Abstract

A hallmark of cancer is genomic instability, which can enable cancer cells to evade therapeutic strategies. Here we employed a computational approach to uncover mechanisms underlying cancer mutational burden by focusing upon relationships between 1) translocation breakpoints and the thousands of G4 DNA-forming sequences within retrotransposons impacting transcription and exemplifying probable non-B DNA structures and 2) transcriptome profiling and cancer mutations. We determined the location and number of G4 DNA-forming sequences in the Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 38 and found a total of 358,605 covering ~13.4 million bases. By analyzing >97,000 unique translocation breakpoints from the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (COSMIC), we found that breakpoints are overrepresented at G4 DNA-forming sequences within hominid-specific SVA retrotransposons, and generally occur in tumors with mutations in tumor suppressor genes, such as TP53. Furthermore, correlation analyses between mRNA levels and exome mutational loads from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) encompassing >450,000 gene-mutation regressions revealed strong positive and negative associations, which depended upon tissue of origin. The strongest positive correlations originated from genes not listed as cancer genes in COSMIC; yet, these show strong predictive power for survival in most tumor types by Kaplan-Meier estimation. Thus, correlation analyses of DNA structure and gene expression with mutation loads complement and extend more traditional approaches to elucidate processes shaping genomic instability in cancer. The combined results point to G4 DNA, activation of cell cycle/DNA repair pathways, and mitochondrial dysfunction as three major factors driving the accumulation of somatic mutations in cancer cells.

Keywords: Genome instability, G-quadruplexes, cancer mutations, translocation breakpoints, mitochondrial dysfunction, replication stress

1. INTRODUCTION

Genomic instability, increased proliferation and escape from apoptosis are hallmarks of cancer (Macheret and Halazonetis 2015). A recent survey of >11000 tumor samples identified ~300 genes (cancer-driver genes) whose somatic mutations in terms of base substitutions are directly linked to malignancy (Bailey et al. 2018). Another ~1100 genes may support tumorigenesis through alterations in their expression profiles as a consequence of copy-number alterations, gene fusions, and other types of genomic rearrangements (Zhang et al. 2018). A separate study suggests >700 cancer-driving genes (Sondka et al. 2018). Despite the differences in these estimates, these studies point to the vast repertoire of targets available to the cell for tumor initiation and progression. In addition to the gene expression profiles, chromatin remodeling is also altered in cancer, which modulates genome-wide enhancer sequences to either upregulate or repress genes (Chen et al. 2018). Such genomic alterations are seen not only in adult but also in pediatric tumors (Grobner et al. 2018, Ma et al. 2018), implicating DNA mutations and epigenetic changes in steering a normal cell into a malignant phenotype. Somatic mutations in driver genes are often instigated by predisposing germline variants, such as in BRCA1 and BRCA2, and impinge on 8 major cellular processes, with alterations in genes involved in maintaining genome integrity, such as the Fanconi anemia pathway, and in 10 signaling pathways (RTK/RAS, Nrf2, PI3K, TGFβ, Wnt, Myc, TP53, cell cycle, Hippo, Notch) as being among the most commonly altered (Chae et al. 2016, Ding et al. 2018, Sanchez-Vega et al. 2018).

Elucidating the mechanisms through which mutations arise is central to understanding and strategically targeting tumorigenesis. By extracting patterns of base changes in cancer genomes, ~30 distinct signatures have been catalogued (Forbes et al. 2015), which inform on molecular processes likely to lead to mutations from either extrinsic (ultraviolet light, smoking, chemicals) or intrinsic (APOBEC misediting, DNA repair deficiencies, defective polymerase ε) sources (Alexandrov et al. 2013, Helleday et al. 2014). Patterns of base substitutions have also been associated with direct damage to DNA bases by oxidants (Bacolla et al. 2013, Temiz et al. 2015), such as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS respectively) (Turrens 2003), which rise in tumor cells following glucose deprivation, deregulation of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and other organelles (endoplasmic reticulum, lysosomes and peroxisomes) (Gorlach et al. 2015, Panieri and Santoro 2016).

In addition, recent research suggests that mutation loads arise as a secondary effect from oncogene-dependent transcriptional stimulation of transcription factors, which then activate genes responsible for uncontrolled replication (Kotsantis et al. 2016). This sustained proliferation contributes to a condition referred to as “replication stress”, a potent inducer of genomic instability (Hills and Diffley 2014, Macheret and Halazonetis 2015, Zheng et al. 2016) triggered by a buildup of ssDNA from RPA depletion (Toledo et al. 2017), the accumulation of secondary DNA structures, R-loops, collisions between replication and transcription (Hamperl and Cimprich 2016, Wang and Vasquez 2017), and other factors. Indeed, the formation of non-B DNA structures, such as cruciforms, triplexes, G4 structures and Z-DNA, has been reported to contribute in genomic instability (Bacolla et al. 2016, Georgakopoulos-Soares et al. 2018, Zhao et al. 2018), possibly following nuclease cleavage (Zhao et al. 2018) or replication fork collapse (Wang and Vasquez 2017). In view of the relationships between non-B DNA-structure formation and impaired transcription and replication, we reasoned it would seem sensible to further explore the roles of DNA structure impacting transcription and of transcription profiling in cancer mutational loads.

Herein, we use a computational approach to address two questions. First, although G4 DNA is conventionally associated with telomeres and gene regulatory regions (Hansel-Hertsch et al. 2016, Liu et al. 2016), thousands of identical G4 DNA-forming sequences are present within retrotransposons in the human genome (Kejnovsky et al. 2015, Lexa et al. 2014, Sahakyan et al. 2017), raising the possibility that these impact transcription and act as hubs for rearrangements in cancer. Second, as studies are only beginning to explore the relationships between transcriptome profiling and mutational burden in cancer (Buccitelli et al. 2017, Koplev et al. 2018), we reasoned that connections between activated cell cycle and replication stress warrant more effort in this area.

By analyzing >97000 unique translocations breakpoints from COSMIC we show here that breakpoints are overrepresented at G4 DNA-forming sequences within hominid-specific SVA retrotransposons, but surprisingly they appear to be excluded from older L1 elements, upon which SVAs depend for retrotranspositional activity (Raiz et al. 2012). Tumor samples with translocation breakpoints at G4 DNA-forming sequences are also more likely to carry mutations in TP53 and less likely to harbor pathologic mutations in KRAS and CTNNB1, supporting a role for TP53 mutations in G4 DNA-induced instability.

Correlation analyses between mRNA levels and mutational loads from TCGA encompassing >450,000 gene-mutation regressions revealed the existence of strong associations, both positive and negative, which are dependent upon tissue of origin. Enrichment analyses for the strongest correlated genes identified two distinct pathways common to more than one tumor type: cell cycle together with DNA repair in 4 tumors (KICH, LUAD, PRAD and LGG), and mitochondrial respiration in 3 tumors (STAD, THCA and CHOL). Three singleton tumors (CESC, SKCM and BRCA) were also enriched in separate pathways. Thus, correlation analyses of G4 DNA structure and gene expression with mutation loads complement and extend more traditional approaches to elucidate sources of genomic instability in cancer. Taken together these results point to G4 DNA, the replication stress response and mitochondrial dysfunction as major factors impacting accumulation of somatic mutations in cancer cells and meriting attention for cancer etiology and therapeutic strategies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cell culture and detection of G4 DNA in cells

HeLa cells were purchased from ATCC and grown in DMEM medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. HAP1 cells were purchased from Horizon Discovery and cultured in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were seeded onto glass coverslips and grown for 24 h, washed twice with PBS and fixed for 20 min with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. After rinsing twice with PBS, cells were permeabilized for 30 min with 0.1% saponin in PBS, treated with RNase A (Roche) and subsequently blocked in 2% BSA blocking buffer for 1 h. Next, cells were incubated with the anti-G-quadruplex DNA 1H6 (Millipore) antibody (1:200) overnight at 4°C. Coverslips were rinsed four times with PBS and subsequently incubated with anti-Mouse IgG Atto 488 (Sigma-Aldrich) (1:200) for 1 h at room temperature followed by further four washes in PBS. Cells were then stained with 100 nM Acti-stain™ 670 phalloidin (Cytoskeleton, Inc) for 30 min followed by four washes in PBS. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides using DAPI-containing mounting media (Invitrogen) and analyzed using an LSM710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG).

2.2. G4 DNA-forming sequences at cancer translocation breakpoints

We identified all sequences in GRCh38/hg38 potentially forming G4 DNA structures using a custom C++ script that retrieved strings matching the regular expression (G3N1–7)≥3G3 and its complement (C3N1–7)≥3C3, as well as similar regular expressions that added 5, 7, or 10 bases at each end. Scripts were run in a parallel environment using the Message Passing Interface (MPI) standard on Linux clusters at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (Austin, TX).

We retrieved the dataset of translocation breakpoints in cancer genomes from file CosmicBreakpointsExport.tsv.gz (release v85) available at COSMIC, https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/). These breakpoints were resolved at the bp level and mapped to specific hg38 genomic coordinates. We selected the translocations labeled “Interchromosomal unknown type” and “Interchromosomal reciprocal translocation”; the first entry represents frequent complex translocations between two or more chromosomes; the second defines rare reciprocal translocations between two separate chromosomes. Chromosome Y was excluded from the analyses. We defined a translocation breakpoint at a G4 DNA-forming sequence if its coordinate was within 5 bases of a G4 DNA-forming sequence. To generate random genomic coordinates we used bedtools and toBitToFa to obtain a list of 50 bp sequences from which we excluded those containing any N; the middle position was selected as the random genomic coordinate. The occurrence of pathologic mutations in cancer-related genes from patients with and without translocation breakpoints at G4 DNA was assessed from file CosmicMutantExportCensus.tsv.gz (release v85), also from COSMIC, after selecting the entries labeled as “pathogenic”.

G4 DNA-forming sequences present within non-LTR transposons were retrieved based on the abundance of hits sharing identical sequence composition (including 5, 7, and 10 flanking bases). The localization of these hits within either LINE (L1) or Composite (SVA) transposable elements was confirmed by mapping them onto hg38.

