Abstract

Objective

To develop and validate an integrative system to predict long term kidney allograft failure.

Design

International cohort study.

Setting

Three cohorts including kidney transplant recipients from 10 academic medical centres from Europe and the United States.

Participants

Derivation cohort: 4000 consecutive kidney recipients prospectively recruited in four French centres between 2005 and 2014. Validation cohorts: 2129 kidney recipients from three centres in Europe and 1428 from three centres in North America, recruited between 2002 and 2014. Additional validation in three randomised controlled trials (NCT01079143, EudraCT 2007-003213-13, and NCT01873157).

Main outcome measure

Allograft failure (return to dialysis or pre-emptive retransplantation). 32 candidate prognostic factors for kidney allograft survival were assessed.

Results

Among the 7557 kidney transplant recipients included, 1067 (14.1%) allografts failed after a median post-transplant follow-up time of 7.12 (interquartile range 3.51-8.77) years. In the derivation cohort, eight functional, histological, and immunological prognostic factors were independently associated with allograft failure and were then combined into a risk prediction score (iBox). This score showed accurate calibration and discrimination (C index 0.81, 95% confidence interval 0.79 to 0.83). The performance of the iBox was also confirmed in the validation cohorts from Europe (C index 0.81, 0.78 to 0.84) and the US (0.80, 0.76 to 0.84). The iBox system showed accuracy when assessed at different times of evaluation post-transplant, was validated in different clinical scenarios including type of immunosuppressive regimen used and response to rejection therapy, and outperformed previous risk prediction scores as well as a risk score based solely on functional parameters including estimated glomerular filtration rate and proteinuria. Finally, the accuracy of the iBox risk score in predicting long term allograft loss was confirmed in the three randomised controlled trials.

Conclusion

An integrative, accurate, and readily implementable risk prediction score for kidney allograft failure has been developed, which shows generalisability across centres worldwide and common clinical scenarios. The iBox risk prediction score may help to guide monitoring of patients and further improve the design and development of a valid and early surrogate endpoint for clinical trials.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03474003.

Introduction

End stage renal disease affects an estimated 7.4 million people worldwide.1 2 According to data from the World Health Organization, more than 1 500 000 people live with transplanted kidneys, and 80 000 new kidneys are transplanted each year.3 Despite the considerable advances in short term outcomes, kidney transplant recipients continue to experience late allograft failure, and little improvement has been made over the past 15 years.4 5 Although the failure of a kidney allograft represents an important cause of end stage renal disease, robust and widely validated prognostication systems for the risk of allograft failure in individual patients are lacking.6 Accurately predicting individual patients’ risk of allograft loss would help to stratify patients into clinically meaningful risk groups, which may help to guide monitoring of patients. Moreover, regulatory agencies and medical societies have highlighted the need for an early and robust surrogate endpoint in transplantation that adequately predicts long term allograft failure.7 An enhanced ability to predict allograft outcomes would not only inform daily clinical care, counselling of patients, and therapeutic decisions but also facilitate the performance of clinical trials, which generally lack statistical power because of the low event rates during the first year after transplantation.8

Taken individually, parameters such as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR),9 10 proteinuria,11 histology,12 or human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antibody profiles,13 fail to provide sufficient predictive accuracy. Previous efforts at developing prognostic systems in nephrology based on various combinations of parameters have been hampered by small sample sizes, the absence of proper validation, limited phenotypic details from registries, the absence of systematic immune response monitoring, and the failure to include key prognostic factors that affect allograft outcome (for example, donor derived factors, polyoma virus associated nephropathy, disease recurrence).14 15 16 Finally, no scoring system has been evaluated in large cohorts from different countries with different transplant practices, allocation systems, and practice patterns, thereby limiting their exportability, which is an important consideration for health authorities to accept a scoring system as a surrogate endpoint.17

The objectives of this study (NCT03474003) were to develop a practical risk stratification score in a multicentre, prospective cohort of kidney transplant recipients that could be used to identify patients at high risk of future allograft loss; to validate the score on a large scale in geographically distinct independent cohorts with different allocation policies and types of transplant management; and to test the performance of the risk score for predicting graft failure in randomised controlled trials covering distinct clinical scenarios of transplant.

Methods

Study design and participants

Derivation cohort.

The derivation cohort consisted of 4000 consecutive patients over 18 years of age who were prospectively enrolled at the time of transplantation of a kidney from a living or deceased donor at Necker Hospital (n=1473), Saint-Louis Hospital (n=928), Foch Hospital (n=714), and Toulouse Hospital (n=885) in France between 1 January 2005 and 1 January 2014. We excluded patients with grafts that never functioned (primary non-functioning grafts; n=116). The clinical data were collected from each centre and entered into the Paris Transplant Group database (French data protection authority (CNIL) registration number: 363505). All data were anonymised and prospectively entered at the time of transplantation, at the time of post-transplant allograft biopsies, and at each transplant anniversary by using a standardised protocol to ensure harmonisation across study centres. We submitted data from the derivation cohort for an annual audit to ensure data quality (see the methods section and the study protocol in the supplementary material for detailed data collection procedures). We retrieved data from the database in March 2018. All patients provided written informed consent at the time of transplantation.

Validation cohorts.

The external validation cohorts comprised 3557 recipients of kidney transplants from a living or a deceased donor who were over 18 years of age and represented all patients eligible for post-transplant risk evaluation (that is, undergoing allograft biopsy as part of the standard of care of each centre with adequate biopsy according to the Banff criteria) from six centres: 2129 recipients recruited in Europe and 1428 recipients recruited in the US between 2002 and 2014. The European centres were Hôpital Hôtel Dieu, Nantes, France (n=632); Hospices Civils, Lyon, France (n=608); and the University Hospitals, Leuven, Belgium (n=889). The US centres were the Johns Hopkins Medical Institute, Baltimore, MD (n=580); the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN (n=556); and the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Richmond, VA (n=292). Datasets from the validation centres were prospectively collected as part of routine clinical practice, entered in the centres’ databases in compliance with local and national regulatory requirements, and sent anonymised to the Paris Transplant Group.

In France, the transplantation allocation system followed the rules of the French National Agency for Organ Procurement (Agence de la Biomédecine). The European centre outside France (Leuven) followed the rules of the Eurotransplant allocation system (https://www.eurotransplant.org), and the US centres (Johns Hopkins Hospital, Mayo Clinic, and Virginia) followed the rules of the US Organ Procurement and Transplantation System (https://unos.org/).

Additional external validation cohort.

