Abstract

Access and utilization of mental healthcare are critical components of ensuring public health. In this conceptual article, we define modifiable factors affecting mental healthcare utilization with the goal of providing a pragmatic framework for providers and clinics to increase access to mental healthcare. Five shared constructs emerged from a review of prominent health behavior theories: 1) mental illness beliefs, knowledge, and recognition; 2) mental health treatment beliefs and knowledge; 3) stigma including perceived norms, public stigma, and self-stigma; 4) help-seeking behaviors including knowledge, motivation, self-efficacy, and skills; and 5) external barriers and facilitators such as cues, logistics, and social support. We explore how these constructs influence mental healthcare utilization including interpretation and perception of mental health symptoms, acceptability and awareness of treatment options, and skills and ability to find, schedule, and attend mental healthcare. Finally, we make recommendations on how this broader framework can be used by primary care clinician innovators to implement interventions to reduce disparities and improve access to mental healthcare.

Keywords: Mental Health, Public Health, Help-Seeking Behavior, Patient Acceptance of Health Care, Delivery of Health Care

Mental health concerns contribute to significant public health burden in terms of financial cost and morbidity; and disproportionately affects disadvantaged individuals (Allen, Balfour, Bell, & Marmot, 2014; World Health Organization, 2017). Although most individuals in the United States eventually seek treatment, average delays in accessing care range from 4–23 years, and many individuals never receive services at all (Wang et al., 2005). Several factors associated with disease burden are also associated with delays in accessing treatment (e.g., education, racial/ethnic minority status) (Wang et al., 2005). Healthcare providers cannot directly change concerns such as pervasive cultural bias and poverty. However, healthcare providers can impact health behavior change in their consumers. By conceptualizing mental healthcare utilization as a health behavior, providers can apply health behavior theories to improve utilization. In this article, we refer to mental healthcare as any treatment for mental health concerns regardless of setting or modality. We recognize that different settings and modalities will be affected differently by the barriers and facilitators we identify (we use the patient centered medical home as an example in recommendations later in the manuscript but these concepts can also be applied more broadly). We use the term mental health rather than behavioral health as mental health is typically inclusive of substance use concerns but exclusive of health behaviors (e.g., diet and exercise) concerns. We believe that the concepts described in this manuscript could also directly apply to substance use concerns, and potentially to health behaviors with adaptation.

The purpose of this article is to synthesize key health behavior theories into a broad unified framework with shared constructs. The goal of this framework is to define modifiable constructs with direct clinical implications for improving mental healthcare access and utilization. We define modifiable constructs as constructs that can be changed through interventions at the patient-level, system-level, or community-level. Following introduction of the broad framework of modifiable constructs, we focus on application to a specific treatment setting and highlight existing strategies to improve mental healthcare access and utilization that can be implemented locally within a patient centered medical home.

Health Behavior Theories

We searched the literature for health behavior change theories and selected six theories with the following characteristics: (1) prominent in the field (e.g., commonly referenced in mental health treatment utilization literature), (2) novel contribution in terms of content and/or mechanisms, and (3) include at least some modifiable constructs at an individual, health systems, or community level. The rationale for ensuring that the theories include modifiable constructs is to focus on summarizing barriers/facilitators which can be targeted for change to improve mental healthcare access and utilization. Numerous theories of health behaviors have been proposed; a thorough review is beyond the scope of this manuscript.

The Health Belief Model (Rosenstock, 1974) stems from a social psychology approach to public health. In this model, health behaviors depend on individuals’ belief that they are susceptible to and/or have the disease (perceived susceptibility), belief the disease will negatively impact them (perceived seriousness), and belief that preventative action will help (Rosenstock, 1974). Preventative health behaviors also depend on awareness of mental health disorders (knowledge of the disease), whether perceived benefits outweigh perceived barriers, and presence of a cue to act (Rosenstock, 1974). Interventions based on the health belief model typically focus on public health strategies such as health promotion messaging, and include methods such as prompts and written, audiovisual, or professionally delivered health information (Jones, Smith, & Llewellyn, 2014).

The Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) focuses on cognitive processes, specifically that health behaviors depend on intention and perceived ability (Ajzen, 1991). Intention is influenced by three separate constructs: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm (i.e., “perceived social pressure”), and perceived behavioral control (i.e., ability) (Ajzen, 1991). These aggregate cognitive constructs are informed by beliefs about health behaviors, social norms, and behavioral control (Ajzen, 1991). An example of an intervention based on this theory is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Treatment-Seeking in which a clinician elicits thoughts about mental healthcare and conducts cognitive restructuring to enhance likelihood of the patient attending treatment or accepting a referral (Stecker, Fortney, & Sherbourne, 2011; Stecker, McGovern, & Herr, 2012; Stecker, McHugo, Xie, Whyman, & Jones, 2014).

The Integrated Behavioral Model (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015) was developed based on the Theory of Planned Behavior and Theory of Reasoned Action, but incorporates additional distinct constructs such as knowledge and skills to perform the behavior, salience of the behavior, environmental constraints, and past behaviors (habit) (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015). This model also specifies types of beliefs upon which attitude, perceived norm, and personal agency are based, and breaks these constructs down into separate component parts (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015). Interventions based on the Integrated Behavioral Model would be similar to the Theory of Planned Behavior (above) but might add elements for to address treatment-seeking skills and environmental constraints.

Mental Health Literacy (Jorm et al., 1997) refers to “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management, or prevention.” This concept does not propose a specific mechanism of change or behavior prediction, but describes components which inform the public’s conceptualization of mental health and treatment (Jorm et al., 1997). The modifiable components of mental health literacy include recognition and appropriate labeling of mental health concerns, beliefs about appropriate treatments, perceptions about prognosis, awareness of risk factors, and knowledge of how to seek information (Jorm et al., 1997). The Compass Strategy is a community awareness campaign designed to improve mental health literacy, including media campaigns, an informational website, a call center with coaching, and trainings for lay navigators and health professionals (Wright, McGorry, Harris, Jorm, & Pennell, 2006).

The Behavioral Model (Andersen, 1995) predicts health service utilization based on population characteristics including predisposing characteristics (e.g., demographics, social structure, and health beliefs), enabling resources (e.g., personal, family, and community resources), and perceived and evaluated need (Andersen, 1995). As the model grew, it also incorporated constructs such as characteristics of the health care system (e.g., policy, resources), other environmental factors, satisfaction and health outcomes, and other health behaviors (Andersen, 1995). In one example, Copeland and Butler (2007) present an application of the Behavioral Model providing practical recommendations to enhance access for African American women by focusing on socio-cultural influences on mental healthcare including racism and discrimination, social support networks and social environments, personal health practices, cultural backgrounds, and health beliefs.

The Transtheoretical Model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983) conceptualizes behavior change as a process progressing through five stages of change (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance) (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). The Transtheoretical Model was integral to the development of motivational interviewing, a direct clinical application of the model focusing on individuals’ specific perspectives on their behaviors, resolving ambivalence about behaviors, and eliciting innate motivation for behavior change (DiClemente & Velasquez, 2002; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). One example of how motivational interviewing has been applied to mental healthcare utilization is as a pre-treatment intervention to enhance compliance and outcomes for anxiety treatment (Westra, Arkowitz, & Dozois, 2009; Westra & Dozois, 2006).

