ABSTRACT

Human papillomavirus is among the most common sexually transmitted infections in the world. Newcomers, defined in Canada as foreign-born individuals who are either immigrants or refugees, but may also include students and undocumented migrants, face numerous barriers to HPV vaccination. This study sought to understand, from the perspective of healthcare providers, barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination, and recommendations to improve HPV vaccine uptake among newcomers. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 healthcare providers between March and April 2018. Data were analyzed at the manifest level using a Qualitative Content Analysis approach. Categories of barriers to vaccination included: access, communication, knowledge, culture, and provider-related factors. Facilitators included targeted health promotion; understanding the relevance of HPV vaccination; trusting the healthcare system; and cultural sensitivity. Two overarching recommendations were to publicly fund the HPV vaccine, and enhance language- and culturally-appropriate health promotion activities. Further research should explore informational desires and needs from the perspective of newcomers to inform strategies to promote equitable HPV vaccine coverage.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, HPV, immunization, vaccination, newcomers, healthcare providers, qualitative methods

Introduction

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is among the most common sexually transmitted infections worldwide,1 with over 70% of sexually active Canadians contracting the virus at some point in their lives.2 Vaccination has emerged as an effective primary prevention strategy to protect against the strains of HPV that most commonly cause these diseases.1

The HPV vaccine was first approved in Canada in 2006, and there are currently three vaccines authorized for use.3 Since 2010, the HPV vaccine has been offered to girls in every Canadian jurisdiction through publicly-funded, school-based programs. Additionally, given the increasing body of evidence highlighting the effectiveness of administering the HPV vaccine in males to prevent associated cancers and genital warts,4 all provinces and territories now offer the HPV vaccine for males as part of their routine immunization schedules as well.5 Some provinces also offer publicly-funded vaccine catch-up programs (programs that offer immunization to individuals who are not up-to-date with recommended vaccinations) for individuals at high risk of infection.6 For those who are ineligible to receive it within publicly-funded programs and do not have private health insurance, the full HPV vaccine series costs approximately 540 Canadian dollars.7

Despite its widespread availability, uptake of HPV vaccination across the country remains suboptimal.8 A recent meta-analysis found average uptake of the HPV vaccine across 12 studies to be 56% (range: 12.40%-88.20%).8 This falls short of the national HPV immunization target of > 80%.9 In addition, not only is uptake of the HPV vaccine comparatively lower than other childhood vaccines, coverage and knowledge disparities have been extensively documented among certain demographics and subpopulations. Racial and ethnic minorities are less likely than members of the general population to receive a recommendation from a healthcare provider to initiate the HPV vaccine series.10,11 However, many studies have explored these disparities as they relate to race, rather than immigrant status or culture. This distinction is important, as immigrants and refugees can face a number of challenges related to resettlement in a new country, including issues related to healthcare access and language barriers.

Previous research on HPV vaccination among newcomers (generally defined in the Canadian context as foreign-born individuals, usually immigrants or refugees, but may also include students and undocumented migrants) indicates that newcomers may be under-immunized compared to the general population and often face barriers to uptake. In Denmark, Schrieber12 found that even when the vaccine was publicly-funded, immigrant girls had 51% lower odds of initiating the HPV vaccine series compared to Danish-born girls. Similar results were found among young girls in a Swedish catch-up vaccination program, whereby girls with a non-European background had 78% lower odds of receiving the HPV vaccine than those with a European background.13 These findings are corroborated by data from the United States, where individuals are less likely to initiate and complete HPV vaccination if they are foreign-born.14

A systematic review of barriers to vaccine uptake among newcomers15 reported that several barriers were unique to HPV vaccination. These included a lack of knowledge and awareness about HPV, its transmission and link to urogenital and oropharyngeal cancers, and the availability of a vaccine to protect against it; cultural and religious taboos that hinder conversations about sexually transmitted diseases; concerns that the vaccine promotes promiscuity; and lack of a healthcare provider recommendation.15 Such barriers have also been reported in the Canadian context, where, among a female immigrant and refugee vaccine catch-up group, lack of knowledge was found to be the main barrier to vaccine series initiation, with most participants never receiving a healthcare provider recommendation.16 This is especially concerning given that immigrant and refugee women, who may not have attended cervical cancer screening in their country of origin and are less likely to attend pap smear screenings in Canada, are at a higher risk of developing cervical cancer.17

Healthcare provider recommendation is one of the strongest predictors of HPV vaccine uptake. Gilkey10 found that a high-quality recommendation that strongly endorsed the vaccine, encouraged same-day vaccination, and discussed cancer prevention increased the odds of vaccine initiation by a factor of nine compared to no recommendation. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that newcomers may be more accepting of vaccination overall than the general population.18 Thus, healthcare providers are well-positioned to discuss and encourage uptake of the HPV vaccine among newcomers. Given their unique perspectives and insight, this study sought to explore the experiences and perceptions of healthcare providers who administer the HPV vaccine to newcomers in Ottawa, Ontario.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 10 healthcare providers were interviewed. Five worked within the public health system, four in primary care settings (two family physicians and two nurse practitioners at community health centres), and one was a gynecologist working in the hospital setting. Demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| Participants, n(%) | |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 10 (100%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 8 (80%) |

| Male | 2 (20%) |

| Age range (years) | |

| 18–25 | 1 (10%) |

| 26–35 | 2 (20%) |

| 36–45 | 5 (50%) |

| 46–55 | 0 (0%) |

| 56+ | 2 (20%) |

| Area of service provision | |

| Public health | 5 (50%) |

| Primary care | 4 (40%) |

| Hospital care | 1 (10%) |

| Length of time in role (years) | |

| 0–5 | 1 (10%) |

| 6–10 | 3 (30%) |

| 11–15 | 2 (20%) |

| 16–20 | 3 (30%) |

| 21+ | 1 (10%) |

| Identify as a newcomer | |

| Yes | 1 (10%) |

| No | 8 (80%) |

| Second generation | 1 (10%) |

Providers working within the school-based program held bi-annual vaccine clinics in schools across Ottawa and interacted mostly with students (in some cases phoning parents to obtain consent to vaccinate). Some providers had experience in “higher needs” schools, a term used to describe those with low vaccine uptake and a high number of newcomers. They also worked in catch-up clinics for children and adults who were missing publicly-funded vaccines and conducted surveillance to ensure students were up-to-date with vaccines required to attend school. Of the four primary healthcare providers, two were family physicians. The other two were nurse practitioners at community health centres that have a mandate to see refugees without health insurance. Approximately 70% of the gynecologist’s patients were seen for cervical pre-cancers and genital warts, which included HPV counselling (including information about HPV vaccination) in every visit; the majority of patients were over the age of 21.

