Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the endoscopic features of lanthanum-associated duodenal lesions and the prevalence of duodenal involvement among patients with pathologically proven lanthanum deposition in the gastrointestinal tract.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 24 patients with pathologically proven lanthanum deposition in the gastrointestinal tract. Patients were subdivided into three groups: Group A, patients with pathologically-proven lanthanum deposition in the duodenum; Group B, patients without lanthanum deposition in the duodenum; and Group C, patients without a biopsy of the duodenum.

Results

A biopsy examination of the duodenum was performed in 19 patients, and lanthanum deposition was detected in 17 patients (17/19, 89.5%). In group A (n=17), whitish duodenal villi were detected in 15 patients during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (15/17, 88.2%). While the other two patients showed no whitish villi, a biopsy of the duodenal mucosa revealed lanthanum deposition. The deposition of a white substance showing a clear margin was visible within multiple villi under magnified observation in some patients of group A. Group B patients (n=2) also showed whitish villi. However, the whitish color was faint in one case and sparse in the other case.

Conclusion

Lanthanum deposits in the duodenum may resemble white villi. However, in some cases, these deposits may be unrecognizable during esophagogastroduodenoscopy due to the subtle degree of deposition. Endoscopists should biopsy the duodenum as well as the stomach, regardless of the presence or absence of white villi, for an accurate determination of lanthanum deposition in the gastrointestinal tract.

Keywords: hyperphosphatemia, lanthanum carbonate, scanning electron microscopic analysis, esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Introduction

Lanthanum carbonate is widely used to reduce phosphate levels in patients with end-stage renal disease because high levels of serum phosphate can lead to complications with calcium absorption, leading to osteoporosis and arteriosclerosis (1-4). Once lanthanum carbonate is ingested orally, it binds to phosphate in the gastrointestinal tract and reduces its absorption throughout the gastrointestinal tract (5, 6). This agent has been proven to be an effective phosphate binder for controlling hyperphosphatemia, based on the results of both short- and long-term clinical studies that have demonstrated its efficacy and an acceptable safety profile (7, 8). However, in 2015, several researchers reported lanthanum deposition in the gastrointestinal mucosa, particularly in the stomach (9-13). Lanthanum-related gastric lesions have since been described as white lesions in most previously reported cases (11, 12, 14-16).

We observed lanthanum deposition in the duodenum as white villi (17). However, the clinicopathological features of duodenal lesions associated with lanthanum deposition have not been fully revealed due to the infrequency of this entity. In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed cases with lanthanum deposition in the stomach and/or duodenum and investigated the endoscopic features of lanthanum-associated duodenal lesions and the prevalence rate of involvement among patients with pathologically proven lanthanum deposition in the gastrointestinal tract.

Materials and Methods

A database search of endoscopy examination reports of the Department of Endoscopy at Okayama University Hospital identified 24 patients with pathologically proven lanthanum deposition in the gastrointestinal tract diagnosed between January 2013 and May 2018. Therefore, these 24 patients were included in this study. Of note, a subset of the 24 patients examined herein had also been included as subjects in our previous studies (16-23).

A histologic diagnosis was performed using endoscopically biopsied specimens or endoscopically resected specimens based on the presence of fine amorphous eosinophilic material on hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissues, as described previously (16-23). We also performed scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and chemical analyses using energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDX) in all of the patients in order to confirm the presence of lanthanum (20, 21, 23). In brief, a paraffin-embedded section was deparaffinized with xylene (10 minutes twice) and subsequently washed with a serial dilution of ethanol (100% for 5 minutes, 3 times; 80% for 5 minutes; 50% for 5 minutes). The surface of the sample was coated with osmium for 10 seconds (HPC-1S-type osmium coater; Shinku Device, Ibaraki, Japan), and SEM images were obtained using an S4800 electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

According to the biopsy result for lanthanum deposition in the duodenum, patients were subdivided into three groups: Group A, patients with pathologically-proven lanthanum deposition in the duodenum; Group B, patients without lanthanum deposition in the duodenum; and Group C, patients without a biopsy of the duodenum. We retrospectively reviewed the patients' clinical records and investigated the data of each subgroup regarding the endoscopic, radiological, biological, and pathological examinations.

