ABSTRACT

Background: Emotion regulation difficulties are common among individuals from refugee backgrounds. Little is known, however, about whether there are specific patterns relating to the types of emotion regulation strategies commonly employed by refugees, nor how this relates to psychopathology. Moreover, wider literature on emotion regulation has primarily focused on examining specific emotion regulation strategies in isolation, rather than patterns of emotion regulation across multiple strategies.

Objective: The current study was the first to identify individual differences in patterns of habitual emotion regulation among refugees, and explore their unique associations with trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms.

Method: Levels of trait reappraisal and suppression were measured among 93 refugees, using the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire and the White Bear Suppression Inventory. A latent class analysis was conducted to identify distinct classes of participants based on differing levels of habitual engagement in reappraisal and suppression. The association between class membership and key variables indexing refugee experiences (e.g. trauma exposure) and psychopathology (e.g. PTSD symptoms and emotion dysregulation) were also examined.

Results: Latent class analysis revealed three distinct profiles of habitual emotion regulation: a high regulators class (55.7%; high trait reappraisal/high trait suppression), an adaptive regulators class (23.6%; high trait reappraisal/moderate trait suppression), and a maladaptive regulators class (20.6%; low trait reappraisal/high trait suppression). Each class evidenced unique relations with trauma exposure and psychopathology. Compared to adaptive regulators, maladaptive regulators had more PTSD symptoms, experienced greater emotion dysregulation, and were more likely to be female, while high regulators had experienced more types of traumatic events.

Conclusions: This study identified distinct patterns of emotion regulation among refugees. Our findings demonstrate the importance of measuring multiple strategies to uncover patterns of emotion regulation and better understand the links between emotion regulation and psychopathology, which has important implications for the development of effective treatment with traumatized refugees.

KEYWORDS: Emotion regulation, reappraisal, suppression, refugees, trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder, latent class analysis

HIGHLIGHTS

• A latent class analysis of habitual engagement in key emotion regulation strategies (reappraisal and suppression) was conducted among refugees.• Three distinct emotion regulation profiles emerged: high regulators (55.7%; high trait reappraisal/high trait suppression), adaptive regulators (23.6%; high trait reappraisal/moderate trait suppression), and maladaptive regulators (20.6%; low trait reappraisal/high trait suppression).• Compared to adaptive regulators, maladaptive regulators had more PTSD symptoms, while high regulators had been exposed to more types of traumatic events.

Abstract

Antecedentes: Las dificultades en la regulación emocional son frecuentes entre los individuos con historial de ser refugiados. Sin embargo, se sabe poco acerca de si hay patrones específicos relacionados a los tipos de estrategias de regulación emocional comúnmente utilizadas por los refugiados, ni cómo esto se relaciona con psicopatología. Además, la literatura general sobre regulación emocional se ha focalizado principalmente en examinar estrategias específicas de regulación emocional de forma individual, en vez de patrones de regulación emocional a través de múltiples estrategias.

Objetivo: El presente estudio fue el primero para identificar las diferencias individuales en los patrones de regulación emocional habituales entre refugiados y explorar sus asociaciones específicas con la exposición al trauma y a síntomas de TEPT.

Método: Se midieron los niveles de reevaluación y supresión de rasgos entre 93 refugiados, usando el Cuestionario de Regulación Emocional y el Inventario de Supresión del Oso Blanco. Se condujo un análisis de clase latentes para identificar las clases distintas de participantes basados en diferentes niveles de participación habitual en la reevaluación y supresión. Se examinaron también la asociación entre la pertenencia a clases y las variables claves que indexan las experiencias de los refugiados (ej. Exposición a trauma) y psicopatología (ej. Síntomas de TEPT y des-regulación emocional).

Resultados: El análisis de clase latentes reveló tres perfiles distintos de regulación emocional habitual: una clase de altos reguladores (55,7%; rasgos de reevaluación altos/rasgos de supresión altos), una clase de reguladores adaptativos (23,6%; rasgos de reevaluación altos/rasgos de supresión moderados), y una clase de reguladores inadaptados (20,6%; rasgos de reevaluación bajos/rasgos de supresión altos). Cada clase evidenció relaciones únicas con la exposición al trauma y psicopatología. En comparación con los reguladores adaptativos, los reguladores inadaptados tenían más síntomas de TEPT, experimentaron des-regulación emocional más alta y con mayor probabilidad eran mujeres, mientras que los reguladores altos habían experimentado más tipos de eventos traumáticos.

Conclusiones: Este estudio identificó patrones distintivos de regulación emocional entre los refugiados. Nuestros hallazgos demuestran la importancia de medir múltiples estrategias para descubrir los patrones de regulación emocional y entender mejor la relación entre regulación emocional y psicopatología, lo que tiene implicancias importantes para el desarrollo de un tratamiento efectivo con refugiados traumatizados.

PALABRAS CLAVES: Regulación emocional, re-evaluación, Supresión, refugiados, Exposición a trauma, Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático, Análisis de clase latentes

Abstract

背景: 情绪调节困难在来自难民背景的个体中很常见。然而,是否存在与难民常用的情绪调节策略类型有关的特定模式,以及其与精神病症的关系还鲜为人知。此外,更广泛的情绪调节方面的文献都主要侧重于独立考查特定的情绪调节策略,而不是跨多种策略的情绪调节模式。

目的: 本研究是首个旨在识别出难民中习惯性情绪调节模式的个体差异,并探究其与创伤暴露和创伤后应激障碍症状的独特关联的研究。

方法: 使用情绪调节问卷和白熊抑制问卷测量了93名难民中的特质重评和抑制水平。根据重评和抑制中习惯性参与的不同水平,进行潜在类别分析以识别不同类别的参与者。还检查了类别中成员与反映难民经历的关键变量(例如,创伤暴露)和精神病症(例如,创伤后应激障碍症状和情绪失调)之间的关联。

结果: 潜在类别分析揭示了习惯性情绪调节的三种不同剖面图:高调节因者类(55.7%;高特质重评/高特征抑制),适应性调节者类(23.6%;高特质重新评估/中度特质抑制),以及适应不良的调节者类(20.6%;低特质重评/高特质抑制)。每个类别都表明了与创伤暴露和精神病症的独特关系。与适应性调节者相比,适应不良的调节者有更多的创伤后应激障碍症状、经历了更多的情绪失调、更可能是女性,而高调节者经历了更多种类的创伤事件。

