Abstract

BACKGROUND

Ganglioneuroma (GN) is a rare neurogenic tumor that accounts for about 0.1%-0.5% of all tumors of the nervous system. It originates from neural crest cells. GN has no specific clinical symptoms or laboratory findings, which leaves it easily overlooked and misdiagnosed as other tumors. Retroperitoneal GN with very large volume and vascular penetration is extremely rare.

CASE SUMMARY

We present the imaging and pathological findings of a giant retroperitoneal GN in a child. A 4-year-old boy had suffered from postprandial vomiting for more than 6 mo with no precipitating factors. Abdominal computerized tomographic examination showed a giant cystic mass in the retroperitoneal area. After injection of contrast agent, the mass showed heterogeneous enhancement. Surgery with local excision of the mass was performed to address the embedded abdominal blood vessels, and the histopathological and immunohistochemical diagnosis of the mass was GN. Postprandial vomiting was relieved, and no complications occurred after the operation.

CONCLUSION

In the diagnosis of giant retroperitoneal hypodense masses in children, GN should be considered if the mass presents delayed enhancement, punctate calcification, and vascular embedding but no invasion. Pathology is the golden standard for the diagnosis of GN, and surgical excision is the optimal treatment for GN.

Keywords: Retroperitoneal, Ganglioneuroma, Postprandial vomiting, Case report

Core tip: Ganglioneuroma (GN) is a rare benign neurogenic tumor originating from the sympathetic nerve chain. Although it often occurs in the retroperitoneum, we report a case of giant GN causing postprandial vomiting and enclosing all major abdominal vessels, which is clinically rare. Surgical resection is the optimal choice for the treatment of GN at present. Pathology is the gold standard for the diagnosis of GN, and the presence of mucous matrix and ganglion cells are pathological features of GN.

INTRODUCTION

Ganglioneuroma (GN) is a benign neurogenic tumor that accounts for more than 0.1%-0.5% of all tumors of the nervous system[1]. It commonly occurs in the mediastinum (41.5%) and retroperitoneum (37.5%)[1-3]. Patients are usually asymptomatic, and GN is often found via physical examination. However, the tumor can press against the adjacent organs and cause complications if it reaches a great enough size. Here, we introduce a case of a 4-year-old boy with giant retroperitoneal GN associated with postprandial vomiting enclosing the main abdominal vessels. To our knowledge, existing reports mention only small arteries passing through GN, and there is no previous work reporting GN enclosing so many large arteries. The aim of our report is to present a rare case and discuss the related clinical, imaging, and pathological features.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 4-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital with a history of postprandial vomiting for more than 6 mo without precipitating factors and abdominal pain, chill, fever, or anal cessation of exsufflation or defecation.

History of present illness

He had poor appetite but no weight loss during his illness.

History of past illness

The child was of full-term natural delivery with normal feeding and timely vaccination.

Personal and family history

He had no previous or family history of similar illnesses.

Physical examination upon admission

Physical examination showed abdominal bulge and intestinal type in the upper abdomen. The epigastrium showed a palpable mass with poor mobility; the lump was hard but was associated with no tenderness.

Laboratory examinations

The laboratory examinations (including blood and urine routine tests, coagulation function tests, liver and kidney function tests, and tumor markers) were normal.

Imaging examinations

The pre-contrast computerized tomographic (CT) scan presented a retroperitoneal giant hypodense mass with a size of 10.7 cm × 17.3 cm × 15.5 cm and a CT value of 33.8 HU. Spotted calcification with irregular distribution was noted in the mass. The tumor showed inhomogeneous flocculent enhancement in the venous phase and further enhancement in the delayed phase after intravenous injection of contrast agent (Figure 1). We observed that the stomach had been pushed forward and displaced, which was also considered the main cause of postprandial vomiting for the patient. The tumor surrounded the celiac trunk, hepatic artery, splenic artery, superior mesenteric artery, bilateral renal artery, and portal vein. Nevertheless, the enclosed vascular lumen did not become narrowed or distorted (Figure 2 and 3). Of course, this created a difficult problem for the patient’s surgical treatment, such that the surgeon was only able to remove the relatively non-vascular part of the tumor.

