Abstract

One of the largest change operations to take place in South Australia was the moving of the Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) to its new site in 2017. Change can influence workplace effectiveness and staff satisfaction and morale. Understanding the stages of change, staff experience and carefully managing the process is important. This paper aims to describe the successful move of the radiation therapy department at the RAH to its new site, focusing on the staff experience and management strategies to ensure the success of the move. A four‐stage model of change was used to guide understand, manage and reflect upon the transition of the RAH radiation therapy department to a new site. Key change events and management strategies are described and aligned with the four stages of change. The move to the new site was a great success with a transition period working across two sites enabling a slower ramp up of activity at the new site supporting staff and patients in adjusting to the new environment. The four‐stage model of change assisted in the smooth implementation of a transition plan for radiation oncology. At the RAH, innovation and development are encouraged, along with management having a comprehensive understanding of organisational change enabling the radiation oncology department to successfully navigate rapid change.

Introduction

One of the largest change operations to take place in South Australian history was the move of the Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) to its new site in 2017. Change can influence workplace effectiveness, staff satisfaction and morale. Understanding how staff experience stages of change and carefully managing the process is important.

This paper aims to describe the successful move of the radiation therapy department at the RAH to its new site, focusing on the staff experience and management strategies to ensure the success of the move. A brief overview of the RAH history and the new RAH, as well as the public radiation oncology services across South Australia (SA) will be presented. An outline of change management theory and the model utilised to guide the move will be described.

The Former Royal Adelaide Hospital

The former RAH was founded in 1840 and accommodated 30 patients.1 Prior to the hospital moving sites in 2017, it had grown to accommodate 800 beds and multiple departments including the radiation oncology department. The radiation oncology department was first opened in 1962,1 and in 2017 prior to moving sites there were four linear accelerators (linacs) (one was decommissioned), a planning computer tomography (CT) scanner, a superficial X‐ray unit (SXR), a brachytherapy unit, a planning room and a mould room.

The RAH and Lyell McEwin Hospital (LMH) radiation oncology services are mainly under the same governance structure and resources are shared between sites. The LMH site is located 25 km north of Adelaide and has two linacs, a planning CT, a planning room and mould room.

New Royal Adelaide Hospital

The new RAH is the state’s flagship public hospital. The radiation therapy department is spacious in design taking advantage of natural light with two garden areas for patients and staff to access. The department has five bunkers with four linear accelerators providing the latest technology to SA Health patients. Table 1 provides an overview of the SA public radiation oncology service with equipment, basic activity figures from 2016 to 2017 year, standard operating hours and a staff head count for each site.

Table 1.

SA public radiation oncology services in 2017.

| Old Royal Adelaide Hospital | Lyell McEwin Hospital | New Royal Adelaide Hospital | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment | 3 × linacs (+1 retired on 1 July 2017) | 2 × linacs | 4 × linacs |

| 1 × CT scanner | 1 × CT scanner | 1 × CT scanner | |

| Planning room with 12 desks | Planning room with 4 desks | Planning room with 18 desks | |

| 1 × SXR | Mould room | 1 × SXR | |

| 1 × Brachytherapy unit | 1 × Brachytherapy unit | ||

| Mould room | Mould room | ||

| Standard Operating Hours Pre‐Move | 8 am–6 pm (closed in September 2017) | 8 am–5 pm | 8 am–6 pm (opened in August 2017) |

| Number of Courses of Treatment 2016/17 | 1455 | 621 | – |

| RT Staff Head Count | ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐69‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ | ||

Change management

An overview of change models will be presented to assist with an understanding of how people cope with change. Change can cause a sense of loss, anxiety and it can take time for people to understand what the change means and to commit to it.2, 3 It is important when managing staff through change to have an understanding of the normal progression of change, and how people adjust to and embrace change can help managers avoid undermanaging change or overreacting to resistance.3, 4, 5, 6

People experience change in different ways and various models have been used to assist in understanding this phenomena.7, 8, 9 Lewin presented one of the earliest models of change, a three‐step model based around the social scientist idea of balancing forces working in opposite directions.10 Burne criticised this model given the constant presence of change, where there is no initial or final stable situation in reality.11 The model was outcome‐based, rather than people oriented and therefore, this model was not viewed as suitable for assisting in managing the move of a department.

