Abstract

Aspergillus fumigatus is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that causes both chronic and acute invasive infections. Galactosaminogalactan (GAG) is an integral component of the A. fumigatus biofilm matrix and a key virulence factor. GAG is a heterogeneous linear α-1,4–linked exopolysaccharide of galactose and GalNAc that is partially deacetylated after secretion. A cluster of five co-expressed genes has been linked to GAG biosynthesis and modification. One gene in this cluster, ega3, is annotated as encoding a putative α-1,4-galactosaminidase belonging to glycoside hydrolase family 114 (GH114). Herein, we show that recombinant Ega3 is an active glycoside hydrolase that disrupts GAG-dependent A. fumigatus and Pel polysaccharide-dependent Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms at nanomolar concentrations. Using MS and functional assays, we demonstrate that Ega3 is an endo-acting α-1,4-galactosaminidase whose activity depends on the conserved acidic residues, Asp-189 and Glu-247. X-ray crystallographic structural analysis of the apo Ega3 and an Ega3-galactosamine complex, at 1.76 and 2.09 Å resolutions, revealed a modified (β/α)8-fold with a deep electronegative cleft, which upon ligand binding is capped to form a tunnel. Our structural analysis coupled with in silico docking studies also uncovered the molecular determinants for galactosamine specificity and substrate binding at the −2 to +1 binding subsites. The findings in this study increase the structural and mechanistic understanding of the GH114 family, which has >600 members encoded by plant and opportunistic human pathogens, as well as in industrially used bacteria and fungi.

Keywords: glycoside hydrolase, biofilm, protein structure, enzyme mechanism, Aspergillus, carbohydrate processing, carbohydrate biosynthesis, exopolysaccharide matrix, galactosaminogalactan (GAG), glycoside hydrolase 114 (GH114), virulence factor

Introduction

Aspergillus fumigatus is a ubiquitous, filamentous fungus that causes invasive infections in immunocompromised patients (1). A. fumigatus can also cause chronic infections in patients with pre-existing lung conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cystic fibrosis (2–4). Even with currently available antifungal agents, the mortality of invasive aspergillosis remains over 50%, highlighting the need for new therapies that target A. fumigatus (2). During infection, A. fumigatus adopts a biofilm mode of growth, encapsulating itself in a self-produced matrix. The exopolysaccharide galactosaminogalactan (GAG)7 is an integral component of the A. fumigatus matrix and a key virulence factor (5–9). GAG mediates fungal adhesion to host cells and inhibits the host immune response by masking fungal β-glucan from dectin-1 recognition and inducing neutrophil apoptosis and secretion of the immunosuppressive cytokine interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (5, 7, 10).

GAG is a linear heteropolymer of α-1,4–linked galactose (Gal) and partially deacetylated N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) (11). Analysis of A. fumigatus GAG found random distribution of the monosaccharide constituents with the percentage of galactose within each chain ranging between 15 and 60% (11). The ratio of GalNAc/Gal varies among Aspergillus species and is higher in A. fumigatus than in less-virulent Aspergillus spp. (8). Increasing the GalNAc content of GAG in the relatively nonpathogenic Aspergillus nidulans increased the virulence of this species in an immunosuppressed mouse model, highlighting the importance of GalNAc content in GAG function (8). The location and percentage of deacetylation have not been determined to date, but this modification is required for biofilm formation and GAG adherence (8). Production of exopolysaccharides containing α-1,4–linked GalNAc and galactosamine (GalN) have also been confirmed in non-Aspergillus spp., including Neurospora crassa, Penicillium frequentans, Paecilomyces sp., and Trichosporon asahii (6, 12–15). These GAG-like polymers were found to be involved in adherence to surfaces or flocculation depending on the species, suggesting that GAG-like galactosamine-containing polymers are utilized by a variety of fungi and may be of importance in agriculture and food industries, as well as human health (12, 14, 15).

A comparative transcriptomic analysis of A. fumigatus regulatory mutants deficient in GAG production identified a cluster of genes on chromosome 3 linked to biofilm formation and GAG synthesis (6). This cluster encoded five putative carbohydrate-active enzymes. A model of the GAG biosynthetic system mediated by the products of these genes has been proposed (6), and to date, three of the genes, uge3, agd3, and sph3, have been experimentally linked to GAG production and virulence (6, 16, 17). Uge3 is a bifunctional cytoplasmic uridine diphosphatase (UDP)–glucose-4-epimerase that mediates the production of UDP-GalNAc and UDP-Gal (7, 17), Agd3 is a secreted protein required for the partial deacetylation of newly synthesized GAG polymer (6), and Sph3 is a GH135 member, with endo-α-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminidase activity, and is required for the production of GAG (16, 18). The other two genes in the cluster, gtb3 and ega3, are predicted to encode an integral membrane glycosyltransferase and a second glycoside hydrolase (GH), respectively (6, 16). Up-regulation of ega3 expression has been reported during biofilm formation (19), suggesting that Ega3 may play a role in both GAG biosynthesis and biofilm formation.

Bioinformatics analysis predicts Ega3 has an N-terminal transmembrane domain followed by an extracellular GH domain belonging to GH family 114. GH families are created based on sequence identity (20). Substrate specificity can vary within a family, but the identity of the catalytic residues and the mechanism are generally shared among family members (20–22). There are presently 616 members of the GH114, most of which are of bacterial origin (http://www.cazy.org, June 11, 2019)8 (92). A single GH114 protein from Pseudomonas sp. 881 (GH114Ps, GenBankTM accession no. D14846.1) is the only member of this family that has been functionally characterized to date (23–25). GH114Ps is specific for poly-α-1,4-GalN with no activity on poly-GalNAc substrates (24). The enzyme exhibits endo-galactosaminidase activity, releasing galactosamine disaccharides and trisaccharides from the nonreducing end of galactosamine polysaccharides (25). Low levels of transglycosylation were found suggesting that this GH114 uses a retaining mechanism (25). An endo-α-1,4-galactosaminidase has also been purified from Streptomyces griseus, but its amino acid sequence was not determined, and thus it cannot be assigned to a specific GH family (26). To date, endo-α-1,4-galactosaminidase activity has not been found in any other GH family. No structures of a GH114 family member are currently available, and the identity of the catalytic residues within these enzymes remains unknown.

Herein, the extracellular region of Ega3 was recombinantly expressed in the yeast host Pichia pastoris and purified to homogeneity. The Ega3 crystal structure revealed a modified (β/α)8-barrel that lacked β-strand 5 (β5), and α-helices 1 (α1) and 8 (α8). A structural insertion after β3 helps to create a deep cleft. Soaking Ega3 crystals in galactosamine allowed structural determination of an Ega3–GalN complex. Binding of galactosamine in the conserved cleft results in a conformational change and the formation of a tunnel, a structural feature that correlates with processive glycoside hydrolase activity (27). We show that Ega3 disrupts GAG-dependent biofilms at nanomolar concentrations, and using pure oligosaccharides demonstrates that the enzyme is an endo-α-1,4-galactosaminidase specific for GalN–GalN linkages. Our identification of the acidic catalytic residues at the ends of β4 and β6 supports a retaining mechanism for this GH family.

Results

Ega3 is predicted to have an extracellular GH114 domain

To gain insight into the structure and function of Ega3, we first examined its amino acid sequence to determine its domain structure and identify boundaries that could be used for construct design. The primary amino acid sequence of Ega3 from the UniProt database (gene AFUA_3G07890) was submitted to a number of bioinformatics servers. The TMHMM server (28) predicted that the N-terminal region of the protein contains a putative transmembrane helix between residues 22 and 45, with the N terminus residing in the cytosol (Fig. 1A). The extracellular region was predicted by BlastP and the dbCAN2 annotation server to include a GH114 domain between residues 83 and 314 (29, 30). The first 22 residues of the linker between the transmembrane helix and the GH114 domain, residues 46–68, have high glycine content and are predicted to be disordered according to Phyre2 (31).

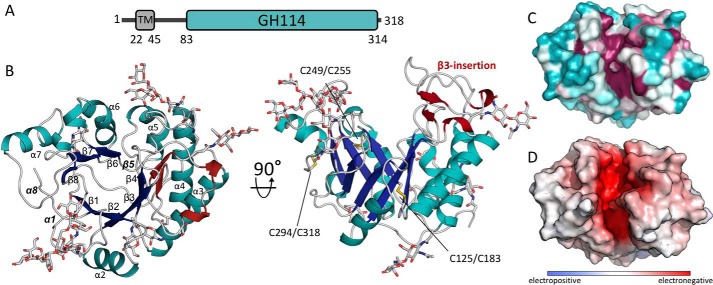

Figure 1.

Structure of Ega3 reveals a modified (β/α)8-barrel fold with a deep highly-conserved cleft. A, predicted domain arrangement of Ega3. B, crystal structure of (β/α)8-barrel fold of Ega3 shown in cartoon representation. The (β/α)-barrel is colored in blue (β-strands) and teal (α-helices) with the five N-glycans that could be built into the electron density displayed as gray sticks. The secondary structure elements of the β3-insertion are shown in dark red, and the three disulfide bonds are shown in yellow. The missing elements typically found in a (β/α)8-barrel, β5, α1, and α8, are labeled in bold and italic. C, surface representation colored from variable in teal to conserved in fuchsia, as calculated by Consurf (91). D, electrostatic surface, calculated using APBS in PyMOL, shows a highly negatively charged cleft (+10 kT to −10 kT) (60).

Ega3 adopts a (β/α)-barrel fold with a deep, highly-conserved groove

Based on these bioinformatics analyses, the predicted extracellular region of Ega3 (Ega346–318, referred to as Ega3 herein) was recombinantly produced in P. pastoris for in vitro structure–function studies. Attempts to produce soluble protein in Escherichia coli were unsuccessful. Ega3 was purified to homogeneity and used in crystallization trials both with and without its hexahistidine purification tag. Both tagged and untagged constructs crystallized in multiple conditions. Preliminary hits appeared as irregular square plates and long rods. A crystal produced using untagged Ega3 grown in 0.2 m lithium acetate and 20% (v/v) PEG 3350 yielded the highest-resolution data set, diffracting to 1.76 Å (Table 1). Conventional molecular replacement using the structure of highest-sequence identity, the hypothetical protein TM1410 from Thermatoga maritima (18% sequence identity, PDB 2AAM), was unsuccessful. Instead, phases were determined using ARCIMBOLDO_SHREDDER based on fragments of this distant homologue. After model building and refinement, the resulting structure encompassed residues 68–318 and had an Rwork and Rfree of 16.4 and 19.6%, respectively. No interpretable density was found for residues 46–67 suggesting the N-terminal region that links the GH114 domain to the transmembrane helix is largely disordered or prone to proteolytic cleavage.

Table 1.