结论: 本研究识别出了难民中不同的情绪调节模式。我们的研究结果证明了为发现情绪调节的模式、更好地理解情绪调节与精神病症间的联系,测量多种策略的重要性。这对于创伤难民的有效疗法的发展具有重要意义。

Abbreviations: AIC = Akaike’s Information Criterion; APA = American Psychiatric Association; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DSM-IV = Fourth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-V = Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ER = Emotion regulation; ERQ = Emotion Regulation Questionnaire HTQ = Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; LCA = Latent Class Analysis; LMR-LRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test; LPA = Latent Profile Analysis; PSSI = PTSD Symptom Scale - Interview Version; PTE = Potentially traumatic event; PTSD = Post-traumatic stress disorder; SS-BIC = Sample-Size Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion; STAIR = Skills Training in Affect and Interpersonal Regulation; UNHCR = United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; VLMR-LRT = Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test; WBSI = White Bear Suppression Inventory; WHO = World Health Organization

关键词: 情绪调节, 重评, 抑制, 难民, 创伤暴露, 创伤后应激障碍, 潜在类别分析

In 2017, an average of 44,400 people per day were forced to flee their homes as a result of persecution, conflict or generalized violence (United Nations High Comissioner for Refugees; UNHCR, 2018). By the end of the same year, the global population of refugees, asylum-seekers and internally displaced people had risen to 68.5 million, and this number is continuing to grow (UNHCR, 2018). At the same time, research has robustly demonstrated that refugees and asylum-seekers experience multiple and severe forms of traumatization and report elevated rates of psychological disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression (Bogic, Njoku, & Priebe, 2015). In order to meet this substantial global challenge to public health, it is incumbent on clinical research to identify and understand the mechanisms that underpin the development and maintenance of psychopathology among traumatized refugees. Ultimately, such research could facilitate the development of effective and culturally robust psychological interventions, and thus reduce the global burden of suffering. Although such research is sparse, one potential mechanism that appears promising in elucidating this relationship is emotion regulation (ER).

ER relates to an individual’s ability to monitor, evaluate and change aspects of their emotional experience or expression (Gross, 2014). Importantly, the inability to regulate one’s emotions effectively, i.e. emotion dysregulation, has been strongly associated with psychopathology, particularly mood and anxiety disorders (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010). Extant research has identified refugees as a population that may be especially likely to experience ER difficulties (Doolan, Bryant, Liddell, & Nickerson, 2017). Key aspects of the refugee experience, such as interpersonal trauma including torture and persecution, forced displacement, and post-migratory stressors such as family separation and visa uncertainty, have been associated with disruptions to adaptive ER (Nickerson et al., 2015, 2016). Moreover, emerging research has identified emotion dysregulation as an important transdiagnostic factor relating to psychopathology among refugees. Empirical investigations of emotion dysregulation often use the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004), which quantifies the functional impairments that may result from disruptions to adaptive ER across six domains: non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties in engaging in goal-directed behaviour, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to ER strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. A recent study by Koch, Liedl, and Ehring (2019) with refugees found that levels of emotion dysregulation, measured using the DERS, accounted for significant variance in PTSD, depression, anxiety and insomnia symptoms over and above trauma exposure. Relatedly, in another study with refugees, Nickerson et al. (2015) found that the relationship between trauma exposure and PTSD was mediated by levels of emotion dysregulation. Despite this, very little empirical research has investigated the role of ER in the development and maintenance of psychopathology following refugee experiences of trauma and displacement.

Germane investigations have implicated specific ER strategies in the relationship between trauma exposure and psychopathology among refugees. For instance, the use of cognitive reappraisal, an ER strategy that involves reframing the situation or event to reduce the intensity of the emotional response, while viewing trauma-related visual stimuli caused a reduction in PTSD symptoms of intrusive memories among refugees who had previously reported high levels of PTSD symptoms (Nickerson et al., 2017). Interestingly, this observed effect was moderated by participants’ pre-existing levels of trait suppression, an ER strategy that involves actively attempting to reduce, eliminate or hide one’s emotional experience. Here, individuals with relatively low trait suppression, despite high PTSD symptomology, demonstrated significantly reduced negative affect when employing reappraisal. Such findings suggest that habitual, or trait, ER behaviours may influence an individual’s ability to manage psychological distress. As such, the ER strategies that refugees habitually use might have important implications for psychotherapy. For instance, clinicians working with refugees will need to understand how habitual ER styles might serve to augment, or undermine, the utility of interventions that promote the use of adaptive ER strategies to manage contemporary stressors. Additionally, it remains unclear how the selection of specific ER strategies may relate to overall levels of emotion dysregulation or functional impairment among refugees. Given this, a comprehensive investigation of routine ER strategy use, and how this relates to psychopathology and emotion dysregulation, among refugees is warranted.

Literature on trauma and psychopathology more broadly has identified the deleterious effect of suppression, and beneficial impact of cognitive reappraisal (Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Gross & John, 2003; Gross & Levenson, 1997). However, the vast majority of this empirical research has used designs that examine the one-to-one relationship between specific strategies and psychological outcomes. In doing so, these designs assume that individuals manage their affect in each situation using only one ER strategy. Although a helpful initial line of investigation, growing evidence suggests that such designs oversimplify the complex process in which individuals select and implement strategies to regulate affect across varying situations. Research by Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema (2013) demonstrated that individuals spontaneously employ multiple ER strategies over the course of an emotion-eliciting situation. This finding is particularly interesting as it suggests that people have a repertoire of ER strategies at their disposal. Given this, it is possible that individuals implement a combination of strategies, including both putatively adaptive and maladaptive strategies, both within a single emotion-eliciting event and across various emotion-eliciting events. Consequently, to better understand real-world ER use, conventional methodological approaches must be expanded to consider the breadth of ER strategies that individuals routinely employ. Broadening the scope of enquiry would allow us to identify individual differences in ER repertories as well as how such differences might uniquely relate to psychopathology.

