Abstract

Background:

The rapidly increasing diabetes burden, reaching epidemic proportions despite decades of efforts, reflects our failure to translate the proven evidence for prevention of diabetes. Yoga, with its holistic approach, alters the habituated patterns of lifestyles and behaviour. Motivated by the accumulating evidence, the Government of India funded a large randomized controlled trial.

Aims and Objectives:

The twin objectives were: (a) estimate the prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes through a parallel multisite stratified cluster sampling method and (b) implement NMB 2017 (niyantrita madhumeha bharata abhiyaan), a randomized control trial using yoga based lifestyle program.

Materials and Methods:

Screening for Indian Diabetes Risk score(IDRS) was conducted in randomly selected clusters in all 7 zones (65 districts from 29 states/union territories) of India. This was followed by detailed assessments in those with known diabetes and high risk (≥60) on IDRS. Those who satisfied the selection criteria and consented were recruited for the two armed waitlisted randomized control trial. A validated remedial diabetesspecific integrated yoga lifestyle module was taught to the experimental arm by certified volunteers of Indian Yoga Association. Followup assessments were done after 3 months in both groups. In this article, we report the methodology of the trial.

Results:

Response to door to door visits (n-240,968 adults >20yrs) in randomly selected urban and rural households for screening was 162,330; detailed assessments (A1c, lipid profile, BMI, stress, tobacco etc) were performed on 50,199 individuals. Of these 12466 (6531 yoga 5935 control) consented and for the RCT; 52% females, 48% males; 38% rural, 62% urban; BMI 21.1 ± 3.8; waist circumference 91.7 ± 11.9. A1c in diabetes subjects in yoga group was 7.63 ± 2.17 and 7.86 ± 2.13 in control group.

Conclusion:

This unique methodology provides the evidence to implement a validated yoga life style module using yoga volunteers in all parts of the country which is an urgent need to prevent India from becoming the global capital for diabetes.

Keywords: Diabetes, India, methodology, traditional yoga lifestyle

Introduction

T2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a growing noncommunicable disease with major complications, poses great challenges for health-care industry across the globe, especially in the current millennium. The management of diabetes and its complications enforces a huge economic burden on nations and their health-care systems.[1] Many of the recent studies suggest that increasing prevalence will make India the world leader in diabetes by 2025.[2]

Recent epidemiological studies have shown that lifestyle interventions are cost-effective in the prevention and management of T2DM. A systematic review of 53 studies brought to the fore that lifestyle interventions that include dietary modification and exercise reduce the incidence of T2DM.[3] China's Da Qing T2DM prevention study showed that dietary modification and regular physical activity reduce diabetes incidence by 51% in a 6-year period and 43% when followed up over 20 years.[4] The Diabetes Community Lifestyle Improvement Program (D-CLIP) demonstrated a 32% relative risk reduction in prediabetes.[5] The lifestyle modification program has effected in good reduction of incidence rate of diabetes in nondiabetic high-risk (body mass index [BMI] >34) people.[6]

Yoga, when considered as a lifestyle intervention, presents a comprehensive and integrated solution to the T2DM problem by adopting an inclusive approach: integrating cleansing techniques, yogic postures (asanas), breathing practices (pranayama) and meditation, emotion culture, and a fiber-rich vegetarian diet. It comprises both the exercise required and stress reduction as a major component.[7,8] Findings on studies on yoga for T2DM offer evidence for multiple benefits, such as improved glycemic control, improvements in lipid profile, weight, cognition, nerve conduction velocity,[9] insulin sensitivity, and cardiovascular autonomic functions.[10] Select interventional studies on lifestyle and yoga are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Publication on studies on lifestyle and yoga in diabetes

| Sl.no | Author Ref | Title | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lifestyle intervention | ||

| A | Howells L et al. (2016) | Clinical impact of lifestyle interventions for the prevention of diabetes: An overview of systematic reviews | Concluded that relatively long-duration lifestyle interventions can limit or delay progression to diabetes when compared to time-limited interventions |

| B | Li G, Zhang P et al. (2008) | The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: A 20-year follow-up study | Compared with control, participants in combined lifestyle intervention group had 51% lower incidence of diabetes during the active intervention period and 43% lower incidence (0.57; 0.41-0.81) over the 20-year period |

| 2 | Integrated yoga therapy | ||

| A | Monro R et al. (1992) | Yoga therapy for NIDDM: A controlled trial | FBG and HbAlc improved significantly better (P<0.05) in yoga than control group |

| B | Kumar V et al. (2016) | Role of yoga for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis | Yoga as an add-on intervention in comparison to standard treatment; FBS - mean difference - 1.40, P<0.0001; PPBG – 0.91, P<0.0001 HbA1c – 0.64, P<0.0002 |

| C | Nagaraj C et al. (2013) | Effect of integrated yoga therapy on nerve conduction velocity in type-2 diabetics: A cross-sectional clinical study | Significantly higher means of nerve conduction velocity in the right (P=0.004) and left wrists (P=0.017) in yoga group. Significant difference between groups in the right hand (P=0.004) |

| D | Chaya MS et al. (2008) | Insulin sensitivity and cardiac autonomic function in young male practitioners of yoga | Glucose clamp study in normal healthy yoga practitioners; fasting plasma insulin was significantly lower in the yoga than matched control volunteers. Insulin sensitivity was better (P<0.001) in yoga than controls (yoga 7.82 [2.29]; control 4.86 [11.97] (mg/kg min)/(μU/ml). Negative correlation of body weight and waist circumference with glucose disposal rate in the controls; no correlation in the yoga group |

| E | McDermott KA et al. (2014) | A yoga intervention for type 2 diabetes risk reduction: A pilot randomized controlled trial | Yoga participants had significantly greater reductions in weight, waist circumference and BMI versus control (weight - 0.8±2.1 vs. 1.4±3.6, P=0.02; waist circumference - 4.2±4.8 vs. 0.7±4.2, P<0.01; BMI - 0.2±0.8 vs. 0.6±1.6, P=0.05) |

| 3 | Yoga and exercise | - | |

| A | Ross A, et al. (2010) | The health benefits of yoga and exercise: A review of comparison studies | Studies comparing the effects of yoga and exercise seen in healthy and diseased populations, show that yoga may be as effective as or better than exercise in improving a variety of health-related measures |

| B | Govindaraj R et al. (2016) | Yoga and physical exercise-a review and comparison | Compared the studies on effects of yoga and physical exercises. Yoga interventions appear to be equal and/or superior to exercise in most outcome measures. Emphasis on breath regulation, mindfulness during practice, and importance given to maintenance of postures differentiates yoga from physical exercises |

