Significance

Many cancer patients are treated with radiation therapy. For some tumors, addition of radiosensitizing chemotherapy improves local control and survival. Some patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy exhibit a decline in peripheral neutrophils, leading clinicians to delay radiation treatments or administer colony-stimulating factors to promote neutrophil recovery, but the role of neutrophils in mediating radiation response is controversial. Here, we show that elevated neutrophil levels are associated with poor local control and survival in cervical cancer patients treated with definitive chemoradiation. Furthermore, in a genetically engineered mouse model of sarcoma, we demonstrate that genetic and antibody-mediated depletion of neutrophils increases radiosensitivity and decreases a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) transcriptional program. Our results indicate that neutrophils promote tumor resistance to radiotherapy.

Keywords: radiation therapy, cancer biology, neutrophil, radiosensitivity, genetically engineered mouse model

Abstract

Nearly two-thirds of cancer patients are treated with radiation therapy (RT), often with the intent to achieve complete and permanent tumor regression (local control). RT is the primary treatment modality used to achieve local control for many malignancies, including locally advanced cervical cancer, head and neck cancer, and lung cancer. The addition of concurrent platinum-based radiosensitizing chemotherapy improves local control and patient survival. Enhanced outcomes with concurrent chemoradiotherapy may result from increased direct killing of tumor cells and effects on nontumor cell populations. Many patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy exhibit a decline in neutrophil count, but the effects of neutrophils on radiation therapy are controversial. To investigate the clinical significance of neutrophils in the response to RT, we examined patient outcomes and circulating neutrophil counts in cervical cancer patients treated with definitive chemoradiation. Although pretreatment neutrophil count did not correlate with outcome, lower absolute neutrophil count after starting concurrent chemoradiotherapy was associated with higher rates of local control, metastasis-free survival, and overall survival. To define the role of neutrophils in tumor response to RT, we used genetic and pharmacological approaches to deplete neutrophils in an autochthonous mouse model of soft tissue sarcoma. Neutrophil depletion prior to image-guided focal irradiation improved tumor response to RT. Our results indicate that neutrophils promote resistance to radiation therapy. The efficacy of chemoradiotherapy may depend on the impact of treatment on peripheral neutrophil count, which has the potential to serve as an inexpensive and widely available biomarker.

Nearly 4 in 10 Americans will develop cancer in their lifetimes, and over half of these patients will be treated with radiation therapy (1). For cancer types such as breast cancer and soft tissue sarcoma, adjuvant radiotherapy is often used to improve local control after surgical resection (2–4). For other malignancies, such as locally advanced cervical cancer, head and neck cancer, and lung cancer, radiotherapy is the primary modality used to achieve local control (5–7). Administration of concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy during 6 to 7 wk of daily radiation therapy for these cancers improves local control and survival over radiation alone (8–10). Concurrent chemotherapy may enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy through direct effects on tumor cells by causing increased DNA damage, but may also indirectly sensitize tumors to radiation therapy by affecting nontumor cell populations.

Neutrophils, the most common circulating white blood cell, are some of the earliest cells to respond to sites of tissue injury and infection (11). Neutrophils are present in the microenvironment of most solid tumors (11–16), and a pan-cancer study of 25 malignancies demonstrated that tumor-associated neutrophil gene expression signatures independently predicted poor patient survival (17). Moreover, in 1,233 patients with a number of cancer types treated with curative-intent radiation therapy, baseline blood neutrophil count >7 × 103/mL correlated with worse overall survival after 3 y (18). In a retrospective review of patients with lung cancer and esophageal cancer, high neutrophil counts were associated with decreased overall survival, but also with more advanced clinical disease (19). These studies demonstrate a correlation between neutrophil counts and patient outcomes, but whether neutrophils directly contribute to tumor development, progression, and therapeutic resistance or are simply a biomarker for aggressive disease remains unclear.

Preclinical studies have suggested that tumor-associated neutrophils can have both protumor and antitumor effects through many mechanisms, including roles in immunity, angiogenesis, and tumor cell proliferation (11, 20–23). The role of neutrophils in mediating radiation response remains controversial. In some transplant tumor models, neutrophils have been reported to infiltrate the tumor microenvironment after focal irradiation and improve radiation response (21). In contrast, other studies in transplant tumor models have shown that myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which can arise from both neutrophils and monocytes, can promote radiation resistance (24). However, neutrophils from transplanted tumor models and genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) have distinct migratory and immunosuppressive capabilities (25). Therefore, neutrophil activity in transplanted tumor model systems may not fully recapitulate their effects in human cancers.

To investigate the contribution of neutrophils to radiation response, we compared the outcomes of cervical cancer patients treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy to blood neutrophil counts before and during treatment. Although baseline neutrophil counts did not correlate with outcome, patients with higher neutrophil levels 1 wk after starting concurrent chemoradiotherapy had worse local control, metastasis-free survival, and overall survival. To test directly whether neutrophils contribute to the response of autochthonous tumors to radiation therapy, we used a GEMM of sarcoma (26) driven by mutations frequently found in human cancer: activation of oncogenic KrasG12D and loss of both tumor suppressor Trp53 alleles. Using both genetic and pharmacological approaches, neutrophil depletion prior to radiation therapy led to an improved radiation response and was associated with suppression of a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) transcriptional program in tumor cells. Our results indicate that neutrophils promote resistance to radiation therapy and suggest that decreasing neutrophils may be an important mechanism by which chemotherapy contributes to the efficacy of concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Results

Neutrophil Levels Correlate with Outcomes in Cervical Cancer Patients Treated with Radiation Therapy.

