Abstract

SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy is a severe genetic epilepsy syndrome caused by de novo gain-of-function mutations of SCN8A encoding the voltage-gated sodium (Na) channel (VGSC) NaV1.6. Therapeutic management is difficult in many patients, leading to uncontrolled seizures and risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). There is a need to develop novel anticonvulsants that can specifically target aberrant Na channel activity associated with SCN8A gain-of-function mutations. In this study, we investigate the effects of Prax330, a novel Na channel inhibitor, on the biophysical properties of WT NaV1.6 and the patient mutation p.Asn1768Asp (N1768D) in ND7/23 cells. The effects of Prax330 on persistent (INaP) and resurgent (INaR) Na currents and neuronal excitability in subiculum neurons from a knock-in mouse model of the Scn8a-N1768D mutation (Scn8aD/+) were also examined. In ND7/23 cells, Prax330 reduced INaP currents recorded from cells expressing Scn8a-N1768D and hyperpolarized steady-state inactivation curves. Recordings from brain slices demonstrated elevated INaP and INaR in subiculum neurons from Scn8aD/+ mutant mice and abnormally large action potential (AP) burst-firing events in a subset of neurons. Prax330 (1 μM) reduced both INaP and INaR and suppressed AP bursts, with smaller effect on AP waveforms that had similar morphology to WT neurons. Prax330 (1 μM) also reduced synaptically-evoked APs in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons but not in WT neurons. Our results highlight the efficacy of targeting INaP and INaR and inactivation parameters in controlling subiculum excitability and suggest Prax330 as a promising novel therapy for SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy.

Keywords: Sodium channels, Persistent Sodium Current, Resurgent Sodium Current, Prax330, Subiculum, Epileptic Encephalopathy, SCN8A, Action Potentials

1. Introduction

SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE13) is caused by de novo gain-of-function mutations in the SCN8A gene encoding VGSC isoform NaV1.6 (de Kovel et al., 2014; Estacion et al., 2014; Veeramah et al., 2012). Localized predominantly at the axon initial segment (AIS) and nodes of Ranvier, NaV1.6 strongly determines membrane potential and action potential (AP) firing properties of neurons under normal conditions and in disease (Barker et al., 2017; Blumenfeld et al., 2009; Caldwell et al., 2000; Duflocq et al., 2008; Hargus et al., 2013, n.d.; Hu et al., 2009). Patients with SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy exhibit seizure onset in infancy leading to motor and cognitive impairment (Larsen et al., 2015; Wagnon and Meisler, 2015).

The first characterized SCN8A encephalopathy mutation was p.Asn1768Asp (N1768D) (Veeramah et al., 2012). The patient presented with refractory epilepsy at six months of age, intellectual disability, ataxia, and sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP) at 15 years. Biophysical characterization of the mutation in expression systems and neurons revealed a depolarizing shift in the voltage-dependence of steady-state inactivation, an increase in the non-inactivating persistent sodium current (INaP) after termination of the transient current (INaT), and an elevated resurgent current (INaR) (Ottolini et al., 2017; Patel et al., 2016; Veeramah et al., 2012). INaP has been implicated in setting AP threshold (Deng and Klyachko, 2016), amplifying incoming excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs (Hardie and Pearce, 2006; Stafstrom et al., 1985; Stuart and Sakmann, 1995), driving the burst-firing mode of AP firing (Alkadhi and Tian, 1996; Su et al., 2001; Tsuruyama et al., 2013), and orchestrating rhythmogenesis in various neuronal circuits (Dong and Ennis, 2014; Paton et al., 2006; Tazerart et al., 2008; Yamanishi et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2007). Studies of animal models and human epilepsy tissue have reported increases in INaP (Barker et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2011; Hargus et al., 2013; Lopez-Santiago et al., 2017; Ottolini et al.,2017; Stafstrom, 2007; Tryba et al., 2011; Vreugdenhil et al., 2004). INaR also contributes to increased AP frequency and burst firing (Khaliq et al., 2003; Raman et al., 1997; Raman and Bean, 1997). It has therefore been suggested that elevation of INaP and INaR, due to expression of mutant VGSC or other modulation of VGSC function, may be a central mechanism contributing to neuronal hyperexcitability associated with seizure initiation (Stafstrom, 2007).

Many clinically available antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) that target VGSCs inhibit INaP, including phenytoin, carbamazepine, topiramate, and lamotrigine (Alexander and Huguenard, 2014; Colombo et al., 2013; Segal and Douglas, 1997; Spadoni et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2007). For this reason, development of a preferential inhibitor of INaP could lead to a more efficacious and potentially better tolerated AEDs (Stafstrom, 2007). Prax330 was initially developed as a selective INaP inhibitor to treat cardiac arrhythmia (Belardinelli et al., 2013; Koltun et al., 2016), however, due its brain permeability and half-life, development of Prax330 was repurposed as an AED (Belardinelli et al., 2013; Koltun et al., 2016). More recently, Prax330 has been evaluated for efficacy in a number of severe genetic epilepsy syndrome models. In vivo studies in Scn1a+/−, Scn2aQ54, Scn8aR1872W/+, and Scn8aD/+ mouse models of epileptic encephalopathy revealed that Prax330 is able to potently reduce INaP and suppress spontaneous AP firing in acutely dissociated hippocampal neurons, normalize CA1 pyramidal AP waveforms, protect against seizures, and extend survival (Anderson et al., 2017, 2014; Baker et al., 2018; Bunton-Stasyshyn et al., 2019).

In order to further investigate the mechanisms by which Prax330 exhibits anticonvulsant activity in the Scn8aD/+ mouse model of epileptic encephalopathy, we examined the effects of Prax330 on the biophysical properties of the mutant NaV1.6-N1768D in ND7/23 cultured cells and on INaP, INaR, and neuronal excitability in subiculum neurons from Scn8aD/+ mice. Subiculum neurons were chosen because they provide the primary output of the hippocampus and have been previously implicated in epilepsy (Barker et al., 2017; de Guzman et al., 2006; Fujita et al., 2014; Toyoda et al., 2013; Vreugdenhil et al., 2004). In ND7/23 cells, Prax330 reduced INaP currents in N1768D-expressing cells and caused a leftward shift in inactivation curves of both WT and N1768D channels. Electrophysiological recordings revealed elevated INaP and INaR currents and aberrantly large AP-burst waveforms in a subset of Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons. Prax330 (1 μM) reduced INaP and INaR and attenuated the abnormal AP-burst waveforms in this subset of subiculum neurons without affecting those with normal AP morphology. Synaptically-evoked APs from Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons were inhibited by Prax330 (1 μM) while WT neurons were unaffected. These findings suggest that Prax330 preferentially targets aberrant Na channels associated with SCN8A mutations and may be useful in the treatment of SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy and other forms of genetic and acquired epilepsy.

2. Methods

2.1. ND7/23 Electrophysiology

The introduction of the N1768D mutation into the TTX-resistant Nav1.6 cDNA was previously described (Veeramah et al, 2012). DRG-neuron derived ND7/23 cells (Sigma Aldrich) were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM 1X) supplemented with 10% FBS, NEAA and Sodium Pyruvate. Cells were plated onto petri dishes 48 hours prior to transfection and transfected for 5 hours in non-supplemented DMEM using Lipofectamine 3000 according to manufacturer instructions (Life Technologies) with 5 μg of NaV1.6 alpha subunit cDNA and 0.5 μg of the fluorescent m-Venus bioreporter. Electrophysiological recordings of fluorescent cells were made 48 hours after transfection.

Whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiological recordings of sodium currents were carried out as described previously (Barker et al., 2016; Wagnon et al., 2018, 2016). The external recording solution contained in mM: 130 NaCl, 3 KCL, 1 CaCl2, 5 MgCl2, 0.1 CdCl2, 10 HEPES, 30 TEA, 4 4-AP, and 500 nM TTX to block any endogenous Na currents (pH adjusted to 7.4 using NaOH). The osmolality was confirmed to be ~305 mOsm. The intracellular recording solution contained in mM: 140 CsF, 2 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 4 Na2ATP, 0.3 NaGTP (pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH and osmolality adjusted to 300 mOsm). All experiments were performed at room temperature (22-24°C). Borosilicate recording pipettes were pulled to have resistances of 1.5-3.0 MΩ in recording solution. After achieving the whole-cell configuration, whole-cell capacitance and 75% series resistance were compensated. Currents were amplified, low-pass filtered at 2 kHz, and sampled at 33kHz. Cells were held at −120 mV. The voltage-dependent activation was measured from the current-voltage relationship determined using a 100 ms voltage step to command potentials ranging from −80 to 70 mV at 5 mV increments and conductance as a function of voltage was described by a Boltzmann fit of the data. The average INaP was taken to be the average current from 60-100 ms after the onset of the voltage step, once the current had reached steady state, and recorded as a percentage of the magnitude of the INaT. Steady-state inactivation, cells were stepped to pre-pulse potentials ranging from −120 to −10 mV for 500 ms before being stepped to −10 mV to assess channel availability. When calculating steady-state inactivation conductance as a function of voltage, the current of greatest magnitude was determined normalized to 1 and the final sweep which is a continuous step to −10 mV, which does not evoke any INaT, was set to be 0. The results are well-fit by a single Boltzmann equation as previously described (Barker et al., 2016).