Summary of data collection and refinement statistics for Ega3

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell.

| Ega3 | Ega3-GalN | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Beamline | CLS 08BM-1 | NSLS II 17ID-1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9792 | 0.9996 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å,°) | a = 44.6, b = 47.3, c = 152.5; α = β = γ = 90.0 | a = 44.8, b = 48.1, c = 163.4; α = β = γ = 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 42.8–1.76 (1.82–1.76) | 30.00–2.09 (2.17–2.09) |

| Total no. of reflections | 457,277 | 156,678 |

| No. of unique reflections | 32,553 | 21,680 |

| Redundancy | 14.0 (11.4) | 7.2 (7.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (88.7) | 99.7 (98.6) |

| Average I/σ(I) | 28.1 (4.27) | 11.25 (2.24) |

| Rmerge (%)a | 6.3 (59.4) | 12.4 (81.2) |

| CC½ (%)b | 100 (91.7) | 99.9 (95.6) |

| Refinement | ||

| Rworkc/Rfreed | 16.4/19.4 | 16.7/21.0 |

| CCwork/CCfree | 96.6/96.0 | 96.7/94.6 |

| No. of atoms | ||

| Protein | 1956 | 1958 |

| Glycan | 208 | 245 |

| GalN | 12 | |

| Water | 241 | 185 |

| Average B-factors (Å2)e | 31.3 | 36.2 |

| Protein | 27.4 | 32.3 |

| Glycan | 59.6 | 63.2 |

| GalN | 30.7 | |

| Water | 38.3 | 42.2 |

| RMSD | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.032 | 1.038 |

| Ramachandran plote | ||

| Total favored (%) | 99 | 99 |

| Total allowed (%) | 100 | 100 |

| Coordinate error (Å)f | 0.13 | 0.11 |

| PDB code | 6OJ1 | 6OJB |

aRmerge = ∑hkl∑j|Ihkl(j) − 〈Ihkl〉|/∑hkl∑j Ihkl(j), where Ihkl(j) and 〈Ihkl〉 represent the diffraction intensity values of the individual measurements, and the corresponding mean values, for each unique reflection. The summation is over all unique measurements.

b CC½ is the ratio of Pearson correlation coefficients (CC = ∑(x − 〈x〉) (ml − 〈ml〉)/(∑(x − 〈x〉)2∑(ml − 〈ml〉)2)1/2) between random half-sets of data.

c Rwork = ∑‖Fobs| − k|Fcalc‖/|Fobs|,where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

d Rfree is the sum extended over a subset of reflections (4.89% apo and 9.27% GalN-bound) excluded from all stages of the refinement.

e Data are as calculated using MolProbity (89).

f Maximum-likelihood-based coordinate error, as determined by PHENIX (81).

The structure of Ega3 consists of a central β-barrel of seven strands surrounded by six α-helices (Fig. 1B). β5, α1, and α8 of a canonical (β/α)8-barrel are replaced by regions with no regular secondary structure. The six cysteine residues present form three disulfide bonds, including the C-terminal amino acid Cys-318 that cross-links to Cys-294 on α7 (Fig. 1B). Density for five N-glycans was found linked to Asn-69, Asn-92, Asn-161, Asn-222, and Asn-253. Three sites, Asn-69, Asn-92, and Asn-161, were predicted to be glycosylated by the NetNGlyc 1.0 server (32). Asn-222 was given a low score by the server, and Asn-253 was not predicted as the sequon was Asn-Xaa-Cys instead of Asn-Xaa-(Ser/Thr) (32). Whether any of these sites are glycosylated in the native protein has yet to be determined, but it is interesting to note that only the sequons at Asn-92 and Asn-222 are conserved within Ega3 orthologues. The longest ordered N-glycan, linked to Asn-92, contained eight sugar moieties (Manα6[Manα3]Manα6[Manα2Manα3]Manβ4 GlcNAcβ4GlcNAc). Both the Asn-92- and Asn-69–linked glycans are highly ordered due to their participation in crystal contacts.

On the C-terminal end of the β-strands of the barrel there is a deep cleft. One side of the cleft is created by the loops after β3 and β4. There is a 29-amino acid insertion between β3 and α3 (β3-insertion) that contains a two-strand anti-parallel sheet with two small 310-helices (Fig. 1B). The other side of the cleft is formed by the loops following strands β1, β7, and β8. Mapping of the conserved, surface-exposed, amino acids shows highest conservation in the central cleft, which correlates with an electronegative surface potential (Fig. 1, C and D). The glycans do not obstruct the cleft and are located away from the conserved zone.

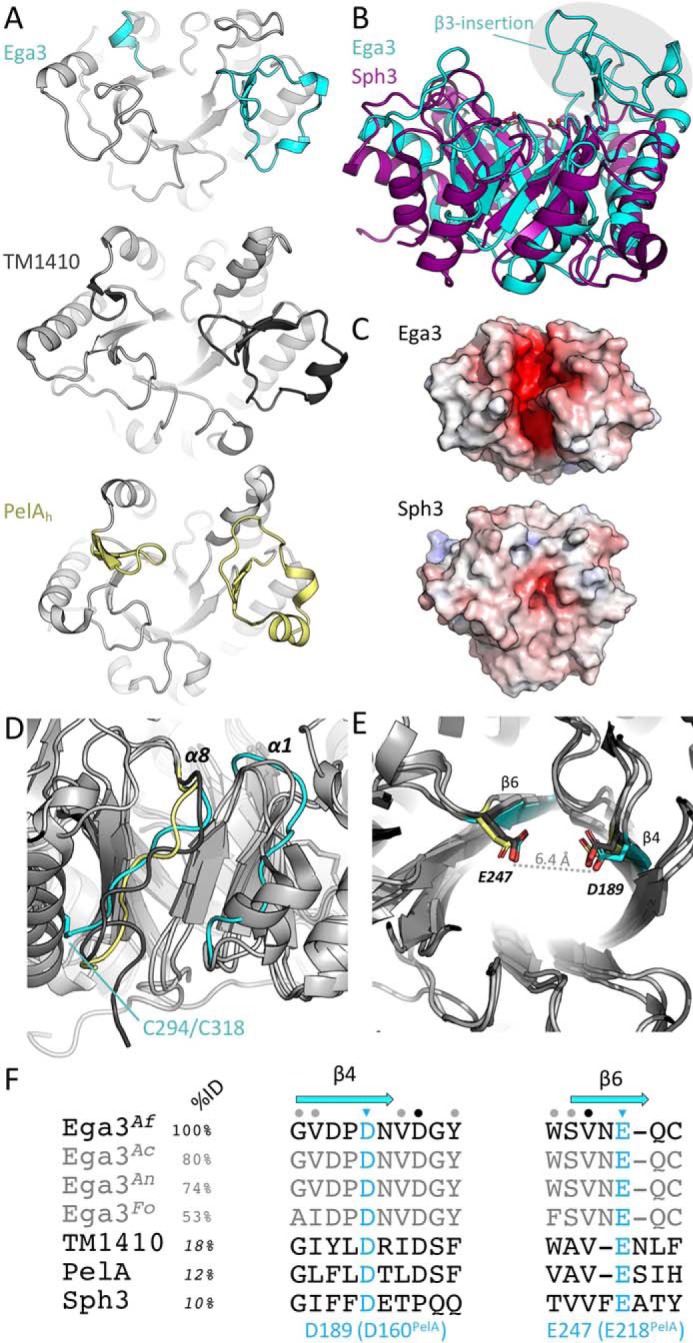

Ega3 shares structural similarity to PelAh and TM1410

As Ega3 is the first member of GH114 to be structurally characterized, we next sought to determine Ega3's nearest structural neighbors to gain insight into its potential function. In addition to T. maritima TM1410, which was used for phase determination, the structural similarity server, DALI (33), also found that Ega3 is similar to the hydrolase domain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PelA (PelAh, PDB 5TCB). Secondary structure alignment yielded a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 1.76 Å over 187 α-carbons for TM1410 and 3.25 Å over 189 α-carbons for PelAh. Ega3 and PelAh share 14.4% sequence identity as determined by ClustalOmega but only 12% according to structural alignment. The structure of TM1410 was determined as part of a structural genomics effort and has not been functionally characterized. PelAh has recently been shown to be an endo-α-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminidase belonging to family GH166 (18, 34, 35). PelA is involved in the biosynthesis of the Pel polysaccharide, which is similar to the GAG polysaccharide in that it contains 1,4-linked GalNAc, and is partially deacetylated (36). The overall structures of Ega3, TM1410, and PelAh align with high similarity in the central barrel motif (Fig. 2A). All three structures have a structural insertion after β3, although the number of strands and helices in this insert differ (Fig. 2A). In both PelAh and Ega3, this insert contains a two-strand sheet, whereas TM1410 is five residues longer and has a three-strand sheet.

Figure 2.

Ega3 is structurally similar to PelAh and TM1410. A, tertiary structure alignment of Ega3 (cyan), PelAh (yellow, PDB 5TCB (18)), and the hypothetical protein TM1410 from T. maritima (gray, PDB 2AAM). β3-insertion and structural elements following β6 are found in each structure and are colored. B, tertiary structure alignment of Ega3 (teal) with Sph3 (purple, PDB 5C5G (16)). The β3-insertion is circled and is not present in Sph3. C, comparison of surface electrostatics between Ega3 and Sph3 as done in Fig. 1. D, aligned structure from A emphasizing the lack of helical structure after β8 of the barrel. E, highly-conserved aspartic and glutamic acid residues occur at the end of β4 and β6, respectively, and are 6.4 Å apart in Ega3. F, sequence alignment of A. fumigatus Ega3 (Ega3Af) and its orthologues from Aspergillus clavatus (Ega3Ac), Aspergillus niger (Ega3An), and Fusarium oxysporum (Ega3Fo) with TM1410, PelAh, and Sph3 showing the degree of amino acid conservation surrounding the putative catalytic residues (blue). Secondary structure is represented in blue for Ega3 above the corresponding residues. Sequence identity to Ega3 is listed for the entire sequence with sequence conservation represented by colored dots; Ega3 orthologues were calculated by ClustalOmega; and TM1410, PelAh, and Sph3 sequence identities were determined through the secondary structure alignments in Coot.

Previously, we showed that Sph3, like PelAh, is an endo-α-1,4-N-acetyl-galactosaminidase that adopts a (β/α)-barrel fold (16, 18). Both Sph3 and Ega3 are encoded within the GAG cluster. Sph3 was ranked 109th in structural similarity to Ega3 by DALI out of a nonredundant subset of the PDB. Sph3 lacks the β3-insertion found in Ega3, PelA, and TM1410 (Fig. 2B). Alignment of Ega3 and Sph3 found only 10% sequence identity and RMSD of 2.99 Å over 170 of Ega3's 251 α-carbons. Ega3 has an deep electronegative cleft, and Sph3 has a shallower more neutral binding groove suggesting differences in substrate specificity (Fig. 2C).