2.3. Cancer gene expression and mutation datasets

We used the TCGA-Assembler suite (Wei et al. 2018) with the assayPlatform option set to gene.normalized_RNAseq to obtain the normalized Rsem RNA-seq gene expression data from TCGA (https://cancergenome.nih.gov) project. The TCGA-Assembler was also used to retrieve the clinical patient data and the somatic mutations specific to the tumor tissues, i.e. single base substitutions and small insertion/deletions in exons genome-wide specific to the tumor but not the matched normal samples. A total of 32 datasets were analyzed; we were unable to examine the UCEC dataset because of inconsistencies in patient ID codes. Data were processed with in-house scripts (C++ and Bash) to obtain correlations between the expression of each gene and the number of somatic mutations in cancer patients. P-values were obtained from the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the F distribution using F = t2, where , r the regression coefficient and n the number of observations, using the C++ BOOST library. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were computed using the R libraries “dplyr”, “survival” and “survminer”. Gene enrichment analyses were conducted using the DAVID Bioinformatics Resource 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) and the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis).

3. RESULTS

3.1. G4 DNA elicits translocations in cancer genomes

We reasoned that DNA secondary structure (and the consequent tertiary structure) is a probable factor in the differential sensitivity to genome stress during replication and transcription in cancer cells. One of the major types of non-B DNA structure involves the formation of G4 DNA; we therefore focused attention on experimentally and computationally examining G4 forming sequences in cancer genomes as exemplary regions of non-B-DNA.

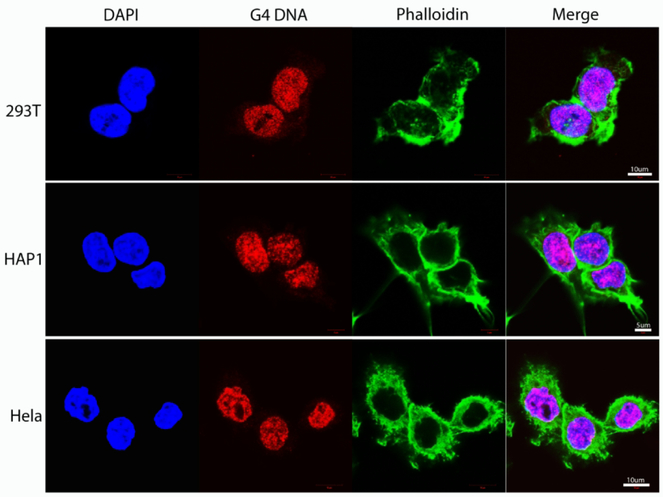

3.1.1. Translocations in cancer genomes are enriched at G4 DNA-forming sequences

To assess whether G4 DNA structures are present at substantial levels in cancer cell chromosomal DNA, we used fluorescence microscopy to stain common laboratory cell lines (293T, derived from human embryonic kidney, HAP1, derived from a male with chronic myelogenous leukemia, and HeLa obtained from a cervical cancer) with a G4 DNA-structure specific antibody, along with staining for chromosomal DNA with DAPI and cytoplasmic actin filaments with phalloidin. Merging of the fluorescent emission spectra showed extensive G4 DNA staining throughout the nuclei and their distinct overlap with the nuclear space, as defined by DAPI (Fig. 1). By contrast, minimum overlap with the cytoskeleton was detected. These results were confirmed on several other immortal cell lines (not shown). Hence, G4 DNA structures appear abundant in cancer cell nuclei and are readily detected by structure-specific antibodies.

Figure 1. G4 DNA structures are readily detected in cell nuclei.

Confocal microscopy of 293T, HAP1 and Hela cells stained with DAPI (blue) for nuclear DNA, a G4 DNA-structure specific antibody (red) and with Phalloidin for cytoplasmic cytoskeleton (green) display nuclear colocalization of G4 DNA structural foci with chromosomal DNA.

The role of G4 DNA structures in eliciting chromosomal rearrangements has been reported (Bacolla et al. 2016, Georgakopoulos-Soares et al. 2018); however, it has remained unclear whether translocations are stimulated by specific G4 elements throughout the human genome. The COSMIC database contains the largest collection of genomic rearrangements in cancer genomes resolved at bp accuracy; from this collection we obtained a set of 124,918 translocation breakpoints mapped to hg38, mostly from complex rearrangements involving two or more chromosomes. We excluded identical breakpoint positions, which were often mapped to the same patient sample, to yield a set of 97,691 unique genomic coordinates that may represent, or are close to, original genomic sites of strand break that occurred during cancer development. Separately, we determined the location and number of G4 DNA-forming sequences in hg38, which amounted to a total of 358,605 (chromosome Y excluded) covering ~13.4 million bases.

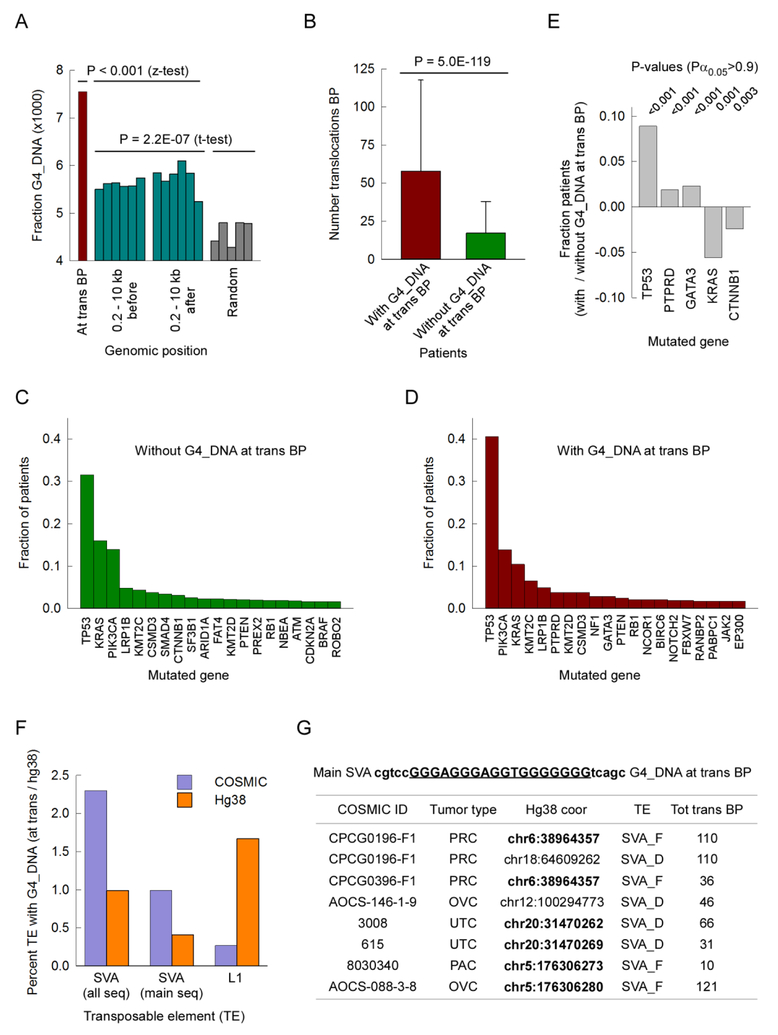

To assess if translocations occurred at G4 DNA-forming sequences more often than expected by chance, we mapped the number of breakpoints located within G4 DNA-forming repeats extended by 5 bp on either side. This mapping constrain is stringent because it assumes that a G4 DNA structure directly caused a chromosomal break. There were 738/97,691 such breakpoint positions, or 7.55 × 10−3 (Fig. 2A). We compared this result with two types of controls. In the first, we selected genomic coordinates located 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0 and 10kb on either side of the 738 true sites, excluded the positions near unsequenced gaps (with N) in hg38, and assessed how many of the non-gap-containing positions were close to G4 DNA-forming sequences. This yielded an average of 5.68 ± 0.21 × 10−3 (n=10) significantly lower than at the real translocation breakpoints (Fig 2A). In the second, we created five sets of 124,918 non-gap-containing random positions; on average, 4.62 ± 0.25 × 10−3 (n=5) of these were within G4 DNA-forming repeats (Fig. 2A), less than both at translocations breakpoints and at their neighboring genomic environment. In conclusion, our analysis shows that translocation breakpoints in cancer occur at G4 DNA-forming repeats more often than expected by chance alone.

Figure 2. G4 DNA elicits translocations in cancer genomes.

Panel A, plot of fraction of translocation breakpoints or control genomic positions (y-axis) occurring within 5 bp of hg38 genomic coordinates mapping G4 DNA-forming sequences (x-axis). Brown, translocation breakpoints in cancer genomes. Green, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0 and 10.0 kb before (left) and after (right) cancer translocation breakpoints. Gray, random genomic coordinates. Panel B, number of translocation breakpoints (mean ± SD) plotted for patients with (brown) and without (green) breakpoints at G4 DNA-forming sequences. Panels C and D, bar graphs of fraction of patients without (panel C) or with (panel D) translocation breakpoints at G4 DNA-forming sequences harboring pathologic mutations in the top 20 cancer-mutated genes. Panel E, net fraction of cancer patients with translocation breakpoints at G4 DNA-forming sequences harboring pathologic mutations in the top 10 most mutated genes; only hits with a Pα0.05 > 0.8 were recorded. Panel F, bar graph of percent transposable elements (TE) harboring G4 DNA-forming sequences in hg38 (orange) and at cancer translocation breakpoints (blue); all seq, all G4 DNA-forming sequences at SVA elements; main seq, most common G4 DNA-forming sequence at SVA retrotransposons (see Panel G). Panel G, list of most common G4 DNA-forming sequence at SVA elements (top); COSMIC ID, COSMIC tumor identification number; Tumor type, PRC, prostate cancer; OVC, ovarian cancer; UTC, uterine cancer; PAC, pancreatic cancer; Hg38 coor, genomic coordinate of translocation breakpoint within G4 DNA-forming sequence; TE, SVA lineage; Tot trans BP, total number of translocation breakpoints in the tumor sample.

