Abstract

Objective

To describe the clinical features of late-onset (≥50 years) neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (LO-NMOSD), to compare the outcome with that of early-onset (EO-NMOSD), and to identify predictors of disability.

Methods

A retrospective, multicenter study of 238 patients with NMOSD identified by the 2015 criteria. Clinical and immunologic features of patients with LO-NMOSD were compared with those with EO-NMOSD. All patients were evaluated for aquaporin-4 (AQP4-IgG) and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG-IgG) antibodies.

Results

Sixty-nine (29%) patients had LO-NMOSD. Demographic features, initial disease presentation, annualized relapse rate, and frequency of AQP4-IgG and MOG-IgG did not differ between patients with LO-NMOSD and EO-NMOSD. Among patients with AQP4-IgG or double seronegativity, those with LO-NMOSD had a higher risk to require a cane to walk (hazard ratio [HR], 2.10, 95% CI 1.3–3.54, p = 0.003 for AQP4-IgG, and HR, 13.0, 95% CI 2.8–59.7, p = 0.001, for double seronegative). No differences in outcome were observed between patients with MOG-IgG and LO-NMOSD or EO-NMOSD. Older age at onset (for every 10-year increase, HR 1.63, 95% CI 1.35–1.92 p < 0.001) in NMOSD, and higher disability after the first attack (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.32–2.14, p < 0.001), and double seronegativity (HR 3.74, 95% CI 1.03–13.6, p = 0.045) in LO-NMOSD were the main independent predictors of worse outcome.

Conclusions

Patients with LO-NMOSD have similar clinical presentation but worse outcome than EO-NMOSD when they are double seronegative or AQP4-IgG positive. Serostatus and residual disability after first attack are the main predictors of LO-NMOSD outcome.

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is an inflammatory autoimmune disease that preferentially affects the optic nerve and the spinal cord.1 The identification of immunoglobulin G aquaporin-4 antibodies (AQP4-IgG) expanded the clinical syndromes associated with the disorder and led more recently to define new diagnostic criteria based on the presence or absence of AQP4-IgG.2 Cohort studies using sensitive assays have shown that up to 80% of the patients are seropositive for AQP4-IgG,3,4 and almost half of the seronegative patients who fulfill the 2015 NMOSD criteria are seropositive for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies (MOG-IgG).4,5

NMOSD usually presents in the fourth decade with a female predominance.6 However, sex frequency, age of presentation, and clinical outcome may depend on the presence or absence of glial cell antibodies (serostatus). For example, the female predominance does not occur in MOG-IgG patients or elder patients with AQP4-IgG,4,5 and older age at onset seems to associate with worse outcome in AQP4-IgG patients.5,7 Although the importance of the age at onset has been emphasized in a few studies that compared patients with late-onset NMOSD (LO-NMOSD, disease onset ≥50 years) with those with early-onset NMOSD (EO-NMOSD, <50 years), the information provided was limited to patients who fulfilled the former 2006 criteria,8 or were AQP4-IgG seropositive,9,10 or combined both groups of features.11

To address the effect of older age at NMOSD presentation, we reviewed our series of LO-NMOSD to describe the clinical features, to compare the outcome with that of EO-NMOSD, and to identify predictors of disability.

Methods

Case selection and data collection

Clinical information and samples for this observational, retrospective, multicenter study were collected from 60 centers through the Spanish NMO study group of the Spanish Society of Neurology, the Spanish MS Network (Red Española de Esclerosis Múltiple), and the Catalan Society of Neurology from January 2013 to January 2018.4,5 A total of 238 patients diagnosed with NMOSD according to the 2015 criteria2 were included. Epidemiologic data, including demographic, clinical, CSF (cell count and oligoclonal bands), and MRI findings (brain MRI classified as normal and abnormal with or without the Paty or Barkhof criteria and extension of spinal cord lesions), treatment, and outcome, were obtained from medical records and information collected from referring neurologists through a structured questionnaire designed for NMOSD as reported.4

