Abstract

Building Better Caregivers (BBC) a community 6-week, peer-led intervention targets family caregivers of those with cognitive impairments.

BBC was implemented in four geographically-scattered areas. Self-report data were collected at baseline, 6 months and 1 year. Primary outcome were caregiver strain and depression. Secondary outcomes included caregiver burden, stress, fatigue, pain, sleep, self-rated health, exercise, self-efficacy, caregiver and care partner health-care utilization. Paired t-tests examined 6 month and 1-year improvements. General linear models examined associations between baseline and 6-month changes in self-efficacy and 12-month primary outcomes.

Eighty-three participants (75% of eligible) completed 12-month data. Caregiver strain and depression improved significantly (ES=.30 and .41). All secondary outcomes except exercise and caregiver health-care utilization improved significantly. Baseline and 6-month improvements in self-efficacy were associated with improvements in caregiver strain and depression. In this pilot pragmatic study BBC appears to assist caregivers while reducing care partner health-care utilization. Self-efficacy appears to moderate these outcomes.

Keywords: caregivers of cognitively-impaired adults, self-management, depression, caregiver strain, self-efficacy

Introduction

There are more than 10 million family caregivers in the United States caring for people with cognitive impairments (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Caregivers often have high stress and poor health (van der Lee, Bakker, Duivenvoorden, & Dröes, 2014; Schulz & Beach, 1999). In 2012, the Roslyn Carter Center for Caregiving (2012) made recommendations, including that:

Caregivers receive evidence-based, effective support services targeting their identified needs.

These programs be translated into community settings.

Relevant to the first recommendation, reviews by Chesla (2010) and Corry, White, Neeman, and Smith (2015) have determined that many caregiver programs are efficacious. However, the clear majority are designed for specific sub-groups defined by specific cognitive-impairment causing conditions. Many target caregivers of patients with dementia (Akkerman & Ostwald, 2004; Beauchamp, Irvine, Seeley, & Johnson, 2005; Belle et al., 2006; Blom, Zarit, Zwaaftink, Cuijpers, & Pot, 2015; Coon, Thompson, Steffen, Sorocco, & Gallagher-Thompson, 2003; Eisdorfer et al., 2003; Mittelman & Bartels, 2014; Mittelman et al., 1995; Mittelman, Roth, Haley, & Zarit, 2004) or stroke (Clark, Rubenach, & Winsor, 2002; Grant, Elliott, Weaver, Bartolucci, & Giger, 2002). Despite similarities in caregiving experiences and challenges, few programs are designed to encompass caregivers across cognitive-limiting conditions.

Gitlin, Marx, Stanley, and Hodgson (2015) summarize the translation evidence for dementia caregiving interventions. Only six interventions translated into wider practice were found. The authors identified several knowledge gaps: 1) differences between study subjects and the population of caregivers, limiting generalizability, 2) limited evidence about the efficacy of translated programs, 3) limited information about outcomes important to stakeholders, such as utilization, and 4) limited information about the duration of effects.

The current paper addresses these gaps (including lack of interventions for caregivers of those with varying cognitive conditions and lack of translatability) by examining the effectiveness of a small-group, community-based, peer-led intervention, Building Better Caregivers (BBC), as implemented in a pragmatic multi-site trial. This intervention was previously studied in an online version designed for the caregivers of veterans with cognitive impairment. That trial demonstrated improved caregiver outcomes (Lorig, et al., 2012). While the internet reaches many caregivers, other caregivers either do not have internet access or prefer small–group, in-person learning. We chose to target caregivers of those with all cognitive conditions because of previous experience and because the problems of these caregivers are similar. We chose to conduct a pragmatic trial of an in-person, peer-led program. The strength of a pragmatic trial is that it “maximizes the applicability of the trial’s results to usual care settings” (Zwarenstein et al., 2008). The pragmatic design addresses specific knowledge gaps: 1) study subjects represented the greater population of caregivers, 2) outcomes included those important to caregivers and community stakeholders, and 3) participants were followed for one year, assuring duration of effects.

Hypotheses:

Participants would demonstrate one-year improvements in health status (primary outcomes: caregiver strain and depression), health behaviors, health-care utilization and self-efficacy.

Care partners (this term for the persons being cared for was suggested by a survey of caregivers) would experience reduced health-care utilization.

Baseline and six-month changes in self-efficacy would be associated with primary outcomes.

Primary outcomes would not differ by setting.

Methods

Design

We chose a one-year pragmatic, longitudinal design that allowed study of real-world effectiveness (Lorig, et al., 2012; Thorpe et al., 2009) Data were collected at baseline, six and 12 months. There were few inclusion or exclusion criteria.

Conceptual framework and rationale

Several conceptual frameworks inform this study: 1) self-management, 2) self-efficacy, 3) caregiver stress and coping, and 4) social support.

Self-Management is defined as the tasks that individuals must undertake to live with chronic conditions. These tasks include having confidence to deal with the medical management, role management and emotional management of their conditions (Corrigan, Greiner, & Adams, 2004). Caregiving, like chronic illness self-management, takes places largely outside of professional settings and is more complex. Caregivers deal with their own and their partner’s medical, role and emotional management.

Confidence to undertake a new task is a key self-management component. We operationalized confidence as self-efficacy which was first discussed by Bandura (1997) and has been linked to behavior change and task completion. Bandura suggests four means to increase self-efficacy: skills mastery, modeling, reinterpretation of circumstances, and social persuasion. These were systematically applied during the intervention. Coon et al. (2003) found that self-efficacy was a mediator of caregiver improvement in anger management and depression.

Stress is the third component of the conceptual framework. Thirty years ago, Montgomery Gonyea and Hooyman (1985) identified that stress is caused by personal, interpersonal and cognitive factors. Personal factors include disruption of normal life and financial burden. Interpersonal factors include role change and conflict with one’s care partner, as well as loss of meaningful relationships. Stress is largely internal and revolves around the caregiver’s interpretation and meaning of the caregiving experience and their ability to undertake this new roll. Collectively, these stressors have been termed caregiver burden (Zarit, Reever, & Bach-Peterson, 1980). Because stress is a key caregiver concern, BBC is centered around breaking the stress cycle.

The fourth concern is social support. Thompson, Futterman, Gallagher-Thompson, Rose, and Lovett (1993) identified lack of social participation as strongly related to caregiver burden. Thus, BBC encourages social support by allowing and encouraging participants to learn from and help each other. See table 1 for how each of these are integrated into the intervention.

Table 1.

Building Better Caregivers Workshop Overview

| Topic | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overview of Caregiving & the Workshop Modeling by peer leaders throughout (SE) |

● | |||||

| Signal Breathing * Coping/stress skill |

● | |||||

| Improving Fatigue * Reinterpretation of symptoms (SE) |

● | |||||

| Difficult Care Partner Behaviors * Coping/stress skill Social Support Skills mastery/modeling (SE) |

● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Making an Action Plan * Skills mastery/modeling (SE) Social Support |

● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Feedback / Sharing Skills Mastery (SE) Social Support |

● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Problem-Solving * Stress/Coping Skills Mastery/Modeling (SE) |

● | ● | ||||

| Healthy Eating * | ● | |||||

| Difficult Thoughts & Emotions * Stress /Coping Social support Modeling (SE) |

● | ● | ||||

| Getting a Good Night’s Sleep * Reinterpretation of symptoms (SE) |

● | |||||

| Making Decisions * Stress and Coping Skills Mastery/Modeling SE |

● | |||||

| Physical Activity / Exercise * Stress and Coping |

● | |||||

| Helpful / Unhelpful Thinking * Stress and Coping |

● | ● | ||||

| Getting Help * Stress and coping |

● | ● | ||||

| Medication Usage * Reinterpretation (SE) |

● | |||||

| Future Planning/ Legal Issues * Stress and coping |

● | |||||

| Relaxation * Stress and coping |

● | |||||

| Working with Health Care Systems & Providers * Stress and coping |

● | |||||

| Communication * Stress and coping Modeling (SE) Reinterpretation (SE) |

● | |||||

| Looking Back & Planning for the Future Skills Mastery / modeling/social support (SE) |

● |

Notes:

Items represent self-management skills.

SE activities designed to enhance self-efficacy through skills mastery, modeling, reinterpretation and or persuasion.

Intervention

Building Better Caregivers is a six-week, group workshop taught by two trained peers, who had previously been trained in (four-day training) and facilitated the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP, Lorig et al., 1999). Most of the peer facilitators had caregiving experience, lived in the community where BBC was offered, and were not health professionals. BBC is aimed at enhancing the caregiving skills and reducing stress of both older and younger people caring for those with cognitive impairment. The peer facilitators received an additional 1.5 days of BBC training.

The BBC workshop consists of weekly 2.5-hour sessions. Each session covered several topics and was highly interactive. When constructing the program, we look at several components: 1) content to reduce stress and enhance caregiver skills, 2) activities to enhance self-efficacy and 3) structure to enhance social support. Content can be found in Table 1.

BBC stress reduction content dealt with how to reduce stressful caregiver problems and teaching stress reduction techniques. The skills taught reflect the three distinctive tasks of caregiving self-management: medical management such as medication management and interacting with providers, role management such as how to get help and to accomplish important role tasks while being a caregiver, and emotional management such as dealing with both caregiver and care partner depression and anxiety.

Activities to enhance self-efficacy include 1) Skills Mastery, having participants make weekly action plans and keeping a diary of the difficult care-partner behaviors. Participants gave weekly feedback for these activities. Facilitators handled problems using a standardized problem-solving methodology. The solving of problems also leads to stress reduction. 2) Modeling was demonstrated by peer facilitators and by participants helping each other; the later adds to social support. Cognitive restructuring or reinterpretation of meaning was emphasized throughout the workshop especially when discussing ways of conceptualizing and dealing with care partner problem behaviors. Social support was fostered by having at least one activity per session where participants helped each other and gave feedback to each other. The investigators offered no reinforcement during the 10.5 months after the intervention and the last data collection.

Settings

We invited five organizations which were currently offering other Stanford Self-Management Programs (Lorig, et al., 1999) to participate. 1) Dignity Health hospitals and clinics in Sacramento, California is part of a large two state multi-hospital and clinic system. 2) Aligning Forces Humboldt is a clinic located in Eureka, California serving rural communities within 100 miles. 3) The Health Trust, in San Jose, California, is a foundation serving a diverse ethnic population. 4) Fairhill Partners, in Cleveland, Ohio, is a community-based organization that provides direct and ancillary services to older adults, their caregivers, and others who serve them. A fifth organization, because of unforeseen staff changes, was unable to recruit participants.

Investigators conducted a day and a half of training at each site. All facilitators were current leaders of Stanford Self-Management Programs. The organizations received material for the facilitators and participants as well as $50 for each participant completing four or more sessions. Participants, in keeping with how the program may be used in the real world, were not paid for attending. Each site did their own recruiting, scheduling and fidelity monitoring. The later was done by the site coordinators who in all cases were CDSMP trainers who had attended the BBC training. The usual monitoring consisted of attending random sessions with a predetermined check list. There is also a fidelity manual for all Stanford programs (Stanford Patient Education Research Center, 2016).

Participants

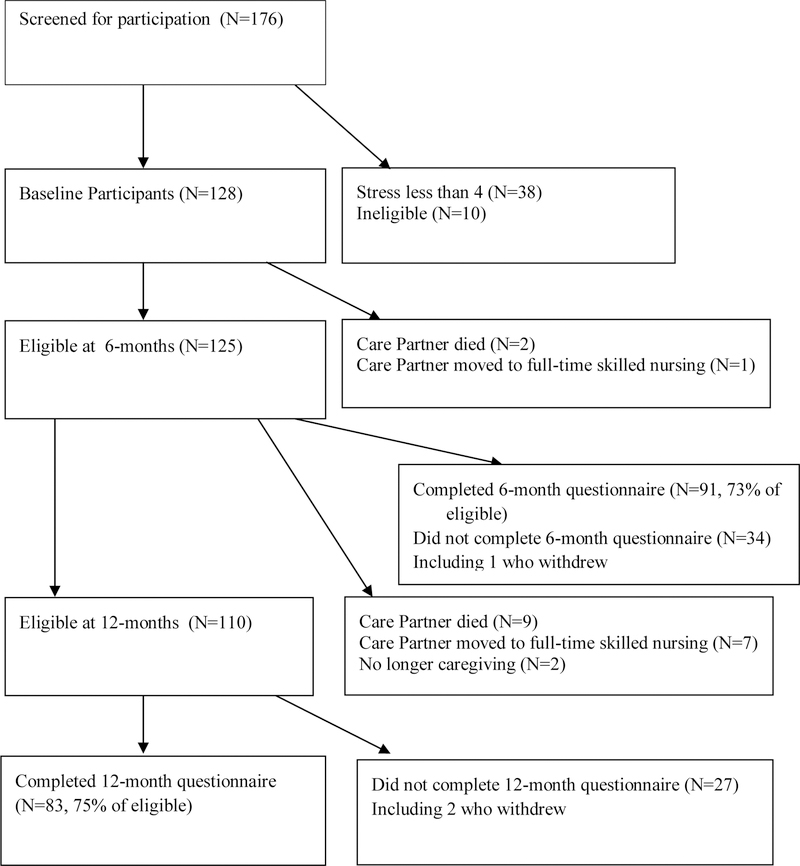

Each organization recruited participants, (caregivers of those with cognitive impairment) in many cases working with local partners such as the Alzheimer’s Association, Veterans Support organizations and Senior Day Health Centers. Recruitment varied by organization but included public service announcements, announcements in media reaching caregivers, and flyers. Because organizations did not want to exclude anyone, any family caregiver could attend. Additional screening was conducted by questionnaire at the first session. If participants met study criteria, they completed an informed consent and baseline questionnaire. To qualify for our study, caregivers needed to provide care 10 or more hours a week, have a care partner with cognitive impairment who was living with or nearby in the community, and have a score of four or more on a 10-point visual-numeric stress scale. These criteria are similar to those in other studies for the caregivers of those with cognitive impairment. Participants could not have taken part in a previous Stanford Self-Management Program. One hundred and seventy-six people attended the first session of who 128 qualified as study participants. As seen in Figure 1, most of those not qualifying for the study did not have the required level of stress. Because of the pragmatic nature of the study, people not qualifying for the study continued in the workshops but were not considered study subjects. The study was approved by the Stanford IRB. At the 12-month follow-up questionnaire, the investigators removed an additional 18 participants from the study because they were no longer caregivers (partner died or moved to a residential facility, etc.). See Figure 1. Of the 128 original study subjects 110 were still caregivers at 12 months and qualified for 12-month data collection. Seventy-five percent of these supplied 12-month data. Figure 1 also shows that participation was similar at the time of the six-month questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Participants

Data Collection and Measures

Using self-administered questionnaires, data were collected at pre-workshop orientation sessions or at the first workshop session by local program staff members who had completed CITI training as well as training on how to follow the data collection protocol. After collection, the questionnaires were mailed to Stanford. The Investigators mailed all subsequent questionnaires directly to participants. Caregiver strain and depression were the primary outcomes. The Caregiver Strain Index (CSI) measures caregiver strain and stress (Robinson, 1983) and consists of the sum of 13 items and ranges from 0–13. The CSI has a reliability coefficient of alpha = .82 in the earlier online BBC study. Depression was measured by the PHQ-8 scale (Kroenke et al., 2009). That eight-item scale had a reliability of alpha = .89 in the earlier BBC study. Secondary outcomes included Self-Rated Health, which was measured with a single-item scale from the National Health Interview Survey (United States Department of Commerce, 1985). Visual-numeric scales measured pain, shortness of breath, stress, problems sleeping, and fatigue. Visual-numeric scales have been shown to correlate well (r = .72) with same-worded visual-analogue scales and had a better completion rate (Ritter, González, Laurent, & Lorig, 2006). The Zarit Burden Inventory (ZBI) measured caregiver burden (Parks, & Novielli, 2000). It consists of mean of 12 items and has a range of 0 to 4. The reliability coefficient in the online BBC study was .90.

Aerobic exercise was measured as the number of minutes of self-reported exercise in the last week (Lorig, et al., 1996). Exercise is a health behavior benefiting caregivers as well as a means of reducing stress. For both caregiver and care partner we measured utilization: caregiver report of physician visits, hospital emergency department visits and number of nights in a hospital. In a previous study, self-report of outpatient visits correlated r = .70 with chart audit data, and days in the hospital correlated r = .83 (Ritter, et al., 2001). We used a nine-question version of a Caregiving Self-Efficacy scale adapted from a scale developed and validated by Steffen et al. (2002). The nine items addressed the workshop content and had reliability of alpha = .89.

In addition to demographic variables (age, gender, marital status), we also asked participants the number of hours they cared for their care partners per week, number of days care partner spent in skilled nursing and/or assisted living in the last six-months, whether participants worked or changed work status, and the relationship between care partner and caregiver.

Data Analysis

To ascertain attrition bias, we compare baseline characteristics of those who completed 12-month questionnaires with those who did not. Independent-sample t-tests were used to compare 12-month completers with non-completers.

Paired t-tests tested whether changes over 12 months for caregiver primary and secondary outcomes were significantly different from zero (hypothesis 1). Similarly paired t-tests were used to examine 12-month changes in care partner health-care utilization (hypothesis 2).

Although the focus of this study was on 12-month outcomes, we also examined six-month outcomes using the same methodology. This allows comparison of six-month and 12-month changes to determine if improvements that may have occurred soon after the intervention were maintained, increased or lessened over one year.

The relationship between baseline and six-month change in self-efficacy and 12-month change in primary outcomes (hypothesis 3) were tested using general linear regression models including demographic variables, the baseline measure of the outcome score, and both baseline self-efficacy and 6-month change in self-efficacy. The dependent variables were the primary outcomes: 12-month change in Caregiver Strain Index and PHQ-8 depression scale.

Differences among organizations (hypothesis 4) were tested using general linear models analysis of covariance. Organization was included in models with baseline measures of the outcome variable (caregiver strain or depression) and demographic variables as covariates.

Results

Participation

Fifteen workshops were attended by 176 caregivers (range = 7–15). Mean attendance was 4.6 out of 6 sessions (SD = 1.7, range 1–6) with 82% attended 4 or more sessions. Of the 176, 168 were potentially eligible for the study and completed baseline questionnaires. Forty were later found to have been ineligible (two had less than 10 hours of caregiving per week and 38 had a stress level less than 4), resulting in 128 initial study participants (Figure 1). The 128 study participants also attended a mean of 4.6 workshops (SD=1.7) with 78.1% attending 4 or more sessions and 45% attending all six workshops.

At 12-month follow-up, 18 participants were no longer caregivers, (Figure 1), making the final number of those eligible for the study equal to 110. Of these, two withdrew from the study and 83 (75%) completed 12-month questionnaires.

Baseline Characteristics

Table 2 includes caregiver and care partner demographics for the 128 baseline participants, broken down by those who completed 12-month questionnaires and those who did not. The most frequent care relationship was a female spouse or partner taking care of a male partner. This was followed by children caring for a parent or parent-in-law. Care partners were typically elderly. The mean age for completers was nearly 77, while care partners for non-completers had a mean age of 82. This difference partly reflects that non-completers include participants whose care partner was deceased at one-year or in full-time care, and the likelihood of this happening increases with age. Caregivers were typically in their sixties.

TABLE 2.

Caregiver and Care Partner Baseline Characteristics (N = 128)

| VARIABLE | 12-month Completers (N=83) |

12-month Non-completers (N=45) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver | |||

| Age of Caregiver (range 41 to 86) | 65.5 (9.3) | 63.8 (10.9) | .311 |

| Percent Caregiver Male | 13.2% | 13.3% | .990 |

| Caregiver Ethnicity | |||

| Percent Non-Hispanic White | 73.5% | 70.5% | .715 |

| Percent Hispanic | 7.2% | 0.0% | .013 |

| Percent Asian | 4.7% | 5.5% | .052 |

| Percent Black | 11.4% | 7.8% | .515 |

| Percent Care Partner a spouse or domestic partner | 53.0% | 39.5% | .167 |

| Percent Care Partner a Parent or Parent-in-law | 33.7% | 52.6% | .049 |

| Percent Caregiver Married | 71.1% | 64.4% | .443 |

| Percent Caregiver Changed Work Because of Caregiving (previously working) | 64.6% | 52.2% | .317 |

| Percent Caregiver Worked for Pay (part or full time) last 6 months | 39.8% | 34.2% | .560 |

| Hours per week spent taking care of Care Partner | 68.6 (56.4) | 54.5 (50.2) | .165 |

| Days care partner spent in skilled nursing or assisted living (last six months) | 11.8 (39.2) | 25.1 (53.9) | <.001 |

|

Care Partner | |||

| Age of Care Partner (range 28 to 92) | 76.8 (13.3) | 82.1 (10.4) | .022 |

| Percent Care Partner Male | 62.7% | 62.2% | .962 |

| Percent Care Partner Lives with Caregiver | 71.1% | 55.3% | .088 |

| Percent Care Partner Veteran | 22.9% | 45.5% | .009 |

Notes: P-values are from t-tests (means) or chi-square (percentages) indicating the probability of no difference between 12-month completers and non-completers. Standard Deviations are given in parentheses for means. Non-completers include those no longer caretaking at twelve months.

Characteristics of those completing vs. not completing 12-month questionnaires

Comparing baseline primary and secondary outcomes for 12-month completers versus those who did not complete 12-month questionnaires, there were no significant differences (Table 3). Comparing baseline demographic and partner characteristics, there were four statistically significant differences (Table 2). Those who returned 12-month questionnaires were more likely to be Hispanic (p = .01), had, as noted above, younger care partners (mean age 77 versus 82, p = .02), less likely to be caring for a parent or parent-in-law (p = .05) and had care partners less likely to be veterans (p = .01). The number of sessions attended (out of six) was not strongly correlated with completing 12-month questionnaires (r = .126, p = .157). Those who did not complete 12-month questionnaires also had care partners with significantly more nights with professional care (skilled nursing or assisted living, p < .001)

Table 3.

Caregiver and Care Partner Baseline Means for Outcome Variables

| Measure | 12-month Completers (N=83) |

12-month Non-completers (N=45) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver outcomes primary | |||

| Caregiver strain index (0–13) ↓ | 9.30 (2.60) | 9.20 (2.66) | .835 |

| Depression (0–27) ↓ | 8.40 (5.14) | 8.91 (5.28) | .594 |

|

Caregiver outcomes secondary | |||

| Caregiving burden (0–4)↓ | 1.94 (0.878) | 1.93 (0.745) | .938 |

| Fatigue (0–10) ↓ | 6.05 (2.25) | 5.98 (2.36) | .868 |

| Pain (0–10) ↓ | 4.30 (2.64) | 3.82 (2.99) | .352 |

| Stress (0–10) ↓ | 7.22 (1.99) | 7.16 (1.87) | .865 |

| Sleep (0–10) ↓ | 5.43 (2.99) | 4.71 (3.07) | .388 |

| Self-rated health (0–5) ↓ | 2.61 (0.961) | 2.56 (0.841) | .730 |

| Aerobic exercise (min/week) ↑ | 154 (152) | 146 (97.3) | .776 |

| Self-efficacy (1–10) ↑ | 5.36 (1.84) | 5.41 (1.86) | .874 |

| MD visits | 2.61 (2.75) | 1.87 (2.24) | .121 |

| Emergency department (ED) visits | 0.157 (0.398) | 0.089 (0.288) | .316 |

| Hospital nights | −0.409 (3.62) | 0.0 (0.0) | .306 |

|

Care partner outcomes | |||

| MD visits | 6.31 (5.92) | 4.80 (4.60) | .142 |

| ED visits | 0.530 (0.928) | 0.318 (0.708) | .188 |

| Hospital nights | 2.23 (7.59) | 1.47 (4.39) | .473 |

Notes: P-values are from t-tests indicating the probability of no difference between 12-month completers and non-completers. Standard Deviations are given in parentheses for means. Non-completers include those no longer caretaking at twelve months.

Six-month changes

Table 4 shows six-month changes in primary and secondary outcomes. Both primary outcomes and 5 secondary outcomes had statistically significant improvements among the 91 participants who continued in the study and completed six-month questionnaires. These data are included for comparison purposes, since the focus of this study is on the 12-month outcomes.

Table 4.

Six-month change, N=91

| Measure | Baseline Mean (SD) | Mean 6-month Change (SD) | Effect Size of Change | P > t for Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver outcomes primary | ||||

| Caregiver strain index (0–13) ↓ | 9.11 (2.60) | −0.467 (2.17) | 0.180 | .045 |

| Depression (0–27) ↓ | 8.14 (5.01) | −1.92 (4.77) | 0.383 | <.001 |

|

Caregiver outcomes secondary | ||||

| Caregiving burden (0–4)↓ | 1.96 (0.718) | −0.242 (0.481) | 0.201 | <.001 |

| Fatigue (0–10) ↓ | 6.04 (2.36) | −0.582 (2.46) | 0.247 | .026 |

| Pain (0–10) ↓ | 4.24 (2.79) | −0.418 (2.51) | 0.150 | .116 |

| Stress (0–10) ↓ | 7.27 (1.94) | −0.912 (2.50) | 0.470 | <.001 |

| Sleep (0–10) ↓ | 5.02 (3.04) | −0.604 (3.14) | 0.199 | .070 |

| Self-rated health (0–5) ↓ | 2.62 (0.940) | 0.154 (0.698) | 0.164 | .038 |

| Aerobic exercise (min/week) ↑ | 146 (152) | 5.60 (138) | 0.037 | .701 |

| Self-efficacy (1–10) ↑ | 5.38 (1.77) | 0.954 (1.61) | 0.539 | <.001 |

| MD visits | 2.57 (2.65) | −0.116 (2.87) | 0.044 | .560 |

| Emergency department (ED) visits | 0.143 (0.382) | −0.022 (0.497) | 0.058 | .672 |

| Hospital nights | 0.374 (3.46) | −0.308 (3.26) | 0.009 | .371 |

|

Care partner outcomes | ||||

| MD visits | 5.86 (5.55) | −0.989 (5.12) | 0.178 | .074 |

| ED visits | 0.429 (0.805) | −0.046 (0.875) | 0.057 | .625 |

| Hospital nights | 1.98 (7.18) | −1.04 (7.40) | 0.145 | .184 |

Notes:

indicates that a lower score is desirable (e.g. less stress);

indicates that a higher score is desirables.

Possible ranges of scales are shown next to measure names. Italics for effect sizes indicate that change worsened.

Twelve-month changes

Both primary outcomes (Caregiver Strain Index and PHQ-8 depression scale) improved significantly (effect size = 0.3 and 0.4, p = .008 and I > .001, respectively) (hypothesis 1, see Table 5). All secondary measures improved significantly (effect size = 0.22–0.38) with the exceptions of exercise and self-rated health. In particular, the visual-numeric stress measure improved (effect size = 0.56, p > .001), as did the Zarit caregiver burden inventory (effect size = 0.27, p = .001). Self-efficacy also improved significantly (effect size = 0.56, p >.001).

Table 5.

Baseline and 12-Month Change Scores (N=83)

| Measure | Baseline Mean (SD) | Mean 12-month Change (SD) | Effect-Size of Change | P > t (Intent to Treat, N=128) | P > t (N=83) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver outcomes primary | |||||

| Caregiver strain index (0–13) ↓ | 9.30 (2.60) | −0.768 (2.57) | 0.296 | .009 | .008 |

| Depression (0–27) ↓ | 8.40 (5.14) | −2.11 (4.99) | 0.411 | <.001 | <.001 |

|

Caregiver outcomes secondary | |||||

| Caregiving burden (0–4)↓ | 1.95 (0.778) | −0.276 (0.540) | 0.274 | <.001 | .001 |

| Fatigue (0–10) ↓ | 6.05 (2.25) | −0.87 (2.70) | 0.387 | .005 | .005 |

| Pain (0–10) ↓ | 4.30 (2.64) | −0.639 (2.10) | 0.242 | .007 | .007 |

| Stress (0–10) ↓ | 7.22 (1.99) | −1.12 (2.68) | 0.563 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Sleep (0–10) ↓ | 5.43 (2.99) | −0.663 (2.94) | 0.222 | .044 | .044 |

| Self-rated health (0–5) ↓ | 2.61 (0.961) | 0.183 (0.862) | 0.190 | .056 | .058 |

| Aerobic exercise (min/week) ↑ | 154 (152) | −11.6 (127) | 0.075 | .407 | .408 |

| Self-efficacy (1–10) ↑ | 5.36 (1.84) | 1.04 (1.72) | 0.565 | <.001 | <.001 |

| MD visits | 2.61 (2.75) | −0.253 (2.34) | 0.092 | .328 | .328 |

| Emergency depart. (ED) visits | 0.157 (0.398) | 0.012 (0.707) | 0.030 | .877 | .877 |

| Hospital nights | 0.409 (3.62) | −0.337 (3.42) | 0.093 | .371 | .372 |

|

Care partner outcomes | |||||

| MD visits | 6.313 (5.92) | −2.14 (5.71) | 0.361 | .001 | .001 |

| ED visits | 0.533 (0.928) | −0.289 (0.931) | 0.311 | .006 | .006 |

| Hospital nights | 2.23 (7.59) | −1.12 (7.71) | 0.142 | .189 | .189 |

Notes:

indicates that a lower score is desirable (e.g. less stress);

indicates that a higher score is desirables.

Possible ranges of scales are shown next to measure names. Italics for effect sizes indicate that change worsened. Intent-to-treat p-values assume no change for those not completing 12-month questionnaires.

When we applied a conservative Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons for the two primary outcomes (using a .025 significance criteria rather than .05), both primary remain statistically significant. Four rather than seven secondary measures remain significantly improved using an adjusted p-value of .005 (for 11 caregiver secondary outcome measures).

Caregiver health care utilization did not change significantly. Care partners had significantly fewer physician visits (−2.1 visits) and emergency department visits (−0.29 visits), while nights in hospital did not change significantly (hypothesis 2).

Because help with care giving may influence outcome, we examined the effects of residential care days on outcomes. At baseline, there were 12 care partners who had any days in skilled nursing care or assisted living in the past six months (mean number of days =39.2, SD = 58.7). Five of the 12 had 60 days or more. At 12 months, there were 13 care partners who had any days of living in skilled nursing or assisted care in the past six months, (mean = 58.8 days, SD = 55.3). Of these, five had 60 days or more. If we remove the five who had more than 60 days living in professional care at 12 months from the analyses, all outcomes that were significantly improved with all 83 cases were still significantly improved at 12 months.

We also examined whether there was a relationship between session attendance and 12-month primary outcomes. Correlations between number of session attended and both Caregiver Strain Index and PHQ-8 depression where very low (r = −.04 and −.04, respectively), and not significant. Similarly, t-tests comparing those who completed at least 4 seesions with those who completed less were not significant for the two primary outcomes at 12 months (t = 0.867 and 0.729 for Caregiver Strain Index and PHQ-8 depression, respectively).

Table 5 also included p-values for intent-to-treat analyses. All 128 baseline participants are included and, as is customary, it is assumed that non-completers would not have improved at the same level as participants. Those who did not answer 12-month questionnaires, or who were no longer caregivers were given change score values of 0. As can be seen in the table, the p-values are virtually unchanged from the 83 participants who completed 12-month follow-ups.

Self-efficacy as an outcome mediator or moderator (hypothesis 3)

Self-efficacy improved significantly at both six and 12 months. Using general linear models, both baseline self-efficacy and six-month change in self-efficacy were significantly associated with 12-month improvements in both primary outcomes (caregiver strain and depression, see Table 6). For linear models estimating Caregiver Strain Index, p values were .007 and <.001 for baseline and six-month change in self-efficacy (partial r-squares = .077 and .021, respectively). For PHQ depression, p values were .015 and .019, with partial r-square of .040 and .063, for baseline and 6-month change in self-efficacy. None of the demographic variables were associated with 12-month change scores.

Table 6.

General Linear Models estimating Primary 12-month Outcome Variables

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable Caregiver Strain Index |

Independent Variable PHQ-8 Depression |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-value | P > F | F-value | P > F | |

| Baseline of independent Variable | 20.75 | < .001 | 33.29 | < .001 |

| Male (gender) | 0.09 | .764 | 0.25 | .617 |

| Married | 0.04 | .840 | 0.23 | .635 |

| Age of caregiver | 1.81 | .184 | 0.17 | .678 |

| Non-Hispanic White Ethnicity | 1.49 | .226 | 0.34 | .561 |

| Baseline Self-efficacy | 7.70 | .007 | 6.31 | .015 |

| Six-month change in self-efficacy | 12.9 | < .001 | 5.77 | .019 |

| Model r-square | 0.365 | 0.392 | ||

| Model F Value | 5.18 | 5.90 | ||

Differences among organizations (hypothesis 4)

In general linear models analyses of covariance to determine if there were differences by organization, covariates included baseline value of the outcome, age, gender, whether married and whether non-Hispanic white (Table 7). The organization was not significantly associated with either 12-month primary outcome (caregiver strain or depression). Removing the demographic variables did not change the results (all p > .15 for organization).

Table 7.

General Linear Models ANCOVA estimating Primary 12-month Outcome Variables

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable Caregiver Strain Index |

Independent Variable PHQ-8 Depression |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-value | P > F | F-value | P > F | |

| Baseline of independent Variable | 18.48 | < .001 | 27.13 | < .001 |

| Male (gender) | 0.13 | .715 | 0.03 | .869 |

| Married | 0.49 | .488 | 2.64 | .108 |

| Age of caregiver | 4.49 | .037 | 1.42 | .238 |

| Non-Hispanic White Ethnicity | 0.00 | .979 | 3.17 | .079 |

| Organization (Site) | 0.46 | .710 | 1.04 | .380 |

| Model r-square | 0.321 | 0.334 | ||

| Model F Value | 4.37 | 4.70 | ||

Comparison of six-month with twelve-month results

When we compare the results for six months with those for twelve months, for both primary outcomes the effect sizes were slightly lower at six months. Similarly effect sizes were slightly less for each of the significantly improved secondary outcomes. The secondary variables that improved significantly at twelve months also improved significantly at six months with the exception of the sleep problems score (p =.070 at six months versus p = .044).

Discussion

In this pragmatic trial, participants sustained improvements in the primary outcomes (caregiver strain and depression) for at least 12 months. Care partners experienced lower MD and emergency department visits, but not hospitalizations. We also found that baseline and six-month changes in self-efficacy were associated with 12-month improvements in caregiver strain and depression and those outcomes did not differ among community organizations. To elucidate our findings, we first place them in the context of prior studies. Second, we examine the study limitations, most importantly, the degree to which temporal trends—rather than the intervention itself—were likely to account for our findings. Third, we discuss advantages of pragmatic studies using the current study as an example.

In contrast to pragmatic trials, randomized trials tend to emphasize design characteristics that strengthen internal validity (by creating more “idealized” study conditions) but may have limited external validity. The weakness of the current design is that it is not a randomized trial and may lack internal validity. The greatest threats to internal validity are probably temporal (the possibility of regression to the mean or caregiver maturation over time) and the possibility that changes may be due to other factors. The majority of prior caregiver interventions used randomized designs and had restrictive inclusion criteria, highly-resourced intervention settings and personnel, and tighter investigator control. To somewhat compensate for lack of a control group we examined past studies for their effectiveness is reducing stress and depression. Schulz et al. (2002), in summarizing dementia caregiver intervention research, found that for depression 17 out of 22 studies had improvements in depression ranging from .75% to 10.5%. The current BBC study showed a 25% decrease in depression. Of the 83 participants, 32 (38.5%) had baseline PHQ-8 scores of 10 or above, generally considered an indication of clinical depression (Kroenke et al., 2009). When we examine change scores for the 32 with baseline indications of depression, the mean improvement in PHQ-8 was −4.97. A decrease of 5 points or more has been used as a general indicator of clinically significant improvement (Wells, Horton, LeadMann, Jacobson, & Boyko, 2013). Standards for clinically significance for stress are more difficult to quantify.

In a review of stroke caregiver interventions, Legg et al. (2012) found only one trial in which stress improve significantly. Gaugler, Reese, and Mittelman (1996) found a one-year reduction in stress compared to controls. We have been unable to find a standard criteria for clinical significance in changes in stress although Schulz et al. (2002) provide some insights. In sum, the outcomes for participants in the current study are equal to or better than the outcomes for participants in most other caregiver studies. This still leaves the possibility controls would have had changes in the same direction and magnitude as treatment subjects.

To explore the possible behaviors of caregiving study controls over time (one month to three years), we examined published caregiver randomized controlled trials to determine the direction of control-group change for our key variables, depression and stress. For depression, we found six dementia caregiving studies where, over one to six months, the depression of controls either did not change or worsened (Beauchamp et al., 2005; Belle et al., 2016; Blom et al., 2015; Coon et al., 2003; Draper et al., 2006; Gitlin et al., 2003). Four other studies were of durations of one year or more and found worsening depression among controls (Eisdorfer et al., 2003; Gaugler et al., 2016; Mittelman et al., 1995; Mittelman et al., 2004). One of these studies demonstrated a consistently worsening of depression in the usual-care group over three years (Gaugler et al., 2016). We were unable to find a single study in which control-group depression improved. Stress (including caregiver strain and burden) was more difficult to assess, as this was less frequently reported. Gitin, Winter, Dennis, Hodgson and Hauck (2010) found that over four months caregiver “upset” increased in controls. In another study (Gitlin, et al., 2008), control-group caregiver burden worsened slightly. Mittelman et al. (1996) found a one-year increase in caregiver control-group stress as did Draper et al. (2007) in a four-month study. These studies suggest that it is unlikely that untreated caregiver controls over time demonstrate improvements in either depression or stress. It also suggests that our findings may be conservative as they were independent of possible deterioration of key variable in controls. While not complete, this review is representative of studies in the field. In sum, the primary BBC outcomes are equal to or better than most other studies in the field and unlikely due to temporal trends. It is also possible that improvements were due to caregivers receiving other help. While we cannot rule this out, we did exclude from the study all caregivers where the care partner had entered residential care or died.

As reported above, for those remaining in the study we examined those with any, less than sixty and more than 60 days of care partner time in residential care. The lack of differences in outcomes when we remove those with 60 or more days in skilled nursing care prior to one year also suggests that it is unlikely that any increases in skilled nursing facility had a significant impact on the outcomes. Since one component of the intervention focused on types of help and asking for help, it may have been that part of the observed improvements were due to caregivers getting help as a direct result of the intervention. This is a matter for future studies.

In the current study, care partners experienced significant decreases in office and emergency room visits and non-significant decrease in hospital nights. Caregivers demonstrated no utilization changes. In a review of interventions for caregivers of stroke survivors that was issued as a joint statement by the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association, Bakas et al. (2014) found several studies with decreases in care partner emergency room visits (Pierce, Steiner, Khder, Govoni, & Horn, 2009), hospital readmissions (Pierce, et al, 2009) and institutionalization (Shyu, Kuo, Chen, & Chen, 2010). Only one of the identified interventions noted a decrease in caregiver utilization, specifically in office visits (Gräsel, Biehler, Schmidt, & Schupp, 2005). Overall, review authors noted that “few studies have examined caregiver service use and more studies are needed.” Our findings of reduction in care partner health care utilization probably make the intervention cost neutral or cost effective. This was not assessed. Unlike most caregiver interventions, BBC is delivered by peer leaders in community settings. This makes it less expensive than many other programs that depend on professional interventionists and/or are delivered one-on-one. A formal evaluation of cost impacts is warranted.

As in previous studies (Cheng & Chan, 2005; Coon, et al., 2003; Lorig et al., 2012; van den Heuvel et al., 2002), caregiver self-efficacy increased significantly and both baseline and six-month changes in self-efficacy were associated with one-year improvements in both strain and depression. This continues to argue for the central role of confidence or self-efficacy in mitigating the deleterious effects of caregiving.

The present study has several limitations. Foremost is the question, addressed in detail above, of whether temporal trends among caregivers could explain findings. Since controls in the randomized controlled trials we found got worse over time, it seems unlikely that temporal factors account for our findings. Another potential limitation is that utilization measures are participant-reported. But for the recall time frames (every 6 months) self-reported health care utilization data on visits and hospitalizations are reliable (Jiang, et al., 2015). We did not collect detailed information about the diagnosis of care partners, relying on the self-identification of care givers as those caring for someone with cognitive impairment. Thus, we cannot analyze whether the program had varying results for caregivers of those with different kinds of impairment. It would have been desirable to have data on care partners’s type of impairment, and future studies should collect this information. We also have limited data on participants who did not complete the 12-month questionnaire. Nonetheless, baseline scores for both primary and secondary outcome measures hardly differed between participants who completed and did not complete the final questionnaires. Two of the four demographic differences that were found can be explained by inclusion of those who care partner had died or gone into professional care. Such partners were more likely to be older and parents of caregivers. Finally, we have no explanation for the apparent lack of association between number of sessions attended and outcomes. A future study focusing on engagement with the program would be desirable.

The focus of this study was on 12-month outcomes. Six-month data are included for comparison and it can be seen that the results at six months were similar but not quite as strong as at twelve months. This suggests that improvements seen immediately after the program continued and even further improved over the next six months. The intent-to-treat outcomes suggest that this would be true even after taking into account the slightly greater attrition (from 91 to 83) at the later period, although a study of the BBC with a randomized control group would be desirable.

Pragmatic trials have external validity. BBC was tested in real-world community organizations, with few exclusion criteria. Settings—rural versus urban, health care system versus community-based organizations—were not controlled by the investigators. Nevertheless the findings of this study should be taken as proof of concept. Additional studies are warranted.

In conclusion, participants in Building Better Caregivers workshops delivered in diverse, real-world community settings achieved significant improvements in caregiver strain and depression that endured for 12 months. Care partners’ healthcare utilization outcomes also improved. Given the positive results of this pragmatic trial, investigators and stakeholders may want to conduct future randomized trials and formal assessments of the cost implications of widespread program adoption and dissemination.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Archstone Foundation, Grant: 14-02-42. Audrey Alonis and Maisoon Ayish at the Stanford Patient Education Research Center assisted with data collection and management. Stephanie FallCreek of Fairhill Partners, Melissa R. Jones of Aligning Forces Humboldt, Erika Zúñiga of The Health Trust and Sydni Aguirre of Dignity Health administered the Building Better Caregivers workshops at their respective sites.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest.

If these analyses were to contribute to dissemination of the program from which the data are derived, KL and DDL have the potential to receive royalties.

Contributor Information

Kate Lorig, Stanford Patient Education Research Center, Stanford University School of Medicine.

Philip L. Ritter, Stanford Patient Education Research Center, Stanford University School of Medicine.

Diana D. Laurent, Stanford Patient Education Research Center, Stanford University School of Medicine.

Veronica Yank, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

References

- Akkerman RL, & Ostwald SK (2004). Reducing anxiety in Alzheimer’s disease family caregivers: the effectiveness of a nine-week cognitive-behavioral intervention. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 19(2), 117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakas T, Clark PC, Kelly-Hayes M, King RB, Lutz BJ, & Miller EL (2014). Evidence for stroke family caregiver and dyad interventions. Stroke, 45(9), 2836–2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control New York: W.H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp N, Irvine AB, Seeley J, & Johnson B (2005). Worksite-based internet multimedia program for family caregivers of persons with dementia. The Gerontologist, 45(6), 793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, Coon D, Czaja SJ, Gallagher-Thompson D, … & Martindale-Adams J (2006). Enhancing the Quality of Life of Dementia Caregivers from Different Ethnic or Racial GroupsA Randomized, Controlled Trial. Annals of internal medicine, 145(10), 727–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom MM, Zarit SH, Zwaaftink RBG, Cuijpers P, & Pot AM (2015). Effectiveness of an Internet intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia: results of a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One, 10(2), e0116622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Cognitive impairment: A call for action, now Atlanta, GA: CDC; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/cognitive_impairment/cogimp_poilicy_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, Rubenach S, & Winsor A (2003). A randomized controlled trial of an education and counselling intervention for families after stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation, 17(7), 703–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng LY, & Chan S (2005). Psychoeducation program for Chinese family carers of members with schizophrenia. Western journal of nursing research, 27(5), 583–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesla CA (2010). Do family interventions improve health?. Journal of family nursing, 16(4), 355–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon DW, Thompson L, Steffen A, Sorocco K, & Gallagher-Thompson D (2003). Anger and depression management: psychoeducational skill training interventions for women caregivers of a relative with dementia. The Gerontologist, 43(5), 678–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JM, Greiner AC, & Adams K (Eds.). (2004). 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit: A focus on communities Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry M, While A, Neenan K, & Smith V (2015). A systematic review of systematic reviews on interventions for caregivers of people with chronic conditions. Journal of advanced nursing, 71(4), 718–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper B, Bowring G, Thompson C, Van Heyst J, Conroy P, & Thompson J (2007). Stress in caregivers of aphasic stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical rehabilitation, 21(2), 122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisdorfer C, Czaja SJ, Loewenstein DA, Rubert MP, Argüelles S, Mitrani VB, & Szapocznik J (2003). The effect of a family therapy and technology-based intervention on caregiver depression. The Gerontologist, 43(4), 521–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Care Giver Alliance. (2016). Caregiver Statistics: Demographics Available from https://www.caregiver.org/caregiver-statistics-demographics.