2.2. Brain Slice Preparation

WT and Scn8aD/+ mice greater than 8 weeks of age were euthanized using isoflurane and decapitated. The brains were rapidly removed and kept in ice-cold (~0°C) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing in mM: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 0.5 L-Ascorbic acid, 10 glucose, 25 NaHCO3, and 2 Pyruvate. The ACSF at all stages of the experiment was oxygenated with 95%/5% O2/CO2. Horizontal brain sections of 300 μM thickness were cut using a Leica VT1200 vibratome. The slices were placed in 37°C oxygenated ACSF for ~30 minutes and then kept at room temperature.

2.3. Electrophysiology

Brain slices were placed in small chamber continually superfused (~1-2 mL/min) with recording solution warmed to (~32°C). Subiculum pyramidal neurons were visually identified by infra-red video microscopy (Hamamatsu, Shizouka, Japan) using a Zeiss Axioscope microscope. Whole-cell recordings were performed using an Axopatch 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, pCLAMP 10 software) and were digitized by a Digidata 1322A digitizer (Molecular Devices). Currents were amplified, low-pass filtered at 2 kHz, and sampled at 100 kHz. Borosilicate electrodes were fabricated using a Brown-Flaming puller (Model P1000, Sutter Instruments Co) to have pipette resistances between 2-3.5 MΩ.

2.3.1. INaP Recordings

INaP currents were recorded as previously described using a solution containing in mM: 20 NaCl, 130 TEA-Cl, 10 NaHCO3, 1.6 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 0.2 CdCl2, and 5 4-AP, and 15 glucose (pH adjusted to 7.4; 305 mOsm) (Ottolini et al., 2017). The pipette solution contained (in mM): 140 CsF, 2 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 4 Na2ATP, and 0.3 NaGTP (pH adjusted to 7.3, 310 mOsm). Voltage ramps from −100 to −10 at 65 mV/sec led to inward ramp currents with a clear peak near −30 mV. Any cells with ramp currents that escaped voltage-control were discarded and not analyzed. Identical recordings in the presence 500 nM TTX were used to definitively isolate the sodium component of the ramp current. TTX-subtracted traces were used for calculation of peak inward current and the voltage of half-maximal activation (V1/2).

2.3.2. INaR Recordings

INaR currents were recorded as previously described using a modified recording solution containing in mM: 100 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 19.5 TEA-Cl, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 2 BaCl2, 0.1 CdCl2, 4 4-AP, and 10 glucose (pH of 7.4; 305 mOsm) (Barker et al., 2017). The intracellular solution was the same as that for INaP recordings. Neurons were held at −100 mV, depolarized to 0 mV for 20 ms and then repolarized to voltages ranging between −100 mV and −20 mV in increments of 10 mV. The peak amplitude of INaR was calculated as the maximum TTX-sensitive current elicited (typically on the −30 mV step) with the steady-state current subtracted as done previously (Royeck et al., 2008).

2.3.3. AP Recordings

Current clamp recordings were performed with an extracellular recording solution identical to that used in the slicing procedure. The intracellular solution contained in mM: 120 K-gluconate, 10 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.5 K2EGTA, 10 HEPES, 4 Na2ATP, 0.3 NaGTP (pH 7.2; osmolarity 290 mOsm). A ramp of depolarizing current 100 pA/sec was used to accurately measure AP threshold which was defined as the membrane potential at which the slope reached 5% of the upstroke velocity (Yamada-Hanff and Bean, 2013). AP amplitude was calculated as the range between threshold and the peak of the AP. A range of depolarizing current injections (−20 to 470 pA in increments of 10 pA) was used to calculate membrane and AP properties. To compare across all neurons, a slow injection of DC current was used to hold neurons at −65 mV throughout the recording. The rheobase was defined as the highest current step injected that did not result in AP firing. Input resistance was calculated using the initial −20 pA step. The upstroke and downstroke velocities were the maximum and minimum of the first derivative of the recorded trace. The AP duration (APD50) was measured as the time duration of the AP measured at the midpoint between the threshold and the peak of the AP. The area under the curve (AUC) of the first AP was calculated relative to AP threshold for each cell. Synaptically-evoked APs were generated through stimulation of the CA1 afferents using a bipolar iridium stimulator (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA). The stimulus duration was 400 μs and the intensity was adjusted (usually between 1 and 3.2 mA) to evoke APs on successive sweeps with a 10 second inter-sweep interval.

2.4. Drug

Prax330 was provided by Praxis Precision Medicines and was solubilized in DMSO at a stock concentration of 10 mM and stored at −20°C. For all electrophysiology experiments, initial recordings were collected at baseline and then again after ~10 minutes with bath solution containing Prax330. Vehicle control recordings were done in an identical manner without Prax330.

2.5. Data Analysis

All data were analyzed by custom-written MATLAB scripts, or manually with ClampFit. Graphpad software was used for displaying data and for all statistical calculations. All values represent means ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) or as individual data points. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired or paired t-test where appropriate with an alpha set to 0.05 (GraphPad Prism 6.02).

3. Results

3.1. Prax330 inhibits INaP and modulates inactivation parameters of NaV1.6 currents recorded in ND7/23 cells

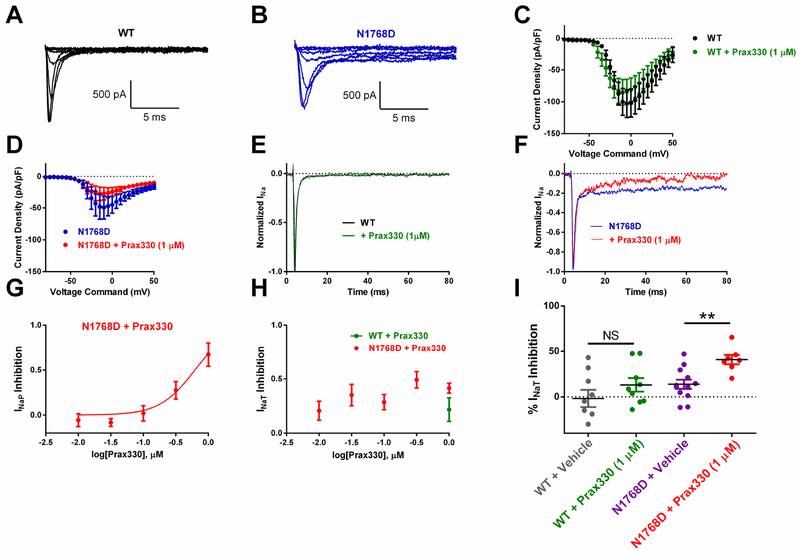

We first characterized the effect of Prax330 on WT and N1768D NaV1.6 expressed in ND7/23 cells. Cells were held at −120 mV and stepped to potentials between −80 and 50 mV to examine the current-voltage relationship. Current densities between WT and N1768D cells were not different (WT: −103 ± 22 pA/pF (n=9), N1768D: −45 ± 14 pA/pF (n=7); Figure 1A–D). In agreement with previous studies (Veeramah et al., 2012), a pronounced elevation of INaP was observed in N1768D transfected cells (Figure 1B, F). INaP was barely detectable in WT NaV1.6 transfected cells (Figure 1A, E). Prax330 inhibited N1768D-derived INaP in a dose-dependent manner with an approximate EC50 of 625 nM and a Hill slope of 1.5 (Figure 1G). At 1 μM, Prax330 significantly inhibited INaP by 67% (8.1 ± 1.3% of INaT before and 3.0 ± 1.1% of INaT after Prax330; T(6)=3.61; P=0.0112; Figure 1F). Prax330 (1 μM) had no effect on INaT in WT cells (−103 ± 22 pA/pF at baseline to −84 ± 19 pA/pF after Prax330 treatment; n=9; Figure 1E, I). Prax330 did significantly reduce INaT in N1768D cells by 49 ± 10% at 300nM (T(14)= 3.395; P=0.0044; n= 4) and by 41 ± 5% at 1 μM (T(17)=3.48; P=0.0029; n=7) when compared to vehicle-treated time controls. (Figure 1H, I). These findings suggest that Prax330 shows a particular efficacy toward the N1768D mutation compared to WT.

Figure 1. Prax330 inhibits N1768D-derived INaP in NaV1.6-expressing cells.