All serum samples were tested for AQP4-IgG by an in-house cell-based assay with live HEK293 cells transfected with the aquaporin-4-M23 isoform, and for MOG-IgG with HEK293 cells transfected with the full-length MOG C-terminally fused to EGFP, as reported.12,13 Relapses were defined as new neurologic symptoms lasting at least 24 hours and accompanied by new neurologic findings, occurring 30 days after the previous attack. The outcome reached after the first attack and at last follow-up visit was evaluated by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score.14 An EDSS score of 6.0 was attributed when the patient required intermittent or unilateral assistance to walk 100 m with or without resting and an EDSS score of 8.0 when the patient was restricted to bed or chair or perambulated in wheelchair but retained many self-care functions. Severe visual disability was defined as sustained visual acuity ≤20/100 with best correction possible during at least 6 months after an optic neuritis attack.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clinic, and written consent was obtained for all participants. Samples were deposited in a registered biobank of the Institut d'Investigació Biomèdica August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain.

Statistical methods

Characteristics between patients with LO-NMOSD and EO-NMOSD were compared using χ2 (or Fisher exact) tests for categorical data and Student t test (or Wilcoxon rank-sum test) for continuous data. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the time to first recurrence and to reach an EDSS score of 6.0. Predictive factors for disability were assessed with Cox proportional hazards regression models. In the entire cohort, sex, ethnicity, age at onset, type of initial attack, residual disability after the first event, annualized relapse rate (ARR), and serostatus were included as predictive factors for disability. To increase power, we combined African, Asian, and Hispanic ethnicities in a unique group (“nonwhite ethnicity”), and regarding the onset attack type, we combined brainstem and brain in the same group. Chronic therapy was also included in the analysis as a time-dependent covariable. Two-sided p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0.

Data availability

Data from patients reported within the article are available and will be shared anonymously by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

Demographic, clinical, and serologic characteristics of the cohort

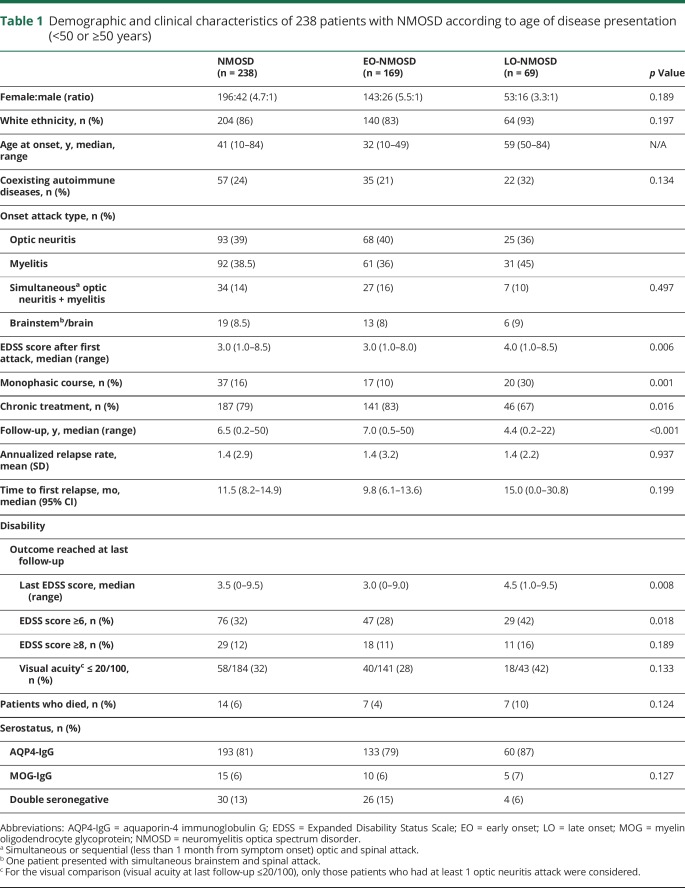

Clinical and demographic data of the 238 patients, according to the age at disease onset, are summarized in table 1. Patients with LO-NMOSD were mainly white (93%) and female (76.8%) and had a nonsignificant lower female:male ratio compared with that of the EO-NMOSD group (3.3:1 vs 5.5:1). The types and frequency of the initial attack were not significantly different between both groups, but the EDSS score after the first attack was higher in patients with LO-NMOSD (p = 0.006) (table 1). At the last follow-up, patients with LO-NMOSD remained with a higher EDDS score (p = 0.008) and more frequently required at least a cane to walk (42% vs 28%, p = 0.018), although the time of follow-up of these patients was shorter (p < 0.001). The serologic distribution was not significantly different in both groups of patients (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 238 patients with NMOSD according to age of disease presentation (<50 or ≥50 years)

Although the age threshold between the 2 groups (50 years) appears to be arbitrary, it was supported by further analyzing the data in 3 age groups (e-Results, links.lww.com/NXI/A140).

Predictors for development of disability in LO-NMOSD

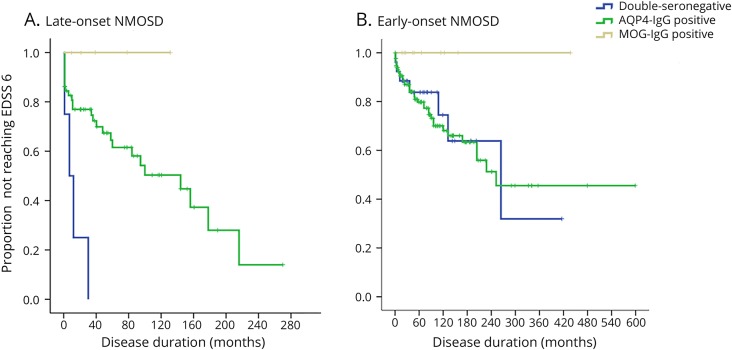

We first investigated the contribution of the age at onset for development of disability in the entire cohort of patients with NMOSD. We found that for every 10-year increase in age at disease onset, the risk of requiring a cane to walk (EDSS score of 6.0) increased by 63% (hazard ratio [HR] 1.63, 95%CI 1.35–1.92, p < 0.0001). Other significant predictors identified in the multivariate analysis were a higher EDSS score after first attack (HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.19–2.07, p = 0.001) and the ARR (HR 1.58, 95% CI 1.12–2.24, p = 0.009). Then, we investigated whether sex, EDSS score after first attack, ARR, and serostatus affected development of disability in LO-NMOSD. We found that the risk to reach an EDDS score of 6.0 increased with a higher residual disability after the first attack (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.32–2.13, p = 0.0001), and a double seronegativity increased 3.74-fold the risk compared with AQP4-IG seropositivity (HR 3.74, 95% CI 1.03–13.6, p = 0.045). These effects remained after including in the model ethnicity or type of onset attack instead of sex. Comparative estimates for MOG-IgG patients were not possible because none of them reached the EDSS score of 6.0. Time to EDSS score of 6.0 by serostatus in LO-NMOSD and EO-NMOSD is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Months from onset to use a cane (EDSS score of 6.0) by serostatus in: (A) patients with late-onset NMOSD: double-seronegative patients reached the EDSS score of 6.0 sooner than AQP4-IgG-positive (p = 0.001) and MOG-IgG-positive patients (p = 0.006); (B) patients with early-onset NMOSD: a trend to lower risk of disability was seen in MOG-IgG-positive patients compared with AQP4-IgG-positive and double-seronegative patients (p = 0.054), but no differences were seen among double-seronegative and AQP4-IgG-positive patients (p = 0.433).

AQP4 = aquaporin-4; EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale; MOG = myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; NMOSD = neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder.

Demographic and clinical differences between LO-NMOSD and EO-NMOSD with AQP4-IgG

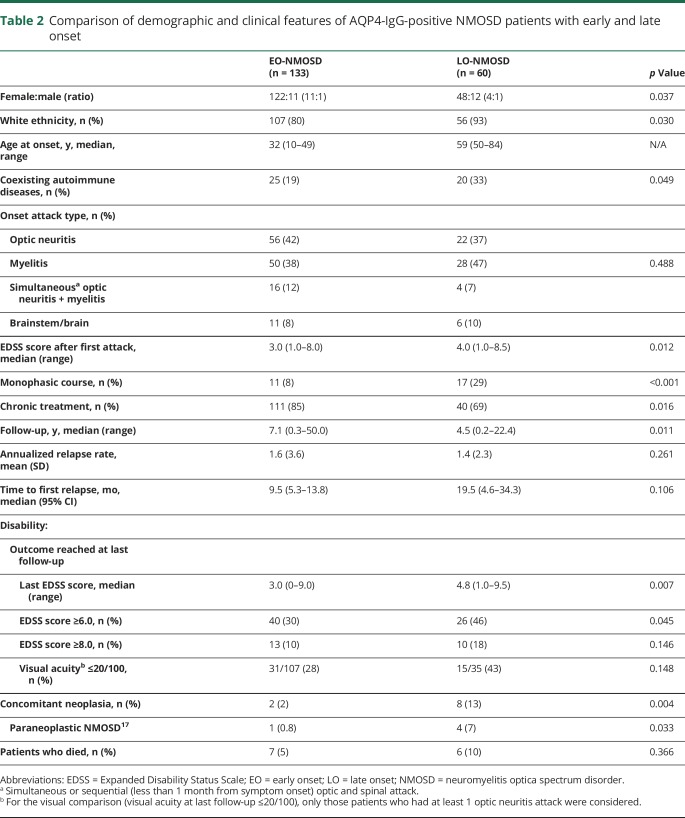

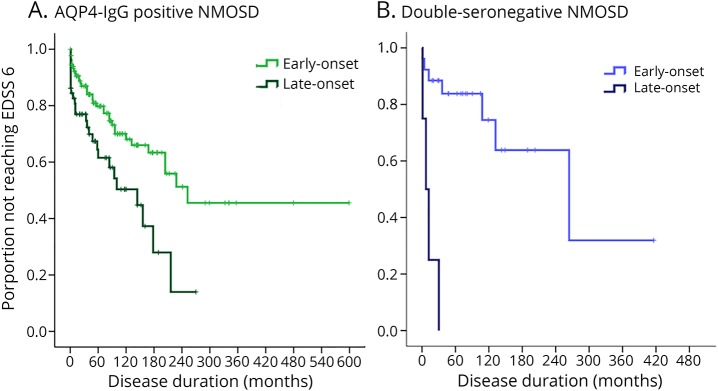

Sixty of the 193 (31%) patients with AQP4-IgG had an LO-NMOSD. Compared with patients with EO-NMOSD, those with LO-NMOSD had a lower female:male ratio (11:1 vs 4:1, p = 0.037), a higher frequency of white ethnicity (p = 0.030), and coexisting autoimmune diseases (p = 0.049) (table 2). Patients with LO-NMOSD had a higher EDSS score after the first attack (p = 0.012) and at the last follow-up compared with those with EO-NMOSD (median 4.8 vs 3.0, p = 0.007). However, the time to first relapse, the ARR (table 2), the frequency and type of acute-phase treatment, and the time to first therapy were not significantly different (e-Results, links.lww.com/NXI/A140). Patients with LO-NMOSD doubled the risk to reach an EDSS score of 6.0 compared with those with EO-NMOSD (HR 2.10, 95% CI 1.30–3.54, p = 0.003). Time to EDSS score of 6.0 in the entire cohort of patients with NMOSD and AQP4-IgG is shown in figure 2A. Four (7%) patients with LO-NMOSD were diagnosed with paraneoplastic NMOSD compared with 1 (0.8%) patient and EO-NMOSD (p = 0.033) (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic and clinical features of AQP4-IgG-positive NMOSD patients with early and late onset

Figure 2. Months from onset to use a cane (EDSS score 6.0) by age at onset: (A) in AQP4-IgG-positive NMOSD patients: at 60 months (5 years) after onset, 38% of patients with late-onset NMOSD and 21% of those with early-onset were expected to need a cane to walk (p = 0.003); (B) in double-seronegative NMOSD patients: at 60 months (5 years) after onset, 100% of patients with late-onset NMOSD and 12% of patients with early-onset NNMOSD were expected to use a cane (p < 0.001).

AQP4 = aquaporin-4; EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale; NMOSD = neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder.

Demographic and clinical differences between LO-NMOSD and EO-NMOSD with MOG-IgG

Five of the 15 (33%) patients with MOG-IgG had an LO-NMOSD. Sexes were almost equally represented among patients with LO-NMOSD and EO-NMOSD. The median age at onset was 51 years (range 50–62 years) for LO-NMOSD and 20 years (range 17–44 years) for EO-NMOSD. There were no differences between the 2 groups of patients in other demographic or clinical features including ARR, disability after the first attack, and acute and chronic therapy (e-Results, links.lww.com/NXI/A140). At the last follow-up, the median EDSS score was 2.0 (range 1.5–5.5) for LO-NMOSD patients and 1.3 (range 0–3.5) for EO-NMOSD. Thus, none of the patients with LO-NMOSD or EO-NMOSD and MOG-IgG reached the EDSS score of 6.0.

Demographic and clinical differences between LO-NMOSD and EO-NMOSD with double seronegativity

Four of the 30 (13%) patients with double seronegativity had an LO-NMOSD. Sexes were equally represented in both groups. The median age at onset was 59 years (range 52–63 years) for LO-NMOSD and 32 years (range 10–49 years) for EO-NMOSD. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups of patients in other demographic or clinical features including ARR and acute and chronic therapy (e-Results, links.lww.com/NXI/A140). The EDSS scores after the first attack (median 6.0 vs 3.0) and at the last follow-up (median 6.3 vs 4.0) were not significantly different between LO-NMOSD and EO-NMOSD. The risk to reach an EDSS score of 6.0 was increased by 13-fold for patients with LO-NMOSD compared with those with EO-NMOSD (HR, 13.0, 95% CI 2.8–59.7 p = 0.001). Time to EDSS score of 6.0 in the entire cohort of patients with NMOSD who were double seronegative is shown in figure 2B.

Demographic and clinical differences of patients with LO-NMOSD according to antibody status

Patients with AQP4-IgG had a nonsignificant higher female:male ratio (4:1) than those with MOG-IgG (1.5:1) and double seronegative cases (1:1). Simultaneous occurrence of optic neuritis and myelitis was more frequent in patients with MOG-IgG (40%) than in double-seronegative (25%) or patients with AQP4-IgG (7%) (p = 0.076). At the last follow-up, patients with MOG-IgG had a trend toward a lower EDSS score than patients with AQP4-IgG and double-seronegative cases (median 2.0, 4.8, and 6.3, respectively, p = 0.087), despite that the number of relapses or the acute and chronic treatment received did not differ significantly between groups (e-Results, links.lww.com/NXI/A140).

Discussion

This study of a large cohort of patients with NMOSD diagnosed by the 2015 criteria and sensitive antibody assays shows that the disease presents after age 50 years in 29% of the patients. Patients with LO-NMOSD have a worse outcome compared with those with EO-NMOSD despite having similar demographic, clinical, and serologic features (∼80% AQP4-IgG positive). This worse outcome, however, applies to patients with AQP4-IgG or who are double seronegative but not to those with MOG-IgG. The study also identifies that besides the age at onset, the serostatus and a worse recovery from the first attack are independent predictors of having ambulatory disability in LO-NMOSD.

A few studies have identified the effect of age at disease onset on motor disability4,7,11,15 and worse outcome.8,10 However, the information was based on studies that only included patients with AQP4-IgG,8,9 or those who fulfilled the 2006 criteria,11 or did not take into account the full serostatus of the disorder.10 Our study overcomes these limitations and confirms the robust association of LO-NMOSD with more severe disability. The reasons for the different outcome depending on the age at disease onset are not clear. It has been reported that patients with LO-NMOSD develop more frequently longitudinally extensive myelitis, and this presentation carries a worse outcome when it associates with AQP4-IgG15; however, we did not find significant clinical differences (onset attack type, ARR, or time to first relapse) between both groups of patients regardless of the serostatus or when the analysis was limited to patients with AQP4-IgG. Moreover, our study rules out that the effect on disability was related to a different frequency of serologic distribution in both groups of age.16

The association of older age with a lower or impaired mechanism of reparation has also been suggested in some reports.11 Our study provides evidence for this hypothesis because we found that the age and a worse recovery from the first attack were the main predictor factors of disability. However, this was not the case for patients who presented with MOG-IgG because they had a similar prognosis regardless of the age at onset. A note of caution, this refers only to patients with MOG-IgG who met the NMOSD criteria and cannot be generalized to MOG-IgG-associated disease that has a much wider clinical spectrum.13 In addition, we cannot rule out that age-related comorbidity contributed to the outcome, but this factor would not explain the similar disability outcome between patients with MOG-IgG and EO-NMOSD or LO-NMOSD. The fact that patients received as acute treatment similar types of immunotherapy and plasma exchange, and that the time from disease onset to therapy initiation was not significantly different among the 3 groups of patients with LO-NMOSD and EO-NMOSD, emphasize the importance of serostatus as a contributing factor to the outcome.

We and others reported that patients with AQP4-IgG or those who were seronegative had similar clinical profiles in terms of relapses and disability.3,4 The current findings show that in the setting of an LO-NMOSD to be double seronegative confers even a worse outcome than the associated with AQP4-IgG. These data should be taken with caution, given that the number of double seronegative patients was small, and therefore, the collected information may be prone to selection bias. Further studies are needed to confirm this observation.

It is noteworthy that the frequency of maintenance therapy was lower in patients with LO-NMOSD than those with EO-NMOSD; however, it was only significant for patients with AQP4-IgG, and therefore, this fact would not explain the different outcome associated with double seronegativity. The fact that the maintenance therapy was not significantly associated with the outcome is in line with a recent report that included a large multicenter cohort of AQP4-IgG-positive NMOSD patients7 and would support the role of a worse recovery in older patients and the accumulation of disability due to relapses. We have shown that the latter was identified as an independent risk factor in the entire NMOSD cohort.

Another finding that warrants more detailed studies is the detection of concomitant history of cancer in patients with NMOSD; in our study, the 10 (4%) patients identified had AQP4-IgG, 8 of them had an LO-NMOSD, and 4 of the 5 patients who fulfilled the criteria of paraneoplastic NMOSD belonged to this group.17 The frequency of cancer in our cohort, and their identification in patients older than 50 years, was within the reported range in NMOSD.18

Our study has the limitation of being retrospective and containing a small number of AQP4-IgG-seronegative patients. However, the findings of this large cohort of patients confirm that patient's age at onset of NMOSD is a predictive factor of disability with a worse outcome for those who have LO-NMOSD and demonstrate that patient's serostatus is important to consider when assessing the risk to develop ambulatory disability.

Glossary

- AQP4

aquaporin-4

- ARR

annualized relapse rate

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- EO-NMOSD

early-onset neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder

- HR

hazard ratio

- LO-NMOSD

late-onset neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

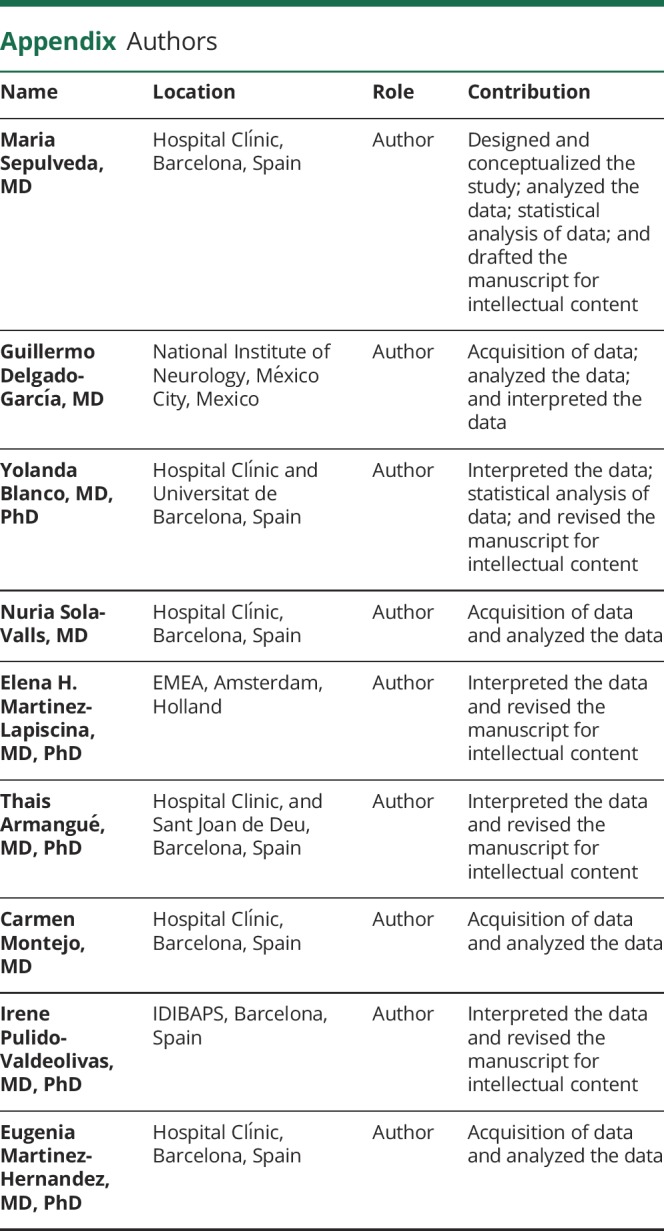

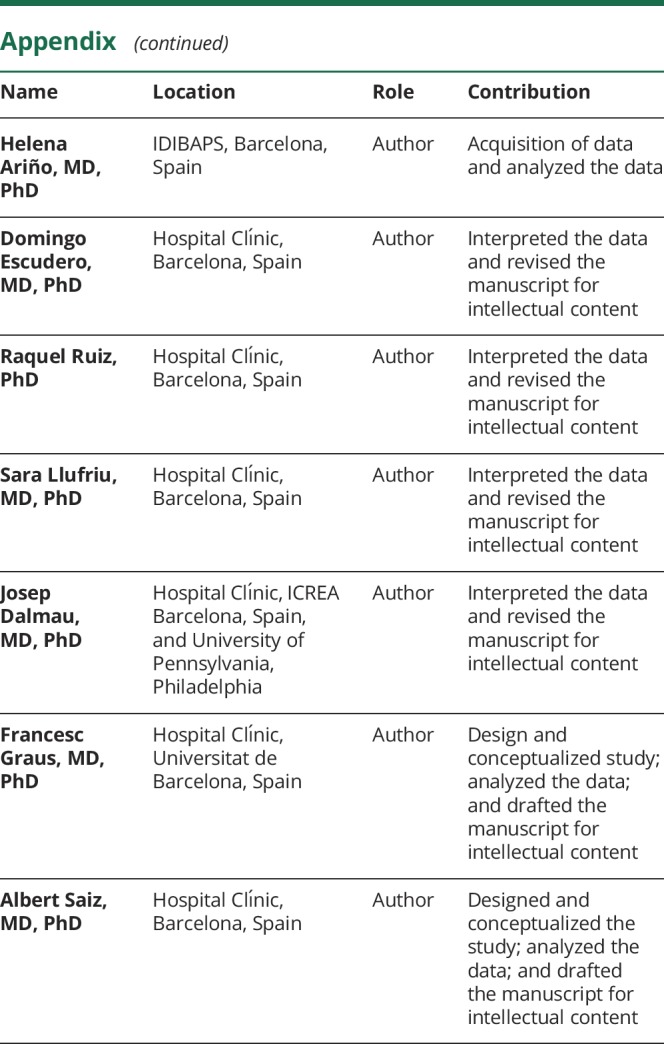

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

This work was supported in part by Red Española de Esclerosis Múltiple (REEM) (RD16/0015/0002; RD16/0015/0003) integrated in the Plan Estatal I+D+I and cofunded by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER, “Otra manera de hacer Europa”).

Disclosure

M. Sepulveda received speaking honoraria from Sanofi, Novartis, and Biogen and receives funding from the Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya (SLT002/16/00354). G. Delgado-García reports no disclosures. Y. Blanco received speaking honoraria from Biogen, Novartis, and Genzyme. N. Sola-Valls received speaking honoraria from Sanofi, Bayer Schering, Novartis, and Biogen Idec and receives funding from the Spanish Government (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional [FEDER] and the Predoctoral Grant for Health Research (FI16/00251). E. Martinez-Lapiscina is working at European Medicines Agency and is a researcher in the OCTIMS study, an observational study (that involves no specific drugs) to validate SD-OCT as a biomarker for MS, sponsored by Novartis. She received speaker honoraria from Biogen, Roche, Novartis, and Sanofi and a travel reimbursement from Biogen, Roche, Novartis, and Sanofi. She received funding from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spain) and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER—JR16/00006; RD16/0015/0002), Grant for MS Innovation, Fundació Privada Cellex, and Marató TV3 Charitable Foundation. T. Armangué received speaker honoraria from Novartis. C. Montejo reports no disclosures. I. Pulido-Valdeoliva received travel reimbursement from Roche and Genzyme, and she holds stock options in Aura Innovative Robotics. E. Martinez-Hernandez receives funding from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spain) (JR17/00012). H. Ariño, D. Escudero, and R. Ruiz-García report no disclosures. S. Llufriu received speaking honoraria from Biogen Idec, Novartis, Teva, Genzyme, and Merck and receives research support from the Spanish Government (PI15/00587). J. Dalmau receives royalties from Athena Diagnostics for the use of Ma2 as an autoantibody test and from Euroimmun for the use of NMDA as an antibody test. He received a licensing fee from Euroimmun for the use of GABAB receptor, GABAA receptor, DPPX and IgLON5 as autoantibody tests; he has received an unrestricted research grant from Euroimmun. He is editor of Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation. F. Graus received a licensing fee from Euroimmun for the use of IgLON5 as an autoantibody test and honoraria from MedLink Neurology as Associate Editor. A. Saiz received compensation for consulting services and speaking honoraria from Bayer Schering, Merck Serono, Biogen Idec, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva, Roche, and Novartis. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology 2015;85:177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiao Y, Fryer JP, Lennon VA, et al. Updated estimate of AQP4-IgG serostatus and disability outcome in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2013;81:1197–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sepúlveda M, Armangué T, Sola-Valls N, et al. Neuromyelitis óptica spectrum disorders. Comparison according to the phenotype and serostatus. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2016;3:e225 doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sepúlveda M, Aldea M, Escudero D, et al. Epidemiology of NMOSD in Catalonia: influence of the new 2015 criteria in incidence and prevalence estimates. Mult Scler 2018;24:1843–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandit L, Asgari N, Apiwattanakul M, et al. Demographic and clinical features of neuromyelitis optica: a review. Mult Scler 2015;21:845–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palace J, Lin DY, Zeng D, et al. Outcome prediction models in AQP4-IgG positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Brain 2019;142:1310–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao Z, Yin J, Zhong X, et al. Late-onset neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder in AQP4-seropositive patients in a Chinese population. BMC Neurol 2015;15:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seok JM, Cho HJ, Ahn SW, et al. Clinical characteristics of late-onset neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a multicenter retrospective study in Korea. Mult Scler 2017;23:1748–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang LJ, Yang LN, Li T, et al. Distinctive characteristics of early-onset and late-onset neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Int J Neurosci 2017;127:334–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collongues N, Marignier R, Jacob A, et al. Characterization of neuromyelitis optica and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder patients with a late onset. Mult Scler 2014;20:1086–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Höftberger R, Sepulveda M, Armangue T, et al. Antibodies to MOG and AQP4 in adults with neuromyelitis optica and suspected limited forms of the disease. Mult Scler 2015;21:866–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedreño M, Sepúlveda M, Armangué T, et al. Frequency and relevance of IgM, and IgA antibodies against MOG in MOG-IgG-associated disease. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019;28:230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983;33:1444–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitley J, Leite MI, Nakashima I, et al. Prognostic factors and disease course in aquaporin-4 antibody-positive patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder from the United Kingdom and Japan. Brain 2012;135:1834–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quek AM, McKeon A, Lennon VA, et al. Effects of age and sex on aquaporin-4 autoimmunity. Arch Neurol 2012;69:1039–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sepúlveda M, Sola-Valls N, Escudero D, et al. Clinical profile of patients with paraneoplastic neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and aquaporin-4 antibodies. Mult Scler 2018;24:1753–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beauchemin P, Iorio R, Traboulsee AL, Field T, Tinker AV, Carruthers RL. Paraneoplastic Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder: a single center cohort description with two cases of histological validation. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018;20:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data from patients reported within the article are available and will be shared anonymously by request from any qualified investigator.