Abstract

The triple-negative phenotype is the most prevalent form of human breast cancer worldwide and is characterized by poor survival, high aggressiveness, and recurrence. Microvesicles (MV) are shredded plasma membrane components and critically mediate cell–cell communication, but can also induce cancer proliferation and metastasis. Previous studies have revealed that protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) contributes significantly to human triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) progression by releasing nano-size MV and promoting cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. MV isolated from highly aggressive human TNBC cells impart metastatic potential to nonmetastatic cells. Over-expression of microRNA221 (miR221) has also been reported to enhance the metastatic potential of human TNBC, but miR221's relationship to PAR2-induced MV is unclear. Here, using isolated MV, immunoblotting, quantitative RT-PCR, FACS analysis, and enzymatic assays, we show that miR221 is translocated via human TNBC-derived MV, which upon fusion with recipient cells, enhance their proliferation, survival, and metastasis both in vitro and in vivo by inducing the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Administration of anti-miR221 significantly impaired MV-induced expression of the mesenchymal markers Snail, Slug, N-cadherin, and vimentin in the recipient cells, whereas restoring expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin. We also demonstrate that MV-associated miR221 targets phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) in the recipient cells, followed by AKT Ser/Thr kinase (AKT)/NF-κB activation, which promotes EMT. Moreover, elevated miR221 levels in MV derived from human TNBC patients' blood could induce cell proliferation and metastasis in recipient cells. In summary, miR221 transfer from TNBC cells via PAR2-derived MV induces EMT and enhances the malignant potential of recipient cells.

Keywords: metastasis, microRNA (miRNA), proliferation, post-transcriptional regulation, breast cancer, anti-apoptosis, microRNA221, microvesicles, oncogenic miR (OncomiR), protease-activated receptor 2

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC)3 is the most common cancer diagnosed among women in United States and considered to be the second leading cause of cancer-related death of women worldwide (1). Among all, the triple-negative BC (TNBC) phenotype has the worst prognosis due to its heterogeneity and higher likelihood to spread or recur (2). The absence of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 in TNBC cells makes it more aggressive and challenging to treat with conventional hormonal or drug therapy (3).

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), secreted by tumor cells contribute immensely toward the propagation of cancerous properties by transporting bioactive protein, lipid, and nucleic acid molecules (4). EVs comprise of “microvesicles” (MV; also called “ectosomes” or “microparticles”), generated by plasma membrane outward budding (5) and exosomes, which are of endocytic origin (6). MV are larger bodies with a diameter of 100–1000 nm unlike exosomes, which have a smaller diameter range (50–80 nm) (7). EVs are transported via body fluids including urine, blood, synovial fluid, saliva and even are found in interstitial spaces between cells (8, 9). Previous studies have revealed that MV from human TNBC cells are capable of inducing migration and invasion to otherwise nonmetastatic BC cells (10, 11).

Protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2), a unique class of the seven transmembrane G-protein–coupled receptor family is encoded by the F2RL1 gene in humans (12). Tissue factor (TF) in complex with factor VIIa (FVIIa) activates PAR2 via proteolytic cleavage at the N terminus of the receptor thereby inducing various cellular responses (13). Trypsin also activates PAR2 (14). Recent evidences suggest that TF and PAR2 are over-expressed in human TNBC (15, 16) and PAR2 activation induces human TNBC metastasis and proliferation (17). TF-FVIIa–mediated PAR2 cleavage activates AKT/glycogen synthase kinase 3β axis followed by β-catenin accumulation to induce metastasis of human TNBC cells (18). PAR2-driven AKT/NF-κB activation also promotes human TNBC cell migration and invasion via matrix metalloprotease-2 (MMP-2) induction (19). Previously, we have explored that PAR2 induction not only promotes human TNBC progression but also induces the release of MV with metastatic potential from human TNBC cells (10, 11).

MicroRNAs (miRs) are small, noncoding RNA molecules that function in RNA silencing or post-transcriptional gene regulation (20). Alterations in various oncogenic miRs (OncomiRs) expression have been associated with tumor progression including metastasis, angiogenesis, anti-apoptosis etc. (20). One such oncomiR, miR221 is over-expressed in human TNBC (21). Previous studies have demonstrated that miR221 reduces epithelial marker, E-cadherin expression to promote migration and invasion of nonmetastatic MCF7 cells via the induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (22). miR221 is also associated with human BC cell proliferation (23) and impedes the rate of apoptosis (24). miR221 promotes EMT via up-regulating mesenchymal markers N-cadherin, vimentin etc. (25). PTEN, a well-known target of miR221 in MCF7, which activates the AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway helps in the propagation of BC stem cells (26). Here, we demonstrate that PAR2 activation leads to MV generation from human TNBC cells, MDAMB231. The fusion of miR221-enriched, MDAMB231-MV with the recipient cells results in the down-regulation of PTEN followed by AKT/NF-κB activation. This leads to the up-regulation of EMT-transcription factors (EMT-TFs) Snail, Slug, and the down-regulation of epithelial marker, E-cadherin leading to enhanced proliferation, migration, and invasion of the recipient cells also imparting them resistance against anti-cancer drug, cisplatin. Targeting miR221 could be a potential therapeutic approach to prevent TNBC-derived MV-induced EMT thereby aiding in the disease prognosis.

Results

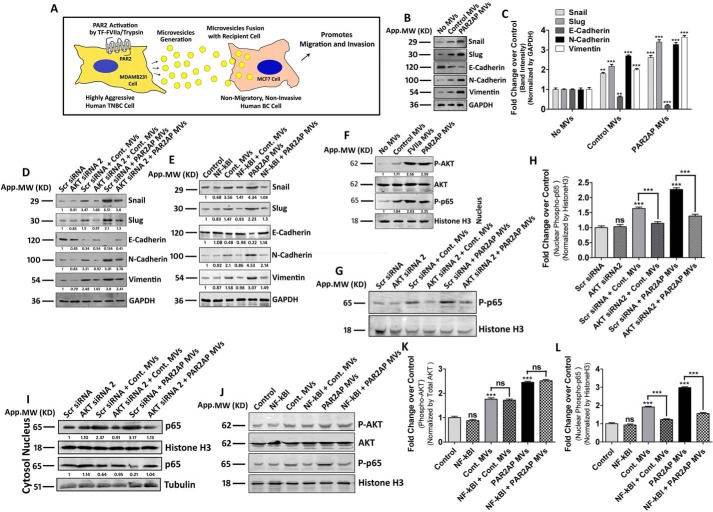

MV, generated from MDAMB231 induce EMT in MCF7 via AKT/NF-κB pathway

Based on both in vitro and in vivo observations, we and several other groups have already established that TF and PAR2 are over-expressed in highly aggressive breast cancer cells (10, 16, 27, 28). In our previous investigations (11), we have demonstrated that PAR2 activation by TF-FVIIa or trypsin leads to pro-metastatic MV generation from the human TNBC cell, MDAMB231, which has also been represented here as shown in Fig. 1A. Our previous results depict that PAR2 activation in TNBC promotes enhanced cell migration and invasion (18, 19), which are hallmarks of EMT (29, 30), leading us to investigate whether incorporation of PAR2-activated MDAMB231-derived MV into MCF7 induces EMT in MCF7. To examine this, the above mentioned MV were incubated with MCF7 and the expression of EMT markers was analyzed. Both our real-time PCR (Fig. S1A) and Western blotting data (Fig. 1, B and C) showed that these MV significantly up-regulated the expression of EMT-TFs, Snail, Slug, and mesenchymal markers, N-cadherin and vimentin, whereas down-regulated the epithelial marker, E-cadherin in MCF7. In agreement with the EMT markers we also observed a characteristic altered morphology of MV-fused MCF7 cells (Fig. S1B). Next, we investigated the underlying signaling mechanism in the regulation of EMT by MV.

Figure 1.

MDAMB231-derived MV induce EMT in MCF7 cells depending on AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway. A, schematic representation depicting that TF-FVIIa or trypsin-mediated PAR2 cleavage leads to the generation of MV from highly aggressive human TNBC cells, MDAMB231. These MV, upon fusion with nonmetastatic MCF7 cells augment the metastatic potential by virtue of increasing cell migration and invasion. B, MV, collected from both PAR2-activated as well as control MDAMB231 cells, were incubated with MCF7 and after ∼16 h the expression profiling of various EMT-related genes was performed by Western blotting. Band intensities were measured by ImageJ, and C, quantified by GraphPad Prism5, which demonstrates that the mesenchymal markers, Snail, Slug, N-cadherin, and vimentin were significantly up-regulated, whereas the epithelial marker, E-cadherin was remarkably down-regulated in MCF7 after MV fusion. MCF7 cells were treated with D, Scrambled or AKT siRNA2 (100 nm) or E, NF-κBI (10 μm) followed by fusion of MDAMB231-derived MV, and the expression of EMT markers was analyzed by Western blotting, which suggests that perturbing either AKT activation of nuclear translocation of NF-κB significantly attenuates the MV-induced EMT in MCF7. F, both AKT phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of phospho-p65 (NF-κB subunit) was monitored in MCF7 cells upon treatment of MDAMB231-MV (control and PAR2-activated cell-derived) by Western blotting. G and H, MCF7 cells were pre-treated with AKT siRNA2 followed by the addition of MDAMB231-derived MV (both control and PAR2-activated) and the nuclear phospho-p65 level was analyzed by Western blotting, which demonstrates that the knock-down of AKT significantly decreases MV-induced nuclear translocation of phospho-p65. I, total p65 level was also monitored in AKT silenced by both nuclear as well as cytosolic fractions of MV (control and PAR2-activated MDAMB231-derived)–fused MCF7 alongside control, which shows that MV-induced p65 translocation from the cytosol to nucleus is getting diminished upon the knock-down of AKT. Again, MCF7 were pre-treated with NF-κBI followed by the fusion of MDAMB231-MV, and J and K, AKT phosphorylation, as well as J and L, nuclear phospho-p65 was monitored by Western blotting. The introduction of NF-κBI does not alter MDAMB231-MV–induced activation of AKT but rather interferes with nuclear translocation of phospho-p65.

