Abstract

Survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) due to pulseless electrical activity (PEA)/asystole remains poor. We aimed to evaluate whether electrocardiographic changes provide predictive information for risk of IHCA from PEA/asystole. We conducted a retrospective case-control study, utilizing continuous electrocardiographic data from case and control patients. We selected three consecutive 3-hour blocks (block 3, 2, 1 in that order); block 1 immediately preceded cardiac arrest in cases, whereas block 1 was chosen at random in controls. In each block, we measured dominant positive and negative trends in electrocardiographic parameters, evaluated for arrhythmias, and compared these between consecutive blocks. We created random forest and logistic regression models, and tested them on differentiating case vs. control patients (case block 1 vs. control block 1), and temporal relationship to cardiac arrest (case block 2 vs. case block 1). Ninety-one cases (age 63.0±17.6, 58% male) and 1783 control patients (age 63.5±14.8, 67% male) were evaluated. We found significant differences in electrocardiographic trends between case and control block 1, particularly in QRS duration, QTc, RR, and ST. New episodes of atrial fibrillation and bradyarrhythmias were more common before IHCA. The optimal model was the random forest, achieving an AUC of 0.829, 63.2% sensitivity, 94.6% specificity at differentiating case vs. control block 1 on a validation set, and AUC 0.954, 91.2% sensitivity, 83.5% specificity at differentiating case block 1 vs. case block 2. In conclusion, trends in electrocardiographic parameters during the 3-hour window immediately preceding in-hospital cardiac arrest differ significantly from other time periods, and provide robust predictive information.

Keywords: in-hospital cardiac arrest, electrocardiogram, telemetry, machine learning

Background

In-hospital cardiac arrests (IHCA) remain a major health care problem, affecting over 250,000 patients in the United States annually, with fewer than 30% surviving to discharge. Over the past decade, there has been considerable interest in early intervention, but significant limitations remain in identifying at-risk patients where early intervention may be beneficial1–4. Electrocardiographic (ECG)/telemetry data is continuously acquired for many hospitalized patients and reflects various physiologic changes due to stressors. Many intra-patient ECG changes including PR and QRS prolongation, ST changes, and bradyarrhythmias are seen in the 24 hours and particularly the one hour period before IHCA5–7. However, it remains unknown whether these findings are predictive of IHCA. In this study, we evaluate whether the measurement of trends in ECG parameters, particularly in comparison to a patient’s baseline physiologic variations and detection of new arrhythmias, provides predictive information for IHCA from pulseless electrical activity (PEA) or asystole.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective case-control study at the University of California, Los Angeles Ronald Reagan Medical Center, a 520-bed tertiary care hospital. Telemetry data was obtained by General Electric (GE) monitoring systems (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI), and pooled on a remote data server via Bedmaster (Excel Medical Electronics, Jupiter, FL). Signals were sampled at 240 Hz with 12-bit representation. Continuous electrocardiographic data was obtained using a standard 5 electrode configuration providing 6 ECG limb leads and a precordial lead usually in the VI/V2 position. A total of 200 beds, including all 130 adult intensive care unit (ICU) beds, and 70 medical-surgical unit beds were monitored with the Bedmaster system. This study received approval from the institutional review board.

We evaluated all ‘code blues’ (hospital calls for emergency resuscitation team) between April 2010 and August 2014, and included IHCA cases due to PEA or asystole in patients age ≥18 years with at least 6 consecutive hours of telemetry data prior to and including the onset of IHCA. We excluded cases where cardiac arrest (defined as lack of central pulse, apnea, and unresponsiveness) did not occur, patients with a do-not-resuscitate order, primarily ventricular-paced rhythm, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest leading to current admission, IHCA in a procedural unit or operating room, and IHCA within the first 24 hours of a trauma admission. Only the first IHCA in any patient was included. The time of IHCA was determined by review of ECG data and marked at onset of asystole or initiation of chest compressions in cases of PEA.

Control patients were selected at random from the same units where ‘code blue’ patients (not specifically patients who met all inclusion/exclusion criteria) were located and temporally spread across the study period. Criteria for selecting control patients included survival to discharge, no unplanned ICU transfers or ‘code blues’ during the admission. Case patients who had another admission which met those criteria were excluded as controls. For each control patient, we extracted the first 24 hours of telemetry data available, since this was likely to be the period of greatest instability.

Telemetry data was processed using a research ECG analysis program written by coauthor DM to obtain: 1) a minute-by-minute time series of ECG parameters (PR interval, QRS duration, QRS amplitude averaged over the 4 leads, ST segment height in lead II and V2, QTc measured using the tangent method, and RR) derived from a 5-minute signal-averaged beat obtained in a rolling window fashion, and 2) a time series of all consecutive RR intervals (Supplemental Figure 1).

The averaged beat-derived time series was processed with filters to reduce noise and remove non-physiologic data. The RR time series, following removal of data points affected by excessive signal artifact, was processed to identify periods of atrial fibrillation, second degree heart block (2° HB), and pauses greater than 3 seconds, using modifications of methods described by Lian et al8 and Tsipouras et al9 (see Supplemental Methods for details).