Modifiable Constructs

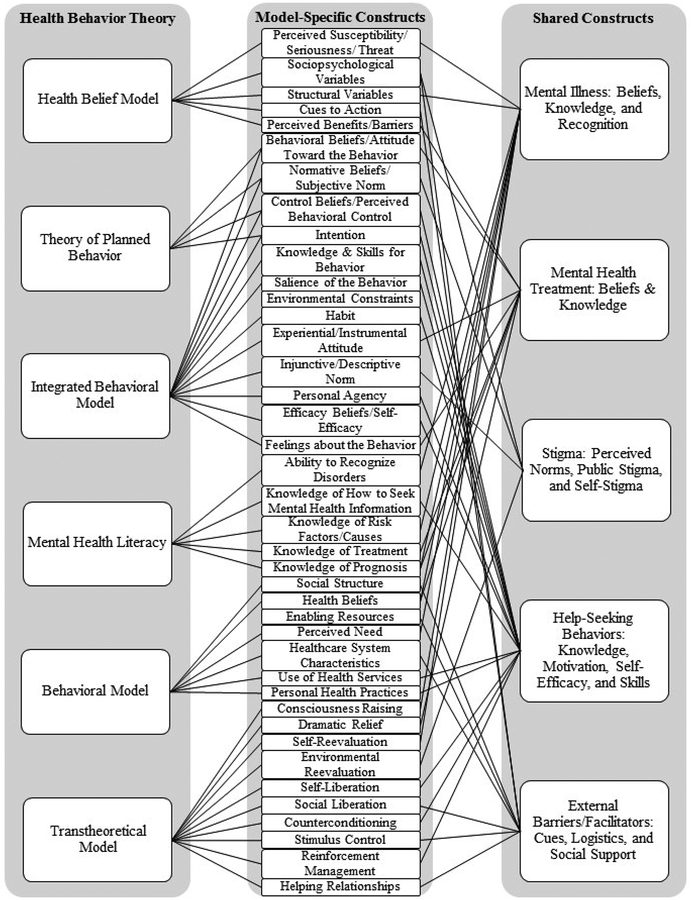

Individual modifiable elements from each health behavior theory were synthesized into shared constructs. Figure 1 displays the grouping results from the theory, to the specific constructs within each model, to the shared constructs. The process to develop Figure 1 involved organizing individual elements into tables with their label, corresponding theory, operational definitions, examples of corresponding interventions, examples of assessments/measures, and examples of cited articles from the literature. Based on operational definitions, similar elements were grouped into framework components based on author consensus. When grouping, we considered whether constructs would require different intervention (e.g., do beliefs about mental illness need a different intervention than knowledge about mental illness?), have a different function (e.g., beliefs about mental illness affect interpretation and recognition whereas beliefs about mental health treatment affect treatment choice), or have different locus (e.g., social support reflects an external resource whereas social norms is the internal perception of normal cultural behaviors). The next paragraphs describe the six shared constructs within our framework.

Figure 1.

Modifiable mental healthcare barriers and facilitators from prominent health behavior theories

Mental Illness: Beliefs, Knowledge, and Recognition.

This construct reflects beliefs, knowledge, and recognition of mental illness including ability to recognize symptoms, label mental illness, and understand course, risk factors, and causes of mental illness. For the purposes of this article, we operationally define “recognition” as the ability to appropriately attribute symptoms to mental health concerns and apply appropriate labels, “beliefs” as thoughts expressing an individual’s conceptualization, and “knowledge” as factual information. This construct is based on elements from the following theories: Health Belief model, Integrated Behavioral model, Behavioral Model, and Mental Health Literacy.

Mental Health Treatment: Beliefs & Knowledge.

This construct includes knowledge and beliefs about mental health treatment options including beliefs about treatment efficacy, awareness of availability, and expectations for treatment. This domain is differentiated from the prior domain because these belief categories function differently: beliefs/knowledge about mental illness influence awareness of the need to act, while beliefs about treatment influence the decision point after awareness. This construct is based on elements from the Health Belief model, the Theory of Planned Behavior, the Integrated Behavioral model, and the Mental Health Literacy framework.

Mental health stigma: perceived norms, public stigma, and self-stigma.

The definition used here is based on existing theories, and includes perceived norms, public stigma, and self-stigma (Ajzen, 1991; Corrigan, 2004). Perceived norms reflect perceptions of social standards regarding mental health diagnoses, treatment-seeking, and attitudes (for example, what you think your neighbor thinks about mental health) (Ajzen, 1991). Public stigma includes beliefs about other people with mental health concerns including stereotypes, prejudice, and acts of discrimination (Corrigan, 2004). Self-stigma is beliefs about the self related to mental health including stereotypes, prejudice, and acts of discrimination towards oneself (Corrigan, 2004). This construct is based on elements from the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Integrated Behavioral model.

Help-seeking behaviors: knowledge, motivation, self-efficacy, & skills.

This construct focuses on motivation and ability to enact help-seeking behaviors (e.g., researching appropriate treatment, communicating with providers, scheduling appointments, obtaining necessary childcare/transportation, etc.). This includes knowledge, such as procedural knowledge of how to obtain mental health treatment (e.g., find a provider/agency, obtain a referral). Motivation in this context is defined as readiness to obtain mental healthcare and includes factors that increase and decrease treatment-seeking drive. We define self-efficacy as perceived ability to successfully obtain mental healthcare, and skills as necessary behaviors to obtain mental healthcare (e.g., communication and organizational skills). This construct is based on elements from the Integrated Behavioral model, Transtheoretical model, Theory of Planned Behavior, and Mental Health Literacy framework.

External barriers/facilitators: cues, logistics, & social support.

The final construct is environmental factors including cues, logistics, and social support. Cues are signals to act from the environment (e.g., discussion with a provider about a screening result), logistics includes practical considerations for access (e.g., transportation, availability of childcare, insurance coverage, etc.), and social influences include emotional and practical support from family, friends, and community members, as well as, family and social norms about mental healthcare. This construct is based on elements from the Health Belief model, Integrated Behavioral model, and the Behavioral model.

Influence on Mental Healthcare Treatment Utilization Decisions and Behaviors.

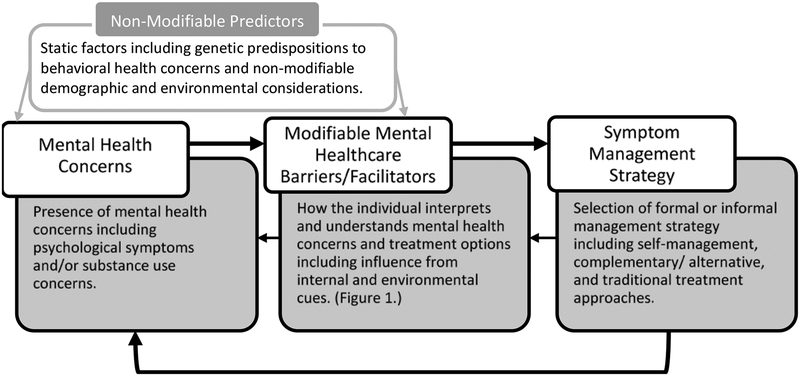

Based on the synthesis of the health behavior theories above, we generated a framework of how the shared modifiable constructs fit within the treatment-seeking process (Figure 2). Experience of psychological symptoms initiates the treatment-seeking process. The likelihood of experiencing those psychological symptoms is influenced by non-modifiable factors (e.g., age, gender, genetics, and other life experiences), and the modifiable constructs identified in Figure 1 (especially, recognition and beliefs about mental illness) influence the perception of those symptoms and treatments, as well as ability to engage in treatment. The modifiable constructs are also influenced by non-modifiable constructs including cultural context and availability of resources. The individual experiencing symptoms selects a symptom management strategy (e.g., self-management or professional treatment approaches). That decision influences the likelihood of continued symptoms, and changes the modifiable constructs through learning and experience. Each individual’s experience and each community is expected to be unique. For example, specific communities might have shared cultural beliefs about mental healthcare and or more logistical barriers resulting from fewer resources.

Figure 2.

Framework for how modifiable mental healthcare barriers and facilitators mediate treatment decisions

Strategies to Enhance Mental Healthcare Utilization

Patient-Centered Medical Homes are community based healthcare teams offering primary care services which “personalize, prioritize and integrate care to improve the health of whole people, families, communities and populations” (Stange et al., 2010). Patient-Centered Medical Homes are ideally situated to increase mental healthcare utilization among the communities they serve. Within each of the five shared constructs already reviewed, we highlight strategies to address unique patient and community needs which can be readily implemented at the patient level, at the healthcare team level, and at the community level (Table 1). Integrated behavioral health providers within the patient-centered medical home are ideally situated to help implement these strategies.

Table 1.

Examples of strategies within a Patient Centered Medical Home to improve mental health treatment utilization.

| Modifiable Mental Healthcare Factors | Patient-Level Interventions | Healthcare Systems-Level Interventions | Community-Level Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental illness: beliefs, knowledge, & recognition |

|

|

|

| Mental health treatment: beliefs & knowledge |

|

|

|

| Mental health stigma: perceived norms, public stigma, & self-stigma |

|

|

|

| Help-seeking behaviors: knowledge, motivation, self-efficacy, & skills |

|

|

|

| External barriers/facilitators: cues, logistics, & social support |

|

|

|

Note. MI stands for Motivational Interviewing. CBT-TS stands for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Treatment Seeking.

Individual-Level Interventions.

Changing care for an individual patient can involve engaging the entire patient centered medical home. We outline specific examples of how different members of an interprofessional team might work together. In practice, individual teams can identify the best team members to perform these functions within their own clinics. A process flow map might help individual teams with that activity (see (Colligan, Anderson, Potts, & Berman, 2010) for examples of styles and considerations). For example, medical providers can provide personalized feedback from mental health screenings and personalized education about individual risk factors and treatment options. These conversations can be facilitated by nursing staff completing screenings, providing informational materials to patients, and communicating results and preferences to providers prior to primary care appointments (Légaré et al., 2011). This conversation could be the basis for further discussion using a more structured approach such as shared decision making (Elwyn et al., 2012) or motivational interviewing to enhance treatment engagement (Westra & Dozois, 2006). Mental health providers embedded in medical clinics are ideally located to have ongoing discussion with patients about treatment options and engage in structured interventions.

Integrated behavioral health providers can implement specific services and interventions to increase mental healthcare utilization. In addition to motivational interviewing (described above), another structured approach to enhancing treatment engagement is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Treatment-Seeking (Stecker et al., 2011; Stecker et al., 2014). Other services may include peer support services, case management, and family services. Peer support services aim to reduce stigma and provide patient navigation (Chinman et al., 2014). Case management can be helpful for supporting treatment engagement (Holloway, Oliver, Collins, & Carson, 1995) and play a role in overcoming external barriers or skills deficits. Family groups and classes can help reduce stigma and increase social support for individual patients; NAMI is a national resource which provides local classes and family programming (https://www.nami.org/#).

Healthcare Systems.

Both local clinics and largescale healthcare systems can support providers and their patient population through administrative, human resources, and resources changes. Administrative changes might include standardizing mental health screening and flexible scheduling options for patients. Human resources changes might include staff education (e.g., mental health education, motivational interviewing training) and hiring personnel to provide integrated services (e.g., nurse care managers, primary care behavioral health providers). SAMHSA’s HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions (CIHS) (https://www.samhsa.gov/integrated-health-solutions) and the VA Center for Integrated Healthcare (https://www.mirecc.va.gov/cih-visn2/clinical_resources.asp) have resources available for clinics integrating mental health into primary care. SAMHSA also has resources available to aid in education programs for medical staff including The Power of Perceptions and Understanding which provides education to healthcare providers about how to provide recovery-sensitive services to substance use populations (https://www.samhsa.gov/power-perceptions-understanding) and SBIRT which is an approach appropriate for primary care settings for early intervention and treatment for substance use disorders (https://www.samhsa.gov/sbirt). Administrators can also ensure providers have appropriate educational materials (e.g., patient facing decision aids (Stacey et al., 2014)). SAMHSA’s Behavioral Health Equity program has informational materials about mental health concerns tailored to specific target groups (https://www.samhsa.gov/behavioral-health-equity).

Community-Based Approaches.

Community engagement involves prevention and outreach and can be facilitated through patient centered medical homes. SAMSHA has several resources available to plan and implement community approaches including the Center for the Application of Prevention Technologies (CAPT) which has guidance on how to plan and implement community mental health prevention programs (https://www.samhsa.gov/capt/), Community Conversations About Mental Health which provides guidance on community dialogue about mental health (https://www.samhsa.gov/community-conversations), and Faith-based and Community Initiatives (FBCI) which provide guidance on how federal programs can partner with faith-based and community organizations (https://www.samhsa.gov/faith-based-initiatives). One example of a specific program to enhance public awareness of mental health concerns is the “Mental Health First Aid” course which aims to educate community members to “identify, understand, and respond to signs of mental illnesses and substance use disorders” (Hadlaczky, Hökby, Mkrtchian, Carli, & Wasserman, 2014; “USA Mental Health First Aid,”). Local providers and clinics can take a leading role in implementing programs to benefit the communities they serve.

Limitations

The ideas in this article represent our own reflection and interpretation of the literature. Although we were purposeful and systematic in our selection, our methods do not have the rigor of a systematic review and are not exhaustive. Empirical research studies with more rigorous methods could test the validity of these concepts. For example, future studies could use confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate the validity of the discrete domains and studies utilizing prospective modeling could evaluate the relationship of these domains on subsequent mental healthcare utilization.