Additional external validation was conducted in kidney transplant recipients previously recruited in three registered and published phase II and III clinical trials: a randomised, open label, multicentre trial that compared a cyclosporine based immunosuppressive regimen with an everolimus based regimen in kidney recipients (Certitem, NCT01079143); a randomised, multicentre, double blind, placebo controlled trial that investigated the efficacy of rituximab in kidney recipients with acute antibody mediated rejection (Rituxerah, EudraCT 2007-003213-13); and a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, single centre trial that investigated the efficacy of bortezomib in kidney recipients with late antibody mediated rejection (Borteject, NCT01873157).18 19 20 The details of the clinical trials including the population characteristics, study design, inclusion criteria, and interventions are provided in supplementary table A.

Candidate predictors

Post-transplant risk evaluation times

Risk evaluation after transplantation was conducted at the time of allograft biopsy performed for clinical indication or as per protocol, which was performed after transplantation according to the centres’ practices. In patients with multiple biopsies, risk evaluation used the date of the first biopsy. The distribution of post-transplant risk evaluation times is provided in supplementary figure A.

Risk evaluation after transplant comprised demographic characteristics (including recipients’ comorbidities, age, sex, and transplant characteristics), biological parameters (including kidney allograft function, proteinuria, and circulating anti-HLA antibody specificities and concentrations), and allograft pathology data (including elementary lesion scores and diagnoses). All these factors are commonly and routinely collected in kidney transplant centres worldwide. See supplementary methods for the list of all prognostic determinants assessed from the derivation cohort.

Measurements performed at time of risk evaluation

Kidney allograft function was assessed by the glomerular filtration rate estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation (eGFR) and proteinuria level by using the protein/creatinine ratio in the derivation and validation cohorts. Circulating donor specific antibodies against HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-Cw, HLA-DR, HLA-DQ, and HLA-DP were assessed using single antigen flow bead assays in the derivation cohort (see supplementary methods) and according to local centres’ practice in the validation cohorts. Kidney allograft pathology data, including elementary lesion scores and diagnoses, were recorded according to the Banff classification in the derivation and validation cohorts (see supplementary methods). All the measurements (eGFR, proteinuria, histopathology, and circulating anti-HLA DSA) were performed on the day of risk evaluation.

Outcome

The outcome of interest was allograft loss defined as a patient’s definitive return to dialysis or pre-emptive kidney retransplantation. This outcome was prospectively assessed in the derivation and validation cohorts at each transplant anniversary up to 31 March 2018.

Missing data

We excluded 59 (0.01%) patients in the derivation cohort from the final model owing to at least one data point being missing. We excluded 158 (7.4%) patients in the European validation cohort and 71 (5.0%) in the North American validation cohort from the final model owing to at least one data point being missing.

Statistical analysis

We followed the TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis) statement (supplementary methods) for reporting the development and validation of the multivariable prediction model.21 We describe continuous variables by using means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges. We compared means and proportions between groups by using Student’s t test, analysis of variance (Mann-Whitney test for mean fluorescence intensity), or the χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test if appropriate). We used the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate graft survival. The duration of follow-up was from the patient’s risk evaluation (starting point) to the date of kidney allograft loss or the end of the follow-up (31 March 2018). For patients who died with a functioning allograft, allograft survival was censored at the time of death as a surviving or functional allograft.22

In the derivation cohort, we used univariable Cox regression analyses to assess the associations between allograft failure and clinical, histological, functional, and immunological factors measured at the patient’s risk evaluation (see above). We used the log graphic method to test hazard proportional assumptions. The factors identified in these analyses were thereafter included in a final multivariable model.

We confirmed the internal validity of the final model by using a bootstrap procedure, which involved generating 1000 datasets derived from resampling the original dataset and permitting the calculation of optimism corrected performance estimates.23 We tested the centre effect in stratified analyses. We investigated potential non-linear relations between continuous predictors and graft loss by using fractional polynomial methods (see supplementary methods).

We assessed the accuracy of the prediction model on the basis of its discrimination ability and calibration performance. We evaluated the discrimination ability (the ability to separate patients with different prognoses) of the final model by using Harrell’s concordance index (C index) (see supplementary methods).24 We assessed calibration (the ability to provide unbiased survival predictions in groups of similar patients) on the basis of a visual examination of the calibration plots by using the rms package in R. We used the SurvIDINRI package in R to calculate net reclassification improvement for censored survival data.25 26 We then evaluated the external validity of the final model in the external validation cohorts, including discrimination tests and model calibration as mentioned above.

We calculated a risk prediction score (integrative box risk prediction score—iBox) for each patient according to the β regression coefficients estimated from the final multivariable Cox model. Allograft survival probabilities are given at three, five, and seven years after iBox risk evaluation. The seven year post-transplant iBox risk assessment was guided by the median follow-up after iBox risk assessment of 7.65 (interquartile range 5.39-8.21) years.

We used R version 3.2.1 foe all analyses and considered P values below 0.05 to be significant; all tests were two tailed. Details of the interpretation of important statistical concepts are given in the supplementary methods.

Patient and public involvement

The iBox initiative, including study design, study results, and potential for patient care, was presented and discussed among the two main French patients’ associations, involving patients, nurses, and healthcare professionals.

Results

Characteristics of derivation and validation cohorts

The derivation cohort (n=4000) and the two validation cohorts (n=3557) comprised a total of 7557 participants with 1067 (14.1%) allograft failures after a median post-transplant follow-up time of 7.12 (interquartile range 3.51-8.77) years. The characteristics of the derivation and validation cohorts (overall, European, and US validation cohorts), as well as the transplant procedures, policies and allocation systems, are detailed in table 1 and supplementary tables B-D. The distribution of the time of the post-transplant risk evaluation is provided in supplementary figure A. The median time from kidney transplantation to post-transplant risk evaluation was 0.98 (0.27-1.07) years in the derivation cohort and 0.99 (0.18-1.04) years in the validation cohort. The median follow-up after transplantation was 7.65 (5.39-8.21) years in the derivation cohort. The cumulative numbers of graft losses in the development cohort were 332 at three years, 449 at five years, and 549 at seven years.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics by cohort. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Derivation cohort (n=4000) | European validation cohort (n=2129) | US validation cohort (n=1428) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient demographics | ||||

| Mean (SD) age, years | 49.83 (13.7) | 50.58 (13.66) | 50.42 (14.17) (n=1420) | 0.09 |