One methodology particularly well suited to capturing this heterogeneity in ER repertories is Latent Class Analysis (LCA) or Latent Profile Analysis (LPA). LCA has the potential to overcome limitations in conventional methodologies, which focus on single ER strategies, by classifying individuals according to their behaviours across multiple ER strategies. LCA is a statistical technique that groups individuals into latent classes (i.e. homogenous subgroups) according to designated variables, such as common use of certain ER strategies. In doing so, LCA employs a person-centred approach, where individual variation in ER repertoires is considered, to examine population heterogeneity in ER.

Studies that have examined multiple ER strategies using LCA have demonstrated this to be a fruitful approach to studying the relationship between ER and psychological functioning, although none have been conducted with refugee populations. For instance, Lougheed and Hollenstein (2012) conducted an LCA with a community sample of adolescents, and found that ER profiles that were characterized by a reliance on putatively maladaptive strategies (e.g. suppression and concealing emotions) were associated with greater internalizing problems compared to ER profiles that comprised a balanced range of all strategies or a reliance on putatively adaptive strategies (e.g. adjustment focussed approaches). Also, ER profiles that were characterized by a limited ER repertoire (e.g. low use of ER strategies) were significantly associated with greater internalizing problems. In this way, the beneficial or deleterious impact of ER on psychological functioning seems to relate to an individual’s pattern of ER strategy use, rather than the decision to implement a specific strategy.

Additionally, an LCA by Dixon-Gordon, Aldao, and De Los Reyes (2014), found five distinct profiles of ER strategy use among undergraduate students: adaptive regulators (high levels of putatively adaptive strategies – reappraisal, acceptance and problem solving – and lower levels of putatively maladaptive strategies – worry/rumination, self-criticism, expressive suppression and experiential avoidance), low regulators (low engagement across all strategies), high regulators (high engagement across all strategies), worriers (especially high levels of worry/rumination), and avoiders (especially high levels of expressive suppression and experiential avoidance). Importantly, the distinct ER repertoires evidenced unique associations with symptoms of psychopathology, where adaptive regulators were linked to fewer symptoms of psychopathology while worriers were linked to greater symptoms of psychopathology. However, contrary to Lougheed and Hollenstein (2012) findings, Dixon-Gordon et al. instead found that low regulators were associated with fewer, and high regulators were associated with greater, symptoms of psychopathology. These contradictory findings may be explained by methodological differences between the two studies. Rather than measuring habitual strategy usage, as in Lougheed and Hollensteni’s study, participants in Dixon-Gordon et al.’s study were asked to recall strategy usage for a single negative event, which participants selected themselves. As such, it is possible that low regulators therefore represented individuals who experienced relatively little distress during their chosen event, and hence, had little need to emotionally regulate, rather than representing individuals with relatively deficient ER repertoires, and vice versa for high regulators. Additionally, as Dixon-Gordon and colleagues measured immediate engagement in different ER strategies following a single recalled negative event, it is difficult to determine how characteristic these scenarios were of participant’s typical stressors and habitual ER behaviours. It would therefore be beneficial for future research to construct ER repertoires based on habitual ER usage, which may be more robust against recall biases and fluctuations in emotion-eliciting events and individuals ER responses to them.

In this way, owing to mixed findings among extant research, further investigations are merited to develop a robust methodology based on habitual ER behaviours and explore ER repertoires among clinical samples. Moreover, no study has examined ER repertoires, nor how they may relate to psychopathology and emotion dysregulation, among refugees. Such an investigation would greatly advance not only our understanding of how trauma-exposed individuals may differ in their ER repertoires, but also how these differences may relate to psychopathology and heterogeneous refugee experiences.

1. The present study

The current study aimed to identify individual differences in habitual ER repertoires among refugees, and determine how they relate to trauma exposure, psychopathology, and emotion dysregulation. To this end, scores on measures of trait suppression and trait reappraisal were examined to determine whether distinct profiles emerged. Based on research by Dixon-Gordon et al. (2014), four ER profiles were hypothesized: high regulators (high levels of habitual suppression and reappraisal), low regulators (low levels of habitual suppression and reappraisal), adaptive regulators (high levels of reappraisal, and low levels of suppression), and maladaptive regulators (high levels of suppression, and low levels of reappraisal). In line with prior research by Dixon-Gordon et al. (2014) and Lougheed and Hollenstein (2012), we anticipated that the adaptive regulators class would be associated with better psychological well-being and less overall emotion dysregulation, compared to the maladaptive regulators class. Also, extending Dixon-Gordon et al.’s results, we hypothesized that the high regulators class would have poorer outcomes compared to individuals in the adaptive or low regulators classes.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Ninety-three adult refugees and asylum-seekers resettled in Australia participated in the current study, which was conducted between May of 2013 and December of 2014 at a hospital-based outpatient research clinic. Two-thirds of the sample were male (N = 62, 66.7%) and the mean age was 34.51 years (SD = 9.98). Participants had lived in Australia for a mean of 2.56 years (SD = 3.55, range = 4 months to 19 years), and the majority of participants had an insecure visa status (i.e. held temporary bridging visas or expired visas; 76, 81.7%). Participants had diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds, as outlined in Table 1. Although the country of origins of our participants were broadly reflective of Australia’s wider refugee population at the time of recruitment, it is noted that the proportion of refugees from Iran was slightly higher in our sample.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of refugees settled in Australia.

| Variable | M or n | SD or % |

|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 62 | 66.7% |

| Age, years | 34.51 | 09.98 |

| Country of Birth | ||

| Iran | 50 | 53.8 |

| Sri Lanka | 11 | 11.8 |

| Afghanistan | 10 | 10.8 |

| Iraq | 07 | 07.5 |

| Bangladesh | 06 | 06.5 |

| Others | 09 | 09.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Persian | 033 | 35.5 |

| Tamil | 010 | 10.8 |

| Farsi | 007 | 07.5 |

| Hazara | 006 | 06.5 |

| Iraqi | 006 | 06.5 |

| Kurdish | 006 | 06.5 |

| Others | 025 | 027.6 |

| Years in Australia | 002.56 | 03.55 |

| Visa Status | ||

| Secure | 015 | 16.1 |

| Insecure | 076 | 81.7 |

| Missing | 002 | 02.2 |

2.2. Measures

All measures used in the current study were translated, and blind back translated, into Arabic, Farsi and Tamil by accredited translators, using gold-standard procedures (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2017). Following this, the research team, in collaboration with accredited interpreters, resolved the few discrepancies that emerged from this process.