Conclusions

The five modifiable factors proposed here reflect shared constructs within established theories of health behaviors affecting mental healthcare utilization and access. This synthesis was developed to focus on concrete actionable items which can be targeted by individual clinics and providers to improve access to mental healthcare. One key conclusion is that integrating behavioral health into primary care can facilitate access on multiple levels. Although the interventions we suggested do not change the underlying factors causing mental healthcare disparities, by focusing on concrete changes in clinics and healthcare systems serving at-risk populations, providers and administrators can give vulnerable individuals the best opportunity to receive appropriate and adequate mental healthcare.

References

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R, & Marmot M (2014). Social determinants of mental health. International review of psychiatry, 26(4), 392–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of health and social behavior, 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinman M, George P, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, Swift A, & Delphin-Rittmon ME (2014). Peer support services for individuals with serious mental illnesses: assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 65(4), 429–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colligan L, Anderson JE, Potts HW, & Berman J (2010). Does the process map influence the outcome of quality improvement work? A comparison of a sequential flow diagram and a hierarchical task analysis diagram. BMC health services research, 10(1), 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland VC, & Butler J (2007). Reconceptualizing access: A cultural competence approach to improving the mental health of African American women. Social Work in Public Health, 23(2–3), 35–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American psychologist, 59(7), 614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, & Velasquez MM (2002). Motivational interviewing and the stages of change. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change, 2, 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, … Rollnick S (2012). Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(10), 1361–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadlaczky G, Hökby S, Mkrtchian A, Carli V, & Wasserman D (2014). Mental Health First Aid is an effective public health intervention for improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour: A meta-analysis. International review of psychiatry, 26(4), 467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway F, Oliver N, Collins E, & Carson J (1995). Case management: A critical review of the outcome literature. European Psychiatry, 10(3), 113–128. doi: 10.1016/0767-399X(96)80101-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CJ, Smith H, & Llewellyn C (2014). Evaluating the effectiveness of health belief model interventions in improving adherence: a systematic review. Health psychology review, 8(3), 253–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm A, Korten A, Jacomb P, Christensen H, Rodgers B, & Pollitt P (1997). “Mental health literacy”: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. The Medical journal of Australia, 166(4), 182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, Dunn S, Pluye P, Frosch D, … Graham ID (2011). Validating a conceptual model for an inter-professional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 17(4), 554–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2002). Facilitating Change Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed, pp. 20–32). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montaño DE, & Kasprzyk D (2015). Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. Health behavior: Theory, research and practice, 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, & DiClemente CC (1983). Stages and processes of self-change toward smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, & Velicer WF (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American journal of health promotion, 12(1), 38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM (1974). Historical origins of the health belief model. Health education monographs, 2(4), 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, … Thomson R (2014). Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 1(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Jaén CR, Crabtree BF, Flocke SA, & Gill JM (2010). Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(6), 601–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker T, Fortney JC, & Sherbourne CD (2011). An intervention to increase mental health treatment engagement among OIF veterans: A pilot trial. Military Medicine, 176(6), 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker T, McGovern MP, & Herr B (2012). An intervention to increase alcohol treatment engagement: A pilot trial. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 43(2), 161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker T, McHugo G, Xie H, Whyman K, & Jones M (2014). A randomized controlled trial of a phone-based cognitive-behavioral intervention to improve PTSD treatment utilization among returning service members. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC), 65(10), 1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USA Mental Health First Aid. (2018). Retrieved July 7, 2018, 2018, from https://www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org/

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, & Kessler RC (2005). Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 603–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Arkowitz H, & Dozois DJ (2009). Adding a motivational interviewing pretreatment to cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(8), 1106–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, & Dozois DJ (2006). Preparing clients for cognitive behavioral therapy: A randomized pilot study of motivational interviewing for anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30(4), 481–498. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, W. H. O. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates.

- Wright A, McGorry PD, Harris MG, Jorm AF, & Pennell K (2006). Development and evaluation of a youth mental health community awareness campaign–The Compass Strategy. BMC public health, 6(1), 215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]