| Male sex | 2450 (61.3) | 1333 (62.6) | 830 (58.1) | 0.02 |

| Cause of end stage renal disease: | <0.001 | |||

| Glomerulonephritis | 1086 (27.2) | 584 (27.4) | 365 (25.6) | |

| Diabetes | 438 (11.0) | 316 (14.8) | 271 (19.08) | |

| Vascular | 296 (7.4) | 139 (6.5) | 249 (17.4) | |

| Other | 2180 (54.5) | 1090 (51.2) | 543 (38.0) | |

| Transplant characteristics | ||||

| Mean (SD) donor age, years | 51.68 (16.33) | 48.24 (15.79) (n=2122) | 41.01 (14.75) (n=1420) | <0.001 |

| Male donor | 2151 (53.8) | 1225/2124 (57.7) | 694/1420 (48.9) | <0.001 |

| Donor with hypertension | 1005/3903 (25.7) | 450/1876 (24.0) | 189/1287 (14.7) | <0.001 |

| Donor with diabetes mellitus | 231/3861 (6.0) | 47/1713 (2.7) | 47/1276 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Donor with serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dL | 422/3962 (10.7) | 193/1936 (10.0) | 284/1075 (26.4) | <0.001 |

| Donor type: | ||||

| Deceased donor | 3327 (83.2) | 1974 (92.7) | 620 (43.4) | <0.001 |

| Death from cerebrovascular disease | 1864/3327 (56.0) | 993/1974 (50.3) | 194/618 (31.4) | <0.001 |

| Expanded criteria donor | 1409/3995 (35.3) | 628/2010 (31.2) | 72/1425 (5.1) | <0.001 |

| Prior kidney transplant | 605 (15.1) | 322 (15.1) | 235/1408 (16.7) | 0.34 |

| Mean (SD) cold ischaemia time, hours | 16.20 (8.99) (n=3976) | 15.50 (7.30) (n=2093) | 9.51 (11.81) (n=1212) | <0.001 |

| Delayed graft function† | 1046/3897 (26.8) | 476/2127 (22.40) | 158/1424 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) No with HLA-A/B/DR mismatch | 3.817 (1.36) | 3.15 (1.39) (n=2083) | 3.54 (1.79) (n=1427) | <0.001 |

HLA=human leucocyte antigen.

Based on comparison of all cohorts.

Defined as use of dialysis in first postoperative week.

Prediction of kidney allograft failure in derivation cohort

We first investigated the prognostic factors measured at the time of post-transplant risk evaluation that were associated with long term kidney allograft failure in a univariable analysis. These factors included recipient’s demographics, characteristics of transplant, allograft functional parameters, immunological parameters, and allograft histopathology (table 2). In the multivariable analysis, the following independent predictors of long term allograft failure were identified: time of post-transplant risk evaluation (P=0.005); allograft functional parameters, including eGFR (P<0.001) and proteinuria (logarithmic transformation, P<0.001); allograft histological parameters, including interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (P=0.031), microcirculation inflammation defined by glomerulitis and peritubular capillaritis (P=0.001), interstitial inflammation and tubulitis (P=0.014), and transplant glomerulopathy (P=0.004); and recipient’s immunological profile as defined by the presence and concentration of the immunodominant circulating anti-HLA donor specific antibodies (P<0.001) (table 3). We used a Cox model stratified by centre to test the effect of centre. We obtained stratified estimates (with equal coefficients across centres but with a baseline hazard unique to each centre). We confirmed that the eight prognostic parameters identified in the primary analysis remained independently associated with allograft survival (supplementary table E).

Table 2.

Factors assessed at time of post-transplant risk evaluation associated with kidney allograft failure in derivation cohort: univariable analysis

| No of patients | No of events* | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient characteristics | ||||

| Age (per 1 year increment) | 4000 | 549 | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.01) | 0.46 |

| Sex: | 0.97 | |||

| Female | 1550 | 214 | 1 | |

| Male | 2450 | 335 | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.19) | |

| Transplant characteristics | ||||

| Donor age (per 1 year increment) | 4000 | 549 | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.02) | <0.001 |

| Donor sex: | 0.83 | |||

| Female | 1849 | 254 | 1 | |

| Male | 2151 | 295 | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.16) | |

| Donor type: | <0.001 | |||

| Living | 673 | 51 | 1 | |

| Deceased | 3327 | 498 | 2.06 (1.54 to 2.74) | |

| Donor after cardiac death†: | 0.22 | |||

| No | 3234 | 489 | 1 | |

| Yes | 93 | 9 | 1.51 (0.78 to 2.92) | |

| Donor hypertension: | <0.001 | |||

| No | 2898 | 340 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1005 | 195 | 1.84 (1.54 to 2.20) | |

| Donor diabetes mellitus: | 0.05 | |||

| No | 3630 | 491 | 1 | |

| Yes | 231 | 31 | 1.392 (1.01 to 1.93) | |

| Creatinine concentration: | 0.004 | |||

| <1.5 mg/dL | 3540 | 467 | 1 | |

| ≥1.5 mg/dL | 422 | 75 | 1.43 (1.12 to 1.82) | |

| Expanded criteria donor: | <0.001 | |||

| No | 2586 | 285 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1409 | 263 | 1.90 (1.60 to 2.24) | |

| Previous kidney transplant: | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3395 | 421 | 1 | |

| Yes | 605 | 128 | 1.86 (1.53 to 2.27) | |

| Cold ischaemia time: | ||||

| <12 hours | 1120 | 106 | 1 | <0.001 |

| 12-24 hours | 2099 | 319 | 1.61 (1.30 to 2.01) | |

| ≥24 hours | 757 | 121 | 1.73 (1.33 to 2.25) | |

| Thymoglobulin induction immunosuppression: | 0.012 | |||

| No | 1643 | 109 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2104 | 316 | 1.25 (1.05 to 1.49) | |

| No of HLA-A/B/DR mismatches | 4000 | 549 | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.10) | 0.29 |

| Delayed graft function†: | <0.001 | |||

| No | 2851 | 362 | 1 | |

| Yes | 104 | 246 | 1.94 (1.63 to 2.30) | |

| Pre-existing anti-HLA donor-specific antibody: | 0.001 | |||

| No | 3278 | 425 | 1 | |

| Yes | 722 | 124 | 1.51 (1.23 to 1.84) | |

| Time of risk evaluation | ||||

| Time from transplant to evaluation (per 1 year increment) | 3996 | 549 | 1.26 (1.21 to 1.33) | <0.001 |

| Functional parameters | ||||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 4000 | 549 | 0.94 (0.94 to 0.95) | <0.001 |

| Proteinuria at 1 year (log transformation) | 4000 | 549 | 1.99 (1.86 to 2.13) | <0.001 |

| Structural-histopathology parameters | ||||

| Interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy: | <0.001 | |||

| 0-1 | 3099 | 331 | 1 | |

| 2 | 555 | 116 | 2.15 (1.74 to 2.66) | |

| 3 | 321 | 95 | 3.36 (2.67 to 4.22) | |

| Arteriosclerosis: | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 1365 | 137 | 1 | |

| ≥1 | 2446 | 386 | 1.62 (1.33 to 1.97) | |

| Hyalinosis: | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 1567 | 149 | 1 | |

| ≥1 | 2360 | 381 | 1.74 (1.44 to 2.10) | |

| Interstitial inflammation and tubulitis: | <0.001 | |||

| 0-2 | 3610 | 546 | 1 | |

| ≥3 | 390 | 93 | 1.97 (1.58 to 2.46) | |

| Transplant glomerulopathy: | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 3702 | 449 | 1 | |

| ≥1 | 260 | 94 | 3.70 (2.96 to 4.62) | |

| Endarteritis: | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 3794 | 506 | 1 | |

| ≥1 | 96 | 27 | 2.26 (1.54 to 3.33) | |

| C4d graft deposition: | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3452 | 416 | 1 | |

| Yes | 548 | 133 | 2.45 (2.01 to 2.98) | |

| Microcirculation inflammation (g+ptc): | <0.001 | |||

| 0-2 | 3616 | 261 | 1 | |

| 3-4 | 308 | 92 | 3.07 (2.45 to 3.85) | |

| 5-6 | 76 | 35 | 4.99 (3.53 to 7.04) | |

| Polyomavirus associated nephropathy: | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3902 | 518 | 1 | |

| Yes | 97 | 31 | 2.82 (1.96 to 4.05) | |

| Nephropathy recurrence: | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3868 | 510 | 1 | |

| Yes | 130 | 38 | 2.55 (1.84 to 3.55) | |

| Antibody mediated rejection: | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3398 | 368 | 1 | |

| Yes | 600 | 181 | 3.36 (2.81 to 4.02) | |

| T cell mediated rejection: | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3812 | 503 | 1 | |

| Yes | 187 | 46 | 1.96 (1.45 to 2.66) | |

| Immunological parameters | ||||

| Anti-HLA donor specific antibody mean fluorescence intensity | <0.001 | |||

| <500 | 3312 | 394 | 1 | |

| ≥500-3000 | 483 | 82 | 1.66 (1.31 to 2.11) | |

| ≥3000-6000 | 82 | 24 | 3.11 (2.06 to 4.70) | |

| ≥6000 | 123 | 49 | 4.56 (3.38 to 6.14) | |

C4d=C4d stain; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; g=glomerulitis score; HLA=human leukocyte antigen; ptc=peritubular capillaratis score.

Number of events at 7 years after iBox risk evaluation.

Among deceased donors.

Table 3.

Independent determinants of kidney allograft loss assessed at time of post-transplant risk evaluation in derivation cohort: multivariable analysis

| Factor | No of patients | No of events* | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time from transplant to evaluation (years) | 3941 | 538 | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.14) | 0.005 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 3941 | 538 | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.96) | <0.001 |

| Proteinuria (log) | 3941 | 538 | 1.51 (1.40 to 1.63) | <0.001 |

| Interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy: | 0.03 | |||

| 0/1 | 3074 | 330 | 1 | |

| 2 | 550 | 115 | 1.14 (0.92 to 1.42) | |

| 3 | 317 | 93 | 1.39 (1.08 to 1.77) | |

| Microcirculation inflammation (g+ptc): | 0.001 | |||

| 0-2 | 3568 | 414 | 1 | |

| 3-4 | 299 | 90 | 1.45 (1.12 to 1.88) | |

| 5-6 | 74 | 34 | 1.83 (1.24 to 2.71) | |

| Interstitial inflammation and tubulitis (i+t): | 0.01 | |||

| 0-2 | 3559 | 447 | 1 | |

| ≥3 | 382 | 91 | 1.34 (1.06 to 1.68) | |

| Transplant glomerulopathy (cg) | 0.004 | |||

| 0 | 3684 | 445 | 1 | |

| ≥1 | 257 | 93 | 1.47 (1.13 to 1.90) | |

| Anti-HLA donor specific antibody mean fluorescence intensity | 0.001 | |||

| <500 | ||||

| ≥500-3000 | 477 | 80 | 1.25 (0.97 to 1.61) | |

| ≥3000-6000 | 80 | 23 | 1.72 (1.13 to 2.66) | |

| ≥6000 | 119 | 48 | 2.05 (1.47 to 2.86) |

cg=transplant glomerulopathy score; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; g=glomerulitis score; HLA=human leukocyte antigen; i=interstitial inflammation score; ptc=peritubular capillaratis score; t=tubulitis score.

Number of events at 7 years after iBox risk evaluation.

We calculated the prognostic score, named iBox, for each patient according to the β regression coefficients estimated from the final multivariable Cox model. On the basis of this score, we built a ready to use online interface for the clinician to provide allograft survival estimates for individual patients (http://www.paristransplantgroup.org). We are also providing, in supplementary figure B, examples of clinical use of iBox risk prediction scoring in daily practice.

Prediction model performance in internal and external validation cohorts

We first internally validated the final multivariable model via a bootstrapping procedure with 1000 samples from the original dataset of the derivation cohort (supplementary methods). Using this approach, we confirmed the robustness of the final multivariable model: the internal validity of the final model using a bootstrap procedure, which involved generating 1000 datasets derived from resampling the original dataset, thus permitting the calculation of optimism corrected performance estimates. Models were fitted for each of the 1000 samples by using backwards elimination. The eight independent predictors identified in the final multivariable Cox model were replicated in more than 85% of the 1000 estimated models. We also confirmed the discrimination ability of the model at three, five, and seven years (C index 0.835 (95% confidence interval 0.813 to 0.856), 0.819 (0.799 to 0.839), and 0.808 (0.790 to 0.827), respectively) by internally validating it using bootstrap resampling with optimism corrected C index 0.831 (0.813 to 0.854), 0.816 (0.799 to 0.837), and 0.806 (0.790 to 0.827) at three, five, and seven years, respectively.

We then used several independent validation cohorts and confirmed the transportability of the iBox risk score in these geographically distinct cohorts. The cumulative number of allograft losses were 72 (3.4%), 155 (7.3%), and 206 (9.7%) in the European validation cohort and 73 (5.1%), 108 (7.6%), and 148 (10.4%) in the US validation cohort at three, five, and seven years after iBox risk evaluation.

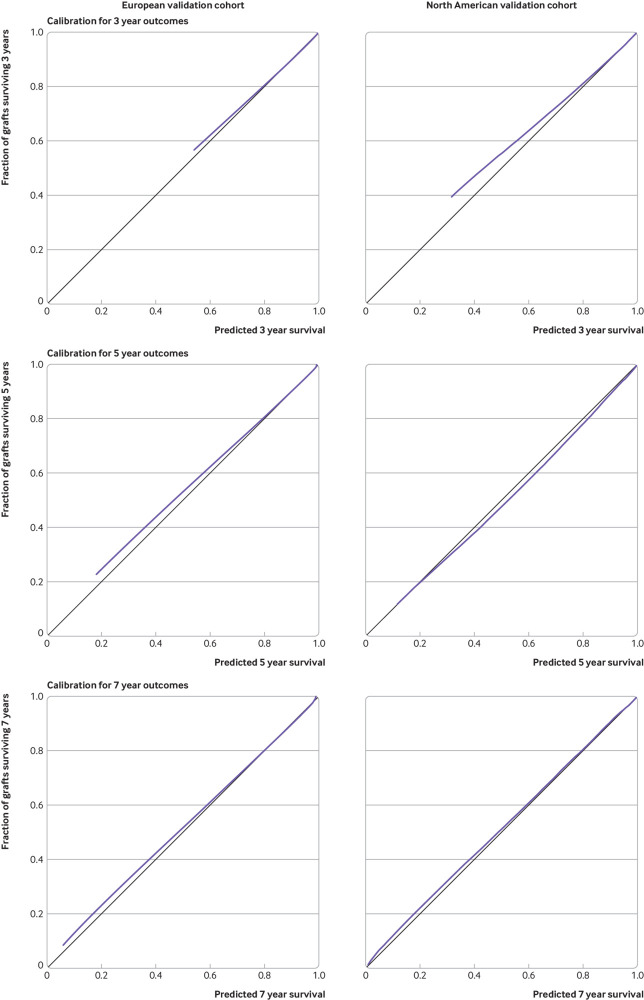

Overall, we showed good discrimination performance in the external validation cohorts with a C statistic of 0.81 (95% bootstrap percentile confidence interval 0.78 to 0.84) in Europe and 0.80 (0.76 to 0.84) in the US. Visual inspection of the calibration plots showed good agreement between the iBox risk score predicted probabilities of allograft survival at three, five, and seven years after risk evaluation and actual kidney allograft survival (fig 1).

Fig 1.

Calibration plots at three, five, and seven years of iBox risk scores for validation cohorts: three year (A, B), five year (C, D), and seven year (E, F) predictions. Data are from European validation cohort (A, C, E) and US cohort (B, D, F). Vertical axis is observed proportion of grafts surviving at time of interest. Average predicted probability (predicted survival; x-axis) was plotted against Kaplan-Meier estimate (observed overall survival; y-axis). Black line represents perfectly calibrated model, and blue line represents optimism corrected iBox model

Effect of therapeutic interventions on iBox risk score

We applied the iBox risk score to patients with therapeutic interventions, including 844 kidney transplant recipients from the derivation cohort who received standard of care treatment for antibody mediated rejection, standard of care treatment for T cell mediated rejection, and calcineurin inhibitor weaning for calcineurin inhibitor toxicity with belatacept (characteristics, protocols, and treatment interventions detailed in supplementary table F). Overall, we found that the therapeutic interventions were associated with significant changes in the iBox risk scores (supplementary figure C). The iBox prediction capability after treatment was accurate in these three therapeutic scenarios (C index 0.81, 95% bootstrap percentile confidence interval 0.77 to 0.85). The calibration plot showed a good agreement between the iBox prediction model after therapeutic intervention and the actual observation of kidney allograft loss.

Performance of iBox risk prediction score in therapeutic randomised controlled clinical trials

We tested the performance of the iBox risk prediction score in three registered and published phase II and III clinical trials.18 19 20 The details of the clinical trials including the population, intervention, clinical scenario, and follow-up times are presented in supplementary table A. We calculated the iBox risk prediction scores of all patients included in the trials and compared them with the actual allograft failures. The iBox risk prediction score applied in the three trials showed accurate discrimination overall (C index 0.87, 0.82 to 0.92). The calibration plot showed a good agreement between the risk prediction score based on predicted allograft loss and the actual observations of kidney allograft loss.

Sensitivity analyses

We did various sensitivity analyses to test the robustness and generalisability of the iBox risk score in different clinical scenarios and subpopulations.

iBox integrative risk prediction score using allograft monitoring (eGFR/proteinuria) parameters

We showed that the iBox risk score using the full model was superior in terms of prediction capability to a simplified iBox model including eGFR, proteinuria, and circulating anti-HLA DSA (C index 0.79, 0.77 to 0.81; P<0.001). This was further demonstrated by a continuous net reclassification improvement of 0.228 for the full iBox model compared with the simplified iBox model (95% confidence interval 0.174 to 0.290; P<0.001). To account for potentially different medico-economic contexts limiting the availability of allograft biopsies, we are providing a simplified iBox score based on functional-immunological parameters. The calibration plot showed a good agreement between allograft loss predicted by the simplified iBox model and the actual observations of kidney allograft loss.

Added value of iBox risk prediction score compared with previously reported risk scores

We did a systematic review (supplementary table G) and compared the iBox risk prediction score with previously published risk scores assessing long term allograft outcomes. This showed that the iBox prediction score outperformed other risk scores (supplementary table G).

Prediction model performance using histological diagnoses instead of Banff international classification histological lesion grading

When we included histological diagnoses in the multivariable model instead of histological lesions graded according to the international Banff classification, antibody mediated rejection (P<0.001), T cell mediated rejection (P=0.04), primary nephropathy recurrence (P=0.003), and BK virus nephropathy (P=0.05) showed significant and independent associations with allograft failure. In this model, the set of non-histological predictors of allograft failure identified in the primary analyses remained unchanged (hazard ratios are shown for each parameter in supplementary table H). The discrimination ability of the histological diagnosis based model showed a C index of 0.81 (0.79 to 0.83).

iBox performance when applied at time of clinically indicated biopsies versus protocol biopsies

We tested and confirmed the performance of the iBox risk prediction score when risk evaluation started at the time of clinically indicated allograft biopsies performed at any time after transplantation (n=1598; 40%), as well as at the time of one year protocol biopsies (n=2402; 60%) (table 4). Similarly, the iBox risk score showed accurate discrimination ability for long term allograft loss when risk evaluation started before one year post-transplant or after one year post-transplant (mean post-transplantation time of 0.89 (SD 0.23) years and 2.31 (1.66) years, respectively; table 4).