Further similarity was found between PelAh, TM1410, and Ega3 structures that lack the eighth helix of the canonical (β/α)8-barrel and instead have an extended coil that packs against the barrel (Fig. 2D). In Ega3, this extended coil region represents the C terminus of the protein and is anchored to α7 by a disulfide bond (Fig. 2D). Ega3 is unique in that it also lacks α1. Both PelAh and TM1410 contain a β-hairpin after β6, whereas Ega3 has a single turn 310-helix (Fig. 2B).

The active-site residues of (β/α)-barrel glycoside hydrolases are usually found at the C termini of the β-strands of the barrel. The activity of PelAh depends on a highly-conserved glutamic acid (Glu-218) at the C terminus of β4 and Asp-160 at the C terminus of β6 (18, 37). Structural alignment to PelAh shows conservation of these acidic residues in both TM1410 and Ega3 (Fig. 2D). Higher sequence conservation between these proteins was found in the region of Asp-189Ega3 (Asp-160PelA) as compared with the region around Glu-247Ega3 (Glu-218PelA) (Fig. 2E). Asp-189 and Glu-247 were previously identified as putative active-site residues in a bioinformatic analysis of the GH114 family (38). The distance between these residues is congruent with a retaining mechanism that was previously proposed for GH114Ps.

Ega3 disrupts both Pel- and GAG-dependent biofilms

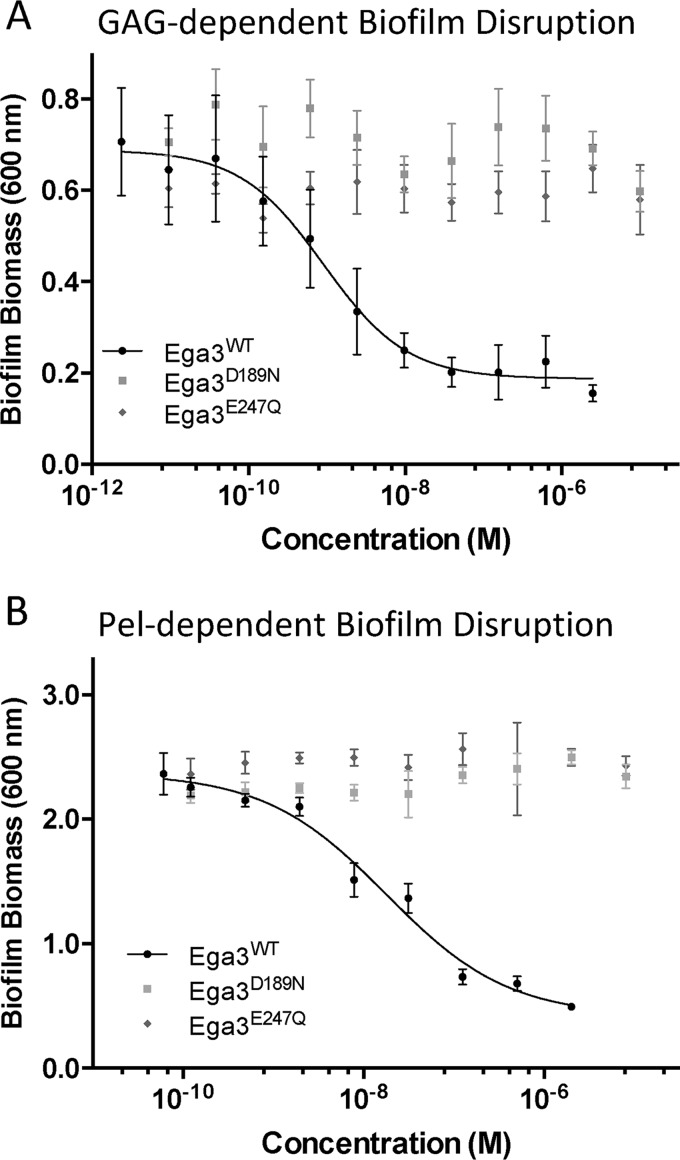

The α-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminidase PelAh disrupts both P. aeruginosa Pel-dependent and A. fumigatus GAG-dependent biofilms (35, 37). Given the structural similarities between Ega3 and PelAh, we next investigated whether Ega3, like PelAh, was an active glycoside hydrolase with cross-kingdom anti-biofilm activity. Biofilm disruption assays performed using A. fumigatus Af293 biofilms revealed that Ega3 disrupted Af293 biofilms with half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of 0.85 nm (logEC50 −9.07 SE 0.21, Fig. 3A). Ega3 was also able to disrupt P. aeruginosa PA14 Pel-dependent biofilms within 1 h with an EC50 of 96 nm (logEC50 −7.01 SE 0.11, Fig. 3B). Site-directed mutants of the putative active-site residues, Ega3D189N and Ega3E247Q, abrogated GAG and Pel biofilm disruption activity. Collectively, these findings suggest that Ega3 is an active glycoside hydrolase that requires Asp-189 and Glu-247 for its cross-kingdom activity.

Figure 3.

Ega3 treatment disrupts A. fumigatus and P. aeruginosa biofilm. Effects of the treatment with the indicated hydrolases on Af293 biofilms (A) and.Pel-dependent P. aeruginosa PA14 biofilms (B). Residual biofilm biomass was quantified by crystal violet staining.

Ega3 is specific for galactosamine regions of GAG

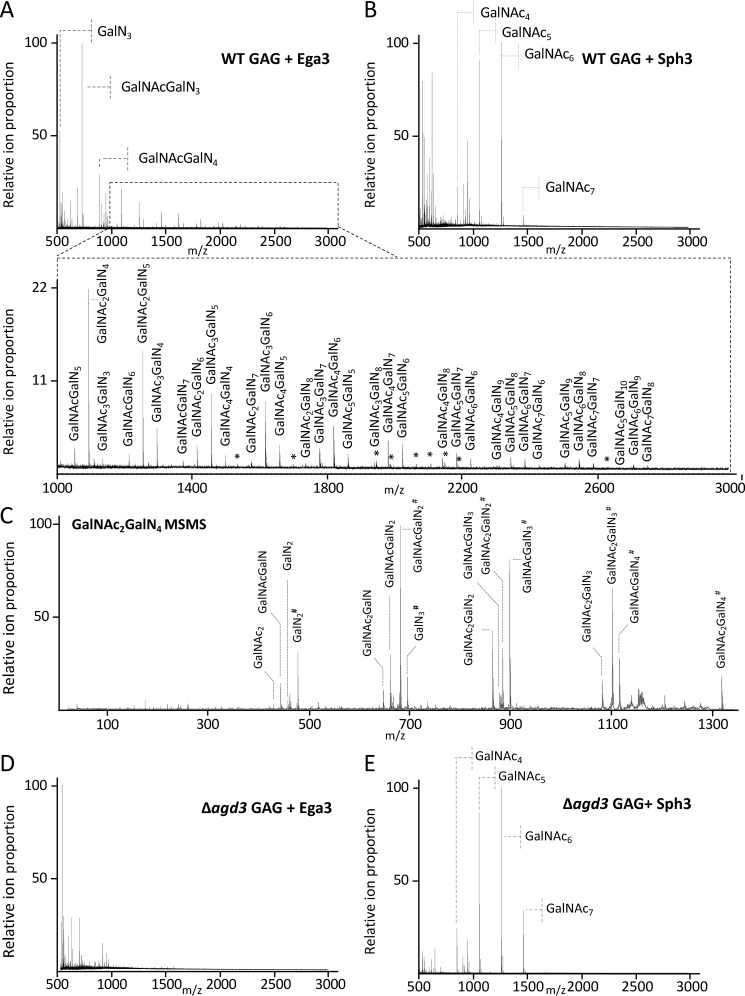

To probe the substrate specificity of Ega3, a mass spectrometry (MS) approach was used. Secreted GAG present in the supernatant of A. fumigatus cultures contains a mixture of GalNAc and GalN with relatively low Gal content (18). Treatment of secreted GAG with Ega3 resulted in the release of products with ions corresponding to mass to charge (m/z) ratios consistent with tri- to pentadecasaccharides (15-mers) containing a mixture of hexosamine (HexN) and N-acetylhexosamine (HexNAc) moieties (Fig. 4A). There was evidence of disaccharide products; however, due to experimental limitations these ions were poorly resolved and not quantifiable. The released oligosaccharides also suggest that there are regions of GAG that are highly deacetylated, ranging from 50 to 100% deacetylated moieties.

Figure 4.

Ega3 is specific for GalN-containing regions of GAG. MALDI-TOF MS spectra of oligosaccharide products released by treatment of secreted GAG from WT A. fumigatus after treatment with 1 μm Sph3 (A) or 1 μm Ega3 (B) are shown. C, MS-MS spectra of the reduced and propionylated tetra-deacetylated galactosamine hexasaccharide species produced from Ega3 treatment. Ions are labeled with their monosaccharide composition, with the numerical subscript indicating the number of sugar units present, and # indicates the reducing end of the oligosaccharide., MALDI-TOF MS spectra of secreted GAG purified from the A. fumigatus Δagd3 mutant after treatment with 1 μm Ega3 (D) or Sph3 (E). All ions corresponding to oligosaccharides are labeled with monosaccharide composition or with an asterisk for the low intensity ions.

In contrast to Ega3, treatment of secreted GAG with Sph3, which we have previously shown is an endo-α-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminidase, resulted in the release of acetylated oligosaccharides only (Fig. 4B) (18). Fragmentation analysis of the reduced and propionylated tetra-deacetylated hexasaccharide products of Ega3 digestion revealed the presence of a HexN moiety at the reducing end of the oligosaccharide (Fig. 4C). These results support the specificity of Ega3 for galactosamine at the site of cleavage. To determine whether deacetylation of GalNAc was required for Ega3 activity, fully acetylated GAG isolated from the Δagd3 strain was used as the substrate for Ega3 and Sph3 treatment. Exposure of fully acetylated GAG to Ega3 did not result in the release of any detectable oligosaccharide products further supporting Ega3 specificity for deacetylated GAG (Fig. 4C). In contrast, Sph3 resulted in a similar product profile as observed with partially deacetylated GAG from WT A. fumigatus (Fig. 4D). We previously determined that sph3 was required for GAG production and biofilm formation in a strain that exhibited WT levels of ega3 expression (16). The difference in specificity between Sph3 and Ega3 is congruent with the lack of functional redundancy found in these in vivo experiments and suggests that these hydrolases play different roles in A. fumigatus GAG synthesis.

Ega3 is an endo-α-1,4-galactosaminidase

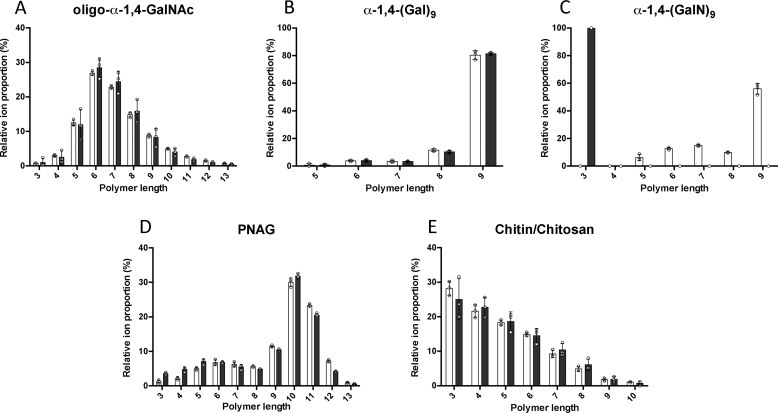

To confirm the specificity of Ega3 for α-1,4-(GalN)n, the ability of Ega3 to cleave oligosaccharides with different linkage and monosaccharide composition was tested. Substrates used included α-1,4-GalNAc oligosaccharides purified from native GAG as well as synthesized α-1,4-(Gal)9 and α-1,4-(GalN)9 (Fig. 5). No measurable hydrolysis of synthesized α-1,4-(Gal)9 or purified oligo-α-1,4-GalNAc was observed by MS analysis (Fig. 5, A and B). However, a 24-h treatment of synthesized α-1,4-(GalN)9 with Ega3 resulted in the disappearance of α-1,4-(GalN)9 ions, as well as the trace amounts of α-1,4-(GalN)5–8, and emergence of trisaccharide products suggesting that Ega3 acts as an endoglycosidase (Fig. 5C). Disaccharides were not measured with this method due to interference of the signal by the MS matrix, but are possible products of these reactions. Ega3 exhibited no activity on polymers of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc). Ega3 did not hydrolyze either the synthesized exopolysaccharide poly-β-1,6-GlcNAc (oligo-β-1,6-GlcNAc, PNAG), which is a component of many bacterial biofilms (Fig. 5D) (39), or chitin or its derivative chitosan (fully acetylated and partially de-N-acetylated poly-β-1,4-N-GlcNAc, respectively, Fig. 5E) which are a major component of the fungal cell wall (40). Ega3's production of trisaccharides from α-1,4-(GalN)9 further supports its endo-activity and specificity for α-1,4-GalN linkages (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Ega3 is an endo-α-1,4-galactosaminidase. MS analyses of oligosaccharide substrates before (white bars) and after treatment with 10 μm Ega3 for 24 h (black bars) are shown. Substrates include the following: A, purified oligo-α-1,4-GalNAc isolated from GAG biofilms; B, synthesized α-1,4-(Gal)9; C, synthesized α-1,4-(GalN)9; D, synthesized oligo-β-1,6-GlcNAc (PNAG); and E, chitin/chitosan. Statistically significant differences between pre- and post-treatment oligosaccharide profiles were observed only for α-1,4-(GalN)9 in C.

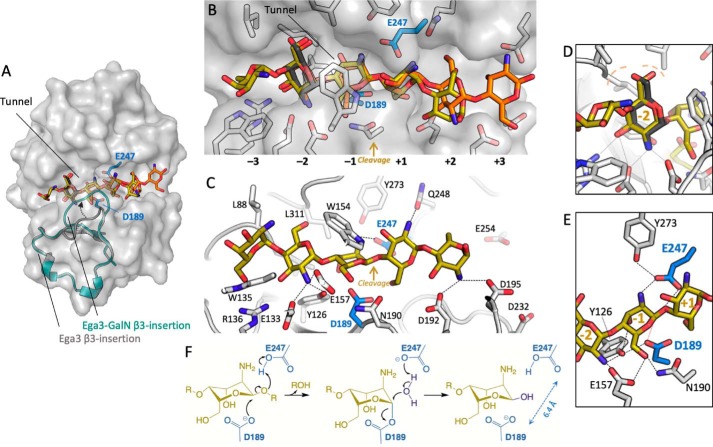

Ega3 binds galactosamine creating a substrate tunnel

To probe the specificity of Ega3 at the molecular level, co-crystallization and crystal soaking trials were performed using either galactosamine or GalNAc. Although crystals formed in the presence of both monosaccharides, interpretable density for a monosaccharide was only found for galactosamine. A single galactosamine monomer was found bound in the active-site cleft (Fig. 6A). The galactosamine occupies substrate subsite −2, based on the orientation and distance from the site of cleavage (between −1/+1 sites). The overall structures of the galactosamine complex and apo-Ega3 are very similar with the exception of the β3-insertion, which moved up to ∼8 Å and folded over the galactosamine moiety creating a tunnel (Fig. 6B). The loop contains a highly-conserved tryptophan, Trp-154, which binds the galactosamine amino group through a π–cation interaction and moved 12.3 Å compared with the apo-structure (Fig. 6B). The side chain of Glu-157 also moved 1.6 Å compared with the unbound structure. Glu-133 and Glu-157 create an electronegative pocket that accommodates the amine of the galactosamine (Fig. 6C). Three leucines, Leu-87, -88, and -]311 form a hydrophobic pocket close to the C6 of the galactosamine (Fig. 6C). The hydroxyl oxygens of C6 and C3 are coordinated by the backbone carbonyls of Asn-310 and Arg-136, respectively.

Figure 6.

Ega3 binds galactosamine using a flexible loop to create a substrate-binding tunnel. A, cartoon representation of the Ega3–GalN complex with transparent surface representation. B, alignment of apo-Ega3 (cyan) and Ega3–GalN (dark teal) showing the movement of the β3-insertion containing Glu-133, Trp-154, and Glu-157. C, galactosamine-binding site with the |Fo − Fc| omit map contoured at 3.0 σ. Residues that interact with galactosamine are in orange, and the putative catalytic acidic residues are in teal. D, comparison of the flexible loop contained in the β3-insertion of Ega3 (teal), Ega3–GalN (dark teal), PelAh (yellow, PDB 5TCB), and TM1410 (gray, PDB 2AAM). The unknown ligand in TM1410 is in red. E, sequence alignment of the β3-insertion of Ega3 orthologues, and TM1410 and PelAh based on the structural alignment. Residues in β-strands are in blue, and helices (310 and α) in yellow are shown in cartoon representation of the Ega3 2° structure above. Residues that bind galactosamine are shown in red. Sequence identity was calculated by ClustalOmega for Ega3 proteins, whereas TM1410, PelAh, and Sph3 sequence identity was determined through the structural alignments in Coot.

Comparing the β3-insertion of Ega3 to that of PelAh and TM1410, Trp-154 was found to be conserved in all three proteins and throughout Ega3 orthologues (Fig. 6, D and E). PelAh has an “open” conformation similar to apo-Ega3 (Fig. 6D). TM1410 was crystallized with an unknown ligand that contains a ring reminiscent of a carbohydrate. The Trp-154 equivalent (Trp-121TM1410) folds over the ligand in a similar “capped” conformation as observed in the Ega3–GalN structure (Fig. 6D). Sequence alignment of the β3-insertions shows little conservation in sequence between Ega3 and TM1410, or PelAh, besides the tunnel-forming tryptophan (Fig. 6E). TM1410 and Ega3 share slightly higher identity within the insertion, with conservation at the Glu-133, and an asparagine replacing Glu-157. In the place of Trp-135 and Arg-136 in Ega3, TM1410 has a Tyr/Arg pair. These similarities suggest a comparable binding site for a hexosamine. PelAh does not have comparable residues with a serine aligning to Glu-157 and an aspartic acid replacing Glu-133 (Fig. 6, D and E). Thus, PelAh has a larger and less electronegative pocket than the one created by Glu-133 and Glu-157 in Ega3.

Docking of α-1,4-(GalN)5 on Ega3 reveals six substrate-binding subsites

Although the co-crystal structure of Ega3–GalN revealed a single sugar-binding site within the deep active-site cleft, the substrate for Ega3 is polymeric. The disappearance of (GalN)5 upon oligo-α-1,4-GalN cleavage suggests that a pentasaccharide is a productive substrate of Ega3 (Fig. 5C). To determine potential binding sites for an oligo-α-1,4-(GalN)5 substrate, docking studies were performed using Glide in the Schrodinger software suite (41–43). The docking of an α-1,4-GalN pentasaccharide in the Ega3–GalN structure, after removal of the monosaccharide found in this structure, yielded multiple conformations within the predicted binding cleft (Fig. 7A). The 10 highest-scoring conformations all predicted a galactosamine moiety binding at the −2 subsite oriented in the same manner as the galactosamine monomer found in the Ega3–GalN structure, supporting the validity of the docking studies (Fig. 7, B and D). There were two predominant groups of conformers, one group docked in the −3 to +2 subsites, and the second group docked in the 2 to +3 subsites (Fig. 7, B and C).

Figure 7.

In silico docking of α-1,4-(GalN)5 reveals six substrate-binding subsites. A, transparent surface representation of Ega3 structure with the galactosamine (dark gray) found in the crystal structure and the top two scoring conformations (no. 1 is yellow and no. 2 is orange). The β3-insertion is shown as a cartoon labeled with an arrowhead indicating the change between the apo structure (gray) and Ega3–GalN (teal). Putative catalytic residues are in blue. B, cartoon representation of the Ega3–GalN structure (white) and putative catalytic residues (blue). The galactosamine (dark gray) found in the crystal structure aligns with the top two scoring conformations (no. 1 is yellow and no. 2 is orange). The subsites are numbered with the putative site of cleavage between −1 and +1. C, side view of the lowest energy conformer (yellow) with residues that participate in binding the oligosaccharide labeled. Dashed lines indicate H-bonds and salt bridges to ligand amines. All interaction distances are less than 3.1 Å. D, saccharide in subsite −2 overlaps with the galactosamine (dark gray) in the Ega3–GalN structure and has an identical hydrogen bond network. The hydrophobic pocket created by Leu-88 and Leu-311 is indicated by the dashed light orange lines. E, Ega3 active site with the hydrogen bond network is indicated by the dashed black lines. The catalytic nucleophile, Asp-189, is aligned to attack the anomeric carbon (red dashed line). F, proposed mechanism of Ega3 with D189 acting as the catalytic nucleophile.

These docking studies shed light on the mechanism of Ega3, as the positioning of sugars in the +1 and −1 subsites would allow Asp-189 to attack the anomeric carbon and Glu-247 to protonate the oxygen of the glycosidic bond (Fig. 7E). Glu-247 is then well-positioned to activate a water molecule to attack the anomeric carbon of the glycosyl–enzyme intermediate (Fig. 7E). Thus, the docking supports the proposed retaining enzyme mechanism of GH114 family members and suggests roles for Asp-189 and Glu-247 as the nucleophile and catalytic acid/base, respectively (Fig. 7F). As noted above, single point mutants of D189N and E247Q were unable to disrupt either GAG or Pel-dependent biofilms (Fig. 3), supporting the role of Asp-189 and Glu-247 as the catalytic nucleophile and acid/base, respectively. The docking studies also provide a rationale for the specificity of Ega3 for galactosamine substrates over GalNAc as many hydrogen bonds are created between the polar and charged residues in the −2 to +3 sites and the α-1,4-(GalN)5 (Fig. 7C). Addition of an acetate group to the moiety in subsite −2 would lead to steric clashes, suggesting that this site serves as a filter for galactosamine substrates.

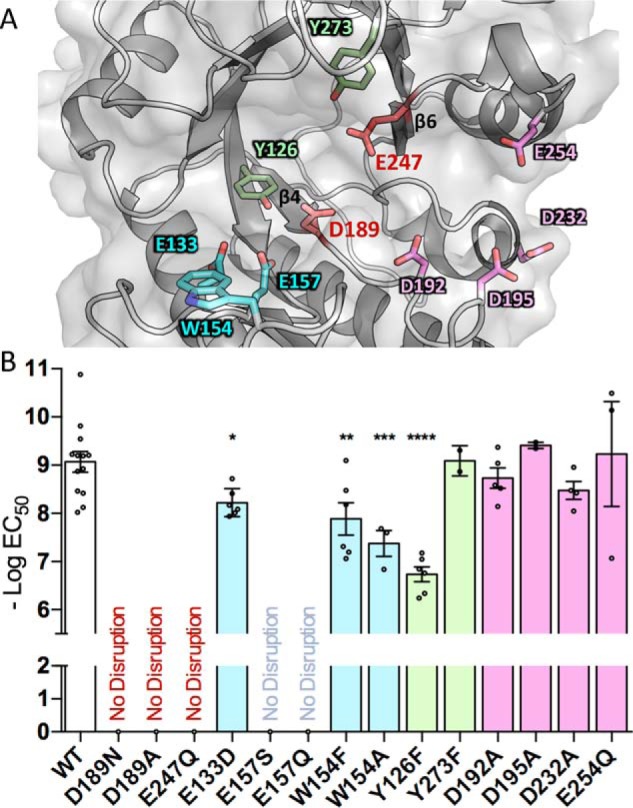

Conserved residues in the deep binding cleft are important for activity

The results of our docking studies suggest determinants of substrate binding and catalysis. To experimentally validate which residues are important for catalysis and substrate binding, alanine and conservative point mutants were made to the residues in the binding cleft and those identified in the Ega3–GalN structure and docking studies (Fig. 8A).

Figure 8.

Ega3 requires conserved acidic residues for GAG hydrolysis and anti-biofilm activity. A, cartoon representation of Ega3 showing the residues mutated in this study. B, point mutations of the conserved amino acids in the putative substrate-binding cleft were assayed for activity against A. fumigatus biofilms. No disruption indicates no activity against biofilms at the highest concentrations tested (100 μm). Text and bar colors correspond to the residue coloring as depicted in A. Bars indicate the mean of 2–8 assays performed in triplicate with the standard deviation of the logEC50. Statistical significance as compared with WT was determined using one-way analysis of variance with Dunn's multiple comparison. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, ****, p < 0.0001.

Examination of the Ega3 structures reveal that Tyr-126 creates a hydrogen bond network between Asp-189 and the galactosamine amino group in −2 subsite (Fig. 7D). Tyrosines neighboring catalytic residues have been found to increase catalytic activity by positioning the carboxyl group modulating pKa (44–47). Mutation of Tyr-126 to phenylalanine (Y126F) abolishes this network and reduces biofilm disruption activity 215-fold compared with WT Ega3 (Fig. 8B). This decrease in activity suggests that Tyr-126 may be involved in activating the catalytic nucleophile, Asp-189.

Tunnel formation has previously been correlated with processivity of glycoside hydrolases and a decrease in substrate off-rates (27, 48–51). Replacing the tunnel-forming tryptophan with phenylalanine (W154F) or alanine (W154A) decreased biofilm disruption activity compared with WT Ega3 (Fig. 8B). Mutation to alanine would prevent the π–cation interactions between the substrate and tryptophan, which could be important for tunnel formation. These results suggest that Trp-154 is important for substrate binding and that tunnel formation may increase Ega3 efficiency by increasing processivity.

Residues in the β3-insertion that coordinate the monosaccharide in the Ega3–GalN structure were also found to be important for activity. Glu-157 and Glu-133 hydrogen bond to the GalN amine at the −2 subsite in both Ega3–GalN structure and the docking studies. Replacement of Glu-157 with serine completely abolishes the ability of the mutant enzyme to disrupt the biofilm. The conservative mutation of Glu-157 to glutamine (E157Q) also had no measurable activity on GAG biofilms. These findings, along with the structure and docking studies, suggest that the negative charge is required at this position for galactosamine binding. Similar to the results for Glu-157, mutation of Glu-133 to aspartate, which conserves the charge, led to a significant decrease in the ability to disrupt GAG. These residues are conserved in Ega3 homologues, and the mutagenesis results support an important role in substrate affinity. PelAh has less bulky residues at the −2 subsite, with a serine and aspartate aligning to Glu-157 and Glu-133, respectively. Ega3 thus has a smaller more negatively charged binding pocket than PelAh, which may account for the differences in substrate specificity between these enzymes.

The results of the docking studies also suggest that the acidic residues that line subsites +2 and +3 may play a role in hydrogen bonding of the oligosaccharide substrate. Single mutation of any of these residues to alanine had no significant effect on Ega3 activity levels. The participation of multiple acidic residues in binding may provide some redundancy, thus leading to minimal effects on the activity when only one alanine is mutated. Taken as a whole, the mutagenesis data support that Asp-189 and Glu-247 at the termini of β4 and β6, respectively, are the catalytic residues. Furthermore, the residues at the −2 subsite were found to affect Ega3 activity, strengthening the results of the substrate docking and Ega3–GalN structure and suggesting that this site acts as a filter for galactosamine specificity and affinity.

Discussion

The location of ega3 within the GAG cluster and its up-regulation during biofilm formation suggest that the GH114 domain encoded by this gene likely plays a role in the GAG biosynthesis. The hydrolase domain of Ega3 is predicted to be extracellular and thus could interact with GAG during or after secretion. Herein, using structural and biochemical characterization, we show that Ega3 is an endo-α-1,4-galactosaminidase specific for galactosamine regions of the GAG heteropolymer. A flexible loop, which creates a tunnel upon substrate binding, and the orientation and distance between the key catalytic residues suggest that Ega3 has a processive, retaining enzyme mechanism (Fig. 7).

Previously, a GH114 from Pseudomonas sp. 881 was shown to be an endo-α-1,4-galactosaminidase, specific for α-1,4-GalN–GalN bonds using an α-1,4-GalNAc/GalN substrate isolated from Paecilomyces sp. (24, 26). The sequence identity between Ega3 and the GH domain of GH114Ps is 49%, with high identity around Asp-189 and Glu-247. This is much higher than the sequence identity between Ega3 and PelAh (14.4%, ClustalOmega). As substrate specificity is not always shared within a GH family and to determine whether Ega3's activity is more similar to PelAh or GH114Ps, defined length substrates that represent sections of the GAG polymer were synthesized and their hydrolysis products analyzed. Ega3 was found to have endo-α-1,4-galactosaminidase activity and unlike PelAh had no measurable activity on the fully-acetylated polymer (18).

The specificity of Ega3 for galactosamine is supported by the structure of the Ega3–GalN complex. The amino group of the galactosamine is coordinated by Glu-133, Glu-157, and Tyr-126. These residues are conserved in Ega3 orthologues as well as GH114Ps. Addition of an acetate group would create steric clashes suggesting that Ega3 could not accommodate GalNAc at this site (−2 subsite). PelAh has smaller residues in the structurally equivalent positions suggesting that PelAh could accommodate both acetylated and deacetylated oligosaccharides. Furthermore, mutation of Glu-157 to serine or glutamine greatly decreases Ega3's ability to hydrolyze GAG biofilms (Fig. 8). As only the −2 subsite was occupied in the galactosamine crystal structure, despite the high concentration of monosaccharide used, it suggests that this subsite has the highest affinity for the monosaccharide and may be important for the alignment and affinity of the polysaccharide substrate. This hypothesis is supported by the in silico docking of α-1,4-(GalN)5 into the “capped” Ega3 structure. The high-scoring ligand conformations all had a galactosamine moiety in subsite −2 that superimposes with the galactosamine found in the crystal structure (Fig. 7). Thus, Ega3 may require a galactosamine at the −2 subsite to orient the substrate prior to cleavage. Recently, a similar requirement for a deacetylated moiety to help orient the substrate was found for the endo-acting glycoside hydrolase PgaB, which hydrolyzes partially deacetylated PNAG polysaccharide. PgaB requires the sequence of GlcN–GlcNAc–GlcNAc in the −3 to −1 subsites for substrate binding and cleavage (52).

Galactosamine binding caused a large conformational change in the β3-insertion of Ega3 (Fig. 6). The monosaccharide participates in π–cation stacking with a highly-conserved tunnel-forming tryptophan. Tunnel formation has been strongly correlated with processive activity where once bound, and the polysaccharide substrate may be cleaved repetitively from one end (27, 49, 53, 54). Endo-acting processive enzymes have been found to produce predominantly short oligosaccharides, including di- to tetrasaccharides from polysaccharide substrates. Although the experimental approach precluded the clear quantification of disaccharides or detection of monosaccharide products, Ega3 treatment of secreted GAG produced significant levels of (GalN)3 (Fig. 4). Processivity could not be directly measured using the methods employed herein, but the accumulation of (GalN)3 and tunnel formation upon substrate binding are both suggestive of processivity, in which Ega3 would bind galactosamine regions of GAG and release (GalN)3 multiple times from one end before disassociation from the substrate. GH114Ps was also found to produce largely (GalN)3 and some (GalN)2 from polysaccharide substrates when incubated for extended periods (25). GalNAc may affect the degree of processivity but can be accommodated in some Ega3 subsites as shown by the products from soluble GAG after Ega3 treatment (Fig. 4A). Further experiments would be necessary to measure the degree of processivity exhibited by Ega3 in vitro. The insertion after β3 and the tryptophan are conserved in TM1410 and PelAh, and structures of these proteins represent the “capped” and “open” state of the binding cleft, respectively (Fig. 6D). The two structures of Ega3 presented herein strongly suggest that the flexibility of the β3-insertion plays a crucial role in substrate binding in all three enzymes and conservation of tunnel formation.

Ega3 was found to disrupt GAG- and Pel-dependent biofilms with nanomolar EC50 values comparable with the activity of PelAh. The EC50 values for PelAh are 2.8 and 35.7 nm on GAG and Pel biofilms, respectively (34, 35). We have recently shown that PelAh is an endo-α-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminidase with preference for partially deacetylated substrates. The Pel polysaccharide itself has been reported to be a partially deacetylated 1,4-linked polymer of GalNAc and GlcNAc at a 5:1 ratio (36). The percent deacetylation and which component is deacetylated, GalNAc or GlcNAc, or both, has not yet been determined. Herein, digestion of GAG by Ega3 supports high heterogeneity with blocks that are over 50% deacetylated and regions that are fully acetylated and susceptible to Sph3 digest. The cross-reactivity of Ega3 against Pel-dependent biofilms suggests the presence of α-1,4-(GalN)n within the Pel polysaccharide.

Glycoside hydrolases are important for optimal exopolysaccharide export and biofilm formation in multiple bacterial species (55–59). For example, the synthesis of carboxymethylcellulose by Acetobacter xylinus (57) and Gluconacetobacter xylinus (56) requires the GH8 enzyme CMCax for cellulose assembly. In the absence of CMCax the nascent cellulose creates highly-twisted conformations that have been suggested to stall cellulose production (56). A similar role has been proposed for Sph3 in GAG biosynthesis but has not been experimentally verified (16). The Candida endoglucanase Xog1 also plays a role in matrix β-1,3-glucan production but again its mechanism is not known (61, 62). The role of Ega3 in GAG biosynthesis has yet to been determined; however, its putative localization at the cell surface is incongruent with activity on deacetylated GAG. The GAG polymer is predicted to remain fully acetylated until it reaches the cell wall where the deacetylase Agd3 is found. It is possible that the transmembrane helix tether is cleaved, thus allowing Ega3 to localize closer to deacetylated GAG. Further studies of the biological role of Ega3 are required to resolve these questions.

This study presents the first structure–function analysis of a GH114 family member, and it identifies the importance of the conserved aspartic and glutamic acid residues in catalysis (38). The studies presented herein will aid in the understanding of the other members of the GH114 family that are present throughout bacteria and fungi. Previously, it was shown that the GAG gene cluster, including ega3 orthologues, was present in numerous fungal plant pathogens and emerging human pathogens (6). GH114 members are found in many Streptomyces spp., a genus of industrial import that was cultivated for production of antibiotic, hydrolytic enzymes, and other biomolecules, as well as agricultural uses (63, 64). This includes Streptomyces lydicis and Streptomyces griseoviridis, which both encode GH114 enzymes and have been commercially developed as plant-growth–promoting products. It is possible that there is interplay in plant microbiomes between poly-α-1,4-galactosamine-producing organisms and those that encode GH114 enzymes to degrade them. Recently, glycoside hydrolases have been gaining attention as possible anti-biofilm agents (34, 35, 65–67). The activity of Ega3 against biofilms of A. fumigatus and P. aeruginosa suggests that this hydrolase may have potential therapeutic applications for the treatment of infections with these organisms.

Experimental procedures

Bioinformatics analysis of Ega3

The amino acid sequence of Ega3 from A. fumigatus was retrieved from the UniProt database and submitted to multiple web servers for analysis. The servers used were SignalP (68), BLASTP (29), Phyre2 (31), TMHMM (28), and dbCAN2 (30). ClustalOmega was used for sequence alignments (69, 70).

Ega3 expression and purification

A pUC57 plasmid containing an E. coli codon-optimized version of the gene encoding the extracellular region of A. fumigatus Ega3 (Ega346–318) was obtained from BioBasic. The ega346–318 gene was subcloned into the pET28a vector between the NdeI and XhoI sites. Expression trials of the predicted GH114 domain were attempted in E. coli BL21 and Origami cells. As no soluble protein was produced using this construct, primers 68NdeI, 72NdeI, and 75NdeI were paired with either 310HindIII or 318HindIII to generate shorter protein constructs (Table 2). As little to no soluble protein was obtained for any of these constructs and Ega3 is predicted to contain three N-glycosylation sites and possible disulfide bonds, protein expression was moved into yeast.

Table 2.

Strains and primers for Ega3

fwd is forward; rev is reverse.

| Sequence or description | Source or Ref. | |

|---|---|---|

| Primers | ||

| 68NdeI | GGGCATATGGGTAATTATACCACCGCAAAATGGCAG | This study |

| 72NdeI | GGGCATATGACCGCAAAATGGCAGCCTGCAGTTGGC | This study |

| 75NdeI | GGGCATATGTGGCAGATTGAACTGCTGTATGCACTG | This study |

| 310HindIII | CCAAGCTTTTACAGGTTCATGTTTTTGATGACGGTGCT | This study |

| 318HindIII | CCAAGCTTCTCGAGTTAGCAATATTCCACCCA | This study |

| His fwd | GGGAGTCATCGTATGGGCAGCAGCCATCATCATCATC | This study |

| Ega3 rev | GGGGGTACCGCAATATTCCACCCA | This study |

| D189A fwd | GGTGTTGATCCGGCAAATGTGGATG | This study |

| D189A rev | CATCCACATTTGCCGGATCAACACC | This study |

| D189N fwd | GTGTTGATCCGAATAATGTGGATGG | This study |

| D189N rev | CCATCCACATTATTCGGATCAACAC | This study |

| E247Q fwd | GGTCAGTTAATCAACAGTGTGCCCAG | This study |

| E247Q rev | CTGGGCACACTGTTGATTAACTGACC | This study |

| D192A fwd | GATAATGTGGCAGGCTATGATAATG | This study |

| D192A rev | CATTATCATAGCCTGCCACATTATC | This study |

| D195A fwd | GTGGATGGCTATGCAAATGATAATG | This study |

| D195A rev | CATTATCATTTGCATAGCCATCCAC | This study |

| D232A fwd | GAAAAATGCCGGTGCAATTATTCCG | This study |

| D232A rev | CGGAATAATTGCACCGGCATTTTTC | This study |

| E133D fwd | GCAGGCAGCTATGATAATTGGCGTC | This study |

| E133D rev | GACGCCAATTATCATAGCTGCCTGC | This study |

| E157S fwd | GATGATTGGCCTGGTAGCAAATGGC | This study |

| E157S rev | GCCATTTGCTACCAGGCCAATCATC | This study |

| E254Q fwd | CAGTATAATCAGTGTGATACCTATG | This study |

| E254Q rev | CATAGGTATCACACTGATTATACTG | This study |

| W154A fwd | CACGATCTGGATGATGCACCTGGTG | This study |

| W154A rev | CATTTTTCACCAGGTGCATCATCCAG | This study |

| W154F fwd | CACGATCTGGATGATTTTCCTGGTG | This study |

| W154F rev | CATTTTTCACCAGGAAAATCATCCAG | This study |

| Y126F fwd | GTAAAGTTATTTGTTTTCTTAGCGC | This study |

| Y126F rev | GCGCTAAGAAAACAAATAACTTTAC | This study |

| Y273F fwd | GTTTCATATCGAATTTCCGAAAGGC | This study |

| Y273F rev | GCCTTTCGGAAATTCGATATGAAAC | This study |

| Strains | ||

| Af293 | Wildtype pathogenic strain of A. fumigatus | 7 |

| PA14 | Wildtype pathogenic strain of P. aeruginosa | 90 |

| Pichia pink strain 4 | P. pastoris laboratory expression strain: ade2, prb1, pep4 | Novagen |

| TOP10 | E. coli cloning strain | Invitrogen |

| BL21 CodonPlus | E. coli laboratory expression strain: F− ompT hsdS (rB− mB−) dcm+ Tetr galλ (DE3) endA [argU proL Camr] | Stratagene |

| Origami2 (DE3) | E. coli laboratory expression strain: Tetr Strrλ (DE3),trbX gor | Stratagene |

The region including the N-terminal tag and the ega346–318 gene was cloned from the pET28a vector into the pPink α-HC vector between the StuI and KpnI sites using primers His Fwd and Ega3 Rev (Table 2). This resulted in a pPink α-HC plasmid encoding the α-factor signal sequence with the pET28a thrombin-cleavable hexahistidine tag N-terminal to Ega346–318. Point mutants Y126F, E133D, W154A, W154F, D189A, D189N, D192A, D195A, D232A, E247Q, E254Q, and Y273F were created from this plasmid using the QuikChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) with the primer pairs listed in Table 2. Sequences were confirmed at ACGT Corp. (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) with primers against the α-factor and CYC1-encoding regions. Plasmids were linearized either with AflII or SpeI in the TRP2 gene before transformation into PichiaPinkTM strain 4 (ade2, prb1, and pep4) by electroporation. Colonies of each clone, with the highest relative expression, were either restreaked and stored at 4 °C or used to make glycerol stocks and kept at −80 °C.

Large-scale expression of WT Ega346–318, or point mutants thereof, was carried out as outlined in the PichiaPinkTM expression system manual with minor modifications. Briefly, a 50-ml starter culture was grown in YPD (1% (w/v) yeast extract, 2% (w/v) peptone, 1% (w/v) dextrose) growth medium for about 20 h at 28 °C. The starter was added to 500 ml of BMGY (1% (w/v) yeast extract, 2% (w/v) peptone, 100 mm potassium phosphate, pH 6, 1.34% (w/v) yeast nitrogen base, 0.00004% (w/v) biotin, and 1% (v/v) glycerol) growth medium in a baffled Fernbach flask. Growth continued for 24 h at 28 °C with shaking. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 250 ml of BMMY media (BMGY without the glycerol) and incubated for a further 24 h. Expression was induced by the addition of methanol in three staggered feedings starting 1 h after resuspension, at 1-h intervals, to a final concentration of 1% (v/v) methanol. After harvesting, the supernatant containing the secreted protein was filtered through a Whatman filter. The sample was then buffered with HEPES, pH 8, to a final concentration of 20 mm.

The protein was purified using a two-step procedure: ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). Ega3 was precipitated with 80% (w/v) ammonium sulfate at 4 °C, and the precipitate was pelleted at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The precipitate was resuspended in SEC Buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl), and the ammonium sulfate was removed by dialysis, prior to loading the sample and purification using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 prep-grade column (GE Healthcare). This expression and purification protocol yielded ∼5 mg of Ega3 for every 1 liter of media.

For untagged Ega3, the purification procedure was modified. First, the ammonium sulfate precipitation step was replaced, and the His-tagged protein was isolated using nickel-affinity chromatography. The eluent from the Ni-NTA column was subsequently buffer-exchanged into standard SEC buffer. The hexahistidine tag was cleaved with thrombin by incubating for 24 h at 4 °C prior to a second round of Ni-affinity chromatography. Unbound (untagged protein) was then purified by SEC as described for the tagged protein. This method had much lower and inconsistent yields and thus was only used for crystal trials. Protein purity and concentration were determined by SDS-PAGE and the bicinchoninic acid assay, respectively.

