Abstract

Retinaldehyde adducts (bisretinoids) accumulate in retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells as lipofuscin. Bisretinoids are implicated in some inherited and age-related forms of macular degeneration that lead to the death of RPE cells and diminished vision. By comparing albino and black-eyed mice and by rearing mice in darkness and in cyclic light, evidence indicates that bisretinoid fluoro-phores undergo photodegradation in the eye (Ueda et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113:6904–6909, 2016). Given that the photodegradation products modify and impair cellular and extracellular molecules, these processes likely impart cumulative damage to retina.

Keywords: Retinal degeneration, Age-related macular degeneration, ABCA4-associated disease, Bisretinoid, Visual cycle, Lipofuscin, Retinaldehyde, Vitamin E

49.1. Introduction

Adducts of vitamin A aldehyde having bisretinoid structures form in photoreceptor cells by non-enzymatic reactions between retinaldehyde and amine moieties (Sparrow et al. 2010). These fluorophores are deposited in RPE cells as components of phagocytosed outer segments and constitute the lipofuscin of RPE. Various bisretinoids of RPE lipofuscin have been isolated and structurally characterized (Sparrow et al. 2012).

Bisretinoids form in particular abundance in recessive Stargardt disease (STGD1) caused by mutations in the gene encoding the ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCA4). This accumulation culminates in the death of RPE. Marked bisretinoid accumulation is replicated in Abca4 null mutant mice (Weng et al. 1999; Kim et al. 2004), and the relationship between RPE lipofuscin accumulation and retinal disease is evidenced in the Abca4 mouse model by Bruch’s membrane changes and by a progressive loss of photoreceptor cells (Radu et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2010a; Radu et al. 2011; Sparrow et al. 2013; Zhou et al. 2015). Abca4−/− mice burdened by elevated levels of bisretinoid lipofuscin are also more susceptible to light damage than are wild-type mice (Wu et al. 2014). Here we review recent work establishing that photodegradation of bisretinoid and its adverse consequences are ongoing in the eye.

49.2. Bisretinoid Photooxidation and Photodegradation in Vitro

Given the adverse consequences of bisretinoid accumulation, efforts have been made to elucidate mechanisms by which these fluorophores damage cells. For instance, bisretinoids photogenerate reactive oxygen species such as singlet oxygen and superoxide anion (Gaillard et al. 1995; Rozanowska et al. 1995; Ben-Shabat et al. 2002; Jang et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2007; Yamamoto et al. 2011). By quenching these reactive forms of oxygen, bisretinoids are subsequently photooxidized, and with photocleavage at these oxidation sites, aldehyde- and dicarbonyl-carrying fragments are released (Wu et al. 2010b). Proteins modified by these dicarbonyls are constituents of drusen (Farboud et al. 1999; Handa et al. 1999); they cross-link protein and promote resistance to the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (Zhou et al. 2015).

49.3. Bisretinoid Levels in Albino and Black Mice Housed in Cyclic Light or Darkness

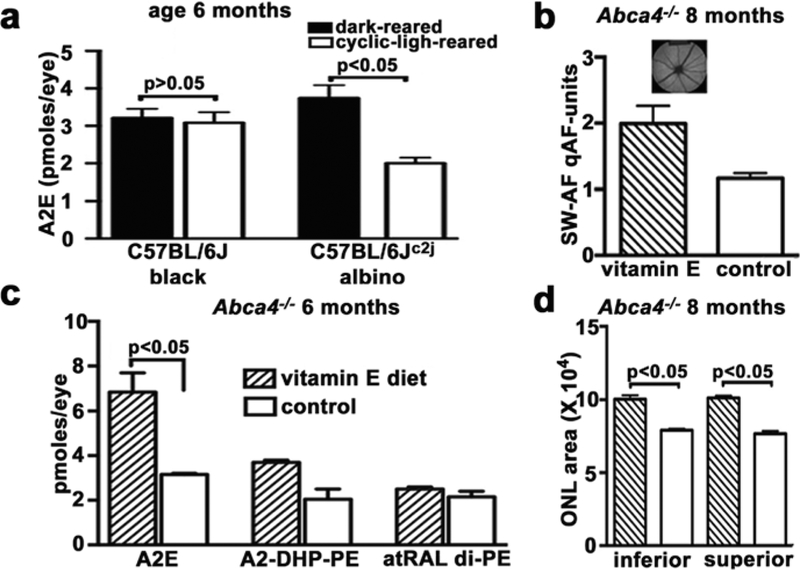

The photodegradation of bisretinoid was also demonstrated in mice by comparing levels of bisretinoid in mice raised in cyclic light (12 h on/12 h off) as opposed to darkness and by comparing albino (C57BL/6Jc2j) and black (C57BL/6 J) mice. In the absence of melanin, light entering the eye is substantially increased (LaVail and Battelle 1975; van den Berg et al. 1991). The bisretinoid A2E was detected in eyes from both cyclic light- and dark-reared mice (Fig. 49.1) (Boyer et al. 2012). Whereas it might be expected that the added photon catch in the albino eye would drive the formation of these visual cycle adducts (bisretinoids), instead A2E levels were lower in albino C57BL/6Jc2j mice maintained under cyclic light than in albino C57BL/6Jc2j mice reared in darkness (p < 0.05) (Fig. 49.1).

Fig. 49.1.

The RPE bisretinoid A2E accumulates in both light- and dark-reared mice, levels are reduced in light-reared versus dark-reared albino mice, and levels are modulated by antioxidant status. Analysis by reverse-phase HPLC. (a): Quantitation of the bisretinoid A2E in 6-month-old black C57BL/6J and albino C57BL/6J–c2j mice that were dark reared or cyclic light reared from birth. Means ± SEM of five or seven independent samples six to eight eyes/sample p-values determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test and two-tailed t-test. (b, c): Reduction in bisretinoid photooxidation by vitamin E supplementation is detected as reduced bisretinoid loss and measured as increased quantitative fundus autofluorescence (qAF) (b) and increased HPLC-quantified A2E, A2-DHP-PE, and atRAL di-PE (c). Means ± SEM of eight mice, p < 0.05, two-tailed t-test. (a); Two samples (six eyes per sample), ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test (b). (d): Reduced bisretinoid photooxidation/photodegradation also protects against outer nuclear layer (ONL) thinning. ONL area (microns2) calculated as the sum of the ONL thicknesses in the superior and inferior retina (0.2–2.0 mm from optic nerve head) multiplied by the measurement interval of 200 microns; means ± SEM, two-tailed t-test

Given in vitro evidence of photodegradation (Wu et al. 2010b) and the presence of oxidized bisretinoid in human and mouse retina (Jang et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2007), the most parsimonious explanation for the light-related differences is photooxidation-associated photodegradative loss of these light-sensitive fluorophores.

It is likely that bisretinoid formation under cyclic light is more pronounced than the levels observed here; for instance, photodegradative loss could mask even greater lipofuscin formation under cyclic light. The comparison of albino versus black-eyed mice presumably allowed photodegradative loss of A2E to be detected over a relatively short period of time. These photobleaching processes have been replicated in cell-based and non-cellular assays (Yamamoto et al. 2012), and examples of photooxidation and photodegradation of RPE bisretinoids (photobleaching) in retinae of human and nonhuman primates are reported (Hunter et al. 2012; Sparrow and Duncker 2014).

49.4. Vitamin E-Treated Mice: Evidence Supporting Photooxidative Processes in Modulating Bisretinoid Levels

It has been shown previously that the lipid-soluble antioxidant vitamin E can sup-press bisretinoid oxidation by quenching singlet oxygen (Sparrow et al. 2003b). In albino Abca4−/− mice given a vitamin E-supplemented diet (960 mg (IU)/kg vitamin E as dl-alpha-tocopheryl acetate) from 1 to 6 months of age, levels of the bisretinoids A2E (p < 0.05 one-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test), A2-DHP-PE, and all-trans-retinal dimer-PE were greater than in control mice. Quantitation of short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence (quantitative fundus autofluorescence, qAF) (Sparrow et al. 2013; Flynn et al. 2014) that originates from bisretinoid lipofuscin also revealed higher levels of fundus autofluorescence in the vitamin E-treated mice (p < 0.05, two-tailed t-test) (Fig. 49.1). Importantly, the thinning of outer nuclear layer that is indicative of reduced photoreceptor cell viability and that has been observed in albino Abca4−/− mice (Wu et al. 2010a; Sparrow et al. 2013; Wu et al. 2014) was less pronounced in the vitamin E-treated mice (p < 0.05, two-tailed t-test) (Fig. 49.1). The greater levels of bisretinoid and qAF in the vita-min E-treated versus control mice are consistent with a mechanism involving a reduction in photooxidation-associated consumption of bisretinoid in the presence of the antioxidant vitamin E.

49.5. Implications

The findings discussed here indicate that although light deprivation does not prevent the formation of bisretinoids (Boyer et al. 2012; Ueda et al. 2016), limiting light exposure can protect against damaging bisretinoid photodegradation. Thus not surprisingly, a black contact lens that blocked >90% of light in one eye of STGD1 patients was found to reduce the progression of decreased fundus autofluorescence (four of five patients) as compared with the patients’ unprotected eyes (Teussink et al. 2015). Sunglasses that attenuate light over a broad range of wavelengths or yellow lenses that reduce “blue” wavelengths might also be used to advantage.

Several studies, most notably the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS), have demonstrated that dietary antioxidants and intake of antioxidants by supplementation reduces incidence or progression of AMD (Snodderly 1995; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research 2001; SanGiovanni et al. 2007; Sobrin and Seddon 2014). Given that antioxidants can protect against AMD and that vitamins E and C have also been shown to reduce A2E photooxidation/photodegradation (Sparrow et al. 2003; Zhou et al. 2006), the beneficial effects of antioxidant intake could be mediated at least in part by intercepting bisretinoid photooxidation and degradation. Similarly, a contribution of lifetime light exposure to AMD risk (Cruickshanks et al. 2001; Tomany et al. 2004; Fletcher et al. 2008; Sui et al. 2013; Huang et al. 2014; Klein et al. 2014; Fritsche et al. 2016) could be mediated in part by the cellular damage imposed by bisretinoid photodegradation.

References

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research G (2001) A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol 119:1417–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shabat S, Itagaki Y, Jockusch S et al. (2002) Formation of a nona-oxirane from A2E, a lipofuscin fluorophore related to macular degeneration, and evidence of singlet oxygen involvement. Angew Chem Int Ed 41:814–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer NP, Higbee D, Currin MB et al. (2012) Lipofuscin and N-retinylidene-N-retinylethanolamine (A2E) accumulate in the retinal pigment epithelium in the absence of light exposure: their origin is 11-cis retinal. J Biol Chem 287:22276–22286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshanks KJ, Klein R, Klein BEK et al. (2001) Sunlight and the 5-year incidence of early age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol 119:246–250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farboud B, Aotaki-Keen A, Miyata T et al. (1999) Development of a polyclonal antibody with broad epitope specificity for advanced glycation endproducts and localization of these epitopes in Bruch’s membrane of the aging eye. Mol Vis 5:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher AE, Bentham GC, Agnew M et al. (2008) Sunlight exposure, antioxidants, and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 126:1396–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn E, Ueda K, Auran E et al. (2014) Fundus autofluorescence and photoreceptor cell rosettes in mouse models. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55:5643–5652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche LG, Igl W, Bailey JN et al. (2016) A large genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants. Nat Genet 48(2):134–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard ER, Atherton SJ, Eldred G et al. (1995) Photophysical studies on human retinal lipofuscin. Photochem Photobiol 61:448–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa JT, Verzijl N, Matsunaga H et al. (1999) Increase in advanced glycation end product pento-sidine in Bruch’s membrane with age. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40:775–779 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang EJ, Wu SH, Lai CH et al. (2014) Prevalence and risk factors for age-related macular degeneration in the elderly Chinese population in south-western Taiwan: the Puzih eye study. Eye (Lond) 28:705–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JJ, Morgan JI, Merigan WH et al. (2012) The susceptibility of the retina to photochemical damage from visible light. Prog Retin Eye Res 31:28–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang YP, Matsuda H, Itagaki Y et al. (2005) Characterization of peroxy-A2E and furan-A2E photo-oxidation products and detection in human and mouse retinal pigment epithelial cells lipofuscin. J Biol Chem 280:39732–39739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SR, Fishkin N, Kong J et al. (2004) The Rpe65 Leu450Met variant is associated with reduced levels of the RPE lipofuscin fluorophores A2E and iso-A2E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:11668–11672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SR, Jang YP, Jockusch S et al. (2007) The all-trans-retinal dimer series of lipofuscin pigments in retinal pigment epithelial cells in a recessive Stargardt disease model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:19273–19278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BE, Howard KP, Iyengar SK et al. (2014) Sunlight exposure, pigmentation, and incident age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55:5855–5861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVail MM, Battelle B-A (1975) Influence of eye pigmentation and light deprivation on inherited retinal dystrophy in the rat. Exp Eye Res 21:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radu RA, Yuan Q, Hu J et al. (2008) Accelerated accumulation of lipofuscin pigments in the RPE of a mouse model for ABCA4-mediated retinal dystrophies following vitamin A supplementation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49:3821–3829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radu RA, Hu J, Yuan Q et al. (2011) Complement system dysregulation and inflammation in the retinal pigment epithelium of a mouse model for Stargardt macular degeneration. J Biol Chem 286:18593–18601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanowska M, Jarvis-Evans J, Korytowski W et al. (1995) Blue light-induced reactivity of retinal age pigment. In vitro generation of oxygen-reactive species. J Biol Chem 270:18825–18830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanGiovanni JP, Chew EY, Clemons TE et al. (2007) The relationship of dietary lipid intake and age-related macular degeneration in a case-control study: AREDS report no. 20. Arch Ophthalmol 125:671–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodderly DM (1995) Evidence for protection against age-related macular degeneration by carotenoids and antioxidant vitamins. Am J Clin Nutr 62(suppl):1448S–1461S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobrin L, Seddon JM (2014) Nature and nurture- genes and environment- predict onset and progression of macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res 40:1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Duncker T (2014) Fundus autofluorescence and RPE lipofuscin in age-related macular degeneration. J Clin Med 3:1302–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Vollmer-Snarr HR, Zhou J et al. (2003) A2E-epoxides damage DNA in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Vitamin E and other antioxidants inhibit A2E-epoxide formation. J Biol Chem 278:18207–18213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Yoon K, Wu Y et al. (2010) Interpretations of fundus autofluorescence from studies of the bisretinoids of retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51:4351–4357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Gregory-Roberts E, Yamamoto K et al. (2012) The bisretinoids of retinal pigment epithelium. Prog Retin Eye Res 31:121–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Blonska A, Flynn E et al. (2013) Quantitative fundus autofluorescence in mice: correlation with HPLC quantitation of RPE lipofuscin and measurement of retina outer nuclear layer thickness. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54:2812–2820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui GY, Liu GC, Liu GY et al. (2013) Is sunlight exposure a risk factor for age-related macular degeneration? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Ophthalmol 97:389–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teussink MM, Lee MD, Smith RT et al. (2015) The effect of light deprivation in patients with Stargardt disease. Am J Ophthalmol 159(964–972):e962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomany SC, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein R et al. (2004) Sunlight and the 10-year incidence of age-related maculopathy. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol 122:750–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K, Zhao J, Kim HJ et al. (2016) Photodegradation of retinal bisretinoids in mouse models and implications for macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113:6904–6909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg TJTP, IJspeert JK, deWaard PWT(1991) Dependence of intraocular straylight on pigmentation and light transmission through the ocular wall. Vis Res 31:1361–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng J, Mata NL, Azarian SM et al. (1999) Insights into the function of Rim protein in photoreceptors and etiology of Stargardt’s disease from the phenotype in abcr knockout mice. Cell 98:13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Nagasaki T, Sparrow JR (2010a) Photoreceptor cell degeneration in Abcr−/− mice. Adv Exp Med Biol 664:533–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Yanase E, Feng X et al. (2010b) Structural characterization of bisretinoid A2E photocleav-age products and implications for age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107:7275–7280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Ueda K, Nagasaki T et al. (2014) Light damage in Abca4 and Rpe65rd12 mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55:1910–1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Yoon KD, Ueda K et al. (2011) A novel bisretinoid of retina is an adduct on glycerol-phosphoethanolamine. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52:9084–9090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Zhou J, Hunter JJ et al. (2012) Toward an understanding of bisretinoid autofluores-cence bleaching and recovery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53:3536–3544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Gao X, Cai B et al. (2006) Indirect antioxidant protection against photooxidative processes initiated in retinal pigment epithelial cells by a lipofuscin pigment. Rejuvenation Res 9:256–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Ueda K, Zhao J et al. (2015) Correlations between photodegradation of bisretinoid constituents of retina and dicarbonyl-adduct deposition. J Biol Chem 290:27215–27227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]