Abstract

Background:

Yoga has been shown useful in reducing chronic low back pain (CLBP) through largely unknown mechanisms. The aim of this pilot study is to investigate the feasibility of providing yoga intervention to a predominantly underserved population and explore the potential mechanisms underlying yoga intervention in improving CLBP pain.

Methods:

The quasi-experimental within-subject wait-listed crossover design targeted the recruitment of low-income participants who received twice-weekly group yoga for 12 weeks, following 6–12 weeks of no intervention. Outcome measures were taken at baseline, preintervention (6–12 weeks following baseline), and then postintervention. Outcome measures included pain, disability, core strength, flexibility, and plasma tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α protein levels. Outcomes measures were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and paired one-tailed t-tests.

Results:

Eight patients completed the intervention. Significant improvements in pain scores measured over time were supported by the significant improvement in pre- and post-yoga session pain scores. Significant improvements were also seen in the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire scores, spinal and hip flexor flexibility, and strength of core muscles following yoga. Six participants saw a 28.6%–100% reduction of TNF-α plasma protein levels after yoga, while one showed an 82.4% increase. Two participants had no detectable levels to begin with. Brain imaging analysis shows interesting increases in N-acetylaspartate in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and thalamus.

Conclusion:

Yoga appears effective in reducing pain and disability in a low-income CLBP population and in part works by increasing flexibility and core strength. Changes in TNF-α protein levels should be further investigated for its influence on pain pathways.

Keywords: Brain imaging, chronic low back pain, core strength, flexibility, tumor necrosis factor-α, yoga

Introduction

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is the most common cause of chronic pain in the United States, with over 100 billion dollars spent annually managing it.[1] Many people seek medical help including rehabilitation, surgery, and pharmacological treatments, but continue to experience extensive pain, disability, and functional limitations.[2] Maladaptive pain coping affects the outcome of different treatments.[3] Pain and fear of aggravating symptoms can be limiting factors to participation in a regular exercise program.[4,5] Alternative approaches to decrease pain and facilitate return of function would be valuable and cost-effective.

Yoga appears to be a safe self-management intervention for participants with CLBP.[6] Many studies have shown yoga decreases pain and/or disability in people with CLBP. Participants have a significantly greater reduction in pain intensity and pain medication use following 12 weeks of a yoga program than those receiving usual care.[7] Yoga offers a holistic approach for people with various physical dysfunctions because it incorporates body awareness, breathing activities, physical posture, and meditation that have additional biopsychosocial benefits. Many intervention sessions were held over 12 weeks with significant changes in the outcome measures.[8,9,10,11] The delivery of yoga reported has overwhelmingly been in group sessions led by a yoga instructor with infrequent adverse effects.[6,12]

Individuals with CLBP have poor core stability, altered lumbopelvic posture, muscle imbalance, and faulty movement. Posture becomes mechanically faulty with an imbalance of tight and weak musculature that could benefit from activity such as yoga that targets both flexibility and strengthening. In addition, functional CLBP-related disability can have a high psychological impact, but there are few studies investigating full interplay of biopsychosocial factors and fewer yet, investigating potential mechanisms. Yoga is proposed to play a role in health by reversing the psychoimmunology of emotions.[13] The mechanism in which it works is unknown. Eight weeks of yoga training have been shown to significantly reduce serum levels of inflammatory markers including interleukin (IL)-6 in those with chronic heart failure.[14] Healthy control participants had constant tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels, while participants with CLBP who received a multidisciplinary intervention had decreased levels at a 6-month follow-up.[15] However, there are competing studies suggesting that yoga practice does not alter circulating TNF-α levels in healthy or working individuals.[16,17]

CLBP is associated with changes in brain chemistry in somatosensory, motor, dorsolateral prefrontal, and anterior cingulate cortices,[18,19,20,21,22] but no study has examined the effects of yoga on neurochemicals such as N-acetylaspartate, (NAA), a neuronal marker. The thalamus is important in mediating nociceptive inputs to the cortex, but studies have shown contradicting findings regarding changes in the gray matter volume of the thalamus.[23]

Low-income minorities with chronic pain have decreased access to treatment, which causes more disability and increases costs.[24] There is evidence that implementing a yoga program is feasible in minority populations. Retention was excellent throughout a 12-week intervention period (97%) and long-term retention was 77% in a group of 30 minority adults with moderate-to-severe CLBP.[7] A larger study reported 44%–65% of 95 CLBP participants attended once or twice weekly yoga classes for 12 weeks with a median attendance of 10–16 classes, respectively,[25] and showed effectiveness of yoga was generalized to a racially diverse, low-income population. Patients seen in safety net clinics usually do not have adequate medical coverage; thus, providing yoga as a self-management strategy is a way to address barriers and the overall health management cost in the underinsured.

The objective of this pilot study was to investigate the feasibility and potential physical and physiological mechanisms underlying yoga intervention in improving pain and function in a predominantly underserved population suffering with CLBP. Specifically, we investigated pain, disability, and the physical measures of core strength and lumbopelvic flexibility. The secondary objective was to explore potential contributions of the immune and central nervous system biomarkers of TNF-α and NAA in decreasing pain as the result of yoga intervention. Given the comprehensive nature of yoga treatment that includes breathing, meditation, and postures for core strengthening and flexibility, we hypothesized that yoga will improve pain, disability, and muscle flexibility and strength, and alter the immune and central nervous systems biomarkers.

Methods

This study was a prospective quasi-experimental within-subject wait-listed control design of 6–12 weeks of no intervention followed by 12 weeks of yoga intervention. The study was approved by and followed the University's Institutional Review Board guidelines.

Participants were recruited from the hospital's family medicine clinic and word of mouth. Inclusion criteria included: history of CLBP (>3 months), pain intensity of at least 3 (on a 0–10 pain scale) and at least minimum disability (30% or more per Oswestry Disability Scale), Folstein Mini-Mental State Exam score >24, and English comprehending individuals naïve to structured yoga practice.

Exclusion criteria included: current pregnancy, glaucoma, significant or chronic decline in immune function, spinal fusion or other orthopedic surgery in the past 6 months, history of chronic neurological disorders (e.g., stroke, dementia), inability to make regular time commitments, and lack of transportation to scheduled yoga sessions. Informed written consent was obtained prior to the initial assessment.

Participants passing the standard magnetic resonance exclusion criteria were included in the brain scanning portion of the study.

Procedures

Assessments were conducted at three points: baseline (initial), the week prior to beginning the yoga intervention after 6–12 weeks of wait period of no-intervention (pre-intervention), and the week following the last yoga session (post-intervention). Brain scans were conducted pre- and post-intervention only on a small cohort of participants who met the criteria.