3.1.2. Patients with translocations at G4 DNA carry frequent pathologic mutations in p53

Next, we asked whether patients with translocation breakpoints at G4 DNA-forming sequences could be distinguished from those without such a characteristic based on well-defined genetic alterations. First, we assessed the genome-wide load of translocations in each patient; we found that the group of patients with G4-associated breakpoints carried more translocations than the group of patients without G4-associated breakpoints (57.9 ± 59.7 vs. 17.3 ± 20.7; Fig. 2B), although the frequency of breakpoints at G4 DNA-forming repeats did not directly correlate with total translocations. Second, even though tumor samples with and without G4-associated breakpoints carried pathologic mutations in cancer-related genes, such as TP53, KRAS, PIK3CA, etc. (Figs 2C and D), samples with G4-containing breakpoints displayed a greater frequency of mutations at TP53, PTPRD and GATA3 than the alternate group. By contrast, the likelihood of harboring pathologic mutations at KRAS and CTNNB1 was significantly reduced (Fig. 3E), in accordance with the expectation that mutations in the TP53, RTK/RAS and Wnt pathways are mutually exclusive (Sanchez-Vega et al. 2018). We conclude that strand breaks at or near G4 DNA-forming sequences occur generally in tumors with high genetic instability, which is promoted in part by mutations in tumor suppressor genes, such as TP53.

Figure 3. Gene expression profiles correlate with cancer somatic mutations.

Panel A, Plot of regression coefficients (R, x axis) vs. P-values (y axis) for correlations between gene expression (all genes) and somatic mutations for patients with CHOL (black) or BRCA (red). Panel B, S-plots of P-values for the correlations between gene expression (all genes) and somatic mutations for 32 TCGA datasets. Panel C, list of top 10 genes whose mRNA levels (expression) were most strongly correlated with somatic mutations. GO term, selected gene ontology term from the human gene database GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org); Corr, P-value, P-values from panel B; KM P-value, P-value for the Kaplan-Meier plot; COSMIC CGC, whether or not the gene is listed as cancer-promoting gene in the COSMIC cancer gene census. Panel D, Kaplan-Meier survival curves for LUAD patients with low (red) gene expression for PIGR and SPATA18 relative to LUAD patients (blue) with the other 3 combinations (high PIGR high SPATA18; low PIGR high SPATA18; high PIGR low SPATA18). Panel E, box plot of mRNA levels (y axis) in the tumor (blue) and normal (red) samples for the 10 genes with the strongest positive correlations between gene expression and somatic mutations for patients with LUAD. ***, P-value <2 × 10−16. Panel F, number of tumor types (y axis) in which gene expression for a given gene (x axis) was higher in the tumor than in matched normal control tissues (green, 15 total tumor types tested) and the number of instances (orange) in which the P-value for the difference was <2 × 10−16.

3.1.3. SVA transposable elements elicit translocations

Two classes of human non-LTR retrotransposons, LINE1 and Composite, contain family members harboring G4 DNA-forming sequences, including L1PAs (Sahakyan et al. 2017) and SVA elements (Lexa et al. 2014). Because these elements are abundant in the human genome they provide the highest source of G4 DNA-structures along with telomeric sequences (Bhattacharjee et al. 2017, Kejnovsky et al. 2015, Lancrey et al. 2018). We found that the most abundant core G4 DNA-forming sequence mapping to SVA elements was “gggagggaggtggggggg”, present in variable number of copies in the VNTR regions of these elements, which we found to total 3,486 copies in hg38. Seventeen out of 738 translocation breakpoints coinciding with G4 DNA-forming sequences were located at this sequence in SVA_D, SVA_E and SVA_F elements, as classified by repeatMasker (2.3%, Fig. 2F). In hg38 the combined length of the SVA sequence occupied 0.99% of the total bases covered by all G4 DNA-forming sequences (132,779 out of 13,442,760), a percentage matching that of SVA G4-associated tracts relative to the number of G4 tracts genome-wide (0.97; 3,486 out of 358,605) (Fig.2F). Because the core “gggagggaggtggggggg” sequence could occasionally be found outside of SVA regions, we repeated our analysis to breakpoints mapping within “cgtccgggagggaggtgggggggtcagc” (1,964 tracts, 56% of all core sequences), which by including 5 additional bases on either side of the core motif rendered the target sequence SVA-specific. There were 7/738 instances (0.95%) of translocations breakpoints occurring within the extended target sequence, whereas the genome-wide number of such targets was 0.4 – 0.5% of the total number of G4 DNA-forming sequences (Fig. 2F) (54,852/13,442,760*100 in terms of bases and 1,964/358,605*100 in terms of tracts). Thus, translocations breakpoints occur at SVA elements twice more frequently than we would expect by chance.

The most common G4 DNA-forming sequence, totaling 6,675 instances and accounting for ~1.6% of the total G4 tracts genome-wide, was “gggtggggggaggggggaggg”, which characterizes several families of L1 retrotransposons, particularly L1PA2, L1PA3 and L1PA4 (Sahakyan et al. 2017). Surprisingly, only 2/738 (0.27%) translocation breakpoints were found to coincide within the L1-specific G4 sequence (Fig. 2F), suggesting either a hierarchy of susceptibility to strand-break or difficulties in mapping breakpoints at these repetitive DNA elements from whole genome sequencing.

Concerning the 7 translocation breakpoint-positions at SVA elements, these occurred in only 5 distinct units. Two translocation breakpoints were mapped to the same SVA_F, and indeed to the same coordinate on chromosome 6 (hence counted only once in the 738-set) in two separate prostate adenocarcinoma samples carrying a total of 110 and 36 breakpoints, respectively. Two rearrangements involved the same SVA_D element on chromosome 20 in two bladder papillary transitional cell carcinoma samples (66 and 31 breakpoints, respectively). Two breakpoints were found in a third SVA_F element on chromosome 5 in a case of pancreatic ductal carcinoma with only 10 translocation breakpoints, and in a case of ovarian mixed adenosquamous carcinoma with as many as 121 translocation junctions (Fig. 2G). The remaining two translocations occurred at two separate SVA_D elements, one on chromosome 12 and the other on chromosome 18. In conclusion, translocation breakpoints are more likely to be found at G4 DNA located in SVA elements than in L1 transposons; furthermore, it is possible that a subset of SVA elements in the human genome might be particularly unstable, yielding recurrent strand breaks in cancer.

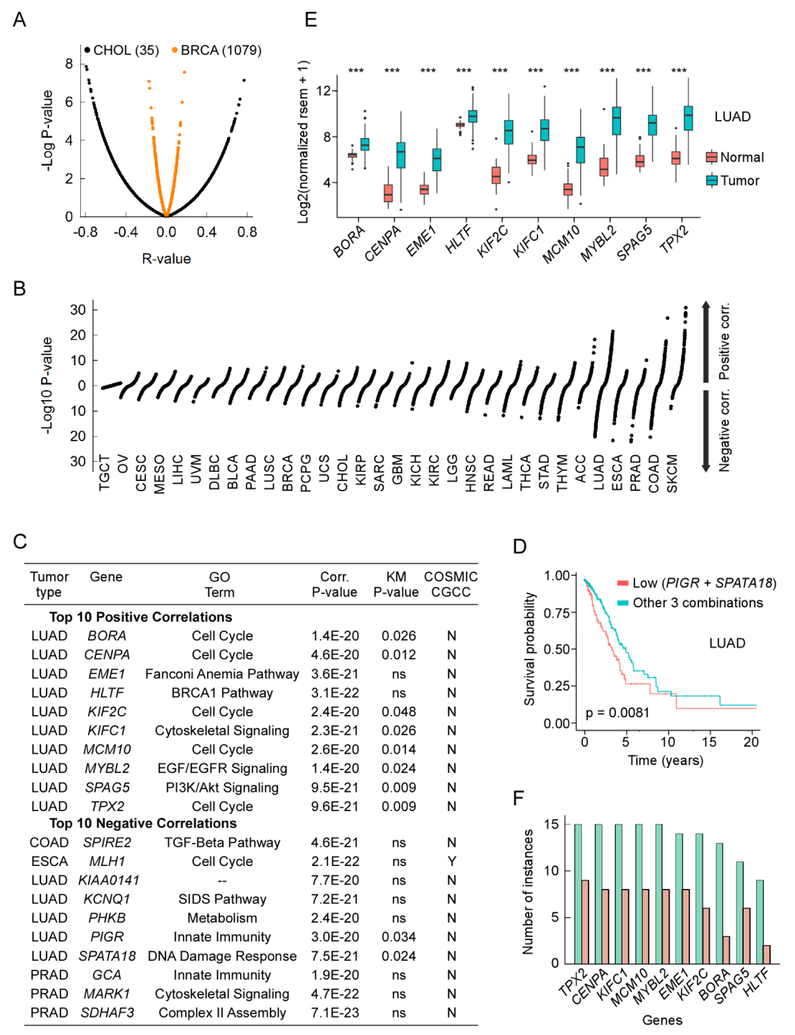

3.2. Gene expression profiles correlate with cancer somatic mutations

3.2.1. Correlation between gene expression and somatic mutations is tumor type specific

Recognizing that G4 DNA likely impacts transcription, we employed a separate set of analyses to assess the extent to which the cellular transcriptome and its regulation are associated with mutation loads in cancer genomes. To this end we analyzed the genome-wide gene expression landscape and whole exome single base substitutions and small indels from TCGA. For each gene and tumor type we computed the regression coefficient R and the associated P-value, which normalized the data from the dependence of R on the total number of observations (Fig. 3A). Thus, an S-plot of all P-values allowed for a direct comparison across all tumors, which revealed a strong variability on tissue-dependent origin in the extent to which gene expression correlates with mutation loads. At the extremes, TGCT displayed minimum P-values (≥0.0035), whereas SKCM exhibited the strongest positive correlations (P-values up to 1 × 10−31), and LUAD covered a continuum wide range of correlations, both in the positive and negative ranges (P-values up to ~ 10−22, Fig. 3B).

3.2.2. The top correlated genes are associated with tumorigenesis

We examined in detail the strongest correlations between expression and mutation by selecting the top 10 positive correlations. For SKCM all positive correlations originated from genes expressed at low levels; indeed, all genes with P-values <1 × 10−5 (105 total) were weakly expressed (mean ± SD 0.15 ± 0.19 log2(normalized rsem + 1)). After excluding the genes with an average expression level <1.0, the top 10 best positive correlations were found in LUAD (Fig. 3C). These included 5 genes associated with the Gene Ontology term “Cell cycle” (BORA, CENPA, KIF2C, MCM10 and TPX2), EME1 involved in the Fanconi anemia pathway, HLTF associated with the BRCA1 pathway and KIFC1, MYBL2 and SPAG5, belonging to the cytoskeletal, EGF/EGFR and PI3K/Akt cell signaling pathways, respectively. Notably, none of these 10 genes was listed as a cancer gene in the COSMIC cancer gene census.