Providers’ perceptions of HPV vaccine uptake among newcomers were variable, with some providers feeling that coverage among newcomers was comparable to the general population, and others feeling that newcomers were more likely to reject the vaccine. Participants were invited to provide their own definitions of who they believed would be considered “newcomers”. When asked, some providers defined a newcomer as someone born outside of and new to Canada, but one provider noted that a newcomer could also be someone who has lived in Canada for a longer period of time but did not integrate into Canadian culture.

Data were analyzed to elucidate barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination and recommendations to improve vaccine uptake among newcomers from the perspective of healthcare providers. Categories and sub-categories were identified for both barriers and facilitators, and there were two overarching recommendations. An overview of the findings can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Health care provider perspectives on barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination.

| Categories | Themes | Supplementary Sample Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Access Barriers | • Cost • Navigating a new healthcare system |

“Then furthermore, they can’t afford paying for it. Most of my newcomers are unable to pay for it regardless of any of their cultural background. To be very honest, often I look at their social issues, and I just skip over HPV because I don’t want to also make them feel bad that there’s a vaccine that I can’t actually provide to them.” (HCP10) “So they maybe come here and they’re told that they need to start getting re-immunized, right. But, so, that’s good and all, and they may get their first set of vaccines from the community health centres that they’re directed to immediately upon coming to Canada, but they don’t know that they still need to be immunized further. So it’s like, they have the barrier of ok, well we don’t have a family doctor, we don’t know where to go to get our vaccines.” (HCP4) |

| Communication Barriers | • Not having a common language • Inappropriate information resources • Implications of communication barriers: • Difficulty obtaining informed consent |

“… and when there’s language barriers, we can’t go into the details of anything. So it’s just a very brief intervention, letting them know that it’s there.” (HCP4) “But, because that’s where we’re offering the vaccine, and parents who want their child to get it, some of them actually do show up to the clinic, you know like, “I don’t understand”. And that’s an opportunity, but it’s also difficult that they had to come all the way in, do that just to – something’s not clear, right.” (HCP3) “So we’re not really bringing up this subject, we don’t really get the opportunity to encounter the parents face-to-face at all, it’s always over the phone, and it’s always gonna be like, as little information as possible, over the shortest amount of time possible, and to gain consent, like to get consent. So it’s not like the best opportunity to go into it.” (HCP3) |

| Knowledge barriers | • Limited knowledge and awareness of HPV and HPV vaccination | “In my experience, many of my female patients never had a pap smear. It may be that other techniques were used, like acetic acid staining to screen for cervical cancer, but they certainly weren’t aware of cervical cancer screening, the ones I’ve talked to.” (HCP5) |

| Cultural barriers | • Talking about sexuality is taboo • Religious beliefs around sex before marriage |

“I find the HPV is kind of a tricky one, ‘cause when you start explaining what HPV is – you know, being the human papillomavirus, a virus that can be transmitted sexually – that tends to turn off a lot of people. And not just newcomers…” (HCP1) |

| Provider-level barriers | • Healthcare-seeking behaviours • Fewer chances to discuss preventative care • Not receiving a recommendation • There is no time to discuss HPV • Having to administer multiple vaccines at a time, priority setting |

“They don’t come unless they have a cold or cough. Opportunistic approach, when they come just for cold and cough, we know opportunistic approaches are not effective in immunization.” (HCP10) “So if you’re only going one-third of the time that you used to for that cervical screening, the opportunity in the mind of the primary care may not be there.” (HCP8) “Because for most patients who we’ve known since birth, we rely on the school system to give them the Gardasil. We might not be making the link that a newcomer may not have been offered that through the school system.” (HCP5) “I think other barriers are things like, when you look at the catch-up schedule for refugees that are like “unimmunized”, HPV is not really on there. Like they’ve just got more mandatory ones so there’s that. So we’re not thinking about that.” (HCP9) |

| Facilitators: targeted health promotion | • Targeted health promotion | “Well, at one school for example, they provided an information night for parents. We were able to send one of our nurses and one of the school health nurses and they were able to explain about the vaccines, about the questions that they had around HPV, and provide consent forms there, explained the consent form process, and by the end of the night, we had many more consents. I think that if we can do that in every school, that would be ideal.” (HCP6) |

| Understanding the relevance of HPV vaccination | • Getting it for free now or paying for it later • Changing eligibility criteria |

“So I mean, when a mother and daughter, 16, decide not to and they’re Muslim, and they probably won’t be in that situation for a while, there’s no reason, there’s no problem in delaying it. I mean I would just encourage them to, you know, ask about it when they connect to their new health provider. But probably the only piece is the financial piece, right. Because it might be harder for them to get it later on.” (HCP7) |

| Trusting the healthcare system | • Openness to vaccination | “But I find more with new immigrants, they’re very like, ok, that’s fine, we’re good. They trust, like I find they have a high trust towards healthcare, so they’re often very easy to deal with when it comes to these things. And with HPV, as well as the other vaccines, like they have high trust. So they will take the vaccine.” (HCP4) |

| Cultural sensitivity | • Ensuring access to appropriate personnel • Culturally sensitive risk communication |