Assessments

A medical questionnaire was completed first, blood drawn second, and outcome measures completed in random order of questionnaires and then flexibility followed by core strength. The primary outcomes were pain, disability, muscle strength, and flexibility. An 11-point Numeric Rating Scale indicated pain intensity[26] and the Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire was used to measure disability.[27] Isometric core strength was measured for back extensors, upper abdominals, and lower abdominals by recording hold time for each position.[28] Spinal range of motion (ROM) during a forward bend was measured by the distance from fingertips to floor bending forward without bending at the knees.[29] Hip flexibility included standard goniometric measures of the hamstrings during a straight leg raise and the hip flexors measured in side lying. Outcome assessments were completed by blinded research personnel.

Immune biomarker

TNF-α levels were obtained from 5 ml standard blood draws into nonheparinized covered test tubes that were immediately cooled and processed for serum using standard protocol with final storage at −80°F. Serum protein levels were determined by protein assay analysis using a commercial ELISA kit (ALPCO, Salem, NH).

Brain spectroscopy

Brain images were acquired with a 3 Tesla scanner (Skyra scanner; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). Each scan comprised structural MR and MR spectroscopy images, using previously published protocol[20] with the total acquisition time of about 60 min. MR spectroscopy included two imaging slabs, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), and thalamus using a developed protocol.[20] Two univoxel DLPFC slabs were selected in the frontal lobe (Brodmann area 46) representing the right and left side and sampling both white and gray matter. Similarly, two univoxel thalamus slabs (right and left sides) were identified from the anatomical landmarks. Acquisition time for each slab was approximately 10 min. Neurochemical concentration of NAA was analyzed according to previously published protocol.[20]

Intervention

Hatha yoga sessions with a therapeutic focus were held two times weekly for 60 min sessions directed by a certified master yoga instructor. Each session began with deep breathing exercises and relaxation techniques progressing to poses designed to begin with stretching and move into strengthening [Table 1]. The session ended with meditative relaxation. The first weekly session emphasized restorative poses and the second session was more movement based. The predesigned yoga program progressed from simple to more challenging poses over the 12-week course. Modification for restricted movement or painful positions was provided as needed. Safety issues were monitored using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0.

Table 1.

Yoga program

| Yoga sequence with primary rationale, reference for the first mention, and time for each yoga session | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks | First class: Restorative | Minutes | Second class: Basics | Minutes |

| 1 | Opening: Discuss class objectives and introductions Sequence: | 10 | Opening: Check-in (how is everyone feeling emotionally and mentally/pain levels and location) Sequence: | 7-10 |

| a. V-Pac Series-Pelvic floor only in supine for awareness of pelvic floor contraction in preparation for breathing exercise, engagement of multifidi, and engagement of PNS[54] | 2-3 | a. Durgha Pranayama | 5-7 | |

| b. Durgha (elevator or diaphragmatic) breathing in supine for activation of PNS and mindfulness of breath awareness[55,58] | 5 | b. 3-Part V-Pac Series engages pelvic floor, transverse abdominis and rectus abdominis (Mula and Udyyana Bandha) | 5-7 | |

| c. Windshield wiper pose (3 phases: Feet together, feet hip width apart and feet more than hip width apart) for disc hydration for 10 breaths[57] | 2 | c. Seven Stretches of the spine in sitting position (axial extension then spinal flexion and extension, then lateral flexion both sides, and then spinal rotation both sides)[55] | 10-15 | |

| d. Legs up incline a variation of legs on chair using two yoga blocks and bolster for incline at 45° with 2/4 count breath for LBP relief[58] | 15 | d. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in basic relaxation pose in supported supine[58] | 20 | |

| e. Savasana continued in legs up incline pose for mindfulness and relaxation allowing work done to integrate into CNS[58] | 10 | Discussion and education infused with each pose not included in time listed | ||

| f. Switch to Savasana with legs on chairs ending with simple twist to realign spine | 15 | |||

| 2 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 7-10 | Opening: Check-in and education on breathing and stabilization Sequence: | 2-3 |

| a. Durgha Pranayama | 5-7 | a. Softball breathing is visualization to extend and lengthen breath to focus on puraka, rechaka, and kumbhaka[55] | 5 | |

| b. 3-Part V-Pac series in supine add pelvic tilt to activate TFL and stretch rectus femoris | 5-7 | b. Alternating spinal balance in all fours position to activate multifidi, abdominal muscles and pelvic floor muscles for stabilization[54] | 10 | |

| c. Gyan Mudra[59] for mental clarity, focus, and calm in Sukhasana (Easy Seated Pose) position with strap around thoracic spine and under front of patella to meditate with adaptation for LBP[60,61] | 7 | c. Seven stretches of the spine | 10 | |

| d. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in supported sidelying[58] | 20 | d. Tadasana incorporating V-Pac series for postural awareness to focus postural stability[54,62] | 5 | |

| e. Setu Banda Sarvangasana (Supported Bridge variation) in supine with hips over bolster or block in bridge position for psoas relaxation[53] | 7-10 | |||

| f. Savasana in basic relaxation supported supine starting with meditation: “I breathe in life and breathe out love” with pranayama | 5 | |||

| Then telling with monkey story for thought awareness. End with simple twist | 15 | |||

| 3 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 3-5 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 3-5 |

| a. Durgha Pranayama | 5-7 | a. Harmonium sound meditation-Bhakti Yoga introduction with chanting[56] | 5 | |

| b. 3-Part V-Pac series | 5-7 | b. Alternating spinal balance in all fours position | 10 | |

| c. Gyan Mudra in Sukhasana position with strap around thoracic spine | 5 | c. Seven stretches of the spine | 10 | |

| d. Tadasana incorporating V-Pac series | 5-7 | |||

| e. Corpse pose for relaxation and stress reduction | 15-20 | e. Supported bridge | 5-7 | |

| f. Savasana in in basic relaxation pose in supported supine with harmonium meditation | 15-20 | f. Savasana in in basic relaxation pose with harmonium meditation | 20 | |

| 4 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 7-10 | Cancellation due to inclement weather. Session made up at end | |

| a. Durgha Pranayama | 5-7 | |||

| b. 3-Part V-Pac series | 5-7 | |||

| c. Meditation in preferred supine or seated position using mirrored focus for visualization techniques for pain management | 5-7 | |||

| d. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in choice of supine legs on chair position with hips at 90° (Instant Maui) or legs on bolster positioned a top two blocks (Stonehenge) 45°-60° hip flexion for reduction of muscular fatigue, and lumbar muscle relaxation[54] | 20-25 | |||

| 5 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 7-10 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 3-5 |

| a. 3-part V-Pac series | 5-7 | a. 3-part V-Pac Series | 5-7 | |

| b. Windshield Wiper Pose | 2 | b. Seven stretches of the spine | 10 | |

| c. Savasana in Stonehenge position | 15-20 | c. Adho Mukha Savasana (Downward Facing Dog Pose) at the wall, bar, door with straps (Hanging Dog) for spine traction, paraspinal muscles stretch and relaxation[58] | 15 | |