To assess if expression of these 10 genes correlates with clinical outcome in LUAD, we applied the Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimator to patients with high (above average) and low (at or below average) gene expression levels; for 8 genes, patients with high expression performed worse that those with low expression (Fig. 3C). Also, expression levels for all 10 genes were higher in the tumors than in the matched control samples in LUAD (Fig. 3D), with all P-values exceeding <2 × 10−16, the lowest limit afforded by the KM software used. We extended the tumor/normal comparison of these 10 genes to all other tumor types for which at least 10 normal samples were available (15 including LUAD). In all cases TPX2, CENPA, KIFC1, MCM10 and MYBL2 were overexpressed in the tumor, EME1 and KIF2C were overexpressed in 14/15 tumors, BORA in 13/15, SPAG5 in 11/15 and HLTF in 9/15. Thus, the top 10 positively correlated genes are highly expressed in tumors.

Of the 10 top genes most negatively correlated with mutation loads, the strongest association was found for MLH1 in ESCA (Fig. 3C). Mutations in MLH1 or its low expression are known for their role in tumorigenesis (Cancer Genome Atlas 2012), however none of the other 9 genes were listed in the COSMIC cancer gene census. Of note, low expression of PIGR and SPATA2, which are associated with “Innate immunity” and the “DNA damage response”, respectively, was found to be associated with poor prognosis in LUAD (Fig. 3C) and survival probability was further decreased for patients with combined low expression of both PIGR and SPATA18 (Fig. 3F). In summary, the top genes most strongly correlated with mutations loads reveal strong associations between deregulation of gene expression and poor survival in cancer.

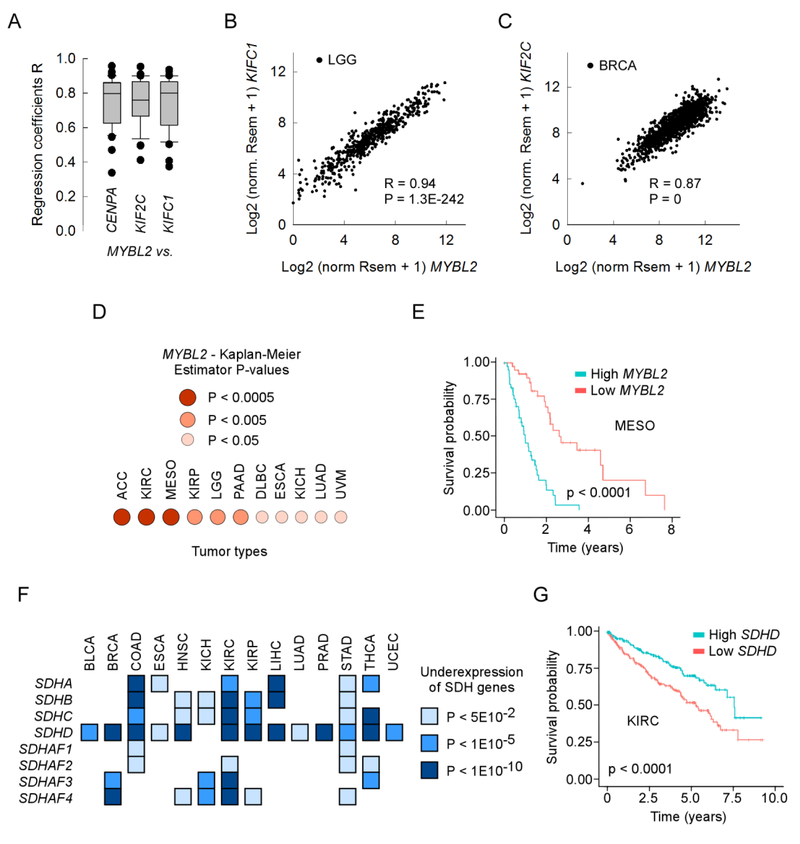

3.2.3. Expression of genes in key pathways is altered across several tumor types

To further explore the involvement of the top genes correlated with mutations in tumorigenesis, we focused on two genes: MYBL2 for the positive correlations and SDHAF3 for the negative correlations. MYBL2 (MYB proto-oncogene like 2) codes for Myb-related protein 2, it is related to the MYB family of transcription factors and plays both a positive and a negative regulatory role in cell cycle progression. Among the genes regulated by MYBL2 are CENPA, KIF2C and KIFC1 (Fig. 3C), which have a role in centromere and microtubule-motor function during mitotic chromosome segregation and bipolar spindle formation. We addressed whether CENPA, KIF2C and KIFC1 were coexpressed with MYBL2, and found that the three genes were coexpressed with MYBL2 in all tumor types, with an average regression coefficient R of ~0.8 (Fig. 4A) and occasional Rs exceeding 0.9 (Fig. 4B). As expected, P-values for the correlations were also highly significant, approaching zero in BRCA, with over 1000 patients (Fig. 4C). We applied the KM estimator analysis for MYBL2 to all tumor types. Poor prognosis was associated with high MYBL2 expression in 11/32 tumors (Fig. 4D), with particularly dismal outcome in patients with ACC, KIRC and MESO (Fig. 4E). Thus, our analysis supports a role for MYBL2 overexpression in carcinogenesis in approximately one third of tumor types.

Figure 4. Altered gene expression in key pathways decreases patient survival.

Panel A, box plot of the correlation coefficient R for the coexpression of MYBL2 vs. CENPA, KIF2C or KIFC1 in patients for each of the 32 TCGA tumor types. Panels B and C, line plots for the normalized Rsem gene expression values for MYBL2 vs. KIFC1 in LGG patients (panel B) and vs. KIF2C in BRCA patients (panel C). R, regression coefficient; P, P-value. Panel D, list of tumor types with worse survival for high MYBL2 gene expression levels and P-values for the respective Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Panel E, Kaplan-Meier survival curves for MESO patients with low (red) and high (blue) gene expression levels for MYBL2. Panel F, list of tumor types in which expression of the succinate dehydrogenase complex genes was lower in the tumor than in the matched control tissues and the corresponding P-values. Panel G, Kaplan-Meier survival curves for KIRC patients with low (red) and high (blue) SDHD gene expression.

SDHAF3 (succinate dehydrogenase complex assembly factor 3) is defined as playing “an essential role in the assembly of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH). SDH is an enzyme complex (also referred to as respiratory complex II) that is a component of both the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and the mitochondrial electron transport chain. SDH couples the oxidation of succinate to fumarate with the reduction of ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) to ubiquinol. SDHAF3 promotes maturation of the iron-sulfur protein subunit SDHB of the SDH catalytic dimer, protecting it from the deleterious effects of oxidants” (https://www.genecards.org/). The SDH complex comprises four subunits (SDHA-D), which perform catalysis and electron transfer, and 4 accessory proteins, SDHAF1–4. In PRAD, where SDHAF3 displayed the strongest negative correlation between expression and mutation of all tumors, the gene was overexpressed relative to matched controls (not shown); however, SDHD was strongly downregulated. An analysis of gene expression for the 8 SDH genes in the 15 tumor/normal pairs revealed that, with the exception of LUSC, at least one SDH gene subunit (most often SDHD) was downregulated in all tumors, often dramatically (P <1 × 10−10) (Fig. 4F). In addition, in KIRC, where 5/8 SDH genes were strongly repressed, the KM estimator predicted worse clinical outcome in subjects with low SDHD. Thus, our gene expression/mutations relationships provide support for SDH deficiency as a widespread alteration in cancer.