“And if they understand that it’s not because we think their child is having sex, they’re very open to receiving it.” (HCP4) |

Barriers to HPV vaccine uptake

Access barriers

Cost of HPV vaccination was seen as a major, and in many cases the largest, barrier to HPV vaccine uptake among newcomers. Acknowledging that newcomers often find themselves in poor financial situations upon arrival in Canada, providers were reluctant to recommend initiating a catch-up series, with some feeling uncomfortable recommending a vaccine that they could not provide for free. Conversely, one provider did not see cost as a barrier, and in many cases their newcomer patients were willing to pay for vaccination. In fact, this provider argued that the assumption that newcomers cannot afford the HPV vaccine was a barrier in itself, and believed that newcomers should be provided with all the information to decide regardless of their financial situation:

“And that’s when you ask people that weren’t vaccinated, it’s not because it cost too much. It’s just a huge disconnect between what the provider’s thinking and what the patient actually is feeling. And I think a lot of providers do a disservice to the patient by me looking at you and thinking, “Oh, I don’t think you can afford it, maybe I’m not going to talk about it, I don’t want to make you uncomfortable.” (HCP8)

Healthcare providers working in primary care also highlighted how difficulties accessing primary care and navigating a new health system in general could be a barrier to HPV vaccination among newcomers. This included learning how and where one could receive vaccines in Canada, as well as understanding where and when to receive subsequent doses of the vaccine series. Some providers described how only select clinics will serve refugees without health insurance, and oftentimes the availability of these clinics is unknown to newcomers:

“Another thing is, refugees and newcomers often have the interim federal health, and that makes it – that’s just a barrier in accessing healthcare, like primary healthcare. So like I say, the CHCs [community health centres] can see those people, but if somebody doesn’t know about a CHC or isn’t connected, then they are probably not accessing the same level of primary care.” (HCP9)

Communication barriers

Communication barriers related to language were frequently cited by providers. Encountering newcomers who did not speak English or French severely limited providers’ ability to explain the vaccine in detail, and to ensure comprehension to enable the parent to make an informed vaccination decision. The fact that HPV information resources, such as the informed consent letter and information package sent home with students in the school-based program, as well as online and pamphlet resources about HPV provided in other healthcare settings, are only available in English and French was described as a limiting uptake factor. Additionally, providers noted that despite their best efforts, health promotional resources were not at an appropriate literacy level for newcomers to be able to understand HPV and the purpose of the vaccine:

“The consent forms are convoluted, they’re difficult to understand, you wouldn’t really know, even just as a layperson looking at it, just being ok, where do I sign? And, it’s not in the languages.” (HCP3)

Language barriers often manifested in issues with obtaining signed consent forms. In situations where students did not have signed consent forms, school-based providers described challenges reaching and communicating with newcomer parents to obtain consent to vaccinate. Despite the fact that children can consent to vaccination under the Health Care Consent Act, school-based providers were hesitant to administer the HPV vaccine without parental consent due to the fact that parents sometimes do not want their children to be immunized for cultural or religious reasons (HCP2). When students present without consent forms, efforts are made to contact the student’s parents, but this can be a time-consuming and difficult process. As a result, newcomer students who do not have signed consent forms on the day of school clinics may miss the HPV vaccine in the school-based system:

“We’re so busy in the clinic, we have a high volume of children to do, and we want to finish, we don’t have to come back to the school and bother them over and over, so our goal is to get the children done who have signed consents. And unfortunately, those who don’t have consent forms kind of get a little bit forgotten about. And simply that’s just because there’s just not enough time.” (HCP3)

Knowledge barriers

All providers indicated that newcomer patients typically had very little, if any, previous knowledge about HPV, how it is transmitted, or the fact that there was a vaccine to protect against it. Providers noted that cervical cancer screening and administration of the HPV vaccine does not typically occur in newcomers’ country of origin, further exacerbating knowledge gaps. One participant working primarily with refugees described broader health literacy issues as a barrier to knowledge and understanding, highlighting some newcomers’ very limited past education:

“I have some families that have very limited past education. They might have spent most of their life in a refugee camp. One of my examples is sometimes when I’m doing past family history, I’ll say “do you have any family history of cancer?” And even the interpreter will tell me “they wouldn’t know if – they wouldn’t know cancer” right. So then you have to re-kind of think how you’re going to present the education piece, right.” (HCP7)

Cultural barriers

Providers discussed challenges with initiating discussions related to sexuality and sexual health, noting that this is often a taboo subject among certain cultures in the newcomer community. Despite many newcomers being open to vaccination in general, some reported hesitancy to the HPV vaccine in particular, especially upon learning that HPV is sexually transmitted. Providers recalled interacting with newcomer parents who were reluctant to have their child vaccinated due to beliefs that vaccinating against a sexually transmitted disease may promote promiscuity:

“But people have, you know, explicitly said like, this vaccine promotes sex, and this is not something that we believe. Like that happens all the time.” (HCP3)

Of newcomers who were hesitant to receive or rejected the vaccine, providers cited religious views as a factor that may impact vaccine uptake. In particular, the practice of remaining abstinent before marriage was recalled as a common sentiment among newcomers that hindered uptake among newcomers. Providers described how this led to a lack of perceived risk of contracting HPV if patients expected to be sexually active with only one partner over a lifetime, a belief described as particularly common among Muslim patients. Providers noted that hesitation or rejection of the HPV vaccine often boiled down to religion, as opposed to culture or country of origin, as they had observed similar challenges in non-newcomer Catholic and Jewish populations:

“Most of my Muslim patients would be very against the idea of giving a vaccine to their children who are not sexually active. From their understanding, [they] will only become sexually active with one person eventually. Who also will be a virgin, right? That’s their perception, and I’m not saying all of them, but certainly most of my more religious patients would feel that. It’s more of their kind of Islamic belief rather than where they come from, right?” (HCP10)