As AKT and NF-κB play pivotal roles in promoting EMT (31, 32) and we observed activation of PAR2 either by FVIIa or trypsin signals through this AKT/NF-κB axis (19) to guide us to examine whether the same pathway also triggers the induction of EMT in MCF7 by MV. MCF7 cells were pre-treated with either AKT siRNAs (Fig. S1C) or NF-κB inhibitors, followed by the fusion of MDAMB231-MV. The expression of EMT-related genes was analyzed by Western blotting. The data suggest that inhibition of both AKT and NF-κB significantly attenuated MV-induced expression of Snail, Slug, N-cadherin, and vimentin and down-regulation of E-cadherin (Fig. 1, D and E; Fig. S1, D and F). The fusion of MDAMB231-MV also induced AKT activation and nuclear phospho-p65 accumulation in MCF7 cells (Fig. 1F). To rule out the possibility that introduction of AKT siRNA2 or NF-κBI interferes with MV fusion, we challenged MCF7 cells with AKT siRNA2 or NF-κBI followed by MV incubation and analyzed the MV-mediated transport of TF in MCF7 (Fig. S1G). The data indicates that inhibition of AKT or NF-κB did not interfere with MV fusion. To determine the chronology, we knocked-down AKT in MCF7 and analyzed the nuclear phospho-NF-κB/p65 level upon MV treatment (Fig. 1, G and H). Phosphorylation of the p65 subunit is essential for cytoplasmic to nuclear localization of NF-κB/p65 and transcriptional initiation of the downstream target genes (33). The total p65 level was also monitored in both nucleus as well as cytosol during AKT knock-down (Fig. 1I; Fig. S1E). Again, we inhibited NF-κB and analyzed AKT activation upon MV fusion. The data (Fig. 1, J–L; Fig. S1F) suggest that AKT knock-down significantly reduced MV-mediated nuclear translocation of phospho-NF-κB/p65, whereas inhibition of NF-κB had no effect on AKT activation. These results suggest that AKT is the upstream member in the signaling pathway relating to EMT gene regulation. Overall, the data suggest that MV from MDAMB231 cells promote EMT in MCF7 depending on the AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway.

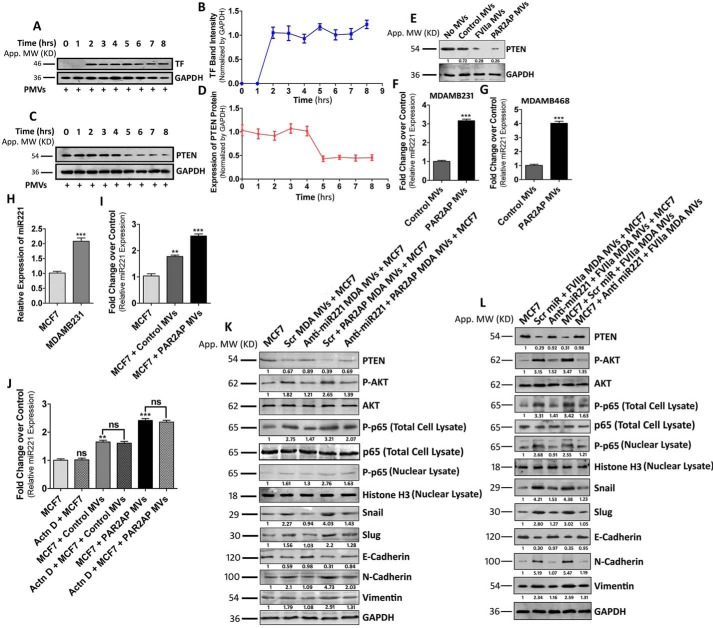

MDAMB231-MV–mediated transfer of miR221 induces EMT in nonaggressive BC cells via the down-regulation of PTEN

Previous studies have revealed that inactivation of PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) results in PI3K/AKT pathway activation (34). PTEN insufficiency was also reported to induce EMT in MCF7 cells via the up-regulation of Snail, Slug, etc. (34). Based on these reports, we proposed that inhibition of PTEN might play a key role in MV-induced EMT in MCF7. We monitored that the fusion of MDAMB231-MV with MCF7 occurs at ∼2 h post-MV incubation with MCF7 (Fig. 2, A and B). Interestingly, the PTEN level in MCF7 subsided significantly at ∼5 h post-MV incubation with MCF7 (Fig. 2, C and D). PTEN down-regulation was also monitored in MCF7 treated with both control as well as PAR2-activated MDAMB231-derived MV (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

MDAMB231-MV–mediated transfer of miR221 induces EMT in MCF7 via the down-regulation of PTEN and activation of the AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway. A, MV were collected from PAR2-activated MDAMB231 cells and incubated with MCF7 for various time points. MV fusion was analyzed upon observing TF band in MV-incorporated MCF cells and B, accordingly a line diagram was plotted that indicates that MV fusion occurs at ∼2 h post-MV incubation with MCF7. C, the level of PTEN was analyzed in MCF7 cells upon fusion of PAR2-activated MDAMB231-derived MV at various time points and D, accordingly the graph was generated, which suggests that the PTEN level goes down significantly at ∼5 h of MV incubation. E, both control as well as PAR2-activated MDAMB231-derived MV were fused with MCF7 and the PTEN level was monitored at 5 h of MV treatment. F, MDAMB231 cells were treated with PAR2AP beside untreated controls and MV were isolated from the cell supernatant after 24 h. miR221 expression in the MV was monitored by the real-time PCR approach. G, miR221 expression was also analyzed in MDAMB468-derived MV (both control and PAR2-activated). miR221 expression was found to be significantly higher in MV derived from PAR2-activated cells. H, relative miR221 expression was analyzed in both MCF7 and MDAMB231 cells, which depict that miR221 expression is significantly higher in MDAMB231 than MCF7. I, MCF7 cells were treated with both control as well as PAR2-activated MDAMB231-derived MV for 3 h followed by the analysis of miR221 level by real-time PCR. The incorporation of MV significantly up-regulated the miR221 level in MCF7 and maximum effect was monitored in a PAR2-activated MV-treated set. J, MCF7 cells were pre-treated with actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) for 8 h followed by the addition of MV. The miR221 level was analyzed in those cells by real-time PCR. The treatment of actinomycin D does not interfere with the level of miR221 in MV-fused MCF7 cells. K and L, MDAMB231 cells were transfected with anti-miR221 beside Scrambled control miR followed by the addition of PAR2AP or FVIIa. MV were isolated and fused with MCF7. Alternatively, MCF7 cells were pre-treated with anti-miR221 alongside Scrambled miR followed by the addition MDAMB231-derived MV. The analysis of PTEN, phospho-AKT, nuclear phospho-p65, Snail, Slug, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin expression in MV-fused MCF7 cells was performed by Western blotting, which indicates that the introduction of anti-miR221 reverses the EMT phenotype induced by MDAMB231-MV.

Earlier, it was reported that PTEN is a target of miR221 in human BC cells (26). Moreover, MV, isolated from PAR2-activated MDAMB231 cells had significantly higher miR221 content than control (Fig. 2F). This is also observed in another TNBC cell line, MDAMB468, where MV of PAR2-activated cells also contained more miR221 (Fig. 2G). Therefore, we investigated whether MV-induced inactivation of PTEN in MCF7 is miR221-dependent. We observed that endogenous miR221 expression was significantly higher in MDAMB231 cells compared with MCF7 (Fig. 2H). The fusion of MDAMB231-MV with MCF7 resulted in an increase of the miR221 level in the recipient cells (Fig. 2I). A similar phenomenon was also observed during the fusion of MDAMB231-derived MV with BT474 cells (Fig. S2A). This increase of miR221 reflects the MV-mediated miR221 transfer but not an induction of miR221's endogenous expression in MCF7, as its level in MV-treated cells was not affected by an RNA polymerase II inhibitor (Fig. 2J). To determine the role of miR221 in promoting MV-mediated EMT in MCF7, we pre-treated MDAMB231 cells with anti-miR221/Scrambled control followed by PAR2AP or FVIIa addition. The harvested MV were incubated with MCF7 cells and the expression of EMT markers in MCF7 was analyzed. Again, MCF7 were pre-treated with anti-miR221 followed by MV addition and expression of EMT markers was determined (Fig. 2, K and L). Similarly, MV generated from MDAMB231 cells after various treatments were also fused with BT474 cells and the expression of EMT markers was analyzed (Fig. S2B). The data suggest that modulation of the EMT markers by MV was significantly negated in the presence of anti-miR221 demonstrating the crucial role of miR221 in the MV-mediated EMT in MCF7 cells. As a whole, the data indicate that MDAMB231-MV–mediated delivery of miR221 promote EMT via the down-regulation of PTEN.