The Kotter model with eight stages is a more recently developed process for managers to lead change.12 Lewin’s10 and Kotter’s12 models focused on manipulating the change by promoting or inhibiting forces, rather than gaining a better understanding of how people cope or react to change. A model proposed by Riches13 that was adapted from the well‐renowned transition grief cycle first published in 1969 by Kübler‐Ross8 was considered. This model has been utilised in organisational change management when taking into account the psychological impact that change can have on people.14, 15 The Kubler‐Ross model16 has five stages for responding to catastrophic news (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance). A more applicable model for organisational management has four stages (denial, resistance, exploration and commitment) and has been used in a variety of settings including the introduction of new techniques, professional practice of radiation therapists (RTs).3, 14, 17, 18, 19 The four‐stage model was utilised as it provided support to staff moving through a change process, as it accounts for how people cope with change and has management strategies that can be used to support in the process of change; therefore, this model was viewed as an appropriate model for managing staff in the move to the new RAH.

Stages of Change

A four‐stage model3, 14, 19 of change was used to guide understand, manage and reflect upon the transition of the RAH radiation oncology department to a new site. Table 2 provides a summary of the four‐stage model. The first stage is Denial, where the idea of change or the change itself is first introduced to individuals.3, 14, 19 This stage often involves individuals not believing in the change and convincing themselves that they will not have to go through the change. Two approaches that can assist individuals through this initial stage are communication and time.3, 9 Communication during this stage is important as individuals need clear, accurate information about the change, the rationale for the change and they need to know details such as, who the change will impact on and how it will impact on their work.3, 19, 20 It is also important to provide time frames during this stage as this will give employees an idea of how long they have to adjust to the change.3

Table 2.

| Stages of change | Management strategies |

|---|---|

| 1. Denial | |

| Initially change is met with disbelief and denial. |

Communication is important at this time providing information on who will be affected and how and timeframes. Give employees time to prepare for change. |

| 2. Resistance | |

| Anger and blame are often emotions that follow disbelief and denial. When a workplace is experience change some employees will actively resist the changes. | During this phase, it is important to acknowledge how employees have responded or reacted to change. Making time to listen and empathise with them is important. |

| 3. Exploration | |

| As people work through their anger, they move through a stage of reluctantly accepting the changes and they begin to explore their role in it. |

Provide employees with practical encouragement and support. Provide training. Focus on achieving some short‐term goals. |

| 4. Commitment | |

| This stage is when employees commit to the change. There is a shift in focus from the past to the future. | Recognise those employees who have acclimatised to change well. |

Resistance is the second stage of change and involves individuals experiencing resentment, blaming others and finding ways to try to stop the change.3, 14, 19 It is important for managers to be aware that this is a period where mistakes may occur and the quality of work may decrease due to individuals withdrawing or experiencing a lack of concentration.3 This lack of concentration or withdrawal can be based around employees focusing their full attention on the change and dealing with it on an emotional level.3 During this stage, time needs to be scheduled to engage employees in contributing their expert knowledge. It is also the time for managers to acknowledge, listen and empathise with individuals on how they respond to the change.3

Exploration is the third stage where individuals begin to accept the change and investigate what it means.3, 14, 19 During this stage, individuals often ask many questions, express concern about a lack of time and ask for training to support the change.3, 14, 19 At this stage, managers need to provide practical support and encouragement to individuals, and invite their contributions in the process. Suitable training for staff should be provided during this time and it is important that individuals are given the opportunity to plan and set goals. Managers need to focus on short‐term goals and the benefits of the change.3, 14, 19

The final stage is Commitment when individuals are ready to entrust in the change.3, 14, 19 At this stage, managers need to recognise and provide positive feedback to individuals who have successfully adapted to the change. For individuals who are still working their way through the change process, managers need to work with them and use strategies discussed during the denial, resistance and exploration phases.3

Moving the Royal Adelaide Hospital – Radiation Therapy Department

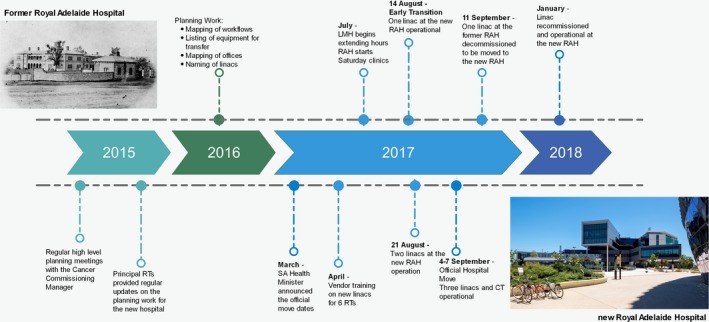

A timeline of key change events that took place in the 2 years leading up to the move to the new hospital have been presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of key change and transition events between 2015 and 2018.