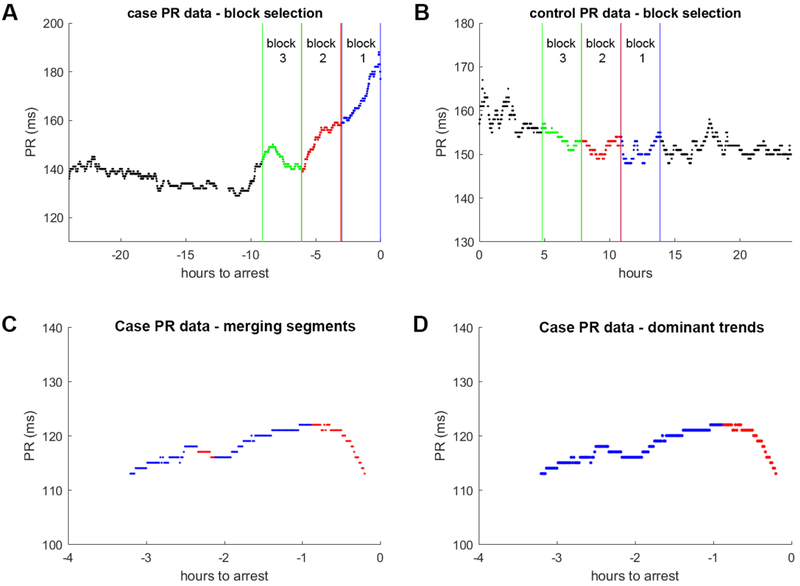

Three consecutive 3-hour blocks (blocks 3, 2, 1 in that order) were selected for further analysis: in case patients, block 1 immediately preceded IHCA whereas in control patients block 1 was selected at random. Blocks 3 and 2 were then selected as the two 3-hour blocks that immediately preceded block 1 in either case or control patients (Figure 1 A).

Figure 1: Block selection and dominant trend determination example.

Three consecutive 3-hour blocks are selected in both case and control patients. For cases, the blocks immediately precede in-hospital cardiac arrest (Panel A). In controls, the blocks are randomly selected (Panel B). Only block 1 in cases is associated with IHCA. Next, dominant positive and negative trends are determined for each ECG parameter in each of the blocks. Panel C and D shows an example of this process in block 1 of a case patient (different patient from Panel A). The direction of change at each point is first calculated by robust linear fitting (Panel C). Blue denotes increasing average values at the point (positive trends) and red denotes decreasing average values (negative trends). Next short segments flanked by longer segments with opposite directionality are merged with the more dominant trend to remove minor fluctuations. Panel D shows the resultant dominant trends after a short negative trend segment is merged with the longer positive trend segment. The dominant trend in either direction is then determined by the trend in that direction with the longest duration.

For the averaged beat data, in each block of data, we determined the dominant positive and negative trend for each ECG parameter (Figure 1B, see Supplemental Methods for details). All time series processing was performed using Matlab 2017b (Mathworks, Natick, MA).

The following features, all continuous variables, were calculated from the averaged beat data for each ECG parameter in each block:

Change in dominant positive and negative trends in block n (Δyn+, Δyn−), calculated by subtracting the maximal and minimal value for the trend.

Slope of the dominant positive and negative trends (Δyn+/Δxn+, Δyn−/Δxn−), calculated by dividing the change over the duration.

Difference in dominant positive and negative trend change and slope between a patient’s block n and immediately preceding block (n-1). Four values were calculated: difference in dominant: 1) positive change (Δyn-(n-1)+); 2) negative change (Δyn-(n-1)−); 3) positive slope (Δyn+/Δxn+ – Δy(n-1)+/Δx(n-1)+); and 4) negative slope (Δyn−/Δxn – Δy(n-1)−/Δx(n-1)−).

Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilks test. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for within-group comparisons and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for between-group comparisons given non-normality of many variables. For the presence of atrial fibrillation, 2° HB, and pauses, we calculated an indicator variable for the presence of those arrhythmias in block n, and a second for the presence of those arrhythmias in block n but not block (n-1).

Next, we divided the case and control block 1 into an 80% model development and 20% validation set, by stratified random sampling based on case/control status. Using the development set, we performed univariate logistic regression analyses, and retained any variable with p<0.05 for use in multivariable model development. Missing values were imputed using multiple imputations. We created 3 models: logistic regression with backward stepwise regression, forward stepwise regression, and random forest with 10,000 trees.

We evaluated each model on the validation set by using the area under the curve (AUC) and sensitivity for classifying a block as IHCA while maintaining a low false positive rate (FPR). We performed further testing of model robustness by setting a classification threshold where FPR on the validation set was approximately 5% and evaluated the sensitivity and specificity on case block 1 vs. case block 2 (temporal differentiation of IHCA detection), validation case block 1 vs. all control block 2, all case block 2 vs. validation control block 1, all case block 2 vs. all control block 2.

A two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. For univariate analyses, adjustment for multiple hypothesis testing was evaluated by calculating q-values to estimate the false discovery rate with q<0.05 considered significant10. Statistical analysis was performed using R v3.4.4 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) with packages pROC, RandomForest, qvalue 11–13.

Results

During the study period, 536 “code blues” occurred for IHCA on a ward or ICU bed in 449 unique patients; of these, 91 cases (mean age 63.0±17.6, 58% male) were PEA/Asystole arrests meeting all inclusion/exclusion criteria. The predominant reasons for exclusion were the lack of sufficient continuous ECG data available for analysis (225/358, 63%), ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation arrest (45/358, 13%) and loss of ECG data at the onset of cardiac arrest (27/358, 8%). Asystole was the arrest rhythm in 16 (18%) patients. The primary clinical causes of IHCA were respiratory in 44 (48%), multiorgan failure in 14 (15%), and metabolic acidosis in 13 (14%). Eighty-one (89%) IHCA cases occurred in the ICU, 65 (71%) had return of spontaneous circulation, and 26 (29%) survived to discharge (Table 1). We identified 6100 controls of which 1783 patients (mean age 63.5±14.8, 67% male) had continuous ECG data available for analysis.

Table 1:

Demographics

| Variable | Case (n = 91) | Control (n = 1783) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.0±17.6 | 63.5±14.8 |

| Male | 53 (58%) | 1201 (67%) |

| ICU | 81 (89%) | 1322 (75%) |

| Arrest characteristics | ||

| Asystolea (bpm) | 16 (18%) | |

| Preceding HR ≤ 29 | 8 (50%) | |

| Preceding HR 30-49 | 1 (6%) | |

| Preceding HR 50-69 | 6 (38%) | |

| Preceding HR ≥ 70 | 1 (6%) | |

| PEA (bpm) | 75 (82%) | |

| Preceding HR ≤ 29 | 13 (17%) | |

| Preceding HR 30-49 | 24 (32%) | |

| Preceding HR 50-69 | 22 (29%) | |

| Preceding HR 70-89 | 9 (12%) | |

| Preceding HR ≥ 90 | 7 (9%) | |

| ROSC | 65 (71%) | |

| Survival to discharge | 26 (29%) | |

| Cardiac arrest cause | ||

| Respiratory – unintubated | 30 (33%) | |

| Respiratory - intubated | 14 (15%) | |

| Metabolic acidosis | 13 (14%) | |

| Hemorrhagic shock | 3 (3%) | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 6 (7%) | |

| Distributive shock | 1 (1%) | |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (2%) | |

| Multiorgan failure | 14 (15%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (9%) | |

Asystole due to sinus arrest or complete AV block with no escape rhythm

Abbreviations. ICU: intensive care unit, HR: heart rate, bpm: beats per minute, PEA: pulseless electrical activity, ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation

After adjusting for multiple hypothesis testing, we found 41/62 variables that differed significantly between case block 1 and control block 1, particularly those related to QRSd, QTc, RR, ST lead II and V2; 18/62 variables differed significantly between case blocks 2 and 1 (Table 2). For these ECG parameters, increased change in both positive and negative directions were associated with IHCA.

Table 2:

Electrocardiographic parameter summary

| Variable | Case Block 1 (n = 91) | Control Block 1 (n = 1783) | p-value c | Case block 1 (n = 85 d) | Case block 2 (n = 85 d) | p-value e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmias, n(%) | ||||||

| AF, any in block n | 31 (34%) | 373 (20%) | 0.0029 | 30 (35%) | 17 (24%) | 0.0258 |

| AF, present block n not block n-1 | 13 (14%) | 64 (3%) | <0.0001 | 13 (15%) | 3 (4%) | 0.0086§ |

| 2° HB, any in block n | 36 (40%) | 332 (18%) | <0.0001 | 33 (39%) | 7 (10%) | <0.0001f |

| 2° HB, present block n not block n-1 | 26 (29%) | 162 (3%) | <0.0001 | 26 (31%) | 3 (4%) | <0.0001f |

| Pauses, any in block n | 30 (33%) | 376 (20%) | 0.0073 | 30 (35%) | 8 (12%) | <0.0001f |

| Pauses, present block n not block n-1 | 22 (24%) | 229 (12%) | 0.0020 | 22 (26%) | 5 (7%) | 0.0004§ |

| Trend Slope (Δyn/Δxn)b, median (IQR) | ||||||

| QRS Amplitude Averaged + (μV/hr) | 321 (119 – 641) | 312 (138 – 627) | NS | 305 (119 – 623) | 223 (118 – 447) | NS |

| QRS Amplitude Averaged + (μV/hr) | 310 (125 – 613) | 285 (137 – 608) | NS | 243 (122 – 608) | 210 (97 – 499) | NS |

| PR Interval + (ms/hr)a | 8.0 (4.5 – 14.1) | 6.7 (3.6 – 12.6) | NS | 5.9 (3.7 – 9.3) | 8.0 (3.9 – 16.2) | NS |

| PR Interval − (ms/hr)a | 9.5 (4.3 – 20.0) | 6.7 (3.7 – 13.4) | 0.0466 | 6.5 (3.5 – 20.5) | 7.6 (3.6 – 13.0) | NS |

| QRS Duration + (ms/hr) | 6.5 (2.8 – 13.6) | 4.2 (1.8 – 8.6) | 0.0020 | 8.1 (3.3 – 14.1) | 3.6 (1.9 – 7.8) | 0.0488 |

| QRS Duration − (ms/hr) | 5.5 (3.0 – 13.2) | 3.7 (1.6 – 8.1) | 0.0011 | 5.3 (3.0 – 13.3) | 4.2 (1.9 – 8.1) | 0.0019f |

| QTc + (ms/hr) | 16.9 (8.3 – 37.3) | 13.9 (7.6 – 27.5) | NS | 16.7 (8.8 – 32.2) | 13.5 (7.4 – 25.6) | NS |

| QTc − (ms/hr) | 16.4 (9.5 – 53.3) | 13.3 (6.9 – 25.5) | 0.0086 | 15.6 (8.8 – 54.4) | 12.7 (7.2 – 36.5) | NS |

| RR + (ms/hr) | 48.8 (26.5 – 76.1) | 52.8 (27.2 – 98.2) | NS | 40.8 (26.4 – 75.9) | 40.6 (19.0 – 69.5) | NS |

| RR − (ms/hr) | 45.1 (23.2 – 96.4) | 53.8 (25.6 – 112.9) | NS | 42.0 (18.5 – 90.4) | 32.9 (15.9 – 65.6) | NS |

| ST Lead II + (μV/hr) | 28.6 (13.1 – 67.1) | 15.0 (7.8 – 29.0) | <0.0001 | 29.1 (12.9 – 66.4) | 20.1 (8.6 – 37.9) | 0.0020f |

| ST Lead II − (μV/hr) | 28.5 (14.0 – 48) | 15.0 (8.0 – 30.4) | <0.0001 | 27.0 (14.0 – 47) | 20.5 (8.3 – 35.5) | NS |

| ST Lead V2 + (μV/hr) | 16.0 (6.2 – 33.5) | 10.5 (5.5 – 19.5) | 0.0009 | 16.5 (5.4 – 34.6) | 12.6 (6.5 – 26.2) | NS |

| ST Lead V2 − (μV/hr) | 15.8 (6.5 – 33.0) | 10.5 (5.3 – 20.7) | 0.0060 | 16.3 (6.6 – 33.0) | 11.7 (6.4 – 22.8) | NS |

| Trend Slope Comparison (Δyn/Δxn – Δyn-1/Δxn-1) b, median (IQR) | ||||||

| QRS Amplitude Averaged + (μV/hr) | 43 (−148 – 278) | 10 (−212 – 243) | NS | 69 (−131 – 277) | 13 (−155 – 157) | NS |

| QRS Amplitude Averaged − (μV/hr) | 45 (−108 – 238) | −4 (−187 – 203) | NS | 43 (−171 – 301) | 23 (−162 – 159) | NS |

| PR Interval + (ms/hr)a | 0.0 (−2.7 – 2.8) | 0.2 (−4.8 – 5.1) | NS | 0.1 (−3.3 – 3.3) | −0.7 (−3.7 – 3.1) | NS |

| PR Interval − (ms/hr)a | 1.2 (−2.6 – 7.7) | 0.2 (−4.8 – 5.0) | 0.0210 | 0.3 (−4.2 – 7.9) | −0.15 (−4.0 – 5.2) | NS |

| QRS Duration + (ms/hr) | 0.4 (−2.6 – 7.1) | 0 (−3.7 – 3.9) | NS | 1.1 (−2.3 – 9.6) | −0.1 (−2.8 – 2.2) | NS |

| QRS Duration − (ms/hr) | 1.3 (−2.2 – 5.2) | 0.1 (−3.5 – 3.7) | 0.0072 | 2.2 (−1.1 – 6.1) | 0.4 (−2.7 – 2.7) | 0.0096f |

| QTc + (ms/hr) | 1.0 (−7.6 – 18.0) | 0.3 (−11.0 – 11.3) | NS | 1.0 (−7.7 – 18.3) | 0.1 (−8.9 – 11.4) | NS |

| QTc − (ms/hr) | −2.4 (−7.1 – 21.8) | 0.4 (−8.9 – 10.7) | NS | 0.1 (−7.7 – 23.8) | 0.2 (−9.9 – 19.8) | NS |

| RR + (ms/hr) | 3.9 (−23.4 – 29.3) | 3.3 (−31.8 – 38.3) | NS | 2.8 (−24.8 – 25.1) | 0.6 (−17.5 – 22.1) | NS |

| RR − (ms/hr) | 3.7 (−16.2 – 37.4) | 0.1 (−42.2 – 38.1) | NS | 3.3 (−15.2 – 37.7) | 0.2 (−16.2 – 17.4) | NS |

| ST Lead II + (μV/hr) | 6.3 (−5.4 – 32.3) | −0.4 (−11.5 – 11.1) | 0.0002 | 6.3 (−5.4 – 32.3) | −1.9 (−9.5 – 18.3) | 0.0201 |

| ST Lead II − (μV/hr) | 4.2 (−6.8 – 26.1) | −0.2 (−11.7 – 11.1) | 0.0029 | 4.5 (−8.7 – 26.1) | 2.0 (−10.7 – 12.8) | NS |

| ST Lead V2 + (μV/hr) | 2.4 (−8.7 – 10.6) | −0.1 (−7.9 – 7.7) | NS | 2.6 (−8.7 – 13.3) | 0.8 (−6.5 – 12.7) | NS |

| ST Lead V2 − (μV/hr) | 1.5 (−6.8 – 12.8) | 0.0 (−8.2 – 7.0) | NS | 1.5 (−6.8 – 12.8) | 2.3 (−5.2 – 11.1) | NS |

| Trend Change (Δyn) b, median (IQR) | ||||||

| QRS Amplitude Averaged + (μV) | 113 (54 – 181) | 86 (47 – 158) | NS | 102 (54 – 181) | 72 (41 – 141) | 0.0224 |

| QRS Amplitude Averaged − (μV) | 109 (65 – 165) | 85 (48 – 143) | 0.0462 | 98 (48 – 190) | 75 (31 – 126) | 0.0494 |

| PR Interval + (ms) a | 10 (5 – 15.5) | 7 (4 – 14) | 0.0347 | 8 (5 – 14) | 9 (5 – 15) | NS |

| PR Interval − (ms) a | 12 (5 – 17) | 7 (4 – 14) | 0.0270 | 8 (4 – 18) | 9 (4 – 12.5) | NS |

| QRS Duration + (ms) | 9 (4 – 16) | 4 (2 – 8) | <0.0001 | 11 (4 – 16) | 5 (2 – 12) | 0.0005f |

| QRS Duration − (ms) | 7.5 (3 – 13) | 5 (2.8 – 8) | 0.0015 | 8 (3 – 13) | 5 (2 – 8) | 0.0101f |

| QTc + (ms) | 24.4 (14.6 – 43.3) | 14.6 (8.5 – 26.7) | <0.0001 | 24.1 (11.9 – 44.6) | 16.8 (8.4 – 31.3) | 0.0035f |

| QTc − (ms) | 30.1 (11.1 – 56.9) | 14.4 (9.0 – 26.0) | <0.0001 | 30.1 (10.5 – 60.6) | 16.9 (8.4 – 34.4) | 0.0108f |

| RR + (ms) | 59 (35.5 – 134) | 61 (32 – 103) | NS | 62 (36 – 137) | 41 (18 – 70) | 0.0024f |

| RR − (ms) | 61 (28 – 120) | 58 (31 – 105) | NS | 51 (21 – 120) | 37 (22 – 71) | NS |

| ST Lead II + (μV) | 32 (15 – 70) | 16 (9 – 29.8) | <0.0001 | 34 (15 – 75) | 19 (9 – 41) | 0.0020f |

| ST Lead II − (μV) | 30 (14 – 66.5) | 16 (9 – 29) | <0.0001 | 30 (14 – 64.5) | 20 (12 – 45) | 0.0037f |

| ST Lead V2 + (μV) | 16 (8-33) | 11 (6 – 20) | 0.0003 | 18 (8 – 37) | 12 (6 – 20) | 0.0311 |

| ST Lead V2 − (μV) | 20 (9 – 41) | 11 (6 – 20) | <0.0001 | 20 (9 – 41) | 12 (6 – 22) | 0.0002f |

| Trend Change Comparison (Δyn-(n-1))b, median (IQR) | ||||||

| QRS Amplitude Averaged + (μV) | 21 (−29 – 77) | 0 (−59 – 61) | 0.0306 | 28 (−24 – 93) | −3 (−42 – 55) | NS |

| QRS Amplitude Averaged − (μV) | 10 (−22 – 104) | 0 (−42 – 49) | 0.0239 | 8 (−34 – 114) | 10 (−46 – 38) | NS |

| PR Interval + (ms)a | 0 (−3 – 3) | 0 (−5 – 4) | NS | −1 (−5.5 – 3.5) | 0 (−5 – 4) | NS |

| PR Interval − (ms)a | 1 (−1.5 – 4.5) | 0 (−4 – 4) | NS | 2 (−3.5 – 9.5) | 0 (−3 – 3) | NS |

| QRS Duration + (ms) | 1 (−1 – 6) | 0 (−3 – 3) | 0.0004 | 2 (−2 – 11) | 0 (−4 – 3) | NS |

| QRS Duration – (ms) | 1 (−1 – 5.75) | 0 (−3 – 3) | 0.0069 | 2 (−1 – 8) | −1 (−4.5 – 3) | 0.0211 |

| QTc + (ms) | 6 (−6 – 22) | 0.7 (−8.3 – 9.3) | 0.0365 | 6 (−6 – 24) | 0.8 (−9.4 – 12.9) | NS |

| QTc − (ms) | 7 (−5 – 25) | −0.20 (−8.5 – 8.2) | 0.0002 | 7 (−6 – 36) | −1.0 (−5.9 – 12.2) | NS |

| RR + (ms) | 21 (−19.5 – 55) | 1 (−33 – 37) | 0.0010 | 23 (−18 – 57) | −8 (−25 – 23) | 0.0019f |

| RR − (ms) | 12 (−16 – 54) | 2 (−31 – 35.5) | 0.0220 | 9 (−21 – 60.5) | −4 (−24 – 15) | 0.0451 |

| ST Lead II + (μV) | 7 (−7 – 35.5) | 0 (−10 – 10) | 0.0006 | 9 (−7.5 – 42) | 0 (−9 – 13) | NS |

| ST Lead II − (μV) | 9 (−6 – 30.5) | 0 (−10 – 10) | <0.0001 | 9 (−7 – 26) | 4 (−6 – 12) | NS |

| ST Lead V2 + (μV) | 2 (−4.5 – 10.5) | 0 (−7 – 6) | 0.0419 | 4 (−4 – 18.3) | 0 (−8 – 7) | NS |

| ST Lead V2 − (μV) | 6 (−2 – 25.5) | 0 (−6 – 7) | <0.0001 | 7.5 (−2 – 26) | 0(−6 – 10) | 0.0113f |

Abbreviations: AF – atrial fibrillation, HB – heart block, IQR – interquartile range

Reported where measureable given this is not measureable in atrial fibrillation

For each row, + denotes the measure for the dominant positive trend, and − denotes the measure for the dominant negative trend for that ECG parameter. All negative trend change and slope measurements are reported as the absolute value.

All univariate comparisons with p-value < 0.05 were also significant at q-value < 0.05, which corrects for false discovery rate due to multiple hypothesis testing

This reflects the number of patients who had a block 3 available, as this was required to calculate trend slope and trend change comparison values

All trend comparisons were performed using paired comparison with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test

These values were significant at the q-value < 0.05 level, which corrects for the false discovery rate due to multiple hypothesis testing

Atrial fibrillation, 2° HB, or pauses were more commonly observed in case block 1 than control block 1 (Table 2). Case patients with new onset atrial fibrillation, 2° HB, and pauses in block 1 but not block 2 had median onset 36 (IQR 10-102), 8(IQR2-21), 18(IQR6-85) minutes, respectively, prior to IHCA.

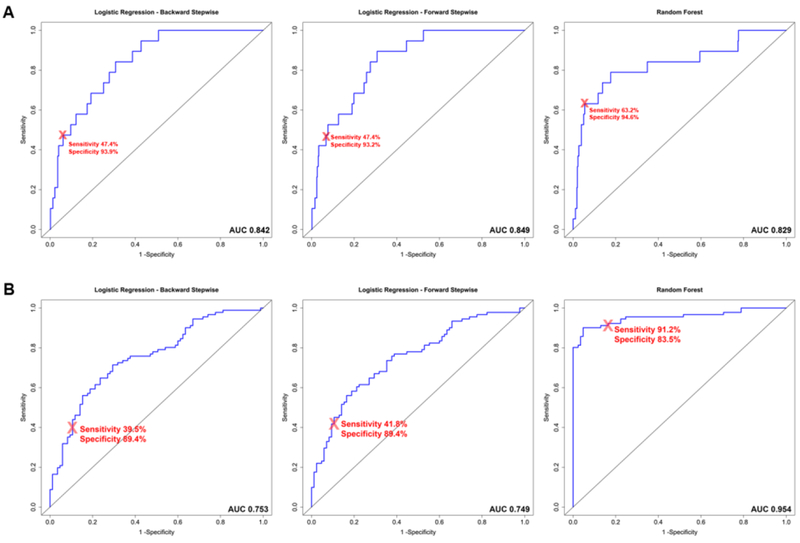

Both logistic regression models achieved similar AUC on the development set (0.769 vs 0.774) and validation set (0.842 vs 0.849) (Table 3, Figure 2). In both models, the presence of atrial fibrillation and 2° HB in block n but not block n-1, QRSd Δyn+, QRSd Δyn+/Δxn+, QTc Δyn−, RR Δyn-(n-1)+, and ST Lead V2 Δyn-(n-1)− were significantly associated with the risk of IHCA (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 3:

Multivariate Model Performance

| Logistic Regression – Backward Stepwise | Logistic Regression – Forward Stepwise | Random Forest | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Set (Case block 1 vs. Control block 1) | |||

| AUC | 0.769 | 0.774 | 0.738 |

| Validation Set (Case block 1 vs. Control block 1) | |||

| AUC | 0.842 | 0.849 | 0.829 |

| Sensitivity, FPR 2.5% | 21.1% | 15.8% | 36.8% |

| Sensitivity, FPR 5.0% | 42.1% | 42.1% | 57.9% |

| Sensitivity, FPR 10.0% | 52.6% | 52.6% | 63.2% |

| Validation Set Performance at Selected Thresholda | |||

| Sensitivity | 47.4% | 47.4% | 63.2% |

| Specificity | 93.9% | 93.2 % | 94.6% |

| Testb – All Case Block 1 vs. Case Block 2 | |||

| AUC | 0.753 | 0.749 | 0.954 |

| Sensitivity | 39.5% | 41.8% | 91.2% |

| Specificity | 89.4% | 89.4% | 83.5% |

| Testb – Validation Set Case Block 1 vs. Control Block 2 | |||

| AUC | 0.849 | 0.852 | 0.840 |

| Sensitivity | 42.1% | 47.3% | 63.2% |

| Specificity | 94.6% | 94.5% | 93.8% |

| Testb – Case Block 2 vs. Validation Set Control Block 1 | |||

| AUC | 0.524 | 0.536 | 0.584 |

| Sensitivity | 10.6% | 10.6% | 16.5% |

| Specificity | 93.9% | 93.2% | 94.6% |

| Testb – Case block 2 vs. Control block 2 | |||

| AUC | 0.532 | 0.543 | 0.600 |

| Sensitivity | 10.6% | 10.6% | 16.5% |

| Specificity | 94.6% | 94.5% | 93.8% |

Abbreviations: AUC – area under the curve, FPR – false positive rate

Threshold selected for FPR on validation set approximately 5 %

All sensitivity and specificities are reported at the selected threshold

Figure 2: Receiver Operating Characteristics Curves.

Panel A shows ROC curves for discriminating Case block 1 vs. Control block 1 in the validation set. Panel B shows ROC curves for discriminating all Case block 1 vs. Case block 2. Block 1 is the 3-hour block immediately preceding in-hospital cardiac arrest, while block 2 is the 3-hour block preceding block 1. Only Case block 1 is considered a true positive. Curves for 3 multivariable models are shown: 1. Logistic regression with backward stepwise regression, 2. Logistic regression with forward stepwise regression, 3. Random forest with 10,000 trees. The red (X) marks the sensitivity and specificity at the threshold chosen based on the validation set to achieve a specificity of approximately 95%. (AUC = area under the curve)

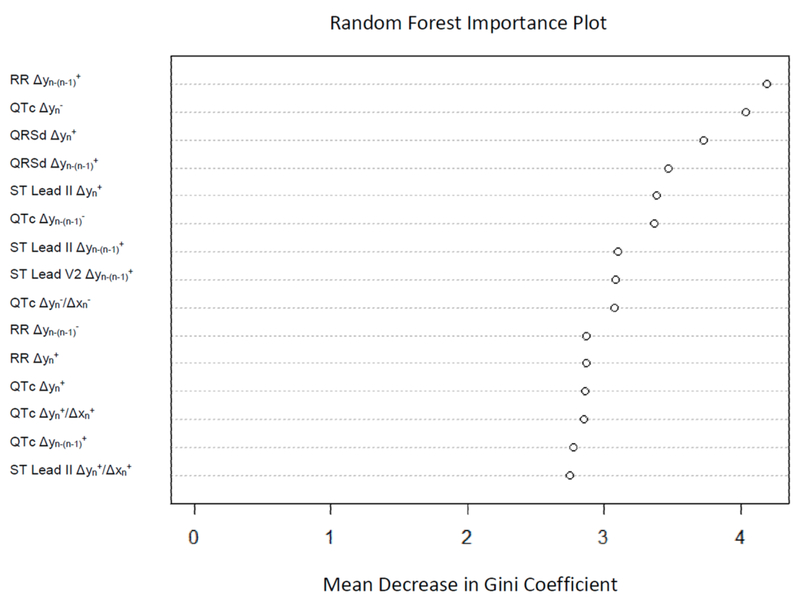

The random forest model achieved an AUC of 0.738 on the development set and 0.829 on the validation set. The 5 most important variables in this model were: RR Δyn-(n-1)+, QTc Δyn−, QRSd Δyn+, QRSd Δyn-(n-1)+, and ST Lead II Δyn+ (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Random Forest Importance Plot.

This shows the 15 variables with the highest importance in the random forest, based on mean decrease in the Gini coefficient (measure of how much each variable contributes to homogeneity of the nodes and leaves in the random forest). Higher values signify higher importance of the variable.

Evaluating the models based on sensitivity achieved with a low FPR, the random forest model performed best, achieving a sensitivity of 36.8%, 57.9%, and 63.2% with FPR of 2.5%, 5%, and 10% respectively (Table 3). Using a threshold determined by maintaining an approximately 5% FPR, the random forest model was the best at distinguishing block 1 from block 2 in cases (AUC 0.954, sensitivity 91.2%, specificity 83.5%). All models, as expected, performed poorly at differentiating case block 2 from either control block 1 or block 2 (Table 3).

Discussion

Rapid response teams and current-day practice of critical care medicine are predicated on the principle that early intervention can improve patient outcomes4. The early and accurate identification of clinically deteriorating patients at risk of IHCA is paramount for rapid response systems to be successful, but remains one of the major limitations of this approach4,14. The reliance of early warning systems on the available electronic health record data, including intermittently collected vital signs and laboratory results, limits the capability to detect rapid deterioration15,16. Continuous ECG data can overcome these limitations by providing constant information on the patient’s physiological state, particularly in those without invasive monitors.

In this study, we show that: 1) it is feasible to trend changes in clinically relevant ECG parameters and arrhythmias using continuous ECG, 2) trends in ECG parameters and arrhythmias differ significantly in the 3-hour window pre-IHCA, and 3) this can be leveraged in predictive models for IHCA due to PEA/asystole. This is the first study to evaluate the use of continuous ECG to predict IHCA from PEA/asystole, which make up around 80% of IHCA17.

The current use of continuous ECG monitoring is limited by its reliance on threshold-based changes to trigger alarms without consideration for patients’ baseline physiology and variations over time, leading to innumerable nonactionable alarms18. Using trends in ECG parameters on continuous recordings individualizes clinical risk prediction, reflecting a clinician’s assessment7,19. For example, 0.1mV ST depression in a patient with baseline left ventricular hypertrophy and repolarization abnormalities confers a significantly lower risk compared to a patient with normal baseline ST segment who develops new 0.1mV ST depression. While some physiologic fluctuations in ECG parameters are expected even in resting normal healthy subjects20,21, the degree of fluctuations prior to IHCA exceed those normally observed.

Evaluating trends in both positive and negative directions allow for detection of different types of physiologic disturbances associated with different causes of cardiac arrest (Supplemental Figure 3). For example, QRS prolongation by intraventricular conduction delay reflects progressive ischemia22, while decreases in measured QRS duration is likely a result of decreasing QRS amplitude23, reported in septic shock states24. Comparing trends and arrhythmias across time further individualizes risk prediction. Some ECG parameters, such as RR and ST, can fluctuate significantly even in healthy states. Hence, physiologic versus pathologic changes (eg. slowing heart rate preceding many PEAs25‘26), can be better differentiated by comparing to earlier time periods when the patient was stable (Supplemental Figure 4).

In this study, we show that ECG changes in a 3-hour window can provide predictive information for imminent IHCA, independent of other patient data. Since relatively few patients suffer IHCA, models with low false positive rate for similar sensitivity are preferred. Using this criterion, the random forest model performed best, attaining 63.2% sensitivity with 94.6% specificity at the selected threshold. The random forest model also showed excellent temporal discriminatory ability with a 91.2% sensitivity and 83.5% specificity at distinguishing case block 1 vs. block 2. While logistic regression has been the standard risk prediction model, it assumes that risk factors (ie. ECG metrics in our study) are additive27. Conversely, non-linear classifiers such as the random forest model perform better with classification problems where different factors may be highly correlated12, at the cost of becoming a “black box”.

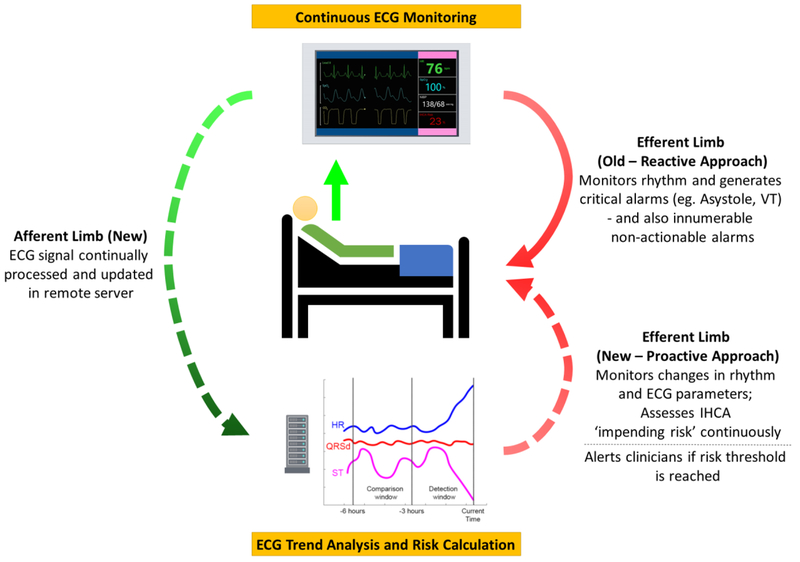

Our study provides proof of concept for utilizing trends in ECG metrics to predict IHCA. This study does not, however, provide an estimate of the lead time by which IHCA can be detected with ECG metrics; this will be the focus of our future work. In this approach, ECG metrics can be used predictively in conjunction with other data streams in a Bayesian manner28,29. Whereas intermittently collected data such as vital signs and laboratory data can predict the “at-risk” patient, real-time ECG changes can help pinpoint the patient at “impending risk” of IHCA or who is rapidly deteriorating clinically. Feedback to clinicians can be provided with an IHCA “impending risk” score, updated in real-time (Figure 4), allowing for earlier detection of patient deterioration, earlier clinical intervention, and potentially improved patient outcomes.

Figure 4: Optimal Continuous ECG Risk Prediction Model.

that provides a closed feedback loop, is updated continuously, and leverages the dynamic nature of ECG to provide personalized risk prediction. (IHCA: in-hospital cardiac arrest; VT: ventricular tachycardia)

Several limitations to this study should be acknowledged. First, the number of IHCA cases used in model derivation was small and predominantly from ICU patients, potentially limiting generalizability. Nonetheless, IHCA due to respiratory failure in non-intubated patients, the most common cause of PEA/Asystole in a general hospital population, did make up the largest group of cases in our study30. Secondly, due to the small number of cases, we could not use an independent test set for validation which can lead to overestimation of our model’s predictive power. However, further testing using case block 2 data showed performance that was as expected.

In conclusion, trends in ECG parameters, particularly in QRS duration, QTc, ST, and RR, differed significantly in a 3-hour window immediately preceding IHCA from PEA/Asystole when compared to other 3-hour windows in both case and control patients. New episodes of atrial fibrillation and second degree heart block were more common prior to IHCA. Using continuous ECG changes alone in a real-world dataset, a random forest model achieved an AUC 0.829, 63.2% sensitivity and 94.6% specificity at differentiating case vs. controls in an independent validation set, and AUC 0.954, 91.2% sensitivity and 83.5% specificity at distinguishing between the final 3-hour block preceding IHCA from the prior 3-hour block. This study supports the feasibility of utilizing trends in continuous ECG data in predictive models for IHCA. Effective utilization of the real-time physiologic data afforded by continuous ECG monitoring has the potential to transform critical care for patients with IHCA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the UCLA CTSI Bioinformatics group for assistance with cohort identification.

Funding:

This research was supported by NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR001881. Duc H. Do is supported by NIH T32HL007895 and the UCLA Specialty Training and Advanced Research (STAR) Program. Xiao Hu is supported by NIH R01HL128679.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interest:

Noel G. Boyle has received speaking honoraria from Janssen Pharmaceutical. Other authors have no interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Parshuram CS, Dryden-Palmer K, Farrell C, Gottesman R, Gray M, Hutchison JS, Helfaer M, Hunt EA, Joffe AR, Lacroix J. Effect of a pediatric early warning system on all-cause mortality in hospitalized pediatric patients: the EPOCH randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1002–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, Bellomo R, Brown D, Doig G, Finfer S, Flabouris A, investigators Ms. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a clusterrandomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan PS, Khalid A, Longmore LS, Berg RA, Kosiborod M, Spertus JA. Hospital-wide code rates and mortality before and after implementation of a rapid response team. JAMA. 2008;300:2506–2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones DA, DeVita MA, Bellomo R. Rapid-Response Teams. New Engl J Med. 2011;365:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Do DH, Hayase J, Tiecher RD, Bai Y, Hu X, Boyle NG. ECG changes on continuous telemetry preceding in-hospital cardiac arrests. J Electrocardiol. 2015;48:1062–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attin M, Feld G, Lemus H, Najarian K, Shandilya S, Wang L, Sabouriazad P, Lin C-D.Electrocardiogram characteristics prior to in-hospital cardiac arrest. J Clin Monit Comput. 2015;29:385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding Q, Bai Y, Tinoco A, Mortara D, Do D, Boyle NG, Pelter MM, Hu X. Developing new predictive alarms based on ECG metrics for bradyasystolic cardiac arrest. Physiol Meas. 2015;36:2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lian J, Wang L, Muessig D. A Simple Method to Detect Atrial Fibrillation Using RR Intervals. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1494–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsipouras MG, Fotiadis DI, Sideris D. An arrhythmia classification system based on the RR-interval signal. Artif Intell Med. 2005;33:237–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Storey JD. The positive false discovery rate: a Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. The Ann Stat. 2003;31:2013–2035. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez J-C, Müller M. pROC: an opensource package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News 2002;2:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storey JD, Bass AJ, Dabney A, Robinson D. qvalue: Q-value estimation for false discovery rate control. R package version 2.12.0, http://github.com/jdstorey/qvalue 2015.

- 14.Morrison LJ, Neumar RW, Zimmerman JL, Link MS, Newby LK, McMullan PW, Hoek TV, Halverson CC, Doering L, Peberdy MA, Edelson DP. Strategies for Improving Survival After In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in the United States: 2013 Consensus Recommendations: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:1538–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Park SY, Meltzer DO, Hall JB, Edelson DP. Derivation of a cardiac arrest prediction model using ward vital signs. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2102–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X, Sokol S, Pettit N, Howell MD, Edelson DP. qSOFA, SIRS, and Early Warning Scores for Detecting Clinical Deterioration in Infected Patients Outside the ICU. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;195:906–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girotra S, Nallamothu BK, Spertus JA, Li Y, Krumholz HM, Chan PS. Trends in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Eng J Med. 2012;367:1912–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drew BJ, Harris P, Zègre-Hemsey JK, Mammone T, Schindler D, Salas-Boni R, Bai Y, Tinoco A, Ding Q, Hu X. Insights into the problem of alarm fatigue with physiologic monitor devices: a comprehensive observational study of consecutive intensive care unit patients. PloS one 2014;9:e110274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding Q, Bai Y, Mortara D, Do D, Boyle NG, Hu X. The predictive power of ECG metrics for bradyasystolic cardiac arrest. J Electrocardiol. 2014;47:907–908. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dilaveris PE, Färbom P, Batchvarov V, Ghuran A, Malik M. Circadian Behavior of P-Wave Duration, P-Wave Area, and PR Interval in Healthy Subjects. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2001;6:92–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finlay DD, Nugent CD, Donnelly MP, Lux RL. Eigenleads: ECG Leads for Maximizing Information Capture and Improving SNR. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2010;14:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaelides A, Ryan JM, VanFossen D, Pozderac R, Boudoulas H. Exercise-induced QRS prolongation in patients with coronary artery disease: A marker of myocardial ischemia. Am Heart J. 1993;126:1320–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rich MM, McGarvey ML, Teener JW, Frame LH. ECG changes during septic shock. Cardiology 2002;97:187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernández-Delgado M, Cernadas E, Barro S, Amorim D. Do we need hundreds of classifiers to solve real world classification problems. J Mach Learn Res. 2014;15:3133–3181. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myerburg RJ, Halperin H, Egan DA, Boineau R, Chugh SS, Gillis AM, Goldhaber JI, Lathrop DA, Liu P, Niemann JT. Pulseless Electric Activity Definition, Causes, Mechanisms, Management, and Research Priorities for the Next Decade: Report From a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Workshop. Circulation. 2013;128:2532–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhalala US, Bonafide CP, Coletti CM, Rathmanner PE, Nadkarni VM, Berg RA, Witzke AK, Kasprzak MS, Zubrow MT. Antecedent bradycardia and in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest mortality in telemetry-monitored patients outside the ICU. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1106–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Winslow C, Meltzer DO, Kattan MW, Edelson DP. Multicenter Comparison of Machine Learning Methods and Conventional Regression for Predicting Clinical Deterioration on the Wards. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:368–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu X An algorithm strategy for precise patient monitoring in a connected healthcare enterprise. npj Digit Med. 2019;2:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bai Y, Do DH, Harris PR, Schindler D, Boyle NG, Drew BJ, Hu X. Integrating monitor alarms with laboratory test results to enhance patient deterioration prediction. J Biomed Inform. 2015;53:81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergum D, Nordseth T, Mjølstad OC, Skogvoll E, Haugen BO. Causes of in-hospital cardiac arrest - Incidences and rate of recognition. Resuscitation. 2015;87:63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.