- Gaugler JE, Reese M, & Mittelman MS (2016). Effects of the Minnesota adaptation of the NYU Caregiver Intervention on primary subjective stress of adult child caregivers of persons with dementia. The Gerontologist, 56(3), 461–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Belle SH, Burgio LD, Czaja SJ, Mahoney D, Gallagher-Thompson D, … & Ory MG (2003). Effect of multicomponent interventions on caregiver burden and depression: the REACH multisite initiative at 6-month follow-up. Psychology and aging, 18(3), 361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Marx K, Stanley IH, & Hodgson N (2015). Translating evidence-based dementia caregiving interventions into practice: State-of-the-science and next steps. The Gerontologist, gnu123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Burke J, Chernett N, Dennis MP, & Hauck WW (2008). Tailored activities to manage neuropsychiatric behaviors in persons with dementia and reduce caregiver burden: a randomized pilot study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(3), 229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, & Hauck WW (2010). A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: the COPE randomized trial. Jama, 304(9), 983–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JS, Elliott TR, Weaver M, Bartolucci AA, & Giger JN (2002). Telephone intervention with family caregivers of stroke survivors after rehabilitation. Stroke, 33(8), 2060–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gräsel E, Biehler J, Schmidt R, & Schupp W (2005). Intensification of the transition between inpatient neurological rehabilitation and home care of stroke patients. Controlled clinical trial with follow-up assessment six months after discharge. Clinical rehabilitation, 19(7), 725–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Zhang B, Smith ML, Lorden AL, Radcliff TA, Lorig K, … & Ory MG (2015). Concordance between self-reports and Medicare claims among participants in a national study of chronic disease self-management program. Frontiers in public health, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, & Mokdad AH (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of affective disorders, 114(1), 163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legg LA, Quinn TJ, Mahmood F, Weir CJ, Tierney J, Stott DJ, … & Langhorne P (2012). Nonpharmacological interventions for caregivers of stroke survivors. Stroke, 43(3), e30–e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, Brown BW Jr, Bandura A, Ritter P, … & Holman HR (1999). Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Medical care, 37(1), 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K; Stewart A; Ritter PL; Gonzalez V; Laurent D, & Lynch J (1996). Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Thompson-Gallagher D, Traylor L, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Plant K, … & Hahn TJ (2012). Building better caregivers: a pilot online support workshop for family caregivers of cognitively impaired adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 31(3), 423–437. [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman MS, & Bartels SJ (2014). Translating research into practice: Case study of a community-based dementia caregiver intervention. Health Affairs, 33(4), 587–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, Steinberg G, Ambinder A, Mackell JA, & Cohen J (1995). A comprehensive support program: effect on depression in spouse-caregivers of AD patients. The Gerontologist, 35(6), 792–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, Steinberg G, & Levin B (1996). A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 276(21), 1725–1731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman MS, Roth DL, Coon DW, & Haley WE (2004). Sustained benefit of supportive intervention for depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(5), 850–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman MS, Roth DL, Haley WE, & Zarit SH (2004). Effects of a caregiver intervention on negative caregiver appraisals of behavior problems in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: results of a randomized trial. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59(1), P27–P34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RJ, Gonyea JG, & Hooyman NR (1985). Caregiving and the experience of subjective and objective burden. Family relations, 19–26.

- Parks SM; Novielli KD (2000). A practical guide to caring for caregivers. Am Fam Physician, 62, 2613–2622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce LL, Steiner VL, Khuder SA, Govoni AL, & Horn LJ (2009). The effect of a Web-based stroke intervention on carers’ well-being and survivors’ use of healthcare services. Disability and rehabilitation, 31(20), 1676–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter PL, González VM, Laurent DD, & Lorig KR (2006). Measurement of pain using the visual numeric scale. The Journal of rheumatology, 33(3), 574–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter PL, Stewart AL, Kaymaz H, Sobel DS, Block DA, & Lorig KR (2001). Self-reports of health care utilization compared to provider records. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 54(2), 136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BC (1983). Validation of a caregiver strain index. Journal of gerontology, 38(3), 344–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving. (2012). Scaling up effective caregiver programs: best practices & new opportunities Retrieved from http://www.rosalynncarter.org/UserFiles/RCI(1).pdf.

- Schulz R, & Beach SR (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. Jama, 282(23), 2215–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, O’Brien A, Czaja S, Ory M, Norris R, Martire LM, … & Burns R (2002). Dementia caregiver intervention research in search of clinical significance. The gerontologist, 42(5), 589–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen S, Pinquart M, & Duberstein P (2002). How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. The gerontologist, 42(3), 356–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyu YIL, Kuo LM, Chen MC, & Chen ST (2010). A clinical trial of an individualised intervention programme for family caregivers of older stroke victims in Taiwan. Journal of clinical nursing, 19(11–12), 1675–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford Patient Education Research Center. (2016). Program Fidelity Manual, Stanford Self-Management Programs 2016 update Available at http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/licensing/FidelityManual2012.pdf.

- Steffen AM, McKibbin C, Zeiss AM, Gallagher-Thompson D, & Bandura A (2002). The revised scale for caregiving self-efficacy reliability and validity studies. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological sciences and social sciences, 57(1), P74–P86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH, Futterman AM, Gallagher-Thompson D, Rose JM, & Lovett SB (1993). Social support and caregiving burden in family caregivers of frail elders. Journal of Gerontology, 48(5), S245–S254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, Treweek S, Furberg CD, Altman DG, … & Chalkidou K (2009). A pragmatic–explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 62(5), 464–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Commerce. (1985). National Health Interview Survey Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census. [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel ET, de Witte LP, Stewart RE, Schure LM, Sanderman R, & Meyboom-de Jong B (2002). Long-term effects of a group support program and an individual support program for informal caregivers of stroke patients: which caregivers benefit the most?. Patient education and counseling, 47(4), 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Lee J, Bakker TJ, Duivenvoorden HJ, & Dröes RM (2014). Multivariate models of subjective caregiver burden in dementia: a systematic review. Ageing research reviews, 15, 76–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells TS, Horton JL, LeardMann CA, Jacobson IG, & Boyko EJ (2013). A comparison of the PRIME-MD PHQ-9 and PHQ-8 in a large military prospective study, the Millennium Cohort Study. Journal of affective disorders, 148(1), 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, & Bach-Peterson J (1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. The gerontologist, 20(6), 649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, … & Moher D (2008). Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Bmj, 337, a2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]