A-B. Families of NaV1.6 channel current traces for WT- (A) and N1768D- (B) expressing ND7/23 cells. C. Current/voltage relationship for WT NaV1.6 channel current density before (black) and after (green) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). D. Current/voltage relationship for N1768D NaV1.6 channel current density before (blue) and after (red) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). E. Example normalized trace for WT before (black) and after (green) Prax330 (1 μM) treatment. F. Example normalized trace for N1768D before (blue) and after (red) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). G. Dose-response curve for Prax330 on N1768D INaP (EC50 of 625 nM). H. Dose-response effect of Prax330 on INaT. I. Scatter plot showing effects of vehicle (gray; n=9) and Prax330 (1 μM; green; n=9) on WT INaT and vehicle (purple; n=12) or Prax330 (1 μM; red; n=7) on N1768D INaT. Holding potential was −120 mV for all protocols. Data shown as individual values and/or mean ± SEM. **P<0.01.

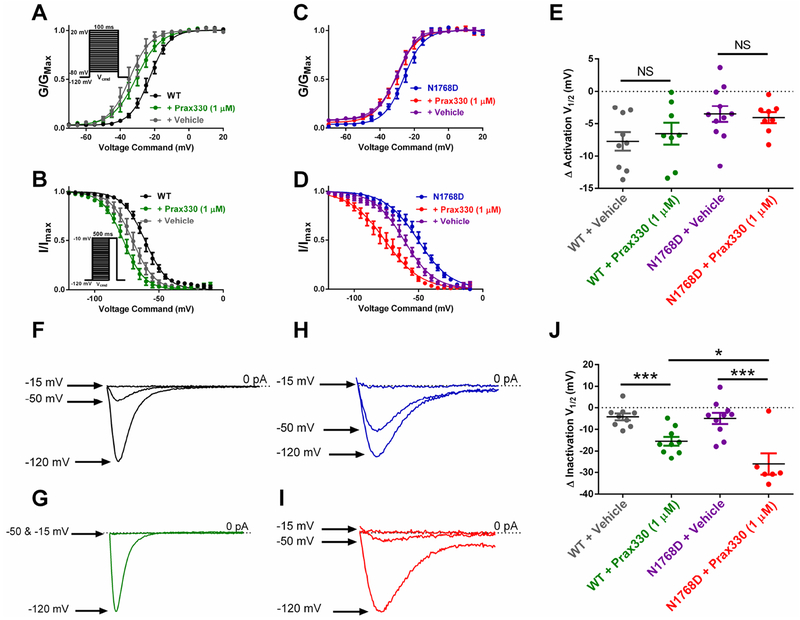

We assessed the effect of Prax330 (1 μM) on the voltage-dependence of steady-state activation and inactivation (Figure 2; Table 1). Voltage-dependent activation parameters were not different between WT and N1768D transfected cells (Table 1), but steady-state inactivation curves were significantly right-shifted in N1768D cells compared with WT, as previously reported (T(12)=4.173; P=0.0013; Fig. 2B,D; Table 1) (Veeramah et al., 2012). Left-shifts in activation curves for both WT and N1768D recorded in the presence of Prax330 (1 μM) were not different from shifts observed in vehicle-treated control recordings, indicating that Prax330 has no effect on activation parameters (Figure 2E; Table 1). In contrast, left-shifts in steady-state inactivation after Prax330 (1 μM) treatment for both WT and N1768D cells were significantly larger than that observed in vehicle controls suggesting that Prax330 (1 μM) has an affinity for inactivated channels (P<0.05; Table 1, Figure 2B–J).

Figure 2. Prax330 hyperpolarizes steady-state inactivation curves in WT and N1768D NaV1.6 channel currents.

A. Voltage-dependent activation curve for WT NaV1.6 channel currents before (black), after treatment with Prax330 (gree; 1 μM; n=9), and vehicle control (gray; n=9). Inset shows voltage command protocol. Cells were held at −120 mV. B. Steady-state inactivation curves for WT Nav1.6 channel currents before (black) and after treatment with Prax330 (green; 1 μM; n=9). Vehicle-treated controls are shown in gray (n=9). Inset shows voltage command protocol. Cells were held at −120 mV C. Voltage-dependent activation for N1768D NaV1.6 channel currents before (blue) and after administration of Prax330 (red; 1 μM; n=8) or vehicle (purple; n=11). D. Steady-State inactivation for N1768D channel currents before (blue) and after treatment with Prax330 (red; 1 μM; n=6) or vehicle (purple; n=10). E. Activation half-maximal voltage (V1/2) were not different between WT plus vehicle (gray; n=9) or WT plus Prax330 (1 μM; green, n=9), or N1768D plus vehicle (purple; n=11), and N1768D plus Prax330 (1 μM; red, n=8). Example traces of WT steady-state inactivation showing relative INaT after 500 ms pre-pulses to −120 mV, −50 mV, and −15 mV before (F) and after (G) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). Example traces of N1768D steady-state inactivation showing relative INaT after 500 ms pre-pulses to −120 mV, −50 mV, and −15 mV before (H) and after (I) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). J. Hyperpolarizing shifts in steady-state inactivation V1/2 for WT plus vehicle (gray; n=9), WT plus Prax330 (1 μM; green; n=9), N1768D plus vehicle (purple; n=10), and N1768D plus Prax330 (1 μM; red; n=6). Data shown as individual values and/or mean ± SEM. *P< 0.05, ***P<0.001.

TABLE 1.

Effect of Prax330 (1 μM) on WT and N1768D NaV1.6 sodium currents

| Activation | Inactivation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1/2 (mV) | k | V1/2 (mV) | k | |

| WT | −22.7 ± 1.5 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | −60.9 ± 1.8 | 8.0 ± 0.3 |

| + Vehicle | −35.0 ± 2.0 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | −67.8 ± 2.0 | 7.6 ± 0.3 |

| + Prax330 (1 μM) | −30.4 ± 2.4 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | −77.3 ± 2.4* | 7.7 ± 0.3 |

| N1768D | −25.6 ± 1.4 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | −50.8 ± 2.6# | 12.8 ± 1.3# |

| + Vehicle | −32.6 ± 1.0 | 6.4 ± 0.5 | −62.0 ± 2.3 | 10.8 ± 0.9 |

| + Prax330 (1 μM) | −30.2 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | −76.9 ± 3.7* | 12.4 ± 0.9 |

indicates p<0.05 comparing vehicle and Prax330 application using unpaired t-test.

indicates p<0.05 comparing WT and N1768D groups using unpaired t-test.

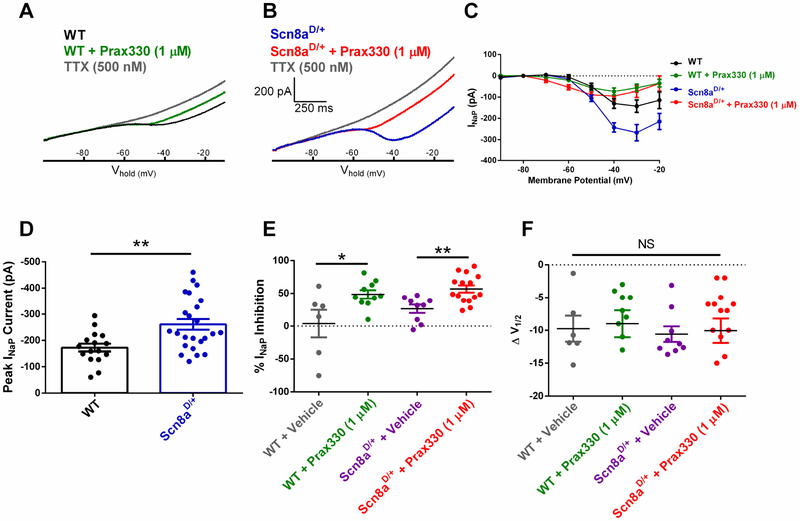

3.2. INaP is accentuated in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons and is inhibited by Prax330

INaP was measured in subiculum neurons from acute brain slices obtained from Scn8aD/+ mice and compared with WT littermates using slow voltage ramps from the holding potential of −100 mV to −10 mV at 65 mV/sec. Maximum INaP were significantly increased in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons (−261 ± 20 pA; n = 24, 8 mice) compared to WT neurons (−173 ± 15 pA; T(38)=3.167; P=0.003; n=10, 7 mice; Figure 3A–D). When compared to vehicle-treated controls, Prax330 (1 μM) inhibited both WT (by 48.5 ± 6.3%; n = 10, 4 mice: T=2.497; P=0.0256) and Scn8aD/+ (by 56.9 ± 5.5%; n = 15, 5 mice: T=3.511; P=0.0020; Figure 3E). Voltage-dependent activation parameters were not different between Prax330-treated and vehicle-treated neurons (Figure 3F).

Figure 3. Prax330 (1 μM) inhibits INaP in subiculum pyramidal neurons.

