Case

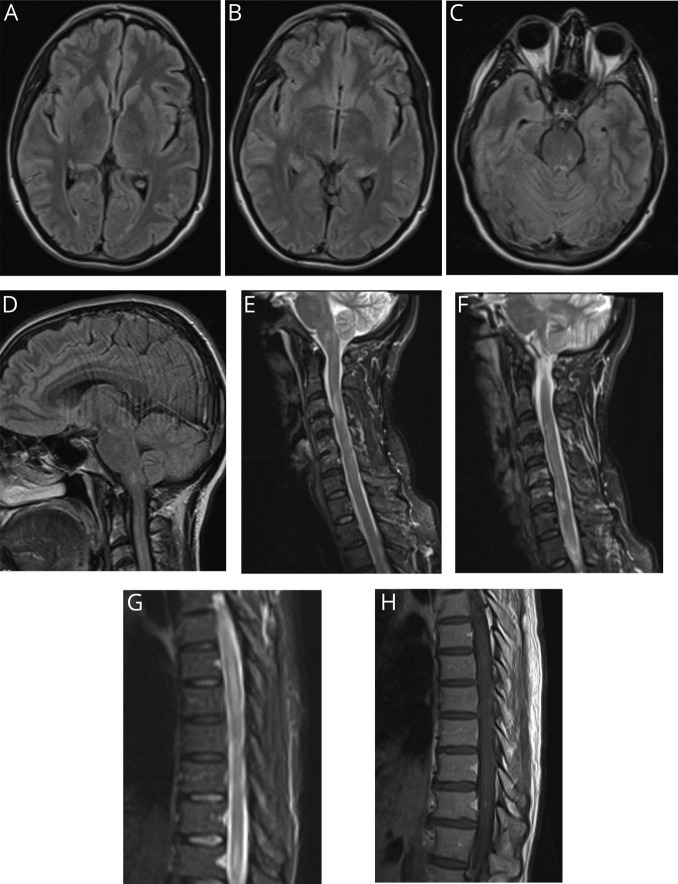

A healthy 44-year-old woman developed malaise and severe headache shortly after returning from vacation in Hawaii. As initial symptoms cleared after 24 hours, over the subsequent days, she developed paresthesias in her lower extremities (knees to feet), new-onset urinary retention, and midthoracic radicular pain. Brain MRI revealed nonenhancing lesions in the medulla and midbrain, in addition to punctate subcortical frontal lesions (figure). MRI of the cervical spine revealed 2 nonenhancing lesions at C3-C4 and C6-C7 (figure). She was diagnosed with MS and contemplated disease-modifying therapy (DMT).

Figure. MRI of the brain (A-D), MRI of the cervical spine (E, F), and MRI of the thoracic spine (G, H).

The patient presented to our center for a second opinion before starting DMT. Her residual dysesthesias and intermittent radicular pain were adequately controlled on duloxetine. She endorsed having eaten various types of seafood while vacationing. Neurologic examination was nonfocal with exception of hyperreflexia. Based on localization, a MRI thoracic spine was ordered, in addition to previous studies, and revealed a nonenhancing longitudinally extensive intramedullary lesion from T2-T9 along with an enhancing T11 intramedullary lesion (figure). Complete blood count with differential revealed eosinophilia (15% [normal 0%–6%]) without a leukocytosis. CSF evaluation revealed elevated protein (130 mg/dL [normal 15–45]), low glucose (21 mg/dL [normal 40–90]), eosinophilic pleocytosis (785 cells per mm2 [normal 0–5]; 51% eosinophils), 0 red blood cells, and 7 CSF-specific oligoclonal bands. Cytology and flow cytometry failed to reveal any malignant cells. Additional CSF studies including Gram stain, cultures, acid-fast stain, and viral and paraneoplastic panels were nonrevealing. Limited remaining CSF precluded additional testing. Additional serum testing including comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid stimulating hormone, B12, folate, B1, copper, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, Lyme serologies, antitreponemal antibodies, QuantiFERON, toxoplasma serology, angiotensin-converting enzyme, antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antibodies, double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, cryoglobulins, HIV, hepatitis panel, human T-lymphotropic virus 1/2 antibodies, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte gylcoprotein antibodies, anti-aquaporin 4 antibodies, and paraneoplastic and numerous viral panels were nonrevealing.

Repeat lumbar puncture 4 weeks later revealed normal CSF protein and glucose, as well as improving pleocytosis (8 cells per mm2). Given the initial eosinophilic meningitis (EM) and history of recent travel to Hawaii, an endemic parasitic agent was entertained. As such, using CSF, an Angiostrongylus cantonensis–specific PCR-based assay was ordered from the Centers for Disease Control and returned positive, thus confirming the diagnosis. On return visit, the patient's symptoms had resolved, repeat MRIs had improved, and no additional treatment was required.

Discussion

EM is rare, accounting for an estimated 2% of cases; however, when it does occur, the most common etiologies are helminthic infections, with a major pathogen being A. cantonensis.1 Less common, nonparasitic entities that cause EM include other infectious entities (fungal, viral, or bacterial), autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, Behcet disease, and sarcoidosis), neoplasms, implanted plastics devices, and certain drugs (ibuprofen and antibiotics).1 A. cantonensis, endemic to the Southeast part of Asia, the South Pacific, and the Caribbean, spends its life cycle alternating between rats and snails or slugs.2 Rarely, this cycle is interrupted as a human host ingests larvae from a contaminated food source, most commonly from snails; however, other vectors include crabs, fish, mollusks, prawns, or even vegetables that have been contaminated.1,4 The most common clinical symptom, occurring days to several weeks after ingestion, is meningitis with or without low-grade fever that tends to be self-limiting; however, various combinations of encephalitis, myelitis, and radiculitis have been described, and all occurred in our patient.1–3 High clinical suspicion in patients with appropriate clinical presentation after travel to endemic areas remains paramount to accurate diagnosis. MRI findings are nonspecific.5 In our patient, the MRI lesions lacked an ovoid appearance and were not in the classic juxtacortical, periventricular, or callosal locations typical of MS. Studies tend to reveal a peripheral blood eosinophilia in approximately 60%–80% of patients, abnormal CSF protein in approximately 70% of cases, and CSF eosinophilia (defined as >10 cells per mm2) in up to 96% of cases.1–3 Isolation of the parasite itself is rare, but a species-specific PCR-based assay is available.2,6 Treatment for A. cantonensis is controversial, as most cases resolve spontaneously.2 Serial high-volume lumbar punctures have been proposed for headache.2 The use of steroids and antihelminthic drugs in small randomized controlled trials both reduced headache days with the caveat that the use of antihelminthic medication may theoretically trigger a massive inflammatory cascade and potentially worsen symptoms.1–3 More data are needed before suggesting a standardized treatment approach. To conclude, disseminated CNS helminthic infections, although rare, should be considered in the differential of demyelinating disease, particularly in patients with compelling travel history who present with atypical radiographic or clinical findings.

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

D. Long discloses as having received financial compensation for advisory board for Genentech. K. Green has no relevant disclosures. T. Derani discloses as having received consulting fees from Alexion and Genzyme. N. Decker has no relevant disclosures. R.J. Pace discloses being advisory faculty/member, speaker, and consultant for Genzyme, Genentech, Novartis, Biogen, Celgene, and Bayer. R. Aburashed discloses being advisory faculty/member, speaker, and consultant for Genzyme, Genentech, Novartis, Biogen, EMD Serono, and Celgene. Additional advisory faculty appointments include Bayer and Mallinckrodt. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Graeff-Teixeira C, da Silva AC, Yoshimura K. Update on eosinophilic meningoencephalitis and its clinical relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009;22:322–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pien FD, Pein BC. Angiostrongylus cantonensis eosinophilic meningitis. Int J Infect Dis 1999;3:161–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy GS, Johnson S. Clinical aspects of eosinophilic meningitis and meningoencephalitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the rat lungworm. Hawaii J Med Public Health 2013;72(6 suppl 2):35–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuberski T, Wallace GD. Clinical manifestations of eosinophilic memingitis due to Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Neurology 1979;29:1566–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanpittaya J, Jitpimolmard S, Tiamkao S, Mairiang E. MR findings of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis attributed to Angiostrongylus cantonensis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:1090–1094. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qvarnstrom Y, Xayavong M, da Silva AC, et al. . Real-time polymerase chain reaction detection of Angiostrongylus cantonensis DNA in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with eosinophilic meningitis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016;94:176–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]