Abstract

Background:

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a multifunctional cytokine with both immunosuppressive and anti-angiogenicfunctions and may have both tumor-promoting and -inhibiting properties. We examined the association between a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in IL-10 -1082G/A (rs1800896) in Sudanese acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients and to assess the association between polymorphisms in IL-10 -1082G/A (rs1800896) and the hematological profile in Sudanese patients with AML.

Methods:

A total of 30 patients with acute myeloid leukemia and 30 control subjects were enrolled in this study. Blood samples were collected from all patients in EDTA containing tubes. Genomic DNA was extracted from all blood samples using salting out method. The genotypic variants of IL-10 (-1082G/A) polymorphism were detected by allele specific-PCR.

Results:

We found that (36.7%) of patients have homogenous GG genotype, (43.3%) have heterogeneous GA genotype and (20.0%) have AA genotype. GA genotype was significantly associated with higher risk of AML compared with the homozygous Genotypes (GG and AA), there is no association between IL-10 (-1082G/A) polymorphism and AML sub-type, gender, age group, mean of hematological parameters.

Conclusion:

Our study concluded that GA genotype of IL-10 -1082G/A (rs1800896) polymorphism is a risk factor for AML and G allele is insignificantly higher than A allele in AML patient. No association between IL-10 (-1082G/A) polymorphism and AML sub-type, gender, age group, mean of hematological parameters.

Key Words: Interleukin-10- polymorphism- acute myeloid leukemia

Introduction

Acute leukemia comprises acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (Mandegary et al., 2011). Adults have more risk than children to have AML, it is the most common type of acute leukemia affecting adults (Jiang et al., 2011). The etiology of AML is complicated and not fully understood. Numerous factors are thought to play an important role in AML development, for instance chemical exposure, ionizing radiation, and genetics (Evans and Steward, 1972; Le Beau et al., 1986).

Interleukins (ILs) are a varied set of small cells signaling protein molecules, or cytokines, their function is to alter the immune system in humans, ILs are predominantly produced by antigen-presenting cells, monocytes, macrophages, and endothelial cells, which are involved in the regulation of immune cell responses against infections, as well as governing the inflammation, differentiation, proliferation, and secretion of antibodies for tumor development (Fei et al., 2015) .Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of ILs may alter their function, thus changing cytokine function and dysregulating their expression (Fei et al., 2015).

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a multifunctional cytokine with both immunosuppressive and anti-angiogenic functions and may have both tumor promoting and inhibiting properties (Howell and Rose-Zerilli, 2006).

The gene encoding IL-10 is located on human chromosome 1, between 1q31 and 1q32 (Eskdale et al., 1997). Many SNPs have been distinguished within the cytokine gene sequence, particularly within the promoter regions, including IL10-1082A/G (rs1800870), -819C/T (rs1800871) and -592A/C (rs1800872). These polymorphisms may be associated with differential levels of gene transcription, since some alleles can produce low, medium and high amounts of IL-10 (Eskdale et al., 1997). The capability to secrete different cytokines appears to be significant in the immune response (Hutchinson et al., 1999). Genetic studies have been conducted to associate these cytokine polymorphisms with some types of cancer, but with varied results (Stanczuk et al., 2001; Roh et al., 2002; Szöke et al., 2004; Matsumoto et al., 2010).

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study conducted in Sudan to investigate the association between the IL-10 (1082G/A) polymorphism in AML patients and correlated with some hematological parameters.

So the main goal of this study is to examine the genotype frequency of IL-10 (1082G/A) polymorphism and exploring association between IL-10 (1082G/A) polymorphism and Risk of Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Furthermore, to assess correlation between IL-10 (1082G/A) polymorphism and some hematological parameter among Sudanese patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

In this is case-control study a total of 30 newly diagnosed AML patients were recruited at the Radio isotope center Khartoum (RICK) Sudan in the period from January to May 2017. AML diagnosis was determined according to World Health Organization criteria based on an increased number of myeloblasts in the bone marrow or peripheral blood (Vardiman et al., 2002). Patients with a history of cancer, known blood disorders, diabetes, and connective tissue disease were excluded from the study. Additionally, 30 age and gender-matched apparently healthy control subjects were recruited to participate in the study.

Sample collection

A venous blood sample (Three ml) was taken from each participant; these samples were collected into a tube containing K+ ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA).