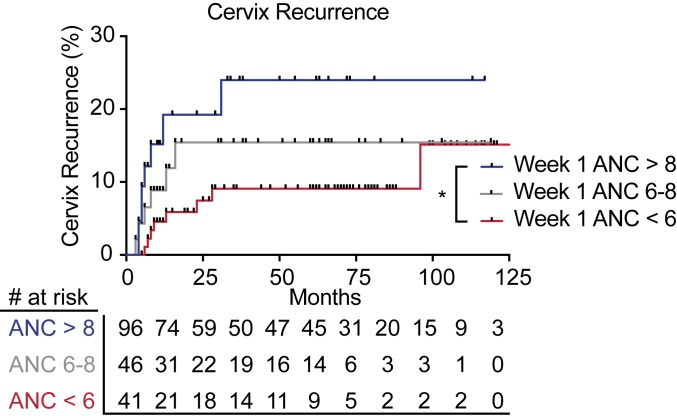

To begin to evaluate the clinical significance of neutrophils in locally advanced cervical cancer, a disease treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy, we first examined data from The Cancer Genome Atlas Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Endocervical Adenocarcinoma (TCGA-CESC). Using CIBERSORT analysis (27) of tumor pretreatment RNA sequencing data from cervical cancer patients who received radiation therapy, we found that the presence of a neutrophil gene expression signature was significantly associated with poor survival (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). We next sought to examine the relationship between circulating blood neutrophils and tumor control in cervical cancer patients who received definitive radiation therapy with concurrent cisplatin chemotherapy (no surgical resection). We retrospectively reviewed a cohort of 278 cervical cancer patients treated with definitive chemoradiation at a single institution from 2006 to 2017 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Baseline patient and tumor characteristics for this cohort are shown in SI Appendix, Table S1. Although baseline absolute neutrophil count (ANC) did not correlate with outcomes, high ANC at week 1, week 3, and weeks 6 to 8 of treatment was associated with local recurrence in the cervix (SI Appendix, Table S2). Elevated ANC during week 1 of treatment was also significantly associated with pelvic recurrence, distant recurrence outside of the pelvis, and cancer death (SI Appendix, Table S2). We used Kaplan–Meier analysis to compare outcomes for patients with ANC > 8 × 103/mL, ANC 6–8 × 103/mL, and ANC < 6 × 103/mL. Patients with elevated ANC (ANC > 8 × 103/mL) during the first week of chemoradiotherapy had significantly higher rates of cervix recurrence (Fig. 1), pelvic recurrence, distant recurrence, and cancer-specific mortality (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A–C). Higher week 1 ANC levels during chemoradiotherapy remained associated with cervix recurrence (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.15, 95% CI 1.04–1.27, P = 0.006), any pelvic recurrence (HR = 1.14, 95% CI 1.04–1.25, P = 0.005), and cervical cancer cause-specific survival (HR = 1.12, 95% CI 1.03–1.19, P = 0.007) on multivariable analysis, even after adjusting for the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique, FIGO) stage, initial metabolic tumor volume by positron emission tomography (PET), regional lymph nodes detected by PET, and hemoglobin levels (SI Appendix, Tables S3–S6).

Fig. 1.

Neutrophils correlate with poor outcomes after chemoradiotherapy in cervical cancer patients. Association between week 1 ANC levels (ANC > 8: blue; ANC 6–8: gray; ANC < 6: red) and local cervix recurrence for patients treated with chemoradiotherapy. Data were calculated with the Kaplan–Meier method and analyzed by the log-rank test (*P = 0.02).

Bone Marrow-Derived Cells Promote Radiation Resistance.

