ABSTRACT

Background. Health insurers are well-positioned to address low HPV vaccination coverage in the US through initiatives such as provider assessment and feedback. However, little is known about the feasibility of using administrative claims data to assess provider performance on vaccine delivery.

Methods. We used administrative claims data from a regional health plan to estimate provider performance on the 2013–2015 Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measure for HPV vaccine. This measure required that a girl receive three doses of HPV vaccine by age 13. Providers who administered ≥1 dose in a HEDIS-consistent series received credit for meeting the goal.

Results. From January 2008-April 2015, 1,975 (8.5%) of 11–12 year-old girls in our sample received a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series. Our sample of providers consisted of 1,236 who had ≥10 well-visits with different female patients, and 94% of these were pediatricians. A substantial minority of providers (39.4%) did not administer any HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine doses. Only 5.5% of providers administered HPV vaccine doses that were part of a HEDIS-consistent series to at least one-quarter of their patients. These estimates did not vary by provider sex or age. Doses in a HEDIS-consistent vaccine series were often attributed to multiple providers.

Conclusions. In a regional health plan, only 5.5% of providers in our sample administered doses that were part of a complete, three-dose HPV vaccine series to at least one-quarter of their 11–12 year-old female patients.

KEYWORDS: Adolescent health, human papillomavirus infections/prevention & control, human papillomavirus vaccine, administrative claims, healthcare, healthcare providers, vaccination coverage

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage in the US continues to fall short of national goals, with just 65% of 13-year-old girls and 57% of boys the same age initiating the multi-dose series by 2017.1 To raise coverage, public health experts have prioritized the goal of engaging health insurers in quality improvement (QI) activities such as provider assessment and feedback.2 Using administrative claims data, health insurers are uniquely positioned to contribute to HPV vaccination QI given their ability to assess members’ vaccination status.

The introduction of the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) HPV vaccine measure in 2013 provides additional support and incentive for insurer involvement.3,4 Briefly, the HEDIS HPV vaccine measures for 2013–2015 estimate the percentage of 13 year-old female health plan members who receive three doses of HPV vaccine by their 13th birthday.3,4 From 2013–2015, the NCQA reported the national HEDIS HPV vaccine measures among commercial payers participating in preferred provider organization (PPO) plans to be only 11.0%, 12.9%, 14.0%, respectively.4 Estimates from health maintenance organization (HMO) plans were approximately three percentage points higher each year.4 Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends only two doses of HPV for young adolescents,5,6 completion of the HPV vaccine series remains an important public health goal.7

Little is known about the feasibility of using administrative claims databases to support provider assessment on HEDIS-consistent delivery of HPV vaccine. Such information could be used to inform targeted QI initiatives and other research priorities (e.g., facilitate investigating top-performing providers’ vaccine delivery and communication strategies). Thus, we used administrative claims from a large, non-profit regional health insurer to estimate provider-level HPV vaccine coverage estimates consistent with the 2013–2015 HEDIS quality measure.