Provider-level barriers

Many of the barriers providers described stemmed from providers themselves lacking the time or opportunity to engage with newcomer patients around the HPV vaccine. This was due in part to patients’ tendency to seek care for acute issues rather than preventive care and updated guidelines around cervical cancer screening that manifested in fewer opportunities for engagement around prevention. One provider corroborated this, noting that despite their documented importance, few patients reported receiving a recommendation for the HPV vaccine:

“But of all those people I’ve seen for HPV-related stuff, at least 70 percent of them have not had vaccination discussed before the first visit. It’s a really high number.” (HCP8)

Providers emphasized that when they do have an opportunity to engage with newcomer patients, there are so many competing issues to discuss with patients within a limited window that HPV vaccination may not be a priority:

“So there’s a couple of things, I think always time is a factor, so there are so many millions of things that a primary care provider is trying to cover. So I think not having time to discuss is number one.” (HCP8)

Additionally, one provider noted that providers may not realize vaccination should be a priority, as providers tend to rely on school-based programs to administer the vaccine. When vaccination is discussed with patients, some providers felt that HPV is not a priority in Ontario’s official catch-up immunization schedule, while others felt that HPV vaccination could be discussed at another appointment since patients already received multiple vaccines at once. A common practice among providers was to ensure that first and foremost, newcomers were up to date with the vaccines required to attend school. Therefore, HPV vaccine uptake may be suboptimal due to the prioritization of mandatory vaccines and because it could be perceived as optional:

“Usually on their first appointment we really focus on what vaccines are mandatory, cause oftentimes, they need 3, sometimes 4 vaccines at one time.” (HCP1)

Facilitators to HPV vaccine uptake

Targeted health promotion

Providers pointed out that in cases where they were able to overcome communication barriers and educate newcomers about HPV, patients were very accepting of the vaccine. Providers working within the public health system recalled higher success in convincing newcomers to accept the vaccine in catch-up clinics, where they were able to have a face-to-face dialogue with parents and children:

“Depending on how much they understand, we might be able to…and I do feel like a lot of times, if it’s properly explained or if the parent does understand, they’re all for it.” (HCP3)

Understanding the relevance of HPV vaccination

Changes to the school-based program were also perceived to be a step in the right direction to improve uptake. For example, providers mentioned that the recent decision to include boys in the school-based program would likely de-stigmatize the vaccine and lead to greater acceptance overall. Furthermore, some providers believed that lowering the age of vaccination against HPV and administering it at the same time as other vaccines would put it into the context of health, as opposed to sexuality:

“For many other provinces, at grades four to grade six, would make the parent think of it in the context of a vaccine for health for their child, just like other vaccines are.” (HCP8)

Trusting the healthcare system

Providers noted that newcomers displayed a great sense of openness to vaccination in general, perhaps even more so than non-newcomers. They perceived this to be partly because many newcomers have seen the health implications that can arise when people are not vaccinated in their country of origin, but also because in their experience, newcomers were very trusting of the healthcare system and providers generally. From their perspective, the value that newcomers place on a healthcare provider’s recommendation was a considerable facilitator to HPV vaccine uptake:

“I think newcomers in general are open to vaccination. I don’t, I haven’t met an anti-vaxxer in the newcomer [population], because I mean they lived in situations where it was important to be vaccinated, because they lived in very close – not all, but people that came from camps did, right.” (HCP7)

Cultural sensitivity

Providers discussed the importance of being culturally sensitive when providing care for newcomers. They emphasized the importance of culturally sensitive risk communication and emphasizing cancer prevention to take the focus away from the vaccine’s association with sexuality. They also highlighted providing access to female healthcare providers for female patients and having interpretation services readily available:

“We did have for a brief period, we had one public health nurse who was Arabic speaking, and so when the Syrian refugees came in and we had to immunize them with, just their basic, so their measles, mumps, rubella and those vaccines – like it was great right, ‘cause once you cross that language barrier, you’re good. Like they can understand, they can consent, they can follow through.” (HCP4)

Recommendations to improve uptake

Providers suggested six major recommendations that could improve HPV vaccine uptake among newcomers, which are summarized in Table 3. There were two overarching recommendations related to access and communication that were heavily emphasized by providers.

Table 3.

Recommendations from health care providers to improve HPV vaccine uptake among newcomers.

| Sample Quotes | |

|---|---|

| Recommendation 1: Publicly fund the HPV vaccine | “But if we could at least say that it would be offered to anyone, not just this vaccine, but other vaccines too would be offered, like if you have Hepatitis B, the same thing, that it would be offered to you, same as it’s offered in the school based program to all those kids, the same basic minimums would be offered upon entry, because that population is at much higher risk even than the people that already live here, ‘cause they haven’t had adequate screenings.” (HCP8) |

| Recommendation 2: Enhance language and culturally appropriate health promotion activities |

“And if there was a little bit more, like, education in the school. Not necessarily by the school staff, but just like, even with a public health – we’re very stretched like, we have a lot of things we do in a year…but they’re just like the school health nurses that go in the schools. They currently do some of that like teaching and promotion, but I just find there could always be more.” (HCP4) “I would just think about language specific promotion, you know. Just about is there a role for public health messaging. I haven’t seen anything targeted to HPV that’s language specific” (HCP5) |

| Recommendation 3: Provide explicit catch-up opportunities in the school-based program | “Yeah, I would say it has to come from kind of the school environment because adolescents don’t come to see their family doctor, right? They come just for the 14 through 16 visit for their Adacel shot and the meningitis. That’s where I usually get them, but that’s the only opportunity I have. They don’t come unless they have a cold or cough. Opportunistic approach, when they come just for cold and cough, we know opportunistic approaches are not effective in immunization.” (HCP10) |

| Recommendation 4: Create a vaccine databank | “I would love to see like a national vaccination databank that all of us were inputting our vaccines to and were able to pull from and be able to look up. So I could see that that person from BC has had all of these vaccines, and then I could just give them the rest. Because right now, it’s so scattershot that everybody – there’s a lot of people getting extra vaccines they don’t need, and there’s people that fall behind because we’re just assuming that they’re updated and their not. So I’d love to see like a national, at least a provincial level one, at least a city level one. But right now it’s just not in place.” (HCP9) |

| Recommendation 5: Have the HPV vaccine on hand at primary care clinics | “I mean I would love to see [public health] just sending us the HPV vaccine the same way they send the tetanus vaccines, and we just have like 20 of them sitting in the fridge and I just give them to whoever I think is in the right age category” (HCP9) |

| Recommendation 6: Create reminder systems for HPV vaccine recommendation | “With electronic charting now being the norm, there are easy ways for you and the provider, or even the electronic chart company, to pop in a little flag that pops up saying, “Did you talk about all of the vaccination?” And it automatically looks at the age of the patient and then says this, and this, and this, and this. So there’s certainly ways, if you think about it, to change your practice” (HCP8) |

Publicly fund the HPV vaccine

Providers emphasized the need to publicly fund the HPV vaccine for everyone for whom it is recommended. This was especially pertinent to newcomers, as cervical cancer screening and vaccination against HPV often does not exist in their country of origin, thus putting them at an increased risk for HPV-related diseases. This recommendation was substantiated by the fact that pap smears are publicly-funded procedures to prevent cervical cancer, while vaccination is not. Therefore, providers urged the idea of vaccinating based on risk rather than age so that newcomers are not left behind in cervical cancer prevention:

“If it was covered, I would bring it up in every [women’s health check-up]. Every [women’s health check-up], HPV…I mean we’re doing pap tests, we should be doing HPV vaccine. Like, it doesn’t even make sense that we’re not doing it.” (HCP7)

Enhance language and culturally appropriate health promotion activities

Healthcare providers highlighted a need to create informational resources and opportunities tailored to the language and cultural needs of newcomers. This was guided by the belief that with the proper tools to educate newcomers on the vaccine and its purpose, this information could overcome personal barriers to HPV vaccination. In addition to translated resources, one provider mentioned the importance of outreach to populations not currently accessing primary care:

“What if we had big banners or, nowadays everybody gets advertisements through their cellphones. If we had these culturally appropriate and in different languages, had these ads to bring it to… to reach those who we can’t reach. The ones who are parked in front of their TV watching TV programs in their own language, right?” (HCP10)

Comparison to newcomer’s views

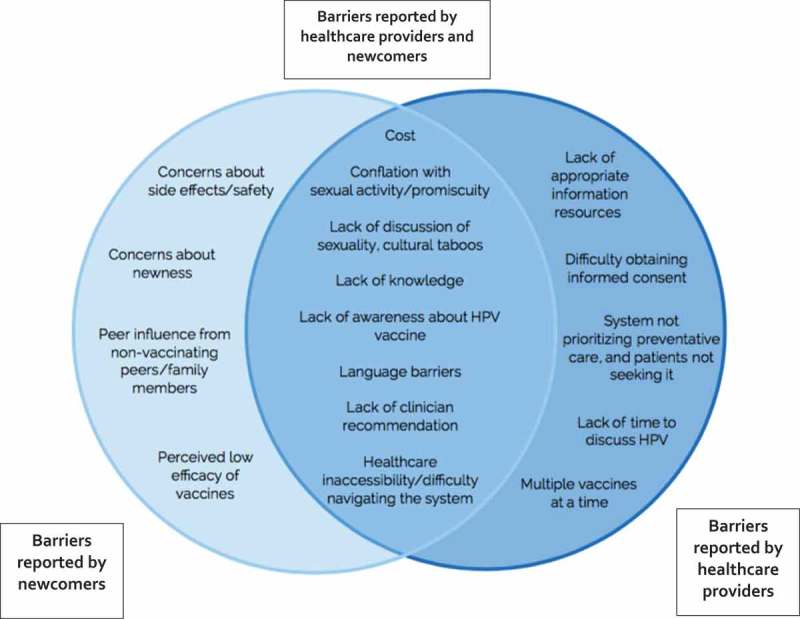

We compared the perspectives of healthcare providers from our study to those of newcomers from our previously published systematic review of qualitative studies. Several barriers that were identified in this study were not mentioned as factors in vaccine decision-making by newcomers themselves. In particular, the healthcare providers in our study described issues that arose as a result of the HPV vaccine being recommended rather than required. When time is limited and multiple vaccines need to be administered to a patient, healthcare providers prioritize certain vaccines, and those that are not required (i.e., HPV) tend not to be prioritized. This issue is exacerbated by another barrier uniquely identified by healthcare providers: the absence of opportunities to discuss the HPV vaccine in the context of preventive care due to the reduced frequency of recommended HPV screening tests. In combination with the fact that some newcomers themselves report not seeking preventive healthcare,19 these limited contacts between patients and providers may manifest in the barrier referred to by both newcomers and healthcare providers, wherein an explicit recommendation for the vaccine is not often given.

Healthcare providers also spoke about knowledge barriers manifesting in different ways from those described by newcomers themselves. Providers noted that where information about HPV vaccination is available, it is not communicated appropriately to meet the informational needs of newcomers. Similarly, the current process for obtaining consent from parents of students being vaccinated in the school-based system was described as overly time-consuming and difficult for newcomers to understand. Providers commented that current methods of dissemination do not effectively engage newcomers, as they are not delivered at the right language or literacy level. This builds on the perspective offered by newcomers, who reported a total absence of information and further indicates a need for more engaging and appropriate informational materials.

A summary of the similarities and differences between the results identified in the systematic review versus those found in this study can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of barriers to HPV vaccination reported by newcomers vs. healthcare providers.

Discussion

This study sought to elucidate barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination, as well as recommendations to improve vaccine uptake among newcomers to Canada from the perspective of healthcare providers. The findings indicate that HPV vaccine uptake may be influenced by interrelated factors at the patient, provider, and system levels. These include issues related to access to and delivery of healthcare, communication at both the patient-provider and health promotion level, as well as personal factors related to religion, culture, and knowledge. Providers emphasized publicly-funded HPV vaccination for all and improving avenues for communication as major recommendations to improve HPV vaccine uptake.

Several barriers identified in this study corroborate existing research on the topic.15,20 Barriers related to cost, lack of knowledge, clinician recommendation, language, healthcare inaccessibility, and conflation of the HPV vaccine with sexual activity were reported both by newcomers in our previously published systematic review15 and by the providers in this study. However, the results of our study also indicated that several perceived barriers were unique to newcomers or healthcare providers and did not appear across populations.

In particular, barriers associated with vaccine hesitancy (e.g., concerns about side effects, efficacy, and the relative newness of the vaccine) were identified as important obstacles for newcomers in our systematic review,15 but these issues were not mentioned by healthcare providers in this study. This could be due to different barriers existing in the populations sampled in the systematic review or a lack of awareness of these barriers amongst health professionals. It is also possible that over time, concerns about the newness of the HPV vaccine may fade, resulting in fewer worries about vaccine risks and safety.

By contrast, barriers that were uniquely identified by healthcare providers tended to refer to system-level barriers rather than the more individual-level barriers reported by newcomers. These perceived system-level shortcomings highlighted healthcare providers’ unique contribution in recognizing gaps in immunization programming. These gaps primarily referred to a lack of time and resources dedicated to promoting vaccine uptake. As both this study and our previously published systematic review indicated unique hesitancy around the HPV vaccine given its association with sexual health, providers highlighted the importance of ensuring patients have a thorough understanding of the importance of the HPV vaccine. This understanding requires the dedication of time and resources that are currently unavailable to providers, who face multiple competing priorities.

Implications for policy and practice

Exploring the results of this study through the domains proposed by Lomas21 allows us to better explain why HPV vaccination uptake may be suboptimal among newcomers and suggest implications for policy and practice. Information about HPV and HPV vaccination exists, and the results suggest that newcomers would be accepting of this information. Where immunization programming for newcomers could be improved is at the structural and institutional levels, where there is a perception of ambiguity about roles and responsibilities related to vaccinating newcomers. There also appears to be a disconnect between information purveyors and newcomer beliefs about HPV vaccination. Our findings suggest that information about HPV vaccination may not be conveyed in a way that meets the needs of newcomers and is therefore a key opportunity for intervention. Carnegie22 indicates that the school-based setting is likely to be an effective opportunity to provide language-appropriate education when developing cross-cultural HPV vaccine programming, but methods of disseminating information must also take into consideration populations that are difficult to reach. This requires varied and novel solutions. Digital technology has been proposed as a potentially promising way of improving vaccine uptake and on-time vaccination by overcoming many of the barriers identified in this study, including the ability to track vaccination records when visiting multiple providers and provide reliable immunization information.23,24 According to a needs assessment survey among newcomers in Ottawa, over three-quarters of participants indicated they would use mobile technology to track their vaccinations if it were available in their primary language.25 Given the near ubiquity of smartphones, leveraging digital technology may be a way forward in effectively disseminating vaccine information.

Furthermore, cost was identified by providers as a severe limitation to HPV vaccine uptake, especially given the financial situation of many newcomers. This influenced their decision to recommend the vaccine in the majority of cases. Previous literature has also reported a reluctance to recommend the vaccine among healthcare providers if it was perceived to be a financial burden on their patients.26,27 Given the demonstrated importance of provider recommendation, documented as both a barrier to HPV vaccine uptake if it is lacking and a facilitator if it is present, addressing this factor at the institutional level is another critical area for intervention.

In terms of addressing religious barriers to vaccination, it is likely that little can be done to influence these deep-rooted beliefs from an intervention perspective. A systematic review of interventions aimed at overcoming vaccine hesitant ideologies indicated limited success in influencing vaccination behaviour, illustrating the difficulties associated with changing these beliefs.28 However, providers can continue to demonstrate a commitment to culturally-sensitive care.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several important strengths and limitations. We did not pre-define what constituted a newcomer during the data collection process. Instead, we allowed providers to define this based on their individual experiences and perceptions. Recognizing that this term may have different meanings for different people, as well as the substantial heterogeneity among newcomers to Canada, these findings cannot be generalized to all newcomers. In addition, despite efforts to focus on newcomers specifically during data collection and in the analysis, providers also worked with non-newcomers; therefore, some of the findings may not be wholly unique to this population. Lastly, despite the fact that we ensured saturation in our results before concluding recruitment and data collection, our sample size of 10 healthcare providers is small, limiting the strength of our conclusions.

There are a number of strengths that should be highlighted. Our study provides unique insights into barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccine uptake among newcomers from the perspective of healthcare providers and helps to fill an important knowledge gap. This approach provides insight at patient, provider, and system levels, promoting a more comprehensive understanding of this issue and informing a holistic approach for intervention. Furthermore, the diversity of the healthcare providers interviewed is an important strength that allowed us to capture a wide variety of perspectives. Engaging participants who worked in public health, primary care, and hospital-based settings, as well as those who administer the vaccine in the school-based program and others who provide catch-up vaccinations, yielded a complex picture of potential barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination among newcomers when cost was a factor to consider and at varying levels of access. Comparing our findings with those of newcomers is a unique approach and provides a more complete sense of the complexity of the decision-making process.

The findings from this study show that from the perspective of healthcare providers, newcomers to Canada may face a number of barriers to HPV vaccination that are governed largely by a lack of access to quality healthcare. Creating language and culturally-appropriate information resources that promote knowledge and understanding of HPV vaccination will be fundamental in developing targeted interventions to increase uptake among newcomers. Making the HPV vaccine free-of-charge is likely to enhance healthcare provider recommendation which may improve uptake. Further research should explore informational needs from the perspective of newcomers to inform strategies to promote equitable HPV vaccine coverage.

Methods

Study design

This study explored factors influencing access to and decision-making around HPV vaccination among newcomers from the perspective of healthcare providers. The study design was guided by the following research questions:

What are healthcare provider perspectives on barriers to HPV vaccination among newcomers?

What are healthcare provider perspectives on facilitators to HPV vaccination among newcomers?

What are recommendations to improve HPV vaccine uptake among newcomers from the perspective of healthcare providers?

What are the similarities and differences between these perspectives and those of newcomers themselves?

We used a qualitative approach as it allowed us to gain a detailed picture of a complex issue, and understand the processes involved in the interactive nature of vaccine decision-making within a particular context.29 Further research is being conducted with newcomers themselves and will be used to supplement this work.

Study setting

This study took place in Ottawa, Ontario, the fourth largest and capital city of Canada. The Ottawa-Gatineau region has the sixth-highest number of foreign-born people in Canada and nearly 20% of the population are landed immigrants.30

In the province of Ontario, the HPV vaccine is offered in publicly-funded, school-based vaccination programs through local public health units to all students in grade seven. Boys have been included in this program since the 2017/18 school year. While girls can receive the vaccine series for free until their last year of high school, boys are only publicly-funded in grade seven. Ontario is one of two provinces that implements a Mandated Choice at school entry policy, whereby parents must show proof of certain immunizations to register for school or obtain a valid exemption. Failure to do so could result in school suspension. Of the three vaccines offered in grade seven (meningococcal C, hepatitis B and HPV), meningococcal C is the only one that is required under this policy. Public health nurses are responsible for leading these clinics, undertaking such tasks as collecting informed consent letters and administering the vaccines. Besides the school-based program, the HPV vaccine can also be delivered at catch-up clinics led by public health units or in primary care settings by nurse practitioners and family physicians.

Participant sampling

A purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit participants who could contribute rich insight related to the study aims. To be eligible, healthcare providers needed to have experience discussing and administering the HPV vaccine with newcomer youth and/or parents. A maximum variation sample of providers working in both primary care and school-based settings was sought to capture different perspectives. This allowed for the exploration of barriers, facilitators, and recommendations for uptake both when factors related to cost and access were present and when they were absent.

Identifying appropriate participants was facilitated by a network of gatekeepers working in vaccination-related roles in Ottawa and Ontario. Initial recruitment was aided by a nurse practitioner at a community health centre specializing in newcomer care. To recruit participants working in the school-based setting, a gatekeeper within the local public health unit identified nurses with experience administering the HPV vaccine in schools with a high volume of newcomers, as well as at catch-up clinics providing publicly-funded childhood and adolescent immunizations. Potential interviewees were reached via e-mail with a brief description of the study and the participant information and consent form attached. All participants who were contacted using this strategy agreed to participate in the study. Participants were not compensated for participating in the interview as the interviews were considered relevant to participants’ work and occurred during periods for which they were already being paid. Participants were informed that they would not receive any direct benefit for participating, but indicated their willingness to contribute in order to advance the knowledge around the subject of HPV vaccination among newcomers.

Data collection

Semi-structured, one-on-one interviews were conducted between March and April 2018. Interviews occurred either in-person or over the phone, according to the participant’s preference. In total, seven interviews were conducted in-person at various locations around Ottawa, including at public health unit offices and at community health centres, while three interviews were conducted over the phone. All interviews were audio-recorded and lasted between 26 and 68 minutes.

Prior to the commencement of this study, the research team carried out a systematic review examining barriers to immunization among newcomers.15 An interview guide was developed based on dominant themes related to HPV vaccination that emerged from this review (Supplementary Materials). Providers were asked to focus on their personal experiences of interacting with newcomers, as well as to reflect on strategies to improve HPV vaccine uptake in this population. Due to the iterative nature of qualitative research, questions that did not elicit rich responses or address the research question were removed and new questions were added based on new insights.31 At the conclusion of the interview, the researcher collected basic demographic information.

Interviews were conducted until saturation was achieved.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using a Qualitative Content Analysis approach as described by Graneheim and Lundman.32 The analysis focused on manifest content, which “describes the visible, obvious components of a text” in order to stay as close as possible to the participants’ original accounts.32 Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Codes were developed inductively as themes and concepts were identified, and then sorted into sub-categories and categories based on their similarities and differences. This process was facilitated using the computer software NVivo (NVivo qualitative data analysis Software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11, 2016). Triangulation strategies were applied whereby the final categories and sub-categories were discussed and agreed upon with another member of the research team.

Theoretical framework

In order to translate the findings of this research into action, we opted to consider the results in relation to a policy- and decision-making framework, specifically that proposed by Lomas21 as an adaptation of Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework.33 This model consists of three interrelated domains that describe contextual influences on policy development.

Comparison to newcomer’s perspectives

To determine how perspectives on HPV vaccine uptake varied between newcomers and healthcare providers working with newcomers, we compared the findings from this study to those from our previously published systematic review of barriers to vaccine uptake in newcomers.15 Specifically, we considered which themes were unique to newcomers or providers and which themes were relevant across groups.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (OHSN-REB #20170913-01H).

Written informed consent was obtained prior to the interview. Verbal consent was also obtained prior to the commencement of the interview. To ensure privacy and confidentiality, transcripts and data were de-identified, and pseudonyms were assigned to each participant. Additionally, clinic locations and names were de-identified upon transcription.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research under grant [HPV-155394].