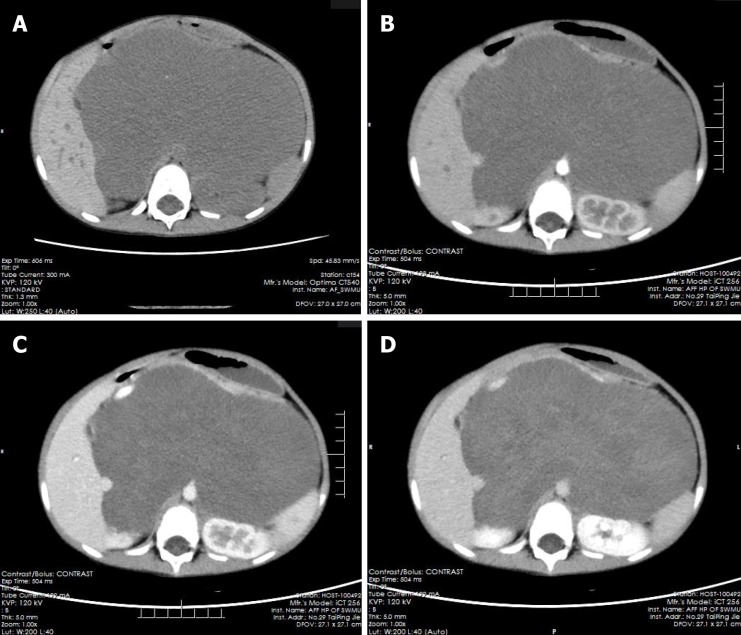

Figure 1.

Multiphase enhanced computerized tomographic images of the patient. A: Giant retroperitoneal hypodense mass in pre-contrast and punctate calcification could be noted; B: The hypodense mass without enhancement in arterial and venous phase, and the stomach and kidneys were compressed and displaced; C: The mass presented mild enhancement in venous phase; D: The mass showed patchy and flocculent enhancement in delay phase, and the extent of enhancement was greater than that of the venous phase.