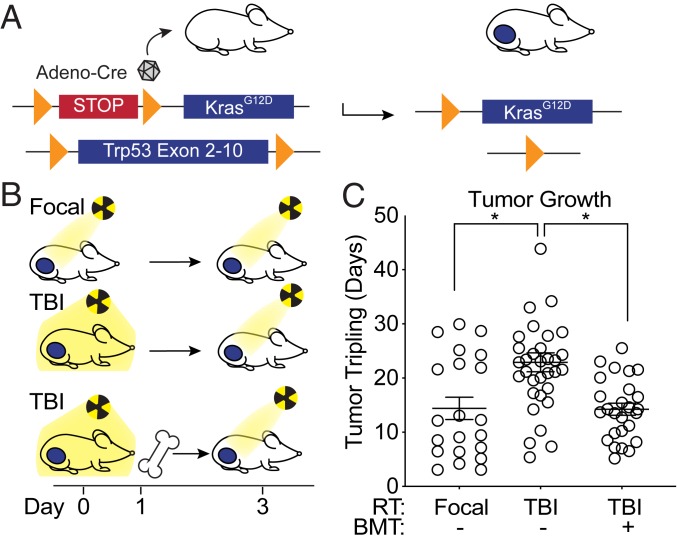

To begin to test whether the immune system plays a role in the efficacy of radiation therapy, we utilized a GEMM of soft tissue sarcoma. This model enables complementary genetic and pharmacologic manipulation of multiple cell types in a single tumor model with an intact immune system, which would not be possible in xenograft models. We generated autochthonous soft tissue sarcomas by injecting an adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase into the gastrocnemius muscle of KrasLSL-G12D/+, Trp53flox/flox (KPflox) genetically engineered mice to activate a conditional mutation in oncogenic KrasG12D and delete both alleles of Trp53 (Fig. 2A). We then compared the radiation response of primary sarcomas in KPflox mice with or without immune cell depletion (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) by total body irradiation (TBI). When tumors measured ∼70 to 150 mm3, mice were treated with either a sublethal dose of 5 Gy TBI or 5 Gy image-guided focal radiation therapy to the tumor-bearing leg, followed 3 d later (at the time of maximal leukodepletion in mice treated with TBI) with an additional 15 Gy irradiation to the tumor-bearing leg in each group (Fig. 2B). Although mice in both groups received a total of 20 Gy to the tumor, TBI significantly enhanced tumor growth delay after focal tumor irradiation (Fig. 2C), suggesting that a bone marrow-derived cell population may mediate radiation resistance in this model. To further test whether immune cells mediate radiation resistance in primary sarcomas, a third cohort of tumor-bearing mice received 6 Gy TBI, followed 1 d later by a bone marrow transplant (BMT) from an unirradiated tumor-naive donor mouse and 14 Gy focal tumor irradiation 2 d later (Fig. 2 B and C). While immune cell depletion with TBI enhanced the efficacy of radiation therapy, BMT after TBI restored radiation resistance, demonstrating that radiation response in KPflox mice is mediated by a bone marrow-derived cell population.

Fig. 2.

Bone marrow-derived cells promote resistance to radiation therapy in primary sarcomas. (A) Genetic strategy to activate oncogenic KrasG12D and delete Trp53 alleles in tumor cells by Cre-mediated recombination at LoxP sites (orange arrows). (B) Schema of treatment. Mice received focal tumor or total body irradiation (TBI) (day 0). One day later, mice in the TBI with bone marrow transplant (BMT) group received BMT. On day 3, all groups received focal radiation to the tumor. (C) Time to tumor tripling for mice which received focal RT (n = 21), TBI without BMT (n = 33), or TBI with BMT (n = 26). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests for comparisons of focal RT without BMT vs. TBI without BMT (P = 0.0021) and comparison of TBI without BMT vs. TBI with BMT (P = 0.0008).

As neutrophils are highly abundant within bone marrow (28) and have been reported to infiltrate allograft tumors after radiation treatment (21), we sought to examine whether neutrophils were among the bone marrow-derived cell populations contributing to radiation resistance (Fig. 2C). We utilized dual recombinase technology (29–31) to generate primary sarcomas in mice with genetically engineered fluorescent lineage tracing of neutrophils (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B and Table S7). In transgenic mice with Cre recombinase expressed from the human MRP8 promoter (MRP8Cre) (32), which is active in granulocytes and granulocytic progenitors, and a Cre-inducible fluorescent tdTomato reporter (R26LSL-tdTomato/+) (33), neutrophils are labeled with the fluorescent protein tdTomato. We crossed these mice to KrasFSF-G12D/+; Trp53FRT/FRT (KPFRT) mice, in which injection of an adenovirus expressing FlpO recombinase (Adeno-FlpO) into the gastrocnemius muscle initiates sarcomagenesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). Tumor-infiltrating immune cells from these KrasFSF-G12D/+; Trp53FRT/FRT; MRP8Cre; R26LSL-tdTomato/+ (KPMT) mice were analyzed by flow cytometry and histology (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 C and D), revealing that the majority of tumor-infiltrating MRP8+ tdTomato+ cells were CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils.

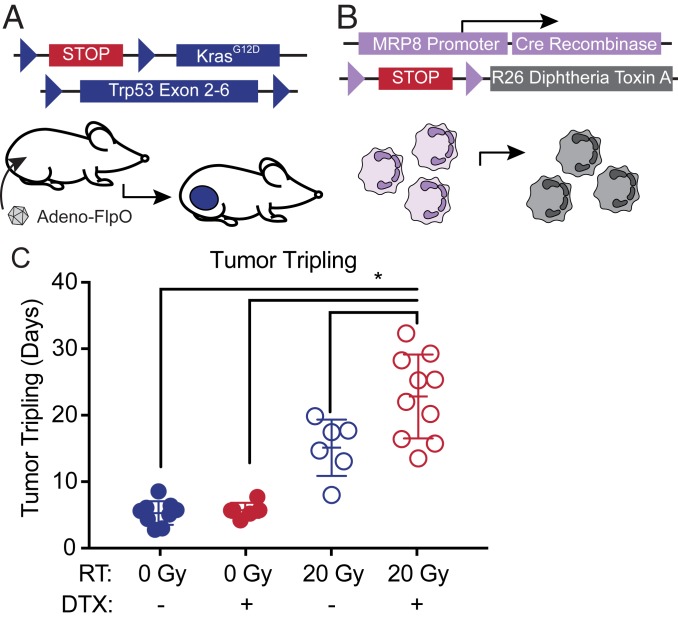

Genetic Depletion of Neutrophils Improves Radiation Response.