Table 4.

iBox risk prediction score performance when assessed in different clinical scenarios and subpopulations

| Clinical scenarios and subpopulations | No of patients | No of events | Risk model performance: C statistic (95% bootstrap percentile CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Using functional and immunological parameters | 3941 | 538 | 0.79 (0.77 to 0.81) |

| Using histological diagnoses* instead of Banff lesions grading | 3997 | 548 | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.83) |

| In stable patients (protocol biopsy) | 1160 | 85 | 0.81 (0.77 to 0.86) |

| In unstable patients (biopsy for cause) | 2781 | 453 | 0.80 (0.78 to 0.82) |

| In first year after transplant | 2300 | 291 | 0.78 (0.72 to 0.81) |

| After 1 year post-transplant | 1641 | 247 | 0.84 (0.82 to 0.87) |

| In living donors | 662 | 51 | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.88) |

| In deceased donors | 3279 | 487 | 0.80 (0.78 to 0.82) |

| In highly sensitised recipients† | 715 | 121 | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.84) |

| In non-highly sensitised recipients | 3226 | 417 | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.83) |

| Adding transplant baseline characteristics‡ | 3735 | 573 | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.83) |

| In patients with anti-IL2 receptor induction | 1621 | 206 | 0.79 (0.76 to 0.82) |

| In patients with anti-thymocyte globulin induction | 2069 | 308 | 0.83 (0.80 to 0.85) |

| In African-American population§ | 371 | 62 | 0.80 (0.74 to 0.85) |

| In non-African-American population§ | 986 | 77 | 0.84 (0.80 to 0.89) |

| Adding recipient blood pressure profile post-transplant¶ | 3973 | 541 | 0.80 (0.78 to 0.82) |

| Adding CNI blood trough concentration at time of evaluation | 3822 | 525 | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.83) |

CNI=calcineurin inhibitor; IL=interleukin.

Histological diagnoses defined by last update of Banff international classification: antibody mediated rejection, T cell mediated rejection, BK virus nephropathy, primary nephropathy recurrence.

Highly sensitised patients defined by panel of reactive antibodies >90%.

Donor’s age, donor’s sex, donor’s hypertension, donor’s diabetes, recipient’s age, recipient’s sex, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatches, retransplantation, and anti-HLA DSA at time of transplantation.

Status was retrieved in US participating centres’ databases (no ethnicity data allowed in French development cohort database according to the French law and regulation). African-Americans in US validation cohort represented 390 (27.3%) patients; Non-African-Americans in US validation cohort represented 1038 (72.7%) patients.

Blood pressure profile defined by systolic blood pressure measured at time of risk assessment on log scale.

iBox risk score performance versus risk score based on parameters assessed at time of transplantation

When we tested the parameters assessed at time of transplantation (recipient’s age, recipient’s sex, donor’s age, donor’s sex, deceased donor, donor’s cause of death, donor’s diabetes, donor’s hypertension, expanded criteria donor, previous kidney transplant, HLA mismatches, and anti-HLA donor specific antibody), none of them remained independently associated with allograft survival after adjustment for post-transplant parameters assessed at the time of iBox risk evaluation. Similarly, when we added day 0 parameters to the multivariable model including risk factors evaluated post-transplantation, we saw no improvement in its discrimination ability. Lastly, when we ran the Cox model with these parameters assessed at the time of transplantation, the C index was 0.62 (0.593 to 0.643).

iBox assessed in other clinical scenarios and subpopulations

Finally, we confirmed the performance of the iBox risk prediction score when applied in different subpopulations and clinical scenarios including living and deceased donors, according to recipient’s ethnicity, in highly sensitised (high immunological risk) and non-highly sensitised (low immunological risk) recipients, and in patients receiving induction by anti-interleukin-2 receptor or anti-thymocyte globulin (table 4). When parameters assessed at the time of transplant (such as HLA mismatches), recipient blood pressure at the time of risk assessment (log scale), and calcineurin inhibitor through blood concentration at the time of risk assessment were forced in the risk prediction score, we saw no significant improvement in its prognostic performance (table 4).

Discussion

The iBox, a risk prediction score combining functional, histological, and immunological allograft parameters together with HLA antibody profiling, showed good performance in predicting the risk of long term kidney allograft failure. We confirmed the generalisability of the iBox risk prediction score by showing its external validity in six geographically distinct cohorts recruited in Europe and the US with distinct allocation systems, patients’ characteristics, and management practices. The iBox risk prediction score also showed its accuracy when measured at different times after transplantation, which permits updating of the score on the basis of new events that patients might encounter in their long term course. We also showed that the iBox risk prediction score outperformed other available risk scores applied in kidney transplant patients. Lastly, we confirmed the predictive accuracy of the risk score in the data reported from three published randomised therapeutic trials covering different clinical scenarios encountered after transplantation, further enhancing its value as a potential surrogate endpoint in transplantation.18 19 20

Overall, the predictor variables used in the iBox risk prediction score are easily available after transplantation in most centres worldwide, making it feasible for implementation in routine clinical practice. The iBox risk prediction system assessed the risk at a given time point, but we have shown that it can be re-evaluated at different time points after transplantation, enabling clinicians to calculate a new risk that takes into account the updated values of eGFR, proteinuria, allograft scarring, allograft inflammation, damage, and presence and concentration of anti-HLA DSA. Therefore, we confirmed the iBox system’s transportability for additional and updated evaluations in the patient’s long term course. To account for different potential medico-economic contexts limiting the availability of allograft biopsies, we also provide an abbreviated iBox score based on clinical-functional- immunological parameters.

Comparison with other prognostic scores

Current prognostic scores implemented in clinical practice in transplant medicine mostly predict allograft survival at the time of transplantation; thus, their use is limited to allograft allocation because they do not inform post-transplant clinical decision making and monitoring of patients.27 The few attempts to develop post-transplant prognostic scores have failed to provide useful tools for transplant clinicians. According to a systematic review without date restrictions for publications up to 28 September 2018, for allograft survival scoring systems among kidney transplant recipients (see supplementary table G), no study has developed and externally validated a post-transplant prognostic score usable at any time after transplantation that shows accuracy in clinical trials. The main limitations to achieving a robust and validated scoring system depend on multiple factors including the insufficient data quality of the previously studied cohorts and the fact that no registry or database system has been primarily designed to tackle the specific aspect of prognostication. An even more important aspect is external validation in different populations, which prompted us to conduct a large external validation in multiple centres worldwide. Despite some expected loss of discriminative performance, models are typically considered useful for clinical decision making when the C statistic is greater than 0.70 and strong when the C statistic exceeds 0.80, suggesting that the iBox risk prediction score could support decision making.28 For prognostication systems in other fields such as oncology (for example, locally advanced pancreatic cancer and metastatic colonic cancer), the C index is typically closer to 0.60 or 0.70.29 Taken together, these results confirm not only the robustness and validity of the iBox risk prediction score but also its generalisability to other transplant cohorts with different kidney allocation systems, donor and recipient profiles, and distinct patient management and healthcare environments.

Strengths of study

In this study, we have shown that the iBox risk prediction score outperformed the current gold standard (eGFR and proteinuria) for the monitoring of kidney recipients. In particular, compared with previous attempts at developing a prognostication system, we found that allograft histological lesions such as microcirculation inflammation, interstitial inflammation-tubulitis (reflecting active rejection process) and atrophy-fibrosis, and transplant glomerulopathy (reflecting chronic allograft damage), in addition to measuring allograft functional parameters and recipient antibody profiles, improved the overall discrimination capacity of the model and that a multidimensional risk prediction score performs better than its individual components. This risk prediction score reflects the main patterns of allograft deterioration leading to failure, represented by alloimmune processes and allograft scarring.30 Two other prognostic scores have attempted to combine several transplant diagnostic dimensions, including allograft function and pathology and alloantibodies; however, these scores were outperformed by the iBox risk prediction score.16 31

Importantly, our results and the parameters included in the final model reinforce the potential of the iBox to be implemented into contemporary clinical practice by using automated approaches within electronic medical record systems (an online electronic risk calculator is provided at http://www.paristransplantgroup.org, and examples are provided in supplementary figure B).

In addition, the combination of major drivers of allograft failure in the iBox risk prediction score allowed us to evaluate the early effect of clinical interventions on long term allograft outcomes. In this study, we tested and validated the iBox risk prediction score in the setting of therapeutic clinical trials covering different clinical scenarios and showed accurate performance overall. We found that the prediction of allograft failure assessed by the iBox score accurately fits with the actual graft failures observed in these trials at five years after risk evaluation. Importantly, the accuracy of the iBox risk prediction score was conserved regardless of the therapeutic intervention and population in those trials, with accurate performance in the Certitem (NCT01079143) calcineurin inhibitor minimisation trial and in rejection treatment trials (EudraCT 2007-003213-13; NCT01873157).18 19 20 This finding reinforced the potential of the iBox risk prediction score for defining a valid surrogate endpoint. In our study, a well validated, strong, and robust association existed between the surrogate endpoint and the true endpoint, and this association was consistent across different treatment settings. Finally, because the criteria for defining a surrogate endpoint also include the capacity of a surrogate to be modified by therapeutics, we tested the iBox across three prototypic therapeutic interventions and showed that the iBox score was significantly modified by these therapeutic interventions and showed good performance in this setting as well. Thus, the iBox risk prediction score fulfils all the Prentice criteria for a satisfactory surrogate endpoint.17 32

As a development perspective, implementation of patient reported experience data would probably be very relevant in future, so that quality of life predictions can complement those on graft survival, around indicators such as the experience of treatments, the relationship with the transplant doctor, adherence to the therapeutic strategy, engagement, participation in decisions, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and so on. This would imply that other sources of data can be mobilised, from collections made from the patients themselves.

Limitations of study

Regarding the limitations of this study, we acknowledge that statistical significance as a criterion to select variables may not be ideal as it may exclude confounding factors. However, the multiple external validations performed consistently confirm the robustness of our final model. Emerging predictors post-transplant might be also missing in our model. Despite the already high performance achieved by the iBox risk prediction score, future studies should evaluate the added value of new non-invasive biomarkers or genetic factors in addition to those currently reported regarding discriminative capability, generalizability, and overcoming the need for an invasive procedure (kidney allograft biopsy). Although intragraft gene measurements may improve diagnostic accuracy in T cell mediated rejection and antibody mediated rejection, their additive value for allograft survival compared with classical prognostic factors has not yet been demonstrated in large unselected populations.

Another limitation is that information on the adherence to drug treatment of individual patients was lacking in our dataset. Although non-adherence is inherently difficult to capture, especially at a population level,30 the iBox score, because its mechanistically informed design could likely capture the consequences of non-adherence (development of de novo donor specific anti-HLA antibodies, allograft injury, scarring, inflammation, and diminished glomerular filtration rate).

Although the iBox risk prediction score was primarily generated using a large, prospective, unselected cohort, a prospective validation of the iBox in daily clinical practice remains desirable. Finally, despite the validation of the iBox risk prediction score in an interventional setting, future trials are needed to determine whether a strategy based on a systematic risk evaluation compared with an empirical approach might improve clinical management.

Conclusions

We have developed and validated a risk prediction score that accurately predicts allograft failure after kidney transplantation. We have shown its generalisability and transportability across centres in Europe and the US and its performance in therapeutic clinical trials. The risk prediction score provides an accurate but simple strategy that can be easily implemented to stratify patients into clinically meaningful risk groups and that can be time updated after transplant, which may help to guide monitoring of patients in everyday practice and upgrade the shared decision making process. Lastly, as the risk score fulfils the Prentice criteria, it may represent a valid surrogate endpoint that could open avenues for improving the design of clinical trials and development of drugs in transplantation.

What is already known on this topic

The transplant field lacks robust studies specifically designed for prediction of risk of long term allograft failure

Existing studies do not integrate a large spectrum of prognostic factors and validate scoring systems in multiple large cohorts worldwide with different transplant allocation systems

This represents a serious limitation for further improving patient care and drug development

What this study adds

This is the first international study of risk prediction in kidney transplant recipients, developed and validated across several large independent populations and in randomised controlled clinical trials

The iBox score represents a novel integration of demographic, functional, histological, and immunological factors that can be implemented in routine clinical practice

It has potential to upgrade the shared decision making process for transplant patients and represents a valid and early surrogate endpoint for clinical trials and drug development in transplantation

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants who made this study possible, the advocacy groups that participated in evaluating the iBox, and the two patients’ associations Renaloo and France REIN which gave feedback on the applications of the risk score system and its translation to patient care. We plan to share the results to the wider community and our participants.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary materials

Contributors: AL and OA designed the study, did the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. BO, MN, AMJ, DV, CLegendre, MG, NK, OT, EM, MD, DK, AH, ER, EB, FE, GB, GD, MR, GG, DG, JPE, XJ, RAM, MDS, DLS, and CLefaucheur contributed to data acquisition and interpretation. AL, OA, BO, MN, YB, DV, DLS, DG, CLegendre, JPE, and XJ interpreted the data. BO, MN, and YB participated in data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. AL, OA, BO, and MN contributed equally as first authors. XJ, DLS, and CLefaucheur contributed equally as last authors. AL is the guarantor.