BMI=Body mass index, HbA1c=Hemoglobin A1c, FBG=Fasting blood glucose, PPBG=Postprandial blood glucose

Comparing exercise and yoga suggests that yoga is usually superior to physical exercise in health-related outcome measures such as blood glucose, blood lipids, and oxidative stress, with additional benefits such as improved insulin sensitivity, and subjective measures such as less fatigue, better sleep and quality of life, and reduced medication requirement.[11,12] A few small studies of integrated yoga for prediabetes suggest reduction of risk of developing diabetes.[13,14]

Further, our published controlled studies both in India and the UK between 1992 and 2014[9,11] pointed to the beneficial effect of the integrated yoga module. Based on this decade-long evidence, we undertook a feasibility study and implemented a community program all over India. This was on the occasion of the 2nd International Day of Yoga (June 21, 2015) and was funded by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Planned as “yoga for diabetes week” between June 21 and 27, 2015 and envisaged as 1-year follow-up activity, across 22 states and union territories of the country, 2099 week-long camps (131 in central, 63 in east, 3 in northeast, 16 in northwest, 366 in west, 386 in north, and 1134 in south zones) were held; Indian Diabetes Risk Score (IDRS) and self-reported diabetes status were documented on 104,974 individuals; 56,352 participants with diabetes were taught the yoga module in camps by trained yoga volunteers from many nongovernmental organizations (mainly Arogyabharati) by using CDs and booklets, and blood tests (fasting blood glucose [FBG], postprandial blood glucose [PPBG], and lipid profile) were done on 23,260 participants. One-day follow-up review camp was conducted at the 4th, 7th, and 12th months. Results (report submitted to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, September 2016, and is available on request) showed statistically significant (P < 0.01) reduction in mean FBG from 135.6 ± 63.1 to 111.3 ± 57.4 (18%), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) from 7.14 ± 2 to 6.6 ± 1.7, and triglycerides from 166.9 ± 113.1 to 149.11 ± 76. Interestingly, despite the huge numbers involved at different stages of the activity, there were no adverse effects which were reported.

The present study was conceptualized as a multilevel cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) to document the efficacy of a yoga-based lifestyle module, through a structured program at the community level. As a part of the trial, we also estimated the prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes in Phase 1 of the study. An earlier article published in this journal describes the methodology adopted for the rapid nationwide screening (phase 1) to arrive at prevalence estimates. Here, we report the methodology of the trial (phase 2) which assessed the efficacy of the structured intervention, to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes including developing the validated standardized module of traditional yoga lifestyle.

Methodology

Sample size calculation

The sample size was estimated based on the relative risk reduction in an earlier study, the D-CLIP, a randomized controlled translational trial of 578 overweight/obese Asian Indian adults and other references.[5,15,16] In brief, the annual incidence rate of diabetes was 11.1% in controls and 7.8% in intervention participants, and this provided a conversion rate at 3-month follow-up to be 3% in the control condition and 2% in intervention condition. Based on this, the required sample size for a two-group design, with α = 0.05 and 1 – β = 0.80, was estimated (http://www.sample-size.net) to be 5320 in each group (total 10,640 for two groups). Details of the sample size are presented in part 1 of this study in this journal.

Study design

In phase one of the study, a nationwide sampling strategy was adopted to identify the at-risk population which also provided an estimation of the prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes. This is already described in the previous article on methodology prevalence (part 1), and results of the prevalence are published separately. Phase two was to assess the efficacy of the structured intervention, to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes (refer IJOY Part 1 methodology).

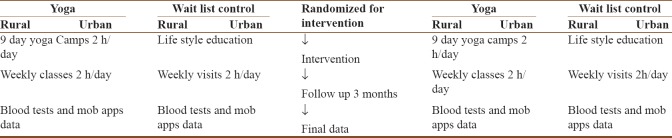

In brief, a four-stage (zone – state – district – urban/rural) strategy was adopted for identifying study locations, which used random cluster sampling method and located households and individuals. Census enumeration blocks (CEBs) were randomly selected, and all eligible individuals (both genders between 20 and 70 years) within the CEBs were contacted. Within the CEB, it was a two-step strategy. In step 1, the door-to-door survey enlisted eligible individuals and specifically inquired the status of diabetes and scored them on the IDRS. In step 2, those reporting diabetes and those scoring high on the IDRS were invited for a detailed baseline assessment which included measuring HbA1c and other investigations. The trial chart is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Phase 2 of NMB - study protocol

Randomization and blinding

Cluster randomization was adopted and not individual-level random allocation.

Two of the four villages and one or two out of two or four CEBs (depending on the population size of the CEB), in the selected ward, were randomly identified as the experimental group and the other was the waitlisted control.

Being an interventional community-based cluster randomized trial, the study participants, staff, and investigators were not blinded to group allocation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adults of both genders in the identified village/CEB, capable of doing yoga and consenting to participate, were recruited and included:

Self-reporting diabetes individuals – cross verified by prescription and/or medication use

Newly diagnosed diabetes (with HbA1c >6.5%)

Prediabetes (HbA1c levels between 5.3 and 6.49%)

High score (>60) on IDRS, with or without hypertension and/or obesity.

Those with severe obesity (BMI >40), history of uncontrolled hypertension, coronary artery disease, renal disease, diabetes retinopathy, previous head injury, tuberculosis, reported psychiatric problems (minor and major), history of major surgery in the past, pregnant women, and those planning to move out of the area within the next 3 months were excluded from the study.

Quality assurance

Quality control was implemented in all aspects of the trial: (a) development and standardization of common yoga protocol; (b) selection and training of research personnel (research associates [RAs] and senior research fellows [SRFs]) for documentation, monitoring, and training as trainers; (c) orientation of field-level certified yoga volunteers for uniformity in teaching the yoga module; and (d) follow-up.

Development of common yoga protocol for T2 diabetes mellitus

The common yoga protocol was considered the crux of the entire trial, and substantive efforts were spent to develop, refine, and finalize the protocol. This effort was led by a team of 16 experts [Table 2] including senior yoga masters from different yoga traditions (member institutions of Indian Yoga Association [IYA]), as well as experienced yoga researchers and diabetologists. Sixteen experts considered sufficient for Delphi[17] consultation undertook a series of brainstorming sessions to refine the yoga modules specific for the present study. The draft of the module had been validated[18] earlier and also during the nationwide week-long Madhumeha Mukta Bharat of International Day of Yoga 2015. This protocol was presented to the group, and written comments by all experts were compiled, discussed, and deliberated. The discussion was focused on how to avoid adverse effects in the target population (prediabetic and diabetic individuals with no complications) taking critical inputs from the diabetic experts as they watched a yoga teacher's demo of all the practices included in the module. The module was finalized after two Delphi rounds and two rounds of focus group discussion.

Table 2.

Experts of yoga protocol committee

| Sl.no. | Affiliation | Role in expert committee |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chancellor | Vice president - IYA Chairman of yoga protocol committee |

| S-VYASA Yoga University | ||

| Bengaluru | ||

| 2 | Assistant professor | Researcher on yoga for diabetes |

| Department of Endocrinology and Metabolic Disorder | ||

| AIIMS, New Delhi | ||

| 3 | Senior scientist and project manager | Researcher on yoga for diabetes |

| MDRF, Chennai | ||

| 4 | Medical director | Researcher on yoga for lifestyle diseases |

| VYASA, Bengaluru | ||

| 5 | CEO. Kaivalyadhama Yoga Institute, Mumbai | Yoga expert, IYA |

| 6 | Director | Yoga expert, IYA |

| Central Council for Research in Yoga and Naturopathy | ||

| Government of India, New Delhi | ||

| 7 | Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram, Chennai | Yoga expert, IYA |

| 8 | Advisor, AYUSH, New Delhi, Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute, Pune, Maharashtra | Yoga expert, IYA |

| 9 | Experienced Iyengar yoga teacher | Yoga expert, IYA |

| Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute, Pune, Maharashtra | ||

| 10 | Director, Morarji Desai National Institute of Yoga, New Delhi | Yoga expert, IYA |

| 11 | Director of CYTER, Puducherry | Yoga expert, IYA |

| Chairman, Research Wing of IYA | ||

| 12 | Mokshayatan International Yogashram, Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh | Yoga expert |

| 13 | International Sri Sri Yoga teacher with The Art of Living | Yoga expert secretary general of IYA |

| Bengaluru | ||

| 14 | Faculty | Researcher on yoga for stress management |

| S-VYASA University, Bengaluru | ||

| 15 | Director (Academic) | Yoga expert |

| Directorate of Vision of World | ||

| Simplified KundaliniYoga | ||

| The World Community Service Centre | ||

| Aliyar, Tamil Nadu | ||

| 16 | Senior scientific officer | Researcher yoga for medical applications |

| Department of Psychiatry, Integrated Centre for Yoga | ||

| National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru |

IYA=Indian Yoga Association

The specific yoga-based lifestyle yoga protocol [Table 3] consisted of practices for primary and secondary prevention of diabetes. These were selected from a large list of practices for lifestyle diseases, available in the tradition. The integrated module included yogic diet, physical practices (sun salutation and asanas), breathing (pranayama) and relaxation techniques, evidence-based meditation,[18,19] and group lectures/individual discussion on yoga concepts of stress management.

Table 3.

Common yoga protocol for type 2 diabetes mellitus (to be practiced 7 days/week)

| Serial number | Name of the practice | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Starting prayer: Asatoma Sat Gamaya | 2 min |

| 2 | Preparatory SukshmaVyayamas and Shithilikarana Practices | 6 min |

| 1. Urdhva-hasta Shvasana (hand stretch breathing 3 rounds at 90°, 135°, 180° each) | ||

| 2. Kati-Shakti Vikasaka (3 rounds each) | ||

| a. Forward and backward bending | ||

| b. Twisting | ||

| 3. Sarvanga Pushti (3 rounds clockwise, 3 rounds counterclockwise) | ||

| 3 | Surya Namaskara –sun salutation(SN) | 9 min |

| a. 10 step fast SN 6 rounds | ||

| b. 12 step slow SN 1 round (to be avoided by those with knee pain, cardiac problems, renal problem, low back pain, retinopathy and the elderly who are weak and not flexible; instead they can do Chair SN) modified version Chair SN: 7 rounds | ||

| 4 | Asanas (1 min per asana) | 15 min |

| Standing (1 min per asana) | ||

| Trikonasana, Pravritta Trikonasana, Prasarita pada-hastasana | ||

| 2. Supine | ||

| Jathara Parivartanasana, Pavanamuktasana, Viparitakarani | ||

| 3. Prone | ||

| Bhujangasana, Dhanurasana followed by Pavanmuktasana 4. Sitting | ||

| Mandukasana, Vakrasana/Ardhamatsyendrasana, Paschimatanasana, ArdhaUshtrasana | ||

| At the end, relaxation with abdominal breathing in supine position (vishranti), 10-15 rounds (2 min) | ||

| 5 | Kriyas | 3 min |

| a. Agnisara: 1 min | ||

| b. Kapalabhati (at 60 breaths per minute for 1 min followed by rest for 1 min) | ||

| 6 | Pranayama | 9 min |

| a. Nadishuddhi (for 6 min, with antarkumbhaka and jalandharbandha for 2 s) b. Bhramari (3 min) | ||

| 7 | Meditation (for stress management for deep relaxation and silencing the mind) cyclic meditation (those who are willing to practice techniques of relaxation evolved by their own institutes may do so) | 15 min |

| 8 | Resolve (I am completely healthy) | 1 min |

| 9 | Closing prayer: Sarvebhavantu Sukhinah | 1 min |

| Total | 60 min | |

SN=Surya Namaskara

The final yoga lifestyle protocol [Table 3] was developed as DVDs and booklets in different languages by the Central Council for Research in Yoga and Naturopathy (CCRYN), and was released on October 2, 2016.[18,20] This new module was consistent to the American Diabetes Association recommendations for lifestyle change for the prevention of diabetes [Table 4].[19,20,21,22,23,24]

Table 4.

Yoga lifestyle compared to American Diabetes Association recommendation of lifestyle programs

| ADA recommendation | Yoga lifestyle | |

|---|---|---|

| Diet | Plant source diet | Satvic diet |

| Rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts | Wholesome lacto-vegetarian diet | |

| Low in refined grains, red or processed meats | Makes mind calm and serene | |

| Mastery over agitated and stressed (rajas) mind, or dull and violent (tamas) mind | ||

| Nil - sugar-sweetened beverages | ||

| Physical activity | At least 2.5 h of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity per week (i.e., brisk walking, water aerobics, swimming, or jogging) | Daily 6 min - Loosening practices |

| Daily 9 min - SN | ||

| 15 min/day×7 days=1.75 h/week | ||

| Two to three sessions of resistance exercise per week (lifting five pound weights or doing pushups) 15×2 = 30 min/week | ||

| Incorporate flexibility exercises, such as stretching or yoga into your weekly routine 45 min/week | Asanas and | |

| Kriyas - 18 min×7 days=126 min=2.1 h/week | ||

| Total=3.75 h/week | 3.85 h/week | |

| Stress management | Diaphragmatic breathing | Pranayama - 9 min |

| Progressive muscular relaxation (40-50 min) | Cyclic meditation 15-25 min | |

| Mindfulness all day | Action in relaxation | |

| Karma yoga | ||

| Abstinence from tobacco | Cognitive behavior therapy | Happiness analysis |

| Jnana yoga | ||

| Abstinence from alcohol | Alcohol anonyms | Faith and surrender yoga |

| Bhakti yoga |

ADA=American Diabetes Association, SN=Surya Namaskara

Training of researchers

Training of senior research fellows

One-day zonal training programs were organized in five zones of India (Delhi, Bhopal, Bengaluru, Salem in Tamil Nadu, and Mumbai) to re-orient them as trainers of instructors and educate them in precise implementation of the trial.

Training of yoga volunteers for diabetes movement

The SRFs with the help of zonal coordinators organized 5 days’ intensive training for Yoga Volunteers for Diabetes Movement (YVDMs) who were certified yoga instructors of the member institutions of IYA with yoga teaching experience of more than 1 year. The 5-day residential camp [Table 5] covered all project-related topics including orientation to teach common yoga protocol and communication skills. They were trained to individualize the protocol based on participant's capacity such as age, gender, and flexibility to start with simple physical movements and slowly go on systematically over the 9 days as per the daily schedule to ensure that the participant had learned all the practices recommended in the protocol with the right understanding of the position and breathing pattern to go with each movement. Overall, a total of 32 camps were organized in different zones of India. The RA or principal investigator (PI) had prepared his/her schedule of visits to these camps to be present on the last day of the training conducted by the SRF. During these visits, the YVDMs were certified after they passed all three examinations namely the practical, theory, and oral.

Table 5.

Schedule of 5-day training camps of Yoga-Certified Volunteers for Diabetes Movement in different zones

| Time | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-7.30 am | Arrival to training center | Yoga | Yoga practical class | Yoga practical class | Yoga practical examination |

| Practical class | |||||

| 7.30-9 am | Bath and break fast | Bath and break fast | Bath and break fast | Bath and break fast | |

| 9-10 am | Introduction to diabetes, medical perspectives and panchakosha level of yogic management of diabetes | Pranayama theory and practice and practical | Training for mobile apps | Examination on use mobile apps | |

| 10-11 am | Stress and diabetes concept and techniques of stress management through yoga | Training for mobile apps use | Individual and group Practical examination | Examination on the use of mobile apps | |

| 11.15-12 am | Inauguration of program | Yoga and modern concepts of diet for diabetes | Training to use mobile apps | Practical examination | |

| 12-1 pm | Introduction to project | Practical chair yoga practice - 1 | Chair Yoga Practice 2 | Practical yoga asana examination | Valedictory program |

| 1-2 pm | Lunch | Lunch | Lunch | Lunch | Lunch |

| 2-3 pm | Details of project and duties of YVDM | Theory and practice of cyclic mediation | Organization and conducting yoga camps for diabetes | Pranayama examination | Departure |

| 3-4 pm | Introduction to cyclic meditation | Data documentation Screening form | Data documentation registration from | Cm examination | |

| 4-5.30 pm | Yoga practical and CM | Screening form data taking | Data documentation registration form | ||

| 6-7.30 pm | Theory and practical emotion culture and jnana yoga | Theory and practical emotion culture | Theory and practical jnana, karma and devotion culture yoga for yogic stress management | Theory and practical jnana, karma, and devotion yoga for yogic stress management | |

| 7.30 pm | Dinner | Dinner | Dinner | Dinner | |

| 8.30-9.30 pm | Interaction | FAQs on DM | Q and A | Q and A |

YVDM=Yoga-Certified Volunteers for Diabetes Movement, DM=Diabetes mellitus, FAQs=Frequently asked questions, CM=Cyclic meditation

During the camps, resources to conduct the intervention were provided to the YVDMs. These included ID cards and required study materials (a copy of the PowerPoint presentation, a pack of 2 DVDs, booklets on yoga for diabetes with common yoga protocol, hard copies of the forms to be filled up for the study, log book, banner templates, hand bills for conducting the camps, etc.) [Table 5].

Intervention

Yoga group: The intervention group [Table 3] received the specially prepared standardized yoga-based lifestyle change protocol along with standard diabetes management education for 3 months. Initially, yoga intervention was taught by the YVDMs as a 9-day camp (2 h daily) activity. This was followed by daily (individual or group) practice using DVDs and included 2-h weekly YVDM-supervised follow-up classes.

In case of individuals with known diabetes, the prescribed antidiabetes medication dosage was noted. If the blood glucose was very high (FBG >200 mg/dl and PPBG >300 mg/dl), the local doctor made suitable changes in medication; if it was under moderate or good control, they were asked to continue the same medication; and if the blood glucose dropped below the normal values, the local doctor reduced the dosages with follow-up monitoring.

For the newly diagnosed cases of diabetes, consultation with the local doctors was arranged who decided the management strategy, i.e., attending yoga lifestyle camps with or without oral hypoglycemic medication depending on the blood glucose levels.

For those who were in prediabetes range, the SRF had a meeting to emphasize the role of adherence to yoga lifestyle to prevent diabetes.

Attendance was maintained in each class and was checked by SRFs. House visits or phone calls were done to remind those who missed one or more classes. Daily attendance was maintained by the YVDM during the core session of 9 days. Duration and regularity of the self-reported yoga practice session using booklet or videos after the camp was documented based on the following questions: (a) “how many days per week did you do the yoga module” and (b) “on an average, how long did each yoga session last” (possible values: 0–15, 16–30, 31–45, 46–60, or >60 min). Dietary intake was monitored using a detailed food frequency questionnaire. Any other health problems encountered during the week were also documented during the weekly study visit.

Intervention adherence

Intervention adherence was assessed by evaluating (a) class attendance and (b) regularity of practice of yoga during the period of study. Participants attended an average of 5 (standard deviation 3.9) out of 9 initial daily core intervention classes. Class attendance did not vary by sex; however, significantly fewer young participants (≤35 years) attended (48%) the study classes compared with of those aged 36–60 years (62%) or those aged 60 or older (75%).

There were no major adverse events or mortality during these 3 months of follow-up. There were a few cases of minor events such as spinal pain, knee pain, generalized body pains, or minor digestive disturbances. These were handled by offering corrective postures and relaxation techniques by consultation on WhatsApp with senior medical yoga professionals such as RA and PI, and/or by medication advice by the local family doctors. For example, there were 27 cases of mild lumbar pain – 2 in Jammu and Kashmir, 4 in west zone, and 11 in south and east zones. For this, they were asked to cut down all forward-bending postures which were replaced by quick relaxation technique and pavanamuktasana lumbar stretch two times a day. Overall, knee pain was observed in five cases in central, three in north, and four in west zones. Digestive problems such as excessive belching or flatulence, constipation, or increased bowel frequency were reported in 12 cases in all zones which were corrected by remedial postures.

The data were kept confidential by the data safety monitoring person in the IT team who would open the access to only the PI and RAs who reviewed them on a daily basis during pre-post data acquisition.

Control group – The waitlist control group received standard diabetes management education. The YVDM who was allotted for monitoring the control group visited the places once a week for an interactive session of 1 h on Sundays to educate them about their lifestyle including diet, physical activity, and tobacco cessation as per the standard lifestyle education protocol. The YVDMs were in close touch with the participants through a WhatsApp group.

The YVDMs were in touch with local doctors of the participants of both yoga and waitlist control groups to get medical supervision during the camps for any medical emergencies and also as chief guests for the inauguration and valedictory programs in the camps.

Yoga camps

The SRF and local YVDMs had already visited the selected places during phase one of the study to motivate the local leaders and philanthropic personnel of the site to organize 9-day yoga camps [Table 6].

Table 6.

Daily schedule of training of participants in 9-day camps in 181 camps in all zones of India

| SL NO | Practices | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4-9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Starting prayer | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Loosening exercises (normal, chair) | Urdhva Hastasana | Urdhva Hastasana | Urdhva Hastasana | Urdhva Hastasana |

| KathiShakthi Vikasana | KathiShakthi Vikasana | KathiShakthi Vikasana | |||

| KathiShakthi Vikasna | |||||

| Sarvangapusti | Sarvangapusti | Sarvangapusti | |||

| 3 | SN (normal, chair) | 10 step (4R’s) | 10 step (6R’s) | 10 step (6R’s) | |

| 12 step (1R) | 12 step (4R’s) | 12 step (6R’s) | |||

| 4 | Asana (normal and/or chair) | Standing | Standing | Standing | Standing |

| Supine | Supine | Supine | Supine | ||

| Prone | Prone | Prone | |||

| Sitting | Sitting | ||||

| 5 | QRT | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Kriya | Kapalabhati | Agnisara | Agnisara | Agnisara |

| Kapalabhati | Kapalabhati | ||||

| Kapalabhati | |||||

| 7 | Pranayama | Nadishuddhi | Nadishuddhi | Nadishuddhi | Nadishuddhi |

| Bhramari | Bhramari | Bhramari | |||

| 8 | Meditation | Cyclic meditation (half) | Cyclic meditation (full) | Cyclic meditation | Cyclic meditation |

| 9 | Resolve | Not needed | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Closing prayer | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | Lecture DVD and interactive Q and A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

SN=Surya Namaskara, QRT=Quick relaxation technique, DVD=Digital video disc

In the districts selected for yoga intervention, each SRF (in charge of two districts) planned and conducted yoga camps (one camp in one or two villages in rural area and one camp for one or two CEBs in urban localities). The dates for the camp were planned to suit the local needs and to ensure availability of the SRF during all camps. The camps lasting for about 2 h every day were held in community or temple halls suitable for 15–30 persons to practice yoga. The 2-h sessions were held multiple times every day: for example, 6–8 am and 7–9 pm for working class of people and 10–30 am to 12–30 pm for homemakers and retired persons. The participants could register for any one of these sessions.

All camp sites were provided with projection facilities in the halls. These sites had a consultation room for the therapist and/or the visiting doctor (when available) for documentation and personal discussions with the participants related to their lifestyle and stress. The YVDMs were in touch with local doctors of the participants for their medical support during the camps, handle any untoward adverse effects, and get advice on any change in medication and long-term monitoring.

Attendance was maintained in each class and was checked by SRFs. House visits or phone calls were done to remind those who missed a class. Visits were made by zonal coordinator to the camps for random checking of the accuracy of the implementation of the trial protocol including the teaching methods, duration and timings of yoga classes, punctuality, and documentation of attendance. The RA based in the central office in Bengaluru was available on WhatsApp video call all 24 h for solving problems and give feedbacks. The common problems faced included arranging the halls, projectors, and speakers; toilet facilities in villages and CEBs; postal delay in the handout material reaching the venues during the planning phase; replacements for YVDMs during the camps if they had some personal or health problems; and queries by participants related to yoga for other health problems. The RAs, PI, and zonal coordinators made personal visits (a total of about 74) to one or more of these places during the planning and implementation phases. Photographs and videos were sent on a daily basis by the YVDMs to SRFs and hence made the quality assurance robust.