To test the role of neutrophils in the radiation response, we crossed KrasFSF-G12D/+; Trp53FRT/FRT; MRP8Cre (KPM) mice to R26LSL-DTX/+ mice (34) carrying a Cre-activatable allele that drives expression of diphtheria toxin subunit A (DTX) from the Rosa26 locus to cause depletion of the MRP8 lineage. Sarcomagenesis was initiated by injection of Adeno-FlpO into the gastrocnemius muscle of mice with depleted neutrophils (KrasFSF-G12D/+; Trp53FRT/FRT; MRP8Cre; R26LSL-DTX/+) (KPMD) or littermate mice (KPM) with intact neutrophils because they lacked the R26LSL-DTX/+ allele (Fig. 3 A and B and SI Appendix, Table S7). We confirmed that MRP8Cre-mediated DTX expression efficiently depleted circulating neutrophils but not other immune cell types in nontumor-bearing KPMD mice and tumor-infiltrating neutrophils in tumor-bearing mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). When sarcomas reached 70 to 150 mm3, mice were randomized to receive 0 or 20 Gy focal radiation therapy to the tumor. After irradiation, sarcomas were measured 3 times weekly by caliper measurement to determine the time for tumor tripling relative to initial volume at the time of radiation. Neutrophil depletion did not affect tumor onset or tumor growth in the absence of radiation therapy (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). As expected, a single 20-Gy radiation treatment caused a significant growth delay in mice with and without neutrophils (Fig. 3C). However, time to tumor tripling was prolonged in KPMD mice compared to neutrophil-intact KPM mice (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S7B). Because previous data demonstrated a role for myeloid cells in vasculogenesis-mediated radiation resistance (35), we analyzed microvessel density 7 d after radiation therapy. Tumors from neutrophil-depleted and neutrophil-intact mice had similar microvessel density and vessel pericyte coverage (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A–D), suggesting that neutrophils were acting through a different mechanism in this model to promote radiation resistance. Although enrichment of tumor-infiltrating neutrophils is associated with specific tumor histologies in GEMMs of lung cancer (20), neutrophil depletion did not significantly alter the characteristic spindle cell morphology of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (SI Appendix, Fig. S8E). Together, these results suggest that neutrophils promote resistance to high-dose single fraction radiation therapy through a vasculogenesis-independent mechanism.

Fig. 3.

Genetic depletion of neutrophils radiosensitizes soft tissue sarcomas. (A) Genetic strategy for sarcomagenesis with Adeno-FlpO–mediated expression of oncogenic KrasG12D and deletion of Trp53 in tumor cells and (B) depletion of neutrophils by MRP8Cre-mediated activation of diphtheria toxin expression. (C) Time from treatment to tumor volume tripling after 0 (filled circles) or 20 (open circles) Gy for mice with depleted (red) or intact (blue) neutrophils. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests for comparisons of KPM 0 Gy vs. KPM 20 Gy (P = 0.0007), KPM 0 Gy vs. KPMD 20 Gy (P < 0.0001), KPMD 0 Gy vs. KPM 20 Gy (P = 0.0031), KPMD 0 Gy vs. KPMD 20 Gy (P < 0.0001), and KPM 20 Gy vs. KPMD 20 Gy (P = 0.0039).

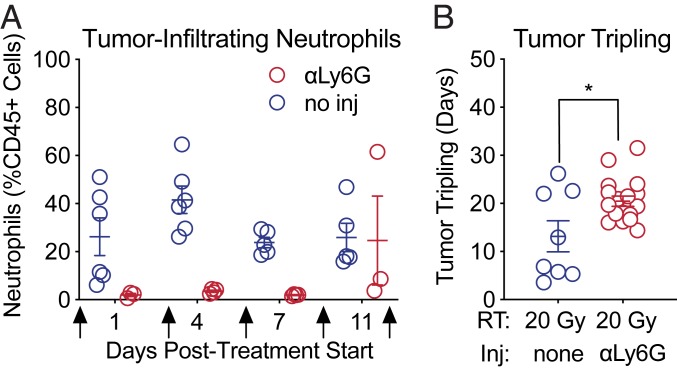

Antibody Depletion of Neutrophils Increases Radiation Sensitivity.

Although the human MRP8 promoter drives expression of Cre in the neutrophil lineage, Cre is also expressed in a small subset of myeloid precursors with monocytic potential (32). To confirm that neutrophil depletion was indeed responsible for the increased radiosensitivity of KPMD tumors, we used complementary anti–Ly6G-mediated antibody depletion to specifically deplete neutrophils. We generated sarcomas in KP mice with wild-type neutrophils. Then, mice with sarcomas measuring 70 to 150 mm3 were randomized to receive 20 Gy radiation and either anti-Ly6G antibody or no antibody. Antibody treatment was initiated 1 d before irradiation and effectively depleted tumor-infiltrating and circulating neutrophils by the time of radiation therapy 24 h later (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 A and B). Antibody treatments were administered on days 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12. Complete blood count analysis of circulating neutrophils and fine-needle aspirations of tumors at different time points after antibody treatment verified that anti-Ly6G antibody treatment depleted both circulating (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 A and B) and tumor-infiltrating neutrophils (Fig. 4A) for up to 12 d. Some mice treated with anti-Ly6G antibody experienced a rebound in neutrophil counts 11 d posttreatment despite receiving continued treatment with the anti-Ly6G antibody (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Consistent with our previous results using genetic neutrophil depletion, a single 20-Gy dose of radiation to primary sarcomas in KP mice with antibody-mediated neutrophil depletion resulted in a significantly longer tumor growth delay (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S9C) and improved survival (SI Appendix, Fig. S9D) compared to mice with intact neutrophils that were not treated with anti-Ly6G antibody.