Results

HPV vaccination

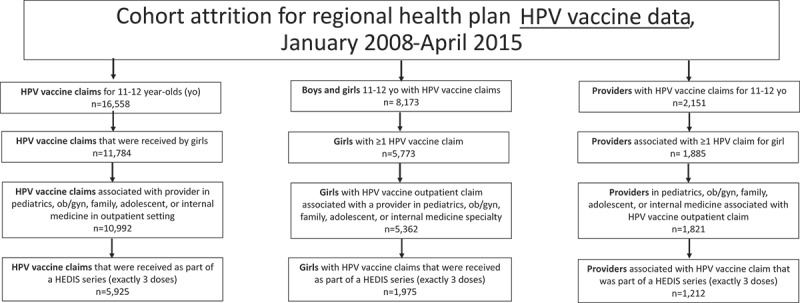

From January 1, 2008- April 30, 2015, 10,992 doses of HPV vaccine were administered to 5,362 unique 11–12 year-old girls among an eligible population of 23,346 girls (Figure 1). Among the 23,346 girls, 1,975 (8.5%) completed a three-dose series by their 13th birthday (Table 1). The 1,975 girls with a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series received their first dose from one of 888 performing providers; since a total of 1,212 performing providers were involved in administering any HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine dose, these results highlight how multiple providers are involved in the administration and completion of such series. An estimated 91.7% (1,812/1,975) of girls with a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series received their first dose on the day of a well-visit (versus an acute care or other visit). The second and third HPV vaccine doses were administered at well-visits less frequently at 20.9% (413/1,975) and 30.8% (608/1,975), respectively.

Figure 1.

Attrition of claims, health plan members, and providers associated with HPV vaccinations in study cohort, regional health plan data, January 2008- April 2015.

Table 1.

HPV vaccine doses delivered to female patients aged 11–12 years-old, January 2008-April 2015.

| Total doses (n) | Female health plan members, 11–12 years-old (n, %) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 17,984 (77.0) |