Assessments

All assessments done in phase 1 of the trial, available on mobile apps, were used as preintervention dataset, and the same measures were documented after 3 months on the recruited individuals of both yoga and control groups; measures related to yoga awareness and benefits and barriers to yoga practice were documented post assessment in the yoga group. The primary outcome was to look at the conversion from prediabetes to diabetes and normal zones on HbA1c after yoga lifestyle intervention. The secondary outcomes included effect of yoga on diabetes status, lipid profile, and stress measures apart from documenting the knowledge, awareness, and perception about the barriers and benefits of yoga in the population. The summary of the assessments is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Assessments phase 2

| Assessment variable | Method | Instrument used | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | In kg | Digital weighing scale | KRUPS co. 2016 |

| Pre and post | |||

| Retd. design no. 161856 | |||

| Waist circumference | In cm | Measuring tape | |

| Pre and post | |||

| Blood pressure | MmHg | Digital sphygmomanometer | Omron co. 2016 Model HEM7120 |

| Questionnaires | Details in app | SES | Int J Recent Trends Sci Technol 2014;11:1-2. |

| Kuppuswamy’s SES scale revised for 2014 | |||

| Income and expenditure | |||

| Gururaj and Maheshwaran, 2014 | |||

| Monthly for, individual and family | |||

| Sleep | Quantity, quality, and sleep routine Pre-post | Prepared for the purpose by our team | |

| Quality of life | PHQ | ||

| Stress | PSS | ||

| 6 NAS for work, family, health, others, social, financial related stresses | NAS | ||

| Physical activity | Typical daily work/home activity level, frequency and amount of mild, moderate, and vigorous activities | ||

| Substance abuse | Alcohol - quantity, frequency and duration, tobacco - smokeless and smoked | ||

| Yoga related | Yoga awareness | (Nayak et al. 2014) Modified for the present Indian study[24] | |

| Yoga benefit scale | (Nayak et al. 2014) Modified for the present Indian study[24] | ||

| Yoga barrier scale | (Nayak et al. 2014) Modified for the present Indian study[24] | ||

| Blood tests | FBG>8 h after last meal | Glucose oxidase-peroxidase method | “Mindray” autoanalyzer Model no. BS - 390 |

| PPBG 2 h after breakfast | Glucose oxidase-peroxidase method | “Mindray” autoanalyzer Model no. BS - 390 | |

| HbA1c Fasting sample | High-pressure liquid chromatography using the Variant™ II Turbo machine (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) | National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program | |

| Total cholesterol | Cholesterol esterase oxidase- peroxidase-amidopyrine | Auto-analyzer model 2700/480 | Beckman Coulter® |

| Triglycerides | Glycerol phosphate oxidase- peroxidase-amidopyrine | Auto-analyzer- model 2700/480 | Beckman Coulter |

| Low-density lipoprotein | Serum | Auto-analyzer-model 2700/480 | Beckman Coulter |

| Very low-density lipoprotein | Serum | Auto-analyzer-model 2700/480 | Beckman Coulter |

| High-density lipoprotein | Polyethylene glycol-pretreated enzymes | Auto-analyzer-model 2700/480 | Beckman Coulter |

SES=Socioeconomic status, NAS=Numerical Analog Scale, HbA1c=Hemoglobin A1c, PSS=Perceived stress scale, PHQ=Patient health questionnaire, PPBG=Postprandial blood glucose, FBG=Fasting blood glucose

Follow-up

After the initial 9-day introductory camp, the participants were asked to continue the practices for 1 h daily and maintain a diary. In several rural areas (about 30% of villages), the participants decided to get together daily in the same venue instead of practicing individually in their houses. The YVDMs planned and conducted weekly 2-h Sunday morning group classes where yoga camps were conducted. The YVDMs created a WhatsApp group including all participants of the 9-day introductory camps. This facilitated in sending reminders for the weekly interactive review follow-up classes, monitoring their compliance of daily practices, and helping for any of their health-related issues. There were no major issues reported by the participants during the 3-month period.

The dates of the camps had to be changed in nine places due to unavoidable circumstances such as local weather condition (heavy rains in south or snow fall in northwest zones), unexpected local political situation (roadblock in Manipur and election in Uttar Pradesh), illness of the SRF (Andhra and Kerala), and shifting of the SRF due to national cause (navy officer was the SRF in Goa who was transferred), resulting in delay in completion of the project by 2 months.

Postintervention data [Table 7] were collected at the end of 3 months in both yoga and control locations by organizing the second round of assessments in the same venues by the same research team who were involved earlier.

The YVDMs logged in the post data on the mobile app. The SRF was available for help in clearing any doubts of YVDMs. Post data were checked during the regular visit of the SRF and random visits of zonal coordinator and RA. Quality control was implemented for each blood sample at the National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (NABL) NABL-accredited laboratory.

Statistical analysis

Data were uploaded via mobile apps by the YVDMs under the supervision of SRFs. Pre- and post-data were checked and matched. SPSS software version 21 and R software version 3.5.2 (IBM Company, Armonk, New York 10504, United States of America;) for bio-statistical analyses were used for analysis. Cases with missing data were checked for uniformity and excluded from the analysis.

Cases with missing data (at the time of entry or technical errors while downloading) were examined, and a protocol to manage such cases was drafted. For the latter, the data were downloaded again from the server to retrieve all possible data. If the missing data were less than 15%, after stratifying for area, gender, and age, the imputation (median/mean values) procedure was followed. Those that had more than 15% missing data were excluded from the analysis.

The plan of analysis of data included (i) comparison of means of before and after the intervention between and within groups using paired samples t-test and/or repeated-measures ANOVA tests after checking for normality of data, (ii) Chi-square test for significance of the pre-post conversion, and (iii) binary logistic and multiple logistic regression analyses to estimate the degree of association between the variables.

Ethical clearance

Details of ethical clearance were presented in the other publication. In brief, the IYA's institutional ethical committee cleared the proposal after scrutinizing the complete project proposal including the headings in the budget to clarify that no payment in cash or kind was being offered to the participants and also checked the informed consent forms. The study was registered on the Clinical Trials Registry of India (registration number – trial REF/2018/02/017724).