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer [Internet]. 2018. [accessed 2018 April 10].http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer

- 2.Public Health Agency of Canada Human Papillomavirus (HPV) [Internet]. 2017; 2018 https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/sexual-health-sexually-transmitted-infections/human-papillomavirus-hpv.html

- 3.Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics Canadian cancer statistics special topic: HPV-associated cancers. Toronto (Canada): Canadian Cancer Society; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillman RJ, Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, Moreira ED, Vardas E, Aranda C, Jessen H, Ferris DG, Coutlee F, et al. Immunogenicity of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus (type 6/11/16/18) vaccine in males 16 to 26 years old. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:261–267. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05208-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health Agency of Canada Canada’s Provincial and territorial routine (and catch-up) Vaccination routine schedule programs for infants and children - Canada.ca [Internet]. 2018. [accessed 2018 September 18]; https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/provincial-territorial-immunization-information/provincial-territorial-routine-vaccination-programs-infants-children.html

- 6.Shapiro GK, Perez S, Rosberger Z.. Including males in Canadian human papillomavirus vaccination programs: a policy analysis. Cmaj [Internet] 2016;188:881–886. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27114488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Cancer Society HPV Vaccines [Internet]. 2018. [accessed 2018 September 18]; http://convio.cancer.ca/site/PageServer?pagename=SSL_ON_TM_CervicalCancer_Vaccine

- 8.Bird Y, Obidiya O, Mahmood R, Nwankwo C, Moraros J. Human Papillomavirus vaccination uptake in Canada: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Prev Med [Internet] 2017;8:71 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28983400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Public Health Agency of Canada Vaccine coverage in Canadian children: results from the 2013 Childhood National Immunization Coverage Survey (CNICS). Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine Internet 2016;34:1187–1192. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26812078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeudin P, Liveright E, Del Carmen MG, Perkins RB. Race, ethnicity, and income factors impacting human papillomavirus vaccination rates. Clin Ther Internet 2014;36:24–37. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24417783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slattelid Schreiber SM, Juul KE, Dehlendorff C, Kjaer SK. Socioeconomic predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among girls in the Danish childhood immunization program. J Adolesc Health Internet 2015;56:402–407. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=25659994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandahl M, Larsson M, Dalianis T, Stenhammar C, Tyden T, Westerling R, Neveus T. Catch-up HPV vaccination status of adolescents in relation to socioeconomic factors, individual beliefs and sexual behaviour. PLoS One Internet 2017;12:e0187193 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29099839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adjei Boakye E, Lew D, Muthukrishnan M, Tobo BB, Rohde RL, Varvares MA, Osazuwa-Peters N. Correlates of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination initiation and completion among 18-26 year olds in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother Internet 2018;1–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29708826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson L, Rubens-Augustson T, Murphy M, Jardine C, Crowcroft N, Hui C, Wilson K. Barriers to immunization among newcomers: A systematic review. Vaccine Internet 2018;36:1055–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McComb E, Ramsden V, Olatunbosun O, Williams-Roberts H. Knowledge, Attitudes and barriers to Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake among an immigrant and refugee catch-up group in a Western Canadian Province. J Immigr Minor Heal Internet 2018; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29445898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, Welch V, Swinkels H, Rashid M, Narasiah L, Kirmayer L, Ueffing E, MacDonald N, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183:e824–925. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kowal SP, Jardine CG, Bubela TM. “If they tell me to get it, I’ll get it. If they don’t…”: immunization decision-making processes of immigrant mothers. Can J Public Health Internet 2015;106:e230–5. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=26285195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diana C, Xochitl C, Magdalena RR, V M M, Teresa A, Liliana O. Pandemics and vaccines: perceptions, reactions, and lessons learned from hard-to-reach latinos and the H1N1 campaign. J Heal Care Poor Underserved Internet 2012;23:1106–1122. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=104498935&site=ehost-live. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim K, LeClaire A-R. A systematic review of factors influencing human papillomavirus vaccination among immigrant parents in the United States. Health Care Women Int Internet 2017;1–23.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29161198 doi: 10.1080/07399332.2017.1404064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomas J. Connecting research and policy. Isuma Can J Policy Res. 2000;1:140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carnegie E, Whittaker A, Gray Brunton C, Hogg R, Kennedy C, Hilton S, Harding S, Pollock KG, Pow J. Development of a cross-cultural HPV community engagement model within Scotland. Health Educ J Internet 2017;76:398–410. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0017896916685592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atkinson KM, Westeinde J, Ducharme R, Wilson SE, Deeks SL, Crowcroft N, Hawken S, Wilson K. Can mobile technologies improve on-time vaccination? A study piloting maternal use of ImmunizeCA, a Pan-Canadian immunization app. Hum Vaccines Immunother Internet 2016;12:2654–2661. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1194146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atkinson KM, Westeinde J, Hawken S, Ducharme R, Barnhardt K, Wilson K. Using mobile technologies for immunization: predictors of uptake of a pan-Canadian immunization app (ImmunizeCA). Paediatr Child Health Internet 2015;20:351–352. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26525986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paradis M, Atkinson KM, Hui C, Ponka D, Manuel DG, Day P, Murphy MSQ, Rennicks White R, Wilson K. Immunization and technology among newcomers: A needs assessment survey for a vaccine-tracking app. Hum Vaccin Immunother Internet 2018;1–5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29482427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farias AJ, Savas LS, Fernandez ME, Coan SP, Shegog R, Healy CM, Lipizzi E, Vernon SW. Association of physicians perceived barriers with human papillomavirus vaccination initiation. Prev Med (Baltim) [Internet] 2017;105:219–225. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28834689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrer HB, Trotter C, Hickman M, Audrey S. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination of young women in high-income countries: a qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health Internet 2014;14:700 http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-14-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadaf A, Richards JL, Glanz J, Salmon DA, Omer SB. A systematic review of interventions for reducing parental vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine Internet 2013;31:4293–4304. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23859839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creswell Poth CJ. qualitative inquiry and research design (International Student Edition): choosing among five approaches. 4th Los Angeles (CA): SAGE Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Statistics Canada Immigration and ethnocultural diversity: key results from the 2016 census. Dly Internet 2017;1–8.http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025b-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dicicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. 2006. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ. 40:314–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today Internet 2004;24:105–112. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14769454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabatier PA. An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sci Internet 1988;21:129–168. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4532139. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- World Health Organization Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer [Internet]. 2018. [accessed 2018 April 10].http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer