Abstract

Objectives:

While fundamental frequency (F0) cues are important to both lexical tone perception and multi-talker segregation, F0 cues are poorly perceived by cochlear implant (CI) users. Adding low-frequency acoustic hearing via a hearing aid (HA) in the contralateral ear may improve CI users’ F0 perception. For English-speaking CI users, contralateral acoustic hearing has been shown to improve perception of target speech in noise and in competing talkers. For tonal languages such as Mandarin Chinese, F0 information is lexically meaningful. Given competing F0 information from multiple talkers and lexical tones, contralateral acoustic hearing may be especially beneficial for Mandarin-speaking CI users’ perception of competing speech.

Design:

Bimodal benefit (CI+HA – CI-only) was evaluated in 11 pediatric Mandarin-speaking Chinese CI users. In Experiment 1, speech recognition thresholds (SRTs) were adaptively measured using a modified coordinated response measure (CRM) test; subjects were required to correctly identify 2 keywords from among 10 choices in each category. SRTs were measured with CI-only or bimodal listening in the presence of steady-state noise SSN or competing speech with the same (M+M) or different voice gender (M+F). Unaided thresholds in the non-CI ear and demographic factors were compared to speech performance. In Experiment 2, SRTs were adaptively measured in SSN for recognition of 5 keywords, a more difficult listening task than the 2-keyword recognition task in Experiment 1.

Results:

In Experiment 1, SRTs were significantly lower for SSN than for competing speech in both the CI-only and bimodal listening conditions. There was no significant difference between CI-only and bimodal listening for SSN and M+F (p>0.05); SRTs were significantly lower for CI-only than for bimodal listening for M+M (p<0.05), suggesting bimodal interference. Subjects were able to make use of voice gender differences for bimodal listening (p<0.05), but not for CI-only listening (p>0.05). Unaided thresholds in the non-CI ear were positively correlated with bimodal SRTs for M+M (p<0.006), but not for SSN or M+F. No significant correlations were observed between any demographic variables and SRTs (p>0.05 in all cases). In Experiment 2, SRTs were significantly lower with 2 than with 5 keywords (p<0.05). A significant bimodal benefit was observed only for the 5-keyword condition (p<0.05).

Conclusions:

With the CI alone, subjects experienced greater interference with competing speech than with SSN and were unable to use voice gender difference to segregate talkers. For the CRM task, subjects experienced no bimodal benefit and even bimodal interference when competing talkers were the same voice gender. A bimodal benefit in SSN was observed for the 5-keyword condition, but not for the 2-keyword condition, suggesting that bimodal listening may be more beneficial as the difficulty of the listening task increased. The present data suggest that bimodal benefit may depend on the type of masker and/or the difficulty of the listening task.

Keywords: cochlear implant, bimodal, tonal language, speech in noise, competing speech

INTRODUCTION

Because temporal fine structure (TFS) information is generally not preserved by cochlear implant (CI) signal processing, and because CI users’ functional spectral resolution is generally poor (relative to normal hearing), perception of fundamental frequency (F0) cues is challenging for CI listeners. As such, CI users have difficulty with speech perception in noise, segregating competing talkers, talker identification, music perception, vocal emotion perception, prosody perception, and lexical tone perception (e.g., Fu et al., 1998, 2005; Friesen et al., 2001; Gfeller et al., 2002; Shannon et al., 2004; Stickney et al., 2004, 2007; Galvin et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2007; Chatterjee and Peng, 2008; Cullington and Zeng, 2008; Deroche et al., 2014; Chatterjee et al., 2015; Gaudrain and Başkent, 2018). For CI users with residual acoustic hearing in the non-implanted ear, combined acoustic and electric hearing (“bimodal listening”) may improve CI users’ perception of F0 cues. For English-speaking CI users, bimodal listening has been shown to offer an advantage over CI-only performance for speech perception in quiet and in noise, perception of competing speech, music perception, talker identification, etc. (e.g., Morera et al., 2005; Gifford et al., 2007; Kong and Carlyon, 2007; Dorman et al., 2008; Brown and Bacon, 2009; Zhang et al., 2010, 2013; Cullington and Zeng, 2011; Sheffield and Zeng, 2012; Yoon et al., 2012; Visram et al., 2012; Rader et al., 2013; Illg et al., 2014; Crew et al., 2015).

For tonal languages such as Mandarin Chinese, F0 cues are important for lexical tone perception, which in turn is important for word and sentence perception, at least in noise (Liang, 1963; Chen et al., 2014). Poor spectral resolution limits lexical tone perception in Mandarin-speaking Chinese CI users (e.g., Fu et al., 1998; Chatterjee and Peng, 2008; Luo et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2013; Deroche et al., 2014; Tao et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2018). Consequently, Mandarin-speaking CI users depend strongly on amplitude and duration cues that co-vary with F0 (Fu and Zeng, 2000). Increasing numbers of Mandarin-speaking Chinese CI patients use a hearing aid (HA) in the non-CI ear. Similar to bimodal studies with English-speaking CI users, Mandarin-speaking Chinese CI users have been shown to significantly benefit from bimodal listening for speech perception in quiet or in steady noise (e.g., Li et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2016; Yang and Zeng, 2017; Cheng et al., 2018; Tao et al., 2018a).

While normal-hearing (NH) listeners generally experience less interference from fluctuating maskers (e.g., gated noise, speech babble, competing speech) than from steady-state noise (SSN), CI users often experience greater interference from fluctuating maskers than from SSN (e.g., Nelson et al., 2003; Harley et al., 2004; Stickney et al., 2004; Fu and Nogaki, 2005; Cullington and Zeng, 2008; Eskridge et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2017). Different from SSN, which produces “energetic” masking at the auditory periphery, competing speech may produce energetic masking as well as “modulation” and “informational” masking, in which competing talkers interfere with each other at more central levels of auditory processing (Brungart, 2001a, b). Competing speech has more complex spectro-temporal dynamics than SSN, allowing NH listeners to perceive target speech in the spectral and/or temporal gaps of the masker speech. Due to the limited spectro-temporal resolution, CI users cannot take advantage of these spectro-temporal dynamics (Oxenham and Kreft, 2016). Voice gender differences allow for better segregation of competing speech (e.g., Brungart 2001b). Some previous studies have shown that CI users and NH subjects listening to CI simulations have difficulty using talker F0 differences between target and masker speech (e.g., Qin and Oxenham, 2006; Stickney et al., 2004, 2007). However, other studies have shown that CI patients are able to make use of F0 differences between competing talkers (e.g., Cullington and Zeng, 2008; Visram et al., 2012). Note that the F0 differences for competing talkers, test materials, and test methods differed among these studies, which might partly explain differences in F0 effects. Luo et al. (2009) showed that Mandarin-speaking CI users were unable to use voice gender differences to segregate concurrent vowels. With bimodal listening, English-speaking CI users are better able to segregate talkers according to voice gender differences than with the CI alone (e.g., Kong et al., 2005; Qin and Oxenham, 2006; Cullington and Zeng, 2011; Visram et al., 2012).