Fig. 4.

Pharmacological depletion of neutrophils radiosensitizes soft tissue sarcomas. (A) Quantification of tumor-infiltrating neutrophils measured by flow cytometric analysis of cells serially collected from sarcomas by fine-needle aspiration at 1, 4, 7, and 11 d after treatment initiation. Mice were treated with anti-Ly6G antibody (red) or without (blue) antibody when tumor size reached 70 to 150 mm3 (day 0) and days 3, 6, 9, and 12 (arrows). (B) Time to tumor volume tripling after treatment with 20 Gy and either anti-Ly6G antibody (red) or no injection (blue). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. Two-tailed Student’s t test (P = 0.01).

Polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells arising from neutrophils (PMN-MDSC) have been shown to mediate radiation resistance in transplant tumor models by suppressing T cell activity (24). To test whether T cells have a role in radiation response of primary KP sarcomas, we used an anti-CD3 antibody to deplete T cells, beginning 1 d before radiation therapy. Antibody treatments were administered on days 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12. Depletion of circulating and tumor-infiltrating T cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A and B) did not alter the radiation sensitivity of sarcomas (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 C–E). Taken together, these results suggest that T cells do not play a critical role in the radiation response of KP sarcomas, which prompted us to investigate T cell-independent mechanisms for tumor radiosensitization by neutrophil depletion.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Decreased MAPK Activation with Neutrophil Depletion and Radiotherapy.

To further understand the impact of neutrophils on radiation resistance, we explored the sarcoma microenvironment using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). We generated sarcomas in KP mice with wild-type neutrophils. Mice with sarcomas measuring 150 to 300 mm3 were randomized to either anti-Ly6G antibody or isotype control. After 24 h, mice received either 0 or 20 Gy radiation therapy. Forty-eight hours after radiation, we harvested tumors and performed 10× scRNA-seq without cell type sorting or purification using the Chromium drop-seq platform (10× Genomics). From 2 mice per group (8 tumors total), we obtained transcriptomes from 19,056 single cells. We visualized the transcriptional profiles using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A) (36). Using Cell Ranger, we identified 16 distinct clusters, including 3 tumor cell clusters (clusters 0, 1, and 4), neutrophils (cluster 8), 4 myeloid cell clusters (clusters 3, 2, 6, and 10), T cells (cluster 7), endothelial cells (cluster 11), muscle cells (cluster 9), and other minor populations (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A and B). To visualize the distribution of cells from each group across populations, we separated the UMAP displays by treatment group (SI Appendix, Fig. S11C). We found that anti-Ly6G treatment depleted neutrophils without major effects on other myeloid cell populations (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 A and B).