| 1 | 1,739 (7.4) |

| 2 | 1,632 (7.0) |

| 3 | 1,975 (8.5) |

| 4 | 16 (0.1) |

| Total | 23,346 (100) |

Provider patient populations and well-visits

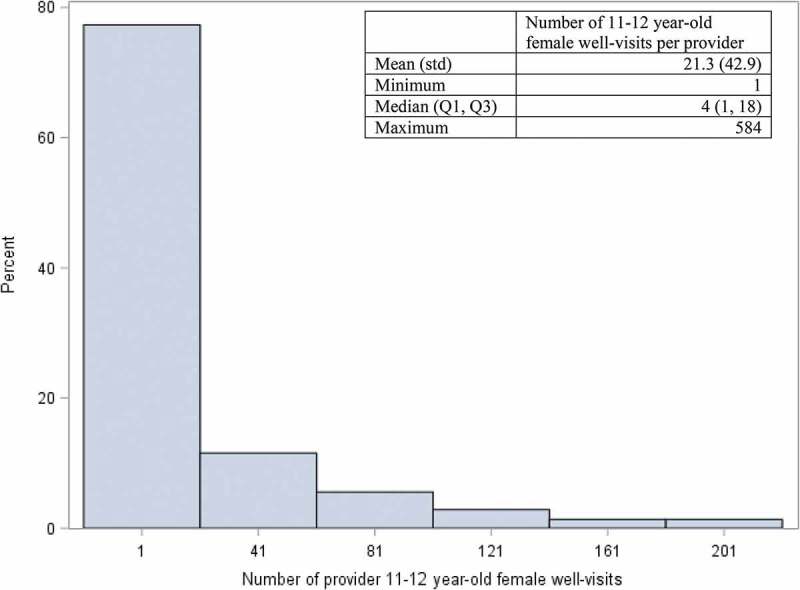

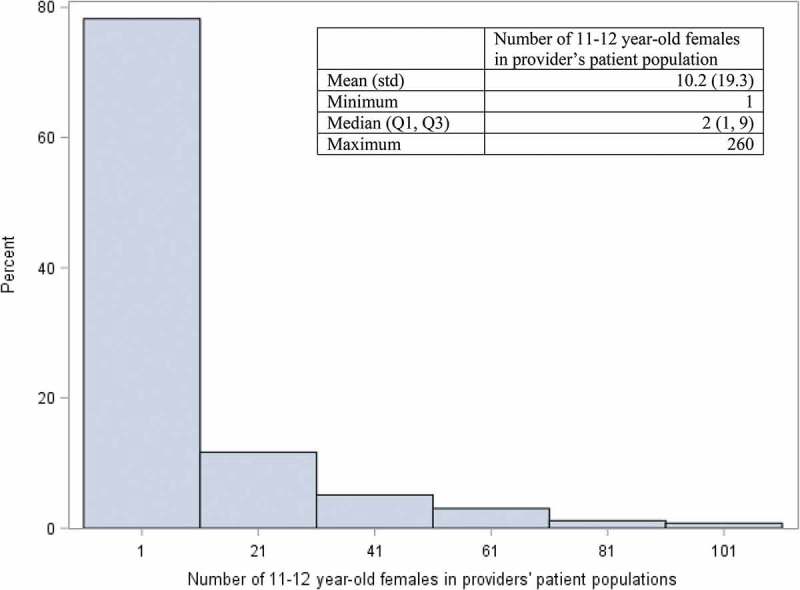

During the study period, 5,086 providers in the selected specialties had ≥1 well-visit with a female patient 11–12 years-old (median: 4 well-visits, IQR: 1–18) (Figure 2) and cared for ≥1 unique female patient(s) 11–12 years-old during a well-visit encounter (median: 2 patients, IQR: 1–9) (Figure 3). Approximately one-quarter (n = 1,236) of the 5,086 providers had ≥10 well-visits with different female patients 11–12 years-old. The vast majority of providers with higher volumes of well-visits and patients were pediatricians (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution* of 11–12 year-old female well visits among providers with ≥1 well-visit in a regional health plan, January 1, 2008- April 30, 2015 (n = 5,086 providers).

*The graph is truncated. The maximum number of well-visits per provider was 584.

Figure 3.

Distribution* of female patients ages 11–12 years among providers with ≥1 patient cared for at a well-visit in a regional health plan, January 1, 2008- April 30, 2015 (n = 5,086 providers).

*The graph is truncated. The maximum number of patients in a provider’s population was 260.

Table 2.

Characteristics of providers serving female patients aged 11–12 years-old at well visits, January 2008- April 2015.

| Characteristics | Providers with ≥1 well visit, n (%) |

Providers with ≥10 well visits with different patients, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 5,086 (100) | 1,236 (100) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 2,620 (51.5) | 718 (58.1) |

| Male | 1,853 (36.4) | 509 (41.2) |

| Other/unknown | 613 (12.1) | 9 (0.7) |

| Birth Decade | ||

| <1950s | 529 (11.9) | 190 (15.4) |

| 1950s | 1,135 (25.4) | 321 (26.0) |

| 1960s | 1,304 (29.2) | 388 (31.4) |

| ≥1970s | 1,494 (33.5) | 336 (27.2) |

| Missing | 624 | 1 |

| Primary Specialty | ||

| Pediatrics | 2,821 (55.5) | 1,167 (94.4) |

| Family Medicine | 1,863 (36.6) | 59 (4.8) |

| Internal Medicine | 284 (5.6) | 9 (0.7) |

| Ob/gyn | 100 (2.0) | 1 (0) |

| Adolescent Medicine | 18 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

Provider coverage estimates

Overall, 39.4% (487/1,236) of providers with ≥10 well-visits among unique female patients 11–12 years-old did not administer a HPV vaccine dose in a HEDIS-consistent series (Table 3). Only 5.5% of providers administered HPV vaccine doses that contributed to a HEDIS-consistent series in one-quarter of their patients or more, and only 3.8% of providers administered such doses at a minimum of one-quarter of their well-visits; these estimates did not independently vary by provider sex or age. There was a high correlation when using providers’ number of patients versus number of well-visits to estimate HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine coverage rates (r = 0.92). The top ten performing providers administered HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccinations to 42.9%- 75.0% of their patients.

Table 3.

Estimated number and percentage of providers’ 11-12 year-old female patient populations and well visits meeting HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccination standards, by sex and birth decade, January 2008-April 2015 (n = 1,236 providers).

| Characteristics | 0% | >0-<5% | 5-<10% | 10-<25% | ≥25% | χ2 (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis: number and percentage of providers’ patients where a dose in a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series was provided | ||||||

| Sex | 0.54 (0.97) | |||||

| Female | 278 (38.7) | 118 (16.4) | 150 (20.9) | 131 (18.3) | 41 (5.7) | |

| Male | 205 (40.3) | 84 (16.5) | 101 (19.8) | 93 (18.3) | 26 (5.1) | |

| Other* | 4 (44.4) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Birth Decade | 7.98 (0.79) | |||||

| <1950’s | 77 (40.5) | 30 (15.8) | 38 (20.0) | 32 (16.8) | 13 (6.8) | |

| 1950’s | 121 (37.7) | 63 (19.6) | 61 (19.0) | 59 (18.4) | 17 (5.3) | |

| 1960’s | 160 (41.2) | 61 (15.7) | 79 (20.4) | 72 (18.6) | 16 (4.1) | |

| ≥1970’s | 128 (38.1) | 50 (14.9) | 74 (22.0) | 62 (18.5) | 22 (6.6) | |

| Total | 487 (39.4) | 204 (16.5) | 252 (20.4) | 225 (18.2) | 68 (5.5) | |

| Secondary analysis: number and percentage of providers’ well-visits where a dose in a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series was provided | ||||||

| Sex | 1.52 (0.82) | |||||

| Female | 278 (38.7) | 176 (24.5) | 126 (17.6) | 111 (15.5) | 27 (3.8) | |

| Male | 205 (40.3) | 121 (23.8) | 78 (15.3) | 86 (16.9) | 19 (3.7) | |

| Other* | 4 (44.4) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Birth Decade | ||||||

| <1950’s | 77 (40.5) | 46 (24.2) | 27 (14.2) | 32 (16.8) | 8 (4.2) | 5.40 (0.94) |

| 1950’s | 121 (37.7) | 84 (26.2) | 51 (15.9) | 53 (16.5) | 12 (3.7) | |

| 1960’s | 160 (41.2) | 90 (23.2) | 71 (18.3) | 53 (13.7) | 14 (3.6) | |

| ≥1970’s | 128 (38.1) | 78 (23.2) | 57 (17.0) | 60 (17.9) | 13 (3.9) | |

| Total | 487 (39.4) | 298 (24.1) | 206 (16.7) | 198 (16.0) | 47 (3.8) | |

*Excluded from Pearson’s Chi-square calculation

HEDIS estimates

Estimated HEDIS HPV vaccine rates from 2013 (11.4%) and 2014 (10.1%) were comparable to national estimates reported for commercial PPO plans (11.0% in 2013 and 12.9% in 2014)4 and slightly lower than national estimates reported for commercial HMO plans (14.2% in 2013 and 16.6% in 2014)4 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage of female population 11–12 years-old meeting the 2013–2015 Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) standard for HPV vaccine.

| Year* | Regional insurer study estimates, all commercial plan types (%) | National published estimates, commercial PPO plans (%)4 | National published estimates, commercial HMO plans (%)4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 5.9 | NA | NA |

| 2009 | 8.0 | NA | NA |

| 2010 | 6.6 | NA | NA |

| 2011 | 7.4 | NA | NA |

| 2012 | 8.5 | NA | NA |

| 2013 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 14.2 |

| 2014 | 10.1 | 12.9 | 16.6 |

*2015 was excluded because only a partial year of study data was available

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use claims data to characterize provider coverage estimates and characteristics associated with HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccination. Consistent with low national HEDIS estimates for HPV vaccine uptake among 11–12 year-old girls from 2013–2015,4 we found that approximately 94.5% of providers had HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine coverage estimates of <25%, which did not vary by provider sex or age. Consistent with clinical practice, the HPV vaccine series was commonly initiated at a well-visit, while second and third doses were provided at well-visits less frequently.

Other studies have shown the importance of the provider influence on HPV vaccine uptake, including the provider recommendation.8,9 Our study found that often more than one provider may be involved in the completion of a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series, underscoring the need to identify and target healthcare teams when designing interventions and initiating quality improvement initiatives to increase rates of HPV vaccination. Nonetheless, a patient’s primary healthcare provider likely remains a key influence overseeing the completion of a HPV vaccine series, independent of whether that provider administered any of the doses. Additional provider-level characteristics described in other studies that may be important to consider when planning provider-level interventions to increase HPV vaccine coverage include providers’ specialty10; providers’ views on HPV vaccine effectiveness (e.g., waning immunity);10 provider self-efficacy;11 and providers’ perception of parental importance of HPV vaccine relative to the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) and meningococcal vaccines.12

Claims data represent a largely untapped source of provider information that could help enroll providers or provider networks in interventions or help rapidly target quality improvement initiatives at a low cost. However, certain challenges exist in the context of a multi-payer system. First, data from a single, regional health insurer offers only a partial view of providers’ patient populations. While larger claims databases may increase the proportion of providers’ patient populations in a dataset, it may still be difficult to determine whether the identified patients are representative of the provider’s entire patient population. State-based all-payer claims databases (APCDs) have promise in overcoming these limitations because they systematically collect health care claims data from most types of payers (e.g., commercial and public insurance plans).13 However, they are not yet implemented in every state and provider IDs might not be consistent across the aggregated claims data.13

Second, to ensure that we captured HPV vaccinations that were HEDIS-consistent, we required patients to have continuous enrollment in the insurance plan for two years at ages 11–12 years-old and further required ≥1 well-visit to indicate that they were active users of their health plan (i.e., ensure that patients were not utilizing another health plan, if dually enrolled in another plan). Despite these requirements, some patients may have received a HPV vaccine from a source that did not bill the health insurer that we studied, such as a school system or public health clinic. However, since the HPV vaccine is expensive out-of-pocket14 and HPV vaccine doses in pediatric patients are not commonly administered in school settings15 or pharmacies,16 it is likely that most HPV vaccines received at ages 11–12 years-old were captured in our study. Of note, since HPV vaccination can be delivered as young as 9 years of age,8 we ideally would have required four years of enrollment, from ages 9–12 years, to avoid potentially underestimating the number of patients and proportions of providers’ patient populations that completed the HPV vaccine series. However, given the ACIP recommendations and very limited uptake at ages 9–10 years,17 we selected the shorter enrollment requirement (2 years at ages 11–12 years-old) to maximize the size of our cohort and increase generalizability. While we did not analogously require providers to continuously serve patients in the health plan for a particular amount of time, the 1,236 providers with ≥10 well-visits among different female patients generally had their first and last observed well-visits spaced a minimum of 365 days apart. This provides some assurance that providers had a reasonable number of opportunities to administer HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccinations.

Third, we had a limited number of provider characteristics (i.e., provider sex, birth year, and medical specialty) to examine in our dataset so other potentially important provider characteristics such as race and ethnicity could not be assessed. However, among the variables we could examine, provider birth decade and medical specialty were defined with sufficient granularity as we had information on provider birth year and up to five specialties, including the primary specialty. Since our dataset provided National Provider Identifiers which can be used to look-up additional information, such as the address of providers’ primary practices, future studies could explore clusters of high and low rates of HPV vaccine by provider network and geographic area. We also had limited ability to assess the association of patient characteristics with HPV vaccination rates because of limited patient-level characteristics in our dataset.

Fourth, unlike the national NCQA HEDIS estimates that collected HPV vaccine exposures by reviewing both administrative claims data and medical charts, our study utilized only claims data. This difference could help explain why our HPV vaccine HEDIS rates were similar, but slightly lower than the published estimates in 2013 and 2014.4 Since the published NCQA estimates also aggregate data from many diverse commercial health plans across the US, the percentages also represent an average; individual health plan estimates would be expected to show some natural variation. For example, when evaluating the 2013 HEDIS measure for HPV vaccine, the CDC found that among 39 commercial health plans analyzed in the Health and Human Services Region 1 (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont), plan performance ranged from 6.9–22.6% (median: 12.7%).18 Our estimate of 11.4% fit well within the reported range, and was similar to CDC’s median estimate.

Finally, since HPV vaccine HEDIS measures have changed since this study was performed,3,4 it is possible that our findings do not reflect current practice patterns. For example, the health plan is undertaking focused efforts to improve vaccination rates including member reminder and education campaigns as well as including vaccinations in its Pay for Performance program. However, as indicated by a draft of the 2030 Healthy People Objectives which includes the goal of increasing HPV vaccination in young adolescents,19 HPV vaccination rates generally remain suboptimal. Moreover, the 2018 President’s Cancer Panel report notes the critical role that providers continue to serve in addressing this public health priority.20 The methods presented in this study could serve as a model for designing a comparative study that uses administrative claims data to evaluate provider performance in more recent years, or uses the new HEDIS measure. Access to recent data is important for rapid and flexible evaluation of evolving conditions.

Conclusion

In a regional health plan, only 5.5% of providers in our sample administered doses that were part of a complete, three-dose HPV vaccine series to at least one-quarter of their 11–12 year-old female patients. Estimation of HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine coverage estimates at the provider-level in administrative claims-only systems requires careful consideration of how to define providers’ eligible patient populations and number of patients in those populations who receive a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series. Ideally, a data source that provides a large and representative sample of providers’ patient populations should be used. The ability to identify higher and lower performing providers in claims data may allow for targeted quality improvement work or intervention studies.

Materials and methods

Data source

We used administrative claims data from a single, regional health insurance payer from January 1, 2008- April 30, 2015. The health insurer has approximately one million health plan members in the New England states.

Patient population

Female adolescents were eligible if they had 1) continuous enrollment in any commercial health plan (e.g., PPO, HMO plans) offered by the regional insurer for two years, beginning on their 11th birthday and lasting through the day before their 13th birthday, and 2) at least one well-visit, defined by either an age appropriate Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code (99383, 99384, 99393, or 99394), or an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code (V20.2 or V70.0) in the outpatient setting as an 11–12 year-old patient. Patients were required to have ≥1 well-visit to help ensure they were actively using their health plan (and not another one if dually enrolled in two plans). Males were excluded because the HEDIS measures prior to 2016 did not include them.

Exposure

Bivalent, quadrivalent, and 9-valent HPV vaccines were identified in the claims data using their corresponding CPT codes, 90649, 90650, and 90651, respectively. Providers were presumed to have administered or overseen the administration of the vaccine if they were designated as the “performing provider” on the vaccine claim in the administrative claims database. To test whether the performing providers represented clinicians (as opposed to facilities), we reviewed a small sample of performing provider identification numbers (IDs) and found that they linked to clinicians.

Provider population, outcomes, and analysis

Providers were identified using their unique health plan ID number and were required to be specialists in pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, family, adolescent, or internal medicine. To prevent misleading findings that could arise from estimating provider coverage rates with excessively small female adolescent patient populations, we required providers to have ≥10 well-visits with different 11–12 year-old female patients during the study period. A provider’s eligible patient population comprised patients who visited the provider for 11–12 year-old well-visits, as determined by the performing provider ID that was linked to the patient well-visit claim in the database. We also counted the number of well-visits associated with the provider ID. Providers received credit for administering a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series if their provider ID was associated with any of the three HPV vaccine doses administered to a single 11–12 year-old patient who completed the vaccine series. For example, if Provider A administered Dose 1, and Provider B administered Dose 2 and Dose 3, both providers would receive credit for administering a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series to one patient. HPV vaccine doses that were not administered as part of a three dose series were not considered. The final provider coverage estimate was expressed as a percentage of girls receiving a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series among those in the provider’s patient population. As a secondary analysis, we also expressed provider coverage estimates as a percentage of well-visits where a dose in a HEDIS-consistent HPV vaccine series was administered. Provider characteristics, including sex, birth year, and primary specialty, were abstracted from the administrative claims database. We used Pearson’s chi-square tests and reported the associated p-values to test whether provider coverage estimates varied independently by sex or age.