Determination of Complete Blood Counts and Immunophenotype

Complete blood count was analyzed by using automated hematology analyzer (SYSMMEX KX-21N, Japan) within 6-24h from the collection. All results such total white blood cell (WBC) count, Hemoglobin (Hb) concentration and platelets count were recorded. And a blood smear stained by May Grunwald Giemsa was obtained for all patients. The diagnosis of AML was confirmed by Flow Cytometery, according to the standard procedure of diagnosis AML at Radio isotope at Radio Isotopes Center Khartoum (RICK) in Sudan (Osman et al., 2015). A marker was considered positive is a result ≥ 20% (Osman et al., 2015).

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted by salting out method(Miller et al., 1988). To assess the DNA quality after DNA extraction, the β-globin gene amplification was used to evaluate the quality of DNA in all extracted samples, as previously described (Kerr et al., 2000). All specimens for β-globin gene were Successful amplification, [Primers shown in Table1]. To evaluate the DNA quantification after DNA extraction, we measured DNA by using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Then DNA samples were routinely stored at -20oC.

Table 1.

The Primers Sequence for IL-10 -1082A/G Polymorphism Used were as Follow

| Primers | Sequence | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| IL-10 A Allele | 5’-CTACTAAGGCTTCTTTGGGAA-3’ | 550 bp |

| IL-10 G Allele | 5’-TACTAAGGCTTCTTTGGGAG-3’ | |

| IL-10 common | 5’-CAGCCCTTCCATTTTACTTTC-3’ | |

| β globin-GH20 (Forward) | 5’-GAAGAGCCAAGGACAGGTAC-3’ | 268 bp |

| β globin-PC04 (Reverse) | 5’-CAACTTCATCCACGTTCACC-3’ |

Genotyping of IL-10(1082G/A)

Genotyping was carried out by using the polymerase chain reaction with allele specific primers as described by (Newton et al., 1989). The primer sequences for genotyping are shown in (Table 1). Two separated PCR reaction mixtures of 20 µl was prepared for each sample. PCR was performed by using Maxime PCR Premix Kit (i-Taq), (iNtRON BIOTECHNOLOGY, SouthKorea), Cat. No. 25025), 4µl of genomic DNA, 0.5 µl of each primer, and 14 µl distilled water. Beta globin gene was used as the internal control. PCR started at 94°C for 5 min, followed by denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 58°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 40 s, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Thermo cycling was using TECHNE Tc-412-UK PCR Thermal Cycler 96 well.

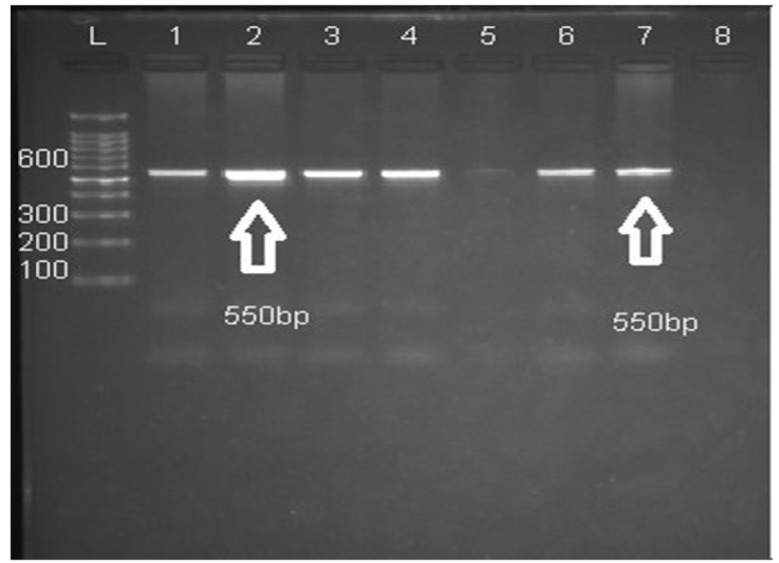

The amplified products were run on 1.5% agarose gel, and then stained with ethidium bromide for visualization under ultraviolet gel documentation system (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

It Shows the Sized Amplicons Outcome of AS-PCR

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 16.0 software. Chi square was done to determine the association and risk factor.

Gel electrophoresis showing IL-10 SNPs: Lane L: DNA marker (Ladder 100bp). Lanes 1, 2, 3, 4: heterozygous (A/G). Lanes 5, 6: homozygous (G/G). Lanes 7, 8: homozygous (A/A). Both alleles produce same size product 550 bp.