| Elevated Supta Badha Konasana[58] | 15-20 | |||

| *All Savasana included 4/6 count breath (Visamavrtti Pranayama) to activate PNS | d. Virabhadrasana-1 (Warrior I) with hands on hips in partial extension - for low extremity alignment, spine stabilization through core strengthening (lower abdominal and gluteal engagement), and hip flexor stretching[54,55] | 10 | ||

| e. Simple twist before moving into Savasana with legs on chair | 15 | |||

| 6 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 5-7 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 7-10 |

| a. 3-Part V-Pac series | 5-7 | a. 3-Part V-Pac series in seated position | 5-7 | |

| b. Seven Stretches of the cervical spine[55] | 10 | b. Seven stretches of the spine in seated position | 10 | |

| c. Breathing Pidgeon Pose (Figure Four Stretch) for stretching/releasing piriformis and gluteals[54] | 10 | c. Ujjayi Breathing to slow breathing by relaxing CNS and engage abdomen incorporate into remaining poses[56] | 5-7 | |

| d. Supta Padangusthasana l with hamstring traction using straps to keep pelvis stable during hamstring stretching[54,60,65] | 15 | d. Virabhadrasana ll (Warrior 2) for low extremity alignment, strengthening external rotators, spine stabilization through core strengthening (lower abdominal and gluteal engagement), and hip flexor stretching standing[54,55] | 5-7 | |

| e. Simple twist before moving into Savasana with legs on chair or side lying | 15-20 | e. Ardha Uttitha Trikonasana (Half Triangle Pose) - First ½ of Triangle Pose in standing to keep pelvis stable actively during hamstring stretch while engaging gluteus medius and TFL[54,63] | 10 | |

| f. Surya Namaskar (Half sun salutation) to increase ROM and spinal flexibility, and to retrain breath with movement (breath through rather than holding breath)[55,62] | 7 | |||

| g. Seated twists to stretch piriformis and spinal ROM[54] | 5-7 | |||

| h. Savasana in preferred position | 20 | |||

| 7 | Opening: Check-in (7-10 min) Sequence: | 3-5 | Opening: Check-in (7-10 min) Stabilization in back-bending education Sequence: | 7-10 |

| a. Durgha Pranayama (5-7 min) | 5-7 | a. Seven stretches of the spine | 10 | |

| b. Breathing Pidgeon pose[54] | 20 | b. Bhujangasana (Cobra) and Sphynx variation to open chest, shoulders, and throat while lengthening the spine and increasing spinal flexibility. It also strengthens the low back, shoulders, and legs. Cobra pose can reduce mild depression, anxiety, and stress. Five breaths dynamically and five breaths statistically[61] | 5 | |

| c. Supta Padanghustasana with traction using strap for proprioceptive input encouraging alignment of the pelvis and creating space in the lumbar spine and strengthens lower abdominals and hip internal rotators[60] | 15 | |||

| d. Triangle with partners using strap to anchor the hip in place, helping with the extension of the lower side of the trunk[66] | 15 | |||

| e. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in preferred position | 15-20 | e. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in basic relaxation pose | 20 | |

| 8 | Cancellation due to inclement weather. Session made up at end | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 2-3 | |

| a. Samavrtti Pranayama in 3-Part V-Pac series×10[66] | 5 | |||

| b. Seven stretches of the spine | 5 | |||

| c. Plank knees down variation to engage obliques, abdominals, and shoulders. It also builds arm strength[54] | 5 | |||

| d. Cobra and Sphynx Variation | 5 | |||

| e. Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog) to strengthen the arms, legs, and torso while relieving LBP, and stretch the chest, back, hamstrings, calves, and feet. Relieves stress and mild anxiety and improves focus[61] | 5 | |||

| f. Ardhasourya Namaskar (Half Sun Salutation) to increases blood flow to muscle making tendons/ligaments more pliable[55,62] | 10 | |||

| g. Breathing Pigeon Pose | 5 | |||

| h. Janu Sirsasana (Head to Knee Forward Bend) to open chest while stretching calves, hamstrings, and lower back. It also relieves stress, anxiety, and mild depression[61] | 5 | |||

| i. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in position of own choice | 7 | |||

| 9 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 5-7 | Opening: Check-in included chakra discussion and impromptu discussion of addictions, endorphins, substance abuse, SAMSKARAS (repetitive patterns of behavior), and impact on the autonomic nervous system Sequence: | 25-30 |

| a. Nadi Shodhana Pranayama - (Alternate Nostril Breathing×10) to cleanse energy channels and regulate breathing[61] | 5-7 | a. Pranayama - Samavrtti Breathing (5 min) | 5 | |

| b. Seven stretches of the spine | 10 | b. Vrksasana (Tree Prep) for introduction to balance. Works to remedy flat feet while strengthening the arches, ankles, calves, and thighs. It also lengthens the spine and improves balance while opening the shoulders, chest, thighs, and hips. Balance poses calm the mind, reduce stress, and increase focus[54,61] | 7-10 | |

| c. Traction in supine with three people for lumbar pain relief. Participant lays on floor with yoga strap looped around waist. First partner crosses strap and places behind their calves and then walks backward until the strap is taut. Participant reaches arms overhead and holds second partner’s ankles. On an exhale, both partners press in opposite directions. Individual stays in pose | 1 | c. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in preferred position | 15-20 | |

| e. Supta Padangusthasana 1 with neck traction to release cervical spine[66] | 10 | |||

| f. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in basic relaxation pose | 20 | |||

| 10 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 2-3 | Opening: Check-In Sequence: | 2-3 |

| a. Easy Seated Pose with V-Pac series×20 | 3 | a. Easy-seated Pose with V-Pac Series×20 | 5 | |

| b. Seven stretches of the spine | 5 | b. Seven stretches of the spine | 5 | |

| c. Plank in knee variation | 3 | c. Plank knees down variation | 2 | |

| d. Cobra | 3 | d. Cobra | 2 | |

| e. Downward Facing Dog | 7 | e. Downward Facing Dog | 2 | |

| f. Half Sun Salutation | 5 | f. Half sun salutation | 5 | |

| g. Virabhadrasana-1 | 5 | g. Parsvottanasana (Pyramid Pose) hands on blocks variation to strengthen the feet, ankles, knees, shins, and thighs. It releases hips while stretching hamstrings and lengthens the spine and improves balance[61] | 10 | |

| h. Virabhadrasana-2 | 5 | h. Virabhadrasana lll Prep (Warrior 3 Prep) with hands-on block variation for stabilization to strengthen feet, ankles, calves, knees, and thighs while stretching the hips and groin. It also improves balance | 5-7 | |