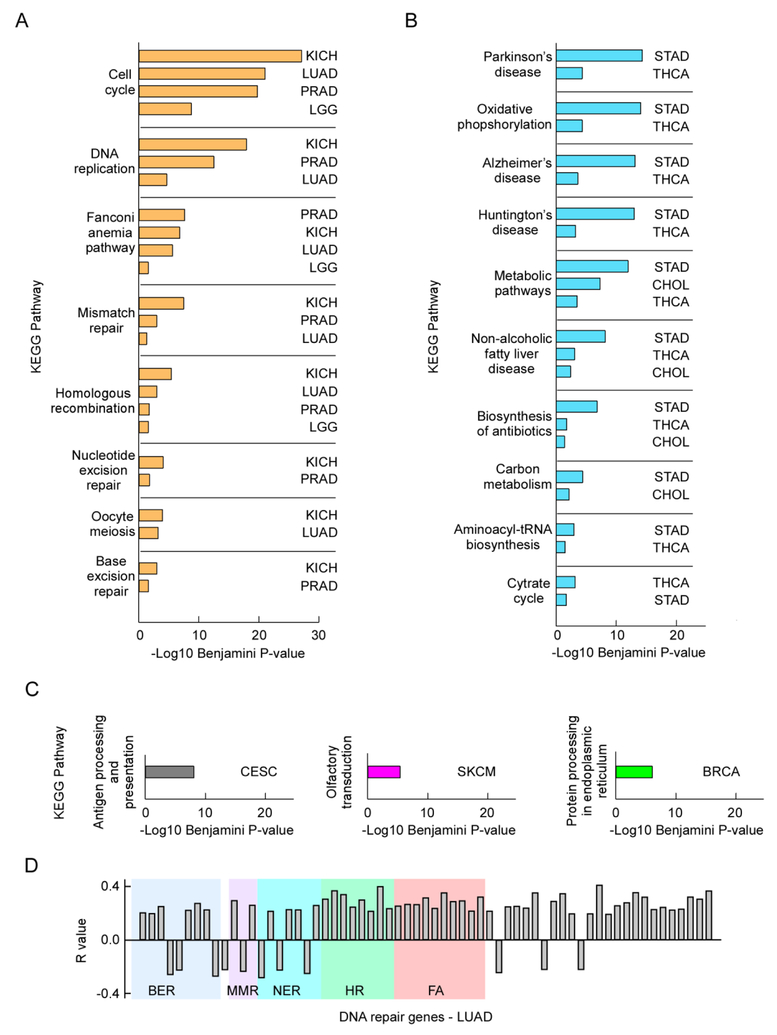

3.2.4. Mutation loads are associated with defects in DNA repair

Having established the validity of our analyses in uncovering genes whose deregulation seem to predict poor clinical outcome, we then conducted a systematic assessment of gene enrichment for a pool of genes with strong correlations in each tumor type. We chose as a threshold for the number of genes those whose expression was positively correlated with mutations, in LUAD, with a P-value <1 × 10−10, which totaled 270. We then selected the same number of genes for the other tumor types. We conducted a gene enrichment analysis focused on KEGG terms, which are suited for identifying cellular pathways. Three tumor types, KICH, LUAD and PRAD shared commonly enriched gene categories, including “Cell cycle”, “DNA replication” and major DNA repair pathways, including the “Fanconi anemia pathway”, “Mismatch repair” (MMR), “Homologous recombination” (HR), “Nucleotide excision repair” (NER) and “Base excision repair” (BER) (Fig. 5A). A fourth tumor type (LGG) shared these pathways with reduced strength. A second set of tumors (STAD, THCA and CHOL) also shared distinct terms, such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s diseases, and “Oxidative phosphorylation”, all of which contained genes coding for complexes I – V of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (Fig. 5B). For STAD these genes were: NDUFB10, NDUFA8, NDUFA9, NDUFA6, NDUFB9, NDUFAB1, NDUFS7, NDUFV1, NDUFS3, NDUFS2 for complex I, SDHB, SDHD for complex II, UQCRC2, UQCRC1, CYC1 for complex III, COX4I1, COX5A for complex IV and V ATP5D, ATP5B, ATP5F1, ATP5G3, ATP5O, ATP5A1 for complex V.

Figure 5. Mutations are linked to defects in DNA repair gene expression.

Panels A - C, bar graphs of P-values adjusted for multiple testing (Benjamini correction) for genes enriched in KEGG pathways from the pool of top 270 genes (for each tumor type) that displayed positive correlation between mRNA levels (expression) and cancer somatic mutations. Panels A and B group tumors that displayed common terms, whereas panel C shows singletons of tumor-specific KEGG pathway enrichment. Panel D, graph of regression coefficients (y axis) for DNA repair genes (x axis) displaying P-values <1 × 10−5 for the correlations between gene expression and cancer mutation loads in patients with LUAD; shaded areas highlight genes in the same pathway; BER, base excision repair; MMR, mismatch repair; NER, nucleotide excision repair; HR, homologous recombination; FA, Fanconi anemia.

Few singleton tumors were also uncovered, with highly enriched tumor-specific terms. These included CESC, where human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes of the “Antigen processing and presentation” term populated 26 KEGG pathway terms; SKCM, where the correlations between weakly expressed genes and mutations mentioned in section 3.2.2 were enriched in olfactory receptor genes; and BRCA, enriched in genes associated with the “Protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum” term (Fig 5C). We also conducted the gene enrichment analysis for the 270 genes (in each tumor type), whose expression was most negatively correlated with mutations, but did not find any enriched term. Similarly, only one term with a Benjamini-corrected P-value of 0.02 was found when 270 genes with no significant correlation with mutations were selected for each tumor. Therefore, our correlation analysis of gene expression versus mutation loads identified pathways that are commonly altered in different types of cancer.

We found it counterintuitive that for some enriched gene pathways, such as DNA repair, there were positive correlations between gene expression and mutations, since we expected weak DNA repair to increase mutations. In LUAD, although not in KICH and PRAD, the main pathways for the repair of base mismatch and base lesions, i.e. BER, MMR and NER, contained at least one gene that displayed negative correlation between expression and mutations. These included NEIL1 (R = −0.26, P = 3.0 × 10−9), NEIL2 (R = −0.22, P = 2.6 × 10−7) and PARP3 (R = −0.27, P = 4.9 × 10−10) for the BER pathway, MSH3 (R = −0.23, P = 1.2 × 10−7) for the MMR pathway, and XPC (R = −0.28, P = 8.7 × 10−11), DDB2 (R = −0.22, P = 4.1 × 10−7) and CCNH (R = −0.26, P = 7.4 × 10–9) for the NER/TFIIH pathway. In addition, ALKBH3 (R = −0.22, P = 4.0×10−7) for alkylation damage reversal, RRM2B (R = −0.24, P = 2.7 × 10−8), which supplies dNTPs during DNA repair synthesis, POLK (R = −0.22, P = 3.9 × 10−7) for translesion DNA synthesis and UBE2B (R = −0.22, P = 4.9 × 10−7), involved in ubiquitination of PCNA also displayed negative correlations with mutational loads (Fig. 5D). On the other hand, no negative correlations were observed for HR and the Fanconi anemia pathways. Thus, it is possible that in LUAD the activation of DNA repair pathways reflects a response to an accumulation of unrepaired DNA damage.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study we addressed the contribution of two distinct mechanisms to the induction of somatic mutations in cancer: the formation of G4 DNA structures and tumor-specific changes in gene transcriptional profiles. Translocation breakpoints were enriched at sequences with the potential to form G4 DNA structures in tumor samples that were characterized by elevated genetic instability and frequent mutations in tumor suppressor genes, such as TP53. SVA and L1 elements contribute thousands of identical G4 DNA-forming motifs in the genome, although translocations were readily found at motifs present in the former but not in the latter classes of retrotransposons. Transcription of hundreds of genes correlated strongly with somatic mutation loads in some cancer types but not in others. Most genes with the strongest correlations were not listed as “cancer-genes”, although their expression shows strong predictive power of survival in Kaplan-Meier plots. Genes whose expression is positively correlated with mutations were enriched in selected KEGG terms in more than one cancer type, which provides a platform for addressing the contribution of specific pathways to somatic mutation in cancer.

4.1. G4 DNA induces translocations

We assigned the puncta detected in cell nuclei to G4 DNA structures bound to the 1H6 murine monoclonal antibody, which is thought to recognize G4 structures raised from DNA oligonucleotides assembling into parallel-stranded G4 conformations (Henderson et al. 2014). This antibody shows selectivity for inter- and intramolecular structures mostly localized to heterochromatin (Hoffmann et al. 2016); however, the use of other probes supports G4 structure-formation throughout nucleoli (Zhang et al. 2018), in mitochondrial DNA (Huang et al. 2015) and in the cytoplasm by RNA (Biffi et al. 2014, Laguerre et al. 2015). Hence, given that >350,000 G4 DNA-forming repeats are present in the human genome and that ~80% of the genome is transcribed (Consortium 2012), the potential for G4 structures comprising DNA, RNA, and perhaps DNA:RNA hybrids in cells is remarkably high and therefore constitutes sites where DNA structure is likely to impact outcomes to cellular stress in cancer.

The twofold increase in translocation breakpoints at G4 DNA-forming sequences found here is likely a lower bound since deletion or addition of nucleotides that often accompany DSB repair may have moved a number of G4 DNA-associated breakpoints outside of the detection range. Nevertheless, our estimates are in line with determinations of mutations at non-B DNA-forming motifs in cancer genomes (Georgakopoulos-Soares et al. 2018) and strengthens the concept, both from genome-wide (Bacolla et al. 2016, Zhao et al. 2018) and targeted (Javadekar et al. 2018, Pannunzio and Lieber 2018, Smida et al. 2017) studies, that non-B DNA structures contribute to mutagenesis, both in cancer and in genetic disease (Kamat et al. 2016).

The prevalence of G4-associated translocation breakpoints with tumor samples carrying extensive genomic alterations is consistent with reports that TP53 mutant tumors are associated with high rates of genomic instability (reviewed in (Hanel and Moll 2012)). TP53 mutants have been reported to sequester DNA repair factors (Hanel and Moll 2012), such as MRE11, away from double-strand breaks and at stalled replication forks (Roy et al. 2018), leading to an accumulation of translocations (Buis et al. 2008, Syed and Tainer 2018). Thus, it is likely that TP53-induced instability is related to defects in homologous recombination repair and balancing responses at stalled replication forks including recruitment of the MRE11 nuclease, which initiates break and fork processing (Roy et al. 2018, Schlacher et al. 2011, Shibata et al. 2014). Changes in gene expression, which we show here are extensive and impact cancer mutagenesis, are also likely to influence G4 DNA structure-induced genetic instability (Day et al. 2017). We are also learning how replication and repair proteins, such as FEN1, can act in trans to greatly impact mutations so molecular mechanisms are expected to be key to improve predictions (Tsutakawa et al. 2017). With this in mind, it will be important to elucidate the roles of the other 4 mutated genes (PTPRD, GATA3, KRAS and CTNNB1) in the susceptibility to incur strand breaks at G4 DNA-forming sequences.

As L1 and SVA transposable elements contain G4 DNA-forming sequences (Kejnovsky et al. 2015, Lexa et al. 2014, Sahakyan et al. 2017) that occur in the human genome in the thousands, they are key candidates for G4-dependent translocations. It was surprising to find that translocations breakpoints were enriched at SVA but not at L1 sites, given: 1) that the number of L1PA elements is twice that of SVAs; 2) that retrotransposition and transcription occurs more robustly for L1PA than for SVA elements (Lee et al. 2012) despite the former being older elements, 7.6 – 18.0 Myrs for L1PA3–5 elements (Khan et al. 2006) versus 3.8 – 9.5 Myrs for SVA_D-F (Wang et al. 2005); and 3) that SVAs rely on ORF2p, and perhaps ORF1p, for transcription, both of which are provided by L1 elements (Raiz et al. 2012). Indeed, deletion of the G4-forming repeats, which act as entry points for transcription, is detrimental to SVA retrotransposition (Raiz et al. 2012). Hence, our findings expand the repertoire of genomic alterations attributed to SVA elements, which has included germline rearrangements (Hancks and Kazazian 2016, Vogt et al. 2014) and chromosomal breakages leading to chromothripsis (Hancks 2018). Thus, it is possible hat some SVAs may be particularly active and a source of recurrent strand breaks, so methods to bridge from macromolecular complexes to imaging may prove important for a molecular understanding (Brosey et al. 2017).

4.2. Gene expression and somatic mutations

Despite the realization that correlation does not necessarily imply causation, we undertook a comprehensive analysis of gene expression and its relationships to mutational loads in cancer genomes with the goal of finding common trends across tumor types of possible predictive value.