2.2.1. Exposure to potentially traumatic events (PTEs)

Exposure to different types of PTEs, such as forced isolation, serious injury and torture, were indexed using the 16-item Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ; Mollica et al., 1992). For the present study, a total count of the types of PTEs that each individual had experienced and/or witnessed was derived (range = 0–16).

2.2.2. PTSD symptoms

The PTSD Symptom Scale – Interview Version (PSSI; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993) was used to assess PTSD symptoms. The PSSI is a 17 item semi-structured interview, which assesses DSM-IV symptoms of PTSD. However, in line with the DSM-5 criteria for PTSD, the present study adapted the interview by removing the item pertaining to a sense of a foreshortened future, and adding four additional items to reflect the newly added DSM-5 PTSD symptoms, to comprised 20 items in total. Each symptom was rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = not at all and 3 = five or more times per week/very much). Scores were summed to create a total symptom score. The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.92) and has previously been used with refugee populations (e.g. Pfeiffer & Elbert, 2011). Criteria for a probable PTSD diagnosis was met if participants endorsed at least: one re-experiencing and one avoidance item, and two negative mood and cognitions and two alternations in arousal and reactivity items (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

2.2.3. Trait suppression

The White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI; Wegner & Zanakos, 1994) was used to assess levels of trait suppression. Participants were asked to rate each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). Prior factor analyses of the scale have identified two factors: unwanted intrusive thoughts, and thought suppression (Höping & de Jong-Meyer, 2003). The current study used responses from the five items of the thought suppression factor (items 1, 10, 11, 13 and 14). Endorsed items, assessed as ratings of 4 or above (i.e. Agree or Strongly Agree), were summed. WBSI has previously demonstrated good psychometric properties (Muris, Merckelbach, & Horselenberg, 1996) and has been used with non-western samples (e.g. Altin & Gencöz, 2009). The thought suppression subscale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.74).

2.2.4. Trait reappraisal

The 6-item reappraisal subscale of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross & John, 2003) was used to measure participants habitual engagement in reappraisal. Participants were asked to rate each item on a 7-point Likert-type scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. Endorsed items, measured as ratings of 5 or above (i.e. ratings above the neutral point of the scale), were summed. This instrument has demonstrated good psychometric properties and has been used cross-culturally (Megreya, Latzman, Al-Emadi, & Al-Attiyah, 2018). The reappraisal subscale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.78).

2.2.5. Emotion dysregulation

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) was administered to measure overall levels of emotion dysregulation. The present study used the shortened 18-item version of the original 36-item self-report questionnaire. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (where 1 = almost never and 5 = almost always) and summed to create an overall measure of ER difficulties. The abridged scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Victor & Klonsky, 2016) and showed excellent internal consistency (α = 0.90).

2.3. Procedure

The study was conducted by masters- or doctoral-level clinical psychologists who verbally administered all measures, with the aid of an accredited interpreter where necessary. Participants first provided demographic details before completing a battery of measures, which included the WBSI, ERQ, DERS, HTQ and PSSI. At the completion of the testing, each participant received a gift voucher ($AUD25). The University of New South Wales Research Ethics Committee provided ethics approval for the study.

2.4. Data analysis

Latent class analysis (LCA) was used to model profiles of habitual ER based on items assessing trait suppression and reappraisal, using Mplus version 8 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2017). In the current study, latent classes were identified on the basis of 5 dichotomous indicators of trait suppression, derived from scores on the WBSI, and 6 dichotomous indicators of trait reappraisal, derived from scores on the ERQ. Any data that was missing on the indicator variables was accounted for by employing full information maximum likelihood estimation, which adjusts parameter estimates based on patterns of missing data.

The optimal number of latent classes was determined by first fitting the most parsimonious model (i.e. a one-class solution) to the data, followed by successive models with increasing numbers of classes. The following indices were used to compare the fit of successive models: Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the Sample-Size Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (SS-BIC), Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), entropy, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT) and the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR-LRT). Lower values of the BIC, SS-BIC and AIC, and higher values of entropy indicate better fit. A significant LMR-LRT or VLMR-LRT suggests that a model fits the data better than a model with one less class. Finally, interpretability and parsimony were also taken into account to identify the optimal class solution. Item probabilities within classes were evaluated using the following guidelines: values ≥ 0.60 were considered to represent a high probability of endorsement, values ≤ 0.59 and ≥ 0.16 were considered to represent a moderate probability of endorsement, and values ≤ 0.15 were considered to represent a low probability of endorsement (Galatzer-Levy, Nickerson, Litz, & Marmar, 2013).

Once the optimal unconditional model was determined, predictors of class membership were identified by conducting multinomial logistic regression. The current study employed univariate regressions, to separately regress the predictors of age, gender, trauma exposure, PTSD symptoms and emotion regulation difficulties on the derived classes. Each predictor was analysed separately as an auxiliary variable because including all predictors in a single model would render this model too complex for the small sample size of the present study (N = 93). The univariate multinomial logistic regressions were performed on MPlus using the three-step approach outlined by Asparouhov and Muthén (2014). In this approach, the first step involved the estimation of the latent class model. Next, a variable representing the most likely class was created using latent class posterior distribution, which took into account potential error in classification. Finally, the third step involved the investigation of the association between the predictor variable and class membership variable, taking into account the probability of correct classification into classes. The missing data rate across the auxiliary (predictor) variables was less than 5%, and thus listwise deletion was employed.

3. Results

3.1. Trauma exposure and PTSD

Responses on the HTQ indicated that rates of trauma exposure were high, with participants being exposed to an average of 8.79 types of PTEs (SD = 3.47). The frequency of exposure to different PTEs are presented in Table 2. Overall, 28% of the sample met criteria for a PTSD diagnosis, as assessed using the clinician-administered PSSI.

Table 2.