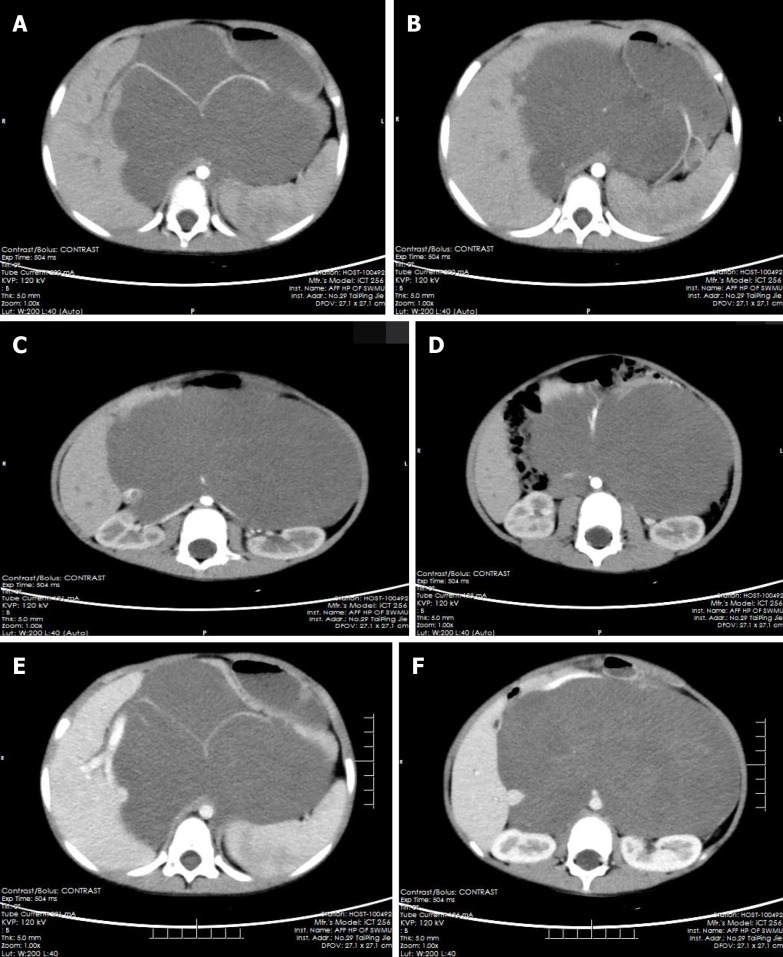

Figure 2.

The computerized tomographic images of tumors surrounding blood vessels. A-D: Tumor-enclosed arteries: hepatic artery (A), splenic artery (A, B), bilateral renal artery (C), superior mesenteric artery (D); E, F: Tumor-enclosed veins: Portal vein (E) and inferior vena cava (F).

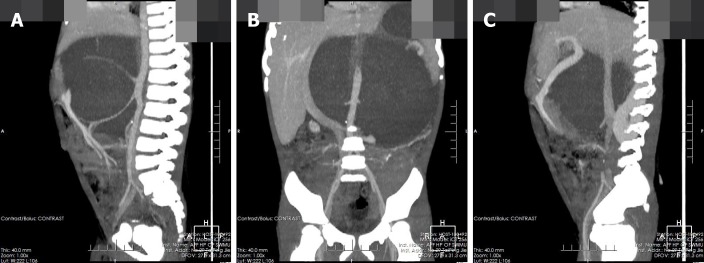

Figure 3.

Coronal and sagittal of the computerized tomographic images. A, B: Tumor-enclosed arteries; C: Tumor-enclosed veins.

Histopathology revealed the spindle cell tumor with nerve fibers and ganglion cells. Immunohistochemical investigation showed the tumor cells expressed NSE (diffuse +), Syn (+), S100 (diffuse +), and NF (diffuse +) and were negative for GFAP, CR, P53, and SMA. The Ki-67 proliferation index was 5%.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Retroperitoneal GN.

TREATMENT

The patient underwent partial resection of two retroperitoneal tumors about 6.0 cm × 3.0 cm × 2.0 cm and 6.0 cm × 5.0 cm × 4.0 cm in size.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Postprandial vomiting was relieved, and no complications occurred. The patient was discharged 10 d after surgery. The patient’s parents declined follow-up after discharge and did not disclose their reasons.

DISCUSSION

Retroperitoneal GNs account for 37.5% of all GNs and about 0.72%-1.6% of primary retroperitoneal tumors[1-3]. GNs can also occur in the vertebra, neck, and cerebellopontine angle region (trigeminal); all three of which are relatively rare[4-8]. GNs are found incidentally in most cases and manifest as asymptomatic masses[2,9,10]. The tumor could cause some complications if it becomes large enough to press against the adjacent organs. In our case, the stomach dilated after meals, peristalsis became limited after means due to the compression from the GN, and food could not easily enter the duodenum, causing postprandial vomiting. Occasionally, GNs occurring in the adrenal gland can secrete vasoactive intestinal peptides, dopamine, and cortisol, which lead to diarrhea, hypertensive crisis, and male-like metabolic disorders in women[11-13].

