) | 60 | 1.4 (0.4) | 36 | 1.6 (.4) | 32 | 0.6 (0.5) | 2 |

| Subjectively felt tolerance | 11.1 (1.0) | 182 | 13.3 (0.6) | 580 | 12.2 (0.7) | 540 | 15.3 (1.0) | 379 | 13.7 (1.1) | 239 | 15.1 (3.7) | 23 |

| Withdrawal | 1.6 (0.4) | 32 | 1.6 (0.3) | 66 | 1.8 (0.3) | 73 | 1.2 (0.4) | 26 | 1.7 (.4) | 24 | 2.6 (1.4) | 4 |

| Give up activities | 1.1 (0.3) | 18 | 1.0 (0.2) | 47 | 1.1 (0.2) | 53 | 1.3 (0.4) | 31 | 1.0 (.3) | 18 | 1.4 (1.0) | 3 |

| Continue despite problems | 1.8 (0.4) | 38 | 2.2 (0.3) | 100 | 2.2 (0.3) | 93 | 2.5 (0.5) | 64 | 1.8 (.4) | 39 | 1.9 (1.2) | 3 |

| Difficulty cutting down | 2.0 (0.4) | 34 | 1.2 (0.2) | 47 | 1.3 (0.2) | 49 | 1.2 (0.3) | 34 | 1.3 (.3) | 29 | 1.1 (0.8) | 2 |

Note. Data from the U.S. National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (unweighted n = 33,561). % = weighted cumulative incidence proportion and standard error; n = unweighted number of cases with each clinical feature. DSM‐IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Fit indices for the CFA one‐dimensional AD model indicate good fit for all subgroups (Table S1). In formal comparison of configural versus scalar modeling (all seven DSM‐IV AD clinical features), the adjusted chi‐square test favors the configural model over the scalar model (χ2 = 74.6, df = 65, p = .040). Studying each intercept and λ estimate across subgroups, we observed considerable variation across subgroups in estimated λ for the difficulty cutting down item. That slope estimate varies from 0.41 in 18‐ to 19‐year‐old males to 0.81 in 12‐ to 13‐year‐old males. With this item dropped, CFA modeling demonstrated a good fit for all subgroups (Table S1), and scalar model measurement equivalence is supported (χ2 = 48.387, df = 44, p = .300). The resulting six‐item scalar equivalence model for the ADS dimension among newly incident drinkers has favorable fit indices (RMSEA = 0.013, 90% CI [0.010, 0.017]; CFI = 0.989; TLI = 0.988), and all loadings are >0.40.

Subsequent multiple‐group analysis with ADS level measured by just six items disclosed a robust FMD among newly incident drinkers who had their first full drink at 12 or 13 years of age, that is, higher ADS level for females (β = .25, 95% CI [0.05, 0.45]). Then FMD is null when drinking onset is at 14 to 15 years (β = .14, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.30]) and at age 16–17 (β = .08, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.23]). Thereafter, a robust male excess in ADS level emerges, as indicated by the negative sign on estimated β and both 95% bounds (18–19 years old: β = −.27, 95% CI [−0.52, −0.02]; 20–21 years old: β = −.38, 95% CI [−0.65, −0.12]; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Estimated female–male differences in the level of alcohol dependence across age groups among 12‐ to 23‐year‐old newly incident drinkers, based on six‐clinical‐feature alcohol dependence syndrome construct (reference group = males at the same age of first drink). Data from the U.S. National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (unweighted n = 33,561)

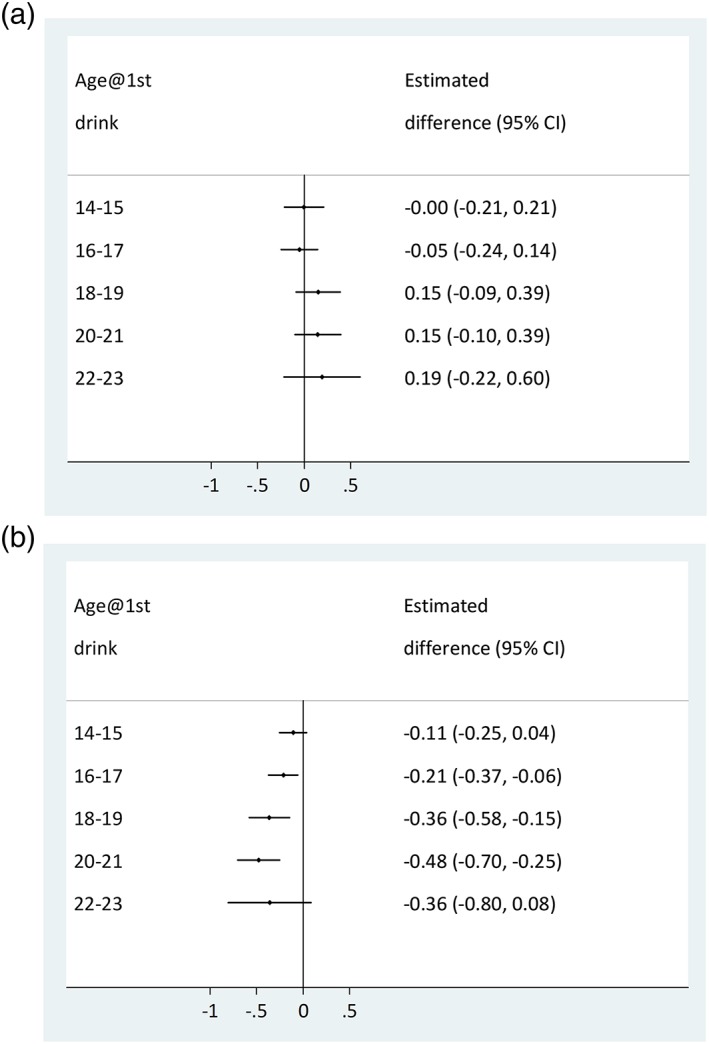

Figure 2 shows sex‐specific variations in ADS level across age‐of‐onset subgroups, as observed within 12 months after the first full drink. ADS levels show no appreciable variation with age‐of‐onset for males. ADS level is largest for the youngest female newly incident drinkers, with an apparent downward shift in ADS level as we look across the female age‐of‐onset subgroups.

Figure 2.

Estimated onset‐age‐specific differences in the level of alcohol dependence for male and female 12‐ to 23‐year‐old newly incident drinkers, based on six‐clinical‐feature alcohol dependence syndrome construct. Data from the U.S. National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (unweighted n = 33,561). (a) Males (n = 15,593; reference: first full drink at 12–13 years of age). (b) Females (n = 17,968; reference: first full drink at 12–13 years of age)

Readers interested in estimates that hold constant the comparison group will find them in Figure S1. In multiple‐group analysis with all seven clinical features (no items dropped), the pattern of estimated FMD is congruent with the pattern shown in Figure 1 for our six‐item model (Figure S2), notwithstanding the apparent measurement nonequivalence problem when the seven‐item approach is used.

4. DISCUSSION

The novel finding of this study is a robustly larger ADS level among early adolescent female drinkers compared with males, observed within the first 12 months after the first full drink. In contrast, when drinking starts in early adulthood, there is a robust male excess in ADS levels. This shift in the valence of the FMD is not due to an age‐related increasing ADS level for males. Rather, for the males, the ADS level observed within 12 months after the first full drink does not seem to vary appreciably with the age of drinking onset. Instead, robust FMD in early adolescence appears to be due to early adolescent female drinkers quickly progressing toward a relatively higher ADS level. Thereafter, looking across female newly incident drinkers, readers will see an age‐related decline in ADS level such that there is no robust FMD at mid‐adolescence, after which the male excess ADS level can be seen.

Our confidence in the FMD pattern is greater for the six‐item assessment of ADS levels, which showed measurement equivalence properties. Nonetheless, our supplementary results show a similar FMD pattern with ADS level assessed via our original seven items. Whereas the difficulty cutting down discrimination parameter estimate (λ) varies considerably across some subgroups (e.g., 0.81 vs. 0.41), this manifestation of measurement nonequivalence apparently was not large enough to disrupt patterning of the FMD estimates in this sample.

Several important study limitations merit attention. The fact that the study is not longitudinal and is cross‐sectional in its research design may seem troublesome, but counterbalanced strengths include (a) the nationally representative sampling with large numbers of newly incident drinkers across onset ages of interest, (b) absence of sample attrition that almost always is present as a missing data mechanism in longitudinal research on ADS (e.g., see Morgenstern et al., 2016), and (c) elimination of measurement reactivity that is faced when the identical ADS assessment is presented to the same individual on multiple occasions (Anthony, 2010).

Another limitation involves the “gating” of AD assessments in NSDUH. A more detailed discussion is presented in the Supporting Information, but in brief, we note a plausible “measurement assumption” that ADS level might be negligible among new drinkers with fewer than six separate days of alcohol consumption in the lifetime drinking history.

Finally, we draw attention to our conceptualization of ADS as a dimensional variable and our deliberate omission of NSDUH items on “troubled drinking” and social maladaptation secondary to alcohol experiences (e.g., getting into trouble with the family). Responses to the omitted items are heavily norm and context dependent and can create both conceptual and measurement difficulties in drug dependence research, especially in studies of “underage” drinking and other “precocious” drug onsets (Anthony, 2010; Edwards, 2012; Martin et al., 2006). An important example for research on FMDs can be seen in what often is greater familial strife when it is the teen daughter who drinks on her own as opposed to the teen son who drinks on his own. Chung, Martin, Armstrong, and Labouvie (2002) also draw attention to measurement issues of this type. More importantly, this specification is consistent with the original ADS conceptualization in the tradition of Edwards and Gross (1976), which placed emphasis on clinical features of the type listed in Table 1 and did not stress alcohol‐attributable social maladaptation.

Notwithstanding limitations such as these, the study findings are of interest. Given that male and female newly incident drinkers at different ages can have different interpretations of the same word and might understand ADS concepts differently, it is reassuring to see measurement equivalence when ADS is measured using six of the seven ADS clinical features assessed in this study. One result should be a greater understanding of measurement issues previously discussed in research on subgroup variations in ADS levels among newly incident drinkers, but not addressed directly with measurement equivalence modeling (McBride & Cheng, 2011; Rose et al., 2012), and in future investigations.

Our discovery of difficulty cutting down as a problematic ADS item merits some discussion. We cannot claim that this item should be dropped from ADS assessments in all instances; this might be problematic in early‐adult newly incident drinkers specifically or perhaps just in the United States. In this study with an extremely large sample across the normative drinking onset age distribution, we were able to detect age‐of‐onset‐related variation in the latent structure's λ parameter estimates for this item, but otherwise, there was no substantial difference between the configural and scalar models that we fit to the data. If future research confirms this kind of measurement issue with difficulty cutting down items, a mixed methods approach is indicated, perhaps with questions about motivations for trying to cut down (e.g., to lose weight). Qualitative studies of underage newly incident drinkers should prove to be useful.

At this early stage of research on FMD among newly incident drinkers, speculation about origins of the observed variations in FMDs of ADS level across age‐of‐onset subgroups should cover a broad range, including sex‐specific genetic susceptibility traits, hormone levels regulating ethanol response, learned social roles and customs, and personality traits (Kuhn, 2015; Schulte et al., 2009). In a series of prior studies on newly incident drinkers in the United States, we have found an early‐adolescent female excess in drinking onset and in transitions from drinking to first heavy drinking episode (Cheng & Anthony, 2016b; Cheng, Cantave, et al., 2016b). For DSM‐IV AD framed as a categorical outcome, the early‐adolescent FMD was not robust but favored a female excess (Cheng, Chandra, et al., 2016). It is not immediately clear whether the observed early‐adolescent female excess in ADS level is determined by the same influences that shape these other drinking phenomena. It is possible that different mechanisms come into play in relation to these conceptually separable but empirically interdependent drinking behaviors and response variables.

Although we are left with an incomplete understanding of the observed variations in FMDs in ADS levels across the age‐of‐onset gradient studied here, public health implications of drinking onsets during adolescence are clear. At least within the United States, the first year after drinking onset is an interval during which an ADS can start to emerge and to escalate (McBride & Cheng, 2011), with what might be faster escalation in ADS level for female newly incident drinkers in early adolescence, with male excess at later onset ages. As such, the interval soon after drinking onset may be a crucial one for public health outreach and intervention. Early‐onset ADS is associated with poorer health and social outcomes, including specific consequences for young girls such as becoming unintentionally pregnant and risky sexual behaviors (Kandel, Chen, Warner, Kessler, & Grant, 1997; Moss, Chen, & Yi, 2014; Schuckit, 2009).

In the tobacco control field, the concept of “prevescalation” has been introduced to complement (a) “primary prevention” of newly incident smoking and (b) “treatment” of already escalated smoking frequency and clinically recognizable tobacco dependence syndromes (Dishion & Andrews, 1995; Niaura, 2017; Piper et al., 2017). This concept of prevescalation also is pertinent in alcohol and other drug research and in public health program planning for newly incident users as they accumulate precursor, prodromal, or clinical features of dependence or addiction and move along dimensions toward fully formed syndromes. Here, we see that across all sex and age groups under study, tolerance and salience are the two most common clinical features encountered quickly after first full drink. When parents, peers, teachers, and pediatricians become aware that adolescents have started “drinking on their own” and have been increasing their alcohol consumption or spending more time engaging in drinking‐related activities, it may be time to ask questions about salience and tolerance and to consider noninvasive brief interventions with a capacity to prevent an escalation toward the fully formed ADS as well as secondary AD‐related consequences of the type just mentioned (Amaro et al., 2010). The observed distinctive FMDs and age‐of‐onset patterns for ADS levels may signify a need to adapt public health interventions to different audiences and to modify the nature or intensity of interventions in relation to sex and age (Brady, Grice, Dustan, & Randall, 1993; Kuhn, 2015; Schulte et al., 2009).

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Authors have no conflict of interest related to this study. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Michigan State University, the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The study is supported by funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants K05DA015799 (to J. C. A.) and T32DA021129 (to H. G. C.), as well as Michigan State University.

Supporting information

Table S1. Items assessing clinical features of DSM‐IV alcohol dependence in the United States National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014.

Table S2. Fit indices of the one‐factor confirmatory factor analysis model for alcohol dependence for each subgroup. Data from the United States National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (Unweighted n = 33,561).

Table S3. Likelihood ratio chi‐square test for observed missingness at random, based on 6‐clinical feature alcohol dependence syndrome construct. Data from the United States National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (Unweighted n = 33,561).

Table S4. Estimated occurrence of DSM‐IV alcohol dependence clinical features among 12‐to‐23‐year‐old newly incident drinkers who had their first full drink within the six months prior to the assessment. Data From the United States National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (Unweighted n = 13,536).

Supporting Information 1.1 Six Drinking Day ‘Gating’ Issue

Supporting Information 1.2 Exploratory Analyses on Observed Missing at Random

Supporting Information 1.3 Exploratory Analyses With Further Constrained Recall Period

Figure S1. Estimated differences in the level of alcohol dependence across sex‐ and age‐of‐onset groups among 12‐to‐23‐year‐old newly incident drinkers, based on 6‐clinical‐feature alcohol dependence syndrome construct. Data from the United States National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (Unweighted n = 33,561).

Figure S2. Estimated differences in the level of alcohol dependence across sex‐ and age‐of‐onset groups among 12‐to‐23‐year‐old newly incident drinkers, based on 7‐clinical‐feature alcohol dependence syndrome construct. Data from the United States National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (Unweighted n = 33,561).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, for making the data publicly available. This work was supported by the United States National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA T32DA021129 [H. G. C.] and K05DA015799 [J. C. A.]) and Michigan State University. We wish to thank Dr. Tenko Raykov and Dr. Orla McBride for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Cheng HG, Anthony JC. Female–male differences in alcohol dependence levels: Evidence on newly incident adolescent and young‐adult drinkers in the United States, 2002–2014. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018;27:e1717 10.1002/mpr.1717

REFERENCES

- Amaro, H. , Reed, E. , Rowe, E. , Picci, J. , Mantella, P. , & Prado, G. (2010). Brief screening and intervention for alcohol and drug use in a college student health clinic: Feasibility, implementation, and outcomes. Journal of American College Health, 58, 357–364. 10.1080/07448480903501764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, J. C. (2010). Novel phenotype issues raised in cross‐national epidemiological research on drug dependence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1187(1), 353–369. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05419.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov, T. , & Muthén, B. (2010). Weighted least squares estimation with missing data. Mplus technical appendix. Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com/download/GstrucMissingRevision.pdf

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady, K. T. , Grice, D. E. , Dustan, L. , & Randall, C. (1993). Gender differences in substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry, 150(11), 1707–1711. Retrieved http://from. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8214180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano, R. , & Babor, T. F. (2006). Diagnosis of alcohol dependence in epidemiological surveys: An epidemic of youthful alcohol dependence or a case of measurement error? Addiction, 101, 111–114. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H. G. , & Anthony, J. C. (2016a). A new era for drinking? Epidemiological evidence on adolescent male–female differences in drinking incidence in the United States and Europe. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52, 117–126. 10.1007/s00127-016-1318-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H. G. , & Anthony, J. C. (2016b). Does our legal minimum drinking age modulate risk of first heavy drinking episode soon after drinking onset? Epidemiological evidence for the United States, 2006‐2014. PeerJ, 4, e2153 10.7717/peerj.2153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H. G. , & Anthony, J. C. (2017). Male–female differences in the onset of heavy episodic drinking soon after first full drink in contemporary United States: From early adolescence to young adulthood. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H. G. , Cantave, M. D. , & Anthony, J. C. (2016a). Alcohol experiences viewed mutoscopically: Newly incident drinking of twelve‐ to twenty‐five‐year‐olds in the United States, 2002‐2013. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77(3), 405–412. 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H. G. , Cantave, M. D. , & Anthony, J. C. (2016b). Taking the first full drink: Epidemiological evidence on male–female differences in the United States. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(4), 816–825. 10.1111/acer.13028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H. G. , Chandra, M. , Alcover, K. C. , & Anthony, J. C. (2016). Rapid transition from drinking to alcohol dependence among adolescent and young‐adult newly incident drinkers in the United States, 2002‐2013. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 168, 61–68. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, T. , Martin, C. S. , Armstrong, T. D. , & Labouvie, E. W. (2002). Prevalence of DSM‐IV alcohol diagnoses and symptoms in adolescent community and clinical samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(5), 546–554. 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt, L. , Chiu, W. T. , Sampson, N. , Kessler, R. C. , Anthony, J. C. , Angermeyer, M. , … Wells, J. E. (2008). Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Medicine, 5(7), e141 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere, K. , Bruffaerts, R. , Posada‐Villa, J. , Gasquet, I. , Kovess, V. , Lepine, J. P. , … Chatterji, S. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA, 291(21), 2581–2590. 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion, T. J. , & Andrews, D. W. (1995). Preventing escalation in problem behaviors with high‐risk young adolescents: Immediate and 1‐year outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 538–548. 10.1037/0022-006X.63.4.538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, G. (1986). The alcohol dependence syndrome: A concept as stimulus to enquiry. British Journal of Addiction, 81(2), 171–183. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, G. (2012). “The evil genius of the habit”: DSM‐5 seen in historical context. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(4), 699–701. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22630808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, G. , & Gross, M. M. (1976). Alcohol dependence: Provisional description of a clinical syndrome. British Medical Journal, 1(May), 1058–1061. 10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels, R. C. M. E. , Knibbe, R. A. , & Drop, M. J. (1997). Inconsistencies in adolescents' self‐reports of initiation of alcohol and tobacco use. Addictive Behaviors, 22(5), 613–623. 10.1016/S0306-4603(96)00067-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J. K. , MacCallum, R. C. , & Tait, M. (1986). The application of exploratory factor analysis in applied psychology: A critical review and analysis. Personnel Psychology, 39(2), 291–314. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1986.tb00583.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, J. J. , Anthony, J. C. , & Muthén, B. O. (1994). Age differences in the symptoms of depression: A latent trait analysis. Journal of Gerontology, 49(6), P251–P264. 10.1093/geronj/49.6.P251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelhorn, H. , Hartman, C. , Sakai, J. , Stallings, M. , Young, S. , Rhee, S. H. , … Crowley, T. (2008). Toward DSM‐V: An item response theory analysis of the diagnostic process for DSM‐IV alcohol abuse and dependence in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(11), 1329–1339. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318184ff2e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimby, A. (1993). Bereavement among elderly people: Grief reactions, post‐bereavement hallucinations and quality of life. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 87(1), 72–80. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford, T. C. , Yi, H. Y. , Faden, V. B. , & Chen, C. M. (2009). The dimensionality of DSM‐IV alcohol use disorders among adolescent and adult drinkers and symptom patterns by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(5), 868–878. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00910.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. , & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criterion for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1971). Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika, 36(4), 409–426. 10.1007/BF02291366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel, D. , Chen, K. , Warner, L. A. , Kessler, R. C. , & Grant, B. (1997). Prevalence and demographic correlates of symptoms of last year dependence on alcohol, nicotine, marijuana and cocaine in the U.S. population. Drug Alcohol Depend, 44(1), 11–29. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9031816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, K. M. , Grant, B. F. , & Hasin, D. S. (2008). Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 93(1–2), 21–29. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, K. M. , Martins, S. S. , Blanco, C. , & Hasin, D. S. (2010). Telescoping and gender differences in alcohol dependence: New evidence from two national surveys. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 969–976. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E. S. , & Yoon, M. (2011). Testing measurement invariance: A comparison of multiple‐group categorical CFA and IRT. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 18(2), 212–228. 10.1080/10705511.2011.557337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, C. (2015). Emergence of sex differences in the development of substance use and abuse during adolescence. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 153, 55–78. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche, E. , Rossow, I. , Engels, R. , & Kuntsche, S. (2016). Is “age at first drink” a useful concept in alcohol research and prevention? We doubt that. Addiction, 111(6), 957–965. 10.1111/add.12980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez‐Quintero, C. , de los Cobos, J. P. , Hasin, D. S. , Okuda, M. , Wang, S. , Grant, B. F. , & Blanco, C. (2011). Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115(1–2), 120–130. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C. S. , Chung, T. , Kirisci, L. , & Langenbucher, J. W. (2006). Item response theory analysis of diagnostic criteria for alcohol and cannabis use disorders in adolescents: Implications for DSM‐V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(4), 807–814. 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride, O. , & Cheng, H. G. (2011). Exploring the emergence of alcohol use disorder symptoms in the two years after onset of drinking: Findings from the National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. Addiction, 106(3), 555–563. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03242.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, M. , DiFranza, J. R. , Wellman, R. J. , Sargent, J. D. , & Hanewinkel, R. (2016). Relationship between early symptoms of alcohol craving and binge drinking 2.5 years later. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 160, 183–189. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss, H. B. , Chen, C. M. , & Yi, H. Y. (2014). Early adolescent patterns of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana polysubstance use and young adult substance use outcomes in a nationally representative sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 136, 51–62. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B. , & Asparouhov, T. (2014). IRT studies of many groups: The alignment method. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. (AUG). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen, B. O. (1992). Latent variable modeling in epidemiology. Alcohol Health & Research World, 16(4), 286–292. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen, B. O. (1996). Psychometric evaluation of diagnostic criteria: Application to a two‐dimensional model of alcohol abuse and dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 41(2), 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura, R. (2017). Communicating differences in tobacco product risks: Timing is of the essence. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 388–389. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper, M. E. , Schlam, T. R. , Cook, J. W. , Smith, S. S. , Bolt, D. M. , Loh, W.‐Y. , … Baker, T. B. (2017). Toward precision smoking cessation treatment I: Moderator results from a factorial experiment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 171, 59–65. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins, L. N. , & Cottler, L. B. (2004). Making a structured psychiatric diagnostic interview faithful to the nomenclature. American Journal of Epidemiology, 160(8), 808–813. 10.1093/aje/kwh283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, J. S. , Lee, C. T. , Selya, A. S. , & Dierker, L. C. (2012). DSM‐IV alcohol abuse and dependence criteria characteristics for recent onset adolescent drinkers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 124(1–2), 88–94. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit, M. A. (2009). Alcohol‐use disorders. Lancet, 373(9662), 492–501. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60009-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, M. T. , Ramo, D. , & Brown, S. A. (2009). Gender differences in factors influencing alcohol use and drinking progression among adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 535–547. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade, T. , Chapman, C. , Swift, W. , Keyes, K. , Tonks, Z. , & Teesson, M. (2016). Birth cohort trends in the global epidemiology of alcohol use and alcohol‐related harms in men and women: Systematic review and metaregression. BMJ Open, 6(10), e011827 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, S. , Chernyshenko, O. S. , & Drasgow, F. (2006). Detecting differential item functioning with confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: Toward a unified strategy. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1292–1306. 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2), 173–180. 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, L. R. , & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1–10. 10.1007/BF02291170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2012). Comparing and evaluating youth substance use estimates from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and other surveys. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2014). National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of methodological studies, 1971–2014. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHmethodsSummary2013/NSDUHmethodsSummary2013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack, R. W. , Vogeltanz, N. D. , Wilsnack, S. C. , Harris, T. R. , Ahlstrom, S. , Bondy, S. , … Weiss, S. (2000). Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: Cross‐cultural patterns. Addiction, 95(2), 251–265. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10723854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack, R. W. , & Wilsnack, S. C. (1992). Women, work, and alcohol: Failures of simple theories. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 16(2), 172–179. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1590537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack, R. W. , Wilsnack, S. C. , Kristjanson, A. F. , Vogeltanz‐Holm, N. D. , & Gmel, G. (2009). Gender and alcohol consumption: Patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction, 104(9), 1487–1500. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Items assessing clinical features of DSM‐IV alcohol dependence in the United States National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014.

Table S2. Fit indices of the one‐factor confirmatory factor analysis model for alcohol dependence for each subgroup. Data from the United States National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (Unweighted n = 33,561).

Table S3. Likelihood ratio chi‐square test for observed missingness at random, based on 6‐clinical feature alcohol dependence syndrome construct. Data from the United States National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (Unweighted n = 33,561).

Table S4. Estimated occurrence of DSM‐IV alcohol dependence clinical features among 12‐to‐23‐year‐old newly incident drinkers who had their first full drink within the six months prior to the assessment. Data From the United States National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (Unweighted n = 13,536).

Supporting Information 1.1 Six Drinking Day ‘Gating’ Issue

Supporting Information 1.2 Exploratory Analyses on Observed Missing at Random

Supporting Information 1.3 Exploratory Analyses With Further Constrained Recall Period

Figure S1. Estimated differences in the level of alcohol dependence across sex‐ and age‐of‐onset groups among 12‐to‐23‐year‐old newly incident drinkers, based on 6‐clinical‐feature alcohol dependence syndrome construct. Data from the United States National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (Unweighted n = 33,561).

Figure S2. Estimated differences in the level of alcohol dependence across sex‐ and age‐of‐onset groups among 12‐to‐23‐year‐old newly incident drinkers, based on 7‐clinical‐feature alcohol dependence syndrome construct. Data from the United States National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2014 (Unweighted n = 33,561).