Quality control

To help determine whether our methods and database reasonably captured HPV vaccine administrations and the 11–12 year old female patient population, we estimated HEDIS rates for HPV vaccine overall and by study year (excluding 2015 since our data ended in April 2015). We compared our 2013 and 2014 estimates to national published estimates which were first available in 2013 when HPV vaccination became a HEDIS measure.

Human subjects

This study was approved by the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institutional Review Board.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by a grant from the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CPT

Current Procedural Terminology

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification

- ID

identification

- HEDIS

Health Care Effectiveness and Information Set

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- Std

standard deviation

- Tdap

tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Inna Dashevsky.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Mbaeyi SA, Fredua B, Stokley S. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:909–17. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiter PL, Gerend MA, Gilkey MB, Perkins RB, Saslow D, Stokley S, Tiro JA, Zimet GD, Brewer NT.. Advancing human papillomavirus vaccine delivery: 12 priority research gaps. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:S14–s6. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Committee for Quality Assurance Immunizations for adolescents; 2018. [Accessed 2018 October 2]. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/immunizations-for-adolescents/.

- 4.State of Health Care Quality: HPV 2016. [Accessed 2016 November 1] http://www.ncqa.org/report-cards/health-plans/state-of-health-care-quality/2015-table-of-contents/hpv#sthash.5eEZIZqs.dpuf.

- 5.Meites E, Kempe A, LE M. Use of a 2-Dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination - updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1405–08. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC recommends only two HPV shots for younger adolescents. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Press release; 2016. [Accessed 2018 December 21] https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p1020-HPV-shots.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Healthy People 2020: immunization and infectious diseases; 2018. [Accessed 2018 October 2] https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives.

- 8.Donahue KL, Hendrix KS, Sturm LA, Zimet GD. Human Papillomavirus vaccine initiation among 9-13-year-olds in the United States. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:892–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorell C, Yankey D, Kennedy A, Stokley S. Factors that influence parental vaccination decisions for adolescents, 13 to 17 years old: national immunization survey-teen, 2010. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013;52:162–70. doi: 10.1177/0009922812468208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allison MA, Hurley LP, Markowitz L, Crane LA, Brtnikova M, Beaty BL, Snow M, Cory J, Stokley S, Roark J, et al. Primary care physicians’ perspectives about HPV vaccine. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20152488. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McRee AL, Gilkey MB, Dempsey AF. HPV vaccine hesitancy: findings from a statewide survey of healthcare providers. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(6):541–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilkey MB, Moss JL, Coyne-Beasley T, Hall ME, Shah PD, Brewer NT. Physician communication about adolescent vacination: how is human papillomavirus vaccine different? Prev Med. 2015;77:181–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.All-Payer Claims Database 2018. [Accessed 2018 October 2] https://www.apcdcouncil.org/.

- 14.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among U.S. adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76–82. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stubbs BW, Panozzo CA, Moss JL, Reiter PL, Whitesell DH, Brewer NT. Evaluation of an intervention providing HPV vaccine in schools. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(1):92–102. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brewer NT, Chung JK, Baker HM, Rothholz MC, Smith JS. Pharmacist authority to provide HPV vaccine: novel partners in cervical cancer prevention. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:S3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong CA, Berkowitz Z, Dorell CG, Anhang Price R, Lee J, Saraiya M. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among 9- to 17-year-old girls: national health interview survey, 2008. Cancer. 2011;117:5612–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng J, Ye F, Roth L, Sobel K, Byron S, Barton M, Lindley M, Stokley S. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among female adolescents in managed care plans- United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1185–89. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6442a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Healthy People 2030: immunization and infectious diseases; 2018. [Accessed 2018 October 2] https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People/Development-Healthy-People-2030.

- 20.President’s Cancer Panel HPV vaccination for cancer prevention: progress, opportunities, and a renewed call to action, 2018 [Accessed 2018. December 21] https://prescancerpanel.cancer.gov/report/hpvupdate/Goal2.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- National Committee for Quality Assurance Immunizations for adolescents; 2018. [Accessed 2018 October 2]. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/immunizations-for-adolescents/.