A. Representative recording of INaP for WT before (black) and after (green) treatment with 1 μM Prax330 and 500 nM TTX (gray). B. Representative recording of INaP for Scn8aD/+ before (blue) and after (red) treatment with 1 μM Prax330 and 500 nM TTX (gray). C. Current/voltage relationship of INaP for WT before (black) and after (green) Prax330 (1 μM) and current/voltage relationship of Scn8aD/+ before (blue) and after (red) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). D. Peak INaP current for WT (n=16 neurons, 7 mice) and Scn8aD/+ (n=24 neurons, 8 mice) subiculum neurons. Scn8aD/+ neurons have significantly larger peak INaP. E. Percent inhibition of INaP for WT plus vehicle (gray; n=6 neurons, 3 mice), WT plus Prax330 (1 μM; green; n=10 neurons, 4 mice), Scn8aD/+ plus vehicle (purple; n=9 neurons, 3 mice), and Scn8aD/+ plus Prax330 (1 μM; red, n=15 neurons, 5 mice). Compared to vehicle controls, Prax330 inhibited the steady-state INaP in both WT and Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons. F. Leftward shifts observed in activation V1/2 were not different between WT, N1768D or their respective vehicle controls; WT plus vehicle (gray), WT plus Prax330 (1 μM; green), Scn8aD/+ plus vehicle (purple), and Scn8aD/+ plus Prax330 (1 μM; red). Data shown as individual values and/or mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

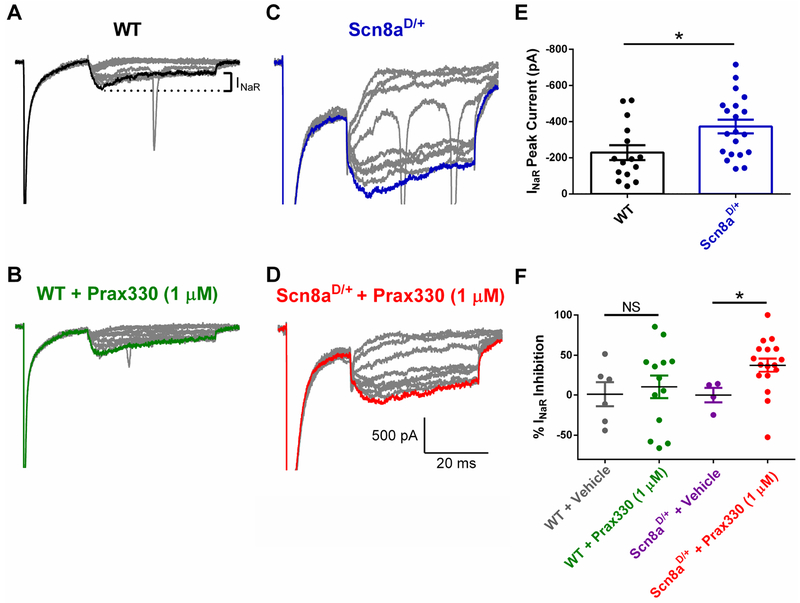

3.3. Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons have elevated INaR which is inhibited by Prax330.

INaR was also significantly elevated in Scn8aD/+ brain slice subiculum neurons (−373.1 ± 41 pA; n=20, 7 mice) compared to WT neurons (−229 ± 41 pA; n=15, 8 mice; T(33)=2.559; P=0.0153; Fig 4. A, C, E). Compared to vehicle-treated controls (n = 4; 2 mice), Prax330 (1 μM) inhibited INaR by 37.6 ± 8.3% in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons (n = 16; 5 mice, T(18)=2.098; p=0.0495). In contrast, Prax330 (1 μM) had no effect on WT neurons (Figure 4F), suggesting that Prax330 preferentially inhibits INaR in Scn8aD/+ neurons.

Figure 4. Scn8aD/+ subiculum neuron INaR currents are inhibited by 1 μM Prax330.

A-B. Representative TTX-subtracted INaR traces for WT before (A) and after (B) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). C-D. Scn8aD/+ TTX-subtracted INaR traces before (C) and after (D) Prax330 1 μM treatment. E. Peak INaR for untreated WT (n=15 neurons, 8 mice) and Scn8aD/+ (n=20 neurons, 7 mice). Scn8aD/+ neurons have larger peak INaR compared to WT neurons. F. Percent inhibition of INaR for WT plus vehicle (gray; n=6 neurons, 3 mice), WT plus Prax330 (1 μM; green, n=13 neurons, 5 mice), Scn8aD/+ plus vehicle (purple; n=4 neurons, 2 mice), and Scn8aD/+ plus Prax330 (1 μM; red, n=13 neurons, 5 mice). Compared to vehicle controls, Prax330 did not inhibit the steady-state INaP in WT (P>0.05) but did inhibit INaR in Scn8aD/+ neurons. Data shown as individual values and mean ± SEM. *P<0.05.

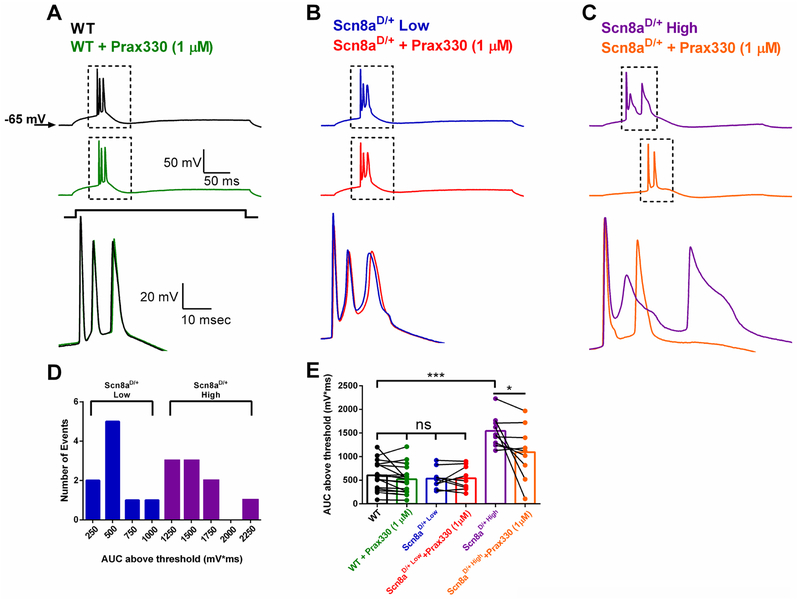

3.4. Prax330 attenuates aberrant burst AP-firing in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons.

Aberrant neuronal excitability in AP firing frequency and AP waveform morphology has been reported in medial entorhinal cortex (mEC) and CA1 neurons from Scn8aD/+ mice (Baker et al., 2018; Lopez-Santiago et al., 2017; Ottolini et al., 2017). Since subiculum neurons provide a major output from the hippocampus and have been implicated in seizure initiation in TLE (Barker et al., 2017; de Guzman et al., 2006; Fujita et al., 2014; Stafstrom, 2005; Toyoda et al., 2013), we examined subiculum neurons from Scn8aD/+ mice (Figure 5). We found no differences in subiculum neuron AP firing frequencies between Scn8aD/+ and WT mice (27.9 ± 2.4 Hz; n=18, 7 mice and 27.5 ± 1.7 Hz; n=17, 4 mice respectively). However, a subset of Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons (~ 50%) displayed a distinct, all-or-nothing AP burst that was associated with a significantly larger depolarizing event measured by taking the area under the curve (AUC) above AP threshold (1542 ± 112 mV*ms in Scn8aD/+ compared to 605 ± 74 mV*ms in WT; T(24)=7.219; P<0.0001; Fig. 5 A–C,E). The possible bimodal distribution for the AUC led us to separate Scn8aD/+ neurons into two equal groups (n=9 cells each) based on the magnitude of AUC, Scn8aD/+-low and high respectively, and examine the relative efficacy of Prax330 on the two groups (Fig. 5 D). Interestingly, Prax330 (1μM) had no significant effect on the burst AUC for WT or Scn8aD/+-low groups suggesting that Scn8aD/+ neurons with physiological burst-firing resembling WT are relatively unaffected by Prax330 (Fig. 5 A–B, E). In contrast, Scn8aD/+-high group neurons were profoundly modulated by Prax330 (1μM), resulting in a significant reduction in the AUC value (1542 ± 112 mV*ms before and 1095 ± 192 mV*ms after treatment with Prax330; T(8)=2.327; P=0.0484; Fig 5. C, E). Together these results suggest that Prax330 has a greater effect on Scn8aD/+ neurons with aberrant firing, potentially due to its effect on INaR and INaP, two currents that are known to contribute to burst firing and are increased in amplitude in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons.

Figure 5. Prax330 preferentially suppresses aberrant AP-bursting in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons.