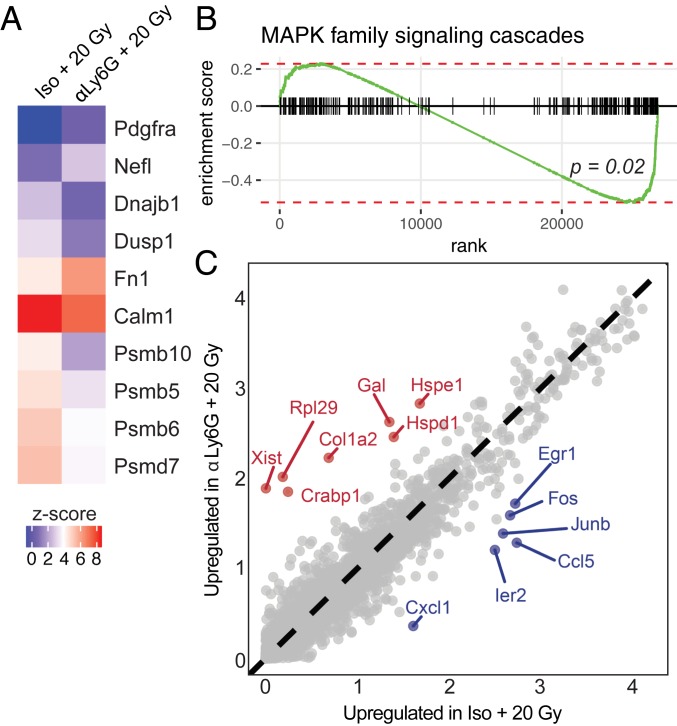

To gain insight into the mechanism by which neutrophil depletion increases radiation sensitivity, we compared tumor cells (clusters 0, 1, and 4) from mice treated with 20 Gy radiation and anti-Ly6G antibody or 20 Gy radiation and isotype control antibody (Fig. 5A). Neutrophil depletion in addition to radiation therapy down-regulated expression of the MAPK family signaling genes (Fig. 5A), which was statistically significant by gene set enrichment analysis (P = 0.02) (Fig. 5B). Differential gene expression analysis of tumor cell clusters from mice treated with 20 Gy radiation and anti-Ly6G antibody or 20 Gy radiation and isotype control antibody showed that neutrophil depletion decreased expression of immediate early genes, including Egr1, Ier2, Fos, and Junb, diminishing this oncogenic transcriptional program (Fig. 5C). These findings are consistent with a model where neutrophil depletion in KP sarcomas limits a MAPK-regulated transcriptional program downstream of oncogenic Kras. Oncogenic KrasG12D activates the MAPK pathway (37) to drive transcription of immediate early genes (38). Specifically, mutant Kras elevates expression of the AP-1 family transcription factors Fos and Jun, which then promote proliferation (39, 40). We also evaluated tumor microvessel density, vessel pericyte coverage, and hypoxia (SI Appendix, Fig. S13 A–F), but these were not altered by neutrophil depletion or radiation at this time point. Together, these results suggest a model where, after radiation therapy, tumor radiosensitization by neutrophil depletion is associated with down-regulation of oncogenic transcriptional programs.

Fig. 5.

Single-cell RNA sequencing of neutrophil-depleted and neutrophil-intact primary sarcomas with and without radiation therapy. (A) Selected gene expression for genes in MAPK family signaling cascade pathway. Gene set derived from reactome database. (B) Gene set enrichment analysis for genes in MAPK signaling family cascades pathway shows enrichment in tumor cells from isotype + 20 Gy vs. anti-Ly6G + 20 Gy (P = 0.02). (C) Expressed genes within tumor cell clusters (0, 1, and 4) for tumors treated with anti-Ly6G + 20 Gy vs. isotype + 20 Gy. Axes represent gene expression level; differentially expressed genes are highlighted in red (anti-Ly6G + 20 Gy) or blue (isotype + 20 Gy).

Discussion

In the TCGA dataset of cervical cancer patients treated with radiation therapy, we found that a neutrophil gene expression signature, indicative of high tumor-infiltrating neutrophils, was associated with worse overall survival. In an independent cohort of cervical cancer patients treated with radiation and concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy, higher peripheral ANC levels during treatment were associated with increased local cervix recurrence, higher rates of distant recurrence, and worse overall survival. To investigate the role of neutrophils in mediating radiation response, we used both genetic and pharmacologic approaches to deplete neutrophils in a primary sarcoma mouse model. In contrast to previous results with transplanted tumor models (21), we found that neutrophil depletion by either method increased tumor growth delay after RT. Taken together, these results indicate that neutrophils are important mediators of radiation resistance.

We have correlated neutrophil gene expression and neutrophil levels in the peripheral blood of human patients with an epithelial cancer and examined the role of neutrophils in a mesenchymal tumor model in mice. However, the impact of neutrophils on radiation response may depend on tumor cell-intrinsic features such as specific gene mutations or tumor histology. Indeed, when we utilized a genetically engineered mouse model of cancer driven by oncogenic KrasG12D and Trp53 mutation, we observed decreased MAPK pathway signaling with neutrophil depletion. Therefore, it is possible that the impact of neutrophils on radiation response will be greatest in tumors driven by the MAPK pathway.

KP sarcomas harbor a low mutational burden (41–43), exhibit modest immune cell infiltration (44), and express few neoantigens (42, 45). Our data suggest that neutrophils affect the radiation response through a T cell-independent mechanism in sarcomas in KP mice. However, the impact of neutrophils may be different in tumors that stimulate a strong adaptive immune response, as neutrophils are known to modulate the activity of T cells (46–48), which in turn may be important in the radiation response of immunogenic tumors (49–51).

These results have important clinical implications because they suggest that neutrophils promote radiation resistance of tumors. Furthermore, increased circulating neutrophils after the initiation of radiation treatment may serve as a biomarker of radiation resistance that can be easily determined through routine blood work. Compared to radiotherapy alone, concurrent chemoradiotherapy not only improves local control and patient survival in several cancer types (8–10), but also frequently causes a decline in neutrophil count (8, 10). Others have previously reported that a lower neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with improved overall survival after RT in rectal adenocarcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma (52–54). A recent study comparing low-dose weekly cisplatin to once-every-3-wk high-dose cisplatin chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer found that patients who received the higher dose of cisplatin had both significantly higher rates of neutropenia and significantly improved overall locoregional control (55). In a similar study in cervical cancer patients, patients were randomized to either gemcitabine and cisplatin or cisplatin alone during radiotherapy, followed by brachytherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients receiving combined gemcitabine and cisplatin had both improved survival outcomes and significantly higher rates of neutropenia (56). Conversely, others have shown that patients with neutrophilia prior to treatment have worse outcomes after radiation therapy in multiple cancer types (18). In patients with high-grade gliomas treated with concurrent temozolomide and radiation, pretreatment neutrophilia was a significant prognostic factor for poor overall survival (57).

When chemotherapy causes significant neutropenia, oncologists frequently administer granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) to stimulate neutrophil recovery (58–60). Interestingly, in a prospective trial comparing hyperfractionated radiotherapy with or without concurrent 5-FU and carboplatin chemotherapy for locally advanced oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer, patients who were randomized to receive prophylactic G-CSF on days 15 through 19 of treatment experienced significantly reduced locoregional tumor control (61). Furthermore, in mouse and human studies of cervical cancer, elevated production of G-CSF from tumor cells is associated with resistance to chemoradiotherapy and radiotherapy alone (62, 63). Taken together with our results, these findings suggest that elevating neutrophil levels during chemoradiotherapy may have the unintended consequence of increasing radiation resistance and promoting tumor recurrence.