| i. Tree Prep (ChairWall) | 3 | i. Warrior 3 Prep with the foot at wall variation to provides proprioceptive input and stabilization for the back leg[61] | 7 | |

| j. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in preferred position | 15 | j. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in preferred position | 7-10 | |

| 11 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 3-5 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 2-3 |

| a. 3-Part V-Pac Series | 5-7 | a. Seven stretches of the spine | 10 | |

| b. Seven stretches of the spine | 10 | b. Plank knees down variation | 5 | |

| c. Supta Badha Konasana | 20 | c. Cobra | 5 | |

| d. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in legs up incline position | 20 | d. Downward Facing Dog | 5 | |

| e. Half Sun Salutation | 5 | |||

| f. Pyramid Pose | 5-7 | |||

| g. Warrior 3 Prep hands-on block variation | 5-7 | |||

| h. Warrior 3 Prep foot at wall variation | 5-7 | |||

| i. Warrior 3 Pose to strengthen feet, ankles, calves, knees, and thighs and stretch the hips and groin. It also improves balance[61] | 5 | |||

| j. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in preferred position | 10-15 | |||

| 12 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 7-10 | Opening: Check-in Sequence: | 2-3 |

| a. Seven stretches of spine | 10 | a. Seven stretches of the spine | 10 | |

| b. Supta Badha Konasana | 20 | b. Plank knees down variation | 5 | |

| c. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in preferred position with Monkey story meditation | 20 | c. Cobra | 5 | |

| d. Downward Facing Dog | 5 | |||

| e. Half sun salutation | 5 | |||

| f. Salamba Sirsasana l-Headstand Prep with three blocks and feet on floor variation to release pressure cervical vertebra, relax trapezius, stretches hamstrings, and calves with massage-like effect in thoracic spine[67] | 10 | |||

| g. Supta Padanghustasana l with strap around head and foot variation to lengthen and relax the cervical spine and activate PNS[60] | 5 | |||

| h. Seated meditation | 5 | |||

| i. Simple twist before moving into Savasana in preferred position | 7 | |||

| 13 | Opening: Check-in Sequences: | 3-5 | Group discussion about home practice Sequence: | 20-30 |

| a. 3-Part V-Pac Series with Samavritti Pranayama | 5-7 | a. 3-Part V-Pac Series with Samavritti Pranayama | 3 | |

| b. Seven stretches of the spine | 10 | b. Supta Padanghustasana l with strap around head and foot variation to lengthen and relax cervical spine and activate PNS[60] | 10 | |

| c. Individual’s choice of pose | 20 | c. Headstand Prep at wall with 3 blocks inversion | 10 | |

| d. Savasana in preferred position ending with simple twist | 20 | d. Easy Seated Pose meditation focused on breath ending with simple twist | 5-7 | |

PNS=Parasympathetic nervous system, LBP=Low back pain, TFL=Tensor fascia latae, CNS=Central nervous system, ROM=Range of motion

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Sigma Plot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Feasibility of participant recruitment and retention and adherence to intervention and adverse events were assessed by descriptive analysis. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, range, and 95% confidence interval for the mean difference) were calculated. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to detect changes over time with a P = 0.05 significance level with post hoc analysis using Holm–Sidak method for all pair-wise multiple comparisons. If the sample size was not sufficient with the repeated-measures design, secondary analysis on the main interest of pre- and post-intervention changes from preintervention assessment and postintervention assessment was done using paired one-tailed t-tests. If normality failed, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used.

Results

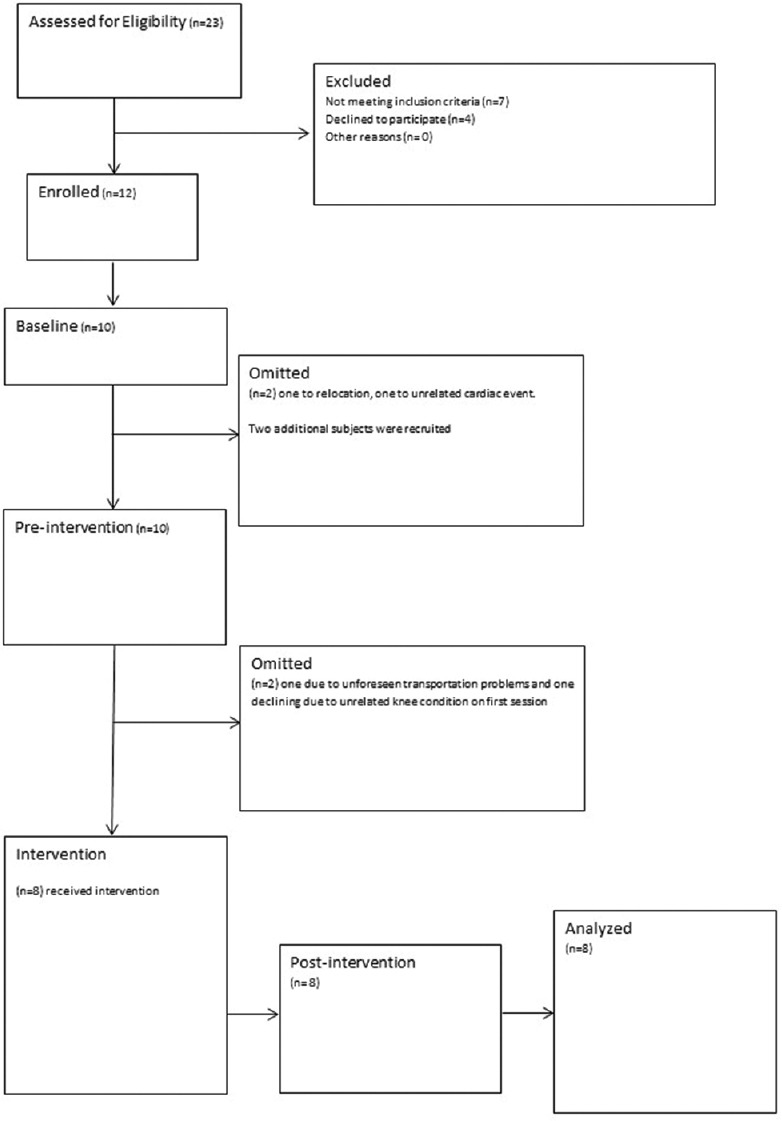

Twelve participants were enrolled within a 3-month period but eight participated in the intervention [Figure 1]. Loss of participants occurred prior to the 1st week of yoga intervention. There were seven females and one male ranging in age of 23–60 with the mean age of 45.63 ± 14.55 years. The overall attendance rate was 79.7%. One participant missed 33.3% of the sessions due to out-of-town work obligations. No adverse events were reported. The cohort completed 12 weeks of yoga with 100% retention rate.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram: Over 3 months, 12 participants were recruited with 8 completing the study

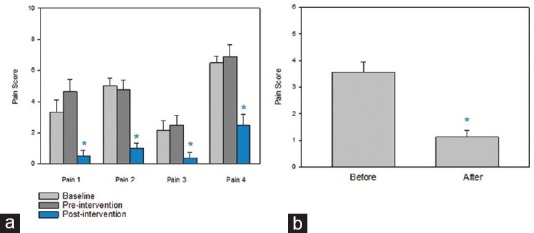

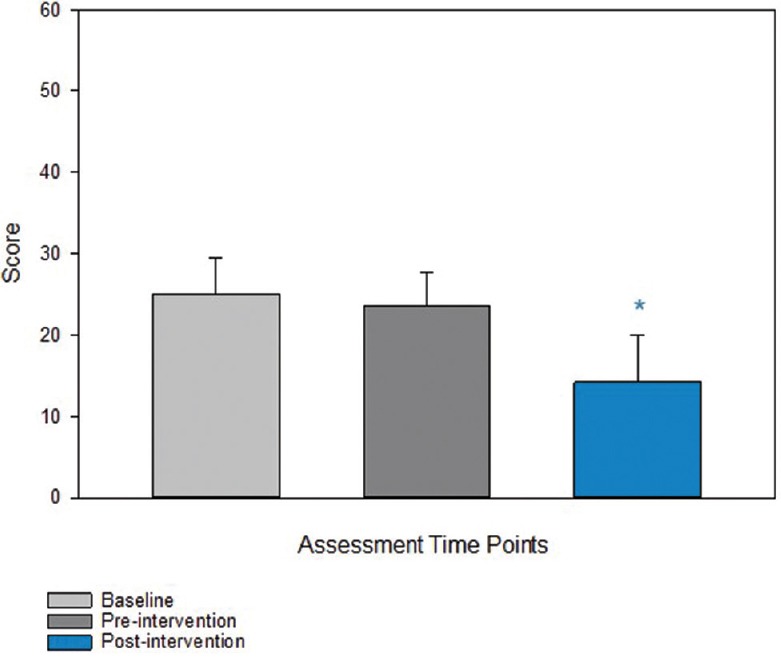

Significant differences were found following the yoga intervention in the primary outcome measures of pain and disability. Intensities of present pain, weekly average, weekly best, and weekly worst all significantly improved [Figure 2a]. Significant improvements in pain scores measured over time (P < 0.001) were recorded before/after most classes [Figure 2b, P ≤ 0.001]. Significant improvement was found in Oswestry Disability Index scores [Figure 3] from pre- to post-yoga (P = 0.028) and over time (P = 0.005).

Figure 2.

Pain Scores. (a) Pain intensity shows significant improvements over time (ANOVA) in all pain at P < 0.001. Pain 1 = present pain, pain 2 = weekly average pain intensity, pain 3 = weekly best pain intensity and pain 4 = weekly worst pain intensity. (b) Present pain intensity on a 1–10 scale measured immediately before and after yoga sessions (n = 20) showed a significant reduction P ≤ 0.001 with a t-test

Figure 3.

Oswestry Disability Scale. Disability scores improved over time P = 0.005 as measured by ANOVA

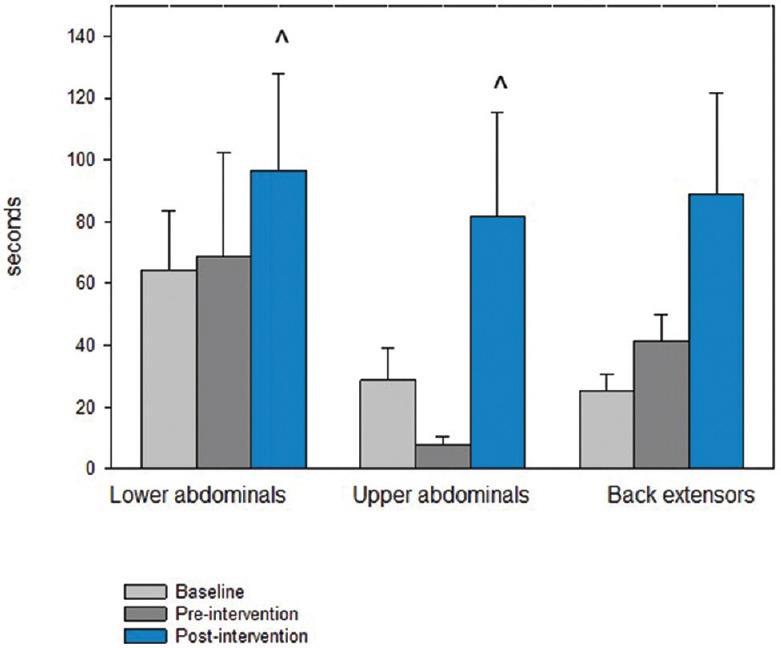

Upper and lower abdominal strength (P = 0.008 and P = 0.031, respectively) [Figure 4] demonstrated significant improvement following the intervention with a positive trend in back extensor strength (P = 0.078). Likewise, spinal and hip flexor flexibility improved significantly following yoga intervention (P = 0.002, P = 0.024 right hip; P = 0.05 left hip, respectively). Hamstring flexibility did not show significant improvements.

Figure 4.

Core Strength Measures. Upper abdominal strength showed the most improvement over time (P = 0.055) with significance in pre-post measures (P = 0.008). Lower abdominal strength showed a trend over time (P = 0.085) with significance in pre-post measures (P = 0.031). The improvements in back extensor strength were not significant but showed a trend in improvement (P = 0.078)

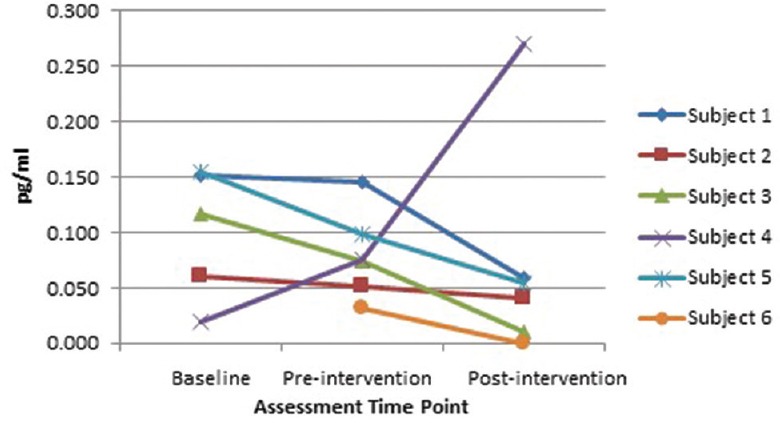

Overall TNF-α protein level changes did not reach a level of significance [Figure 5]. Two of the eight participants had undetectable levels. Five of the remaining six participants had decreased; ranging 28.57%–100%, averaging 76.2%, and the one outlier had a large increase (82.41%).

Figure 5.

Serum TNF-α levels. Two participants who did not have detectable levels are not shown. Five of six participants showed a reduction in TNF-α levels following yoga intervention, while one outlying participant showed a large increase over time including the preintervention assessment

Brain spectroscopy results showed a general trend in NAA upregulation bilaterally in the DLPFC and thalamus [Table 2]. Due to the limited number of participants included (n = 3), traditional statistical analysis was not performed. Of the three participants, one participant had high baseline NAA concentration in the right DLPFC that decreased following yoga intervention. Second, the signal-to-noise ratio was too high to obtain NAA concentration in the left DLPFC in that participant, and the participant had unusually low level of NAA in the left thalamus at baseline. Another participant also had high signal-to-noise ratio in the right thalamus following yoga training.

Table 2.

Brain spectroscopy N-acetylaspartate levels

| NAA subjects | Right DLPFC | Left DLPFC | Right thalamus | Left thalamus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| 1 | 1.218 | 1.328 | 1.199 | 1.38 | 1.119 | 1.291 | 1.397 | 1.491 |

| 2 | 1.207 | 1.265 | 1.281 | 1.379 | 0.82 | 1.228 | 1.666 | |

| 3 | 2.704 | 1.678 | 1.213 | 1.308 | 0.563 | 1.483 | ||

The blank cells are representative of missing data. NAA=N-acetylaspartate, DLPFC=Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, Pre=Preintervention measurement, Post=Postintervention measurement

Discussion

This study investigated the feasibility and potential physical and physiological mechanisms underlying yoga intervention in improving pain and function in a predominantly underserved population suffering with CLBP. While a few studies have looked at spinal flexibility,[30,31,32] this study is unique in assessing core strength in combination with measuring inflammatory markers and brain changes as potential underlying mechanisms contributing the effectiveness of a yoga intervention. No study has used brain spectroscopy or TNF-α to examine the effects of yoga in CLBP. Very few studies have looked at measures of core strength in a yoga program,[33,34] and none are in a CLBP population.

Feasibility

A 12-week group yoga program in an underserved population appears feasible with improvements in pain, disability, spinal flexibility, and core strength and some interesting changes in physiological biomarkers. Previous findings of yoga for the management of CLBP in an underserved minority population show a 44%–65% treatment adherence rate for two versus one sessions, respectively.[25] We report 100% retention rate during the intervention phase and 79.7% treatment adherence of twice-weekly group yoga over 12 weeks of intervention. All participants were recruited in 3 months, and only 4 eligible participants declined to participate. There were no adverse events or side effects from participation in yoga. These findings support the potential use of yoga as a viable treatment option for the underserved population to manage CLBP.

Pain and disability

Yoga improved all measures of pain intensity over time and showed immediate decrease in pain intensity following each yoga session. Participants subjectively reported progressively longer duration of pain relief following yoga sessions. These findings agree with most previous studies where 7 days–12 weeks of yoga decreased pain and pain behavior.[35,36,37,38] Yoga intervention also had greater impact on pain intensity at 6-month follow-up compared to conventional exercise program[39] and was found to be as effective as physical therapy.[36] Since pain is the primary complaint for seeking medical care that may not be accessible or utilized, our results support yoga as an alternative intervention for CLBP for underserved individuals.

By decreasing pain, participants may be more likely to return to work and participate in activities they once avoided. We report an average 40% improvement in disability ratings. Multiple studies show 1–16 weeks of yoga result in significantly lower short-term back-specific disability.[40] Research supports many different styles of yoga, including Hatha, Iyengar, Viniyoga, and unspecified types to decrease functional disability.[41] The fact that many different styles of yoga are included suggests that the principles emphasized in yoga are more important than any specific sequence of postures.

Physical measures

Recent literature suggests that yoga can increase function in those with CLBP through improvements in strength, flexibility, and balance. Improvements in strength, flexibility, and balance after yoga are made because of the emphasis on physical postures, breathing techniques, relaxation, and meditation.[11,31] We found an improvement in spinal and hip flexor flexibility following yoga, suggesting that yoga contributes to better physical function and less disability. Hamstring flexibility was the only ROM measure that did not significantly improve which could be due to the participants having flexibility close to the normal measurements for healthy peers.[42]

One novel aspect of our study is improvement in core muscle strength. Upper abdominal strength showed the largest improvement and a positive trend in back extensor strength was noted. Improvement in core strength could be attributed to improvement in lumbar stabilization, thereby reducing pain. Further studies are needed to investigate the independent effects of yoga on trunk muscles for pain modulation. Interestingly, the tests used for core muscle strength were terminated due to pain at pre-yoga assessment sessions and were terminated due to fatigue at post-yoga session.

Biological mechanisms

Five of six participants with detectable serum TNF-α levels had maintained or decreased levels from baseline to preintervention and a showed further decrease following yoga intervention. TNF-α is a cytokine implicated in many different diseases, but specific pathophysiology is unknown, although people with CLBP due to disc herniation have altered serum cytokine levels, specifically IL-6 and TNF-α.[43] An inflammatory process other than CLBP could have produced the observed outlier. Our findings are in contrast with a recent study showing TNF-α levels maintained in premenopausal middle-aged women with CLBP who performed a 12-week yoga program, whereas the TNF-α levels significantly increased over time in the control group.[44] Our results align with a study of overweight people with chronic inflammatory conditions such as diabetes observing reduced serum TNF-α levels in those who underwent a 2 hours daily yoga for 10 days.[45]

Although a small sample size was eligible for the MR spectroscopy, the preliminary results showed a positive trend in increase in NAA in DLPFC and thalamus. Low NAA in previous studies of people with CLBP has been interpreted as neurodegeneration[19,22,46] or neuronal metabolic dysfunction.[47,48] This study is the first to observe the levels of neurochemicals associated with a yoga intervention, so the upregulation found in the DLPFC and thalamus are notable. Future research involving a larger sample is warranted to determine the significance of outcomes and to determine whether yoga has positive effect on neurodegeneration and immune dysfunction seen in CLBP. Although it is unclear how CLBP and yoga may be influenced by changes in TNF-α and NAA upregulation, the medial prefrontal cortex is thought to coordinate autonomic and behavioral stress responses.[49] Elevated TNF-α levels appear to correlate to high pain scores in thoracic disc herniations,[50] and it is thought that TNF-α is one of the pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in neuropathic pain through a GABAergic mechanism.[51] Immune cells are recruited in response to injury and could induct the sensitization of peripheral nociceptors, thus beginning a complex interactive network of inflammatory mediators, neurotransmitters, immune cells, neurons/support cells that synchronizes immune responses, and pain pathway modulation.[52] The beneficial effects of long-term yoga on stress responses, especially C-reactive protein and serum IL-6 levels,[53] highlights the potential benefits of yoga on the immune system. Future studies of the effect of yoga on the interplay between central nervous system pain regulation and immune responses are certainly warranted.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study was the limited participant number needed for generalizability of the results. The lack of group difference in TNF-α levels and back extension strength could be due to small sample size. The wait list design lacks a true control group and is not conducive to participant blinding. Yoga sessions were performed in groups resulting in no control for socialization. Gender bias may be present because all but one participant completing the study were female. Due to testing facility scheduling, the time of day outcomes was taken were variable between participants. Results found here should be confirmed in a large randomized control study. Despite the limitations, the detection of changes in TNF-α and MR spectroscopy scans illuminate potential explanations for beneficial effects of yoga.

Conclusion

Yoga is effective in reducing pain and disability in those with CLBP and in part works by increasing flexibility and core strength. Brain spectroscopy and TNF-α changes should be further investigated for influence on pain pathways. The use of yoga appears to be a viable supplement to basic medical treatment in low-income patient populations, where many barriers to health care are present. A larger study is feasible and warranted.

Financial support and sponsorship

University of Kansas Medical Center School of Health Professions to Yvonne Colgrove and Neena Sharna and the Frontier's Trail Blazer award to Neena Sharma, as well as the use of the University of Kansas Medical Center Hoglund Brain Imaging Center for taking outcome measures including blood draws and brain images and the Kansas Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center for ELISA analysis.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

An Interprofessional Clinical Research Grant from KUMC School of Health Professionals to Yvonne Colgrove and Neena Sharma and a Frontier's Trail Blazer award to Neena Sharma supported this research. These committees had no role in the study's design, conduct, or reporting. We would like to thank Dr. Joseph Le Master for advice on research design and recruitment efforts, Kelly Colln for providing expert yoga consultation for program design and yoga intervention, Susan Harp fill in yoga instructor, Zaid Mansour for MR spectroscopy acquisition, JoAnn Lierman for blood draws, Michelle Winter for ELISA analysis, and Sevana Haghverdian for assisting with outcome measures.