Results

Characteristics of 30 patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia

In this study, 30 cases of AML were targeted, the overall mean age was (20.23± 10.24) with range (3-37y). AML, however, is the most common in adults 21 (70.0%). Fourteen (46.6%) were males while sixteen (53.4%) were females; Male to female ratio was (0.9:1). The AML-M3was the most frequent 11(36.6%), followed by AML-M4 7(23.3%), whereas AML-M7was the least frequent 1 (3.3%). Regarding means white blood cell count was 39.14± 60.31×103/ul, hemoglobin level was 8.67± 2.51g/dL, platelet count was 93.33± 134.66×103/ul and peripheral blast percentage was 60.63± 21.01%.

IL-10 gene polymorphisms and AML

The genotype and allele frequencies for both patients and controls are listed in (Table 2), showing a highly statistically significant difference in the genotype distribution between cases and controls. GA genotype prevalence were significantly higher in cases than in controls 13, 43.4 % vs. 3, 10%, P = 0.003 respectively. On the other hand, AA genotype prevalence were higher among controls than in AML patients 16 (53.3%) vs 6 (20 %), P = 0.007, respectively. IL-10-(1082G/A) (GA+GG) genotype was increased risk of AML and there was a statistically significant correlation between GA genotype and AML risk.

Table 2.

Distribution of Genotypes and Allele Frequencies of IL-10 (A-1082 G) Polymorphism in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients and Controls

| Genotype | AML patients no (%) | Controls no (%) | P-value | Odd ratio | (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | |||||

| AA | 6 (20%) | 16 (53.3%) | 0.007 | 0.22 | 0.07-0.69 |

| GG | 11 (36.6%) | 11 (36.7%) | 1 | 1 | 0.35-2.86 |

| GA | 13 (43.4%) | 3 (10%) | 0.003 | 6.8 | 1.71-27.75 |

| Total | 30 (100%) | 30 (100%) | |||

| Combined | |||||

| GA+GG | 24 (80%) | 14 (46.6%) | 0.007 | 4.57 | 1.45-14.39 |

| AA | 6 (20 %) | 16 (53.4%) | |||

| AA+GA | 19 (63.3%) | 19 (63.3%) | 1 | 1 | 0.35-2.86 |

| GG | 11 (36.7%) | 11 (36.7) | |||

| Allele | |||||

| A | 26 (43.4%) | 32 (60%) | 0.67 | 0.33-1.37 | |

| G | 34 (56.6%) | 24 (40%) |

No statistically significant association found between any of IL10 genotypes and age, gender, total leucocyte count, Hb concentration, Platelets count, Blast percentage and FAB subtypes (P ˃ 0.05).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional descriptive study, 30 cases of AML were studied, the overall mean age was (20.23±10.24) with range (3-37y). AML is the most common in adults 21(70.0%). Nearly similar reported that found in literature (Ghosh et al., 2003; Estey and Döhner, 2006; Noronha et al., 2011; Osman et al., 2015).

The mean age of our patients with AML, was lower than the patients with AML in developed countries (Chang et al., 2004; Al-Mawali et al., 2008), but it was similar to other studies that performed in developing countries (Bittencourt et al., 2003; Ghosh et al., 2003; Rego et al., 2003; Osman et al., 2015). This can be explained by the fact that, in developed countries, life expectancy is higher and elderly individuals constitute a greater proportion of the population.

Fourteen (46.6%) were males while sixteen (53.4%) were females; Male to female ratio was (0.9:1). our result nearly similar to previous report in Sudan , in addition it showed that there is no male predominance, the male to female ratio 1.3:1. In contrast, the most studies have found that a higher incidence of AML is males (Bittencourt et al., 2003; Ghosh et al., 2003; Rego et al., 2003; Osman et al., 2015), this discrepancy may be due to small size of our patients group.

Regarding AML subtype in our patients, AML-M3 was the most frequent 11(36.6%), followed by AML-M4 7 (23.3%), whileAML-M7 was the least frequent 1 (3.3%). Osman et al., (2015) revealed that AML-M0 was the most common subtype. Whereas, Callera et al., (2006) explained that the higher prevalence of the AML subtype was AML-M1. Furthermore Ghosh et al., (2003), Pulcheri et al., (1995) and Bittencourt et al., (2003) found that a higher frequency of AML subtype was AML-M2.

In the recent years, a simple single nucleotide polymorphism arrays is efficient technique in order to detect genetic variation in malignant cell, including AML (Maciejewski et al., 2009).

IL10 is avital immuneregulatory cytokine, which is produced by activated T cells, monocytes, B cells, and thymocytes. IL10 has many functions including immunostimulating and immunosuppressive functions, and it may well control tumor susceptibility and development (Helminen et al., 1999; Villalta et al., 2010).

According to this hypothesis, several studies have been performed in order to investigate the association of the IL-10 promoter polymorphisms with cancers. Polymorphisms in the promoter region of the IL10 gene were related to cancer susceptibility, affected the severity, progression of the disease, and the level of IL10 expression (Zhou et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2010).

For AML, only little studies stated an association between in interleukin-10 (IL-10) -1082G/A (rs1800896) gene polymorphisms and risk of AML (Chenjiao et al., 2013; Yao et al., 2013); these studies showed that polymorphisms in rs1800871 and rs1800872 could be associated with increased risk of AML and were correlated with IL-10 mRNA expression in AML patients. Likewise, we also reported an association between 1082G/A (rs1800896), genetic variants and AML risk.

A study on the Chinese population presented that polymorphisms in interleukin-10 (rs1800871 and rs1800872) enhanced the susceptibility of AML, and these 2 SNPs had a synergistic effect on AML risk (Fei et al., 2015). A finding which is come to an agreement with our findings.

A study was done in Egypt (Rashed et al., 2018)and they did not find any association between IL-10 -819 T/C (rs1800871) promoter polymorphism and clinicopathological data such as AML sub-type, gender, age group, mean of the hematological parameter (TWBCs, Blast%, Hb and platelet count). A result which agrees with our findings.

In conclusions briefly, our study suggests that GA genotype of IL-10 -1082G/A (rs1800896) polymorphism is a risk factor for AML and G allele is insignificantly higher than A allele in AML patient. No association between IL-10 (-1082G/A) polymorphism and AML sub-type, gender, age group, mean of the hematological parameters (TWBCs, Blast%, Hb and platelet count).

Limitations

Limitations which are worth to remark are: sampling method was rest on voluntary contribution and no bone marrow samples were obtained, patients were not tracked up for progression of AML, survival rates and response to therapy administered after diagnosis confirmation. The preceding limitations should be well thought-out in the interpretation of this study results.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of Haematology Department at Al Neelain University for facilities and support and we are grateful to the staff of Radio Isotope Center Khartoum (RICK) for their collaboration. Finally, special thanks to the patients for being cooperative, despite their pain.

Authors’ contributions

OMS and IKI conceived the study design, participated in data collection, carried out the laboratory work, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. IKI, AAB and RH revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author details

Department of Haematology, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Sudan University of Science and Technology, Khartoum, Sudan1. Department of Haematology, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Al Neelain University, Khartoum, Sudan2. Department of Hematology, School of Medical Sciences, University Sains Malaysia, Health Campus, 16150 KubangKerian, Kelantan, Malaysia3.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Available of data and materials

The individual data are available in the archives of Radio isotope center Khartoum (RICK), Sudan. And can be obtained from the corresponding author on request.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Al Neelain University. Principal investigator obtained written informed consent from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any fund or financial support.

References

- Al-Mawali A, Gillis D, Hissaria P, et al. Incidence, sensitivity, and specificity of leukemia-associated phenotypes in acute myeloid leukemia using specific five-color multiparameter flow cytometry. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:934–45. doi: 10.1309/FY0UMAMM91VPMR2W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt R, Fogliato L, Daudt L, et al. Leucemia Mielóide Aguda: perfil de duas décadas do Serviço de Hematologia do Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre-RS. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2003;25:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Callera F, Mulin CC, Rosa ES, et al. High prevalence of morphological subtype FAB M1 in adults with de novo acute myeloid leukemia in São José dos Campos, São Paulo. Sao Paulo Med J. 2006;124:45–7. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802006000100010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Salma F, Yi Q-l, et al. Prognostic relevance of immunophenotyping in 379 patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2004;28:43–8. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(03)00180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Li B, Wei Y, et al. Interleukin-10-819 promoter polymorphism associated with gastric cancer among Asians. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:1–8. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenjiao Y, Zili F, Haibin C, et al. IL-10 promoter polymorphisms affect IL-10 production and associate with susceptibility to acute myeloid leukemia. Die Pharmazie-An Int J Pharm Sci. 2013;68:201–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskdale J, Kube D, Tesch H, et al. Mapping of the human IL10 gene and further characterization of the 5’flanking sequence. Immunogenetics. 1997;46:120–8. doi: 10.1007/s002510050250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estey E, Döhner H. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2006;368:1894–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D, Steward J. Down’s syndrome and leukaemia. Lancet. 1972;300:1322. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92704-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei C, Yao X, Sun Y, et al. Interleukin-10 polymorphisms associated with susceptibility to acute myeloid leukemia. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:925–30. doi: 10.4238/2015.February.2.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Shinde S, Kumaran G, et al. Haematologic and immunophenotypic profile of acute myeloid leukemia: an experience of Tata Memorial Hospital. Indian J Cancer. 2003;40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helminen M, Lahdenpohja N, Hurme M. Polymorphism of the interleukin-10 gene is associated with susceptibility to Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:496–9. doi: 10.1086/314883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell WM, Rose-Zerilli MJ. Interleukin-10 polymorphisms, cancer susceptibility and prognosis. Fam Cancer. 2006;5:143–9. doi: 10.1007/s10689-005-0072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson I, Pravica V, Hajeer A, et al. Identification of high and low responders to allografts. Rev Immunogenet. 1999;1:323–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Lu Y, Yuan L, et al. Regulation of interleukin-10 receptor ubiquitination and stability by beta-TrCP-containing ubiquitin E3 ligase. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J, Al-Khattaf A, Barson A, et al. An association between sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) andHelicobacter pylori infection. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83:429–34. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.5.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Beau MM, Albain K, Larson R, et al. Clinical and cytogenetic correlations in 63 patients with therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes and acute nonlymphocytic leukemia: further evidence for characteristic abnormalities of chromosomes no 5 and 7. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:325–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewski JP, Tiu RV, O’Keefe C. Application of array-based whole genome scanning technologies as a cytogenetic tool in haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2009;146:479–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandegary A, Rostami S, Alimoghaddam K, et al. Gluthatione-S-transferase T1-null genotype predisposes adults to acute promyelocytic leukemia; a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1279–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Oki A, Satoh T, et al. Interleukin-10− 1082 gene polymorphism and susceptibility to cervical cancer among Japanese women. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:1113–6. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Dykes D, Polesky H. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton C, Graham A, Heptinstall L, et al. Analysis of any point mutation in DNA The amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS) Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2503–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.7.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noronha EP, Marinho HT, Thomaz EBAF, et al. Immunophenotypic characterization of acute leukemia at a public oncology reference center in Maranhão, northeastern Brazil. Sao Paulo Med J. 2011;129:392–401. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802011000600005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman IM, Humeida A, Eltayeb O, et al. Flowcytometric Immunophenotypic characterization of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in Sudan. Int J Hematol Dis. 2015;2:10–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pulcheri W, Spector N, Nucci M, et al. The treatment of acute myeloid leukemia in Brazil: progress and obstacles. Haematologica. 1995;80:130–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashed R, Shafik RE, Shafik NF, et al. Associations of interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms with acute myeloid leukemia in human (Egypt) J Cancer Res Ther. 2018;14:1083. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.187367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rego M, Pinheiro G, Metze K, et al. Acute leukemias in Piauí: comparison with features observed in other regions of Brazil. Brazil J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:331–7. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh JW, Kim MH, Seo SS, et al. Interleukin-10 promoter polymorphisms and cervical cancer risk in Korean women. Cancer Lett. 2002;184:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanczuk GA, Sibanda EN, Perrey C, et al. Cancer of the uterine cervix may be significantly associated with a gene polymorphism coding for increased IL-10 production. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:792–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szöke K, Szalmás A, Szládek G, et al. IL-10 promoter nt-1082A/G polymorphism and human papillomavirus infection in cytologic abnormalities of the uterine cervix. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2004;24:245–51. doi: 10.1089/107999004323034114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002;100:2292–302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalta SA, Rinaldi C, Deng B, et al. Interleukin-10 reduces the pathology of mdx muscular dystrophy by deactivating M1 macrophages and modulating macrophage phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;20:790–805. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao C-J, Du W, Chen H-B, et al. Associations of IL-10 gene polymorphisms with acute myeloid leukemia in Hunan, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:2439–42. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.4.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Zhu W, Li M, et al. Association of single nucleotide polymorphism at interleukin-10 gene 1082 nt with the risk of gastric cancer in Chinese population. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2008;28:1335–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]