Exposure to potentially traumatic events.

| Trauma type | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Serious injury | 73 | 78.5 |

| Lack of food or water | 71 | 76.3 |

| Being close to death | 71 | 76.3 |

| Ill health without access to medical care | 68 | 73.1 |

| Imprisonment | 60 | 64.5 |

| Combat situation | 59 | 63.4 |

| Murder of stranger or strangers | 55 | 59.1 |

| Lack of shelter | 54 | 58.0 |

| Unnatural death of family or friend | 53 | 57.0 |

| Murder of family or friend | 50 | 53.7 |

| Forced separation from family members | 48 | 51.6 |

| Torture | 40 | 43.0 |

| Forced isolation from others | 34 | 36.5 |

| Brain washing | 32 | 34.4 |

| Lost or kidnapped | 26 | 27.9 |

| Rape or sexual abuse | 15 | 16.1 |

3.2. Latent class analysis

3.2.1. Unconditional models

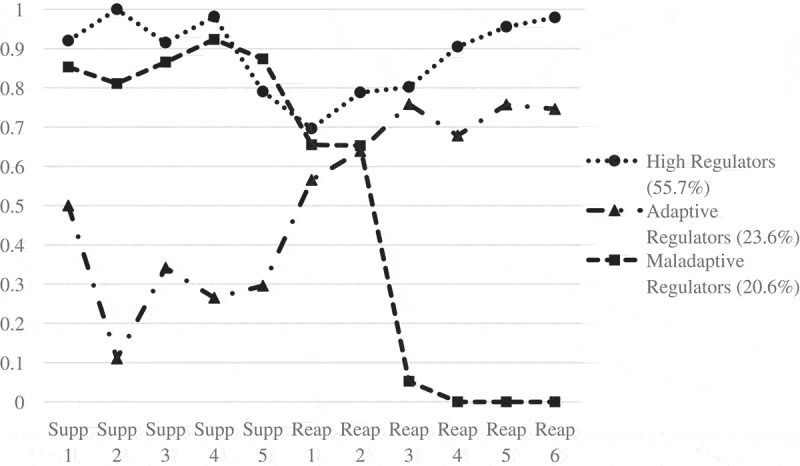

The goodness-of-fit indices for the one- to five-class models are presented in Table 3. Latent class analysis indicated that a three-class solution fit the data best. There were substantial reductions in all information criteria (AIC, BIC and SS-BIC) until the three-class solution. In particular, the addition of a third class yielded a decrease of 60 points in the AIC and 68 points on the SS-BIC. The four- class solution was instead associated with relatively smaller reductions across information criteria, and the five-class solution saw a slight increase in AIC and BIC. All solutions demonstrated high entropy (>0.94), suggesting good class identification. The LMR-LRT and VLMR-LRT were significant for the two-class model and marginally significant for the three- and four-class models. Further, LMR-LRT and VLMR-LRT indicated that the five-class solution did not fit the data better than the four-class solution. Inspection of the class plots demonstrated that the three-class solution yielded three distinguishable classes, each with membership of at least 20% of the sample. In contrast, the four-class solution was identical to the three-class solution with the addition of a fourth class, comprising four participants, which was not theoretically meaningful. Considering this, the three-class solution was retained (see Figure 1).

Table 3.

Goodness-of-fit indices for ER profile class solutions.

| AIC | BIC | SS-BIC | Entropy | LMR-LRT | VLMR-LRT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 class | 1125.434 | 1152.932 | 1118.215 | |||

| 2 class | 1004.577 | 1062.072 | 989.483 | 0.943 | 0.0012 | 0.0011 |

| 3 class | 944.596 | 1032.089 | 921.626 | 0.940 | 0.0841 | 0.0809 |

| 4 class | 935.727 | 1053.218 | 904.882 | 0.972 | 0.0635 | 0.0661 |

| 5 class | 936.176 | 1083.665 | 897.457 | 0.966 | 0.4308 | 0.4238 |

AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; SS-BIC = sample size-adjusted Bayesian information criterion; LMR-LRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ration test; VLMR-LRT = Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ration test.

Figure 1.

Probabilities of item endorsement for each latent class.

Supp 1 to Supp 5 denotes the five items measuring trait suppression, from the WBSI. Reap 1 to Reap 6 denotes the six items measuring trait reappraisal, from the ERQ. The actual items are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4 outlines the conditional probabilities for trait suppression and reappraisal item endorsement according to class membership. The classes within this solution can be described as a high regulators class (55.7%), an adaptive regulators class (25.6%), and a maladaptive regulators class (20.6%). Participants in the high regulators class evidenced a high probability of endorsing all trait suppression and trait reappraisal items. Participants in the adaptive regulators class had a moderate to low probability of endorsing trait suppression items and a high probability of endorsing trait reappraisal items, with the exception of ERQ1 (reappraising to increase positive emotions) which evidenced a near-high probability (0.57). Conversely, participants in the maladaptive regulators class had a very high probability of endorsing trait suppression items (all >0.8) and varied probability of endorsing trait reappraisal items. For participants in the maladaptive regulators class, the probability of endorsing trait reappraisal items ranged from a very low probability across the majority of the reappraisal items (≤0.05) and a high probability for two of the reappraisal items (ERQ1: ‘When I want to feel more positive emotion (such as joy or amusement), I change what I’m thinking about’ and ERQ3: ‘When I want to feel less negative emotion (such as sadness or anger), I change what I’m thinking about’).

Table 4.

Conditional probabilities for habitual suppression and reappraisal items from the three-class solution.

| High regulators Class (55.7%) | Adaptive regulators Class (23.6%) | Maladaptive regulators Class (20.6%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| There are some things I prefer not to think about. | 0.92 | 0.50 | 0.85 |

| There are things that I try not to think about. | 1.00 | 0.11 | 0.81 |

| Sometimes I really wish I could stop thinking. | 0.92 | 0.34 | 0.87 |

| I have thoughts that I try to avoid. | 0.98 | 0.27 | 0.92 |

| There are many thoughts that I have that I don’t tell anyone. | 0.79 | 0.30 | 0.87 |

| When I want to feel more positive emotion (such as joy or amusement), I change what I’m thinking about. | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.66 |

| When I want to feel less negative emotion (such as sadness or anger), I change what I’m thinking about. | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.65 |

| When I’m faced with a stressful situation, I make myself think about it in a way that helps me stay calm. | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.05 |

| When I want to feel more positive emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation | 0.90 | 0.68 | 0.00 |

| I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in. | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.00 |

| When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation | 0.98 | 0.75 | 0.00 |

3.2.2. Associations between class membership, participant characteristics, trauma exposure, PTSD and emotion dysregulation

The results for the univariate multinomial regression analyses used to investigate the association between class membership, age, gender, trauma exposure, PTSD and emotion regulation difficulties are presented in Table 5. The mean or frequency of each predictor variable according to class are presented in Table 6.