References

- 1.Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: Socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(Suppl 2):21–4. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJ, Benyamin RM, Hirsch JA. Epidemiology of low back pain in adults. Neuromodulation. 2014;17(Suppl 2):3–10. doi: 10.1111/ner.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karppinen J, Shen FH, Luk KD, Andersson GB, Cheung KM, Samartzis D. Management of degenerative disk disease and chronic low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 2011;42:513–28, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swinkels-Meewisse IE, Roelofs J, Verbeek AL, Oostendorp RA, Vlaeyen JW. Fear of movement/(re) injury, disability and participation in acute low back pain. Pain. 2003;105:371–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vlaeyen JW, Seelen HA, Peters M, de Jong P, Aretz E, Beisiegel E, et al. Fear of movement/(re) injury and muscular reactivity in chronic low back pain patients: An experimental investigation. Pain. 1999;82:297–304. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2013;29:450–60. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31825e1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saper RB, Sherman KJ, Cullum-Dugan D, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Culpepper L. Yoga for chronic low back pain in a predominantly minority population: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Altern Ther Health Med. 2009;15:18–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:849–56. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-12-200512200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox H, Tilbrook H, Aplin J, Semlyen A, Torgerson D, Trewhela A, et al. A randomised controlled trial of yoga for the treatment of chronic low back pain: Results of a pilot study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010;16:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tilbrook HE, Cox H, Hewitt CE, Kang’ombe AR, Chuang LH, Jayakody S, et al. Yoga for chronic low back pain: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:569–78. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Wellman RD, Cook AJ, Hawkes RJ, Delaney K, et al. A randomized trial comparing yoga, stretching, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:2019–26. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma M, Haider T, Knowlden AP. Yoga as an alternative and complementary treatment for cancer: A systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:870–5. doi: 10.1089/acm.2012.0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulkarni DD, Bera TK. Yogic exercises and health – A psycho-neuro immunological approach. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;53:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pullen PR, Nagamia SH, Mehta PK, Thompson WR, Benardot D, Hammoud R, et al. Effects of yoga on inflammation and exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008;14:407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Schiltenwolf M, Buchner M. The role of TNF-alpha in patients with chronic low back pain-a prospective comparative longitudinal study. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:273–8. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816111d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shete SU, Verma A, Kulkarni DD, Bhogal RS. Effect of yoga training on inflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein in employees of small-scale industries. J Educ Health Promot. 2017;6:76. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_65_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Twal WO, Wahlquist AE, Balasubramanian S. Yogic breathing when compared to attention control reduces the levels of pro-inflammatory biomarkers in saliva: A pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:294. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1286-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grachev ID, Fredrickson BE, Apkarian AV. Abnormal brain chemistry in chronic back pain: An in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Pain. 2000;89:7–18. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grachev ID, Ramachandran TS, Thomas PS, Szeverenyi NM, Fredrickson BE. Association between dorsolateral prefrontal N-acetyl aspartate and depression in chronic back pain: An in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2003;110:287–312. doi: 10.1007/s00702-002-0781-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma NK, Brooks WM, Popescu AE, Vandillen L, George SZ, McCarson KE, et al. Neurochemical analysis of primary motor cortex in chronic low back pain. Brain Sci. 2012;2:319–31. doi: 10.3390/brainsci2030319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma NK, McCarson K, Van Dillen L, Lentz A, Khan T, Cirstea CM. Primary somatosensory cortex in chronic low back pain – A H-MRS study. J Pain Res. 2011;4:143–50. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S19297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gussew A, Rzanny R, Güllmar D, Scholle HC, Reichenbach JR. 1H-MR spectroscopic detection of metabolic changes in pain processing brain regions in the presence of non-specific chronic low back pain. Neuroimage. 2011;54:1315–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Apkarian AV, Sosa Y, Sonty S, Levy RM, Harden RN, Parrish TB, et al. Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10410–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2541-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. ISBN-13: 978-0-309-21484-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saper RB, Boah AR, Keosaian J, Cerrada C, Weinberg J, Sherman KJ. Comparing once- versus twice-weekly yoga classes for chronic low back pain in predominantly low income minorities: A randomized dosing trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013. 2013:658030. doi: 10.1155/2013/658030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1331–4. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000164099.92112.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The oswestry disability index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2940–52. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito T, Shirado O, Suzuki H, Takahashi M, Kaneda K, Strax TE. Lumbar trunk muscle endurance testing: An inexpensive alternative to a machine for evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:75–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekedahl KH, Jönsson B, Frobell RB. Validity of the fingertip-to-floor test and straight leg raising test in patients with acute and subacute low back pain: A comparison by sex and radicular pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1243–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tekur P, Singphow C, Nagendra HR, Raghuram N. Effect of short-term intensive yoga program on pain, functional disability and spinal flexibility in chronic low back pain: A randomized control study. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:637–44. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galantino ML, Bzdewka TM, Eissler-Russo JL, Holbrook ML, Mogck EP, Geigle P, et al. The impact of modified Hatha yoga on chronic low back pain: A pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10:56–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams KA, Petronis J, Smith D, Goodrich D, Wu J, Ravi N, et al. Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain. 2005;115:107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith PD, Mross P, Christopher N. Development of a falls reduction yoga program for older adults-A pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2017;31:118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar S, Prasad S, Balakrishnan B, Muthukumaraswamy K, Ganesan M. Effects of Isha Hatha yoga on core stability and standing balance. Adv Mind Body Med. 2016;30:4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein KM, Weinberg J, Sherman KJ, Lemaster CM, Saper R. Participant characteristics associated with symptomatic improvement from yoga for chronic low back pain. J Yoga Phys Ther. 2014;4:151. doi: 10.4172/2157-7595.1000151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saper RB, Lemaster C, Delitto A, Sherman KJ, Herman PM, Sadikova E, et al. Yoga, physical therapy, or education for chronic low back pain: A randomized noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:85–94. doi: 10.7326/M16-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wieland LS, Santesso N. A summary of a cochrane review: Yoga treatment for chronic non-specific low back pain. Eur J Integr Med. 2017;11:39–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tekur P, Nagarathna R, Chametcha S, Hankey A, Nagendra HR. A comprehensive yoga programs improves pain, anxiety and depression in chronic low back pain patients more than exercise: An RCT. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20:107–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nambi GS, Inbasekaran D, Khuman R, Devi S, Shanmugananth, Jagannathan K. Changes in pain intensity and health related quality of life with Iyengar yoga in nonspecific chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled study. Int J Yoga. 2014;7:48–53. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.123481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goode AP, Coeytaux RR, McDuffie J, Duan-Porter W, Sharma P, Mennella H, et al. An evidence map of yoga for low back pain. Complement Ther Med. 2016;25:170–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holtzman S, Beggs RT. Yoga for chronic low back pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18:267–72. doi: 10.1155/2013/105919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Youdas JW, Krause DA, Hollman JH, Harmsen WS, Laskowski E. The influence of gender and age on hamstring muscle length in healthy adults. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:246–52. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2005.35.4.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraychete DC, Sakata RK, Issy AM, Bacellar O, Santos-Jesus R, Carvalho EM. Serum cytokine levels in patients with chronic low back pain due to herniated disc: Analytical cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2010;128:259–62. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802010000500003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho HK, Moon W, Kim J. Effects of yoga on stress and inflammatory factors in patients with chronic low back pain: A non-randomized controlled study. Eur J Integr Med. 2015;7:118–23. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yadav RK, Magan D, Mehta N, Sharma R, Mahapatra SC. Efficacy of a short-term yoga-based lifestyle intervention in reducing stress and inflammation: Preliminary results. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:662–7. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grachev ID, Fredrickson BE, Apkarian AV. Brain chemistry reflects dual states of pain and anxiety in chronic low back pain. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2002;109:1309–34. doi: 10.1007/s00702-002-0722-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fundytus ME. Glutamate receptors and nociception: Implications for the drug treatment of pain. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:29–58. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Neill J, Eberling JL, Schuff N, Jagust W, Reed B, Soto G, et al. Method to correlate 1H MRSI and 18FDG-PET. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43:244–50. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200002)43:2<244::aid-mrm11>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McKlveen JM, Myers B, Herman JP. The medial prefrontal cortex: Coordinator of autonomic, neuroendocrine and behavioural responses to stress. J Neuroendocrinol. 2015;27:446–56. doi: 10.1111/jne.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andrade P, Cornips EM, Sommer C, Daemen MA, Visser-Vandewalle V, Hoogland G. Elevated inflammatory cytokine expression in CSF from patients with symptomatic thoracic disc herniation correlates with increased pain scores. Spine J. 2018;18:2316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu D, Zhao H, Gao H, Zhao H, Liu D, Li J. Participation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in neuropathic pain evoked by chemotherapeutic oxaliplatin via central GABAergic pathway. Mol Pain. 2018;14:1744806918783535. doi: 10.1177/1744806918783535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ren K, Dubner R. Interactions between the immune and nervous systems in pain. Nat Med. 2010;16:1267–76. doi: 10.1038/nm.2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Christian L, Preston H, Houts CR, Malarkey WB, Emery CF, et al. Stress, inflammation, and yoga practice. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:113–21. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cb9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keller D. Vol 2: Applications. Reston, VA: DoYoga Productions; 2010. Yoga as Therapy; 98 pp. 100, 127-131, 149, 158, 188-190, 199-209, 230, 267. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stiles M. Boston, MA: Weiser Books; 2000. Structural Yoga Therapy: Adapting to the Individual; pp. 47–67. 129-131, 198-199, 206-207. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keller D. Reston, VA: Do Yoga Production; 2003. Refining the Breath Pranayama: The Art of the Awakened Breath; pp. 33–45. 57-62, 161. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Azevedo E. Lumbar Stabilization: Controlled Mobility Program. In: Hydration D, editor. Vol 8x12. Kansas City, MO: Modern Physical Therapy; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lasater J. Berkley, CA: Rodmell Press; 2005. Relax and Renew: Restful Yoga for Stressful Times; pp. 5–10. 25-29, 35-38, 75, 83, 187. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carver L. 10 Powerful Mudras and How to Use Them. 2017. [Last accessed on 2019 Jan 21]. Available from: https://chopra.com/articles/10-powerful-mudrasand- how-to-use-them .

- 60.Shifroni E, Sela M. Vol. 84. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace IndependentPublishing Platform; 2016. Props for Yoga. Vol 2: Sitting Asanas and Forward Extensions; pp. 42–5. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kirk M, Boon B, Di’Turo D. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2006. Hatha Yoga Illustrated For Greater Strength, Flexiblity and Focus; p. 17. 26, 30, 54-56, 60-61, 70-71, 100, 140-1. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Long R. Vol. 56. Canada: BandhaYoga Publications; 2008. The Key Poses of Hatha Yoga; pp. 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keller D. Reston, VA: Do Yoga Production; Yoga As Therapy. Vol 1: Foundations; p. 118. 234-235. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lasater J. Boulder, CO: Shambhala; 2017. Restore and Rebalance: Yoga for Deep Relaxation; p. 110. 152. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iyengar B. The Path to Holistic Health. New York: DK Publishing; 2008. pp. 242–43. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shifroni E, Sela M. Vol 1: Standing Asanas. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2015. Props for Yoga: A Guide to Iyengar YogaPractice with Props; p. 42. 84-5. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shifroni E. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2017. Props for Yoga: A Guide to Iyengar Practice with Props Inverted Asanas. Vol 3; pp. 24–6. [Google Scholar]