In China, the large majority of CI recipients are children, due to the Chinese government’s initiative to implant profoundly deaf children (Liang and Mason, 2003). Because auditory processing is still developing, children have greater difficulty with spectro-temporally degraded signals (as in the CI case) than do adults (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2000). For co-located speech and noise, NH children have greater difficulty with competing speech and fluctuating maskers than do NH adults, and often experience greater interference with dynamic maskers than with SSN (e.g., Hall et al., 2005, 2012; Wightman and Kistler, 2005; Buss et al., 2016; Ching et al., 2018; Koopmans et al., 2018). Mandarin-speaking CI children also experience greater difficulty in SSN and competing speech than do NH children, and greater difficulty with competing speech or babble than with SSN (e.g., Mao and Xu, 2017; Ren et al., 2018; Tao et al., 2018b). Tao et al. (2018b) found greater interference with competing speech than with SSN in CI children. While NH children were able to take advantage of voice gender differences in competing speech, CI children were not. SRTs for CI children were 3.4 and 3.6 dB for the male and female maskers, respectively; for NH children, SRTs were −8.4 and −16.1 dB for the male and female maskers, respectively. NH adults and children performed similarly with SSN; however, NH adults experienced less interference from competing speech than did NH children, highlighting age-related effects of speech-on-speech masking.

Previous pediatric CI and CI simulation studies with English-speaking listeners have shown significant bimodal benefits in noise, relative to CI-only performance (e.g., Ching et al., 2006; Cadieux et al., 2013; Carlson et al., 2015; Sheffield et al., 2016; Polonenko et al., 2018). Similarly, previous pediatric studies with Mandarin-speaking CI users have shown significant bimodal benefits in SSN (Yuen et al., 2008; Yang and Zeng, 2017; Cheng et al., 2018, Tao et al., 2018a). To date, no studies have explored bimodal benefits in Mandarin-speaking CI users in the context of competing speech, where better perception of F0 cues with contralateral acoustic hearing might benefit identification of lexical tones and segregation of competing talkers. In this study, bimodal benefit for recognition of target speech in SSN or competing speech was measured in pediatric Mandarin-speaking CI patients; performance was measured with the CI alone or with combined use of the CI and HA. In Experiment 1, the modified coordinate response measure (CRM) task used in Tao et al. (2018b) was used to measure target speech recognition in the presence of SSN or competing speech. In Experiment 2, performance in SSN was compared between recognition of 2 or 5 keywords to estimate the effects of task difficulty on bimodal benefit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Eleven Mandarin-speaking Chinese CI users (6 males and 5 females) with low-frequency residual hearing in the non-implanted ear participated in the study. The mean age at testing was 8.2 years (range = 6.0 to 12.5), the mean age at diagnosis of deafness was 2.7 years (range: 0 to 5.5) the mean duration of deafness was 1.1 years (range = 0.5 to 3.0), the mean CI experience was 4.5 years (range = 2.0 to 8.0), and the mean HA experience was 4.0 years (range = 0.5 to 8). Demographic data for the CI participants are shown in Table 1. The study and its consent procedure were approved by the local ethics committee (Ethics Committee of Eye and Ear, Nose, Throat Hospital of Fudan University; approval number: KY2012–009) and written informed consent was obtained from children’s parents before participation.

Table 1:

CI subject demographic information.

| Subject | Gender | Age at test (yrs) | Age at deaf (yrs) | Dur of deaf (yrs) | Etiology | CI ear | CI device | CI strategy | CI exp (yrs) | HA exp (yrs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | F | 9 | 3 | 1 | LVAS | L | MED-EL | FSP | 5 | 1 | |

| S2 | F | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | LVAS | R | MED-EL | FSP | 5.5 | 6 | |

| S3 | M | 7 | 0 | 3 | Unknown | R | MED-EL | FSP | 4 | 3.8 | |

| S4 | M | 6.5 | 2 | 1 | Unknown | R | Cochlear | ACE | 3.5 | 0.5 | |

| S5 | M | 8.5 | 4 | 0.5 | Unknown | L | Cochlear | ACE | 4 | 8 | |

| S6 | F | 9 | 5.5 | 0.5 | LVAS | R | AB | F120 | 3 | 6 | |

| S7 | M | 12.5 | 4 | 1 | Unknown | R | Cochlear | ACE | 7.5 | 8 | |

| S8 | M | 10 | 0 | 2 | LVAS | R | Cochlear | ACE | 8 | 2.5 | |

| S9 | M | 8 | 2.5 | 1 | Unknown | R | MED-EL | FSP | 4.5 | 3 | |

| S10 | F | 6 | 3 | 1 | LVAS | L | Cochlear | ACE | 2 | 2 | |

| S11 | F | 6 | 3.5 | 0.5 | LVAS | R | AB | F120 | 2 | 3 | |

| AVE | 8.2 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 4.5 | 4.0 | ||||||

| STD | 1.9 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

Unaided and aided thresholds were measured in sound field using warble tones for audiometric frequencies 125, 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz. Figure 1 shows unaided and aided audiometric thresholds in the non-implanted ear for audiometric frequencies (and averaged across audiometric frequencies). Unaided thresholds generally exhibited a low-pass filter characteristic (solid line in left panel of Fig. 1), with mean thresholds beginning to drop at 1000 Hz. There was a large inter-subject variability in unaided thresholds, with some subjects exhibiting only moderate hearing loss and others exhibiting severe-to-profound hearing loss at different audiometric frequencies. Aided thresholds also exhibited a low-pass filter characteristic (solid line in right panel of Fig. 1), with mean thresholds beginning to drop at 2000 Hz. Again, there was substantial inter-subject variability, with some subjects exhibiting normal threshold levels at some frequencies and others exhibiting moderate-to-severe hearing loss even with the HA. Pearson correlations showed no significant relationship between unaided and aided thresholds at any frequency (p>0.05 in all cases).

Figure 1.

Boxplots of unaided (left panel) and aided thresholds in the non-CI ear (right panel), as a function of audiometric frequency and averaged across audiometric frequencies. The boxes show the 25th and 75th percentiles, the horizontal line shows the median, the squares show the mean, the error bars show the 10th and 90th percentiles, and the circles show outliers (>90th percentile, <10th percentile). The thick solid line shows the mean thresholds across audiometric frequency.

Target speech stimuli, masker stimuli, and testing

Experiment 1

The Closed-set Mandarin Speech (CMS; Tao et al., 2017; 2018b) test materials were used to test speech understanding with the different maskers. The CMS test materials consist of familiar words selected to represent the natural distribution of vowels, consonants, and lexical tones found in Mandarin Chinese. Ten key words in each of five categories (Name, Verb, Number, Color, and Fruit) were produced by a native Mandarin talker, resulting in a total of 50 words that can be combined to produce 100,000 unique sentences. Note that while the long-term root-mean-square (RMS) amplitude was normalized across stimuli, duration cues (which co-vary with F0 in Mandarin tones) were preserved. As such, during the random generation of the target and masker sentences, differences in duration cues may have allowed for opportunities to glimpse longer-duration target words in the presence of shorter-duration masker words.

Speech recognition was measured in the presence of SSN or a competing male or female talker. The target sentences were produced by a single male talker (mean F0 across all words = 136 Hz). The SSN masker was white noise that was band-pass filtered to match the average spectrum (across all words) of the target speech. Speech maskers were produced by a different male talker (mean F0 = 178 Hz) or a female talker (mean F0 = 246 Hz).