Table 5.

Associations between class membership, age, gender, trauma exposure, PTSD and ER difficulties.

| Est | SE | Odds Ratio | p-value | 95% CI Low | 95% CI High | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive regulators vs High regulators | ||||||

| Age | −0.033 | 0.025 | 0.968 | 0.187 | 0.921 | 1.016 |

| Gender | −0.250 | 0.626 | 0.779 | 0.689 | 0.228 | 2.656 |

| Trauma | 0.216 | 0.092 | 1.241 | 0.019 | 1.036 | 1.486 |

| PTSD diagnosis | 0.515 | 0.683 | 0.450 | 0.450 | 0.439 | 6.383 |

| PTSD severity | 0.042 | 0.023 | 1.043 | 0.071 | 0.997 | 1.091 |

| Emotion regulation difficulties | 0.099 | 0.090 | 1.104 | 0.267 | 0.926 | 1.317 |

| Adaptive regulators vs Maladaptive regulators | ||||||

| Age | −0.022 | 0.037 | 0.978 | 0.545 | 0.910 | 1.052 |

| Gender | 1.018 | 0.714 | 2.768 | 0.154 | 0.683 | 11.217 |

| Trauma | 0.153 | 0.109 | 1.165 | 0.160 | 0.941 | 1.443 |

| PTSD diagnosis | 0.389 | 0.806 | 1.476 | 0.630 | 0.304 | 7.162 |

| PTSD severity | 0.075 | 0.030 | 1.078 | 0.012 | 1.016 | 1.143 |

| Emotion regulation difficulties | 0.201 | 0.100 | 1.223 | 0.043 | 1.005 | 1.487 |

| High regulators vs Maladaptive regulators | ||||||

| Age | 0.011 | 0.034 | 1.011 | 0.755 | 0.946 | 1.081 |

| Gender | 1.268 | 0.580 | 3.554 | 0.029 | 1.140 | 11.076 |

| Trauma | −0.064 | 0.085 | 0.938 | 0.456 | 0.794 | 1.108 |

| PTSD diagnosis | −0.127 | 0.614 | 0.881 | 0.837 | 0.264 | 2.934 |

| PTSD severity | 0.034 | 0.022 | 1.035 | 0.126 | 0.991 | 1.080 |

| Emotion regulation difficulties | 0.102 | 0.057 | 1.107 | 0.072 | 0.990 | 1.238 |

PTSD diagnosis measured whether a participant met full DSM-5 criteria for PTSD, as assessed by the PSSI. PTSD severity reflected the total number of DSM-5 PTSD symptoms each participant endorsed.

Table 6.

Rates of age, gender, trauma exposure, PTSD and ER difficulties according to class.

| M (SD) or n | High Regulators (n = 53) |

Adaptive regulators (n = 19) |

Maladaptive regulators (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 33.77 (9.204) | 36.79 (8.515) | 34.67 (12.362) |

| Gender | 39 males, 14 females | 13 males, 6 females | 8 males, 10 females |

| Trauma | 9.38 (3.033) | 7.00 (4.069) | 8.72 (3.627) |

| PTSD diagnosis | 16 met diagnosis | 2 met diagnosis | 7 met diagnosis |

| PTSD severity | 22.64 (13.478) | 15.42 (14.108) | 29.17 (15.474) |

| Emotion regulation difficulties | 14.19 (4.336) | 12.60 (4.083) | 16.37 (4.941) |

PTSD diagnosis measured whether a participant met full DSM-5 criteria for PTSD, as assessed by the PSSI. PTSD severity reflected the total number of DSM-5 PTSD symptoms that a participant endorsed.

3.2.2.1. Participant characteristics

There were no significant differences in age between any of the classes. Participants in the maladaptive regulators class were significantly more likely to be female than participants in the adaptive regulators class.

3.2.2.2. Trauma exposure

Participants in the high regulators class had been exposed to significantly more PTEs than participants in the adaptive regulators class.

3.2.2.3. PTSD and emotion dysregulation

There were no significant differences in likelihood of PTSD diagnosis between any of the classes. However, participants in the maladaptive regulators class had significantly more PTSD symptoms than participants in the adaptive regulators class. Similarly, participants in the maladaptive regulators class has significantly greater difficulties with emotion regulation than participants in the adaptive regulators class.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, the current study was the first to investigate patterns of ER among refugees. Three distinct classes of ER strategies emerged that were consistent with our hypotheses, each characterized by differing levels of trait suppression and trait reappraisal, namely a high regulators class (high levels of both trait suppression and trait reappraisal), an adaptive regulators class (moderate levels of trait suppression and high levels of trait reappraisal), and a maladaptive regulators class (high trait suppression but low trait reappraisal). Of interest, the findings of the present study, as well as that of past research, point to the existence of a class of individuals who routinely use multiple ER strategies, which include both putatively adaptive and putatively maladaptive strategies (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2014; Lougheed & Hollenstein, 2012). Additionally, the emergence of both adaptive and maladaptive regulator classes aligns with past research employing similar methods of analysis (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2014; Lougheed & Hollenstein, 2012), and suggests that a sub-class of the population show a dominant preference for a particular ER strategy to manage daily stressors. As such, our LCA demonstrated heterogeneity in habitual ER behaviours among refugees that were broadly consistent with ER profiles observed among western university and community samples.

However, contrary to our hypotheses and Dixon-Gordon et al.’s (2014) findings, a low regulators class did not emerge in our sample. Indeed, no class that included consistently low levels of trait suppression emerged. This divergent result may be owing to the sample characteristics of the present study. Compared to the predominantly Caucasian undergraduate students who evidenced low levels of psychopathology in Dixon-Gorden et al.’s study, our study was conducted with a culturally-diverse group of refugees with high rates of PTSD. This may indicate the diffuse use of emotional suppression among trauma-exposed refugees, perhaps owing to high levels of reported trauma exposure and/or a predominant cultural preference. Although no study has examined these possibilities, Aldao et al. (2010) found that suppression was widely employed by individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Moreover, culture has been shown to mediate the selection and efficacy of ER strategies. For instance, Novin, Banerjee, Dadkhah, and Rieffe (2009) found a stronger preference for expressive suppression among Iranian children, compared to Dutch children. As such, future research comparing habitual ER profiles among non-western populations, comprising both trauma-exposed and non-trauma-exposed individuals, might help disentangle these hypotheses.

The current study was also the first to explore associations between ER repertoires and trauma exposure, psychopathology and ER difficulties among refugees. As expected, individuals in the maladaptive regulators class had significantly more PTSD symptoms and ER difficulties compared to those in the adaptive regulators class. Importantly, this difference was not attributable to differing levels of trauma exposure, as these two groups did not differ in terms of exposure to PTEs. Instead, this result suggests that habitually using suppression, and largely overlooking reappraisal as an ER strategy, is associated with symptoms of psychopathology. Additionally, individuals in the maladaptive regulators class were more likely to be female, compared to the adaptive regulators class, which is not unexpected given robust evidence that women are at an increased risk of developing PTSD following trauma exposure, compared to men (Breslau, Davis, Andreski, Peterson, & Schultz, 1997).

Additionally, the high regulators class reported significantly greater exposure to PTEs than the adaptive regulators class. An explanation for this result may be that the high regulators were experiencing higher levels of distress, which thus prompted frequent use of multiple ER strategies in an effort to down-regulate this affect. Indeed, this account is partially supported by a trend towards greater PTSD symptoms among high regulators, compared to adaptive regulators. Moreover, Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema (2012) found that participants who experienced greater negative affect while watching an emotionally charged video subsequently implemented more ER strategies. Alternatively, the emergence of a high regulators class, and its association with a greater variety of traumatic experiences, might speak to the long-term impact of diverse past traumatisation on an individuals’ contemporary approaches to ER. For instance, it may be the case that those who have experienced more types of prior traumas are more likely to habitually preference the use of multiple ER strategies. Although no study has examined this possibility, it seems intuitive that exposure to a wide variety of prior traumatic experiences would likely require the use of a diverse range of ER strategies to manage affect in these different contexts, that, over-time, might develop into a habitual response to stressors. Considering this, further research is merited to better understand how individual differences in refugee experiences, particularly heterogeneous trauma backgrounds, are associated with patterns of habitual ER use. Finally, cultural differences might also be a factor in this result. Although research among western countries has found the use of suppression to be inversely related to the use of reappraisal, Matsumoto, Seung Hee, and Fontaine (2008) found a positive correlation between the use of suppression and reappraisal among participants from collectivist cultures. This finding suggests that while individualistic cultures may show a preference for using one or the other strategy, collectivist cultures may habitually employ both strategies. However, replication of the current study’s findings among other collectivist samples would be required to confirm this hypothesis.

It was interesting to note that there was little differentiation between the three classes across two of the reappraisal items. Instead, individuals from all classes, including the maladaptive regulators class, exhibited a high likelihood of endorsing: ‘When I want to feel more positive emotion (such as joy or amusement), I change what I’m thinking about’ and ‘When I want to feel less negative emotion (such as sadness or anger), I change what I’m thinking about’. Upon closer inspection of these items, particularly in comparison to the other reappraisal items, it is possible that participants may have interpreted these strategies as forms of distraction (i.e. attentional deployment away from the emotion-eliciting stimulus) rather than examples of reappraisal (i.e. cognitive change where elements of the emotion-eliciting stimulus are reframed to change one’s affect). As such, this finding might suggest that distraction is a widely used strategy among traumatized refugees. However, this explanation is only speculative, as no study has examined the use of distraction among refugees. As such, it would be beneficial for future research to explore this possibility, as it may be the case that distraction is just diffusely used among all populations.

Several limitations are worth noting. First, the current study was conducted with a small sample (N = 93) of refugees and it is possible that we did not have sufficient statistical power to detect important differences between the classes nor identify classes with lower probabilities, which could emerge as relevant in larger samples. Moreover, this small sample size did not allow for the simultaneous examination of predictors. Consequently, future research would benefit from assessing ER strategies among larger samples. Second, only two ER strategies were assessed: trait reappraisal and trait suppression. Although both highly relevant to understanding the development of traumatic stress, a more comprehensive understanding of habitual ER repertoires would be gained by incorporating additional theoretically relevant ER strategies into future studies. Third, as the study employed a cross-sectional design, it was not possible to make causal inferences. As such, one cannot determine whether high psychopathology among maladaptive regulators, for instance, was the result of their particular ER repertoire, or whether this relationship existed in the opposite direction, or indeed, was bi-directional. To this end, longitudinal research would greatly aid in clarifying the direction of these relationships. Finally, as our sample comprised individuals from a diversity of cultural backgrounds, it is possible that cultural differences within a specific group may have been masked. Although all participants were members of collectivist cultures, future research might benefit from sampling from a single cultural group to minimize variations in ER styles that might be the result of cultural differences. Also, the proportion of refugees from Iran in our sample was high (53.8%), which may have influenced the results. Owing to the small sample size of the current study, it was not feasible to explore whether participant’s country of origin predicted their ER style. However, such investigations are important to advancing our understanding of the influence of culture on ER, and thus constitute a worthwhile avenue for future research.