GNs are mainly composed of ganglion cells, mucus matrix, nerve fibers, and mature Schwann cells, and the first two of them are characteristic components in histopathology[14,15]. The pathological features of GN are closely related to its CT findings. The presence of mucus matrix in tumors determines the hypodensity on plain CT scans. The mucus matrix has been found to delay the absorption of contrast agents, which leads to the delayed enhancement of GNs[16,17]. This case was misdiagnosed as retroperitoneal cystic lymphangioma initially. Similar to this case, cystic lymphangioma tends to occur in children and presents as a large, well-defined low-density mass in the retroperitoneum[18], which can also wrap around blood vessels without distorting them, while a retroperitoneal GN of such a large size as this case is rare and it is predominant in adults. However, in this case, flocculent and strip delayed enhancement was observed, which was consistent with the enhancement of GN, while cystic lymphangioma was generally not enhanced, which was the most important distinguishing point between them. Calcifications have been noted in 20%-60% of GNs, and most of them are punctate, which is also one of the differences between GN and neuroblastoma[19,20]. Punctate calcification with scattered distribution was also noted on plain CT images in this case. Ko et al[14] and Duffy et al[21] suggested that the presence of fat components in GN may be one of the characteristics of GN, but their sample size was too small to verify this, and we did not notice any fat replacement in our case. Some scholars have proposed that the blood vessels are often surrounded or compressed by GNs instead of being invaded, although most of them are small vessels[16,22], and this finding further suggested that GNs are benign. In this case, GN enclosed all major abdominal vessels, including the celiac trunk, hepatic artery, splenic artery, bilateral renal artery, superior mesenteric artery, inferior vena cava, and portal vein. None of the enclosed vessels had a narrowed lumen or filling defect, which provided more reliable support for these scholars’ views. However, there are some reports suggesting that GNs could behave aggressively, and recurrence or malignant transformation[2,23,24] and complete surgical excision are the most optimal choice for the treatment[8,25]. Therefore, patients with GN still need long-term radiological follow-up. In addition, some scholars have put forward a different view, arguing that incomplete resection of GN does not increase the risk of progression if residual tumors are less than 2 cm in diameter[10]. We believe that it is important to determine whether the tumor is invasive before surgery and assess pathology to select the most suitable surgical method, an area in which we believe the current research into GN is lacking.

In conclusion, GNs appear as hypodense masses on plain scans and present delayed and mild enhancement on contrast enhancement. Pathology is the gold standard for the diagnosis of GN, and mucous matrix and ganglion cells are their important features. Surgical excision is the best treatment for GN, and postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy are unnecessary. However, in cases where it is difficult to completely dissect the tumors and blood vessels, partial resection could still relieve the pressure symptoms created by the tumors. Long-term radiological follow-up after the operation is necessary, even though the biological behavior of GN is benign, because there is still a tendency to be malignant, especially in patients with GN who have undergone only local resection.

CONCLUSION

Retroperitoneal GN, which is huge and encloses a large number of blood vessels without invading, is rare in clinical settings. Although some previous studies maintain that complete resection of the tumor is not necessary, finding suitable ways of assessing the invasiveness of GN after pathology and radiology still needs further discussion and study.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 4, 2019

First decision: July 30, 2019

Article in press: August 20, 2019

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pandey A S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL

Contributor Information

Xue Zheng, Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou 646000, Sichuan Province, China.

Li Luo, Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou 646000, Sichuan Province, China.

Fu-Gang Han, Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou 646000, Sichuan Province, China. 8311hfg@163.com.

References

- 1.Shimada H, Ambros IM, Dehner LP, Hata J, Joshi VV, Roald B. Terminology and morphologic criteria of neuroblastic tumors: recommendations by the International Neuroblastoma Pathology Committee. Cancer. 1999;86:349–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lonergan GJ, Schwab CM, Suarez ES, Carlson CL. Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002;22:911–934. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.4.g02jl15911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geoerger B, Hero B, Harms D, Grebe J, Scheidhauer K, Berthold F. Metabolic activity and clinical features of primary ganglioneuromas. Cancer. 2001;91:1905–1913. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010515)91:10<1905::aid-cncr1213>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulusoy OL, Aribal S, Mutlu A, Enercan M, Ozturk E. Ganglioneuroma of the lumbar spine presenting with scoliosis in a 7-year-old child. Spine J. 2016;16:e727. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santaella FJ, Hamamoto Filho PT, Poliseli GB, de Oliveira VA, Ducati LG, Moraes MPT, Zanini MA. Giant Thoracolumbar Dumbbell Ganglioneuroma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2018;53:288–289. doi: 10.1159/000488499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urata S, Yoshida M, Ebihara Y, Asakage T. Surgical management of a giant cervical ganglioneuroma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2013;40:577–580. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng X, Fang J, Luo Q, Tong H, Zhang W. Advanced MRI manifestations of trigeminal ganglioneuroma: a case report and literature review. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:694. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2729-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrena López C, De la Calle García B, Sarabia Herrero R. Intradural Ganglioneuroma Mimicking Lumbar Disc Herniation: Case Report. World Neurosurg. 2018;117:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.05.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yam B, Walczyk K, Mohanty SK, Coren CV, Katz DS. Radiology-pathology conference: incidental posterior mediastinal ganglioneuroma. Clin Imaging. 2009;33:390–394. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decarolis B, Simon T, Krug B, Leuschner I, Vokuhl C, Kaatsch P, von Schweinitz D, Klingebiel T, Mueller I, Schweigerer L, Berthold F, Hero B. Treatment and outcome of Ganglioneuroma and Ganglioneuroblastoma intermixed. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:542. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2513-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koch CA, Brouwers FM, Rosenblatt K, Burman KD, Davis MM, Vortmeyer AO, Pacak K. Adrenal ganglioneuroma in a patient presenting with severe hypertension and diarrhea. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:99–107. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diab DL, Faiman C, Siperstein AE, Zhou M, Zimmerman RS. Virilizing adrenal ganglioneuroma in a woman with subclinical Cushing syndrome. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:584–587. doi: 10.4158/EP.14.5.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erem C, Kocak M, Cinel A, Erso HO, Reis A. Dopamine-secreting adrenal ganglioneuroma presenting with paroxysmal hypertension attacks. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:122–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko SM, Keum DY, Kang YN. Posterior mediastinal dumbbell ganglioneuroma with fatty replacement. Br J Radiol. 2007;80:e238–e240. doi: 10.1259/bjr/97270791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herr K, Muglia VF, Koff WJ, Westphalen AC. Imaging of the adrenal gland lesions. Radiol Bras. 2014;47:228–239. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2013.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan YB, Zhang WD, Zeng QS, Chen GQ, He JX. CT and MRI findings of thoracic ganglioneuroma. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e365–e372. doi: 10.1259/bjr/53395088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otal P, Mezghani S, Hassissene S, Maleux G, Colombier D, Rousseau H, Joffre F. Imaging of retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:940–945. doi: 10.1007/s003300000698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alqahtani A, Nguyen LT, Flageole H, Shaw K, Laberge JM. 25 years' experience with lymphangiomas in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1164–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang F, Liu J, Zhang R, Bai Y, Li C, Li B, Liu H, Zhang T. CT and MRI of adrenal gland pathologies. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2018;8:853–875. doi: 10.21037/qims.2018.09.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichikawa T, Ohtomo K, Araki T, Fujimoto H, Nemoto K, Nanbu A, Onoue M, Aoki K. Ganglioneuroma: computed tomography and magnetic resonance features. Br J Radiol. 1996;69:114–121. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-69-818-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duffy S, Jhaveri M, Scudierre J, Cochran E, Huckman M. MR imaging of a posterior mediastinal ganglioneuroma: fat as a useful diagnostic sign. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:2658–2662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai TY, Mendis R, Das KK, Stephen M, Crawford M. Rare adrenal ganglioneuroma encasing the inferior vena cava. ANZ J Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1111/ans.14744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi Y, Iwato M, Hasegawa M, Tachibana O, von Deimling A, Yamashita J. Malignant transformation of a gangliocytoma/ganglioglioma into a glioblastoma multiforme: a molecular genetic analysis. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:138–142. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.1.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulkarni AV, Bilbao JM, Cusimano MD, Muller PJ. Malignant transformation of ganglioneuroma into spinal neuroblastoma in an adult. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:324–327. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.2.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraga JC, Aydogdu B, Aufieri R, Silva GV, Schopf L, Takamatu E, Brunetto A, Kiely E, Pierro A. Surgical treatment for pediatric mediastinal neurogenic tumors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]