Ega3 crystallization and data collection

Purified Ega346–318 with and without the N-terminal hexahistidine tag was concentrated to 12.8 and 11 mg/ml, respectively. Crystallization conditions were screened in 3-μl drops at a (1:1) ratio of Ega3 to mother liquor, using hanging-drop vapor diffusion in VDX 48-well plates (Hampton). Crystals formed in over a third of the conditions in the MCSG suite #1 (Microlytics). Two crystal forms were dominant: singular rods and flat rectangles. A crystal of untagged Ega3 crystallized from MCSG 1 #86 was cryoprotected in 25% (v/v) PEG 3350 and 50% (v/v) mother liquor (0.2 m potassium iodide, 20% (v/v) PEG 3350) for 30 s before vitrification in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at a wavelength of 0.9794 Å at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) using beamline 08B1-1. 720 images of 0.5° oscillation were collected on a Rayonix MX300 CCD detector with an exposure time of 2.0 s per image. The data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using Autoprocess (Table 1) (71, 72). Phasing was achieved using the distant homologue TM1410 (PDB 2AAM) as a template for ARCIMBOLDO_SHREDDER (73). TM1410 was identified by HHPRED (74) as the most similar structure available with about 17% sequence identity to Ega3. ARCIMBOLDO_SHREDDER performed expected log-likelihood gain-guided placement of template-derived fragments with Phaser (75, 76). Additional degrees of freedom, including gyre refinement, against the rotation function, and gimble refinement, after placement, were used to refine fragment location during molecular replacement (77). Consistent fragments were combined in reciprocal space with ALIXE (78). Best-scored phase sets were subject to density modification, and autotracing with SHELXE (79) led to a main-chain trace comprising 225 residues and characterized by a CC of 35%. Side chains were added in Coot (80) followed by iterative rounds of structure refinement in PHENIX.REFINE (81) and manual building in Coot. The TLSMD server was used to create three TLS groups that were used in refinement.

Ega3 co-crystallization, crystal soaking, and data collection

Co-crystallization of Ega3 with galactosamine or GalNAc using the previous hit conditions in 2–3 μl at 1:1 ratio hanging drop vapor–diffusion were attempted as described above. Crystal screens were set up to final concentrations of 275, 330, and 550 mm galactosamine, or 200, 250, and 500 mm GalNAc. Multiple crystal formed in these conditions, and data were collected at NSLS II on the AMX beamline (17ID-1).

Apo-crystals were grown in MCSG 1 #18 (0.2 m calcium acetate, 0.1 m MES, pH 6.0, and 20% (v/v) PEG 8000) at 9–10 mg/ml Ega3 as described above. These crystals were soaked in varying concentrations of galactosamine or GalNAc supplemented MCSG 1 #18. Crystals were vitrified in liquid nitrogen with the monosaccharides acting as cryo-protectant. Crystals were screened, and data were collected at NSLS II on the AMX beamline (ID17-1). A data set was collected on a crystal soaked in 550 mm galactosamine (0.2° oscillations, 360°, 0.01 s/image) and processed using fast_dp (82–85). The structure was solved using molecular replacement with apo-Ega3 as the search model. Iterative rounds of model building and refinement were performed as described above for the apo structure using PHENIX and Coot, accessed through the SBGrid (80, 81, 86, 87).

Biofilm disruption assays

Biofilm assays were completed as described previously (35). Briefly, 105 conidia of WT A. fumigatus Af293 were grown in Brian media in polystyrene, 96-well plates nontissue culture-treated for 21 h at 37 °C. Biofilms were treated with the indicated concentration of WT or mutant Ega3 in 1× PBS for 1 h at room temperature under gentle agitation. Biofilms were then washed, and the remaining biomass was stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet and destained with 100% ethanol for 10 min. The optical density of the destain solution was measured at 600 nm.

Ega3 degradation of secreted GAG

Secreted GAG was purified as reported previously (6). Briefly, culture supernatants of 3-day-old Af293 or Af293 Δagd3 cultures were filtered on Miracloth prior to ethanol-precipitation. Precipitate was then washed with 70% (v/v) ethanol twice, 150 mm NaCl, and then water. The precipitate was then freeze-dried. 1 mg of precipitated secreted GAG was resuspended in 500 μl of 1× PBS containing 1 μm Ega3 or 1 μm Sph3. After incubating for 1 h, the sample was dried and reduced then propionylated. Reduction was performed incubating the oligosaccharides in 10 mg/ml sodium borohydride in 1 m ammonium hydroxide overnight at room temperature. Reaction was then quenched with 30% acetic acid prior to the propionylation reaction. Oligosaccharides were resuspended in methanol/pyridine/propionic anhydride (10:2:3) for 1 h at room temperature. Reduced and propionylated oligosaccharides were then purified using the Hypercarb Hypersep SPE cartridge and eluted with 50% (v/v) acetonitrile (ACN). Dried elute was resuspended in 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and spotted on the MALDI-TOF plate in a ratio of 1:1 (v/v) with 5 mg/ml 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid matrix reconstituted in ACN, 0.2% (v/v) TFA (70:30, v/v). Spectra were recorded on a Bruker UltrafleXtreme in positive reflector mode and an accumulation of 5000 laser shots.

Production of α-1,4-Gal, α-1,4-GalN, α-1,4-GalNAc, β-1,4-GlcNAc/GlcN, and β-1,6-GlcNAc oligosaccharides and specificity assays

α-1,4-GalNAc oligosaccharides were obtained by partial Sph3 hydrolysis of A. fumigatus biofilm. Then, 21-h-old biofilms were incubated with 5 nm Sph3 for 1 h at room temperature, and solubilized oligosaccharides were then further purified on a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge. Briefly, cartridges were conditioned using absolute ethanol followed by water. Samples were then loaded onto the cartridge before washing and eluting using 2% ACN. α-1,4-Linked Gal and GalN oligosaccharides were synthesized as described previously (18). β-1,4-GlcNAc/GlcN was produced by partial hydrolysis of chitin from shrimp shell. Briefly, 1 mg of chitin was incubated with 0.1 m HCl at 100 °C for 3 h prior to being neutralized and purified on Carbograph Sep-Pak. β-1,6-GlcNAc oligosaccharides were synthesized as described previously (39). A mixture of the longest oligomers obtained, β-1,6-(GlcNAc)9 to β-1,6-(GlcNAc)12, was used in this study. All oligosaccharides were incubated with 10 μm Ega3 for 24 h at room temperature prior to analyzing by MALDI-TOF MS, as described above.

In silico docking of GalN oligosaccharide

The Ega3–GalN structure was prepared using the Protein Preparation Wizard (88) in the Schrodinger suite after the removal of the bound galactosamine monomer. Receptor tautomeric and protonation state was optimized for pH 7.0. The α-1,4-GalN ligand was created in Coot (80) by removing the acetate groups from an α-1,4-(GalNAc)5 molecule that had been built using the Glycam Carbohydrate Builder. Ligand preparation was done using LigPrep from Schrodinger suite with OPLS2005 force field and charges at pH 7.0 to create 512 tautomers. Docking was executed by Glide (41–43) with default setting, and results were viewed through Maestro (Maestro, Schrödinger, LLC, New York). Highest-scoring ligand conformers were exported for figure creation in PyMOL (Version 2.0.7).

Author contributions

N. C. B., F. L. M., D. C. S., and P. L. H. conceptualization; N. C. B., F. L. M., D. C. S., and P. L. H. formal analysis; N. C. B., F. L. M., A. S. S., P. Y., C. M., C. Z., and I. U. investigation; N. C. B., D. C. S., and P. L. H. writing-original draft; N. C. B., F. L. M., A. S. S., P. Y., C. M., Y. Z., C. Z., M. N., J. D. C., I. U., D. C. S., and P. L. H. writing-review and editing; Y. Z., A. F., M. N., and J. D. C. resources; D. C. S. and P. L. H. supervision; D. C. S. and P. L. H. funding acquisition; D. C. S. and P. L. H. project administration.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Drug Discovery Platform of the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Center for the use of the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer. We also thank the Structural and Biophysical Core Facility at the Hospital for Sick Children for the use of the X-ray crystallography equipment. Beamline 08B1-1 at the Canadian Light Source is supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Research Council of Canada, the Province of Saskatchewan, Western Economic Diversification Canada, and the University of Saskatchewan. The Life Science Biomedical Technology Research resource at NSLS-II is primarily supported by the National Institutes of Health, NIGMS, through a Biomedical Technology Research Resource P41 Grant P41GM111244 and by the Department of Energy Office of Biological and Environmental Research Grant KP1605010. Funds for the X-ray facilities at The Hospital for Sick Children were provided in part by the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and the Government of Ontario.

This work was supported in part by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating Grants 81361 (to P. L. H. and D. C. S.), FDN-154327 and 43998 (to P. L. H.), 123306 and FDN-159902 (to D. C. S.), and 89708 (to M. N.); Cystic Fibrosis Canada (to D. C. S. and P. L. H.); and European Research Council Grant ERC-CoG-726072-GLYCONTROL (to J. D. C. C.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article was selected as one of our Editors' Picks.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- GAG

- galactosaminogalactan

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- GH

- glycoside hydrolase

- PNAG

- poly-β-1,6-GlcNAc

- RMSD

- root-mean-square deviation

- SEC

- size-exclusion chromatography

- ACN

- acetonitrile.