Speech reception thresholds (SRTs), defined as the target-to-masker ratio (TMR) that produced 50% correct word recognition in noise or competing speech (Plomp and Milpen, 1979), were adaptively measured using a modified CRM test (Bolia et al., 2000; Brungart, 2001ab; Tao et al., 2017, 2018b). Similar to CRM tests, two keywords (randomly selected from the Number and Color categories) were embedded in a carrier sentence uttered by the target talker. The first word in the target sentence was always the Name “Xiaowang,” followed by randomly selected words from the remaining categories. For the SSN masker condition, steady noise was presented beginning 500 ms before the target sentence and ending 500 ms after the target sentence. For the competing male and female talkers, words were randomly selected from each category, excluding the words used in the target sentence. Thus, the target phrase could be (in Mandarin) “Xiaowang sold Four Blue strawberries” or “Xiaowang chose One Green banana” (keywords in bold italic), while the masker could be “Xiaozhang saw Three Red kumquats,” “Xiaodeng took Six White papayas,” etc. Subjects were instructed to pick the correct words from the target sentence for only the Number and Color categories; no selections could be made from the remaining categories, which were greyed out.

All stimuli were presented in the sound field at 65 dBA via a single loudspeaker; subjects were seated directly facing the loudspeaker at a 1-m distance. The SRTs were measured with CI-only and bimodal listening; subjects were tested using the clinical settings for each device, which were not changed throughout the study. During each test trial, a sentence was presented at the target TMR; the initial TMR was 10 dB. The subject clicked on one of the 10 responses for each of the Number and Color categories. If the subject correctly identified both keywords, the TMR was reduced by 4 dB (initial step size); if the subject did not correctly identify both keywords, the TMR was increased by 4 dB. After two reversals, the step size was reduced to 2 dB. The SRT was calculated by averaging the last 6 reversals in TMR. If there were fewer than 6 reversals within 20 trials, the test run was discarded and another run was measured. Two test runs were completed for each condition and the SRT was averaged across runs.

Figure 2 shows waveforms (left column), low-frequency pitch and amplitude contours (middle column), and electrodograms (right column) for the target keyword “8” produced by the target male talker (1st and 4th rows), and for the masker word “4” produced by competing male (2nd row) and female talkers (5th row), and for the combined target and masker talkers at 0 dB TMR for M+M (3rd row) and M+F masker conditions (6th row). The pitch and amplitude contours were estimated for low-pass filtered speech (500-Hz cutoff frequency) to simulate acoustic information that might be available in the non-CI ear. The electrodograms represent the CI stimulation pattern across electrodes for the default frequency allocation (input frequency range: 188–7938 Hz) and stimulation rate (900 pulses per second per electrode) for Cochlear Corp. devices using the ACE strategy (8 maxima). In this example, with the competing male talker, the amplitude of the target is greater than that of the masker for the first 180 ms (column 1, 3rd row), which might facilitate identification of the target call word. With the competing female talker (column 1, 6th row), there is greater masking during the initial portion of the target than with the competing male talker, which might make identification of the target call word more difficult. As shown in the second column, the amplitude and pitch contours are generally similar. When target and masker are combined at 0 dB TMR, the amplitude and pitch contours generally add together, with the larger instantaneous amplitude driving the combination. As such, the combined target and masker pitch contours transition from flat to falling. The electrodograms (right column) also show that the larger instantaneous amplitude drives the combination of the target and masker. For the M+M combination, the stimulation pattern is relatively flat (similar to the target), with some diffusion beginning at 180 ms, where the peak amplitude transitions from the target to the masker. This transition is less apparent for the M+F combination.

Figure 2.

Waveforms (left column), low-frequency amplitude and pitch contours (middle column), and CI electrodograms (right column) for an example target keyword (“8”) produced by the male target talker (1st and 4th rows), an example masker word (“4”) produced by a competing male (2nd row) or female talker (5th row), and mixed together at 0 dB TMR (3rd and 6th rows). The low-frequency amplitude and pitch contours were extracted after low-pass filtering to 500 Hz to simulate the available cues with contralateral acoustic hearing. The electrodograms were generated according to the default stimulation parameters used in Cochlear Corp. devices.

Experiment 2

The target stimuli were similar to those in Experiment 1, except that SRTs were adaptively measured in SSN for 5 keywords. Note that with the CMS closed-set design, SRTs with 5 keywords could not be measured in competing speech because of difficulty in cueing the target talker and sentence, especially with a competing male talker. Thus, SRTs for 5 keywords were measured only in SSN.

For the 5-keyword condition, during each test trial, a target sentence was randomly generated by selecting 1 of the 10 words from each of the Name, Verb, Number, Color, and Fruit categories. The target sentence was presented at the target TMR; the initial TMR was 10 dB. The subject clicked on one of the 10 responses for each of the 5 categories. If the subject correctly identified all 5 words, the TMR was reduced by 4 dB (initial step size); if the subject did not correctly identify all 5 words, the TMR was increased by 4 dB. After two reversals, the step size was reduced to 2 dB. The SRT was calculated by averaging the last 6 reversals in TMR. If there were fewer than 6 reversals within 20 trials, the test run was discarded and another run was measured. Two test runs were completed for each condition and the SRT was averaged across runs.

RESULTS

Experiment 1

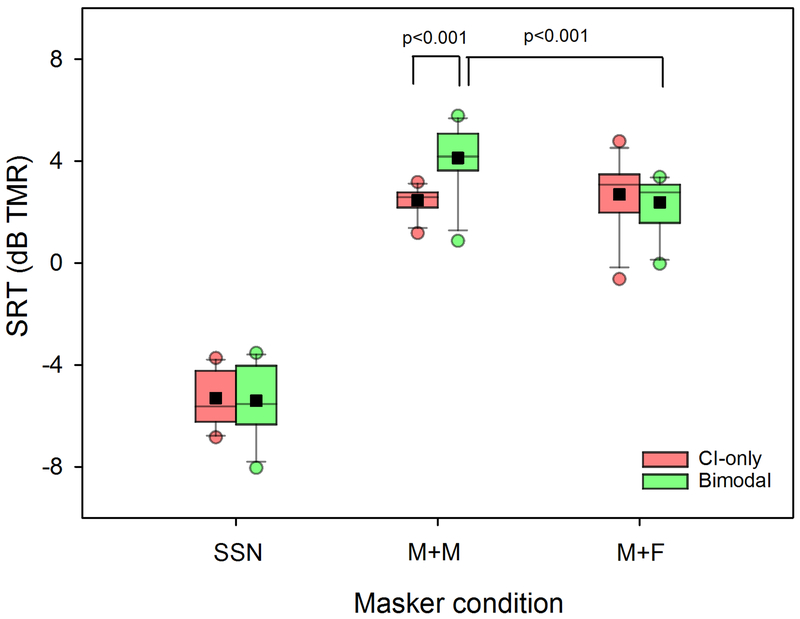

Figure 3 shows boxplots of SRTs for the different masker conditions with CI-only or bimodal listening. For SSN, the mean SRTs were −5.3 dB (range: −3.7 to −6.8) and −5.4 dB (range: −3.5 to −8.0) for CI-only and bimodal listening, respectively. For M+M, the mean SRTs were 2.5 dB (range: 1.2 to 3.2) and 4.1 dB (range: 0.9 to 5.8) for CI-only and bimodal listening, respectively. For M+F, the mean SRTs were 2.7 dB (range: −0.6 to 4.8) and 2.4 dB (range: 0.0 to 3.4) for CI-only and bimodal listening, respectively.

Figure 3.

Boxplots of SRTs with CI-only or bimodal listening for the different masker conditions in Experiment 1. The boxes show the 25th and 75th percentiles, the horizontal line shows the median, the squares show the mean, the error bars show the 10th and 90th percentiles, and the circles show outliers (>90th percentile, <10th percentile). The brackets indicate significant differences between listening and/or masker conditions.