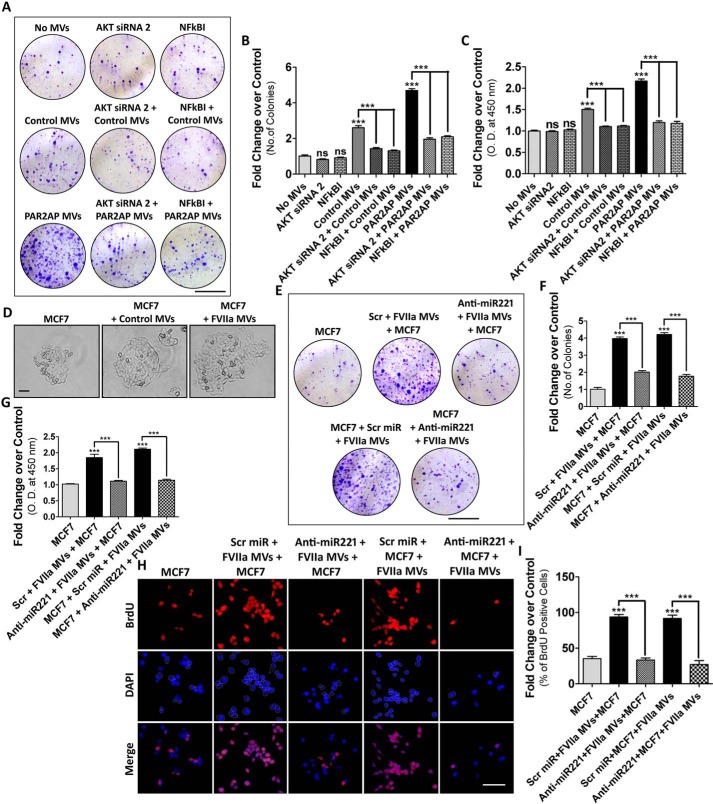

MDAMB231-MV promote miR221-dependent proliferation of recipient cells

Previous studies have demonstrated that AKT plays vital roles in the proliferation of MCF7 cells (35). Again, NF-κB activation is also associated with MCF7 proliferation (36). Earlier reports have revealed that EMT and cell proliferation are inextricably related (37). Hence, we investigated the contribution of AKT or NF-κB on MV-mediated proliferation of MCF-7 cells by colony formation assay and BrdU incorporation assay (Fig. 3, A–C; Fig. S3, A–C). Inhibition of AKT or NF-κB significantly retarded MV-induced proliferation of MCF7 cells. Analysis of the growth of a single MCF7 cell upon fusion with the MV by microscopic imaging suggest that MCF7 proliferates at a faster rate after MV incorporation and maximum effect was monitored when PAR2-activated MDAMB231-MV were fused (Fig. 3D). Because miR221 is well-documented to induce cell proliferation (23), we investigated whether the transfer of miR221 via MV is responsible for recipient MCF7 cell proliferation. MDAMB231 cells were transfected with anti-miR221/Scrambled control followed by FVIIa treatment. MV were incubated with MCF7 and cell proliferation was monitored. Alternatively, MCF7 cells, pre-treated with anti-miR221 were incubated with MDAMB231-MV and the recipient MCF7 proliferation was analyzed (Fig. 3, E–I). Again, these MDAMB231-derived MV were fused with BT474 cells and the proliferation was analyzed by BrdU incorporation assay (Fig. S3D). Results suggest that the induction of recipient cell proliferation by MDAMB231-MV was significantly retarded upon administration of anti-miR221. Overall, the data manifest that MDAMB231-MV induce cell proliferation via miR221 transfer depending on AKT/NF-κB pathway.

Figure 3.

MDAMB231-MV–mediated transfer of miR221 induces MCF7 cell proliferation in vitro. MCF7 cells were treated with AKT siRNA2 or NF-κBI followed by the incorporation of MDAMB231 cell-derived MV. Recipient MCF7 cell proliferation was analyzed by: A and B, colony formation assay; scale bar 10 mm; and C, BrdU incorporation assay with HRP-tagged secondary antibody, which suggests that the inhibition of AKT or NF-κB significantly reduced MDAMB231-MV–induced proliferation of MCF7. D, imaging of single cell growth of MCF7 upon fusion of MDAMB231-derived MV suggests that the MCF7 growth rate increases remarkably upon fusion with MDAMB231-MV and the maximum effect was observed when PAR2-activated cell-derived MV were incorporated. MDAMB231 cells were transfected with anti-miR221 beside Scrambled control followed by FVIIa treatment. MV were fused with MCF7 cells. Alternatively, MCF7 cells were transfected with anti-mi221 followed by the fusion of MDAMB231-MV. The recipient MCF7 cell proliferation was analyzed by E and F, colony formation assay; scale bar 10 mm; and G–I, BrdU incorporation assay; scale bar 25 μm. Introduction of anti-miR221 significantly reduced MDAMB231-MV–induced MCF7 proliferation.

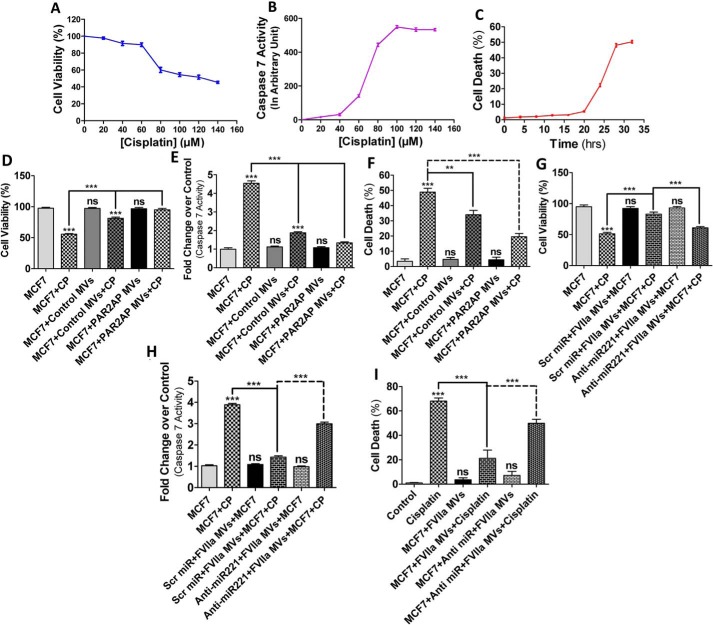

MDAMB231-MV–mediated delivery of miR221 increases cell survival against apoptotic stimuli

EMT is accompanied by the acquisition of resistance against chemotherapeutic drugs (38). We questioned whether MDAMB231-MV impart an anti-apoptotic effect to recipient cells against anti-cancer agents. We challenged MCF7 cells with various concentrations of cisplatin and analyzed cell death by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Fig. 4A). The data indicates that IC50 of cisplatin is 100 μm. Unlike other BC cells, caspase 7 mostly regulates apoptosis in MCF7 (39) as these cells are deficient of caspase 3 (40). Our data showed that caspase 7 exhibits maximum activity at 100 μm cisplatin (Fig. 4B). Flow cytometry data also suggest that maximum DNA fragmentation occurred at 30 h of cisplatin (100 μm) treatment (Fig. 4C; Fig. S4). Next, to determine the effect of MV on MCF7 cellular apoptosis, similar experiments were performed in MV-treated cells and the results depict that fusion of MV with MCF7 cells induces resistance against cisplatin-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4D–F; Fig. S5). Previous studies have revealed that miR221 impedes caspase 7 activity and associated cellular apoptosis (41). Knock-down of miR221 was shown to promote cisplatin-induced apoptosis of human BC cells (24). We tested whether MDAMB231-MV–mediated transfer of miR221 is responsible for this cisplatin resistance in MCF7. MV from anti-miR221/Scrambled control pre-transfected, FVIIa-treated MDAMB231 cells were incubated with MCF7 cells followed by treatment with cisplatin. Cell death and caspase 7 activity were analyzed thereafter (Fig. 4, G–I; Fig. S6). Similarly, these MV were also fused with BT474 cells followed by cisplatin exposure and cell death was monitored by MTT assay (Fig. S7). The results showed that FVIIar-treated MDAMB231-MV impart greater cellular resistance against cisplatin and that the inhibition of miR221 negates the effect suggesting that miR221 is crucial for MV-induced resistance of MCF7 against cisplatin. Taken together, the data show that miR221, transported via MDAMB231-MV, induces recipient cell survival against apoptotic agents.

Figure 4.

MDAMB231 cell-derived MV confer resistance against cisplatin-induced apoptosis of MCF7. A, MCF7 cells were exposed to various concentrations of cisplatin for 30 h and cell death was monitored by the MTT assay and the IC50 of cisplatin on MCF7 was shown to be 100 μm. B, the degree of apoptosis induced by various concentrations of cisplatin was also measured by a caspase 7 activity assay, which also indicates that maximum caspase 7 activity was monitored at 100 μm cisplatin. C, MCF7 cells were exposed to cisplatin (100 μm) for various time points and apoptosis was monitored by a FACS analyzer as mentioned briefly under “Experimental procedures,” which indicates that maximum cell death was observed at ∼30 h of cisplatin exposure. D–F, MDAMB231 cell-derived MV (both control, as well as PAR2AP-treated) were fused with MCF7 cells followed by the addition of cisplatin (100 μm). Cell viability, caspase 7 activity, and the degree of apoptosis by FACS were measured thereafter, which demonstrates that MDAMB231-MV rescued MCF7 cells from cisplatin-induced apoptosis. G–I, MDAMB231 cells were pre-transfected with anti-miR221 followed by FVIIa addition and MV isolated were introduced into MCF7 cells. The recipient MCF7 cell death was monitored upon challenging the cells with cisplatin and the data indicates that anti-miR221 introduction diminished the anti-apoptotic effect of MDAMB231-MV on MCF7.

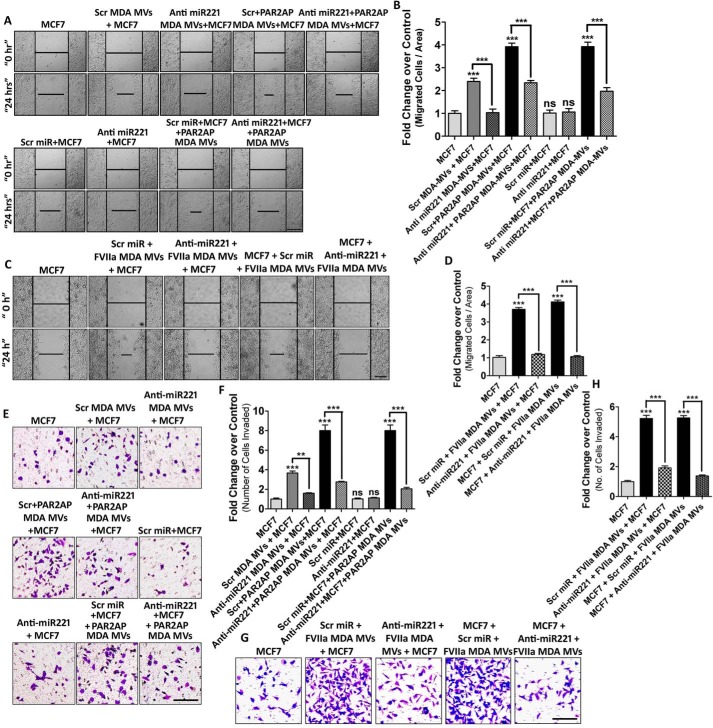

MDAMB231-MV–mediated transfer of miR221 induces cell migration and invasion in vitro

Migration and invasion is the trademark of EMT where the cells lose polarity and cell–cell adhesion to achieve a mesenchymal phenotype (42). Earlier, we observed the active participation of AKT and NF-κB in promoting MV-induced EMT in MCF7. To determine the contribution of AKT/NF-κB in inducing MV-mediated MCF7 migration and invasion, MCF7 cells were pre-treated with AKT siRNAs or NF-κB inhibitors followed by fusion with MDAMB231-MV (both control and PAR2-activated MDAMB231-MV). The migratory property of recipient MCF7 was analyzed by a wound-healing assay (Figs. S8 and S9). The data suggest that inhibition of the AKT/NF-κB pathway results in the retardation of MCF7 migration. Next, we investigated the contribution of miR221 in promoting MV-induced MCF7 cell migration. MDAMB231 cells were transfected with anti-miR221/Scrambled control followed by PAR2AP or FVIIa treatment and the isolated MV were incubated with MCF7. Again, MCF7 were pre-treated with anti-miR221 followed by MV addition. MCF7 cell migration was analyzed thereafter (Fig. 5, A–D). The data showed that MV-induced migration of MCF7 was retarded significantly upon introduction of anti-miR221 in either cell lines, suggesting an important role of miR221 in inducing recipient cell migration.

Figure 5.

MDAMB231-MV–mediated transfer of miR221 promotes AKT/NF-κB-dependent migration and invasion of nonmetastatic MCF7 cells. A–D, to determine the role of miR221 transported from MDAMB231 to MCF7 cells via MV in inducing MCF7 cell migration, MDAMB231 cells were transfected with anti-miR221 beside Scrambled control miR followed by the addition of PAR2AP or FVIIa. MV were isolated and fused with MCF7. Alternatively, MCF7 cells were pre-transfected with anti-miR221 alongside Scrambled miR followed by the addition MDAMB231-derived MV. The migratory property of these MV-fused MCF7 cells was analyzed thereafter, which indicates that MDAMB231-MV–mediated induction of MCF7 migration was suppressed upon introduction of anti-miR221; scale bar 100 μm. E–H, to understand the contribution of MDAMB231-MV in promoting MCF7 invasion, the donor MDAMB231 cells were transfected with anti-miR221 followed by the addition of PAR2AP or FVIIa. MV were collected and incorporated into MCF7. Alternatively, MCF7 were pre-transfected with anti-miR221 followed by the fusion of MDAMB231-derived MV. MV-fused MCF7 cell invasion was measured by Transwell invasion assay; scale bar 100 μm, as mentioned briefly under “Experimental procedures.” The induction of MCF7 invasion by MDAMB231-MV was repressed upon administration of anti-miR221.

In a similar approach as mentioned above, the role of AKT/NF-κB signaling and miR221 in the invasiveness of the recipient cells was monitored by a Transwell invasion assay. Inhibition of AKT/NF-κB pathway (Figs. S10 and S11) or miR221 (with anti-miR221 introduction) (Fig. 5, E–H) showed a significant reduction in MV-induced invasion of MCF7 cells.

These MDAMB231-derived MV were also incorporated into BT474 cells and the recipient cellular migration (Fig. S12, A and B) and invasion (Fig. S12, C and D) were analyzed. This illustrates that MV, isolated from MDAMB231 cells, induce migration and invasion to the recipient cells in a AKT/NF-κB/miR221-dependent manner.

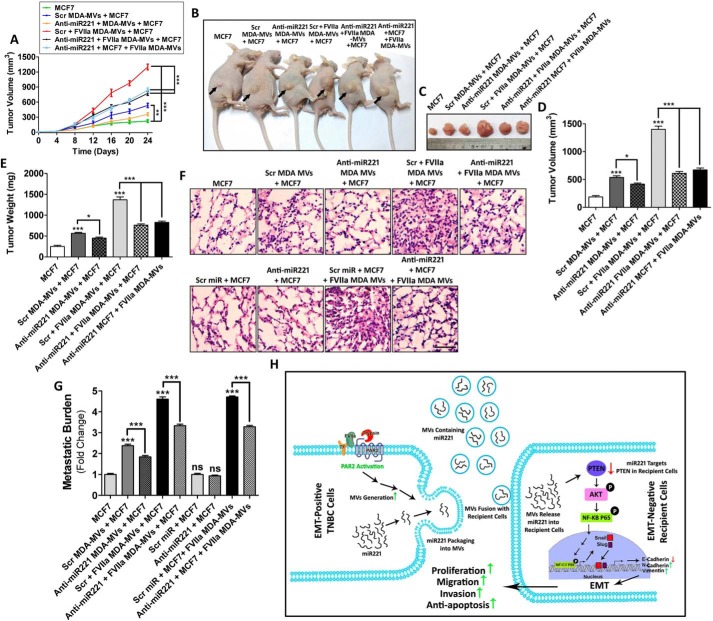

MDAMB231-MV–mediated transfer of miR221 promote MCF7 proliferation and metastasis in vivo

Next, to investigate the contribution of MV-transported miR221, in promoting MCF7 proliferation in vivo, MDAMB231 cells were transfected with anti-miR221/Scrambled control followed by FVIIa treatment and MV were fused with MCF7 cells. Alternatively, MCF7 cells pre-transfected with anti-miR221 were incubated with MDAMB231-MV. MV-fused MCF7 cells were implanted into BALB/c nude mice via subcutaneous injection. After 25 days, mice were euthanized, and tumors were excised. Tumor volume and weight were measured to determine the degree of proliferation. Tumor growth was monitored every day from the day of injection through the 25th day (Fig. 6A). The data indicates that fusion of FVIIa-treated MDAMB231-MV promotes more pronounced MCF7 proliferation than control. Administration of anti-miR221 impaired MV-induced MCF7 proliferation (Fig. 6, B–E). To determine in vivo metastatic potential of MV, MV-fused MCF7 were administered into the mice via tail vein injection. Mice were sacrificed on the 25th day and lungs were harvested and processed to determine MCF7 lung metastatic burden and colonization (Fig. 6, F and G). The data indicate that pre-treatment of MDAMB231 cells with anti-miR221 significantly reduced FVIIa-induced, MV-mediated metastasis of recipient MCF7. Similarly, pre-treatment of MCF7 cells with anti-miR221 followed by MDAMB231-MV fusion also reduced lung metastatic burden of MCF7 than control. The expression of EMT markers was also analyzed in these tumors by Western blotting, which indicates that MDAMB231-MV promotes EMT in MCF7 in vivo, which gets inversed upon administration of anti-miR221 (Fig. S13). Altogether, the data suggest that MV-mediated miR221 transfer promotes proliferation and metastasis of MCF7 in vivo via the induction of EMT (Fig. 6H).

Figure 6.

miR221, transported via MDAMB231-MV, promote proliferation and metastasis of MCF7 in vivo. A, anti-miR221 was transfected into the donor MDAMB231 cells followed by the addition of FVIIa. MV were isolated and fused with MCF7 cells. Alternatively, anti-miR221 was introduced into MCF7 directly prior to the incorporation of FVIIa-treated MDAMB231-MV. Recipient MCF7 cells were introduced into the 6-week-old female BALB/c nude mice via subcutaneous injection (n = 7 in each group). Mice were sacrificed and tumor volume was measured in a day-wise manner up to 25 days. B and C, representative images of tumors at the 25th day, D and E, and after euthanization tumors were excised and tumor volume as well as weight were measured and accordingly comparative graphical analyses were performed. FVIIa-treated, MDAMB231-derived MV promoted MCF7 proliferation in vivo but the introduction of anti-miR221 reversed the effect suggesting that the process depended on miR221. To determine the metastatic potential of MDAMB231-derived MV, MV-fused MCF7 cells (1 × 106) were introduced into 6-week-old female BALB/c nude mice by tail vein injection (n = 7 in each group). After 25 days, mice were euthanized and lungs were harvested. F, a part of the lung was subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining; scale bar 50 μm, whereas G, from the other part genomic DNA, was isolated by phenol-chloroform method. The isolated genomic DNA was subjected to PCR amplification with human-specific HK2 primers as well as 18S rRNA primers by real-time PCR. Relative metastatic burden was quantified accordingly. Similar to the proliferation data, FVIIa-treated, MDAMB231-derived MV also induced miR221-dependent metastasis of MCF7. H, schematic diagram showing that MV, isolated from MDAMB231 upon PAR2 activation induces proliferation, migration, invasion, and anti-apoptosis of MCF7 cells via the transfer of miR221. The activation of PAR2 results in the generation of miR221-laden MV from the human TNBC cell line, MDAMB231. The MV readily fuse with less aggressive MCF7 cells thereby transporting MDAMB231-derived miR221 into MCF7. This leads to the down-regulation of PTEN followed by the activation of AKT and NF-κB/p65, which results in Snail and Slug up-regulation whose ultimate effect is the EMT via minimizing E-cadherin expression, whereas up-regulating N-cadherin and vimentin expression. This ultimately leads to the enhancement of proliferation, migration, and invasion of recipient MCF7 cells while also imparting MCF7 cells resistance against anti-cancer drug, cisplatin.

MV, from the blood of human TNBC patients bear elevated levels of oncogenic miR221 capable of inducing EMT in MCF7

Recently, we showed that human TNBC tissues express PAR2 significantly higher than normal breast tissues (11). Moreover, the MV count was also relatively higher in the blood of such cancer patients (11). It has been reported that miR221 is over-expressed in human BC and is associated with increased malignancy (43). Here, we have observed that MV, isolated from human TNBC patients bear significantly higher miR221 than healthy individuals (Fig. 7A). The fusion of patient-derived MV with MCF7 cells significantly increased the recipient MCF7 miR221 levels (Fig. 7B). To determine the role of these MV-transported miR221 in inducing EMT in MCF7 cells, MCF7 cells were transfected with anti-miR221/Scrambled control followed by treatment with healthy or patient-derived MV. The expression of EMT markers in the recipient MCF7 was analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 7C). The process also seemed to be dependent on the AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway. The data also indicated that unlike normal MV, MV from TNBC patients promote MCF7 cell EMT, proliferation, migration, and invasion in a miR221-dependent manner (Fig. 7, D–F and I–L). Also, patient-derived MV impart MCF7 resistance against the anti-cancer agent, cisplatin depending on miR221 (Fig. 7, G and H). Our in vivo data also demonstrate that administration of anti-miR221 significantly reduced patient MV-induced tumor growth and metastasis as a result of EMT (Fig. 7, M–Q; Fig. S14). In summary, the data show that MV, isolated from the blood of human TNBC patients, induce EMT in MCF7 cells in a PTEN/AKT/NF-κB/miR221-dependent manner thereby imparting enhanced proliferation, metastasis, and chemoresistance.

Figure 7.

MV, isolated from the blood of human TNBC patients bear a significant level of oncogenic miR221 than normal, which is also capable of inducing EMT in MCF7 thereby promoting proliferation, anti-apoptosis, and metastasis. A, MV were isolated from the blood of both normal healthy individuals (n = 30) as well as human TNBC patients (n = 30) and the miR221 level inside these blood-derived MV was estimated by real-time PCR, which shows that the miR221 level inside these patient-derived MV was significantly higher than normal. B, blood-derived MV were fused with MCF7 cells and the miR221 level was analyzed inside these MV-fused MCF7, which indicates that unlike normal, patient-derived MV administration into MCF7 increases the miR221 level in the recipient cells. C, MCF7 cells were transfected with anti-miR221 beside Scrambled control followed by the addition of blood-borne MV. EMT of these MV-fused MCF7 cells was analyzed by measuring the EMT markers by Western blotting, which depicts that patient-derived MV induce miR221-dependent EMT in MCF7 unlike normal MV. MCF7 cells were transfected with anti-miR221 followed by the addition of blood-derived MV (both normal and TNBC patients). Recipient MCF7 cell proliferation was measured as indicated in D and E, colony formation assay as well, as in F, BrdU incorporation assay. Patient-derived MV show a more proliferative effect on MCF7 than normal, which was also dependent on miR221. Again, these recipient MCF7 cells were exposed to cisplatin and the MCF7 cell apoptosis was analyzed by G, MTT assay as well as H, caspase 7 activation assay. Unlike normal MV, patient-derived MV were shown to confer MCF7 resistance against cisplatin, which was diminished upon introduction of anti-miR221. MCF7 cells were transfected with anti-miR221 or Scrambled control followed by the treatment of blood-derived MV (normal and patient). The recipient MCF7, I and J, migration, and K and L, invasion were analyzed by a wound-healing assay and Transwell invasion assay, respectively. Patient-derived MV induced both cell migration and invasion of MCF7 were significantly interrupted upon anti-miR221 introduction. MCF7 cells were transfected with anti-miR221 beside Scrambled control followed by the fusion of blood-borne MV (both normal and TNBC patient). MV-fused MCF7 cells were implanted into mice via subcutaneous injection. After 25 days mice were sacrificed, and M, tumors were excised. N, tumor volume, as well as O, tumor weight, was measured and accordingly a graph was prepared. In another approach, MV-fused MCF7 cells were introduced into mice via tail vein injection. After 25 days, mice were euthanized and lungs were isolated. P, a part of the lung was subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining; scale bar 100 μm, whereas for Q, the other part of the lung metastatic burden of MCF7 was analyzed, as described briefly under “Experimental procedures.” Unlike normal MV, patient-derived MV produce more a proliferative, as well as metastatic effect on MCF7, which was reduced drastically while anti-miR221 was administered.

Discussion

There is growing evidence for the poor survival of patients with aggressive TNBC (44). Effective targeted therapy against TNBC is restricted due to its genomic and molecular heterogeneity (45), early recurrence and higher metastatic potential (46). Earlier studies from others and our group have already revealed that a unique class of seven-transmembrane G-protein–coupled receptor family protein PAR2 signaling is associated with human breast cancer progression and metastasis. FVIIa- and FXa-dependent activation of PAR2 critically regulates human breast cancer cell migration and invasion via the activation of ERK1/2 (47). The activation of PAR2 also induces pro-tumoral cytokine, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) expression in human breast cancer cells, thereby favoring tumor progression (48). Breast tumor growth is suppressed by the inhibition of TF-induced PAR2 activation, and the deficiency in PAR2 delays spontaneous breast cancer development in mice (29). Also, in the recent past, we have revealed that TF-FVIIa or trypsin-mediated cleavage of PAR2 contributes to a great extent to the metastasis of human TNBC cells, MDAMB231 via the induction of MMP-2 (19), or by the accumulation of β-catenin (18). Apart from this, PAR2 activation also promotes proliferation of human BC cells (17) and is associated with tumor survival (49). An increase in cell migration and invasion are the hallmarks of EMT where the cells lose their polarity and cell–cell adhesion to achieve a mesenchymal phenotype (31). EMT is also accompanied by the enhancement of cell proliferation as well as the acquisition of resistance against apoptotic stimuli (39, 40). The activation of PAR2 in hepatocellular carcinoma results in EMT leading to tumor cell proliferation and metastasis (50). No direct evidence to date correlates with PAR2 activation and EMT in breast carcinomas.

The emergence of extracellular vesicles (both MV and exosomes) aids in understanding the metastatic spread of human TNBC extensively. The exposure of human TNBC cells, MDAMB231 to hypoxia, results in the liberation of MV in a Rab22A-dependent manner, which is capable of promoting focal adhesion formation, invasion, and metastasis to the neighboring recipient cells (27). In the recent past, we have shown that activation of PAR2 by coagulation factors induces pro-metastatic MV generation from human TNBC cells (10, 11). The administration of these pro-metastatic MV into a nonmetastatic cell, MCF7, significantly enhances the metastatic potential of the recipient MCF7 cells. This led us to investigate whether these MV are capable of promoting EMT to the recipient cells. Interestingly, we have observed that the MV, generated from PAR2-activated human TNBC cells, promote EMT to nonaggressive BC cells. Furthermore, we have also elucidated the mechanistic details underlying MV-induced EMT.

Up-regulation of EMT-TFs, Snail, and Slug in MCF7 during EMT is mostly dependent on NF-κB (51, 52) and AKT (26). In the present study, we have also deciphered that MV from TNBC induce EMT depending on the AKT/NF-κB-signaling pathway. Knock-down of AKT or arresting nuclear translocation of phospho-NF-κB/p65 significantly reduced MV-induced expression of EMT markers and EMT phenotypes in the recipient cells. Several reports, including our previous one (53), suggest that AKT-mediated activation of NF-κB is essential for various oncogenic transformations. In agreement with this, here we have also noticed that AKT functions upstream of NF-κB in MV-induced EMT of recipient cells. The transfer of oncogenic miRs via tumor cell-secreted MV has been well-established (4). miR221 gets over-expressed in human TNBC (21) and is capable of promoting EMT (22). Again, miR221 targets PTEN in BC cells (26). Here, for the first time, we reveal that MV, generated from human TNBC are laden with miR221, which induce EMT to the recipient cells depending on the PTEN/AKT/NF-κB pathway both in vitro and in vivo. Inconsistent with our in vitro and mice experiments, we have also monitored a similar hostile effect of a human TNBC patient's blood-derived MV toward nonmetastatic recipient cells.

Taken together, the results of the present study indicate that miR221 transfer via coagulation factor-mediated PAR2-derived MV from TNBC produces more adverse effect to the neighboring recipient cells through the induction of EMT. Either prohibiting the TNBC MV-mediated miR221 transfer or restricting the release of MV and their concomitant fusion with the recipient cells could be a potential therapeutic approach to mitigate the degree of tumorigenesis and metastatic dissemination of human TNBC.

Experimental procedures

Human subjects and IRB details

Blood samples of human TNBC patients and normal healthy volunteers (age 40–45 years; n = 30 each) were collected from Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Cancer Research Institute, Kolkata, India. The study and the protocol were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Cancer Research Institute (registration number ECR/286/INST/WB/2013) with prior consent of the patients. All studies on human subjects were performed abiding by the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

Cell culture

Human TNBC lines, MDAMB231, MDAMB468, and nonmetastatic MCF7 were obtained from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco) with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Invitrogen). BT474 cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and insulin (250 μg/ml). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and routinely examined for mycoplasma contamination.

siRNA and anti-miR treatment

Cells were transfected with 100 nm Scrambled/AKT siRNAs (Bioserve Biotechnologies) or Scrambled miR/anti-miR221 (Bioserve Biotechnologies) using LipofectamineTM 2000 (Invitrogen) (Table S1). Following transfection, cells were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h and AKT1 knock-down was verified by Western blotting. AKT siRNA2 showed a better knock-down effect and hence was used for the majority of experiments.

MV isolation

MDAMB231 and MDAMB468 cells, grown in 100-mm dishes to 80% confluence were serum starved for 2 h followed by the stimulation with PAR2-activation peptide (PAR2AP; SLIGKV-NH2; 100 μm; GL Biochem, China) or human recombinant FVIIa (100 nm; Novo-Nordisk). After 24 h, MV were isolated from the culture supernatant by sequential centrifugation as described previously (10). Briefly, the supernatant was centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 min (to remove floating cells or larger debris) followed by 2,500 × g for 15 min (to remove apoptotic bodies or smaller debris), and 10,000 × g for 30 min to collect the MV. MV were washed with 1× PBS and proceeded for further analyses.

MV were isolated from human blood by a centrifugation procedure as mentioned earlier (10). Briefly, blood samples (10 ml each) were collected, cells and platelets were separated by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 15 min following which two separate plasma pools were prepared (normal and patient). The plasma pools were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min (at 4 °C) to collect the blood-borne MV.

Experimental design

Determining the expression of EMT-related genes in the recipient cells after fusion of MDAMB231-MV

MCF7 cells in 35-mm dishes were grown to 80% confluence. MV isolated from MDAMB231 cells were incubated with MCF7 cells for various time points (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 h) and fusion of MV was verified by analyzing MV markers, TF in MCF7 (lacks endogenous TF) by Western blotting. The expression of various EMT-related proteins such as Snail, Slug, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin was analyzed ∼16 h post-MV fusion with the recipient cells by Western blotting.

The role of AKT/NF-κB in MV-induced up-regulation of EMT was analyzed using AKT siRNAs (AKT siRNA1 and AKT siRNA2) (Table S1) or NF-κB inhibitors, NF-κBI (10 μm) and NF-κBI2 (SN50; Calbiochem; 20 μm). The expression of PTEN or phosphorylation of AKT and nuclear phospho-NF-κB/p65 were verified ∼5 h post-MV fusion with MCF7 by Western blotting. Normalization was performed with GAPDH, tubulin, or histone H3 for total, cytosolic, or nuclear fractions, respectively.

Analyzing the effect of miR-221 in promoting MV-induced EMT in the recipient cells

Anti-miR221–transfected MDAMB231-MV were fused with recipient MCF7/BT474 cells, or the recipient cells pre-transfected with anti-miR221 were fused with MDAMB231-MV and expression of various EMT genes or AKT/NF-κB phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blotting. Similarly, MCF7 cells were transfected with anti-miR221/Scrambled control followed by addition of blood-derived MV (normal or patient-derived MV) and EMT gene expression or AKT/NF-κB/p65 phosphorylation was measured by Western blotting.

Wound-healing assay

To determine the contribution of MV in transmitting the migratory property to MCF7 cells, MV (control or PAR2AP-activated cell-derived) were incubated with MCF7 cells for 3 h and a wound-healing assay was performed. The number of cells migrated to the scratched area in a 24-h time frame was counted and quantification was made.

Alternatively, MCF7 cells were treated with AKT siRNAs (48 h) or NF-κBI (1 h) followed by incubation with MDAMB231-MV. Wound-healing assay was performed with these cells to determine the role of AKT/NF-κB in MV-induced MCF7 cell migration.

Again, MDAMB231 cells were treated with Scrambled or anti-miR221 followed by the treatment with PAR2AP or FVIIa. MV were isolated and incubated with MCF7 or BT474 cells and a wound-healing assay was performed to determine the effect of miR221 in MV-induced cell migration. Alternatively, MCF7 were pre-transfected with Scrambled or anti-miR221 and a wound-healing assay was performed to monitor the same. Finally, identical experiments were performed with healthy or TNBC patient-derived MV to examine the contribution of miR221 in inducing MCF7 cell migration.

Transwell invasion assay

Invasion assay with Transwell chambers was performed as mentioned previously (10). To investigate the role MDAMB231-MV in inducing invasion of noninvasive MCF7 cells, both MV populations (control and PAR2AP or FVIIa-treated MDAMB231-MV) were fused with MCF7. MV-fused MCF7 cells in serum-free medium were placed on top of a Transwell membrane (0.8 μm pore size) previously coated with Matrigel (Sigma; Matrigel: serum-free medium = 1:1), whereas the lower compartment was filled with FBS containing medium. The chamber was kept at 37 °C for 48 h following which cells on the upper surface of the membrane were removed and the invaded cells through the Matrigel into the lower surface were stained with crystal violet (CV) solution (0.1% CV, 0.1 m borate, and 2% ethanol). Images were taken using a bright-field microscope (Magnus) and six visual fields were randomly chosen from which the number of invaded cells were quantified. Next, to determine the role of AKT/NF-κB and miR221 in promoting MDAMB231 or TNBC patient-derived MV-mediated MCF7 or BT474 cell invasion, a similar experimental set up as mentioned under “Wound-healing assay” was performed.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described earlier (11). Briefly, cells were lysed with 2× Laemmli buffer followed by heating at 95 °C for 5 min. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat, dried milk in TBS and probed with primary antibody (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the membrane was washed with TBST (TBS + 0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with secondary antibody (1:10,000; horseradish peroxidase-tagged or alkaline phosphatase-tagged; Sigma) for 1 h. The membrane was developed using either the ECL method (Luminol, coumaric acid, and H2O2 in 1 m Tris-Cl, pH 8.8) or the ALP method (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate, nitro blue tetrazolium in ALP buffer, pH 9.5). Band intensity was measured by ImageJ and quantified using GraphPad Prism5. The following antibodies were used: Snail, Slug, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin, phospho-AKT1, AKT1, phospho-p65 Ser-536, p65, PTEN, and tubulin, from Cell Signaling Technology; tissue factor was from Abcam; histone H3 and GAPDH were purchased from Sigma.

Real-time PCR analysis

Following the required treatments, total RNA was extracted by conventional TRIzol (Invitrogen) method and cDNA was prepared using oligo(dT) primer (GCC Biotech). cDNA samples, in triplicate, were subjected to real-time PCR with EMT-related gene primers (Table S2) using SYBR Green as per the manufacturer's instructions and the ΔCT values were analyzed. Experiments were repeated at least three times and graphs were plotted accordingly.

Nucleus isolation

Following all treatments, cells were lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer and centrifuged at 8000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to pellet down nuclei. The supernatant was used as a cytosolic fraction. A nuclear fraction was incubated with nuclear extraction buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.9, 0.42 m KCl, 0.2 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 2 mm DTT, 0.1 mm PMSF, and protease inhibitor mixture) for 20 min at 4 °C and centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 15 min to precipitate nuclear debris. The lysates were processed for analysis of nuclear phospho-NF-κB/p65 and total p65 using histone H3 as nuclear control, whereas the supernatant was used to analyze p65 taking tubulin as the cytosolic control.

Animal study

Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS) Institutional Animal Ethics Committee approved all the mice-related studies. MDAMB231 cells were transfected with Scrambled or anti-miR221 followed by treatment with FVIIa. MV were isolated and incorporated into MCF7. Alternatively, MCF7 cells were pre-transfected with anti-miR221 followed by fusion of MDAMB231-MV. MV-fused MCF7 cells (1 × 106) were introduced into 6-week-old female BALB/c nude mice (NIN; Hyderabad, India) via tail vein injection (7 mice were taken in each group). The mice were implanted 24 h post-injection, with 17β-estradiol, 0.36 mg/pellet, for 60 days. Lungs were harvested after euthanizing the mice after 25 days of injection. Lung tissues were subjected to H&E staining or genomic DNA isolation and quantitative PCR analysis as mentioned earlier (54). Briefly, lungs were digested with proteinase K at 55 °C followed by extraction of genomic DNA with phenol-chloroform, precipitation with isopropyl alcohol, and washing with ethanol. A 200-ng aliquot of genomic DNA was subjected to quantitative PCR amplification with human-specific HK2 gene primers and 18S rRNA primers (Table S2). Metastatic burden was quantified accordingly. Similarly, MCF7 cells were transfected with Scrambled or anti-miR221 followed by fusion with blood-derived MV (normal or patient) and in vivo metastasis assays were performed.

In another approach, to determine the proliferative effect of MV, MDAMB231-MV–fused MCF7 cells (after various treatments as mentioned earlier) were administered to the mice via subcutaneous injection (7 mice were taken in each group). After 25 days, mice were euthanized, tumors excised, and tumor volume (after measuring primary tumor in three dimensions, a, b, and c and volume was calculated using the formula: abc × 0.52) and weight were measured. Similarly, the proliferative effect of blood-derived MV was also analyzed.

Isolation of miR

MicroRNAs were extracted from cells and MV as mentioned previously (55). Briefly, total RNA (including miRs) was extracted by TRIzol followed by enrichment of miRs using 10% polyethylene glycol (4000 and 6000). The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 12 min and the supernatant was collected in a fresh tube followed by the addition of equal volume of LiCl (2.5 m) and 2× volume of pre-cooled absolute ethanol and incubation for 2 h at −80 °C. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C to obtain the miRs.

Quantification of miR221 by real-time PCR

cDNA of miR221 and human U6 small nuclear RNA were prepared from the pool of total isolated miRs using specific stem-loop RT primers (Table S3). The PCR conditions were 16 °C for 30 min, 42 °C for 30 min, and 85 °C for 5 min. PCR amplification of the target miR221 and control U6 small nuclear RNA was performed on a real-time machine (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Green. MCF7 cells were also pre-treated with actinomycin D (5 mg/ml; Sigma) for 8 h followed by MV fusion. Relative miR221 expression was quantified from the ΔCT values following the 2−ΔΔCT method and graphs were prepared accordingly.

Colony-formation assay

MDAMB231-derived MV (following required treatments) were fused with MCF7 and the recipient MCF7 cells (∼500 cells/well) in a single-cell form were seeded in 6-well-plates. Cells were incubated for 14 days at 37 °C and a 5% CO2 level in a humid atmosphere. Medium was aspired off, plates were washed 1× PBS, and cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The colonies were stained with CV solution for 1 h and after washing, images were taken from which the number of colonies were counted using ImageJ.

BrdU incorporation assay

MDAMB231-derived MV were fused with both MCF7 or BT474 cells and the recipient cells were cultured in a medium containing 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; 10 μm) for 8 h. Cells were fixed, washed with 1× PBS, and after blocking with 5% BSA incubated with anti-BrdU antibody (CST; 1:1000) overnight (after permeabilization with 0.01% Triton X-100). After washing, the cells were probed with secondary antibody (HRP- or fluorescent-tagged) for 1 h. Cells were washed followed by the addition of tetramethylbenzidine substrate with H2O2 (for HRP-tagged secondary antibody). OD was measured at 450 nm to assess the degree of cell proliferation. Alternatively, cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (for fluorescent-tagged secondary antibody) followed by imaging with a fluorescence microscope. The number of BrdU-positive cells were quantified and graphical representation was made.

Caspase 7 activity assay

Caspase 7 activity was measured in MDAMB231-MV–fused MCF7 cells after challenging with cisplatin (100 μm) for 18 h in a fluorometric approach using caspase 7 assay kit (Abcam; ab39401). Briefly, 1–5 × 106 cells were suspended in 50 μl of chilled cell lysis buffer (Abcam) for 30 min and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was taken in a 96-well-plate and incubated with 50 μl of 2× reaction buffer (containing 10 mm DTT, Abcam). Ac-DEVD-p-nitroanilide substrate was added to the wells (200 μm; Abcam) and incubated at 37 °C for 90 min after which the OD was measured at 405 nm on a fluorescent microplate reader.

MTT cell viability assay

Both MCF7 and BT474 cells were fused with MV isolated from MDAMB231 cells. MV-fused MCF7 were exposed to cisplatin for 30 h. MTT (1 mg/ml; SRL) was added to the wells (96-well-plate) followed by an additional 3 h of incubation. Medium was replaced with DMSO followed by measurement of OD at 570 nm from which cell viability percentage was calculated.

FACS analysis

Cellular apoptosis was determined by a FACS analyzer. MCF7 cells were seeded onto 35-mm dishes at 80% confluence, cisplatin (100 μm) treatment was done for various time points (0–48 h). Cells were harvested with EDTA and fixed with 70% ethanol for 30 min at 4 °C followed by washing with 1× PBS containing 2% FBS. Cells were then treated with RNase A (100 μg/ml; HIMEDIA) for 40 min followed by propidium iodide (5 μg/ml; SRL) addition for 15 min and subjected to FACS analysis (BD FACSAria). Cell death percentage was quantified from the G0/G1 population and accordingly graphs were prepared.

Statistical analysis

Images of Western blots and other techniques are representative of at least three independent experiments. For single comparison, data presented here are mean ± S.E. Differences are considered to be statistically significant at p < 0.05 using Student's t test. For multiple comparisons between the control and other groups, one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's test was applied at p < 0.05. For multiple comparisons among all groups of data, one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey-Kramer test was performed at p < 0.05. ns indicates nonsignificant differences.

Author contributions

K. D. and P. S. conceptualization; K. D., S. P., A. S., A. G., A. R., and R. P. data curation; K. D. formal analysis; K. D. validation; K. D. and P. S. investigation; K. D. visualization; K. D., S. P., A. S., A. G., R. P., and A. M. methodology; K. D., S. A. A., and P. S. writing-review and editing; P. S. supervision; P. S. funding acquisition; P. S. writing-original draft; P. S. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We owe special thanks to Dr. Ashis Mukherjee and Dr. Jayasri Basak of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Cancer Research Institute, Kolkata, for providing blood samples of human TNBC patients and ethical clearance. We also acknowledge Tanojit Sur for assistance in flow cytometry.

This work was supported in part by Department of Science and Technology, Government of India DST SR/SO/BB-0125/2012 for project grants and a fellowship from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S14 and Tables S1–S3.

- BC

- breast cancer

- PAR2

- protease-activated receptor2

- TF

- tissue factor

- AP

- activation peptide

- MV

- microvesicles

- PTEN

- phosphatase and tensin homolog

- miR221

- microRNA 221

- Scr

- Scrambled

- EMT

- epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- TNBC

- triple negative breast cancer

- MMP-2

- matrix metalloprotease-2

- CV

- crystal violet

- BrdU

- 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- EV

- extracellular vesicle

- FVIIa

- factor VIIa

- TF

- transcription factor

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

References

- 1. DeSantis C. E., Fedewa S. A., Goding Sauer A., Kramer J. L., Smith R. A., and Jemal A. (2016) Breast cancer statistics, 2015: convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 31–42 10.3322/caac.21320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hyslop T., Michael Y., Avery T., and Rui H. (2013) Population and target considerations for triple-negative breast cancer clinical trials. Biomark. Med. 7, 11–21 10.2217/bmm.12.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahn S. G., Kim S. J., Kim C., and Jeong J. (2016) Molecular classification of triple-negative breast cancer. J. Breast Cancer 19, 223–230 10.4048/jbc.2016.19.3.223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soung Y. H., Nguyen T., Cao H., Lee J., and Chung J. (2016) Emerging roles of exosomes in cancer invasion and metastasis. BMB Rep. 49, 18–25 10.5483/BMBRep.2016.49.1.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cocucci E., Racchetti G., and Meldolesi J. (2009) Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 43–51 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simons M., and Raposo G. (2009) Exosomes: vesicular carriers for intercellular communication. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 575–581 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Muralidharan-Chari V., Clancy J., Plou C., Romao M., Chavrier P., Raposo G., and D'Souza-Schorey C. (2009) ARF6-regulated shedding of tumor cell-derived plasma membrane microvesicles. Curr. Biol. 19, 1875–1885 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salido-Guadarrama I., Romero-Cordoba S., Peralta-Zaragoza O., Hidalgo-Miranda A., and Rodríguez-Dorantes M. (2014) MicroRNAs transported by exosomes in body fluids as mediators of intercellular communication in cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 7, 1327–1338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yáñez-Mó M., Siljander P. R., Andreu Z., Zavec A. B., Borràs F. E., Buzas E. I., Buzas K., Casal E., Cappello F., Carvalho J., Colás E., Cordeiro-da S. A., Fais S., Falcon-Perez J. M., Ghobrial I. M., et al. (2015) Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4, 27066 10.3402/jev.v4.27066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Das K., Prasad R., Roy S., Mukherjee A., and Sen P. (2018) The protease activated receptor2 promotes Rab5a mediated generation of pro-metastatic microvesicles. Sci. Rep. 8, 7357 10.1038/s41598-018-25725-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Das K., Prasad R., Singh A., Bhattacharya A., Roy A., Mallik S., Mukherjee A., and Sen P. (2018) Protease-activated receptor2 promotes actomyosin dependent transforming microvesicles generation from human breast cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 57, 1707–1722 10.1002/mc.22891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nystedt S., Emilsson K., Larsson A. K., Strömbeck B., and Sundelin J. (1995) Molecular cloning and functional expression of the gene encoding the human proteinase-activated receptor 2. Eur. J. Biochem. 232, 84–89 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20784.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Camerer E., Huang W., and Coughlin S. R. (2000) Tissue factor- and factor X-dependent activation of protease-activated receptor 2 by factor VIIa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 5255–5260 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miike S., McWilliam A. S., and Kita H. (2001) Trypsin induces activation and inflammatory mediator release from human eosinophils through protease-activated receptor-2. J. Immunol. 167, 6615–6622 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Su S., Li Y., Luo Y., Sheng Y., Su Y., Padia R. N., Pan Z. K., Dong Z., and Huang S. (2009) Proteinase-activated receptor 2 expression in breast cancer and its role in breast cancer cell migration. Oncogene 28, 3047–3057 10.1038/onc.2009.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang X., Li Q., Zhao H., Ma L., Meng T., Qian J., Jin R., Shen J., and Yu K. (2017) Pathological expression of tissue factor confers promising antitumor response to a novel therapeutic antibody SC1 in triple negative breast cancer and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 8, 59086–59102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matej R., Mandáková P., Netíková I., Poucková P., and Olejár T. (2007) Proteinase-activated receptor-2 expression in breast cancer and the role of trypsin on growth and metabolism of breast cancer cell line MDA MB-231. Physiol. Res. 56, 475–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roy A., Ansari S. A., Das K., Prasad R., Bhattacharya A., Mallik S., Mukherjee A., and Sen P. (2017) Coagulation factor VIIa-mediated protease-activated receptor 2 activation leads to β-catenin accumulation via the AKT/GSK3β pathway and contributes to breast cancer progression. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 13688–13701 10.1074/jbc.M116.764670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Das K., Prasad R., Ansari S. A., Roy A., Mukherjee A., and Sen P. (2018) Matrix metalloproteinase-2: a key regulator in coagulation proteases mediated human breast cancer progression through autocrine signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 105, 395–406 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bartel D. P. (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deng L., Lei Q., Wang Y., Wang Z., Xie G., Zhong X., Wang Y., Chen N., Qiu Y., Pu T., Bu H., and Zheng H. (2017) Downregulation of miR-221–3p and upregulation of its target gene PARP1 are prognostic biomarkers for triple negative breast cancer patients and associated with poor prognosis. Oncotarget 8, 108712–108725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pan Y., Li J., Zhang Y., Wang N., Liang H., Liu Y., Zhang C. Y., Zen K., and Gu H. (2016) Slug-upregulated miR-221 promotes breast cancer progression through suppressing E-cadherin expression. Sci. Rep. 6, 25798 10.1038/srep25798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li B., Lu Y., Wang H., Han X., Mao J., Li J., Yu L., Wang B., Fan S., Yu X., and Song B. (2016) miR-221/222 enhance the tumorigenicity of human breast cancer stem cells via modulation of PTEN/Akt pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 79, 93–101 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.01.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ye Z., Hao R., Cai Y., Wang X., and Huang G. (2016) Knockdown of miR-221 promotes the cisplatin-inducing apoptosis by targeting the BIM-Bax/Bak axis in breast cancer. Tumor Biol. 37, 4509–4515 10.1007/s13277-015-4267-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu J., Cao J., and Zhao X. (2015) miR-221 facilitates the TGFbeta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human bladder cancer cells by targeting STMN1. BMC Urol. 15, 36 10.1186/s12894-015-0028-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li B., Lu Y., Yu L., Han X., Wang H., Mao J., Shen J., Wang B., Tang J., Li C., and Song B. (2017) miR-221/222 promote cancer stem-like cell properties and tumor growth of breast cancer via targeting PTEN and sustained Akt/NF-κB/COX-2 activation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 277, 33–42 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cole M., and Bromberg M. (2013) Tissue factor as a novel target for treatment of breast cancer. Oncologist 18, 14–18 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ge L., Shenoy S. K., Lefkowitz R. J., and DeFea K. (2004) Constitutive protease-activated receptor-2-mediated migration of MDA MB-231 breast cancer cells requires both β-arrestin-1 and -2. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55419–55424 10.1074/jbc.M410312200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kalluri R., and Weinberg R. A. (2009) The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1420–1428 10.1172/JCI39104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Son H., and Moon A. (2010) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cell invasion. Toxicol. Res. 26, 245–252 10.5487/TR.2010.26.4.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liao G., Wang M., Ou Y., and Zhao Y. (2014) IGF-1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in MCF-7 cells is mediated by MUC1. Cell Signal. 26, 2131–2137 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kong L., Guo S., Liu C., Zhao Y., Feng C., Liu Y., Wang T., and Li C. (2016) Overexpression of SDF-1 activates the NF-κB pathway to induce epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like phenotypes of breast cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 48, 1085–1094 10.3892/ijo.2016.3343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maguire O., O'Loughlin K., and Minderman H. (2015) Simultaneous assessment of NF-κB/p65 phosphorylation and nuclear localization using imaging flow cytometry. J. Immunol. Methods. 423, 3–11 10.1016/j.jim.2015.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chiang K. C., Hsu S. Y., Lin S. J., Yeh C. N., Pang J. H., Wang S. Y., Hsu J. T., Yeh T. S., Chen L. W., Kuo S. F., Cheng Y. C., and Juang H. H. (2016) PTEN insufficiency increases breast cancer cell metastasis in vitro and in vivo in a xenograft zebrafish model. Anticancer Res. 36, 3997–4005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borowiec A. S., Hague F., Harir N., Guénin S., Guerineau F., Gouilleux F., Roudbaraki M., Lassoued K., and Ouadid-Ahidouch H. (2007) IGF-1 activates hEAG K+ channels through an Akt-dependent signaling pathway in breast cancer cells: role in cell proliferation. J. Cell Physiol. 212, 690–701 10.1002/jcp.21065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krishnan R. K., Nolte H., Sun T., Kaur H., Sreenivasan K., Looso M., Offermanns S., Krüger M., and Swiercz J. M. (2015) Quantitative analysis of the TNF-α-induced phosphoproteome reveals AEG-1/MTDH/LYRIC as an IKKβ substrate. Nat. Commun. 6, 6658 10.1038/ncomms7658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rojas-Puentes L., Cardona A. F., Carranza H., Vargas C., Jaramillo L. F., Zea D., Cetina L., Wills B., Ruiz-Garcia E., and Arrieta O. (2016) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, proliferation, and angiogenesis in locally advanced cervical cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Med. 5, 1989–1999 10.1002/cam4.751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Singh A., and Settleman J. (2010) EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: an emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene 29, 4741–4751 10.1038/onc.2010.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sigurðsson H. H., Olesen C. W., Dybboe R., Lauritzen G., and Pedersen S. F. (2015) Constitutively active ErbB2 regulates cisplatin-induced cell death in breast cancer cells via pro- and antiapoptotic mechanisms. Mol. Cancer Res. 13, 63–77 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jänicke R. U. (2009) MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells do not express caspase-3. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 117, 219–221 10.1007/s10549-008-0217-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sharma S., Patnaik P. K., Aronov S., and Kulshreshtha R. (2016) ApoptomiRs of breast cancer: basics to clinics. Front. Genet. 7, 175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hanahan D., and Weinberg R. A. (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Falkenberg N., Anastasov N., Rappl K., Braselmann H., Auer G., Walch A., Huber M., Höfig I., Schmitt M., Höfler H., Atkinson M. J., and Aubele M. (2013) miR-221/-222 differentiate prognostic groups in advanced breast cancers and influence cell invasion. Br. J. Cancer. 109, 2714–2723 10.1038/bjc.2013.625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim J. E., Ahn H. J., Ahn J. H., Yoon D. H., Kim S. B., Jung K. H., Gong G. Y., Kim M. J., Son B. H., and Ahn S. H. (2012) Impact of triple-negative breast cancer phenotype on prognosis in patients with stage I breast cancer. J. Breast Cancer 15, 197–202 10.4048/jbc.2012.15.2.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schmadeka R., Harmon B. E., and Singh M. (2014) Triple-negative breast carcinoma: current and emerging concepts. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 141, 462–477 10.1309/AJCPQN8GZ8SILKGN [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Al-Mahmood S., Sapiezynski J., Garbruzenko O. B., and Minko T. (2018) Metastatic and triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and treatment options. Drug. Deliv. Transl. Res. 8, 1483–1507 10.1007/s13346-018-0551-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morris D. R., Ding Y., Ricks T. K., Gullapalli A., Wolfe B. L., and Trejo J. (2006) Protease-activated receptor-2 is essential for factor VIIa and Xa-induced signaling, migration, and invasion of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 66, 307–314 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carvalho É., Hugo de Almeida V., Rondon A. M. R., Possik P. A., Viola J. P. B., and Monteiro R. Q. (2018) Protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) upregulates granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) expression in breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 504, 270–276 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Iablokov V., Hirota C. L., Peplowski M. A., Ramachandran R., Mihara K., Hollenberg M. D., and MacNaughton W. K. (2014) Proteinase-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) decreases apoptosis in colonic epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 34366–34377 10.1074/jbc.M114.610485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sun L., Li P. B., Yao Y. F., Xiu A. Y., Peng Z., Bai Y. H., and Gao Y. J. (2018) Proteinase-activated receptor 2 promotes tumor cell proliferation and metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition and predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 24, 1120–1133 10.3748/wjg.v24.i10.1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Storci G., Sansone P., Mari S., D'Uva G., Tavolari S., Guarnieri T., Taffurelli M., Ceccarelli C., Santini D., Chieco P., Marcu K. B., and Bonafè M. (2010) TNFα up-regulates SLUG via the NF-κB/HIF1α axis, which imparts breast cancer cells with a stem cell-like phenotype. J. Cell Physiol. 225, 682–691 10.1002/jcp.22264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dong R., Wang Q., He X. L., Chu Y. K., Lu J. G., and Ma Q. J. (2007) Role of nuclear factor κB and reactive oxygen species in the tumor necrosis factor-α-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of MCF-7 cells. Br. J. Med. Biol. Res. 40, 1071–1078 10.1590/S0100-879X2007000800007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bai D., Ueno L., and Vogt P. K. (2009) Akt-mediated regulation of NFκB and the essentialness of NFκB for the oncogenicity of PI3K and Akt. Int. J. Cancer. 125, 2863–2870 10.1002/ijc.24748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang T., Gilkes D. M., Takano N., Xiang L., Luo W., Bishop C. J., Chaturvedi P., Green J. J., and Semenza G. L. (2014) Hypoxia-inducible factors and RAB22A mediate formation of microvesicles that stimulate breast cancer invasion and metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E3234–E3242 10.1073/pnas.1410041111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zununi Vahed S., Barzegari A., Rahbar Saadat Y., Mohammadi S., and Samadi N. (2016) A microRNA isolation method from clinical samples. BioImpacts 6, 25–31 10.15171/bi.2016.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.