4.2.1. Negative correlations

The extent to which many genes displayed strong correlation between their expression and mutational loads was surprising, which prompted us to focus on some of the top correlated genes to better elucidate some of the potential causative relationships. The second strongest anticorrelation was that of MLH1 in ESCA. MLH1 mediates protein-protein interactions during mismatch recognition, strand discrimination, and strand removal. In colon and rectal cancers hypermutation has been linked in part to MLH1 hypermethylation (Cancer Genome Atlas 2012), and in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma MLH1 promoter methylation correlates with weak expression and poor survival (Chen et al. 2016). Our results strengthen the role of low MLH1 mRNA levels in elevating mutation loads. Methods to examine MLH1 activities in the context of its multiple partners, such as developed for X-ray scattering from gold nanocrystals and single molecule forceps (Wang et al. 2018), will be critical to develop a predictive mechanistic understanding for its impacts for cancer biology (Hura et al. 2013, Rambo and Tainer 2010). In fact, X-ray scattering may prove to be an enabling method for defining the many solution complexes and conformations (Rambo and Tainer 2013) underlying outcomes to replication stress.

Of the 10 top anticorrelations, low expression of PIGR and SPATA18 in LUAD was associated with poor survival. The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (the PIGR gene product) pIgR plays an important role in protecting small airways of the lung from airborne antigens and microorganisms (Richmond et al. 2016); PIGR−/− mice develop chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COMP)-like pathology with age and persistent activation of innate immune response to the lung microbiome (Richmond et al. 2016). Loss of PIGR is an early event in lung tumorigenesis (Ocak et al. 2012), and it is plausible that the association of low PIGR with high mutation rates we observe reflects a role for the ensuing inflammation in mutagenesis, in part through the release of ROS and reactive nitrogen intermediates (Grivennikov et al. 2010). The product of SPATA18, usually referred to as Mieap, is a target of TP53 and has a role in mitochondria. In lung adenocarcinoma Mieap evidently cooperates with BNIP3 and an activated-truncated form of VDAC1 to achieve HIF-dependent cellular adaptation and fitness to hypoxia conditions through mitochondrial hyperfusion (Brahimi-Horn et al. 2015), as well as in mitochondrial regeneration that entail reduction of ROS buildup (Miyamoto et al. 2011, Nakamura et al. 2012). Thus, our analyses support the concept that SPATA18 downregulation would increase mutation loads through the Warburg effect.

4.2.2. Positive correlations

The clearest insight implicating functional connections between gene expression and mutation was the finding that the top 10 strongest co-correlations identified genes highly overexpressed in most, if not all, tumor types, with high expression being linked to poor survival. The association of these genes with the cell cycle is supported by prior analyses of TCGA data sets (Buccitelli et al. 2017, Peng et al. 2015), and it in line with the idea that tumorigenesis is sustained by hyperactivity in cell growth and cell division. The transcription factor V-Myb avian myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog-like 2 (the product of MYBL2) plays a critical role in cell cycle progression, cell survival and cell proliferations (Musa et al. 2017), by activating many genes including CENPA, KIF2C and KIFC1. Our survival analyses add to the number of tumor types in which MYBL2 overexpression has been associated with decreased survival (reviewed in (Musa et al. 2017)). A causal association between MYBL2 expression and mutation loads has recently been reported, and involves transactivation of the APOBEC3B gene (Chou et al. 2017) whose product (apolipoprotein B mRNA cytosine deaminase, A3B) generates ectopic C>U>T transitions and genomic hypermutation when overproduced (Burns et al. 2013).

The strong correlation of the SDH accessory factor SDHAF3 with mutations was of particular interest since a germline c.157T>C (p.Phe53Leu) substitution in this gene was recently associated with increased prevalence of familiar and sporadic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma, which are characteristic of SDH-deficiency (Dwight et al. 2017). Mechanistically, SDHAF3 plays an indispensable role, together with the other 3 accessory factors (SDHAF1,2,4), in the maturation of the SDH complex, by promoting the insertion of Fe-S clusters into the SDHB subunit and by protecting the SDH complex from superoxide-related oxidative damage (Dwight et al. 2017, Na et al. 2014). The fundamental importance of Fe-S clusters and control of superoxide support the observed connections of the SDHB subunit with mutational load (Fuss et al. 2015, Perry et al. 2010). Under low concentrations of SDHAF3, or any other SDH component, SDH activity is expected to decrease, resulting in high levels of ROS, the Warburg effect (Tseng et al. 2018) and an accumulation of succinate, a competitive inhibitor of a large number of α-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes (Xiao et al. 2012). Succinate buildup would then lead to activation of the HIF-1α pathway (Laurenti and Tennant 2016), a hypermethylator phenotype (Aldera and Govender 2018), and a suppression of the homologous recombination DNA repair pathway (Sulkowski et al. 2018). Thus, anticorrelation between SDHAF3 expression and mutations may stem from SDH deficiency.

Our clustering results are intriguing, both from a tumor classification perspective and from a mechanistic standpoint. The clustering encompassing KICH, LUAD, PRAD and LGG is centered on cell cycle, DNA replication and DNA repair genes, and the positive correlations with mutations likely arise from replication stress (Hamperl and Cimprich 2016, Hills and Diffley 2014, Kotsantis et al. 2016, Macheret and Halazonetis 2015), excessive DNA damage (such as A3B activation) and its escape from repair. The second cluster comprising STAD, THCA and CHOL revolves on genes coding for complexes I – V of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. One electron oxidation and charge transfer reactions in DNA are suggested to promote base substitutions (Bacolla et al. 2013, Suarez-Villagran et al. 2018, Temiz et al. 2015). Thus, we propose that the association of mitochondrial gene expression with mutations likely stems from direct damage to DNA by increased ROS and other oxidants. Thus, our analysis implicates cell cycle/DNA repair and mitochondrial dysfunction as two main branches through which gene expression is linked to somatic mutation in cancer.

The group of genes enriched in singletons (UCEC, SKCM and BRCA) is also of high interest. The ectopic expression and upregulation of olfactory receptors in melanoma (SKCM) is a potential source of malignant transformation (Gelis et al. 2017, Ranzani et al. 2017), and it will be useful to assess their role in mutagenesis. Likewise, it will be instructive to assess the relationships between HLA gene expression and mutation loads in CESC, where a role for HPV infection is well established (Brady et al. 2000). Finally, BRCA displayed enrichment in genes involved in the unfolded protein response (UPR) pathway. UPR aims at restoring protein integrity by activating chaperon-assisted protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum (McGrath et al. 2018, Minakshi et al. 2017, Ricciardiello et al. 2018), and our data support its activation and relevance in breast cancer.

5. SYNOPSIS AND PERSPECTIVE

We sought to computationally examine the impact of non-B DNA structure typified by G4 DNA sequences, which likely impact transcription and replication, and of transcription directly in genome instability and cancer. We found that G4 DNA-forming sequences are enriched twofold at translocation breakpoints, strengthening the view that G4 DNA structures contribute to genomic instability in cancer; many such structures are likely to originate from L1 and SVA retrotransposons and contribute to instability. Mutations in TP53 increase the chance of G4 DNA-induced translocations, possibly through defects in homologous recombination following replication fork stalling at G4 DNA. These observations point to non-B DNA as sites of increased mutation risk that are protected in normal cells by DNA damage responses, which can be defective in cancer cells. Transcriptome analyses identify two distinct branches though which alterations in gene expression may lead to an accumulation of single base substitutions in cancer: 1) activation of cell cycle/DNA repair; and 2) loss of homeostatic control of mitochondrial respiration. It will be important to determine the degree and basis by which these branches are connected, such as is being elucidated for the apoptosis inducing factor (AIF), which is important for assembly of functional mitochondrial complexes and for cell death promoted by PARP1 depletion of NADH unbalanced from its removal by the gylcohydrolase PARG in response to DNA damage (Brosey et al. 2016). Induction of the cell cycle/DNA repair operates preferentially in tumors of the kidney, lung, prostate and brain/spinal cord, whereas mitochondrial dysfunction is more prevalent in tumors of the stomach, thyroid and bile ducts. Tumor-specific alterations in gene expression associated with mutation loads also include the ectopic expression of olfactory receptor genes in skin cancer, exacerbation of the ER unfolded protein response in breast cancer and altered HLA gene expression in cervical cancer. We anticipate that future efforts will elucidate the recognition and processing of G4 and other non-B DNA structures by cellular enzymes with the aim at reducing their mutagenicity. The picture emerging from the gene expression/mutation correlations points to two interesting targets for research. The first is to assess the relations of the MYBL2 axis with DNA repair responses and mutagenesis. The second is to clarify how deregulation of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and its link to the TCA cycle through the SDH complex elicits mutations. Given the prevalence of cervical, skin and breast cancer, it will furthermore be important to assess the role of HLA, olfactory receptor, and chaperon gene expression alterations in mutation loads in these malignancies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Aleem Syed and Dr. Katharina Schlacher for comments and suggestions. This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (B.A, Z.A., J.A.T.), by a Robert A. Welch Chemistry Chair (J.A.T.) and by NIH grants R35CA22043, P01 CA092584, CA117638, and CA200231. This research used the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC), which is supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) grant ACI-1134872, and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by NSF grant ACI-1548562.

ABBREVIATIONS

- COSMIC

Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- GRCh38/hg38

Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 38 (GRCh38/hg38)

- ACC

adrenocortical carcinoma

- BLCA

bladder urothelial carcinoma

- BRCA

breast invasive carcinoma

- CESC

cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma

- CHOL

cholangiocarcinoma

- COAD

colon adenocarcinoma

- DLBC

lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- ESCA

esophageal carcinoma

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- HNSC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- KICH

kidney chromophobe

- KIRC

kidney renal clear cell carcinoma

- KIRP

kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma

- LAML

acute myeloid leukemia

- LGG

brain lower grade glioma

- LIHC

liver hepatocellular carcinoma

- LUAD

lung adenocarcinoma

- LUSC

lung squamous cell carcinoma

- MESO

mesothelioma

- OV

ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma

- PAAD

pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- PCPG

pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma

- PRAD

prostate adenocarcinoma

- READ

rectum adenocarcinoma

- SARC

sarcoma

- SKCM

skin cutaneous melanoma

- STAD

stomach adenocarcinoma

- TGCT

testicular germ cell tumors

- THCA

thyroid carcinoma

- THYM

thymoma

- UCEC

uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma

- UCS

uterine carcinosarcoma

- UVM

uveal melanoma

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Albino Bacolla, Email: abacolla@mdanderson.org.