This retrospective study was approved by the ethics committee of Okayama University Hospital and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

The patients' characteristics are shown in Table. Among the 24 patients, a biopsy examination of the duodenum was performed in 19, and lanthanum deposition was detected in 17 (17/19, 89.5%). In our institution, lanthanum was detected in the biopsied specimens from the stomach and/or duodenum in all patients. Thus, all of the patients in group B (n=2; showed negative results for duodenal lanthanum deposition) and group C (n=5; did not undergo any biopsy of the duodenum) showed gastric lanthanum deposition. In group A (n=17), lanthanum was detected in both the stomach and duodenum in 15 patients (88.2%), while the remaining 2 showed duodenal lanthanum deposition alone. The median age of the patients was 57 years in group A (range: 31 to 76 years), 76 years in group B (range: 75 to 77 years), and 70 years in group C (range: 65 to 77 years), respectively. There was male predominance, with 14 males in group A (82.4%), 1 in group B (50.0%), and 4 in group C (80.0%).

Table.

Patients’ Characteristics.

| Total | Group A: Duodenal involvement positive |

Group B: Duodenal involvement negative |

Group C: No biopsy of the duodenum |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (N) | 24 | 17 | 2 | 5 |

| Age (median, years) | 66 | 57 | 76 | 70 |

| Sex, male | 19 (79.2%) | 14 (82.4%) | 1 (50.0%) | 4 (80.0%) |

| Involved sites | ||||

| Stomach | 22 (91.7%) | 15 (88.2%) | 2 (100%) | 5 (100%) |

| Duodenum | 17 (70.1%) | 17 (100%) | 0 | NA |

| Positive GI symptoms during EGD | 8 (33.3%) | 6 (35.3%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| White villi observed during EGD | 18 (75.0%) | 15 (88.2%) | 2 (100%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Period of consuming lanthanum carbonate (median, months) | 56 | 56 | NA* | 81 |

GI: gastrointestinal, EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy, NA: not available

*The duration of consumption of lanthanum carbonate was two months in one patient, whereas information regarding the administration period was not available for the other patient.

The median period of consumption of lanthanum carbonate was 56 months in group A and 81 months in group C. One patient in group B had been consuming lanthanum carbonate for two months, and detailed information regarding the administration period was not available for the other patient. One patient in group A had stopped consuming lanthanum carbonate three months before the diagnosis of lanthanum deposition in the stomach and duodenum. The other 23 patients had been consuming lanthanum carbonate when they were diagnosed with lanthanum deposition.

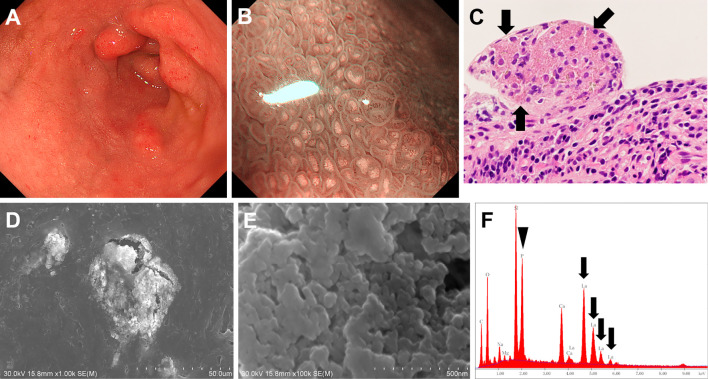

Figs. 1-3 show representative endoscopic images of lanthanum deposition in the duodenum. In Case 1 (73-year-old man), although whitish villi were partly observed during esophagogastroduodenoscopy, they were faint and not readily recognizable under white-light imaging (Fig. 1A). Magnifying observation with narrow-band imaging revealed the presence of a white substance within each villus (Fig. 1B). A biopsy of the villi showed fine amorphous eosinophilic material on hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissues, which is a typical feature of lanthanum deposition (Fig. 1C). Lanthanum deposits appeared as bright aggregates of particles under SEM (Fig. 1D and E). The EDX analysis revealed the presence of lanthanum (Fig. 1F, arrows) and phosphate (Fig. 1F, arrowhead) in the area of deposition.

Figure 1.

Duodenal lesions observed in Case 1 (73-year-old man). Whitish villi were partly observed during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (A). Magnifying observation with narrow-band imaging clearly demonstrated the presence of a white substance (B). Fine amorphous eosinophilic material was observed in Hematoxylin and Eosin staining tissues (C). Lanthanum deposits appeared as bright aggregates of particles under scanning electron microscopy (D, E). Lanthanum (F, arrows) and phosphate (F, arrowhead) elements were confirmed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry.

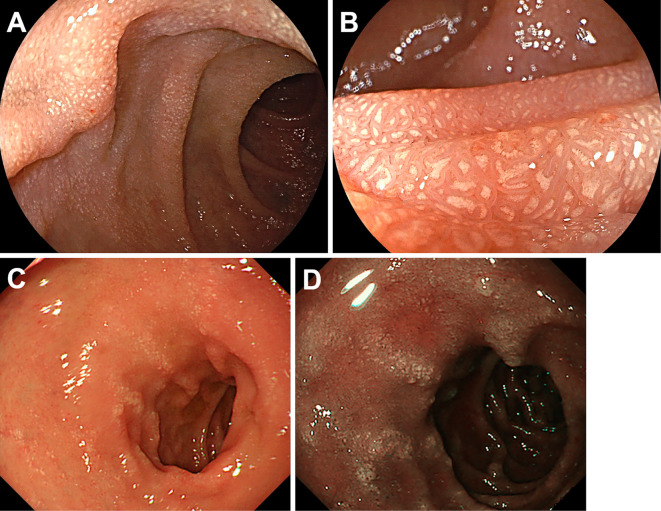

Figure 2.

Endoscopy images of duodenal lanthanum deposition. Case 2 (60-year-old woman) manifested diffuse whitish mucosa (A, B). In Case 3 (67-year-old man), whitish mucosa was partly seen as longitudinal whitish lines under white-light (C) and narrow-band imaging (D). Biopsy specimens taken from the whitish lesions contained lanthanum.

Figure 3.

Endoscopy images of Case 4 (66-year-old man). Although whitish villi were absent (A: White-light imaging, B: Narrow-band imaging), a biopsy from the duodenal mucosa revealed lanthanum deposition (C, arrow).

Fig. 2A and 2B. show another case (Case 2, 60-year-old woman) with prominent lanthanum deposition in the duodenum. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed diffuse whitish mucosa throughout the duodenal bulb (Fig. 2A). Magnifying observation with white-light imaging showed deposition within the villi, which was similar to the magnified endoscopic image of Case 1. In Case 3 (67-year-old man), whitish mucosa was partly seen as longitudinal whitish lines under white-light (Fig. 2C) and narrow-band imaging (Fig. 2D). Biopsy specimens taken from the whitish lesions contained lanthanum.

In group A, whitish duodenal villi were detected in 15 cases during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (15/17, 88.2%). Among the 15 patients, 7 showed involvement of both the duodenal bulb and the second portion, 6 showed involvement of the duodenal bulb alone, and the other 2 showed involvement of the second portion of the duodenum alone. Whitish duodenal villi were observed as longitudinal whitish lines in only 1 patient (Fig. 2C and D), whereas whitish villi were diffusely observed in the remaining 14 patients. In 2 patients, although whitish villi were not observed during esophagogastroduodenoscopy, a biopsy of the duodenal mucosa revealed lanthanum deposition (Fig. 3, Case 4, 66-year-old man).