A two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) was performed, with masker condition (SSN, M+M, M+F) and listening mode (CI-only, bimodal) as factors. Results showed significant effects of masker conditions [F(2, 20)=613.8, p<0.001] and listening mode [F(1, 10)= 5.4, p=0.043]; there was a significant interaction [F(2, 20)=9.9, p=0.001]. Bonferroni pairwise comparisons showed that, with CI-only listening, SRTs were significantly lower for SSN than for M+M or M+F (p<0.05 in both cases), with no significant difference between M+M and M+F (p>0.05). For bimodal listening, SRTs were significantly lower for SSN than for M+M or M+F (p<0.05 in both cases), and significantly lower for M+F than for M+M (p<0.05). The SRTs were significantly lower with CI-only than with bimodal listening for M+M (p<0.05), with no significant difference between CI-only and bimodal listening for SSN or M+F (p>0.05 in both cases).

The left panel of Figure 4 shows SRTs with bimodal listening for each masker condition as a function of unaided mean threshold in the non-CI ear (across audiometric frequencies between 125 and 2000 Hz); the lines show linear regressions, and r and p values are shown in the legend. For M+M and M+F, SRTs worsened with increasing unaided thresholds. Correlations between bimodal SRTs and audiometric thresholds are shown in Table 2. The correlations were performed after removing outliers; note that the outliers were not necessarily the same at each frequency. As shown in Figure 1, the filled circles represent the outlier thresholds at each frequency and across frequencies (>90th percentile, <10th percentile). Outliers in terms of unaided thresholds were removed to avoid overly low or high thresholds that might have driven the subsequent correlations. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons (adjusted p<0.006). For SSN and M+F, there were no significant correlations at any frequency (p>0.05 in all cases). For M+M, significant correlations were observed for 500 Hz (p=0.003) and averaged across frequencies (p=0.004). Interestingly, CI-only SRTs for M+M were correlated with unaided acoustic thresholds at 250 Hz (p=0.003) and 500 Hz (p=0.005). Aided thresholds were not correlated with SRTs for any listening condition (p>0.05 in all cases).

Figure 4.

Left panel: Bimodal SRTs for Experiment 1 as a function of mean unaided thresholds in the non-CI ear averaged across audiometric frequencies between 125 and 2000 Hz. The circles, triangles, and squares show SRTs with the SSN, M+M, and M+F masker conditions, respectively; the open symbols show those outliers in terms of unaided thresholds (see Fig. 1). The solid lines show linear regressions fit to data after removing outliers; r and p values are shown in the legend. Right panel: Similar as left panel, but for the change in SRT (bimodal – CI-only) as a function of mean unaided thresholds in the non-CI ear; values >0 indicate bimodal interference, and values <0 indicate bimodal benefit.

Table 2:

Unaided thresholds in the non-CI ear versus bimodal SRTs, CI-only SRTs, or the difference in SRTs (bimodal – CI). Results of Pearson correlations are shown after removing outliers in terms of unaided thresholds; note that outliers were not necessarily the same subjects across frequencies. The italics and asterisks indicate significant correlations after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (p<0.006).

| Frequency (Hz) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 125 | 250 | 500 | 1000 | 2000 | Mean | |||

| n | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | ||

| SSN | Bimodal | r | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.08 | −0.25 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| p | 0.460 | 0.120 | 0.830 | 0.517 | 0.976 | 0.921 | ||

| CI | r | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.02 | −0.35 | 0.48 | |

| p | 0.094 | 0.053 | 0.316 | 0.960 | 0.320 | 0.159 | ||

| Bimodal - CI | r | −0.22 | 0.02 | −0.40 | −0.37 | 0.30 | −0.64 | |

| p | 0.510 | 0.952 | 0.258 | 0.326 | 0.400 | 0.049 | ||

| M+M | Bimodal | r | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.82 |

| p | 0.027 | 0.007 | 0.003* | 0.283 | 0.212 | 0.004* | ||

| CI | r | 0.64 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.74 | |

| p | 0.033 | 0.003* | 0.005* | 0.292 | 0.403 | 0.014 | ||

| Bimodal - CI | r | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.69 | |

| p | 0.043 | 0.028 | 0.033 | 0.418 | 0.160 | 0.026 | ||

| M+F | Bimodal | r | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.65 | 0.58 |

| p | 0.193 | 0.100 | 0.357 | 0.505 | 0.043 | 0.082 | ||

| CI | r | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.30 | −0.10 | 0.31 | 0.01 | |

| p | 0.510 | 0.194 | 0.400 | 0.799 | 0.392 | 0.985 | ||

| Bimodal - CI | r | 0.12 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.35 | |

| p | 0.722 | 0.976 | 0.988 | 0.539 | 0.551 | 0.329 | ||

The right panel of Figure 4 shows the difference in SRTs between the bimodal and CI-only listening conditions (i.e., “bimodal benefit”) for each masker condition as a function of unaided mean threshold in the non-CI ear. Complete correlation results are shown in Table 2. The correlations were performed after removing outliers; note that the outliers were not necessarily the same at each frequency. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons (adjusted p<0.006). There were no significant correlations between bimodal benefit and mean unaided thresholds for SSN, M+M and M+F (p>0.05 in all cases). Aided thresholds were not correlated with bimodal benefit for any listening condition (p>0.05 in all cases).

Demographic variables age at testing, duration of deafness, CI experience, and HA experience were compared to SRTs with bimodal or CI-only listening for each masker condition. For all masker conditions, no significant correlations were observed between SRTs with either listening condition and any of the demographic variables (p>0.05 in all cases).

Experiment 2

Figure 5 shows boxplots of SRTs with SSN for the different number of keywords with CI-only or bimodal listening. For 5 keywords, the mean SRTs were 0.7 dB (range: −2.1 to 2.8) and −1.2 dB (range: −3.5 to −1.6) for the CI-only and bimodal listening conditions, respectively. For 2 keywords, the mean SRTs were −5.3 dB (range: −3.7 to −6.8) and −5.4 dB (range: −3.5 to −8.0) for the CI-only and bimodal listening conditions, respectively. A two-way RM ANOVA was performed, with number of keywords (5, 2) and listening mode (CI-only, bimodal) as factors. Results showed significant effects for number of keywords [F(1, 20)=149.3 p<0.001] and listening mode [F(1, 10)= 7.2, p=0.023]; there was a significant interaction [F(1, 10)=11.1, p=0.008]. Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons showed that SRTs were significantly lower with 2 than with 5 keywords in each listening mode (p<0.05 in both cases), and significantly lower for bimodal than for CI-only listening only for the 5-keyword condition.

Figure 5.

Boxplots of SRTs in SSN with CI-only or bimodal listening for the different number of keywords in Experiment 2; note that the data for the 2-keyword condition are from Experiment 1 and are the same as for the SSN data shown in Figure 3. The boxes show the 25th and 75th percentiles, the horizontal line shows the median, the squares show the mean, the error bars show the 10th and 90th percentiles, and the circles show outliers (>90th percentile, <10th percentile). The brackets indicate significant differences between listening and/or masker conditions.

Unaided thresholds at each audiometric frequency were compared to bimodal SRTs, CI-only SRTs, and bimodal benefit for the 5- and 2-keyword conditions. When outliers were excluded, and after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, there were no significant correlations between SRTs with either keyword condition and any frequency (p>0.05 in all cases).

DISCUSSION

In this study, understanding of Mandarin Chinese in steady noise or speech maskers was measured in pediatric Mandarin-speaking CI users with CI-only or bimodal listening. Contrary to our hypothesis, no significant bimodal benefit was observed for any of the masker conditions in Experiment 1; indeed, significant bimodal interference was observed for the M+M masker condition. In Experiment 2, SRTs were significantly lower with 2 than with 5 keywords, reflecting the relative difficulties in the listening task. Somewhat consistent with our hypothesis, a significant bimodal benefit was observed for only the 5-keyword condition. Below we discuss the results in greater detail.

Bimodal benefit versus listening demands

In previous CI and CI simulation studies, unimodal and bimodal performance has been evaluated for different patient groups (e.g., adults, children), as well as different listening (e.g., in quiet, steady noise, speech babble, or competing speech), language (e.g., tonal, non-tonal), and speech test conditions (e.g., phoneme recognition, lexical tone recognition, vocal emotion recognition, word recognition, CRM, sentence recognition). As such, the degree of bimodal benefit may vary greatly across studies and may depend on the various conditions tested. For non-tonal languages (e.g., English, German, Spanish), some studies have shown significant and substantial bimodal benefits for phoneme, word, or sentence recognition in quiet or in noise (e.g., Morera et al., 2005; Gifford et al., 2007; Dorman et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2010, 2013; Yoon et al., 2012; Rader et al., 2013; Illg et al., 2014; Crew et al., 2015). Similarly, previous studies have shown bimodal benefits for Mandarin-speaking CI users for speech perception in quiet or in SSN (e.g., Li et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2016; Yang and Zeng, 2017; Cheng et al., 2018; Tao et al., 2018a). In this study, a bimodal benefit was observed in SSN only for the more challenging listening task, and no bimodal benefit was observed when listening to competing speech.

In Experiment 1 of this study, a modified CRM task was used to evaluate speech performance. No bimodal benefit was observed for any of the masker conditions, with bimodal interference observed when the target and masker talker gender was the same. This result is in contrast from findings by Visram et al. (2012), where adult English-speaking CI users were tested using a CRM task and using competing speech with the same or different talker gender. In that study, significant bimodal benefits were observed for all competing speech conditions. Note that mean SRTs were somewhat higher in this study than in Visram et al. (2012). It is possible that the stimuli and methods used in this study may have been more challenging than in Visram et al. (2012). In this study, there were 10 options for Name, Number and Color versus 8 options for Name and Color and 4 options for Number in Visram et al. (2012); as such, chance level was lower in this study (1/100) than in Visram et al. (2012; 1/32). Children were tested in this study versus adults in Visram et al. (2012). Perhaps, adults are better able to obtain bimodal benefit than children. In this study, there was no bimodal benefit (relative to CI-only performance) for competing speech when the voice gender was different. Bimodal interference was observed for competing speech when the voice gender was the same, possibly due to confusion between F0 cues for voice pitch and lexical tones. Another possible explanation for the lack of bimodal benefit is abnormal fusion between acoustic and electric hearing. Reiss et al. (2014) reported broad binaural fusion (1–4 octaves) and large inter-aural pitch mismatch between acoustic and electric stimulation in bimodal CI listeners. The authors suggested that poor binaural fusion may underlie the lack of bimodal benefit and even bimodal interference between acoustic and electric hearing. In this study, listeners may have been unable to take advantage of the fine-structure cues in acoustic hearing due to interference by the CI, where pitch cues are poorly encoded and only weakly available in temporal envelope information.

The lack of bimodal benefit in Experiment 1 may have been related to the specific stimuli and methods used in the modified CRM task. Experiment 2 tested whether bimodal benefits might be observed when the difficulty of the listening task was increased (identification of 2 or 5 keywords). Note that the chance level increased from 1/100 for 2 keywords to 1/100,000 for 5 keywords. In the adaptive SRT task used in this study, this would likely have the effect of shifting the underlying psychometric function, with a higher SRT for the 5-keyword condition (as shown in the present results). A greater number of keywords might also have a greater demand in working memory. Previous studies (e.g., Watson et al., 2007; Pisoni et al., 2011; Nittrouer et al., 2013) have shown that auditory working memory is poorer in English-speaking CI children than in NH children. Tao et al. (2014) also found that forward and backward digit span scores (measures of auditory working memory) were poorer in Mandarin-speaking CI users than in NH listeners. It is possible that contralateral acoustic hearing might be beneficial near the limits of auditory working memory. A significant bimodal benefit was observed for the 5-keyword condition, consistent with Crew et al. (2016) who used similar test materials and methods with English-speaking CI users, and broadly consistent with previous studies with Mandarin-speaking CI users (e.g., Li et al., 2014; Yang and Zeng, 2017; Cheng et al., 2018). No bimodal benefit was observed for the 2-keyword condition, possibly because the listening task was less taxing on working memory.

Note that in Experiment 2, SRTs were not measured with competing speech because of difficulties in cueing the target speech with the CMS stimuli and test procedure. One alternative would have been to test recognition of 5 keywords in the presence of a fixed masking sentence produced by different talkers than the masker talker. However, it is possible that listeners would have become entrained to the masker sentence which might have affected SRTs. Another alternative would have been to have a leading phrase spoken by the target talker that preceded the masked target phrase. However, because talker identification is generally poor with CI-only listening (e.g., Vongphoe and Zeng, 2005; Cullington and Zeng, 2011), it would have likely been difficult to track the target talker once the competing speech was presented.

Taken together, data from this and previous studies suggest that bimodal benefit may depend on the difficulty of the listening task and listening demands. This study presents a new finding of a general lack of bimodal benefit (and even bimodal interference) for a CRM task with steady noise or competing speech.

Interference from competing speech versus SSN

In Experiment 1, SRTs with CI-only and bimodal listening were significantly poorer with competing speech than with SSN, consistent with previous studies with English-speaking CI users (e.g., Nelson et al., 2003; Qin and Oxenham, 2003; Fu and Nogaki, 2005; Stickney et al., 2004, 2007; Cullington and Zeng, 2008). Work by Oxenham and Kreft (2014, 2016) and Croghan and Smith (2018) suggests that the poor spectral resolution associated with CIs may smear the inherent fluctuations in steady noise, allowing for less effective masking in CI users than dynamic interferers such as competing speech. The CI-only results are consistent with Tao et al. (2018b), who found that pediatric Mandarin-speaking CI users experience greater interference from competing speech than from SSN, using the same stimuli and methods as used in this study. The present data suggest that Mandarin-speaking CI users have greater difficulty with competing speech than with SSN for CI-only listening, and may have even greater difficulty with competing speech for bimodal listening, especially when F0 cues overlap.

For hearing-impaired and CI listeners, it is worth noting that broadened auditory filters and/or channel interaction may smear spectral cues. For these listeners, F0 differences in the stimuli (which may stimulate spectrally remote regions in the normal cochlea and thus result in limited energetic masking) may not be resolved and may effectively result in some degree of energetic masking. The compressive amplitude mapping associated with CIs may also affect the “perceptual” SNR to be less than the input SNR. Modulation masking at spatially remote regions may also have played a role in the present pattern of results. Work by Chatterjee and colleagues (Chatterjee, 2003; Chatterjee and Oba, 2004; Chatterjee and Kulkarni, 2018) has shown significant envelope interference (modulation masking) in CI listeners even for widely separated electrodes. Thus, there may be more interaction at the periphery among temporal envelopes with competing speech, which may partly explain the generally poorer CI performance with dynamic maskers than with SSN.