Denial and resistance – uncertainty about the hospital move

In 2015, the move of the RAH to its new site was not on the radar for the majority of RT staff; however, it was discussed by the management regularly. Language such as ‘the hospital may never move’ was a sign of not wanting to face the change indicating the denial stage. From late 2015, radiation oncology held new RAH meetings fortnightly where the management team attended to coordinate the high‐level facilitation of the move with the Cancer Commissioning Manager. At regular clinical meetings with RTs, new RAH items and updates were provided by the Principal RTs.

Throughout 2016, a lot of planning took place with mapping of workflows, identifying equipment to be transferred, mapping of office allocation and naming of linacs. During 2016, there was a sense of apprehension from the RTs about the move and that it may never eventuate. The Principal RTs provided staff with regular updates to inform staff about what they specifically needed to do and timelines, rather than focusing on the enormity of coordinating the move.

The managers planned for all 69 RTs to visit the new department for half a day for the purpose of (1) being oriented and familiar with the new department and the surrounding environment and (2) implement the train the trainer model to enable all RTs to have the opportunity to learn about the new equipment and have hands on experience. This proposal was met with resistance and many reasons were provided as to why RTs did not need to visit the new site. RTs not wanting to engage in visiting the new department indicated both denial and resistance. Staff were either vocal about how the plans would not work or they withdrew and were silent. While there was uncertainty about when (and if) the RAH would move, staff remained in the first two stages of the change model – denial and resistance.

Exploration – training and familiarisation

In April 2017, a group of six RTs had 4 days of vendor training on the new linacs at the new hospital. At the beginning of the training week, the RTs onsite was excited about being in the new department. When the group of six returned to the former RAH department the following week, their positivity about the new department spread quickly across the RTs and the team as a whole were more positive about moving from that point forward. The onsite linac training was a turning point in the change process for the RT group.

RT management provided the group with as much training and exposure to the new department as they could. Detailed plans were distributed to the team and management were available to answer questions. The RTs were all asked to provide feedback on the new department, which helped them engage in the process of the move.

On 22 March 2017, the South Australian Health Minister announced the official RAH move would take place on the week commencing 4 September 2017. Prior to this announcement, the radiation therapy team had the Minister’s support for an early transition from 14 August to enable continuity of service to cancer patients and to enable a gradual ramp up of activity at the new department to reduce risk. An all staff radiation oncology forum was held following the Minister’s announcement and an email communication with a detailed 12‐week plan for the radiation therapy move was distributed.

Commitment – early transition and official hospital move

LMH increased their hours of operation from July 2017. From July, the RAH had three operational linacs and the department commenced Saturday clinics to allow current patients to finish their treatment at the former RAH.

Radiation therapy at the new hospital commenced with external beam treatment to four patients on the 14 August 2017 – this was part of the early transition. From 14 August, treatment commenced on one linac at the new RAH as one linac at the former RAH was closed. This meant there were three operational linacs across the two RAH sites, plus two at LMH. Patient numbers at the new RAH were capped at 48 during the transition. At the former RAH, there was a ‘skeleton’ team of planners to cover planning, CT, SXR and brachytherapy until these services moved to the new RAH. There was linac vendor support training for the first 3 days and a vendor engineer onsite to support for 2 days. The operational hours were reduced to 8:00 to 16:30 at the former RAH and new RAH from 14 August for the duration of the transition so only one shift was required.

Staff were excited and anxious about treating the first patients on the new linacs on the first day. A lot of planning, facilitation and effort from the RT team had gone into making sure the new department was ready for the early transition. A certificate was given to the first patient treated and a photograph taken with the Director of Radiation Oncology and the new RAH Executive Director.

From 21 August, a second linac at the new RAH was operational and there was vendor support training for 3 days. At the former RAH, there were two linacs each operating half a day.

With reduced activity at the former RAH and a gradual ramp up of activity at the new RAH, facilitated by increased activity at LMH, staff had more time to adjust to the new RAH equipment and department. For those RTs who were rostered to work at the new RAH for the early transition, there were definite signs they were engaged with their new environment and committed to making it work.

For the RTs rostered at the former RAH during the early transition, some took longer and were more reluctant to adjust to the new department. When the last group of RTs moved into the new department, they were paired with RTs who were committed to the new department and this helped the newer staff to adjust. By the end of the official move week, all staff were familiar with the new department and were making steps towards commitment.