Of clinical relevance, the findings of the current study provide preliminary insights into the association between ER and psychopathology among traumatized refugees. The better psychological functioning of individuals in the adaptive regulators class suggest that this pattern of habitual ER may be a desirable goal in therapeutic interventions with refugees. Given the fact that the majority of our sample fell into the high regulators class, it appears that most refugees already have both putatively adaptive and maladaptive ER strategies in their daily repertoire. If so, it may be the case that time spent training individuals in the use of adaptive ER techniques could be better spent in helping individuals to instead develop their capacity to make adaptive ER choices, such that individuals are able to select the most appropriate ER strategy from their existing repertoire to meet the specific situational demands of each context. Finally, although speculative, our findings suggest that the way refugees cope with contemporary stressors may be related to their on-going experience of traumatic stress. If so, it may be beneficial for frontline trauma-focused treatments to not only focus on processing prior traumatic experiences, but also consider the role of contemporary ER approaches to coping with daily stressors. As such, interventions that target both PTSD symptoms and ER difficulties, such as the Skills Training in Affect and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR) treatment model (Cloitre, 2006), may be especially helpful for traumatized refugees. Equally, a multi-disciplinary approach to treatment that includes the provision of case management could aid refugees in addressing difficulties associated with both past and present stressors.

In conclusion, the current study was the first to identify distinct ER profiles among traumatized refugees. Heterogeneity in the habitual ER styles of refugees fell into three classes, describing high regulators, adaptive regulators and maladaptive regulators. While low trait reappraisal combined with high trait suppression (maladaptive regulators) conferred the highest levels of PTSD symptoms, levels of PTSD among high regulators fell in between the other two classes. Instead, the high regulators class were most strongly linked to exposure to more types of PTEs. Our findings demonstrate the importance of using person-centred methodologies to better understand the links between ER, traumatization and psychopathology among refugees. Moreover, the results of our study suggest that ER may be a viable mechanism of change in psychological interventions targeted at this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all participants for their contribution in this study, as well as the refugee and asylum-seeker services in Sydney for providing assistance with recruitment for this study.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aldao A., & Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2012). The influence of context on the implementation of adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(7–8), 493–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A., & Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2013). One versus many: Capturing the use of multiple emotion regulation strategies in response to an emotion-eliciting stimulus. Cognition & Emotion, 27(4), 753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A., Nolen-Hoeksema S., & Schweizer S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altin M., & Gencöz T. (2009). Psychopathological correlates and psychometric properties of the white bear suppression inventory in a Turkish sample. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- APA (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, Virginia: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T., & Muthén B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using M plus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 1–13.31360054 [Google Scholar]

- Bogic M., Njoku A., & Priebe S. (2015). Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights, 15, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N., Davis G. C., Andreski P., Peterson E. L., & Schultz L. R. (1997). Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 54(11), 1044–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M. (2006). Treating survivors of childhood abuse: Psychotherapy for the interrupted life. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon K. L., Aldao A., & De Los Reyes A. (2014). Repertoires of emotion regulation: A person-centered approach to assessing emotion regulation strategies and links to psychopathology. Cognition and Emotion, 29(7), 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolan E. L., Bryant R. A., Liddell B. J., & Nickerson A. (2017). The conceptualization of emotion regulation difficulties, and its association with posttraumatic stress symptoms in traumatized refugees. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 50, 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A., & Clark D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E. B., Riggs D. S., Dancu C. V., & Rothbaum B. O. (1993). Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post‐traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(4), 459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy I. R., Nickerson A., Litz B. T., & Marmar C. R. (2013). Patterns of lifetime PTSD comorbidity: A latent class analysis. Depress Anxiety, 30(5), 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz K. L., & Roemer L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J. (2014). Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J., & John O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J., & Levenson R. W. (1997). Hiding feelings: The acute effects of inhibiting negative and positive emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(1), 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höping W., & de Jong-Meyer R. (2003). Differentiating unwanted intrusive thoughts from thought suppression: What does the White Bear Suppression Inventory measure? Personality and Individual Differences, 34(6), 1049–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Koch T., Liedl A., & Ehring T. (2019). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in Afghan refugees. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. doi: 10.1037/tra0000489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lougheed J. P., & Hollenstein T. (2012). A limited repertoire of emotion regulation strategies is associated with internalizing problems in adolescence. Social Development, 21(4), 704–721. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D., Seung Hee Y., & Fontaine J. (2008). Mapping expressive differences around the world: The relationship between emotional display rules and individualism versus collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39(1), 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Megreya A., Latzman R., Al-Emadi A., & Al-Attiyah A. (2018). An integrative model of emotion regulation and associations with positive and negative affectivity across four Arabic speaking countries and the USA. Motivation and Emotion, 42(4), 566–575. [Google Scholar]

- Mollica R. F., Caspi-Yavin Y., Bollini P., Truong T., Tor S., & Lavelle J. (1992). The harvard trauma questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 53(5), 447–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P., Merckelbach H., & Horselenberg R. (1996). Individual differences in thought suppression. The White Bear Suppression Inventory: Factor structure, reliability, validity and correlates. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(5–6), 501–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L. K., & Muthen B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson A., Bryant R. A., Schnyder U., Schick M., Mueller J., & Morina N. (2015). Emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between trauma exposure, post-migration living difficulties and psychological outcomes in traumatized refugees. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson A., Garber B., Ahmed O., Asnaani A., Cheung J., Hofmann S. G., … Pajak R. (2016). Emotional suppression in torture survivors: Relationship to posttraumatic stress symptoms and trauma-related negative affect. Psychiatry Research, 242, 233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson A., Garber B., Liddell B. J., Litz B. T., Hofmann S. G., Asnaani A., … Bryant R. A. (2017). Impact of cognitive reappraisal on negative affect, heart rate, and intrusive memories in traumatized refugees. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(3), 497–512. [Google Scholar]

- Novin S., Banerjee R., Dadkhah A., & Rieffe C. (2009). Self-reported use of emotional display rules in the Netherlands and Iran: Evidence for sociocultural influence. Social Development, 18(2), 397–411. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer A., & Elbert T. (2011). PTSD, depression and anxiety among former abductees in Northern Uganda. Conflict and Health, 5(1), 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR (2018). Global trends in forced displacement in 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: Retrieved from http://www.humansecuritybrief.info/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Victor S., & Klonsky E. (2016). Validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS-18) in five samples. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(4), 582–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner D. M., & Zanakos S. (1994). Chronic thought suppression. Journal of Personality, 62(4), 615–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2017). Process of translation and adaption of instruments. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- WHO (2017). Process of translation and adaption of instruments. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.