These clinical findings and our in vivo mouse experiments suggest that suppressing neutrophil levels may be one mechanism by which concurrent chemotherapy improves tumor response to RT and patient outcomes. Moreover, our results suggest that the peripheral blood ANC, which is an inexpensive and widely available test, could be a biomarker during chemoradiotherapy for patients with cervical cancer. Finally, these findings suggest that pharmacologically targeting neutrophils, which likely would have fewer toxicities than conventional chemotherapy, may increase tumor response to radiation therapy and enhance patient outcomes. Thus, further study of the mechanisms of neutrophil-mediated radiation resistance and therapies designed to lower neutrophils during radiotherapy is warranted.

Materials and Methods

Cervical cancer patients who completed curative-intent radiation at a single academic institution (Washington University in St. Louis) from 2006 to 2017 were retrospectively reviewed with approval of the institutional review board with a waiver of consent (protocol no. 201807063). All animal studies were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhere to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (64). Additional methods can be found in SI Appendix.

Data and Materials Availability.

Single-cell RNA sequencing data are available at https://www.synapse.org (Synapse ID: syn18918968).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Dee Gunn for helpful suggestions on experimental design. The analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing used Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment Stampede2 through allocation TG-MCB180154. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the NIH under awards F30CA221268 (A.J.W.), T32GM007171 (A.J.W. and J.E.H.), K12CA167540 (S.M.), R01CA181745 (J.K.S.), and R35CA197616 (D.G.K.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: D.G.K. is a cofounder of XRAD Therapeutics, which is developing radiosensitizers.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Single-cell RNA sequencing data are available at https://www.synapse.org (Synapse ID: syn18918968).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1901562116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Moding E. J., Kastan M. B., Kirsch D. G., Strategies for optimizing the response of cancer and normal tissues to radiation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 526–542 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darby S., et al. ; Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) , Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: Meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet 378, 1707–1716 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beane J. D., et al. , Efficacy of adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma of the extremity: 20-year follow-up of a randomized prospective trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 21, 2484–2489 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larrier N. A., Czito B. G., Kirsch D. G., Radiation therapy for soft tissue sarcoma: Indications and controversies for neoadjuvant therapy, adjuvant therapy, intraoperative radiation therapy, and brachytherapy. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 25, 841–860 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta S., et al. , Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery versus concomitant chemotherapy and radiotherapy in patients with stage IB2, IIA, or IIB squamous cervical cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 1548–1555 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katakami N., et al. , A phase 3 study of induction treatment with concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus chemotherapy before surgery in patients with pathologically confirmed N2 stage IIIA nonsmall cell lung cancer (WJTOG9903). Cancer 118, 6126–6135 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pignon J. P., et al. , A meta-analysis of thoracic radiotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 327, 1618–1624 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atagi S., et al. ; Japan Clinical Oncology Group Lung Cancer Study Group , Thoracic radiotherapy with or without daily low-dose carboplatin in elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: A randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial by the Japan clinical oncology group (JCOG0301). Lancet Oncol. 13, 671–678 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chemoradiotherapy for Cervical Cancer Meta-analysis Collaboration (CCCMAC) , Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: Individual patient data meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., 10.1002/14651858.CD008285 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herskovic A., et al. , Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer of the esophagus. N. Engl. J. Med. 326, 1593–1598 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powell D. R., Huttenlocher A., Neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 37, 41–52 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen H. K., et al. , Presence of intratumoral neutrophils is an independent prognostic factor in localized renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 4709–4717 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuang D.-M., et al. , Peritumoral neutrophils link inflammatory response to disease progression by fostering angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 54, 948–955 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilie M., et al. , Predictive clinical outcome of the intratumoral CD66b-positive neutrophil-to-CD8-positive T-cell ratio in patients with resectable nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 118, 1726–1737 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen T. O., et al. , Intratumoral neutrophils and plasmacytoid dendritic cells indicate poor prognosis and are associated with pSTAT3 expression in AJCC stage I/II melanoma. Cancer 118, 2476–2485 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao H.-L., et al. , Increased intratumoral neutrophil in colorectal carcinomas correlates closely with malignant phenotype and predicts patients’ adverse prognosis. PLoS One 7, e30806 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gentles A. J., et al. , The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat. Med. 21, 938–945 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schernberg A., Blanchard P., Chargari C., Deutsch E., Neutrophils, a candidate biomarker and target for radiation therapy? Acta Oncol. 56, 1522–1530 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu P., et al. , Radiosensitivity nomogram based on circulating neutrophils in thoracic cancer. Future Oncol. 15, 727–737 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mollaoglu G., et al. , The lineage-defining transcription factors SOX2 and NKX2-1 determine lung cancer cell fate and shape the tumor immune microenvironment. Immunity 49, 764–779.e9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeshima T., et al. , Key role for neutrophils in radiation-induced antitumor immune responses: Potentiation with G-CSF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 11300–11305 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houghton A. M., The paradox of tumor-associated neutrophils: Fueling tumor growth with cytotoxic substances. Cell Cycle 9, 1732–1737 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piccard H., Muschel R. J., Opdenakker G., On the dual roles and polarized phenotypes of neutrophils in tumor development and progression. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 82, 296–309 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang H., et al. , Host STING-dependent MDSC mobilization drives extrinsic radiation resistance. Nat. Commun. 8, 1736 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel S., et al. , Unique pattern of neutrophil migration and function during tumor progression. Nat. Immunol. 19, 1236–1247 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirsch D. G., et al. , A spatially and temporally restricted mouse model of soft tissue sarcoma. Nat. Med. 13, 992–997 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman A. M., et al. , Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 12, 453–457 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coffelt S. B., Wellenstein M. D., de Visser K. E., Neutrophils in cancer: Neutral no more. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 431–446 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moding E. J., et al. , Tumor cells, but not endothelial cells, mediate eradication of primary sarcomas by stereotactic body radiation therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 278ra34 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee C.-L., et al. , Generation of primary tumors with Flp recombinase in FRT-flanked p53 mice. Dis. Model. Mech. 5, 397–402 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moding E. J., et al. , Atm deletion with dual recombinase technology preferentially radiosensitizes tumor endothelium. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 3325–3338 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Passegué E., Wagner E. F., Weissman I. L., JunB deficiency leads to a myeloproliferative disorder arising from hematopoietic stem cells. Cell 119, 431–443 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madisen L., et al. , A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ivanova A., et al. , In vivo genetic ablation by Cre-mediated expression of diphtheria toxin fragment A. Genesis 43, 129–135 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kioi M., et al. , Inhibition of vasculogenesis, but not angiogenesis, prevents the recurrence of glioblastoma after irradiation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 694–705 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McInnes L., Healy J., Melville J., UMAP: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1802.03426.pdf (9 February 2018).

- 37.Pylayeva-Gupta Y., Grabocka E., Bar-Sagi D., RAS oncogenes: Weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 761–774 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mechta F., Lallemand D., Pfarr C. M., Yaniv M., Transformation by ras modifies AP1 composition and activity. Oncogene 14, 837–847 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karin M., The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16483–16486 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shao D. D., et al. , KRAS and YAP1 converge to regulate EMT and tumor survival. Cell 158, 171–184 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang J., et al. , Generation and comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 and Cre-mediated genetically engineered mouse models of sarcoma. Nat. Commun. 8, 15999 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McFadden D. G., et al. , Mutational landscape of EGFR-, MYC-, and Kras-driven genetically engineered mouse models of lung adenocarcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E6409–E6417 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee C.-L., et al. , Mutational landscape in genetically engineered, carcinogen-induced, and radiation-induced mouse sarcoma. JCI Insight 4, 128698 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DuPage M., et al. , Endogenous T cell responses to antigens expressed in lung adenocarcinomas delay malignant tumor progression. Cancer Cell 19, 72–85 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans R. A., et al. , Lack of immunoediting in murine pancreatic cancer reversed with neoantigen. JCI Insight 1, 88328 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fridlender Z. G., et al. , Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell 16, 183–194 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eruslanov E. B., et al. , Tumor-associated neutrophils stimulate T cell responses in early-stage human lung cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 5466–5480 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rotondo R., et al. , IL-8 induces exocytosis of arginase 1 by neutrophil polymorphonuclears in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer 125, 887–893 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee Y., et al. , Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: Changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood 114, 589–595 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Twyman-Saint Victor C., et al. , Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature 520, 373–377 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsumura S., et al. , Radiation-induced CXCL16 release by breast cancer cells attracts effector T cells. J. Immunol. 181, 3099–3107 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Son S. H., Park E. Y., Park H. H., Kay C. S., Jang H. S., Pre-radiotherapy neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as an independent prognostic factor in patients with locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with radiotherapy. Oncotarget 8, 16964–16971 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vallard A., et al. , Outcomes prediction in pre-operative radiotherapy locally advanced rectal cancer: Leucocyte assessment as immune biomarker. Oncotarget 9, 22368–22382 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cho Y., et al. , The prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. J. Clin. Med. 7, E512 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Noronha V., et al. , Once-a-week versus once-every-3-weeks cisplatin chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: A phase III randomized noninferiority trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 1064–1072 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dueñas-González A., et al. , Phase III, open-label, randomized study comparing concurrent gemcitabine plus cisplatin and radiation followed by adjuvant gemcitabine and cisplatin versus concurrent cisplatin and radiation in patients with stage IIB to IVA carcinoma of the cervix. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 1678–1685 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schernberg A., et al. , Neutrophilia as a biomarker for overall survival in newly diagnosed high-grade glioma patients undergoing chemoradiation. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 10, 47–52 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith T. J., et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology , Recommendations for the use of WBC growth factors: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 3199–3212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freifeld A. G., et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America , Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52, e56–e93 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klastersky J., et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee , Management of febrile neutropaenia: ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 27 (suppl. 5), v111–v118 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Staar S., et al. , Intensified hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy limits the additional benefit of simultaneous chemotherapy - Results of a multicentric randomized German trial in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 50, 1161–1171 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mabuchi S., et al. , Uterine cervical cancer displaying tumor-related leukocytosis: A distinct clinical entity with radioresistant feature. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106, dju147 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kawano M., et al. , The significance of G-CSF expression and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the chemoresistance of uterine cervical cancer. Sci. Rep. 5, 18217 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.National Research Council , Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academies Press, Washington, DC, ed. 8, 2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.