References

- 1. Kaur S., and Singh S. (2014) Biofilm formation by Aspergillus fumigatus. Med. Mycol. 52, 2–9 10.3109/13693786.2013.819592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown G. D., Denning D. W., Gow N. A., Levitz S. M., Netea M. G., and White T. C. (2012) Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 165rv13 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stevens D. A., Moss R. B., Kurup V. P., Knutsen A. P., Greenberger P., Judson M. A., Denning D. W., Crameri R., Brody A. S., Light M., Skov M., Maish W., Mastella G., Participants in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Conference (2003) Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis–state of the art: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Conference. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37, Suppl., 3, S225–S264 10.1086/376525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knutsen A. P., and Slavin R. G. (1990) Cystic Fibrosis (Richard B.S., ed) Vol 1, pp. 103–118, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ: 10.1007/978-1-4612-0475-6_7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gresnigt M. S., Bozza S., Becker K. L., Joosten L. A., Abdollahi-Roodsaz S., van der Berg W. B., Dinarello C. A., Netea M. G., Fontaine T., De Luca A., Moretti S., Romani L., Latge J. P., and van de Veerdonk F. L. (2014) A polysaccharide virulence factor from Aspergillus fumigatus elicits anti-inflammatory effects through induction of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1003936 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee M. J., Geller A. M., Bamford N. C., Liu H., Gravelat F. N., Snarr B. D., Le Mauff F., Chabot J., Ralph B., Ostapska H., Lehoux M., Cerone R. P., Baptista S. D., Vinogradov E., Stajich J. E., Filler S. G., et al. (2016) Deacetylation of fungal exopolysaccharide mediates adhesion and biofilm formation. MBio. 7, e00252–16 10.1128/mBio.00252-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gravelat F. N., Beauvais A., Liu H., Lee M. J., Snarr B. D., Chen D., Xu W., Kravtsov I., Hoareau C. M., Vanier G., Urb M., Campoli P., Abdallah Al Q., Lehoux M., Chabot J. C., et al. (2013) Aspergillus galactosaminogalactan mediates adherence to host constituents and conceals hyphal β-glucan from the immune system. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003575 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee M. J., Liu H., Barker B. M., Snarr B. D., Gravelat F. N., Al Abdallah Q., Gavino C., Baistrocchi S. R., Ostapska H., Xiao T., Ralph B., Solis N. V., Lehoux M., Baptista S. D., Thammahong A., et al. (2015) The fungal exopolysaccharide galactosaminogalactan mediates virulence by enhancing resistance to neutrophil extracellular traps. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005187 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Briard B., Muszkieta L., Latgé J.-P., and Fontaine T. (2016) Galactosaminogalactan of Aspergillus fumigatus, a bioactive fungal polymer. Mycologia 108, 572–580 10.3852/15-312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robinet P., Baychelier F., Fontaine T., Picard C., Debré P., Vieillard V., Latgé J.-P., and Elbim C. (2014) A polysaccharide virulence factor of a human fungal pathogen induces neutrophil apoptosis via NK cells. J. Immunol. 192, 5332–5342 10.4049/jimmunol.1303180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fontaine T., Delangle A., Simenel C., Coddeville B., van Vliet S. J., van Kooyk Y., Bozza S., Moretti S., Schwarz F., Trichot C., Aebi M., Delepierre M., Elbim C., Romani L., and Latgé J.-P. (2011) Galactosaminogalactan, a new immunosuppressive polysaccharide of Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002372 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Glasgow J. E., and Reissig J. L. (1974) Interaction of galactosaminoglycan with Neurospora conidia. J. Bacteriol. 120, 759–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jorge J. A., de Almeida E. M., de Lourdes Polizeli M., and Terenzi H. F. (1999) Changes in N-acetylgalactosaminoglycan deacetylase levels during growth of Neurospora crassa: effect of l-sorbose on enzyme production. J. Basic Microbiol. 39, 337–344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Takagi H., and Kadowaki K. (1985) Purification and chemical properties of a flocculant produced by Paecilomyces. Agri. Biol. Chem. 49, 3159–3164 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guerrero C., Prieto A., and Leal J. A. (1988) Extracellular galactosaminogalactan from Penicillium frequentans. Microbiologia 4, 39–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bamford N. C., Snarr B. D., Gravelat F. N., Little D. J., Lee M. J., Zacharias C. A., Chabot J. C., Geller A. M., Baptista S. D., Baker P., Robinson H., Howell P. L., and Sheppard D. C. (2015) Sph3 is a glycoside hydrolase required for the biosynthesis of galactosaminogalactan in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 27438–27450 10.1074/jbc.M115.679050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee M. J., Gravelat F. N., Cerone R. P., Baptista S. D., Campoli P. V., Choe S. I., Kravtsov I., Vinogradov E., Creuzenet C., Liu H., Berghuis A. M., Latgé J. P., Filler S. G., Fontaine T., and Sheppard D. C. (2014) Overlapping and distinct roles of Aspergillus fumigatus UDP-glucose 4-epimerases in galactose metabolism and the synthesis of galactose-containing cell wall polysaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 1243–1256 10.1074/jbc.M113.522516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le Mauff F., Bamford N. C., Alnabelseya N., Zhang Y., Baker P., Robinson H., Codée J. D., Howell P. L., and Sheppard D. C. (2019) Molecular mechanism of Aspergillus fumigatus biofilm disruption by fungal and bacterial glycoside hydrolases. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 10760–10772 10.1074/jbc.RA119.008511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muszkieta L., Beauvais A., Pähtz V., Gibbons J. G., Anton Leberre V., Beau R., Shibuya K., Rokas A., François J. M., Kniemeyyer O., Brakhage A. A., and Latgé J.-P. (2013) Investigation of Aspergillus fumigatus biofilm formation by various “omics” approaches. Front. Microbiol. 4, 13 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henrissat B. (1991) A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem. J. 280, 309–316 10.1042/bj2800309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bourne Y., and Henrissat B. (2001) Glycoside hydrolases and glycosyltransferases: families and functional modules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11, 593–600 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00253-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vuong T. V., and Wilson D. B. (2010) Glycoside hydrolases: catalytic base/nucleophile diversity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 107, 195–205 10.1002/bit.22838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tamura J.-I., Hasegawa K., Kadowaki K., Igarashi Y., and Kodama T. (1995) Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding an endo α-1,4 polygalactosaminidase of Pseudomonas sp. 881. J. Ferm. Bioengin. 80, 305–310 10.1016/0922-338X(95)94196-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tamura J.-I., Takagi H., and Kadowaki K. (1988) Purification and some properties of the endo α-1,4 polygalactosaminidase from Pseudomonas sp. Agri. Biol. Chem. 52, 2475–2484 10.1080/00021369.1988.10869068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tamura J., Abe T., Hasegawa K., and Kadowaki K. (1992) The mode of action of endo α-1,4 polygalactosaminidase from Pseudomonas sp. 881 on galactosaminooligosaccharides. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 56, 380–383 10.1271/bbb.56.380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reissig J. L., Lai W.-H., and Glasgow J. E. (1975) An endogalactosaminidase of Streptomyces griseus. Can. J. Biochem. 53, 1237–1249 10.1139/o75-169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davies G., and Henrissat B. (1995) Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases. Structure 3, 853–859 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00220-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., and Sonnhammer E. L. (2001) Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., and Lipman D. J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang H., Yohe T., Huang L., Entwistle S., Wu P., Yang Z., Busk P. K., Xu Y., and Yin Y. (2018) dbCAN2: a meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W95–W101 10.1093/nar/gky418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kelley L. A., and Sternberg M. J. (2009) Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat. Protoc. 4, 363–371 10.1038/nprot.2009.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blom N., Sicheritz-Pontén T., Gupta R., Gammeltoft S., and Brunak S. (2004) Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics 4, 1633–1649 10.1002/pmic.200300771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Holm L., and Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549 10.1093/nar/gkq366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baker P., Hill P. J., Snarr B. D., Alnabelseya N., Pestrak M. J., Lee M. J., Jennings L. K., Tam J., Melnyk R. A., Parsek M. R., Sheppard D. C., Wozniak D. J., and Howell P. L. (2016) Exopolysaccharide biosynthetic glycoside hydrolases can be utilized to disrupt and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501632 10.1126/sciadv.1501632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Snarr B. D., Baker P., Bamford N. C., Sato Y., Liu H., Lehoux M., Gravelat F. N., Ostapska H., Baistrocchi S. R., Cerone R. P., Filler E. E., Parsek M. R., Filler S. G., Howell P. L., and Sheppard D. C. (2017) Microbial glycoside hydrolases as antibiofilm agents with cross-kingdom activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 7124–7129 10.1073/pnas.1702798114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jennings L. K., Storek K. M., Ledvina H. E., Coulon C., Marmont L. S., Sadovskaya I., Secor P. R., Tseng B. S., Scian M., Filloux A., Wozniak D. J., Howell P. L., and Parsek M. R. (2015) Pel is a cationic exopolysaccharide that cross-links extracellular DNA in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 11353–11358 10.1073/pnas.1503058112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baker P., Whitfield G. B., Hill P. J., Little D. J., Pestrak M. J., Robinson H., Wozniak D. J., and Howell P. L. (2015) Characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa glycoside hydrolase PslG reveals that its levels are critical for psl polysaccharide biosynthesis and biofilm formation. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 28374–28387 10.1074/jbc.M115.674929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Naumoff D. G., and Stepuschenko O. O. (2011) Endo-α-1,4-polygalactosaminidases and their homologs: structure and evolution. Mol. Biol. 45, 647–657 10.1134/S0026893311030113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leung C., Chibba A., Gómez-Biagi R. F., and Nitz M. (2009) Efficient synthesis and protein conjugation of β-(1→6)-d-N-acetylglucosamine oligosaccharides from the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin. Carbohydr. Res. 344, 570–575 10.1016/j.carres.2008.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cywes-Bentley C., Skurnik D., Zaidi T., Roux D., Deoliveira R. B., Garrett W. S., Lu X., O'Malley J., Kinzel K., Zaidi T., Rey A., Perrin C., Fichorova R. N., Kayatani A. K., Maira-Litràn T., et al. (2013) Antibody to a conserved antigenic target is protective against diverse prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E2209–E2218 10.1073/pnas.1303573110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Friesner R. A., Banks J. L., Murphy R. B., Halgren T. A., Klicic J. J., Mainz D. T., Repasky M. P., Knoll E. H., Shelley M., Perry J. K., Shaw D. E., Francis P., and Shenkin P. S. (2004) Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 47, 1739–1749 10.1021/jm0306430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Friesner R. A., Murphy R. B., Repasky M. P., Frye L. L., Greenwood J. R., Halgren T. A., Sanschagrin P. C., and Mainz D. T. (2006) Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein–ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem. 49, 6177–6196 10.1021/jm051256o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Halgren T. A., Murphy R. B., Friesner R. A., Beard H. S., Frye L. L., Pollard W. T., and Banks J. L. (2004) Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 2. Enrichment factors in database screening. J. Med. Chem. 47, 1750–1759 10.1021/jm030644s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wakarchuk W. W., Campbell R. L., Sung W. L., Davoodi J., and Yaguchi M. (1994) Mutational and crystallographic analyses of the active-site residues of the Bacillus circulans xylanase. Protein Sci. 3, 467–475 10.1002/pro.5560030312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McCarter J. D., and Withers S. G. (1994) Mechanisms of enzymatic glycoside hydrolysis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 4, 885–892 10.1016/0959-440X(94)90271-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. You X., Qin Z., Li Y.-X., Yan Q.-J., Li B., and Jiang Z.-Q. (2018) Structural and biochemical insights into the substrate-binding mechanism of a novel glycoside hydrolase family 134 β-mannanase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1862, 1376–1388 10.1016/j.bbagen.2018.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Alhassid A., Ben-David A., Tabachnikov O., Libster D., Naveh E., Zolotnitsky G., Shoham Y., and Shoham G. (2009) Crystal structure of an inverting GH 43 1,5-α-l-arabinanase from Geobacillus stearothermophilus complexed with its substrate. Biochem. J. 422, 73–82 10.1042/BJ20090180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Davies G. J., Brzozowski A. M., Dauter M., Varrot A., and Schülein M. (2000) Structure and function of Humicola insolens family 6 cellulases: structure of the endoglucanase, Cel6B, at 1.6 A resolution. Biochem. J. 348, 201–207 10.1042/bj3480201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]