The official hospital move

The hospital move took place over 4–7 September 2017. The new radiation oncology department continued treating with two linacs until 4 September when a third linac started treating patients. The final radiation oncology patient to receive treatment at the former RAH was presented with a certificate. One linac was transferred from the former RAH site to the new RAH and it was decommissioned the week of 11 September, then moved, recommissioned and started treating patients on 17 January 2018. The managers praised the team for their endurance throughout the change period.

Post official move

One month after the transition, staff were more settled in the new department and there was relief to be back working across two sites rather than three.

Summary

Change is dependent on the extent to which employees are willing to change,21 therefore, their coping mechanisms need to be central in managing a change process.22 Employees move through the change stages at different rates and this can often make change management complicated.9 Well‐managed change involves people feeling supported through the process of change.11

Moving the radiation oncology department was a large change operation made possible with a transition plan working across three sites with increased activity at LMH. This provided continuity of radiation therapy services to cancer patients in South Australia and enabled staff the capacity to move through the change stages: denial, resistance, exploration and commitment.

Ethics Approval

The Royal Adelaide Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee Human Research Ethics Committee approved the publication of this paper. Ethics notification was acknowledged on 21 December 2018. As this evaluation was considered a reflection on the move to the new RAH, no further ethics approval was required.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Deb Page (new RAH Cancer Commissioning Manager) for her support throughout the move, along with the radiation oncology team at the Royal Adelaide Hospital and Lyell McEwin Hospital, as well as the Cancer Executives at the RAH and Medical Executive team at LMH. We would also like to thank the media team at the Royal Adelaide Hospital for their support and promotion of the radiation oncology service.

J Med Radiat Sci xx (2019) 212–217

References

- 1. Long L, Coupland M. The Royal Adelaide Hospital: Service, Care, Teaching and Innovation. Bounce Books, Adelaide, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vakola M, Tsaousis I, Nikolaou I. The role of emotional intelligence and personality variables on attitudes toward organisational change. J Manag Psychol 2004; 19: 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scott CD, Jaffe DT. Managing Change at Work: Leading People Through Organizational Transitions. Cengage Learning, Melbourne, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huberman AM. Understanding Change in Education: An Introduction, Experiments and Innovations in Education No. 4. School of Psychology and Education, University of Geneva, Geneva: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hiatt JM. Employee's Survival Guide to Change: The Complete Guide to Surviving and Thriving During Organizational Change. Prosci Research, Colorado, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith DK. Taking Charge of Change: 10 Principles for Managing People and Performance. Perseus Books, New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cameron E, Green M. Making Sense of Change Management: A Complete Guide to the Models, Tools & Techniques of Organizational Change. Kogan Page Publishers, London, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kübler‐Ross E. On Death and Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy and their Own Families, 40th edn. Taylor & Francis, Oxon, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kotter J, Cohen DS. The Heart of Change: Real‐Life Stories of How People Change Their Organizations. Harvard Business Press, New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewin K. Field Theory in Social Science. Harper and Row, New York, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burne B. Kurt Lewin and the planned approach to change: A re‐appraisal. J Manag Stud 2004; 41: 977–1002. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kotter JP. Leading Change. Harvard Business Press, New York, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riches A. The four emotional stages of change, The CEO Refresher, viewed 2 November 2018, 2009. Available from: http://www.refresher.com/Archives/!stagesofchange.html(accessed November 2018).

- 14. Rashford NS, Coghlan D. Phases and Levels of Organisational Change. J Manage Psych 1989; 4: 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elrod D, Tippett D. The ‘death valley’ of change. J Organ Chang Manag 2002; 15: 273–91. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kübler‐Ross E. On Death and Dying. Macmillan, New York, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sale C. Radiation therapy practice in Australia: a development process. PhD thesis, Adelaide: University of South Australia, 2010.

- 18. Sale C, Batson A. Implementing results of a change process at the Andrew Love Cancer Centre – The axillary technique. Radiographer 2011; 58: 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reynolds L. Understanding employees’ resistance to change. HR Focus 1994; 71: 17. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Armenakis AA, Harris SG. Crafting a change message to create transformational readiness. J Organ Chang Manag 2002; 15: 169–83. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Issah M, Zimmerman J. A change model for 21st century leaders: The essentials. Int J Pedagog Innov 2016; 4: 23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vakola M, Nikolaou I. Attitudes towards organizational change: What is the role of employees’ stress and commitment? Employee Relat 2005; 27: 160–74. [Google Scholar]