A. Example traces for WT before (black) and after (green) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). B. Example traces for a low bursting Scn8aD/+ subiculum neuron before (blue) and after (red) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). C. Example traces for an aberrant bursting Scn8aD/+ subiculum neuron before (purple) and after (orange) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). Note that Prax330 (1μM) preferentially reduces AUC in Scn8aD/+-high bursting subiculum neurons (n=9 neurons, 7 mice) while having little effect on low bursting subiculum neurons (n=9 neurons, 7 mice), or WT neurons (17 neurons, 4 mice). D. Histogram of AUC data separated into Scn8aD/+-low (blue) and Scn8aD/+-high (purple) groups. E. Bar chart showing effects of Prax330 (1 μM) on AUC values. Data shown represent means and individual points before and after Prax330 treatment. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

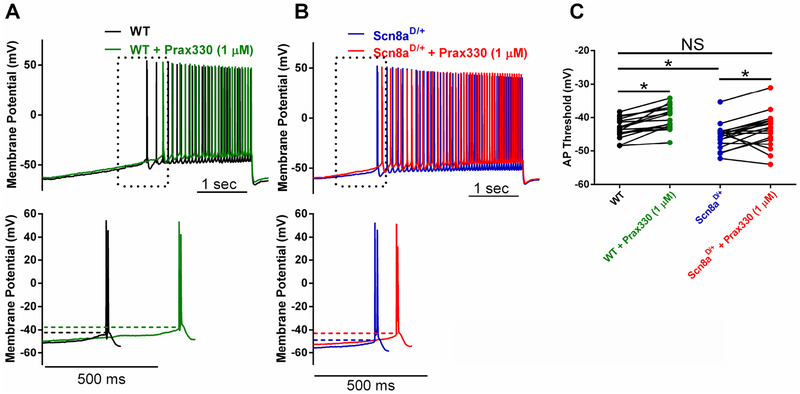

3.5. Prax330 rescues hyperpolarized AP thresholds in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons

Examination of membrane properties revealed that AP thresholds were significantly hyperpolarized in Scn8aD/+ (−45.6 ± 0.9 mV; n=18, 7 mice) compared to WT mice (−43.2 ± 0.7 mV; n=17 neurons, 4 mice; T(33)=2.096; P=0.0438; Fig 6. A–C; Table 2). Notably, Prax330 (1μM) depolarized the threshold voltages in Scn8aD/+ neurons to voltages observed in WT neurons, thus rescuing a critical determinant of neuronal excitability. Neither resting membrane potential (WT; −63.9 ± 0.6 mV, Scn8aD/+; −62.9 ± 0.6 mV) nor membrane capacitance (WT; 37.9 ± 5.1 pF, Scn8aD/+ 48.5 ± 4.7 pF) were different between WT and Scn8aD/+ neurons. AP amplitude and upstroke velocity were also not different between WT and Scn8aD/+neurons, but were reduced in response to Prax330 (1μM) for both genotypes, as expected for a Na channel blocker (Table 2). Surprisingly, we observed an increase in input resistance in Scn8aD/+ neurons after Prax330 treatment (Table 2). Differences observed in rheobase, downstroke velocity, and APD50 between Scn8aD/+ and WT neurons were not modulated by Prax330 (Table 2).

Figure 6. Prax330 rescues hyperpolarized AP threshold in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons.

A-B. Representative raw traces with APs evoked using a slow current injection ramp (100 pA/sec). A. Top. WT subiculum neuron before (black) and after (green) Prax330 (1 μM) treatment. B. Top. Scn8aD/+ subiculum neuron before (blue) and after (red) treatment with Prax330 (1 μM). Lower panels in each case show expanded trace of first action potential. Dotted lines mark action potential threshold. C. Group data for action potential (AP) threshold for WT before (black) and after (green) treatment with 1 μM Prax330 (n= 17 neurons, 4 mice) and Scn8aD/+ before (blue) and after (red) treatment with 1 μM Prax330 (n=18 neurons, 7 mice). Data shown represents individual points before and after Prax330 treatment. *P<0.05.

TABLE 2.

Effect of Prax330 on passive and active membrane properties in WT and Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons.

| Threshold (mV) | Input Resistance (MΩ) | Rheobase (pA) | Amplitude (mV) | Upstroke Velocity (mV/ms) | Downstroke Velocity (mV/ms) | APD50 (ms) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | −43.2 ± 0.8 | 103 ± 7 | 213 ± 8 | 93.9 ± 1.9 | 335 ± 26 | −80 ± 2.9 | 1.05 ± 0.04 |

| + Prax330 (1 μM) | −40.1 ± 0.9* | 112 ± 9 | 214 ± 14 | 85.6 ± 2.8* | 277 ± 22** | −74 ± 4.6 | 1.11 ± 0.06 |

| Scn8aD/+ | −46.2 ± 0.6# | 153 ± 17# | 101 ± 8 | 96.2 ± 2.4 | 336 ± 15 | −56.3 ± 2.9# | 1.37 ± 0.08# |

| + Prax330 (1μM) | −43.6 ± 1.2* | 147 ± 24 | 128 ± 11* | 90.9 ± 1.9* | 278 ± 15* | −58.4 ± 3.6 | 1.40 ± 0.11 |

indicates p<0.05 comparing within cell (before and after Prax330 application) using paired t-test.

indicates p<0.05 comparing WT and Scn8aD/+ groups using unpaired t-test.

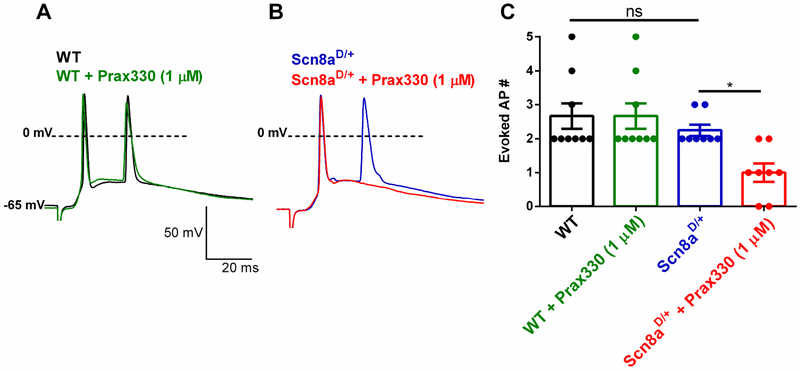

3.6. Prax330 reduces synaptically-evoked APs in Scn8aD/+ but not WT neurons.

INaP currents strongly regulate the propensity for a neuron to initiate an AP in response to incoming synaptic excitation by amplifying synaptic inputs from dendrites (Schwindt and Crill, 1995; Stuart, 1999). Due to effects of Prax330 on INaP, we examined the ability of Prax330 to modulate synaptically-evoked APs. In WT neurons (n= 9, 4 mice) Prax330 (1 μM) had no effect on synaptically evoked APs (Fig 7. A,C). In striking contrast, Prax330 (1 μM) significantly reduced the number of synaptically-evoked APs from Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons (n= 8, 4 mice; T(7)=3.149; P=0.0162; Fig 7. B, C). This effect of Prax330 would significantly dampen the increased network excitability associated with SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy (Ottolini et al., 2017).

Figure 7. Prax330 reduces the number of synaptically-evoked burst APs in Scn8aD/+ but not WT subiculum neurons.

A. Representative traces of WT (baseline, black; Prax330 (1 μM), green) demonstrates that Prax330 has no effect on the number of WT synaptically-evoked APs. B. Example traces of Scn8aD/+ (baseline, blue; Prax330 (1 μM), red) demonstrates that Prax330 diminishes the number of Scn8aD/+ synaptically-evoked APs. C. Bar chart demonstrating effects of Prax330 (1 μM) on WT and Scn8aD/+ synaptically-evoked APs (n=9 neurons from 4 WT mice and n=8 neurons from 4 Scn8aD/+ mice). Data shown represent individual points and means ± S.E.M. *P<0.05.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that 1) subiculum neurons from a mouse knock-in model expressing the patient mutation N1768D (Scn8aD/+) have pro-excitatory firing properties with elevated INaP and INaR Na channel currents compared to WT littermates, 2) Prax330, a Na channel inhibitor, modulates inactivation parameters of WT and N1768D NaV1.6 currents, causing hyperpolarizing shifts in inactivation parameters and inhibiting INaP observed in N1768D cells, 3) in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons in situ, Prax330 reduces INaP and INaR and selectively suppresses abnormal burst-firing only in high-bursting neurons. These specific effects of Prax330 on Na channel currents, particularly its ability to suppress INaP and INaR, could account for its ability to specifically target abnormally large AP bursts in a subset of Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons, while having little effect on normal bursting Scn8aD/+ neurons or WT neurons, and for its anticonvulsant activity in Scn8aD/+ mice (Baker et al., 2018).

Elevated INaP has been implicated in facilitating neuronal hyperexcitability associated with epilepsy. Many gain-of-function mutations in NaV1.1, NaV1.2, NaV1.3, and NaV1.6 display an increased INaP (Blanchard et al., 2015; de Kovel et al., 2014; George, 2004; Holland et al., 2008; Liao et al., 2010; Ottolini et al., 2017; Rhodes et al., 2004; Veeramah et al., 2012; Wagnon and Meisler, 2015; Zaman et al., 2018). Increased INaP has been reported in animal models of temporal lobe epilepsy and in human epilepsy patients (Agrawal et al., 2003; Barker et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2011; Hargus et al., 2013; Stafstrom, 2007; Vreugdenhil et al., 2004). Increased INaP induces aberrant neuronal excitability, producing large burst AP events, leading to seizures in rodents (Alkadhi and Tian, 1996; Mantegazza et al., 1998; Otoom et al., 2006; Otoom and Alkadhi, 2000), and suppression of INaP by AEDs is considered an important mechanism of action (Stafstrom, 2007). Consistent with these observations, preferential inhibitors of INaP have shown promise in animal models of epilepsy (Anderson et al., 2014; Romettino et al., 1991; Urbani and Belluzzi, 2000). Prax330 was originally developed as an antiarrhythmic drug due to its ability to target INaP generated by the cardiac Na channel, Nav1.5 (Belardinelli et al., 2013; Potet et al., 2016; Sicouri et al., 2013). In this study, we demonstrate that Prax330 is a potent inhibitor of neuronal INaP, with effects not only on the mutant Nav1.6-N1768D channel expressed in a neuron-derived cell line, but also on subiculum neurons in situ. Since INaP is thought to provide sustained depolarization after an initiated AP and amplify synaptic inputs from distal dendrites to facilitate repetitive and/or burst-firing of APs, suppression of these currents is predicted to suppress epileptiform burst firing (Harvey et al., 2006; Schwindt and Crill, 1995; Stuart, 1999; Stuart and Sakmann, 1995; Yamada-Hanff and Bean, 2013). In agreement with this prediction, Prax330 normalized the AP-burst waveform in Scn8aD/+ CA1 pyramidal neurons without an effect on WT AP firing (Baker et al., 2018). Here we show that Prax330 is particularly effective at modulating subiculum neurons with large, abnormal AP waveforms, and has little effect on APs that did not display epileptiform morphology. We suggest that these aberrantly firing neurons likely exhibited larger INaP and/or INaR currents, accounting for their sustained depolarization and prolonged neuronal excitation. Selective inhibition of epileptiform neurons enhances the therapeutic potential of Prax330 and could reduce unwanted side effects.

The INaR is a slow inactivating depolarizing current that can contribute to increased AP frequency and burst firing by providing additional depolarization during the falling phase of an AP (Khaliq et al., 2003; Raman et al., 1997; Raman and Bean, 1997). Increases in INaR have been reported in animals models of epilepsy and are also considered therapeutic targets in epilepsy (Hargus et al., 2013; Jarecki et al., 2010; Khaliq et al., 2003; Patel et al., 2016). Here we show that Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons have elevated INaR that are suppressed by Prax330. Recent studies indicate that inhibition of INaR is an important mechanism of action of cannabidiol, a compound with promise in treating different types of epilepsy including genetic epilepsies (Devinsky et al., 2017, 2016; Kaplan et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2016). However, recent evidence suggests that cannabidiol also inhibits the transient sodium current making these studies inconclusive regarding the specific role of INaR in epilepsy (Ghovanloo et al., 2018). We evaluated the effects of Prax330 on subiculum neurons because they provide a major output from the hippocampus proper and are an important anatomical site affecting seizure initiation (Fujita et al., 2014; Toyoda et al., 2013). It has been proposed that synaptic connection from CA1 neurons to subiculum neurons is reorganized in epilepsy leading to increased excitation of subiculum neurons (Cavazos et al., 2004; de Guzman et al., 2006). Subiculum neurons from epileptic rodents have elevated INaP and INaR leading to hyperexcitability (Barker et al., 2017; de Guzman et al., 2006; Wellmer et al., 2002). Similarly, Vreugdenhil and colleagues demonstrated that INaP is elevated in a subset of subiculum neurons from human epilepsy patients (Vreugdenhil et al., 2004). Only a subset (~50 %) of the recorded neurons had elevated INaP, leading to the hypothesis of two distinct neuronal populations distinguished by INaP levels. Our data are consistent a similar heterogeneity in Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons.

Prax330 has shown efficacy in animal models of epileptic encephalopathy including the Scn1a+/−, Scn2aQ54, Scn8aD/+ and most recently the Scn8aR1872W/+ models of SCN8A encephalopathy, providing support for the view that disrupted inactivation of Na channels can contribute generally to epileptic encephalopathies (Anderson et al., 2017, 2014; Baker et al., 2018). The efficacy of Prax330 in the Scn1a+/− model of Dravet Syndrome with reduced Scn1a activity is surprising, and suggests that inhibiting NaV1.6 and associated INaP and INaR with Prax330 differentially impacts the excitability of pyramidal neurons and inhibitory interneurons (Anderson et al., 2017), potentially resetting the network imbalance. Alternatively, the mechanism could be indirect since chronic dosing with Prax330 was shown to reduced Nav1.6 protein expression (Anderson et al., 2017). The fact that Prax330 is efficacious in two distinct mouse models of epileptic encephalopathy highlights the uniqueness of Prax330 among other Na channel blockers and could be due to its preferential targeting of INaP and INaR over INaT. Further mechanistic studies are warranted to clarify the precise molecular mechanisms of Prax330.

5. Conclusion

Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons have elevated INaP and INaR currents which lead to abnormal burst-firing of APs and is likely to contribute to network hyperexcitability associated with seizure generation. In ND7/23 cells, we demonstrate that Prax330 is able to reduce INaP and modulate steady-state inactivation of NaV1.6 Na channel currents. In brain slice preparations, we show that Prax330 is able to block both INaP and INaR, to reduce the magnitude of AP bursting in neurons with abnormal AP burst waveforms, and to inhibit synaptically-evoked APs from Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons. Taken together, our data support efforts to develop new therapeutics that preferentially inhibit INaP and INaR currents. Development of candidate therapeutics with these characteristics could prove highly effective in the treatment of SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy and other types of epilepsy.

Highlights.

Patient mutation SCN8A-N1768D produces elevated persistent Na current that is inhibited by Prax330.

Pro-excitatory depolarizing shifts in N1768D steady-state inactivation curves are rescued by Prax330.

Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons expressing the N1768D mutation have elevated persistent and resurgent Na currents.

Prax330 attenuates both persistent and resurgent Na currents of Scn8aD/+ subiculum neurons.

Prax330 normalizes hyperpolarized threshold and suppresses aberrant bursting in Scn8aD/+ neurons.

Prax330 reduces synaptically-evoked action potentials in neurons from Scn8aD/+, but not WT, mice.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dr. Miriam Meisler for providing the Scn8aD/+ mutant mice and the N1768D clone and for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant (NINDS) R01NS103090 to MKP, and University of Virginia’s Robert R. Wagner Fellowship to ERW.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest

MKP has received prior support from Praxis Precision Medicines. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest. We confirm that we have read the ethical guidelines supplied by the Journal and that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Abbreviations:

- Na

Sodium

- INaT

Transient current

- INaP

Persistent Sodium Current

- INaR

Resurgent Sodium Current

- AIS

Axon initial segment

- AP

Action potential

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Agrawal N, Alonso A, Ragsdale DS, 2003. Increased Persistent Sodium Currents in Rat Entorhinal Cortex Layer V Neurons in a Post-Status Epilepticus Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.23103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander A, Huguenard J, 2014. Lamotrigine suppresses thalamic epileptiform oscillations via a blockade of the persistent sodium current. Epilepsy Curr. [Google Scholar]