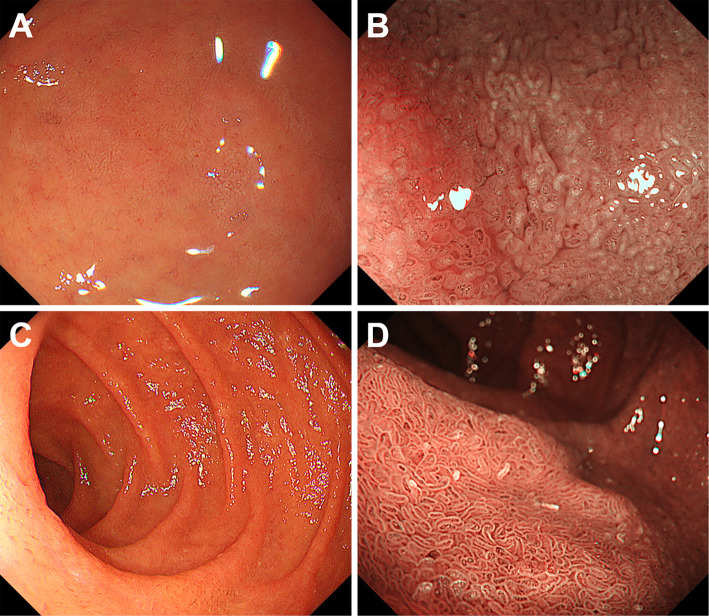

Endoscopy images of group B patients are shown in Fig. 4. In these patients, whitish villi were observed during esophagogastroduodenoscopy, although the whitish color was faint in Case 5 (Fig. 4B, 75-year-old woman) and sparse in Case 6 (Fig. 4D, 77-year-old man) under magnifying observation with narrow-band imaging compared to the endoscopic images shown in Figs. 1B and 2B. There was no lanthanum deposition in the biopsy specimens taken from the duodenal mucosa of these two patients.

Figure 4.

Endoscopy images of group B patients. Whitish color was faint in Case 4 (A, B, 75-year-old woman) and sparse in Case 5 (C, D, 77-year-old man). No lanthanum deposition was detected in the duodenum of these two patients.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the endoscopic features and characteristics of patients with duodenal lanthanum deposition. As described above, lanthanum deposition in the stomach has most frequently been reported to occur as white lesions. In our previous studies, we classified the endoscopic features of the lanthanum-associated gastric lesions as white spots, annular whitish mucosa, and diffuse whitish mucosa (21). We also revealed that, using an EDX analysis, pathological lanthanum deposition corresponds to white lesions in the gastric mucosa, which can be observed endoscopically (23). However, the endoscopic features of lanthanum-associated duodenal lesions have rarely been reported. Several authors described the detection of lanthanum deposition in biopsy specimens taken from duodenal ulcers (11), granular and micronodular mucosa (24), granular mucosa (25), and duodenitis (26). Shitomi et al. reported bright white spots as duodenal lanthanum-associated lesions (27). Although, several researchers have reported pathological lanthanum deposition in the duodenum, the endoscopic images or features of the duodenal lesions were not described in their reports (10, 28, 29). The present study revealed that 15/17 patients (88.2%) with duodenal lanthanum deposition presented with white villi. Therefore, we consider white lesions to be the essential macroscopic feature of lanthanum deposition in the duodenum, as seen in the stomach.

During esophagogastroduodenoscopy, the deposition of white substance showing clear margin was visible within multiple villi under magnifying observation, as shown in Case 1 (Fig. 1) and Case 2 (Fig. 2A and B). Conversely, although white villi were observed in patients without lanthanum deposition as well, the margin of the white lesion was faint (Fig. 4B) and the white villi were sparse (Fig. 4D). Consequently, we speculated that the deposition of a white substance showing a clear margin within multiple villi was a distinctive feature of duodenal lanthanum deposition. Of note, various etiologies can present with white lesions in the duodenum, including follicular lymphoma, lymphangiectasia, lymphangioma, adenoma, hyperplastic polyp, duodenitis, and erosion (30). Magnified endoscopic features, in combination with macroscopic features, may therefore be useful for differentiating lanthanum deposition from other duodenal diseases presenting with whitish lesions. However, further investigations will be required in order to elucidate the endoscopic features that are specific to this disease entity, as magnifying observation was performed in only a limited number of patients in the present study.

Ban et al. reviewed 10 biopsy specimens taken from the duodenal mucosa of patients who had been diagnosed with gastroduodenal lanthanum deposition and reported that lanthanum deposition was observed in 3 samples (30%) (31). In the present study, more frequent involvement was observed; 17/19 patients (89.5%) who underwent a duodenal biopsy showed lanthanum deposition. However, the subjects in the study by Ban et al. and our own were patients who had manifested lanthanum deposition in the stomach and/or duodenum. Therefore, the true prevalence rate of duodenal lanthanum deposition in the consumers of lanthanum carbonate has yet to be determined, and further investigations are warranted to determine this prevalence.

Of note, in group A, lanthanum deposition was detected in the biopsy specimens taken from the duodenal villi even when whitish lesions were absent (Fig. 3). Therefore, a subtle degree of lanthanum deposition may be unrecognizable under endoscopic observation; however, it can be detected by optical microscopy or electron microscopy. Consequently, endoscopists should obtain biopsy specimens from the duodenal mucosa of patients who are consuming lanthanum carbonate or have a history of consuming such agents, regardless of whether or not white villi are present.