Effect of voice gender differences in competing speech

With the CI alone, subjects were unable to use voice gender differences between the target and masker speech, consistent with some previous CI studies with English-speaking (Stickney et al., 2004, 2007) and Mandarin-speaking CI users (Luo et al., 2009; Tao et al., 2018b), but not others (e.g., Cullington and Zeng, 2008, 2010; Visram et al., 2012; Pychny et al., 2011). In Visram et al (2012), English-speaking CI users were able to take advantage of voice gender differences with CI-only listening for a CRM task similar to that used in this study. As noted above, differences in stimuli and test methods, as well as differences between tonal and non-tonal languages and between pediatric and adult CI listeners, may explain differences in masker gender effects between studies. The importance of F0 cues to Mandarin speech perception may partly explain the difficulty pediatric CI users experienced with competing speech. While co-varying amplitude and duration cues also provide lexical tone information (Fu and Zeng, 2005) when F0 information is not available, these cues are much less accessible with competing speech (see Fig. 2).

With bimodal listening, the present subjects were able to use voice gender differences, in that SRTs were significantly lower in the M+F than in the M+M condition. Interestingly, bimodal listening did not offer a significant advantage over the CI alone for the M+F condition. However, the bimodal interference observed for the M+M condition was not observed for the M+F condition. In this sense, contralateral acoustic hearing was sensitive to voice gender differences in competing speech. This is consistent with many previous studies with English-speaking CI users that showed increased bimodal benefit for larger F0 separations (e.g., Kong et al., 2005; Qin and Oxenham, 2006; Cullington and Zeng, 2011; Psychny et al., 2011; Visram at al., 2012). In this study, while bimodal listening offered no significant advantage over CI-only listening for competing speech, performance significantly worsened when F0 cues were overlapping. Again, the importance of F0 cues to tonal languages may explain some of the differences in the patterns of results across studies.

Relationship between unaided thresholds in the non-CI ear and bimodal SRTs and benefit

After removing outliers in terms of unaided thresholds and correcting for multiple comparisons, significant correlations were observed between bimodal SRTs and unaided thresholds at 500 Hz and across all frequencies only for the M+M condition. Segregation of competing male talkers would have been more difficult than segregation of male and female talkers. And while there was significant bimodal interference relative to CI-only performance, the correlation suggests that interference was reduced for subjects with lower unaided thresholds. To the extent that unaided thresholds may relate to acoustic frequency resolution, the data suggest that frequency resolution was very important to segregate talkers with the same voice gender, and perhaps less important when F0 differences were large between talkers.

No significant correlations were observed between bimodal benefit for the M+M condition and unaided thresholds. However, subjects with higher unaided thresholds generally experienced greater bimodal interference, especially when the target and masker voice gender was the same.

The significant relationship between unaided thresholds and bimodal SRTs for the M+M condition is consistent with Zhang et al. (2013), who found a significant relationship between bimodal benefit for speech and unaided thresholds. Zhang et al. (2013) also found that unaided thresholds in the non-CI ear were significantly correlated with spectral modulation detection (SMD) thresholds (a measure of frequency selectivity), and that SMD thresholds were significantly correlated with bimodal benefit. This suggests that, beyond audibility, unaided thresholds may reflect the spectral resolution in the non-CI ear. Cheng et al. (2018) also found a significant relationship between bimodal benefit for speech recognition in quiet and unaided thresholds using similar stimuli and test methods as in this study. In this study, unaided thresholds at any frequency were not significantly correlated with bimodal SRTs or bimodal benefit for the SSN and M+F masker conditions. Previous studies with adult English-speaking bimodal CI listeners have also shown no correlation between unaided thresholds and bimodal SRTs and/or bimodal benefit for speech in noise or multi-talker babble (e.g., Ching et al., 2004; Gifford et al., 2007; Blamey et al., 2015). Note that there are many methodological differences among all these studies that may have contributed to the variable findings, such as differences in stimuli (CNC words in quiet, AzBio sentences in noise, CMS stimuli in noise), language (non-tonal versus tonal), subject age (adults versus children), test paradigm (closed versus open set), etc. Given the greater difficulty in segregating competing male voices (which would require greater frequency resolution), unaided thresholds may have reflected some aspect of frequency resolution for the M+M condition. For the M+F condition, F0 differences were sufficiently large and may not have required as good resolution. For recognition of 5 keywords in SSN, audibility with aided acoustic hearing may have been sufficient to perceive important voicing cues, and may not have required as much frequency resolution as for the M+M condition.

Unaided thresholds between 250 and 500 Hz were significantly correlated with CI-only SRTs for the M+M masker condition. Mean CI-only SRTs were approximately 1 dB lower in this study than in Tao et al. (2018). Note that for 9 out of the 11 subjects, mean unaided thresholds across 125, 250 and 500 Hz were <70 dB HL. This suggests that acoustic cues in the non-CI ear may have been available for some subjects even without the HA. Given the presentation level (65 dBA), the target speech may have been partly audible for some subjects at some frequencies. Also, given that unaided thresholds were measured in sound field, it is also possible that there may have been some residual acoustic hearing in the CI ear. It is unfortunate that in this study, the non-implanted ear was not pugged and/or muffed to reduce the contribution of residual contralateral acoustic hearing to CI-only performance. A still better approach would have been to measure unaided thresholds in each ear using insert earphones (which would provide a more accurate measure than in sound field) and to test speech perception with direct connection to the CI ear and insert earphone to the contralateral ear (i.e., using custom amplification and bypassing the HA). However, the present testing method (in sound field with the CI on and the HA on or off) may better reflect the contribution of aided acoustic hearing in the non-CI ear to bimodal benefit under everyday listening conditions.

Conclusions

Mandarin Chinese speech perception was measured in pediatric CI patients in the presence of competing noise or speech while listening only with electric hearing (CI-only) or with combined acoustic and electric hearing (bimodal). In Experiment 1, SRTs were measured in the presence of SSN or competing speech using a modified CRM task. In Experiment 2, speech perception in SSN was compared between listening tasks that required identification of 2 or 5 keywords. Major findings include:

Subjects generally experienced greater interference from competing speech than from SSN for both CI-only and bimodal listening.

Subjects experienced no bimodal benefit (relative to CI-only listening) for SSN or competing speech.

When the voice gender was the same for masker and target speech, subjects experienced greater interference when contralateral acoustic hearing was added to the CI, compared with CI-only listening. For bimodal listening, subjects experienced less interference when the voice gender for masker and target speech was different. When the voice gender was different between competing talkers, there was no significant difference between bimodal and CI-only listening. For tonal languages such as Mandarin Chinese, F0 cues important for both lexical tone and talker identity may negatively interact.

For competing speech, significant correlations were observed between unaided acoustic thresholds in the non-CI ear (at 500 Hz and averaged across all frequencies) and bimodal SRTs when the target and masker voice gender was the same. No significant correlations were observed between unaided acoustic thresholds and bimodal SRTs with SSN or when the target and masker voice gender was different.

A significant bimodal benefit in SSN was observed when recognition of 5 keywords was required, but not when recognition of 2 keywords was required (Exp. 2), suggesting that contralateral acoustic hearing may be especially beneficial as the difficulty of the listening task increases.

The pattern of results suggests that bimodal benefits in noise may be different for Mandarin-speaking CI users than previously observed for English-speaking CI users, and may depend on the listening task and/or the type of masker used.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All authors listed in the article contributed toward the work reported in this submission. Yang-Wenyi Liu and Duo-Duo Tao were involved in data collection, statistical analysis, interpretation of the data and preparation of the article. Xiaoting Cheng and Yilai Shu were involved in data collection and interpretation of the data. Bing Chen, Qian-Jie Fu and John J. Galvin III were involved in conception of work, experimental software and hardware set up, drafting work for important intellectual content, final approval of version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

We thank the subjects for their participation in this study. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01–004792); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81600796, 81570914, and 81700925); the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province for Young Scholar (20160344) and for Colleges and Universities (16KJB320011); the Key Medical Discipline Program of Suzhou (SZXK201503); and the China Scholarship Council (201706100146).

REFERENCES

- Bolia RS, Nelson WT, Ericson MA, et al. (2000). A speech corpus for multitalker communications research. J Acoust Soc Am. 107, 1065–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blamey PJ, Maat B, Başkent D, et al. (2015). A retrospective multicenter study comparing speech perception outcomes for bilateral implantation and bimodal rehabilitation. Ear Hear. 36, 408–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CA, Bacon SP (2009). Achieving electric-acoustic benefit with a modulated tone. Ear Hear. 30(5), 489–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D (2001a). Evaluation of speech intelligibility with the coordinate response measure. J Acoust Soc Am. 109, 2276–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D (2001b). Informational and energetic masking effects in the perception of two simultaneous talkers. J Acoust Soc Am. 109, 1101–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss E, Leibold LJ, Hall III JW (2016). Effect of response context and masker type on word recognition in school-age children and adults. J Acoust Soc Am. 140, 968–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadieux JH, Firszt JB, Reeder RM (2013). Cochlear implantation in nontraditional candidates: preliminary results in adolescents with asymmetric hearing loss. Otol Neurotol. 34, 408–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson ML, Sladen DP, Haynes DS, et al. (2015). Evidence for the expansion of pediatric cochlear implant candidacy. Otol Neurotol. 36, 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M (2003). Modulation masking in cochlear implant listeners: envelope versus tonotopic components. J Acoust Soc Am. 113, 2042–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Kulkarni AM (2018). Modulation detection interference in cochlear implant listeners under forward masking conditions. J Acoust Soc Am. 143, 1117–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Oba SI (2004). Across- and within-channel envelope interactions in cochlear implant listeners. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 5, 360–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Peng SC (2008). Processing F0 with cochlear implants: Modulation frequency discrimination and speech intonation recognition. Hear Res. 235, 143–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Zion DJ, Deroche ML, et al. (2015). Voice emotion recognition by cochlear-implanted children and their normally-hearing peers. Hear Res. 322, 151–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Wong LLN, Hu Y (2014). Effects of lexical tone contour on Mandarin sentence intelligibility. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 57, 338–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Chang R, Lin C, et al. (2016). Mandarin tone and vowel recognition in cochlear implant users: Effects of talker variability and bimodal hearing. Ear Hear. 37, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Liu Y, Wang B, et al. (2018). The benefits of residual hair cell function for speech and music perception in pediatric bimodal cochlear implant listeners. Neural Plast. 2018, 4610592. doi: 10.1155/2018/4610592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching TY, Incerti P, Hill M (2004). Binaural benefits for adults who use hearing aids and cochlear implants in opposite ears. Ear Hear. 25, 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching TY, Incerti P, Hill M, et al. (2006). An overview of binaural advantages for children and adults who use binaural/bimodal hearing devices. Audiol Neurootol. 11 Suppl 1, 6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching TY, Zhang VW, Flynn C, et al. (2018). Factors influencing speech perception in noise for 5-year-old children using hearing aids or cochlear implants. Int J Audiol. 57, S70–S80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crew JD, Galvin JJ, Landsberger DM, et al. (2015). Contributions of electric and acoustic hearing to bimodal speech and music perception. PLoS One. 10, e0120279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crew JD, Galvin JJ 3rd, Fu QJ (2016). Perception of sung speech in bimodal cochlear implant users. Trends Hear. 20, pii: 2331216516669329. doi: 10.1177/2331216516669329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croghan NB, Smith ZM (2018). Speech understanding with various maskers in cochlear-implant and simulated cochlear-implant hearing: Effects of spectral resolution and implications for masking release. Trends Hear. 22, 2331216518787276. doi: 10.1177/2331216518787276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullington HE, Zeng FG (2008). Speech recognition with varying numbers and types of competing talkers by normal-hearing, cochlear-implant, and implant simulation subjects. J Acoust Soc Am. 123, 450–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullington HE, Zeng FG (2011). Comparison of bimodal and bilateral cochlear implant users on speech recognition with competing talker, music perception, affective prosody discrimination, and talker identification. Ear Hear. 32, 16–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche ML, Lu HP, Limb CJ, et al. (2014). Deficits in the pitch sensitivity of cochlear-implanted children speaking English or Mandarin. Front Neurosci. 8, 282. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, Gifford R, Spahr A, et al. (2008). The benefits of combining acoustic and electric stimulation for the recognition of speech, voice and melodies. Audiol Neurootol. 13, 105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg LS, Shannon RV, Martinez AS, et al. (2000). Speech recognition with reduced spectral cues as a function of age. J Acoust Soc Am. 107, 2704–2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskridge EN, Galvin JJ III, Aronoff JM, et al. (2012). Speech perception with music maskers by cochlear implant users and normal-hearing listeners. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 55, 800–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen LM, Shannon RV, Baskent D, et al. (2001). Speech recognition in noise as a function of the number of spectral channels: comparison of acoustic hearing and cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Am. 110, 1150–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu QJ, Nogaki G (2005). Noise susceptibility of cochlear implant users: the role of spectral resolution and smearing. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 6, 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu QJ, Zeng FG (2000). Identification of temporal envelope cues in Chinese tone recognition. Asia Pac J Speech Lang Hear. 5, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fu QJ, Chinchilla S, Nogaki G, et al. (2005). Voice gender identification by cochlear implant users: the role of spectral and temporal resolution. J Acoust Soc Am. 118, 1711–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu QJ, Zeng FG, Shannon RV, et al. (1998). Importance of tonal envelope cues in Chinese speech recognition. J Acoust Soc Am. 104, 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin JJ III, Fu QJ, Nogaki G (2007). Melodic contour identification by cochlear implant listeners. Ear Hear. 28, 302–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudrain E, Başkent D (2018). Discrimination of voice pitch and vocal-tract length in cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 39, 226–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfeller K, Turner C, Mehr M, et al. , (2002). Recognition of familiar melodies by adult cochlear implant recipients and normal-hearing adults. Cochlear Implants Int. 3, 29–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford RH, Dorman MF, McKarns S, et al. (2007). Combined electric and contralateral acoustic hearing: word and sentence intelligibility with bimodal hearing. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 50, 835–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JW III, Buss E, Grose JH (2005). Informational masking release in children and adults. J Acoust Soc Am 118, 1605–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JW, Buss E, Grose JH, et al. (2012). Effects of age and hearing impairment on the ability to benefit from temporal and spectral modulation. Ear Hear. 33, 340–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt RF, Kirk KI, Eisenberg LS, et al. (2005). Spoken word recognition development in children with residual hearing using cochlear implants and hearing AIDS in opposite ears. Ear Hear. 26, 82S–91S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illg A, Bojanowicz M, Lesinski-Schiedat A, et al. (2014). Evaluation of the bimodal benefitin a large cohort of cochlear implant subjects using a contralateral hearing aid. Otol Neurotol. 35, e240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong YY, Carlyon RP (2007). Improved speech recognition in noise in simulated binaurally combined acoustic and electric stimulation. J Acoust Soc Am. 121, 3717–3727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong YY, Stickney GS, Zeng FG (2005). Speech and melody recognition in binaurally combined acoustic and electric hearing. J Acoust Soc Am. 117, 1351–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans WJA, Goverts ST, Smits C (2018). Speech recognition abilities in normal-hearing children 4 to 12 years of age in stationary and interrupted noise. Ear Hear. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YX, Zhang G, Galvin JJ 3rd, et al. (2014). Mandarin speech perception in combined electric and acoustic stimulation. PLoS One. 9(11): e112471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Q, Mason B (2013). Enter the dragon – China’s journey to the hearing world. Cochlear Implants Int. 14, S26–S31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang ZA (1963). The auditory perception of Mandarin Tones. Acta Phys Sin. 26, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Liu YW, Tao DD, Jiang Y, et al. (2017). Effect of spatial separation and noise type on sentence recognition by Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users. Acta Otolaryngol. 137, 829–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Fu QJ, Galvin JJ 3rd. (2007). Vocal emotion recognition by normal-hearing listeners and cochlear implant users. Trends Amplif 11, 301–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Fu QJ, Wei CG, et al. (2008). Speech recognition and temporal amplitude modulation processing by Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users. Ear Hear, 29, 957–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Fu QJ, Wu HP, et al. (2009). Concurrent-vowel and tone recognition by Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users. Hear Res. 256, 75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Xu L (2017). Lexical tone recognition in noise in normal-hearing children and prelingually deafened children with cochlear implants. Int J Audiol. 56, S23–S30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morera C, Manrique M, Ramos A, et al. (2005). Advantages of binaural hearing provided through bimodal stimulation via a cochlear implant and a conventional hearing aid: a 6-month comparative study. Acta Otolaryngol. 125, 596–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PB, Jin SH, Carney AE, et al. (2003). Understanding speech in modulated interference: cochlear implant users and normal-hearing listeners. J Acoust Soc Am. 113, 961–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nittrouer S, Caldwell-Tarr A, Lowenstein JH (2013). Working memory in children with cochlear implants: problems are in storage, not processing. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 77, 1886–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham AJ, Kreft HA (2014). Speech perception in tones and noise via cochlear implants reveals influence of spectral resolution on temporal processing. Trends Hear. 18, pii: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham AJ, Kreft HA (2016). Speech masking in normal and impaired hearing: Interactions between frequency selectivity and inherent temporal fluctuations in noise. Adv Exp Med Biol. 894, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng SC, Lu HP, Lu N, et al. (2017). Processing of acoustic cues in lexical-tone identification by pediatric cochlear-implant recipients. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 60, 1223–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Kronenberger WG, Roman AS, et al. (2011). Measures of digit span and verbal rehearsal speed in deaf children after more than 10 years of cochlear implantation. Ear Hear. 32, 60S–74S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomp R, Mimpen AM (1979). Speech-reception threshold for sentences as a function of age and noise level. J Acoust Soc Am. 66, 1333–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polonenko MJ, Papsin BC, Gordon KA (2018). Limiting asymmetric hearing improves benefits of bilateral hearing in children using cochlear implants. Sci Rep. 8, 13201. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31546-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychny V, Landwehr M, Hahn M, et al. (2011). Bimodal hearing and speech perception with a competing talker. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 54, 1400–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin MK, Oxenham AJ (2003). Effects of simulated cochlear-implant processing on speech reception in fluctuating maskers. J Acoust Soc Am. 114, 446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin MK, Oxenham AJ (2006). Effects of introducing unprocessed low-frequency information on the reception of envelope-vocoder processed speech. J Acoust Soc Am. 119, 2417–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rader T, Fastl H, Baumann U (2013). Speech perception with combined electric-acoustic stimulation and bilateral cochlear implants in a multisource noise field. Ear Hear. 34, 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss LA, Ito RA, Eggleston JL, et al. (2014). Abnormal binaural spectral integration in cochlear implant users. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 15, 235–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C, Yang J, Zha D, et al. (2018). Spoken word recognition in noise in Mandarin-speaking pediatric cochlear implant users. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 113, 124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon RV, Fu QJ, Galvin J 3rd. (2004). The number of spectral channels required for speech recognition depends on the difficulty of the listening situation. Acta Otolaryngol. Suppl 552, 50–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield BM, Zeng FG (2012). The relative phonetic contributions of a cochlear implant and residual acoustic hearing to bimodal speech perception. J Acoust Soc Am. 131, 518–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield SW, Simha M, Jahn KN, et al. (2016). The effects of acoustic bandwidth on simulated bimodal benefit in children and adults with normal hearing. Ear Hear. 37, 282–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn-Cunningham BG. Object-based auditory and visual attention. Trends Cogn Sci. 12, 182–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickney GS, Zeng FG, Litovsky R, et al. (2004). Cochlear implant speech recognition with speech masker. J Acoust Soc Am. 116, 1081–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickney GS, Assmann PF, Chang J, et al. (2007). Effects of cochlear implant processing and fundamental frequency on the intelligibility of competing sentences. J Acoust Soc Am. 122, 1069–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao DD, Deng R, Jiang Y, et al. (2014). Contribution of auditory working memory to speech understanding in mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users. PLoS One. 9, e99096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao DD, Deng R, Jiang Y, et al. (2015). Melodic pitch perception and lexical tone perception in Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 36, 102–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao DD, Fu QJ, Galvin JJ 3rd, et al. (2017). The development and validation of the Closed-set Mandarin Sentence (CMS) test. Speech Comm. 92, 125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao DD, Liu JS, Yang ZD, et al. (2018a). Bilaterally combined electric and acoustic hearing in Mandarin-speaking listeners: The population with poor residual hearing. Trends Hear. 22, 2331216518757892. doi: 10.1177/2331216518757892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao DD, Liu Y, Fei Y, et al. (2018b). Effects of age and duration of deafness on Mandarin speech understanding in competing speech by normal-hearing and cochlear implant children, JASA-EL, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visram AS, Kluk K, McKay CM (2012). Voice gender differences and separation of simultaneous talkers in cochlear implant users with residual hearing. J Acoust Soc Am. 132, EL135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vongphoe M, Zeng FG (2005). Speaker recognition with temporal cues in acoustic and electric hearing. J Acoust Soc Am. 118, 1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Liu B, Zhang H, et al. (2013). Mandarin lexical tone recognition in sensorineural hearing-impaired listeners and cochlear implant users. Acta Otolaryngol. 133, 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson DR, Titterington J, Henry A, et al. (2007). Auditory sensory memory and working memory processes in children with normal hearing and cochlear implants. Audiol Neurootol. 12, 65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman FL, Kistler DJ (2005). Informational masking of speech in children: effects of ipsilateral and contralateral distracters. J Acoust Soc Am. 118, 3164–3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HI, Zeng FG (2017). Bimodal benefits in Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users with contralateral residual acoustic hearing. Int J Audiol. 56, S17–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon YS, Li Y, Fu QJ (2012). Speech recognition and acoustic features in combined electric and acoustic stimulation. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 55, 105–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen KC, Cao KL, Wei CG, et al. (2009). Lexical tone and word recognition in noise of Mandarin-speaking children who use cochlear implants and hearing aids in opposite ears. Cochlear Implants Int. 10, 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Dorman MF, Spahr AJ (2010). Information from the voice fundamental frequency (F0) region accounts for the majority of the benefit when acoustic stimulation is added to electric stimulation. Ear Hear. 31, 63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Spahr AJ, Dorman MF, (2013). Relationship between auditory function of nonimplanted ears and bimodal benefit. Ear Hear. 34, 133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]