- Alkadhi KA, Tian LM, 1996. Veratridine-enhanced persistent sodium current induces bursting in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuroscience. 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00488-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LL, Hawkins NA, Thompson CH, Kearney JA, George AL, 2017. Unexpected Efficacy of a Novel Sodium Channel Modulator in Dravet Syndrome. Sci. Rep 10.1038/s41598-017-01851-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LL, Thompson CH, Hawkins NA, Nath RD, Petersohn AA, Rajamani S, Bush WS, Frankel WN, Vanoye CG, Kearney JA, George AL Jr, George AL, 2014. Antiepileptic Activity of Preferential Inhibitors of Persistent Sodium Current. Epilepsia 55, 1274–1283. 10.1111/epi.12657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EM, Thompson CH, Hawkins NA, Wagnon JL, Wengert ER, Patel MK, George AL, Meisler MH, Kearney JA, 2018. The novel sodium channel modulator GS-458967 (GS967) is an effective treatment in a mouse model of SCN8A encephalopathy. Epilepsia 59, 1166–1176. 10.1111/epi.14196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker BS, Nigam A, Ottolini M, Gaykema RP, Hargus NJ, Patel MK, 2017. Pro-excitatory alterations in sodium channel activity facilitate subiculum neuron hyperexcitability in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker BS, Ottolini M, Wagnon JL, Hollander RM, Meisler MH, Patel MK, 2016. The SCN8A encephalopathy mutation p.Ile1327Val displays elevated sensitivity to the anticonvulsant phenytoin. Epilepsia. 10.1111/epi.13461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardinelli L, Liu G, Smith-Maxwell C, Wang W-Q, El-Bizri N, Hirakawa R, Karpinski S, Hong Li C, Hu L, Li X-J, Crumb W, Wu L, Koltun D, Zablocki J, Yao L, Dhalla AK, Rajamani S, Shryock JC, 2013. A Novel, Potent, and Selective Inhibitor of Cardiac Late Sodium Current Suppresses Experimental Arrhythmias. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 10.1124/jpet.112.198887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard MG, Willemsen MH, Walker JB, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG, Jongmans MCJ,Kleefstra T, van de Warrenburg BP, Praamstra P, Nicolai J, Yntema HG, Bindels RJM, Meisler MH, Kamsteeg EJ, 2015. De novo gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutations of SCN8A in patients with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy. J. Med. Genet 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld H, Lampert A, Klein JP, Mission J, Chen MC, Rivera M, Dib-Hajj S, Brennan AR, Hains BC, Waxman SG, 2009. Role of hippocampal sodium channel Nav1.6 in kindling epileptogenesis. Epilepsia. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01710.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunton-Stasyshyn RKA, Wagnon JL, Wengert ER, Barker BS, Faulkner A, Wagley PK, Bhatia K, Jones JM, Maniaci MR, Parent JM, Goodkin HP, Patel MK, Meisler MH, 2019. Prominent role of forebrain excitatory neurons in SCN8A encephalopathy. Brain awy324–awy324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JH, Schaller KL, Lasher RS, Peles E, Levinson SR, 2000. Sodium channel Nav1.6 is localized at nodes of Ranvier, dendrites, and synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 10.1073/pnas.090034797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos JE, Jones SM, Cross DJ, 2004. Sprouting and synaptic reorganization in the subiculum and CA1 region of the hippocampus in acute and chronic models of partial-onset epilepsy. Neuroscience. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Su H, Yue C, Remy S, Royeck M, Sochivko D, Opitz T, Beck H, Yaari Y, 2011. . An increase in persistent sodium current contributes to intrinsic neuronal bursting after status epilepticus. J. Neurophysiol 10.1152/jn.00184.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo E, Franceschetti S, Avanzini G, Mantegazza M, 2013. Phenytoin Inhibits the Persistent Sodium Current in Neocortical Neurons by Modifying Its Inactivation Properties. PLoS One. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Guzman P, Inaba Y, Biagini G, Baldelli E, Mollinari C, Merlo D, Avoli M, 2006. Subiculum network excitability is increased in a rodent model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Hippocampus. 10.1002/hipo.20215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kovel CGF, Meisler MH, Brilstra EH, van Berkestijn FMC, Slot R van t., van Lieshout S, Nijman IJ, O’Brien JE, Hammer MF, Estacion M, Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj SD, Koeleman BPC, 2014. Characterization of a de novo SCN8A mutation in a patient with epileptic encephalopathy. Epilepsy Res. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2014.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng PY, Klyachko VA, 2016. Increased Persistent Sodium Current Causes Neuronal Hyperexcitability in the Entorhinal Cortex of Fmr1 Knockout Mice. Cell Rep 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O, Cross JH, Laux L, Marsh E, Miller I, Nabbout R, Scheffer IE, Thiele EA, Wright S 2017. Trial of Cannabidiol for Drug-Resistant Seizures in the Dravet Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med 376, 2011–2020. 10.1056/NEJMoa1611618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O, Marsh E, Friedman D, Thiele E, Laux L, Sullivan J, Miller I, Flamini R, Wilfong A, Filloux F, Wong M, Tilton N, Bruno P, Bluvstein J, Hedlund J, Kamens R, Maclean J, Nangia S, Singhal NS, Wilson CA, Patel A, Cilio MR, 2016. Cannabidiol in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy: an open-label interventional trial. Lancet Neurol. 15, 270–278. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00379-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H-W, Ennis M, 2014. Activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors enhances persistent sodium current and rhythmic bursting in main olfactory bulb external tufted cells. J. Neurophysiol 10.1152/jn.00696.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duflocq A, Le Bras B, Bullier E, Couraud F, Davenne M, 2008. Nav1.1 is predominantly expressed in nodes of Ranvier and axon initial segments. Mol. Cell. Neurosci 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estacion M, O’Brien JE, Conravey A, Hammer MF, Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj SD, Meisler MH, 2014. A novel de novo mutation of SCN8A (Nav1.6) with enhanced channel activation in a child with epileptic encephalopathy. Neurobiol. Dis 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S, Toyoda I, Thamattoor AK, Buckmaster PS, 2014. Preictal Activity of Subicular, CA1, and Dentate Gyrus Principal Neurons in the Dorsal Hippocampus before Spontaneous Seizures in a Rat Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. J. Neurosci 34, 16671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George AL, 2004. Molecular basis of inherited epilepsy. Arch. Neurol 10.1001/archneur.61.4.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghovanloo M-R, Shuart NG, Mezeyova J, Dean RA, Ruben PC, Goodchild SJ, 2018. Inhibitory effects of cannabidiol on voltage-dependent sodium currents. J. Biol. Chem 293, 16546–16558. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie JB, Pearce RA, 2006. Active and Passive Membrane Properties and Intrinsic Kinetics Shape Synaptic Inhibition in Hippocampal CA1 Pyramidal Neurons. J. Neurosci 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0547-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargus NJ, Nigam A, Bertram EH, Patel MK, 2013. Evidence for a role of Nav1.6 in facilitating increases in neuronal hyperexcitability during epileptogenesis. J. Neurophysiol 110, 1144–1157. 10.1152/jn.00383.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargus NJ, Nigam A, Bertram EH Iii, Patel MK, n.d. Evidence for a role of Na v 1.6 in facilitating increases in neuronal hyperexcitability during epileptogenesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Harvey PJ, Li Y., Li X, Bennett DJ, 2006. Persistent Sodium Currents and Repetitive Firing in Motoneurons of the Sacrocaudal Spinal Cord of Adult Rats. J. Neurophysiol 96, 1141–1157. 10.1152/jn.00335.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland KD, Kearney JA, Glauser TA, Buck G, Keddache M, Blankston JR, Glaaser IW, Kass RS, Meisler MH, 2008. Mutation of sodium channel SCN3A in a patient with cryptogenic pediatric partial epilepsy. Neurosci. Lett 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.12.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Tian C, Li T, Yang M, Hou H, Shu Y, 2009. Distinct contributions of Na v 1.6 and Na v 1.2 in action potential initiation and backpropagation. Nat. Publ. Gr 12 10.1038/nn.2359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarecki BW, Piekarz AD, Jackson JO II, Cummins TR, 2010. Human voltage-gated sodium channel mutations that cause inherited neuronal and muscle channelopathies increase resurgent sodium currents. J. Clin. Invest 120, 369–378. 10.1172/JCI40801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JS, Stella N, Catterall WA, Westenbroek RE, 2017. Cannabidiol attenuates seizures and social deficits in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 114, 11229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaliq ZM, Gouwens NW, Raman IM, 2003. The Contribution of Resurgent Sodium Current to High-Frequency Firing in Purkinje Neurons: An Experimental and Modeling Study. J. Neurosci 23, 4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AA, Shekh-Ahmad T, Khalil A, Walker MC, Ali AB, 2018. Cannabidiol exerts antiepileptic effects by restoring hippocampal interneuron functions in a temporal lobe epilepsy model. Br. J. Pharmacol 10.1111/bph.14202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltun DO, Parkhill EQ, Elzein E, Kobayashi T, Notte GT, Kalla R, Jiang RH, Li X, Perry TD, Avila B, Wang WQ, Smith-Maxwell C, Dhalla AK, Rajamani S, Stafford B, Tang J, Mollova N, Belardinelli L, Zablocki JA, 2016. Discovery of triazolopyridine GS-458967, a late sodium current inhibitor (Late INai) of the cardiac NaV 1.5 channel with improved efficacy and potency relative to ranolazine. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.03.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen J, Carvill GL, Gardella E, Kluger G, Schmiedel G, Barisic N, Depienne C, Brilstra E, Mang Y, Nielsen JEK, Kirkpatrick M, Goudie D, Goldman R, Jähn JA, Jepsen B, Gill D, Döcker M, Biskup S, McMahon JM, Koeleman B, Harris M, Braun K, de Kovel CGF, Marini C, Specchio N, Djémié T, Weckhuysen S, Tommerup N, Troncoso M, Troncoso L, Bevot A, Wolff M, Hjalgrim H, Guerrini R, Scheffer IE, Mefford HC, Møller RSP, ‡On behalf of the EuroEPINOMICS R E S Consortium C R, 2015. The phenotypic spectrum of SCN8A encephalopathy. Neurology 84, 480–489. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Anttonen AK, Liukkonen E, Gaily E, Maljevic S, Schubert S, Bellan-Koch A, Petrou S, Ahonen VE, Lerche H, Lehesjoki AE, 2010. SCN2A mutation associated with neonatal epilepsy, late-onset episodic ataxia, myoclonus, and pain. Neurology. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f8812e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Santiago LF, Yuan Y, Wagnon JL, Hull JM, Frasier CR, O’Malley HA, Meisler MH, Isom LL, 2017. Neuronal hyperexcitability in a mouse model of SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 10.1073/pnas.1616821114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantegazza M, Franceschetti S, Avanzini G, 1998. Anemone toxin (ATX II)-induced increase in persistent sodium current: effects on the firing properties of rat neocortical pyramidal neurones. J. Physiol 507, 105–116. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.105bu.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otoom SA, Alkadhi KA, 2000. Epileptiform activity of veratridine model in rat brain slices: effects of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Res. 38, 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otoom SA, Handu SS, Wazir JF, James H, Sharma PR, Hasan ZA, Sequeira RP, 2006. Veratridine-induced wet dog shake behaviour and apoptosis in rat hippocampus. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_339.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottolini M, Barker BS, Gaykema RP, Meisler MH, Patel MK, 2017. Aberrant Sodium Channel Currents and Hyperexcitability of Medial Entorhinal Cortex Neurons in a Mouse Model of SCN8A Encephalopathy. J. Neurosci 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2709-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RR, Barbosa C, Brustovetsky T, Brustovetsky N, Cummins TR, 2016. Aberrant epilepsy-associated mutant Nav1.6 sodium channel activity can be targeted with cannabidiol. Brain. 10.1093/brain/aww129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JFR, Abdala APL, Koizumi H, Smith JC, St-John WM, 2006. Respiratory rhythm generation during gasping depends on persistent sodium current. Nat. Neurosci 10.1038/nn1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potet F, Vanoye CG, George AL, 2016. Use-Dependent Block of Human Cardiac Sodium Channels by GS967. Mol. Pharmacol 10.1124/mol.116.103358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman IM, Bean BP, 1997. Resurgent Sodium Current and Action Potential Formation in Dissociated Cerebellar Purkinje Neurons. J. Neurosci 17, 4517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman IM, Sprunger LK, Meisler MH, Bean BP, 1997. Altered subthreshold sodium currents and disrupted firing patterns in Purkinje neurons of Scn8a mutant mice. Neuron. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80969-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes TH, Lossin C, Vanoye CG, Wang DW, George AL, 2004. Noninactivating voltage-gated sodium channels in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 101, 11147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romettino S, Lazdunski M, Gottesmann C, 1991. ee ar Eur. J. Pharmacol 199, 371–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royeck M, Horstmann M-T, Remy S, Reitze M, Yaari Y, Beck H, 2008. Role of Axonal NaV1.6 Sodium Channels in Action Potential Initiation of CA1 Pyramidal Neurons. J. Neurophysiol 10.1152/jn.90332.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwindt PC, Crill WE, 1995. Amplification of Synaptic Current by Persistent Sodium Conductance in Apical Dendrite of Neocortical Neurons. JOURNAL OF NEUROPHYSIOLOGY RAPID Publ. 74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal MM, Douglas AF, 1997. Late Sodium Channel Openings Underlying Epileptiform Activity Are Preferentially Diminished by the Anticonvulsant Phenytoin. J. Neurophysiol 77, 3021–3034. 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicouri S, Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, 2013. Antiarrhythmic effects of the highly selective late sodium channel current blocker GS-458967. Hear. Rhythm 10, 1036–1043. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadoni F, Hainsworth AH, Mercuri NB, Caputi L, Martella G, Lavaroni F, Bernardi G, Stefani A, 2002. Lamotrigine derivatives and riluzole inhibit INa,P in cortical neurons. Neuroreport. 10.1097/00001756-200207020-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom CE, 2007. Persistent Sodium Current and Its Role in Epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2007.00156.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom CE, 2005. The Role of the Subiculum in Epilepsy and Epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Curr. 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2005.00049.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom CE, Schwindt PC, Chubb MC, Grill WE, 1985. Properties of Penistent Sodium Conductance and Calcium Conductance of Layer V Neurons From Cat Sensorimotor Cortex In Vitro. J. Neurophysiol, 53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, 1999. Voltage–activated sodium channels amplify inhibition in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Nat. Neurosci 2, 144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Sakmann B, 1995. Amplification of EPSPs by axosomatic sodium channels in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90095-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H, Alroy G, Kirson ED, Yaari Y, 2001. Extracellular Calcium Modulates Persistent Sodium Current-Dependent Burst-Firing in Hippocampal Pyramidal Neurons. J. Neurosci 21, 4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun GC, Werkman TR, Battefeld A, Clare JJ, Wadman WJ, 2007. Carbamazepine and topiramate modulation of transient and persistent sodium currents studied in HEK293 cells expressing the Nav1.3 α-subunit. Epilepsia. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazerart S, Vinay L, Brocard F, 2008. The Persistent Sodium Current Generates Pacemaker Activities in the Central Pattern Generator for Locomotion and Regulates the Locomotor Rhythm. J. Neurosci 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1437-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda I, Bower MR, Leyva F, Buckmaster PS, 2013. Early Activation of Ventral Hippocampus and Subiculum during Spontaneous Seizures in a Rat Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. J. Neurosci 33, 11100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryba AK, Kaczorowski CC, Ben-Mabrouk F, Elsen FP, Lew SM, Marcuccilli CJ, 2011. Rhythmic intrinsic bursting neurons in human neocortex obtained from pediatric patients with epilepsy. Eur. J. Neurosci 34 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruyama K, Hsiao C-F, Chandler SH, 2013. Participation of a persistent sodium current and calcium-activated nonspecific cationic current to burst generation in trigeminal principal sensory neurons. J. Neurophysiol 10.1152/jn.00410.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbani A, Belluzzi O, 2000. Riluzole inhibits the persistent sodium current in mammalian CNS neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00242.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeramah KR, O’Brien JE, Meisler MH, Cheng X, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG, Talwar D, Girirajan S, Eichler EE, Restifo LL, Erickson RP, Hammer MF, 2012. De novo pathogenic SCN8A mutation identified by whole-genome sequencing of a family quartet affected by infantile epileptic encephalopathy and SUDEP. Am. J. Hum. Genet 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreugdenhil M, Hoogland G, Van Veelen CWM, Wadman WJ, 2004. Persistent sodium current in subicular neurons isolated from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Eur. J. Neurosci 19, 2769–2778. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagnon JL, Barker BS, Hounshell JA, Haaxma CA, Shealy A, Moss T, Parikh S, Messer RD, Patel MK, Meisler MH, 2016. Pathogenic mechanism of recurrent mutations of SCN8A in epileptic encephalopathy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol 10.1002/acn3.276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagnon JL, Meisler MH, 2015. Recurrent and non-recurrent mutations of SCN8A in epileptic encephalopathy. Front. Neurol 10.3389/fneur.2015.00104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagnon JL, Mencacci NE, Barker BS, Wengert ER, Bhatia KP, Balint B, Carecchio M, Wood NW, Patel MK, Meisler MH, 2018. Partial loss-of-function of sodium channel SCN8A in familial isolated myoclonus. Hum. Mutat 10.1002/humu.23547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellmer J, Su H, Beck H, Yaari Y, 2002. Long-lasting modification of intrinsic discharge properties in subicular neurons following status epilepticus. Eur. J. Neurosci 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada-Hanff J, Bean BP, 2013. Persistent Sodium Current Drives Conditional Pacemaking in CA1 Pyramidal Neurons under Muscarinic Stimulation. J. Neurosci 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0577-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanishi T, Koizumi H, Navarro MA, Milescu LS, Smith JC, 2018. Kinetic properties of persistent Na + current orchestrate oscillatory bursting in respiratory neurons. J. Gen. Physiol 10.1085/jgp.201812100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman T, Helbig I, Božović IB, DeBrosse SD, Bergqvist AC, Wallis K, Medne L, Maver A, Peterlin B, Helbig KL, Zhang X, Goldberg EM, 2018. Mutations in SCN3A cause early infantile epileptic encephalopathy. Ann. Neurol 83, 703–717. 10.1002/ana.25188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong G, Masino MA, Harris-Warrick RM, 2007. Persistent Sodium Currents Participate in Fictive Locomotion Generation in Neonatal Mouse Spinal Cord. J. Neurosci 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0124-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]