Funding: INSERM–Action thématique incitative sur programme Avenir (ATIP-Avenir) provided financial support; OA received a grant from the Fondation Bettencourt Schueller; MN received grants from the Research Foundation, Flanders (FWO; IWT.150199), the Flanders Innovation and Entrepreneurship of the Flemish government (IWT.130758), and the Clinical Research Foundation of the University Hospitals Leuven.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: support as detailed above for the submitted work; AL holds shares in Cibiltech, a company that develops software; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Each patient from the Paris Transplant Group cohort provided written informed consent to be included in the Paris Transplant Group database. This database has been approved by the National French Commission for Bioinformatics, Data, and Patient Liberty: CNIL registration number: 363505, validated 3 April 1996. The institutional review boards of the Paris Transplant Group participating centres approved the study.

Data sharing: Technical appendix is available from the corresponding author at alexandreloupy@gmail.com.

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript's guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1. Mills KT, Xu Y, Zhang W, et al. A systematic analysis of worldwide population-based data on the global burden of chronic kidney disease in 2010. Kidney Int 2015;88:950-7. 10.1038/ki.2015.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, et al. Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158765. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Evans RW, Manninen DL, Garrison LP, Jr, et al. The quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med 1985;312:553-9. 10.1056/NEJM198502283120905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Kaplan B. Lack of improvement in renal allograft survival despite a marked decrease in acute rejection rates over the most recent era. Am J Transplant 2004;4:378-83. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coemans M, Süsal C, Döhler B, et al. Analyses of the short- and long-term graft survival after kidney transplantation in Europe between 1986 and 2015. Kidney Int 2018;94:964-73. 10.1016/j.kint.2018.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perl J. Kidney transplant failure: failing kidneys, failing care? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;9:1153-5. 10.2215/CJN.04670514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stegall MD, Morris RE, Alloway RR, Mannon RB. Developing New Immunosuppression for the Next Generation of Transplant Recipients: The Path Forward. Am J Transplant 2016;16:1094-101. 10.1111/ajt.13582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vincenti F, Rostaing L, Grinyo J, et al. Belatacept and Long-Term Outcomes in Kidney Transplantation. N Engl J Med 2016;374:333-43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1506027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaplan B, Schold J, Meier-Kriesche HU. Poor predictive value of serum creatinine for renal allograft loss. Am J Transplant 2003;3:1560-5. 10.1046/j.1600-6135.2003.00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. He X, Moore J, Shabir S, et al. Comparison of the predictive performance of eGFR formulae for mortality and graft failure in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 2009;87:384-92. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819004a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Naesens M, Lerut E, Emonds MP, et al. Proteinuria as a Noninvasive Marker for Renal Allograft Histology and Failure: An Observational Cohort Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;27:281-92. 10.1681/ASN.2015010062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yilmaz S, Tomlanovich S, Mathew T, et al. Protocol core needle biopsy and histologic Chronic Allograft Damage Index (CADI) as surrogate end point for long-term graft survival in multicenter studies. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:773-9. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000054496.68498.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lefaucheur C, Loupy A, Hill GS, et al. Preexisting donor-specific HLA antibodies predict outcome in kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;21:1398-406. 10.1681/ASN.2009101065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moore J, He X, Shabir S, et al. Development and evaluation of a composite risk score to predict kidney transplant failure. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;57:744-51. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shabir S, Halimi JM, Cherukuri A, et al. Predicting 5-year risk of kidney transplant failure: a prediction instrument using data available at 1 year posttransplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;63:643-51. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gonzales MM, Bentall A, Kremers WK, Stegall MD, Borrows R. Predicting Individual Renal Allograft Outcomes Using Risk Models with 1-Year Surveillance Biopsy and Alloantibody Data. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;27:3165-74. 10.1681/ASN.2015070811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schold JD, Kaplan B. The elephant in the room: failings of current clinical endpoints in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 2010;10:1163-6. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eskandary F, Regele H, Baumann L, et al. A Randomized Trial of Bortezomib in Late Antibody-Mediated Kidney Transplant Rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;29:591-605. 10.1681/ASN.2017070818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sautenet B, Blancho G, Büchler M, et al. One-year Results of the Effects of Rituximab on Acute Antibody-Mediated Rejection in Renal Transplantation: RITUX ERAH, a Multicenter Double-blind Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial. Transplantation 2016;100:391-9. 10.1097/TP.0000000000000958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rostaing L, Hertig A, Albano L, et al. CERTITEM Study Group Fibrosis progression according to epithelial-mesenchymal transition profile: a randomized trial of everolimus versus CsA. Am J Transplant 2015;15:1303-12. 10.1111/ajt.13132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:55-63. 10.7326/M14-0697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lamb KE, Lodhi S, Meier-Kriesche HU. Long-term renal allograft survival in the United States: a critical reappraisal. Am J Transplant 2011;11:450-62. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Efron B. Bootstrap Methods: Another Look at the Jackknife. Ann Stat 1979;7:1-26 10.1214/aos/1176344552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med 2011;30:11-21. 10.1002/sim.4085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Uno H, Tian L, Cai T, Kohane IS, Wei LJ. A unified inference procedure for a class of measures to assess improvement in risk prediction systems with survival data. Stat Med 2013;32:2430-42. 10.1002/sim.5647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rao PS, Schaubel DE, Guidinger MK, et al. A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: the kidney donor risk index. Transplantation 2009;88:231-6. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ac620b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hosmer DWLS. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed John Wiley & Sons, 2000. 10.1002/0471722146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prasad V, Kim C, Burotto M, Vandross A. The Strength of Association Between Surrogate End Points and Survival in Oncology: A Systematic Review of Trial-Level Meta-analyses. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1389-98. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sellarés J, de Freitas DG, Mengel M, et al. Understanding the causes of kidney transplant failure: the dominant role of antibody-mediated rejection and nonadherence. Am J Transplant 2012;12:388-99. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03840.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prémaud A, Filloux M, Gatault P, et al. An adjustable predictive score of graft survival in kidney transplant patients and the levels of risk linked to de novo donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180236. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Prentice RL. Surrogate endpoints in clinical trials: definition and operational criteria. Stat Med 1989;8:431-40. 10.1002/sim.4780080407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials