Abstract

Greater male partner involvement in PMTCT and EID is associated with improved outcomes. Perceived low social support for the mother can negatively impact the uptake of PMTCT/EID service. Most research relies on women’s reports of the types and quality of male partner support received versus what is desired. This qualitative study examines reported social support provision pre- and post-partum of HIV+ Kenyan male partners from their own perspective. The study was embedded within a randomized control trial in Kenya designed to evaluate a PMTCT module of a web based system to improve EID. Focus groups were conducted with male partners of pregnant women with HIV and elicited feedback on male partner involvement in maternal and child care and factors affecting participation. Interviews were analyzed within a theoretical social support framework. Participants described providing tangible support (financial resources), informational support (appointment reminders) and emotional support (stress alleviation in the face of HIV+ related adversity). African conceptualizations of masculinity and gender norms influenced the types of support provided. Challenges included economic hardship, insufficient social support from providers, peers and bosses, and HIV stigma. Collaboration among providers, mothers and partners, a community-based social support system and recasting notions of traditional masculinity were identified as ways to foster male partner support.

Keywords: PMTCT, EID, Social support, male engagement, masculinity, Kenya

Introduction

Research shows that greater male involvement in Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) and Early Infant Diagnosis (EID) is associated with reduced rates of HIV transmission, loss to follow up, and infant mortality, along with increased retention in care (1-4). Women whose partners attend voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) are three times more likely to use Nevirapine prophylaxis and six times more likely to adhere to their chosen infant feeding method (3, 5-8). The inclusion of male partners in PMTCT and EID has thus been encouraged and acknowledged as critical to the increased uptake of services (5, 9).

However, male partner involvement in PMTCT and EID remains low (10-13). Using the proportion of male partners who undergo VCT when their female partners are pregnant or breastfeeding as a surrogate measure of male involvement in PMTCT (1, 2), studies across sub-Saharan Africa have found male participation in VCT to range from 5%-33% (3). In Kenya, uptake of male partner VCT was about 15% (1), indicating a significant gap in male involvement in PMTCT.

Barriers and facilitators for male participation in PMTCT

In sub-Saharan Africa, including Kenya, male involvement in PMTCT and EID is shaped by norms of support provision during pregnancy and postpartum. In a systematic review of the literature on male involvement in PMTCT, barriers were discussed in 85.7% of the studies (14). Cultural, traditional, religious and other contextual barriers to involvement in PMTCT identified include male fear of social ridicule for participation in a female-oriented activity, cultural communication patterns (15), financial burden, disagreement with teachings, time constraints, and perceived “male unfriendliness” of PMTCT services (14, 16-18). Constructs of masculinity (risk-taking, competitiveness, financial independence, stoicism, dominance) have also been identified as potential barriers to HIV-related care seeking among men (19, 20) and may also impact men’s willingness to attend PMTCT with their partner (16, 21). Although interventions facilitating male involvement in antenatal care (ANC) and PMTCT have been explored (22-26), it is not well understood how African cultural constructs of masculinity and fatherhood can be used to encourage male involvement in PMTCT and EID.

Male partner social support in the context of PMTCT and EID

To better engage men in supporting their partners during PMTCT and EID, Maman et al (5) called for a broader understanding of the types of social support male partners provide pre/postpartum beyond male attendance at clinics and uptake of HIV testing. Social support is a multidimensional construct referring to the “psychological and material resources available to individuals through their interpersonal relationships.” (27) Social support can be instrumental/tangible (financial assistance, time, help with tasks), emotional (caring, empathy, concern), and informational (suggestion, advice, information). Social support has been associated with powerful health benefits for people living with HIV (PLWH) including less depression, adherence to medication, enhanced resilience, improved quality of life, and even slower progression of HIV disease (28-31). In the context of PMTCT and EID, perceived low social support for the mother can negatively impact the uptake of PMTCT services (24). Much of the research on the social support male partners provide their HIV-affected partners around pregnancy rely on women’s reports (5, 32-34). Few studies examine the role of male partners from their own perspective.

This study sought to understand the types of social support Kenyan men reported providing their HIV-positive partners. Focusing on the constructs of social support (emotional, instrumental, and informational), we describe the ways men report providing support to their partners pre- and postpartum, to better understand why many men continue to be disengaged in PMTCT, and identify ways to facilitate increased engagement. We also explore emergent themes surrounding concepts of African masculinity and fatherhood to suggest ways in which they can be leveraged to encourage men provide social support during PMTCT and EID.

Methods

This qualitative study was embedded within an NIH (R34MH107337) intervention development study in Kenya, designed to develop and pilot a PMTCT component of the HIV Infant Tracking System (HITSystem) - a web-based mHealth, system-level intervention designed to improve early infant diagnosis (EID) outcomes. Using electronic alerts to providers and SMS text messages to mothers, the new PMTCT component of the HITSystem 2.0 tracks pregnant women with HIV through their pregnancy to support appointment attendance, medication adherence, hospital delivery, and linkage to EID services. The larger study included four intervention sites in geographically and tribally distinct parts of Kenya. Qualitative data reported here was used to inform the development of the text messaging component of the HITSystem 2.0.

Participants and procedures

In August 2016, we conducted focus groups (n=3) with male partners of pregnant women with HIV at three of the planned HITSystem 2.0 intervention sites in the Western (W), Rift Valley (RV), and Coastal (C) regions of Kenya prior to implementation. Each focus group had 6-11 attendees. Participants who regularly accompanied their partners to their ANC appointments and as such were already engaged with the topic of PMTCT/EID were deliberately identified and recruited by study site coordinators to participate in focus groups as we felt they were best placed to provide insight on the types of support they provide their partners. The focus groups were designed to elicit feedback on male partner involvement in PMTCT/EID and SMS content to encourage partner support pre- and postpartum. Focus groups were scheduled on designated PMTCT clinic days to minimize transportation cost. Focus groups were held in quiet and private spaces and lasted about 90 minutes. All participants provided written informed consent and received 400 Kenya shillings (4 US dollars).

Focus groups were conducted in Kiswahili by researchers trained in qualitative research methods. Male partners were asked about the needs of women with HIV during the antenatal and postpartum period, the PMTCT and EID process, their role in providing support to their partner, and their thoughts on the use of motivational text messages to support appointment adherence, medication adherence, and hospital-based delivery. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC).

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio recorded and translated and transcribed. An initial codebook was developed using a social support theoretical framework. Transcripts were coded independently by two study team members for a priori and emergent themes. Transcript coding was an iterative process with cross-questioning and critique between the coders. A final codebook included themes that emerged within the social support framework (informational, emotional and instrumental support), masculinity and other emergent categories. Exemplars for each theme were noted as well as the frequency and distribution of themes within the larger topic areas.

Results

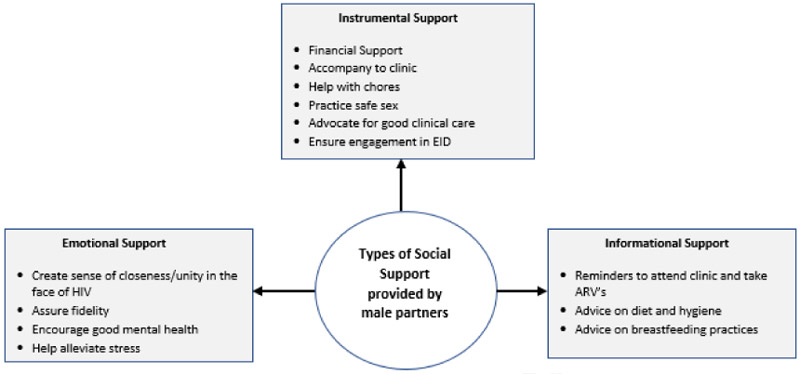

A total of 33 men from the Western (W), Rift Valley (RV), and Coastal (C) regions of Kenya participated in the focus groups. All men reported having some form of employment and had disclosed their status to their partners. All the men except one were in seroconcordant relationships. Figure 1. provides an overview of the types of social support male partners reported providing.

Figure 1:

Types of social support men reported providing to their partners with HIV

Provision of Social Support pre- and post-partum: Reported roles played by male participants

Throughout the pre- and post-partum period, some participants (P) used language suggesting the responsibility for following PMTCT/EID recommendations rested principally with the women, while other men emphasized their role in supporting and enabling women’s success in these efforts. Themes around the social support framework describe the male partners perceived and reported support roles as well as the barriers/challenges to providing that support and fulfilling self, partner, and societal expectations.

Provision of instrumental (tangible) support as key to fulfilling masculine role as head of household

Men felt their biggest role pre- and post-partum was instrumental (financial assistance, time given, help with tasks). The saliency of their masculine role as head of the household and main provider was evident in the types of instrumental support they reported providing. Provision of financial help was key for all participants, which included the provision of money for transportation to the hospital and meeting the mother’s nutritional needs during pregnancy:

“First we help them with money for coming to hospital… We mainly help them out financially, we help them with means of obtaining a good diet, things like those.“ (P4: RV)

This financial support also extended into the postpartum period in order to: (1) support the mother’s recovery post-delivery (2) provide nutritional support for infants unable to breastfeed, and (3) cover medication expenses to maintain adherence, “when [the mother] brings the pharmacy paper to buy the baby medication, then the father finds money and buys it” (P2: W).

Men understood clearly the responsibility to plan for the financial burdens that come with a pregnancy and newborn, and thus felt a strong need to find work:

“You asked what a man can do to help his spouse. It’s finding work. You find that due to the woman’s condition [pregnancy], he is the only one to find work, and must stay busy here and there." (P5: W)

They also indicated that even if they did not have the resources needed, they were still responsible for enlisting support from others:

“You must find a friend to help if you don’t have any [money], using any means. You use that money and she comes with [can get] medication. So, I say my friends we must try even when we can’t.” (P1: C)

“It’s important to have a number in case of trouble, so you can call if the neighbor has a car, because in the night it can be very expensive.” (P3: W)

Although men felt they must assume the burden of providing financial assistance, they also provided instrumental support by actively taking their partner to their antenatal appointments and to the hospital during delivery. Reasons participants noted for escorting their partner to antenatal visits included: (1) receiving quicker service, “when we came [on her clinic day], I don’t think we would stay even for half an hour, get seen and leave. But if she came alone, she would have to get in line” (P4:C), (2) ensuring retention of information provided, “mothers can get to the clinic, told they have a certain issue, and when they come home they give you a different problem. That is why doctors mostly insist you come as a husband and explain to your wife a-b-c-d.” (P2: C) and (3) ensuring women attend their appointments because, “some women are not honest, they don’t go to the clinic. You give them money they go elsewhere.” (P1: W)

Especially at the time of delivery, participants felt they could play a key role in advocating on their partner’s behalf to ensure they received appropriate care:

“You might find the wife has gone [to the hospital] and no one is attending to her, and will give birth there by herself. That is a challenge we face. So, you must find an attendant, and give her a tip so she can attend to your wife… When she arrives tell the attendant her [HIV positive] condition before so you help her as she gives birth. You might keep quiet and they will treat her like an ordinary patient.” (P1: C)

In addition to accompanying their partners to the hospital, participants also saw the importance of helping to create a good home environment pre- and post-partum by assisting with traditionally female activities such as household chores, “I return early to help her with household chores” (P2: W). Participants also took an active role in protecting their partner during pregnancy by practicing safe sex in order to increase the likelihood of the child being born HIV negative, “For example if it comes to sex… You see there can be a re-infection if I don’t take the necessary precautions like using a CD [condom]” (P2:RV).

Finally, participants agreed that it is their role post-partum to actively monitor both the baby and wife and to help the wife ensure their child’s health by engaging in EID:

“Starting from when the baby is young, you have to ensure the mother does not fail to come to the clinics. The baby has to be monitored and if the baby is using drugs, I have to make sure it is given drugs, even if the mother has not because all that will contribute to getting a negative baby… So if my wife has any challenge, I have to ensure we both participate so that she and the baby do not deteriorate.” (P2: RV)

“Nowadays even I can bring the baby to the hospital. Our eyes are opening; if my wife refuses to bring the child, I bring the child.” (P1: RV)

Provision of informational support to encourage partner engagement in recommended behavior

Participants also reported providing informational support to their partners to ensure they engaged in behaviors perceived as important based on clinical advice. Comments often suggested that participants felt knowledgeable enough to provide their partners with advice, even intimating that without this type of support their partners may not understand nor follow through with clinical advice. Participants saw it as their role to remind their partners to attend clinic:

“Because that is most important [attending clinic]. Because our main job is to protect the unborn child, so if we don’t remind her it will be doom.” (P2: W)

“I know my wife is positive and I am positive and I do not want to get a positive baby so everything I have [is] to focus on the baby. I have to completely coax her to come to the clinic even if she refuses.” (P1: RV)

Some comments suggested that male partners attended ANC appointments not only to support their partners but to ensure they do not withhold information from them, “You might stay at home and your partner is tested and found to be this way [HIV +], when she gets home she says it’s malaria… If your wife is sick go with her” (P5:C). At times, insistence on hospital attendance extended from mere advice to executive decision-making on the part of male partners, especially with regards to facility delivery given its clinical and financial significance:

“Considering our status [HIV +], I as the man will make the decision for the woman to go give birth in the hospital because in the hospital we will get a professional and if she gives birth in the village, most likely the baby being born will get the virus so I think the man should make the choice because it is him who will provide transport.” (P3: RV)

“I say us men we must be informed because there are some midwives who might be confused in the village. And maybe they might be late in the womb, and mom might have a problem. So we [men] must decide.” (P3: W)

Participants also reported advising their partners to maintain their diet and hygiene, including when to breastfeed or cease breastfeeding. Some participants framed the advice-giving as somewhat antagonistic, describing their partners as resistant or incapable of following the recommended behaviors without their male partner’s input:

“When she’s pregnant, the first thing we have to emphasize are diet and hygiene, it helps her a lot. Because you know when some are pregnant they don’t even shower, they are just lazy and sitting there. … You will find some taking advice lightly. Even when she is told, she does not want to follow instructions keenly. So sometimes we should also encourage them to follow instructions.” (P1: RV)

“Sometimes the baby wants to breastfeed a lot and as my friend said, the woman must breastfeed on demand… Sometimes she complains she does not have milk… So convincing her to breastfeed on demand is very hard but we come to agree with each other.” (P4: RV)

Discussions among participants suggested that if both the woman and her partner receive information it increases the likelihood of male partner support, “You must have collaboration. Everything that’s about to happen [both] the mother and father [need to] know, so the treatment that should be done is done… you must do things as one” (P2: W).

Provision of emotional support creating unity in the face of HIV

In addition to providing instrumental and informational support, men also understood they were responsible for supporting their partner’s emotional wellbeing, fulfilling pregnant women’s need for “plenty of love” by staying “close to her” and reducing stress by remaining “cool so they are moderate and relaxed.” However, participants recognized that some Kenyan men do not typically prioritize provision of this emotional support:

“You know not all men are the same, there are those with positive reactions, there are those who don’t care and considers that burden as the woman’s. But it is good you as a man to support the woman when she is in that [pregnant] state. She requires love, you need to show her that the burden belongs to both of you.” (P3: RV)

Another participant discussed the importance of providing emotional support to prevent depression during and after pregnancy particularly with the added burden of knowing one is HIV+:

“You know some have small [dark] thoughts after birth, so after birth just be close... I encourage you my brothers, when the mother is like that [depressed], follow up with her, because with this condition [HIV] without love, you won’t achieve anything. Because she’ll think her husband has left her.” (P2: W)

Beyond the general needs of pregnancy, participants stressed the importance of remembering the initial love that drew a couple together regardless of the stress that may arise once diagnosed as HIV+:

“For the mother to get pregnant, you’re usually in love with each other … Without love in the middle, it’s going to be difficult for the mother to raise the pregnancy well, so that’s why it’s very good for you as a man to be involved even more. So you just have to encourage her… God has blessed us with a pregnancy.” (P7: W)

Participants seemed to agree that the provision of emotional support was important to engender a sense of closeness, fidelity, and unity in the face of HIV, pre-and post-pregnancy:

“Most of the time, on my free time…I like mostly to be close to my wife. Because when we found out our status…that I am negative and she’s positive … she had a lot of stress. So I figured she’s probably thinking I am going to leave her, and run away…but I’ve continued to be with her like usual.” (P5: C)

Barriers to provision of social support pre- and post-partum

Participants shared the challenges they face fulfilling their roles as partner and head of the household pre- and post-partum.

Economic hardship as a barrier to fulfilling instrumental support role

An immediate source of concern for all the men was finances as limiting their ability to provide the types of instrumental support that they believed were needed, “Us as men, what challenges us the most is finances. You might find your wife is pregnant, and you have no work” (P2: W). The lack of: (1) steady employment opportunities, “You might have energy to work, but there is no work to be found” (P2: W), (2) understanding bosses:

“I was fired by my boss, the first time I had to go to the hospital and came back with a doctor’s note. It was not written HIV, but each month I need permission I was told not to work with a bad chest but my employer let me go” (P8: C)

and (3) flexible work situations, “Work situations do not allow him to be near his wife. And some bosses don’t allow, or don’t give a way…You would really love to be there, but situations don’t allow” (P5: W), were cited as the main sources of economic hardships.

Financial instability also impacted decisions participants made about the type of care to get for their partners including decisions about where to give birth, “So when a man sees he does not have enough money, he starts thinking about a midwife [traditional birth attendant]” (P5: W).

Limited provider/clinic options

Participants discussed the limited healthcare options they and their partners experienced and how that affected health seeking behaviors. Participants discussed their limited options in regard to the caliber of health care providers, many of whom they characterized as unsympathetic and possibly discriminatory because of their partner’s HIV+ status:

“If I add, when a mother is about to give birth…she must inform the sister [nurse] there, because when some see her card at the clinic written HIV, some refuse. So if they consult each other, she’s going to help her before birth. But when some see that name [HIV +] they get scared.” (P3: W)

Fear of disclosure and stigmatization

Participants discussed the potential of having their HIV+ status inadvertently disclosed as a barrier to engaging in EID/PMTCT. Participants discussed the lack of privacy in many clinics and the lack of adherence to confidentiality standards by providers that heightened the possibility of unintentional disclosure and thus exposure to stigma:

“What prevents men from accompanying their wife is attendants who are there. When you go together …and there are questions that require privacy. You find they [providers] want to ask you right there. You will be asked, be annoyed and will not return there again.” (P6: C)

This, coupled with men’s fear of discovering their HIV status, seemed to hinder men’s ability tosupport their partners in PMTCT/EID:

“Us men have a lot of fear about people knowing about our health…you find many men even coming to the clinic with their wife they refuse [testing], saying it’s for the mother. But I say what we have now, it’s not for the mother or father. Each person must know their status.” (P2: C)

Encouraging male support of EID/PMTCT

Recognizing that the men who chose to participate in the focus groups were already engaged in PMTCT and thus already motivated to engage in care, we asked them to recommend ways in which we could reach men who were not participating in PMTCT/EID. The following themes emerged.

Adopt an HIV+ identity

Participants discussed the importance of accepting their HIV+ diagnosis and the power in disclosing one’s status. Comments suggested adopting an HIV+ identity is empowering rather than diminishing as it allowed them to live their lives openly. They also encouraged each other to not only live positively but to support other men in putting their fears aside and finding out their status:

“For me, I cannot hide at home, so I would say do this; at the homestead, I tried to gather my close family and said…there was a problem [HIV] that was bothering me [that] I have gone through…This illness does not discriminate and affects anyone…Even if someone finds out, what will they do to me? I came to know that I am different from my friends, if I take medication I will be the same as my friends. But as you say your truth, you’ll live just like normal." (P1: C)

“But if you put fear aside, and know life will still continue, talk honestly without hiding, and that we should go together to know our status, that made things easy… among my friends, I have helped many. Each time we talk, I tell them you must know your status.” (P2: C)

Another participant to the enthusiastic agreement of the group proclaimed that men with HIV were in many ways better than negative men because the stakes for them and their family’s wellbeing were even higher and as such they had to work harder:

“Another thing I want to add, us men who have the virus are very hardworking…You work hard because you don’t want to sleep hungry, hard work so your family can stay well. Also you as a man who has a virus don’t want the one without the virus to overtake you…we have the urge to compete with those without the virus, and they can’t beat us.” (P6: W)

Employ “male focused” engagement strategies

Focus group participants seemed to appreciate the opportunity to share their experiences and thoughts with one another. Participants commented that such opportunities were rare as the focus of support provision and education is from their perspective heavily skewed towards mothers:

“For example, even these support groups, mostly if you go you’ll find mothers. And if you listen to the teachings, women disclose that their husbands have a problem. They have tried [to get them engaged in care], but nothing is working…He [her partner] started medication, but after a time, he says he’ll let things take their course.” (P1: C)

Participants intimated that without sustained social support, many male partners fall by the wayside and engage in detrimental behavior that compromises their health and that of their family. As such, participants suggested that male focused programing similar to what women receive, including support groups and/or “Mentor Father” programs, be provided to male partners:

“We would like the hospital to have sessions for men…aside [separate from women] where they can be taught the importance of coming with the woman to hospital or for them to just come and talk so that the men also know the importance because right now men do not know the importance.” (P3: RV)

“There should also be mentor fathers so when this father comes… they have someone to stand with them and know true reason they are coming. And to learn what instructions they need to follow.” (P4: RV)

Discussion

Given the recognized importance of social support, especially male partner social support, for PMTCT and EID uptake and retention (24), this study sought to understand the types of social support behaviors men provide their partners in the context of pre- and post-natal care and PMTCT/EID services. Studies on PMTCT/EID have examined male provision of social support from the perspective of female partners (5, 32-34) but the male perspective is lacking. By seeking the male perspective, we sought to better understand the types of social support behaviors most salient to men within the Kenyan cultural context, to examine how their overall perceptions of women’s pre- and postnatal needs translate into actual support, and to explore barriers and facilitators to male engagement.

Research indicates that in general men are supportive of their partners’ participation in PMTCT; (35, 36) however, a contradiction exists between their positive attitudes and participation rates in PMTCT/EID. This is attributed to cultural (concepts of male roles and African masculinity) (15,19,20), clinical (male unfriendly PMTCT services) (14) and economic barriers (financial constraints) (16, 17, 18). While much of the literature on African male engagement in PMTCT/EID casts African constructs of masculinity as a barrier to uptake and support provision where male involvement goes against prevailing gender norms, others see African conceptions of masculinity as playing a more diverse role depending on the context, acting as both a facilitator and a barrier to HIV service uptake (19, 39-42). Because traditional masculinity often identifies men in terms of their paternal responsibility in their role as fathers, providers and protectors of their families (19), this impacts not only how men engage in care seeking for themselves, but also for the care seeking of their families. Strong themes of male partner provision and leadership as head of household in this study are consistent with this traditional masculinity, especially in the realms of instrumental and informational support.

Similar to studies conducted with women reporting on the partner support they received, participants reported providing instrumental support through financial assistance, and by accompanying their partners to clinic appointments (5, 32, 34). Participants indicated that financial assistance pre- and post-pregnancy was the most salient type of support due to sociocultural expectations of the man as provider and of financial security as a key marker of success in the eyes of the community and family. For men with HIV, being able to provide for their families seemed to gain even more urgency. HIV+ participants suggested that in competing with and doing better than their HIV- counterparts they could claim an HIV+ identity that is respectable, superior and resilient, despite additional challenges such as stigma and discrimination. This shows how traditionally masculine traits such as competitiveness can be used to propel a man with HIV to exceed social expectations. This is consistent with other studies showing that while notions of reputational masculinity (authority over family, risky behavior) can sometimes undermine HIV service uptake, masculine notions of respectability (good provider and father, faithful) can also lead men to seek treatment to maintain their health to better provide for their families (37) In seeking respectability, Siu, Wight, and Seely (38) contend, HIV+ men can restore a masculinity dented by HIV infection.

However, the findings also demonstrate that male partners provide other types of social support that warrant similar emphasis, if not more, given that provision of financial support is not always possible and that other forms of support are needed to encourage sustained engagement in PMTCT/EID. Other forms of support reported by participants included providing instrumental support involving activities traditionally reserved for women in Kenya and other African countries, such as helping with household chores pre- and post-partum and caring for the child post-partum (15). Especially for HIV+ men, it can be argued that this willingness to take on “feminine” roles by participants supports their recasting of a masculine HIV+ identity that includes doing “whatever it takes” to ensure a healthy family. Providers and counsellors could use this framing in programing to increase male participation in PMTCT/EID by helping them see that the very act of their participation can help create a “resuscitated masculine” HIV+ identity (20). Emphasizing the importance of other types of instrumental support during PMTCT/EID other than financial can be an empowering strategy to help male partners affirm their masculine role as successful providers, despite their economic status.

Participants also reported supporting their partners by providing informational support. The provision of informational support depended on male partners being prepared to discuss subjects often thought as taboo such as safe sex practices, which are important to the uptake of PMTCT services, (15) but may also lead to uncomfortable discussions around fidelity. Participants indicated gender role shifts exemplified by their provision of informational advice in realms traditionally considered that of women, such as breastfeeding. However, participants often displayed a paternalistic approach to informational support that assumed a lack of capacity by their partners to understand clinical information and/or a lack of motivation in carrying out recommendations. This aligns with common male communication patterns in Kenya and has been argued may affect women’s real and perceived sense of agency in taking care of their health (15). However, if the informational support provided by partners reinforces provider advice, it may encourage positive behaviors by women engaged in PMTCT and EID services.

Participants also reported the provision of emotional support in ways that have not been previously discussed in the literature. Kenyan and other African men are often characterized as ascribing to hegemonic masculinity that includes toughness, stoicism and aversion to signs of weakness or vulnerability (43). Indeed, male denial of vulnerability and the construction of masculinity around power and strength and control has been found to contribute to health risk and gender based violence in South Africa (39, 43-45). However, participants in this study displayed an openness and vulnerability when discussing their partners that counters Kenyan/African notions of hegemonic masculinity. The language used by participants characterized the loving nature of many of their relationships despite the added complications of a HIV diagnosis and how emotional support was used to encourage a sustained engagement with the PMTCT/EID cascade of care. However, participants also noted that not all men are willing to provide emotional support during pregnancy.

Although possibly superficial, the attitudes and behaviors portrayed by the male partners in this study resonates with work on gender equality where men increasingly challenge “notions of masculinity that restrict their humanity, limit their participation in the lives of their children and put them and their partners at risk” (46). Participants seemed to agree that the first step to male engagement with EID/PMTCT is to get tested, as testing positive or knowing the status of one’s sexual partner is often the first step to identifying with HIV(47) and adopting an HIV+ identity; however, similar to the literature, (48) male partners wanted opportunities for greater male engagement beyond initial testing and linkage to care, citing their disappointment that support groups and mentor mother programs targeted towards women were not also available for men. The lack of such opportunities demonstrates a gap and insufficient recognition of the roles that fathers/partners play.

Identifying male partners like our participants who are willing to engage in care despite these cultural barriers, indeed, who are reshaping cultural expectations of male engagement, may be a first step in increasing male engagement and expanding the dimensions of male partner support to include a variety of instrumental, informational, and emotional support behaviors. Programs could strive to routinize the involvement of men and recast their role as agents who question and challenge gender norms that negatively affect the health of families. Additional goals following participant suggestions to reduce facility level barriers, could include: (1) addressing provider bias against male partners, (2) increasing male engagement, and (3) developing male support networks.

Barriers to greater male engagement due to economic hardship, caused by HIV related discrimination in the workplace also highlights the need to include men as part of broader programing that addresses economic opportunities. HIV prevention/intervention programs that address various levels of the socio-ecological model mostly target women particularly in regard to economic advancement in the form of microfinance development schemes. The strong desire by participants and other men like them to provide for their families as a fundamental part of their male role and HIV+ identity, could be used to frame economic programming targeting men.

Limitations

This study is limited by its relatively small sample size, with one focus group for each geographic region of Kenya (Western, Central, Coastal), thus limiting generalizability. Furthermore, participants in these focus group were men already engaged in their partner’s PMTCT and EID care and were men willing to engage in a group discussion about that engagement; thus, they likely represent an exception to common male partner perspectives on PMTCT and EID rather than normative perspective. In addition, although a focus group setting can stimulate discussion, it can also activate participants’ sense of social desirability, thus affecting their responses. It is also important to note that Kenya has diverse tribal cultures such that although men may generally ascribe to larger cultural conceptions of masculinity, there are variations in tribal conceptualizations that this study cannot account for. Findings are therefore not generalizable to all Kenyan men with HIV whose partners have gone through PMTCT and EID.

Conclusion

This study sought to understand the types of social support behaviors Kenyan men provide their partners in the context of pre- and post-natal care and PMTCT/EID services from the perspective of male partners themselves. Male partners highlighted their supportive roles in ways consistent with cultural conceptions of masculinity (financial provider, dominant decision maker) and in ways that reshape traditional notions of male engagement and challenged gender norms (home maker, caregiver). Cultural and contextual barriers to male engagement remain, including economic hardship, stigma and discrimination in the workplace and facility environments, as well as a general lack of support and opportunity for male engagement in PMTCT and EID services. Despite these challenges male partners expressed enthusiasm for strategies that provided them a space to engage. Promoting economic opportunities for male partners, expanding opportunities for male partner testing and linkage to HIV services, increasing provider awareness of the need for male engagement, and developing male support networks may help facilitate greater male partner engagement.

Acknowledgements

Funding disclosure: This work is supported by NIH R34MH107337. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: No potential conflicts exist for all authors.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Wachira J, Middlestadt SE, Vreeman R, Braitstein P. Factors underlying taking a child to HIV care: implications for reducing loss to follow-up among HIV-infected and-exposed children. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS. 2012;9(1):20–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aluisio A, Richardson BA, Bosire R, John-Stewart G, Mbori-Ngacha D, Farquhar C. Male antenatal attendance and HIV testing are associated with decreased infant HIV infection and increased HIV free survival. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2011;56(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aluisio AR, Bosire R, Bourke B, Gatuguta A, Kiarie JN, Nduati R, et al. Male Partner Participation in Antenatal Clinic Services is Associated With Improved HIV-Free Survival Among Infants in Nairobi, Kenya: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(2): 169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambia J, Mandala J. A systematic review of interventions to improve prevention of mother- to- child HIV transmission service delivery and promote retention. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2016;19(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maman S, Moodley D, Groves AK. Defining Male Support During and After Pregnancy from the Perspective of HIV-positive and HIV-negative Women in Durban, South Africa. Journal of midwifery & women's health. 2011;56(4):325–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turan JM, Miller S, Bukusi E, Sande J, Cohen C. HIV/AIDS and maternity care in Kenya: how fears of stigma and discrimination affect uptake and provision of labor and delivery services. AIDS care. 2008;20(8):938–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matovu S, Kirunda B, Rugamba-Kabagambe G, Tumwesigye N, Nuwaha F. Factors influencing adherence to exclusive breast feeding among HIV positive mothers in Kabarole district, Uganda. East African medical journal. 2008;85(4): 162–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibeko L, Coutsoudis A, Nzuza Sp, Gray-Donald K. Mothers’ infant feeding experiences: constraints and supports for optimal feeding in an HIV-impacted urban community in South Africa. Public health nutrition. 2009;12(11):1983–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Audet CM, Blevins M, Chire YM, Aliyu MH, Vaz EM, Antonio E, et al. Engagement of Men in Antenatal Care Services: Increased HIV Testing and Treatment Uptake in a Community Participatory Action Program in Mozambique. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(9):2090–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murithi LK, Masho SW, Vanderbilt AA. Factors enhancing utilization of and adherence to prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) service in an urban setting in Kenya. AIDS and behavior. 2015;19(4):645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osoti A, Han H, Kinuthia J, Farquhar C. Role of male partners in the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Research and Reports in Neonatology. 2014;4:131–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Msuya SE, Mbizvo E, Hussain A, Uriyo J, Sam N, Stray-Pedersen B. Low male partner participation in antenatal HIV counselling and testing in northern Tanzania: implications for preventive programs. AIDS care. 2008;20(6):700–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haile F, Brhan Y. Male partner involvements in PMTCT: a cross sectional study, Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014; 14:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manjate Cuco RM, Munguambe K, Bique Osman N, Degomme O, Temmerman M, Sidat MM. Male partners' involvement in prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission inrevie sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Sahara j. 2015;12:87–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frizelle K, Solomon V. Strengthening PMTCT through Communication. CADRE: Center for AIDS Development and Evaluation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morfaw F, Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L, Rodrigues C, Wunderlich AP, Nana P, et al. Male involvement in prevention programs of mother to child transmission of HIV: a systematic review to identify barriers and facilitators. Systematic reviews. 2013;2:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nanjala M, Wamalwa D. Determinants of male partner involvement in promoting deliveries by skilled attendants in Busia, Kenya. Global journal of health science. 2012;4(2):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koo K, Makin JD, Forsyth BW. Barriers to male-partner participation in programs to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in South Africa. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25(1): 14–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming PJ, DiClemente RJ, Barrington C. Masculinity and HIV: Dimensions of masculine norms that contribute to men’s HIV-related sexual behaviors. AIDS and behavior. 2016;20(4):788–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siu GE, Wight D, Seeley J. ‘Dented’ and ‘Resuscitated’ masculinities: The impact of HIV diagnosis and/or enrolment on antiretroviral treatment on masculine identities in rural eastern Uganda. Sahara J. 2014; 11(1):211–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falnes E, Moland K, Tylleskär T, de Paoli M, Msuya SE, Engebretsen IM. " It is her responsibility": partner involvement in prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV programmes, northern Tanzania. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2011. ;14(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ditekemena J, Matendo R, Koole O, Colebunders R, Kashamuka M, Tshefu A, et al. Male partner voluntary counselling and testing associated with the antenatal services in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: a randomized controlled trial. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2011;22(3): 165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osoti AO, John-Stewart G, Kiarie J, Richardson B, Kinuthia J, Krakowiak D, et al. Home Visits during Pregnancy Enhance Male Partner HIV Counseling and Testing in Kenya: A Randomized Clinical Trial. AIDS (London, England). 2014;28(1):95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz DA, Kiarie JN, John-Stewart GC, Richardson BA, John FN, Farquhar C. Male perspectives on incorporating men into antenatal HIV counseling and testing. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reece M, Hollub A, Nangami M, Lane K. Assessing male spousal engagement with prevention of mother-to-child transmission (pMTCT) programs in western Kenya. AIDS Care. 2010;22(6):743–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orne-Gliemann J, Tchendjou PT, Miric M, Gadgil M, Butsashvili M, Eboko F, et al. Couple-oriented prenatal HIV counseling for HIV primary prevention: an acceptability study. BMC public health. 2010;10(1):197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez M, Cohen S. Social support Encyclopedia of mental health. New York: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bekele T, Rourke SB, Tucker R, Greene S, Sobota M, Koornstra J, et al. Direct and indirect effects of perceived social support on health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2013;25(3):337–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galvan FH, Davis EM, Banks D, Bing EG. HIV stigma and social support among African Americans. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2008;22(5):423–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Earnshaw VA, Lang SM, Lippitt M, Jin H, Chaudoir SR. HIV Stigma and Physical Health Symptoms: Do Social Support, Adaptive Coping, and/or Identity Centrality Act as Resilience Resources? AIDS and behavior. 2015;19(1):41–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takada S, Weiser SD, Kumbakumba E, Muzoora C, Martin JN, Hunt PW, et al. The dynamic relationship between social support and HIV-related stigma in rural Uganda. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;48(1):26–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brittain K, Giddy J, Myer L, Cooper D, Harries J, Stinson K. Pregnant women's experiences of male partner involvement in the context of prevention of mother-to-child transmission in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2015;27(8):1020–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nyondo-Mipando AL, Chimwaza AF, Muula AS. “He does not have to wait under a tree”: perceptions of men, women and health care workers on male partner involvement in prevention of mother to child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus services in Malawi. BMC health services research. 2018; 18(1): 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asefa F, Geleto A, Dessie Y. Male partners involvement in maternal ANC care: the view of women attending ANC in Hararipublic health institutions, eastern Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2014;2(3): 182–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theuring S, Nchimbi P, Jordan-Harder B, Harms G. Partner involvement in perinatal care and PMTCT services in Mbeya Region, Tanzania: the providers' perspective. AIDS Care. 2010;22(12): 1562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medley AM, Mugerwa GW, Kennedy C, Sweat M. Ugandan men's attitudes toward their partner's participation in antenatal HIV testing. Health care for women international. 2012;33(4): 359–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mburu G, Ram M, Siu G, Bitira D, Skovdal M, Holland P. Intersectionality of HIV stigma and masculinity in eastern Uganda: implications for involving men in HIV programmes. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siu GE, Wight D, Seeley J. ‘Dented’and ‘Resuscitated’masculinities: The impact of HIV diagnosis and/or enrolment on antiretroviral treatment on masculine identities in rural eastern Uganda. SAHARA-J:. 2014; 11 (1):211–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mankayi N, Vernon Naidoo A. Masculinity and sexual practices in the military: a South African study. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2011; 10(1):43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siu GE, Wight D, Seeley JA. Masculinity, social context and HIV testing: an ethnographic study of men in Busia district, rural eastern Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siu GE, Seeley J, Wight D. Dividuality, masculine respectability and reputation: How masculinity affects men's uptake of HIV treatment in rural eastern Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 2013:89:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sileo KM, Fielding-Miller R, Dworkin SL, Fleming PJ. What Role Do Masculine Norms Play in Men’s HIV Testing in Sub-Saharan Africa?: A Scoping Review. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;22(8):2468–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindegger G, Quayle M. Masculinity and HIV/AIDS HIV/AIDS in South Africa 25 Years On: Springer; 2009. p. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jewkes R, Morrell R. Sexuality and the limits of agency among South African teenage women: Theorising femininities and their connections to HIV risk practises. Social Science & Medicine. (0). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson LF. Access to antiretroviral treatment in South Africa, 2004-2011. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine. 2012; 13(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ratele K Analysing Males in Africa: Certain Useful Elements in Considering Ruling Masculinities 2008. 515–36 p. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seeley J, Mbonye M, Ogunde N, Kalanzi I, Wolff B, Coutinho A. HIV and identity: the experience of AIDS support group members who unexpectedly tested HIV negative in Uganda. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2012;34(3):330–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramirez-Ferrero E Male Involvement in the Prevention of Mother-To-Child transmission of HIV. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]