Zu Ye, Email: zye4@mdanderson.org.

Zamal Ahmed, Email: zahmed@mdanderson.org.

7. REFERENCES

- Aldera AP and Govender D, 2018. Gene of the month: SDH. J. Clin. Pathol 71, 95–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Borresen-Dale AL, Boyault S, Burkhardt B, Butler AP, Caldas C, Davies HR, Desmedt C, Eils R, Eyfjord JE, Foekens JA, Greaves M, Hosoda F, Hutter B, Ilicic T, Imbeaud S, Imielinski M, Jager N, Jones DT, Jones D, Knappskog S, Kool M, Lakhani SR, Lopez-Otin C, Martin S, Munshi NC, Nakamura H, Northcott PA, Pajic M, Papaemmanuil E, Paradiso A, Pearson JV, Puente XS, Raine K, Ramakrishna M, Richardson AL, Richter J, Rosenstiel P, Schlesner M, Schumacher TN, Span PN, Teague JW, Totoki Y, Tutt AN, Valdes-Mas R, van Buuren MM, van ‘t Veer L, Vincent-Salomon A, Waddell N, Yates LR, Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome, I., Consortium, I.B.C., Consortium, I.M.-S., PedBrain, I., Zucman-Rossi J, Futreal PA, McDermott U, Lichter P, Meyerson M, Grimmond SM, Siebert R, Campo E, Shibata T, Pfister SM, Campbell PJ and Stratton MR, 2013. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacolla A, Tainer JA, Vasquez KM and Cooper DN, 2016. Translocation and deletion breakpoints in cancer genomes are associated with potential non-B DNA-forming sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 5673–5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacolla A, Temiz NA, Yi M, Ivanic J, Cer RZ, Donohue DE, Ball EV, Mudunuri US, Wang G, Jain A, Volfovsky N, Luke BT, Stephens RM, Cooper DN, Collins JR and Vasquez KM, 2013. Guanine holes are prominent targets for mutation in cancer and inherited disease. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MH, Tokheim C, Porta-Pardo E, Sengupta S, Bertrand D, Weerasinghe A, Colaprico A, Wendl MC, Kim J, Reardon B, Ng PK, Jeong KJ, Cao S, Wang Z, Gao J, Gao Q, Wang F, Liu EM, Mularoni L, Rubio-Perez C, Nagarajan N, Cortes-Ciriano I, Zhou DC, Liang WW, Hess JM, Yellapantula VD, Tamborero D, Gonzalez-Perez A, Suphavilai C, Ko JY, Khurana E, Park PJ, Van Allen EM, Liang H, Group MCW, Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N., Lawrence MS, Godzik A, Lopez-Bigas N, Stuart J, Wheeler D, Getz G, Chen K, Lazar AJ, Mills GB, Karchin R and Ding L, 2018. Comprehensive characterization of cancer driver genes and mutations. Cell 173, 371–385 e318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee A, Wang Y, Diao J and Price CM, 2017. Dynamic DNA binding, junction recognition and G4 melting activity underlie the telomeric and genome-wide roles of human CST. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 12311–12324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffi G, Di Antonio M, Tannahill D and Balasubramanian S, 2014. Visualization and selective chemical targeting of RNA G-quadruplex structures in the cytoplasm of human cells. Nat. Chem 6, 75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady CS, Bartholomew JS, Burt DJ, Duggan-Keen MF, Glenville S, Telford N, Little AM, Davidson JA, Jimenez P, Ruiz-Cabello F, Garrido F and Stern PL, 2000. Multiple mechanisms underlie HLA dysregulation in cervical cancer. Tissue Antigens 55, 401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahimi-Horn MC, Lacas-Gervais S, Adaixo R, Ilc K, Rouleau M, Notte A, Dieu M, Michiels C, Voeltzel T, Maguer-Satta V, Pelletier J, Ilie M, Hofman P, Manoury B, Schmidt A, Hiller S, Pouyssegur J and Mazure NM, 2015. Local mitochondrial-endolysosomal microfusion cleaves voltage-dependent anion channel 1 to promote survival in hypoxia. Mol. Cell. Biol 35, 1491–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosey CA, Ahmed Z, Lees-Miller SP and Tainer JA, 2017. What combined measurements from structures and imaging tell us about DNA damage responses. Methods Enzymol. 592, 417–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosey CA, Ho C, Long WZ, Singh S, Burnett K, Hura GL, Nix JC, Bowman GR, Ellenberger T and Tainer JA, 2016. Defining NADH-driven allostery regulating apoptosis-inducing factor. Structure 24, 2067–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccitelli C, Salgueiro L, Rowald K, Sotillo R, Mardin BR and Korbel JO, 2017. Pan-cancer analysis distinguishes transcriptional changes of aneuploidy from proliferation. Genome Res. 27, 501–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buis J, Wu Y, Deng Y, Leddon J, Westfield G, Eckersdorff M, Sekiguchi JM, Chang S and Ferguson DO, 2008. Mre11 nuclease activity has essential roles in DNA repair and genomic stability distinct from ATM activation. Cell 135, 85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns MB, Temiz NA and Harris RS, 2013. Evidence for APOBEC3B mutagenesis in multiple human cancers. Nat. Genet 45, 977–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas N, 2012. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 487, 330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae YK, Anker JF, Carneiro BA, Chandra S, Kaplan J, Kalyan A, Santa-Maria CA, Platanias LC and Giles FJ, 2016. Genomic landscape of DNA repair genes in cancer. Oncotarget 7, 23312–23321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Peng H, Huang X, Zhao M, Li Z, Yin N, Wang X, Yu F, Yin B, Yuan Y and Lu Q, 2016. Genome-wide profiling of DNA methylation and gene expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 7, 4507–4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Li C, Peng X, Zhou Z, Weinstein JN, Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. and Liang H, 2018. A pan-cancer analysis of enhancer expression in nearly 9000 patient samples. Cell 173, 386–399 e312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou WC, Chen WT, Hsiung CN, Hu LY, Yu JC, Hsu HM and Shen CY, 2017. B-Myb Induces APOBEC3B Expression Leading to Somatic Mutation in Multiple Cancers. Sci. Rep 7, 44089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium EP, 2012. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day TA, Layer JV, Cleary JP, Guha S, Stevenson KE, Tivey T, Kim S, Schinzel AC, Izzo F, Doench J, Root DE, Hahn WC, Price BD and Weinstock DM, 2017. PARP3 is a promoter of chromosomal rearrangements and limits G4 DNA. Nat. Commun 8, 15110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Bailey MH, Porta-Pardo E, Thorsson V, Colaprico A, Bertrand D, Gibbs DL, Weerasinghe A, Huang KL, Tokheim C, Cortes-Ciriano I, Jayasinghe R, Chen F, Yu L, Sun S, Olsen C, Kim J, Taylor AM, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Suphavilai C, Nagarajan N, Stuart JM, Mills GB, Wyczalkowski MA, Vincent BG, Hutter CM, Zenklusen JC, Hoadley KA, Wendl MC, Shmulevich L, Lazar AJ, Wheeler DA, Getz G and Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N., 2018. Perspective on oncogenic processes at the end of the beginning of cancer genomics. Cell 173, 305–320 e310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight T, Na U, Kim E, Zhu Y, Richardson AL, Robinson BG, Tucker KM, Gill AJ, Benn DE, Clifton-Bligh RJ and Winge DR, 2017. Analysis of SDHAF3 in familial and sporadic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. BMC Cancer 17, 497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes SA, Beare D, Gunasekaran P, Leung K, Bindal N, Boutselakis H, Ding M, Bamford S, Cole C, Ward S, Kok CY, Jia M, De T, Teague JW, Stratton MR, McDermott U and Campbell PJ, 2015. COSMIC: exploring the world’s knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D805–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuss JO, Tsai CL, Ishida JP and Tainer JA, 2015. Emerging critical roles of Fe-S clusters in DNA replication and repair. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1853, 1253–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelis L, Jovancevic N, Bechara FG, Neuhaus EM and Hatt H, 2017. Functional expression of olfactory receptors in human primary melanoma and melanoma metastasis. Exp. Dermatol 26, 569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulos-Soares I, Morganella S, Jain N, Hemberg M and Nik-Zainal S, 2018. Noncanonical secondary structures arising from non-B DNA motifs are determinants of mutagenesis. Genome Res. 28, 1264–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach A, Dimova EY, Petry A, Martinez-Ruiz A, Hernansanz-Agustin P, Rolo AP, Palmeira CM and Kietzmann T, 2015. Reactive oxygen species, nutrition, hypoxia and diseases: Problems solved? Redox Biol. 6, 372–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov SI, Greten FR and Karin M, 2010. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140, 883–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobner SN, Worst BC, Weischenfeldt J, Buchhalter I, Kleinheinz K, Rudneva VA, Johann PD, Balasubramanian GP, Segura-Wang M, Brabetz S, Bender S, Hutter B, Sturm D, Pfaff E, Hubschmann D, Zipprich G, Heinold M, Eils J, Lawerenz C, Erkek S, Lambo S, Waszak S, Blattmann C, Borkhardt A, Kuhlen M, Eggert A, Fulda S, Gessler M, Wegert J, Kappler R, Baumhoer D, Burdach S, Kirschner-Schwabe R, Kontny U, Kulozik AE, Lohmann D, Hettmer S, Eckert C, Bielack S, Nathrath M, Niemeyer C, Richter GH, Schulte J, Siebert R, Westermann F, Molenaar JJ, Vassal G, Witt H, Project IP-S, Project IM-S, Burkhardt B, Kratz CP, Witt O, van Tilburg CM, Kramm CM, Fleischhack G, Dirksen U, Rutkowski S, Fruhwald M, von Hoff K, Wolf S, Klingebiel T, Koscielniak E, Landgraf P, Koster J, Resnick AC, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhou X, Waanders AJ, Zwijnenburg DA, Raman P, Brors B, Weber UD, Northcott PA, Pajtler KW, Kool M, Piro RM, Korbel JO, Schlesner M, Eils R, Jones DTW, Lichter P, Chavez L, Zapatka M and Pfister SM, 2018. The landscape of genomic alterations across childhood cancers. Nature 555, 321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamperl S and Cimprich KA, 2016. Conflict resolution in the genome: How transcription and replication make it work. Cell 167, 1455–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancks DC, 2018. A Role for Retrotransposons in Chromothripsis. Methods Mol. Biol 1769, 169–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancks DC and Kazazian HH Jr., 2016. Roles for retrotransposon insertions in human disease. Mob. DNA 7, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanel W and Moll UM, 2012. Links between mutant p53 and genomic instability. J. Cell. Biochem 113, 433–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel-Hertsch R, Beraldi D, Lensing SV, Marsico G, Zyner K, Parry A, Di Antonio M, Pike J, Kimura H, Narita M, Tannahill D and Balasubramanian S, 2016. G-quadruplex structures mark human regulatory chromatin. Nat. Genet 48, 1267–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleday T, Eshtad S and Nik-Zainal S, 2014. Mechanisms underlying mutational signatures in human cancers. Nat. Rev. Genet 15, 585–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A, Wu Y, Huang YC, Chavez EA, Platt J, Johnson FB, Brosh RM Jr., Sen D and Lansdorp PM, 2014. Detection of G-quadruplex DNA in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 860–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills SA and Diffley JF, 2014. DNA replication and oncogene-induced replicative stress. Curr. Biol 24, R435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann RF, Moshkin YM, Mouton S, Grzeschik NA, Kalicharan RD, Kuipers J, Wolters AH, Nishida K, Romashchenko AV, Postberg J, Lipps H, Berezikov E, Sibon OC, Giepmans BN and Lansdorp PM, 2016. Guanine quadruplex structures localize to heterochromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 152–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WC, Tseng TY, Chen YT, Chang CC, Wang ZF, Wang CL, Hsu TN, Li PT, Chen CT, Lin JJ, Lou PJ and Chang TC, 2015. Direct evidence of mitochondrial G-quadruplex DNA by using fluorescent anti-cancer agents. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 10102–10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hura GL, Tsai CL, Claridge SA, Mendillo ML, Smith JM, Williams GJ, Mastroianni AJ, Alivisatos AP, Putnam CD, Kolodner RD and Tainer JA, 2013. DNA conformations in mismatch repair probed in solution by X-ray scattering from gold nanocrystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 17308–17313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadekar SM, Yadav R and Raghavan SC, 2018. DNA structural basis for fragility at peak III of BCL2 major breakpoint region associated with t(14;18) translocation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj 1862, 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat MA, Bacolla A, Cooper DN and Chuzhanova N, 2016. A Role for Non-B DNA Forming Sequences in Mediating Microlesions Causing Human Inherited Disease. Hum. Mutat 37, 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kejnovsky E, Tokan V and Lexa M, 2015. Transposable elements and G-quadruplexes. Chromosome Res. 23, 615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan H, Smit A and Boissinot S, 2006. Molecular evolution and tempo of amplification of human LINE-1 retrotransposons since the origin of primates. Genome Res. 16, 78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koplev S, Lin K, Dohlman AB and Ma’ayan A, 2018. Integration of pan-cancer transcriptomics with RPPA proteomics reveals mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS Comput. Biol 14, e1005911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotsantis P, Silva LM, Irmscher S, Jones RM, Folkes L, Gromak N and Petermann E, 2016. Increased global transcription activity as a mechanism of replication stress in cancer. Nat. Commun 7, 13087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre A, Hukezalie K, Winckler P, Katranji F, Chanteloup G, Pirrotta M, Perrier-Cornet JM, Wong JM and Monchaud D, 2015. Visualization of RNA-quadruplexes in live cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 8521–8525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancrey A, Safa L, Chatain J, Delagoutte E, Riou JF, Alberti P and Saintome C, 2018. The binding efficiency of RPA to telomeric G-strands folded into contiguous G-quadruplexes is independent of the number of G4 units. Biochimie 146, 68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenti G and Tennant DA, 2016. Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), fumarate hydratase (FH): three players for one phenotype in cancer? Biochem. Soc. Trans 44, 1111–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Iskow R, Yang L, Gokcumen O, Haseley P, Luquette LJ 3rd, Lohr JG, Harris CC, Ding L, Wilson RK, Wheeler DA, Gibbs RA, Kucherlapati R, Lee C, Kharchenko PV, Park PJ and Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N., 2012. Landscape of somatic retrotransposition in human cancers. Science 337, 967–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexa M, Steflova P, Martinek T, Vorlickova M, Vyskot B and Kejnovsky E, 2014. Guanine quadruplexes are formed by specific regions of human transposable elements. BMC Genomics 15, 1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HY, Zhao Q, Zhang TP, Wu Y, Xiong YX, Wang SK, Ge YL, He JH, Lv P, Ou TM, Tan JH, Li D, Gu LQ, Ren J, Zhao Y and Huang ZS, 2016. Conformation Selective Antibody Enables Genome Profiling and Leads to Discovery of Parallel G-Quadruplex in Human Telomeres. Cell Chem Biol 23, 1261–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Liu Y, Liu Y, Alexandrov LB, Edmonson MN, Gawad C, Zhou X, Li Y, Rusch MC, Easton J, Huether R, Gonzalez-Pena V, Wilkinson MR, Hermida LC, Davis S, Sioson E, Pounds S, Cao X, Ries RE, Wang Z, Chen X, Dong L, Diskin SJ, Smith MA, Guidry Auvil JM, Meltzer PS, Lau CC, Perlman EJ, Maris JM, Meshinchi S, Hunger SP, Gerhard DS and Zhang J, 2018. Pan-cancer genome and transcriptome analyses of 1,699 paediatric leukaemias and solid tumours. Nature 555, 371–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macheret M and Halazonetis TD, 2015. DNA replication stress as a hallmark of cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol 10, 425–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath EP, Logue SE, Mnich K, Deegan S, Jager R, Gorman AM and Samali A, 2018. The unfolded protein response in breast cancer. Cancers 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakshi R, Rahman S, Jan AT, Archana A and Kim J, 2017. Implications of aging and the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response on the molecular modality of breast cancer. Exp. Mol. Med 49, e389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y, Kitamura N, Nakamura Y, Futamura M, Miyamoto T, Yoshida M, Ono M, Ichinose S and Arakawa H, 2011. Possible existence of lysosome-like organella within mitochondria and its role in mitochondrial quality control. PLoS One 6, e16054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musa J, Aynaud MM, Mirabeau O, Delattre O and Grunewald TG, 2017. MYBL2 (B-Myb): a central regulator of cell proliferation, cell survival and differentiation involved in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Dis. 8, e2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na U, Yu W, Cox J, Bricker DK, Brockmann K, Rutter J, Thummel CS and Winge DR, 2014. The LYR factors SDHAF1 and SDHAF3 mediate maturation of the iron-sulfur subunit of succinate dehydrogenase. Cell Metab. 20, 253–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Kitamura N, Shinogi D, Yoshida M, Goda O, Murai R, Kamino H and Arakawa H, 2012. BNIP3 and NIX mediate Mieap-induced accumulation of lysosomal proteins within mitochondria. PLoS One 7, e30767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocak S, Pedchenko TV, Chen H, Harris FT, Qian J, Polosukhin V, Pilette C, Sibille Y, Gonzalez AL and Massion PP, 2012. Loss of polymeric immunoglobulin receptor expression is associated with lung tumourigenesis. Eur. Respir. J 39, 1171–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panieri E and Santoro MM, 2016. ROS homeostasis and metabolism: a dangerous liason in cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannunzio NR and Lieber MR, 2018. Concept of DNA Lesion Longevity and Chromosomal Translocations. Trends Biochem. Sci 43, 490–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Bian XW, Li DK, Xu C, Wang GM, Xia QY and Xiong Q, 2015. Large-scale RNA-Seq Transcriptome Analysis of 4043 Cancers and 548 Normal Tissue Controls across 12 TCGA Cancer Types. Sci. Rep 5, 13413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JJ, Shin DS, Getzoff ED and Tainer JA, 2010. The structural biochemistry of the superoxide dismutases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 245–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiz J, Damert A, Chira S, Held U, Klawitter S, Hamdorf M, Lower J, Stratling WH, Lower R and Schumann GG, 2012. The non-autonomous retrotransposon SVA is trans-mobilized by the human LINE-1 protein machinery. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 1666–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambo RP and Tainer JA, 2010. Bridging the solution divide: comprehensive structural analyses of dynamic RNA, DNA, and protein assemblies by small-angle X-ray scattering. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 20, 128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambo RP and Tainer JA, 2013. Super-resolution in solution X-ray scattering and its applications to structural systems biology. Annu. Rev, Biophys 42, 415–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranzani M, Iyer V, Ibarra-Soria X, Del Castillo Velasco-Herrera M, Garnett M, Logan D and Adams DJ, 2017. Revisiting olfactory receptors as putative drivers of cancer. Wellcome Open Res. 2, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardiello F, Votta G, Palorini R, Raccagni I, Brunelli L, Paiotta A, Tinelli F, D’Orazio G, Valtorta S, De Gioia L, Pastorelli R, Moresco RM, La Ferla B and Chiaradonna F, 2018. Inhibition of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway by targeting PGM3 causes breast cancer growth arrest and apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 9, 377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond BW, Brucker RM, Han W, Du RH, Zhang Y, Cheng DS, Gleaves L, Abdolrasulnia R, Polosukhina D, Clark PE, Bordenstein SR, Blackwell TS and Polosukhin VV, 2016. Airway bacteria drive a progressive COPD-like phenotype in mice with polymeric immunoglobulin receptor deficiency. Nat. Commun 7, 11240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Tomaszowski KH, Luzwick JW, Park S, Li J, Murphy M and Schlacher K, 2018. p53 orchestrates DNA replication restart homeostasis by suppressing mutagenic RAD52 and POLtheta pathways. Elife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakyan AB, Murat P, Mayer C and Balasubramanian S, 2017. G-quadruplex structures within the 3’ UTR of LINE-1 elements stimulate retrotransposition. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 24, 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]