In group B, although information regarding the administration period was not available in one patient, the duration of consumption of lanthanum carbonate was two months in the other patient, which was the shortest among the enrolled patients. Therefore, it is likely that a shorter administration period tends to yield negative biopsy results for duodenal involvement of lanthanum deposition. Another possibility is that sampling error occurred during the endoscopic biopsy procedure, leading to false-negative pathology results. Since group B consisted of only two patients, further investigations will be required to reveal the factors associated with negative results of a duodenal biopsy.

At present, the pathogenicity of lanthanum deposition in the gastrointestinal tract has not been elucidated in actual clinical settings. However, in the latest report by Yabuki et al., the authors administered lanthanum carbonate to rats and observed glandular atrophy, stromal fibrosis, proliferation of mucous neck cells, intestinal metaplasia, squamous cell papilloma, erosion, and stomach ulcer (32). They speculated that such various histologic alterations were probably caused by lanthanum deposition in the gastric mucosa, meaning that lanthanum deposition can lead to abnormal cell proliferation or neoplastic lesions. Another possible concern is the potential damage to patients' health due to the deposition of inorganic substances from a long-term perspective. For example, aluminum encephalopathy syndrome manifested as progressive encephalopathy in infants and children with chronic renal insufficiency who had been consuming aluminum-containing products, such as phosphate binders, for several years (33). While serious organ injury due to lanthanum phosphate intake has not yet been reported, we believe that the accurate diagnosis of gastroduodenal lanthanum deposition and a follow-up survey of such patients will prove important for promptly diagnosing lanthanum-related health problems that might occur in the future.

Conclusion

We observed the involvement of the duodenal mucosa in 89.5% of patients with gastroduodenal lanthanum deposition in the present study. Furthermore, lanthanum deposits in the duodenum tended to appear as white villi. However, a subtle degree of lanthanum deposition may be unrecognizable during esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Therefore, in order to precisely diagnose lanthanum deposition in the gastrointestinal tract, endoscopists should take biopsy samples from the duodenum as well as from the stomach, regardless of the presence or absence of white villi.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Patel L, Bernard LM, Elder GJ. Sevelamer versus calcium-based binders for treatment of hyperphosphatemia in CKD: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 232-244, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langote A, Ahearn M, Zimmerman D. Dialysate calcium concentration, mineral metabolism disorders, and cardiovascular disease: deciding the hemodialysis bath. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 348-358, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byon CH, Chen Y. Molecular mechanisms of vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease: the link between bone and the vasculature. Curr Osteoporos Rep 13: 206-215, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang C, Wen J, Li Z, Fan J. Efficacy and safety of lanthanum carbonate on chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder in dialysis patients: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol 14: 226, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.St. Peter WL, Wazny LD, Weinhandl E, Cardone KE, Hudson JQ. A review of phosphate binders in chronic kidney disease: incremental progress or just higher costs? Drugs 77: 1155-1186, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutchison AJ, Wilson RJ, Garafola S, Copley JB. Lanthanum carbonate: safety data after 10 years. Nephrology (Carlton) 21: 987-994, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Zhang YX, Yu XQ, et al. Lanthanum carbonate for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in CKD 5D: multicenter, double blind, randomized, controlled trial in mainland China. BMC Nephrol 14: 29, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sprague SM, Abboud H, Qiu P, Dauphin M, Zhang P, Finn W. Lanthanum carbonate reduces phosphorus burden in patients with CKD stages 3 and 4: a randomized trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 178-185, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makino M, Kawaguchi K, Shimojo H, Nakamura H, Nagasawa M, Kodama R. Extensive lanthanum deposition in the gastric mucosa: the first histopathological report. Pathol Int 65: 33-37, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothenberg ME, Araya H, Longacre TA, Pasricha PJ. Lanthanum-induced gastrointestinal histiocytosis. ACG Case Rep J 2: 187-189, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haratake J, Yasunaga C, Ootani A, Shimajiri S, Matsuyama A, Hisaoka M. Peculiar histiocytic lesions with massive lanthanum deposition in dialysis patients treated with lanthanum carbonate. Am J Surg Pathol 39: 767-771, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasunaga C, Haratake J, Ohtani A. Specific accumulation of lanthanum carbonate in the gastric mucosal histiocytes in a dialysis patient. Ther Apher Dial 19: 622-624, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tonooka A, Uda S, Tanaka H, Yao A, Uekusa T. Possibility of lanthanum absorption in the stomach. Clin Kidney J 8: 572-575, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishikawa Y, Yokoi H, Sakurai T, Horimatsu T, Miyamoto S. Lanthanum deposition in the gastric mucosa in a patient undergoing hemodialysis. QJM 111: 347-348, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami N, Yoshioka M, Iwamuro M, et al. Clinical characteristics of seven patients with lanthanum phosphate deposition in the stomach. Intern Med 56: 2089-2095, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwamuro M, Kanzaki H, Kawano S, Kawahara Y, Tanaka T, Okada H. Endoscopic features of lanthanum deposition in the gastroduodenal mucosa. Gastroenterol Endosc 59: 1428-1434, 2017(in Japanese, Abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwamuro M, Tanaka T, Urata H, Kimoto K, Okada H. Lanthanum phosphate deposition in the duodenum. Gastrointest Endosc 85: 1103-1104, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwamuro M, Sakae H, Okada H. White gastric mucosa in a dialysis patient. Gastroenterology 150: 322-323, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwamuro M, Kanzaki H, Tanaka T, Kawano S, Kawahara Y, Okada H. Lanthanum phosphate deposition in the gastric mucosa of patients with chronic renal failure. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 113: 1216-1222, 2016(in Japanese, Abstract in English). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwamuro M, Urata H, Tanaka T, et al. Lanthanum deposition in the stomach: usefulness of scanning electron microscopy for its detection. Acta Med Okayama 71: 73-78, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murakami N, Yoshioka M, Iwamuro M, et al. Clinical characteristics of seven patients with lanthanum phosphate deposition in the stomach. Intern Med 56: 2089-2095, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwamuro M, Urata H, Tanaka T, et al. Lanthanum deposition in the stomach in the absence of helicobacter pylori infection. Intern Med 57: 801-806, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwamuro M, Urata H, Tanaka T, et al. Lanthanum deposition corresponds to white lesions in the stomach. Pathol Res Pract 214: 934-939, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoda RS, Sanyal S, Abraham JL, et al. Lanthanum deposition from oral lanthanum carbonate in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Histopathology 70: 1072-1078, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komatsu-Fujii T, Onuma H, Miyaoka Y, et al. A Combined deposition of lanthanum and β2-microglobulin-related amyloid in the gastroduodenal mucosa of hemodialysis-dependent patients: an immunohistochemical, electron microscopic, and energy dispersive X-ray spectrometric analysis. Int J Surg Pathol 25: 674-683, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hattori K, Maeda T, Nishida S, et al. Correlation of lanthanum dosage with lanthanum deposition in the gastroduodenal mucosa of dialysis patients. Pathol Int 67: 447-452, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shitomi Y, Nishida H, Kusaba T, et al. Gastric lanthanosis (lanthanum deposition) in dialysis patients treated with lanthanum carbonate. Pathol Int 67: 389-397, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goto K, Ogawa K. Patients with lanthanum carbonate therapy: a clinicopathologic study of 13 cases, including 1 case of lanthanum granuloma in the colon and 2 nongranulomatous gastric cases. Lanthanum deposition is frequently observed in the gastric mucosa of dialysis. Int J Surg Pathol 24: 89-92, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yabuki K, Shiba E, Harada H, et al. Lanthanum deposition in the gastrointestinal mucosa and regional lymph nodes in dialysis patients: analysis of surgically excised specimens and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract 212: 919-926, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwamuro M, Okada H, Takata K, et al. Magnified endoscopic features of duodenal follicular lymphoma and other whitish lesions. Acta Med Okayama 69: 37-44, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ban S, Suzuki S, Kubota K, et al. Gastric mucosal status susceptible to lanthanum deposition in patients treated with dialysis and lanthanum carbonate. Ann Diagn Pathol 26: 6-9, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yabuki K, Haratake J, Tsuda Y, et al. Lanthanum-induced mucosal alterations in the stomach (lanthanum gastropathy): a comparative study using an animal model. Biol Trace Elem Res 185: 36-47, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrade LG, Garcia FD, Silva VS, et al. Dialysis encephalopathy secondary to aluminum toxicity, diagnosed by bone biopsy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 2581-2582, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]