Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To evaluate patient responses on a survey of knowledge, perceptions, concerns and fears about complications related to pelvic reconstructive surgery (PRS). This is the first step to create a simplified, patient-centered Pelvic Floor Complication Scale (PFCS) that evaluates complications from both the patient and surgeon perspective.

METHODS:

Subjects for this prospective study included women > 18 years old planning surgery within 12 weeks or who had undergone PRS > 6 months ago. Patients were asked open-ended questions about postoperative complications as well as to rank the severity of potential PRS complications (as mild, moderate, severe). Using thematic analysis, responses were coded and analyzed using Dedoose1 (Version 8.0.35).

RESULTS:

33 women (16 preop, 17 postop) participated in telephone interviews (n=26) and focus groups (n=7). There were no differences in age, race, education, marital status and prior surgery. Specific complications such as a single UTI, short-term constipation (<2 weeks), persistent constipation (present preop), bladder injury not requiring repair or catheterization, vascular injury without sequelae and extra office visits were considered minor. New recurrent UTIs, new persistent constipation, worsening postop constipation (present preop), blood transfusion, readmission and reoperation were considered severe complications.

The most common themes included: fears of surgical failure, anesthesia, mesh erosion, discharge with a catheter and pain. Patients were overall very trusting of their FPMRS surgeons and potential risks did not impact surgical decisions.

CONCLUSION:

Our research findings provide significant insight into patient perceptions of complications related to PRS that will aid in future development of a patient-centered PFCS.

Keywords: Surgical Complications, Pelvic Surgery, Patient-Centered

INTRODUCTION

Pelvic floor disorders, such as pelvic organ prolapse, urinary incontinence, and, fecal incontinence often impair a woman’s quality-of-life but rarely result in significant morbidity. Pelvic reconstructive surgery (PRS) performed to correct these conditions, however, imparts risk of short and long-term complications. Benefits and risks of various treatment options including symptomatic and anatomic cure or improvement as well as perioperative and postoperative complications should be considered when making surgical decisions to ensure successful outcomes with high patient satisfaction.

Post-surgical complications are often difficult to quantify across studies and are not uniformly reported in the literature. The best-described complication scale to date is the Clavien-Dindo 2 system which classifies complications into 1 of 4 categories based on the type of therapy needed to correct the complication. The Clavien-Dindo system is reproducible, easily applied and has been used in PRS studies with an expanded time frame to include complications that occurred after discharge. 3,4 Nevertheless, Clavien-Dindo is neither condition-specific nor does it take into account issues associated with outpatient or short stay elective surgery for pelvic floor disorders, such as urinary retention or constipation Additionally, it was validated in a cohort of men and women, but women often rated complications as less severe than men, suggesting that a gender-specific scale may more accurately reflect women’s values and experiences. 5 To fill this gap, the Pelvic Floor Complication Scale 6 (PFCS) was developed and utilized in PRS. The PFCS was designed for all routes of pelvic surgery including vaginal, abdominal, and laparoscopic procedures with or without robotic assistance. The PFCS characterizes complications unique to prolapse and incontinence procedures including mesh/graft related complications, urinary retention and others.

While the PFCS has the potential to better reflect the overall severity of complications related to PRS as compared to the Clavien-Dindo scale, both scales examine complications through the surgeon’s perspective. In this study, we evaluated patient responses to questions regarding knowledge, perceptions, concerns and fears about complications related to PRS. We plan to use the results obtained in this qualitative analysis to construct a simplified PFCS that reflects the views of both patients and surgeons.

METHODS

Recruitment and participation

Patients for this prospective, cohort qualitative pilot study were recruited from patient lists of 5 board-certified, fellowship trained Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery (FPMRS) faculty to create a racially, ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample of patients undergoing a representative variety of standard PRS procedures for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Women 18 years or older were offered participation in either telephone interviews or focus groups. Approximately half the women were scheduled to undergo PRS within 12 weeks and had already undergone preoperative surgical planning and given informed consent, while the other half had undergone PRS in the past 6 to 12 months. We excluded women who were involved in a PRS related lawsuit, were unable to complete a written questionnaire with a 6–8th grade reading level, had limited English proficiency or were monolingual in a language other than English.

IRB approval was obtained. Focus group participants were contacted using a standardized script and written informed consent was obtained prior to conducting the focus group. Telephone interview participants were contacted by the research team and verbal informed consent was obtained using a standardized script. Demographic data and patient characteristics were collected including age, race/ethnicity, medical history and surgical history. A trained non-clinician with expertise in qualitative methods moderated the focus group and conducted a portion of the telephone interviews. The remaining telephone interviews were performed by an OB/GYN resident and a FPMRS fellow. All patients were asked open-ended questions about prior surgical experience and complications as well as focused questions ranking the severity (minor, moderate, severe) of various perioperative and postoperative surgical complications. All focus groups and telephone interviews were de-identified, audio-recorded, and transcribed.

Statistical Analysis

A convenience sample (a non-probability sample of available individuals) 7 of 4 focus groups, half preoperative and half postoperative, with 6 to 8 per group was estimated for enrollment in the initial phase of this study. However, due to difficulty coordinating focus groups of patients planning PRS surgery (preoperative group), IRB approval was obtained to conduct telephone interviews instead of focus groups for all remaining participants.

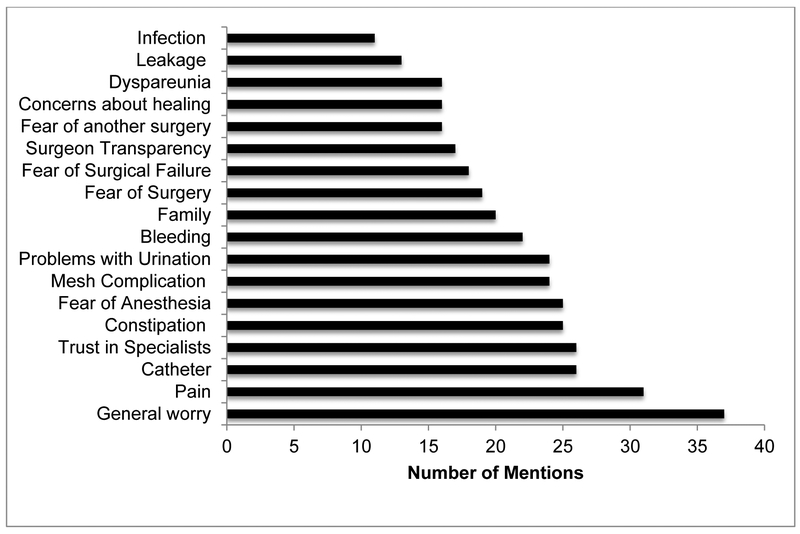

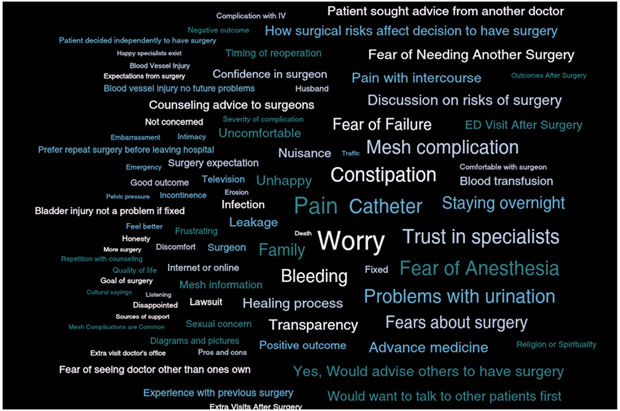

Two independent members of the research team carefully reviewed and analyzed the complete transcripts from telephone interviews and focus groups using Dedoose1A code was developed after the research team members noticed several instances where participants discussed concepts (for example pain, fear of catheters, etc). All transcripts from 26 telephone interviews and one focus groups were independently coded by two team members to refine and clarify the coding scheme. When disagreements in coding occurred, the two team members met to discuss this. If they were unable to come to a consensus, a third team member was enlisted to adjudicate the coding and final classification. We used the software program Dedoose 1 to index the data into excerpts according to codes. The final part of the analysis was to organize the codes into themes.8. Dedoose1 was used to quantify codes, link codes, and generate a “code cloud” (Figure 1). The results of this analysis were used to inform the research team of themes that were important to women with regard to complications. Ultimately, these themes were used to create patient-centered complication scale that is outside of the scope of this manuscript

Figure 1:

Frequency of Major Emerging Transcript Themes

Means and standard deviations or total numbers and percentiles were calculated for demographic data and preoperative and postoperative group comparisons were analyzed using t-tests. Comparisons between groups were done using Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test for categorical variables including ranking of complication data as minor, moderate, and severe between groups. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Minor complications were given a score of 1, moderate a score of 2, and, severe a score of 3. Data were analyzed using R Core Team 2015. 9

RESULTS

Thirty-three women (n= 16 pre-op, n=17 post-op) participated in telephone interviews (n=26) and focus groups (n=7). Pre-operative and postoperative patients did not differ significantly in age, race, education level and marital status (Table 1). The average age of the patients was 62.4 (±12) years. The majority were married (63.6%), white (62.5%), non-Hispanic (97.0%), and had some college or graduate education (81.7%). There were no differences between the telephone and focus group participants (data not shown).

Table 1.

Demographic Data of Study Population

| Demographics | Pre-operative (N=16) | Post-operative (N=17) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 62.8 (13.32) | 62.2 (11.2) | 0.89 |

| Race (n, %) | |||

| White | 11 (73.3%) | 9 (52.9%) | 0.36 |

| Black | 4 (26.7%) | 7 (41.2%) | |

| Other | 0 | 1 (5.9%) | |

| Ethnicity (n, %) | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 15 (93.8%) | 17 (100%) | 0.48 |

| Hispanic | 1 (6.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Multi-lingual (n, %) | |||

| No | 4 (25.0%) | 6 (35.3%) | 0.71 |

| Yes | 12 (75.0%) | 11 (64.7%) | |

| Marital Status (n, %) | |||

| Married | 9 (56.3%) | 12 (70.6%) | 0.34 |

| Divorced | 3 (18.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Separated | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | |

| Single | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (5.9%) | |

| Widowed | 2 (12.5%) | 3 (17.7%) | |

| Education Level | |||

| High School graduate degree | 6 (37.50%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.019 |

| Some College | 1 (6.3%) | 5 (29.4%) | |

| College graduate degree | 4 (25.0%) | 6 (35.3%) | |

| Some postgraduate | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (11.8%) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 5 (31.3%) | 4 (23.5%) | |

| Employed | |||

| No | 5 (31.2%) | 8 (47.1%) | 0.48 |

| Yes | 11 (68.8%) | 9 (52.9%) |

Patients were asked to rank the importance of descriptors for “bother”, “duration”, and “severity” as they relate to complications in general. They were requested to order them from 3 “most” to 1 “least” important with the ability to use the same number if equal importance. Patients recorded all 3 of the options as the “most” important 42.4% to 48.5% of the time. Comparing the overall average ranking selected, there were only minor differences that were not significant with mean scores (standard deviation) for “duration” being the highest at 2.3 (±0.8), “bother” next at 2.1 (±0.9) and “severity” the lowest at 1.9 (±1.0).

Patient responses to categorical questions pertaining to urinary tract infections, constipation, bladder injury, vascular injury/transfusion, reoperation and need for extra visits are presented in Table 2. The majority of patients reported a single UTI after surgery as a minor complication and recurrent UTIs as a severe complication. The responses were fairly evenly divided among the three levels for pre-existing UTIs that persisted after surgery. Similarly, the majority of patients considered new constipation after surgery lasting less than two weeks as a minor complication and new constipation that persisted beyond two weeks as a severe complication. Preexisting constipation that persisted after surgery was generally considered a minor complication while preexisting constipation that worsened was a severe complication. Bladder injury that did not require prolonged catheterization was a minor complication versus prolonged catheterization was reported as a moderate or severe complication. Similarly, vascular injury that was repaired intra-operatively and did not require a transfusion was mostly reported as a minor complication, whereas, injury that required transfusion was felt to be a severe complication. Patients generally considered the need for a reoperation as a severe complication. The severity ratings differed based on the timing of the reoperation. The majority felt undergoing a reoperation during the same admission was a severe complication, yet undergoing an outpatient reoperation after discharge was a moderate complication. Severity responses were evenly divided for those undergoing reoperation with readmission after discharge. Additional office visits were felt to be minor complications, whereas emergency room visits that required re-admission were severe complications and those that did not require re-admission were more moderate complications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Severity Rank of Various Surgical Complications

| Complications | Severity Rank (mean, SD) |

Severity Rank (N,%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Urinary tract infections | ||||

| Single | 1.2 (0.5) | 28 (84.9%) | 4 (12.1%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| Recurrent | 2.6 (0.6) | 1 (3.0%) | 13 (39.4% | 19 (57.6%) |

| Preexisting persists | 2.1 (0.8) | 9 (27.3%) | 12 (36.4%) | 12 (36.4%) |

| Constipation | ||||

| de novo, < 2 weeks | 1.4 (0.6) | 22 (66.7%) | 9 (27.3%) | 2 (6.1%) |

| de novo, persists | 2.4 (0.7) | 4 (12.1%) | 11 (33.3%) | 18 (54.6%) |

| Preexisting, persists | 1.5 (0.7) | 20 (60.6%) | 9 (27.3%) | 4 (12.1%) |

| Preexisting, worsened | 2.6 (0.7) | 3 (9.1%) | 9 (27.3%) | 21 (63.6%) |

| Bladder Injury | ||||

| Discharged without catheter | 1.1 (0.3) | 30 (90.9%) | 3 (9.1%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Discharged with catheter | 2.4 (0.6) | 2 (6.1%) | 17 (51.5%) | 14 (42.4%) |

| Vascular Injury / Bleeding | ||||

| Repaired, no transfusion | 1.6 (0.7) | 18 (54.6%) | 11 (33.3%) | 4 (12.1%) |

| Repaired, transfusion | 2.6 (0.7) | 3 (9.1%) | 8 (24.2%) | 22 (66.7%) |

| Reoperation | ||||

| In general | 2.4 (0.8) | 6 (18.2%) | 8 (24.2%) | 19 (57.6%) |

| During same admission | 2.4 (0.8) | 5 (15.2%) | 9 (27.3%) | 19 (57.6%) |

| After discharge, outpatient | 2.0 (0.7) | 7 (21.2%) | 18 (54.6%) | 8 (24.2%) |

| After discharge, inpatient | 2.0 (0.9) | 11 (33.3%) | 10 (30.3%) | 12 (36.4%) |

| Visits After Surgery | ||||

| Emergency room, with admission | 2.6 (0.6) | 1(3.1%) | 10 (30.30%) | 22 (66.7%) |

| Emergency room, no admission | 1.9 (0.8) | 10 (30.3%) | 15 (45.5%) | 8 (24.2%) |

| Additional office visits | 1.2 (0.6) | 27 (81.8%) | 4 (12.1%) | 2 (6.1%) |

Several themes emerged from analysis of telephone and focus group transcripts. Code analysis done in Dedoose1 (Version 8.0.35) was able to perform theme co-occurrence between individual themes as well as tabulate theme frequency. The most frequent theme co-occurrences were “counseling advice to surgeons” (a code used for any time a patient offered their opinion on the optimal language or tactic for preoperative counseling) and “transparency”; “trust in specialists” and “transparency”; “problems with urination” and “nuisance”; and “pain” with “experience with prior surgery”. Overall patients had a great deal of trust in their specialist surgeons. When asked “To what extent do you trust specialists to be transparent and reveal the risks and benefits of surgery?”, a patient responded, “I expect them to be 100 percent transparent, and that was absolutely my experience.” Another patient stated “I think my specialist was very clear and transparent. He was obviously upfront about all of the information he provided”. The most frequently referenced themes are displayed in Figure 1. Major themes included: generalized worry, concern about postoperative pain, concern about going home with a catheter, trust in specialists, constipation and rectal pain, fear of anesthesia, fear of mesh complications, and concerns about other problems with urination and bleeding. When asked how they felt about the possibility of a certain complications, women frequently responded that they would “be worried”. For example, when asked “How would you feel if you had an injury to the bladder during surgery?”, a patient replied “That would not be good…the fact that your bladder is injured…that would worry me a lot”. Other demonstrative comments from patients focused on constipation and rectal pain. “The complication I was most concerned about was rectal pain, I didn’t think it would ever go away.” Women were very fearful about needing to be discharged with a catheter. As stated by a patient, “For me I would rather be in more pain than have to wear a catheter”, and another said “I was going crazy with it for three days, I cannot imagine two weeks”. A “code cloud” of all notable themes from patient interviews is shown in Figure 2; word size correlates to the frequency of that particular theme.

Figure 2:

Code Cloud of Transcript Themes

DISCUSSION

The primary findings of this study demonstrate significant insight into patient perceptions of complications related to PRS that will aid in future development of a patient-centered Pelvic Floor Complication Scale (PFCS). Currently, little is known about how short and long-term complications impact patient satisfaction relative to cure and improvement of pelvic floor disorder symptoms. The Clavien-Dindo 5and PFCS6 correlated with quality of life outcomes, length of stay and overall satisfaction, but the correlations were generally weak. Surgeons emphasize cure and improvement as the primary outcome measure in studies and record and analyze complications as a secondary outcome. The Clavien-Dindo5 system has been widely adapted in PRS to help categorize and compare complications between studies even though it was designed to be used in an inpatient general surgery population. The original PFCS was created based on surgeon’s perceptions of severity and bother for complications associated with PRS.

In order to better understand the impact of complications on patient’s overall satisfaction, it is important to develop an evidence-based complication scale that reflects patient’s perceptions. Prior studies have shown discrepancies between patient and surgeon perceptions of complications where, for example, patients perceived many complications to be more severe than surgeons perceptions 5. Patients were also more likely to consider common perioperative events to be complications compared with surgeons (44% versus 8%, respectively, reported a perioperative complication).10 In our study, patients often cited constipation and temporary urinary catheterization as surgical complications even though they were warned that this was likely to occur in the 2 weeks following PRS. Our qualitative analysis demonstrates that specific complications such as a single UTI, de novo short-term constipation, bladder injury not requiring repair or catheterization, vascular injury without sequelae and extra office visits were considered minor by most patients. However, de novo recurrent UTIs, de novo persistent constipation, worsening pre-existing constipation, blood transfusion, readmission and reoperation were considered severe complications. There were no significant differences between complication rankings among preoperative and postoperative groups, but this study was underpowered to detect such a difference.

This study highlighted several themes related to surgical counseling and perceived complications that are important to women undergoing PFS. Women are fearful of pain, catheters, constipation, anesthesia, mesh complications, bleeding, and surgical failure. Many women are also concerned with the transparency of their surgeons during preoperative counseling. Other studies have shown the importance of patient satisfaction as a measure of their understanding of the informed consent process 11 Important co-occurrence of several themes from the qualitative data analysis were found between surgical counseling, transparency, and the use of diagrams and pictures in describing the surgical plan. These themes may help guide providers in addressing the true fears of their patients undergoing PRS.

This study addresses a gap in the literature and seeks to develop evidence-based tools to analyze patient-centered PRS outcomes. A strength of our study is the unique methodology in which women were allowed to provide both free responses to questions about complications and their surgical concerns, as well as categorizing their perceptions of severity for various specific postoperative complications. Qualitative analysis of themes provides an organic picture of what a relatively diverse population of women undergoing a variety of standard PRS considers to be important regarding their surgical experience.

Weaknesses of this study include: possible recall bias among the postoperative patients surveyed,, and non-random selection of patients for the study population from our practice. As the patients were non-randomly sampled, it is entirely possible that the patient’s chosen are more likely to engage with a research study and were unlikely to have significant anomalies in their care. In this particularly study, we did not ask specific questions about pain or mesh exposure, though this has been done on previous studies and will be addressed in future ones. Additionally, this population is a mixture of individual telephone interviews and focus groups because it was difficult to coordinate focus groups for the preoperative patients. Finally, the study population consists of a relatively small number of patients.

This study is most meaningful for its future applications. Both the original long version of the PFCS and Clavien-Dindo scales had limited overall predictive value for quality-of-life outcomes noted above, which potentially reflects discordance between surgeon-designed measures of morbidity and the patient’s subjective experience and tolerance of the complication. In the next steps of our study, the results presented here will be utilized to revise the long version of the PFCS into a shorter, simplified patient-centered PFCS that can be used to evaluate and compare complications in PRS. This patient-centered scale will be evaluated among both patients and surgeons for its utility and has been developed.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds Georgetown University and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (CTSA) - Pilot and Collaborative Studies Program (Matched Grant funding with MedStar Health Research Institute). Identifying Number: TR000101–04, IRB 2014–0974

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest, Dr. Robert E. Gutman: Boston Scientific Site PI for Uphold LITE 522 FDA trial and Strategic Advisory Board Member; Pelvalon Clinical Events Committee Chair (LIBERATE Trial)

Contributor Information

Jocelyn Fitzgerald, Georgetown University/MedStar Washington Hospital Center, 106 Irving St NW, 405 S, Washington, DC 20010, FPMRS Fellow PGY 6, Phone: 412 335 7863, jocelyn.j.fitzgerald@medstar.net.

Moiuri Siddique, Georgetown University/MedStar Washington Hospital Center, OBGYN Resident PGY4, moiuri.siddique@gunet.georgetown.edu.

Jeannine Marie Miranne, Harvard Medical School/Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Obstetrics and Gynecology, jmiranne@bwh.harvard.edu.

Pamela Saunders, Georgetown University, pamela.saunders@georgetown.edu.

Robert Gutman, Georgetown University/MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Ob/Gyn & Urology, robert.e.gutman@medstar.net.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dedoose. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2018. www.dedoose.com. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P-A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240(2):205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med 2010;362(22):2066–2076. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albo ME, Richter HE, Brubaker L, et al. Burch colposuspension versus fascial sling to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med 2007;356(21):2143–2155. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009;250(2):187–196. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutman RE, Nygaard IE, Ye W, et al. The pelvic floor complication scale: a new instrument for reconstructive pelvic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208(1):81.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A. Research Methods for Business Students. 6th ed. Pearson Education Limited; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creswell J Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.R Core Team. Vienna, Austria; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenton K, Pham T, Mueller E, Brubaker L. Patient preparedness: an important predictor of surgical outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;197(6):654.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallock JL, Rios R, Handa VL. Patient satisfaction and informed consent for surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217(2):181.e1–181.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]