Results

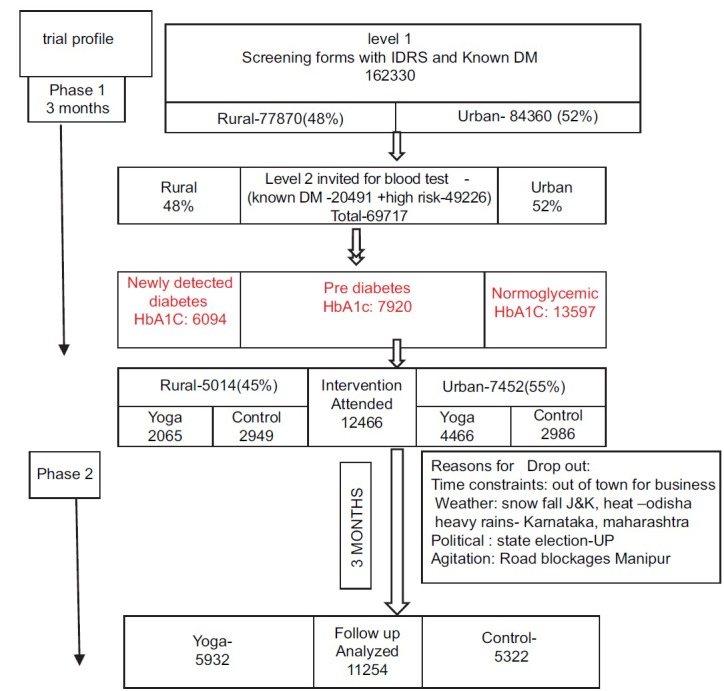

Table 7 shows the schedule and number of YVDM training camps conducted in different zones. We conducted a total of 145 yoga camps (81 in rural and 64 in urban areas). As against the planned 63 camps in rural areas (one per 2 yoga villages/district), 18 more camps were conducted in villages which were placed far apart, primarily due to the sparsely populated forest and hilly villages which were randomly selected. Figure 2 shows the study profile of this RCT. A total of 1,62,330 were screened and 69717 individuals were found eligible (Known diabetes and those at high score on IDRS) and hence invited to participate in the study. Of these 50199 subjects responded (72% response) and provided the pre intervention dataset for phase 2 of the trial. Out of these, 12466 (27.2%) consented to participate in the trial and Complete 3 month follow up data for analysis was available on 11254 (91.1%) who completed the 3 months follow up with 5932 under yoga arm and 5322 under control arm. Reasons for drop out (8%) are shown in the figure (mainly weather conditions). Although majority of them were interested they could not commit for 3 months of intervention [Figure 2] due to following key reasons: out of town for business or involved in social and political activities. About 9.8% expressed their unwillingness to participate as they were interested in other forms of exercise (they equated yoga to exercise) or due to religious reasons [Table 8].

Figure 2.

Trial profile

Table 8.

Yoga camps in different zones

| Zones | Rural | Urban | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conducted | Planned | Conducted | Planned | |

| Northwest (J and K) | 8 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| North | 11 | 12 | 14 | 12 |

| Northeast | 12 | 10 | 13 | 10 |

| Central | 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| East | 9 | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| West | 9 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| South | 19 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Total | 83 | 63 | 64 | 63 |

Table 9 shows the characteristics of the participants of the two groups. The mean age was similar in both groups, higher in known diabetes group. There were more female participants in both groups. Participation in urban area was high in both groups. The mean BMI, waist circumference, and HbA1c were higher in the known diabetes group.

Table 9.

Baseline characteristics of yoga and control groups

| Characteristics | Overall | Yoga group | Control group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Known DM | Others with high risk on IDRS | Known DM | Others with high risk on IDRS | ||

| Overall, n (%) | 12,364 | 732 (5.9) | 5932 (48) | 378 (3.7) | 5322 (43.0) |

| Age, mean±SD | 49.4±10.6 | 52.3±10.8 | 48.6±10.7 | 52.9±10.2 | 48.4±10.2 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female, n (%) | 7093 (58.2) | 381 (3.0) | 3440 (27.8) | 188 (1.5) | 3084 (24.9) |

| Male, n (%) | 5271 (41.8) | 351 (2.8) | 2492 (20.1) | 190 (1.53) | 2238 (18.1) |

| Location | |||||

| Rural, n (%) | 4740 (37.8) | 241 (1.9) | 1792 (14.5) | 167 (1.3) | 2540 (20.5) |

| Urban, n (%) | 7733 (62.1) | 555 (4.5) | 4155 (33.6) | 245 (1.97) | 2778 (22.4) |

| BMI, mean±SD | 21.1±3.80 | 26.32±4.32 | 20.7±3.70 | 26.5±4.5 | 20.5±3.67 |

| Waist circumference, mean±SD | 91.7±11.9 | 91.76±12.0 | 91.6±12.2 | 92.85±11.9 | 92.1±11.4 |

| HbA1c, mean±SD | 6.28±1.47 | 7.63±2.17 | 6.31±1.46 | 7.86±2.13 | 6.25±1.49 |

HbA1c=Hemoglobin A1c, BMI=Body mass index, SD=Standard deviation, DM=Diabetes mellitus, IDRS=Indian Diabetes Risk Score

Discussion

The present pan-India study (covering 95% of India's population) on yoga-based lifestyle intervention was an attempt to provide scientific evidence for the primary prevention of T2DM in both urban and rural sectors through community-based nationwide yoga-based lifestyle intervention aimed at turning the tide of India's increasing diabetes prevalence.

This multicentric study adopted the principles of a RCT and targeted those at high risk for diabetes, those with prediabetes, and also patients with known or newly diagnosed diabetes. This article describes the methodology of the intervention study including developing the common yoga-based lifestyle module. Yoga-based lifestyle therapy was offered to the participants near their residence. The critical need for human resources in the management of chronic lifestyle and behavioral disorders is universally acknowledged. The design of the trial offers solution to the huge challenge of availability of lifestyle trainers in all parts of the country including remote places such as Jammu and Kashmir and Andaman, interior tribal areas such as Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, or the thinly populated interior forests such as Dakshina Kannada district of Karnataka. The IYA, the professional association of yoga teachers, provided the army of staff needed for implementation of the intervention: 1200 YVDMs, 35 supervisors, and 2 overall coordinators. Leveraging on technology, it was possible to closely monitor the progress of the study.

Deviation from the planned protocol was minimal. In 35 (29%) rural areas in south, north, and west zones, daily classes were conducted for 3 months (instead of once-a-week follow-up classes after the 9-day camps) on request by the enthusiastic participants and the local authorities.

Strengths of the study

This is the first large, nationwide, translational two-armed RCT that has looked at the effect of a standardized yoga lifestyle protocol in prediabetes in urban and rural population in India. The project, including the survey and intervention, was completed within 7 months. No major adverse effects were reported in any of the places and when reported, they included mild degree of spinal and knee pain, and generalized body aches which were handled by offering corrective postures and relaxation techniques on consultation on WhatsApp with senior medical yoga professionals such as RA and PI, and/or medication on advice of local family doctors.

The numbers obtained at the end of the study period were found to be adequately powered to achieve the objectives set out at the beginning, namely, to document the efficacy of the structured intervention to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes.

Missing and wrong data entry (extreme values for blood pressure, weight, etc.) appears to be a key limitation; however, it is unlikely to influence the outcome of the intervention component of the study primarily as the outcomes measured are objective and hard outcomes.

A major strength of this study was involvement by volunteers. Except for the RAs and SRFs, all others were paid a nominal honorarium just enough for boarding and lodging. We consider this to be a key issue as it makes the study and its methods more pragmatic and scalable.

Suggestions for future work

This recruited population may be followed up regularly to look at the long-term effects of yoga on lifestyle behavior. As yoga can be continued as culturally acceptable group practice, this may offer long-term answer to prevent India from becoming the global capital for diabetes.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, the Ministry of AYUSH, and Government of India, New Delhi, and Dr. Ishwar Acharya, the director of CCRYN, Government of India, New Delhi, sponsored the production of DVDs and preparation of booklets on yoga for diabetes.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, the Ministry of AYUSH, and Government of India, New Delhi, for funding this trial. We also thank Dr. Ishwar Acharya, the director of CCRYN, Government of India, for sponsoring the production of DVDs and preparation of booklets on yoga for diabetes. We are grateful to the members of the research advisory committee and yoga protocol committee for their inputs. We are indebted to the yoga masters of IYA including Sri Sri Ravishankar Guruji, Swami Ramdev, Swami Bharat Bhushan, and Sri Subodh Tiwari for their encouragement and contribution through their YVDMs as field officers for this trial. We thank the software team, RAs, all SRFs, yoga volunteers, and faculty and staff of VYASA and S-VYASA for their committed involvement during the implementation of the trial.

References

- 1.Zhang P, Zhang X, Brown J, Vistisen D, Sicree R, Shaw J, et al. Global healthcare expenditure on diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH. Global burden of diabetes, 1995-2025: Prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1414–31. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howells L, Musaddaq B, McKay AJ, Majeed A. Clinical impact of lifestyle interventions for the prevention of diabetes: An overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e013806. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, Gregg EW, Yang W, Gong Q, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing diabetes prevention study: A 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371:1783–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber MB, Ranjani H, Staimez LR, Anjana RM, Ali MK, Narayan KM, et al. The stepwise approach to diabetes prevention: Results from the D-CLIP randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1760–7. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monro R, Power J, Coumar A, Nagarathna R, Dandona P. Yoga therapy for NIDDM: A controlled trial. Complement Med Res. 1992;6:66–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar V, Jagannathan A, Philip M, Thulasi A, Angadi P, Raghuram N. Role of yoga for patients with type II diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2016;25:104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagaraj C, Manjunath NK, Nataraj HR. Effect of integrated yoga therapy on nerve conduction velocity in type-2 diabetics a cross sectional clinical study. Int Ayurveda Med J. 2013;1:119–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaya MS, Ramakrishnan G, Shastry S, Kishore RP, Nagendra H, Nagarathna R, et al. Insulin sensitivity and cardiac autonomic function in young male practitioners of yoga. Natl Med J India. 2008;21:217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross A, Thomas S. The health benefits of yoga and exercise: A review of comparison studies. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:3–12. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govindaraj R, Karmani S, Varambally S, Gangadhar BN. Yoga and physical exercise – A review and comparison. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28:242–53. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2016.1160878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDermott KA, Rao MR, Nagarathna R, Murphy EJ, Burke A, Nagendra RH, et al. A yoga intervention for type 2 diabetes risk reduction: A pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:212. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonita R, de Courten M, Dwyer T, Jamrozik K, Winkelmann R. Summary. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Surveillance of Risk Factors for Noncommunicable Diseases: The WHO STEPwise Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binson D, Canchola JA, Catania JA. Random selection in a national telephone survey: A comparison of the Kish, next-birthday, and last-birthday methods. J Official Stat Stockholm. 2000;16:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kish L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. J Am Stat Assoc. 1949;44:380–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thulasi A, Kumar V, Jagannathan A, Angadi P, Umamaheshwar K, Nagarathna R. Development, validation and feasibility testing of yoga program for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Religion Health. 2019;1:5. doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00859-x. doi: 10.1007/ s10943-019-00859-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ley SH, Hamdy O, Mohan V, Hu FB. Prevention and management of type 2 diabetes: Dietary components and nutritional strategies. Lancet. 2014;383:1999–2007. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60613-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Yardley JE, Riddell MC, Dunstan DW, Dempsey PC, et al. Physical activity/Exercise and diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:2065–79. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Surwit RS, van Tilburg MA, Zucker N, McCaskill CC, Parekh P, Feinglos MN, et al. Stress management improves long-term glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:30–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanya P, Telles S. A review of the scientific studies on cyclic meditation. Int J Yoga. 2009;2:46–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.60043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umashankar K, Subramanya P. Immediate effect of cyclic meditation on heart rate variability in patients suffering from type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Yoga Philos Psychol Para Psychol. 2016;4:49–50. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nayak HD, Patel NK, Wood R, Dufault V, Guidotti N. A Study to Identify the Benefits, Barriers, and Cues to Participating in a Yoga Program among Community Dwelling Older Adults. J Yoga Phys Ther. 2015;5:178. doi:10.4172/2157-7595.1000178. [Google Scholar]